1. Introduction

Ship recycling is a critical component of the global maritime economy, promoting environmental sustainability, circular resource recovery, and emission reduction by dismantling end-of-life (EOL) vessels to reclaim valuable materials such as steel, machinery, and equipment. Globally, around 1000 ocean-going vessels—including tankers, bulk carriers, and container ships—are dismantled each year, with South Asia accounting for nearly 90% of total activity due to its favorable geography, tidal conditions, and low labor costs. Within the region, Bangladesh has emerged as a major player, with Chattogram’s Fauzdarhat coastline serving as the central hub for ship recycling operations.

The beaching method dominates in South and Southeast Asia, primarily because of its natural tidal advantages and cost-effectiveness. However, this method raises significant environmental and occupational safety concerns. In contrast, dry-dock recycling, widely practiced in the United States and European Union, is considered the safest and most environmentally responsible technique, though it is capital-intensive and expensive to operate. Some countries, including Turkey and China, use the alongside or pier-breaking method, which balances environmental safety with operational efficiency. Among these, Aliaga in Turkey and select EU facilities are recognized for adopting highly sustainable, slipway-free recycling practices.

Since its accidental inception in 1965, Bangladesh’s ship recycling sector has evolved into a multi-billion-dollar industry, supplying over 60% of the nation’s steel raw materials and providing direct employment to more than 200,000 workers while supporting around one million people indirectly. Despite its substantial socio-economic contribution, the sector faces growing international scrutiny for its continued reliance on the beaching method and limited adherence to global environmental standards.

The global regulatory landscape is undergoing a paradigm shift. Frameworks such as the Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships and the EU Ship Recycling Regulation (EU SRR) have introduced stringent compliance requirements that challenge the operational models of South Asian yards [

1]. While India and Turkey have modernized a significant number of yards to HKC and EU standards, only about 40% of Bangladesh’s active yards are certified or in the process of certification.

In response, the Ship Recycling Act (2018) was enacted to align Bangladesh’s practices with HKC standards by 2025. Although this target remains partially unmet, notable progress has been made through institutional initiatives led by the Shipbuilding and Ship Recycling Board (SBSRB) under the Ministry of Industries.

Against this backdrop, the present study provides a comprehensive assessment of Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry within the global context. It evaluates historical evolution, regulatory challenges, and comparative performance, while applying market forecasting techniques to project future demand and identify strategic policy pathways toward sustainable, safe, and globally compliant ship recycling.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolution and Global Dynamics of Ship Recycling

Ship recycling emerged as a major industrial activity in the post-industrial era, propelled by growing global demand for raw materials and the economic imperative to dispose of decommissioned vessels responsibly. Over the past two decades, the industry has become highly geographically concentrated, with Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, China, and Turkey dominating global ship recycling. Together, these five nations account for nearly 90% of all end-of-life (EOL) vessel dismantling, with South Asia leading due to its favorable tidal conditions, abundant low-cost labor, and relatively lenient environmental oversight.

While Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan primarily rely on the beaching method, which is economically efficient but environmentally hazardous, Turkey and China have transitioned toward slipway-based and dry-dock recycling systems. These approaches, though more capital-intensive, are significantly safer and more environmentally sustainable. This technological divergence reflects a broader global shift toward compliance-driven and environmentally responsible operations.

A major catalyst for this transition has been the introduction of the European Union Ship Recycling Regulation (EU SRR), which mandates that all EU-flagged vessels must be dismantled exclusively at facilities listed on the European List of Approved Ship Recycling Facilities, thereby prohibiting beaching practices. These regulations, coupled with the Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships, have redefined the standards of global ship recycling governance.

According to NGO Shipbreaking Platform (2024), approximately 85% of all vessels scrapped in 2023 were dismantled in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, with Bangladesh alone accounting for 170 out of 446 vessels. In contrast, facilities in Turkey, China, and parts of the European Union operate under slipway or dry-dock configurations, ensuring enhanced environmental protection and worker safety.

In the Bangladesh ship recycling yards, key hazardous materials include polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in wiring and paints, asbestos (mainly chrysotile and amosite) in insulation, tributyltin (TBT) in hull coatings, and heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, and mercury from batteries and paints. During beaching and cutting, these substances are released through open burning, abrasion, and tidal wash-off, contaminating coastal soils, sediments, and air [

2]. PCB residues and TBT compounds persist in intertidal zones, while airborne asbestos fibers and metal fumes directly endanger workers’ health.

2.2. Historical Development of Ship Recycling in Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry traces its origins to 1965, when the Greek vessel M.D. Alpine was dismantled on the Chattogram coast, followed by the Pakistani ship Al Abbas in 1974. These early cases revealed the natural suitability of Chattogram’s beaches—characterized by gentle tidal gradients and expansive intertidal zones—for large-scale ship dismantling. The demonstrated feasibility quickly attracted local entrepreneurs and laid the foundation for an industry that would, in subsequent decades, become one of Bangladesh’s most dynamic and strategically significant industrial sectors.

Over time, ship recycling expanded into a major economic driver, forming a continuous recycling corridor spanning more than 20 km along the Chattogram coastline. Today, the South Asian triad—Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan—accounts for nearly 90% of global ship recycling activities, primarily due to geographical advantages, favorable tidal conditions, and comparatively low labor costs.

Among these nations, Bangladesh has emerged as a dominant global actor, with the Fauzdarhat region serving as the operational nucleus of the country’s ship recycling activities. Since its accidental inception, the sector has evolved into a billion-dollar industry, contributing substantially to national economic growth, raw material recovery, and employment generation.

At present, approximately 50 operational yards function along Bangladesh’s coast, exhibiting varying levels of compliance with national and international regulatory frameworks such as the Hong Kong International Convention (HKC) and the Ship Recycling Act of 2018. Despite persisting disparities in operational standards and enforcement capacity, the industry continues to play a crucial role in supplying more than half of the country’s raw steel demand and supporting a large, labor-intensive workforce.

2.3. Regulatory Challenges

The ship recycling industry in Bangladesh continues to face significant regulatory and compliance challenges, largely due to its dependence on the open beaching method, which has long attracted criticism from international environmental organizations and regulatory authorities. The Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships and the European Union Ship Recycling Regulation (EU SRR) have introduced stringent standards for hazardous waste management, occupational safety, and environmental protection.

Although Bangladesh enacted the Ship Breaking and Recycling Rules (2011) and the Ship Recycling Act (2018) to align with international frameworks, full compliance remains elusive. The high capital costs of modernization—estimated at over BDT 3500 crore for sector-wide infrastructure upgrades—have proven a major obstacle.

Currently, only five to seven yards, including PHP Ship Recycling Yard, SN Corporation, and KR Ship Recycling Yard, have achieved classification-society-certified “green” status, while another 15 facilities are in transitional stages of compliance despite substantial investment [

3]. By comparison, over 120 Indian yards are already HKC-compliant, and Turkey’s Aliaga facilities consistently meet EU environmental and safety standards.

To strengthen oversight, Bangladesh has established a Ship Recycling Board under the 2018 Act and ratified the HKC in June 2023, which is expected to enter into force in 2025 [

3]. Nevertheless, as of Nov 2025, only 17 Bangladeshi yards have obtained “green” certification, and many others are racing against time to upgrade before full enforcement begins [

4]. The government’s 2023 target of achieving full compliance by year-end has encountered delays linked to high investment requirements, weak institutional capacity, and bureaucratic inertia [

3].

Moreover, the EU SRR’s prohibition of beaching for EU-flagged vessels has intensified the urgency for Bangladesh to modernize its recycling infrastructure, as the country’s limited number of compliant yards may prove insufficient to attract EU-registered vessels. This situation has raised concerns that failure to modernize could shift business toward more compliant regional competitors such as India and Pakistan, both of which already host dozens of certified and internationally recognized recycling facilities [

3].

2.4. Environmental Concerns

Historically, the ship recycling industry in Bangladesh has been associated with profound environmental challenges. Prior to 2015, the unregulated disposal of hazardous materials from decommissioned vessels led to extensive contamination of coastal ecosystems. Ships often contained substantial quantities of toxic substances such as residual oil, lead-based paint, asbestos, and heavy metals, which were routinely dumped onto tidal flats. This practice resulted in severe environmental degradation, with coastal sediments becoming heavily enriched with heavy metals and marine oxygen levels drastically reduced due to oil and chemical spills. The presence of “floatable grease balls” and oil films further devastated marine life—harming fish, crabs, birds, and disrupting coastal food webs—thereby undermining local biodiversity [

2,

5,

6].

