1. Introduction

The home energy management system (HEMS) is an advanced technological framework designed to optimize residential energy consumption by intelligently coordinating distributed energy resources, household loads, and energy storage systems in response to dynamic electricity pricing and grid conditions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. A critical component of the HEMS is demand response (DR) [

7,

8], which plays a positive role in shifting peak loads and enhancing grid stability by incentivizing consumers to modify their electricity usage patterns, specifically reducing consumption during peak periods while increasing usage during off-peak hours. Nevertheless, widespread implementation of DR technology faces significant challenges, primarily stemming from the heterogeneous nature of residential loads and the inherent unpredictability of consumer energy consumption behaviors.

The HEMS is becoming popular in residential appliance management. Based on electricity pricing policies and user preferences, the HEMS can rationally coordinate residential participation in grid interactions while optimizing the operation of household electrical appliances to minimize electricity costs while maintaining appliance scheduling convenience [

9,

10]. User satisfaction in residential energy management is critically dependent on maintaining appliance operation within preferred time periods to ensure comfort preservation. While a strategic reduction in appliance usage can effectively lower electricity expenses, such measures frequently result in compromised comfort levels, potentially leading to user dissatisfaction. This creates a fundamental tension between economic efficiency and user satisfaction objectives. The challenge of simultaneously optimizing both cost reduction and satisfaction is further compounded by substantial variations in residential appliance portfolios—including differences in device quantity, appliance types, and usage patterns—all of which significantly impact overall energy consumption patterns and costs.

Significant research efforts have been devoted to address the appliance optimization scheduling problems in HEMS, such as electricity costs [

11,

12,

13] and user satisfaction [

14,

15,

16]. In ref. [

17], a new framework has been proposed to optimize three key parameters: electricity cost reduction, peak-to-average ratio reduction, and user comfort maximization, achieving dual benefits: consumer cost savings and grid operational stability through demand profile flattening. In ref. [

10], a multi-interval algorithm has been proposed by using metaheuristic optimization for residential appliance scheduling under real-time pricing. It minimizes electricity bills and peak demand while maintaining user comfort. In ref. [

8], a comprehensive home energy management model incorporating all load types has been developed, featuring a multi-objective optimization function that balances electricity cost reduction with user comfort maximization. This framework accounts for user preferences across multiple competing objectives, ensuring demand-side flexibility while meeting diverse consumer requirements.

Recent years have witnessed growing academic and industrial interest in multi-objective optimization algorithms (MOEAs) for appliance optimization scheduling problems [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. For example, ref. [

22] developed a strategy balancing electricity costs, waiting times, and peak loads. Ref. [

11] investigated methods to align grid demand with user requirements. Jafari et al. [

23] presented a comprehensive multi-objective model that conducts an in-depth analysis of issues related to pollution, financial considerations, and reliability. This model is solved by the

-constraints method and optimized employing the exchange market algorithm.

While significant research has been conducted on appliance optimization scheduling problems, the domain of dynamic scheduling optimization remains relatively unexplored. Current approaches predominantly model these problems as static optimization scenarios, despite their inherently dynamic nature in real-world applications. This dynamic characteristic necessitates the implementation of dynamic multi-objective evolutionary algorithms (DMOEAs) [

24] to effectively determine optimal scheduling solutions. For instance, when appliance priorities change in response to time-varying environmental conditions, the problem fundamentally transforms into a dynamic multi-objective optimization problem (DMOP) [

25], requiring adaptive solution methods. Unlike static MOEAs, dynamic MOEAs are designed to rapidly track the moving Pareto Optimal Front (POF) while maintaining a diverse Pareto Optimal Set (POS). Classical prediction strategies, which rely on traditional learning techniques, operate under the assumption that the training and test data are Independent and Identically Distributed (IID). This assumption is often violated in DMOPs, where the solution distribution shifts across changing environments. In contrast, transfer learning-based MOEAs do not require the IID assumption and have demonstrated superior prediction performance in these dynamic contexts. Based on the aforementioned analysis, this paper proposes a dynamic appliance scheduling optimization model under time-of-use (TOU) pricing schemes. The model simultaneously minimizes electricity costs and user dissatisfaction, where the latter is quantified based on the user’s preferences. Crucially, it involves adaptive weights that dynamically adjust to shifting appliance priorities under varying operational conditions. To solve this dynamic optimization problem, we introduce KPMT-DMOEA, a novel knee point-based manifold transfer algorithm. This approach leverages high-quality knee points from previous environments to generate optimized initial populations when responding to environmental changes, thereby enhancing solution quality and convergence speed.

To sum up, the main contributions of this paper can be divided into three points:

A dynamic appliance scheduling model under TOU pricing is proposed, incorporating user preferences to simultaneously minimize electricity cost and user dissatisfaction.

In response to environmental changes, we propose a knee point-based manifold transfer method to generate a new initial population, which extends the geodesic flow kernel by mapping data to a lower-dimensional space. This approach achieves higher computational efficiency than traditional transfer learning methods by transferring only a few high-quality knee solutions with good convergence and diversity.

