1. Introduction

Sustainable development aims to meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It represents a model that emphasizes the coordinated advancement of economic, social, and ecological environments. This serves as the foundation for improving social transformation initiatives. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) encompass various interconnected dimensions of sustainable development. These goals have evolved from calls for “Zero Hunger” to “Quality Education” [

1]. The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development explicitly prioritizes education in its fourth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 4). Education is recognized as a means to achieve the remaining goals [

2].Thus, education for sustainable development (ESD) serves as a core driver for realizing the SDGs. In ESD research, Devat S. Rathod emphasizes integrating critical sustainability issues into teaching. He also supports using participatory pedagogical approaches to inspire behavioral change and advance sustainable development actions among students. This approach fosters critical thinking, future scenario visualization, and collaborative decision-making skills at the same time [

3].

Fourteen guiding principles, specific learning outcomes, and priority areas for action are outlined in the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) report on the Recommendation on Education for Peace, Human Rights and Sustainable Development, which aims to comprehensively reshape all aspects of education systems, from laws and policies to curriculum development, teaching practices, learning environments and assessment. It is committed to achieving lasting peace, reaffirming human rights, and promoting sustainable development in the face of contemporary threats and challenges [

4]. At the same time, UNESCO Heritage Sites as Partners in ESD: Guidelines for Implementation emphasizes the promotion of ESD through the rich UNESCO heritage worldwide, including World Heritage Sites, Biosphere Reserves, Geoparks, and so on. Connecting learners with nature and increasing understanding of sustainability’s importance [

5].

Environmental education is a vital component of ESD, serving as a critical conservation strategy that aims to cultivate citizens’ conservation literacy and address environmental and resource sustainability challenges [

6]. Nicole M. Ardoin posits that effective environmental education transcends mere one-way information transfer; it generates direct environmental benefits and tangibly resolves conservation issues [

7]. The environment is an important asset for sustainable human existence, including plants, animals, weather and all the interconnected elements that together create the balance of life [

8]. By studying plant structures, observing plant growth, understanding plant reproduction and survival traits, and examining plant growth responses under varying environmental conditions, children gain profound insights into how environmental factors constrain and influence life. This hands-on experience proves more persuasive than theoretical explanations alone, providing rich and authentic material for environmental education. This paper uses plant growth cycle science education as a concrete entry point for environmental education. It explores new approaches to practical learning about plant growth cycles and seeks strategies to enhance the effectiveness of children’s environmental education.

Environmental education carries lifelong implications. According to Piaget’s four stages of cognitive development, children aged 6–12 enter the concrete operational stage. While they begin developing logical thinking and computational abilities, they still require concrete objects or imagery to aid in understanding concepts and enhance operational skills [

9]. Presenting plant growth cycles through intuitive methods aligns with this cognitive stage, making the knowledge easily accessible. This subject can also serve as a gateway to multidisciplinary learning, fostering children’s multiple intelligences and promoting holistic development. Nicole M. Ardoin suggests that in Early Childhood Environmental Education (ECEE) practice and outcomes, game-based, nature-rich teaching methods—which incorporate physical activity and social interaction—can more effectively aid children’s understanding of environmental concepts [

10]. Pennsylvania State University’s Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center disseminates conservation knowledge through innovative public programs. As a field research laboratory, Shaver’s Creek conducts cutting-edge research in visitor engagement with natural spaces, technology integration, and plant science. Engaging hands-on activities spark children’s enthusiasm for learning and foster positive habits. This establishes foundational environmental awareness, enhances social adaptability, and cultivates sound environmental literacy.

Mauro Cherubini notes that plant growth and reproduction constitute a progressive, unidirectional interactive process that cannot be retrospectively verified [

11]. Given the unique nature of the plant growth cycle, learning content. As tools for “education” and “learning,” teaching aids significantly enhance children’s comprehension during the learning process. They facilitate the development of sensory perception, motor coordination, and imagination [

12]. The organic integration of teaching aids with hands-on instruction creates interactive learning scenarios, effectively stimulating children’s learning autonomy and engagement. Traditional teaching aids for plant growth cycles primarily rely on models, images, and educational videos to observe growth processes, resulting in one-dimensional and intermittent learning experiences. Additionally, their usage scenarios are often fixed, failing to adapt to diverse teaching methods and environments while lacking interactivity. Against this backdrop, enhancing the interactivity and sustainability of Plant Growth Cycle Science Teaching Aid represents a critical challenge in this field.

In the field of Plant Growth Cycle Science Teaching Aid design, Scenario Theory offers significant guiding value. This theory upholds a “human-centered” core design objective, emphasizing the user perspective to deeply analyze common behavioral characteristics across different application scenarios, systematically collecting and precisely analyzing these traits. The limitation of fixed usage scenarios in traditional teaching aids can be addressed by identifying user needs through Scenario Theory’s multi-scenario behavioral analysis. Applying this theory opens new avenues for optimizing the design of the Plant Growth Cycle Science Teaching Aid, enabling creations that better align with actual user requirements and habits, thereby enhancing practicality and user experience.

The application of Scenario Theory inherently embodies sustainable development. When teaching aids adapt to multiple usage scenarios, they effectively reduce raw material consumption and carbon emissions during production. Resources are utilized efficiently by optimizing functionality and extending the product lifecycle, yielding long-term benefits. At the instructional content level, science education on plant growth cycles aligns closely with the core requirements of environmental education within sustainable development. Using the plant growth cycle as an entry point guides children from understanding individual plants to gradually expanding their knowledge toward comprehensive comprehension of entire ecosystems and natural sciences. This teaching approach, progressing from specific points to broader contexts, achieves sustainable development in both educational content and philosophy.

This study focuses on children aged 6–12, comprehensively mapping usage scenarios for the Plant Growth Cycle Science Teaching Aid. It analyzes overlapping behavioral patterns across different contexts to identify authentic user needs for these products. Based on this analysis, we propose teaching aid optimization strategies aligned with sustainable development principles. These strategies help children establish long-term, comprehensive learning plans and cultivate their environmental literacy. By enhancing the functionality and structure of teaching aids to accommodate diverse scenarios, we seek to improve modern educational equipment and advance the sustainable development of environmental education.

2. Research Methodology

This study adopts an innovative perspective on Scenario Theory to construct a multi-scenario conversion design methodology, applied to the practical design of plant growth cycle teaching aids. The design thinking approach for multi-scenario conversion primarily involves dissecting user behavior patterns across different usage scenarios, analyzing and summarizing them to identify genuine user needs. This informs subsequent product design optimization strategies. Applying this methodology ensures that teaching aids efficiently adapt to spatial constraints during scenario transitions, achieving dual objectives: seamless functional transitions and optimized spatial utilization. The KANO model serves as a tool for classifying and prioritizing user needs, focusing on analyzing variations in user satisfaction with product features or service attributes. Its core value lies in distinguishing between different levels of needs, enabling rational resource allocation to enhance product competitiveness and user satisfaction. Utilizing the KANO model during the user needs analysis phase to quantitatively validate user satisfaction significantly improves the effectiveness of user data. The combined application of multi-scenario conversion design thinking and the KANO model provides both theoretical foundations and data support for subsequent design practices.

2.1. Scenario Theory

Scenario theory is a design philosophy that understands and interprets user needs through user scenarios. It describes elements such as the user, their background information, their purpose or goal, and a series of activities and events they engage in [

13]. Donald Norman employed the term “scenario” in his book The Design of Everyday Things to explore the core of experience design by analyzing target users’ intrinsic thought processes and observable behavioral patterns within specific scenarios [

14]. Wu Ming argues that during transitions between usage scenarios, attention must be paid to users’ migration costs, aiming to reduce learning costs during the transition process. Simultaneously, it satisfies users’ demands for product effectiveness, usability, and convenience, fostering a strong connection with the product [

15]. In addressing specific design processes, Fu Longfei proposes an innovative approach centered on application scenarios and users: describing how users achieve goals through actions. This involves identifying the practice (when), location (where), user (who), and environmental context (what) that generates the goal, culminating in a specific action (action) [

16]. Thus, Scenario Theory optimizes product and interaction design within specific spatial environments based on users’ subjective experiences and needs, emphasizing a “human-centered” design philosophy.

2.2. Multi-Scenario Transition Design Thinking

The central element in a scenario is the user, who serves as both the starting point and the endpoint of scenario theory [

17]. Starting from the dimension of intrinsic relevance of scene transitions, this study refines user interaction behaviors within a single scene and extends it to explore the dynamic adaptability and coherence of user behavioral patterns across multi-scene transitions.

Multi-scenario design thinking aims to deepen user-centric design by analyzing behavioral patterns across diverse contexts, thereby optimizing product design principles. Transitioning between scenarios can be conceptualized as an ordered succession of intrinsically interconnected scenarios. This process embodies sequential cycles and sustainability across scenarios, collectively forming a cohesive multi-scenario transition framework. Across different application scenarios, users’ behavioral habits, preference tendencies, and psychological expectations undergo subtle yet complex shifts. These characteristics exhibit specific patterns and commonalities. Identifying key intersection points of user behavior based on these traits profoundly impacts product usability and satisfaction. Typically, user behavior guides the formulation of requirements. By analyzing and summarizing genuine user needs at these behavioral intersection points, optimization opportunities for the Product’s functional structure can be identified. Subsequent design implementation, user testing, and evaluation follow. If the User needs remain unmet, iterative design cycles continue until a satisfactory product is delivered. This article presents a flowchart for multi-scenario design thinking (

Figure 1), where “P” represents Product, “S” represents Scenario, “U” represents User, “B” represents User Behavior, and “D” represents User Demand.

