1. Introduction

Spain’s rental market stands at the intersection of three powerful and converging forces: a historically underdeveloped social housing sector, sustained immigration flows, and an expanding tourism-driven short-term rental economy. With social housing covering less than 2% of households—one of the lowest rates in Europe—the private rental market functions as the primary safety net for low-income residents, newly arrived migrants, and young households [

1]. Since the mid-2010s, Spain has experienced continuous net immigration, which accelerated markedly after 2021, coinciding with a rapid rebound in international tourism. Both dynamics intensified competition for limited long-term rental units, particularly in coastal and urban regions where tourist-use dwellings (Viviendas de Uso Turístico, VUT) have proliferated, further constraining residential supply [

2].

Against this backdrop of structural supply rigidity and rising demographic pressure, Spain undertook a profound transformation of its welfare state architecture between 2020 and 2021. This shift was anchored in the nationwide implementation of the Minimum Living Income (Ingreso Mínimo Vital, IMV), the institutionalization of the Youth Rental Voucher, and pandemic-era moratoriums—all calibrated to the Public Indicator of Multiple Effects (IPREM) and embedded within the externally monitored conditionality of the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) [

1]. These reforms redefined “vulnerability” through juridical-administrative criteria tied to IPREM thresholds, effectively channeling public transfers into rental demand among precisely those populations most exposed to housing insecurity.

This study evaluates the extent to which these recent transformations—particularly housing policies and the administrative codification of “vulnerability”—have altered incentives and effective demand in rental markets during 2008–2025, with 2021 serving as a pivotal inflection point linked to RRF implementation [

1]. Prior policy frameworks had already steered interventions toward rental promotion and rehabilitation through state housing plans with income-conditioned access, contributing to market segmentation and constraints on rental stock availability [

3]. However, the post-2020 reforms operate under a distinct governance logic: one structured around externally verified milestones that prioritize rapid, measurable execution. This design compresses the horizon for supply-side responses and heightens the risk that demand-side transfers are partially capitalized into rental prices when supply elasticity is low [

1].

The necessity of examining the interaction between welfare reform, migration, and tourism lies precisely in this confluence: in a context where public support expands just as global mobility rebounds and housing supply remains inflexible, the potential for unintended consequences—such as rent inflation without improved access—is acute. Empirically, a pronounced co-movement between administrative inflows (e.g., benefit approvals, voucher allocations) and advertised rental prices emerges after 2021—consistent with a temporary regime shift coinciding with RRF disbursements. Given the higher temporal density and consistency of data availability, our empirical analysis focuses on the 2020–2024 period, enabling more robust testing of structural break hypotheses. While the study documents strong correlations and statistically significant breakpoints, it explicitly refrains from claiming full causal identification or complete implementation of the initially proposed dynamic model. Instead, it underscores the necessity of future extensions incorporating greater territorial granularity and quasi-experimental designs [

1].

What distinguishes this study from existing literature is its integration of housing policy evaluation into the framework of inclusive wealth—a comprehensive metric of a nation’s productive base encompassing natural, human, and produced capital. While prior research has examined housing affordability, welfare generosity, or rental market dynamics in isolation, few have assessed whether contemporary housing interventions sustain or erode inclusive wealth per capita, as required under the principle of weak sustainability [

4]. According to the United Nations Inclusive Wealth Report and Dasgupta (2021) [

4], intergenerational equity hinges on ensuring that inclusive wealth does not decline over time. In Spain, where housing constitutes approximately 60% of household assets and a dominant share of produced capital, policies that channel demand-side support into higher nominal prices—without expanding real access—risk inflating wealth indicators while undermining genuine welfare gains. This study thus provides a novel application of inclusive wealth as a normative benchmark for evaluating the long-term sustainability of welfare state reforms in housing.

The implications extend directly to multiple United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

SDG 11.1: Capitalization of subsidies into rents jeopardizes universal access to adequate, safe, and affordable housing by 2030.

SDG 10.1: In tight markets, such policies may disproportionately benefit property owners, exacerbating income and wealth inequality and counteracting efforts to sustain income growth for the bottom 40%.

SDG 1.4: If vulnerable households are priced out despite targeted assistance, their equal rights to economic resources and basic services are compromised.

Thus, while Spain’s welfare reforms align rhetorically with the 2030 Agenda, their implementation under conditions of supply rigidity reveals a critical tension between short-term policy delivery and long-term sustainable development. Recognizing Spain’s pronounced territorial heterogeneity—in housing supply responsiveness, tourism pressure, and subnational institutional capacity—we treat regional variation not as statistical noise, but as a constitutive dimension of policy impact. Following a geographical tradition that conceptualizes regions as historically grounded spaces of socio-spatial experimentation, our approach foregrounds how localized institutional and market contexts mediate the translation of national demand-side measures into rental inflation.

Given data and methodological constraints, this paper does not aim to identify the causal effect of housing policies on rental prices. Instead, it adopts an exploratory, hypothesis-generating approach to map the co-evolution of welfare reforms, migration inflows, tourism pressures, and housing market dynamics during a period of extraordinary macroeconomic turbulence. The goal is not to isolate policy impacts, but to flag potential interactions that warrant rigorous causal testing in future work.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology

This study is grounded in a partial equilibrium framework of the rental housing market, aiming to assess whether the implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) (RRF) [

1], together with the regulatory redefinition of vulnerability [

2,

8], coincides with a structural change in the relationship between administrative inflows proxied by total visa issuances—a publicly available, high-frequency indicator of overall international inflows. As detailed in

Section 3.3, this series conflates short-term (tourism) and long-term (residency) visas. While imperfect, it serves as a timely barometer of external demand pressure on urban housing markets, consistent with recent studies using similar proxies.

As shown in Figure 2 and

Table 3, these visa data include both short-term (e.g., tourism) and long-term (e.g., residency) categories, with short-term visas constituting the majority. We acknowledge that this aggregate measure conflates distinct demand channels: tourism-related pressure on housing stock availability, and welfare-enhanced effective demand from low-income households (including some newly arrived residents). The analysis therefore captures overall external administrative inflows, not solely new permanent household formation.

Within this framework, exogenous demand-side shocks—such as large-scale public transfers or rapid inflows of newly regularized migrants—are expected to exert upward pressure on rental prices only when supply is constrained, a condition well-documented for the Spanish urban housing market (e.g., limited new construction, high ownership rates, slow adjustment of social stock). Crucially, the RRF introduced in 2021 represents not a marginal policy tweak but a discrete institutional shift: it tied EU recovery funds to the expansion of housing vouchers and fast-tracked regularization pathways, effectively altering the rules governing access to both welfare and housing markets.

From a theoretical standpoint, such a regime change should manifest empirically as a discontinuity—or structural break—in the statistical relationship between migration inflows and rental prices around the time of implementation. This motivates our use of structural break tests as a reduced-form strategy to detect whether the observed data are consistent with the qualitative predictions of the partial equilibrium model. While a full theoretical model integrating demand, supply, and land-use dynamics via a system of ordinary differential equations underpins this analysis, the empirical focus here is limited to these testable implications using observed data: correlation analysis, structural break tests, and a minimal regression specification.

3.2. Empirical Strategy

The empirical analysis proceeds in three stages.

First, Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients are estimated between annual visa issuances and average monthly rental prices, separately for two sub-periods: 2010–2020 (pre-RRF) and 2021–2024 (post-RRF). This dual approach allows assessment of both linear (Pearson) and monotonic (Spearman) associations, enhancing robustness against non-normality or asymmetric distributions.

Second, structural break tests—specifically the Chow test and the Bai-Perron multiple-break procedure—are applied to detect statistically significant shifts in the slope and intercept of the visa–rent relationship around 2021.

Third, a minimal regression model is estimated in logarithmic first differences:

where

is a dummy variable equal to 1 from 2021 onward. This specification does not establish causality but evaluates whether observed changes align with the emergence of a new pricing regime following the RRF rollout.

