A Novel Dual-Function Red Mud Granule Mediated the Fate of Phosphorus in Agricultural Soils: Pollution Mitigation and Resource Recycling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of RMG

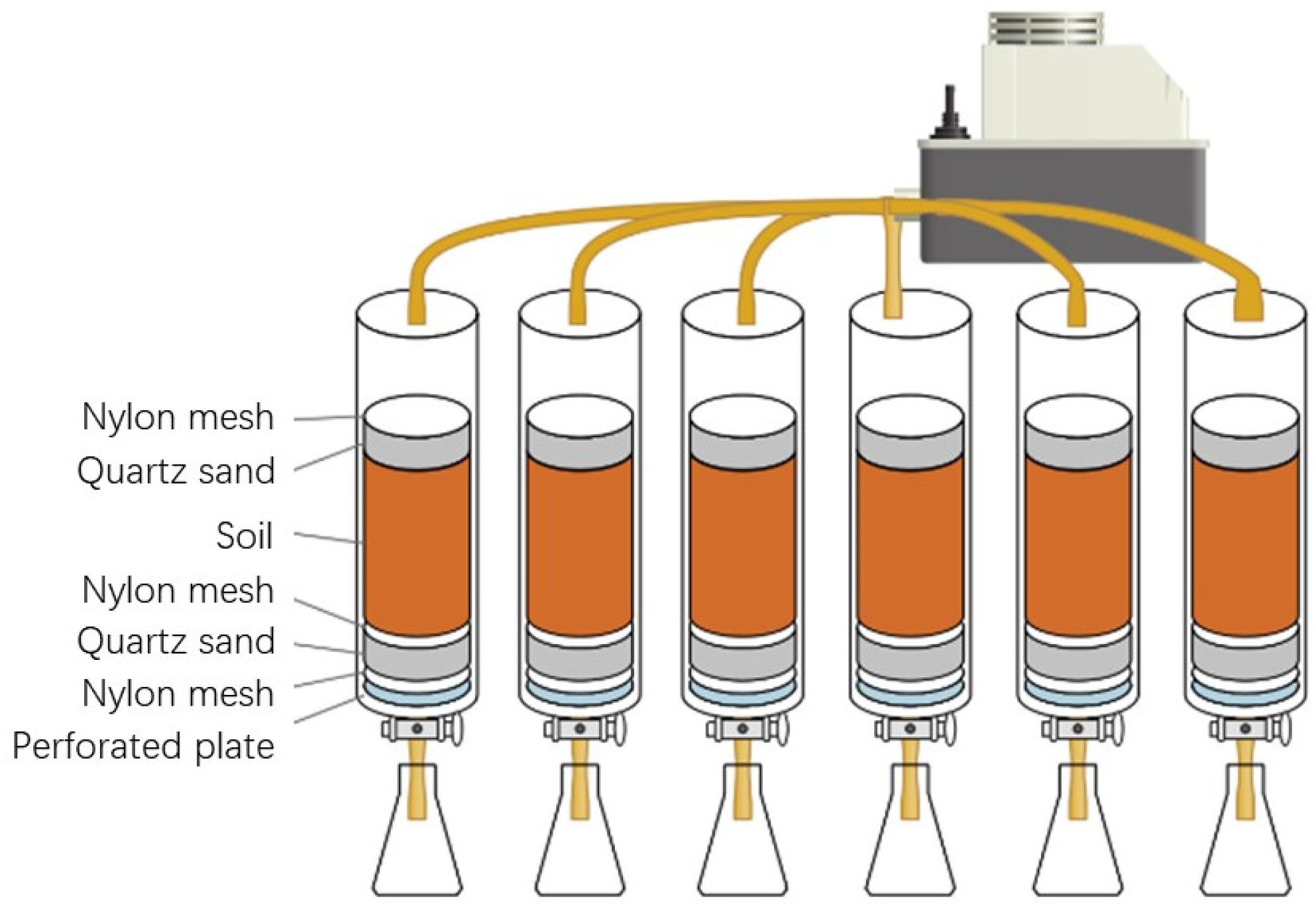

2.2. Dynamic Leaching Experiment

2.3. Phosphorus Releasing Experiment

2.4. Determination Methods

2.5. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

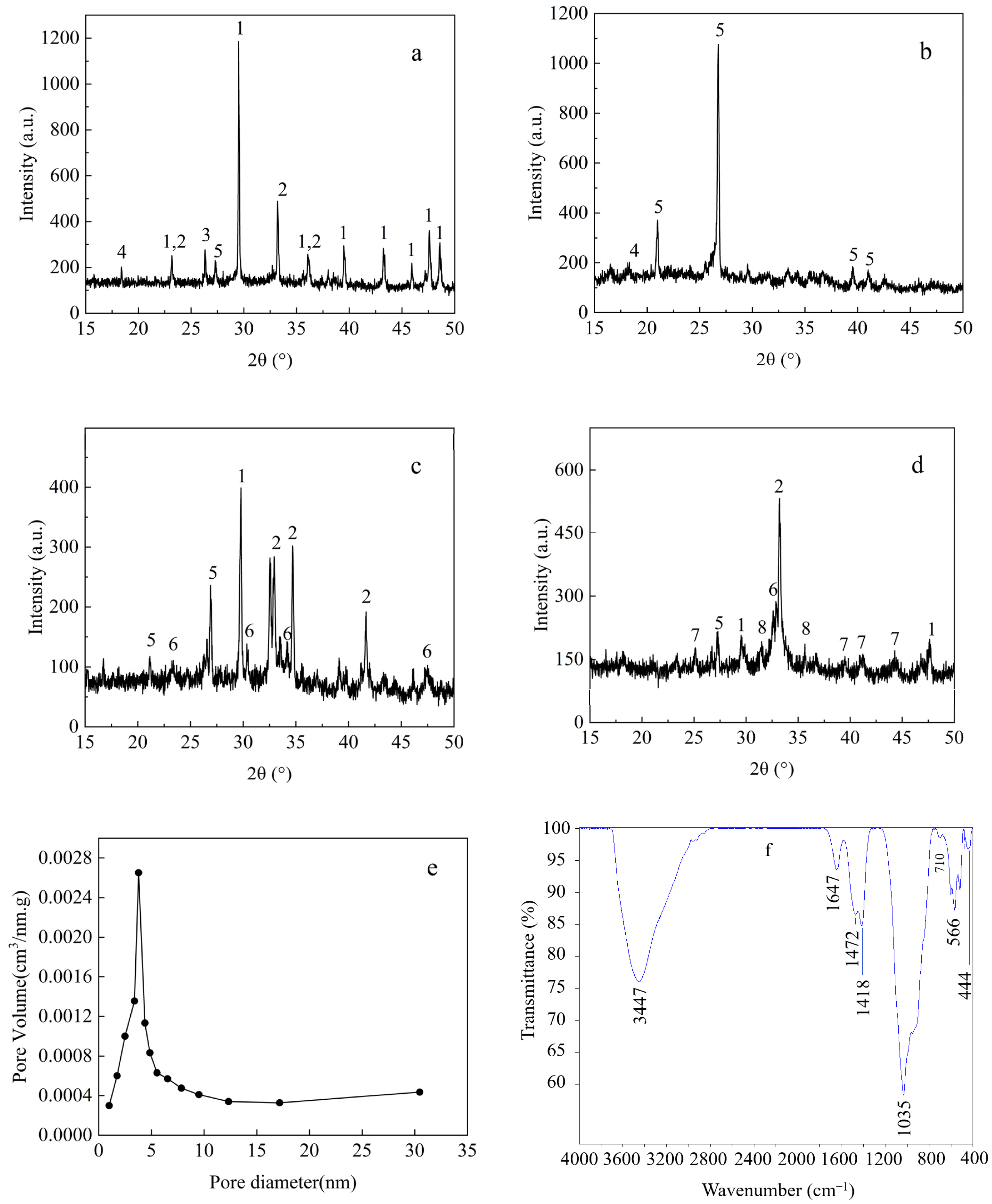

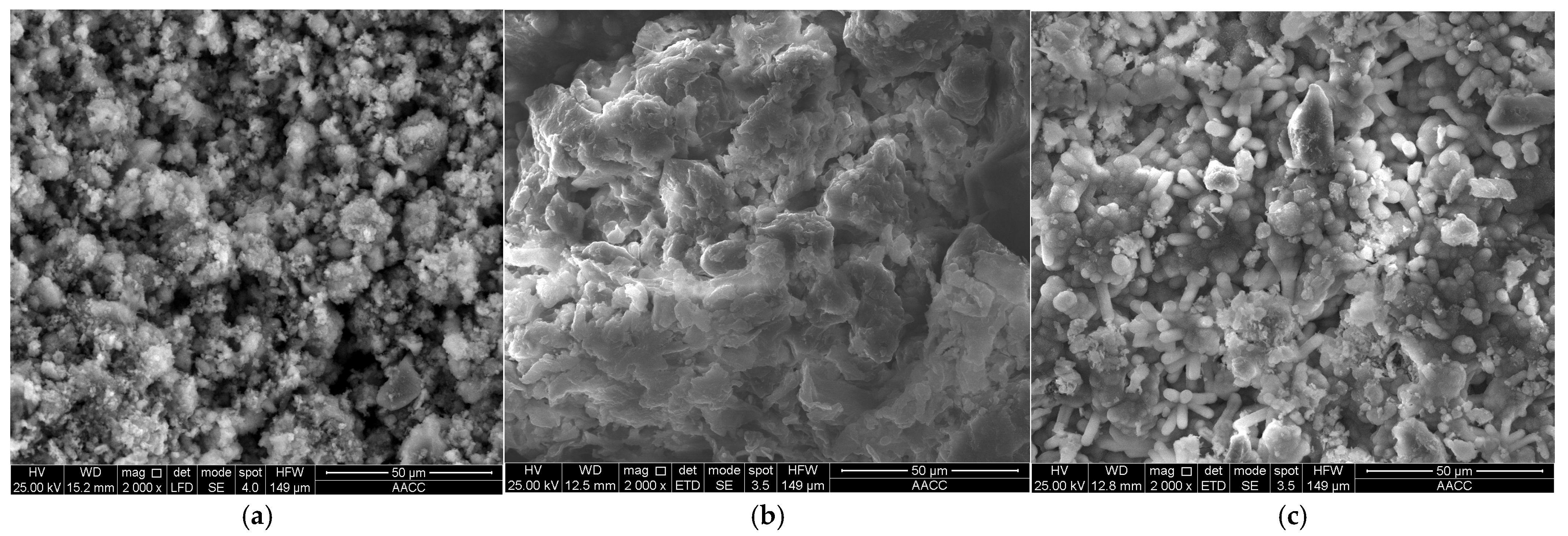

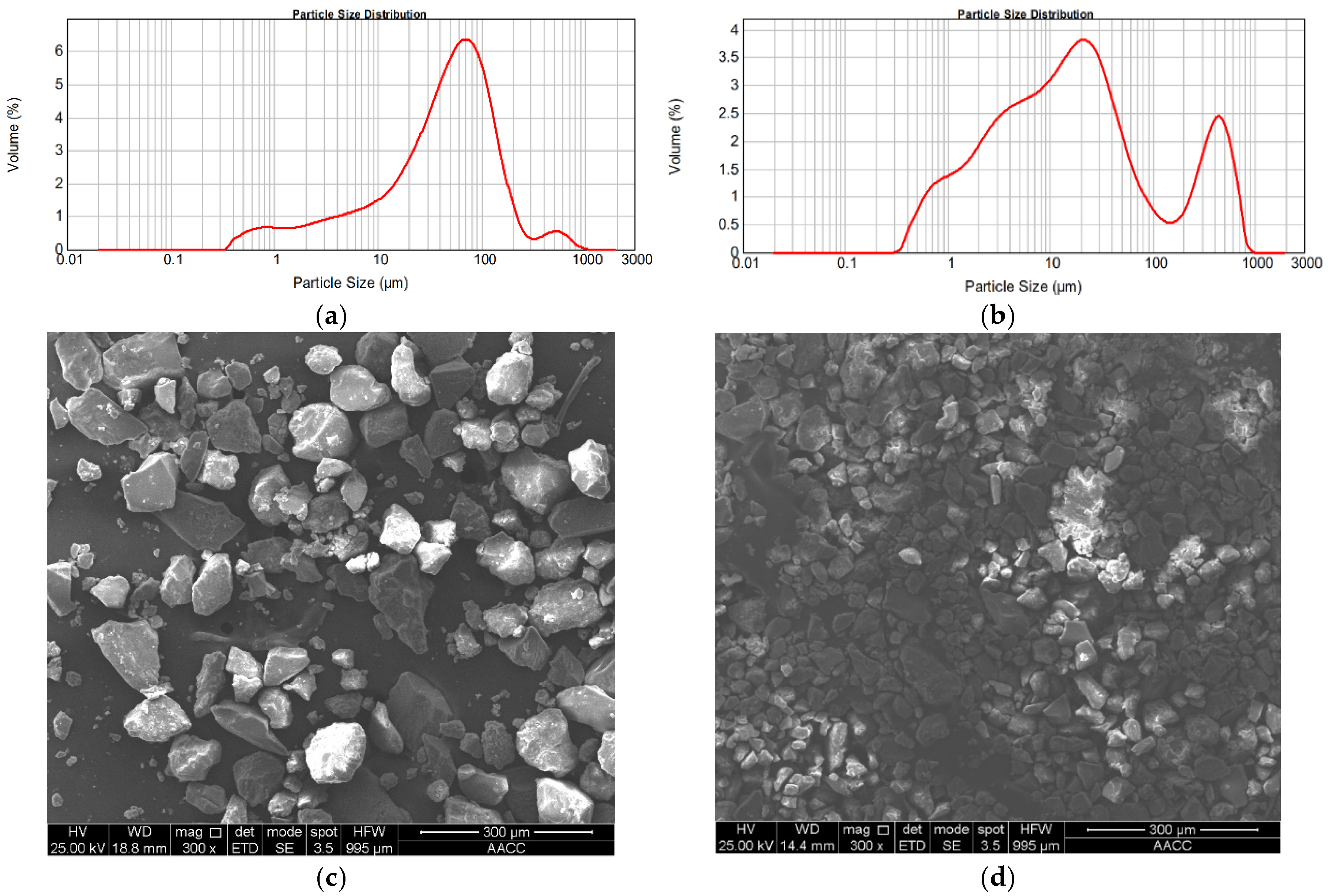

3.1. Characterization of RMG

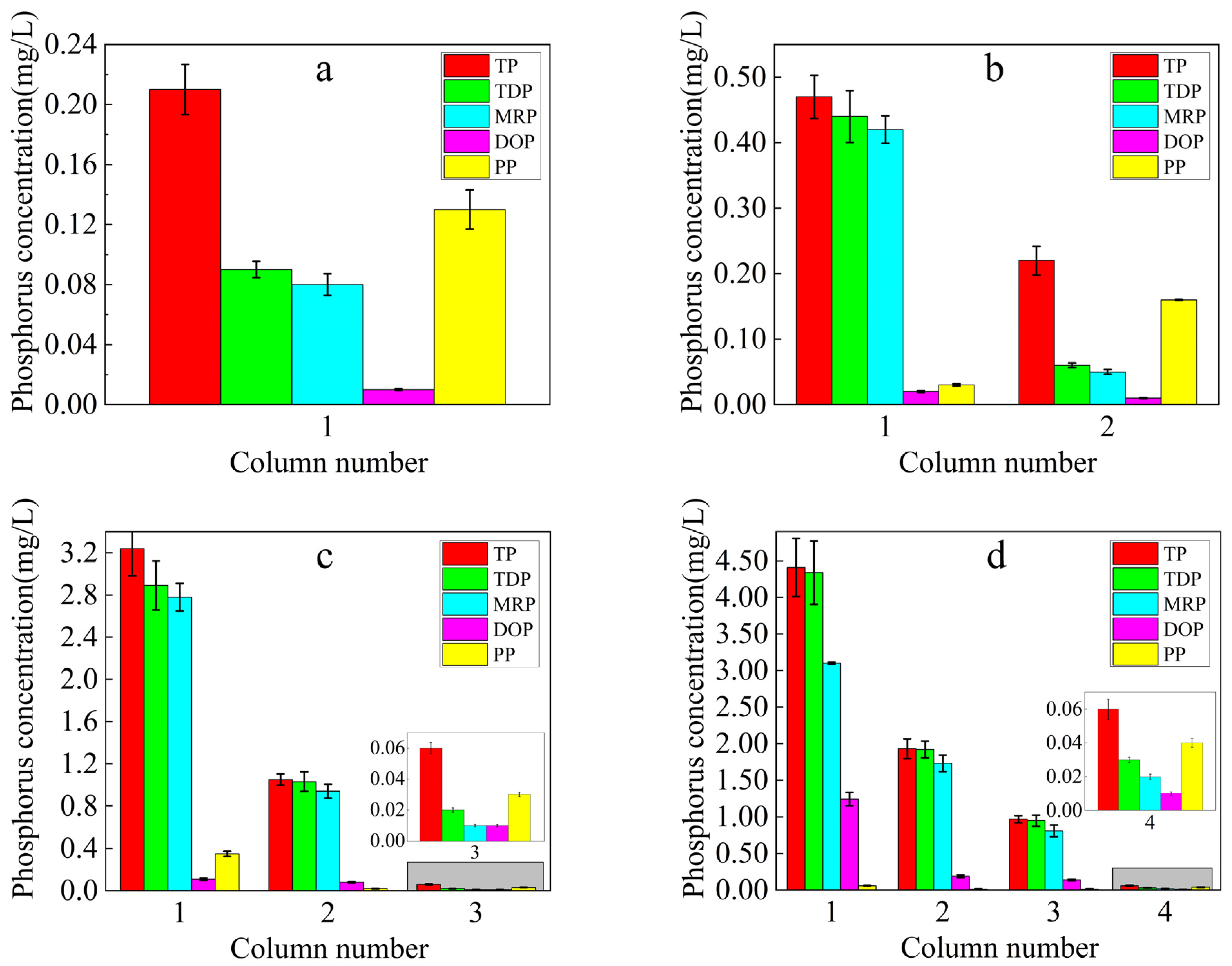

3.2. Effect of RMG on Soil Phosphorus Loss Control

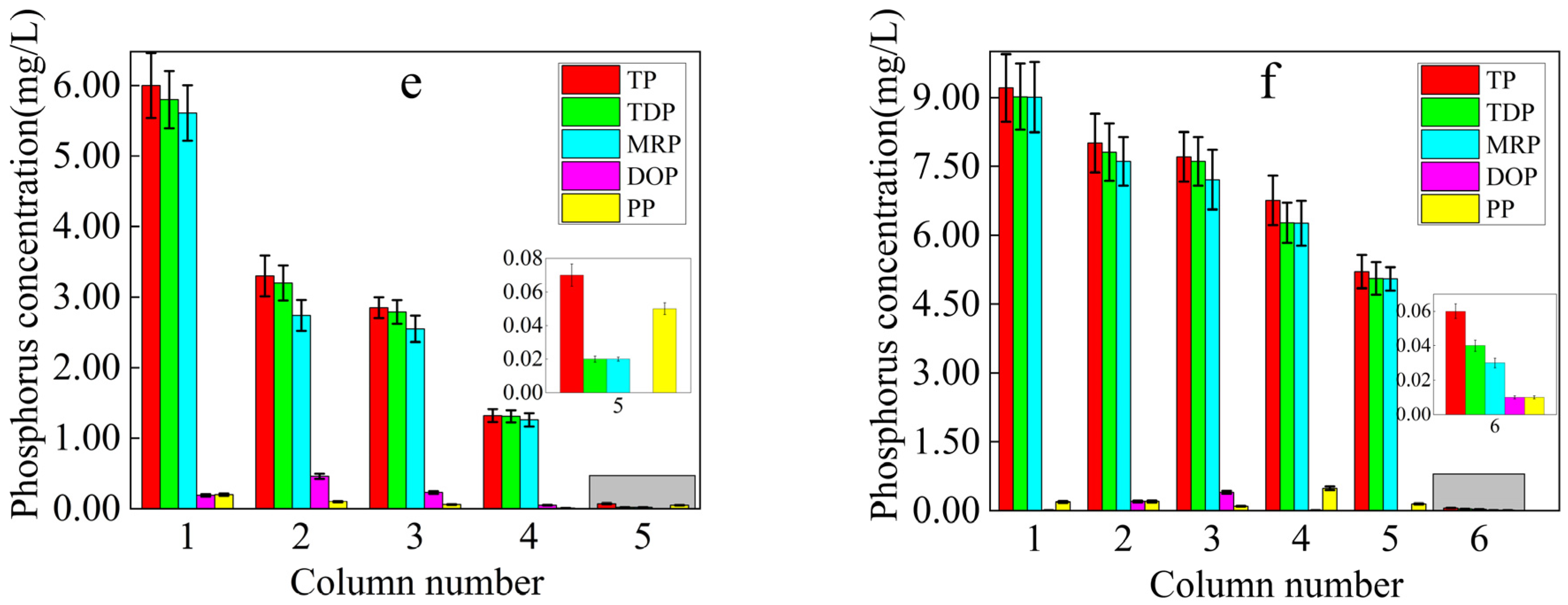

3.2.1. Soil Phosphorus Loss and Patterns

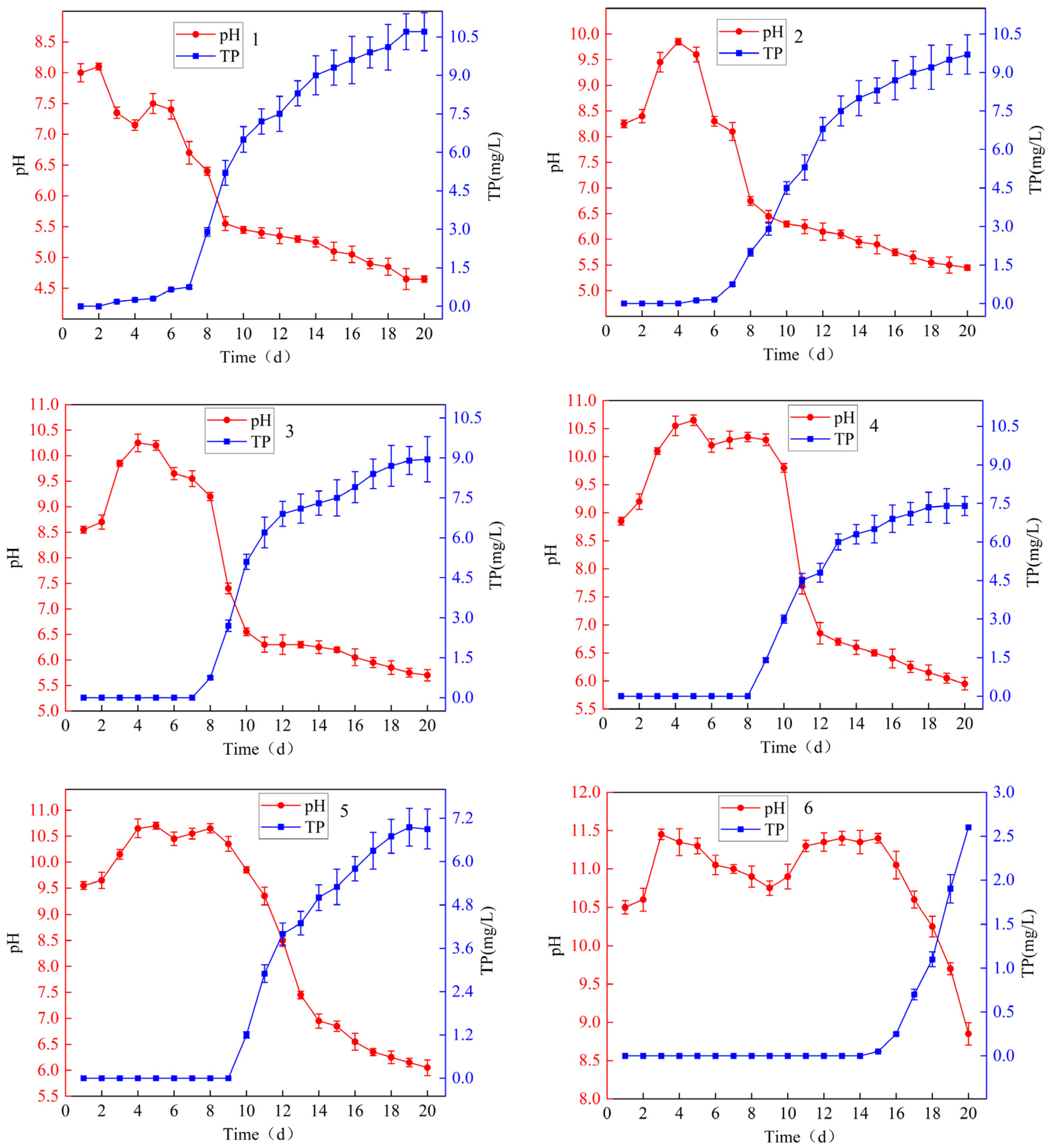

3.2.2. Changes in pH in Leachate

3.2.3. Changes in Soil Properties After RMG Application

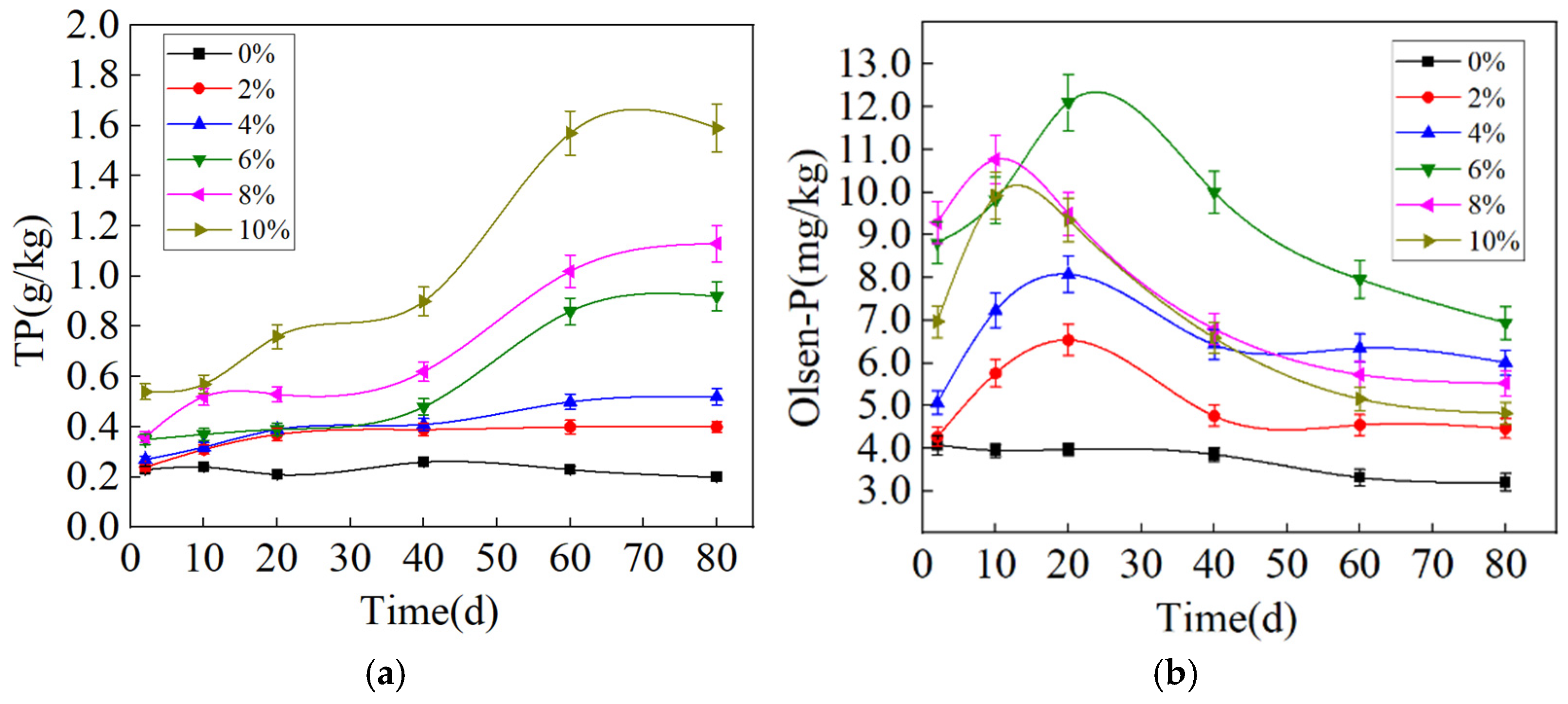

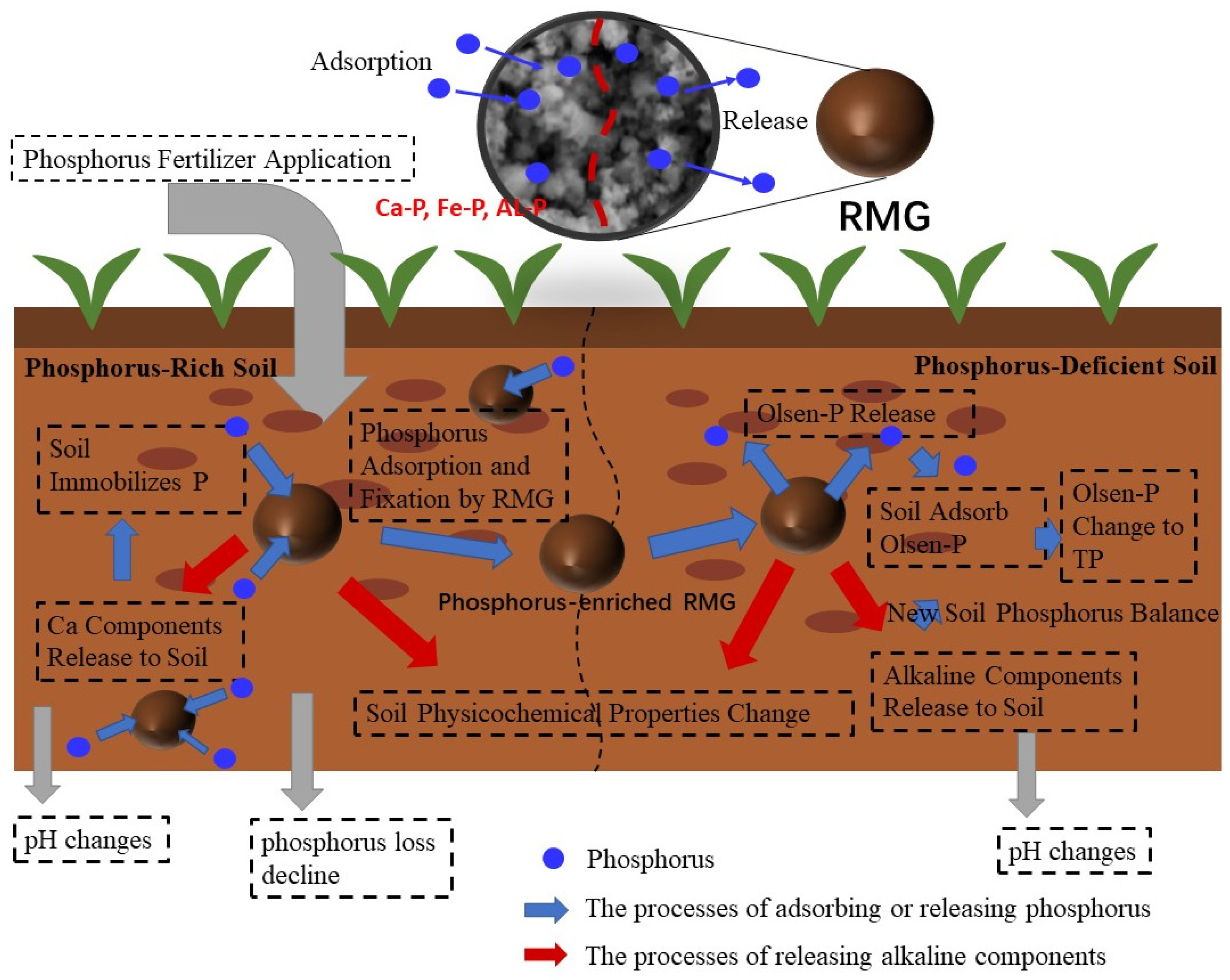

3.3. Effect of RMG on Phosphorus Release in Soil

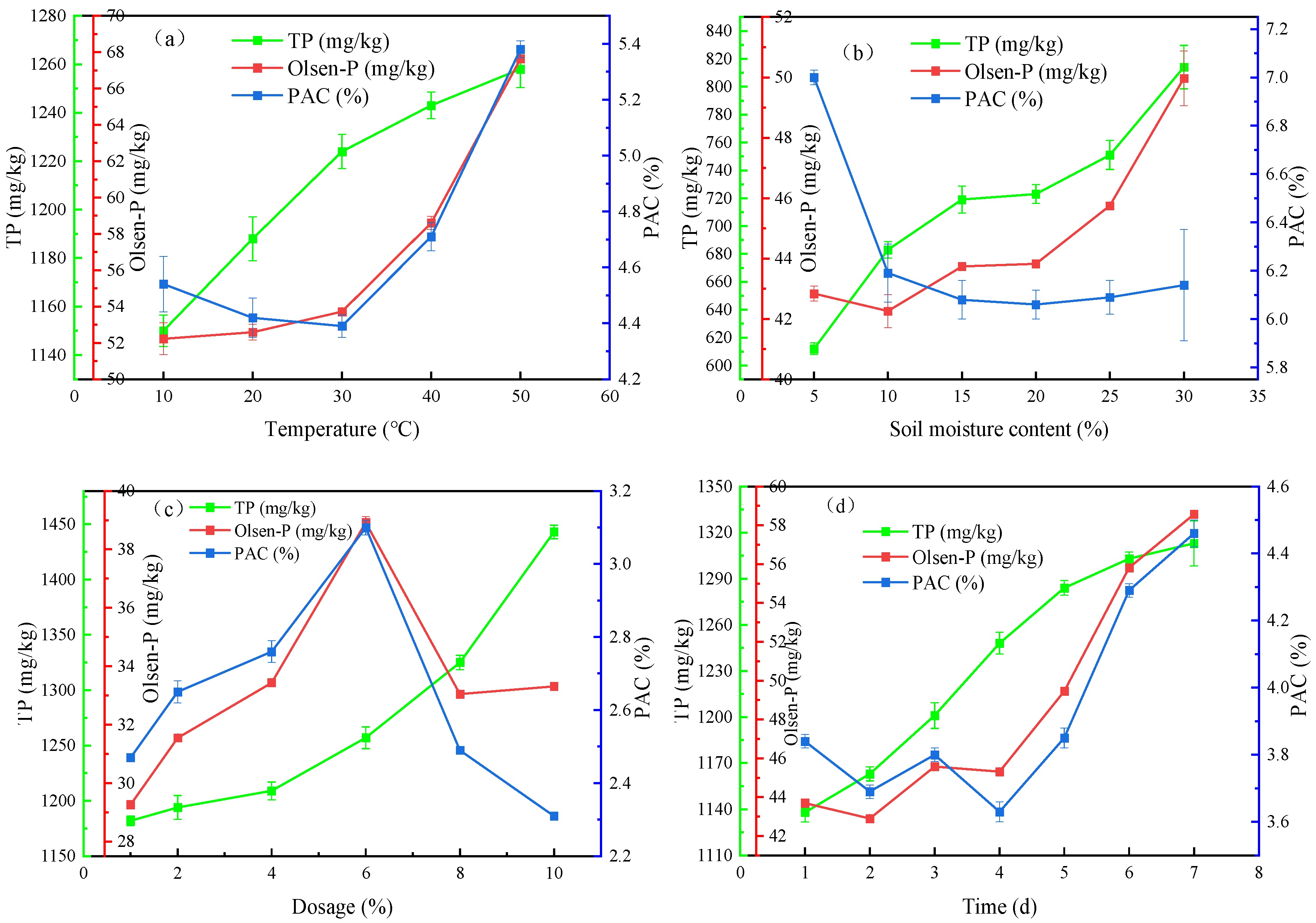

3.3.1. Influences of Experimental Factors on Phosphorus Release from RMG

3.3.2. Changes in Soil Properties After the P-Enriched RMG Application