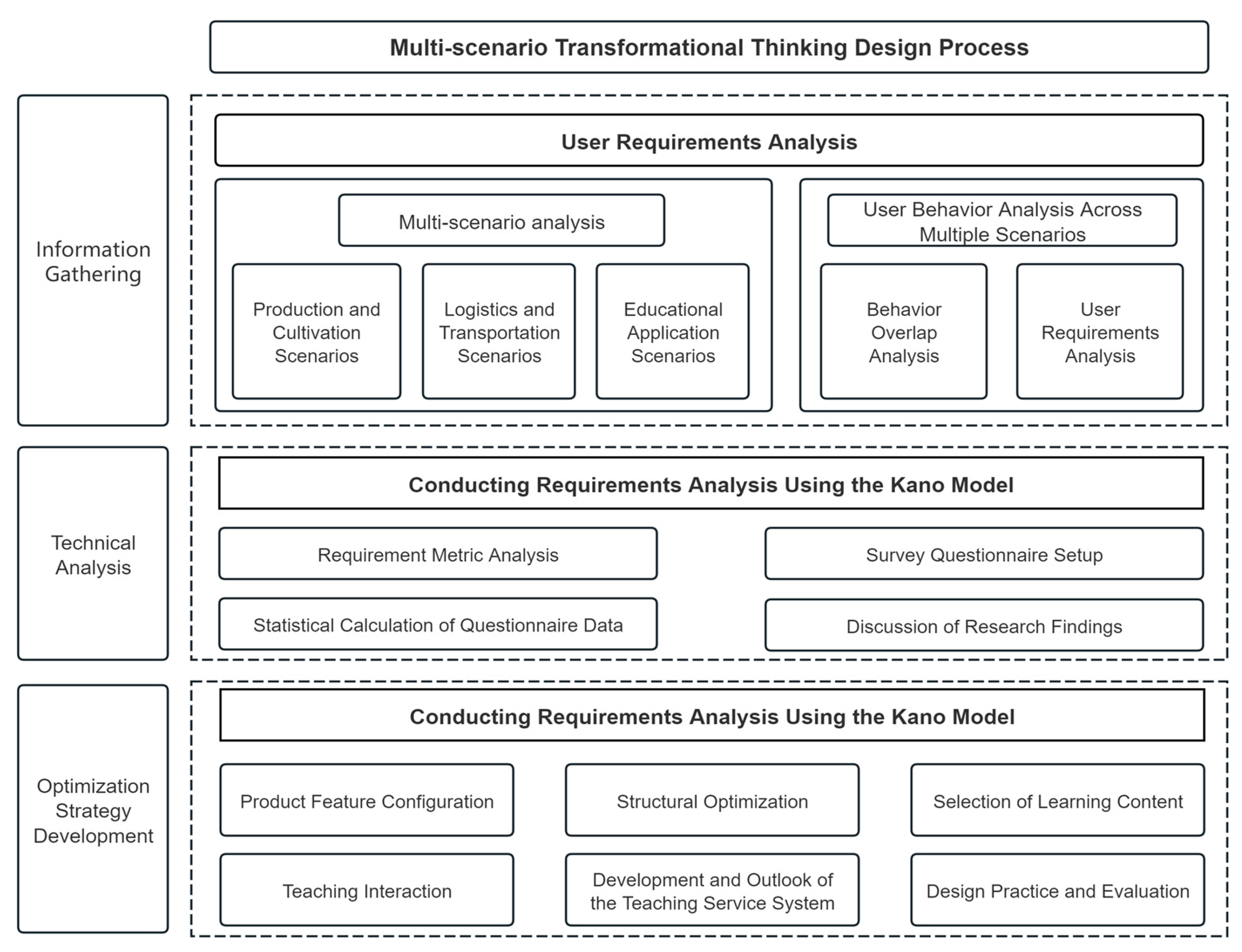

This study, grounded in multi-scenario design thinking, employs the Kano model for quantitative assessment during the user requirement consolidation phase. Organically integrating qualitative and quantitative design methodologies provides robust theoretical and data-driven support for optimizing the design of plant growth cycle teaching aids. The design process under multi-scenario transformation thinking can be divided into three phases: pre-information collection, mid-term technical analysis, and post-optimization strategy construction (

Figure 2). In the pre-information collection stage, first, sort out the teaching aids product multi-use scenarios, and collect and sort out multi-scene user behavior, identifying clear user behavior overlap points. In the mid-term technical analysis stage, the Kano model is used to calculate the weights of user requirements and to clarify their priorities in the product design process. Finally, based on the calculation results, we summarize and develop an optimization strategy for the plant growth cycle science teaching aids.

In designing the Plant Growth Cycle Science Teaching Aid, refining the multi-scenario transition approach holds significant implications for the sustainable development of product functionality and usage contexts. Integrating resources across different scenarios and enabling their sharing achieves optimal efficiency. For instance, establishing an energy loop in toy usage, after-sales processes, and subsequent plant handling allows children to experience ecological cycles, fostering comprehensive environmental awareness intuitively. Simultaneously, adopting modular design and universal technical standards in product esthetics and technology application reduces redundant production, lowers environmental costs, and promotes efficient resource utilization, thereby advancing educational toys’ green and sustainable development.

2.2.1. Multi-Use Scenario Analysis

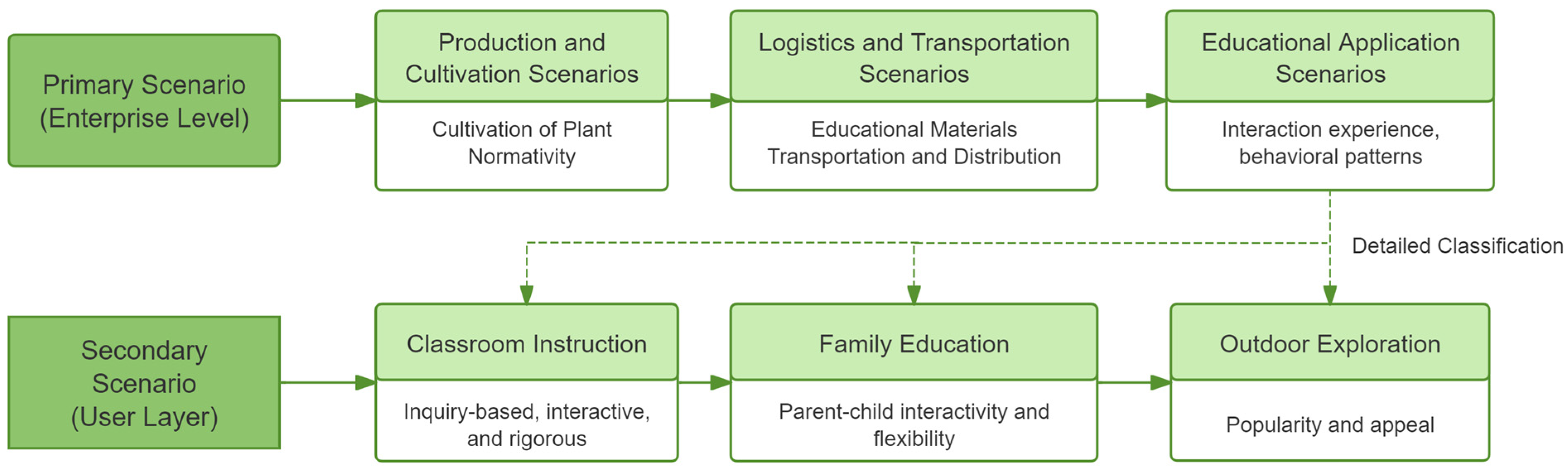

To align with the sustainable development concept of Plant Growth Cycle Science Teaching aids, this paper analyses teaching aid usage scenarios and categorizes them into two levels: primary and secondary flow lines. This classification system provides a theoretical basis for subsequent exploration of specific user behavioral manifestations (

Figure 3).

Primary flowlines focus on the macro-process from product inception to initial application, encompassing three core scenario transitions: base production and cultivation, logistics and transportation, and final deployment in educational settings.

Secondary flowlines delve into specific usage contexts after the teaching aids enter the market, emphasizing how the product flexibly adapts across diverse scenarios—including classroom instruction, home education, and outdoor exploration—to meet the demands of different learning environments and methodologies. For specialized teaching aids like plant growth cycle kits, optimizing the secondary flow is particularly crucial. It demands that the teaching aids possess scientific accuracy and educational value and exhibit high adaptability and portability. This ensures that they effectively disseminate knowledge and stimulate learning interest across diverse settings. Below is a detailed production, transportation, and learning scenarios analysis.

2.2.2. Sorting out User Behavior in Multiple Usage Scenarios

Based on the above analysis of the plant growth cycle science teaching aids, this study examines and records user behavior in the major scenes through field observation and then analyses the results. This study examines and records user behaviors in the three primary scenarios through field observation, and analyses and discusses them graphically.

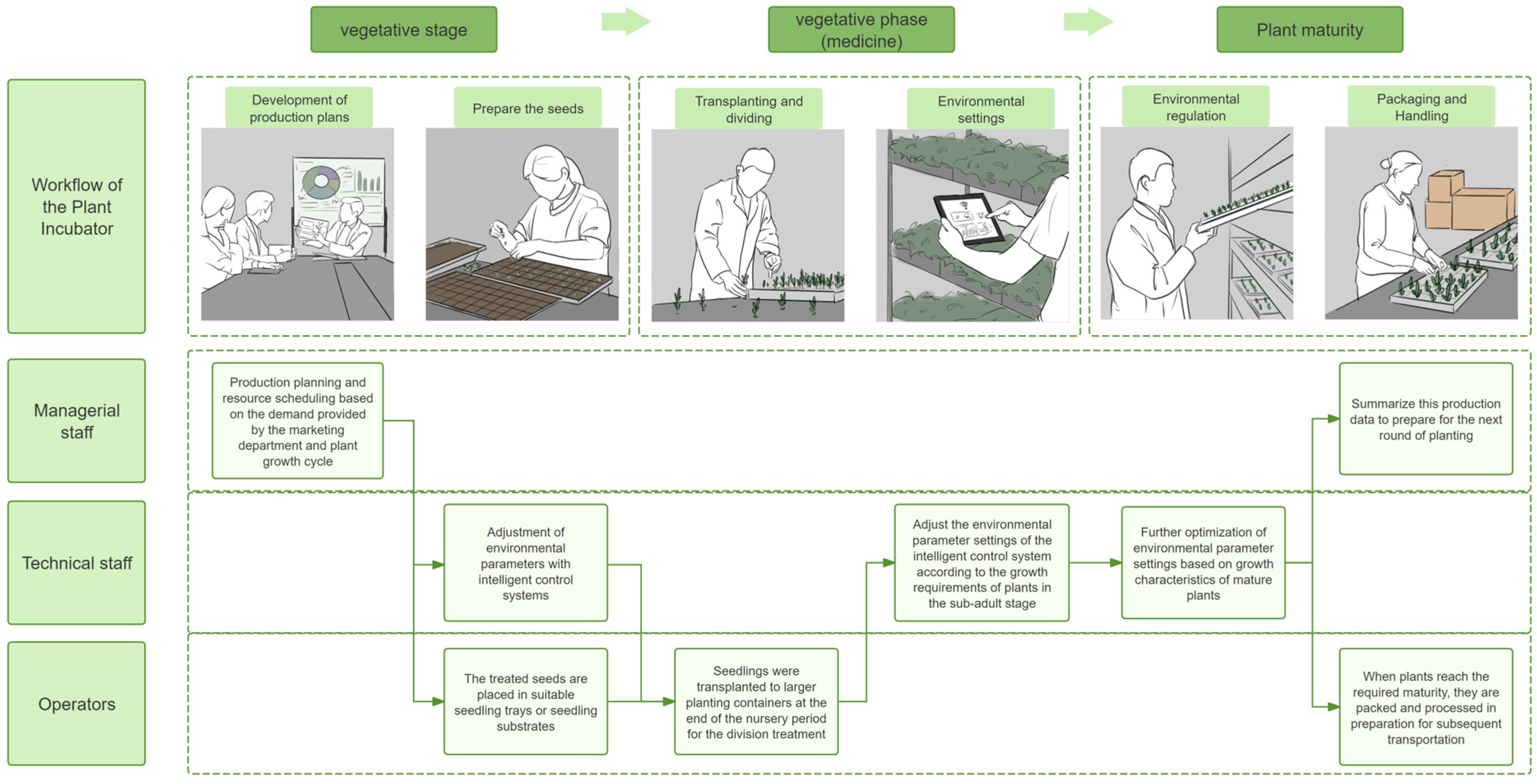

First, the production and cultivation scene: this paper takes Wuhan Future Home Intelligent Plant Cultivation Base as an example for on-site research (

Figure 4). The base is built on the core concept of intelligentized and informationized management, which vividly demonstrates the innovative possibilities and prospects in plant cultivation.