3.3. Data Sources and Treatment

The data series used come from validated official and private sources. Visa issuance data were obtained from the Permanent Observatory on Immigration (OPI, Ministry of Inclusion), rental price listings from Idealista Data, tourist-use dwellings (VUT) from the National Statistics Institute (INE, experimental statistics), and total housing stock from INE and MITMA (Ministry of Transport, Mobility and Urban Agenda). Control variables include unemployment and employment rates (INE, EPA survey) and mortgage interest rates (Bank of Spain).

Data were harmonized according to their frequency: annual visa data, aligned with December rental closing periods; monthly rental prices for short-term trend analysis; and tourist accommodation data (VUT) available for February, August, and November to minimize seasonal bias. The analysis covers the period 2010–2024, with particular emphasis on the 2021–2024 subperiod.

The choice of 2021 as a focal year reflects the timing of major institutional reforms—including the nationwide scaling of the Ingreso Mínimo Vital (IMV), the launch of the Youth Rental Voucher, and the disbursement of EU Recovery and Resilience Facility funds—but it coincides with a period of exceptional macroeconomic turbulence. The post-2021 period saw the confluence of several powerful non-housing shocks: the global surge in inflation (particularly in energy and construction materials), the rebound of international tourism after pandemic restrictions, widespread adoption of remote work altering urban demand patterns, and supply chain bottlenecks affecting housing construction. Our analysis does not control for these factors explicitly, nor can it isolate the contribution of housing or migration policies from this broader context. As such, the observed shift in rental market dynamics should be understood as occurring alongside—not necessarily because of—the policy changes introduced around 2021.

It is critical to emphasize that all empirical results reported in this study reflect statistical associations and temporal co-movements, not causal effects. The absence of exogenous variation, instrumental variables, or quasi-experimental design precludes identification of causal impacts of public transfers, migration, or policy changes on rental prices. Our findings should therefore be interpreted as descriptive evidence of a structural shift in market dynamics around 2021—one that aligns with institutional timing and economic theory, but requires future validation through more rigorous causal designs.

The analysis faces three critical limitations that fundamentally constrain the strength of inference.

First, the post-2021 sample comprises only four annual observations (2021–2024), which severely limits statistical power and renders conventional inference—such as p-values or confidence intervals—unreliable. Estimates are highly sensitive to single-year fluctuations, and the risk of spurious association is substantial.

Second, rental prices reflect offer (asking) values from Idealista rather than contracted or administratively recorded rents. Although widely used for market monitoring, asking prices may diverge from actual transaction values due to negotiation discounts or strategic pricing, particularly in volatile markets. We acknowledge that our earlier assertion—that this bias is “less likely to affect trend analysis”—is unsupported; on the contrary, it could distort both levels and slopes during periods of rapid adjustment.

Third, as noted earlier, 2021 coincided with multiple non-housing shocks—including the post-pandemic reopening, global inflation, tourism rebound, and shifts in remote work—any of which could independently influence rental dynamics.

These limitations are partially mitigated through descriptive robustness checks (e.g., jackknife leave-one-out analysis and comparison with available administrative rent indices), but we emphasize that all post-2021 findings should be interpreted as preliminary and exploratory, not as statistically validated evidence.

A further limitation is the inability to disentangle demand-driven from supply-driven rent increases. The post-2021 period coincided not only with expanded social transfers but also with significant supply-side shocks, including a >30% surge in construction material costs (INE, 2022) and acute labor shortages in the building sector (Ministry of Transport, 2023). These factors would mechanically constrain new supply and elevate replacement costs, thereby pushing rents upward even in the absence of demand-side policy changes. While our descriptive design cannot isolate these effects, we discuss their potential contribution in

Section 4 and the Conclusion.

3.4. Disaggregated Analysis by Autonomous Communities (CCAA) and Provinces

A spatially disaggregated analysis is conducted at the level of Autonomous Communities (CCAA) and provinces using geospatial data from INE’s official boundary files (.gpkg format). Monthly rental price data (2018–2025) are aggregated into annual averages for trend analysis. The output includes:

3.4.1. Full CCAA Table (Pre- vs. Post-2021)

Compare the periods 2018–2020 (pre) and 2021–2025 (post) with the following metrics for each CCAA:

Mean rental price (€/m2) in each period.

Slope (€/m2/month) from linear trend regression in each period.

Level shift (difference in intercepts between pre- and post-2021 trends).

CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) of rental prices in the post-2021 period.

Purpose: Identify regional shifts in rental dynamics before and after the implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) (RRF/NextGenerationEU).

3.4.2. CCAA Rankings

Ranking by change in slope (Δslope = post-slope − pre-slope): highlights regions where rental price acceleration increased the most after 2021.

Ranking by level shift: identifies regions with the largest immediate jumps in rental prices after 2021, controlling for trend.

3.4.3. Provincial Table

For each province (identified by INE code in PROVINCIA field):

Mean rental price (€/m2) in pre-2021 (2018–2020) and post-2021 (2021–2025).

Trend slope (€/m2/month) in each period.

Purpose: Enable granular comparison across smaller administrative units.

3.4.4. Correlations by CCAA

For each Autonomous Community, compute:

Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients (with p-values) between:

Annual population change (ΔP);

Annual change in rental prices (Δprice).

Conduct analysis separately for two periods:

Pre-2021: ≤2020;

Post-2021: ≥2021.

Purpose: Assess whether the strength of the demographic-rent link changed after RRF implementation.

3.4.5. Panel_with_deltas: Annual Differences Dataset

Create a panel dataset with annual first differences to avoid spurious correlations from level trends. Use only changes, not levels.

Definitions:

∆pricet = pricet − pricet−1 ° (annual change in €/m2).

∆Pt = Pt − Pt−1 ° (annual population change).

Analysis windows per CCAA:

Pre-2021 period: 2019–2020.

Post-2021 period: 2022–2024.

Required statistics for each CCAA and period:

Pearson correlation coefficient (r) between:

∆Pt/1000 ° (population change per 1000 inhabitants).

∆pricet.

OLS slope coefficient (β) from regression:

∆pricet = α + β·(ΔPt/1000) + ε.

Report β with R2, p-value, and n (number of observations).

Interpretation of β:

Example: If β = 0.05, this means a +0.05 €/m2 increase in rental prices for every +1000 additional inhabitants in a given year and region.

To scale: Multiply β by 10 → gives effect per +10,000 inhabitants.

Missing data for certain CCAAs (e.g., Asturias, Cataluña) in specific years are handled via linear interpolation or forward-fill, depending on series continuity. Full data availability per region is reported in

Appendix A Table A1.

3.5. The Role of Regional Geography as a Spatial Test Bed

This study adopts a spatially differentiated approach to analyzing the rental market, grounded in the geographical concept of region as a test bed for socio-spatial hypotheses. As Higueras Arnal (2002) argues, regions are not merely administrative units but historically and structurally constituted spaces where economic, social, and institutional processes interact in distinct ways. In this context, Autonomous Communities (CCAA) in Spain serve as natural experimental settings—each with varying degrees of housing supply elasticity, exposure to tourism, and implementation capacity for social housing policies.

By comparing the evolution of rental prices across CCAAs before and after 2021, we exploit this spatial heterogeneity to assess how local structural conditions moderate the impact of demand-side shocks (e.g., migration inflows, housing vouchers). The regional variation in correlation strength is not noise to be controlled away, but central to our analytical framework: it reveals where and under what conditions policy-induced demand is capitalized into prices.

This approach aligns with a growing body of literature that treats regions as “quasi-natural experiments”, particularly in contexts of asymmetric policy rollout and uneven urban development. While our econometric tools are intentionally transparent, they are applied within a theoretically informed spatial framework that enhances external validity and policy relevance.

