1. Introduction

The rise of the sharing economy has transformed traditional consumption and production models, creating both opportunities and tensions for manufacturers. Consumers increasingly value access over ownership, fostering the growth of product-sharing platforms that support flexible, and affordable consumption experiences. According to industry estimates, sharing-based models have eroded 10–30% of revenues in many traditional sectors over the past decade (Schroder [

1]), forcing manufacturers to adapt.

In response, many manufacturers have entered the sharing economy by offering product-leasing services through business-to-customer (B2C) platforms or enabling consumer-to-consumer rentals via peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms. This dual-channel presence can improve product utilization and extend product lifecycles. However, it also introduces challenges such as market cannibalization, price competition, and channel conflicts. To mitigate these issues, manufacturers increasingly adopt vertical product differentiation—offering different quality levels across different channels.

For example, in the mobility sector, BMW’s DriveNow platform rents out lower-end models like the MINI Cooper, while Tesla has announced plans to lease premium autonomous vehicles such as the Model X. Similar patterns emerge in other industries: Shenyang Machine Tool Group leases high-end CNC equipment via iSESOL in China, and Apple has experimented with rental-based access models for its devices through the iPhone Upgrade Program. In the healthcare industry, a clear quality-based segmentation is also evident: leading manufacturers such as GE Healthcare, Philips, and Siemens Healthineers lease advanced MRI and CT scanners to large hospitals, whereas smaller domestic firms such as Mindray and SonoScape provide rentals of basic devices like ultrasound and patient monitors to community clinics. These cases highlight a common trend—manufacturers strategically differentiate rental offerings by product quality to segment markets and alleviate competitive frictions in shared markets.

A growing body of research has explored product sharing from various angles, including platform pricing (Cachon et al. [

2]), consumer heterogeneity (Abhishek et al. [

3]), and manufacturer-platform partnerships (Li et al. [

4]). Yet most studies focus on monopolistic contexts or single-product settings. Less attention has been paid to how competing manufacturers strategically design product lines when facing quality-based competition in sharing markets. Moreover, the intersection of product differentiation and channel structure remains underexplored (Bellos et al. [

5]). We hope to fill these gaps by answering the following research questions: (1) How does competition affect a manufacturer’s product line strategy for product sharing? (2) How does the product line strategy affect the price, demand, and market size?

We develop a game-theoretic model of a vertically differentiated duopoly, where each manufacturer can offer different quality products for rental on its B2C platform, in addition to direct sales and P2P options. Consumers decide whether to rent or buy based on their usage value. We characterize three product line strategies: no-product line (i.e., the manufacturer does not rent products on the B2C sharing platform), high-end product line (i.e., the manufacturer rents high-end products on the B2C sharing platform), and low-end product line (i.e., the manufacturer rents low-end products on the B2C sharing platform). Through subgame perfect Nash equilibrium analysis, we identify the manufacturers’ equilibrium choices and assess the impact on market outcomes.

Our results show that the high-quality manufacturer prefers offering high-end products for rental, while the low-quality manufacturer opts for low-end rentals—forming a unique equilibrium that leads to a Pareto improvement. This equilibrium expands quality differentiation, mitigates cannibalization, and enables effective price discrimination without altering retail prices or market size. In contrast, strategies that fail to widen quality gaps intensify price competition and reduce retail demand. Managerially, aligning rental offerings with product positioning helps manufacturers coordinate channels, segment markets more effectively, and enhance overall performance in competitive sharing environments.

The rest of our paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 summarizes the relevant literature. The main model is introduced in

Section 3.

Section 4 studies competing manufacturers’ product line strategies. In

Section 5, we discuss the impact of product line strategies on manufacturers’ equilibrium prices and market sizes.

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Literature

In this section, we review the related literature on product sharing, product lines, and multi-product competition to place our analysis in context.

2.1. Product Sharing

A stream of research has focused on operational aspects of sharing platforms, including vehicle routing (He et al. [

6]; Kabra et al. [

7]), staffing (Gurvich et al. [

8]), pricing (Bai et al. [

9]; Chen & Hu [

10]; Hu & Zhou [

11]; Kamble [

12]; Taylor [

13]), and risk management (Hong et al. [

14]; Weber [

15]; Liu et al. [

16]). For instance, Mao et al. [

17] further highlight the impact of operational performance on platform revenue.

Another stream of literature has investigated strategic partnerships between manufacturers and sharing platforms. On the supply side, Yu et al. [

18] and Tian et al. [

19] demonstrate that manufacturers might shift from traditional selling to leasing when per-use profit or marginal cost justifies the transition. Bellos et al. [

5] emphasize how low-end, fuel-efficient car-sharing options can improve sustainability outcomes while maximizing returns. From the demand perspective, Abhishek et al. [

3] and Li et al. [

4] examine how usage heterogeneity and perceived value influence a manufacturer’s decision to collaborate with P2P or B2C platforms. These studies complement earlier work on pricing effects and channel coordination challenges (Jiang & Tian [

20]; Tian & Jiang [

21]). Zhang et al. [

22] further explore the optimal sharing model for a monopolist manufacturer, establishing an important benchmark for single-firm decisions.

Recent studies directly informing our work on quality differentiation and platform competition include Zhang et al. [

23], who examine the impact of quality differentiation on a sharing manufacturer’s product line strategy in a monopoly setting. Guan et al. [

24] find that in a vertically differentiated duopoly, a manufacturer that establishes its own platform always benefits, while its rival may benefit only if quality differentiation is sufficient and production costs are not insignificant. Similarly, Zhang et al. [

25] show that duopoly outcomes depend on the quality gap, with P2P generating scale effects and B2C enabling price discrimination.

However, these studies typically consider either monopoly/competition settings or quality differentiation/product lines in isolation, without addressing differentiated product lines in a competitive environment. Moreover, our work considers manufacturers’ strategies of concurrently selling and adjusting product lines across multiple sharing channels (B2C and P2P). Our research addresses this gap by examining this complex interaction in a duopoly setting, demonstrating product line strategies for sharing manufacturers that incorporate rental channels within a competitive context.

2.2. Product Lines

Our work is also related to the literature on product line design, especially under quality differentiation (e.g., Mendelson and Parlaktürk [

26]); Shugan et al. [

27]). Foundational works by Mussa and Rosen [

28] and Moorthy [

29] analyze vertical differentiation and intra-line cannibalization in monopolistic settings. Desai et al. [

30] and Heese and Swaminathan [

31] point out that the lower the quality differentiation within the product line, the more intense the cannibalism. Desai [

32] considers two dimensions of quality differentiation and level difference (i.e., taste preference), and studies how and when cannibalism affects product line design.

Recent research explores how product line strategy responds to demand uncertainty (Xu and Dukes [

33]), communication and search costs (Villas-Boas [

34]; Kuksov and Villas-Boas [

35]), or endogenous quality choices (Joshi et al. [

36]). Notably, Ha et al. [

37] suggest that firms may prefer to allocate high-end products to direct sales channels while reserving low-end versions for secondary or less controlled channels—paralleling what we observe in B2C rental practices.