The plant growth cycle can be divided into seedling, sub-adult and mature stages. This research uses this time frame to define the workflow and operational flow of the intelligent plant cultivation base. In each growth stage, the core of the base is to provide the best environment for plants. In terms of workflow, the users of the plant cultivation base can be divided into three categories: managers coordinate the planning and formulate planting plans; technicians operate and maintain the cultivation system to accurately control and optimize the environment; operators are the frontline production executives who undertake daily cultivation work such as sowing, transplanting, packaging, and so on, and although some of the work is reduced with the enhancement of automation, some parts still require manual intervention. The interaction between the staff and the product mainly includes controlling environmental parameters, system operation, plant division, planting, handling, packaging, and equipment maintenance and repair (

Figure 5).

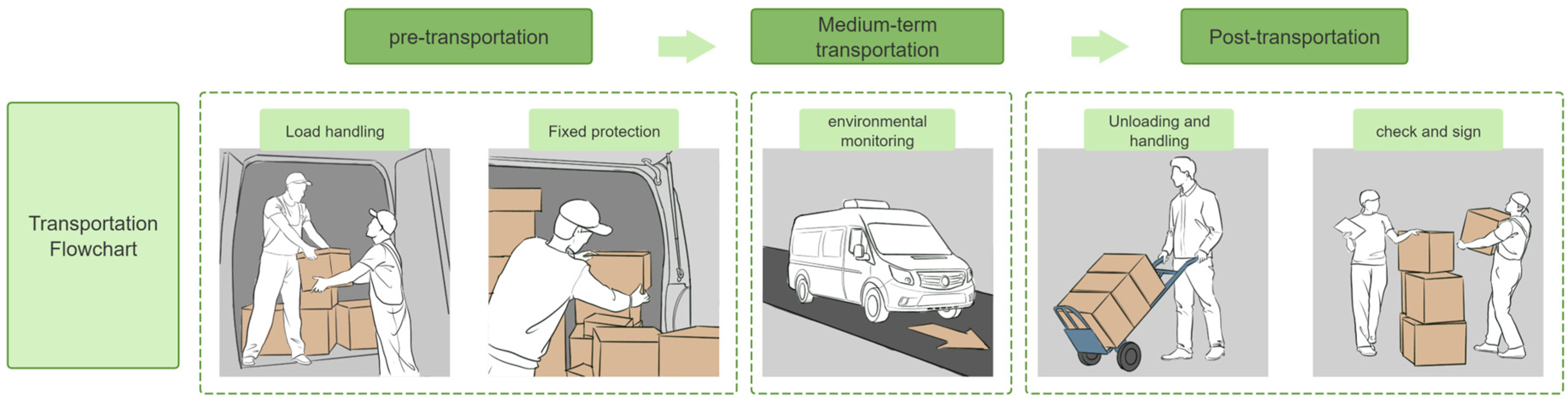

The second scenario is logistics and transportation. In the process of converting teaching aids from the production and cultivation scenario to the learning and application scenario, the transportation scenario not only connects the two ends of production and consumption but also influences the status and quality of the products that finally reach learners. In this transportation scenario (

Figure 6), the core task of the transportation operator is to load and unload goods, transport them, and monitor the journey. According to the above analysis, the interactions between the transportation operator and the product are mainly as follows: loading and handling, fixing and protecting, environmental monitoring, unloading and handling, and delivery and signing.

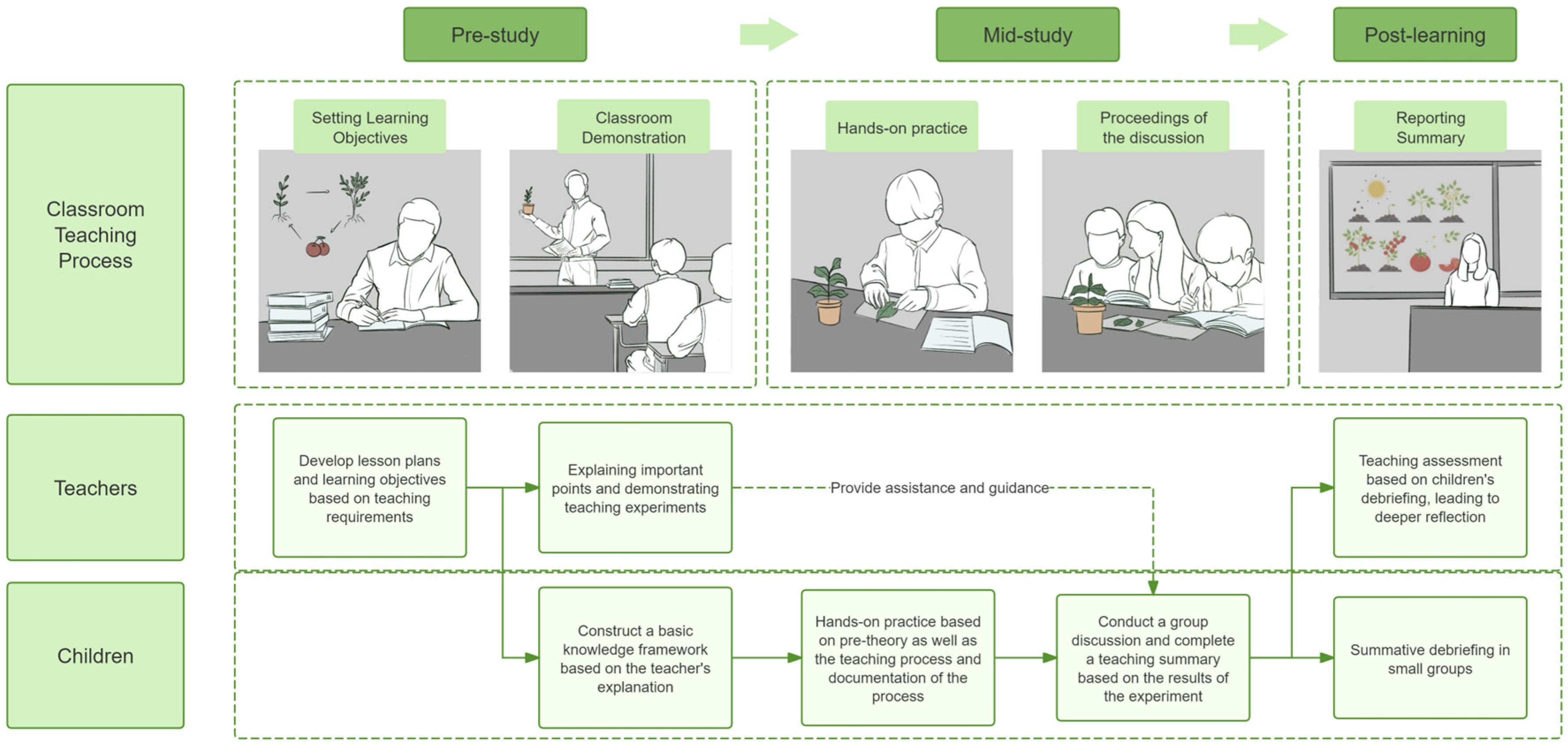

The last is the learning application scenario. The learning scenarios of teaching aids can be divided into entirely open-ended scenarios and semi-open-ended scenarios. Semi-open-ended scenarios primarily involve classroom and family teaching, in which teachers or parents lead learning activities through lectures or experiments. The full-open scenario is characterized by treating children as the main body of learning, encouraging them to engage in independent, exploratory learning, primarily through outdoor exploration. The learning process in teaching application scenarios shows some commonality, mainly reflected in three phases: setting goals in the early stage, practicing and discussing in the middle stage, and reporting and summarizing in the late stage (

Figure 7). In this process, children’s main interactive behaviors include daily plant maintenance, careful observation and recording of growth conditions, active participation in hands-on activities, and discussion and sharing with peers.

In the in-depth study of the use of plant growth cycle science teaching aids, this study meticulously analyses the behaviors of different user groups during operation, interaction, and observation. By summarizing and organizing these rich behavioral data (

Figure 8), the characteristics of user behavior are clearly presented, providing a realistic foundation for the subsequent analysis of the overlapping points of user behavior.

2.2.3. User Behavior Overlap Points in Multi-Scenario Adaptation

User behavior can be summarized into three aspects: cognition, action, and sensation, all of which manifest during the operation process. Actions are conscious movements, and all actions constitute behavior [

18]. By constructing user behavior scenarios, we meticulously analyzed the sequential cycles and sustainable relationships among various scenarios in the plant growth cycle teaching aids.

At the primary scenario level, the guiding objective of user behavior centers on standardizing teaching aids and ensuring their effective distribution to learning environments. During this phase, scientific management systems and technical measures guarantee the stability and controllability of plant growth conditions. Standardization of the growth process represents a key advantage of regulated cultivation. By establishing and implementing unified cultivation procedures and quality standards, consistency is ensured across each batch of plants during their development. This minimizes disruptions to teaching caused by individual differences, enabling students to more accurately grasp universal patterns when observing, recording, and analyzing plant growth. Consequently, learning precision and effectiveness are enhanced. Through this integrated approach, the primary scenario not only establishes a foundation for subsequent educational activities but also demonstrates the unique strengths of school–enterprise collaboration. It constructs an efficient, practical teaching service system that deepens children’s understanding of plant growth cycles, potentially pioneering new pathways at the intersection of educational innovation and technological application.

In the secondary scenario, the focus shifts toward creatively integrating standardized teaching aids into curriculum design. With these tools as support, children’s learning outcomes and engagement significantly improve. Here, users—particularly educators—design activities based on content, age-specific characteristics, and cognitive levels, skillfully weaving teaching aids into every lesson phase to achieve precise alignment between tools and educational objectives. User behavior in the secondary scenario not only demonstrates deep exploration of teaching aids’ functionalities but also reflects educators’ profound understanding and respect for children’s learning patterns.

The connecting point between user behaviors across these two scenario levels lies in the core medium of “teaching aids.” The standardization and distribution of teaching aids in the primary scenario provide the material foundation and prerequisites for curriculum design in the secondary scenario. Conversely, the innovative application of teaching aids in the secondary scenario directly tests and provides feedback on the work done in the primary scenario. These two levels complement each other, jointly driving educational practice’s continuous optimization and advancement. Furthermore, users’ behavioral choices across different scenarios are influenced by multiple factors, including personal experience, educational philosophy, and technological proficiency. These elements form a complex and nuanced interplay between scenario transitions and user behavior.

