1. Introduction

As urban populations continue to grow steadily, cities are increasingly highlighting numerous social and economic vulnerabilities, which have been further exacerbated by the effects of climate change [

1]. Indeed, cities are areas particularly affected by impacts related to overheating, the presence of excess water, or the lack of it for an extended period of time. However, they are places to identify new paradigms and experiment with sustainable living practices, improving the environmental resilience of cities [

2,

3,

4]. One aspect worth dwelling on is agricultural production within the city. Although Urban Agriculture (UA) is typically associated with rural suburban areas, the productive city has always existed. In 2000, 200 million urban residents produced food for the urban market, providing 15–20 percent of the world’s food [

5]. Even in our current era of climate change, in which global food production is involved, cities can help reinforce strategies for environmental resilience and sustainable development [

6,

7,

8].

Regardless of geographic context, UA practices are based on cultural traditions and often represent strong links to practices used in their countries of origin, helping to preserve knowledge, social ties, and respect for the natural environment. UA has always been present in cities, but in different ways depending on the period and circumstances and has therefore taken on different roles over time. Since the development of the industrial city, agriculture has been gradually removed from the city, only to make a comeback, including with government programs to limit food security risks and for patriotic support (especially during the world wars in Europe), when gardens, parks, and squares became useful sites for cultivation. Only since the 1970s, UA has been associated with local development, social integration and environmental education programs, with actions led by community and environmental organizations [

9]. This has led to population involvement through participatory processes that have led to dietary integration, improved community life, and reduced inequalities.

There are several benefits, often inadequately exploited, ranging from improving the quality of housing and urban space, promoting biodiversity, reducing food miles (thus reducing the carbon footprint), and encouraging environmentally friendly behaviors. UA thus represents an effective interplay between food security, climate change, biodiversity and society [

10,

11,

12], or, from another perspective, it represents different ecosystemic services in terms of provisioning, support, regulation, and culture. UA represents a promising strategy for integrating green spaces into residential and working environments, while directly supporting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). By emphasizing food-producing plants, UA contributes to SDG 2 (

Zero Hunger) by enhancing community-level nutritional intake. At the same time, sustainable and resilient cultivation practices advance SDG 13 (

Climate Action) and SDG 12 (

Responsible Consumption and Production) through the provision of green infrastructure that mitigates climate change, fosters biodiversity, reduces waste, and improves air quality. Furthermore, UA also supports SDG 11 (

Sustainable Cities and Communities), reinforcing its role as a multifunctional approach to urban sustainability. It is for all of these reasons that UA is increasingly recognized as a strategic component for improving urban resilience [

13] and the development of sustainable cities. The benefits are therefore well known and increasingly represent a measure that can improve urban resilience and reduce vulnerabilities. But are they known to everyone? How aware are citizens? The presence of UA is a process that can be bottom-up, involving citizens using their own residential and/or appurtenant space, but it can take top-down forms, stemming from the activation of public administrations, and intercepting motivated citizens and offering on loan public spaces for cultivation, focusing on the social or self-growing benefits. In both cases, community involvement is crucial and necessary to find continuity between the two top-down and bottom-up approaches. An example of this type of initiative is the establishment of Agricultural Parks, which on the one hand allow for the enhancement of their multi-functional role (agriculture, use of the land by citizens, improvement of environmental conditions, etc.) and on the other hand are a tool for landscape and environmental protection. Despite the growing recognition of UA benefits for food security, environmental sustainability, and social inclusion, two main gaps persist in the literature:

Limited understanding of public awareness and perception on UA, which highlights the need to investigate the level of knowledge and acceptance in different urban and cultural scenarios.

Lack of comparative studies between governance models, which underscores the need to compare territories where UA emerges from civic initiatives versus those where it is promoted by public institutions.

As stated by Grebitus et al. [

14], to implement effective UA development policies and practices, it is essential to ensure a high level of social acceptance. For this reason, an in-depth understanding of citizens’ perceptions is required. As the experience of the Agropark project in the Netherlands shows, it ultimately collapsed because of strong opposition from the public and residents, as well as the media [

15]. Other experiences found a way to achieve the acceptability of the people involved. Based on 380 questionnaires administered in Bologna and reported in Sanyé-Mengual et al. [

16], focusing on community gardens, particular emphasis was placed on the ecosystem services provided by urban agriculture. According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [

17], the ecosystem approach reveals the contribution of urban agriculture to human well-being through multiple ecosystem services, from food provision to cultural and biodiversity support. Similarly, within the Mediterranean context, Langemeyer et al. [

18] reported comparable findings, highlighting that the most important aspects are related to “

aesthetic information”, “

relaxation and stress reduction”, “

entertainment and leisure”, and “

biophilia”. Moreover, the gardens belonging to this cluster are highly valued for their food provision, in terms of both quality and quantity. In line with these findings, a Berlin survey [

19] showed that urban agriculture projects with recreational or educational functions and public accessibility receive greater public support. Rooftop gardens are particularly valued, as they repurpose underused spaces for productive and recreational use. Consequently, even privately managed rooftop farms are less likely to be perceived as competing with other urban land uses than ground-level projects. Similar results were observed in other contexts, such as in a field survey conducted in a community garden in Seattle, USA, where the primary perceived services were cultural. These comprised freedom in placemaking, community interaction, place attachment, and well-being [

20]. Grebitus et al. [

21], employing a concept-mapping method based on a word association test, found that consumers generally do not feel well-informed about urban agriculture, which may indicate that improving consumer education on the topic could enhance the success of urban agriculture initiatives.

According to the typology of the questionnaire and the way questions are given, the responses could vary significantly from similar experiences; in our field survey, where we consider two specific contexts (Italy and Singapore), we found many similar but still different perceptions of UA compared to other previous studies.

2. Aims and Methodology

The study aims to investigate the perceived potentials and critical challenges of UA in two distinct geopolitical and climatic contexts: Italy and Singapore. The study was developed within the bilateral research project “

BIZE_UrFarm: Building Integrated Zero Emission Urban Farming towards sustainable farmscape in Milan and Singapore”, carried out jointly by the Politecnico di Milano and the Singapore Institute of Technology. Through a comparative analysis of policy frameworks, stakeholder perceptions, and cultural attitudes, the study identifies the barriers, drivers, and public opinions surrounding UA in both territories. The analytical process reflects the integration of multiple disciplinary perspectives: (i) urban studies and planning to provide the spatial and policy context for urban agriculture; (ii) environmental sociology to help frame perceptions and social imaginaries; (iii) social psychology supports the analysis of attitudes and familiarity; and (iv) survey research ensures methodological rigor in data collection and analysis. The aim is to investigate the potential level of social acceptance of agricultural production practices in urban contexts in order to guide evidence-based policies and interventions in the built environment that can benefit from public support and minimize situations of opposition, resistance, or delays in the implementation process [

22,

23]. To this purpose, the research design is articulated through four interdependent research questions (RQ):

RQ1: What design and architectural strategies characterize UA in response to the climatic, cultural, and technological contexts of Italy and Singapore?

RQ2: How do citizens in Italy and Singapore perceive and understand the benefits and challenges of UA within their respective urban environments?

RQ3: How do bottom-up and top-down governance models influence public perceptions, motivations, and levels of engagement in UA initiatives?

RQ4: What are the comparative potentials and limitations of integrating UA within dense urban fabrics in Italy and Singapore, considering diverse technological approaches and spatial typologies?

This sequence establishes a clear research process that starts from the contextual and design baseline (RQ1), moves to citizens’ perceptions through the cognitive and affective dimension of both territories (RQ2), then examines the role of governance models and institutional aspects to shape trajectories of adoption and diffusion (RQ3), and finally generates a comparative evaluation of potentials, barriers, and challenges (RQ4).

To this purpose, this study is structured into the following phases:

Phase 1: Territorial analysis to define climatic, urban, and policy frameworks related to UA in Italy and Singapore (

Section 3).

Phase 2: UA background to outline the conceptual foundations and applied strategies (

Section 4).

Phase 3: Survey design and cross-territorial results to capture perceptions, barriers, and strategic drivers of UA in both territories (

Section 5).

Phase 4: Discussion of the results to identify recommendations for context-sensitive strategies (

Section 6).

