Assessing Strategic GIS Perceptions in Waste Management Planning: A Readiness Model from South Africa’s Vhembe District

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framing: Capacity, Technology, and Reform Readiness

- Stage 1: Internal Operational Readiness characterized by human resource sufficiency, logistical coordination, financial stability, and regularized service delivery.

- Stage 2: Strategic Digital Integration, where digital tools such as GIS support forecasting, spatial planning, and infrastructure mapping.

- Stage 3: Participatory and External Engagement involving community feedback mechanisms, donor involvement, and intergovernmental support, which are only impactful once internal and digital layers are consolidated.

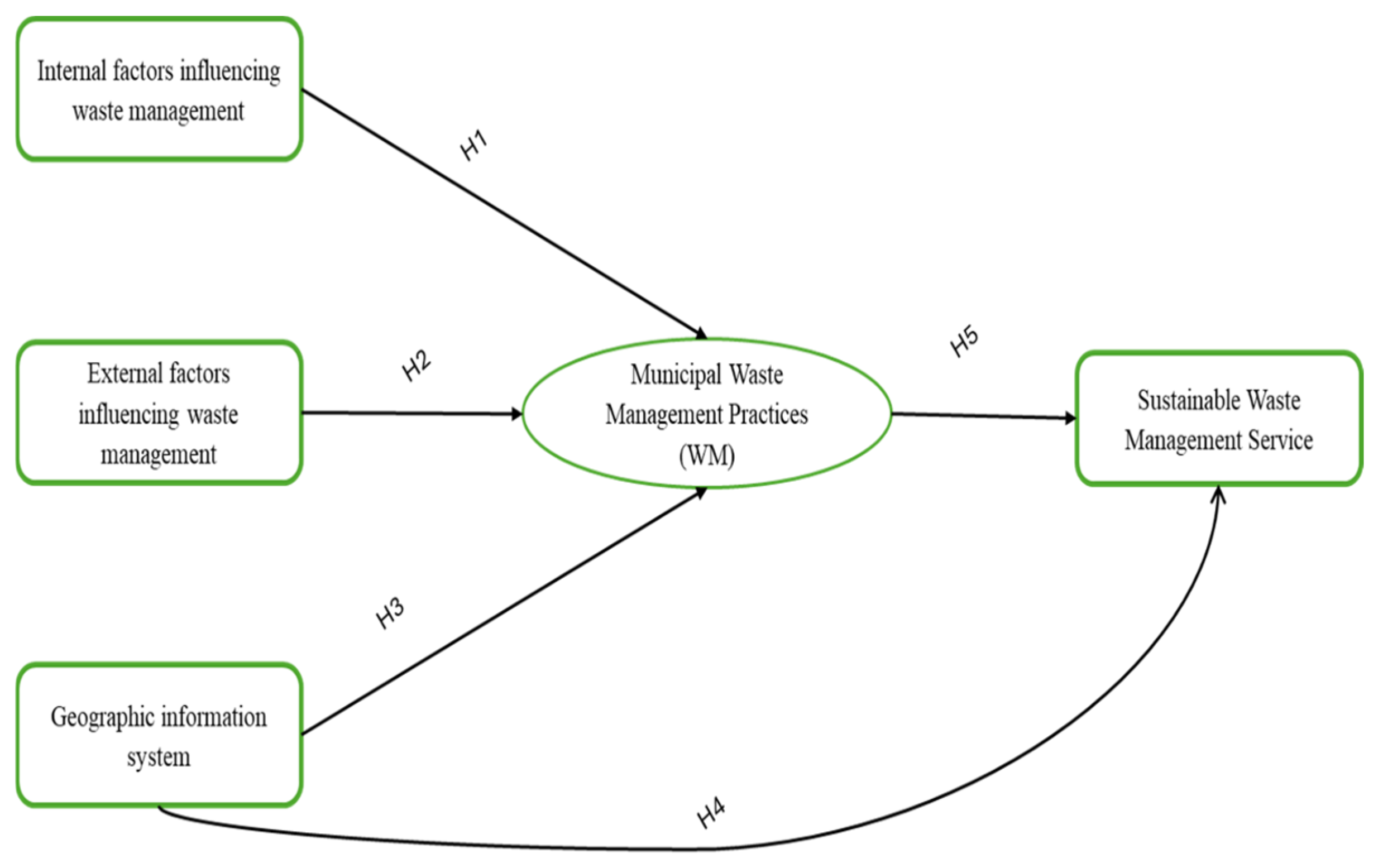

Conceptual Model Structure and Hypotheses Development

- Hypothesis 1—Internal Factors: Operational Waste Management Municipalities with strong internal capacity demonstrate better routine service delivery [26], consistent with Institutional Theory, which emphasizes that organizational routines, resources, and legitimacy are prerequisites for effective service provision [31,36].

- Hypothesis 2—External Factors: Operational Waste Management’s external support mechanisms, such as participation and donor aid, have a limited direct effect unless internal systems are stable [37,38], reflecting absorptive capacity theory, which argues that external inputs are ineffective when organizations cannot adapt and apply them [29].

- Hypothesis 3—GIS Integration: Operational Waste Management GIS alone does not improve operational delivery unless embedded within competent institutional systems [25], aligning with TAM, where perceived usefulness leads to adoption only when organizational readiness supports its integration [32,35].

