From Waste to Worth: Upcycling Piscindustrial Remnants into Mineral-Rich Preparations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Collection and Preparation of Fishbone Samples

2.3. Pre-Processing and Moisture Content Determination of Fishbone Samples

2.4. Total Ash Determination of Ground Fishbone Samples

2.5. Wet Digestion of Ground Fishbone Samples

2.6. Mineral Profiling of Ground Fishbone Samples

2.7. Manufacture of MMI Capsules from Ground Fishbone

2.8. Comparative Dissolution Studies of MMI Capsules and a Marketed Multi-Mineral Product

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Moisture Content and Total Ash Determination of Ground Fishbone Samples

3.2. Mineral Profiling of Ground Fishbone Samples

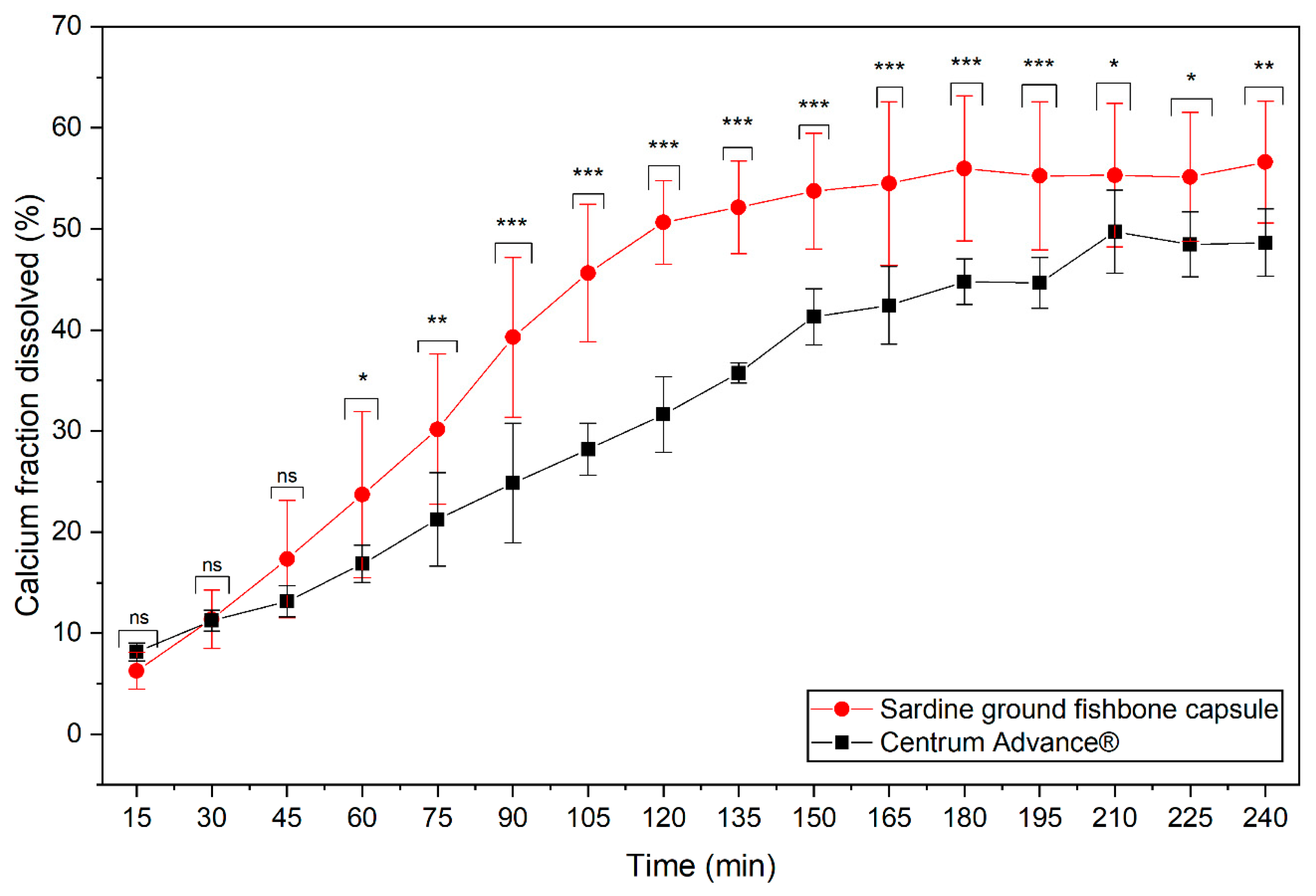

3.3. Manufacture and Comparative Dissolution Studies of MMI Capsules and a Marketed Multi-Mineral Product

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | American Chemical Society |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| °C | Degrees Celsius |