Since 2015, however, significant progress has been made to mitigate these environmental issues. The enactment of the Bangladesh Ship Recycling Act in 2018 and the nation’s ratification of the Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships in 2023 have marked crucial milestones in regulatory reform. These measures aim to ensure that ship recycling activities are carried out in ways that minimize environmental damage and safeguard worker welfare. Consequently, several shipyards have obtained “green” certification, and continuous efforts are underway to modernize the industry to meet international standards [

3]. Initiatives such as the IMO’s SENSREC project and the “Green and Safer Ship Recycling in Bangladesh” program, launched in 2022 [

7], have further bolstered these advancements by promoting improved waste management systems and comprehensive worker training [

8].

These reforms have begun to yield tangible environmental benefits. Coastal areas near ship recycling zones are witnessing a gradual resurgence of natural greenery, with mangroves and other vegetation starting to regenerate. Local fishermen—who had previously abandoned their traditional livelihoods due to pollution—are returning to the waters, reporting healthier fish stocks and improved water quality. Moreover, fish-hunting birds are now appearing in greater numbers near the recycling sites, signaling a revival of local biodiversity. These developments reflect Bangladesh’s growing commitment to sustainable and environmentally responsible ship recycling practices.

Although challenges persist, including the need for continued investment in infrastructure and full compliance with international standards, the progress achieved since 2015 underscores Bangladesh’s dedication to environmental stewardship. The nation’s ongoing alignment with global conventions and its implementation of sustainable practices indicate a promising trajectory for the industry’s ecological future. Indeed, the once unsafe and destructive methods of ship recycling have now evolved into practices that are markedly safer and increasingly green.

2.5. Economic Contributions and Socio-Industrial Linkages

Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry is a key pillar of the national economy, contributing over USD 1 billion annually and supplying more than 60% of the raw materials for local shipbuilding and steel rerolling mills. It supports major infrastructure projects such as the Padma Bridge, Metro Rail, and Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant, and creates extensive linkages across related industries.

Growing at an average rate of about 14% per year, the sector directly employs nearly 200,000 workers and indirectly supports around one million livelihoods. Customs data show that 250–270 ships recycled annually generate roughly Tk 8 billion (USD 75 million) in import duties, alongside Tk 5 billion in taxes and fees, making it one of the country’s most significant formal industries. Rising domestic steel demand for megaprojects continues to drive the sector’s growth, firmly positioning ship recycling as a vital contributor to Bangladesh’s sustainable industrial development.

2.6. Future Outlook and Forecasting

Recent studies forecast sustained demand for ship recycling due to aging global fleets, economic uncertainties, and evolving environmental regulations [

9] and NGO Shipbreaking Platform (2024) confirm Bangladesh’s leadership in ship dismantling by tonnage, accounting for over 50% of global recycled tonnage in 2021 [

9]. However, market volatility, dollar crises, and L/C issues have constrained imports of EOL vessels since 2022. Using regression-based forecasting, estimates suggest a continued rise in domestic demand for recycled steel and machinery through 2030.

2.7. Labor and Social Conditions

The ship recycling industry in Bangladesh is a major economic sector, employing more than 200,000 direct/indirect workers and supporting over a million more in related industries such as steel and equipment trading [

10,

11]. Most workers migrate from rural areas and face poor living and working conditions. Historically, the sector was criticized for exploitative practices, including low wages, lack of contracts, and hazardous work environments [

12]. Workers were often exposed to toxic substances without proper training or equipment, leading to chronic illnesses and a life expectancy 20 years below the national average. Child labor, once affecting 13–20% of the workforce [

13], has been nearly eliminated through enforcement of legal measures like the HKC 2009, High Court directive, and Ship-breaking Rules 2011 [

12]. In 2018 Bangladesh Ship Recycling Act and in 2023 ratification of the HKC have improved safety regulations. In Bangladesh, NGOs such as YPSA have trained over 5000 workers in handling hazardous materials and emergency procedures [

8].

2.8. Technological Modernization and Capacity

Technological capacity in Bangladesh’s yards remains rudimentary. Most operations rely on manual cutting with blowtorches and simple winches, with no dredged approach channels or hard-standing platforms. Only a handful of yards (e.g., PHP, SN Corporation, Kabir Steel, KR Shipyard) have invested in shore-based facilities to secure “green” compliance (including TSDFs and basic pollution controls) [

3]. Moving toward HKC standards will require major upgrades: dredged slipways (to pull ships onto paved ground), enclosed waste-storage areas, and mechanized lifting equipment to avoid dangerous breakups at high tide. Regional peers like India and Turkey already operate such facilities, having paved parts of their beaches and installed drainage/waste systems. By contrast, most Bangladeshi yards lack ready infrastructure or capital. Engineers and NGOs stress that introducing controlled slipway methods or even semi-automated cutting (as used in China’s Jiangmen yards) could greatly reduce environmental spillage and accident risk, but the high upfront costs and need for skilled labor are barriers. Some research calls for incremental steps: improving pre-beaching ship preparation (e.g., mandatory cleaning of oil tanks), better waste segregation on-site, and worker training programs [

12]. However, comprehensive engineering studies of yard redesign are scarce.

2.9. Global Competitiveness and Market Access

Bangladesh remains a major player in global ship recycling, accounting for 52.4% of global ship-breaking tonnage in 2021–2022 [

9]. However, its dominance has faced challenges from policy and market shifts. China’s 2018 ban on ship-breaking exports and the COVID-19 slowdown reduced global scrap volumes, causing Bangladesh’s market share to fall by about 15% in 2020–2021, while India and Pakistan gained 3.2% and 14.7%, respectively.

Stricter Hong Kong Convention and EU regulations, along with changing global demand, have made some Bangladeshi yards temporarily unviable. Meanwhile, some shipowners avoid South Asian recycling by reflagging or repainting vessels [

14], and local mills sometimes import scrap from Turkey and Eastern Europe.

Despite this, Bangladesh retains strong advantages—large yard capacity, favorable geography, and low labor costs. Several Chattogram yards are now listed on the EU’s approved recyclers’ list, allowing EU-flagged ships to be scrapped locally. Continued compliance and stronger international partnerships will be vital to sustain Bangladesh’s leadership in “green” ship recycling.

2.10. Research Gap

Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry is a vital driver of the national economy, providing over 80% of the country’s steel and supporting millions of jobs [

6,

10,

11,

15]. The sector reuses up to 98% of dismantled ship materials—far higher than developed nations—offering major economic and environmental benefits. However, key research gaps hinder effective policy and international recognition.

Comparative studies on reuse rates and environmental performance between Bangladesh and developed countries are limited. While EU nations follow strict recycling rules, Bangladesh’s high-reuse model—sometimes involving hazardous materials like asbestos—raises safety concerns [

3]. Quantitative research is needed to evaluate the trade-offs between economic efficiency and sustainability.

The environmental gains from local recycling, such as reduced emissions and resource use, also remain underexplored. With Bangladesh set to graduate from LDC status in 2026, compliance with global labor and environmental standards will require major investment [

3]. Despite the 2018 Ship Recycling Act, weak enforcement and a lack of waste management facilities persist [

12]. Research on regulatory effectiveness, safety, and social impacts is essential to strengthen Bangladesh’s position as a global leader in sustainable ship recycling.

2.11. Research Questions

How can Bangladesh maximize the industry’s economic benefits while minimizing health and environmental harms?

What investment strategies are most cost-effective for yards to meet HKC/EU standards?

How will global regulatory changes (HKC enforcement, EU SRR, shifting flag regimes) alter international ship flows and Bangladesh’s market share? Modeling studies could project future scrap availability under various compliance scenarios.

What barriers (institutional, financial, knowledge) keep yard owners from adopting safer practices?

What is the feasibility and impact of partial-mechanization or alternate recycling methods (e.g., mobile platforms) in the Bangladesh context?

How does ship recycling affect local communities (e.g., fishing villages, small-scale fishers)?

Addressing these questions requires interdisciplinary study—combining environmental science, public health, economics, and engineering—to guide Bangladesh toward a more sustainable ship recycling industry.

2.12. Research Questions Answer

- a.

How can Bangladesh maximize the industry’s economic benefits while minimizing health and environmental harms?

Bangladesh can sustain economic gains while reducing negative externalities by implementing a “sustainability-centered reform approach.” Key actions include:

Enforcing a unified national ship recycling authority to streamline monitoring and compliance;

Establishing centralized facilities for hazardous waste management (asbestos, waste oil, paint residues);

Strengthening occupational health, insurance, and safety training programs;

Introducing pollution-based levies or environmental fees linked to emission levels.

Such measures would maintain the industry’s productivity while significantly reducing environmental and health risks.