However, this body of work largely overlooks sharing platforms. The most relevant study is Zhang et al. [

23], who explored the impact of quality differentiation on a monopolist’s product line design. We extend this inquiry to a competitive environment. Our contribution lies in integrating product line strategy, dual-channel sharing, and competition, illustrating how competitive factors influence firms’ product line strategies for leasing channels.

2.3. Multi-Product Competition

There is also a rich literature on competition among multi-product firms, primarily in pricing (Federgruen and Hu [

38]; Soon et al. [

39]) and quantity decisions (Kluberg and Perakis [

40]). Farahat and Perakis [

41] establish equilibrium conditions in Bertrand competition, while Doraszelski and Draganska [

42] and Chakraborty et al. [

43] explore how firms adjust product portfolios in response to seasonal, financial, or cost-related factors.

Our research complements this stream by explicitly integrating sharing platforms into the multi-product competition framework. Unlike prior studies, we model access-based consumption, dual-channel strategies, and quality-differentiated product lines, demonstrating the optimal product line strategy for multi-product competition that considers rental platforms.

2.4. Contribution of Our Work

Our study provides a unified framework for analyzing quality-based competition in sharing markets, thereby contributing to three streams: product sharing, product line strategy, and multi-product competition. Unlike previous research focused on monopoly or single-product contexts—and even compared to recent studies exploring P2P/B2C mechanisms—we explicitly consider duopolistic competition where manufacturers design product lines spanning direct sales, B2C rental, and P2P sharing channels.

Crucially, we emphasize the strategic role of vertical differentiation in reducing cannibalization, maintaining pricing power, and enhancing market segmentation. This enables manufacturers to manage cross-channel self-competition and optimize profitability. Furthermore, our model integrates platform-mediated access into multi-product competition, offering a comprehensive perspective on how sharing platforms reshape product line strategies. By linking quality-differentiated product lines with dual-channel sharing considerations, our study addresses a gap in the recent literature and provides actionable insights for firms navigating contemporary sharing markets.

3. Model

There are two competing manufacturers in the market, which sell the retail product to consumers directly and provide the product sharing service to consumers through their own P2P sharing platforms (e.g., Daimler, the parent company of Mercedes-Benz, operates car-sharing services through its P2P platform Croove). The two manufacturers are vertical differences in the quality of retail products, where . The quality differentiation between retail products is defined as . Manufacturer may expand its product line by building the B2C sharing platform to provide the rental product () (the B2C sharing platform enables rental-based consumption and can help improve product utilization).

Consumers decide whether to buy products, rent products from P2P platforms, or rent products from B2C platforms based on their utility. Without loss of generality, we assume that the market size is 1 and each consumer use at most one unit of the product. On the one hand, Consumers’ usage valuation of quality is heterogeneous, captured by

, which is the willingness to pay for quality and independent and distributed uniformly within

. A consumer of type

obtains usage value

(or

) when using a product of quality

(or

), where

is the constant (

) and represents the basic utility brought by the product. We assume that

is large enough, which means that all consumers will use the product. On the other hand, consumers will not use the product during the entire use time. Referring to Benjaafar et al. [

44], we assume that consumer’s usage level is

, which indicates the proportion of time they plan to use the product,

. This means that consumers who have purchased the product (called the owner) have

percentage of the time to rent it out through the P2P platform. The renter rents the owner’s product from the P2P platform of manufacturer

at the market-clearing price

per usage level (Jiang and Tian [

18]), and uses it with

percentage of the time. Manufacturer

will charge a commission fee

per usage level, where the exogenous

is called the commission rate (Abhishek et al. [

3]). The marginal cost of manufacturer

’s retail product and rental product (on the B2C platform) are

and

. We let

and

denote the quality differentiation and cost difference between retail and rental products, respectively (We consider the quality differentiation of heterogeneity (i.e., the quality differentiation of high-end product lines is q_s1, and that of low-end product lines is q_s2), and show that the equilibrium is consistent with the conclusion of the main model).

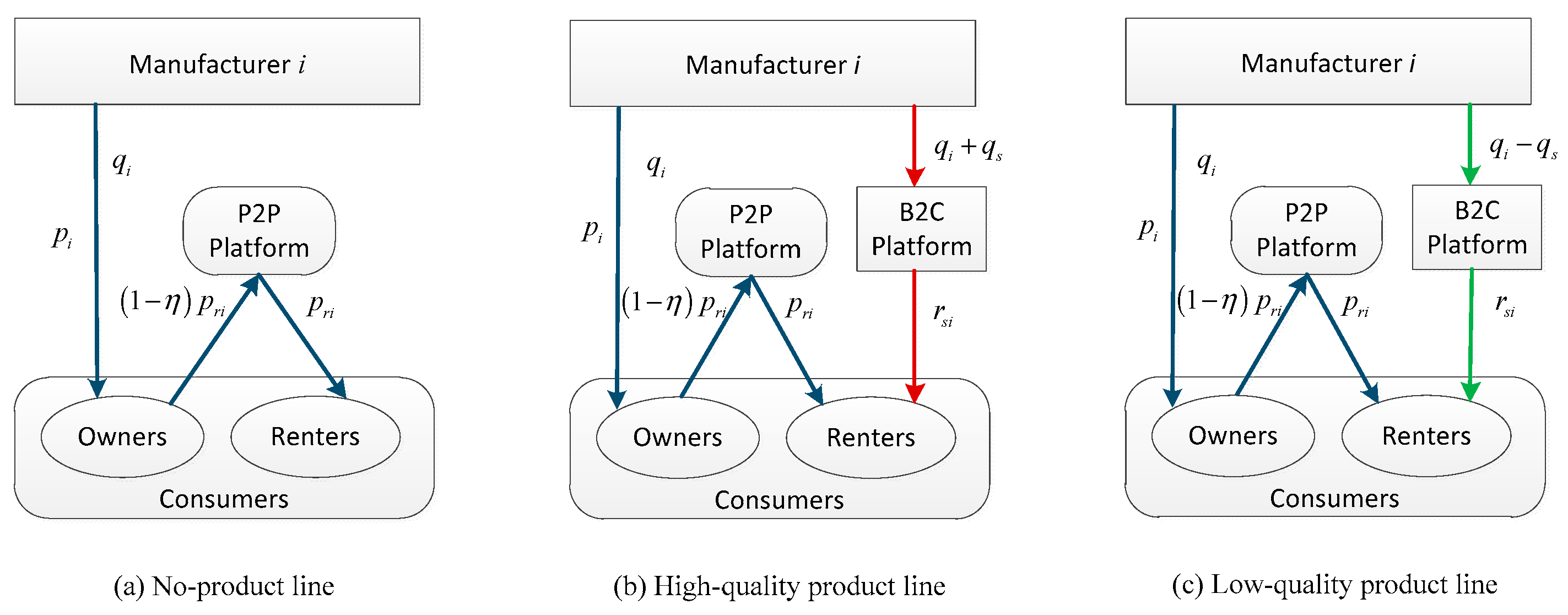

Manufacturer

has three product line strategies, and the model structure is presented in

Figure 1. If manufacturer

adopts the no-product line strategy, he will produce retail product

at retail price

(

Figure 1a). If manufacturer

adopts the high-end product line strategy, he will produce rental products of quality

at the marginal cost

by B2C platform (

Figure 1b). If manufacturer

adopts the low-end product line strategy, he will produce rental products of quality

at marginal cost

by B2C platform (

Figure 1c). The renter rents the rental product on the B2C platform of manufacturer

at rental price

per usage level, which is decided by manufacturer. Assuming

and

, then even if manufacturer

L introduces high-quality products to the rental channel, it is still not dominant. For the convenience of analysis, we assume that the construction cost of the B2C platform is zero.