- Hypothesis 5—External Factors: Strategic Waste Management’s external inputs enhance strategic performance only when internal and digital capacities are in place [39], consistent with institutional perspectives that highlight how stakeholder engagement and partnerships are most effective when organizational legitimacy and technological infrastructure are established [36].

3. Materials and Methods

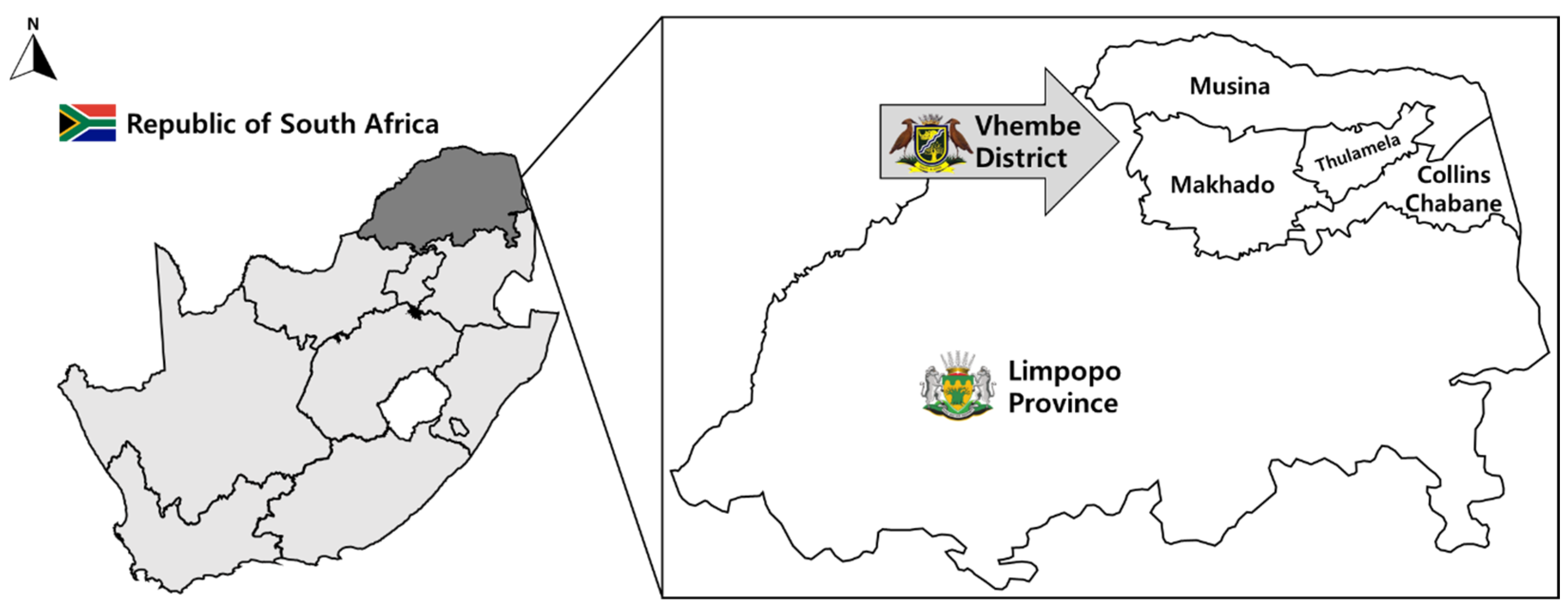

3.1. Research Design and Study Area

3.2. Sampling Strategy and Data Collection

3.3. Sociodemographic Profile of Respondents

3.4. Instrumentation and Construct Development

3.5. Data Analysis Procedures

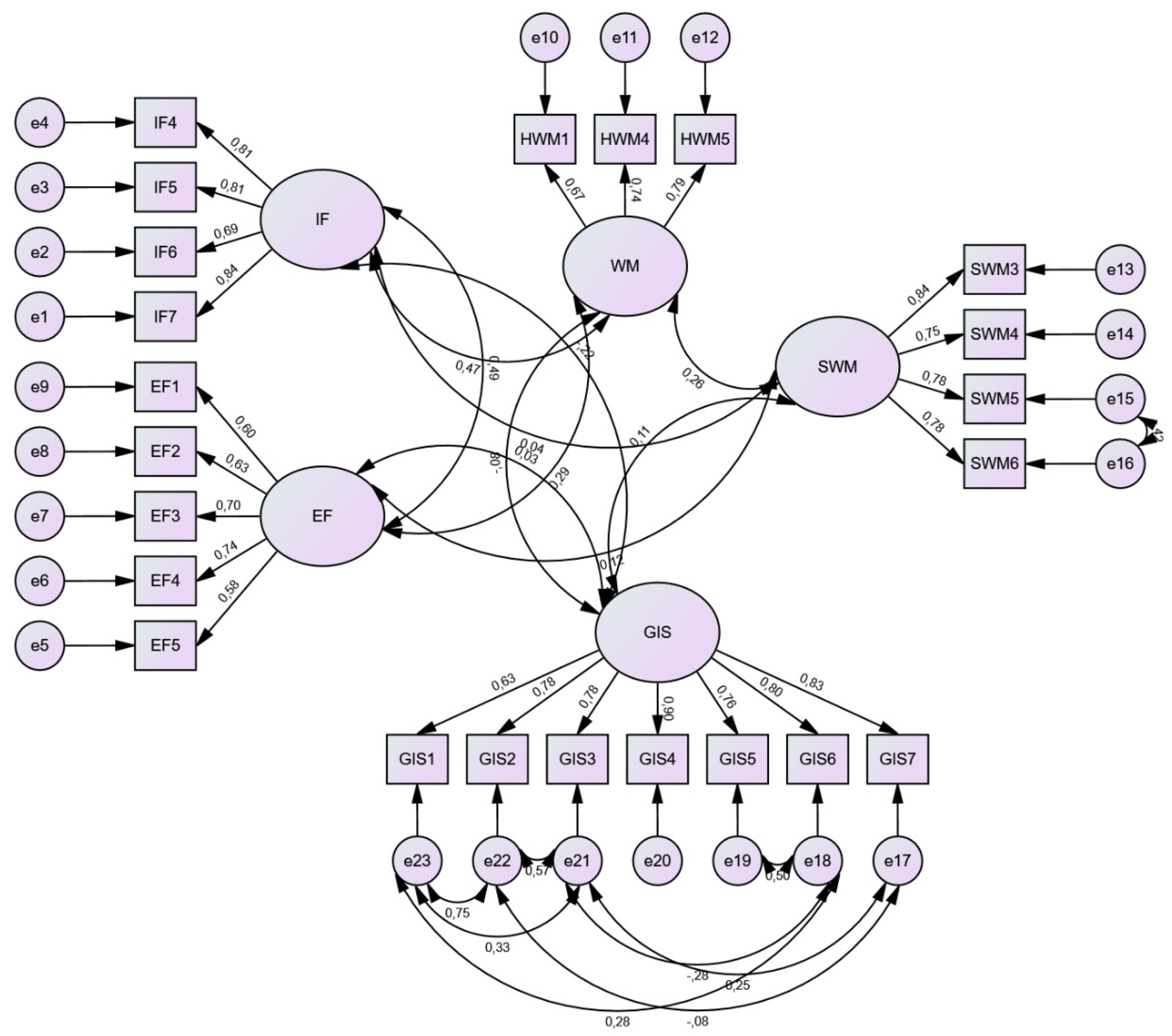

3.5.1. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.774 to 0.924.

- Composite Reliability (CR) values exceeded 0.77 for all constructs.

