Adap-Informer: Adaptive Aircraft Fuel Prediction Framework Supporting Emergency Decision-Making and Aviation Decarbonization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

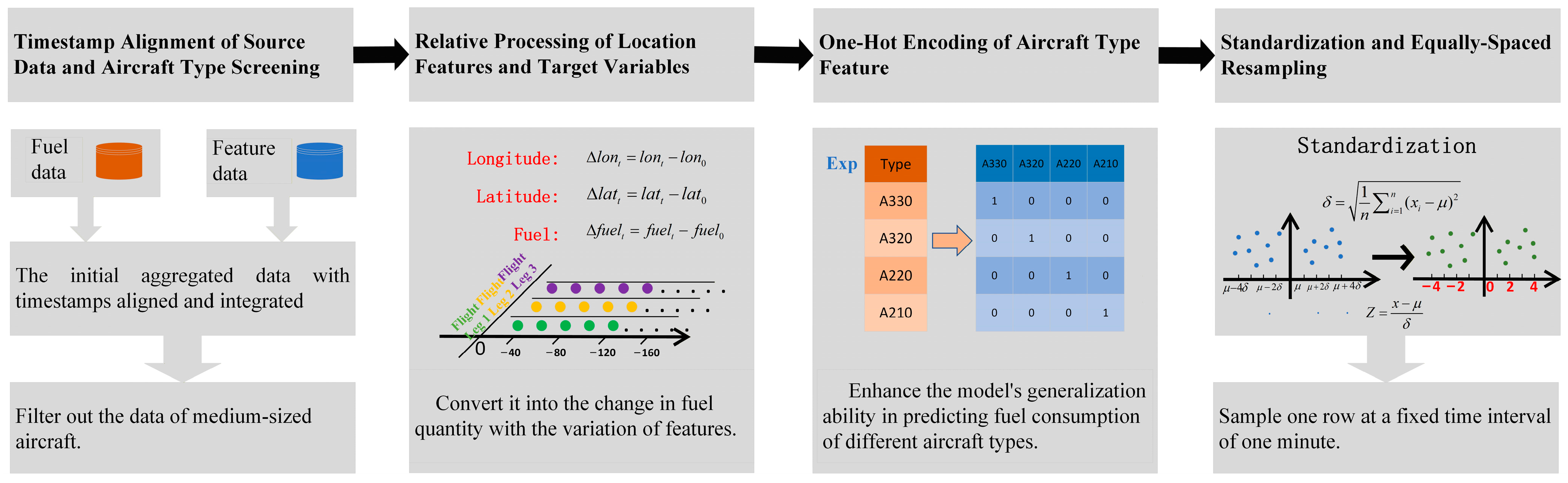

2.1. Data Preprocessing

- : The standardized value

- : A certain value in the original data

- : The mean value of the original data

- : The standard deviation of the original data, and the calculation formula is:

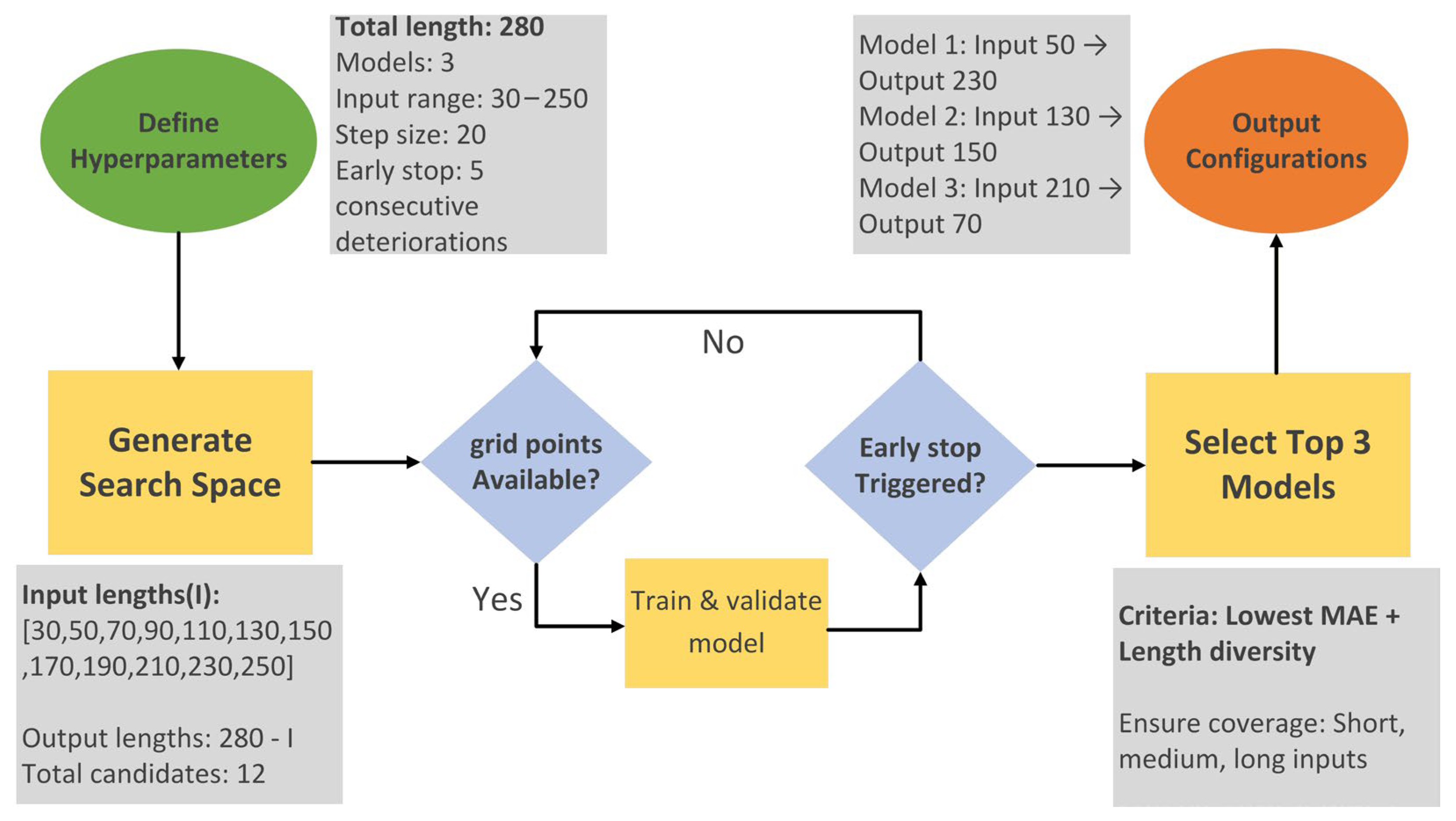

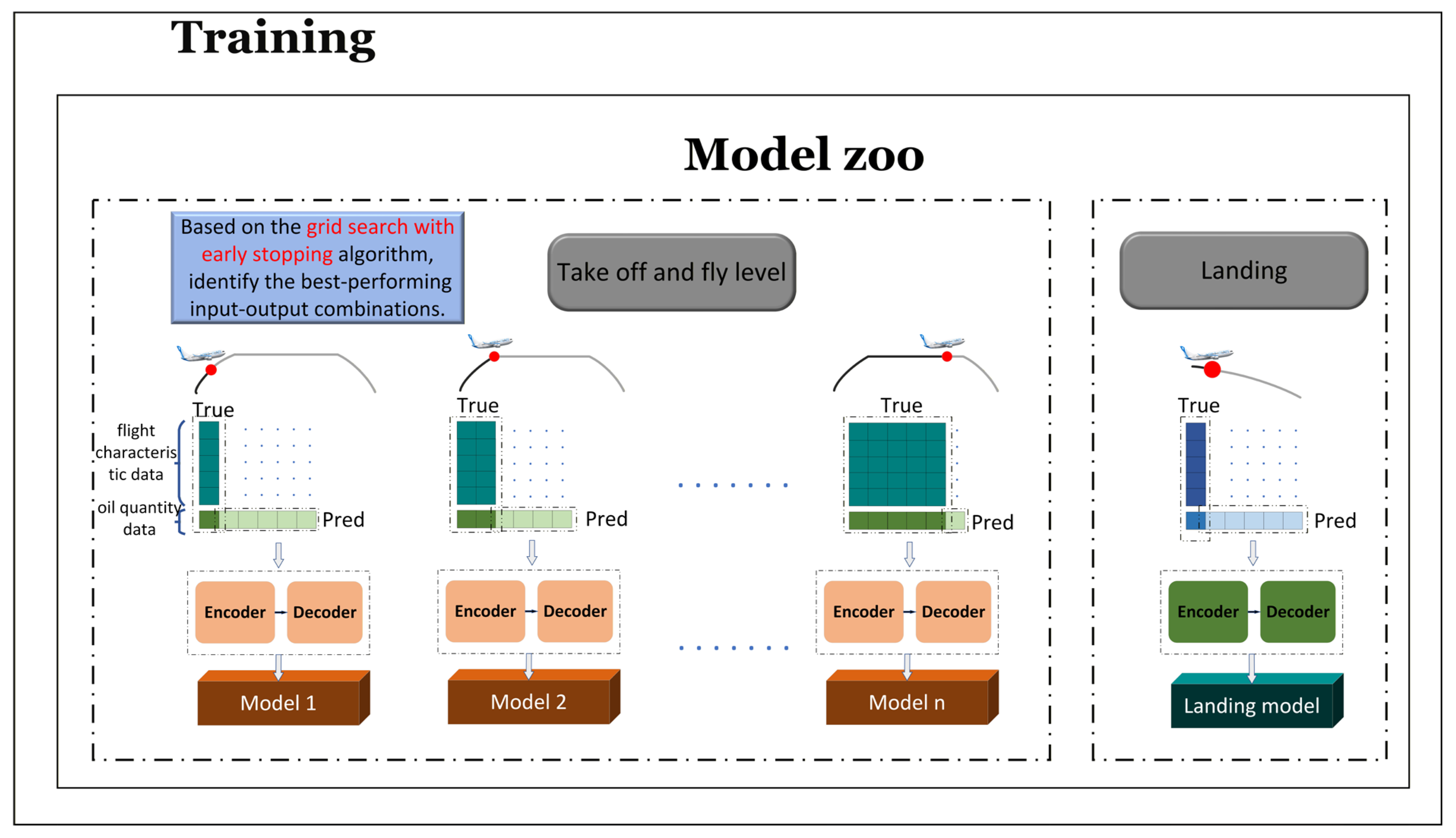

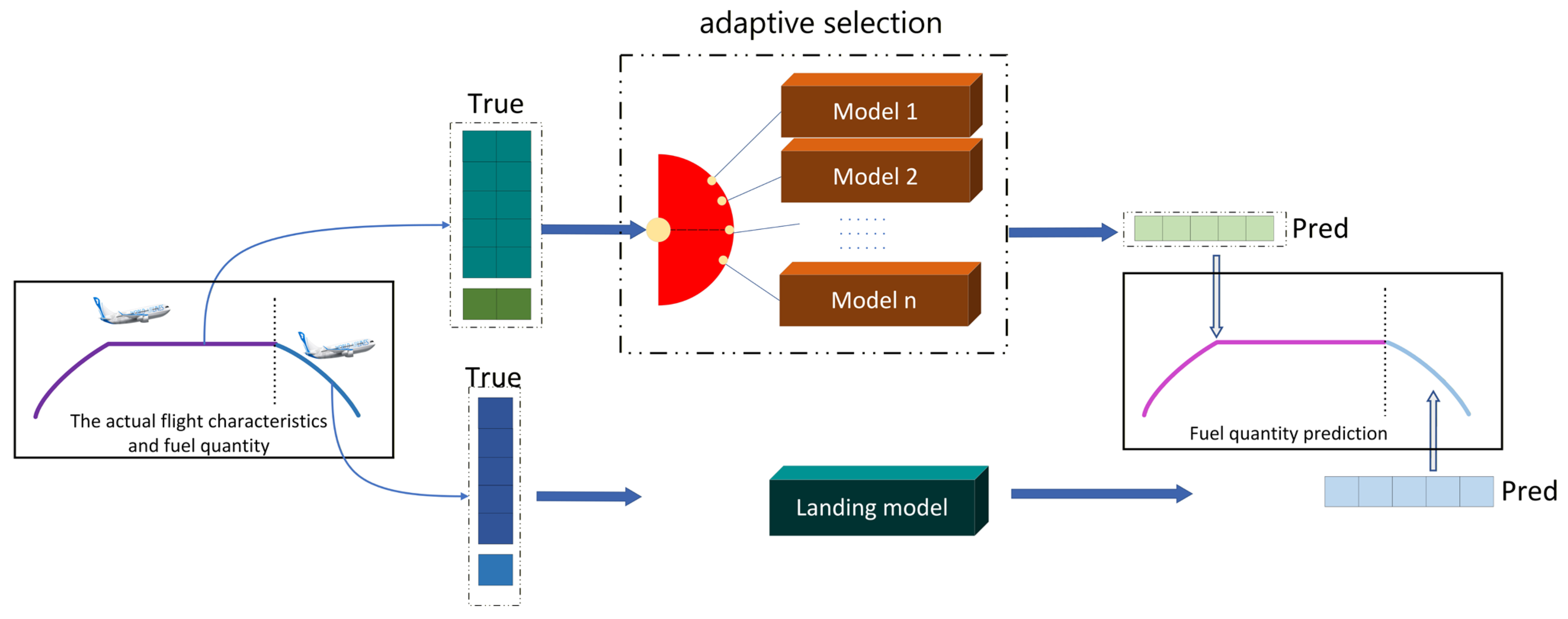

2.2. Adap-Informer

2.3. Regulatory Compliance, Technical Paradigm Selection, and Limitation Mitigation

3. Results and Discussion

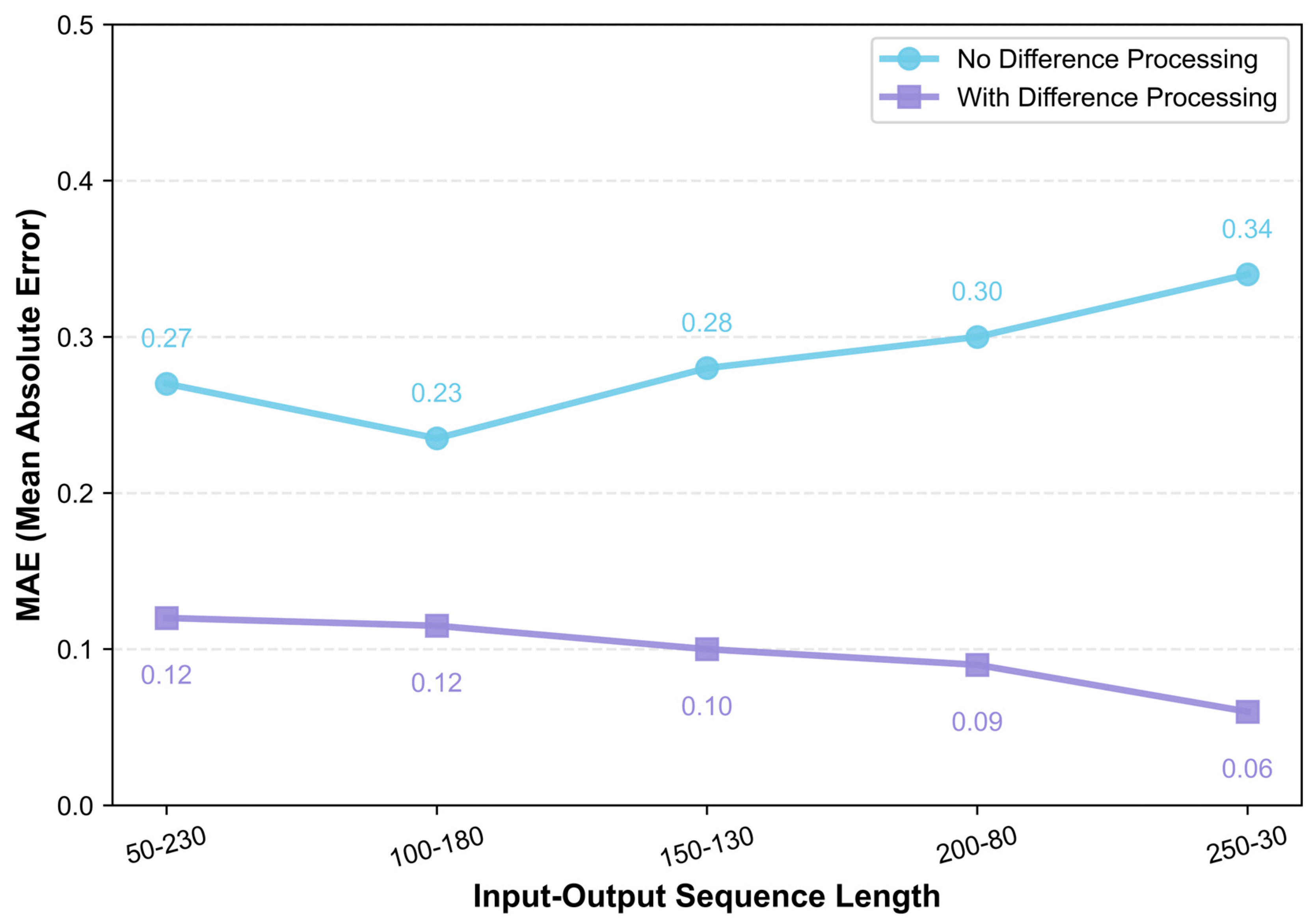

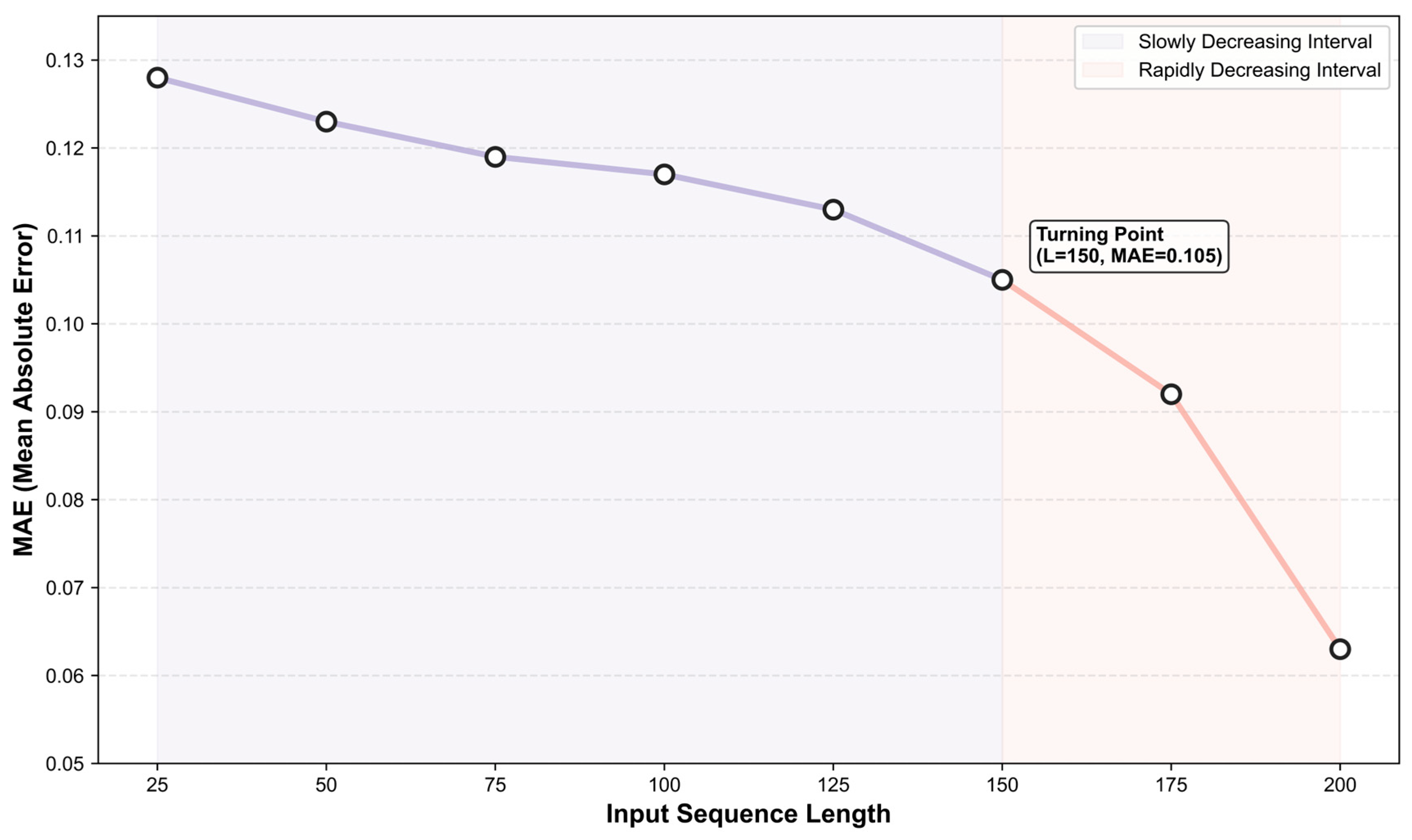

3.1. Input Sequence Length Expansion Experiment

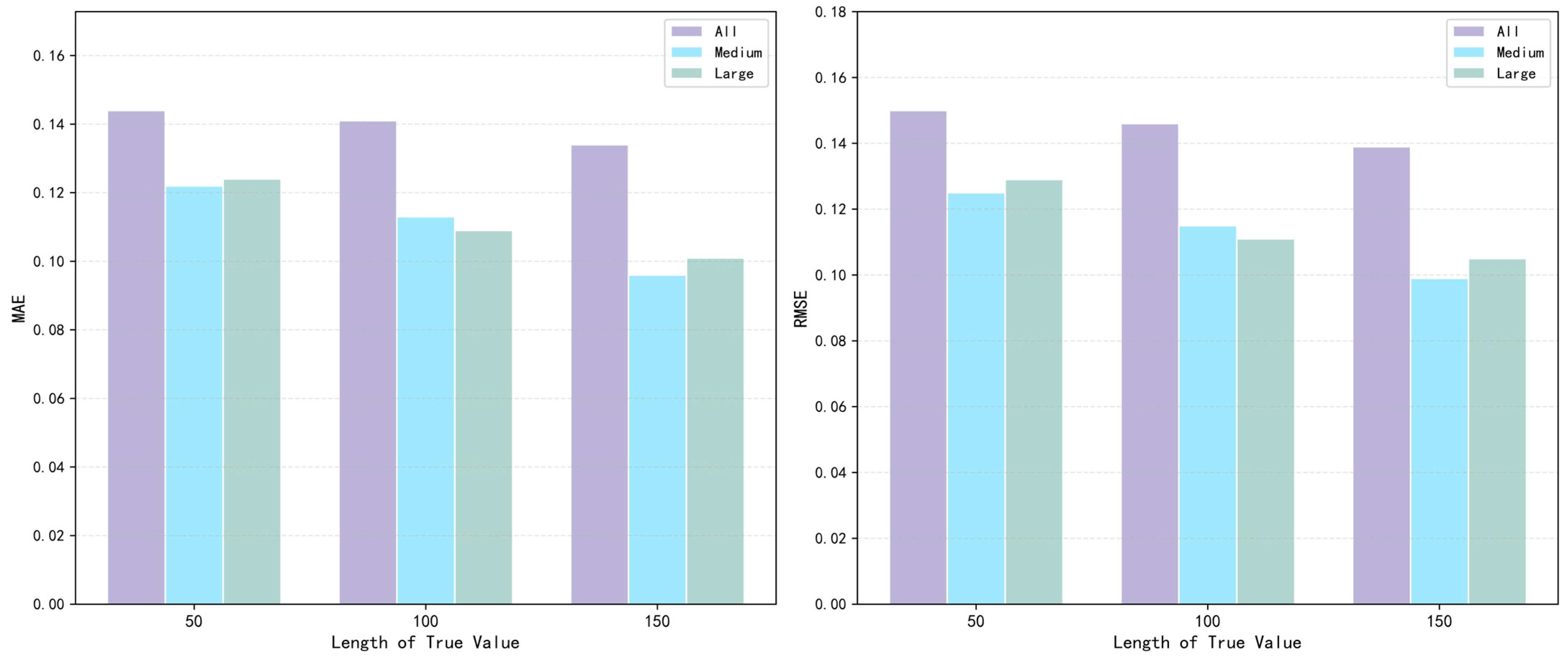

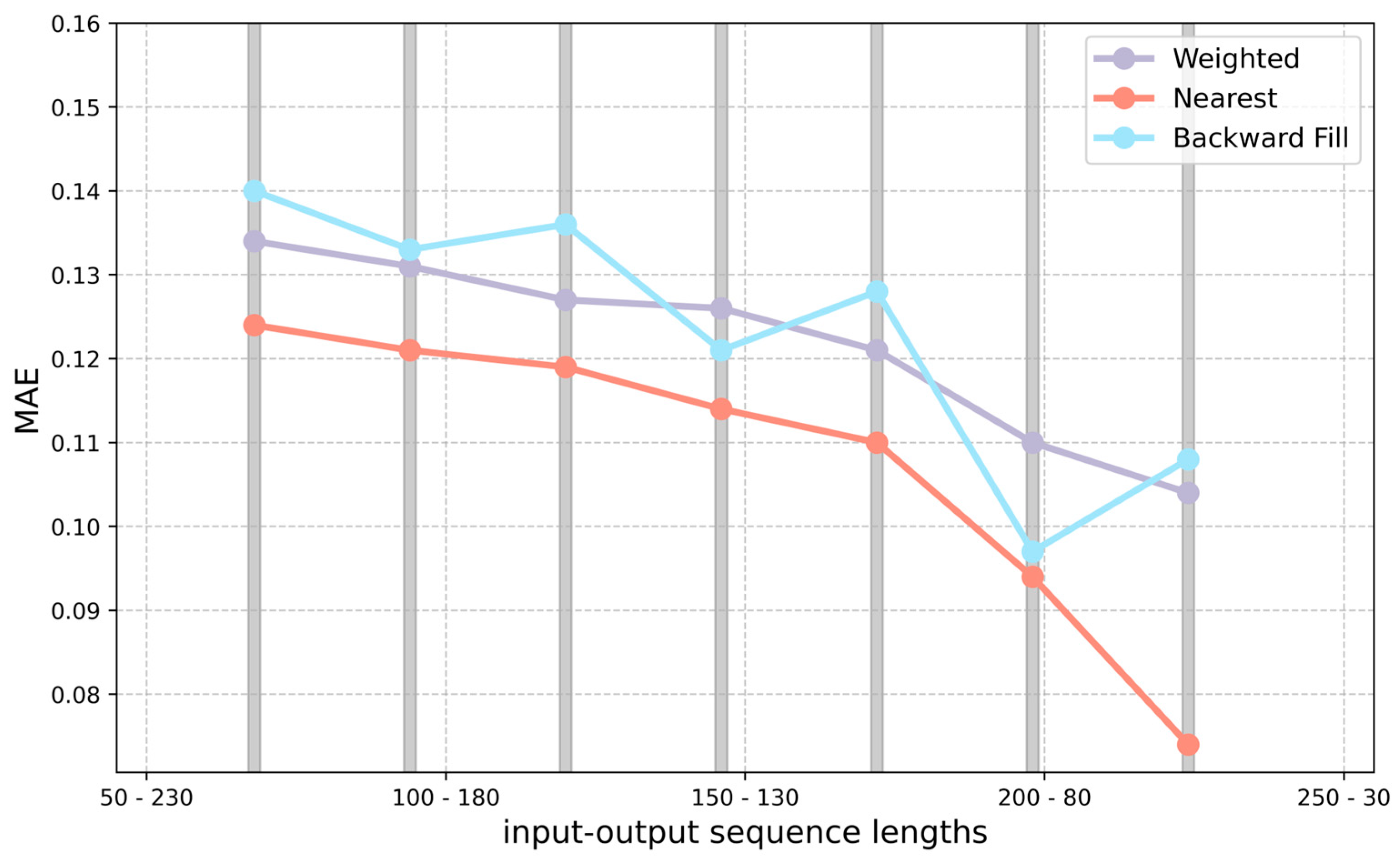

3.2. Evaluation of Model Selection Strategies for Non-Pre-Trained Lengths

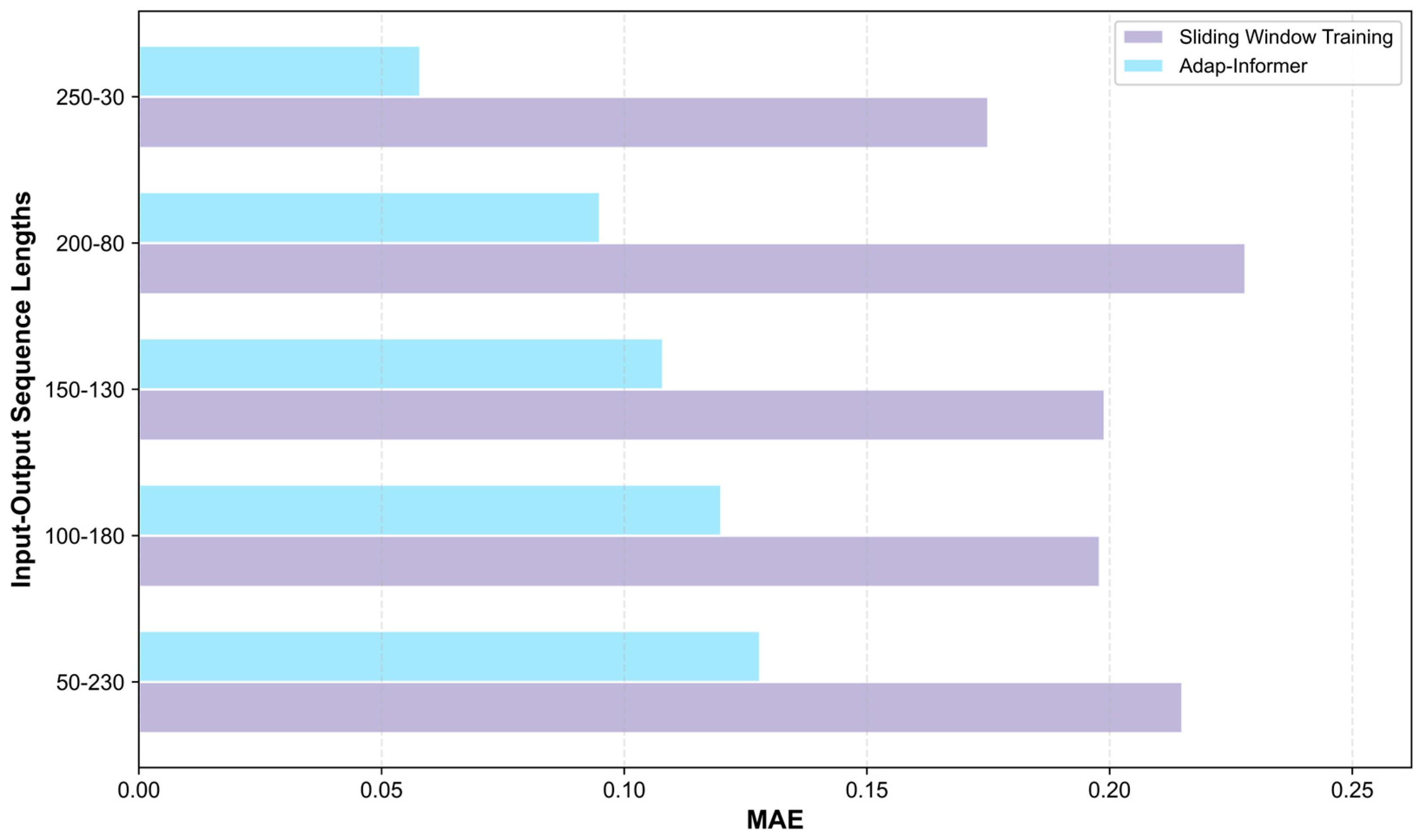

3.3. Comparative Evaluation of Model Training Strategies

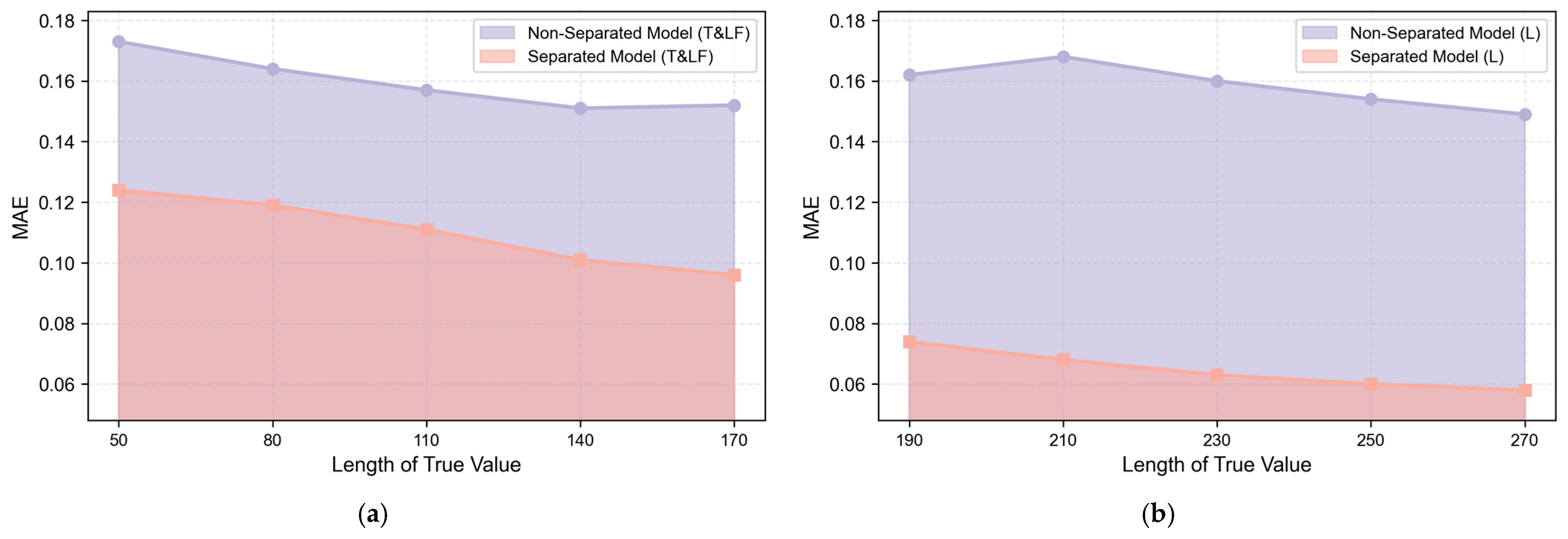

3.4. Comparative Experiment on Phased Modeling for Takeoff-Cruise and Landing Phases

3.5. Comparison Experiment

3.6. Practical Validation of Adap-Informer: Compliance, Fuel Optimization and Emergency Efficacy

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| δ | The standard deviation of the original data |

| Δfuelt | fuel consumption variation from initial value at time t |

| Δlatt | latitude variation from initial position at time t |

| Δlont | longitude variation from initial position at time t |

| fuel0 | initial fuel quantity |

| fuelt | fuel quantity at time t |

| lat0 | initial latitude |

| latt | latitude at time t |

| lon0 | initial longitude |

| lont | longitude at time t |

| MAE | mean absolute error |

| Μ | mean value of original data |

| N | sample size, dimensionless |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

| X | value in original data |

