Mitigating the Urban Heat Island Effect and Heatwaves Impact in Thessaloniki: A Satellite Imagery Analysis of Cooling Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Remote Sensing Data

2.3. Remote Sensing Analysis

2.3.1. LST Retrieval

- Lλ = Top of Atmospheric (TOA) Spectral Radiance

- ML = Band-specific multiplicative rescaling factor from the metadata (RADIANCE_MULT_BAND_x, where x is the band number), in this case band 10 has ML = 3.3420 × 10−4

- Qcal = The band 10 image

- AL = Band-specific additive rescaling factor from the metadata (RADIANCE_ADD_BAND_x, where x is the band number), in this case band 10 has AL = 0.1

- BT = Top of atmosphere brightness temperature (C)

- K1 = Band-specific thermal conversion constant from the metadata (K1_CONSTANT_BAND_x, where x is the thermal band number), in this case band 10 has K1 = 774.8853

- K2 = Band-specific thermal conversion constant from the metadata (K2_CONSTANT_BAND_x, where x is the thermal band number), in this case band 10 has K2 = 1321.0789

- Lλ = Top of Atmosheric (TOA) Spectral Radiance

- LST = Land surface temperature (C°)

- W = Wave length of emitted radiance (=0.00115)

- BT = Top of atmosphere brightness temperature (C)

