1. Introduction

As early as 1987, Sustainable Development (SD) was an emerging and notable subject matter to which more awareness was of the essence. The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) in their special working meeting held in January 1987, among other issues, indicated that sustainable development was a pertinent aspect for consideration. To date, SD is still increasingly topical where sustainability in all spheres of life is pertinent. In the Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) region, there are a broad number of aspects regarding SD; however, it is clear that effective governance and policy implementation are strongly related to SD [

1]. Corruption is, however, noted as an inhibitor of Green Innovation (GI) and subsequently as an impediment of SD [

2]. African nations may therefore grapple with ascertaining the key elements to focus on as they seek to advance SD amidst the glaring challenges of limited resources, the natural resource curse (RC), under developed technological infrastructure, poor governance, among other considerations. Nonetheless, the attainment of the SDGs is seen as a collective concern for governments and enterprises with the need to develop mindfully designed strategies aimed at improving energy efficiency and promoting GI [

3]. The implications for SD in SSA can be further scrutinized by reviewing SD through the assessment of the interplay of key factors that provide for a representation of human development and the ecological linkage, thus the evaluation of digitalization, institutional quality, Green Innovation (GI), and Natural Resources Rents (NRRs).

According to the Global Footprint Network (GFN), SD in a nation is assessed through two major indicators namely the Human Development Index (HDI) and Ecological Footprint (EFP) [

4]. This cohesion is the basis for the Sustainable Development Index, which comprehensively evaluates SD and therefore the analysis here is a comprehensive review to guide African countries toward SD [

5]. HDI is an index of health, knowledge and the standard of living indicators of the ‘United Nations Development Programme’ (UNDP). UNDP [

6] further highlights that HDI calls for assessing the development of a country based on the capabilities of their people and not just economic growth. The UNDP’s HDI measures the extent to which a country’s residents effectively attain longevity, access to education and income and with an HDI higher than 0.7, a given country is deemed to have a high human index [