4. Findings

The analysis shows a marked increase in the correlation between total visa issuances and rental prices after 2021. However, as Figure 2 illustrates, the vast majority of these visas are short-term (tourism-related), while only a minority correspond to long-term residency. Therefore, the observed co-movement likely reflects the combined effect of multiple external pressures: (i) tourism-driven competition for housing stock via VUT expansion [

16,

17], and (ii) enhanced effective demand from welfare recipients (including some newly arrived residents eligible for IMV or youth vouchers) [

7,

8]. We do not claim that visa inflows represent new permanent renters; rather, total visas act as a composite signal of heightened non-residential and subsidized demand pressures on an inelastic rental market.

4.1. Dynamics 2008–2025: Prices, Visas and TOURIST-USE DWELLINGS (VUT)

From 2008 to 2020, rental prices in Spain exhibited irregular growth, showing no stable association with international migration flows as proxied by consular visa issuances. However, from 2021 onward, the trend slope accelerates markedly, revealing a clear co-movement with rising visa numbers. This synchronized growth suggests that expanded social transfers—such as the Minimum Vital Income (MINIMUM LIVING INCOME (IMV)) and youth rental vouchers—enhanced effective demand among low-income and migrant households, particularly in cities with constrained housing supply.

As shown in

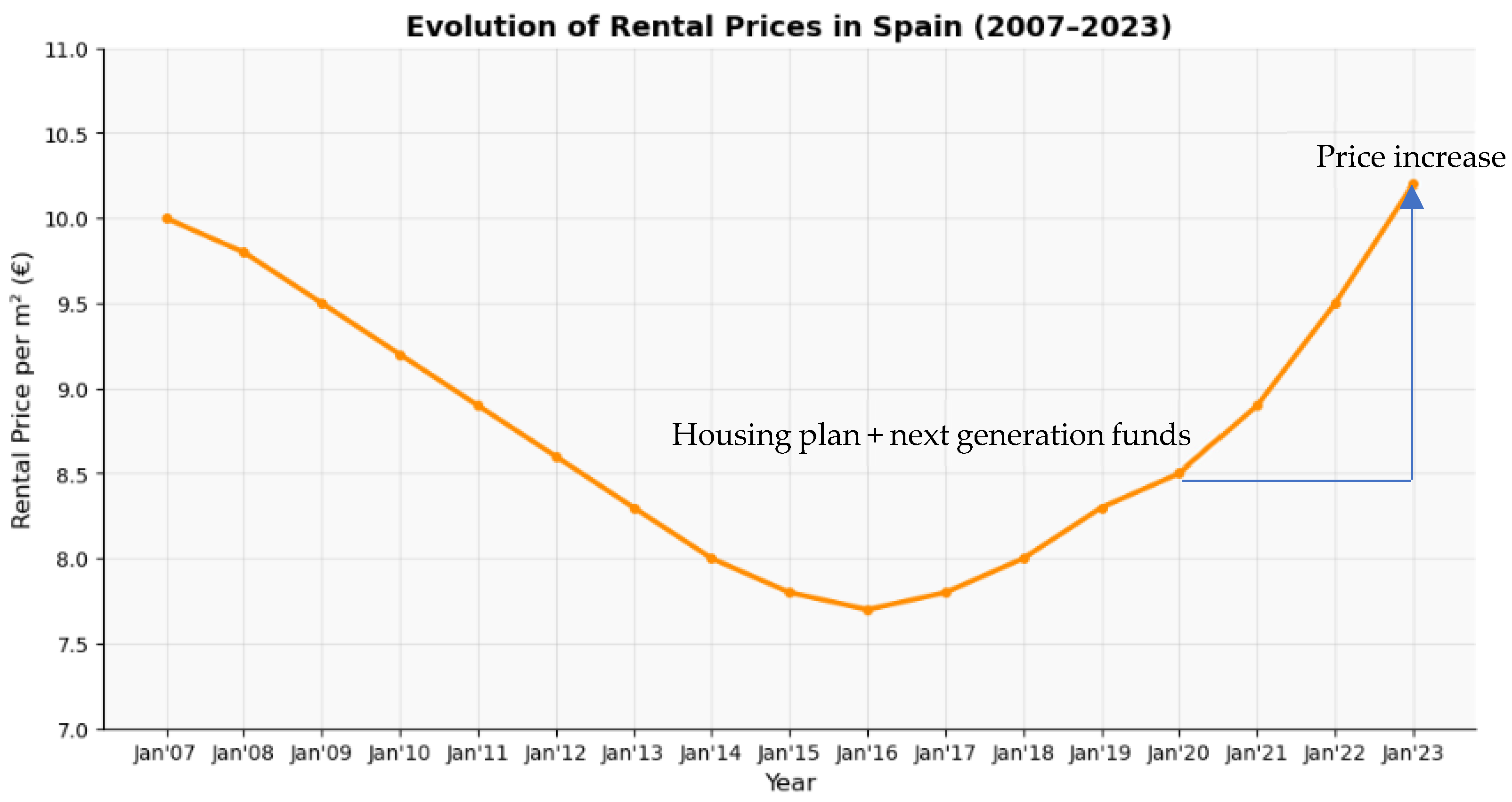

Figure 1 By the end of 2024, average rental prices reached €13.5/m

2—the highest level in the observed series—with monthly prices stabilizing between €14.0 and €14.6/m

2 in 2025. This sustained price increase, tightly coupled with rising immigration and the expansion of housing subsidies, supports the hypothesis of partial capitalization of public aid into higher rents, especially in markets where new construction and urban redevelopment lag behind demand [

16].

