2.1. Self-Determination Theory

Compared to alternative modeling approaches like neural networks, our choice of the SDT model is driven by research objectives. While neural networks excel at predicting complex nonlinear data patterns, they struggle to uncover the causal mechanisms underlying behaviors. In contrast, the SDT model provides a concise and interpretable theoretical framework that allows us to formulate specific hypotheses regarding the psychological needs and motivational processes behind safety behavior changes. This theory-driven research methodology is crucial for developing interventions, as it not only reveals phenomena but also clarifies their causes—for example, enhancing autonomy proves more effective than simply imposing external pressure. Therefore, the SDT model is better suited for explaining the intrinsic psychological mechanisms of safety behaviors, while neural networks are more appropriate for studies focused solely on achieving maximum accuracy in predicting safety events. SDT, proposed by Deci and Ryan in 1985, offers a systematic framework for understanding human motivation and personality development. The theory posits that individual behavior is influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, with intrinsic motivation closely related to the satisfaction of basic psychological needs such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness, while extrinsic motivation mainly depends on external reward and punishment mechanisms [

13,

14,

15,

16]. While traditional frameworks like the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) primarily focus on conscious behavioral beliefs and external social pressures, the SDT provides a more nuanced explanation through the lens of basic psychological needs. The unique value of SDT lies in its ability to clarify how external safety regulations and norms are internalized as personal values. The model posits that when the work environment supports employees’ intrinsic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, external safety values are more likely to transform into fully internalized intrinsic motivation. This internalization process is the key mechanism that distinguishes SDT from traditional models.

From the perspective of SDT, fulfilling the psychological needs of construction workers in three dimensions—autonomy [

17], competence [

18], and relatedness [

19]—can effectively enhance their safety behaviors. Meeting employees’ basic psychological needs not only significantly improves job satisfaction and intrinsic motivation but also serves as a key factor in explaining and predicting their behavioral patterns. Understanding these psychological drivers is crucial not only for immediate safety outcomes but also directly supports the sustainable development of the construction industry. Autonomy refers to workers’ sense of control and freedom over their actions. Involving employees in safety decision-making and granting them autonomy can significantly enhance their sense of responsibility and initiative in safety behaviors. This is essential for building a socially sustainable operational system, enabling employees to truly become active participants in their own well-being [

17]. Competence involves employees’ awareness and confidence in their abilities. Systematic safety training and skill enhancement can effectively reduce errors and rework. This not only helps conserve resources and minimize waste, thereby directly promoting economic sustainability, but also avoids material damage and corrective work, thus advancing environmental sustainability [

18]. Relatedness concerns employees’ sense of belonging and support within teams. A positive team atmosphere and management support can strengthen employees’ sense of belonging, thereby improving their safety behaviors [

19]. Furthermore, this study aligns closely with the principles of sustainable human resource management. This philosophy positions employees’ long-term development and well-being as the organization’s core assets [

20]. Sustainable HRM transcends traditional performance metrics by incorporating employees’ physical and mental health into its scope. In the construction safety sector, this approach advocates creating work environments that fulfill employees’ fundamental psychological needs—namely, autonomy, competence, and a sense of belonging. By investing in such psychologically supportive safety practices, companies can not only enhance immediate safety performance but also foster employees’ long-term mental health and sustainable employability, thereby achieving key social sustainability objectives.

2.2. Safety Cognition and Safety Behavior

Cognitive psychology indicates that human behavior is the product of cognition [

21]. According to Neisser, “cognition” refers to the process by which all sensory inputs are transformed, simplified, processed, stored, retrieved, and utilized [

22]. Combining the research on cognition and safety cognition, safety cognition is defined as the process of obtaining and processing information related to safety or danger and implementing decisions [

23].