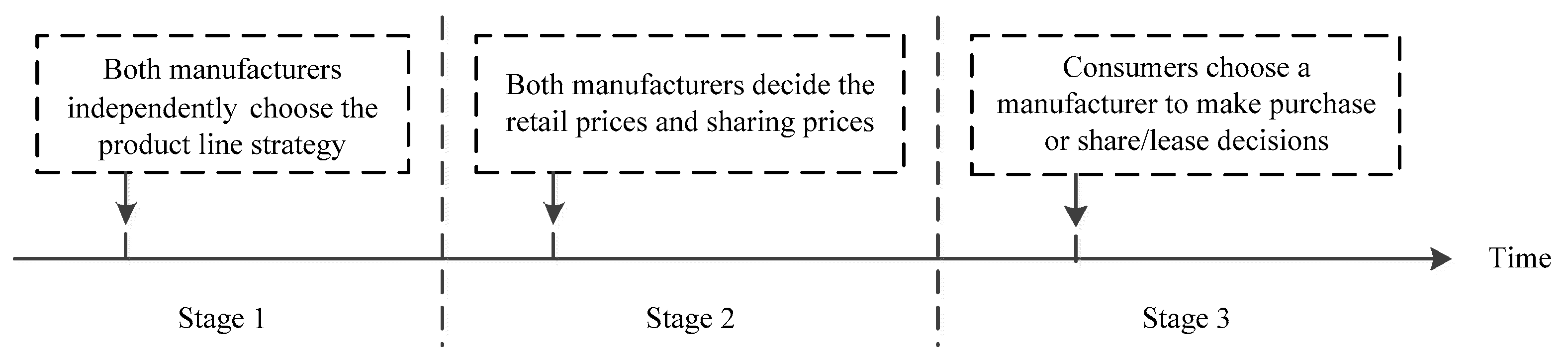

The sequence of the game is as follows. In stage 1, both manufacturers simultaneously decide their product line strategies (i.e., no-product line strategy (

N), high-end product line strategy (

)), or low-end product line strategy (

). In Stage 2, the manufacturers determine their retail price

. If manufacturer

chooses a high-end product line strategy or a low-end product line strategy, he also determines the rental price

of rental products. In Stage 3, consumers choose a manufacturer and make purchase and/or share/lease decisions. We use

to represent the product line strategy combination of competing manufacturers when the low-quality manufacturer (

L) adopts strategy

and the high-quality manufacturer (

H) adopts strategy

, where

. It follows that there are 9 possible strategy subgames,

.

Table 1 details the notation and

Figure 2 depicts the timing of events.

4. Analysis

In this section, we first analyze consumers’ purchase or share/lease decisions. Then, we present the subgame Nash equilibrium analysis. To ensure the existence of the equilibrium outcomes, and is required.

4.1. Consumer Decisions

When manufacturer

adopts the no-product line strategy (

), he will produce retail products with quality

at marginal cost

and sell them to consumers at the retail price

. The consumer either buys the retail product or rents the owner’s rental product on the P2P platform at the sharing price

per usage level, because the owner will rent it out with a probability of

. For the consumer, the utility as an owner and the utility as a renter are as follows: The utility of a consumer buying (being an owner) or renting (being a renter) the product of manufacturer

is as follows:

When manufacturer

adopts a high-end product line strategy (

), he will produce rental products with quality

at marginal cost

and rent them to consumers at the rental price

per usage level. Consumers either buy retail products or rent products on P2P platforms or rent high-quality products from manufacturers on B2C platforms. For consumers, the utility of the owner and the P2P platform’s renter is shown in Equations (1) and (2), while the utility of the renter renting the products on the B2C platform of manufacturer

is as follows:

When manufacturer

adopts a low-end product line strategy (

), he will produce rental products with quality

at marginal cost

and rent them to consumers at the rental price

per usage level. Consumers either buy retail products or rent products on P2P platforms or rent low-quality products from manufacturers on B2C platforms. For consumers, the utility of the owner and the P2P platform’s renter is shown in Equations (1) and (2), while the utility of the renter renting the products on the B2C platform of manufacturer

is as follows:

4.2. Subgame Equilibrium Analysis

In this section, the above nine subgames are divided into four cases: (1) benchmark—both manufacturers adopt the no-product line strategy; (2) at least one manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy; (3) at least one manufacturer adopts the low-end product line strategy; (4) one manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy and the other adopts the low-end product line strategy. We consider these cases sequentially.

4.2.1. Benchmark—Both Manufacturers Adopt the No-Product Line Strategy

We first consider the case where the manufacturers all adopt the no-product line strategy, i.e., the

NN subgame. Under the

N strategy, the manufacturer makes a profit by selling products and collecting the commission fee from his P2P platform. Each manufacturer’s profit includes retail profit and rental profit on the P2P platform, and the profit function is:

where

represents the retail demand of manufacturer

and

represents the size of renters from the P2P platform of manufacturer

.

Referring to Xue et al., the market-clearing price

of the P2P platform is the sharing price in the equilibrium state of supply and demand, then we obtain the equation

. And referring to Jiang and Tian [

18], P2P sharing will exist when the owner’s utility is equal to the renter’s utility, then equation

will hold, where

. These two equations guarantee the existence of P2P sharing and the balance between supply and demand. The following lemma describes the equilibrium outcomes.

Lemma 1. When both manufacturers adopt the no-product line strategy, the equilibrium prices in the

subgame are and , and the equilibrium demands in the subgame are and .

After simplifying the profit function (5), the manufacturer’s profit function can be expressed as . To ensure the uniqueness of the equilibrium price, is required, i.e., . The equilibrium profits of the two manufacturers are and , respectively.

Note that manufacturer and manufacturer have nine product line strategy combinations, and the set of product line strategy combinations is represented by . We analyze the consumer’s decision and the manufacturer’s pricing decision in each subgame. For each subgame, we start from analyzing the consumer’s decision, derive the demand for each manufacturer, and then substitute the demand into the profit function of the two manufacturers to obtain the optimal prices.

Proof of Lemma 1. NN subgame: In this subgame, both manufacturers offer the no-product line strategy, the manufacturer ’s profit is given by . The utility of the owner is . If , or the equivalent, if , consumers will buy manufacturer ’s retail products, otherwise they will buy manufacturer ’s retail products. The retail demand of the two manufacturers is and , and the profit is and . From the first order conditions (FOC), by solving , we obtain the equilibrium prices and , where . The manufacturers’ equilibrium profits are and , and in order to guarantee , need to be satisfied, which guarantees the uniqueness of the equilibrium price. □

4.2.2. At Least One Manufacturer Adopts the Strategy

We now analyze the case where at least one manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy, which results in three combinations of strategies, i.e.,

,

and

subgames. If the manufacturer adopts the

strategy, he will maximize profits by setting the retail price for the retail product, taking the commission fee from his P2P platform and setting the rental price for the rental product of the B2C platform. The profit function is as follows:

where

is the size of renters on manufacturer

’s B2C platform. The equilibrium price and demand for

,

and

subgames are presented in the following lemma.

