6.1. Energy and Overall CO2 Emissions of Renovation Depths

An overview of the energy demand from the assessed renovation scenarios on the building case study is presented in

Figure 18. The figure illustrates a general trend of decreasing energy demand with more extensive renovation interventions, as compared to minor, moderate, and deep renovation cases. This finding echoes existing findings from Italy [

69], indicating that the more extensive the renovations are in terms of energy optimisation, the greater the decrease in building energy demand. This trend is also observed in scenarios worthy of preservation and listing protection, as compared to renovation scenarios within each of these categories. This leads to the conclusion that renovating the building will result in energy savings if the renovation improves its energy efficiency measures. The degree of improvement depends on the building’s original energy needs.

The results of the LCA calculations for the 18 scenarios and the baseline are presented in

Figure 19. The results cannot be directly compared across renovation depths because the scope applied in the calculation for minor renovation differs from that applied to the remaining four renovation depths, as described in

Section 3.

In the three minor renovation cases, emissions increase with increasing renovation depth. This change is observed without affecting the expected energy use, resulting in the renovation adding embodied carbon to the project without any trade-off with operational carbon.

For moderate renovations, the GWP decreases slightly from scenario 1 to 3, as the embodied carbon from added materials reduces energy use, thereby lowering the building’s overall GWP. Likewise, between the moderate renovation scenarios 3 and 5, the building’s GWP increases even as its energy use decreases. This is caused by energy savings being offset by increased embodied carbon emissions in A1-A5 and C3-C4. In the moderate renovation scenarios, the point at which the payback time for the carbon investment (as defined in [

63]) exceeds the building’s expected lifetime renders the renovation efforts introduced between scenarios 3 and 5 unsuitable from a purely environmental perspective. This finding aligns with the works of Huuhka et al. [

70], showing that the reference study period is of significant importance when assessing the suitability of a renovation intervention for reducing CO

2 emissions.

Comparing the energy use for the deep renovation (see

Figure 18) with the CO

2 emissions from the same scenarios further highlights the trend observed in the latter half of the moderate renovation scenarios, where an increase in embodied carbon is counterbalancing the reduction in operational carbon. This results in an overarching increase in GWP despite an apparent decrease in energy use. This indicates that the deep renovation scenarios all assess renovation activities for which the payback time for the carbon investment exceeds the reference study period.

In renovation scenarios for both worthy of preservation and listing protection, there is a decrease in emissions between scenarios 1 to 3, due to the significant reduction in building energy use. Between scenarios 3 and 4 in the worthy of preservation renovations, the GWP is increasing due to the lack of improvement in the building’s energy performance. Even though it is outside the focus of this study, other studies have previously found that renovating, restoring, or transforming buildings can still be worth it from an environmental perspective if the alternative is to tear down the existing building and build a new one [

48,

70]. The assessed scenarios for both worthy of preservation and listing protected buildings are limited by existing regulations that restrict the changes allowed during renovation or transformation.

Comparing the baseline emissions to those associated with the renovation scenarios reveals a significant difference in kg CO

2 emissions/m

2/year. These results, however, are not directly comparable due to the differences in the scope of the LCAs. The scope of the baseline LCA is based on the scope often applied to new construction buildings, following the methodology in BR18 [

41]. In this light, LCA is conducted as if the building were constructed today, including embodied carbon and maintenance for all existing building parts, and energy use is calculated using Be18 [

56]. On the contrary, the scope of the LCA for the renovation cases includes only the embodied carbon from the building parts that are replaced or added during the renovation, as well as the continuous maintenance of these parts, and the energy use for moderate, deep, worthy of preservation, and listed protected scenarios.

This methodological choice has two key implications. On the one hand, this means no direct comparison can be made between the baseline and the renovation cases due to differences in scope. On the other hand, the risk of double-counting materials or processes [

71] are limited by excluding existing materials and structures from the renovation LCA, as this establishes clear boundaries for which life cycle of the building a given process belongs. The choice to exclude the maintenance and demolition of existing materials is also aligned with the LCA method used in the Danish version of the sustainability certification systems, i.e., DGNB [

72].

The comparability of the results from renovation cases with emissions from newly constructed buildings is debated in the literature and in existing methodologies. In the work by Arkitema, COWI, BUILD Aalborg Universitet and Rådet for Bæredygtigt Byggeri [

48], it is suggested that the emissions for renovated buildings should include maintenance of existing building parts as well, while the alternative of constructing a new building should consist of the emissions associated with tearing down the existing building. At the other end of the spectrum, the Danish version of the DGNB [

64] system suggests that LCA for renovation cases should assess only the emissions associated with newly added materials, thereby aligning with the methodology applied in this study. Both the Danish DGNB system [

72] and BR18 [

41] do not require an LCA assessment for new buildings to include the demolition of the existing building, thereby establishing a clear distinction between the different life cycles of the buildings and limiting the theoretical risk of double-counting.