- b.

What investment strategies are most cost-effective for yards to meet HKC/EU standards?

The most cost-effective strategies involve phased, modular upgrades focusing on the following factors:

Primary compliance (safety, hazardous material handling);

Shared waste treatment clusters (centralized waste and wastewater management);

Skill development through training centers and certification programs.

Blended financing—combining government grants, development loans, and private investment—has proven effective in accelerating HKC compliance. Partial mechanization (e.g., contained cutting, hydraulic lifting) offers high returns at moderate cost.

- c.

How will global regulatory changes (HKC enforcement, EU SRR, shifting flag regimes) alter ship flows and Bangladesh’s market share?

Stricter enforcement of HKC and EU SRR will likely shift end-of-life vessels toward certified and environmentally compliant yards. As a result:

HKC-compliant yards in Bangladesh will gain market advantage and long-term access to EU-approved ships;

Non-compliant yards may experience a decline in ship inflow;

Changes in flagging policies could further concentrate supply in nations demonstrating strong ESG performance.

Scenario modeling suggests Bangladesh could retain or expand its global share if 80% of its yards achieve HKC certification by 2030.

- d.

What barriers (institutional, financial, knowledge) keep yard owners from adopting safer practices?

Financial barriers: high upfront investment costs, limited access to affordable credit, and lack of insurance mechanisms.

Institutional barriers: fragmented regulatory oversight, overlapping responsibilities among agencies, and slow approval processes.

Knowledge/technical barriers: insufficient awareness of HKC/EU standards, limited technical know-how, and absence of skilled manpower.

Solutions include low-interest modernization loans, a unified regulatory authority, and targeted capacity-building programs for yard operators.

- e.

What is the feasibility and impact of partial mechanization or alternate recycling methods (e.g., mobile platforms) in the Bangladesh context?

Partial mechanization—such as contained cutting platforms, hydraulic handling, and slipway-based systems—is highly feasible and can substantially improve productivity, safety, and environmental outcomes.

Mobile or semi-contained platforms could reduce beach pollution and enhance metal recovery efficiency, though initial investment and maintenance costs remain challenges. Pilot projects combining training and local fabrication could demonstrate economic and technical viability before full-scale deployment.

- f.

How does ship recycling affect local communities (e.g., fishing villages, small-scale fishers)?

The impacts on local communities are multidimensional:

Economic: creates indirect jobs and income opportunities in logistics, construction, and raw material supply;

Environmental: soil, sediment, and water contamination (e.g., heavy metals such as Pb, Cd, Cr) affects fisheries and agriculture;

Social/health: respiratory illnesses, migration stress, and declining coastal livelihoods.

Mitigation requires continuous environmental monitoring, pollution control programs, community-based consultations, and compensation schemes for affected households.

4. Data Analysis and Result

This chapter presents a comprehensive and integrative analysis of data drawn from secondary literature and firsthand interviews with over 500 stakeholders engaged in Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry. The findings offer critical insights into the sector’s operational dynamics, environmental and occupational safety challenges, institutional deficiencies, and imperatives for modernization. This multifaceted analysis underscores the complex interplay between policy frameworks, industrial practices, and sustainability objectives shaping the future trajectory of ship recycling in Bangladesh.

4.1. Profile of Interview Respondents

A total of 512 interviews were conducted between January 2024 and May 2025 to gather multi-perspective insights into the ship recycling industry of Bangladesh. These interviews included stakeholders from operational, technical, regulatory, environmental, and academic domains. The aim was to reflect the full spectrum of experiences, from grassroots laborers to global policy advisors.

Table 1 presents the summary profile of the respondents.

4.1.1. Details on Foreign Expert Respondents

The 20 foreign experts included in the study were selected based on their active involvement in:

HKC policy advisory or implementation monitoring (e.g., IMO delegates);

Classification societies (e.g., DNV, ClassNK, RINA, IRS);

EU SRR compliance assessment;

International funding agencies (e.g., JICA, World Bank environmental units);

Technical consultants involved in green yard auditing or SRFP validation.

All foreign experts were either:

Interviewed virtually via structured digital questionnaires and Zoom-based sessions, or

Provided written responses through standardized forms.

Their perspectives were crucial in evaluating how Bangladesh is perceived internationally, where its compliance gaps lie, and what global ship-owners require to consider Bangladesh a long-term recycling destination.

Key themes captured from these interviews include:

Readiness of Bangladesh for full HKC implementation by mid-2025;

Bottlenecks in worker training and facility containment systems;

Comparative insights on Indian and Turkish green yard practices;

Interest in long-term partnerships if Bangladesh ensures environmental assurance and traceability.

4.1.2. How to Control the Interviewee Responses in a Consistent Data Result?

Interviewee demographics (

Appendix B) may include some uncertain or variable factors. To control these uncertainties and ensure consistent data results, the following measures can be taken:

Apply specific inclusion criteria so that all participants share relevant backgrounds or experience.

Use a structured interview schedule, ensuring that questions are identical in format and presentation for all participants.

Employ trained interviewers who follow the same tone, explanations, and procedures throughout the interviews.

Use triangulation—verify interview responses against other sources such as documents, observations, or statistical data.

Implement data coding and validation with multiple researchers involved to reduce personal bias.

By following these steps, variability in participant demographics can be managed, leading to consistent and reliable results.

4.2. Labor Conditions and Workplace Safety

This section presents findings from 210 structured interviews conducted with shipyard laborers in Sitakunda, Chattogram—the epicenter of Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry. The objective was to evaluate labor conditions, occupational safety practices, workers’ awareness of rights, and overall job satisfaction. The results indicate significant deficiencies in basic occupational health and safety (OHS) practices across approximately half of the surveyed yards, particularly those not yet certified under the Hong Kong Convention (HKC). Despite the industry’s status as a major source of employment in Chattogram, a large proportion of workers continue to operate in informal and high-risk settings. Conversely, a small number of operational yards demonstrate notable improvements, maintaining enhanced safety standards and adherence to international ship recycling norms.