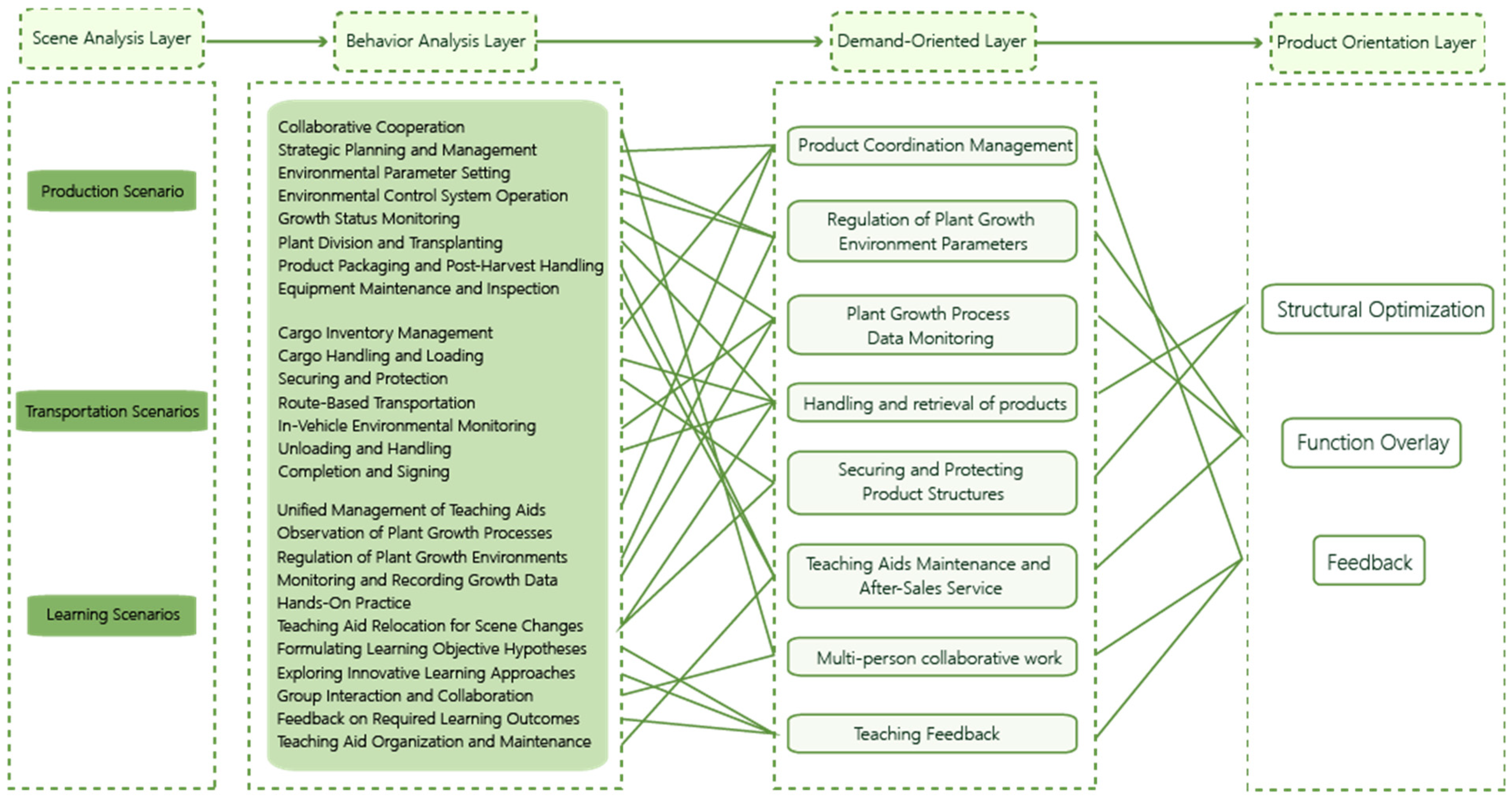

Based on an in-depth analysis of the intrinsic connections between scenario transitions and user behavior, this section further focuses on extracting key elements of critical user actions. By meticulously deconstructing users’ operational habits, interaction patterns, and cognitive responses across different scenarios, we identify commonalities in user behavior—the behavioral overlap points. These convergence points reflect users’ fundamental needs and expectations across contexts and provide insights and direction for subsequent product design and optimization. The hierarchical classification of behavioral overlap points during multi-scenario transitions follows a progressive logic, divided into four layers: Scenario Analysis Layer, Behavior Analysis Layer, Demand-Oriented Layer, and Product-Oriented Layer (

Figure 9).

This study systematically extracted and summarized user behavioral elements through in-depth exploration of specific scenario analysis levels across three typical scenarios. It revealed that high-frequency user behaviors primarily focus on eight core domains: product management, environmental control, plant growth monitoring, handling and retrieval, collaborative interaction, and information feedback. Furthermore, through in-depth analysis of these key behaviors, this study finds they closely correspond to three dimensions: product structure optimization, product function integration, and product information feedback. Therefore, in the design practice of teaching aids, efforts should focus on implementing targeted optimization strategies across these three dimensions to enhance the overall effectiveness and user satisfaction of teaching aid products.

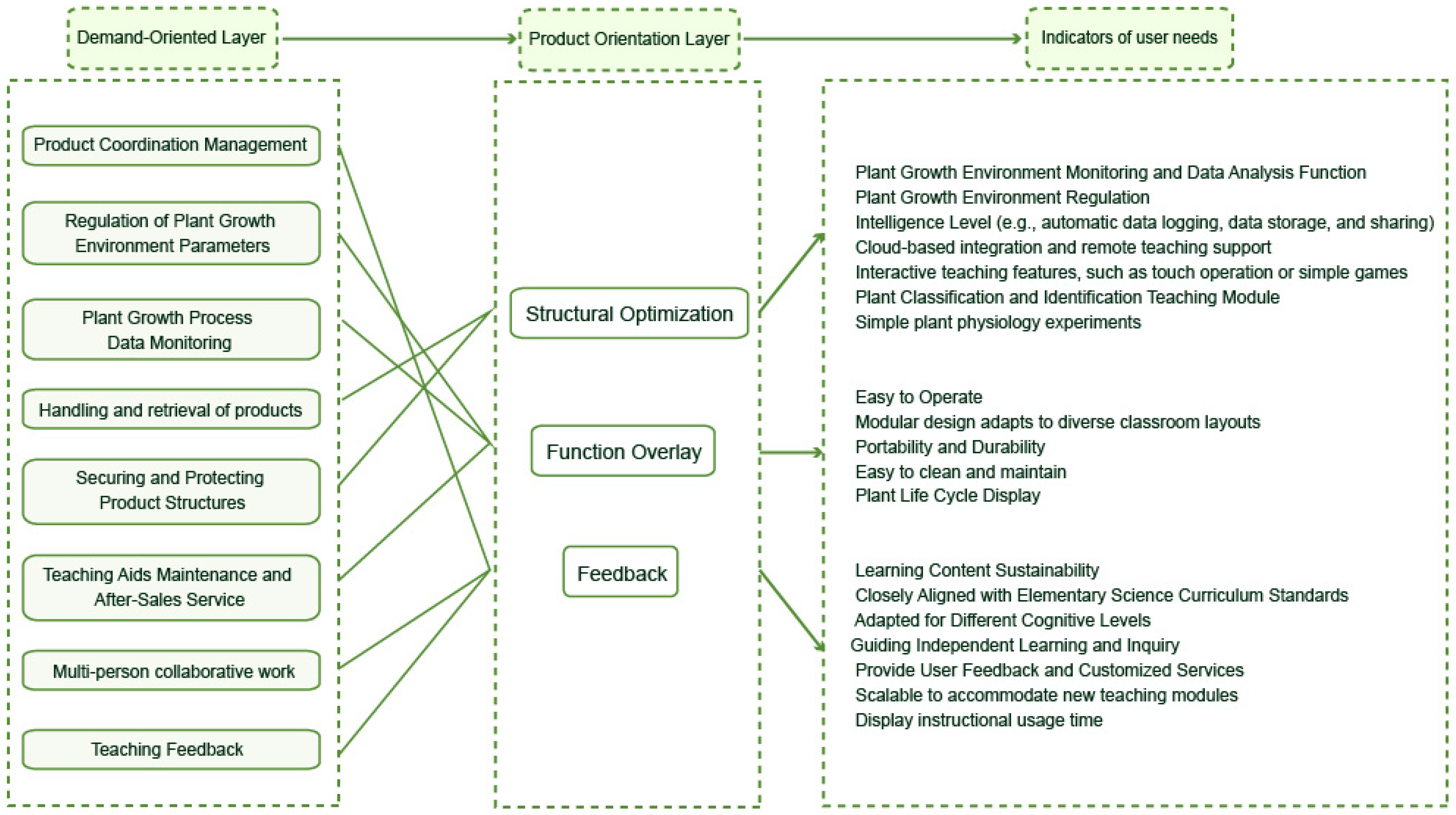

Demand is the first element for users to use the product. User demand comes from the purpose users want to achieve when using the product. User demand is the most fundamental basis for design [

19]. The user demand index is a quantitative or qualitative definition of demand that clarifies its content, scope, degree, and other elements, providing precise standards for its realization and management. Combined with the above analysis of the hierarchy of user behavior under multi-scenario transformation, this study organizes these general demand points into more precise demand indicators (

Figure 10), which facilitates the subsequent identification of user demand in the Kano model calculation.

2.3. KANO Model Analysis of Design Requirements for Plant Growth Cycle Teaching Aids

The KANO model is a tool invented by Noriaki Kano, a professor at Tokyo Institute of Technology, to categorize and prioritize user needs, inspired by Herzberg’s two-factor theory. The Kano model is based on user needs and focuses on changes in respondent satisfaction through forward and backward questions (i.e., the presence versus absence of a need). At its core, it specifies a non-linear relationship between product performance and user satisfaction [

20]. Aint Thin Zar Kyaw used the Kano model to construct an identification framework for user requirements for library research data management services (RDMS), which was used to prioritize RDMS requirements from a multi-stakeholder perspective [

21]. Andre Albuquerque, in his study of consumer satisfaction, used the Kano model to identify user needs in a library. In his study on consumer satisfaction, Andre Albuquerque combines the Kano model with fuzzy systems theory to examine the subjectivity inherent in assessing service quality and further identifies the characteristics of consumer needs that can help an organization make strategic decisions [

22]. Meanwhile, Keyvanfar developed the adaptive behavior satisfaction index based on the Kano model, a framework for assessing user satisfaction arising from cooling adaptive behaviors in green buildings [

23]. Liu proposed the S-Kano model to construct a framework for modeling customer needs in mobile gaming [

24]. Since its inception, the KANO model has helped several industries understand users’ needs at different levels and accurately identify the key factors of user satisfaction.

Applying the Kano model to identify users’ needs for plant growth cycle science teaching aids and organizing these needs through quantitative data analysis can provide solid data support for the subsequent design strategy of teaching aid products. This study prioritized and numbered the demand indicators to facilitate accurate positioning and quick retrieval in the subsequent design of the Likert-type satisfaction scale questionnaire. Meanwhile, to build a hierarchical analysis framework, this study summarized and classified the demand indicators into three levels: product function superposition, product structure optimization, and product information feedback (

Table 1).

2.3.1. Questionnaire Setting

Based on the hierarchical structure of user needs indicators, this study further developed a Kano model assessment tool tailored to the cognitive level of children aged 6–12 years. In designing the functional stem and response scales, positive (presence of function) and negative (absence of function) scenarios were constructed for each demand item, and children’s familiar daily language and figurative expressions were used. For example, in the product structure optimization level, for the need of “modular structure, adapting to the layout of multiple teaching environments”, the positive stem is designed as “the small parts of this plant teaching aid can be easily disassembled and reassembled, so that it can be played with at home or at school, do you think you like it?”, and the negative stem is “if the small parts of the teaching aid can’t be disassembled, so that it can only be used in the school, how do you feel about it?”. The functional overlay and feedback dimensions were similarly designed. This questionnaire design, with situational descriptions, is consistent with children’s figurative thinking and reduces cognitive load. The instrument system provides the basis for quantitative assessment of child-friendly types for subsequent Kano attribute analysis. Detailed questionnaires are available in the

Supplementary Material (Table S1).

This study conducted a comprehensive multi-city data collection effort, primarily utilizing WeChat as the online platform for data gathering. Questionnaire distribution was mainly carried out through community groups, official accounts, and Moments sharing. The distribution period ran from 20 November 2023 to 3 December 2023, spanning two weeks. A total of 136 questionnaires were distributed, yielding 134 valid responses. Detailed demographic information is presented in the table below (

Table 2). As shown, the majority of respondents completed the questionnaire primarily through social group channels, with ages predominantly concentrated in the 6–12 age range.

