Integrating Ocean Literacy Through a Locally Contextualized Dobble-like Card Game: An Exploratory Classroom Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives

- 1.

- To analyze how students engage, participate, and express emotional or cognitive responses during the implementation of the Marine Dobble activity in 1º ESO classrooms.

- 2.

- To identify the types of scientific vocabulary, conceptual understandings, and pro-environmental actions that emerge from group interactions throughout the reflective pauses.

- 3.

- To explore the contextual conditions—such as teacher involvement and classroom climate—that influence the feasibility and potential transferability of the activity to other educational settings.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Theoretical Principles: Environmental Education for Sustainability and Ocean Literacy

- 1.

- The Earth has one big ocean with many features.

- 2.

- The ocean and the life within it shape the Earth.

- 3.

- The ocean influences climate and weather.

- 4.

- The ocean makes the Earth habitable.

- 5.

- The ocean supports a great diversity of life and ecosystems.

- 6.

- The ocean and humans are inextricably interconnected.

- 7.

- The ocean is largely unexplored.

2.2. Gamification as an Active Methodology in Environmental Education Workshops

3. Methodology

3.1. Context and Participants

3.2. Design of the Educational Experience

3.3. Specific Competencies and Core Knowledge Addressed According to the LOMLOE

4. Results and Discussion

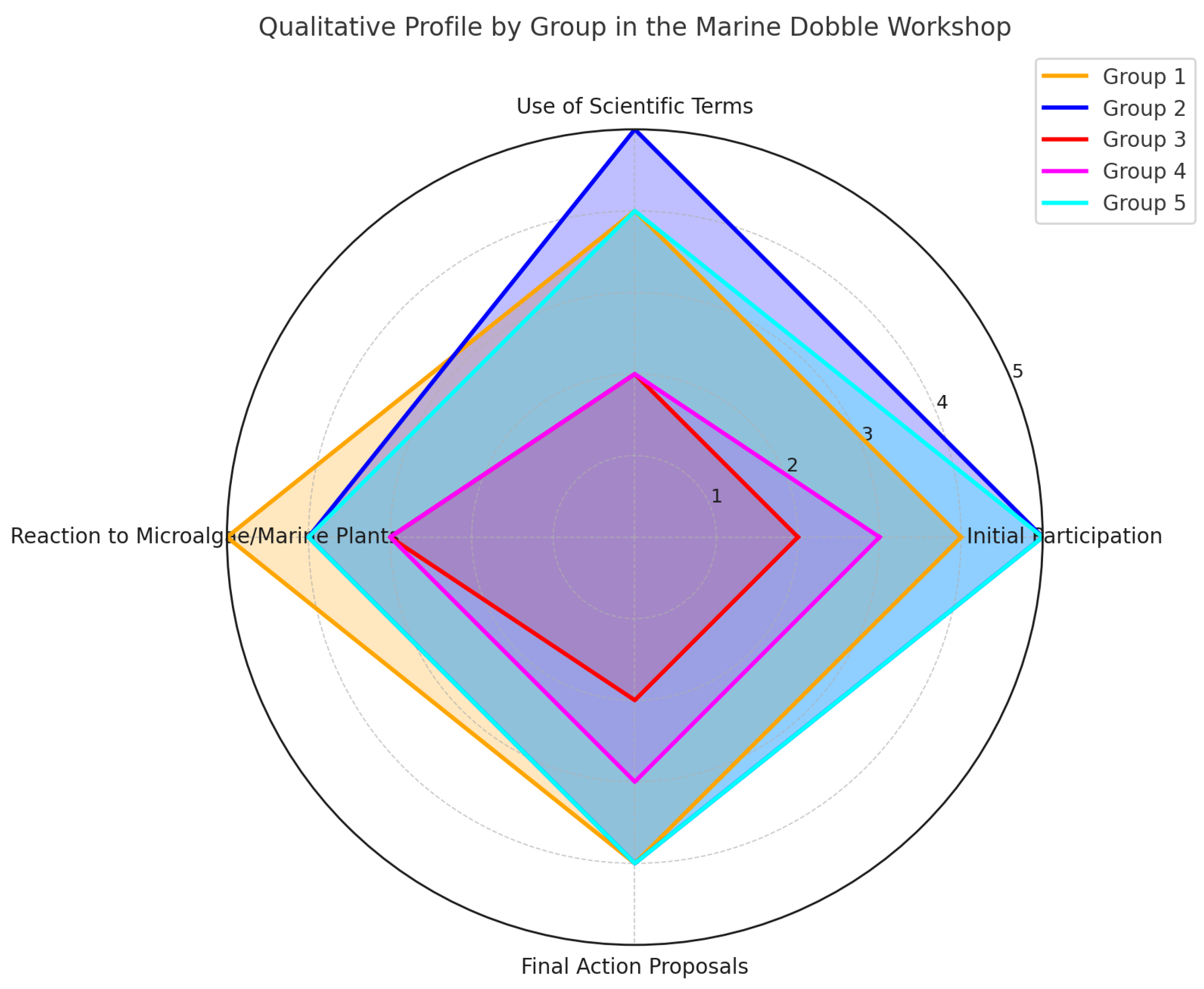

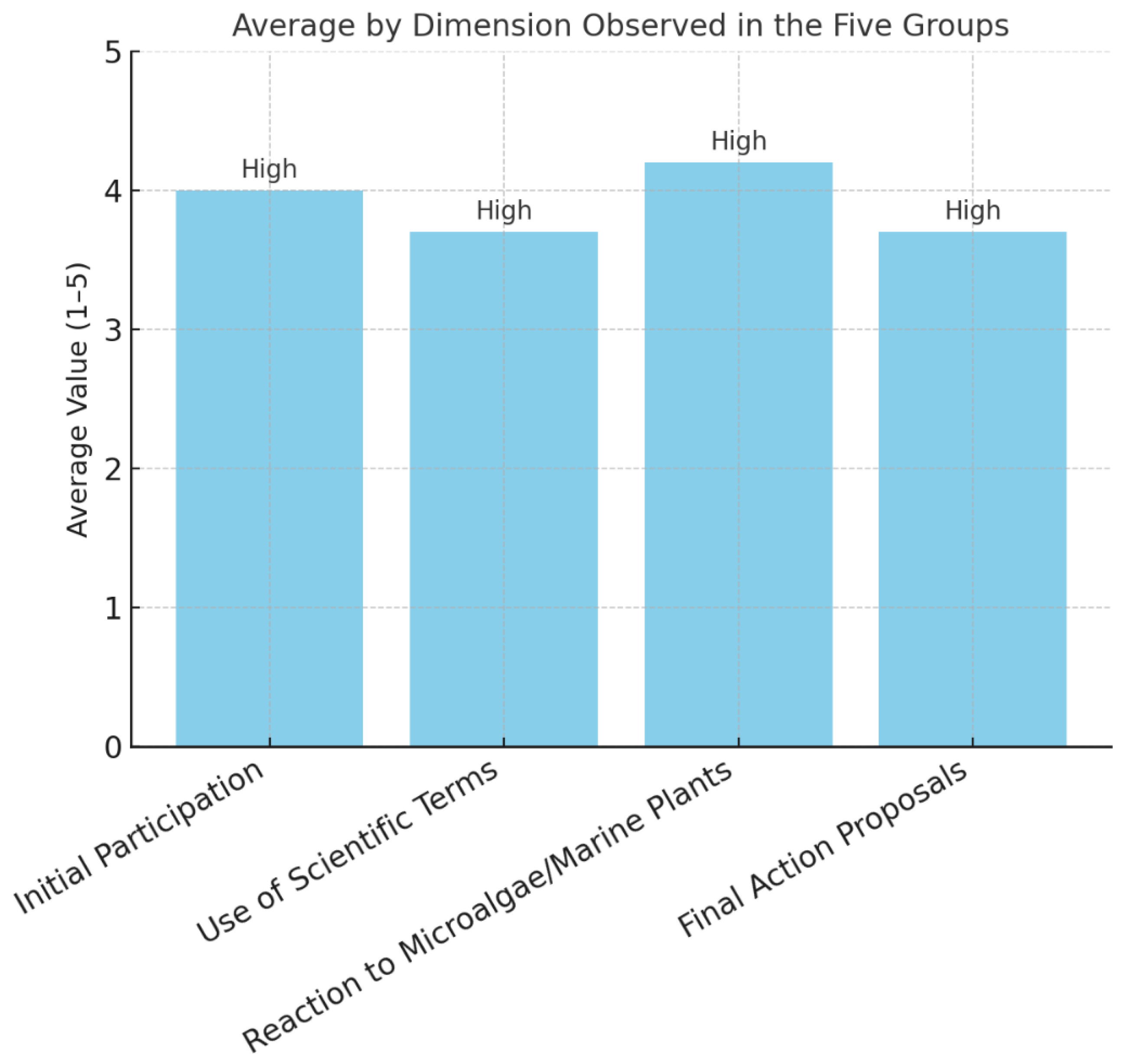

4.1. Observation Instrument

4.2. Start of the Workshop: Activation of Prior Ideas and Predisposition

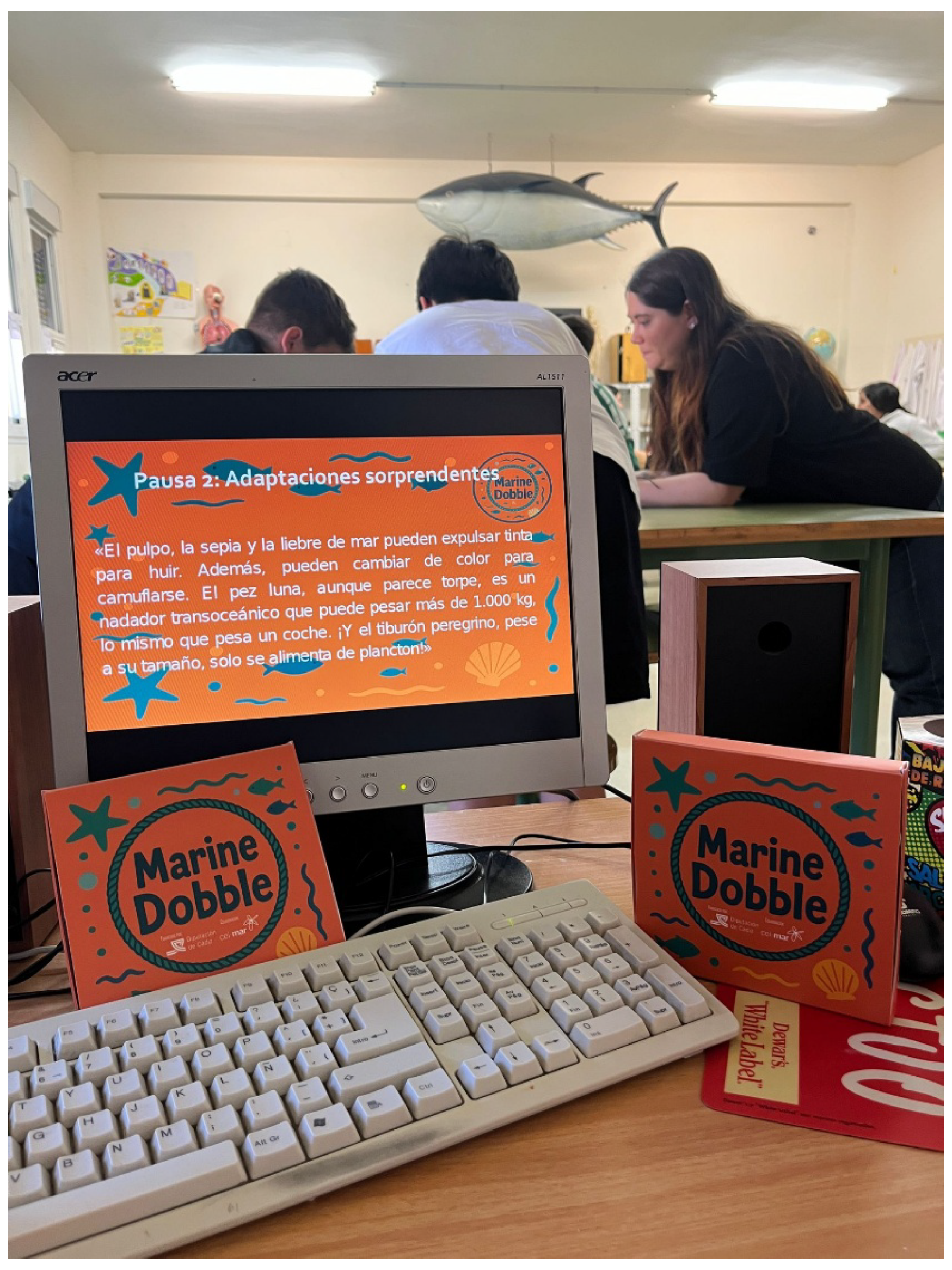

4.3. Game: Motivation, Interaction, and Connection with Content

4.4. Didactic Pauses: Wonder, Understanding, and Dialogue

- Pause 1: Marine Habitats

- Pause 2: Surprising Adaptations

- Pause 3: Did You Know…?

- Pause 4: Ocean Problems

- Pause 5: Commitment to the Ocean

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vilches, A.; Gil, D.; Cañal, P. La educación científica y el cambio global. Rev. Eureka Sobre Enseñanza Divulg. Las Cienc. 2010, 7, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara Herrero, M.; Bravo Torija, B.; Pérez Martín, D. Cultura oceánica y didáctica de las ciencias: Una revisión crítica. Rev. Eureka Sobre Enseñanza Divulg. Las Cienc. 2020, 17, 3403. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Contreras-Barraza, N.; Castillo, D.; Torres-Alcayaga, M.; Cornejo-Orellana, C. Bibliometric analysis on ocean literacy studies for marine conservation. Water 2023, 15, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilches, A.; Gil, D.; Cañal, P. Educación para la sostenibilidad: Un reto para la educación actual. Rev. Eureka Sobre Enseñanza Divulg. Las Cienc. 2008, 5, 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Menoyo, M. Educación para la sostenibilidad: Principios pedagógicos y didácticos. Rev. Int. Educ. Ambient. Cienc. 2018, 3, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Martín, D.; Bravo-Torija, B. Educación para la sostenibilidad en la escuela: Una propuesta de enfoque didáctico. Didácticas Específicas 2018, 19, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cava, F.; Schoedinger, S.; Strang, C.; Tuddenham, P. Ocean Literacy: The Essential Principles of Ocean Sciences K–12; NOAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Payne, D.; Marrero, M. Educating for Ocean Literacy: A How-To Guide for Effective Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Armario, M.; Brenes-Cuevas, M.C.; Ageitos-Prego, N.; Puig-Mauriz, B. Las orcas, ¿Pasan o se quedan? Alambique: Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales 2024, 118, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ageitos, N.; Puig, B.; López, A.; Ojeda-Romano, G.; Pintado, J. Desde las orcas hasta la vida marina en suspensión. Promover la cultura oceánica. In Pensar Científicamente. Problemas Sistémicos y Acción Crítica; Puig, B., Crujeiras-Pérez, B., Blanco-Anaya, P., Eds.; Graó: Barcelona, Spain, 2023; pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico. Plan de Acción de Educación Ambiental para la Sostenibilidad (PAEAS) 2021–2025; MITECO: Madrid, Spain, 2021.

- Mogollón, J.; Pujol, R.; Sabariego, M. Competencias para la sostenibilidad: Un marco de referencia en educación superior. Rev. Educ. Ambient. Sostenibilidad 2022, 2, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Río, J.; Méndez-Giménez, A. Metodologías activas y educación física: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Física Deporte 2020, 20, 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Torralba-Burrial, A.; Dopico, E. Promoting the Sustainability of Artisanal Fishing through Environmental Education with Game-Based Learning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Education for Sustainable Development: An Expert Review of Processes and Learning; UNESCO: París, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