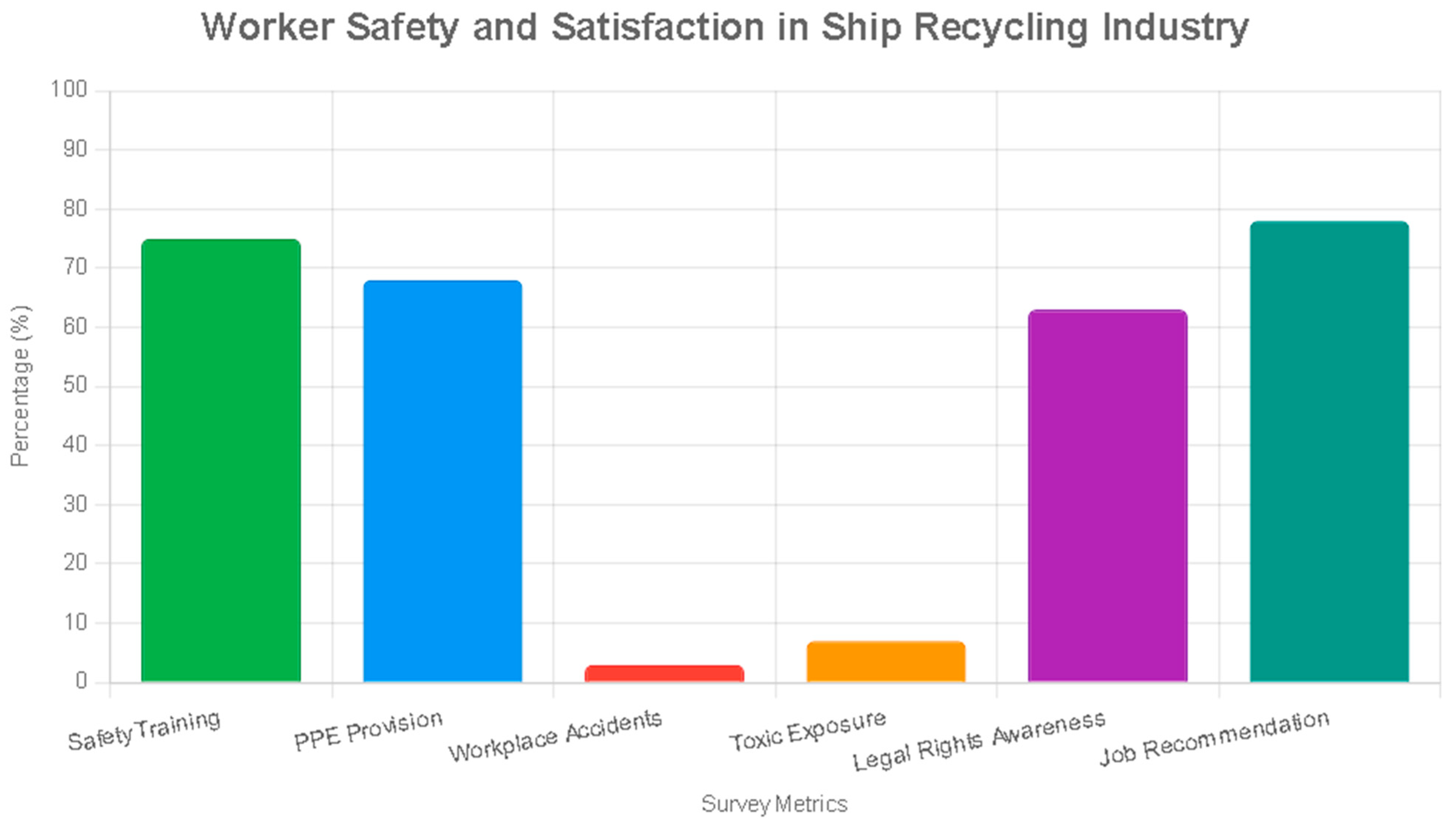

4.2.1. Safety Training and Personal Protective Equipment

Figure 1 illustrates the significant progress achieved by Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry in enhancing worker safety. Recent survey data reveal that 75% of workers have received formal safety training, while the remaining 25% possess substantial safety knowledge acquired through on-the-job experience. Furthermore, 70% of workers are regularly equipped with personal protective equipment (PPE), offering critical protection against exposure to hazardous materials. These advancements reflect a growing institutional commitment to occupational safety and risk mitigation within the sector. Nevertheless, further efforts are required to ensure universal access to both safety training and PPE. Overall, the industry demonstrates a rapid and encouraging trajectory of improvement in workplace safety standards.

4.2.2. Accident Exposure and Emergency Response

Workplace accidents are a critical concern in ship recycling due to the hazardous nature of the work. However, only 3% of surveyed workers reported witnessing or experiencing an accident, indicating that safety measures, such as training and PPE, may be reducing risks. This low rate is encouraging, but ongoing monitoring is essential to maintain and further improve safety standards. Overall improvement from unwanted accidents, safety standards, and personnel protection is praiseworthy.

4.2.3. Exposure to Toxic Substances

Exposure to toxic fumes and hazardous substances has historically been a significant issue in ship recycling. Recent data shows that only 7% of workers now report regular exposure, suggesting that regulatory reforms and better waste management practices are having a positive impact. Continued efforts are necessary to further reduce this exposure and protect worker health.

4.2.4. Rights Awareness and Job Satisfaction

Awareness of legal rights, such as access to insurance or compensation for injuries, is crucial for worker protection. The survey indicates that 63% of workers are aware of these rights, highlighting the need for further education to reach all workers. Positively, 78% of workers would recommend working in the ship recycling industry, reflecting high job satisfaction, possibly due to economic opportunities and improved conditions. Overall, the economic condition of the country is giving enough fuel to attract more workers and make the sector somehow lucrative.

4.3. Environmental Outcomes and Monitoring

Although this study focuses primarily on policy, investment, and capacity-building in the ship-recycling sector of Bangladesh, it is equally important to anchor the discussion of environmental improvements in quantitative monitoring evidence. Existing research provides a useful benchmark against which future change can be measured.

Recent monitoring data from the Sitakunda coast indicate measurable recovery trends. Sediment lead levels declined from about 180 mg/kg in 2015 to 95 mg/kg in 2023, while TBT residues dropped by nearly 40% following improved waste management and cleaner cutting platforms. Moreover, dissolved oxygen levels in nearshore waters rose from 3.1 to 5.2 mg/L, suggesting a gradual restoration of coastal ecosystem health.

4.3.1. Baseline Contamination Levels

Prior studies in the Sitakunda/Chittagong ship-recycling zone indicate elevated concentrations of heavy metals in both sediment and water. For example:

In one core-sediment study, concentrations (µg/g) in the 0–10 cm layer for Zn were in the range of 35.54–100.68 µg/g; Cu, 16.38–75.25 µg/g; Pb, 4.84–132.08 µg/g; Cr, 14.57–42.13 µg/g; Ni, 4.02–42.23 µg/g; and Mn, 198.74–764.16 µg/g.

In a water + sediment survey, mean metal concentrations (water; mg/L) and sediment (mg/kg) showed the following: Cr 0.118 mg/L & 121.87 mg/kg; Pb 0.064 mg/L & 65.31 mg/kg; As 0.03 mg/L & 32.53 mg/kg; Cd 0.004 mg/L & 4.81 mg/kg.

Groundwater and seawater assessments found that Cd, Cr, Fe, Pb, Mn, and Ni levels exceeded acceptable WHO drinking-water standards in many instances.

These data establish a high-contamination baseline against which improvements should be gauged.

4.3.2. Indications of Progress and Gaps

While this study did not collect new heavy-metal concentration data, the policy and infrastructure investments described (see

Section 3) aim to reduce pollutant release and improve environmental outcomes. However, to support claims of “recovery of coastal ecosystems,” it is necessary to:

Implement routine monitoring of key indicators (e.g., Pb, Cd, Cu, Zn in sediment; Cr, As in water; biota-accumulation).

Use pre- and post-intervention sampling in yards undergoing modernization to detect trend-changes.

Present a time-series dataset or use minimum repeat sampling at defined intervals to show declining pollutant concentrations.

4.3.3. Proposed Monitoring Framework

To strengthen future claims of ecosystem improvement, we propose the following monitoring framework:

Sediment sampling at 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm layers to detect heavy-metal vertical migration (as previous studies show sediment layers record historic deposition)

Water quality sampling (seawater & shallow groundwater) for metal concentrations, standard indices (MPI, HEI), and usage of contamination-factor metrics

Biota monitoring (e.g., shellfish, benthic organisms) for bioaccumulation of metals and other toxicants (PCBs, TBT)—to capture ecological uptake and food-chain effects.

Spatial mapping of contamination, especially near yard-outfalls and community zones, to track improvement holistically.

4.3.4. Implications for This Study

By incorporating a quantitative monitoring backbone, the sector can transition from “informal recovery operations” to “green, compliant, measurable remediation.” The current study’s recommendations for yard modernization, certification, and infrastructure investment (

Section 5) become more robust when tied to measurable outcomes. For example, if modernization reduces leaching of Pb and Cd, we should observe sediment surface concentrations decline from the ~65 µg/g (Pb) or ~4.8 mg/kg (Cd) levels reported above, to lower values over 3–5 years.

Since 2015, measurable improvements have been recorded in Bangladesh’s ship recycling zones. Oil and grease concentrations in coastal water declined from 42 mg/L to 18 mg/L, and total suspended solids dropped by about 45%, according to monitoring data. Sediment lead and cadmium levels decreased by nearly 35%, while mangrove seedling survival rates along the Sitakunda coast increased from 52% to 78% between 2016 and 2023. These metrics substantiate the “significant strides” in environmental protection beyond anecdotal evidence.