5. Survey Design and Cross-Territorial Results

This section aims to capture people perceptions, perceived benefits, obstacles, and implementation preferences regarding UA in Italy and Singapore. The online survey was selected as the most appropriate method due to its ability to collect standardized responses from a large and diverse sample, also ensuring anonymity and minimizing social desirability bias. Its self-administered format allowed for participants to respond independently, fostering more spontaneous and authentic input [

38]. The survey also facilitated cross-sectional analysis through descriptive statistics and cross-tabulations [

39]. In contrast, the qualitative methods of interviews or focus groups are better suited for exploring individual narratives or group dynamics within smaller, more technical samples [

38]. Moreover, these approaches require direct facilitation, which can introduce moderator bias.

5.1. Survey Design

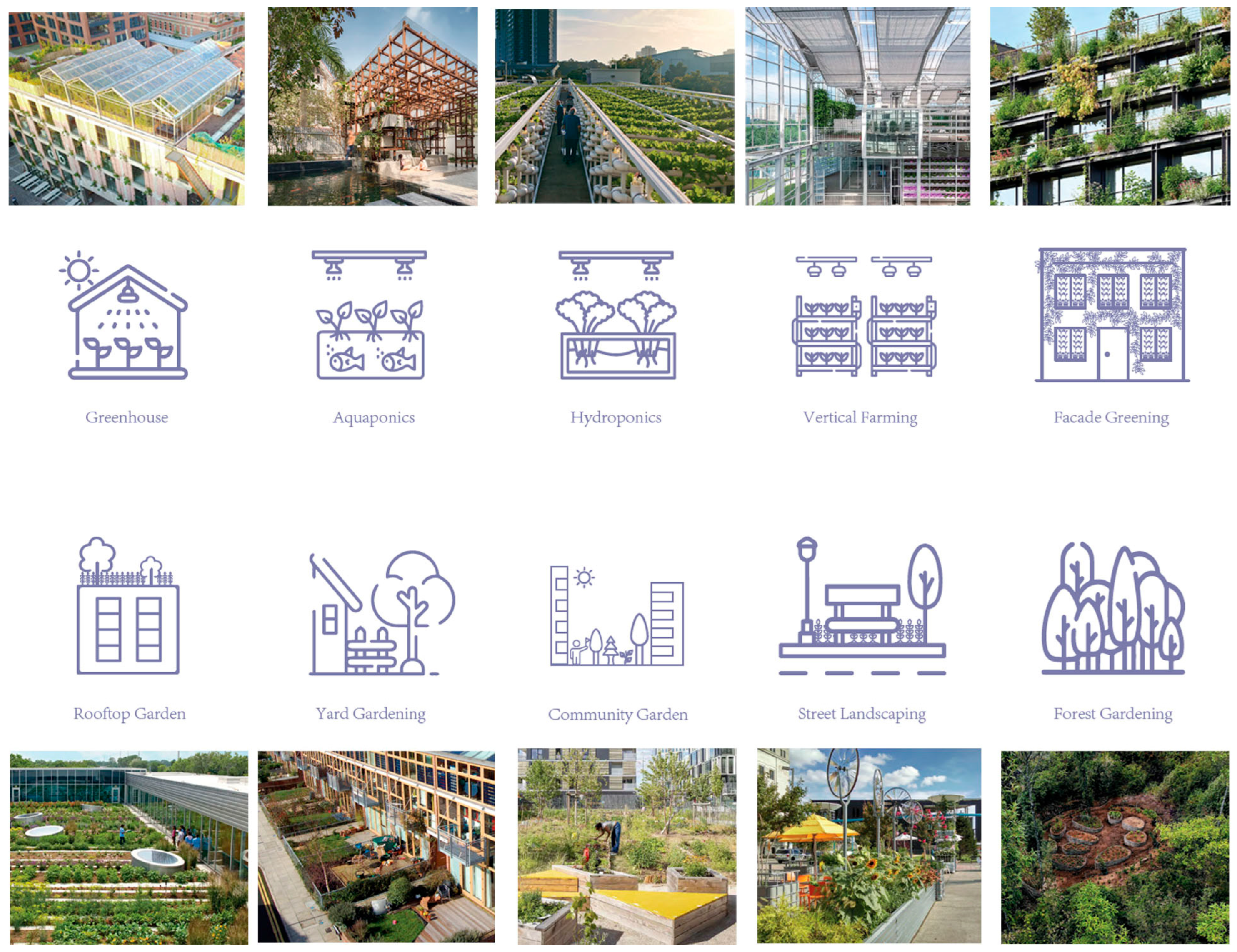

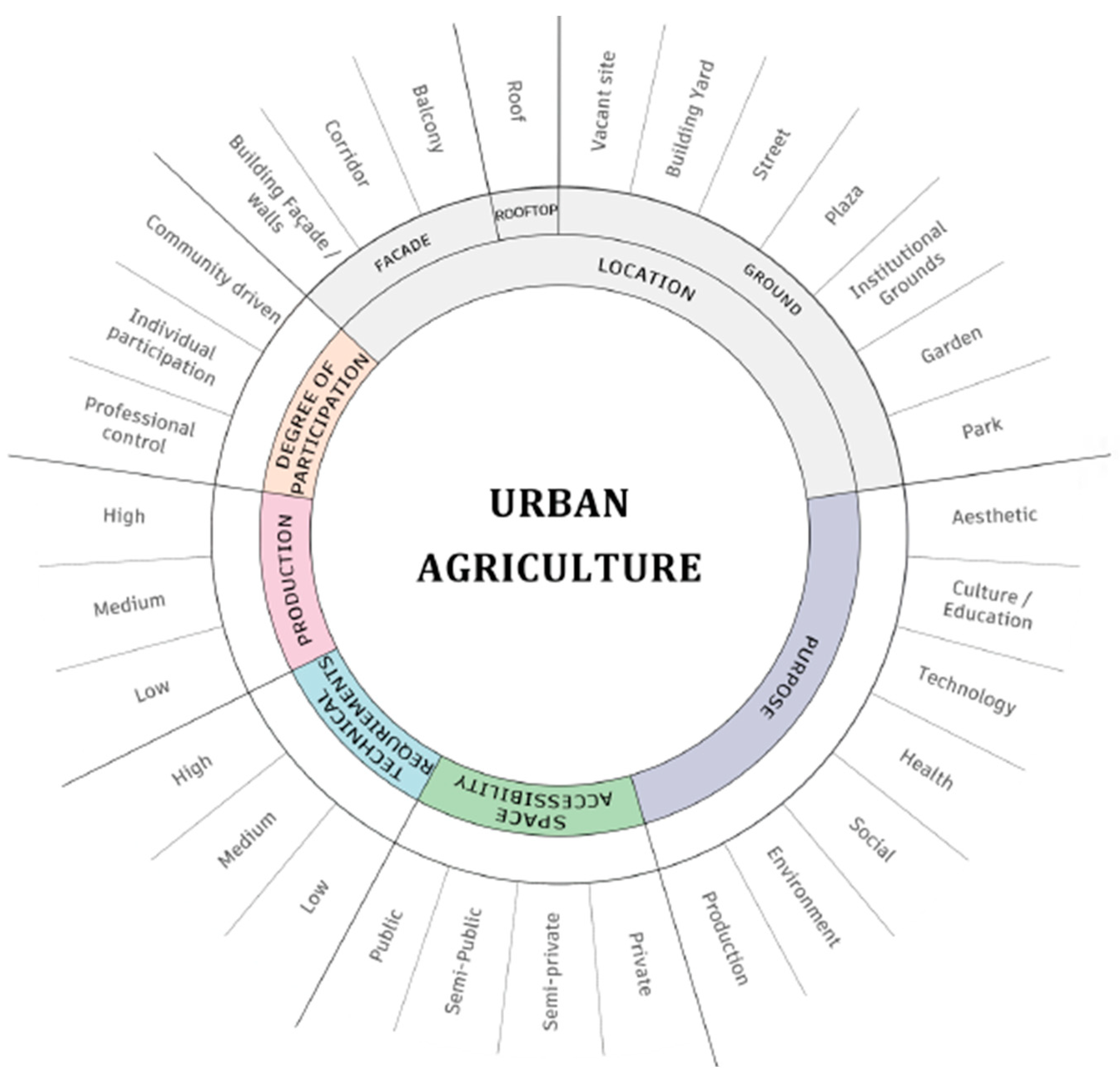

A survey based on an international literature review on the benefits and drawbacks of UA was developed to analyze its perception and driving factors in Italy and Singapore (

Section 2). The questionnaire includes an introductory section that provides definitions, descriptions, and illustrative examples of UA practices (e.g., community gardens, rooftop farming, aquaponics, hydroponics, and vertical farming). This section aimed to provide respondents with a clear and consistent understanding of the topic under investigation. Participants were also informed in the introductory part about the purpose of the research, the voluntary nature of participation, the anonymity of responses, and the intended use of the data for academic purposes. Then, 18 multiple-choice questions were developed and organized into five thematic sections:

Part 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Part 2: Knowledge and experience on UA.