Lemma 2. When at least one manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy, Table 2 presents the equilibrium prices and demands in the , and subgames. As shown in

Table 2, assuming that the low-quality manufacturer adopts the

N or

strategy and remains unchanged, it will only affect the high-quality manufacturer but not the competitor if the high-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy (i.e., a high-end product line strategy). Specifically, the high-quality manufacturer’s retail price remains unchanged and retail demand decreases, but the low-quality manufacturer’s retail price and retail demand remain unchanged. This shows that when the high-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy, some of its consumers will switch from its retail channel to its rental channel. Assuming that the high-quality manufacturer adopts the

N or

strategy and remains unchanged, it will affect both manufacturers if the low-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy. Specifically, both manufacturer’s retail prices decreases, and the low-quality manufacturer’s retail demand decreases and the high-quality manufacturer’s retail demand increases. This shows that when the low-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy, some of its consumers will switch from its retail channel to its competitor’s retail channel.

Proof of Lemma 2. , and subgames: In subgame, manufacturer L offers the no-product line strategy and manufacturer H offers the strategy. We have , , , , and . If , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer H, otherwise, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer L. The retail demand and the size of renters on the B2C and P2P platform of manufacturer H are , and , and the retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P platform of the manufacturer L is and . Then The equilibrium profits of competing manufacturers are and . From the first order conditions (FOC), by solving and , we obtain the manufacturers’ equilibrium prices are , , and . Then, the equilibrium profits of manufacturers are and .

In subgame, manufacturer H offers the no-product line strategy and manufacturer L offers the strategy. We have , and ,., . If , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer L, otherwise, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer L. The retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P platform of manufacturer H are and , and the retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P and B2C platform of the manufacturer L are , and . Then the profits are and . From the first order conditions (FOC), by solving and , we obtain the equilibrium prices are , , and . Then, the equilibrium profits of competing manufacturers are and .

In subgame, both manufacturers offer the strategy. We have , , , , and . If , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer L, otherwise, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer L. The retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P and B2C platform of the manufacturer are , , and . The retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P and B2C platform of the manufacturer are , , and . Then the competing manufacturers’ profits are and . From the first order conditions (FOC), by solving and , we obtain equilibrium prices are , , and . The profits are and . □

4.2.3. At Least One Manufacturer Adopts the Strategy

We now analyze the case where at least one manufacturer adopts the low-end product line strategy, which results in three combinations of strategies, i.e.,

,

and

subgames. If the manufacturer adopts the

strategy, the profit function is as follows:

The following lemma discusses the equilibrium prices and demands of these three subgames.

Lemma 3. When at least one manufacturer adopts the low-end product line strategy, Table 3 presents the equilibrium prices in the , and subgames. As shown in

Table 3, assuming that the high-quality manufacturer adopts the

N or

strategy and remains unchanged, it will only affect the low-quality manufacturer but not the competitor if the low-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy (a low-end product line strategy). Specifically, the low-quality manufacturer’s retail price remains unchanged and retail demand decreases, but the high-quality manufacturer’s retail price and retail demand remain unchanged. This shows that when the low-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy, some of its consumers will switch from its retail channel to its rental channel. Assuming that the low-quality manufacturer adopts the

N or

strategy and remains unchanged, it will affect both manufacturers if the high-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy. Specifically, both manufacturer’s retail prices decreases, and the high-quality manufacturer’s retail demand decreases and the low-quality manufacturer’s retail demand increases. This shows that when the high-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy, some of its consumers will switch from its retail channel to its competitor’s retail channel.

Proof of Lemma 3. , and subgames: In subgame, manufacturer L offers the no-product line strategy and manufacturers H offers the strategy. We have , , , and . If , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer H, otherwise, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer L. The retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P and B2C platform of the manufacturer H are , and , and the retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P platform of the manufacturer L is and . The competing manufacturers ‘s equilibrium profits are and . From the first order conditions (FOC), by solving and , we obtain the equilibrium prices of competing manufacturers are , and . Then, the manufacturers’ equilibrium profits are and .

In subgame, manufacturer H offers the no-product line strategy and manufacturer L offers the strategy. We have , , and , , . If , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer L, otherwise, if , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer L. The retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P platform of manufacturer H are and , and the retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P and B2C platform of manufacturer L are , and . Then the manufacturers’ profits are and . From the first order conditions (FOC), by solving and , we obtain the equilibrium prices of the competing manufacturers are , , and . Then, the equilibrium profits of the competing manufacturers are and .

In subgame, both manufacturers offer the strategy. We have , , , , , . If , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer L, otherwise, if , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer L. The retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P and B2C platform of the manufacturer H are , and . The retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P and B2C platform of the manufacturer L are , and . Then the equilibrium profits of the competing manufacturers are and . From the first order conditions (FOC), by solving and , we obtain the competing manufacturers’ equilibrium prices are , , and . The competing manufacturers’ equilibrium profits are and . □

4.2.4. One Manufacturer Adopts the Strategy and the Other Adopts the Strategy

We analyze the case where one manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy and the other manufacturer adopts the low-end product line strategy, i.e., and subgames. We present the equilibrium outcomes in the following lemma.

Lemma 4. When one manufacturer adopts the low-end product line strategy while the other manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy, Table 4 presents the equilibrium prices and demands in the and subgames. Assuming that the competitor adopts any strategy and keeps the strategy unchanged, the effects of the manufacturer adopting the / strategy on the prices and demands of the two manufacturers are consistent with Lemma 1 and Lemma 2, and are not affected by the competitor’s strategy.

Proof of Lemma 4. and subgames: In subgame, manufacturer L offers the strategy and manufacturer H offers the strategy. We have , , , , and, . If , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer L, otherwise, if , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer L. The retail demand and the size of renters on the B2C and P2P platform of the manufacturer H are , and . The retail demand and the size of renters on the B2C and P2P platform of the manufacturer L are , and . Then the competing manufacturers’ equilibrium profits are and . From the first order conditions (FOC), by solving and , we obtain the equilibrium prices are , , and . The competing manufacturers’ equilibrium profits are and .

In subgame, manufacturer L offers the strategy and manufacturer H offers the strategy. We have , , , , and , . If , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer H, if , consumers will rent products of quality from the B2C platform of manufacturer L, otherwise, if , consumers will buy or rent products of quality from the P2P platform of manufacturer L. The retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P and B2C platform of the manufacturer H are , and . The retail demand and the size of renters on the P2P and B2C platform of the manufacturer L are , and . Then the profits are and . From the first order conditions (FOC), by solving and , we obtain the equilibrium prices are , , and . The manufacturers’ equilibrium profits are and . □

4.3. Equilibrium Analysis

We now consider stage 1, where the manufacturer decides which product line strategy to adopt. The following proposition summarizes this conclusion.

Proposition 1. The high-quality manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy, and the low-quality manufacturer adopts the low-end product line strategy, i.e.,

is the unique equilibrium.