Considering the special age group of the respondents in this survey, the purpose, scope, and use of data collection will be clearly explained to parents and children. After obtaining their explicit consent, they will be asked, in multiple-choice format, whether they will participate. If they do not want to do so, the questionnaire will be terminated. Encrypted storage and restricted privileges are used to protect privacy. At the same time, a parent confirmation link is set up on the first page of the questionnaire, inviting the parent to accompany the child in completing the questionnaire, to ensure the child’s participation is genuine and effective.

2.3.2. Statistical Methods

The survey results were categorized using the KANO model’s two-dimensional attribute classification evaluation table (

Table 3) to classify user experience requirements into five categories: Minimum Requirements (M), Expected Requirements (O), Attractive Requirements (A), Indifferent Requirements (I), and Reverse Requirements (R) [

25].

In this model, A represents a need that, when met, causes users to feel exceptionally satisfied and surprised; M indicates a fundamental need that must be satisfied; R signifies a need that users do not require and may even find objectionable; I indicates a need toward which users exhibit indifference; and Q indicates a conflict between two responses.

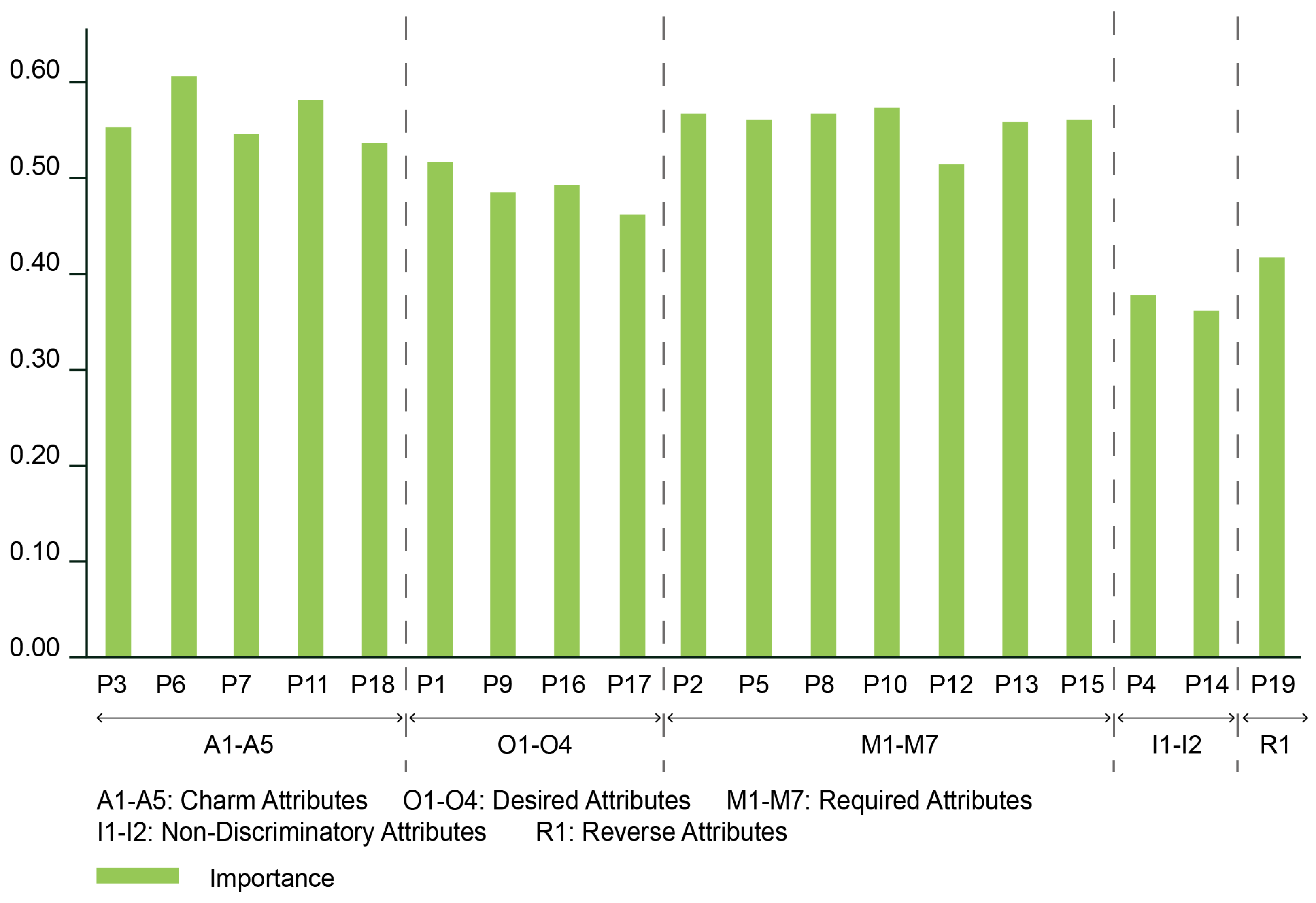

When categorizing user experience requirements, the values of user requirements A, O, M, I, R, and Q are primarily categorized by the attributes with the largest share, based on the counts of users’ responses to positive and negative questions. The demand attributes for “plant growth environment monitoring and data analysis”, for example, are A = 13.43%, O = 50.75%, M = 7.46%, I = 21.64%. Taking the demand attribute of “plant growth environment monitoring and data analysis” as an example, it is found that A = 13.43%, O = 50.75%, M = 7.46%, I = 21.64%, because the coefficient value of O is the largest, so this demand attribute is a necessary attribute of O. The same calculation steps are used to calculate the remaining 18 functional demand attributes. The calculation result is shown in

Figure 11.

Based on the above data, this study organizes the findings according to demand attributes. It presents them in a visual format to highlight which demands have the most significant impact on user satisfaction (

Figure 12). Essential attributes represent fundamental functionalities that must be present in the product, as they are indispensable to users. Examples include plant growth environment regulation (attribute value: 55.97%), interactive teaching functionality (attribute value: 55.22%), intuitive operation (attribute value: 55.97%), portability and durability (attribute value: 56.72%), display of plant life cycles (attribute value: 50.75%), sustainable learning content (attribute value: 55.22%), and adaptability to varying cognitive levels (attribute value: 55.22%). The absence of these features directly leads to user dissatisfaction and may even cause users to abandon the product. From the charts, the differences in the data among the demand indicators for essential attributes are relatively small. In subsequent optimization designs, these requirements can be incorporated as the basic functional design for teaching aids.

Charm attributes are those features that deliver surprise and added value to users, such as plant classification and identification teaching modules (attribute value: 59.7%), simple plant physiology experiments (attribute value: 53.73%), ease of cleaning and maintenance (attribute value: 57.46%), and scalability for adding new teaching modules (attribute value: 52.99%). While these features significantly enhance user satisfaction, their absence does not cause significant dissatisfaction. Among these, the teaching module for plant classification and identification has garnered significant attention and will be prioritized in subsequent optimization strategies.

The Better–Worse coefficient metric determines the importance of a requirement based on users’ relative satisfaction (B) and relative dissatisfaction (W).

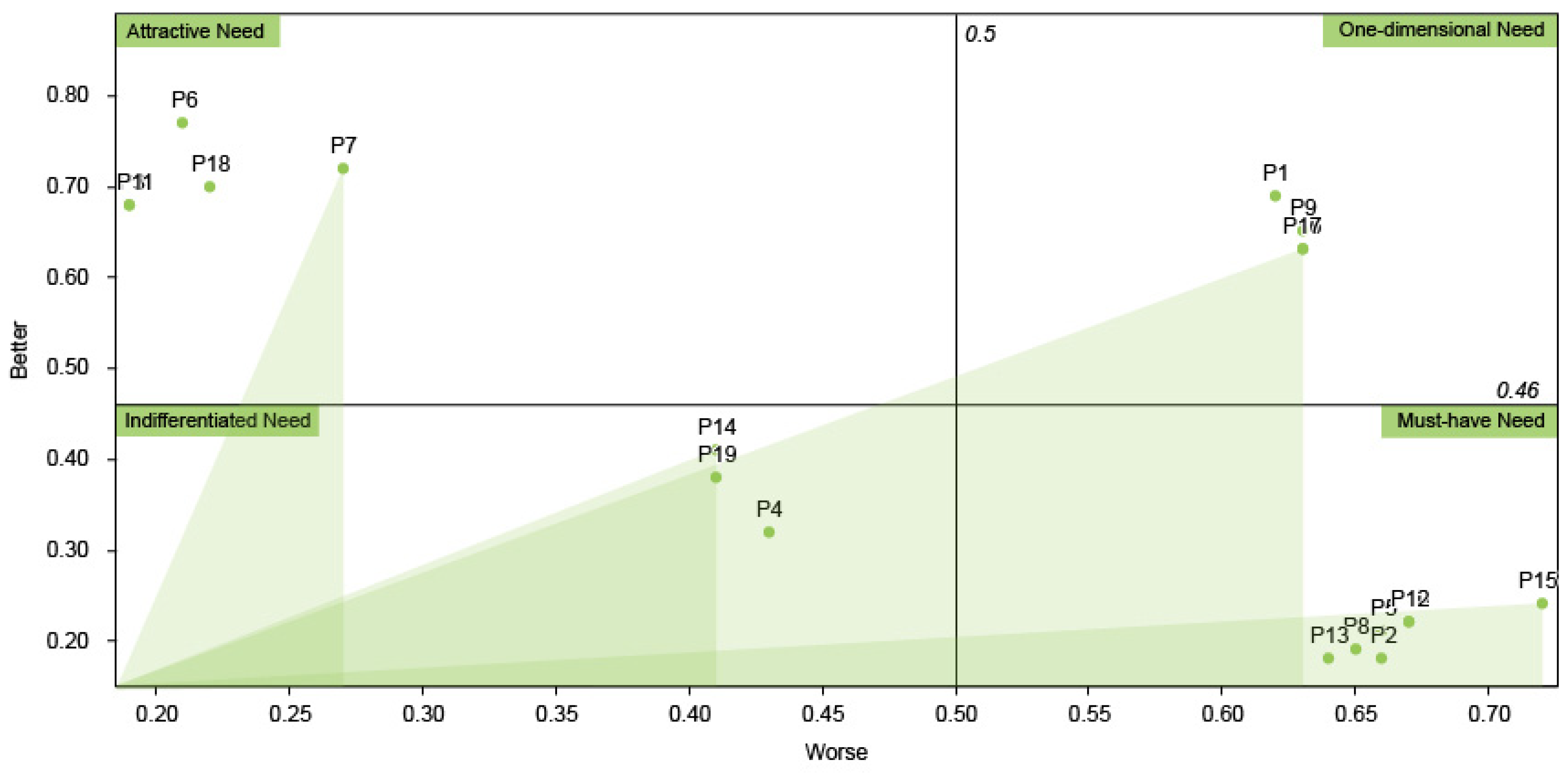

Based on the Better–Worse coefficient analysis method, the calculated coefficients for each requirement were plotted in a sensitivity matrix with satisfaction coefficients on the horizontal axis and dissatisfaction coefficients on the vertical axis. Based on the statistical results in the table, a satisfaction matrix for the 19 demand indicators was plotted, with the satisfaction coefficient on the X-axis and the dissatisfaction coefficient on the Y-axis (all data normalized to absolute values). The centerline of the X-axis represents the average satisfaction coefficient, while the centerline of the Y-axis represents the average dissatisfaction coefficient (

Table 4). This configuration highlights the varying weights of each data point [

26].