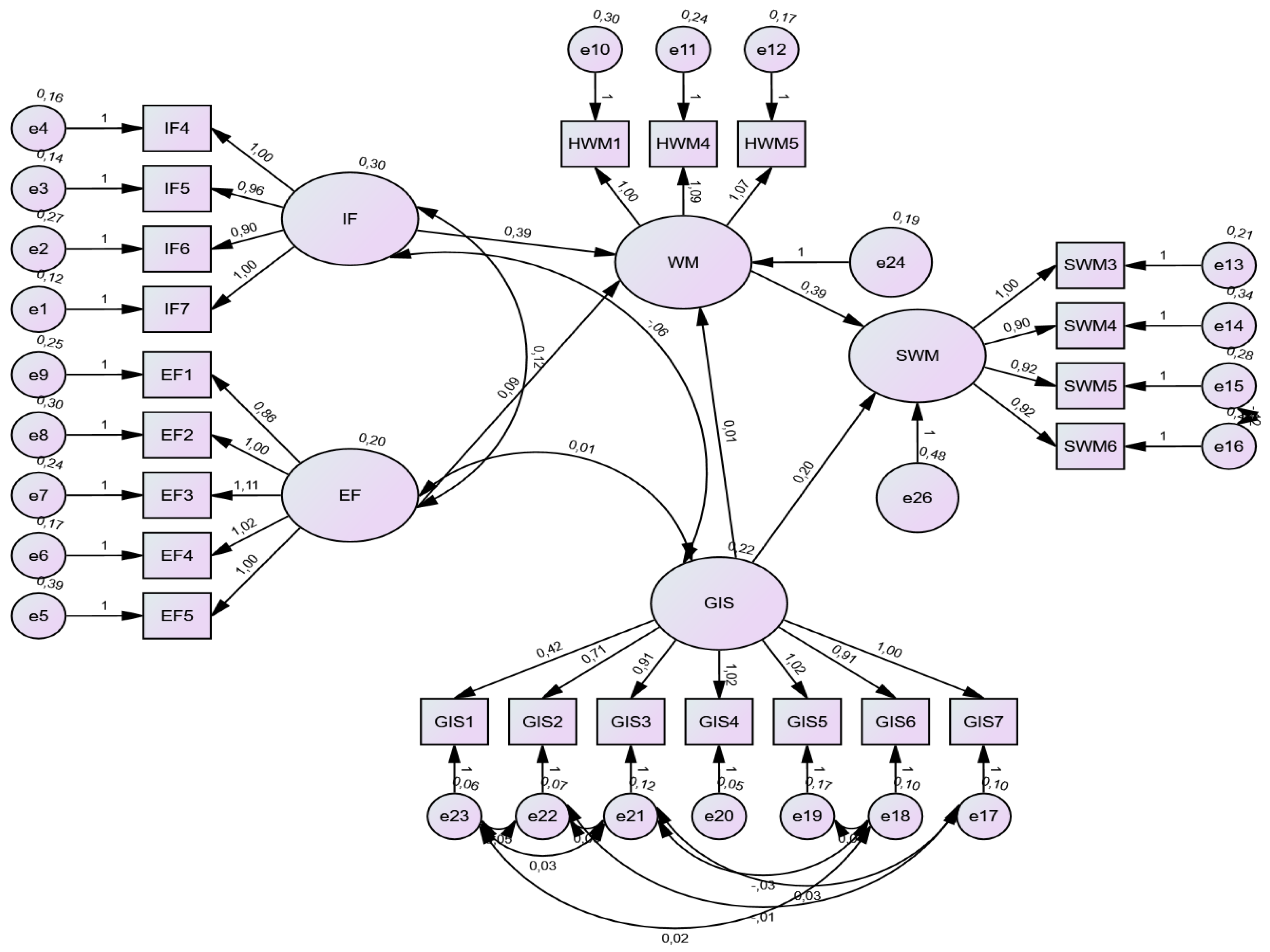

3.5.2. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

3.6. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Factors Influencing Waste Management Efficiency

4.2. Scale Reliability and Construct Validity

4.3. Fitness of the Model

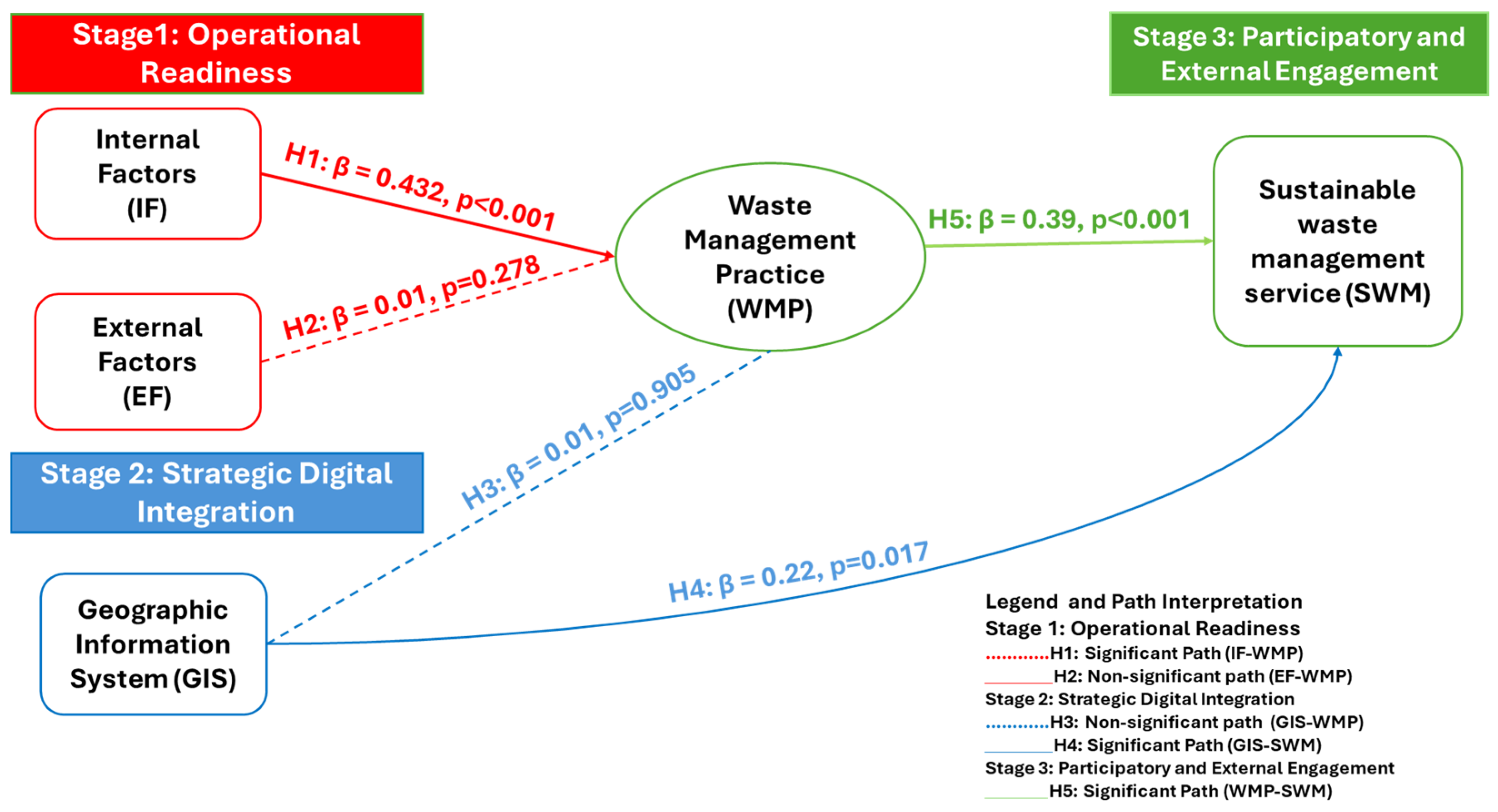

4.4. Structural Equation Model of Waste Management Variables (Hypothesis Testing)

5. Discussion

5.1. Internal Capacity: Foundational Determinant of Waste Governance

5.2. External Inputs as Conditional, Not Independent, Enablers

5.3. GIS as a Strategic Enabler, Not an Operational Instrument

5.4. Framing the Municipal Readiness Model for Digital Waste Governance (MRM-DWG)

- Stage 1—Operational Readiness: Foundational capacity is characterized by adequate staffing, regular collection, logistical coordination, and financial control. This stage showed the strongest predictive relationship with waste performance (β = 0.432, p < 0.001).