Proof of Proposition 1. We analyze the competitive manufacturer’s equilibrium strategy by comparing the equilibrium outcomes of each subgame. Note that , so that , , and . Note that , so that , , and . Then, subgames , , and need to be compared. , we have for any , Because we assume , then when , , so that . Note that , we have for any , so we have when , so that . Note that , because , so that , then . Therefore, is the unique equilibrium. This completes the proof of Proposition 1. □

The high-quality (low-quality) product line strategy allows the high-quality (low-quality) manufacturer to extract the maximum surplus from their customers based on the customer’s valuation and the price offered by the competitor, which expands the market size to the high (low) end and increases profit margins. Therefore, assuming that the competitor’s strategy remains unchanged, the high-quality (low-quality) manufacturer will benefit (relative to the competitor) by switching from the no-product line strategy to the high-quality (low-quality) product line strategy. If the high-quality (low-quality) manufacturer adopts the high-quality (low-quality) product line strategy, for the low-quality (high-quality) manufacturer, adopting low-quality (high-quality) product line strategy will make it less attractive to high-end (higher-end) consumers, but adopting high-quality (low-quality) product lines will intensify competition and lose some consumer markets. Therefore, the high-quality manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy, and the low-quality manufacturer adopts the low-end product line strategy, which is the unique equilibrium.

4.4. Profit Implications

In this section, we compare the profit under the equilibrium strategy with the profit under NN, and analyze the profit implications of the product line strategy.

Proposition 2. Compared with the scenario where both manufacturers adopt no-product line strategy (i.e., NN), the two manufacturers will gain more profit if the low-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy and the high-quality manufacturer adopts the strategy (i.e., ), i.e., and .

Proof of Proposition 2. We compare the subgame and . Note that and , so that and . This completes the proof of Proposition 2. □

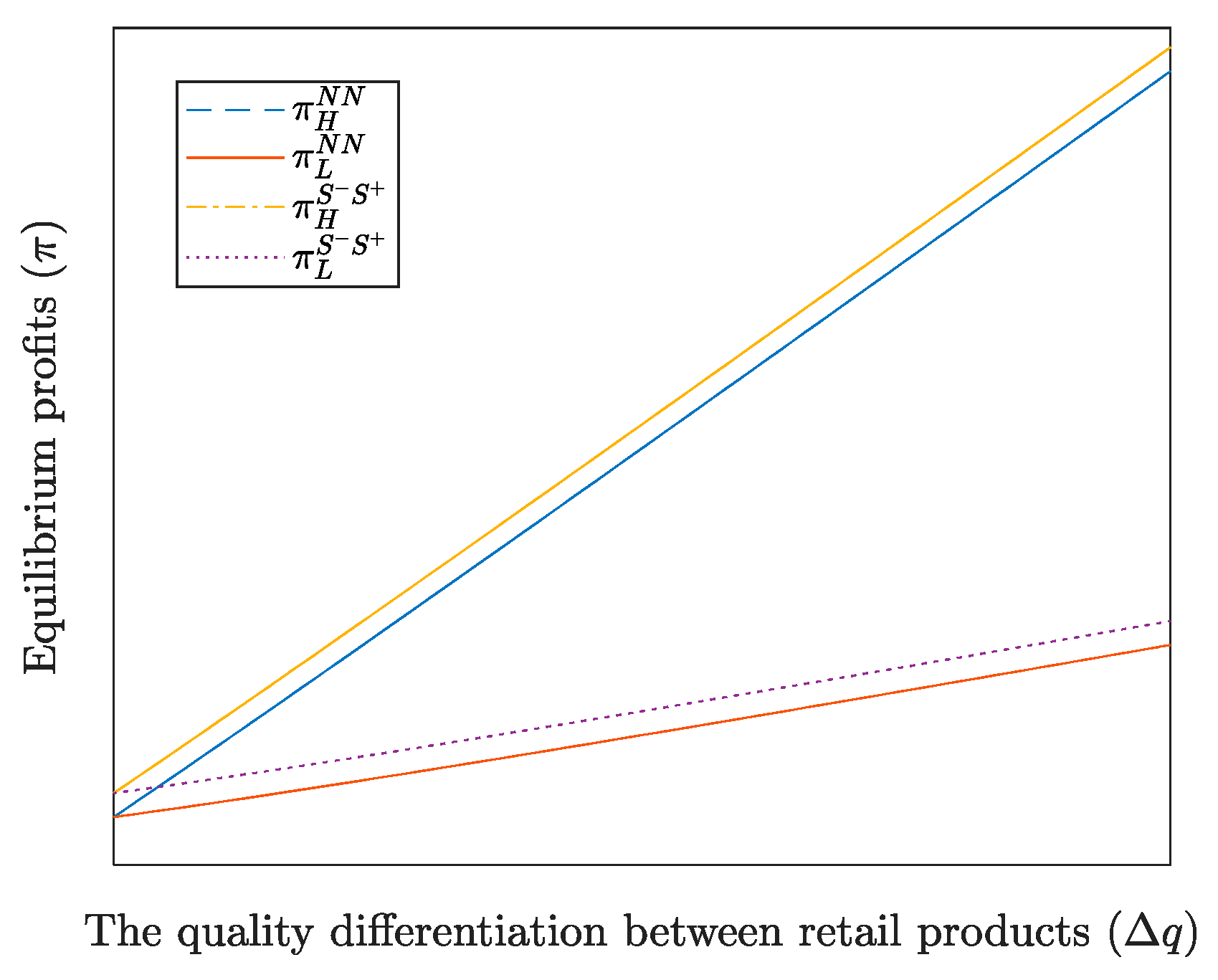

Compared with

NN configuration,

configuration with competing manufacturers is a win-win situation (as shown in

Figure 3). This is because when the low-quality manufacturer adopts the low-end product line strategy and the high-quality manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy, the quality differentiation in the product line expands. The two manufacturers use price discrimination to refine the consumer market. The consumers with low-value will switch from buying low-quality products to renting lower quality products and the consumers with high-value will switch from buying high-quality products to renting higher quality products. The two manufacturers maximize the consumers’ surplus value. Therefore, if the low-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy and the high-quality manufacturer adopts the

strategy, the two manufacturers achieve a win-win situation. The equilibrium leads to a Pareto improvement. In

Appendix A: Case Study, we demonstrated the practical validity of the conclusion through real cases.

5. The Impact of Product Line Strategy on Duopoly

In this section, we discuss the impact of manufacturers’ product line strategy on their equilibrium prices, demands and market sizes.

5.1. The Impact on Equilibrium Prices

Proposition 3. The equilibrium retail price of each subgame is compared as follows:

- (i)

;

- (ii)

.