In all scenarios assessed, due to the lack of available data regarding the construction and operation of the case building, both the LCA and the energy calculation include uncertainties. Consequently, the presented results cannot be expected to directly correspond to changes in energy demand or to the building’s actual GWP.

Former studies show that the variation in GWP between comparable generic EPDs can significantly impact the result of LCAs for buildings [

73,

74], with one study even finding variations of up to 1500% in GWP between comparable isolation materials [

73]. To limit the uncertainty resulting from data quality, this study utilised generic EPD data and kept the selected dataset constant across scenarios. This methodological choice means that changes in GWP between scenarios are due to the actual change described in the scenarios, rather than to changes in the assigned EPD. The choice of using generic EPDs aligns with the LCA method presented in BR18 [

41] as well as the method applied in practice in the early design stages, when exact material choices have not been made yet [

73].

The calculated energy use is not expected to reflect the building’s actual energy use, due to the performance gap [

75], which is also present in the Danish Be18 tool [

56]. Previous studies have been conducted on Be18’s predecessor, Be10, showing a significant gap between the calculated and the realised electricity and heat demand [

76,

77]. The LCA study presented in this paper maintains a consistent calculation method across renovation scenarios, and the errors in energy-use calculations are assumed to be constant. Further adding to the validity of using Be18 as the tool for calculating the energy demand of the building is the Danish building regulations’ requirement to use the tool for both the energy calculation [

45], and as the basis for the energy demand in the LCA calculation [

41].

In both moderate and deep renovation scenarios, the GWP of the renovation cases is comparable in range to the emissions identified for 23 renovation cases by Zimmerman et al. [

78]. This supports that the presented results are of a magnitude comparable to and realistic for renovation cases in Denmark.

A further limitation in the study is the lack of structural assessment of the building in both the pre- and post-renovation scenarios. The study assumes that the renovation scenarios do not involve any significant structural modifications. It is therefore presumed that there is no need to strengthen or adapt the building’s static system. Even though this simplifies the modelling process, it may lead to overlooking environmental aspects of potential structural interventions in more complex, deeper renovation scenarios.

6.2. Limit Values

Existing work [

47,

79] has strived to develop a limit-value-based approach for different building renovation scopes, where Lund et al. [

79] have defined limit values at the building and building element levels. The results presented in

Section 5 and

Section 6 of this paper show significant variations in environmental impacts depending on the depth of the renovation. As current knowledge of LCAs for building renovation projects in Denmark is very limited, there is insufficient data to establish limit values for the GWP. This is evident in the significant variance in the GWP associated with the renovations and in the substantial variation in the complexity of the renovation depths, for example, between replacing outer doors and a complete façade replacement.

The results of the LCA for minor renovation cases are not comparable to those of the remaining cases due to methodological differences between these LCAs and the other cases. The methodological differences align with the variations in project complexity and monetary value. Given the lack of, or insignificant changes to, the building’s energy use due to minor renovations, this renovation aligns with some of the suggestions by Lund et al. [

79], where limit values should be enforced at the building element level.

For moderate and deep renovations, the study demonstrates that there is a point beyond which further renovation activities do not improve the building’s energy performance to an extent that offsets the increased embodied carbon within the reference study period (as seen between deep renovation 2 and 3 in

Figure 19). The study therefore indicates that there is a point at which further energy renovation measures cease to yield benefits from a carbon-reduction perspective. That is because additional renovation measures generate more upfront carbon than the reductions in operational emissions from lower energy demand. These findings suggest that applying exact limit values for deep and moderate building renovations might not be beneficial, as it poses the risk of simplifying complex trade-offs across building life stages. The study, on the other hand, advocates for approaches to building renovation LCAs that could build upon a carbon payback time perspective within a set time period [

63]. This would mean that the embodied carbon associated with initiatives to limit the building’s energy use should not exceed the GWP reduction from the building’s operations during the set payback period.

Both buildings, worthy of preservation and those listed for protection, are exempt from certain energy performance rules when renovated under the Danish building regulation [

45], acknowledging the limited changes that can be made to the buildings due to their protected status based on cultural heritage and historic importance. The study indicates that this exemption could also be extended to cover a potential future LCA requirement for building renovations, as renovating buildings worthy of preservation or listed as protected is already a complex action due to the limitations on changes allowed to the building.