- E = Land surface emissivity

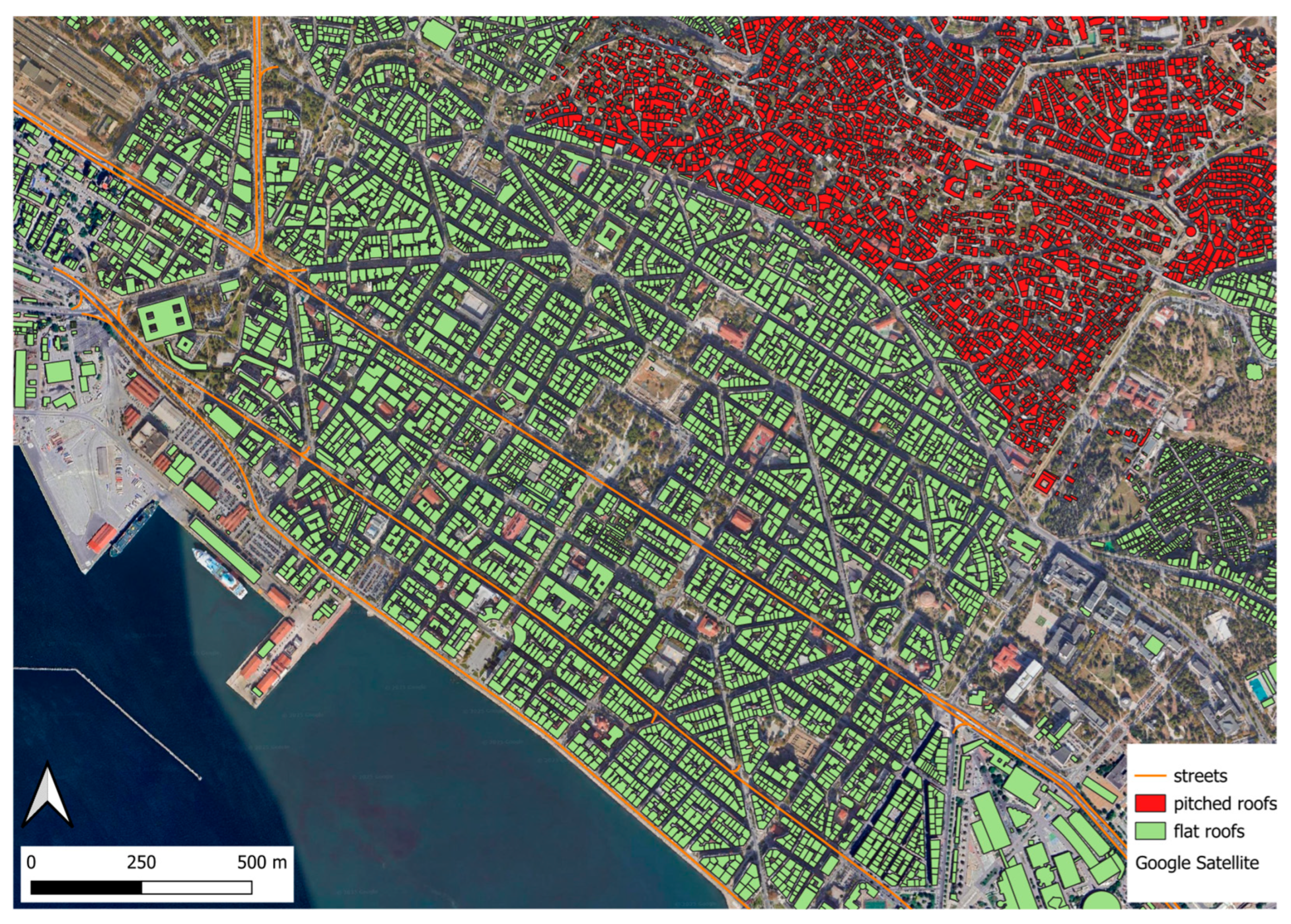

2.3.2. Analysis of Urban Configuration

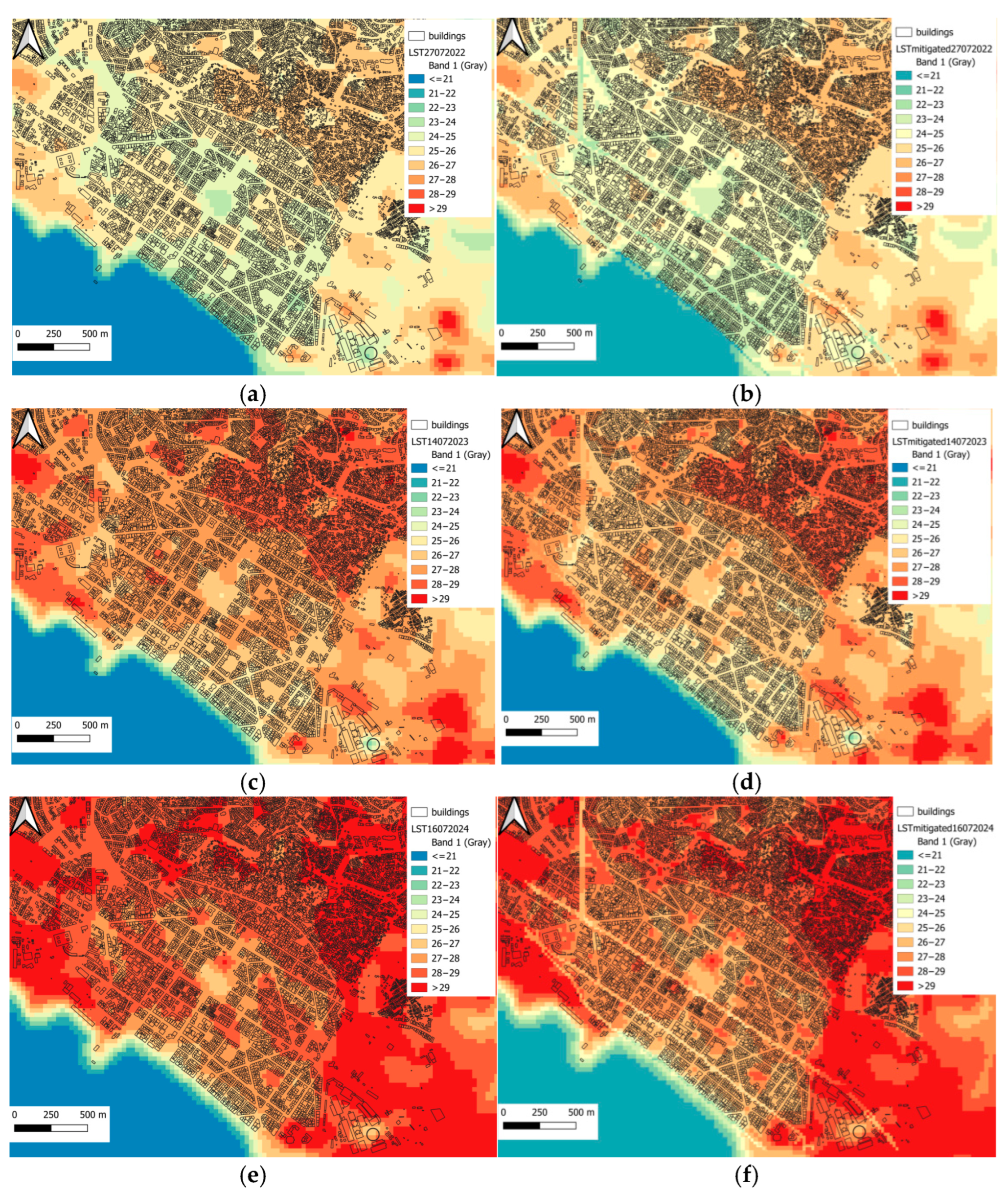

3. Results

3.1. Urban Center Configuration and Existing Heatwave Resilience Measures

3.2. Proposed Mitigation Strategies

4. Discussion

4.1. Insights from the Main Findings

4.2. Limitations and Uncertainties

4.3. Embedding Findings in European and Global Policy Frameworks

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LST | Land Surface Temperature |