Proof of Proposition 3. We compare the prices of manufacturers in these subgames. Note that , and , we have , , and . Then, . Note that , , and , we have , and , Therefore, . This completes the proof of Proposition 3. □

Proposition 3 shows that if the high-quality manufacturer switches from the no-product line strategy to the high-end product line strategy and/or the low-quality manufacturer switches from the no-product line strategy to the low-end product line strategy, the retail prices of the two manufacturers will not change. If the high-quality manufacturer switches from the no-product line strategy to the low-end product line strategy and/or the low-quality manufacturer switches from the no-product line strategy to the high-end product line strategy, it will lower the retail prices of the two manufacturers. This is because the high-quality manufacturer offers the high-quality product line strategy and/or the low-quality manufacturer offers the low-quality product line strategy, quality differentiation within product lines expands. The manufacturer uses the price discrimination effect to attract consumers by setting a lower or higher rental price without reducing the retail price. However, the high-quality manufacturer provides the low-quality product line strategy and/or the low-quality manufacturer provides the high-quality product line strategy, quality differentiation within product line decreases, resulting in fierce price competition, and then the manufacturers have to choose to lower the retail prices to attract consumers.

5.2. The Impact on Retail Demands

Proposition 4. The equilibrium retail demand of each subgame is compared as follows:

- (i)

;

- (ii)

.

Proof of Proposition 4. We compare the retail demand of manufacturers in these subgames. Note that , and , because Then, . . Note that . Then, and . Note that , and . Note that , because we have assumed , so that . Then . Note that . Then and . This completes the proof of Proposition 4. □

Proposition 4 shows that if the low-quality (or high-quality) manufacturer switches from the no-product line strategy to the low-end (or high-end) product line strategy, its retail demand will decrease but the competitor’s retail demand will remain unchanged. This is because such a product line strategy expands the quality differentiation between channels and alleviates the cannibalization of the market. When the low-end (high-end) manufacturer rents low-quality (high-quality) products, some low-end (high-end) consumers who plan to buy the product will rent low-quality (high-quality) products, but the high-end (low-end) consumers are not affected. However, if the high-quality (low-quality) manufacturer switches from the no-product-line strategy to the low-end (high-end) product-line strategy, its retail demand will decrease but the retail demand of competitors will increase or decrease. This is because such a product line strategy intensifies cannibalization and leads to fierce price competition. When the low-end (high-end) manufacturer rents high-quality (low-quality) products, some consumers in the middle segment will choose competitors’ products, and the competitors’ retail demand will be affected by its pricing decision.

5.3. The Impact on Market Sizes

The market size of manufacturer includes the retail demand, the rental demand on its P2P platform, and the rental demand on its B2C platform, and is represented by . The following propositions compare the market sizes of the manufacturers.

Proposition 5. The equilibrium market size of each subgame is compared as follows:

- (i)

;

- (ii)

.

Proof of Proposition 5. We compare the market size of manufacturers in these subgames. Note that and . Note that and , because , so that , , that is . Then, . Note that and . Note that and , because , so that and , that is . Then . This completes the proof of Proposition 5. □

Proposition 5 shows that the market size of the two manufacturers will remain unchanged if the high-quality manufacturer switches from the no-product line strategy to the high-end product line strategy and/or the low-quality manufacturer switches from the no-product line strategy to the low-end product line strategy. If the high-quality manufacturer switches from the no-product line strategy to the low-end product line strategy and/or the low-quality manufacturer switches from the no-product line strategy to the high-end product line strategy, the market size of the high-quality manufacturer increases and that of the low-quality manufacturer decreases. This is because if the high-quality manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy and/or the low-quality manufacturer adopts the low-quality product line strategy, the original consumers of the two manufacturers will only switch from their retail channel to their rental channel, but their respective market sizes remain the same. However, if the high-quality manufacturer adopts the low-end product line strategy and/or the low-quality manufacturer adopts the high-end product line strategy, quality differentiation within product lines decreases, and some consumers who used to choose the low-quality manufacturer will choose the high-quality manufacturer instead.

6. Sensitivity Analysis

While the preceding section shows that manufacturers’ equilibrium strategies () are robust to parameter changes and result in Pareto-improving (win-win) outcomes, this section investigates how key parameters—namely the quality differentiation between retail products () and the quality differentiation between retail and rental products ()—influence profitability under the equilibrium strategies. Let and denote the equilibrium profitability of the high-quality and low-quality manufacturers, respectively.

Based on the model assumptions, the baseline parameters are set as follows: , , , , , , .

