Mapping the Evidence on Care Home Decarbonisation: A Scoping Review Revealing Fragmented Progress and Key Implementation Gaps

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Types of Sources

Population

Concept

Context

2.3. Search Strategy

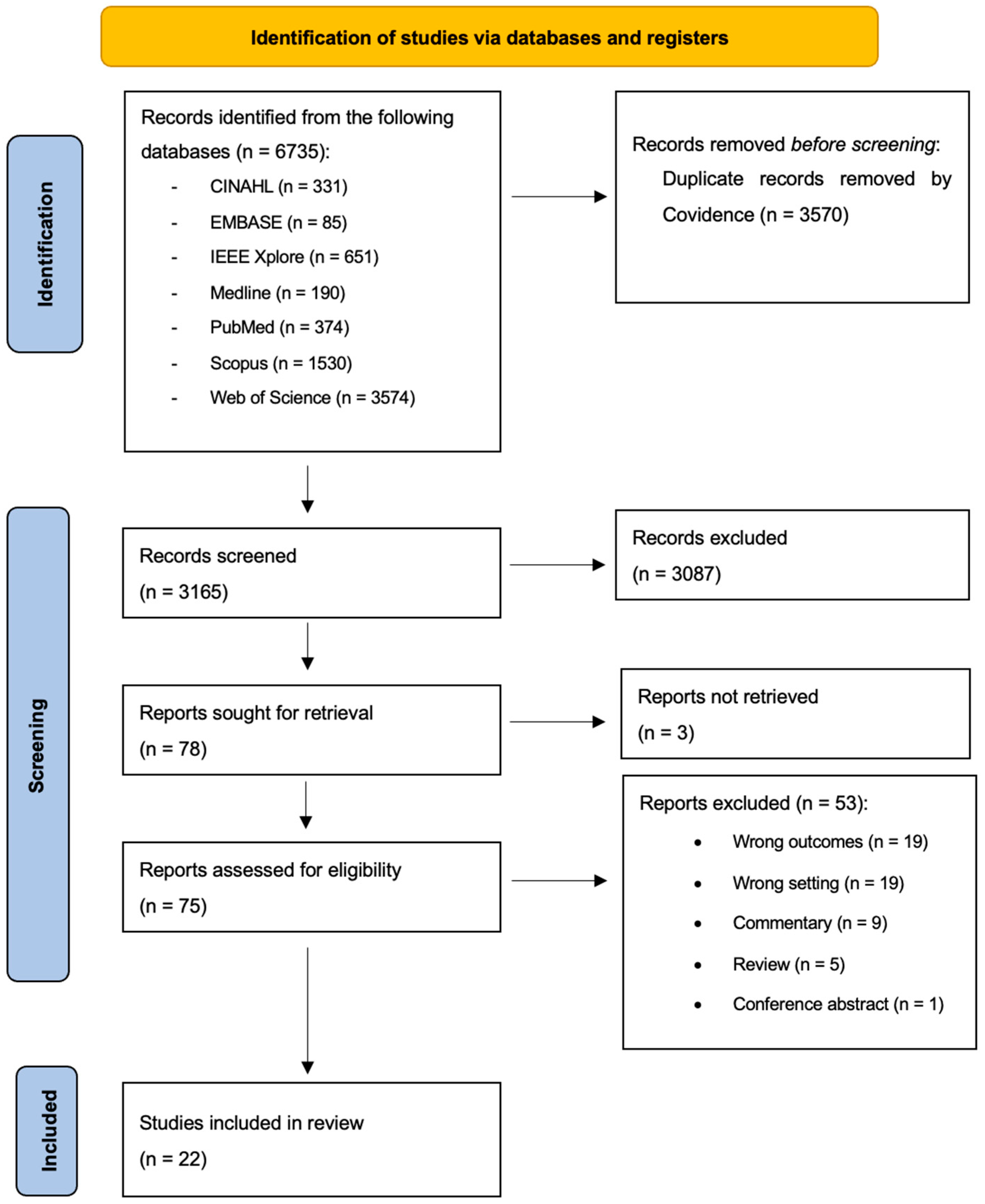

2.4. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.5. Data Charting

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Greenhouse Gas Emissions

3.2.1. Scope 1 Emissions

3.2.2. Scope 2 Emissions

3.2.3. Scope 3 Emissions

3.3. Decarbonisation Strategies