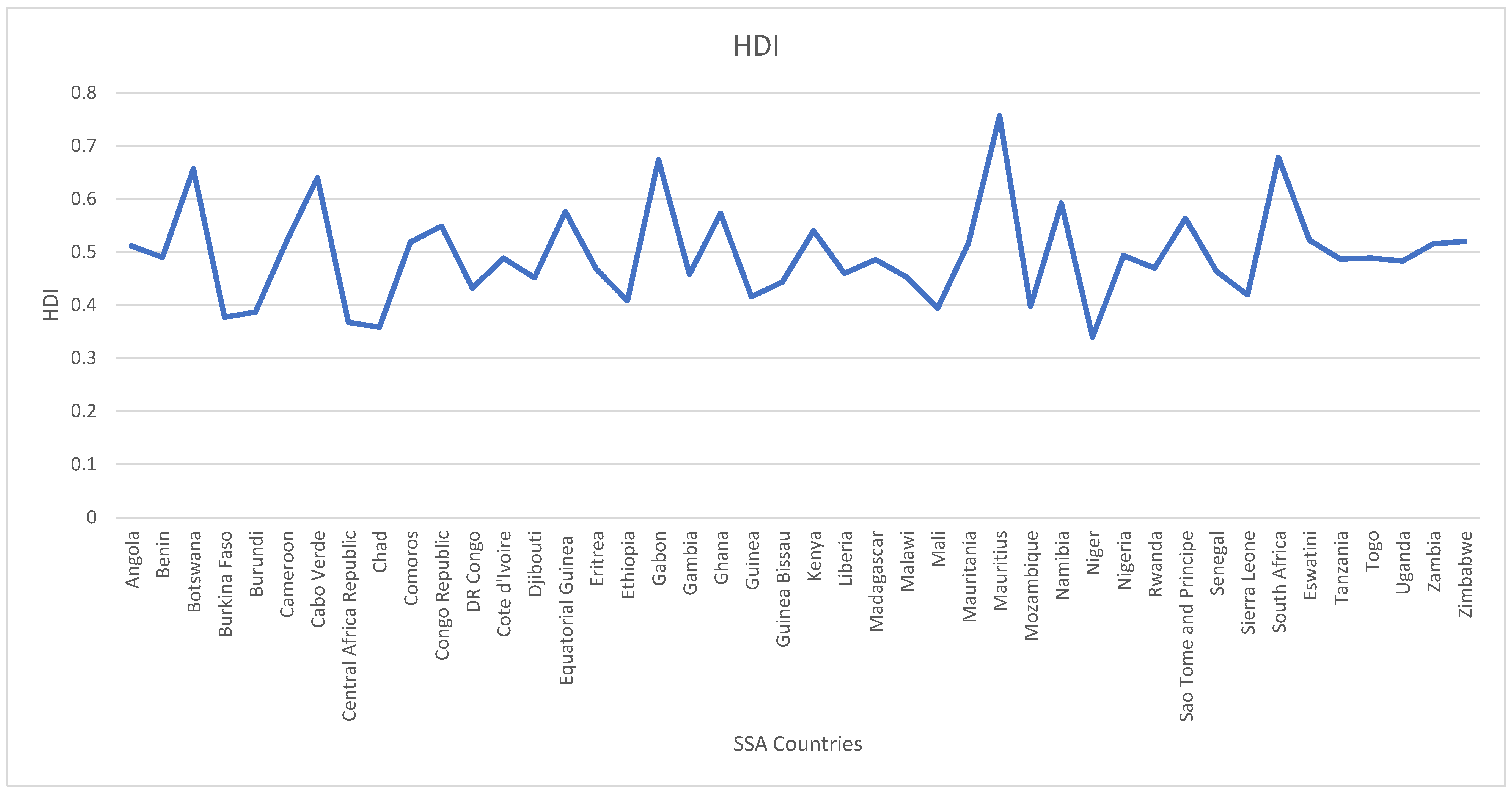

4]. The average HDI data of the UNDP [

6] for the time frame ranging from 2000 to 2021 is utilized to construct

Figure 1; and from the 44 SSA economies employed in this research, only Mauritius has an average HDI that is greater than 0.7, of 0.7564. This indicates the need for more efforts towards improved HDI levels in SSA. This evidence clearly shows that the SSA countries are still struggling in advancing human development.