| UHI | Urban Heat Island |

| DSM | Digital Surface Model |

| NbS | Nature-based Solutions |

| OSM | OpenStreetMaps |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NDBI | Normalized Difference Built-up Index |

| TOA | Top of Atmospheric |

| BT | Brightness Temperature |

| NIR | Near-InfraRed |

| PV | Proportion of Vegetation |

| E | Land Surface Emissivity |

| SWIR | Short-Wave InfraRed |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| HNMS | Hellenic National Meteorological Service |

| WMO | World Meteorological Organization |

| NOA | National Observatory of Athens |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

References

- Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.E.; Lewis, S.C. Increasing trends in regional heatwaves. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.J. Future changes in heatwave severity, duration and frequency due to climate change for the most populous cities. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2020, 30, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaviside, C.; Macintyre, H.; Vardoulakis, S. The urban heat island: Implications for health in a changing environment. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission: The European Green Deal; COM (2019) 640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Papadopoulos, G.; Keppas, S.C.; Parliari, D.; Kontos, S.; Papadogiannaki, S.; Melas, D. Future Projections of Heat Waves and Associated Mortality Risk in a Coastal Mediterranean City. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Research Centre. Cities Are Often 10–15 °C Hotter Than Their Rural Surroundings. 2022. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/jrc-news-and-updates/cities-are-often-10-15-degc-hotter-their-rural-surroundings-2022-07-25_en (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Li, D.; Bou-Zeid, E. Synergistic Interactions between Urban Heat Islands and Heat Waves: The Impact in Cities Is Larger than the Sum of Its Parts. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2013, 52, 2051–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law No 2021-1104 on the Fight Against Climate Change and the Reinforcement of Resilience in the Face of Its Effects—Climate Change Laws of the World. Available online: https://climate-laws.org/documents/law-no-2021-1104-on-the-fight-against-climate-change-and-the-reinforcement-of-resilience-in-the-face-of-its-effects_5af0 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- European Environment Agency, European Topic Centre Climate Change Adaptation (ETC CCA) and European Topic Centre Urban Land and Soil (ETC ULS). Urban Adaptation to Climate Change in Europe 2016—Transforming Cities in a Changing Climate. Publications Office. 2016. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2800/021466 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- ICLEI, Urban Greening Plans Reimagine a More Sustainable and Inclusive Future. 2024. Available online: https://iclei-europe.org/news?Urban_Greening_Plans_reimagine_a_more_sustainable_and_inclusive_future_&newsID=tIVW9pMo (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Velázquez, J.; Anza, P.; Gutiérrez, J.; Sánchez, B.; Hernando, A.; García-Abril, A. Planning and selection of green roofs in large urban areas: Application to Madrid metropolitan area. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, C.; Koukoula, M.; Saviolakis, P.M.; Zerefos, C.; Loupis, M.; Masouras, C.; Pappa, A.; Katsafados, P. Green roofs as a nature-based solution to mitigate urban heating during a heatwave event in the city of Athens, Greece. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, A.; Karachaliou, E.; Dosiou, A.; Tavantzis, I.; Stylianidis, E. Exploring patterns of surface urban heat island intensity: A comparative analysis of three Greek urban areas. Discov. Cities 2024, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.Y.; Teller, J. Assessing urban heat island mitigation potential of realistic roof greening across local climate zones: A highly-resolved Weather Research and Forecasting model study. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 944, 173728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synnefa, A.; Karlessi, T.; Gaitani, N.; Santamouris, M.; Assimakopoulos, D.N.; Papakatsikas, C. Experimental testing of cool colored thin layer asphalt and estimation of its potential to improve the urban microclimate. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorio, M.; Paparella, R. Climate mitigation strategies: The use of cool pavements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Serrone, G.; Peluso, P.; Moretti, L. Evaluation of Microclimate Benefits Due to Cool Pavements and Green Infrastructures on Urban Heat Islands. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, P.; Persichetti, G.; Moretti, L. Effectiveness of Road Cool Pavements, Greenery, and Canopies to Reduce the Urban Heat Island Effects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, A.; Kahe, N. Evaluating the Role of Green Infrastructure in Microclimate and Building Energy Efficiency. Buildings 2024, 14, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, C.; Verma, S.K.; Sen, S. Synergistic Deployment of Green Infrastructure and Reflective Pavements for Mitigation of UHI within Urban Blocks. Discov. Cities 2025, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, K.R.; Wells, M.J.; Kershaw, T. Utilising green and bluespace to mitigate urban heat island intensity. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Haddad, S.; Saliari, M.; Vasilakopoulou, K.; Synnefa, A.; Paolini, R.; Ulpiani, G.; Garshasbi, S.; Fiorito, F. On the energy impact of urban heat island in Sydney: Climate and energy potential of mitigation technologies. Energy Build. 2018, 166, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tang, J. Study on the influence of retroreflective materials on the ‘secondary reflection’ on the room above the horizontal sunshade. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USGS Science for a Changing World. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Stamou, A.; Manika, S.; Patias, P. Estimation of land surface temperature and urban patterns relationship for urban heat island studies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on “Changing Cities”, Skiathos Island, Greece, 18–21 June 2013; Volume 2, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Saputra, R. Mapping Land Surface Temperature (LST) Using Landsat-8 Imagery in ArcMAP. Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/ (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Mondal, S.K.; Patel, V.D.; Bharti, R.; Singh, R.P. Causes and effects of Shisper glacial lake outburst flood event in Karakoram in 2022. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2264460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhairi, A.; Nur Syahira Azlyn, A.; Nur Suhaila, M.R.; Mohd Zaini, M. Land use classification and mapping using Landsat imagery for GIS database in Langkawi Island. Sci. Herit. J. 2020, 2, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J.W., Jr.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with Erts. NASA Special Publication. 1974. Volume 351. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19740022614/downloads/19740022614.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Zha, Y.; Gao, J.; Ni, S. Use of normalized difference built-up index in automatically mapping urban areas from TM imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. Landsat 8-9 Collection 2 Level 2 Science Product Guide. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/media/files/landsat-8-9-collection-2-level-2-science-product-guide (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Peng, L.L.H.; Jim, C.Y. Green-roof effects on neighborhood microclimate and human thermal sensation. Energies 2013, 6, 598–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Gaitani, N.; Spanou, A.; Saliari, M.; Giannopoulou, K.; Vasilakopoulou, K.; Kardomateas, T. Using cool paving materials to improve microclimate of urban areas—Design realization and results of the flisvos project. Build. Environ. 2012, 53, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization. Heatwave. Available online: https://wmo.int/topics/heatwave (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- WeatherSpark. July 2023 Weather History in Thessaloníki Greece. Available online: https://weatherspark.com/h/m/87975/2023/7/Historical-Weather-in-July-2023-in-Thessalon%C3%ADki-Greece#Figures-Temperature (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Antognelli, S.; Vizzari, M.; Schulp, C.J.E. Integrating ecosystem and urban services in policy-making at the local scale: The SOFA framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliano, A.; Detommaso, M.; Nocera, F.; Berardi, U. The adoption of green roofs for the retrofitting of existing buildings in the Mediterranean climate. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 2016, 7, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafli, M.F.; Nugraha, A.; Shaliza, A.Z.; Zainuddin, S.Z.; Safiqurrohman, F.A.; Kirana, K.H.; Dharmawan, I.A. CitarumView: A Google Earth Engine-based application for Citarum River monitoring. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1266, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyler, J.W.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Holden, Z.A.; Running, S.W. Remotely sensed land skin temperature as a spatial predictor of air temperature across the conterminous United States. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2016. [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Cai, H.; Xu, X.; Qiao, Z.; Han, D. Impacts of urban green space on land surface temperature from urban block perspectives. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R. Street design and urban canopy layer climate. Energy Build. 1988, 11, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Vide, J.; Moreno-Garcia, M.C. Probability values for the intensity of Barcelona’s urban heat island (Spain). Atmos. Res. 2020, 240, 104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ögçe, H.; Kaya, M.E. Urban heat island phenomenon in Istanbul: A comprehensive analysis of land use/land cover and local climate zone effect. Indoor Built Environ. 2024, 33, 1447–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P. (Ed.) The Climate of the Mediterranean Region: From the Past to the Future; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-12-416042-2. Available online: https://www.cmcc.it/publications/the-climate-of-the-mediterranean-region-from-the-past-to-the-future (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission: Forging a Climate-Resilient Europe—The New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change; COM(2021) 82 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:82:FIN (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Founda, D.; Santamouris, M. Synergies between Urban Heat Island and Heat Waves in Athens (Greece), during an Extremely Hot Summer (2012). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HNMS—Hellenic National Meteorological Service—HNMS Stations. Available online: https://emy.gr/en/hnms-stations (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- World Meteorological Organization. Available online: https://wmo.int/ (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- National Observatory of Athens (NOA) METEO Network. Available online: http://stratus.meteo.noa.gr/index.php (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Ahmad, M.N.; Zhengfeng, S.; Yaseen, A.; Khalid, M.N.; Javed, A. The Simulation and Prediction of Land Surface Temperature Based on SCP and CA-ANN Models Using Remote Sensing Data: A Case Study of Lahore. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2022, 88, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Urban Agenda for the EU: Multi-level Governance in Action; Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 5 June 2019; ISBN 978-92-76-03666-1. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/brochure/urban_agenda_eu_en.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