3.3.1. Renovations and Retrofits

3.3.2. Food Procurement, Menu and Diet Recommendations

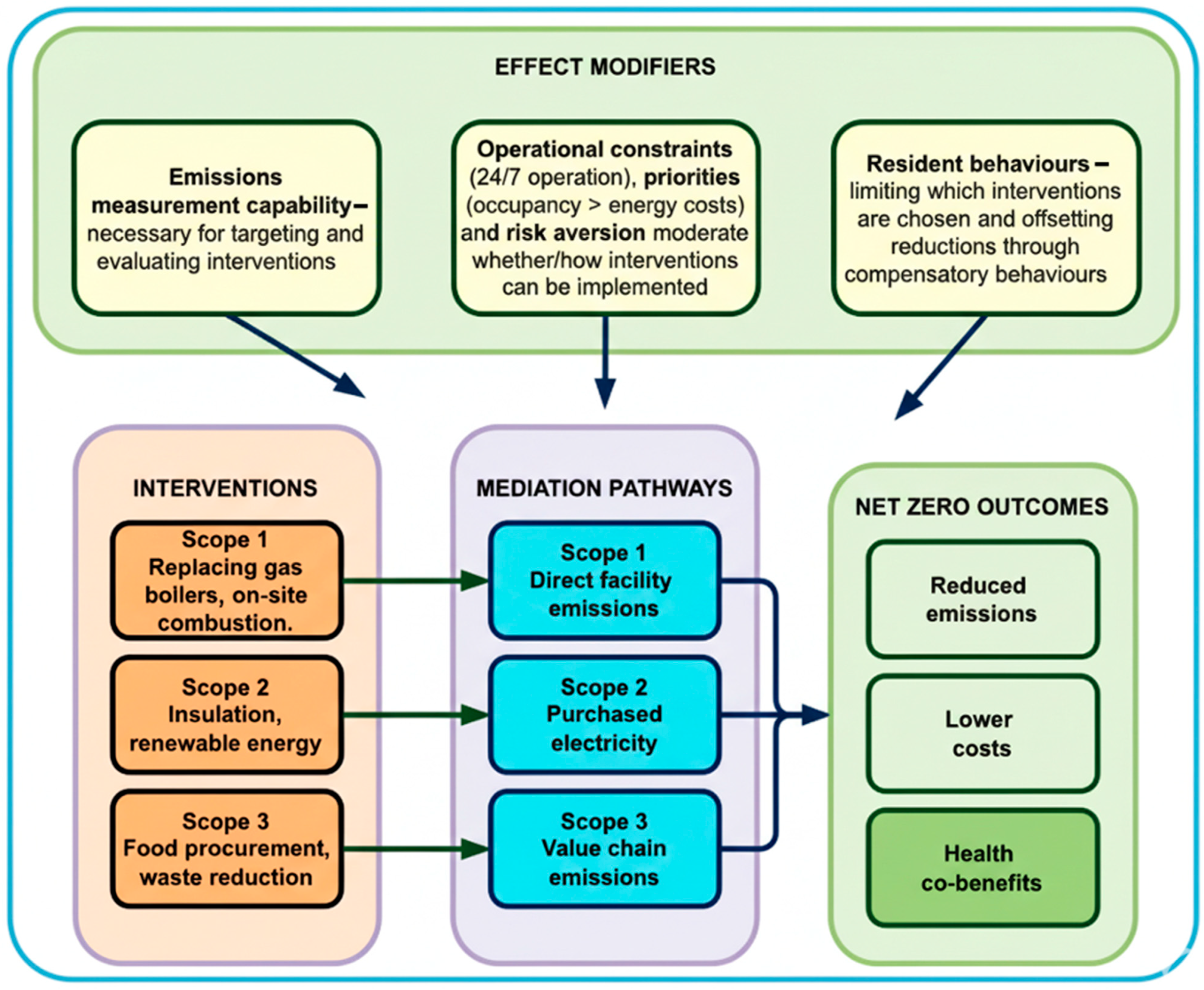

3.4. Proposed Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| ATACH | Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| RACFS | Residential Aged Care Facilities |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| CQC | Care Quality Commission |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| PCC | Population, Concept, and Context |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