From the perspective of construction sites, safety cognition is the core process by which construction workers acquire relevant safety information on the site, understand potential risks, choose safe responses, and execute safe operations. Existing research has clearly pointed out that the unsafe behaviors of construction workers often stem directly from mistakes in the safety cognition process [

24]. Whether it is the failure to accurately capture on-site danger information through the senses, the misunderstanding of the obtained safety information, or the deviation from safety logic in the response selection and execution stages, all can directly lead to unsafe operations [

25]. Further, in the context of high-altitude work, workers’ accurate cognition of high-altitude dangers can directly reduce unsafe behaviors related to falls [

26]. It is evident that safety cognition positively influences the safety behaviors of construction workers by directly affecting their risk perception and operation choices. Based on the above literature analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Safety cognition has a positive impact on the safety behaviors of construction workers.

2.3. Safety Psychology and Safety Behavior

Safety psychology examines the comprehensive psychological state formed by individuals in specific work environments, based on their perceptions of organizational safety culture, managerial support, and their own roles. This state comprises three core dimensions: safety attitudes, safety self-efficacy, and safety-specific emotions. It directly influences individuals’ risk assessment and safety decision-making, serving as the core cognitive mechanism that drives construction workers to transition from passive compliance to proactive safety practices [

27,

28].

At the same time, cognitive psychology holds that the core of human psychology and behavior is cognitive issues. Human behavior is determined by the interaction between the behavioral environment and the self. Personal behavior is not an isolated and simple response to external stimuli, nor is it the mechanical sum of many reflex arcs. Instead, it is made through the integration of the psychophysical field [

17]. Specifically, when workers develop a high level of identification with the project, they internalize safety rules as their own value standards. This cognitive-level internalization significantly enhances the self-awareness of safety behaviors [

27]. Additionally, research indicates that self-efficacy in safety psychology directly influences behavioral decisions; that is, the stronger a worker’s perception of their own safety capabilities, the more likely they are to proactively avoid risks [

29]. Moreover, cognitive-level safety motivation has been confirmed as the key path connecting psychological safety and safety behaviors—when workers perceive organizational support, a clear association of “safety behaviors are beneficial” forms in their cognition, enabling them to spontaneously comply with safety norms without external incentives [

28]. This direct mechanism of cognition on behavior indicates that improving safety psychology is not merely through emotional regulation but through reshaping workers’ cognitive evaluations of safety behaviors. Based on the above literature analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Safety psychology has a positive impact on the safety behaviors of construction workers.

2.4. Work Pressure and Safety Behavior

Work pressure is defined as the subjective perception of stress caused by high-intensity working conditions. It is manifested in three aspects: excessive workload, sense of time urgency and poor physical environment [

30,

31].

Furthermore, workplace stress frequently emerges as a focal point in occupational health discussions, particularly regarding its significant impact on safety compliance [

32]. Research indicates that high-intensity work demands coupled with resource shortages exhibit a negative correlation with safety compliance. This implies that when employees experience excessive work pressure, they may fail to effectively adhere to safety protocols, thereby increasing accident risks [

12]. Moreover, the cognitive depletion caused by stress leads employees to prioritize efficiency over safety, often resorting to shortcuts like ignoring safety regulations to expedite task completion [

33]. The substantial adverse effects of work pressure on safety behaviors also pose threats to economic and environmental sustainability. Errors and accidents resulting from high-pressure environments may lead to increased costs and material waste, negatively impacting project efficiency and environmental performance. More critically, persistent work pressure reinforces the erroneous belief that “safety compromises efficiency,” creating a self-perpetuating cycle where employees repeatedly engage in high-risk behaviors in subsequent operations. Based on the above literature analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Work pressure has a negative impact on the safety behavior of construction workers.

2.5. The Mediating Effect of Safety Psychology

Safety psychology not only refers to the psychological state when engaging in a certain job but also encompasses an individual’s awareness, knowledge, attitude, and behavior towards safety issues. These psychological activities may influence the probability of safety accidents occurring [

34].