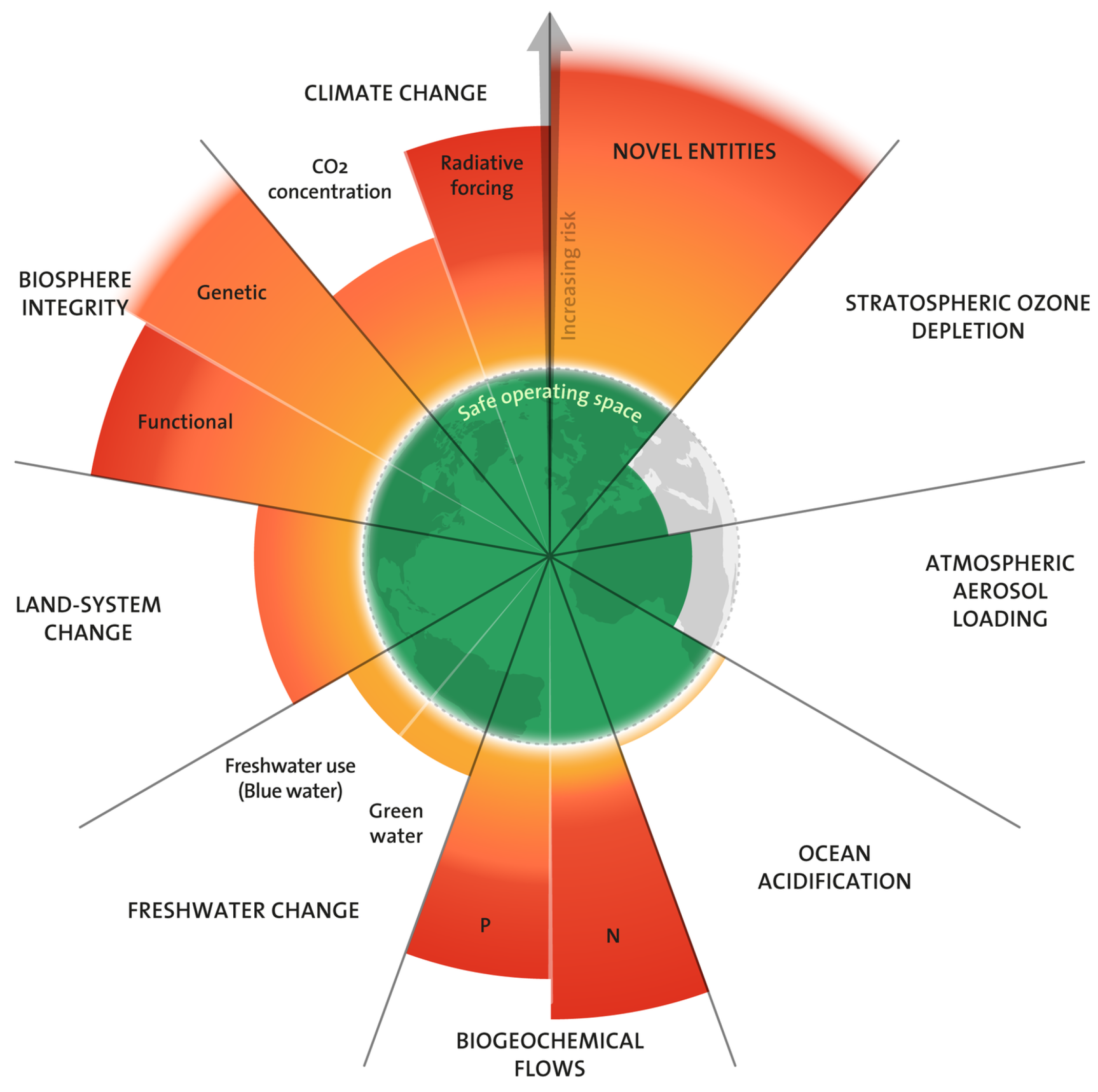

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, A.; Chapin, F.; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A. La educación ambiental en tiempos de crisis ecosocial. Rev. Univ. Educ. Ambient. 2010, 12, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Steffen, W.; Lucht, W.; Bendtsen, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Donges, J.F.; Drüke, M.; Fetzer, I.; Bala, G.; Von Bloh, W.; et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusher, A.; Hollman, P.; Mendoza-Hill, J. Microplastics in Fisheries and Aquaculture: Status of Knowledge on Their Occurrence and Implications for Aquatic Organisms and Food Safety; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 615; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides, A.; Cardona, R.; López, J. Estrategias didácticas activas en la enseñanza de las ciencias. Rev. Electron. Educ. Cienc. 2020, 15, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A. Beyond Unreasonable Doubt: Education and Learning for Socio-Ecological Sustainability in the Anthropocene; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNECE. Learning for the Future: Competences in Education for Sustainable Development; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorcia, J.; Orozco, L. Educación ambiental transformadora. Prax. Saber 2022, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Castillo, J. Estudio de los flujos de dispersión de los residuos plásticos en el Golfo de Cádiz. Rev. Eureka Sobre Enseñanza Divulg. Las Cienc. 2019, 16, 3501. [Google Scholar]