References

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Climate Change. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Romanello, M.; Walawender, M.; Hsu, S.C.; Moskeland, A.; Palmeiro-Silva, Y.; Scamman, D.; Ali, Z.; Ameli, N.; Angelova, D.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; et al. The 2024 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Facing record-breaking threats from delayed action. Lancet 2024, 404, 1847–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirow, J.; Venne, J.; Brand, A. Green Health: How to Decarbonise Global Healthcare Systems. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2024, 7, 28. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s42055-024-00098-3 (accessed on 3 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pichler, P.-P.; Jaccard, I.S.; Weisz, U.; Weisz, H. International comparison of health care carbon footprints. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 64004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Miller, W.; Chiou, J.; Zedan, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Ding, Y. Aged Care Energy Use and Peak Demand Change in the COVID-19 Year: Empirical Evidence from Australia. Buildings 2021, 11, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Miller, W.; Crompton, G.; Zedan, S. Has COVID-19 lockdown impacted on aged care energy use and demand? Energy Build. 2021, 235, 110759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzoli, V.; Norton, L.S.; Sarrica, M. Mapping the meanings of decarbonisation: A systematic review of studies in the social sciences using lexicometric analysis. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2021, 3, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, I.; Barwińska-Małajowicz, A.; Wolska, G.; Walawender, P.; Hydzik, P. Is the European Union Making Progress on Energy Decarbonisation While Moving towards Sustainable Development? Energies 2021, 14, 3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Campagnolo, L.; Boitier, B.; Nikas, A.; Koasidis, K.; Gambhir, A.; Gonzalez-Eguino, M.; Perdana, S.; Van de Ven, D.-J.; Chiodi, A.; et al. The impacts of decarbonization pathways on Sustainable Development Goals in the European Union. Commun Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Blom, I.M.; Rasheed, F.N.; Singh, H.; Eckelman, M.J.; Dhimal, M.; Hensher, M.; Guinto, R.R.; McGushin, A.; Ning, X.; Prabhakaran, P.; et al. Evaluating progress and accountability for achieving COP26 Health Programme international ambitions for sustainable, low-carbon, resilient health-care systems. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e778–e789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Alliance for Action on Climate Change and Health (ATACH). Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/alliance-for-transformative-action-on-climate-and-health (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Health Care Without Harm. Global Road Map for Health Care Decarbonization. Health Care Climate Action; 2021. Available online: https://healthcareclimateaction.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/Health%20Care%20Without%20Harm_Health%20Care%20Decarbonization_Road%20Map.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Braithwaite, J.; Smith, C.L.; Leask, E.; Wijekulasuriya, S.; Brooke-Cowden, K.; Fisher, G.; Patel, R.; Pagano, L.; Rahimi-Ardabili, H.; Spanos, S.; et al. Strategies and tactics to reduce the impact of healthcare on climate change: Systematic review. BMJ 2024, 387, e081284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickles, K.; Haas, R.; Guppy, M.; O’Connor, D.A.; Pathirana, T.; Barratt, A.; Buchbinder, R. Clinician and health service interventions to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions generated by healthcare: A systematic review. BMJ EBM 2024, 29, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, P.; Armstrong, F.; Karliner, J. Decarbonising the Healthcare Sector: A Roadmap for G20 Countries. T20 Policy Brief. 2023. Available online: https://t20ind.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/T20_PolicyBrief_TF3_DecarbonisingHealthcare.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Leal Filho, W.; Luetz, J.M.; Thanekar, U.D.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Forrester, M. Climate-friendly healthcare: Reducing the impacts of the healthcare sector on the world’s climate. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN) Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division. World Population Prospects. 2024. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Sanford, A.M.; Orrell, M.; Tolson, D.; Abbatecola, A.M.; Arai, H.; Bauer, J.M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dong, B.; Ga, H.; Goel, A.; et al. An International Definition for “Nursing Home”. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajat, S.; Vardoulakis, S.; Heaviside, C.; Eggen, B. Climate change effects on human health: Projections of temperature-related mortality for the UK during the 2020s, 2050s and 2080s. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oven, K.J.; Curtis, S.E.; Reaney, S.; Riva, M.; Stewart, M.G.; Ohlemüller, R.; Dunn, C.E.; Nodwell, S.; Dominelli, L.; Holden, R. Climate change and health and social care: Defining future hazard, vulnerability and risk for infrastructure systems supporting older people’s health care in England. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 33, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Care Quality Commission (CQC). Single Assessment Framework: Environmental Sustainability—Sustainable Development. 2025. Available online: https://www.cqc.org.uk/guidance-regulation/providers/assessment/single-assessment-framework/well-led/environmental-sustainability (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Ontario Ministry of Energy. Report Energy and Water Use in Large Buildings|Ontario.ca. 2017. Available online: http://www.ontario.ca/page/report-energy-water-use-large-buildings (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- New York City—Buildings. LL97 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction—Buildings. 2019. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/site/buildings/codes/ll97-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reductions.page (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Washington State Department of Commerce. Clean Buildings Performance Standard (CBPS). Washington State Department of Commerce. 2024. Available online: https://www.commerce.wa.gov/cbps/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Hough, E.; Tanugi-Carresse, A.C. Supporting Decarbonization of Health Systems—A Review of International Policy and Practice on Health Care and Climate Change. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beevers, S.; Assareh, N.; Beddows, A.; Stewart, G.; Holland, M.; Fecht, D.; Liu, Y.; Goodman, A.; Walton, H.; Brand, C.; et al. Climate change policies reduce air pollution and increase physical activity: Benefits, costs, inequalities, and indoor exposures. Environ. Int. 2025, 195, 109164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Building Climate-Resilient Health Systems. Climate Change and Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/climate-change-and-health/country-support/building-climate-resilient-health-systems (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Greenhouse Gas Protocol. The GHG Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (Revised Edition). 2004. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/corporate-standard (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Or, Z.; Seppänen, A.-V. The role of the health sector in tackling climate change: A narrative review. Health Policy 2024, 143, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Jiménez, L.; Romero-Martin, M.; Spruell, T.; Steley, Z.; Gomez-Salgado, J. The carbon footprint of healthcare settings: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 2830–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duindam, D. Transitioning to Sustainable Healthcare: Decarbonising Healthcare Clinics, a Literature Review. Challenges 2022, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.R.; Karaba, F.; Geddes, O.; Bickerton, A.; Atherton, H.; Dahlmann, F.; Eccles, A.; Gregg, M.; Spencer, R.; Twohig, H.; et al. Implementation of decarbonisation actions in general practice: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e091404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). Appendix 11.1 JBI template source of evidence details, characteristics and results extraction instrument—JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis—JBI Global Wiki. 2022. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687579/Appendix+11.1+JBI+template+source+of+evidence+details%2C+characteristics+and+results+extraction+instrument (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, É.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Wrapson, W.; Henshaw, V.; Guy, S. Low carbon heating and older adults: Comfort, cosiness and glow. Build. Res. Inf. 2014, 42, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neven, L.; Walker, G.; Brown, S. Sustainable thermal technologies and care homes: Productive alignment or risky investment? Energy Policy 2015, 84, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balo, F.; Ulutaş, A.; Stević, Ž.; Boydak, H.; Zavadskas, E.K. Hybrid Revit and a new MCDM approach of energy effective nursing-home designed by natural stone and green insulation materials. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2025, 31, 318–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beermann, M.; Sauper, E. Monitoring results of innovative energy-efficient buildings in Austria. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 323, 12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, L.; De Santis, A.; Di Sero, A.; Franco, N. Concurrent economic and environmental impacts of food consumption: Are low emissions diets affordable? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, A.; Opizzi, A.; Binala, J.G.; Cortese, L.; Barone-Adesi, F.; Panella, M. Evaluation of the Climate Impact and Nutritional Quality of Menus in an Italian Long-Term Care Facility. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, S.; Smith, J.; Hogg, J.; Walton-Hespe, J.; Gardner-Marlin, J. Gathering the evidence: Health and aged care carbon inventory study. Aust. Health Rev. 2023, 47, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, B.; Fong, A.; Hong, G.; Tsang, K.F. Optimization of Power Usage in a Smart Nursing Home Environment. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Fernández, I. Sustainable Renovation of Nursing Homes in Norway. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, S.S. Investigation on the Impact of Passive Design Strategies on Care Home Energy Efficiency in the UK. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Simulation in Architecture and Urban Design (SimAUD2020), Online, 25–27 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaoka, K.; Inagata, T.; Matsui, N.; Jiyoung, C.; Kurokawa, F.; Mizuno, Y. Estimated Energy Balance for Shuttle Service of Nursing Home-Collaborated Hospital Assuming EVs. In Proceedings of the 2024 13th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Nagasaki, Japan, 9–13 November 2024; pp. 1386–1390. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10815560/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Kuzgunkaya, E.H. Energy performance assessment in terms of primary energy and exergy analyses of the nursing home and rehabilitation center. Energy Environ. 2019, 30, 1506–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, A.D.; Nordman, M.; Christensen, L.M.; Beck, A.M.; Trolle, E. Guidance for Healthy and More Climate-Friendly Diets in Nursing Homes—Scenario Analysis Based on a Municipality’s Food Procurement. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassen, A.D.; Nordman, M.; Christensen, L.M.; Trolle, E. Providing healthy and climate-friendly public meals to senior citizens: A midway evaluation of a municipality’s food strategy. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Miller, W.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Zedan, S.; Yang, Y.; Chiou, J.; Mantis, J.; O’Sullivan, M. A Fairer Renewable Energy Policy for Aged Care Communities: Data Driven Insights across Climate Zones. Buildings 2022, 12, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-H.; Liao, M.-C.; Lin, W.-C.; Sung, W.-P. Developing new heat pump system to improve indoor living space in senior long-term care house. J. Meas. Eng. 2019, 7, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, L.M.; Schlenger, L.; Gabrysch, S.; Lambrecht, N.J. Dietary quality and environmental footprint of health-care foodservice: A quantitative analysis using dietary indices and lifecycle assessment data. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, 101274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Specian, M.; Hong, T. Nexus of thermal resilience and energy efficiency in buildings: A case study of a nursing home. Build. Environ. 2020, 177, 106842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teni, M.; Čulo, K.; Krstić, H. Renovation of Public Buildings towards nZEB: A Case Study of a Nursing Home. Buildings 2019, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergés, R.; Gaspar, K.; Forcada, N. Assessment of the energy implications adopting adaptive thermal comfort models during the cooling season: A case study for Mediterranean nursing homes. Energy Build. 2023, 299, 113598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergés, R.; Gaspar, K.; Forcada, N. Predictive modelling of cooling consumption in nursing homes using artificial neural networks: Implications for energy efficiency and thermal comfort. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 2356–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Song, D.; Zhang, C. Visualization analysis and optimization strategy of thermal landscape in retrofitted elderly care buildings: A case study in Shanghai. Indoor Built Environ. 2025, 34, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbendorff, A.; Sonestedt, E.; Ramne, S.; Drake, I.; Hallström, E.; Ericson, U. Development of an EAT-Lancet index and its relation to mortality in a Swedish population. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams-White, M.M.; Pannucci, T.E.; Lerman, J.L.; Herrick, K.A.; Zimmer, M.; Mathieu, K.M.; Stoody, E.E.; Reedy, J. Healthy Eating Index-2020: Review and Update Process to Reflect the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 123, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, V.S.; Gerwig, K.; Hough, E.; Mate, K.; Biggio, R.; Kaplan, R.S. Decarbonizing Health Care: Engaging Leaders in Change. NEJM Catalyst. 2023, 4. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ac8b36dec4eb72f79b3127b/t/644029d6ca69d14bc542a047/1681926615317/CAT.22.0433 (accessed on 29 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mandouri, J.; Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Jabbar, R.; Al-Quradaghi, S.; Al-Thani, S.; Kazançoğlu, Y. Carbon footprint of food production: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulston, M.; Thompson, C.; Pelly, F.; Cave, D. Food Waste in Residential Aged Care: A Scoping Review. Nutr. Diet. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, A.; Grenfell, P.; Murage, P. A Planetary Health Perspective to Decarbonising Public Hospitals in Ireland: A Health Policy Report. Eur. J. Environ. Public Health 2021, 5, em0067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.; Smith, C.L.; Pagano, L.; Spanos, S.; Zurynski, Y.; Braithwaite, J. Leveraging implementation science to solve the big problems: A scoping review of health system preparations for the effects of pandemics and climate change. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e326–e336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, D.A.M.; Saikia, P.; De la Cruz-Loredo, I.; Zhou, Y.; Ugalde-Loo, C.E.; Bastida, H.; Abeysekera, M. A framework for the assessment of optimal and cost-effective energy decarbonisation pathways of a UK-based healthcare facility1. Appl. Energy 2023, 352, 121877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutet, L.; Bernard, P.; Green, R.; Milner, J.; Haines, A.; Slama, R.; Temime, L.; Jean, K. The public health co-benefits of strategies consistent with net-zero emissions: A systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e145–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, H.; Dajnak, D.; Holland, M.; Evangelopoulos, D.; Wood, D.; Brand, C.; Assareh, N.; Stewart, G.; Beddows, A.; Lee, S.Y.; et al. Health and associated economic benefits of reduced air pollution and increased physical activity from climate change policies in the UK. Environ. Int. 2025, 196, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata, T.M.; Felgueiras, F.; Martins, A.A.; Monteiro, H.; Ferraz, M.P.; Oliveira, G.M.; Gabriel, M.F.; Silva, G.V. Indoor Air Quality in Elderly Centers: Pollutants Emission and Health Effects. Environments 2022, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Yu, D.S.F.; Tan, W.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Tao, Y. Crafting Sustainable Healthcare Environments Using Green Building Ratings for Aging Societies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-W.; Kumar, P.; Cao, S.-J. Implementation of green infrastructure for improving the building environment of elderly care centres. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 54, 104682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health Co-Benefits of Climate Action. Climate Change and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/climate-change-and-health/capacity-building/toolkit-on-climate-change-and-health/cobenefits (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Ibbetson, A.; Milojevic, A.; Mavrogianni, A.; Oikonomou, E.; Jain, N.; Tsoulou, I.; Petrou, G.; Gupta, R.; Davies, M.; Wilkinson, P. Mortality benefit of building adaptations to protect care home residents against heat risks in the context of uncertainty over loss of life expectancy from heat. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 32, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.; Brown, S.; Neven, L. Thermal comfort in care homes: Vulnerability, responsibility and ‘thermal care’. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 44, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Childs, C.; Peng, C.; Robinson, D. Thermal comfort modelling of older people living in care homes: An evaluation of heat balance, adaptive comfort, and thermographic methods. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, A.; Blashki, G.; Bowen, K.J.; Karoly, D.J.; Wiseman, J. Health co-benefits and the development of climate change mitigation policies in the European Union. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, R.; Balmer, D.; Robinson, J.; Gott, M.; Boyd, M. The Effect of Residential Aged Care Size, Ownership Model, and Multichain Affiliation on Resident Comfort and Symptom Management at the End of Life. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 57, 545–555.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J. The problems of social care in English nursing and residential homes for older people and the role of state regulation. J. Soc. Welf. Fam. Law 2022, 44, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.R.; Sah, R.K.; Simkhada, B.; Darwin, Z. Potentials and challenges of using co-design in health services research in low- and middle-income countries. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2023, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overton, C.; Tarrant, C.; Creese, J.; Armstrong, N. Role of coproduction in the sustainability of innovations in applied health and social care research: A scoping review. BMJ Open Qual. 2024, 13, e002796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampard, P.; Premji, S.; Adamson, J.; Bojke, L.; Glerum-Brooks, K.; Golder, S.; Graham, H.; Jankovic, D.; Zeuner, D. Priorities for research to support local authority action on health and climate change: A study in England. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scope | Study | Decarbonisation Strategy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scope 1 | Kumaoka et al., 2024 [51] | Replacement of shuttle buses between care home and hospital with electric vehicles charged via onsite photovoltaic systems. | Statistical modelling revealed the elimination of direct vehicle fuel emissions and a 10% reduction in total power demand during the first six months. |