Specifically, when workers identify potential dangers through perception and understanding, this cognitive result triggers their safety motivation, safety attitude, and risk perception at the psychological level. These psychological responses determine whether they are willing to invest additional effort in taking protective measures [

35]. In other words, if the psychological response is positive, cognition will be transformed into safety behavior; if the psychological response is negative, even if the cognition is in place, the behavior may be inhibited [

36]. This mechanism has been verified in multiple studies, such as the fact that safety attitude has been proven to significantly and positively predict safety behavior, while psychological capital and safety awareness indirectly promote the implementation of safety behavior by enhancing individuals’ emphasis on safety behavior [

37,

38]. Therefore, safety psychology is not an accessory to cognition but a crucial intermediary link determining whether cognition can be implemented. Based on the above literature analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Safety psychology plays a mediating role between the safety cognition and safety behavior of construction workers.

Work pressure is a psychological and physiological state of tension caused by unfavorable conditions in the work environment, including heavy workloads, tight time constraints, shift work arrangements, high temperatures, and adverse environments. Existing research has shown that there is a significant negative relationship between work pressure and safety behavior among construction workers [

39]. Work pressure not only directly leads to an increase in unsafe behaviors but may also weaken the level of safety behavior by affecting the psychological state of workers [

40]. For instance, high work pressure may result in the depletion of psychological resources, the accumulation of negative emotions, and a decline in risk perception ability, which further prompts workers to take quick and simple safety measures or ignore safety regulations [

41]. In driving behavior research, it is pointed out that drivers’ limited rational cognition and emotional states significantly influence their behavioral decisions, further supporting the mediating role of cognitive factors in behavior generation [

42]. Additionally, according to self-determination theory, positive psychological states such as work engagement can enhance an individual’s cognitive flexibility and behavioral adaptability, thereby promoting the implementation of safety behaviors [

43]. These studies collectively suggest that construction workers under high work pressure are more likely to exhibit a decline in safety behavior if their safety psychological resources are insufficient, while enhancing safety psychological resources may buffer the negative impact of stress on safety behavior. Based on the above literature analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Safety psychology plays a mediating role between work pressure and safety behavior of construction workers.

2.6. Moderating Effect

In the research on the safety behavior of construction workers, safety motivation reflects the tendency of workers to take safety actions due to their recognition of the importance of safety activities or their perception of safety as part of their personal values [

44]. Safety psychology, on the other hand, is a comprehensive psychological state formed by individuals in specific work contexts based on their cognition of the organizational safety atmosphere, management support, and their own roles, involving attitudes, beliefs, and emotions towards safety [

27,

28].