| CAGR | Compound annual growth rate |

| EU | European Union |

| g | Gram |

| kW | Kilowatt |

| L | Litre |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| LOQ | Limit of quantification |

| M | Molarity |

| mg | Milligram |

| min | Minute |

| mL | Millilitre |

| MMI | Multi-mineral ingredient |

| MPa | Megapascal |

| MP-AES | Microwave plasma atomic emission spectrometry |

| MΩ·cm | Megaohms-cm |

| n | Number of replicates |

| N | Normality |

| n.d. | No data |

| no. | Number |

| ns | Non-significant |

| p | Probability |

| pH | Hydrogen potential |

| ppb | Parts per billion |

| ppm | Parts per million |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| rpm | Rotations per minute |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| t | Time |

| µg | Microgram |

| % | Percentage |

References

- Richards, M.P.; Schulting, R.J. Touch not the fish: The Mesolithic-Neolithic change of diet and its significance. Antiquity 2006, 80, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R. Garum and Salsamenta: Production and Commerce in Materia Medica; Brill: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-González, R.; Teixeira Pereira, Z.G.; Ricoy-Casas, R.M. Governance of the circular economy in the canned fish industry: A case study from Spain. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 34, 103618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-González, R.; Pérez-Vas, R.; Pérez-Pérez, M.; Pereira, Z.G.T.; Puime-Guillén, F.; Ricoy-Casas, R.M. Resilience and adaptation: Galician canning fish industry evolution. Mar. Policy 2024, 163, 106087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, D.L. Canning of fish and seafood. In A Complete Course in Canning and Related Processes, 14th ed.; Featherstone, S., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 231–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-S.; Yang, S.-K.; Heu, M.-S. Component characteristics of cooked tuna bone as a food source. Korean J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2000, 33, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Toppe, J.; Albrektsen, S.; Hope, B.; Aksnes, A. Chemical composition, mineral content and amino acid and lipid profiles in bones from various fish species. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 146, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, T.; Thilsted, S.H.; Kongsbak, K.; Hansen, M. Whole small fish as a rich calcium source. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 83, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, A.; Esteve-Llorens, X.; González-García, S.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. Multi-product strategy to enhance the environmental profile of the canning industry towards circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais-Costa, A.J.; Marques, A.; Oliveira, H.; Goncalves, A.; Camacho, C.; Augusto, H.C.; Nunes, M.L. New Perspectives on Canned Fish Quality and Safety on the Road to Sustainability. Foods 2025, 14, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022.

- Canned Seafood Market Size, Share, Trends & Forecast. 2025. Available online: https://www.verifiedmarketresearch.com/product/canned-seafood-market/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Toppe, J.; Aksnes, A.; Hope, B.; Albrektsen, S. Inclusion of fish bone and crab by-products in diets for Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua. Aquaculture 2006, 253, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaset, B.; Julshamn, K.; Espe, M. Chemical composition and theoretical nutritional evaluation of the produced fractions from enzymic hydrolysis of salmon frames with Protamex™. Process Biochem. 2003, 38, 1747–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malde, M.K.; Graff, I.E.; Siljander-Rasi, H.; Venalainen, E.; Julshamn, K.; Pedersen, J.I.; Valaja, J. Fish bones—A highly available calcium source for growing pigs. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2010, 94, e66–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodehutscord, M.; Faust, M.; Hof, C. Digestibility of phosphorus in protein-rich ingredients for pig diets. Arch. Tierernaehr. 1997, 50, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.; Thilsted, S.H.; Sandström, B.; Kongsbak, K.; Larsen, T.; Jensen, M.; Sørensen, S.S. Calcium absorption from small soft-boned fish. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 1998, 12, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, I.; Santaella, M.; Ros, G.; Periago, M.J. Content and in vitro availability of Fe, Zn, Mg, Ca and P in homogenized fish-based weaning foods after bone addition. Food Chem. 1998, 63, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maktoof, A.A.; Elherarlla, R.J.; Ethaib, S. Identifying the nutritional composition of fish waste, bones, scales, and fins. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 871, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.B.; Jakobsen, J.; Jacobsen, C.; Sloth, J.J.; Ibarruri, J.; Bald, C.; Iñarra, B.; Bøknæs, N.; Sørensen, A.-D.M. Content and Bioaccessibility of Minerals and Proteins in Fish-Bone Containing Side-Streams from Seafood Industries. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairul, U.T.; Idris, N.I.M.; Shah, R.M.; Nawi, I.H.M.; Che Soh, N. Evaluation of Minerals Composition in Fish Bone Meal as Organic Fertilizer Development for Sustainable Environment. Curr. World Environ. 2025, 19, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemung, B.-O. Properties of tilapia bone powder and its calcium bioavailability based on transglutaminase assay. Int. J. Biosci. Biochem. Bioinform. 2013, 3, 306–309. [Google Scholar]

