Points of Entry for Enhancing Policymakers’ Capacity to Develop Green Economy Agenda-Setting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

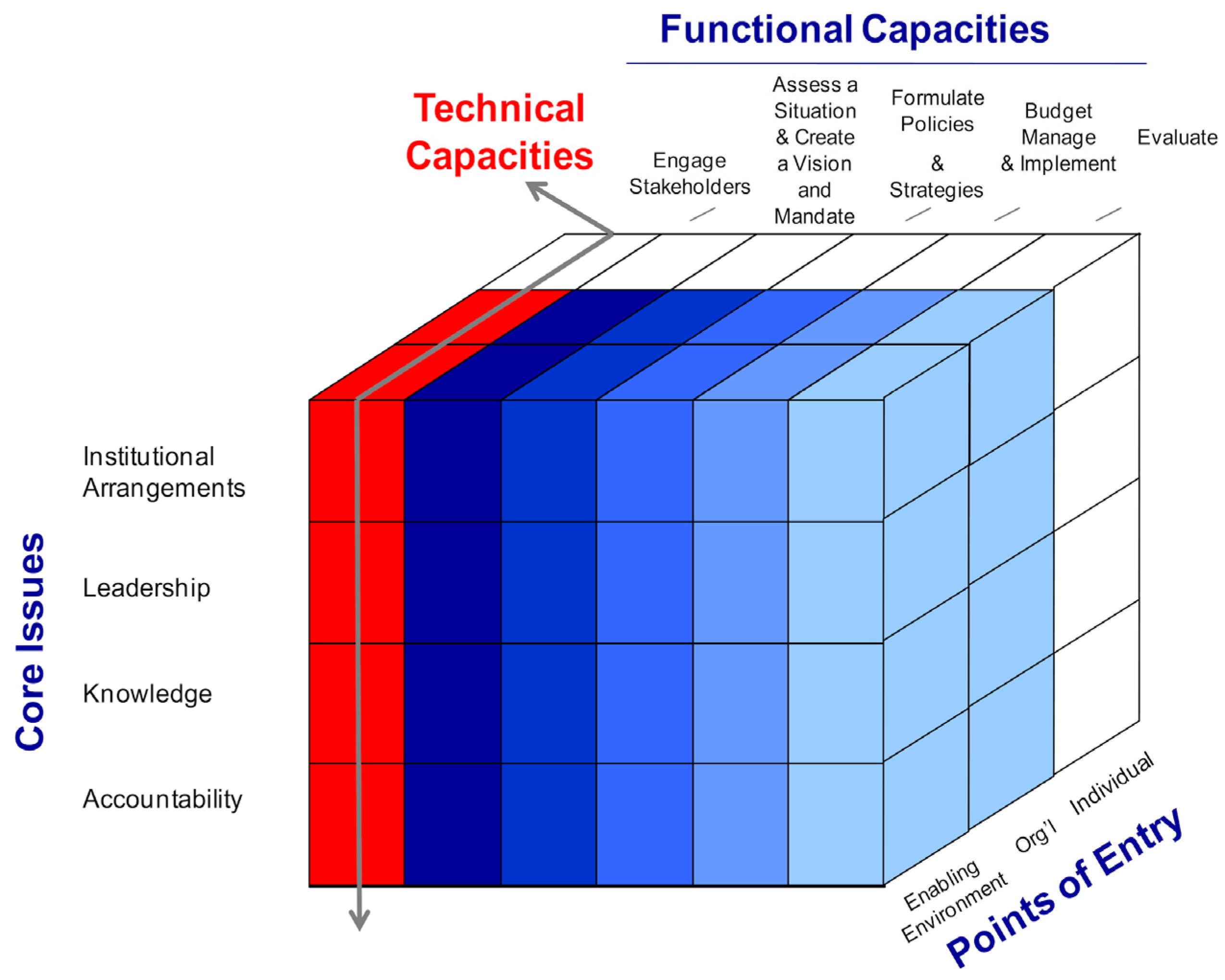

2.1. Conceptual Framework and Research Design

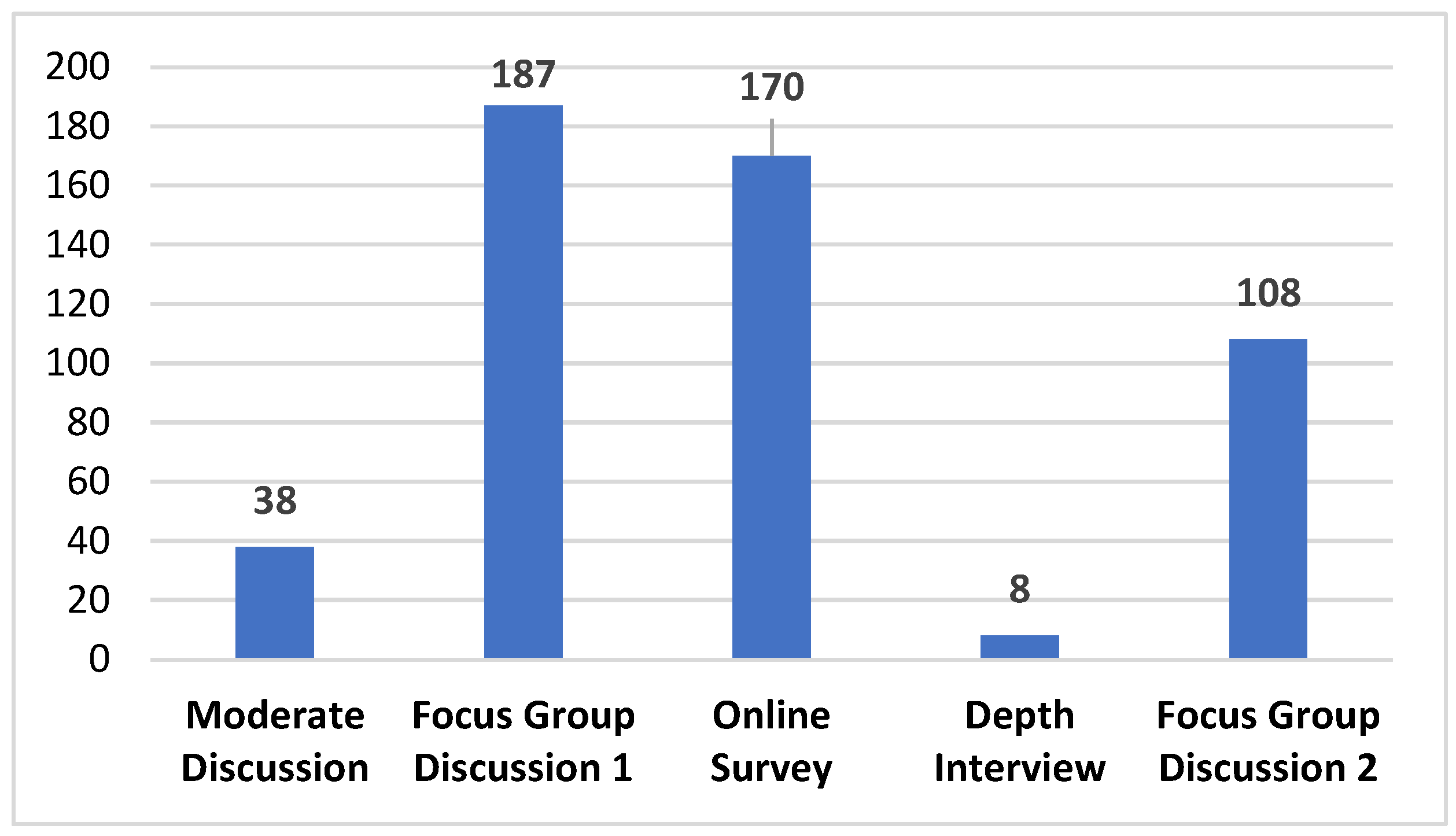

2.2. Data Collection and Stakeholder Engagement

2.2.1. Process of Stakeholder Engagement

2.2.2. Participant Selection and Sample Structure Justification

2.2.3. Measurement and Construction of Variables

2.3. Ordinal Regression Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

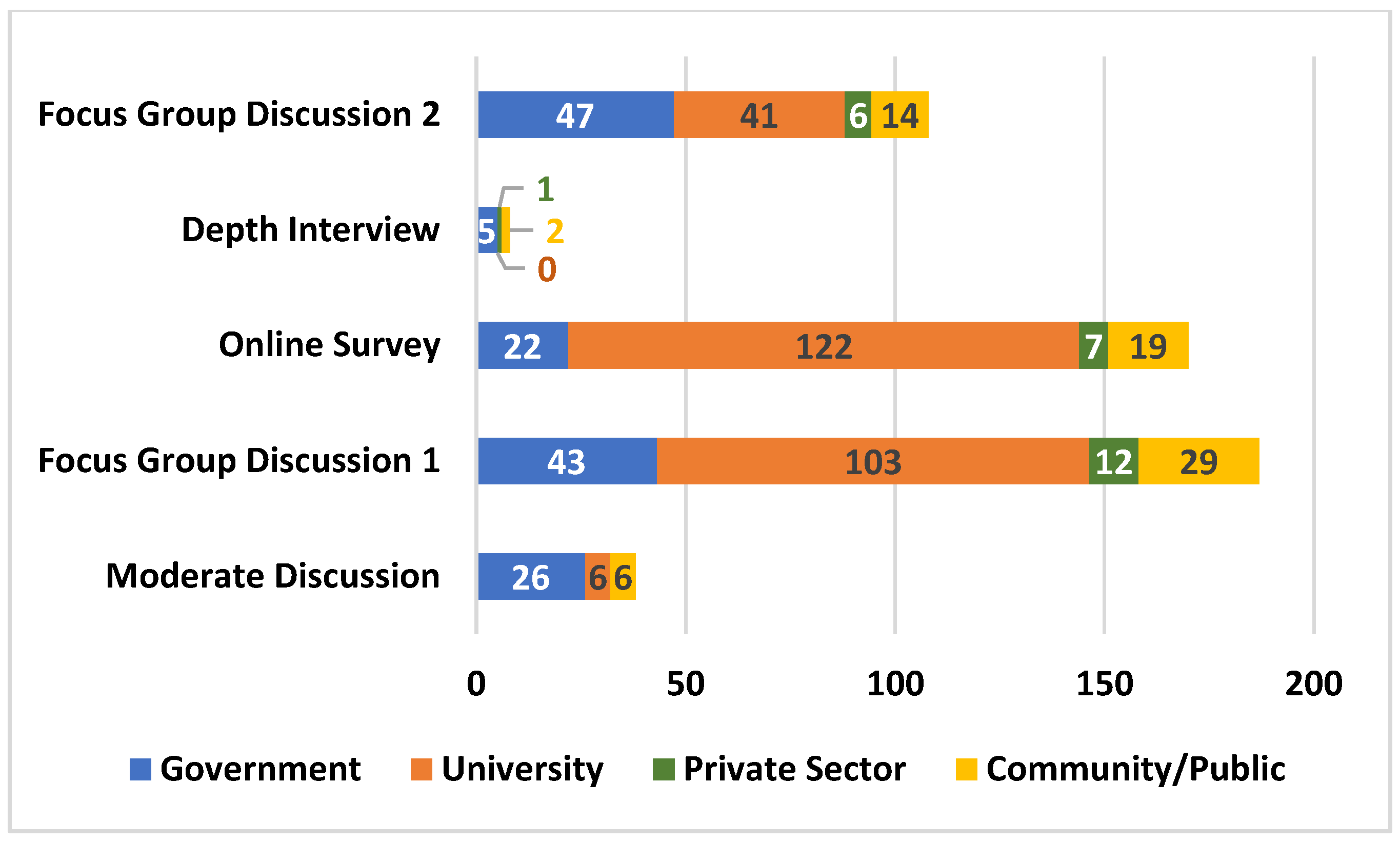

3.1. Demographic Data

3.1.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Institution

3.1.2. Demographics of Participants in Education and Training Programs

3.2. Competency Gaps, Needs, Framework, and Intervention in Green Economy Learning and Policy

3.2.1. Step 1: Defining the Policy Action Landscape Based on LCDI Interventions

3.2.2. Step 2: Mapping Competencies to Policy Actions

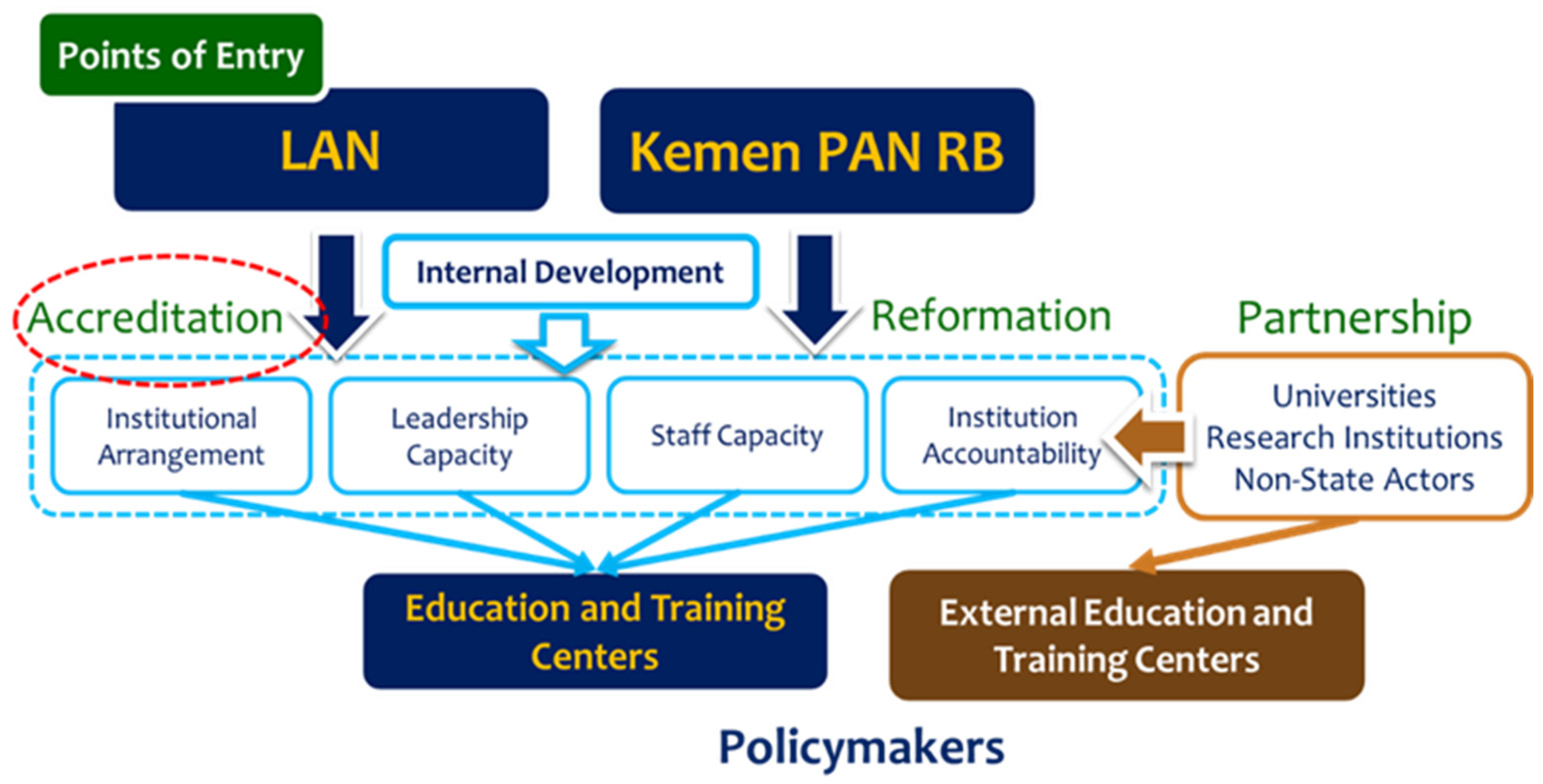

3.3. Opportunities and Challenges in Enhancing Institutional Capacity and Reform

3.4. Influence of Factors on Policymakers’ Competency Levels

3.4.1. Influence of the Main Target of Competency on Institutional Characteristics

3.4.2. Influence of the Main Competency Target on Education and Training Programs

3.5. International Comparative Perspective on Green Political Capabilities

3.5.1. Contrast with the European Union: Supranational Institutions’ Power and Regulatory Cohesion

3.5.2. Lessons from Latin America

4. Conclusions

4.1. Limitations of the Study

4.2. Policy Recommendations and Future Research Directions

4.2.1. Short-Term Actionable Steps

- Integrating Green Competencies into Accreditation Standards through the National Institute of Public Administration (LAN). This intervention leverages LAN’s pivotal role as the national accreditor to systemically embed green economy principles. While administratively feasible, this recommendation requires modest additional funding for curriculum development and strong coordination between LAN and line ministries to ensure adoption.