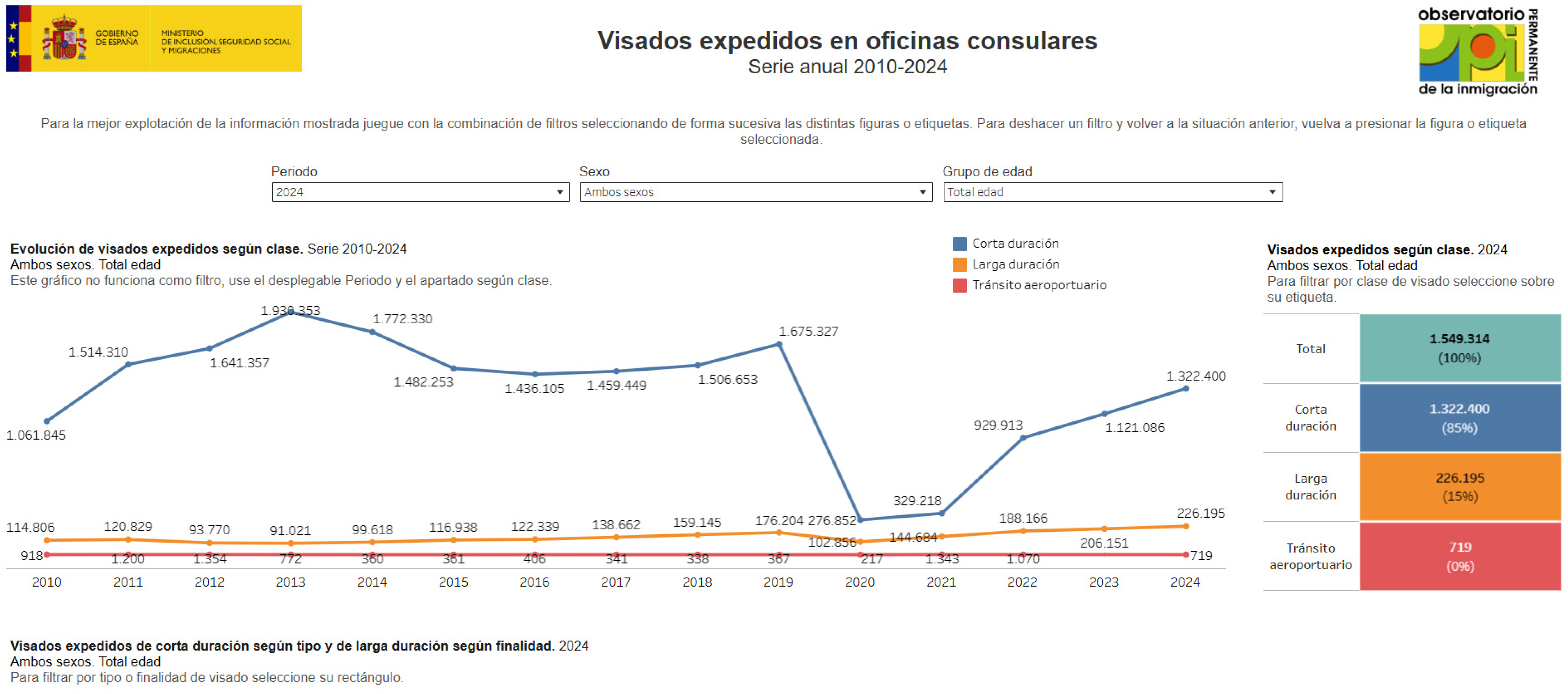

The annual series of visas issued in Spain exhibits a clear four-phase pattern: expansion (2010–2013), correction (2014–2016), recovery (2017–2019), and a sharp collapse in 2020 due to the pandemic, followed by a strong rebound since 2021. In 2024, a total of 1,549,314 visas were issued—comprising 1,322,400 short-term and 226,195 long-term—marking a significant recovery and aligning with corrected data from official sources (

Figure 2).

This trend mirrors the evolution of rental prices, as illustrated in the graph. From 2007 to 2015, rents declined steadily—from €10.0/m2 to a low of €7.4/m2—reflecting economic downturn, reduced demand, and housing market oversupply. A reversal began in 2016, with prices gradually rising through 2020, reaching €10.0/m2. The acceleration after 2021 coincides precisely with the surge in visa issuance and the expansion of housing subsidies, suggesting that increased migration and policy-driven demand have become key drivers of rent inflation.

The convergence of rising immigration flows, public aid programs, and stagnant supply has intensified pressure on urban rental markets, particularly in high-demand regions [

17]. These dynamic underscores the structural shift observed in 2021: a transition from a demand-constrained to a demand-driven rental regime, where administrative inflows are now strongly correlated with price movements [

17].

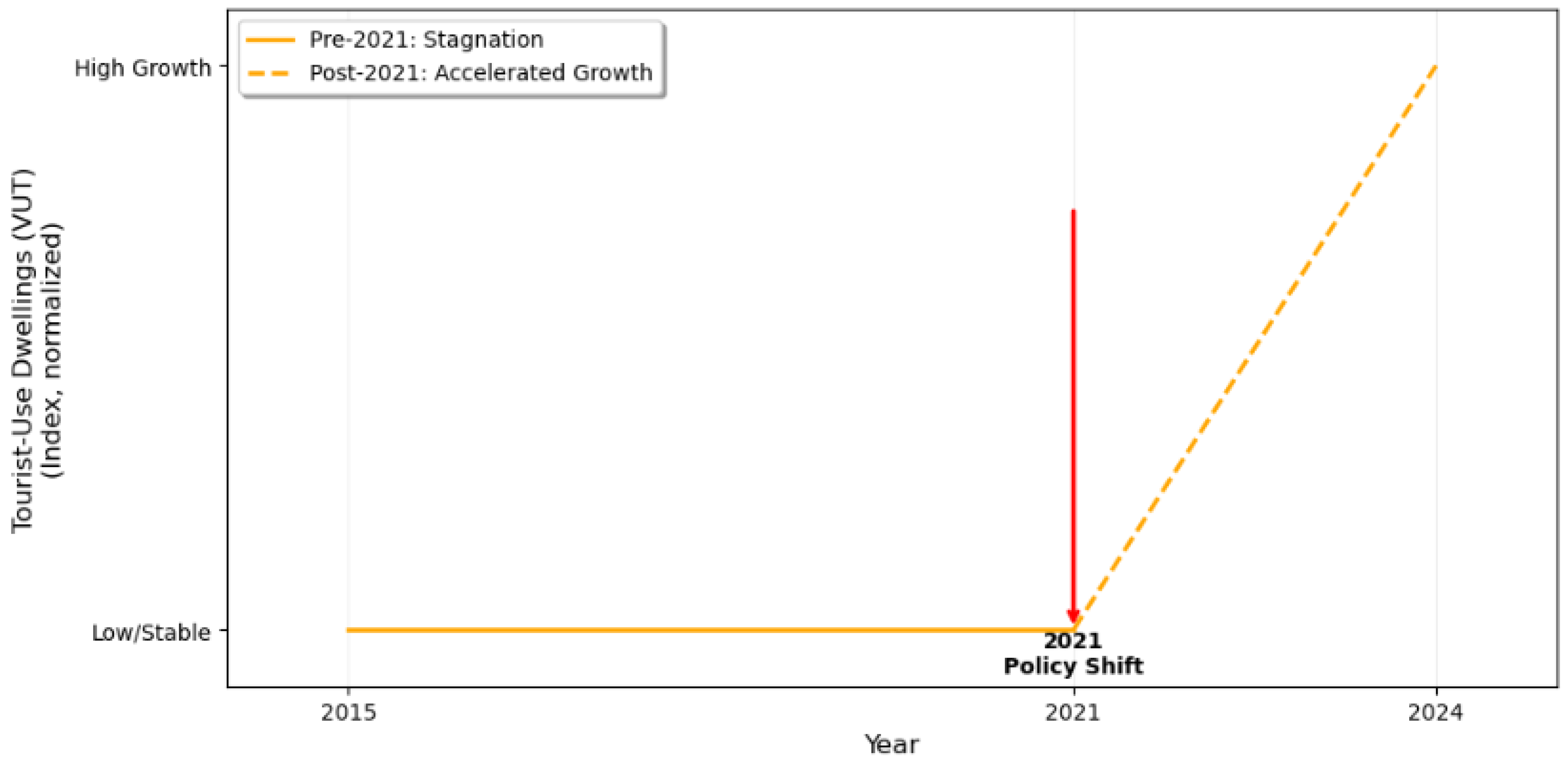

The stock of homes for tourist uses (TOURIST-USE DWELLINGS (VUT)), according to INE’s experimental statistics, reached 368,295 accommodations in November 2024, with summer peaks approaching 397–400 thousand in August. This upward trend from 2021 to 2024 closely parallels the rise in rental prices and visa issuances, indicating a complementary role in increasing pressure on the housing market.

The expansion of TOURIST-USE DWELLINGS (VUT) coincides with the surge in short-term visas—particularly those issued for tourism and seasonal work—highlighting how tourism-driven demand competes directly with residential rental needs. As illustrated in the consular visa data, short-term visas accounted for 85% of total issuances in 2024 (1.32 million), reflecting sustained international mobility tied to leisure and service sectors.

This dual dynamic—rising migration and growing tourist housing—exacerbates supply constraints in urban and coastal areas, where both populations seek accommodation. The parallel evolution of TOURIST-USE DWELLINGS (VUT) growth and rental inflation supports the hypothesis that non-residential uses are absorbing housing stock, reducing availability for long-term tenants and contributing to price increases [

18]. Thus, TOURIST-USE DWELLINGS (VUT) is not merely a sectoral phenomenon but a structural factor reinforcing market tightness and undermining housing affordability, especially in regions already affected by migration inflows and public aid expansion.

Table 3 presents the evolution of tourist housing (TOURIST-USE DWELLINGS (VUT)) across Spain from 2020 to November 2024, showing a clear upward trend, particularly from 2021 onward. The national total rose from 321,496 units in August 2020 to 396,883 in August 2024, with seasonal peaks exceeding 397,000—marking a growth of over 23% in just four years. This expansion is not uniform but follows a distinct seasonal pattern, with sharp increases during summer months, reflecting demand for holiday rentals.