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, X.; Xiao, J.; Wang, L.; Tian, S.; Liang, T.; Liu, Y. Identification of Areas Vulnerable to Soil Erosion and Risk Assessment of Phosphorus Transport in a Typical Watershed in the Loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 758, 143661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.A.; Mengual, J.; Palomares, A.E. Phosphorus Control and Recovery in Anthropogenic Wetlands Using Their Green Waste—Validation of an Adsorbent Mixture Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Han, X.; Hu, N.; Han, S.; Yuan, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Rengel, Z.; et al. The Crop Mined Phosphorus Nutrition via Modifying Root Traits and Rhizosphere Micro-food Web to Meet the Increased Growth Demand Under Elevated CO2. iMeta 2024, 3, e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Carneiro, J.S.; Ribeiro, I.C.A.; Nardis, B.O.; Barbosa, C.F.; Lustosa Filho, J.F.; Melo, L.C.A. Long-Term Effect of Biochar-Based Fertilizers Application in Tropical Soil: Agronomic Efficiency and Phosphorus Availability. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhou, H.; Li, S.; Shi, H.; Wang, S. Phosphorus Cycling in Sediments of Deep and Large Reservoirs: Environmental Effects and Interface Processes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehfard, R.; Jafari, R. Studies on the Valorization of Aluminum Production Residues into Bituminous Materials at Different Scales: A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jing, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Yan, L. Analysis of Alkali in Bayer Red Mud: Content and Occurrence State in Different Structures. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Zhou, J.-B. Preparation of Building Materials from Bayer Red Mud with Magnesium Cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, C.; Nerella, R.; Sri Rama Chand, M. Comparison of Mechanical and Durability Properties of Treated and Untreated Red Mud Concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soğancı, A.S.; Özkan, I.; Yenginar, Y.; Güzel, Y.; Özdemir, A. The Use of Waste Materials Red Mud and Bottom Ash as Road Embankment Fill. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, C. Red Mud-Based Polyaluminium Ferric Chloride Flocculant: Preparation, Characterisation, and Flocculation Performance. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 27, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Niu, Z.; Li, W.; Zhao, H.; Tang, Q. A Novel Process for Recovery of Aluminum, Iron, Vanadium, Scandium, Titanium and Silicon from Red Mud. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, R.; Zinoveev, D.; Konyukhov, Y.; Li, K.; Maslennikov, N.; Burmistrov, I.; Kargin, J.; Kravchenko, M.; Mukherjee, P.S. Extraction of Alumina and Alumina-Based Cermets from Iron-Lean Red Muds Using Carbothermic Reduction of Silica and Iron Oxides. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cui, P.; Tang, Y.; Tan, J.; Qin, M.; Cui, X. A Green Process for Treatment of Bayer Red Mud into Synthetic Soil. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Pan, X.; Guo, Y.; Lv, Z.; Wei, C.; Yu, H. Sustainable and Efficient Removal of Phosphorus from Wastewater through Red Mud Residue after Deep Dealkalization. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 700, 134782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, K.; Guo, H.; Tao, H.; Wang, X.; Cui, J. Red Mud-Derived Rose-like Layered Double Hydroxides for Excellent Phosphate Adsorption. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 726, 138027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Cheng, Z.; Tan, S.; Song, N.; Wei, Z.; Liu, Y. Efficient Recovery and Utilization of Phosphorus from Sewage Sludge via Alkalinous Fenton-like Oxidation with Pyrolysis-Modified Red Mud: Full Resource Utilization Attempt. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 475, 143588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Huang, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Evrendilek, F.; Liu, J. Valorizing Calcium-Loaded Red Mud Composites for Phosphorus Removal and Recovery. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 194, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, R.B.; Murnane, J.G.; Sharpley, A.N.; Herron, S.; Brye, K.R.; Simmons, T. Soil Phosphorus Dynamics Following Land Application of Unsaturated and Partially Saturated Red Mud and Water Treatment Residuals. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Zhang, T.; Fan, B.; Fan, B.; Yin, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Q. Enhanced Phosphorus Fixation in Red Mud-Amended Acidic Soil Subjected to Periodic Flooding-Drying and Straw Incorporation. Environ. Res. 2023, 229, 115960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scribot, C.; Maherzi, W.; Benzerzour, M.; Mamindy-Pajany, Y.; Abriak, N.-E. A Laboratory-Scale Experimental Investigation on the Reuse of a Modified Red Mud in Ceramic Materials Production. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 163, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sun, H.; He, C. Porous Red Mud Ceramsite for Aquatic Phosphorus Removal: Application in Constructed Wetlands. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 360, 124688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Zhong, Q.; Wang, L.; Niu, Z.; Xin, H.; Zhang, W. Performance of Red Mud/Biochar Composite Material (RMBC) as Heavy Metal Passivator in Pb-Contaminated Soil. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 109, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Niu, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Wang, L.; He, S.; Xu, M.; Wang, J. Preparation and Characterization of Red Mud/Fly Ash Composite Material (RFCM) for Phosphate Removal. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 109, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 11893-89; Water Quality—Determination of Total Phosphorus—Ammonium Molybdate Spectrophotometric Method. National Environmental Protection Agency of China: Beijing, China, 1989.

- HJ 962-2018; Soil—Determination of pH—Potentiometry. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- HJ 632-2011; Soil—Determination of Total Phosphorus by Alkali Fusion—Mo-Sb Anti spectrophotometric method. Ministry of Environmental Protection of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- HJ 704-2014; Soil Quality—Determination of Available Phosphorus—Sodium Hydrogen Carbonate Solution—Mo-Sb Anti-Spectrophotometric Method. Ministry of Environmental Protection of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- HJ/T 299–2007; Solid Waste—Extraction Procedure for Leaching Toxicity—Sulphuric Acid and Nitric Acid Method. National Environmental Protection Agency of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Ye, J.; Cong, X.; Zhang, P.; Hoffmann, E.; Zeng, G.; Liu, Y.; Fang, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H. Interaction between Phosphate and Acid-Activated Neutralized Red Mud during Adsorption Process. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 356, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, G. Preparation and Characterization of Porous Anorthite Ceramics from Red Mud and Fly Ash. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2020, 17, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wu, Z.; Fang, X.; Zhong, Q.; Yang, J.; Yan, J.; Li, Q. Preparation and Characterization of Clay-Oyster Shell Composite Adsorption Material and Its Application in Phosphorus Removal from Wastewater. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 32, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, M.; Wang, H.; Du, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liao, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z. Red Mud Modified Sludge Biochar for the Activation of Peroxymonosulfate: Singlet Oxygen Dominated Mechanism and Toxicity Prediction. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 140388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.C. Fundamentals of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; ISBN 1-4200-6930-6. [Google Scholar]