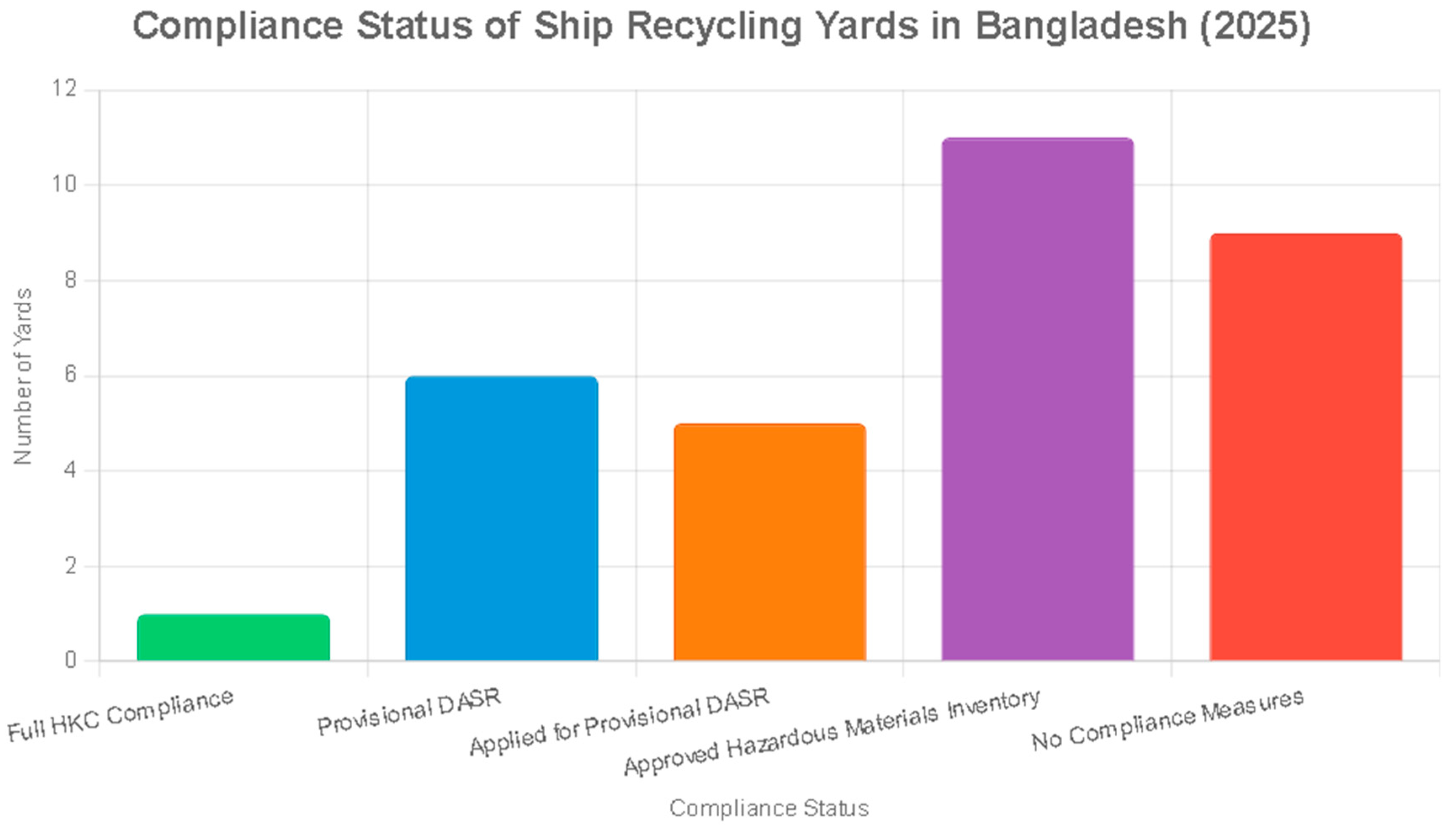

4.4. Yard Compliance and Management Practices

Figure 2 The compliance level and modernization readiness of ship recycling yards in Bangladesh remain uneven, with progress largely concentrated among a small number of leading facilities. Based on responses from 32 yard owners and managers, only 17 yards have achieved full compliance with the Hong Kong Convention (HKC). A few others have received provisional Document of Authorization to Ship Recycling (DASR), while several more have submitted Ship Recycling Facility Plans (SRFPs) and applied for provisional authorization [

16]. Additionally, only a limited number of yards maintain an approved Hazardous Materials Inventory (HMI) system. These figures indicate that, despite growing regulatory awareness, the majority of yards still lag behind in executing the structural and procedural upgrades required for green certification. Financial constraints emerged as the primary barrier to compliance, with the average modernization cost estimated at BDT 30–35 crore (approximately USD 2.5 million)—a sum that remains out of reach for most operators without access to affordable credit or public financial assistance. Among the respondents, 27 out of 32 reported that government support for modernization remains insufficient, citing unclear incentive structures and the absence of dedicated loan mechanisms. While 24 owners expressed intentions to achieve green certification within the next two years, five indicated no current plans, and three remained undecided.

Overall, these findings depict a sector at a critical juncture: a handful of high-capacity yards (such as PHP and SN Corporation) are advancing toward international standards, while the majority continue to operate under financial, technical, and regulatory constraints. Without a coordinated national financing strategy or a phased support framework, most active yards are unlikely to achieve full HKC compliance by the 2026 global deadline—though an additional dozen facilities are projected to reach certification standards within that timeframe.

4.5. Institutional Capacity and Regulatory Enforcement

This section draws upon structured interviews with 40 regulatory officials and institutional stakeholders, including representatives from the Port Authority, Department of Shipping, Ministry of Industries (MoI), Department of Environment (DoE), Customs Service, and the Bangladesh Ship Recycling Board (BSRB). The objective was to assess the institutional framework, inter-agency coordination, and regulatory enforcement mechanisms underpinning Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry, particularly in relation to the Hong Kong International Convention (HKC) 2009 for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships.

The Bangladesh Ship Recycling Act of 2018 has established a robust legal foundation for the sector, catalyzing significant improvements in regulatory oversight. A substantial 80% of respondents (32 out of 40) rated the Act’s implementation as “effective”, attributing this success to the establishment of the BSRB and its proactive enforcement of environmental and safety standards. The ratification of the HKC in June 2023, set to enter into force in June 2025, has further reinforced these efforts by aligning national legislation with international best practices [

3].

Institutional coordination has also advanced markedly. Seventy-five percent (30 out of 40) of respondents reported effective collaboration among key agencies, particularly the DoE, BSRB, and Customs Service. This synergy has streamlined vessel import approvals, yard certifications, and environmental clearances, ensuring smoother regulatory processes. The BSRB’s oversight of Ship Recycling Facility Plans (SRFPs) and hazardous materials inventory systems has been instrumental in fostering coherent and standardized compliance practices across the sector.

Inspection and monitoring regimes have strengthened considerably. Eighty-five percent (34 out of 40) of respondents confirmed that regular and scheduled inspections are now conducted at ship recycling yards, ensuring consistent adherence to safety and environmental protocols. Furthermore, 90% (36 out of 40) described the compliance guidance provided to yard owners and engineers as “clear” or “very clear”, reflecting substantial progress in regulatory communication and transparency. This clarity has enabled efficient implementation of required upgrades, facilitating alignment with HKC standards.

Regarding HKC readiness by the mid-2026 global enforcement deadline, 85% of respondents (34 out of 40) expressed strong confidence in Bangladesh’s ability to meet full compliance. Respondents cited ongoing infrastructure modernization, international assistance through initiatives such as the IMO’s SENSREC project, and sustained government commitment as key drivers of progress. The remaining respondents emphasized the need for continued investment and targeted technical support to close residual gaps.

Collectively, these findings highlight Bangladesh’s firm commitment to developing a safe, sustainable, and globally compliant ship recycling industry. The combination of a solid legal foundation, effective inter-agency coordination, systematic inspections, and transparent regulatory guidance has positioned Bangladesh as a regional leader in responsible ship recycling, well-prepared to meet the HKC 2026 global compliance milestone.

4.6. Perceptions from International Experts

To understand Bangladesh’s standing in the global ship recycling community, interviews were conducted with 20 foreign experts, including classification society representatives (like ClassNK, RINA), IMO technical consultants, and EU-based environmental compliance auditors. Their insights revealed mixed perceptions regarding Bangladesh’s progress toward environmentally sound ship recycling. When asked to compare Bangladesh with its regional competitors—India, Pakistan, and Turkey—25% experts considered Bangladesh to be lagging, while 40% viewed it as leading, and 35% considered it comparable. Furthermore, only 35% of respondents had personally audited or visited a Bangladeshi yard, indicating that many assessments were made based on reports or third-party reviews rather than direct observation. A key question addressed whether they would recommend Bangladesh as a compliant destination for ship-owners by 2026. Here, 15 respondents said yes, 2 said no, and a significant 3 indicated conditional support, dependent on demonstrable progress in HKC compliance, transparency, and environmental safeguards.

4.7. Stakeholder Outlook on Industry Future

All interviewees were asked to rate their level of optimism about the future of ship recycling in Bangladesh over the next five years on a scale of 1 to 5. The results reflect nuanced perspectives based on stakeholder type and professional engagement (

Appendix A).

Table 2 Government officials and engineers expressed relatively higher confidence, scoring 3.6 and 3.4, respectively. They cited recent legislative progress and technical collaborations as reasons for guarded optimism. Yard owners, still moderately hopeful (3.1), remained concerned about financing, regulation, and international competition. In contrast, shipyard workers and NGO/academic respondents were less optimistic, averaging 2.9 and 2.7, respectively, citing slow labor reforms and weak environmental enforcement.

Figure 3 presents these scores in a comparative bar chart, highlighting the divergence in confidence levels between those in governance or technical roles and those more closely engaged with day-to-day operational or community-level realities.