| Z | z-score standardized value, dimensionless |

| km | Kilometer |

| kg | Kilogram |

| hPa | Hectopascal |

| m/s | Meters per Second |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| ETOPS | Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards |

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organization |

| 0 | initial value |

| t | at time t |

References

- Seymour, K.; Held, M.; Georges, G.; Boulouchos, K. Fuel Estimation in Air Transportation: Modeling Global Fuel Consumption for Commercial Aviation. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 88, 102528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Ma, Q.; Qiu, T.; Gan, C.; Wang, X. An Engine-Level Safety Assessment Approach of Sustainable Aviation Fuel Based on a Multi-Fidelity Aerodynamic Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, S.; Rantanen, E.; Bogdanov, D.; Breyer, C. Global Transportation Demand Development with Impacts on the Energy Demand and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in a Climate-Constrained World. Energies 2019, 12, 3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Humpe, A.; Fichert, F.; Creutzig, F. COVID-19 and Pathways to Low-Carbon Air Transport Until 2050. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 034063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, S.; Melton, J.; Jiang, X.; Zilliac, G. Estimations of Aircraft and Airport Domestic Greenhouse Gas Emissions from 2016–2021. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2023 Forum, National Harbor, MD, USA, 12–16 June 2023; p. 4218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Comendador, V.F.; Arnaldo Valdés, R.M.; Lisker, B. A Holistic Approach to the Environmental Certification of Green Airports. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanto, J.; Liem, R.P. Aircraft Fuel Burn Performance Study: A Data-Enhanced Modeling Approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 65, 574–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau Codina, R.; Melgosa Farrés, M.; Vilardaga García-Cascón, S.; Prats Menéndez, X. A Fast and Flexible Aircraft Trajectory Predictor and Optimiser for ATM Research Applications. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference for Research in Air Transportation (ICRAT), Castelldefels, Spain, 26–29 June 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gardi, A.; Sabatini, R.; Ramasamy, S. Multi-Objective Optimisation of Aircraft Flight Trajectories in the ATM and Avionics Context. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2016, 83, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, J.W.; Liu, H. Deep Learning Based Short-Term Air Traffic Flow Prediction Considering Temporal–Spatial Correlation. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 105113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, L. Flight Time Prediction for Fuel Loading Decisions with a Deep Learning Approach. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 128, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metlek, S. A New Proposal for the Prediction of an Aircraft Engine Fuel Consumption: A Novel CNN-BiLSTM Deep Neural Network Model. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2023, 95, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, M.; Demirezen, M.U.; Inalhan, G. Physics Guided Deep Learning for Data-Driven Aircraft Fuel Consumption Modeling. Aerospace 2021, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, J.; Hou, Y. Spatial–Temporal Transformer Networks for Traffic Flow Forecasting Using a Pre-Trained Language Model. Sensors 2024, 24, 5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, W.A.; Ma, H.L.; Ouyang, X.; Mo, D.Y. Prediction of Aircraft Trajectory and the Associated Fuel Consumption Using Covariance Bidirectional Extreme Learning Machines. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 145, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Guo, D.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, E.Q.; Ge, W. Fuel Consumption Prediction for Pre-Departure Flights Using Attention-Based Multi-Modal Fusion. Inf. Fusion 2024, 101, 101983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, C.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, B. ETOPS Test Flight Study of Civil Aircraft Fuel System. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Symposium on Intelligent Unmanned Systems and Artificial Intelligence, Qingdao, China, 17–19 May 2024; pp. 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Claramunt Segura, J. FAA Regulation Analysis for ATR ETOPS Validation. Master’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, T.S.; Jensen, C.S.; Nielsen, T.D. Relational Fusion Networks: Graph Convolutional Networks for Road Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 23, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y. Aircraft Range Fuel Prediction Study Based on WPD with IAPO Optimized BiLSTM–KAN Model. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2025, 112, 108231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Hansen, M.; Ryerson, M.S. Evaluating Predictability Based on Gate-In Fuel Prediction and Cost-to-Carry Estimation. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 67, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Song, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Lin, T.; Deng, M.; Li, H. T-GCN: A Temporal Graph Convolutional Network for Traffic Prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 21, 3848–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, N.; Lachiri, Z. Multimodal Fusion Methods with Deep Neural Networks and Meta-Information for Aggression Detection in Surveillance. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 211, 118523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Yu, T.; Farahmand, H.; Mostafavi, A. A Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Predictive Flood Warning and Situation Awareness Using Channel Network Sensors Data. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2021, 36, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahadevan, D.; Ponnusamy, P.; Gopi, V.P.; Nelli, M.K. Prediction of Gate in Time of Scheduled Flights and Schedule Conformance Using Machine Learning-Based Algorithms. Int. J. Aviat. Aeronaut. Aerospace 2020, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryerson, M.S.; Hansen, M.; Bonn, J. Time to Burn: Flight Delay, Terminal Efficiency, and Fuel Consumption in the National Airspace System. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2014, 69, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W. Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 11106–11115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Fan, B.; Li, F.; Xu, X.; Sun, H.; Cao, W. Tcn-informer-based flight trajectory prediction for aircraft in the approach phase. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, J.; Larochelle, H.; Adams, R.P. Practical Bayesian Optimization of Machine Learning Algorithms. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25, 2951–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Xiang, X.; Wang, C. Towards Real-Time Path Planning Through Deep Reinforcement Learning for a UAV in Dynamic Environments. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2020, 98, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Bhardwaj, J.; Choy, S.; Kuleshov, Y. Applying Machine Learning for Threshold Selection in Drought Early Warning System. Climate 2022, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cao, J.; Philip, S.Y. Deep Learning for Spatio-Temporal Data Mining: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020, 34, 3681–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aircraft Category | Initial Fuel Range (kg) | Fuel Flow Rate (kg/h) | Cruising Fuel Consumption Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium-sized aircraft types | 16,000–41,000 | 2800–3300 | High (±5% variation) |