- Implementation of a Tiered and Problem-Oriented Training Approach. Capacity-building must be tailored to specific institutional roles. Given existing training structures, this approach is feasible in the short term with adjustments in training design rather than entirely new funding streams.

4.2.2. Long-Term Strategies

- Aligning the Green Economy with Bureaucratic Reform (KemenPANRB). This reform should explicitly integrate green economy competencies into civil service performance appraisals and promotion criteria. However, feasibility depends on political buy-in from senior leadership and overcoming institutional resistance to change. Without political endorsement, reforms risk being symbolic rather than substantive.

- Securing sustainable funding mechanisms. Embedding green training into accreditation and bureaucratic reforms will require stable long-term financing, potentially from climate funds, donor agencies, or earmarked state budget lines. Ensuring funding continuity is critical to prevent reforms from stalling.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAPPENAS | Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional (National Development Planning Agency) |

| FGD | Focus Group Discussion |

| GELA | Green Economy Learning Assessment |

| GGGI | Global Green Growth Institute |

| Kemen PANRB | Kementerian Pemberdayaan Aparatur Negara dan Reformasi Birokrasi (Ministry of Administrative and Bureaucratic Reform) |

| LAN | Lembaga Administrasi Negara (State Administration Agency) |

| LCDI | Low Carbon Development Indonesia |

| MER | Monitoring, Evaluating, and Reporting |

| MRV | Measurement, Reporting, and Verification |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| RPJMN | Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional (National Mid-Term Development Plan) |

| SKKNI | Standar Kompetensi Kerja Nasional Indonesia (Indonesia’s National Qualification Framework) |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

References