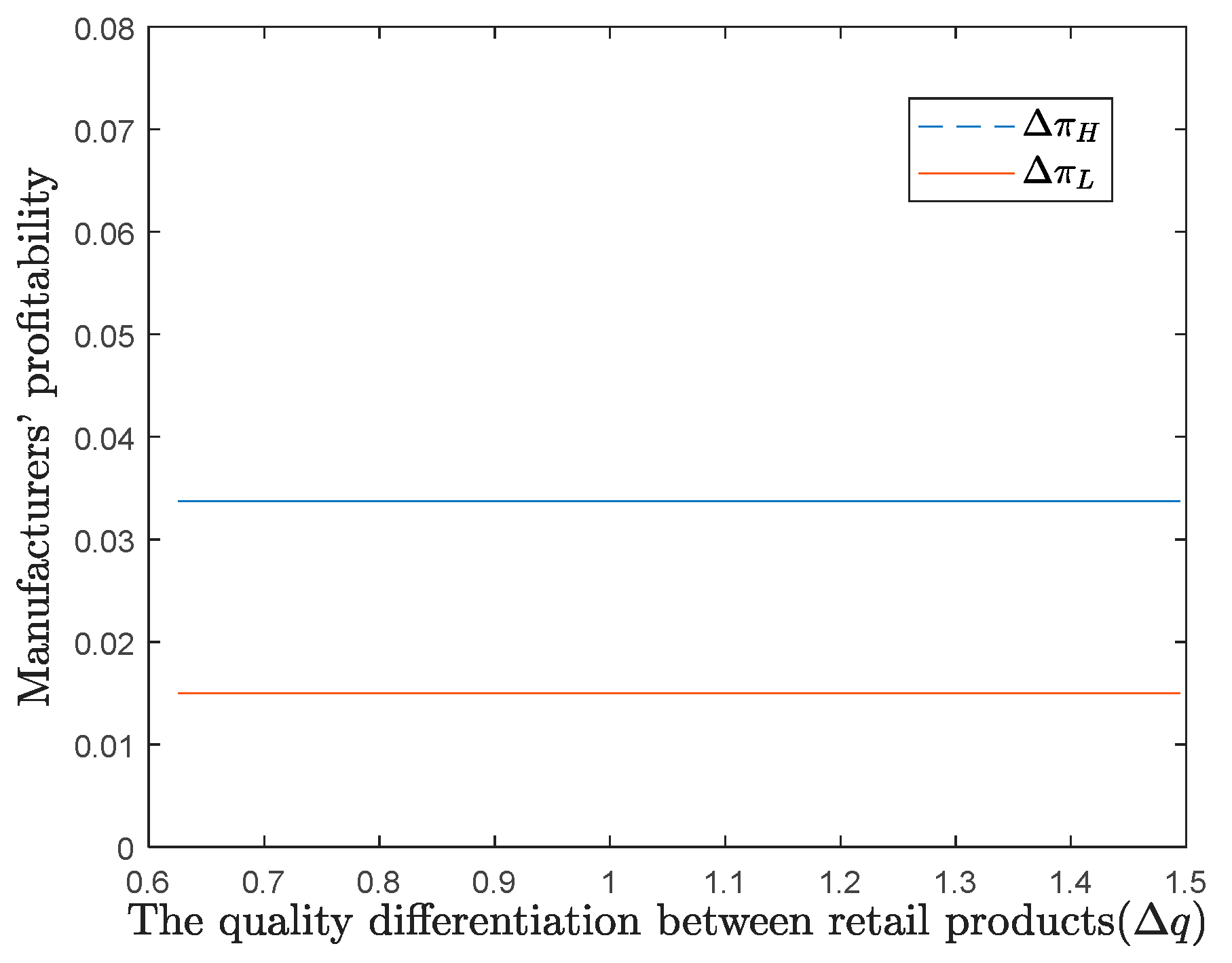

6.1. Quality Differentiation Between Retail Products ()

This subsection analyzes the impact of

on equilibrium profitability (

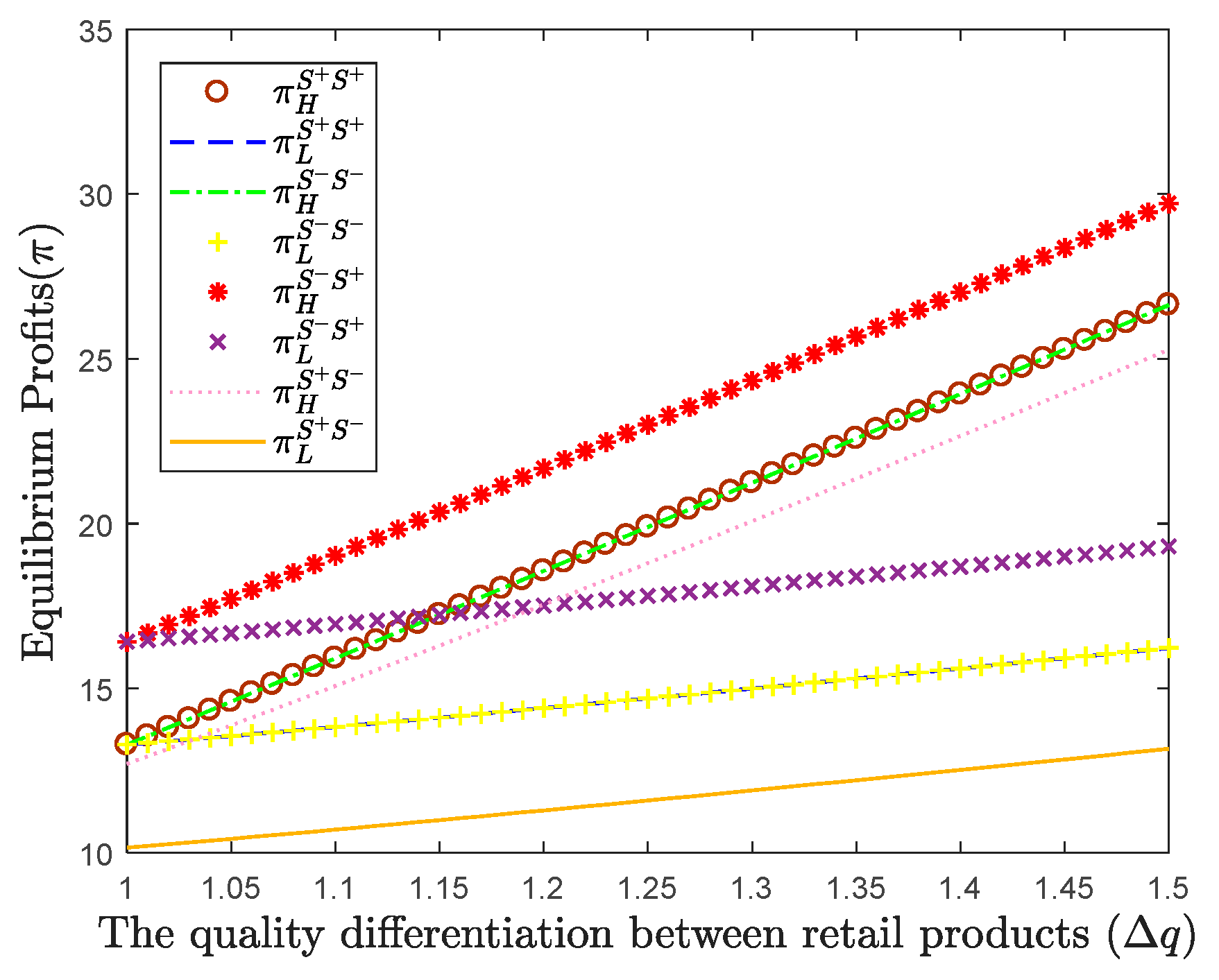

), holding other parameters constant. The results are illustrated in

Figure 4.

As shown in

Figure 4, manufacturers’ profitability remain constant and strictly positive as

increases. This indicates that profitability under equilibrium strategies is unaffected by quality differentiation, and the equilibrium consistently yields a win-win outcome. Thus, competing manufacturers seeking higher profits should focus on adjusting other parameters rather than altering quality differentiation.