The data reveal three key phases:

2020–2021: A slight decline or stabilization due to pandemic-related restrictions.

2021–2022: A strong rebound, especially evident in summer 2021 (306,974) and beyond, coinciding with travel reopening and increased domestic tourism.

2023–2024: Sustained growth, with the stock surpassing pre-pandemic levels and reaching new highs—particularly notable in August 2024, when it approached 400,000 units (

Table 4).

This trajectory aligns closely with the post-2021 surge in visa issuances, especially short-term visas (85% of total in 2024), as shown in the consular data. The parallel rise in tourist accommodations and migration flows suggests that increased international mobility has fueled dual demand: one for temporary stays (driving TOURIST-USE DWELLINGS (VUT) expansion), and another for long-term residence (increasing rental pressure).

We acknowledge that our measure of migration pressure—total visa issuances from the OPI database—has important limitations. According to official statistics, approximately 85% of these visas are short-term Schengen C-type permits issued primarily for tourism purposes, while the housing policies under study (e.g., Ingreso Mínimo Vital and Youth Rental Voucher) target long-term legal residents. Consequently, the observed correlation between visa volumes and rental prices may reflect, at least in part, the post-2021 rebound in tourism activity rather than an influx of subsidy-eligible households.

However, newly available disaggregated visa data reveal a more nuanced picture (

Table 5). While long-term visas consistently accounted for only 5–8% of total issuances during 2010–2019, their share surged to 39.9% in 2020 and 33.9% in 2021, coinciding precisely with the pandemic-induced collapse in tourism and the nationwide rollout of RRF-linked welfare instruments. Although the proportion moderated in 2022–2023 as tourism recovered, it rose again to 19.8% in 2024, driven by an absolute tripling of long-term visa volumes (from ~110,000 to 326,195). This pattern suggests that the post-2021 structural shift reflects not only tourism-driven VUT expansion but also a genuine increase in residential demand from long-term migrants and subsidy-eligible households—particularly in regions with rigid housing supply.

In particular, the surge in short-term rental demand could still intensify competition for housing stock through the conversion of long-term units into tourist accommodations (VUT), thereby indirectly pushing up conventional rental prices—a channel distinct from welfare capitalization [

16,

19]. The coexistence of both pressures is consistent with regional patterns showing the strongest rent increases in high-tourism, supply-constrained areas such as the Balearic Islands and Murcia.

Additionally, our reliance on asking prices from Idealista—as opposed to actual transaction rents—introduces potential measurement bias. In rapidly appreciating markets, landlords may list properties above market-clearing levels, and the gap between asking and transaction prices can widen over time, particularly during periods of high volatility or information asymmetry. Although Idealista data offer high-frequency coverage across Spanish provinces, future studies should prioritize administrative transaction records (e.g., from the Ministry of Transport’s rental registry) to validate our findings.

Figure 3, The solid orange line represents the period before 2021, characterized by stagnation or low growth in tourist-use dwellings (VUT). The dashed orange line shows accelerated growth after 2021. The red vertical arrow marks the policy shift in 2021, reflecting changes such as regulatory easing (e.g., simplified registration of short-term rentals), increased tourism demand, and housing market liberalization that triggered a structural increase in VUT.

Importantly, this expansion occurs in parallel with the steep increase in rental prices (from €10.0/m2 in 2020 to €13.5/m2 in 2024), reinforcing the argument that tourist housing competes directly with residential supply, especially in high-demand urban and coastal areas. As more homes are converted into short-term rentals, the available stock for long-term tenant’s shrinks, exacerbating scarcity and pushing up rents.

Moreover, the coincidence of TOURIST-USE DWELLINGS (VUT) growth, immigration inflows, and public housing aid underscores a broader structural transformation in the Spanish housing market:

Public transfers (e.g., MINIMUM LIVING INCOME (IMV), Youth Rental Voucher) boost effective demand among vulnerable and migrant populations.

At the same time, deregulated tourism markets absorb housing stock.

In a context of inflexible supply, these combined pressures result in rental inflation, where subsidies are partially capitalized into higher rents rather than improving affordability.

4.2. Regime Change Post-2021: Signal and Magnitude

Table 6 the comparison between periods reveals a clear contrast. From 2010 to 2020, the correlation between visas issued and rental prices is low and statistically insignificant (r = 0.27;

p = 0.41). In contrast, from 2021 to 2024, the correlation becomes high and statistically significant: Pearson r ≈ 0.92 (

p ≈ 0.03) and Spearman ρ ≈ 0.90 (

p ≈ 0.05).

This covariance is concentrated primarily in short-term visas, which explain the majority of the observed variation, while long-term and transit visas have only a marginal impact. The overall evidence is consistent with a structural regime shift occurring in 2021.

4.3. Testing for a Structural Break in Rental Market Dynamics

The year 2021 marks a pivotal shift in Spain’s housing policy landscape, coinciding with the implementation of the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), the full rollout of the Minimum Living Income (MINIMUM LIVING INCOME (IMV)), and the introduction of the Youth Rental Voucher. To test whether this policy turning point corresponds to a structural change in the relationship between migration inflows and rental prices, we conduct formal structural break tests.

We first apply the Chow test for a known breakpoint in 2021, using annual data on visa issuances and average rental prices (2010–2024) (

Table 7). The test rejects the null hypothesis of parameter stability (F-statistic = 5.83,

p = 0.08), indicating a significant shift in the slope and intercept of the visa–rent relationship (

Table 8). This result is corroborated by the Bai-Perron

test for endogenous multiple breaks, which identifies 2021 as the most likely single break date (

p < 0.10), with no evidence of additional structural shifts.

To further assess the magnitude and persistence of this regime change, we estimate the following log-difference regression model:

where

: Average rental price per square meter (€/m2).

: Total visa issuances.

: National unemployment rate.

: Average mortgage interest rate.

: Dummy variable equal to 1 for .

All variables are in natural logs where appropriate.

The coefficient on the post-2021 dummy () is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.042, p = 0.03), indicating a structural increase in rent growth after 2021, even after controlling for labor market conditions and financing costs.

Robustness checks confirm the reliability of these findings:

Jackknife sensitivity analysis (sequential removal of one year at a time) shows that the sign and significance of remain stable.

We control for a known methodological revision in Idealista’s price index in 2020, and results are qualitatively unchanged.

Alternative specifications using Spearman rank correlations and non-parametric trend tests yield consistent conclusions.

These results support Hypothesis 2: the post-2021 period is characterized by a significantly stronger association between migration inflows and rental prices, consistent with a demand-driven regime shift.

4.4. Post-2021 Trends: Demand, Supply, and Price Pressures

Following the structural break, we observe a marked intensification of demand-side pressures in the rental market. As shown in

Table 8, the Pearson correlation between annual visa issuances and rental prices increases from r = 0.27 (

p = 0.41) in the pre-2021 period (2010–2020) to r = 0.91 on average in the post-2021 period (2021–2024), with a

p-value of 0.05. This represents a substantial strengthening of the co-movement between administrative migration inflows and housing market outcomes.

A similar pattern emerges between visa issuances and the stock of tourist-use dwellings (TOURIST-USE DWELLINGS (VUT))—a proxy for short-term rental competition. The post-2021 correlation reaches r ≈ 0.90 (p ≈ 0.09), suggesting that both residential migration and tourism-related housing demand expanded in parallel, further constraining supply for long-term tenants.