- Bailey, D.H.; Borwein, J.M.; Caprotti, O.; Martin, U.; Salvy, B.; Taufer, M. Opportunities and Challenges in 21st Century Mathematical Computation: ICERM Workshop Report; Institute for Computational and Experimental Research in Mathematics (ICERM): Providence, RI, USA, 2014; 18p, Available online: https://www.davidhbailey.com/dhbpapers/ICERM-2014.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Kowalska-Styczeń, A.; Bublyk, M.; Lytvyn, V. Green Innovative Economy Remodeling Based on Economic Complexity. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.; Randers, J.; Meadows, D. Limits to Growth-The 30 Year Update; Earthscan: London, UK, 2006; 363p, Available online: https://www.peakoilindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Limits-to-Growth-updated.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Jackson, T.; Victor, P. Productivity and Work in the ‘Green Economy’: Some Theoretical Reflections and Empirical Tests. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgeson, L.; Maslin, M.; Poessinouw, M. The Global Green Economy: A Review of Concepts, Definitions, Measurement Methodologies and Their Interactions. Geo 2017, 4, e00036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, United Nations. 2018. Available online: https://www.undp.org/ukraine/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Antkowiak, T.M. A “Dignified Life” and the Resurgence of Social Rights. Northwest. J. Hum. Rights 2020, 18, 1–52. Available online: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol18/iss1/1 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Davies, A.R. Cleantech Clusters: Transformational Assemblages for a Just, Green Economy or Just Business as Usual? Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealy, P.; Teytelboym, A. Economic Complexity and the Green Economy. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 103948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiadi, Y.; Sari, R.F.; Herdiansyah, H.; Hasibuan, H.S.; Lim, T.H. Developing DPSIR Framework for Managing Climate Change in Urban Areas: A Case Study in Jakarta, Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi, T. Review of Energy and Climate Policy Developments in Japan before and after Fukushima. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 1320–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiritu, S.W.; Engola, M.K. The Effectiveness of Feed-in-Tariff Policy in Promoting Power Generation from Renewable Energy in Kenya. Renew. Energy 2020, 161, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Hazell, P.; Haque, T. Targeting Public Investments by Agro-Ecological Zone to Achieve Growth and Poverty Alleviation Goals in Rural India. Food Policy 2000, 25, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovitch, J. Innovative Land Use and Public Transport Policy. Land Use Policy 1996, 13, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Enhanced Nationally Determined Contribution Republic of Indonesia; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2022; 47p, Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-09/23.09.2022_Enhanced%20NDC%20Indonesia.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Verma, S.; Kandpal, D. Green Economy and Sustainable Development. In Environmental Sustainability and Economy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, L.; Setyowati, A.B. Toward a Socially Just Transition to Low Carbon Development: The Case of Indonesia. Asian Aff. 2020, 51, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mouallem, L.; Analoui, F. The Need for Capacity Building in Human Resource Management Related Issues: A Case Study from the Middle East (Lebanon). In Proceedings of the 1st Mediterranean Interdisciplinary Forum on Social Sciences and Humanities, Beirut, Lebanon, 23–26 April 2014; pp. 245–254. Available online: https://eujournal.org/index.php/esj/article/view/3642 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Nouvan, R. Transforming Financial Systems for Sustainability: The Role of Green Financing in Social-Environmental Progress and Economic Resilience. EcoProfit Sustain. Environ. Bus. 2025, 3, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–520. [Google Scholar]