Part 3: Roles, concerns, and challenges of UA in the city.

Part 4: Perception of UA.

Part 5: Ecology and sustainability-related questions.

Part 1 aims to profile the respondents by collecting socio-demographic information to identify potential correlations between perceptions of UA and socio-demographic characteristics. Part 2 assesses the respondents’ level of knowledge and direct experience with various forms of UA, sustainable farming practices, and community gardening. Part 3 analyses perceived roles, concerns, and challenges of UA in urban development. Part 4 investigates UA perception in relation to local food security, environmental sustainability, and community cohesion. Part 5 addresses its ecological and sustainability dimensions, exploring its perceived benefits in terms of ecosystem services, and, in particular, waste reduction, heat island mitigation, green infrastructure, climate resilience, community education and awareness. The questionnaire is described in detail below (

Table 1).

The questionnaire was prepared in both Italian and English to be administered, respectively, in the Italian and Singaporean contexts. In both cases, a pilot version of the questionnaire was tested by a small group of interdisciplinary respondents composed of experts in architecture, landscape design, urban planning, social development, and international policy, as well as non-expert participants (e.g., citizens, students). The purpose of the pilot phase was to assess the clarity, comprehensibility, relevance, fluidity, reliability, and overall validity of the questions. Feedback from the participants helped the refinement of both the questions and the response options to minimize the risk of participant disengagement. Important suggestions were received, particularly concerning the inclusion of images and definitions. Ethical considerations regarding data privacy and respondent confidentiality were also incorporated into the final version of the questionnaire. Anonymity was ensured during questionnaire completion to encourage honest self-reporting. No personal identifiers were collected, and all responses were processed in aggregate form. The study was conducted under IRB approval number RECAS-0471. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to completing the survey. It was deemed appropriate given the non-interventional nature of the study, the absence of sensitive or identifiable personal data, and the online format of the questionnaire, which did not involve direct contact with researchers.

5.2. Survey Implementation

The final version of the survey was implemented using the Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI) method in both Italy and Singapore to ensure consistency in data collection and processing across the two contexts [

38]. This approach involved the deployment of the questionnaire on a web-based platform that allowed for respondents to complete it electronically via computer or mobile devices. The choice of the CAWI method was informed by the high levels of digital literacy and internet accessibility observed across all age groups in both countries, which rendered web-based self-completion both feasible and appropriate. Indeed, CAWI offered advantages of cost-effectiveness, environmental sustainability (e.g., eliminating the need for printed materials), and the ability to reach a broad and diverse audience. Furthermore, it enabled dynamic content with images, multimedia elements, and real-time monitoring that facilitated efficient tracking of survey progress and response rates. For the respondents, it also provided anonymity, time, and location flexibility [

39]. Alternative methodologies, such as Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) and Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI), were excluded due to the presence of the interviewer. CAPI involves face-to-face or digitally mediated interviews, while CATI relies on telephone-based interviews to ask questions and record responses. Both methods would have compromised respondent privacy and potentially introduced bias due to the direct interpersonal interaction. In contrast, CAWI ensured respondent autonomy and minimized social desirability effects, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the collected data [

38].

5.3. Survey Distribution

Google Forms was selected as the survey platform due to its user-friendly and intuitive interface, real-time response tracking, collaborative editing capabilities, and seamless integration with data analysis tools. To safeguard respondent privacy (and comply with European GDPR regulations in Italy), the IP address tracking feature was disabled. Also, explicit informed consent was obtained from all participants before survey submission. The survey was distributed from January 2024 to June 2025 in both countries. Given the diversity in internet usage habits among the target populations, a multi-channel dissemination strategy was adopted to maximize outreach. This includes

Distribution via social media platforms (Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter).

Direct communication through email and WhatsApp to local people.

Engagement with relevant professional networks, associations, and organizations to reach respondents with domain-specific expertise on UA.

Informal mouth-to-mouth (word-of-mouth) sharing within community groups, academic circles, and personal networks to further enhance participation and inclusivity.

Participants were also encouraged to circulate the questionnaire within their personal and professional networks, thus amplifying its reach. All channels directed participants to the same Google Form link, which hosted the questionnaire. Due to the overlapping and repeated use of these channels, it was not possible to trace the number of responses attributable to each specific source. No metadata was collected regarding the access point, as the survey was designed to focus exclusively on the content of responses and the perception of UA, irrespective of the distribution path.

5.4. Survey Data Analysis

The platform required respondents to complete all questions, which resulted in the exclusion of any incomplete submissions. In total, 167 Italian and 178 Singaporean respondents completed the survey. The collected responses were exported in CSV format and subsequently processed using Microsoft Excel. Data cleaning was conducted to ensure consistency and accuracy across all entries, included the verification of response completeness, removal of duplicates, and correction of typographical errors (e.g., Italia-Italy, wrong translation). To ensure analytical robustness, the dataset was then subjected to descriptive statistical analyses aimed at identifying the patterns, trends, and response distributions across the two countries. These analyses comprised frequency counts, percentage distributions, and cross-tabulations between socio-demographic variables and other survey items to explore potential correlations. Basic charting tools were used to visualize the data and support comparative interpretation. This preliminary phase of analysis provided a foundational overview of the dataset and informed subsequent interpretative steps, including the identification of recurring perceptions, contrasts between national contexts, and the emergence of thematic clusters relevant to urban agriculture discourse.

5.5. Survey Results

The results are categorized in the same structure of the questionnaire into the following:

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Knowledge and experience in urban agriculture.

Benefits, concerns, and challenges of urban agriculture.

Perception of urban agriculture.

Ecology and sustainability-related questions.

5.5.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

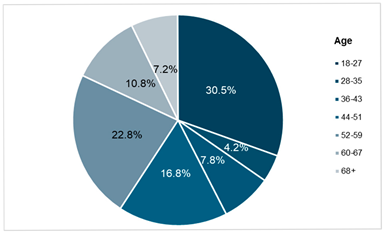

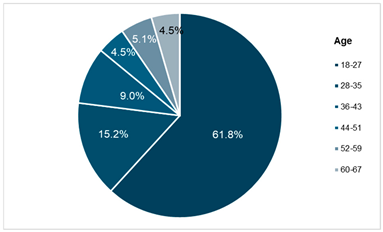

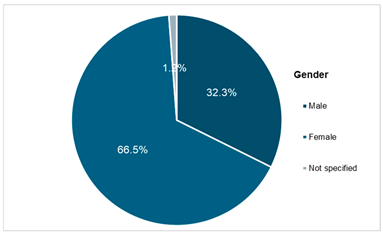

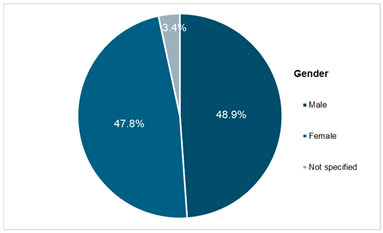

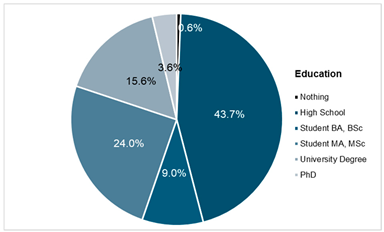

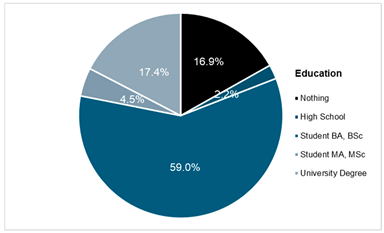

The demographic profile of the respondents reflected a heterogeneous group: (i) age groups and place of residence were well distributed, ensuring a balanced representation across different segments; (ii) the sample was predominantly female; (iii) the majority of participants held either a high school diploma or were currently enrolled in university programs; and (iv) most respondents were employed at the time of the survey (

Table 2).