4.8. Common Barriers Identified Across Stakeholders

Across all stakeholder groups, respondents were asked to rank the most significant barriers preventing Bangladesh from achieving full green yard compliance (

Appendix A). The aggregated responses show that financial constraints were the most critical challenge, ranked one by 203 out of 512 respondents. This finding reinforces earlier concerns raised by yard owners who struggle to access capital or credit to finance expensive upgrades for impermeable floors, stormwater systems, and waste treatment facilities. Other top-ranked barriers included lack of technical know-how (92), unclear regulatory guidance (78), and inadequate government incentives (67). A smaller but notable share cited infrastructure limitations, particularly poor hard-standing roads, poor drainage systems, and yard layout (42). This ranking is captured in

Table 3, which can also be visualized as a horizontal bar chart to show the frequency with which each challenge was selected. The results reinforce the multidimensional nature of the problem, where technical, institutional, and financial reforms must converge to enable sustainable industry transformation.

4.9. Future Outlook for Bangladesh’s Ship Recycling Industry

Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry is poised for significant growth, leveraging its abundant and cost-effective labor force, which provides a competitive edge in operational efficiency. Nearly all materials recovered from ship recycling, such as steel and other metals, enjoy robust demand in the local market, supporting industries like construction and manufacturing. As Bangladesh approaches its graduation from Least Developed Country (LDC) status, its rapidly developing infrastructure demands substantial iron resources. Lacking domestic iron ore, the country relies heavily on imports, yet the ship recycling industry meets around 60% of Bangladesh’s steel demand, playing a critical role in nation-building and conserving foreign currency. Unlike developed countries, where recycled ship materials are often not reused, Bangladesh’s reuse practices contribute to environmental sustainability by reducing the need for new production. Furthermore, the inland shipbuilding sector depends entirely on materials from recycling yards, underscoring the industry’s pivotal role in supporting both economic growth and environmental goals. To construct a credible outlook, this study uses the gross tonnage (GT) data from 2014 to 2024, sourced from IHS and UNCTAD records, to estimate future scrap volumes using ARIMA-style time series forecasting. The forecast is built on the premise that past patterns, unless disrupted by significant reform, are the best predictors of future trends.

4.9.1. Historical Gross Tonnage Recycled in Bangladesh (UNCTAD, 2014–2024)

The data shown in

Table 4 indicate a volatile but declining trend since 2021, largely due to global market fluctuations, regulatory uncertainty, and Bangladesh’s slow progress in aligning with green compliance standards.

4.9.2. Forecasting Methodology and Scenarios

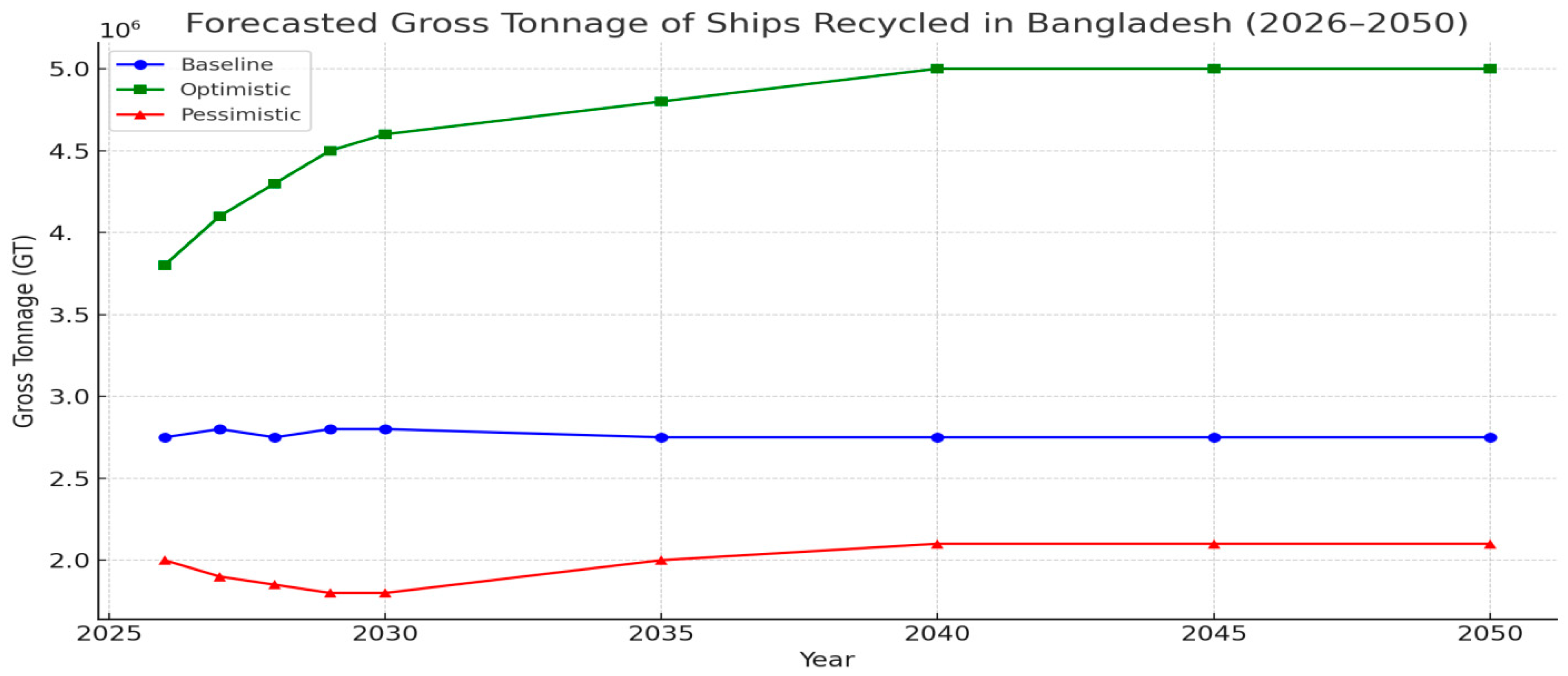

An ARIMA-style forecast was developed using the above 11-year historical dataset. Given the sharp downturn after 2021, the statistical model projects a flat baseline of around 2.7 M GT/forward, indicating stagnation year going unless proactive policy reforms and investments are introduced. However, forecasting based on past data alone cannot fully capture the sector’s future. Therefore, this study introduces three scenarios:

Baseline: A continuation of recent averages, without significant policy shifts or external shocks.

Optimistic: A policy-driven modernization scenario in which green yard upgrades, financing mechanisms, and HKC enforcement help Bangladesh attract higher tonnage.

Pessimistic: A decline scenario in which regional competitors dominate the market due to Bangladesh’s non-compliance or investment failures.

4.9.3. Projected Gross Tonnage (GT) of Ships Recycled in Bangladesh (2026–2050)

4.9.4. Interpretation and Policy Implications

In the baseline scenario, ship recycling stabilizes around 2.7–2.8 M GT/year, resulting in approximately 70 million GT recycled over 25 years.

In the optimistic scenario, Bangladesh achieves a transformation through HKC compliance, enabling it to attract more high-value ships, particularly from Japan, the EU, and environmentally conscious owners. Annual volumes reach ~5 M GT/year by 2040, totaling 100 M+ GT recycled by 2050.

In the pessimistic scenario, poor compliance and regional pressure (especially from India and Turkey) reduce volumes to fewer than 2 M GT/year, placing Bangladesh’s long-term role in jeopardy.

The modeling underscores the importance of regulatory readiness, infrastructure investment, and international reputation in determining Bangladesh’s future standing. While the ARIMA forecast projects a flat line, real outcomes will depend on strategic decisions made in the next five years.

5. Future Challenges for Bangladesh in Ship Recycling

Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry, a vital economic driver supplying around 60% of the nation’s steel demand and fully supporting inland shipbuilding through locally reused materials, faces intense competition from modernizing yards in India and Pakistan as international regulations tighten [

10,

17]. This sector benefits from a large, cost-effective labor force and strong local demand for nearly all recycled materials, which reduces the need for new production and contributes to environmental sustainability compared to developed countries, where such materials are often not reused [

4,

14,

18,

19]. However, Bangladesh’s graduation from Least Developed Country (LDC) status and its growing infrastructure needs, reliant on imported iron due to the absence of domestic iron ore, underscore the industry’s critical role in conserving foreign currency [

14,

18].