- Analoui, F.; Danquah, J.K. Critical Capacity Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Capacity Assessment Methodology User’s Guide; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2008; 76p, Available online: https://www.undp.org/publications/undp-capacity-assessment-methodology (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Rietig, K.; Dupont, C. Presidential Leadership Styles and Institutional Capacity for Climate Policy Integration in the European Commission. Policy Soc. 2021, 40, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinusa, S.O.; Wehn, U. Institutional Dynamics in National Strategy Development: A Case Study of the Capacity Development Strategy of Uganda’s Water and Environment Sector. Water Policy 2016, 18, 1174–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanasreh, E.; Moles, R.; Chen, T.F. Evaluation of Methods Used for Estimating Content Validity. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1–752. [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh, P. Regression Models for Ordinal Data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1980, 42, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murga-Menoyo, M. Learning for a Sustainable Economy: Teaching of Green Competencies in the University. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2974–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Ruano, J.; Segovia Sarmiento, J. Ecological Economics Foundations to Improve Environmental Education Practices: Designing Regenerative Cultures. World Futures 2022, 78, 456–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunny, F.A.; Jeronen, E.; Lan, J. Influential Theories of Economics in Shaping Sustainable Development Concepts. Adm. Sci. 2024, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalabrino, C.; Navarrete Salvador, A.; Oliva Martínez, J.M. A Theoretical Framework to Address Education for Sustainability for an Earlier Transition to a Just, Low Carbon and Circular Economy. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 735–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikal, R.; Firdaus, T.; Herdiansyah, H.; Chairunnisa, R.S. Urban Planning Policies and Architectural Design for Sustainable Food Security: A Case Study of Smart Cities in Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitjriyah, A.R.; Dwiputri, I.N. The Impact of Green Finance, Trade Openness, and Fossil Fuel Subsidies on Renewable Energy Consumption: A Global and Asia-Pacific Perspective. J. Environ. Sci. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 8, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buseth, J.T. Narrating Green Economies in the Global South. Forum Dev. Stud. 2021, 48, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugoua, E.; Dumas, M. Green Product Innovation in Industrial Networks: A Theoretical Model. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2021, 107, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karydas, C.; Zhang, L. Green Tax Reform, Endogenous Innovation and the Growth Dividend. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 97, 158–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidt, T.S. Green Taxes: Refunding Rules and Lobbying. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2010, 60, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufan, B.A.; Maqvira. Community Development for UMKM on Improving Financial Inclusion. J. Econ. Bus. Account. Res. 2025, 2, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiani, H.; Valennia, R.; Rusni, N.K. Nickel Export Ban Policy in Indonesia—A Path to Sustainable Economic Development? EcoProfit Sustain. Environ. Bus. 2024, 1, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, E.M.; Lee, J.M. When Do Environmental Regulations Backfire? Onsite Industrial Electricity Generation, Energy Efficiency and Policy Instruments. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 96, 174–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, S.M.; Harrison, G.W.; Hughes, C.E.; Rutström, E.E. Virtual Experiments and Environmental Policy. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2009, 57, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, B.; Wehn, U. Capacity Development Evaluation: The Challenge of the Results Agenda and Measuring Return on Investment in the Global South. World Dev. 2016, 79, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, S.; Putra, R.P.; Saragih, I.M.N.; Ranasti, N. Circular Economy Transition through Community-Based Ecopreneurship Empowerment Model: Reconstructing the Environmental Care Community. EcoProfit Sustain. Environ. Bus. 2025, 3, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, D.; Yagüe-Blanco, J.L.; Escobar, J. Capacity Development Strategy Empowering the Decentralized Governments of Ecuador towards Local Climate Action. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 125320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domorenok, E.; Graziano, P.; Polverari, L. Introduction: Policy Integration and Institutional Capacity: Theoretical, Conceptual and Empirical Challenges. Policy Soc. 2021, 40, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Indonesia. Law No. 5 of 2014 Concerning the State Civil Apparatus; Database Peraturan BPK: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014; Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/38580/uu-no-5-tahun-2014 (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- President of the Republic of Indonesia. Presidential Regulation No. 81 of 2010 Concerning the Grand Design of Bureaucratic Reform 2010–2025; Database Peraturan BPK: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2010; Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/40398/perpres-no-81-tahun-2010 (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Abdenur, A.E.; Da Fonseca, J.M.E.M. The North’s Growing Role in South–South Cooperation: Keeping the Foothold. Third World Q. 2013, 34, 1475–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm Olsen, K. Why Planned Interventions for Capacity Development in the Environment Often Fail: A Critical Review of Mainstream. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2006, 36, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Green Growth Institute. Review of GGGI Programme in Indonesia (2012–2017); The Global Green Growth Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018; pp. 1–48. Available online: https://gggi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Norway-2018-mid-term-evaluation-of-GGGI-Indonesia-Final-report.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 1–752. [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis, J.; Bendahan, S.; Jacquart, P.; Lalive, R. On Making Causal Claims: A Review and Recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 1086–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, S.E.; Pérez-Liñán, A.; Seligson, M.A. The Effects of U.S. Foreign Assistance on Democracy Building, 1990–2003. World Politics 2007, 59, 404–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–290. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. The European Green Deal to Be the First Climate-Neutral Continent; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/story-von-der-leyen-commission/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- European Union. European Commission: What Does the Commission Do? European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://european-union.europa.eu/institutions-law-budget/institutions-and-bodies/search-all-eu-institutions-and-bodies/european-commission_en (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Sari, A.P.; Ramdani, D.; Agustina, P.A. Growing Strong, Growing Green, Growing Renewables: Tripling Renewables and Doubling the Pace of Efficiency Improvement by 2030 in Indonesia; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2024; Available online: https://cgs.umd.edu/research-impact/publications/growing-strong-growing-green-growing-renewables-tripling-renewables (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Sovacool, B.K. Energy Policymaking in Denmark: Implications for Global Energy Security and Sustainability. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H. Renewable Energy Systems: A Smart Energy Systems Approach to the Choice and Modeling of Fully Decarbonized Societies, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 1–398. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson, S.; Lauber, V. The Politics and Policy of Energy System Transformation—Explaining the German Diffusion of Renewable Energy Technology. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Hong, S. An Offshore Energy Innovation Strategy to Implement the Korean Green New Deal. Korea Inst. Ind. Econ. Trade 2023, 269, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resosudarmo, B.P.; Rezki, J.F.; Effendi, Y. Prospects of Energy Transition in Indonesia. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2023, 59, 149–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiola, S. Payments for Environmental Services in Costa Rica. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, L.; Fearnside, P.M. Brazil’s New President and ‘Ruralists’ Threaten Amazonia’s Environment, Traditional Peoples and the Global Climate. Environ. Conserv. 2019, 46, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalope, D.; Reynolds, C.; Ganti, G.; Welder, L.; Fyson, C.; Mainu, M.; Hare, B. Renewable Energy Transition in Sub-Saharan Africa; Climate Analytics: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–65. Available online: https://ca1-clm.edcdn.com/assets/renewable_energy_transition_in_sub-saharan_africa.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