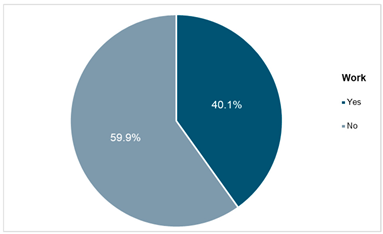

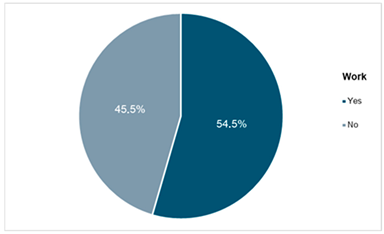

In particular, the Italian sample appeared to be somewhat more heterogeneous compared to that of Singapore, where more than 60% of respondents (equally distributed between male and female) were under 28 years of age. Concerning their education level, a notable portion of the Singaporean sample reported having no formal educational qualifications (16,9%), while 59% held a bachelor’s degree. Finally, just over half of the respondents (54.5%) were regularly employed, whereas 45.5% reported being unemployed.

5.5.2. Knowledge and Experience in Urban Agriculture

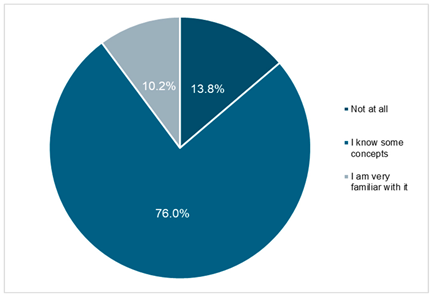

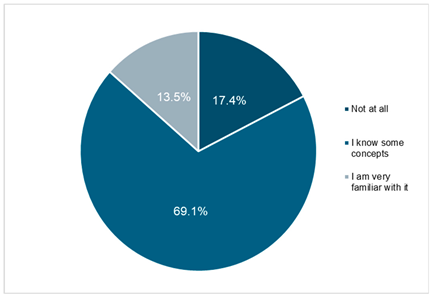

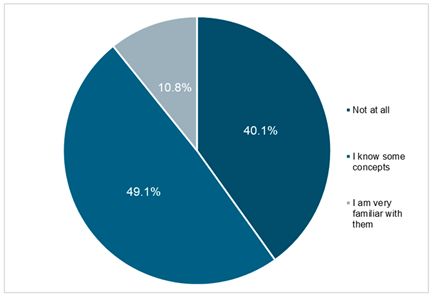

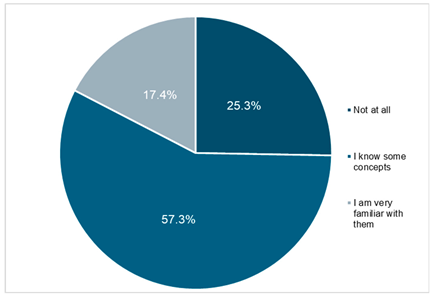

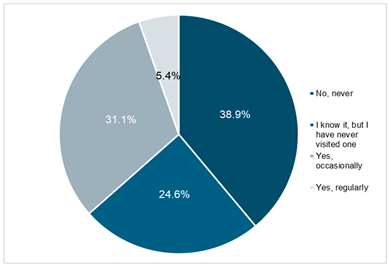

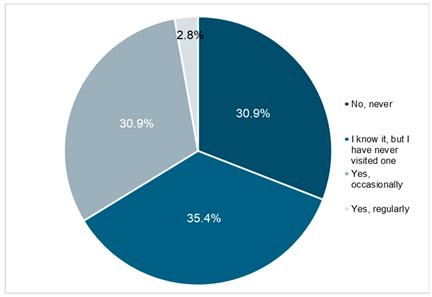

Table 3 presents the frequency of the distribution of knowledge about UA and sustainable farming methods, as well as the visits to community gardens. In Italy, the survey results indicate a medium level of general awareness regarding UA, with 76% of respondents reporting familiarity with some concepts. A smaller proportion (10.2%) indicated a high degree of familiarity, while 13% stated they were entirely unfamiliar with the topic. Thus, while UA is widely recognized, in-depth knowledge remains limited. The results from Singapore present similar percentages: 69.1% know something about UA, 17.4% have moderate knowledge about it, while 13.5% of people interviewed are quite familiar with this agricultural practice. In contrast, awareness of sustainable farming methods in Italy appears significantly lower. In total, 40.1% of respondents reported no knowledge of these techniques, and only 10.8% considered themselves familiar. The majority (49.1%) indicated a partial understanding. Thus, there is a considerable knowledge gap regarding innovative and technologically integrated farming practices. On the contrary, in Singapore, there are 25% of people do not know UA methods, while 57% of people declare to know something about it. In total, 17.4% of the people are familiar with the different farming methods. This means that 1/4 of people do not have any knowledge, while 2/3 have some or a lot of familiarity with farming methods. Regarding direct engagement with the community garden, the Italian responses reveal limited experiential familiarity. In total, 38.9% stated they had never heard of or visited any UA initiative, while 26.4% of participants reported being aware of such spaces without having ever visited. Occasional visits were reported by 31.1%, whereas only 5.4% indicated regular visits. In Singapore, 30.9% of people never visited a place dedicated to UA, and 35.4%, although they know something, have never visited a place dedicated to UA. In total, 30.9% occasionally visited an urban farm, and very few people, 2.8%, are involved and visit them regularly. This gap between conceptual knowledge and practical experience points to the potential benefit of increasing the visibility and accessibility of UA projects to foster deeper public engagement and support. This limited awareness represents a critical barrier to public understanding and acceptance. The results underscore the necessity of educational campaigns and demonstration projects to make these approaches more visible, comprehensible, and culturally embedded.

5.5.3. Benefits, Concerns, and Challenges of Urban Agriculture

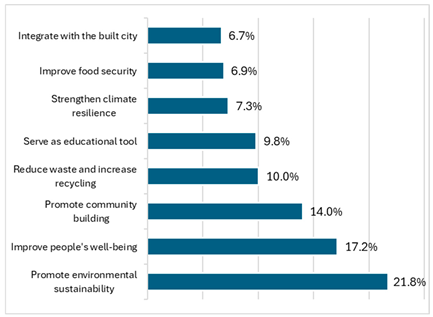

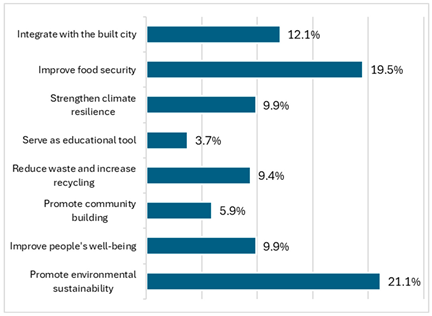

Table 4 shows environmental sustainability considerations on UA. Environmental sustainability of UA is considered the most relevant benefit both in Italy (21.8%) and Singapore (21.1%). In addition, in Italy, improvements in individual quality of life (17.2%) and the promotion of community building and social cohesion (14.0%) are frequently acknowledged. These strong associations may indicate a reductive understanding of UA’s multifunctionality, potentially framing it in terms of individual or social experiences rather than in relation to broader urban transformations. Educational and ecological functions were acknowledged to a lesser extent in the components of waste reduction and recycling implementation (10%), environmental education (9.8%), climate resilience (7.3%), and food security improvement (6.9%). The limited recognition of UA’s potential for integration with the built environment (6.7%) highlights a general lack of awareness regarding the architecture-integrated technologies that offer significant design opportunities and spatial synergies. The Singaporean interviews report other priority scales: food security (19.50%), integration into the built environment (12.1%), climate resilience improvement and people’s well-being (9.9%), and reuse and recycling (9,4%). Community building is important for 5.9%, and the educational tool is considered the main aspect by only for 3.7% of the population. Italian results suggest that, while environmental and social benefits of UA are broadly recognized, more strategic communication may be necessary to enhance awareness of its potential contributions to systemic urban challenges, such as climate adaptation, food system resilience, and spatial integration. In contrast, the Singaporean survey reveals that environment concerns and food security are prioritized equally, followed by the building integration, climate action, and overall well-being. Aspects related to community building are considered to be less important.