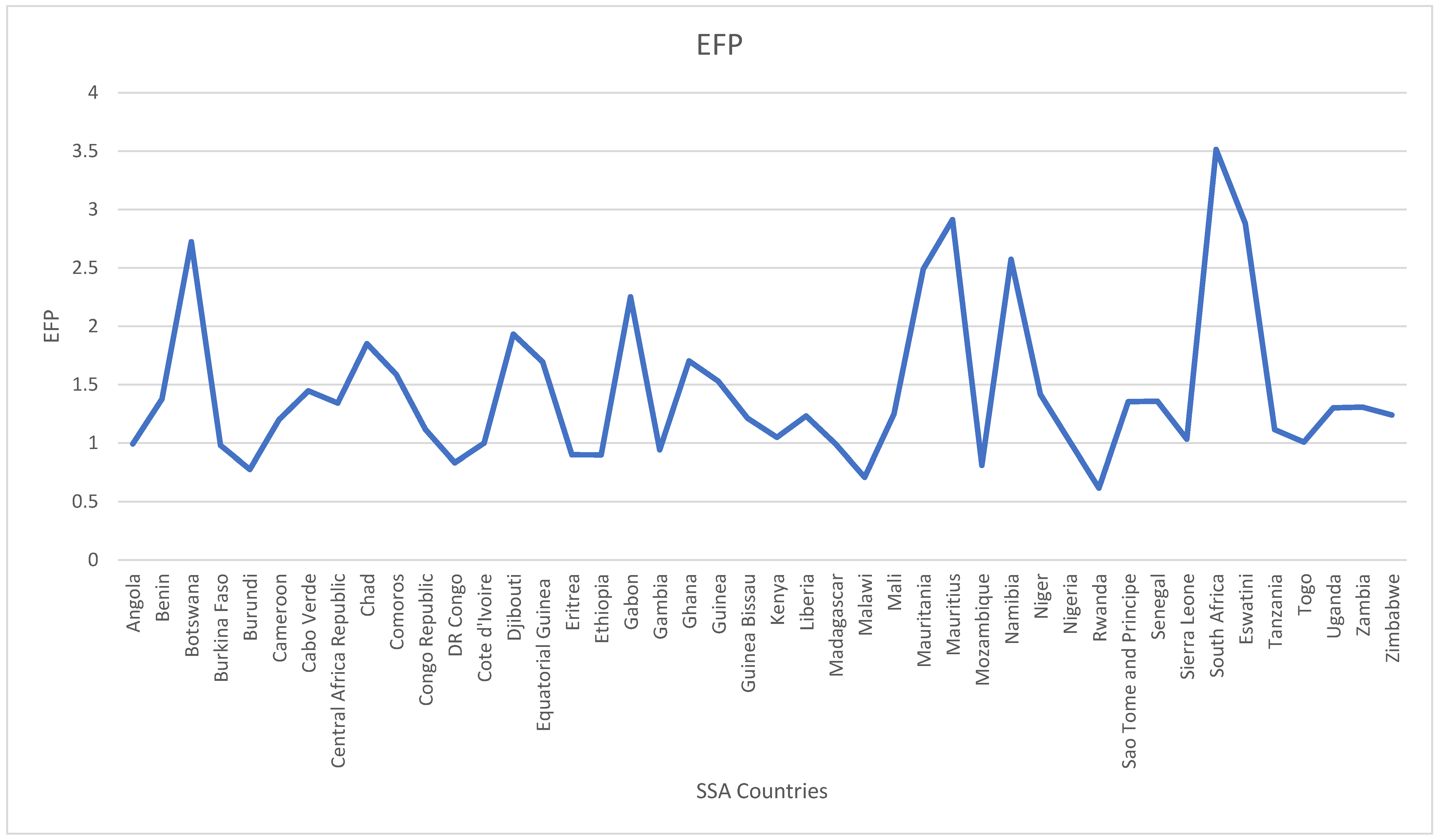

EFP on the other hand, represents the measure of the extent to which humans live within the means of nature and with less than 1.5 global hectares (gha) per person, the resource demand globally is replicable alongside the ease to maintain biodiversity [

4]. The EFP level in SSA provides a better indication that the people seek to preserve nature, as they utilize it for their day-to-day survival. In

Figure 2, only 13 SSA countries, out of the 44 assessed, have an average EFP of more than 1.5 gha per person. This shows that the greater percentage of SSA countries are not struggling with maintaining the ecological quality.

Generally, it is clear that the SSA countries are more compliant with EFP requirements compared to HDI. However, it is clear that collectively, both HDI and EFP require a significant improvement to effectively contribute to improve SD. The levels of SD in SSA can thus be deemed to be below average and the need to explore pertinent factors that can contribute to an improvement is highly prudent.

While similar studies focused on SD using either the HDI or the EFP, in our study, both dimensions are considered to create robust findings. Past studies on SD concentrated on examining the environmental aspect of sustainability [

7,

8]. This paper derives its novelty from merging environmental sustainability and human development dimensions thus adopting the Sustainability Development Index (SDI). Hickel [

5] indicates that the SDI is a ratio of HDI to EFP. This enables the comprehensive capture of evidence that is crucial in achieving sustainable futures.

There is a dearth of studies examining the interplay of green technological innovation, institutional quality and NRRs on sustainable development (through adopting the ratio of HDI and EFP) of SSA nations. This research checks the robustness of the findings presented from the SD index, by examining on how HDI and EFP are influenced with green technological innovation, NRRs and institutional quality. This allows for the shortfalls of the SD index to be overcome, where HDI and EFP may be both rising, causing the presentation of conflicting results. By adopting the ‘Methods of Moments Quantile Regression’ (MMQR), findings that are robust for policy implications toward sustaining the SSA region are presented. This helps in establishing the implied enablers and hindrances of SD with suitable recommendations to policy makers and key stakeholders. The data of SSA nations is utilized for the time spanning from 2000 to 2021. The key research questions that this paper addresses will explore the following objectives: the need to establish the relationship between digital technology and SD, to ascertain the influence of GI on SD and to understand national income and institutional quality related to SD.

4. Results and Discussion

The findings provided in

Table 3 (of the MMQR method) depict that GI significantly increases SD in the SSA nations. However, the relationship is significant in the 0.1 to 0.75 quantiles (

= −0.0037, −0.0032, −0.0024, −0.0016;

p-value < 0.05) and insignificant in the 0.9 quantile, showing that asymmetric effects exist. The PCSE and FGLS findings in

Table 4 supports the sig positive association of GI with SD (

= −0.0023, −0.0013;

p-value < 0.05). Model 2 findings of the MMQR method in

Table 3 supports by showing that green innovation sig reduces EFP (

= −0.0055 to −0.0146, in quantiles 0.5 to 0.9;

p-value < 0.05), while Model 3 findings show an insig relationship with HDI. Model 2 findings of the PCSE method in

Table 4 supports the sig negative association of GI and EFP (

= −0.0066;

p-value < 0.01), while the PCSE findings of Model 3 shows that GI is not sig related with HDI. The FGLS findings of Model 2 and 3 in

Table 4 indicates that GI is linked with decreases in EFP and increases in the HDI (