6.3. Assessment of Uncertainty in Calculations

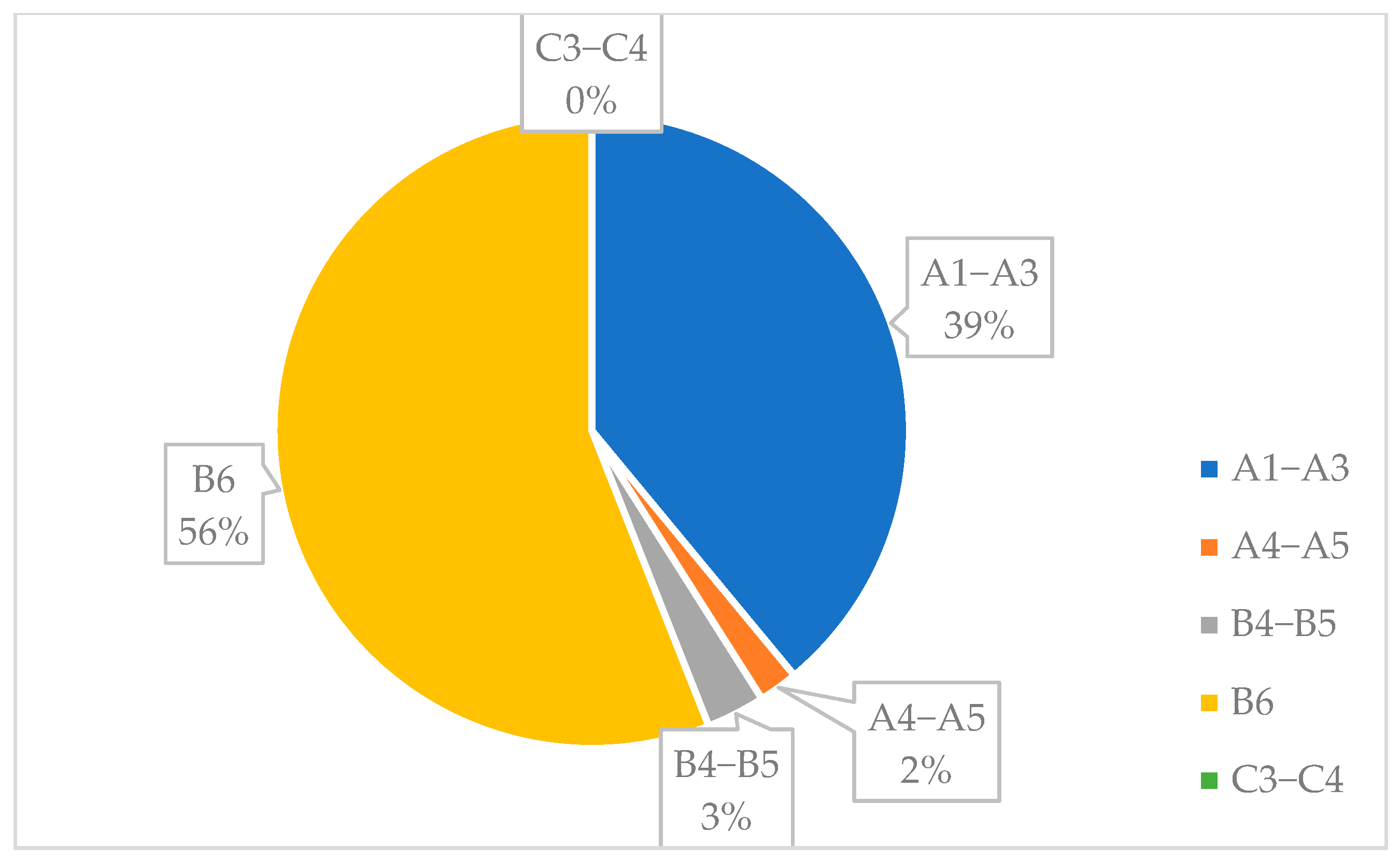

The majority of CO

2 emissions across all renovation scenarios are associated with building energy use (module B6), as illustrated in

Figure 19. To reflect the distinct characteristics of operational and embodied emissions, the uncertainty analysis is divided into two independent assessments.

Operational energy use calculated with the Be18 method introduces uncertainty in the form of a performance gap, defined as the difference between calculated and actual energy use. Under worst-case conditions, this gap may result in energy consumption up to 20% higher than the calculated values, as elaborated in [

77]. This scenario accounts for two key limitations: (i) reliance on the Danish Design Reference Year (DRY), which does not represent actual annual weather conditions, and (ii) the assumption of a single thermal zone for the entire building, which fails to capture real thermal dynamics and leads to inaccuracies in heating and cooling demand estimates.