- Stage 2—Strategic Digital Integration: Once functionality stabilizes, GIS and related tools support planning, forecasting, and spatial optimization. GIS significantly influenced strategic outcomes (β = 0.130, p = 0.017), but not daily operations.

- Stage 3—Participatory and External Engagement: External collaboration becomes meaningful only after foundational and strategic systems are in place. The non-significant effect of external factors (β = 0.078, p = 0.278) underlines their dependence on prior internal capacity.

| Framework | Core Assumptions | Limitations | MRM-DWG Distinction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Reform Models | Interventions are most effective when layered together | Ignore sequencing, overburden low-capacity systems | Introduces staged logic based on capacity thresholds |

| ICT4D (Information and Communication for Development) | Technology drives performance | Often assumes linear adoption; ignores institutional maturity | Aligns digital integration with system maturity, not universal adoption |

| Participatory Governance | Community involvement increases accountability and efficiency | Presumes readiness for participation | Delays participatory scaling until institutional groundwork is secured |

| Smart City or Policy Transfer Models | Global solutions are replicable across urban settings | Downplays local variation and embedded constraints | Anchors reform logic in the municipal context, emphasizing readiness diagnostics |

5.5. Implications and Policy Recommendations

5.5.1. Implication 1: Operational Capacity Must Precede Reform Initiatives

- Policy Recommendation: National and provincial governments should invest in diagnostic audits that assess municipal readiness through indicators like equipment uptime, staff-to-service ratios, and collection regularity. Targeted funding for basic delivery systems rather than premature ICT upgrades should be prioritized where internal gaps persist.

5.5.2. Implication 2: Align Digital Tools with Strategic, Not Tactical, Objectives

- Policy Recommendation: GIS and other smart city technologies should be positioned as medium- to long-term investments. Their deployment should follow service stabilization and should be oriented toward spatial optimization tasks such as route design, landfill siting, and equitable infrastructure allocation. This aligns with findings from cities like Kigali and Nairobi, where GIS success was contingent on baseline system reliability [50], and contrasts with failure cases in Pakistan and Indonesia, where digital tools were introduced prematurely [16,48].

5.5.3. Implication 3: Stage Participatory Mechanisms According to Institutional Readiness

- Policy Recommendation: Donor agencies and development programs should calibrate their participatory expectations to match municipal capacity levels. Participatory forums, community engagement platforms, and co-production schemes should be introduced only after foundational delivery mechanisms and strategic planning systems are functional. Evidence from Nepal and Ghana supports this sequence, showing that external partnerships failed to yield measurable improvements where internal coherence was lacking [51,52]

5.6. Framework Application: MRM-DWG as a Governance Planning Tool

- Local Governments: to assess readiness levels and prioritize capacity-building before reform sequencing.

- Development Agencies: to target interventions (e.g., funding, technical assistance) in alignment with institutional maturity.

- Researchers and Evaluators: to apply the model in comparative contexts across sectors such as water, sanitation, and energy governance.

5.7. Implication: Future GIS Integration Should Be Spatially Grounded

5.8. Contextual Generalizability and Scaling of the MRM-DWG

5.9. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

- Stage 1: Internal stability forms the precondition for reform success.

- Stage 2: Strategic digital technologies follow operational consolidation.

- Stage 3: Participatory scaling becomes effective only when embedded within stable, functioning systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| CR | Construct (Composite) Reliability |

| DVs | Dependent Variables |

| EF | External Factors |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| IF | Internal Factors |

| IVs | Independent Variables |

| IWMPs | Integrated Waste Management Plans |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| MaxR(H) | Maximum Reliability |

| MM | Measurement Model |

| MRM-DWG | Municipal Readiness Model for Digital Waste Governance |

| MSWM | Municipal Solid Waste Management |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SWM | Strategic (Sustainable) Waste Management |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| WM | Waste Management |

| WMP | Waste Management Practice |

References

- Lal, R.; Bouma, J.; Brevik, E.; Dawson, L.; Field, D.J.; Glaser, B.; Hatano, R.; Hartemink, A.E.; Kosaki, T.; Lascelles, B.; et al. Soils and Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations: An International Union of Soil Sciences Perspective. Geoderma Reg. 2021, 25, e00398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Liu, E.; Hassan, D.; et al. Municipal Solid Waste Management Challenges in Developing Regions: A Comprehensive Review and Future Perspectives for Asia and Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abir, T.M.; Datta, M.; Saha, S.R. Assessing the Factors Influencing Effective Municipal Solid Waste Management System in Barishal Metropolitan Areas. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2023, 11, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukala, D.C.; Ifeanyi, A.; Owamah, H.I. A Review of Solid Waste Management Practice in Nigeria. NIPES—J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 2, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism. National Waste Management Strategy Implementation: Recycling and Extended Producer Responsibility; Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism: Pretoria, South Africa, 2005; pp. 1–29. Available online: https://sawic.environment.gov.za/documents/234.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Makhado Local Municipality. Integrated Waste Management Plan (IWMP); Makhado Local Municipality: Makhado, South Africa, 2017.