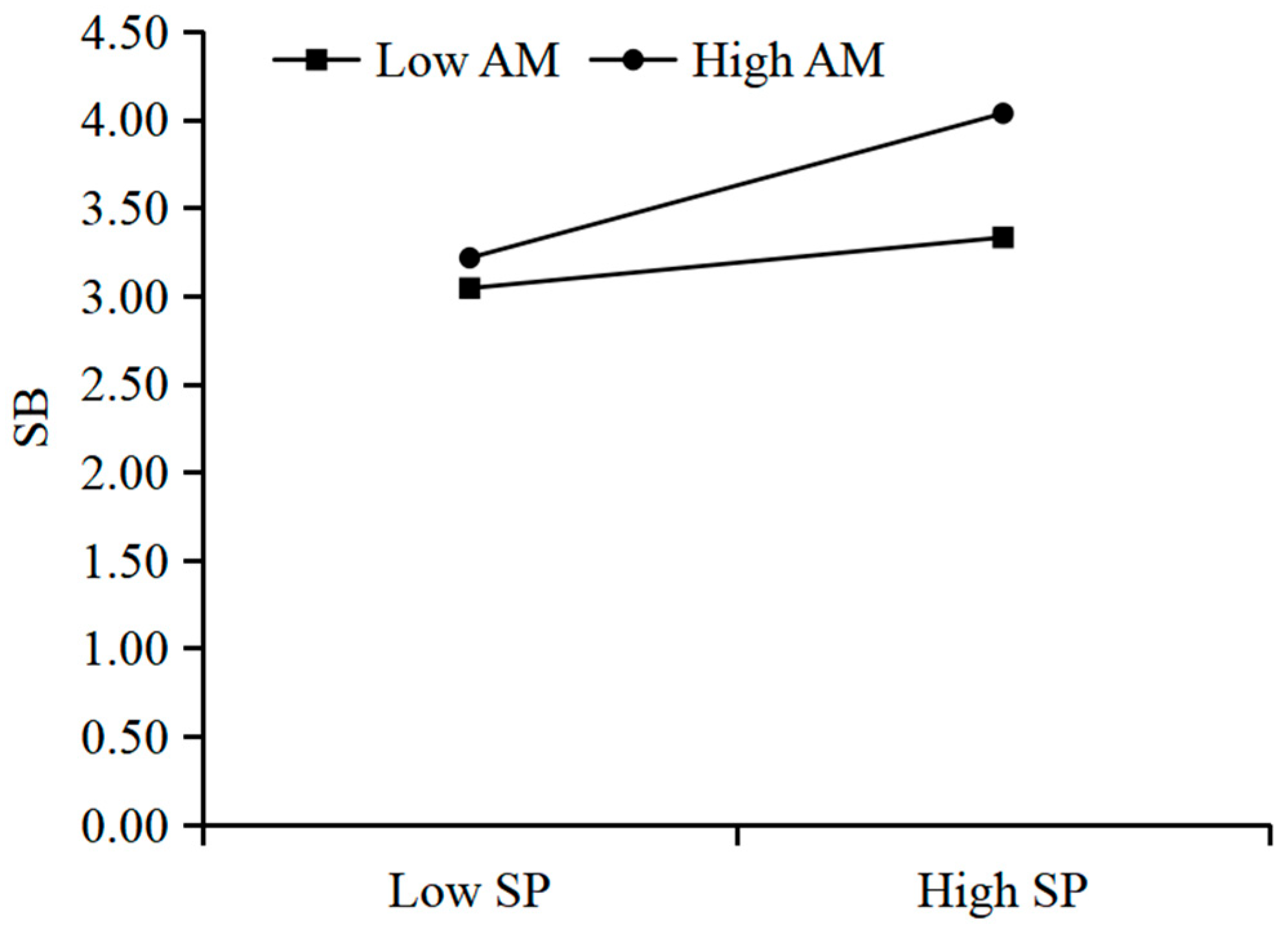

Autonomous motivation is characterized by workers’ genuine willingness to implement safety behaviors from the heart. When construction workers perceive that they can make autonomous decisions regarding safety matters, believe they have the ability to complete safety tasks, and feel supported by colleagues and supervisors, their safety behavior motivation tends to be more internalized. This internal motivation prompts workers to form more persistent and stable safety practices. This internalization process helps cultivate a safety culture, making compliance with safety measures a shared value among the workforce and further reducing the incidence of work-related injuries.