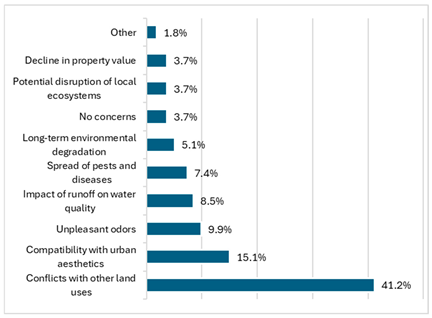

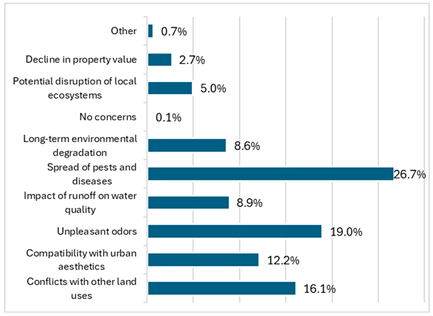

Concerns on UA differ significantly between Italy and Singapore. In Italy, the predominant concern is its potential conflict with other land uses (41.2%). This suggests a limited perception of UA’s spatial adaptability and its capacity to coexist synergistically with other urban functions. Otherwise, UA is considered a competing rather than an integrative strategy within the urban fabric. The issue of compatibility with urban esthetics (15.1%) further reinforces the perception of UA as visually or functionally misaligned with the formal qualities of contemporary cities. Such concerns may indicate the persistence of a traditional urban design paradigm in which productive landscapes are not recognized as integral components of green infrastructure. Additional concerns include unpleasant odors (9.9%), water quality impacts due to runoff (8.5%), and the spread of pests and diseases (7.4%), highlighting doubts about environmental hygiene and ecological management. Other issues include long-term environmental degradation (5.1%), potential ecosystem disruption (3.7%), and property devaluation (3.7%). Finally, only 3.7% of respondents reported no concerns, indicating that although UA is generally viewed positively, ambiguities and skepticism remain prevalent. In contrast, despite Singapore’s spatial constraints, land use conflicts are not the primary concern. Only 16.1% of respondents identified this issue as the most relevant. Instead, greater concern was expressed regarding the potential presence of pesticides (27.6%) and unpleasant odors (19%). Regarding the built environment, 12% of respondents believe UA could reduce the esthetic value of buildings, while 2.7% fear it may negatively affect property values. Environmental concerns also emerged: 8.6% perceive a risk of long-term environmental degradation, and 5% are concerned about potential damage to existing ecosystems. It is noteworthy that virtually no respondents considered UA to be entirely free of negative aspects.

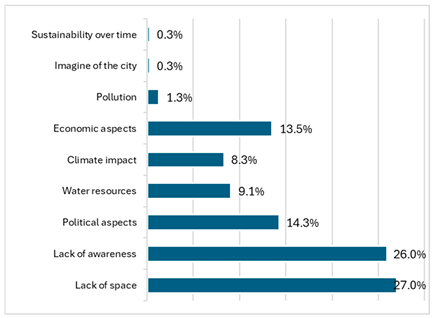

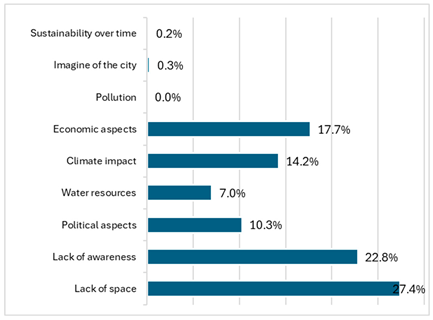

The most pressing challenges identified in both Italy and Singapore relate to the lack of space (Italy: 27.0%; Singapore: 27.4%) and limited public awareness (Italy: 26.0%; Singapore: 22.8%). These results highlight two interrelated barriers. First, the tangible spatial constraints associated with urban density and competing land uses reinforce the perception that UA requires dedicated space, rather than being conceived as an integrative layer within existing built environments. This reveals a limited recognition of spatial innovation in UA (e.g., vertical gardens, rooftop greenhouses, façade integrated solutions). Second, this further confirms the persistence of knowledge gaps on visibility, understanding, and cultural legitimization of UA within urban systems. Political (Italy: 14.3%; Singapore: 10.3%) and economic factors (Italy: 13.5%; Singapore: 17.7%) are acknowledged as relevant but not dominant barriers. This may indicate that UA is not yet fully embedded within urban governance agendas or that existing policy instruments lack sufficient support mechanisms. Environmental concerns, such as climate impact (Italy: 8.3%; Singapore: 14.2%), water resource management (Italy: 9.1%; Singapore: 7.0%), and pollution (Italy: 1.3%), are present, but relatively marginal. This may indicate that respondents do not perceive UA as a significant environmental risk, but rather as a practice whose feasibility and social legitimacy remain under scrutiny. Lastly, the near absence of responses for “sustainability over time” (Italy: 0,3%; Singapore 0,2%) and “image of the city” (0.3% each) is striking. Other concerns are not considered significant.

In essence, UA’s benefits are broadly recognized in both Italy and Singapore for its potential contributions to sustainability. In Italy, it is primarily valued for its environmental and social dimensions, which reflect a vision of UA as a regenerative and community-oriented practice, capable of reconnecting fragmented urban spaces and fostering civic engagement. In Singapore, the benefits are framed more technically: UA is appreciated for its contribution to food security and environmental efficiency, aligning with national priorities in a land-scarce and resource-conscious setting. Social and esthetic dimensions are less acknowledged than in the Italian context. This divergence suggests that UA is interpreted through different urban imaginaries: as a socio-ecological strategy in Italy, and as a functional component of urban resilience in Singapore. Concerns about UA also differ significantly between the two territories. In Italy, perceived barriers are rooted in perception and design culture. Its integration is hindered by traditional conceptions of urban space, where productive landscapes are seen as incompatible with formal esthetics and existing land uses, and could represent competitive land use for citizens and potential builders or stakeholders. This skepticism reflects cultural inertia and spatial rigidity, which limit experimentation and innovation. In Singapore, the concerns, by contrast, focus on technical risks, such as pesticide use and odor management. Despite Singapore’s extreme spatial constraints, land use conflicts are less emphasized, suggesting a centralized and strategic planning approach that accommodates UA within broader sustainability goals. Both contexts share a lack of awareness and limited recognition of UA’s integrative potential. However, while Italy struggles with cultural legitimization and esthetic acceptance, Singapore’s challenges are operational and policy-driven, such as gaps in implementation, regulation, and public engagement. Thus, Italy may require a cultural and design paradigm shift to embrace UA as part of a multifunctional urban landscape, while Singapore may benefit from refining its governance mechanisms and enhancing participatory frameworks to ensure that UA is not only technically feasible, but also socially embedded.