- National Environmental Management. National Environmental Management: Waste Act 59 of 2008; National Environmental Management: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009.

- Kubanza, N.S. Analysing the Challenges of Solid Waste Management in Low-Income Communities in South Africa: A Case Study of Alexandra, Johannesburg. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2025, 107, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, S.J.; Rodrigues, L.L.R. Behavioral Aspects of Solid Waste Management: A Systematic Review. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2020, 70, 1268–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, J.M.M.; Schenck, C.J.; Volschenk, L.; Blaauw, P.F.; Grobler, L. Household Waste Management Practices and Challenges in a Rural Remote Town in the Hantam Municipality in the Northern Cape, South Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahulela, A.C.; Hashemi, S.; Lourens, M.E. Household Waste Disposal Under Structural and Behavioral Constraints: A Multivariate Analysis from Vhembe District, South Africa. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukwevho, P.; Radzuma, P.; Roos, C. Exploring Barriers to the Effective Implementation of Integrated Waste Management Plans in Developing Economies: Lessons Learned from South African Municipalities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, A. Waste Management—A Case Study in Nepal. In Solid Waste Policies and Strategies: Issues, Challenges and Case Studies; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, J.; Mujumdar, S.; Srivastava, V.K. Municipal Solid Waste Management in India-Current Status, Management Practices, Models, Impacts, Limitations, and Challenges in Future. Adv. Environ. Res. 2023, 12, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonova, N.; Birchall, S.J. Sustainable Municipal Solid Waste Management: A Comparative Analysis of Enablers and Barriers to Advance Governance in the Arctic. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Beyond an Age of Waste Turning Rubbish into a Resource; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; ISBN 978-92-807-4129-2.

- Chandel, A.S.; Weto, A.E.; Bekele, D. Geospatial Technology for Selecting Suitable Sites for Solid Waste Disposal: A Case Study of Shone Town, Central Ethiopia. Urban Plan Transp. Res. 2024, 12, 2302531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Nguyen, N.; Phung, P.; Yến-Khanh, N. Residents’ Waste Management Practices in a Developing Country: A Social Practice Theory Analysis. Environ. Chall. 2023, 13, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Medina, A.J.; Salas López, R.; Barboza, E.; Tuesta-Trauco, K.M.; Zabaleta-Santiesteban, J.A.; Guzman, B.K.; Oliva-Cruz, M.; Tariq, A.; Rojas-Briceño, N.B. Participation GIS for the Monitoring of Areas Contaminated by Municipal Solid Waste: A Case Study in the City of Pedro Ruiz Gallo (Peru). Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Elomri, A.; Kerbache, L.; El Omri, A. El Smart City Solutions: Comparative Analysis of Waste Management Models in IoT-Enabled Environments Using Multiagent Simulation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, H.A.; Ayenew, W.A. Solid Waste Disposal Site Selection Analysis Using Geospatial Technology in Dessie City Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukalang, N.; Clarke, B.; Ross, K. Barriers to Effective Municipal Solid Waste Management in a Rapidly Urbanizing Area in Thailand. Int. J. Envrion. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strydom, W.F. Barriers to Household Waste Recycling: Empirical Evidence from South Africa. Recycling 2018, 3, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, T.; Defe, R.; Mavugara, R.; Mupepi, O.; Shabani, T. Application of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and Remote Sensing (RS) in Solid Waste Management in Southern Africa: A Review. SN Soc. Sci. 2024, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudzusi, T.N.; Munzhedzi, P.H.; Mahole, E. Governance Challenges in the Provision of Municipal Services: In the Vhembe District Municipality. Afr. Public Serv. Deliv. Perform. Rev. 2024, 12, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwane, N.; Botai, J.O.; Nozwane, S.H.; Jabe, A.; Botai, C.M.; Dlamini, L.; Nhamo, L.; Mpandeli, S.; Petja, B.; Isaac, M.; et al. Analysis of the Projected Climate Impacts on the Interlinkages of Water, Energy, and Food Nexus Resources in Narok County, Kenya, and Vhembe District Municipality, South Africa. Water 2025, 17, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalina, M.; Makwetu, N.; Tilley, E. “The Rich Will Always Be Able to Dispose of Their Waste”: A View from the Frontlines of Municipal Failure in Makhanda, South Africa. Envrion. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 17759–17782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive Capacity: A Review, Reconceptualization, and Extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyi, F.C.; Ogola, J.S.; Tshitangano, T.G. Challenges of Effective Management of Medical Waste in Low-Resource Settings: Perception of Healthcare Workers in Vhembe District Healthcare Facilities, South Africa. Trans. R. Soc. S. Afr. 2021, 76, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, L.; Scott, D.; Trois, C. Caught between the Global Economy and Local Bureaucracy: The Barriers to Good Waste Management Practice in South Africa. Waste Manag. Res. J. A Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2013, 31, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas and Interests; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, M.; Bussemaker, M.J. A Web-Based Geographic Interface System to Support Decision Making for Municipal Solid Waste Management in England. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukopová, J.; Ochrana, F.; Klimovský, D.; Mikušová Meričková, B. Factors Influencing the Efficiency and Effectiveness of Municipal Waste Management Expenditure. Lex Localis J. Local Self-Gov. 2016, 14, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katusiimeh, M.W.; Nabimanya, B.; Komwangi, D. The Neglected Governance Challenges of Solid Waste Management in Uganda: Insights from a Newly Created City of Mbarara. Afr. J. Gov. Public Leadersh. (AJoGPL) 2023, 1, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Adedara, M.L.; Taiwo, R.; Bork, H.-R. Municipal Solid Waste Collection and Coverage Rates in Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Waste 2023, 1, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finocchiaro Castro, M.; Guccio, C.; Romeo, D.; Vidoli, F. How Does Institutional Quality Affect the Efficiency of Local Government? An Assessment of Italian Municipalities. Econ Polit 2025, 42, 569–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-80518-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, M.; Pritchett, L.; Woolcock, M. Building State Capability: Evidence, Analysis, Action; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Okot-Okumu, J. Solid Waste Management in Uganda. In Future Directions of Municipal Solid Waste Management in Africa; Africa Institute of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015; pp. 107–135. [Google Scholar]