The calculation formula for the Better–Worse indicator is as follows.

The enhanced satisfaction coefficient B (Better): (Charm Attributes + Desired Attributes)/(Charm Attributes + Desired Attributes + Essential Attributes + Indifference Factors), as shown in Equation (1):

Worse Coefficient W (Worse): (Desired Attributes + Essential Attributes)/(Delightful Attributes + Desired Attributes + Essential Attributes + Indifference Factors) × (−1), see Equation (2):

2.3.3. Calculated Results

Analysis based on the KANO model reveals significant variations in the impact of different features and services on user satisfaction (

Figure 13). Among these, delight attributes such as intelligent functionality, plant classification and identification teaching modules, simple plant physiology experiments, ease of cleaning and maintenance, and scalability exhibit higher “Better” values. This indicates that enhancing these features can substantially boost user satisfaction. Such features often deliver additional value or pleasant surprises to users, serving as key differentiators in competitive product offerings.

In contrast, essential attributes such as plant growth environment control, intuitive operation, portability and durability, sustainable learning content, and plant lifecycle display—though scoring high on the “Worse” scale—show relatively lower “Better” values. This indicates that while these features form the product’s foundation, users exhibit lower sensitivity to their addition or reduction. While their absence would cause extreme dissatisfaction, even exceptional execution rarely becomes a decisive factor in user selection.

Desired attributes—such as plant growth environment monitoring and data analysis, modular structure, guidance for independent learning and exploration, and provision of user feedback and customized services—exhibit notably high “Better” and “Worse” values. This indicates that refining these features directly impacts overall user satisfaction. Therefore, product development must prioritize its implementation and optimization.

Indifferent attributes like cloud synchronization and remote teaching support exhibit relatively low “Better” and “Worse” values, indicating minimal impact on user satisfaction. Under resource constraints, allocating more resources to other critical features may be justified.

Reverse attributes, such as displaying teaching usage time, exhibit higher “Worse” values, suggesting this feature may provoke user dissatisfaction. Product design should strive to avoid or carefully handle such features to prevent adverse impacts on user experience.

3. Discussion

Based on the in-depth analysis of user behavior overlapping across different scenarios, combined with the KANO model classification of user demand attributes and Better–Worse coefficient analysis, to meet user demand for Plant Growth Cycle Science Teaching Aid, incorporating real plants into classroom settings can create an immersive, highly interactive natural plant learning experience for children. Leveraging innovative technology can precisely optimize plants’ basic survival needs, transforming elusive growth processes into quantifiable data for intuitive observation and comparison. Furthermore, the ease of operation, portability, and durability of the teaching aids are key areas requiring optimization in product structure and material selection. The sustainability of educational content and its adaptability to varying cognitive levels are crucial elements for cultivating users’ environmental literacy. This study will discuss specific optimization strategies covering functional configuration, structural optimization, learning content selection, teaching interaction, and the construction and outlook of the teaching system.

3.1. Product Function Configuration

In configuring the functional specifications of teaching aids, consideration must be given to the fundamental requirements of plant growth, the convenience of instructional demonstrations, and sustainable development principles. The design should comprehensively incorporate features such as light regulation, temperature control, water supply, and nutrient supplementation. The IoT-based intelligent monitoring system enables real-time tracking of plant growth and guides optimal cultivation practices [

27]. Muhammad Shoaib Farooq highlighted the key role of the Internet of Things (IoT) in smart agriculture, enabling secure, hassle-free connectivity for farmers and field monitoring to facilitate simple, cost-effective interactions [

28]. Xueyan Zhang developed an IoT-based system for real-time monitoring of soil moisture and nutrients in citrus orchards in Chongqing’s reservoir area and investigated the integration of a fertilization and Irrigation Decision Support System (IDSS) for precise fertilization and irrigation management [

29]. By deploying high-precision sensors for light intensity, temperature, humidity, soil moisture, and nutrient levels, it continuously monitors and quantifies key factors affecting plant development. This ensures plants maintain healthy growth after transitioning to educational settings, minimizing resource waste caused by environmental mismatches. Computer vision technology supports automated prevention and monitoring in plant cultivation [

30]. Visually reflecting changes in plant morphology helps educators and students promptly assess growth conditions, avoiding over-intervention or under-maintenance to achieve precise resource utilization.

Specifically, teaching aids should integrate innovative control systems and feature simple, intuitive function buttons, enabling children to easily master the operation and avoid cognitive barriers posed by complex processes. This helps cultivate children’s environmental awareness and resource management skills from an early age.

As a rapid means of production, it requires 75% less area than traditional farming methods. Nisha Sharma, in her study on hydroponics applied to vegetable production, noted that the Nutrient Film Technique has been successfully scaled up globally for the production of leafy and other vegetables, with water savings of 70–90% [

31]. The development of this type of technology has, to some extent, provided an empirical basis for the technological citation of plant growth cycle science teaching aids. Hydroponics meets the production and educational needs of plant cultivation bases by providing stable nutrient solutions that promote rapid plant growth with visible root systems. Compared to soil cultivation, it conserves water, reduces fertilizer and pesticide use, and is environmentally friendly. This method enhances growth efficiency while simplifying the maintenance of teaching equipment, offering an eco-friendly, practical case study for education.

3.2. Structural Optimization

As learning spaces expand beyond traditional classrooms to include outdoor, online, and blended settings, teaching aids must transcend single-purpose functionality. They require high portability and durability to ensure long-term resource utilization across diverse environments.

In the structural optimization of teaching aid products, modular design methods are key to adapting to the spatial dimensions of different scenarios and promoting sustainable use. Modular design refers to dividing a product into a set of modules (each module consisting of a set of components) that are interdependent within a cluster and independent between clusters [

32]. The modular structure not only improves product performance but also makes assembly and disassembly easier. To a certain extent, it reduces the product’s environmental impact and improves its service life and recyclability. It aligns with the principle of sustainable product design [

33]. At the same time, modular product design can support mass customization, reduce development costs, and make work in loosely coupled organizations more efficient [

34].

Taking classroom environments as an example, compact and portable dimensions are essential to facilitate movement and storage across different settings, minimizing resource idleness during transitions. Therefore, design should prioritize optimizing transport structures—such as incorporating detachable or foldable components—to ensure efficient circulation of teaching aids throughout production, cultivation, transportation, and instructional processes. This reduces logistics costs and energy consumption, extends service life, prevents premature replacement due to damage, and minimizes resource consumption at the source.

Color, as a vital component of product esthetics, inherently evokes diverse psychological responses through its visual expression. Therefore, the product’s exterior employs a green palette harmonizing with plants’ natural hues [

35]. This not only symbolizes life and vitality but also visually fosters a learning environment that feels close to nature. This approach enhances educational appeal while aligning with sustainable ecological principles.

3.3. Learning Content Selection

To maximize teaching effectiveness, plant selection and cultivation prioritize vegetables and fruits closely tied to daily life, such as fast-growing sprouts and wheatgrass. These have short growth cycles, typically showing noticeable changes within 7–14 days, allowing children to intuitively grasp the mysteries of plant life within a brief timeframe. Simultaneously, the plant cultivation base can provide specimens at various growth stages based on instructional needs, ensuring timely access to teaching materials for each activity. Given the unidirectional nature of plant growth, implementing standardized cultivation protocols is crucial. One of the most important factors in environmental control is light management techniques [

36]. Precise control of environmental factors—such as maintaining temperatures between 20 and 25 °C (68–77 °F) and light intensity at 1000–2000 lux (100–200 lux)—effectively reduces growth uncertainties, minimizes resource wastage from abnormal development, and enhances teaching efficiency, ensuring every resource contributes to plant cultivation and education. Moreover, maintaining light intensity at 1000–2000 lux can minimize growth uncertainties. This reduces resource wastage caused by abnormal growth, enhances teaching efficiency, and maximizes the value of every resource in plant cultivation and education. Such practices propel plant science education toward sustainability.

3.4. Interactive Teaching

The priority techniques for environmental education are outdoor activities, environmental games, and special projects [

37]. In terms of teaching tool interaction, fully leverage their functional characteristics while integrating sustainable development concepts. Encourage students to participate in the plant growth management process through hands-on activities. Noble Po-Kan Lo, in his research on collaborative approaches to education and the promotion of student self-directed learning, proposed the GEARS framework, comprising five main aspects: goals, enablers, activators, recognition, and solutions. The application of the GEARS framework provides a theoretical basis for optimizing instructional interactions in the context of designing instruction on the plant growth cycle [

38].

Regarding the objectives, children’s ecological literacy can be fostered on an ongoing basis through hands-on plant cultivation. For example, children can adjust light intensity and watering frequency in real time to simulate the effects of different environments on plant growth, thereby enhancing the practicality and fun of learning.

About push factors, the main ones include parents, teachers and relevant networking data. Teachers can motivate and enhance children’s motivation through verbal praise and non-physical reinforcement (e.g., smiles, pleasant expressions, and praise) [

39]. Networked data can serve as a knowledge base, providing students with rich learning resources and reference examples. Online hands-on communication communities can also catalyze children’s learning. Children can share their experiences, exchange ideas and broaden their learning horizons in the community groups.

A series of challenging projects or tasks can be designed to activate learning. Project-based learning increases children’s understanding of concepts and enhances students’ sense of belonging and academic success [

40]. Science learning tasks for plant growth cycles need to be staged and iterative to ensure a complete cognitive loop. At the same time, a series of contemporary technologies (sensors, computer vision, hydroponics) is provided to children as technical support for plant growth cycle science learning during problem-solving or task-based activities. When faced with a real problem, children are encouraged to apply what they have learned to find a solution and enhance their practical and creative skills.

About recognition, there has been an expansion from traditional performance indicators to assessments that focus on the whole learning process. Assessment is essential to support children’s learning and development [

41]. Reflection is at the heart of the program, guiding children to reflect from multiple perspectives to identify strengths and weaknesses. Based on the assessment and reflection results, a “think and fix” session is designed to optimize the learning process and establish a virtuous cycle of assessment—reflection—“think and fix”.

About solutions, the physical artifacts and evidence of inquiry related to the plant growth cycle created by the children document the results of efficient resource use, which both recognize the children’s learning process and build valuable experience for subsequent learning.

3.5. Teaching Service System Development and Outlook

Equipment classification coding management is a fundamental prerequisite for improving equipment management standards and leveraging information systems [

42]. The application of this management approach has dramatically improved the accuracy and completeness of equipment data, as well as the level of information management of equipment at the equipment management efficiency level [

43]. In the construction and implementation stages of equipment classification and coding management, adequate resources, a supportive administrative system and continuous teacher development are required. Adequate resources are the material basis for integrating emerging technologies, such as the introduction of advanced intelligent coding equipment and the establishment of an efficient information management platform. They cannot be separated from financial and material support. A supportive administrative system, on the other hand, can formulate reasonable policies and streamline the approval process, creating a favorable environment for the application of technology. Ongoing teacher development is also crucial, and training to enable teachers to master new technologies can better promote their application in management.