- España. Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de Diciembre, por la que se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación (LOMLOE); Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2020. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3/con (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zichermann, G.; Cunningham, C. Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, D. The Psychology of Meaningful Verbal Learning; Grune & Stratton: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, J. Learning, Creating, and Using Knowledge: Concept Maps as Facilitative Tools in Schools and Corporations; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Milanés, O.; Menezes, P.; Quellis, L. Educación ambiental transformadora. Rev. Pedagógica 2019, 21, 500–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lirussi, F.; Ziglio, E.; Curbelo Perez, D. One Health y las nuevas herramientas para promover la salud. Rev. Iberoam. Bioet. 2021, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2020 NOAA Science Report; NOAA Science Council: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020.

- Barboza, L.; Vethaak, A.; Lavorante, B.; Lundebye, A.; Guilhermino, L. Marine microplastic debris. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragón, L.; Brenes-Cuevas, C. A gamified teaching proposal using an escape box to explore marine plastic pollution. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Workshop Phase | Topics Worked | Didactic Intentions |

|---|---|---|

| Pause 1: Marine Habitats | Diversity of marine habitats and species distribution (seafloor, beaches, open waters). | Recognize the variety of marine ecosystems and their ecological importance. |

| Pause 2: Surprising Adaptations | Physiological and behavioral adaptations of species (camouflage, ink, filtration). | Appreciate the adaptive richness of marine organisms and their connection with the environment. |

| Pause 3: Did You Know…? | Scientific curiosities: distinctions between algae and plants, remarkable species, living fossils. | Foster wonder, scientific thinking, and interest in biodiversity. |

| Pause 4: Ocean Challenges | Environmental impacts: pollution, warming, threatened species, and plastics. | To understand the relationship between human activities and environmental degradation. |

| Pause 5: Commitment to the Ocean | Individual and collective commitment to ocean conservation from land. | To promote awareness and responsible action in addressing ocean challenges. |

| Stage of the Workshop | Guiding Questions | Main Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Beginning of the session | How do students react to the initial questions about marine animals and habitats? What prior ideas and everyday examples do they mention? | Level of participation and curiosity; type of examples provided; presence of misconceptions; use of everyday vs. scientific vocabulary; initial classroom climate. |

| Gameplay dynamics | How quickly do students understand the rules and dynamics of the game? How do they interact while playing? What difficulties arise when identifying species or habitats? | Engagement and emotional tone; cooperative vs. competitive interactions; negotiation of disagreements; difficulties identifying species; progression from generic to more precise terms. |

| Didactic pauses | How do students react to the scientific explanations? Which elements surprise them? Do they mention environmental problems or conservation issues? | Expressions of wonder; references to habitats and adaptations; reactions to scientific curiosities (e.g., marine plants, microalgae); awareness of environmental problems; types of conservation actions proposed. |

| Final reflections | What do students say they have learned or found most surprising? What actions do they suggest to protect the ocean? | Mention of newly learned species or concepts; explicit expressions of environmental concern; concreteness and feasibility of proposed actions; illustrative spontaneous comments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brenes-Cuevas, C.; Ruiz, L.; Garrido-Pérez, C. Integrating Ocean Literacy Through a Locally Contextualized Dobble-like Card Game: An Exploratory Classroom Implementation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310840

Brenes-Cuevas C, Ruiz L, Garrido-Pérez C. Integrating Ocean Literacy Through a Locally Contextualized Dobble-like Card Game: An Exploratory Classroom Implementation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310840

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrenes-Cuevas, Carmen, Lorena Ruiz, and Carmen Garrido-Pérez. 2025. "Integrating Ocean Literacy Through a Locally Contextualized Dobble-like Card Game: An Exploratory Classroom Implementation" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310840

APA StyleBrenes-Cuevas, C., Ruiz, L., & Garrido-Pérez, C. (2025). Integrating Ocean Literacy Through a Locally Contextualized Dobble-like Card Game: An Exploratory Classroom Implementation. Sustainability, 17(23), 10840. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310840