| Variable Type | Number of Items | Measurement Scale | Justification for Scale Choice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | 1 | 5-point Likert Scale (1 = Very Low Priority to 5 = Very High Priority) | To gauge the perceived urgency and commitment towards capacity development, capturing degrees of opinion that a simple yes/no question could not |

| Independent Variables | 17 | 5-point Likert Scale (1 = Very Low Priority to 5 = Very High Priority) | To measure the level of agreement or disagreement with statements about influencing factors, providing interval-level data for robust statistical analysis like ordinal regression |

| Item | Response | Frequency | Perc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Institution | Government/Legislative | 22 | 12.94 |

| University | 122 | 71.76 | |

| Private Sector | 7 | 4.12 | |

| Community/NGO/Media | 19 | 11.18 | |

| The Focus Area of the Education and Training Program | Forestry and Peatland | 54 | 18.31 |

| Agriculture | 52 | 17.63 | |

| Energy | 42 | 14.24 | |

| Industry | 30 | 10.17 | |

| Waste | 58 | 19.66 | |

| Blue Carbon/Mangrove | 38 | 12.88 | |

| Others | 21 | 7.12 | |

| Target Audience | National leaders/legislators | 58 | 16.91 |

| The Civil Servant Apparatus | 60 | 17.49 | |

| Private sector | 51 | 14.87 | |

| Community/NGO/Media | 61 | 17.78 | |

| Academician/Researcher | 113 | 32.94 |

| Item | Response | Frequency | Perc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Program relevant to the Green Economy | Green economy-based program | 52 | 30.6 |