At the same time, the issues of equity and access to resources should not be overlooked. In the process of building a pedagogical service system, there may be inequities in access to new technologies and equipment across regions and schools due to resource differences. Equity in education depends fundamentally on the development of good external system conditions: geographic, demographic, political and socio-economic [

44]. Some resource-poor areas may not be able to implement advanced management systems promptly, leading to inefficient management. To address the need to increase investment in resource-poor areas, policies are designed to ensure fairness, and a resource-sharing platform is established to facilitate resource flows and broaden access for all parties.

In addition to focusing on the key points of system construction, exploring the application of the teaching service system can also innovate the model of popular science learning. With VR, AR and cloud-supported technologies, an online virtual space can be built for plant growth cycle science learning, expanding learning beyond the physical suite. Virtual Reality (VR) has gained increasing attention as an educational tool that makes the learning process more interesting, thus increasing student motivation and attention through virtual simulation [

45,

46]. Meike Paat addresses the limitations of current AR educational tools in teaching “Gedi” plant cultivation, thereby enhancing the educational effectiveness of “Gedi” plant cultivation instruction [

47]. Yu-Cheng C employs AR-based learning materials to provide a comprehensive view of the studied plants, thereby enriching children’s learning experience in natural science courses [

48]. Rack-woo Kim developed a virtual reality (VR) simulator for educational greenhouses, bridging the spatial gap between learners and educators [

49]. These cases collectively demonstrate the promising applications of virtual technologies in plant cultivation and instruction.

In plant growth cycle science education, this technology enables students to observe plant growth conditions in different environments online. This not only dramatically reduces the use of physical materials but also effectively reduces material throughput, avoids waste, and reinforces sustainability from a material utilization perspective. At the same time, the online mode extends the life cycle of the teaching aids, further deepening the sustainability of the plant growth cycle science teaching aids.

3.6. Design Practice and Evaluation

This study applied optimization strategies to the design of physical models and comprehensively evaluated the resulting teaching aids across three dimensions: technical structure comparison, educational effectiveness, and environmental friendliness. Technically, it compared the optimized aids with traditional teaching aids in terms of technology and structure. Regarding educational effectiveness, testers conducted usability tests on the physical models and assessed children’s learning outcomes after use. To assess environmental friendliness, the Life Cycle Assessment method was employed to comprehensively evaluate environmental impacts across all stages, from production to recycling. Supported by actual data, the findings confirm that the optimized teaching aid product demonstrates sustainability and environmental friendliness.

3.6.1. Practical Design of Educational Tools for Explaining Plant Growth Cycles

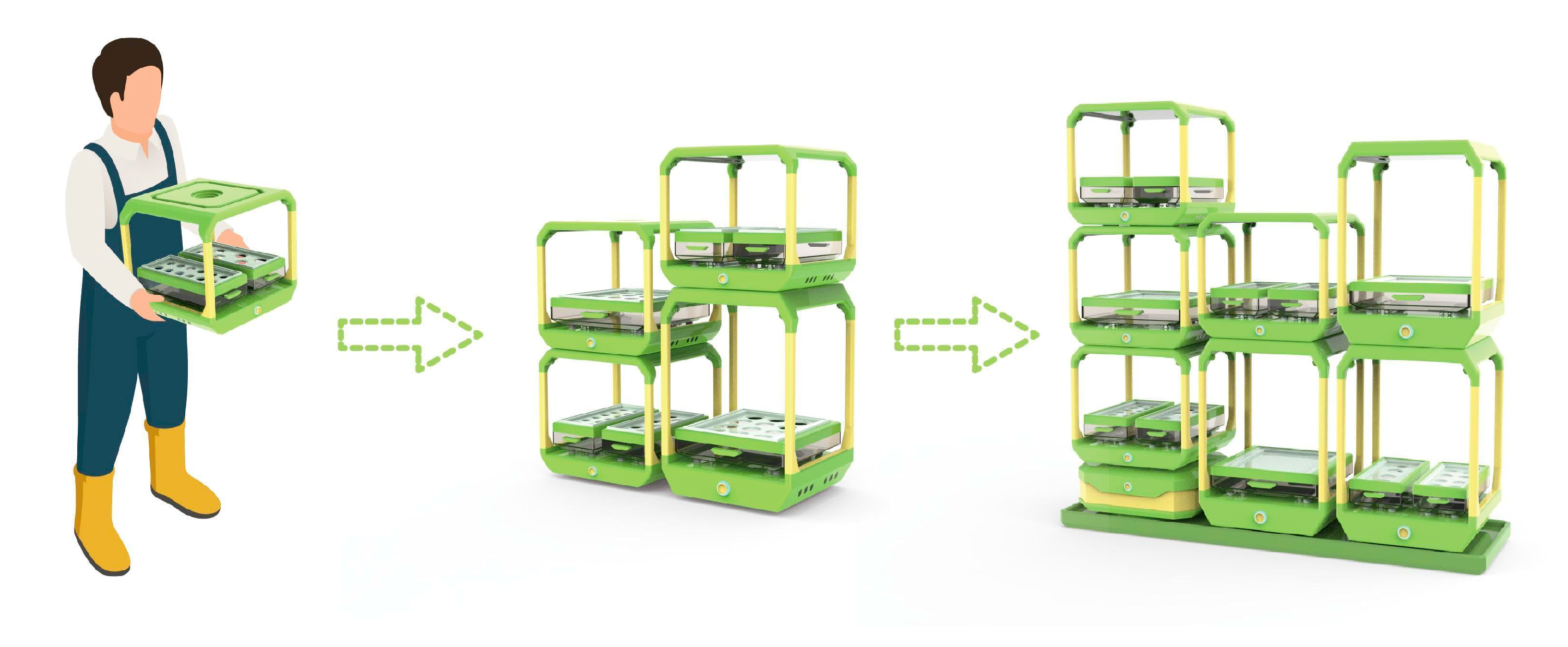

Based on the above design strategy, this study has designed an original model of plant growth cycle science teaching aid, “Growing up” through Rino 7 and 3D printing technology, and the primary purpose of this Growing up plant growth cycle teaching aid (

Figure 14) is to take plant growth cycle observation as the entry point for sustainable education. This growing-up plant growth cycle teaching aid is primarily based on observing the plant growth cycle as the entry point for sustainable education. Through practical activities such as plant observation, planting, and maintenance, as well as the explanation of theoretical knowledge, it guides children to experience plant growth and change and cultivates their observation and hands-on skills. Real plant growth processes are introduced into the teaching scene.

In the functional design of the high-precision sensor collection, each independent module is equipped with a fully self-contained circulation system to ensure the efficiency and stability of the plant cultivation process. At the same time, the central control button enables children to control the light, water, and temperature sensors during use. The specific technical references and selection reasons are listed in the table below (

Table 5).

Structural design, geometric shape as the main design tone, realizes the product in the horizontal (horizontal) and vertical (vertical) two dimensions, with flexible arrangement and expansion ability (

Figure 15). The optimization of observability is considered. The observation space is maximized to allow users to intuitively monitor plant growth.

Material selection for plant growth cycle educational tools must meet safety standards and quality requirements while balancing functionality and durability. The outer shell is preferably made of recyclable ABS plastic, which offers dimensional stability, high hardness and toughness, and resistance to impact and abrasion, ensuring long-term safe use. Connecting components utilize sturdy aluminum alloy to enhance structural stability and durability. For the core plant cultivation section, rockwool is selected as the growing medium. It provides excellent water retention, aeration, and antimicrobial properties, while its lightweight texture creates an optimal root environment.

3.6.2. Product Technical Structure Assessment

In evaluating the technical structure of teaching aids, this study identified comparable products as a control group. During the control product selection process, the following keywords were specified: Intelligent, plant growth models, children’s botany, etc. After excluding newly launched items and products with no sales records, each potential product was ranked by sales volume and positive review rate. Ultimately, two plant growth cycle products with complete sales histories (

https://www.amazon.com, accessed 29 November 2025) were selected as technical control cases to ensure representativeness and data comparability. The symbol “√” indicates the product possesses this feature, while “×” indicates the product lacks this feature (

Table 6).

Through the detailed comparison of the technical features across the three products in the table above, it becomes clear that the innovative irrigation system and light adjustment function are essential core features for achieving intelligent plant growth cycle teaching aids. Both precisely meet the critical needs for water and light at different stages of plant growth. In terms of meeting fundamental plant growth requirements, “Growing up” stands out. Its temperature control system precisely regulates environmental heat, intelligent sensors comprehensively monitor environmental parameters, and image recognition technology enables real-time tracking of plant growth status. Multi-sensor monitoring technology establishes a rigorous data surveillance network, feeding information to the connected platform for real-time user access. However, “Growing Up” exhibits technical gaps in water-level monitoring and in intelligent early warning capabilities. Future research will focus on addressing these shortcomings through innovative solutions, thereby enhancing the product’s intelligence and user experience.

3.6.3. Teaching Effectiveness Evaluation

In the teaching evaluation of the plant growth cycle science education kit, the assessment primarily involves testing the physical model and consists of two parts. First, the SUS model is used to measure satisfaction with the “Growing Up” plant growth cycle teaching aid design, verifying its usability, operability, and interactivity, revealing shortcomings, and indicating optimization paths. Second, the learning growth rate of children before and after using the teaching aid is compared to evaluate its learning effectiveness.

The SUS model (System Usability Scale) is a standardized questionnaire developed by John Brooke in 1986. It consists of 10 five-point scale items designed to quantitatively assess the usability of a system or product, with scores ranging from 0 to 100. The scale items are structured with five positive and five negative statements, with odd-numbered items positive and even-numbered negative, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of product usability (

Table 7). The test was conducted with four school-aged children, four experts in children’s education, and two parents (

Table 8). The children completed the online questionnaire with their parents, with explicit and informed notification prior to completing the form. Based on feedback scores, the process will determine the usability of the teaching aids and propose directions for improvement, iteratively improving the design system.

Based on meticulous calculations of recycled questionnaire scores, the “Growing Up” teaching aid achieved a usability score of 80.25. According to the SUS scoring system, this score corresponds to an A− grade, highlighting its excellent product experience (

Table 9). Among the items receiving high ratings were: “T3: I believe this plant growth cycle teaching aid is easy to use,” “T7: I believe most people would quickly learn to use this plant growth cycle teaching aid,” and “T1: I believe I would be willing to use this plant growth cycle teaching aid frequently.” These items primarily address the teaching aid’s ease of use, quick learning curve, and future use frequency, all of which received positive user feedback.

Based on questionnaire responses, this study conducted brief interviews with users. To enhance rigor, interview questions were designed as a pair of positive and negative statements. Taking “T3” as an example, the positive question was: “During the teaching aid trial, which features (e.g., interface layout, operational workflow, physical buttons) best met your learning/teaching needs?” while the reverse question was: “During the teaching aid trial, what areas do you think could be improved?” Detailed interview content is provided in the

Supplementary Material (Table S2).

Based on user interview findings, this study has organized optimization suggestions and mapped them to specific product features (

Table 10). During trials of the “Growing Up” physical model, users expressed high satisfaction with data collection, modular functional zoning, and multi-scenario educational applications. However, continuous refinement is needed for growth pattern configuration, voice-guidance functionality, and data set presentation methods. Furthermore, given ongoing advances in scientific research, teaching materials must be updated promptly to align with the latest discoveries and pedagogical approaches, preventing information obsolescence.