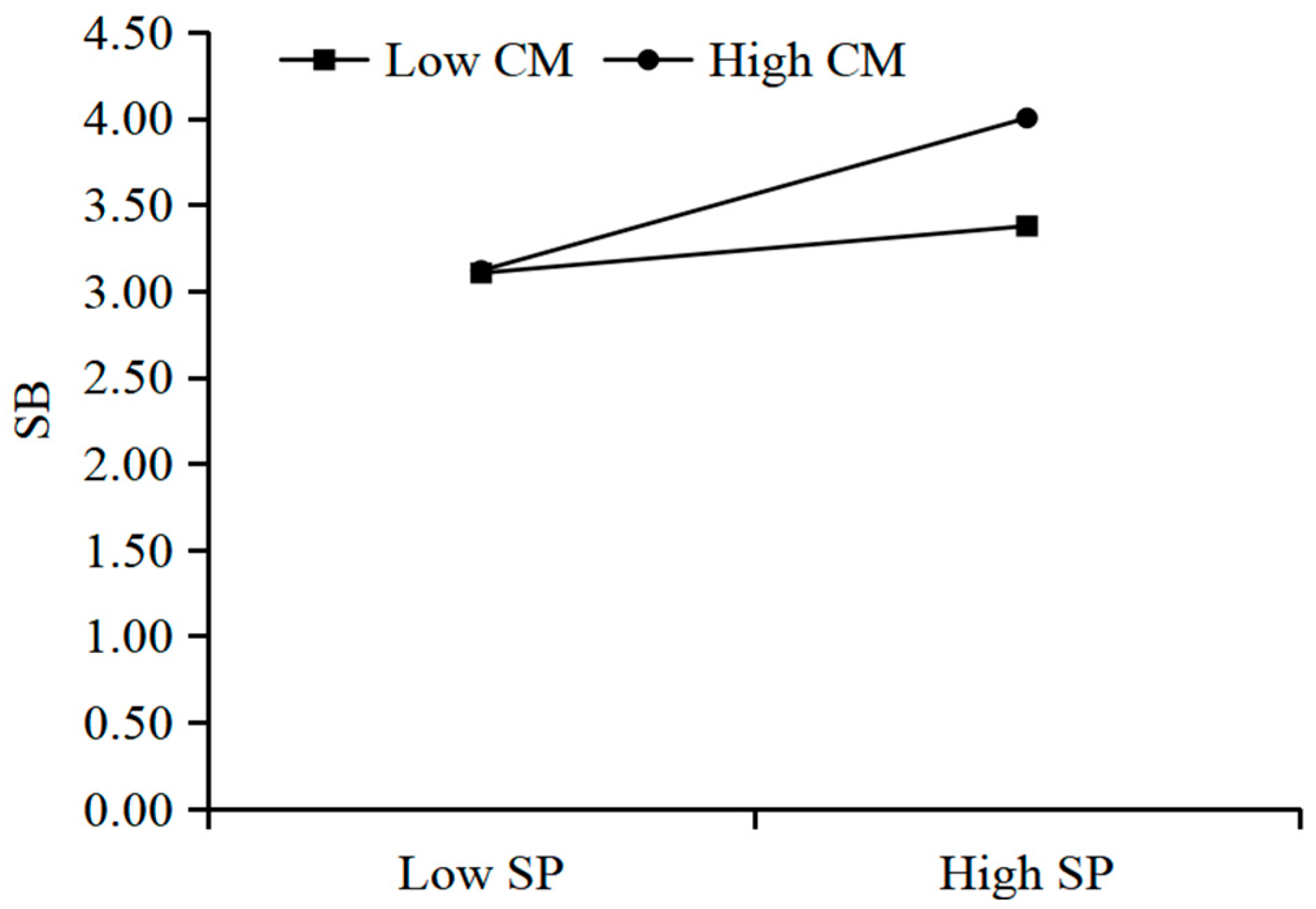

According to SDT, the regulatory types of controlled motivation can be classified into introjected regulation and external regulation [

27,

45], which refer to the behavioral tendencies of individuals driven by external pressure or rewards and punishments. It significantly affects an individual’s performance in a safe environment. Previous studies have shown that external safety motivation has a positive impact on safety behavior [

46]. Kvorning et al. pointed out that external forces play a crucial role in compelling individuals to perform specific behaviors [

47]. For instance, if employees mainly comply with safety regulations to avoid penalties or to meet regulatory requirements, their safety behavior often shows mechanical, passive adaptation and low persistence.

Although from a long-term internalization perspective, controlled motivation is less ideal than autonomous motivation, effective external control remains a necessary component of a sustainable safety management system. These control measures provide a basic level of protection and compliance, which is crucial for maintaining a safe working environment and preventing immediate injuries, and also meet the basic requirements of decent work. Based on the above literature analysis, we propose the following hypotheses:

H6: Autonomous motivation plays a moderating role between the safety psychology and safety behavior of construction workers.

H7: Controlled motivation plays a moderating role between the safety psychology and safety behavior of construction workers.

Social identity is defined as an individual’s awareness or knowledge of belonging to a certain group, as well as the emotional and value significance of this group membership to them. In the context of construction workers’ safety participation, project identity, as a specific form of social identity, is introduced into the research model to explain the workers’ extra-role behaviors in safety management. For instance, workers who have a strong sense of identity with the project they are involved in are more likely to actively participate in safety activities, help colleagues complete safety tasks, and propose safety improvement suggestions [

27].