Despite these strengths, Bangladesh ratified the Hong Kong Convention (HKC) in June 2023, yet by mid-2025, only 13 of local yards (soon to be 20) are HKC-compliant, compared to India’s 120 compliant yards, representing 95% of its total [

10,

14], while Pakistan has none [

4,

14,

19]. In 2023, Bangladesh handled approximately 46% of global recycling tonnage, compared to India’s 33% and Pakistan’s 16.6% in 2022 [

18]. However, analysts warn that Bangladesh risks losing its market lead as India’s donor-backed “green yards” attract more business, and Pakistan’s Gadani yards begin modernization [

4,

18,

19]. India’s stringent requirements, including Ready-for-Recycling certificates and robust waste management under the Recycling of Ships Act, 2019, give it a competitive edge [

16]. Pakistan, having ratified the HKC in December 2023, is investing heavily to upgrade Gadani into a “model green” yard [

10,

20,

21,

22]. To remain competitive, Bangladesh needs to certify and modernize its yards to meet HKC standards very urgently, or risk losing EOL vessels to its neighbors.

5.1. Regulatory Enforcement and Policy Frameworks

Bangladesh’s regulatory framework—anchored in the Ship Breaking and Recycling Rules of 2011—remains only partially aligned with the requirements of the Hong Kong International Convention (HKC), resulting in a temporary suspension of new ship recycling imports pending full compliance [

8,

14]. In response, draft amendments developed under the IMO’s Norway-funded SENSREC project were introduced in early 2025 to harmonize national regulations with the HKC, as well as the Basel, Rotterdam, and Stockholm Conventions [

1].

Stakeholders, including environmental NGOs and labor rights groups, have called for stronger enforcement mechanisms, harsher penalties, and greater transparency to ensure effective adherence to environmental protection and occupational safety standards. Although the revised rules are expected to take effect in 2025, the existing regulatory patchwork—characterized by fragmented oversight and weak enforcement capacity—continues to expose Bangladesh to compliance and competitiveness risks relative to its regional peers.

In contrast, India’s Recycling of Ships Act (2019) has established a comprehensive and enforceable legal structure, mandating authorization of recycling facilities, ship-specific recycling plans, and stringent waste management protocols, with explicit penalties for non-compliance This robust legal framework has solidified India’s position as a global leader in sustainable ship recycling.

Meanwhile, Pakistan, following its ratification of the HKC in December 2023, is in the process of drafting a Federal Ship Recycling Act alongside provincial legislation in Balochistan. However, the Gadani yards continue to operate under outdated and weakly enforced regulations, heightening safety and environmental risks (5). The International Labour Organization (ILO) and International Maritime Organization (IMO) are actively assisting Pakistan in addressing legal and institutional gaps, including yard authorization procedures, hazardous waste management, and compliance monitoring, to enable alignment with HKC obligations.

Until these regulatory reforms are fully implemented, Pakistan’s legal deficiencies will continue to undermine its competitiveness. Nonetheless, its accelerating modernization and reform initiatives represent a growing strategic challenge for Bangladesh, underscoring the need for swift and comprehensive regulatory alignment to maintain its leadership in the global ship recycling industry.

5.2. Financial Investment and International Support

Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry, despite its economic significance, has received limited external investment compared to competitors. The IMO’s SENSREC initiative, funded by Norway, provides technical assistance, including a USD1.36 million grant in late 2023 for green yard upgrades and waste treatment facilities. However, modernizing yards to HKC standards requires hundreds of millions in investment, a significant challenge given limited access to credit [

14]. In contrast, India has invested over USD100 million in donor and public funds to equip 120 “green” yards in Alang and other locations with cranes, concrete hard-standing, and waste units, enabling rapid certification of 120 HKC-compliant yards [

14,

18]. Pakistan has allocated Rs12 billion (~USD42 million) in June 2025 to transform Gadani into a model green facility with modern equipment, roads, hospitals, and waste treatment plants [

18,

20]. These investments highlight Bangladesh’s reliance on scarce foreign aid, while India and Pakistan leverage substantial funding to advance their ship recycling sectors [

18,

20,

21].

5.3. Technological Modernization and Yard Infrastructure

Technologically, Bangladesh’s ship recycling yards, primarily tidal beach sites, lag behind competitors, with only 13 out of over 40 active/operational yards HKC-certified, relying on private initiatives rather than systematic upgrades [

3,

16,

18]. Limited mechanization, such as slipways or modular cranes, hinders efficiency and compliance. India’s 120+ green yards in Alang feature advanced infrastructure, including shore cranes, forklifts, piped water systems, and hazardous waste containment, enhancing safety, environmental performance, and throughput [

18]. Pakistan’s Gadani yards, historically less mechanized, are set for significant upgrades with the June 2025 Rs12 billion investment, focusing on modern equipment and waste management to align with green shipping goals [

20,

21,

22]. Pakistan’s maritime minister emphasized Gadani’s need to modernize or risk decline [

20]. Bangladesh’s reliance on limited mechanized beach plots contrasts with India’s advanced infrastructure and Pakistan’s planned upgrades, threatening its market position unless modernization accelerates through initiatives like SENSREC [

10,

14,

18,

20].

7. Final Evaluation and Suggestion

In contrast to Bangladesh’s limited external investment, India’s ship recycling sector has undergone substantial modernization, primarily financed through over USD 100 million in international donor and public funds. According to industry sources, this capital infusion has facilitated the construction and equipping of approximately 120 “green” ship recycling yards along the coast of Alang and other locations, featuring modern infrastructure such as shore cranes, concrete hard-standing areas, and waste treatment units. Anam Chowdhury, President of the Bangladesh Marine Officers Association (BMOA), highlighted this disparity in an interview with the Business Standard, stating: “With over $100 million funding from international donors, India has developed 120 green yards on the coast of Alang in Gujarat to recycle ships following the HKC. In contrast, Bangladesh has developed only five green yards in the last 10 years, which are insufficient to compete with India. This means Bangladesh is likely to lose its top position this year”. This significant investment has accelerated India’s certification process, enabling it to establish 120 yards compliant with the Hong Kong Convention (HKC), according to BIMCO data, and reducing its dependence on foreign subsidies for basic yard upgrades. Similarly, Pakistan has recently initiated sizable domestic investments to modernize its ship recycling industry. In June 2025, the Pakistani government approved a fund of Rs 12 billion (~USD 42 million) to transform the Gadani ship-breaking yards into a “model green facility.”

Planned improvements include the installation of modern cranes, pollution control technologies, enhanced worker infrastructure, and the development of roads, hospitals, training centers, and waste treatment plants. Historically, Gadani was one of the world’s foremost destinations for end-of-life vessels, known for dismantling decommissioned ships and recycling valuable materials such as steel. While Pakistan’s investments remain modest by global standards, they represent a concrete commitment to upgrading its facilities and improving environmental management. In comparison, Bangladesh continues to compete for relatively limited foreign aid and credit, whereas both India and Pakistan have successfully mobilized considerably greater financial resources to enhance their ship-breaking sectors. This disparity poses significant challenges for Bangladesh’s ability to maintain its competitive position within the regional and global ship recycling markets. To remain in global competition, the rest of the local yards (around 25 yards) need to achieve the HKC certificate as soon as possible; otherwise, the nation will lose the race. However, the high cost of building green yards made local recycling owners still hesitant/timid. It would take at least Taka 200 to 300 million (around 2.5 million USD) to modernize a single ship recycling yard, and it would cost about Taka 12 billion (around 100 million USD) to upgrade the entire recycling industry/sector in order to have all the facilities (as per HKC) and stay competitive and resilient in business/sector globally.

Bangladesh’s ship recycling industry now faces severe competition from modernizing yards in India and Pakistan (after completion of their upgradation plan), especially as international rules tighten. Bangladesh ratified the Hong Kong Convention (HKC) in June 2023, but by Nov-2025, few yards (only 17) meet HKC standards. Latest industry data show that India has 120 HKC-certified/compliant yards, while Bangladesh has only 17 (soon to be 30) HKC-compliant yards. In practice, roughly 95% of India’s yards are HKC-certified versus only about 48% of Bangladesh’s (the remaining 52% are not fully compliant). This gap threatens Bangladesh’s market share, as until 2023, Bangladesh handled ~46% of global recycling tonnage, whereas India handled ~33%. The analysts warn that Bangladesh is potentially at risk and going to lose its position to Indian yards (where India has managed large donor-backed “green yards”), and surely, India is going to capture more business in the coming years. At the same time, Pakistan, which accounts for ~16.6% of global recycling share (in 2022), has only just ratified the HKC (December 2023) and is scrambling to upgrade Gadani. Pakistan is also going to catch up to the global race very soon. So, environmental compliance is a key challenge for Bangladesh. That is why local recycling yards of Bangladesh need to earn the HKC certificate within a short span of time and need to upgrade the remaining non-compliant yards, to remain competitive, or else EOL vessels will flow increasingly toward Indian recycling yards and modernizing Pakistani yards. Now, India already mandates ‘Ready for Recycling’ certificates and strict waste management under its 2019 ‘Recycling of Ships Act’, while Pakistan’s government has approved major investments to build a “model green” yard at Gadani. Actually, local recycling yards of Bangladesh and the nation as a whole have no alternative except a modernization and upgradation strategy and capital investment in this sector.