- Duru, R.U.; Ikpeama, E.E.; Ibekwe, J.A. Challenges and Prospects of Plastic Waste Management in Nigeria. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2019, 1, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, B.; Rai, R.K.; Nepal, M. Sustainable Financing for Municipal Solid Waste Management in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikou, V.; Sardianou, E. Bridging the Socioeconomic Gap in E-Waste: Evidence from Aggregate Data across 27 European Union Countries. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2023, 5, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araiza-Aguilar, J.A.; Rojas-Valencia, M.N.; Nájera-Aguilar, H.A.; Gutiérrez-Hernández, R.F.; García-Lara, C.M. Using Spatial Analysis to Design a Solid Waste Collection System. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabera, T.; Wilson, D.C.; Nishimwe, H. Benchmarking Performance of Solid Waste Management and Recycling Systems in East Africa: Comparing Kigali Rwanda with Other Major Cities. Waste Manag. Res. 2019, 37, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melles, G.; Gautam, S.; Shrestha, R. Circular Economy for Nepal’s Sustainable Development Ambitions. Challenges 2025, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyanyofio, J.G.T.; Domfeh, K.A.; Buabeng, T.; Maloreh-Nyamekye, T.; Appiah-Agyekum, N.N. Governance and Effectiveness of Public–Private Partnership in Ghana’s Rural-Water Sector. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2022, 35, 709–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos-Mora, S.L.; Guamán-Aucapiña, J.; Zúñiga-Ruiz, J. Suitable Site Selection for Transfer Stations in a Solid Waste Management System Using Analytical Hierarchy Process as a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis: A Case Study in Azuay-Ecuador. Envrion. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 1944–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables/Items | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Municipality | Makhado | 99 (24.8) |

| Musina | 100 (25.1) | |

| Collins Chabane | 100 (25.1) | |

| Thulamela Municipality | 100 (25.1) | |

| Residence Area | Rural Area | 143 (35.8) |

| Farm Area | 108 (27.1) | |

| City Centre | 61 (15.3) | |

| Township | 87 (21.8) | |

| Gender | Female | 245 (61.4) |

| Male | 154 (38.6) | |

| Age | 18–29 | 111 (27.8) |

| 30–39 | 113 (28.3) | |

| 40–49 | 93 (23.3) | |

| 50–59 | 59 (14.8) | |

| 60–69 | 16 (4) | |

| ≥70 | 7 (1.8) | |

| Number of Household Members | 1–2 | 20 (5) |

| 3–4 | 152 (38.1) | |

| 5–6 | 189 (47.4) | |

| 7–8 | 25 (6.3) | |

| ≥9 | 13 (3.3) | |

| Number of Years Residing in the Area | <1 Year | 2 (0.5) |

| 1–5 Years | 43 (10.8) | |

| 5–10 Years | 81 (20.3) | |

| 10–15 Years | 44 (11) | |

| 15–20 Years | 90 (22.6) | |

| ≥20 Years | 139 (34.8) | |

| Education | Never Schooled | 15 (3.8) |

| Primary | 81 (20.3) | |

| Secondary | 142 (35.6) | |

| Undergraduate | 74 (18.5) | |

| University Graduate | 86 (21.6) | |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | |

| Occupation | Unemployed | 132 (33.1) |

| Self-Employed | 148 (37.1) | |

| Government Employee | 68 (17) | |

| Farmworker | 37 (9.3) | |

| Other | 14 (3.5) | |

| Average Monthly Household Income | <R 10,000 | 172 (43.1) |

| R 10,000–R 30,000 | 174 (43.6) | |

| R 30,000–R 50,000 | 53 (13.3) | |

| Construct | Sample Items |

|---|---|

| Internal Factors (IF) | “Municipal collectors arrive when we are not home”; “We do not receive bin bags regularly.” |

| External Factors (EF) | “There are insufficient collection points”; “Lack of technical skills in our area.” |

| GIS Integration (GIS) | “GIS may help improve waste collection planning”; “GIS could lead to corruption.” |

| Operational Waste Practices (WM) | “Distance to disposal points leads to open dumping”; “Waste contaminates water sources.” |

| Strategic Effectiveness (SWM) | “We are unsure when waste will be collected”; “Waste is left to rot before collection.” |