- Nemati, M.; Huda, N.; Ariffin, F. Development of calcium supplement from fish bone wastes of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) and characterization of nutritional quality. Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 2419–2426. [Google Scholar]

- Amitha, C.V.; Raju, I.P.; Lakshmisha, P.; Kumar, A.; Gajendra, A.S.; Pal, J. Nutritional Composition of Fish Bone Powder Extracted from Three different Fish Filleting Waste Boiling with Water and an Alkaline Media. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 2942–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Mendis, E. Bioactive compounds from marine processing byproducts—A review. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, S. Levels of Heavy Metals in Canned Bonito, Sardines, and Mackerel Produced in Turkey. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2010, 143, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosker, A.R.; Gundogdu, S.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Ayas, D.; Ozogul, F. Metal levels of canned fish sold in Türkiye: Health risk assessment. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1255857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- British Pharmacopoeia Commission. Appendix XII C. Consistency of Formulated Preparations; British Pharmacopoeia Commission: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- British Pharmacopoeia Commission. Appendix XII B. Dissolution; British Pharmacopoeia Commission: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 (Text with EEA relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2023, L199, 103–157.

- Bandarra, N.; Batista, I.; Nunes, M.L.; Empis, J.M. Seasonal variation in the chemical composition of horse-mackerel (Trachurus trachurus). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2001, 212, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmus, M. Evaluation of Nutritional and Mineral-Heavy Metal Contents of Horse Mackerel (Trachurus trachurus) in the Middle Black Sea in terms of Human Health. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 190, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, A.R.; Djinovic-Stojanovic, J.M.; Dordevic, D.S.; Relic, D.J.; Vranic, D.V.; Milijasevic, M.P.; Pezo, L.L. Levels of toxic elements in canned fish from the Serbian markets and their health risks assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 67, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J.J.; Jugdaohsingh, R.; Thompson, R.P.H. The regulation of mineral absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1999, 58, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sardine | Horse-Mackerel | Mackerel | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium (Ca) | mg/g | 170.47 ± 0.33 | 156.03 ± 1.25 | 131.03 ± 6.26 |

| Phosphorus (P) | mg/g | 86.07 ± 9.95 | 116.79 ± 9.43 | 90.84 ± 5.30 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | mg/g | 3.36 ± 0.07 | 3.42 ± 0.13 | 3.76 ± 0.11 |

| Iron (Fe) | µg/g | 147.01 ± 8.82 | 73.32 ± 38.81 | 147.23 ± 37.46 |

| Zinc (Zn) | µg/g | 111.69 ± 2.56 | 56.15 ± 7.68 | 76.08 ± 6.06 |

| Sodium (Na) | mg/g | 1.55 ± 0.08 | 2.64 ± 0.25 | 0.92 ± 0.03 |

| Potassium (K) | mg/g | 4.68 ± 0.06 | 2.09 ± 0.04 | 4.58 ± 0.04 |

| Copper (Cu) | µg/g | n.d. 1 | n.d. 2 | n.d. 1 |

| Lead (Pb) | µg/g | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 |

| Cadmium (Cd) | µg/g | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 |

| Selenium (Se) | mg/g | n.d. 1 | n.d. 2 | n.d. 1 |

| Chromium (Cr) | µg/g | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 |

| Tin (Sn) | µg/g | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 |

| Manganese (Mn) | µg/g | n.d. 2 | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 |

| Mercury (Hg) | mg/g | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 | n.d. 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopez Wagner, I.; Soria Valle, P.; Rajan, A.; d’Oliveira Martins, M.; Sil dos Santos, B. From Waste to Worth: Upcycling Piscindustrial Remnants into Mineral-Rich Preparations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310833

Lopez Wagner I, Soria Valle P, Rajan A, d’Oliveira Martins M, Sil dos Santos B. From Waste to Worth: Upcycling Piscindustrial Remnants into Mineral-Rich Preparations. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310833

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopez Wagner, Ileana, Priscila Soria Valle, Arun Rajan, Manuel d’Oliveira Martins, and Bruno Sil dos Santos. 2025. "From Waste to Worth: Upcycling Piscindustrial Remnants into Mineral-Rich Preparations" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310833

APA StyleLopez Wagner, I., Soria Valle, P., Rajan, A., d’Oliveira Martins, M., & Sil dos Santos, B. (2025). From Waste to Worth: Upcycling Piscindustrial Remnants into Mineral-Rich Preparations. Sustainability, 17(23), 10833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310833