= −0.0058, 0.0004;

p-value < 0.01). The findings presented here supports the importance of GI in fostering the SD of the SSA region. Its importance is observed in lowering the EFP and raising the HDI. By reducing the EFP and increasing HDI, ES is attained together with advancements in the human development (quality health, education and standards of living). The positive link of green innovation and sustainable development presented in the findings of the study are supported by many empirical studies that have been undertaken in the past. For example, in the Nordic and Baltic region SD is attributed to GI [

12]. Xu et al. [

18] furthermore highlights that GI guarantees the attainment of SD. Other studies have also shown that GI (Green Finance) reduces EFP [

7]. Shang et al. [

13] postulate that the enactment of green financial policies provides for an intentional approach towards enabling SD. The notable contribution of GI in mediating the impact of HDI towards SD is further affirmed in emerging economies [

14]. These results are important for policy making as they show that the SSA countries with low levels of SD, that is, low HDI and high EFP, can improve SD of their nations with GI. The SSA countries could consider the enactment of policies that promote the adoption of GI alongside RE so as to keep on track towards SD.

On the relationship of digitalization with SD, Model 1 results of the MMQR in

Table 3 show insig relationship in the 0.1 quantile and sig positive relationship in the 0.25 to the 0.9 quantiles (

= 0.0008 to 0.0028 in the 0.25 to 0.9 quantiles;

p-value < 0.01). The PCSE and FGLS results supports the sig positive association of digitalization and SD (

= 0.0015, 0.0018;

p-value < 0.01). The MMQR findings of Model 2 and 3 in

Table 3 supports the results of Model 1 by showing that digitalization reduces EFP (

= −0.0049, −0.0044, −0.0037 in the 0.1 to 0.5 quantiles;

p-value < 0.01) and increases HDI (

= between 0.0015 and 0.001 in the 0.1 to 0.9 quantiles;

p-value < 0.01). The PCSE and FGLS results of Model 2 and 3 support the importance of digitalization in lessening EFP (

= −0.0034, −0.004, respectively;

p-value < 0.01) and supporting HDI (

= 0.0012, 0.0009, respectively;

p-value < 0.01). Usman et al. [

25] highlighted that technological innovations have a strong relationship with SDGs especially amidst good governance. Many empirical studies have also concurred on the importance of technological innovations (digitalization) with SD [

7,

28,

29,

30]. This calls for the SSA countries to finance the investment in digital technology, especially green technology, for attaining environmental sustainability and human development.

Model 1 findings of the MMQR method presented in

Table 3 shows that NRR exhibit a sig positive relationship with SD (

= 0.0011, 0.0004, 0.0021, 0.0027 and 0.0032 from lower- to upper-quantiles;

p-value < 0.05). The PCSE and FGLS results of Model 1 in

Table 4 depict that NRR has a positive association with SD (

= 0.0021 and 0.0017, respectively;

p-value < 0.01). The Model 2 MMQR results shows that NRR is negatively related with EFP (

= −0.011, −0.01, −0.0093, −0.0079, −0.0069, −0.0069 in the lower- to upper-quantiles;

p-value < 0.05) and positively related with HDI (

= 0.0009, 0.0007 in the 0.1 and 0.25 quantiles;

p-value < 0.01). In the 0.5 quantile NRR has a weak positive association with HDI (

= 0.0002;

p-value < 0.1) and weak negative association in the 0.9 quantile (

= −0.0003;

p-value < 0.1). The influence of NRR on HDI is thus asymmetric, it supports HDI when it is low more than when it is high, calling for the SSA countries with low human development to capitalize on the income generated from selling their NRs. NRR is thus established to be more of a blessing than a curse as illustrated by [

91]. As long as the environment has the ability to regenerate, the impact of NRR over time can be managed to continuously influence SD positively [

36]. The RB hypothesis is supported in this research, showing that economic development is supported with NRs in countries with high NRs endowments [

12,

33,

60]. However, [

38] applicable policies on NRRs sustainable usage and strategies to effectively manage NRs can be enacted [

37,

41].