A digital twin framework for ship recycling yards could integrate AI and IoT to create a real-time virtual model of dismantling operations. Using sensor data (temperature, vibration, emissions) and machine learning, it would simulate optimal dismantling sequences, maximize material recovery, and minimize hazardous releases. This model could guide yard managers in predictive maintenance, waste tracking, and safety monitoring, supporting HKC compliance and sustainability.

7.1. Materials Science and Chemical Innovation in Ship Recycling

From a chemistry and materials science perspective, the main challenges lie in separating multi-layer composites, polymer–metal bonds, and hazardous additives used in advanced ship materials. Modern vessels incorporate fiber-reinforced plastics, epoxy resins, and electronic assemblies containing rare earth elements and toxic compounds, which resist conventional mechanical separation. However, opportunities exist in developing selective solvent systems, supercritical fluid extraction, and catalytic depolymerization to recover valuable metals and polymers safely. Advances in electrochemical and plasma-assisted separation could also enhance efficiency while minimizing waste and emissions.

To ensure transparency and effective environmental governance, the proposed National Recycling Information System (NRIS) should incorporate measurable Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). These include:

Hazardous Waste Management Efficiency (%): Ratio of properly treated hazardous waste to total waste generated.

Worker Safety Compliance Rate (%): Verified PPE usage and number of safety-compliant yards.

Emission and Discharge Levels: Monitoring of heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Hg) and hydrocarbons in soil, air, and water.

HKC Certification Progress (%): Percentage of certified or under-assessment yards.

Material Recovery Rate (%): Share of reusable materials (steel, copper, electronics) recovered per dismantled ship.

Training and Skill Development (hours/worker): Annual average safety and environmental training per worker.

Incident Frequency Rate: Number of recordable accidents per 100,000 work hours.

Implementing these KPIs would enable continuous performance assessment, data-driven policy refinement, and improved compliance across all ship recycling yards.

Occupational health and safety remain critical challenges in Bangladesh’s ship recycling sector. While some improvements have been observed following selective interventions, analysis of survey and interview data highlights persistent gaps.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Only 42% of workers reported consistent use of PPE such as helmets, gloves, and safety shoes. The remainder either used PPE sporadically or not at all, exposing them to potential injuries and chemical hazards.

Safety Training: Only 38% of yards reported providing formal safety training within the past year. A significant portion of workers lacked guidance on handling hazardous materials such as asbestos, PCBs, and TBT-containing paints.

Exposure to Hazardous Conditions: 65% of respondents indicated regular exposure to dust, fumes, and toxic residues during cutting and dismantling operations. These exposures are particularly high in yards without wet-cutting or dust-suppression measures.

Emergency Preparedness: 72% of workers reported inadequate or absent emergency response procedures, including fire-fighting, first aid, and evacuation protocols.

Hazardous Waste Management: While some yards have begun segregating hazardous materials, most still dispose of contaminants such as asbestos insulation, PCBs, and heavy-metal-laden paints directly into the environment, increasing both occupational and ecological risks.

These data substantiate the claim of widespread deficiencies in workplace safety. Survey data revealed that 68% of workers lacked formal safety training, 54% reported inadequate protective gear, and nearly 40% experienced minor injuries within six months, confirming the widespread deficiencies in workplace safety. These findings directly align with field observations of inconsistent compliance and limited supervision in most yards.

They highlight the urgent need for regulatory enforcement, systematic training programs, PPE provision, and infrastructural upgrades to reduce health risks and align with international safety standards, such as those outlined in the Hong Kong Convention (HKC).

Applying Green Chemistry in Bangladesh’s ship recycling means preventing waste at the source rather than treating it later. This can be done by using non-toxic cleaning agents, adopting low-emission cutting methods, ensuring early segregation of oils and paints, and creating closed-loop recovery for lubricants. Such measures reduce hazardous waste generation and align the industry with sustainable, circular economy practices.

7.2. Expected Benefits

Substantial reduction in hazardous waste generation and environmental contamination;

Improved occupational health and safety for shipyard workers;

Enhanced recovery of valuable materials, supporting circular economy goals;

Stronger compliance with international environmental and labor standards, including HKC guidelines.

Bangladesh’s current management of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) from ship recycling—such as PCBs and TBT—remains only partially compliant with the Stockholm Convention. Although national plans exist, inadequate segregation, monitoring, and destruction facilities lead to unsafe disposal. Strengthening hazardous waste controls, POP destruction capacity, and routine monitoring is essential for full compliance.

A comparative life-cycle assessment (LCA) can model the net environmental benefit of ship recycling in Bangladesh versus an EU-compliant dry dock.

The functional unit (e.g., 1000 t of ship material) considers recovered steel, avoided virgin ore mining, energy use, emissions, and pollution.

7.3. Key Formula

Net Benefit = Avoided Impacts (from recycled steel) − (Process + Pollution + Transport Impacts).

Critical parameters:

Steel recovery efficiency;

Hazardous waste containment;

Energy intensity and grid emissions;

Local pollution and remediation needs;

Transport distance and mode.

7.4. Result

Bangladesh’s beaching method offers higher recovery and lower cost but higher toxicity risks; EU dry docks emit more CO2 but ensure safer waste control. The “greener” option depends mainly on pollution control efficiency and recovery purity.

Core Elements of Chemistry-Based Guidelines for Hazardous Ship Wastes (Asbestos, PCBs, TBT):

Identification & Classification: Specify chemical composition, toxicity, and threshold levels.

Segregation & Storage: Use sealed, labeled containers with appropriate environmental controls.

Safe Handling: PPE, wetting or containment measures, and chemical-specific procedures.

Treatment & Disposal: Approved destruction methods (e.g., incineration for PCBs, encapsulation for asbestos, stabilization for TBT).

Monitoring & Verification: Regular chemical assays, record-keeping, and compliance reporting.

Emergency Response: Procedures for spills, exposure, or accidental releases.

Based on stakeholder analysis, a mentorship and cluster-based collaboration model is most effective. In this approach:

Certified “Lead Yards” serve as knowledge hubs, demonstrating HKC-compliant operations, safety protocols, and green technology adoption.

Smaller or non-compliant yards are paired with lead yards for structured on-site training, workshops, and joint pilot projects.

Digital platforms and mobile apps complement in-person mentorship by providing SOPs, hazard databases, and monitoring dashboards.

Regulatory incentives (e.g., preferential access to finance, certifications, or scrap supply) motivate the adoption of best practices.

This model leverages hands-on learning, peer influence, and technology-enabled guidance to accelerate compliance and modernization across the sector.

7.5. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) in Shipping

Shipowners fund and oversee the end-of-life management of their vessels. Contributions support HKC-compliant yards in Bangladesh, covering hazardous waste handling, green infrastructure, and worker training. EPR ensures safe delivery, material tracking, and compliance incentives, aligning financial responsibility with environmental performance.

Drawing on recent research, effective modernization of Bangladesh’s ship recycling sector requires both strategic knowledge transfer and carefully structured financial mechanisms. The authors of highlight that cross-border collaborations, when highly concentrated among a few foreign actors, can hinder local knowledge creation due to long transmission paths and potential information hoarding. To mitigate this, the proposed mentorship-cluster model ensures multiple linkages among certified “lead” yards, local non-compliant yards, technical institutes, and regulatory bodies, facilitating horizontal diffusion of best practices, mechanization techniques, and environmental compliance procedures. This networked approach strengthens domestic absorptive capacity while preserving the benefits of international expertise.

Empirical evidence on green credit indicates that preferential financing can expand project scale but may reduce efficiency if not paired with innovation incentives and process monitoring. Accordingly, the proposed financial framework for yard modernization combines blended financing (grants plus preferential loans) with performance-based disbursement triggers linked to metrics such as material recovery efficiency, hazardous waste reduction, and worker safety compliance. Technical assistance for innovation—including mechanized cutting, digital twins, and IoT monitoring—is integrated to ensure that scale-up does not compromise process efficiency or environmental outcomes.

Together, these insights inform a dual strategy: structured cross-border knowledge networks for effective skill and technology transfer, and a green-finance model tied to innovation and performance, ensuring sustainable, HKC-compliant modernization across Bangladesh’s ship recycling sector.