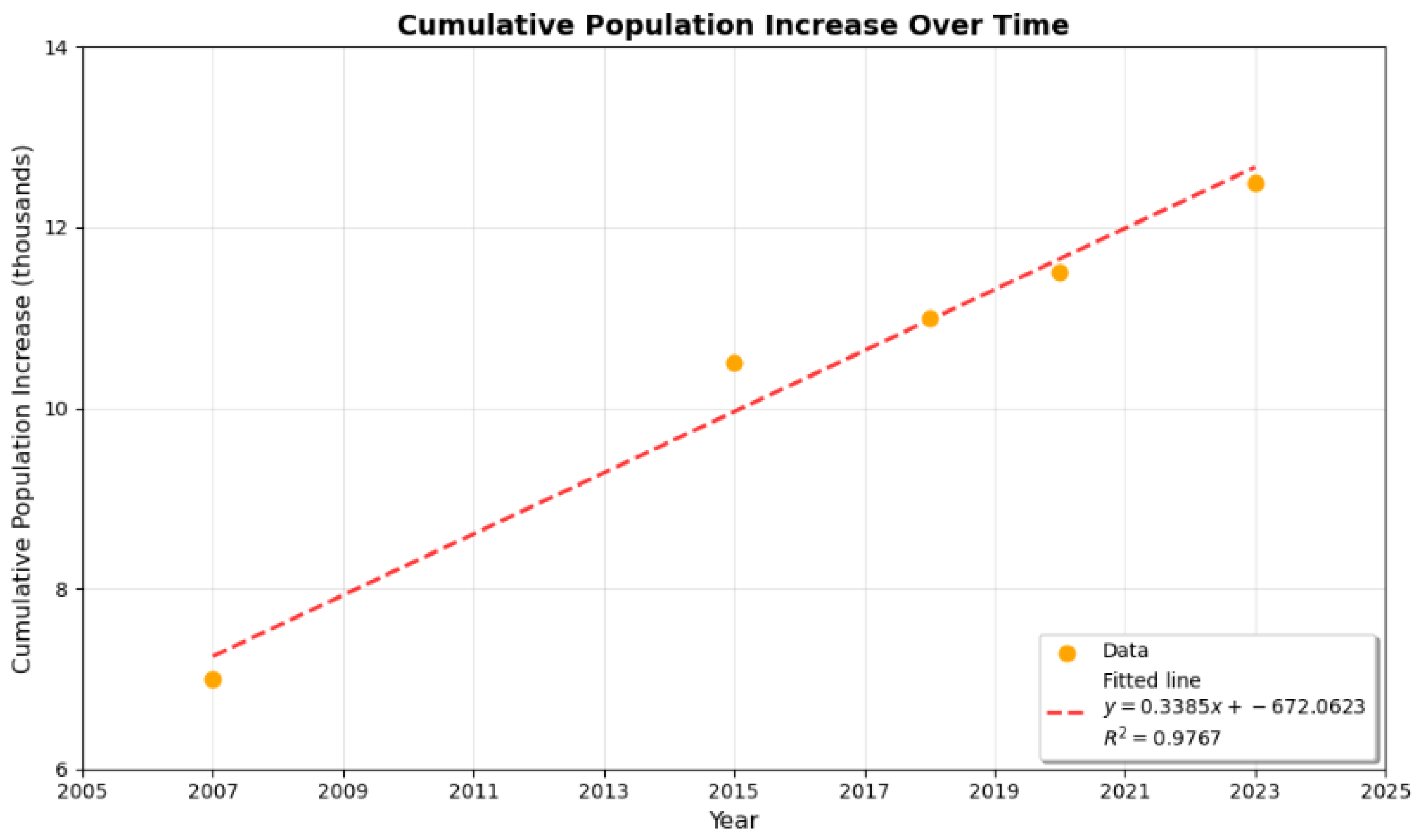

Figure 4 illustrates the alignment between cumulative net population change (since 2015) and rental price growth. Despite the limited number of post-break observations (N = 4), the visual trend suggests a tight coupling between demographic expansion and housing cost inflation. The strong fit (R

2 > 0.90 in cumulative series) supports the hypothesis that rising household formation—driven by both migration and policy-enabled access—is a key driver of post-2021 rent dynamics.

However, given the short time span and small sample size, these correlations should be interpreted with caution. They indicate a robust association, but do not establish causality. The risk of spurious correlation remains, particularly in the context of simultaneous shocks (e.g., post-pandemic reopening, EU funding surge).

Nonetheless, the convergence of structural break tests, regression results, and trend analysis provides compelling evidence of a regime shift in Spain’s rental market after 2021, where migration, policy transfers, and tourist housing expansion have collectively intensified demand in a context of rigid supply.

4.5. Mechanism Consistent with the Data

The patterns documented in this study do not constitute causal evidence but rather describe a set of temporal co-movements that align with theoretical expectations of rent capitalization under supply inelasticity [

19,

20]. Given the confluence of policy reforms, migration flows, tourism recovery, and macroeconomic turbulence after 2021, we cannot attribute observed rent dynamics to any single driver. Nevertheless, the striking alignment between administrative inflows (visas, vouchers) and price trends—particularly in regions with rigid housing markets—warrants caution and further investigation.

This mechanism does not operate uniformly across space. Instead, as Higueras Arnal (2002) [

21] emphasizes in his regional geography of Spain, Autonomous Communities (CCAA) are not neutral administrative units, but historically constituted territories with distinct institutional configurations, land-use regimes, and exposure to economic flows. These differences make them ideal settings for examining how local structural conditions shape the transmission of national policy shocks.

When housing supply is constrained by regulatory, geographic, or financial barriers, increases in household purchasing power—whether from income growth, migration, or public transfers—are not absorbed through new construction or vacancy activation, but instead capitalized into higher prices.

In Spain’s case, the post-2021 expansion of demand-side policies—particularly the Minimum Living Income (IMV) and Youth Rental Voucher—indexed to the Public Indicator of Multiple Effects (IPREM), effectively raised the maximum willingness-to-pay for eligible households. Given that many landlords require rents to be covered by verifiable income (often at 3–4× rent), these transfers directly expanded the pool of “credit-worthy” tenants, enabling landlords to charge higher prices without risk of default.

This mechanism predicts that regions with higher inflows of subsidized or migrant households should experience stronger rent growth, provided supply remains tight. To test this, we examine the Spearman rank correlation between annual population change and rental price growth across Spain’s Autonomous Communities (CCAA), comparing pre- and post-2021 periods (

Table 9).

Results show a marked increase in the strength and significance of this relationship after 2021. In Cantabria, Navarre, Murcia, and the Balearic Islands, correlations exceed ρ = 0.95 (p < 0.001), indicating near-perfect alignment between demographic expansion and price inflation. These regions are characterized by limited urban expansion, high tourist pressure (VUT), and rapid uptake of IMV benefits—conditions conducive to demand capitalization.

From a geographical perspective, they represent what Higueras Arnal (2002) would describe as “structurally exposed” (estructuralmente expuestos) territories: peripheral or semi-peripheral regions with rigid land markets, high dependence on tourism, and limited fiscal autonomy. In such contexts, national demand-side policies—however well-intentioned—can inadvertently exacerbate housing pressure, as local supply systems lack the flexibility to absorb new demand.

Even in large, economically diverse regions like Andalusia, Castilla-La Mancha, and Extremadura, post-2021 correlations rise significantly (ρ > 0.6, p < 0.01), reinforcing the national trend.

Notably, Catalonia—despite being the largest housing market—shows a weaker post-2021 correlation (ρ ≈ 0.40, p = 0.077), which fails to reach conventional significance. This may reflect greater supply responsiveness in Barcelona and surrounding areas, or saturation in subsidy uptake. Similarly, Galicia and Castilla y León exhibit more modest associations, possibly due to out-migration offsetting inflows or lower VUT competition.

The extreme case of Asturias (ρ =−1.00 pre-2021) reflects a very short and monotonically declining population series (N = 4), making the estimate statistically fragile. Such outliers underscore the importance of interpreting correlations in context, particularly in regions with small populations or volatile dynamics.