To assess the learning outcomes of the teaching aids, plant growth-related knowledge was assessed in the four participating children before the physical model test. The assessment covered 10 plant growth-related knowledge points, focusing on logical reasoning about the plant growth process, identification of basic concepts, and the principles of photosynthesis. The assessment was scored on a scale of 30 points, with 24 points or more classified as “A”, 18–23 points as “A−“, and less than 18 points as “B”. The assessment questionnaire was distributed in two copies before and after the trial of the teaching aids, and the scores were standardized at the end of the test. The results for four children are shown below (

Table 11).

Based on the test results, the children’s average score on the assessment was 20.75 before the trial of the teaching aids, which was in the A grade. After the trial, the average score was 27, upgraded to the A grade, with an overall improvement of 30.85%. However, the assessment was stratified by age: children aged 6–9 years showed a significant improvement, while those aged 11–12 years needed to deepen their knowledge, which could be expanded to include an in-depth understanding of photosynthesis.

Questionnaires, interviews, and tests were used to assess the usability and learning effectiveness of the teaching aids. The data showed that the plant growth cycle teaching aid optimization strategy was effective in helping children learn about plant growth. However, optimization is needed in the areas of growth pattern setting, voice guidance, and data set presentation. The optimized teaching aid product has better usability and interactivity. In addition, the sample size of this study is small, and more rigorous control group experiments will be conducted in the future to further explore the teaching effectiveness of educators’ use of the teaching aid products in order to improve the design and application of the teaching aids.

3.6.4. Environmentally Friendly Assessment

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a technique used to analyze the environmental impacts of products throughout their life cycles, from raw material extraction to disposal or recycling [

50]. It is the most objective and commonly used tool for quantifying environmental impacts. This study uses LCA to demonstrate the environmental performance of Growing up across the product’s life cycle, compared with existing innovative growers on the market. The functional unit is defined as “all the functions required to provide and maintain a total of 50 standard growing cycles (e.g., from sowing to harvesting lettuce) over a 6-year service period.” This definition of the functional unit takes into account the optimization of the product’s more extended service life and potentially more efficient use, rather than simply comparing “a product” with “a product”. Fairness is ensured to some extent. A “cradle-to-grave” system boundary has been established, encompassing five stages: raw material acquisition, manufacturing, transportation, use, and recycling.

For the impact assessment methodology, the CML baseline methodology was selected using SimaPro 9.5. The methodology is comprehensive and widely recognized. We will focus on the following core environmental impact indicators: global warming potential, non-renewable resource depletion, human toxicity (non-carcinogenic), acidification effects, eutrophication, and freshwater ecotoxicity. The life cycle inventory was developed using the Ecoinvent built-in database as a background data source to make reasonable assumptions about product configurations, as shown in the table below (

Table 12).

Using detailed evaluation data from SimaPro 9.5 to optimize the product’s life cycle, this sustainable teaching aid design demonstrates excellent environmental benefits (

Table 13), with improvements ranging from 15.5% to 31.7%. The optimized solution achieved significant reductions in core metrics, including global warming potential, resource consumption, and toxicity impacts, compared to existing products on the market.

The analysis shows that despite a slight increase in total mass and a doubling of the service life of the optimized product, its complete lifecycle carbon footprint (128.3 kg CO2 equivalent) is reduced by 22.5% compared to the baseline product (165.5 kg). This improvement is mainly due to the adoption of 70% recycled ABS plastic, which also resulted in a 31.7% reduction in non-renewable resource consumption. In terms of ecological and health impacts, the optimized product’s human toxicity and freshwater ecotoxicity have been reduced by 29.8% and 27.0%, respectively, thanks to the recycled-material production process and a higher recycling rate, which reduces hazardous emissions at the source. Although the total electricity consumption of the optimized product (197.1 kWh) is higher than that of the baseline product (136.86 kWh), its global warming impact is lower. Cutting environmental impact at the source through design and material selection is far more effective than simply reducing energy use. The extended life ensures that the initial resource and environmental costs are amortized over a longer service time.

Overall, this design successfully transforms the conventional “weight increase” into comprehensive environmental benefits through a dual strategy of “recycled material substitution” and “extended service life.” Product redesign based on multi-scenario design principles effectively challenges the traditional notion that “lightweight equals eco-friendly,” providing a compelling practical pathway toward achieving sustainable development in electronic products.

4. Conclusions

This study uses plant growth cycle science education as an entry point for environmental education. By applying multi-scenario conversion design thinking, it identifies overlapping user behavior patterns across different usage scenarios and deeply explores user-driven demands for teaching aids. This design approach offers a new pathway for the sustainable development of the Plant Growth Cycle Science Teaching Aid. Multi-scenario conversion demands teaching aids adapt to diverse instructional contexts, compelling designers to innovate functionally for efficient resource utilization and enduring product applicability—a hallmark of sustainability. Based on user behavior patterns identified through multi-scenario analysis, this study distilled 19 demand indicators. Based on the Kano model for quantitative data analysis, an optimization strategy is proposed from the perspectives of functional configuration, structural optimization, learning content selection, teaching interaction, and the construction of a teaching service system.

These optimization strategies can be summarized into two aspects: sustainable development of product functional structure and sustainable development of teaching methods and content. Applying innovative technology and modular structures provides a more standardized environment for plant growth, avoiding environmental pressures caused by resource waste and redundant product manufacturing. The sustainable optimization of teaching content and interactive methods enables children to intuitively experience ecological cycles, stimulating their active participation and systematically cultivating environmental literacy. Furthermore, it extends from basic plant growth knowledge to complex natural phenomena and environmental resource allocation, building comprehensive ecological conservation awareness.

Based on the optimization strategy, a physical model was successfully constructed, and the technology and material selection for the optimized teaching aids were discussed in detail. A comprehensive evaluation of the teaching aids was conducted across three dimensions: technical structure, pedagogical effectiveness, and environmental friendliness. The results show that the optimized teaching aids have significant technical and structural advantages over existing ones, providing good usability and interactivity and significantly improving children’s learning effectiveness. In terms of environmental friendliness, the optimized product has a lower global warming impact, even though its total power consumption is higher than that of the benchmark product. The optimized product also shows advantages in terms of resource consumption and toxicity impact. The construction of the physical model strongly promotes the implementation of the optimization strategy. The design thinking of multi-scenario transformation not only effectively extends the product’s life cycle but also provides valuable guidance for future research on plant growth cycle science teaching aids.

In the research process of multi-scenario design thinking, the adaptation of the product to the scenario is crucial, encompassing functional, size, and material-process adaptations. For this reason, it is necessary to meticulously collect and organize the key information for each scenario, which is a significant amount of work but of great importance. For the collected datasets, a data warehouse can be set up for integration and storage, and cleaning and pre-processing are carried out during the pre-collection period to remove noise and redundancy, thereby improving data quality and facilitating subsequent analysis.

However, this study still has some shortcomings. At the technical level, the high-precision sensor and intelligent management service system mentioned in the optimization strategy need to be further explored regarding multi-product function collection and system logic design. Meanwhile, an intelligent voice-guidance function can enhance children’s interactive experience and help them quickly adapt to the teaching aid products. In terms of user adaptability, the differences in teaching cognition caused by different resource configurations have not been thoroughly analyzed in detail, and further optimization is needed to study how the data processing results fit children’s cognitive stages; in terms of scalability, most of the topics are designed around common plants, and the existing teaching aids and curriculum resources can hardly support the introduction of rare species or extreme environment simulation. Therefore, the growth patterns of the teaching aids can be personalized for plant species to enhance scalability across planting categories.

At present, the basic functions of plant growth supply and demand have been secured in the trial model testing stage. In the future, the research will continue to focus on functional integration and the evaluation of teaching effectiveness and further enhance the landedness of the teaching aid products through continuous optimization and improvement, to contribute more to plant growth cycle science education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.D., D.T. and C.K.; methodology, Y.D., D.T. and C.K.; validation, Y.D. and C.K.; formal analysis, Y.D. and C.K.; investigation, Y.D. and C.K.; resources, Y.D. and C.K.; data curation, Y.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.D., D.T. and C.K.; writing—review and editing, all the authors; visualization, Y.D., D.T. and C.K.; supervision, Y.D., D.T. and C.K.; project administration, Y.D. and D.T.; funding acquisition, Y.D. and D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Diversified International Collaborative Research in Art and Design Graduate Programs, grant number 2017036, and Ministry of Education Industry-University Cooperation Collaborative Education Program Xiamen Thumb off-campus practice base construction, grant number 201702089200.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, according to the Regulations for Ethical Review of Human Life Sciences and Medical Research (2023) by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China and others; studies that do not cause harm to the human body and do not involve sensitive personal information or commercial interests are generally exempt from IRB approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to Dehong Tang (School of Industrial Design Engineering) for her support with the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDGS | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SDG4 | Fourth Sustainable Development Goal |

| ESD | Education For Sustainable Development |

| EECE | Early Childhood Environmental Education |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| ECEE | Early Childhood Environmental Education |

| RDMS | research data management services |

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

References

- Meyer, M.; Kammrad, C.; Esser, R. The Role of Experiencing Self-Efficacy when Completing Tasks—Education for Sustainable Development in Mathematics. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioupi, V.; Voulvoulis, N. Education for Sustainable Development: A Systemic Framework for Connecting the SDGs to Educational Outcomes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, D.S. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). In Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Springer: Cham, Swizterland, 2021; p. 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on Education for Peace and Human Rights, International Understanding, Cooperation, Fundamental Freedoms, Global Citizenship and Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/recommendation-education-peace-and-human-rights-international-understanding-cooperation-fundamental?hub=87862 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- UNESCO. UNESCO Sites and Their Role in Shaping Climate-Ready Learners. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-sites-and-their-role-shaping-climate-ready-learners (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Agbedahin, A.V. Sustainable Development, Education for Sustainable Development, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Emergence, Efficacy, Eminence, and Future. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasyaf, A.A. Environmental Education to Enhance Students’ Awareness of Protecting the Environment at SMAN Kerjo, Karanganyar. Transform. J. Pengabdi. Masy. 2024, 20, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Mao, R. Interaction Design of Children’s Popular Science APP Interface Based on Cognitive Development Theory. Packag. Eng. 2024, 45, 403–411. [Google Scholar]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W. Early childhood environmental education: A systematic review of the research literature. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 31, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, M.; Gash, H.; McCloughlin, T. The DigitalSeed: An Interactive Toy for Investigating Plants. J. Biol. Educ. 2008, 42, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, S. Research on the Design of Playing Teaching Aid from the Perspective of Preschool Children’s Cognitive Development. Toy World 2024, 3, 47–49. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, W.; Tang, J.; Li, S. Scene Theory in Product Interaction Design. Packag. Eng. 2017, 38, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A. The Design of Everyday Things; Vahlen: Munich, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Liu, Z. Interaction Design for Social Products Based on Contextual Changes. Packag. Eng. 2020, 41, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Chen, J. Research on New Stretcher Design Based on Scene Theory. Ind. Des. 2024, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Huang, S.; Yin, B. Scenario-based Service: New Thinking of the Design of Learning Service. e-Educ. Res. 2018, 39, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, R. Research and Application of User Behavior-Based Smart Home Product Design Methods. Packag. Eng. 2021, 42, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Feng, A.-r. Interaction Design Research Based on Usage Scenarios. Packag. Eng. 2018, 39, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xiao, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, H.; Xie, X.; Yang, Y.; Deng, M. A Study on the Classification of the Transport Needs of Patients Seeking Medical Treatment in High-Density Cities Based on the Kano Model. Buildings 2025, 15, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]