| Integrated program including the Green Economy | 118 | 69.4 | |

| Not relevant to the Green Economy | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Program relevant to LCDI Framework | LCDI-based program | 56 | 32.94 |

| LCDI and the internal integrated program | 100 | 58.82 | |

| Non-LCDI/cooperation/Internal-based program | 14 | 8.24 | |

| The main target of competency | Strengthening policy | 74 | 22.56 |

| Monitoring Evaluation and Reporting | 94 | 28.66 | |

| Private sector engagement | 44 | 13.41 | |

| Communication | 48 | 14.63 | |

| Regional engagement | 63 | 19.21 | |

| Others | 5 | 1.52 | |

| Target type of Competency | National Competency in Leadership | 59 | 18.67 |

| Management competency | 96 | 30.38 | |

| Socio-cultural competency | 85 | 26.90 | |

| Technical competency | 76 | 24.05 | |

| Competency Framework of the Education and Training Program | The internal competency framework | 78 | 45.88 |

| Implement the external competency framework | 81 | 47.65 | |

| Non-competency framework program | 11 | 6.47 | |

| Component of competency | Knowledge | 143 | 56.52 |

| Skill | 110 | 43.48 | |

| Curriculum of the Education and Training Program | Internal curriculum-based | 82 | 48.24 |

| Implementation of an external curriculum | 74 | 43.53 | |

| Non-curriculum-based | 14 | 8.24 |

| Intervention Levels | Component 1 (Strengthening LCDI Policy) | Component 2 (MER) | Component 3 (Private Sector Engagement) | Component 4 (Communication) | Component 5 (Regional Engagement) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agenda-setting | Sectoral policy translation, policy development, LCDI model | Mainstreaming LCDI into regional policy, sub-national LCDI model | |||

| Organizational | Capacity-building | Engagement in the private sector | Stakeholders’ communication | Engagement of the regional private sector, and regional stakeholders’ communication | |

| Operational | International reporting | Monitoring, evaluation, and national reporting (MER) | Sub-national reporting, regional MER |

| Intervention Levels | National Leadership Competencies | Management Competencies | Socio-Cultural Competencies | Technical Competencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agenda-setting (Components 1 and 5) | Develop policies and integrate the green economy using the LCDI model, considering social, economic, and environmental aspects | Manage green economy transitions according to sectoral and regional plans | Stakeholder engagement for participatory green economy development | Develop sectoral/sub-national green economy models using the LCDI framework |

| Organizational (Components 1, 3, 4, and 5) | Build capacity frameworks and networks for transitioning to the green economy | Manage capacity building and communication with stakeholders | Fostering trust and collaboration among diverse stakeholders | Lead learning processes for green economy implementation |

| Operational (Components 1, 2, and 5) | Develop systems for monitoring, evaluating, and reporting on the transition of the green economy | Manage monitoring and reporting systems | Engage stakeholders in evaluation and reporting | Conduct technical monitoring and reporting |

| Points of Entry (%) | Key Factors | Challenges | Opportunities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Development | Internal Institutional Arrangement | Capacity of internal development, Internal regulations and budget allocation, National strategy and action plan on green economy learning, Hub for building coherence and coordination | Existing learning system large number of education and training centers (719 units), Accredited institutions (154 units) |

| Leadership Capacity | Retaining awareness and capacity, Concern and awareness of high-level leaders in line ministries | Good leadership capacity at education and training center levels | |

| Staff Capacity | Lack of green economy expertise, Ratio of trainers–participants for big training/high demand events | Professional trainers for internal-regular learning programs (n = 5075 trainers) | |

| Accountability | Lack of accountability for organizing green economy learning, Competency framework on green economy, Learning needs and priorities | Moderate level of accountability for delivering internal-regular education and training programs, Existing initiatives on pro-green programs | |

| Accreditation | Readiness of targeted education and training centers, Mainstreaming green economy learning in accreditation processes | Concern of education and training centers on environmental issues, Supports for scaling up the green economy learning | |

| Reformation | Transformative capacity building approach for facing global environmental change political awareness | Grand design for bureaucracy reformation in the face of global dynamics and environmental issues | |

| External Partnership | Internal regulations on external partnership | Existing green economy programs in universities/research institutions/NSA International partnership/funding | |

| Variables | Estimate | SE | Wald | Sig. | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | WEB | |||||

| The main target of competency (Y) Threshold | ||||||

| Strengthening policy | −3.467 | 0.598 | 33.605 | 0.000 | −4.640 | −2.295 |

| Monitoring Evaluation and Reporting | −1.483 | 0.548 | 7.330 | 0.007 | −2.557 | −0.410 |