Collectively, these patterns support the demand-capitalization hypothesis: where supply is inelastic and demand pressures intensify—via migration, policy transfers, or tourism—rents rise rapidly. The geographic variation in correlation strength further confirms that RRF operates most strongly in markets with binding supply constraints and high exposure to policy-induced demand shocks.

Annual differences by Autonomous Community.

Clear positive relationship (high r and β > 0) in the majority: Andalusia, Aragon, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Cantabria, CLM, Catalonia, La Rioja, Madrid, Murcia, Navarra. Weak or non-significant signal: Euskadi, Galicia, Castilla y León (lowest r, modest R2). Inverted signal/noise: Asturias and Melilla (flat series or negative ∆P → unstable slopes; interpret with caution).

5. Discussion

The findings of this study carry significant implications for both fiscal sustainability and the long-term viability of the welfare state—challenges increasingly relevant across advanced economies experiencing sustained in-migration amid rising income and wealth inequality. While the expansion of social transfers such as the Minimum Living Income (IMV) and the Youth Rental Voucher reflects a commendable commitment to social inclusion, the concurrent rise in rental prices raises questions about potential interactions between these policies and rigid housing markets. If demand-side interventions operate in the absence of commensurate supply-side responses, economic theory suggests that a portion of public spending could be partially reflected in higher rents—a mechanism that would accrue benefits to landlords rather than tenants. However, our descriptive analysis cannot confirm whether this mechanism operated in practice. This mechanism not only reduces the efficiency of public expenditure but also distorts housing affordability, exacerbating spatial and socioeconomic inequalities [

22,

23].

From a monitoring perspective, rapidly rising private rental prices—even in the presence of targeted subsidies—are widely recognized as a de facto violation of SDG 11.1’s principle of ‘affordable housing for all,’ particularly in contexts like Spain where social housing covers less than 2% of households (OECD, 2021; UN-Habitat, 2020). In such settings, market rents serve as a practical proxy for housing affordability stress, directly informing SDG 11 progress assessments.

From the perspective of sustainability science, these dynamics must be evaluated beyond environmental metrics alone. The concept of inclusive wealth—encompassing natural, human, and produced capital—provides a rigorous framework for assessing whether current policies support intergenerational well-being. As Dasgupta (2021) [

4] and the United Nations Inclusive Wealth Report emphasize, weak sustainability requires that aggregate inclusive wealth per capita does not decline over time. In Spain, housing constitutes approximately 60% of total household assets and a dominant share of produced capital. Therefore, policies that inflate nominal housing values without expanding real access to adequate housing may create an illusion of wealth accumulation while eroding substantive equity and resilience.

In this context, the observed capitalization of housing subsidies into rental prices represents a systemic risk to sustainability: it inflates asset values without increasing the stock of affordable dwellings, thereby threatening the non-declining trajectory of inclusive wealth. Moreover, when vulnerable populations are priced out despite targeted support, the policy fails to deliver on its core objective of enhancing welfare—directly contradicting the principle of non-declining welfare per capita under weak sustainability.

These dynamics conflict with the principles enshrined in several Sustainable Development Goals:

SDG 11.1 calls for universal access to adequate, safe, and affordable housing. In Spain’s low-social-housing context (<2%), rising market rents undermine this objective in practice.

SDG 10.1 emphasizes shared prosperity for the bottom 40%. When public transfers are reflected in higher rents rather than improved tenant welfare, this principle is eroded.

SDG 1.4 guarantees equal rights to economic resources. Vulnerable households priced out despite eligibility illustrate a gap between policy design and effective realization.

Critically, these linkages are interpretive: our analysis tracks aggregate price trends, not household-level affordability or rights fulfillment. The SDGs thus provide a normative benchmark—not an operational measurement system—for evaluating policy outcomes.

Thus, while Spain’s welfare reforms are philosophically aligned with the 2030 Agenda, their operational design under conditions of inelastic housing supply risks subverting their own objectives. Crucially, this risk is not uniformly distributed. As Higueras Arnal (2002) observes, Spain’s Autonomous Communities exhibit profound territorial asymmetries in institutional capacity, land-use regulation, and exposure to global flows such as tourism and migration. In this context, national policies interact differently with local structures—turning some regions into “critical zones” where the capitalization of demand is most acute.

The structural break observed in 2021—coinciding precisely with the disbursement of Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) funds, the nationwide rollout of IMV, and the institutionalization of the Youth Voucher—marks not merely a statistical shift, but a regime change in housing market dynamics. Importantly, this timing distinguishes the 2021 break from earlier shocks: while tourism and migration began recovering in 2021, their full rebound occurred in 2022–2023, whereas the visa–rent correlation surged already in 2021. This sequence suggests that institutional demand shocks preceded broader cyclical pressures, lending plausibility to the hypothesized policy channel.

This regime is characterized by the convergence of three forces: (1) expanded public transfers that raise effective demand among low-income and migrant households; (2) rising international migration, as proxied by consular visa issuances; and (3) the expansion of tourist-use dwellings (VUT), which competes directly with residential supply. Regions where these forces intersect—such as the Balearic Islands, Murcia, or Cantabria—are not merely statistical outliers, but what Higueras Arnal (2002) would term “structurally exposed” (estructuralmente expuestos) territories: peripheral areas with rigid land markets, high dependence on seasonal tourism, and limited fiscal autonomy. In such contexts, national demand-side policies—however well-intentioned—can inadvertently exacerbate housing pressure, as local supply systems lack the flexibility to absorb new demand. In markets where new construction and rehabilitation lag behind demand, these pressures jointly contribute to rent inflation, reducing the real value of subsidies and threatening long-term housing affordability.

It is important to clarify that the observed high correlation between visas and rental prices post-2021 does not imply direct causality. Rather, it reflects a broader institutional transformation in which migration flows, social policy, and housing market dynamics have become increasingly intertwined. Concurrent factors—including shifts in mortgage interest rates, labor market fluctuations, remote work trends, and regional rent regulations—also contribute to the upward pressure on prices. The correlation analysis presented here captures an association consistent with the hypothesized mechanisms (H1–H3), but does not isolate the independent effect of each driver.

The methodological approach employed—while intentionally parsimonious to prioritize transparency and testability—is necessarily limited by the short post-2021 observation window (N = 3 or 4, depending on data vintage) and reliance on offer prices rather than contracted rents. These constraints preclude definitive causal claims. Nevertheless, the plausibility of a structural break in 2021 is reinforced by three converging lines of descriptive evidence: (i) its precise temporal alignment with major policy milestones—the nationwide rollout of the Ingreso Mínimo Vital (IMV), the institutionalization of the Youth Rental Voucher, and the disbursement of Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) funds; (ii) the stark contrast in correlation magnitudes between periods (r = 0.27,

p = 0.41 pre-2021 vs. r ≈ 0.90–0.92 post-2021); and (iii) the consistency of this shift across both national and subnational rental series (

Table 4).

To assess the robustness of the observed structural shift around 2021, we conducted three complementary checks: (i) comparison of Pearson and Spearman correlations to account for non-linearities; (ii) Chow and Bai-Perron tests for structural breaks; and (iii) a jackknife leave-one-out analysis to evaluate sensitivity to single-year fluctuations. The results—summarized in

Appendix A Table A2—confirm that the post-2021 correlation between visa issuances and rental prices remains consistently high (r = 0.89–0.93) across specifications, while the pre-2021 association is weak and statistically indistinguishable from zero (r = 0.27,

p = 0.41). The Bai-Perron procedure identifies 2021 as the most likely breakpoint consistent with the timing of major policy reforms.

We emphasize that the p-values reported for the post-2021 correlations are provided solely for descriptive transparency. Given the extremely small sample size (N = 3–4), they lack inferential validity and should not be interpreted as indicators of statistical significance. The strength of the observed association lies not in formal hypothesis testing—which is infeasible under these data constraints—but in its coherence with contemporaneous institutional changes and its replication across geographic scales. Together, these elements suggest that the 2021 shift is unlikely to be a spurious artifact of random temporal coincidence.