However, the effect of cognition on behavior is not simple and direct, and psychological mediating mechanisms are particularly crucial in this process. Social identity theory indicates that an individual’s sense of belonging to a group can significantly influence the way their cognition is transformed into behavior [

48]. Specifically, when workers have a strong sense of identity with the project or team, they are more inclined to internalize the group’s safety norms and have a stronger motivation to convert safety cognition into actual behavior [

49,

50]. Additionally, research has found that role identity, as a specific form of social identity, can moderate the impact of different types of motivation on safety behavior [

44]. For example, in a high-identity state, workers are more likely to sustain safety behaviors driven by autonomous motivation, while in a low-identity state, even if controlled motivation is still at play, the persistence and quality of their behavior will decline. Based on the above literature analysis, we propose the following hypothesis.

H8: Social identity moderates the relationship between safety cognition and safety behavior of construction workers.

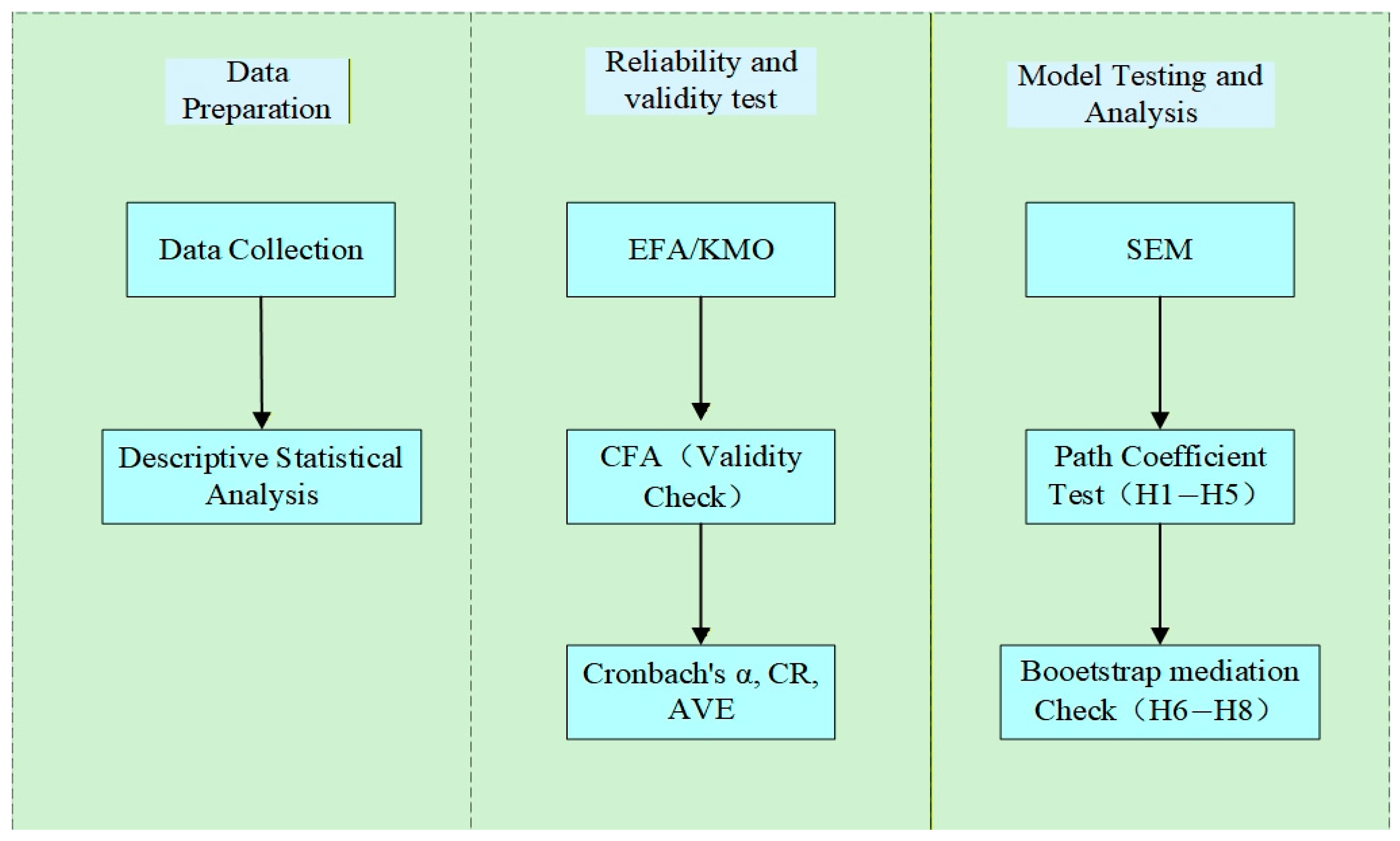

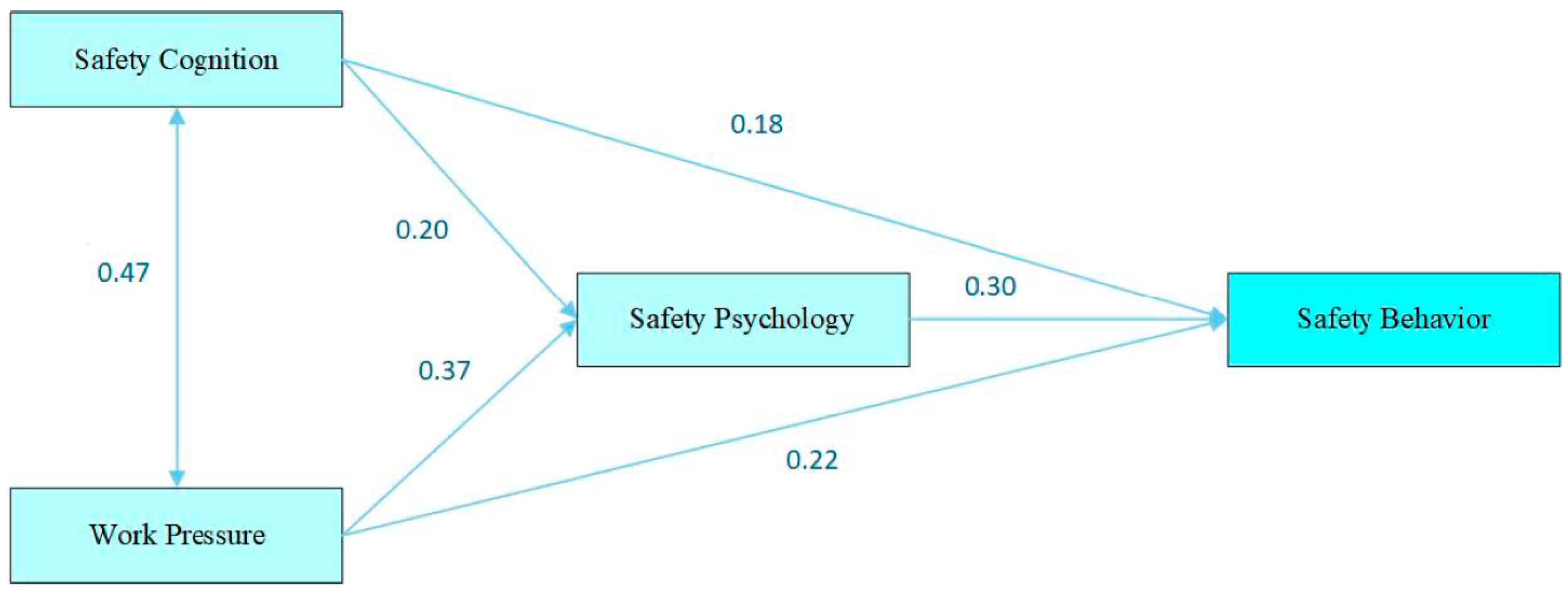

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of this study. The model elucidates the relationships among variables: safety cognition, safety psychology and job stress are hypothesized to directly influence safety behavior (H1–H3), while safety psychology mediates their indirect effects on safety behavior (H4, H5). The model further reveals that social identity moderates the relationship between safety cognition and safety behavior (H8), whereas autonomous and control motivation moderate the relationship between safety psychology and safety behavior (H6, H7).