| LST (°C) | City Center | Old City | Industrial Area | East Side | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 July 2022 | Mean | 24.91 | 25.85 | 25.87 | 25.57 |

| Max | 27.07 | 27.86 | 28.07 | 30.57 | |

| Min | 20.9 | 23.54 | 20.79 | 22.97 | |

| SD | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 0.92 | |

| 14 July 2023 | Mean | 27.0 | 28.01 | 28.05 | 27.29 |

| Max | 28.94 | 29.2 | 30.45 | 32.01 | |

| Min | 21.9 | 25.34 | 21.63 | 22.99 | |

| SD | 0.87 | 0.51 | 0.76 | 1 | |

| 16 July 2024 | Mean | 27.95 | 29.05 | 29.24 | 29.21 |

| Max | 30.09 | 31.65 | 31.6 | 34.39 | |

| Min | 23.3 | 27.14 | 23.42 | 26.48 | |

| SD | 0.81 | 0.59 | 0.81 | 1.09 |

| LST (°C) | City Center | Old City | Industrial Area | East Side | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 July 2022 | Mean | 24.27 (−2.57%) | 25.63 (−0.85%) | 25.85 (−0.08%) | 25.47 (−0.39%) |

| Max | 27.07 | 27.86 | 28.07 | 30.57 | |

| Min | 20.25 (−3.11%) | 23.54 | 20.79 | 22.97 | |

| SD | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.98 | |

| 14 July 2023 | Mean | 26.36 (−2.37%) | 27.79 (−0.79%) | 28.04 (−0.04%) | 27.19 (−0.37%) |

| Max | 28.94 | 29.2 | 30.46 (+0.03%) | 32.01 | |

| Min | 21.81 (−0.41%) | 25.34 | 21.63 | 22.99 | |

| SD | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 1.05 | |

| 16 July 2024 | Mean | 27.32 (−2.25%) | 28.82 (−0.79%) | 29.23 (−0.03%) | 29.11 (−0.34%) |

| Max | 30.09 | 31.65 | 31.6 | 34.35 (−0.12%) | |

| Min | 23.3 | 27.11 (−0.11%) | 23.42 | 26.48 | |

| SD | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 1.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Falda, M.; Adamos, G.; Rađenović, T.; Laspidou, C. Mitigating the Urban Heat Island Effect and Heatwaves Impact in Thessaloniki: A Satellite Imagery Analysis of Cooling Strategies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410906

Falda M, Adamos G, Rađenović T, Laspidou C. Mitigating the Urban Heat Island Effect and Heatwaves Impact in Thessaloniki: A Satellite Imagery Analysis of Cooling Strategies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410906

Chicago/Turabian StyleFalda, Marco, Giannis Adamos, Tamara Rađenović, and Chrysi Laspidou. 2025. "Mitigating the Urban Heat Island Effect and Heatwaves Impact in Thessaloniki: A Satellite Imagery Analysis of Cooling Strategies" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410906

APA StyleFalda, M., Adamos, G., Rađenović, T., & Laspidou, C. (2025). Mitigating the Urban Heat Island Effect and Heatwaves Impact in Thessaloniki: A Satellite Imagery Analysis of Cooling Strategies. Sustainability, 17(24), 10906. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410906