| Construct | Variable | Description | Factor Loadings | Mean ± SD | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GIS in waste management | GIS1 | Using GIS technology to improve waste collection by our municipality would be highly welcome | 0.786 | 1.07 ± 0.309 | 0.924 |

| GIS2 | GIS use would alleviate the health hazards caused by waste disposal and collection in our municipality, as it would allow the managers to plan waste collection more appropriately | 0.868 | 1.10 ± 0.428 | ||

| GIS3 | Our environment would be more protected and safer if GIS were used to plan our waste collection and disposal | 0.839 | 1.13 ± 0.546 | ||

| GIS4 | The money for the GIS could be best used to develop our schools and hospitals | 0.874 | 1.14 ± 0.529 | ||

| GIS5 | Using GIS may lead to corruption, as the finances for it may get diverted | 0.823 | 1.17 ± 0.630 | ||

| GIS6 | GIS use may lead to job losses, and employment is very high in this area. | 0.838 | 1.14 ± 0.534 | ||

| GIS7 | Our municipal rates may increase if we use the GIS | 0.826 | 1.15 ± 0.562 | ||

| Internal factors in waste management efficiency | IF4 | We do not receive the municipal bin bags | 0.793 | 2.02 ± 0.680 | 0.867 |

| IF5 | We do not have the finances to buy bin bags, so we are forced to dump open waste at collection points | 0.850 | 1.96 ± 0.650 | ||

| IF6 | Municipal collectors come when we are not at home, and if we keep our bins out early, they get scattered by animals and will not be collected. | 0.795 | 2.04 ± 0.715 | ||

| IF7 | No recycling programme has been set up in the community by the municipality | 0.803 | 1.96 ± 0.654 | ||

| External factors in waste management efficiency | EF1 | Lack of technical waste management skills | 0.744 | 1.86 ± 0.630 | 0.785 |

| EF2 | Lack of waste collection equipment | 0.734 | 1.92 ± 0.702 | ||

| EF3 | Lack of adequate collection points | 0.699 | 1.96 ± 0.695 | ||

| EF4 | Insufficient waste collectors | 0.700 | 1.89 ± 0.614 | ||

| EF5 | Poor funding for waste collection | 0.704 | 2.04 ± 0.766 | ||

| Effectiveness of municipal waste management services | SWM3 | We are never sure when our waste will be collected | 0.882 | 2.12 ± 0.860 | 0.854 |

| SWM4 | Our waste is left out to rot and littered before it comes to be collected | 0.840 | 2.17 ± 0.878 | ||

| SWM5 | Only big wastes are collected, and our area is left messy as they do not pick up the littered waste | 0.798 | 2.16 ± 0.854 | ||

| SWM6 | Our municipality does not have proper waste collection equipment and enough personnel to do a good job | 0.777 | 2.11 ± 0.853 | ||

| Waste management practices | HWM1 | Waste is not properly collected in my area | 0.662 | 1.9 ± 0.737 | 0.774 |

| HWM4 | The distance to the waste disposal point is very far for my household, hence we are forced to dump it in the open | 0.717 | 1.99 ± 0.728 | ||

| HWM5 | Due to open dumping by people, our natural water sources are contaminated | 0.770 | 1.94 ± 0.67 |

| CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | EF | IF | WM | GIS | SWM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF | 0.787 | 0.427 | 0.240 | 0.796 | 0.654 | ||||

| IF | 0.869 | 0.625 | 0.240 | 0.878 | 0.490 | 0.790 | |||

| WM | 0.775 | 0.535 | 0.224 | 0.783 | 0.287 | 0.473 | 0.732 | ||

| GIS | 0.918 | 0.619 | 0.046 | 0.930 | 0.032 | −0.215 | −0.084 | 0.786 | |

| SWM | 0.868 | 0.623 | 0.069 | 0.873 | 0.116 | 0.038 | 0.263 | 0.106 | 0.789 |

| Hypotheses | Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Standardized Coefficient (β) | Standard Error | Critical Ratio | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | WM | IF | 0.432 | 0.068 | 5.653 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H2 | WM | EF | 0.078 | 0.080 | 1.084 | 0.278 | Not Supported |

| H3 | WM | GIS | 0.007 | 0.060 | 0.119 | 0.905 | Not Supported |

| H4 | SWM | GIS | 0.130 | 0.084 | 2.395 | 0.017 | Supported |

| H5 | SWM | WM | 0.267 | 0.090 | 4.385 | <0.001 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tahulela, A.C.; Hashemi, S.; Lourens, M.E. Assessing Strategic GIS Perceptions in Waste Management Planning: A Readiness Model from South Africa’s Vhembe District. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310626

Tahulela AC, Hashemi S, Lourens ME. Assessing Strategic GIS Perceptions in Waste Management Planning: A Readiness Model from South Africa’s Vhembe District. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310626

Chicago/Turabian StyleTahulela, Aifani Confidence, Shervin Hashemi, and Melanie Elizabeth Lourens. 2025. "Assessing Strategic GIS Perceptions in Waste Management Planning: A Readiness Model from South Africa’s Vhembe District" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310626

APA StyleTahulela, A. C., Hashemi, S., & Lourens, M. E. (2025). Assessing Strategic GIS Perceptions in Waste Management Planning: A Readiness Model from South Africa’s Vhembe District. Sustainability, 17(23), 10626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310626