The MMQR findings of Model 1 shows that IQ exhibit a weak positive relationship with SD (

= 0.0086, 0.0109, 0.0128, in the 0.5 to 0.9 quantiles;

p-value < 0.1), and insig effects in the lower quantiles, reflecting the existence of asymmetric effects. The PCSE findings of Model 1 reflect the existence of strong positive influence of IQ on SD (

= 0.0087;

p-value < 0.01), while the FGLS results show that the relationship is a strong negative one (

= −0.0122;

p-value < 0.01). The findings are conflicting, making it difficult for policy making; hence, the importance of the results of Model 2 and 3 in clarifying how IQ influence EFP and HDI, the two index used in the Hickel [

5] SD index. Model 2 results, according to the MMQR technique, depict that IQ worsens EFP (

= 0.06 to 0.088 in the 0.1 to 0.9 quantiles;

p-value < 0.01) and improves HDI (

= 0.0213, 0.0189, 0.0156, 0.0134 and 0.0117, in the 0.1 to 0.9 quantiles;

p-value < 0.01). The findings of the PCSE and FGLS methods in

Table 4 also supports by showing that IQ has a strong positive relationship with EFP (

= 0.0729 and 0.0776, respectively;

p-value < 0.01) and a sig positive relationship with HDI (

= 0.0161 and 0.0143, respectively;

p-value < 0.01). These findings highlights that IQ supports human development (education, healthy and living standards) in the SSA countries, but contributes to the degradation of the environment. The detrimental effects of IQ on the environment, presented in this research, is supported by the evidence presented in [

92], showing that government effectiveness, a proxy of IQ, is associated with increases in the EFP of the SSA region. Nonetheless, other studies have shown that IQ improves the ecological quality in the BRICS [

92]. The importance of IQ in supporting human development, as shown in this analysis, is also supported by the findings of [

93]. The SSA countries need to develop strong policies and adopt robust policy frameworks that support green projects for ES and also allow investments in education, health and economic development, to ensure advancement of human development. The current policy frameworks in SSA is more favorable to human development than ecological sustainability, calling for the need for policy reforms to ensure that environmental policies for ES are adopted in this region.

The MMQR results of Model 1 show that the influence of RE on SD is a sig positive one (

= 0.001 to 0.0026, in the 0.1 to 0.9 quantiles, respectively;

p-value < 0.01). Other methods, PCSE and FGLS, also support the importance of RE for SD in SSA (

= 0.0018 and 0.0019, respectively;

p-value < 0.01). Findings of Model 2, used for robust checks, show that RE lessens the impact on the environment through lowering the EFP (

= −0.0039 to 0.0098 in the 0.1 to 0.9 quantiles;

p-value < 0.01), while Model 3 results shows that RE does not sig advance human development. Furthermore, RE is observed to lessen EFP in the PCSE and FGLS results (

= −0.0066 and 0.0085, respectively;

p-value < 0.01) and improve HDI, according to the FGLS results (

= 0.0002;

p-value < 0.01), but the PCSE presents insig results. Fotio et al. [

42]; attested the notion of a positive relationship between RE and SD. Parab et al. [

45] further notes that the said relationship is also persistent not just in the SR but in the LR as well. This provides a scientifically supported basis that in the SSA countries, the aspect of RE is pertinent in the attainment of SD.

GDP per capita is observed to be linked with a sig negative connection with SD, according to the MMQR findings in

Table 3 (

= −0.0202 to −0.046 in the 0.25 to 0.9, respectively;

p-value < 0.01). In the 0.1 quantile, the association of GDP per capita and SD is a weak negative one (

= −0.0144;

p-value < 0.1). The PCSE and FGLS findings support the presence of a negative relationship between GDP per capita and SD (

= −0.03 and 0.0192, respectively;

p-value < 0.01). Real GDPC ought to have a positive impact on SD, following the evidence presented in past research [

50]. The negative influence of GDP per capita on SD is a major cause of concern for policy implications; hence, Models 2 and 3 are employed for robustness checks, ensuring sound policies are adopted. Model 2 results in

Table 3 depict that GDP per capita exacerbates EFP (

= 0.2958 to 0.4239, in the lower- to upper-quantiles;

p-value < 0.01) and improves human development (

= 0.0589 to 0.0625, in the lower- to upper-quantiles;

p-value < 0.01). The detrimental effects of GDP per capita on the environment is supported by the PCSE and FGLS results of Model 2 in

Table 4 (

= 0.3547 and 0.258, respectively;

p-value < 0.01), together with the importance of GDP per capita in supporting human development (

= 0.0609 and 0.0668, respectively;

p-value < 0.01). These findings give some important insights, showing that GDP per capita is negatively related with the Hickel [

5] SD index because it raises the EFP. Although it improves the human development, its influence of EFP is stronger as shown by the high coefficient values. This highlights that in SSA the linkage between GDP per capita and SD presents a challenge [

54]. Activities meant to improve human development harm the environment, posing a great dilemma to policy implications. The adoption of green technological approaches (the use of low-carbon energy, the use of clean technologies and shunning activities that harm the environment like deforestation) advances human development and ES at the same time, and are essential for SD in SSA.