Micro/Nanoplastics Alter Daphnia magna Life History by Disrupting Glucose Metabolism and Intestinal Structure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Experimental Design and Sample Collection

2.3. DNA Extraction of Intestinal Microbes from D. magna and 16S rRNA Fragment Sequencing

2.4. Observation of Daphnia magna Intestinal Status by Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.5. Data Processing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Changes in Fluorescence Intensity in D. magna

3.2. Effects of Microplastics on the Growth of D. magna

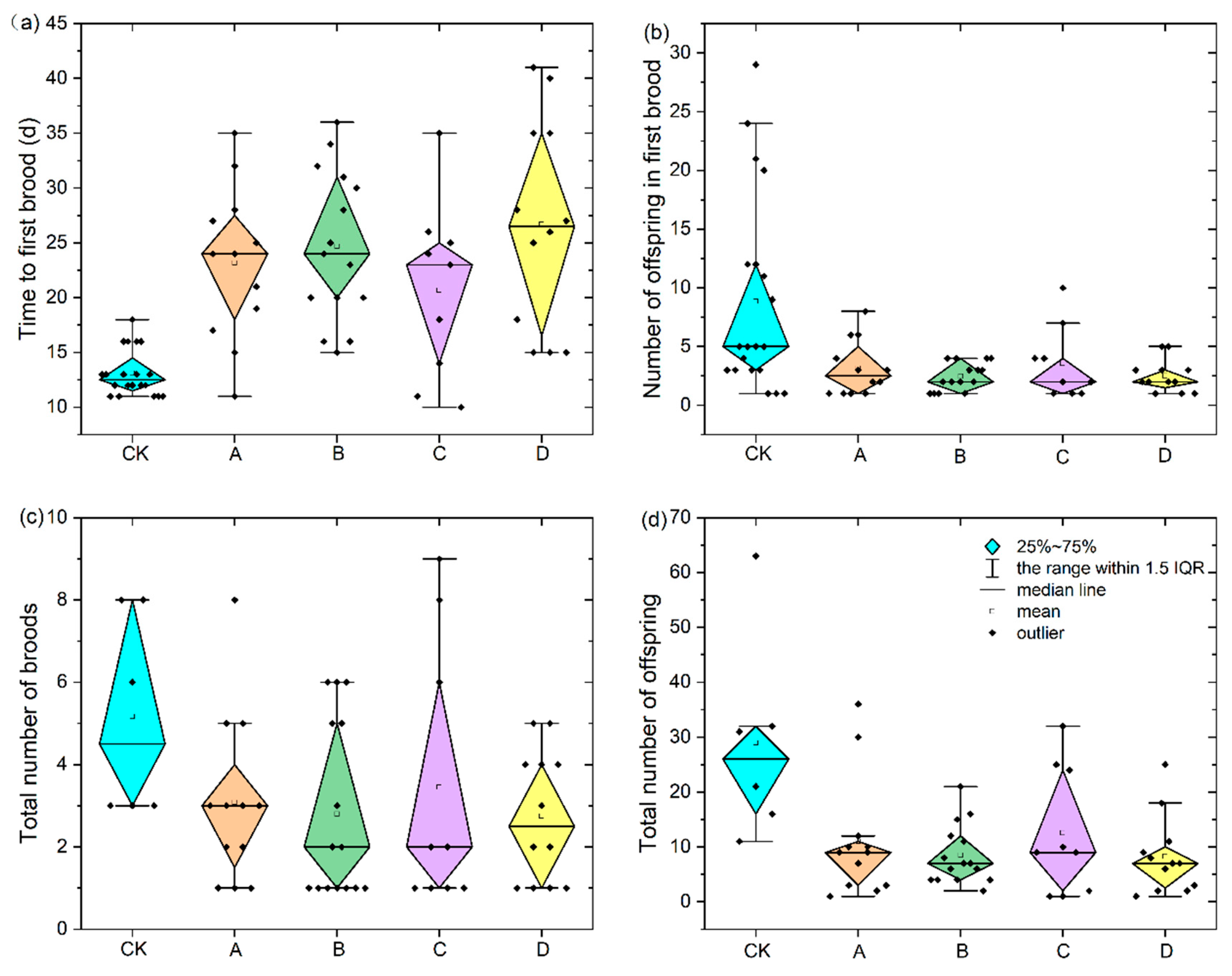

3.3. Effects of Microplastics on Offspring Development of D. magna

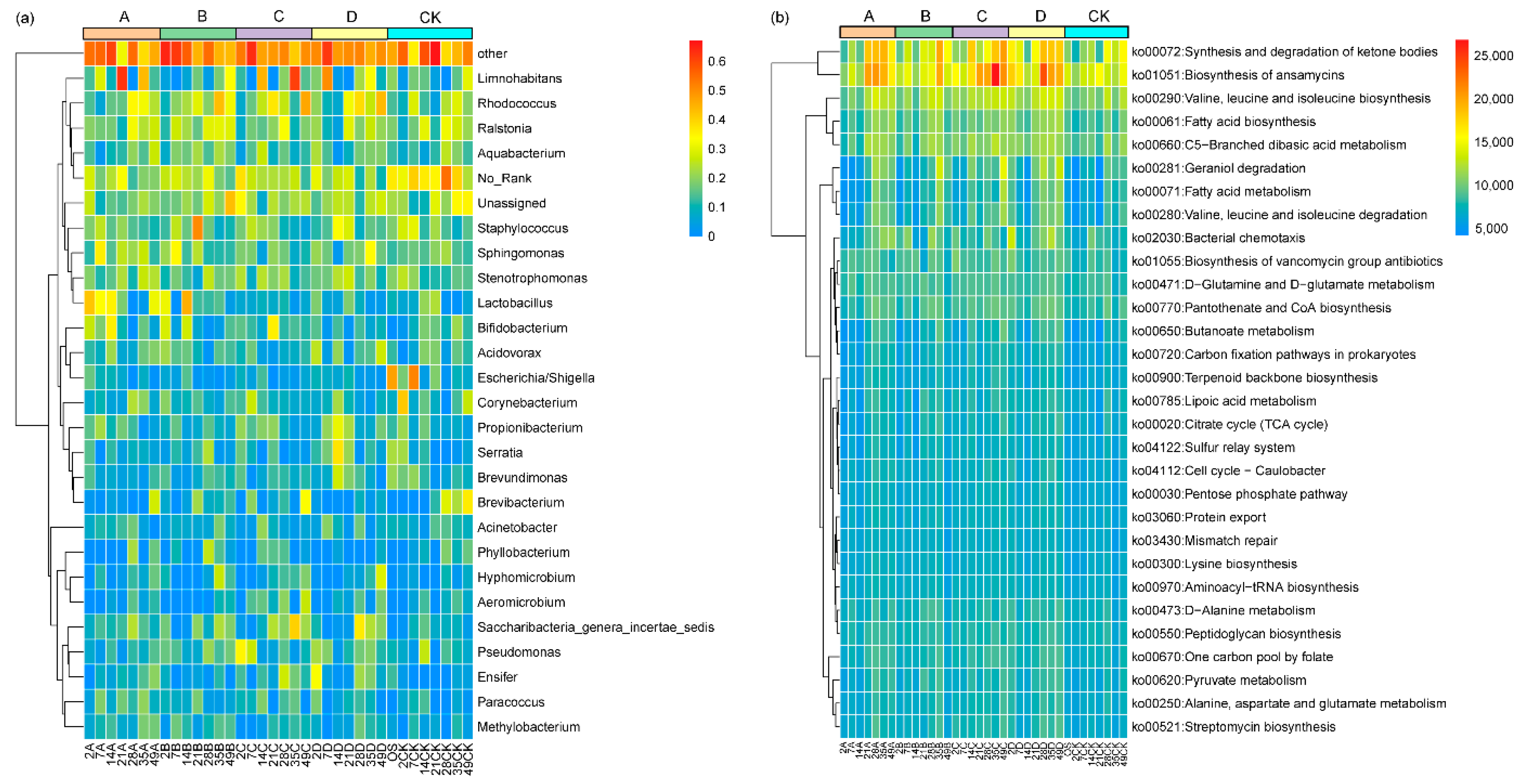

3.4. Effects of Microplastics on the Intestinal Microbiota of D. magna

3.5. Effects of Microplastics on the Intestinal Structure of D. magna

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jahnke, A.; Arp, H.P.H.; Escher, B.I.; Gewert, B.; Gorokhova, E.; Kuhnel, D.; Ogonowski, M.; Potthoff, A.; Rummel, C.; Schmitt-Jansen, M.; et al. Reducing uncertainty and confronting ignorance about the possible impacts of weathering plastic in the marine environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2017, 4, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Seijo, A.; Lourenço, J.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P.; da Costa, J.; Duarte, A.C.; Vala, H.; Pereira, R. Histopathological and molecular effects of microplastics in Eisenia andrei Bouché. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, C.; Jiang, H. Impacts of microplastic concentrations and sizes on the rheology properties of lake sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussarellu, R.; Suquet, M.; Thomas, Y.; Lambert, C.; Fabioux, C.; Pernet, M.E.J.; Goïc, N.L.; Quillien, V.; Mingant, C.; Epelboin, Y.; et al. Oyster reproduction is affected by exposure to polystyrene microplastics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirstein, I.V.; Kirmizi, S.; Wichels, A.; Garin-Fernandez, A.; Erler, R.; Löder, M.; Gerdts, G. Dangerous hitchhikers? Evidence for potentially pathogenic Vibrio Spp. on microplastic particles. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 120, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamichhane, G.; Acharya, A.; Marahatha, R.; Modi, B.; Paudel, R.; Adhikari, A.; Raut, B.K.; Aryal, S.; Parajuli, N. Microplastics in environment: Global concern, challenges, and controlling measures. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 4673–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorokhova, E.; Motiei, A.; El-Shehawy, R. Understanding biofilm formation in ecotoxicological assays with natural and anthropogenic particulates. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 632947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fackelmann, G.; Sommer, S. Microplastics and the gut microbiome: How chronically exposed species may suffer from gut dysbiosis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 143, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setälä, O.; Fleming-Lehtinen, V.; Lehtiniemi, M. Ingestion and transfer of microplastics in the planktonic food web. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 185, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, K.W. Who is eating whom? Morphology and feeding type determine the size relation between planktonic predators and their ideal prey. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 445, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Fileman, E.; Halsband, C.; Goodhead, R.; Moger, J.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastic ingestion by zooplankton. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 6646–6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, M.-P.; Beisner, B.E.; Maranger, R. Linking zooplankton communities to ecosystem functioning: Toward an effect trait framework. J. Plankton Res. 2017, 39, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, E.M.; Banks, H.T.; LeBlanc, G.A.; Flores, K.B. Continuous structured population models for Daphnia magna. Bull. Math. Biol. 2017, 79, 2627–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Yoshikawa, K.; Cross, J.S. Effects of nano/microplastics on the growth and reproduction of the microalgae, bacteria, fungi, and Daphnia magna in the microcosms. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 31, 103211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhao, S.; Li, F.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, A.; Li, F. Effects of microplastics on feeding behavior and antioxidant system of Daphnia magna. Res. Environ. Sci. 2021, 34, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemec, A.; Horvat, P.; Kunej, U.; Bele, M.; Kržan, A. Uptake and effects of microplastic textile fibers on freshwater crustacean Daphnia magna. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-H.; Chu, T.-W.; Kuo, C.-H.; Hong, M.-C.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Chen, B. Effects of microplastics on reproduction and growth of freshwater live feeds Daphnia magna. Fishes 2022, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaibachi, R.; Laird, W.B.; Stevens, F.; Callaghan, A. Impacts of polystyrene microplastics on Daphnia magna: A laboratory and a mesocosm study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, K.; Yu, B.; Li, D.; Gu, L.; Yang, Z. Increased food availability reducing the harmful effects of microplastics strongly depends on the size of microplastics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 437, 129375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelletti, M.; Presentato, A.; Piacenza, E.; Firrincieli, A.; Turner, R.J.; Zannoni, D. Biotechnology of Rhodococcus for the production of valuable compounds. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8567–8594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenscraft, A.; Kish, N.; Peay, K.; Boggs, C. No evidence that gut microbiota impose a net cost on their butterfly host. Mol. Ecol. 2019, 28, 1857–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz Pradella, J.G.; Ienczak, J.L.; Delgado, C.R.; Taciro, M.K. Carbon source pulsed feeding to attain high yield and high productivity in poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) production from soybean oil using Cupriavidus necator. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012, 34, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, B.; Piña, B.; Barata, C. Daphnia magna gut-specific transcriptomic responses to feeding inhibiting chemicals and food limitation. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 2510–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, B.; Rivetti, C.; Rosenkranz, P.; Navas, J.M.; Barata, C. Effects of nanoparticles of TiO2 on food depletion and life-history responses of Daphnia magna. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 130–131, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo, M.P.; Vila-Costa, M.; Barata, C. Micro-bioplastic impact on gut microbiome, cephalic transcription and cognitive function in the aquatic invertebrate Daphnia magna. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, A.; Wang, Y.; Feng, S.; Xue, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Jing, Z.; Xie, J. Microplastics induce human kidney development retardation through ATP-mediated glucose metabolism rewiring. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 486, 137002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wan, X.; Feng, Y.; Xu, H.; Nie, P.; Fu, F. Polystyrene microplastics disturb maternal glucose homeostasis and induce adverse pregnancy outcomes. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 279, 116492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wei, F.; Qiu, S.; Xing, B.; Hou, J. Polystyrene microplastics trigger adiposity in mice by remodeling gut microbiota and boosting fatty acid synthesis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 890, 164297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, I.; Jordão, R.; Piña, B.; Barata, C. Time-dependent transcriptomic responses of Daphnia magna exposed to metabolic disruptors that enhanced storage lipid accumulation. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, I.; Jordão, R.; Casas, J.; Barata, C. Allocation of glycerolipids and glycerophospholipids from adults to eggs in Daphnia magna: Perturbations by compounds that enhance lipid droplet accumulation. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 1702–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.O.; Cressler, C.E. Characterization of key bacterial species in the Daphnia magna microbiota using shotgun metagenomics. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, D.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Tan, S.; Xiang, M.; Li, T.; Yu, Y. Research progress on toxic effects and mechanisms of microplastics in Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Chem. 2023, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, S.; Yamasaki, M.; Fukui, T. Degradation of acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase, a ketone body-utilizing enzyme, by legumain in the mouse kidney. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 453, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Yang, D.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Fang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, J. Effects of microplastics on the growth and structure of the mouse small intestine. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2020, 39, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Gao, R.-Y.; Wang, Z.-J.; Shao, Q.-Q.; Hu, Y.-W.; Jia, H.-B.; Liu, X.-J.; Dong, F.-Q.; Fu, L.-M.; Zhang, J.-P. Daphnia magna uptake and excretion of luminescence-labelled polystyrene nanoparticle as visualized by high sensitivity real-time optical imaging. Chemosphere 2023, 326, 138341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sequencing Region | Primer Name | Primer Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 16S-V3V4 | 341F | CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG |

| 805R | GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, B.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, H.-M. Micro/Nanoplastics Alter Daphnia magna Life History by Disrupting Glucose Metabolism and Intestinal Structure. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310728

Zhao B, Zhang C, Wang C, Zhao H-M. Micro/Nanoplastics Alter Daphnia magna Life History by Disrupting Glucose Metabolism and Intestinal Structure. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310728

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Biying, Chaoyang Zhang, Chunliu Wang, and Hai-Ming Zhao. 2025. "Micro/Nanoplastics Alter Daphnia magna Life History by Disrupting Glucose Metabolism and Intestinal Structure" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310728

APA StyleZhao, B., Zhang, C., Wang, C., & Zhao, H.-M. (2025). Micro/Nanoplastics Alter Daphnia magna Life History by Disrupting Glucose Metabolism and Intestinal Structure. Sustainability, 17(23), 10728. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310728