| Scope 2 | Balo et al., 2025 [43] | Retrofitting with sustainable material choices (e.g., natural stone, natural insulation materials, roof systems, green wall facades). | Modelling revealed up to 31.3% reductions in energy consumption with the use of cellulose fibre insulation and a green roof system. |

| Beerman & Sauper et al., 2019 [44] | HVAC concept, district heating, electric boiler in warmer months, ventilation supported by underground collectors, moderate insulation rating. | Heating energy consumption > 50% lower than empirical literature values per care place. | |

| Fong et al., 2023 [48] | Smart technology: wireless sensing networks, smart power metres | 10% reduction in energy consumption. | |

| González Fernández, 2023 [49] | Renovations, including upgraded insulation and windows. | Life cycle analysis suggested a 50% reduction in net energy use. | |

| Hou, 2020 [50] | Passive design strategies: improving window U-values, reducing infiltration rates, and optimising the window-to-wall ratio. | Statistical modelling revealed a 28% reduction in overall annual energy use, a 35.2% reduction in heating demand, and the elimination of cooling demand. | |

| Liu et al., 2022 [55] | Small-scale renewable target on a per-bed basis compared to a static limit for each site. | A 5 kWp/bed limit could help Australian aged care communities produce 349% more renewable energy and reduce 670,000 tonnes of emissions than the 100 kWp per community scenario. | |

| Lu et al., 2019 [56] | Heat pump system with an integrated cooling system. | Reduced electricity consumption by 67.35%. | |

| Sun et al., 2020 [58] | Passive and active energy efficiency measures, e.g., reducing lighting and plug loads, adding insulation, reducing air infiltration, and cool roofs. | Energy savings are highly dependent on climate zone; often, energy savings and thermal resilience do not align. | |

| Teni et al., 2019 [59] | Retrofit: thermal insulation of walls, floors and ceilings, upgraded windows, thermal solar systems and condensing boilers, and improved cooling and ventilation. | Reduced energy needs by 81–89%. | |

| Vergés et al., 2023 [60] | Adaptive consumption models, including dynamic adjustment of HVAC temperature. | Average energy savings of up to 9.9% due to a reduction in cooling demand. | |

| Vergés et al., 2024 [61] | Prediction and optimisation model for cooling consumption. | Tailored models resulted in up to 23.4% in energy savings. | |

| Zhou et al., 2024 [62] | Retrofit of an activity space with a glass curtain wall. | Modelling highlighted that the addition of external shading could decrease cooling energy consumption by 26.8%. | |

| Scope 3 | Benvenuti et al., 2019 [45] | Menu planning. | Small cost increases could achieve substantial emissions reductions: 1% cost increase led to 12% greenhouse gas emissions (achieved via limiting animal-based foods). |

| Conti et al., 2024 [46] | Menu planning. | Increased adherence to the planetary health diet and a higher Modified-EAT-Lancet Diet Score are associated with lower greenhouse gas emissions. | |

| Lassen et al., 2021 [53] | Menu planning. | A 22% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions via a reduction in meat and dairy products, more plant-based food, and more climate-friendly fats and cereals. | |

| Lassen et al., 2025 [54] | Menu planning. | A 10–30% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions via updated menu guidelines, recipe databases, and tailored staff training. | |

| Pörtner et al., 2025 [57] | Menu planning. | Animal-sourced foods are responsible for around 75% of food-related environmental impact, with meat accounting for 38% of greenhouse gas emissions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anderson, T.; Craig, S.; Mitchell, G.; Hind, D. Mapping the Evidence on Care Home Decarbonisation: A Scoping Review Revealing Fragmented Progress and Key Implementation Gaps. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10946. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410946

Anderson T, Craig S, Mitchell G, Hind D. Mapping the Evidence on Care Home Decarbonisation: A Scoping Review Revealing Fragmented Progress and Key Implementation Gaps. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10946. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410946

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnderson, Tara, Stephanie Craig, Gary Mitchell, and Daniel Hind. 2025. "Mapping the Evidence on Care Home Decarbonisation: A Scoping Review Revealing Fragmented Progress and Key Implementation Gaps" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10946. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410946

APA StyleAnderson, T., Craig, S., Mitchell, G., & Hind, D. (2025). Mapping the Evidence on Care Home Decarbonisation: A Scoping Review Revealing Fragmented Progress and Key Implementation Gaps. Sustainability, 17(24), 10946. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410946