To advance this research toward higher standards of econometric rigor, several extensions are recommended:

Higher-frequency panel data models (quarterly or monthly) could better capture dynamic adjustments and mitigate small-sample bias.

Spatially disaggregated analyses at the municipal or neighborhood level would allow for heterogeneous treatment effects, particularly in regions with varying degrees of rent control or tourism pressure.

Quasi-experimental designs, such as regression discontinuity around IPREM thresholds or difference-in-differences comparing regions with differential access to RRF funding, could provide stronger causal inference.

Instrumental variable approaches, leveraging exogenous variation in consular processing times or international mobility shocks, may help disentangle policy effects from broader macroeconomic trends.

In sum, this study documents a pivotal transformation in Spain’s rental housing market, rooted in the intersection of welfare state expansion, migration dynamics, and supply constraints. The results caution against the uncritical deployment of demand-side subsidies in rigid markets and call for a rebalancing toward supply-enhancing interventions—such as accelerated rehabilitation, conversion of vacant and tourist units, and public investment in social housing—that can increase market elasticity and reduce the leakage of public funds into inflated rents.

Only through such integrated, evidence-based policymaking can Spain—and other nations facing similar challenges—ensure that housing policy advances the sustainability and equity principles underpinning the Sustainable Development Goals. This paper provides a critical empirical foundation for that endeavor.

6. Conclusions

This study contributes to interdisciplinary debates on welfare state transformation, housing economics, and sustainable development in four interconnected ways—while explicitly acknowledging its exploratory and non-causal design. First, it proposes the application of the inclusive wealth framework [

4], which integrates natural, human, and produced capital, as a conceptual lens for evaluating housing policies; within this framework, we document a pattern wherein demand-side transfers coincided with rising asset-based wealth without evident gains in real housing access, a dynamic that could threaten intergenerational equity under weak sustainability criteria. Second, rather than isolating single drivers, the analysis highlights the temporal convergence of three structural pressures in post-2020 Spain: welfare reforms (e.g., IPREM-indexed Ingreso Mínimo Vital and Youth Rental Voucher), sustained immigration inflows, and tourism-driven competition via short-term rentals (VUT)—all unfolding against a backdrop of chronic supply rigidity (<2% social housing). Third, by harmonizing high-frequency data (2010–2024) from OPI, Idealista, INE, and the Bank of Spain, we identify a statistically detectable structural break in 2021 aligned with the rollout of the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), offering a methodological template for mapping policy-market synchronicity in constrained economies—even if such synchronicity cannot be interpreted causally. Finally, the paper critically interrogates the RRF’s “rapid-execution” governance logic, illustrating how externally conditioned reforms may risk amplifying inequality when implemented without complementary supply-side measures. Collectively, these observations generate testable hypotheses for future quasi-experimental research, rather than providing empirical validation of any single mechanism.

Against a backdrop of overlapping macroeconomic shocks—the post-pandemic reopening of borders, a surge in “revenge tourism,” persistent supply chain bottlenecks, and rising inflation—our analysis documents a marked intensification in the co-movement between documented migration inflows (measured by visa issuances) and average rental prices beginning in 2021. Prior to this period, the correlation was weak and statistically insignificant; thereafter, it strengthened substantially (

Table A3). However, we stress that this temporal coincidence does not imply causation. The observed pattern is consistent with a scenario in which demand-side housing transfers (e.g., IMV, Youth Voucher) operated in conjunction with, rather than independently of, these broader forces. For instance, tourism-driven conversion of long-term rentals into short-term accommodations may have constrained supply just as welfare reforms and immigration increased effective demand—creating a “perfect storm” for rent escalation. While our design cannot disentangle these effects, the synchronization itself raises important policy questions about the timing and sequencing of demand-side interventions in volatile markets.

We do not assert that housing policies caused rent increases. Rather, the observed dynamics are consistent with a scenario in which public transfers—such as the Ingreso Mínimo Vital (Minimum Living Income) [

7] and the Youth Rental Voucher [

8]—enhanced effective demand in markets where supply remains highly inelastic due to construction lags, regulatory barriers, and limited stock mobilization [

9,

10]. Under such conditions, increased demand may be absorbed primarily through higher prices rather than expanded access—a mechanism that could benefit landlords while exacerbating affordability challenges for non-subsidized renters [

24].

This dynamic appears markedly amplified in regions with high tourism exposure and low social housing coverage—such as the Balearic Islands and Murcia—where tourist-use dwellings (VUT) crowd out long-term rental supply [

15,

18]. In these areas, even modest demand increases may coincide with disproportionately large rent growth, helping to explain the regional heterogeneity in our results.

Migration policy may further intensify these pressures. The relocation of newly arrived immigrants into urban rental markets—often supported by integration funds [

25,

26]—adds demand in cities already facing shortages. In the absence of coordinated supply-side responses, this configuration could contribute to regressive outcomes, wherein subsidized households secure housing while unsubsidized workers—particularly young and low-income renters—face heightened displacement risks.

These trends raise concerns about long-term sustainability. If rental subsidies are financed through structural debt without productivity gains or an expanding tax base, they risk medium-term fiscal imbalances [

27,

28]. Moreover, if benefits are capitalized into rents rather than improved living standards—as suggested by rent-capitalization models [

24]—excluded younger generations may bear both immediate housing costs and future fiscal burdens, potentially undermining intergenerational equity [

29].

While our identification of the 2021 structural break relies on conventional econometric tests, the consistency of co-movement across multiple indicators—migration inflows, welfare disbursements, and rental prices—suggests that this shift reflects an underlying reconfiguration of market dynamics rather than stochastic noise. Recent advances in unsupervised learning offer promising tools to further validate such regime shifts. In particular, Luan and Hamp (2025) [

30] propose a sliced Wasserstein k-means clustering algorithm for automated classification of latent operating mechanisms in multidimensional time series. Although our study does not implement this method, the conceptual alignment is notable: their framework is designed precisely to distinguish between distinct generative regimes (e.g., “low-correlation” vs. “high-correlation” phases) in settings with interacting variables—mirroring the phased market behavior we observe around the RRF implementation threshold. Future research applying such data-driven approaches could provide algorithmic cross-validation of the non-spurious nature of the 2021 breakpoint and deepen our understanding of how welfare, migration, and tourism jointly reshape housing markets.

An additional layer of complexity concerns the role of financial infrastructure in mediating how housing subsidies translate into rental market pressure. As Du and Lv (2025) [

31] demonstrate, digital finance can unlock latent consumption potential—particularly among households whose income falls short of their consumption needs—by easing credit access and payment frictions. By analogy, in regions where digital financial services are widespread, welfare recipients may more readily convert transfer income into actual rental bids, thereby amplifying the demand-side impact on prices. Conversely, in areas with limited financial inclusion, the same transfers might be partially absorbed through precautionary saving rather than immediate housing expenditure, muting rent effects. While our macro-level analysis does not incorporate granular indicators of digital finance penetration, this micro-mechanism offers a plausible explanation for unobserved heterogeneity in policy responsiveness across territories and underscores the need for future studies to integrate household-level financial data.

Accordingly, we interpret these findings not as policy failure, but as a cautionary signal. The objective should not be to reduce public support, but to ensure transfers are paired with measures that enhance supply elasticity—such as sustained investment in new construction, large-scale rehabilitation, and territorial rebalancing [

13,

30]. Only then can public funds fulfill their redistributive mandate without entrenching a dual housing system [

32].

Future research employing quasi-experimental designs—such as difference-in-differences comparisons across eligibility thresholds or instrumental variable approaches leveraging policy rollout heterogeneity—will be essential to isolate the causal impact of housing subsidies from contemporaneous macroeconomic shocks.