- Mbasabire, P.; Murindangabo, Y.T.; Brom, J.; Byukusenge, P.; Ufitikirezi, J.D.D.M.; Uwihanganye, J.; Umurungi, S.N.; Ntezimana, M.G.; Karimunda, K.; Bwimba, R. Remediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils Using Phosphate-Enriched Sewage Sludge Biochar. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Su, Z.; Ma, X.; Fu, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, L.; Liu, M. Preparation of Fe/C-MgCO3 Micro-Electrolysis Fillers and Mechanism of Phosphorus Removal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 13372–13392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Ma, H.; Zhu, Y.; Bing, X.; Wang, K.; Liu, F.; Ding, J.; Wei, J.; Song, K. Characterization of Organic Phosphorus in Soils and Sediments of a Typical Temperate Forest Reservoir Basin: Implications for Source and Degradation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 179, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Peng, X.; Luan, Z.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y. Reduction of Phosphorus Release from High Phosphorus Soil by Red Mud. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 65, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, V.F.; Brown, B.A.; Harris, M.A. Quenching of Phosphorus Fixation with Organic Wastes in a Bauxite Mine Overburden. Environ. Earth Sci. 2011, 63, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sekhon, B.S.; Singh, P.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Kesawat, M.S. Response of Biochar Derives from Farm Waste on Phosphorus Sorption and Desorption in Texturally Different Soils. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, C.; Yao, X.; Song, Z.; Dong, X. Mechanical and Leaching Characteristics of Red Mud Residue Solidified/Stabilized High Cu(II)-Contaminated Soil. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 81, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 3838-2002; Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water. National Environmental Protection Agency of China: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Liu, Q.; Ding, S.; Chen, X.; Sun, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhang, C. Effects of Temperature on Phosphorus Mobilization in Sediments in Microcosm Experiment and in the Field. Appl. Geochem. 2018, 88, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Gong, F.; Guan, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Chi, D.; Wu, Q.; O’Connor, J.; Bolan, N.S.; Siddique, K.H.M. Alternate Wetting and Drying Irrigation with Biochar-Based Struvite Enhances Phosphorus Availability, Reduces Phosphorus Loss Potential, and Improves Yield and Water Use Efficiency in Paddy Systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 319, 109797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, C.; Zhang, S.; Wei, W.; Liang, B.; Li, J.; Ding, X. Straw and Optimized Nitrogen Fertilizer Decreases Phosphorus Leaching Risks in a Long-Term Greenhouse Soil. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Ye, Y.; Nie, Z.; Su, M.; Xu, Z. Effect of pH on the Release of Soil Colloidal Phosphorus. J. Soils Sediments 2010, 10, 1548–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, S.; Xu, M. Changes in Olsen Phosphorus Concentration and Its Response to Phosphorus Balance in Black Soils under Different Long-Term Fertilization Patterns. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helfenstein, J.; Tamburini, F.; von Sperber, C.; Massey, M.S.; Pistocchi, C.; Chadwick, O.A.; Vitousek, P.M.; Kretzschmar, R.; Frossard, E. Combining Spectroscopic and Isotopic Techniques Gives a Dynamic View of Phosphorus Cycling in Soil. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, X.; Cai, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Shen, J.; Cai, Z. Effects of Different Long-Term Cropping Systems on Phosphorus Adsorption and Desorption Characteristics in Red Soils. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raw Materials | O | C | Si | Ca | Al | Fe | Na | Mg | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red mud | 43.89 | 10.84 | 13.09 | 13.96 | 6.68 | 5.92 | 1.87 | 2.84 | 0.91 |

| Fly ash | 46.63 | 8.52 | 22.06 | 4.30 | 14.07 | 4.42 | - | - | - |

| Cement | 43.31 | 12.28 | 10.37 | 10.70 | 7.63 | 10.49 | 5.22 | - | - |

| Elements | Original RMG | RMG After Dynamic Leaching Experiment | RMG After Phosphorus Releasing Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| O | 69.8 | 71.85 | 68.34 |

| Si | 3.91 | 6.63 | 2.51 |

| Al | 2.5 | 5.52 | 2.58 |

| Na | 0.44 | 0.09 | 0.51 |

| Mg | 0.44 | 2.06 | 0.69 |

| P | 0 | 1.35 | 8.69 |

| K | 0.11 | 0.92 | 0.2 |

| Fe | 3.4 | 2 | 1.34 |

| Ti | 0.94 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

| Ca | 18.45 | 9.24 | 14.81 |

| Ni | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Column Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dosage of RMG | 0% | 2% | 4% | 6% | 8% | 10% |

| The leaching days of P loss | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 14 |

| Critical value of P loss in soil (mg/kg) | 64.41 | 104.90 | 145.39 | 165.64 | 185.88 | 287.10 |

| Capacity of P maintained in soil (adjusted for the value) (mg/kg) | - | 40.49 | 80.98 | 101.23 | 121.47 | 222.69 |

| Elements | O | Si | Al | Na | Mg | P | K | Fe | Ti | Ca | Ni | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original soil | 70.51 | 15.74 | 7.66 | 0.98 | 1.28 | 0.08 | 1.11 | 1.48 | 0.16 | 1.01 | 0.03 | 100 |

| Soil after RMG application | 71.91 | 9.14 | 4.02 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 3.56 | 0.87 | 1.17 | 0.1 | 7.5 | 0 | 100 |

| Elements | Cr | Mn | Ni | Cu | Zn | As | Se | Cd | Pb | V | Ba |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lixivium of original soil | 0.01 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.05 |

| Lixivium of soil after RMG application | 0.04 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.3 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.07 |

| Environmental quality standard—level III | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 1 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Yang, B.; Niu, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, D.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z. A Novel Dual-Function Red Mud Granule Mediated the Fate of Phosphorus in Agricultural Soils: Pollution Mitigation and Resource Recycling. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10910. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410910

Zhao Y, Yang B, Niu Z, Wang L, Yang D, Wang J, Chen Z. A Novel Dual-Function Red Mud Granule Mediated the Fate of Phosphorus in Agricultural Soils: Pollution Mitigation and Resource Recycling. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10910. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410910

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yaqin, Bingyu Yang, Zixuan Niu, Liping Wang, Dejun Yang, Jing Wang, and Zihao Chen. 2025. "A Novel Dual-Function Red Mud Granule Mediated the Fate of Phosphorus in Agricultural Soils: Pollution Mitigation and Resource Recycling" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10910. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410910

APA StyleZhao, Y., Yang, B., Niu, Z., Wang, L., Yang, D., Wang, J., & Chen, Z. (2025). A Novel Dual-Function Red Mud Granule Mediated the Fate of Phosphorus in Agricultural Soils: Pollution Mitigation and Resource Recycling. Sustainability, 17(24), 10910. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410910