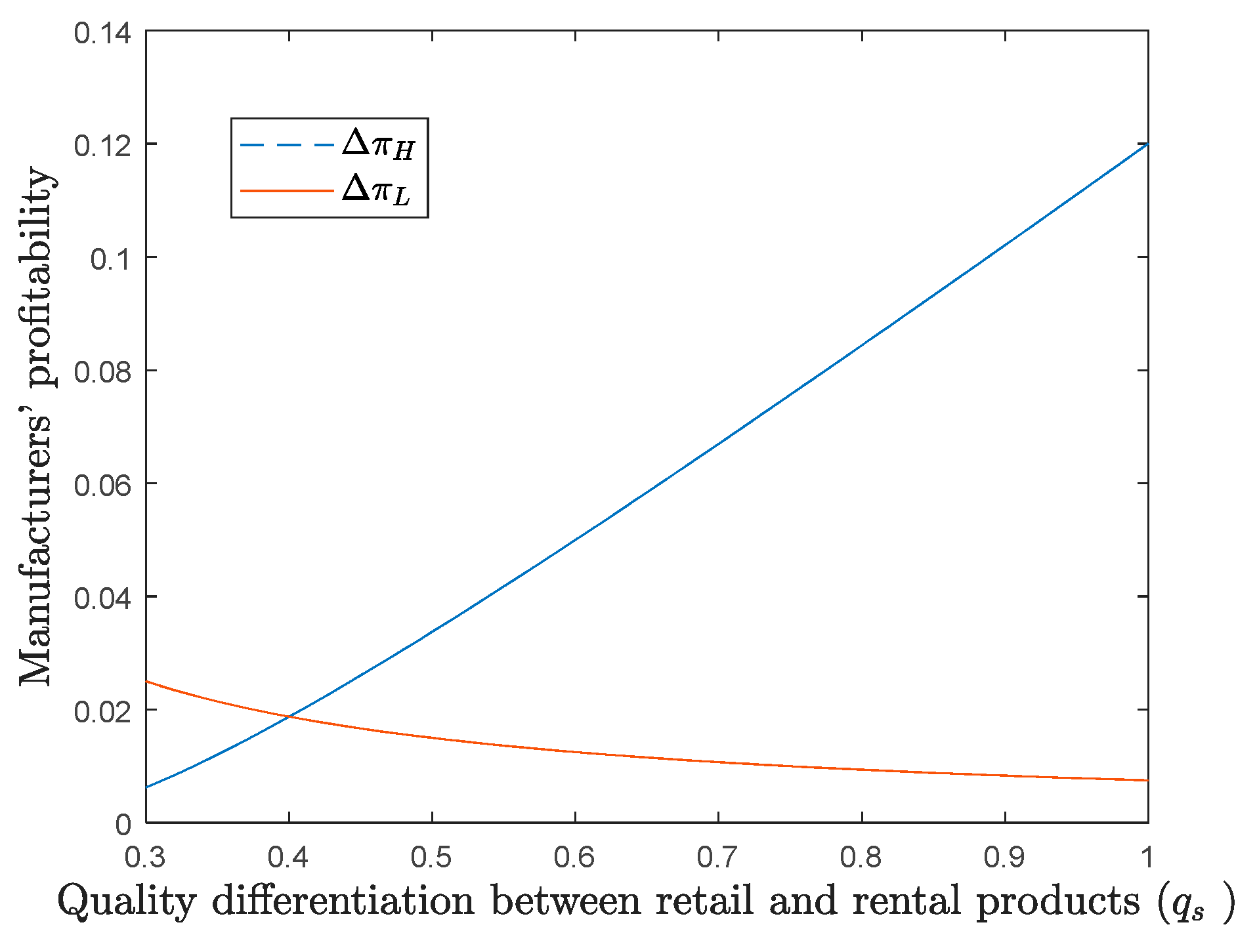

6.2. Quality Differentiation Between Retail and Rental Products ()

We next examine how

influence equilibrium profitability (

), with results presented in

Figure 5.

As demonstrated in

Figure 5, the profitability of high-quality manufacturers increases with the quality differentiation between retail and rental products (

), while low-quality manufacturers experience a corresponding decrease—though both maintain positive profit margins. These findings reveal that while equilibrium strategy profitability remains sensitive to

, the directional effects are diametrically opposed between manufacturer tiers, yet the equilibrium consistently yields mutually beneficial outcomes.

The underlying economic mechanism operates through ’s role in product line differentiation: (a) Increased amplifies vertical differentiation in the product line; (b) This enhanced differentiation strengthens the competitive position of high-quality manufacturers. Simultaneously, it weakens the market position of low-quality competitors. Consequently, profit maximization strategies diverge: High-quality manufacturers benefit from maximizing to reinforce their quality advantage; Low-quality manufacturers achieve optimal returns by minimizing to reduce differentiation.

These results provide empirical support for the strategic importance of quality gap management in competitive product line design. The findings suggest that manufacturers can strategically manipulate quality differentiation () to optimize their profit positions within the market equilibrium, while maintaining the Pareto-efficient properties of the competitive landscape.

7. Extension: The Platform Construction Cost

In practice, establishing a rental platform incurs substantial fixed costs for manufacturers. To extend our baseline model, we incorporate platform construction costs into the analysis. We assume symmetric fixed costs and for both high- and low-quality manufacturers. Under this extension, manufacturer i’s profit when adopting strategy becomes . The equilibrium outcomes under different cost regimes are characterized in Proposition 6.

Proposition 6. - (i)

When

and , is the unique equilibrium;

- (ii)

When and , is the unique equilibrium;

- (iii)

When and , is the unique equilibrium;

- (iv)

When and , is the unique equilibrium.

Proof of Proposition 6. We analyze the competitive manufacturer’s equilibrium strategy. Note that and . According to Proposition 1, if and , is the unique equilibrium. If and , subgames , , and need to be compared. According to Proposition 1, we have , , and . Then, is the unique equilibrium. If and , subgames , , and need to be compared. According to Proposition 1, we have , , and . Therefore, is the unique equilibrium. If and , subgames , , and need to be compared. According to Proposition 1, we have , , and . Therefore, is the unique equilibrium. This completes the proof of Proposition 6. □

Proposition 6 characterizes how platform construction costs shape manufacturers’ equilibrium entry strategies. The results show that the cost thresholds and —which depend on product quality and market competition—play a decisive role in manufacturers’ platform participation.

In case (i), when the platform construction cost remains below both manufacturers’ thresholds, both enter the market, replicating the equilibrium outcomes of the baseline model.

In case (ii), once the cost exceeds the threshold of the low-quality manufacturer () but remains below that of the high-quality manufacturer (), only the high-quality manufacturer sustains platform operation. The low-quality manufacturer exits due to its narrower profit margin in the rental market.

Conversely, in case (iii), should the cost exceed the high-quality manufacturer’s threshold () while remaining affordable for the low-quality manufacturer (), the latter continues operating, whereas the high-quality manufacturer withdraws.

Finally, in case (iv), if the cost surpasses both manufacturers’ thresholds, platform development becomes prohibitively expensive for both, resulting in market exit by all manufacturers.

8. Conclusions

In competitive markets, the design of product lines across retail and rental channels plays a critical role in enabling manufacturers—such as BMW and Daimler—to implement effective product-sharing strategies. This paper investigates a setting where vertically differentiated manufacturers not only sell directly to consumers but also operate peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms that facilitate consumer-to-consumer product sharing. To further engage in rental-based consumption, manufacturers build their own business-to-customer (B2C) platforms, offering products of varying quality levels to segment the rental market.

We develop a vertical duopoly model to examine three representative product line strategies: (1) No product line (no rental on B2C), (2) High-end product line (renting only high-quality products), and (3) Low-end product line (renting only low-quality products). Using a multi-stage non-cooperative game framework, we characterize the strategic decisions of competing manufacturers with quality asymmetry.

Our results reveal that a unique equilibrium emerges in which the high-quality manufacturer chooses the high-end product line strategy, while the low-quality manufacturer adopts the low-end product line strategy. This equilibrium not only reflects each firm’s comparative advantage but also leads to a Pareto improvement, creating a win-win outcome for both manufacturers. The equilibrium mitigates channel conflict, enables effective market segmentation, and improves overall efficiency in the sharing ecosystem. Further analysis shows that product line strategies that expand vertical differentiation effectively reduce cannibalization and soften price competition, while sensitivity analysis confirms that these equilibrium outcomes remain robust across variations in key parameters. In contrast, strategies that compress quality differences intensify internal competition and erode market performance. Thus, aligning product line design with intrinsic product quality is a viable path to balancing efficiency and profitability.

Several extensions could further enrich this research. First, consumer-side transaction costs—such as search friction, trust, or inconvenience—may affect rental decisions, and incorporating them could provide a more realistic view of consumer behavior. Second, while we treat the P2P platform commission rate as exogenous, future work could endogenize it, allowing platforms to strategically set fees through manufacturer bargaining or platform competition, revealing how platform decisions influence product line strategies. Third, our model assumes static product quality; exploring dynamic quality adjustments would enable manufacturers to adapt retail and rental products over time in response to market signals, consumer preferences, or competition. Fourth, incorporating quantifiable sustainability metrics—such as product lifespan extension or carbon emission reduction—could evaluate how product line strategies support circular economy goals in sharing markets. These extensions would advance the understanding of adaptive, platform-oriented, and sustainable product line strategies, offering both theoretical and managerial insights.