5.5.4. Perceptions of Urban Agriculture

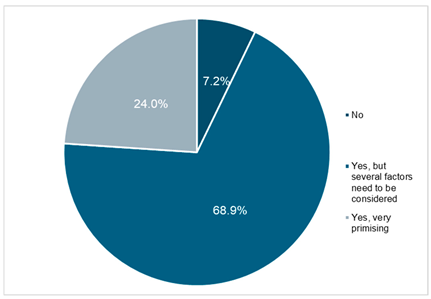

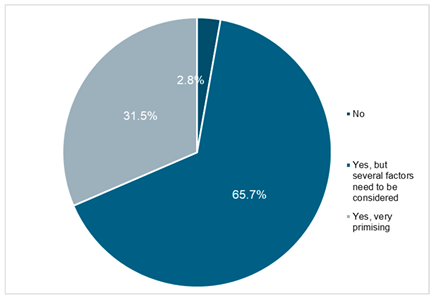

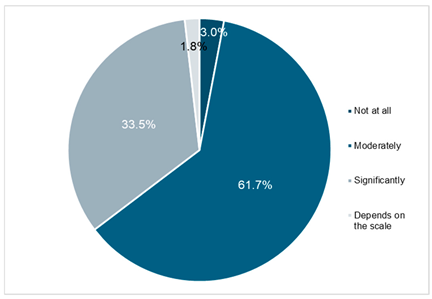

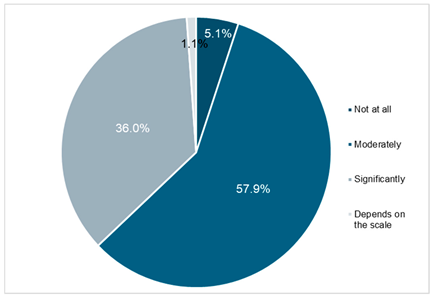

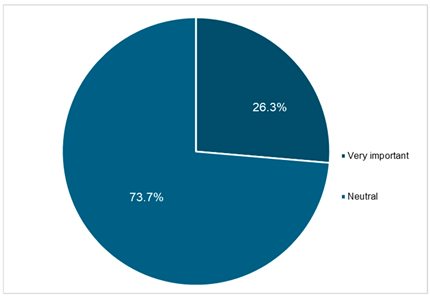

Table 5 shows the perceptions of UA. In Italy, regarding UA’s contribution to local food security, a large majority (68.9%) acknowledges its potential, albeit conditioned to the consideration of multiple factors (e.g., scale, logistics, market access, or production capacity). A smaller share (24.0%) expresses strong confidence in UA’s promise, while 7.2% rejects this possibility. This distribution highlights a partial but growing recognition of the complexities involved in integrating UA within broader food systems. Only 2.8% of Singaporean interviewees are not convinced about the role of UA for food security, while a similar percentage to Italians, 65.7%, consider a valid strategy, but only if it is adjusted. In total, 31.5% support the UA. Even if in some cases the percentages are similar, it is evident that, for Singapore, food security is a critical aspect that must be alleviated by considering the implementation of the UA in a more consistent way. In addition, a significant majority of respondents (61.7%) perceive UA as moderately contributing to environmental sustainability, while 33.5% consider its contribution as significant. Only a marginal share (3.0%) denies any contribution, and an even smaller proportion (1.8%) views it as scale-dependent. The “

moderate” perception may indicate that respondents associate UA with general ecological benefits (e.g., green coverage, biodiversity, or reduced transport emissions) without a precise awareness of its potential systemic impact. These results are consistent with Singaporean responses, with 5.1% of people being convinced that no benefit will be derived in terms of environmental sustainability, while almost 94% are convinced that UA can improve the urban environment. Among them, 57.9% are moderately convinced, and 36% completely agree with this sentence. The role of UA as green infrastructure is also not fully recognized. In total, 26.3% of participants consider this role “

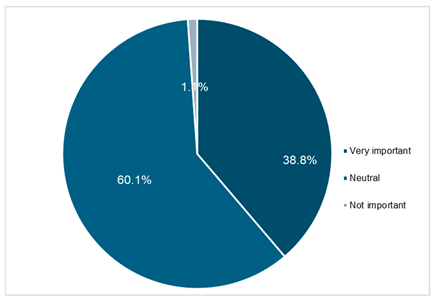

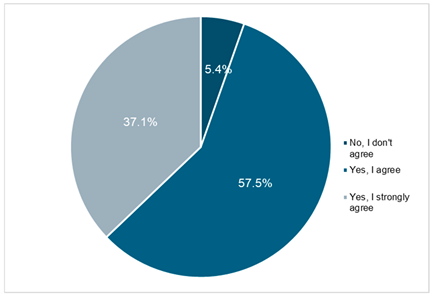

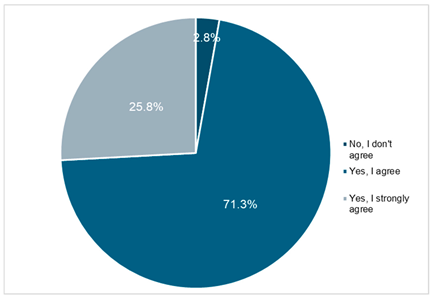

very important”, while the majority (73.7%) selected a neutral stance. From the Singaporean side, 38% consider the UA to be a very important strategy for improving green infrastructure, and the majority, 60.1%, are neutral. In both situations, this may indicate either uncertainty or a limited familiarity with the terminology and functions associated with green infrastructure (e.g., stormwater management, ecological connectivity, and air quality improvement). This finding highlights the need for clearer framing of UA not merely as an isolated practice, but as a systemic component of resilient urban landscapes. Finally, UA’s social dimension appears to be more firmly established in respondents’ perceptions: 57.5% agree and 37.1% strongly agree that UA enhances community connections. Only a small minority (5.4%) express disagreement. This strong consensus reflects a common view of UA as a socially embedded practice that is capable of fostering collective experiences and place-making processes. More than 97% of Singaporean interviewees are convinced about the social contribution of UA, 25.8% are strongly convinced, while 71.3% agree. Only 2.8% disagree about the social role of UA.

5.5.5. Ecology and Sustainability-Related Questions

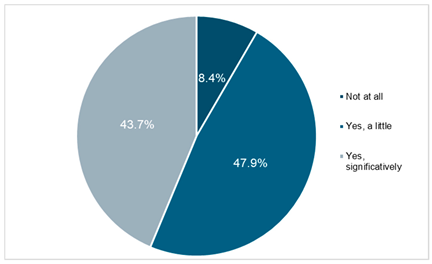

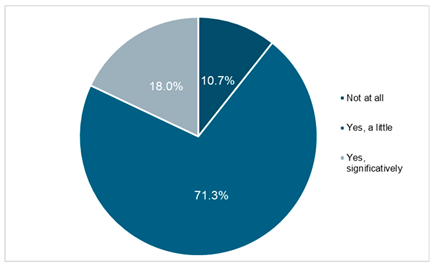

Table 6 shows ecology and sustainability perception of UA. In Italy, the ecological benefits and the role of UA in waste reduction (e.g., food, organic, wastewater) are moderately recognized. While a combined 91.6% of respondents acknowledged this benefit, in a moderate (47.9%) or significant (43.7%) way, only a minority (8.4%) explicitly denied such contributions. Thus, the ability of UA to close resource loops, enhance nutrient cycling and reduce municipal waste through composting and greywater reuse are not fully appreciated. In Singapore, 10.7% of interviewees state that no ecological benefit can come from the UA; 90% are convinced that it has some benefits. In total, 71.8% think that it has little benefit and 18% completely agree. Both in Italy and Singapore, the findings therefore suggest a critical need for targeted educational efforts and demonstrative pilot projects that concretely illustrate UA’s role in circular economy strategies. In Singapore, particularly the main percentage, 71.3%, have to be convinced that the contribution is higher than they claim to think.