Experimental results demonstrate the superiority of the proposed KPMT-DMOEA over state-of-the-art algorithms to solve dynamic appliance scheduling problems.

The rest of the paper is arranged as follows. In

Section 2, the dynamic home appliance scheduling model is explained. The KPMT-DMOEA algorithm for HEMS is detailed in

Section 3. The experimental studies for the scheduling application are described in

Section 4. Finally,

Section 5 draws up conclusions.

2. Dynamic Multi-Objective HEMS Model

This section establishes the mathematical model for each household appliance in the HEMS.

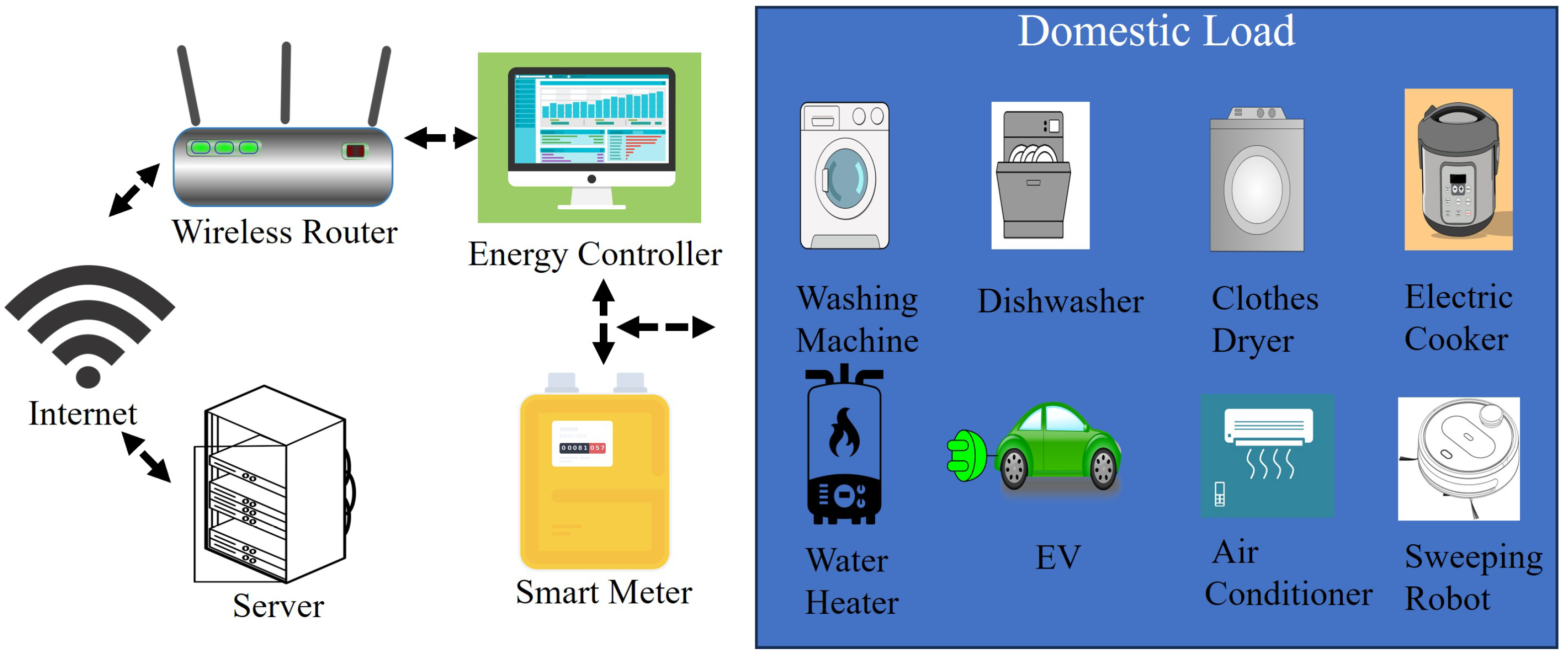

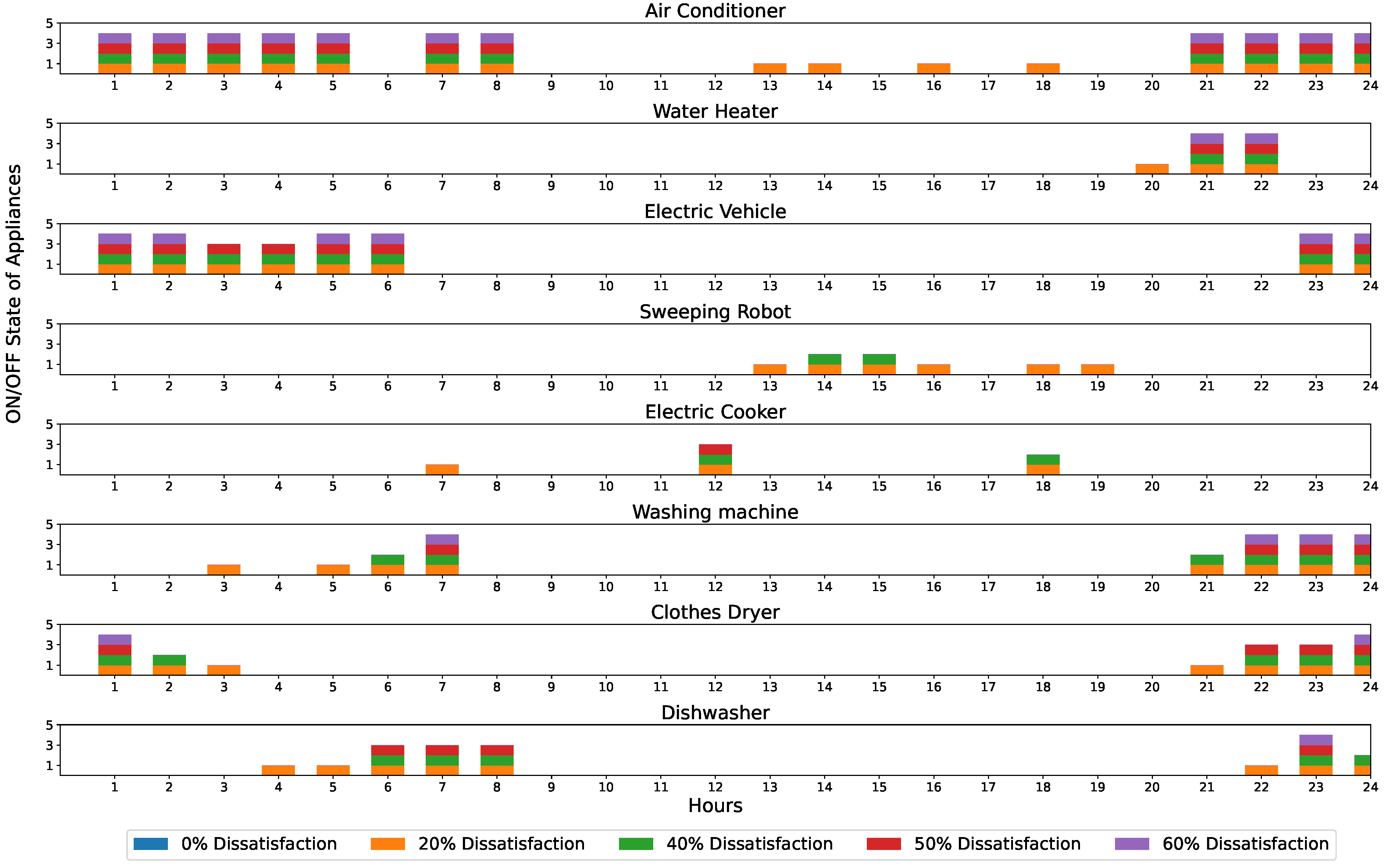

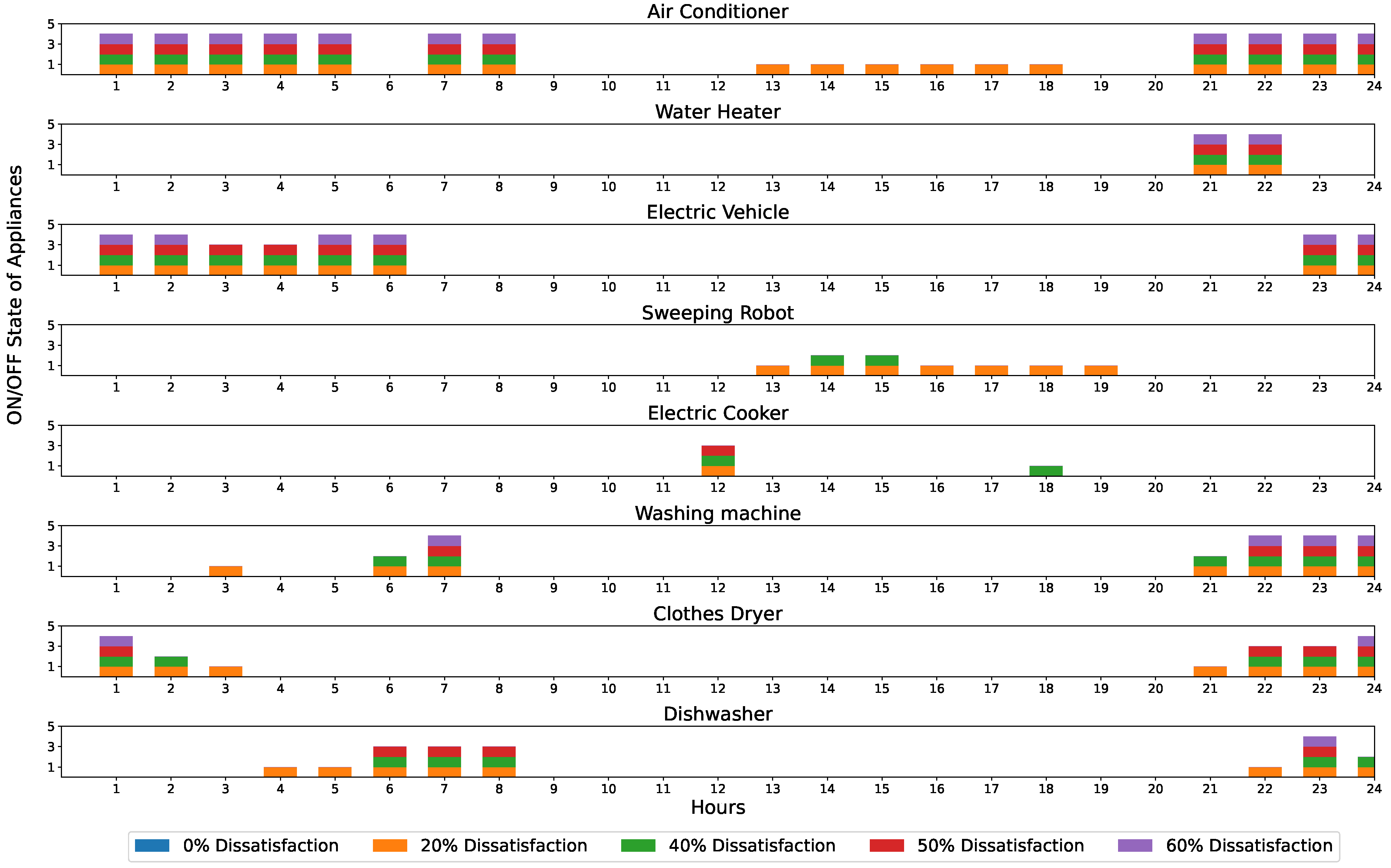

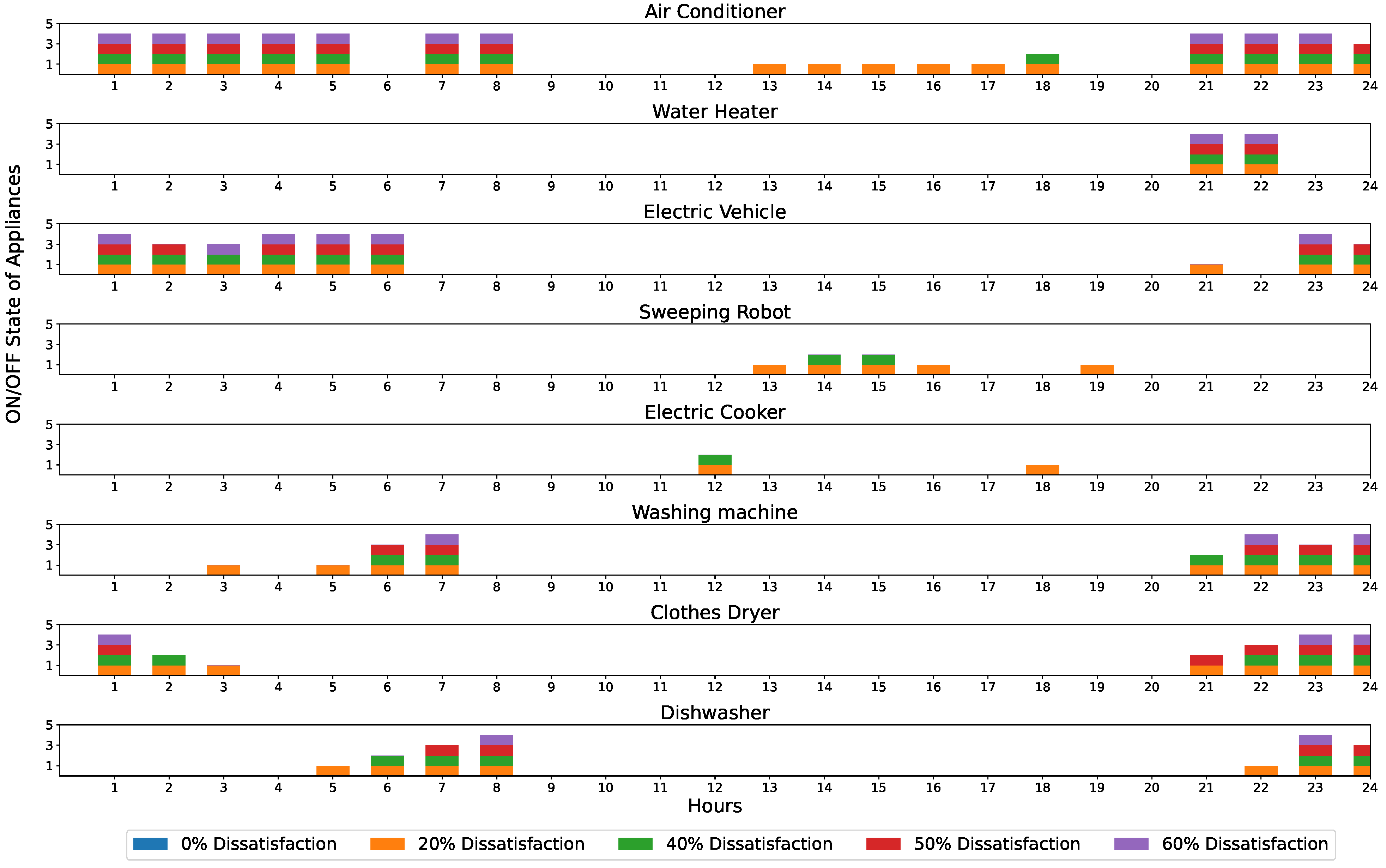

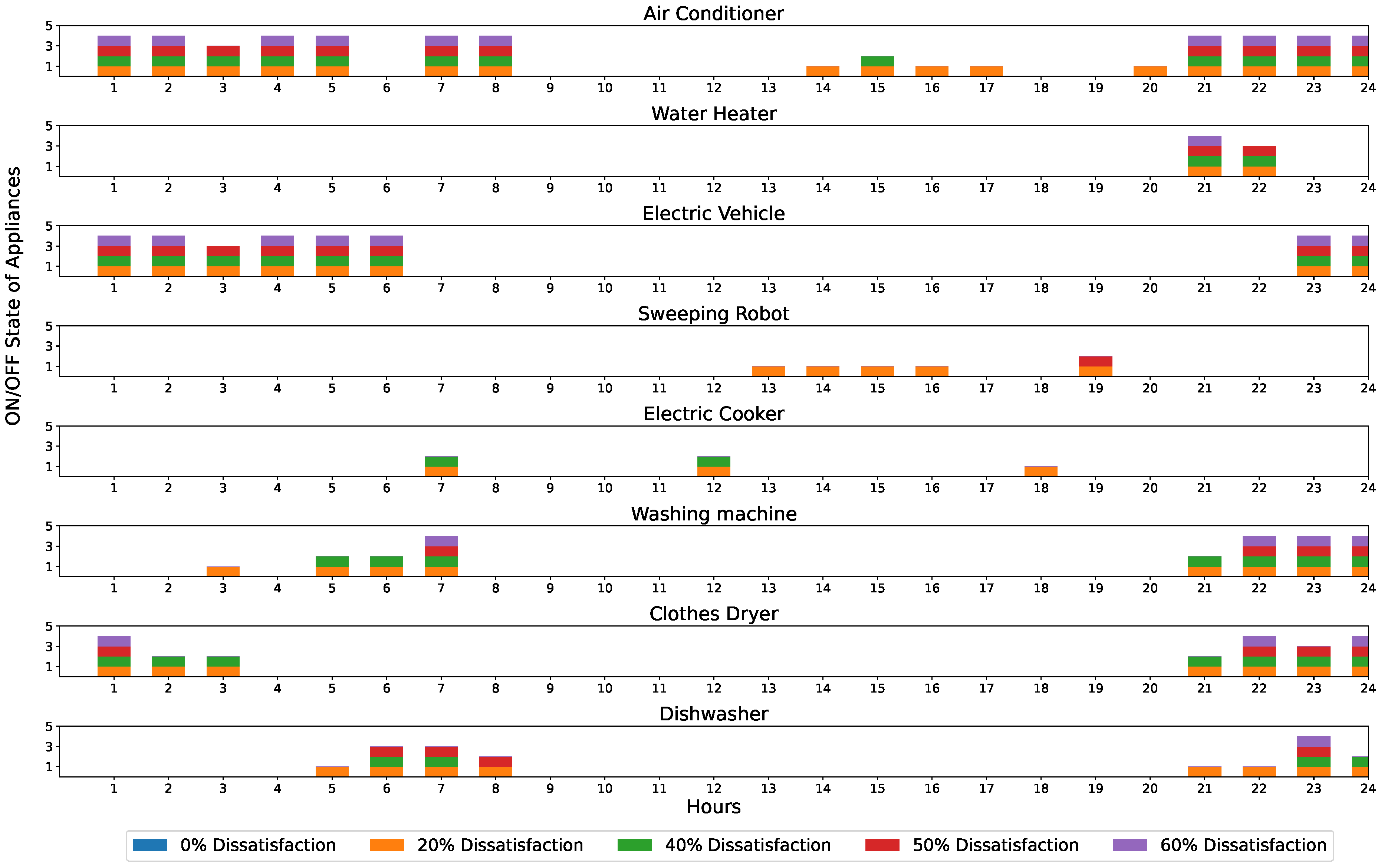

Figure 1 shows a home energy management system (HEMS) framework including eight home appliances: air conditioners, water heaters, electric vehicles, sweeping robots, electric cookers, washing machines, clothes dryers, and dishwashers. The KPMT-DMOEA algorithm is employed to determine the optimal on–off states of household appliances based on a dynamic multi-objective optimization model. The first objective function minimizes the total energy consumption cost, while the second objective accounts for user dissatisfaction. The goal of the KPMT-DMOEA algorithm is to optimally schedule appliance operations to simultaneously reduce energy costs and user discomfort. The following subsections detail the objective functions used in this dynamic multi-objective optimization approach for the HEMS.