| Private sector engagement | −1.264 | 0.544 | 5.401 | 0.020 | −2.331 | −0.198 |

| Communication | −0.934 | 0.539 | 3.008 | 0.083 | −1.990 | 0.122 |

| Regional engagement | −0.244 | 0.531 | 0.212 | 0.645 | −1.284 | 0.796 |

| Others | −0.153 | 0.530 | 0.083 | 0.773 | −1.192 | 0.886 |

| Type of Institution | ||||||

| Government/Legislative | 1.855 | 0.723 | 6.585 | 0.010 | 0.438 | 3.272 |

| University | 1.276 | 0.545 | 5.490 | 0.019 | 0.209 | 2.343 |

| Private Sector | 3.173 | 1.365 | 5.404 | 0.020 | 0.498 | 5.849 |

| Community/NGO/Media | . | . | . | . | . | |

| Focus Area of Education and Training Program | ||||||

| Forestry and Peatland | −0.778 | 0.498 | 2.440 | 0.118 | −1.754 | 0.198 |

| Agriculture | −0.612 | 0.517 | 1.399 | 0.237 | −1.626 | 0.402 |

| Energy | −0.006 | 0.955 | 0.000 | 0.995 | −1.877 | 1.866 |

| Industry | −2.527 | 1.578 | 2.564 | 0.109 | −5.619 | 0.566 |

| Waste | −0.558 | 0.608 | 0.843 | 0.359 | −1.751 | 0.634 |

| Blue Carbon/Mangrove | −0.372 | 0.641 | 0.336 | 0.562 | −1.628 | 0.885 |

| Others | −0.106 | 0.626 | 0.029 | 0.866 | −1.333 | 1.122 |

| Combine | . | . | . | . | . | |

| Target audience | ||||||

| national leaders/legislators | −4.575 | 0.861 | 28.226 | 0.000 | −6.263 | −2.887 |

| civil servant apparatus | −3.827 | 0.734 | 27.174 | 0.000 | −5.266 | −2.388 |

| private sector | −1.986 | 0.745 | 7.098 | 0.008 | −3.447 | −0.525 |

| Community/NGO/Media | −2.475 | 0.668 | 13.738 | 0.000 | −3.783 | −1.166 |

| Academician/Researcher | −2.607 | 0.470 | 30.836 | 0.000 | −3.528 | −1.687 |

| Others | . | . | . | . | . | |

| Variables | Estimate | SE | Wald | Sig. | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | UB | |||||

| The main target of competency (Y) Threshold | ||||||

| Strengthening policy | −3.265 | 0.811 | 16.195 | 0.000 | −4.855 | −1.675 |

| Monitoring Evaluation and Reporting | −1.515 | 0.786 | 3.719 | 0.054 | −3.055 | 0.025 |

| Private sector engagement | −1.317 | 0.783 | 2.828 | 0.093 | −2.852 | 0.218 |

| Communication | −1.013 | 0.780 | 1.689 | 0.194 | −2.541 | 0.515 |

| Regional engagement | −0.366 | 0.774 | 0.224 | 0.636 | −1.882 | 1.151 |

| Others | −0.279 | 0.773 | 0.130 | 0.718 | −1.794 | 1.236 |

| Program relevant to LCDI | ||||||

| LCDI | 0.234 | 0.603 | 0.150 | 0.699 | −0.949 | 1.416 |

| LCDI and internal integrated | 0.316 | 0.558 | 0.320 | 0.571 | −0.777 | 1.409 |

| Non-LCDI/cooperation/Internal | 0 | . | . | . | . | . |

| The target type of Competency | ||||||

| National leadership | −1.044 | 0.602 | 3.012 | 0.083 | −2.223 | 0.135 |

| Management | −0.991 | 0.470 | 4.440 | 0.035 | −1.913 | −0.069 |

| Socio-cultural | −1.366 | 0.510 | 7.168 | 0.007 | −2.366 | −0.366 |

| Technical | −0.758 | 0.556 | 1.856 | 0.173 | −1.848 | 0.332 |

| Others | 0 | . | . | . | . | . |

| Competency Framework of Education and Training Program | ||||||

| Internal | 1.001 | 0.700 | 2.046 | 0.153 | −0.370 | 2.372 |

| Implement external | 1.200 | 0.696 | 2.969 | 0.085 | −0.165 | 2.564 |

| Non-competency framework | 0 | . | . | . | . | . |

| Component of competency | ||||||

| Knowledge | −1.909 | 0.429 | 19.796 | 0.000 | −2.750 | −1.068 |

| Skill | −1.827 | 0.503 | 13.203 | 0.000 | −2.813 | −0.842 |

| Knowledge and Skill | 0 | . | . | . | . | . |

| Curriculum of Education and Training Program | ||||||

| Internal curriculum based | −0.601 | 0.678 | 0.788 | 0.375 | −1.929 | 0.727 |

| Implement an external curriculum | −0.320 | 0.691 | 0.214 | 0.644 | −1.673 | 1.034 |

| Non-curriculum based | 0 | . | . | . | . | . |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karuniasa, M.; Firdaus, T. Points of Entry for Enhancing Policymakers’ Capacity to Develop Green Economy Agenda-Setting. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310727

Karuniasa M, Firdaus T. Points of Entry for Enhancing Policymakers’ Capacity to Develop Green Economy Agenda-Setting. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310727

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaruniasa, Mahawan, and Thoriqi Firdaus. 2025. "Points of Entry for Enhancing Policymakers’ Capacity to Develop Green Economy Agenda-Setting" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310727

APA StyleKaruniasa, M., & Firdaus, T. (2025). Points of Entry for Enhancing Policymakers’ Capacity to Develop Green Economy Agenda-Setting. Sustainability, 17(23), 10727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310727