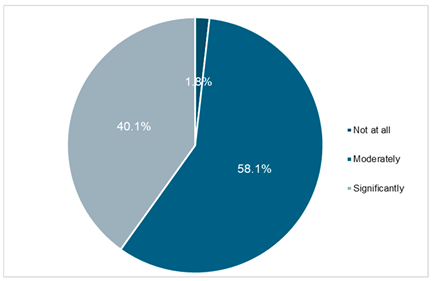

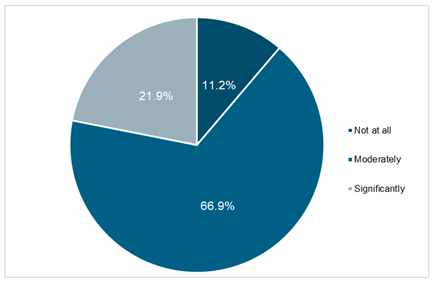

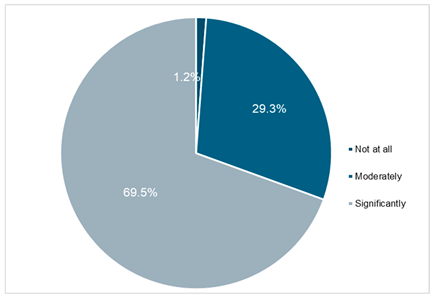

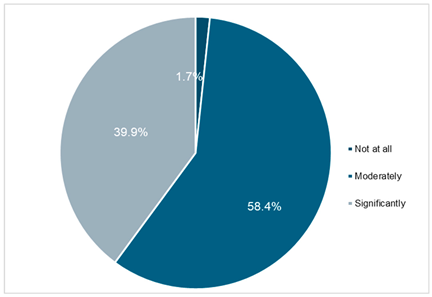

Regarding UA’s role in mitigating the urban heat island (UHI) effect, most respondents (58.1%) acknowledged a moderate contribution, and 40.1% considered it significant. Only 1.8% dismissed the idea altogether. In Singapore, compared to Italian questionnaires, there is a 11.2% who disagree about the role of UA to reduce the UHI, but more people, 66.9%, recognize a positive contribution to reduce the UA, and 21.9% consider it very significant. In total, 2/3 of interviewed participants in Italy agreed, even if they were not so convinced. These findings suggest that, while UA is positively viewed, its bioclimatic potential is not yet fully considered by the public. Also, it indicates a relatively well-established perception of UA as part of the climate mitigation strategy. However, the predominance of “moderate” rather than “significant” responses may reflect an incomplete understanding of the mechanisms involved, such as evapotranspiration, albedo modification, and localized shading. UA is widely perceived to have strong (69.5%) or moderate (29.3%) educational value. Only 1.2% see no role at all. We found a similar percentage of people who do not recognize the educational role of the UA in Singapore (1.7%) and a similar percentage of people who recognize a role in terms of educational activity. Unlike in Italy, in Singapore, 39.9% consider it a very significant contribution, while 58.4% recognize a moderate contribution. Thus, respondents recognize this role, even when lacking detailed technical or direct knowledge. This broad consensus aligns with the literature identifying UA as a hands-on pedagogical platform that facilitates environmental literacy and reconnects urban dwellers with ecological processes.

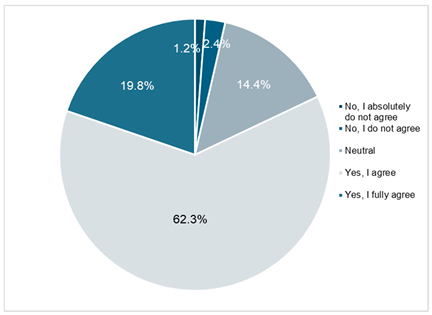

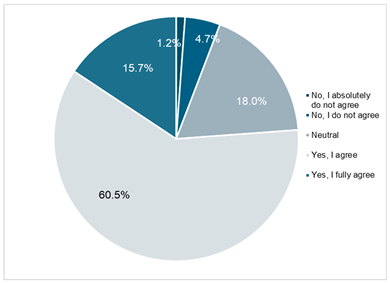

In Italy, most respondents (62.3%) agreed that UA contributes to enhancing the city’s resilience to climate change impacts, and an additional 19.8% expressed full agreement. In contrast, only 3.6% disagreed to any extent, and 14.4% remained neutral. These results reflect a generally favorable perception of UA’s capacity to support climate resilience, particularly in terms of food system decentralization, microclimate regulation, stormwater management, and social cohesion. These findings point to the need for more explicit communication and evidence-based narratives that pose UA as a functional component of climate mitigation and adaptation strategies. In Singapore, 5.9% of people do not recognize any role for improving the resilience to the UA, while 60.5% of people moderately agree. The remaining 15.7% are completely convinced about the role of the UA to improve resilience to the adaptation to climate change.

6. Discussion of the Results

As highlighted in the literature review [

40], the city—set to host nearly two-thirds of the world’s population within the next few decades (expected to be 66.6% by the year 2050)—will increasingly become the central arena not only for energy and water production, but also for food cultivation. A significant share of the urban population will therefore need to engage with one or more forms of UA, although, at present, most have not yet had the opportunity to experience this practice directly.

As mentioned in

Section 1, results from this survey are different from other previous similar studies. It should be noted that, based on previous research, as reported by Grebitus [

21], direct survey questions can introduce social desirability bias, whereby participants respond in ways they believe will be viewed favorably by the interviewer, even though previous research indicates that online surveys tend to reduce this bias. Therefore, given the use of an online survey, it is possible that social desirability bias was minimized.

6.1. Italian Context

In the Italian context, the integration of UA into the built environment is strongly conditioned by the perception of heritage values. Italian cities are widely regarded as “open-air museums” where the visual integrity of historic centers and landscapes constitutes a central element of collective identity. This cultural framing generates esthetic concerns regarding UA, as interventions such as rooftop gardens, vertical farms, or peri-urban cultivation are often perceived as potentially disruptive to the harmony of historic skylines, piazzas, and monumental ensembles. The emphasis on esthetics is deeply embedded in a cultural system in which the preservation of tangible heritage is prioritized over functional innovation. Consequently, public debates on UA frequently intersect with broader land use conflicts and esthetic issues, where agricultural practices must negotiate space with conservation imperatives and urban development pressures. This reflects the country’s contested urban landscapes, where agricultural land, heritage, and new development are constantly negotiating legitimacy. Consequently, UA is primarily perceived as a social and cultural practice: it fosters community cohesion and intergenerational exchange, promotes health and well-being through direct contact with nature, and reinforces cultural identity by connecting food, tradition, and place. It provides inclusive spaces where residents from diverse backgrounds can collaborate, share gardening knowledge, and strengthen neighborhood identity. Such practices foster intergenerational learning and cultural preservation, where traditional foodways and ecological literacy are passed down through shared urban farming activities. The positive social perception of UA includes its role in revaluing urban areas, increasing access to fresh food, and offering recreational and educational opportunities that enhance quality of life. Italian communities particularly appreciate UA as a multifunctional practice that supports social bonds and collective care. Thus, in Italy, the challenge is not simply to expand UA for sustainability or food security, but to design and communicate it as an esthetically and culturally compatible practice that aligns with the nation’s heritage-driven urban identity.

According to this, Italian UA policy emphasizes mediating these conflicts through legal and regulatory frameworks that balance agricultural production with infrastructure development and cultural protection. Expanding public engagement through education and visibility campaigns is a priority to transform UA into a recognized civic infrastructure. Policies advocate for multifunctional urban spaces that combine agriculture with other social and recreational activities to attract diverse participation. While direct architectural integration of UA is less advanced than in Singapore, there is growing recognition of its potential to contribute to social cohesion and quality of life. Italian policies thus seek to strengthen links between UA and broader environmental objectives, including waste reduction and climate mitigation. Italian policies should strength the link between UA and environmental policy to:

Mediate land use conflicts by creating legal and regulatory frameworks that balance heritage protection, development pressures, and productive landscapes.

Expand public engagement through education and visibility campaigns that transform UA into a civic infrastructure.

Promote multifunctional public spaces that integrate cultivation with cultural, educational, and recreational activities to attract wider participation.

6.2. Singaporean Context

Singapore’s extreme residential density and limited arable land fundamentally condition how UA is perceived and practiced. With one of the highest residential densities in the world and virtually no arable land, agricultural activities inevitably occur in close proximity to residential areas and workplaces. Concerns about pesticide dispersion and unpleasant odors, frequently reported by respondents, are directly linked to this spatial arrangement. At the same time, Singapore’s dependence on food imports creates a collective awareness of vulnerability. This condition elevates UA from a community practice to a pillar of national strategy: UA is embedded within a strong national agenda aimed at achieving 30% food self-sufficiency by 2030 (“30-by-30” target). The government actively promotes UA integration into the urban fabric through policies encouraging rooftop gardens, vertical farms, and community gardening, especially in Housing and Development Board (HDB) estates where 80% of the population lives. Key initiatives include the Singapore Green Plan 2030, which fosters urban greenery integration via regulations like the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s Landscape Replacement Act, supporting the inclusion of urban farms in building designs. Public agencies such as NParks incentivize home-grown produce through seed distribution and awareness campaigns. Community-oriented UA models are emphasized, alongside technological innovations (hydroponics, aquaponics) to overcome land scarcity. Financial grants through schemes like the SG Eco-Fund empower community-led food production and education, thereby broadening UA participation beyond purely state-led efforts. Thus, vertical farms, hydroponics, and controlled-environment agriculture are celebrated not only as solutions to scarcity, but also as symbols of the city-state’s capacity to turn constraint into opportunity. Singaporean policies should:

Consolidate UA’s role in the national food security agenda to ensure that ecological services (e.g., heat mitigation, biodiversity, climate resilience) are equally valued.