2.1. Energy Cost

Let denote the time-of-use electricity tariff specified by the detailed implementation rules for peak and off-peak electricity pricing for residential users for each time slot . The duration of each time slot k is set to 1 h, with a scheduling cycle of 24 h. Accordingly, the value of K becomes 24. Specifically, corresponds to the time interval [0:00, 1:00], to the interval [1:00, 2:00], and so forth. J denotes the total number of schedulable appliances involved in the scheduling process, like an air conditioner, washing machine, and clothes dryer.

The first objective function is to reduce energy costs, expressed as follows:

where

denotes the total anticipated energy consumption of appliance

j over a single time slot.

denotes the optimal on–off statues of appliance

j at time slot

k, where

2.2. User Dissatisfaction

To align with user preferences, the system allows users to specify an optimal operating period for each appliance. During this period, the appliance’s status is set to “1” (ON), while remaining “0” (OFF) at all other times. This approach ensures that the appliance’s schedule adheres closely to the user’s habitual electricity consumption patterns. Specifically, the preferred operating time period for each load is configured according to the user’s preferences. User satisfaction can be expressed as follows:

where

defines the allowed operating interval, and

defines the preferred operating interval with the requirement that

.

Therefore, the minimization of the user dissatisfaction for the HEMS can be expressed as follows:

where the variable

represents the user satisfaction value of the

jth appliance at time

k, defined in (

3). The user satisfaction

for the

jth appliance at time

k can reach to 1 if it operates during the preference time interval. If the time

k is outside the allowed operating interval, it becomes 0. User satisfaction is directly tied to the reliable operation of each appliance within its permissible operational period.

Table 1 illustrates the electricity usage of eight schedulable appliances for a typical household, including the allowed operating interval, user preference interval, length of operation (LoT), and the rated power

. Here, only the charging processes of electric vehicle and sweeping robot are considered.

The priority weight quantifies the relative importance of the jth home appliance in the tth environment, where j represents the appliance index and t represents the varying operating environment. The ordinal relationship implies that th appliance has a lower user priority than th appliance in the tth environment. Practically, user priority weights for appliances exhibit both heterogeneity (due to varying user preferences) and time-dependency (influenced by dynamic daily activities). Consequently, we model these priority weights as time-varying parameters, where the dynamic nature of reflects adaptive prioritization under varying operational conditions.

3. KPMT-DMOEA Algorithm for HEMS

In this section, we propose KPMT-DMOEA, a novel knee point-based manifold transfer learning-based DMOEA for optimal appliance scheduling in dynamic environments to simultaneously minimize both energy costs and user dissatisfaction. KPMT-DMOEA leverages high-quality knee points from previous environments to generate an excellent initial population to help the static multi-objective evolutionary algorithm determine the optima of a changing environment efficiently and effectively.