The resulting differences in operational impacts across the assessed scenarios are presented in

Figure 20, which serves as a visual summary of the uncertainty assessment in operational CO

2 emissions. Operational uncertainty is evaluated only for the moderate, deep, and preservation/listing protection scenarios, as minor renovation scenarios do not influence the building’s energy performance. Each scenario is depicted with two bars: the expected value, based on Be18-calculated energy use (as shown in

Figure 18), and the worst-case estimate, which assumes a 20% increase in operational energy use.

This dual representation highlights the sensitivity of emissions outcomes to variations in energy performance assumptions. The figure underscores how even scenarios with relatively low expected emissions can exhibit substantial uncertainty, with worst-case values significantly exceeding expectations. By explicitly visualising this range, the analysis emphasises the importance of incorporating uncertainty into environmental impact assessments to enable more resilient, informed decision-making.

The assessment of embodied carbon relies on generic datasets from OneClickLCA. These datasets carry an uncertainty of up to ±34.64%, calculated according to the Carbon Leadership Forum methodology [

80]. This uncertainty is applied to the calculated embodied carbon to generate best- and worst-case scenarios. The best-case scenario assumes that embodied carbon is 34.64% lower than the values stated in the generic datasets, while the worst-case scenario assumes it is 34.64% higher. The expected scenario corresponds to the embodied carbon values presented in

Figure 19, excluding module B6, which was assessed separately in

Figure 20. The resulting best-case, worst-case, and expected scenarios for embodied carbon are shown in

Figure 21. This figure provides a focused uncertainty assessment by visually comparing the range of potential outcomes across different preservation and renovation scenarios. Each scenario is represented by three bars, clearly illustrating how dataset variability can significantly influence the results. The wide spread between best- and worst-case values highlights the sensitivity of embodied carbon estimates to input assumptions, reinforcing that uncertainty is not a marginal factor but a central consideration in lifecycle assessments. By explicitly incorporating these uncertainty bounds, the figure strengthens the credibility and transparency of the analysis, ensuring that a realistic range informs environmental decisions of possible impacts.

Comparison of

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 indicates that the largest absolute uncertainty arises from operational carbon, since module B6 accounts for a substantial share of lifetime building emissions.

6.4. Conclusions

This paper examined existing methodologies for conducting LCAs in building renovation projects in Denmark. Drawing on existing approaches outlined in the Danish building regulations, as well as various reports from both private and public entities [

42,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51], this study proposed two distinct LCA methodologies. For minor renovations that do not impact energy use, an LCA focusing solely on embodied carbon is recommended for straightforward material/building element comparisons. This approach aligns with the recommendations of Lund et al. [

72] to establish benchmark values at the building element level. For moderate and deep renovations, the study suggests aligning LCA studies with Danish regulations and conducting the LCA only for newly added materials. The study’s findings also indicate that energy renovations can reach a point where further improvements do not significantly reduce the GWP.

Furthermore, the study underscores the importance of conducting LCAs for renovation projects in the Danish context. It critically addresses the lack of a standardised methodology and proposes various LCA frameworks tailored to different levels of intervention in renovation practices. The implementation of LCA in the Danish construction sector is gaining momentum, prompting efforts to establish it as a legal requirement. Concurrently, the Danish government is investigating strategies to make renovation more appealing than demolition or new construction. The lack of a uniform methodology presents challenges in comparing projects and establishing climate-related requirements. Given the diverse range of renovation types and interventions, these variations must be adequately represented in LCA studies. The comprehensive analysis and comparisons presented in this research address this need. Specifically, for renovations categorised as deep and moderate, given that the LCAs provide a spectrum within which the scope profoundly influences the analytical approach. Furthermore, LCA serves as a valuable tool for variant analysis, allowing for the evaluation of design solutions based on their climatic impacts. To establish climate requirements, limit values can be set at both the building and element levels, depending on the degree of renovation.

Challenges remain in comparing projects and establishing climate-related requirements due to methodological inconsistencies. As the analysis is based on a single renovation case, the findings may not be fully generalizable across the diverse range of renovation practices in Denmark. Broader case studies are needed to validate the proposed LCA methodologies and ensure their applicability to varying building types and intervention levels. Moreover, future assessments could incorporate additional LCA modules, such as transportation and D modules, which were excluded here to maintain alignment with Danish regulations. Future work should explore LCA applications in additional renovation cases and further investigate climate requirement benchmarks, as well as the social and economic factors influencing renovation decisions.