Address public concerns about pesticide use and odors by promoting transparent standards, certifications, and technological innovations.

Broaden participation beyond state-led initiatives to foster community-based projects that enhance inclusivity and strengthen UA’s social legitimacy.

Invest in public education to improve cultural and ecological practices that can transform urban lifestyles.

6.3. Integrated Analysis

In general, UA emerges as a practice with considerable potential to transform urban environments into more nature-positive and climate-resilient systems, simultaneously delivering a wide spectrum of social and environmental benefits to local communities. In both countries, familiarity with UA is relatively widespread, but there is a gap between general awareness and direct engagement. Many respondents are familiar with the concept of UA, but only a fraction report on an in-depth knowledge or direct experience. In Italy, approximately 76% of respondents, and 69.1% in Singapore, are familiar with the concept of UA; however, only 30.1% and 38.9%, respectively, have visited a community garden. This discrepancy can be linked to the accessibility of places that adopt UA, which can be physically distant, not easy to reach, or not present in specific cities or parts of the city. Thus, accessibility, location, and visibility become as decisive as cultural attitudes in shaping public participation. To bridge this gap, targeted educational campaigns and participatory programs are needed to foster deeper involvement and transform awareness into active engagement.

Across both contexts, participants acknowledged the role of UA in fostering sustainable urban development. In general, UA is primarily perceived as a strategy that can enhance environmental sustainability. Italy demonstrates stronger confidence in UA’s potential to reduce waste and mitigate systemic impacts, while Singapore shows greater caution, often perceiving benefits as more limited. In relation to the urban heat island effect, Italy tends to view UA as moderately effective, whereas Singapore displays more skepticism, although the majority still acknowledge some positive impact. This suggests that UA’s infrastructural potential as green and climate-responsive urban fabric remains underexplored, overshadowed by social narratives in Italy and food-security imperatives in Singapore.

In addition, it is particularly insightful to examine the second most frequently cited benefit: in Italy, this concerns social aspects, community building, and health, while in Singapore it is more closely associated with food production. Educational and resilience functions, instead, are generally perceived as secondary in both settings. Italy tends to acknowledge the environmental and systemic benefits of UA with greater conviction, while Singapore adopts a more cautious stance, albeit maintaining an overall favorable outlook. Enhancing awareness of the multiple functions of UA requires, on the one hand, increasing opportunities for public engagement and experiential learning, and, on the other hand, developing targeted policies that promote UA by identifying, within each specific context, the elements most likely to attract potential urban farmers, users, or advocates. These actors, by recognizing the numerous benefits of UA, may also help to mitigate perceptions of conflict or competition with other forms of urban development.

Shared UA experiences represent a valuable means of expanding collective knowledge and facilitating the transfer of expertise to new practitioners and users. Furthermore, public events and initiatives could offer educational programs on nutrition and gardening for different age groups, thereby reinforcing the social and educational dimensions of UA.

Italian respondents expressed concerns that the proliferation of ground-based gardens could have negative implications for land consumption, potentially competing with other land uses such as infrastructure or new construction, and affecting visual perception and esthetics. In Singapore, where architectural integration practices are more common and help limit land occupation, the main concerns instead relate to the potential dispersion of pesticides in the air and the emission of unpleasant odors. This finding contrasts with evidence from the similar mentioned studies, which suggest that urban residents may prefer UA due to its local (“zero-kilometer”) production and because crops are cultivated by citizens primarily motivated by health, well-being, and sense of community, and are thereby perceived as healthier and potentially organic.

Italian respondents also identified several challenges, including limited space availability, low awareness, and a general lack of knowledge regarding national and local food policies. Similarly, in Singapore, respondents highlighted the scarcity of space and limited understanding of the topic as key barriers to UA expansion.

6.4. Practical Implications

The findings of this study carry several practical implications for the development and governance of UA. First, several strategies can be outlined to reduce the perception of negatives. It is crucial to promote a wider understanding and experimentation with the diverse forms of urban farming, while also encouraging the architectural integration of UA into the envelopes of public and private and residential and commercial buildings. Such integration could help mitigate negative perceptions and reinforce the role of UA as a multifunctional component of sustainable urban ecosystems. Thus, even in the absence of deep knowledge or direct experience, UA is projected as a moral and pedagogical practice, a collective good that binds individuals together around shared values of care, sustainability, and resilience.

In this context, design and integration are important keys for social acceptance. In highly sensitive contexts, embedding UA within architectural and urban design frameworks can shift its image from “intrusive” to “harmonious”. Demonstration projects that integrate farms on rooftops, courtyards, or peri-urban fringes with esthetic attention can counter the fear of degraded landscapes. In addition, communication and transparency play a decisive role. Establishing visible certification systems, quality standards, and public campaigns about practices help build trust. Also, participation and co-ownership can improve responsibility and community bonding. Finally, policy framing is decisive to embed UA in a narrative of resilience, sustainability, and social value.

7. Conclusions

This study aimed to assess the level of knowledge and public perception regarding specific aspects of UA to identify targeted actions to foster engagement and promote the dissemination of sustainable urban farming practices. The survey was conducted in two markedly different contexts, Italy and Singapore, to compare perceptions and to evaluate the perceived role of UA in enhancing the environmental, economic, and social dimensions across countries characterized by distinct climatic, geographical, and cultural conditions, as well as historical connection with urban farming. In Italy, immigrants from the southern to the northern regions, who left their farming lands to work in the industries, tried to cultivate inside the cities as a way to keep their tradition and to enrich their poor diet. Singapore experienced urban farming as a cash crop during the British colonizing in the 19th century, even if they never solved their food security issues. In both countries, during the Second World War, farming occupied public spaces as well as private yards. Those asymmetries present comparison opportunities, as Italy, with its regional fragmentation, and Singapore, as a centralized city-state, embody vastly different scales of governance. In general, participants widely recognized the positive impacts of UA, including improving the cities’ environmental and social sustainability and quality.

More specifically, it was observed that, despite the diversity of the two countries, the results are partially similar, yet still differ from those emerging in other field surveys. As already discussed in the paper, this aspect may depend on how the questionnaire was developed and on the specific objectives of the survey. What emerges is that responses related to individual experiences within one’s own space of belonging are primarily associated with personal well-being and self-production of food. The further the practice moves away from the private sphere and is carried out in a public or shared environment, the more urban agriculture (UA) is perceived as an actual strategy for improving the city’s environmental conditions—both because it is considered an important ecosystem service and as a strategy for achieving multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—as well as a factor fostering social cohesion and a sense of community belonging.

In this specific case, the survey aimed to understand to what extent the broader community (not only individuals directly involved in UA practices) was willing to accept how different forms of UA could be integrated into private, semi-private, or public spaces, thereby modifying the configuration of residential buildings or shared areas. It was also intended to identify potential resistance or negative perceptions, and thus a possible lack of trust in the spread of UA. This aspect represents a fundamental element for public administrations to consider before designing policies for the dissemination of such practices to prevent design errors and to enhance user well-being and cooperation. Policies should take into account the strengths that emerge—particularly the environmental aspects, sense of community, and individual well-being—while also considering the concerns expressed: in Italy, these are more related to competition over land use, whereas in Singapore, they are more focused on food quality, where the possible use of polluting pesticides and smells could contaminate the air and thus negatively affect environmental conditions. This study inevitably presents certain limitations that do not undermine its contribution. This research is limited to two geographical locations and a specific age group (18–75 years). Thus, it is important to recognize that different contexts and communities may exhibit varied benefits and critical aspects and could guide different possibilities to engage the whole community.

Longitudinal studies could trace how changing policies, climatic conditions, and social demands reshape UA over time, while more granular, site-specific investigations would illuminate the micro-politics of land use, governance, and accessibility. Comparative studies should also extend beyond binary cases to include cities across different continents, creating a global atlas of UA’s roles within diverse urban metabolisms. Future research will develop a global mapping of UA perceptions and practices to identify typologies of governance, cultural narratives, and spatial integration.