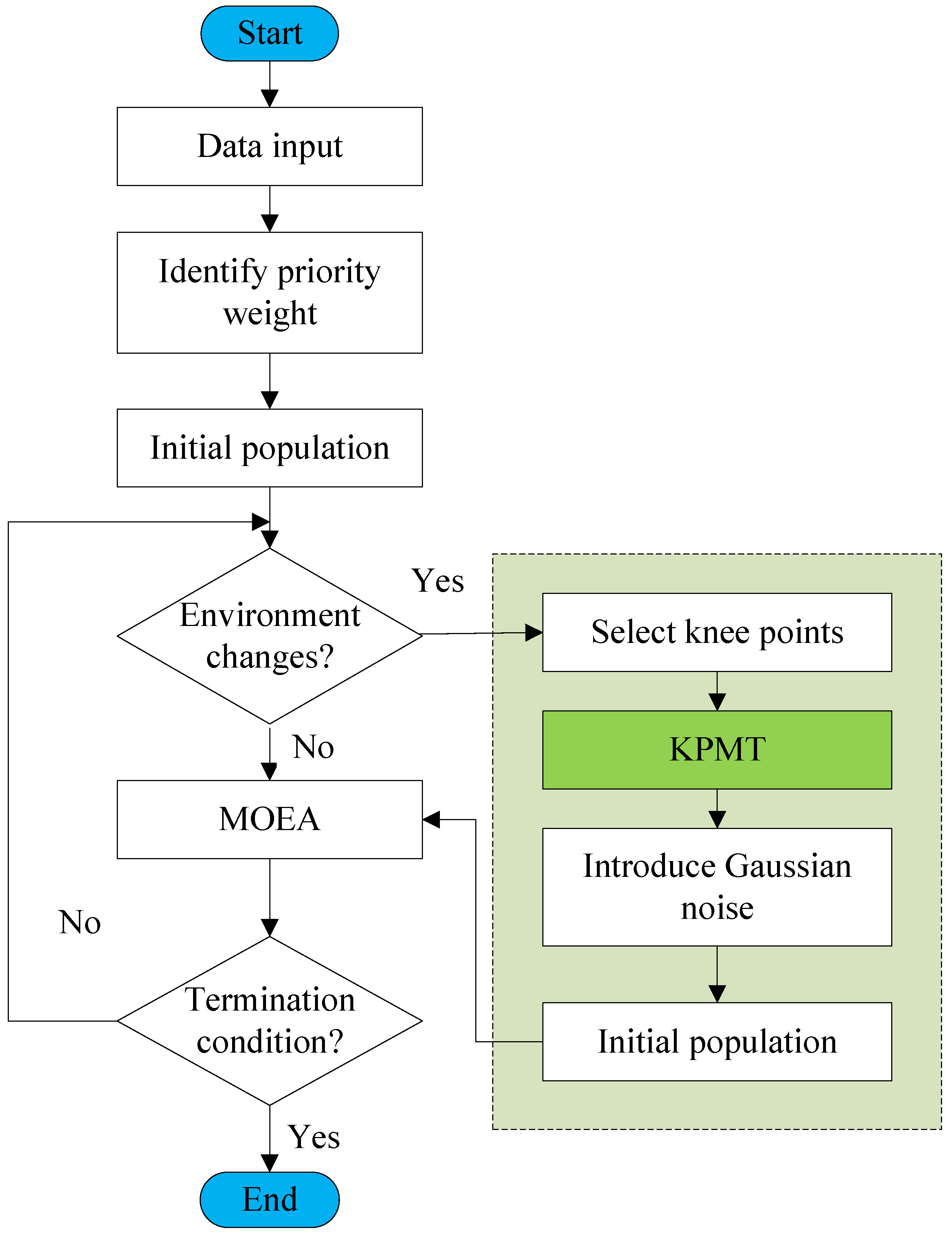

Figure 2 shows a flowchart that shows the procedure of the proposed KPMT-DMOEA to solve the dynamic home appliance scheduling optimization model.

The KPMT-DMOEA, presented in Algorithm 1, operates through several key phases. Initially, a population is randomly generated. When environmental changes are detected, the algorithm archives non-dominated solutions from the previous time step

and identifies regional knee points

from this archive [

26]. Then, it predicts current knee points

using

KPMT, which is detailed in

Section 3.1. This method leverages prior experience gained from knee points to predict the new location of solutions, thereby expediting the convergence in the subsequent evolutionary process. The archived solutions are re-evaluated under current conditions to identify non-dominated solutions

, while random samples

maintain population diversity. These components merge to form an initial population

, which is adjusted through either random truncation (if oversized) or Gaussian noise injection (if undersized). The population undergoes optimization via MOEA, with final solutions binarized through thresholding: values

indicate active appliances (1), while values

represent inactive states (0), yielding the optimal scheduling strategy.

| Algorithm 1:The framework of KPMT-DMOEA |

- Input:

: the dynamic optimization problem; N: the population size. - Output:

The POS of in different environments. - 1:

Randomly initiate N individuals as ; initialize ; - 2:

Evaluate the initial population with ; - 3:

while

stopping criterion not satisfied

do - 4:

if change detected then - 5:

t = t+1; - 6:

Store the non-dominated solutions in into ; - 7:

Find the regional knee points in ; - 8:

=KPMT(,,N); - 9:

Reevaluate the solutions in using to choose the non-dominated solutions ; - 10:

Generate the initial population ; - 11:

if then - 12:

Add Gaussian noise into ; - 13:

else - 14:

Delete individual in ; - 15:

end if - 16:

Evaluate using ; - 17:

end if - 18:

= MOEA ; - 19:

end while - 20:

return ;

|

3.1. KPMT

We propose a KPMT method that systematically incorporates prior knowledge acquired from knee points to guide subsequent search processes. The proposed method employs the improved geodesic flow kernel (GFK) [

27] to effectively project high-dimensional knee points onto a low-dimensional geodesic flow manifold, offering superior computational efficiency compared to conventional transfer learning approaches.

The algorithmic procedure begins with the initialization of an empty set, denoted as

, designed to store predicted knee points. Subsequently, a population

comprising

randomly generated individuals is created. An improved GFK framework [

24,

27] is then applied to construct the geodesic flow transformation

, facilitating the transfer of knowledge derived from

. Upon establishing

, individuals within each cluster are mapped onto the geodesic flow, yielding the corresponding geodesic flow kernel

. By evaluating the intrinsic similarity between the source and target domains within the manifold space, the optimal predicted solution

is determined through nearest-neighbor analysis. Specifically,

corresponds to the kernel

that exhibits minimal distance to

, as formalized below:

Finally, the set of optimal solutions constitutes the predicted individuals .