| large-sized aircraft types | 410,00–80,000 | 4600–5800 | Moderate (±8% variation) |

| Hyperparameter | Selection | |

|---|---|---|

| General | Loss Function | Mean Squared Error (MSE) |

| Dropout | 0.05 | |

| Optimizer | Adam | |

| Learning rate | 0.0002 | |

| Early Stopping Patience | 5 | |

| Batch size | 64 | |

| Number of epochs | 32 | |

| LSTM | LSTM Hidden Units | 256 |

| Number of LSTM Layers | 2 | |

| CNN- | Number of Attention Heads | 8 |

| LSTM- | CNN Kernel Size | 2 |

| Attention | Number of CNN Layers | 3 × 3 |

| Informer | Number of Attention Heads | 8 |

| Hidden Dimension | 256 | |

| Moving_avg | 25 | |

| Factor | 1 |

| Aircraft Category | The Length of the True Value | 5-275 | 55-225 | 105-175 | 155-125 | 205-75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | BiLSTM | 0.246 | 0.241 | 0.235 | 0.165 | 0.075 |

| ED-LSTM | 0.315 | 0.290 | 0.235 | 0.145 | 0.085 | |

| LSTM | 0.265 | 0.250 | 0.265 | 0.180 | 0.090 | |

| CNN-LSTM- Attention | 0.245 | 0.230 | 0.215 | 0.160 | 0.085 | |

| LSTM-CNN | 0.255 | 0.245 | 0.225 | 0.165 | 0.080 | |

| Adap-Informer | 0.123 | 0.119 | 0.104 | 0.087 | 0.052 | |

| RMSE | BiLSTM | 0.305 | 0.295 | 0.250 | 0.195 | 0.130 |

| ED-LSTM | 0.310 | 0.290 | 0.245 | 0.185 | 0.110 | |

| LSTM | 0.310 | 0.300 | 0.255 | 0.200 | 0.145 | |

| CNN-LSTM- Attention | 0.295 | 0.250 | 0.245 | 0.255 | 0.110 | |

| LSTM-CNN | 0.285 | 0.255 | 0.125 | 0.245 | 0.115 | |

| Adap-Informer | 0.140 | 0.133 | 0.115 | 0.100 | 0.065 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Fu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, L. Adap-Informer: Adaptive Aircraft Fuel Prediction Framework Supporting Emergency Decision-Making and Aviation Decarbonization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411078

Wu Y, Fu J, Li Y, Zhu Y, Huang X, Li L. Adap-Informer: Adaptive Aircraft Fuel Prediction Framework Supporting Emergency Decision-Making and Aviation Decarbonization. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411078

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yanxiong, Junqi Fu, Yu Li, Yongshuo Zhu, Xiaoru Huang, and Lu Li. 2025. "Adap-Informer: Adaptive Aircraft Fuel Prediction Framework Supporting Emergency Decision-Making and Aviation Decarbonization" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411078

APA StyleWu, Y., Fu, J., Li, Y., Zhu, Y., Huang, X., & Li, L. (2025). Adap-Informer: Adaptive Aircraft Fuel Prediction Framework Supporting Emergency Decision-Making and Aviation Decarbonization. Sustainability, 17(24), 11078. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411078