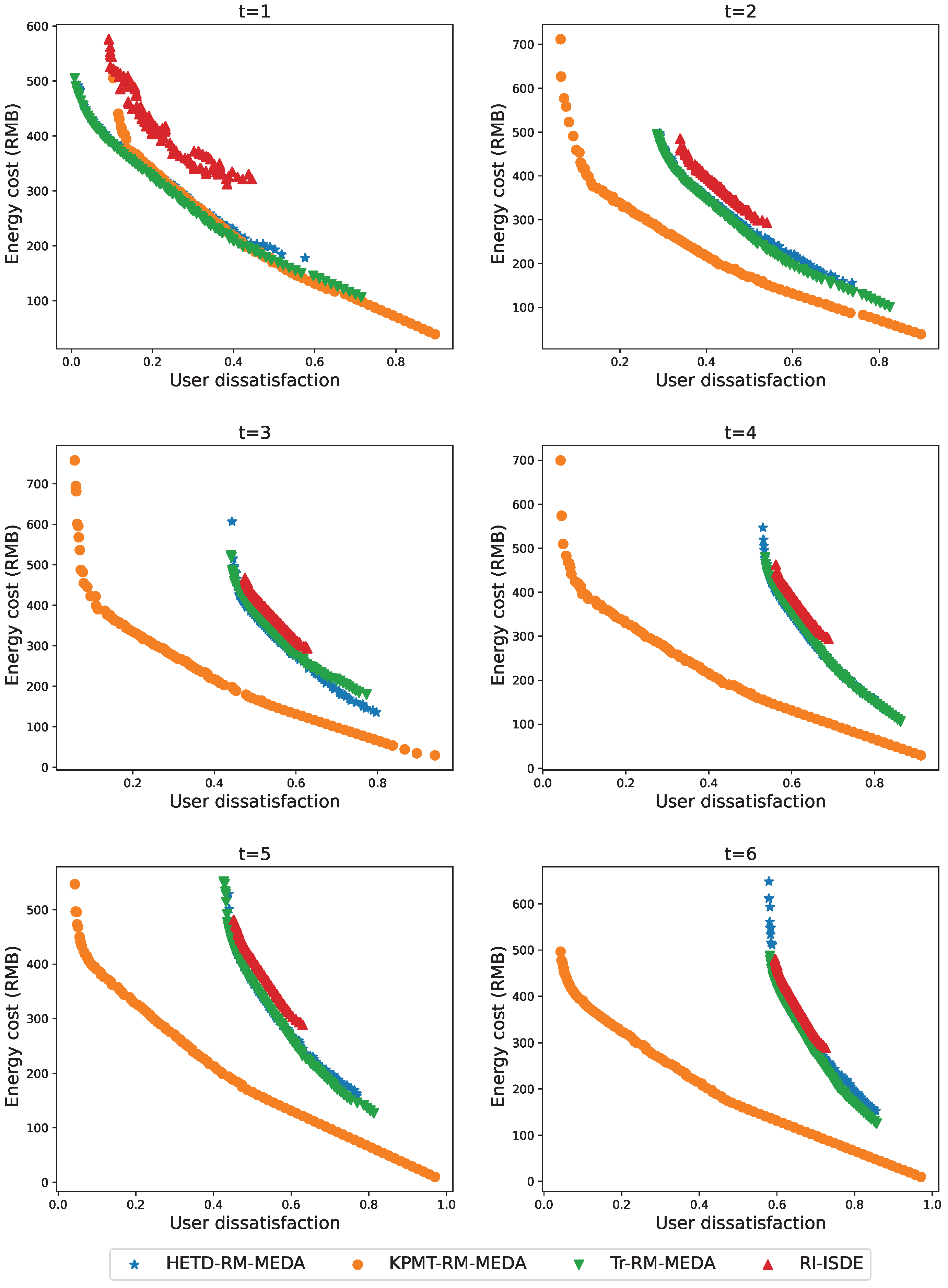

5. Conclusions

This paper presents an optimization model for dynamic appliance scheduling under time-of-use (TOU) pricing to minimize household electricity costs and user dissatisfaction. The model incorporates temporal variations in appliance priority weights, which are explicitly embedded within a weighted dissatisfaction function. A knee point-based manifold transfer algorithm (KPMT-DMOEA) is proposed to deal with the dynamic HEMS model, including eight home appliances, given the allowed operating interval and user preference. The experimental results demonstrate that effective appliance scheduling can simultaneously reduce energy expenditures and enhance user satisfaction. Compared with three state-of-the-art DMOEAs, the proposed KPMT-RM-MEDA has been demonstrated to be capable of efficiently tracking moving POFs and outperform others in most test instances. Some extensions for this paper can be further studied from the following aspects. The dynamic HEMS model is complex, involving multiple constraints such as the scheduling sequence of different appliances. Therefore, enhancing the model by introducing more constraints presents a promising direction for further work. Additionally, we intend to utilize reinforcement learning and other advanced techniques to develop more accurate load forecasting and user behavior modeling. Furthermore, we plan to explore modeling and control strategies for flexible loads to fully leverage their potential in peak shaving and frequency regulation.