1. Introduction

Nowadays, in numerous urban public spaces throughout China, a significant anthropological observation is the congregation of older adults sitting on benches, deeply engrossed in their smartphones. “When I scroll through these videos, even with family beside me, I don’t feel empty anymore,” says a 68-year-old woman, reflecting a central paradox of China’s digital era: those who previously valued in-person communication [

1] now pursue social connection via technologically mediated forms of distancing. This phenomenon of disregarding one’s immediate social partner in favor of mobile device engagement, termed “phubbing” in scholarly discourse [

2,

3], has spread rapidly among older Chinese adults. China currently has 310 million people aged 60 and above, accounting for 22% of the total population [

4]. By June 2025, 161 million out of them had established internet connectivity, achieving a digital penetration rate of 52% [

5].

Urban older Chinese adults show high ownership rates of technology products and positive attitudes toward information technology [

6]. The penetration of short video platforms is especially noteworthy. Over 60% of older adults use Douyin daily, spending one to two hours per session [

7], revealing a clear pattern of stratification. Recent research indicates that loneliness and problematic smartphone use predict phubbing behaviors across age groups [

8,

9]. Among older adults, intergenerational dynamics play a substantial role. Being phubbed by adult children heightens feelings of social exclusion, which subsequently drives compensatory digital engagement [

10,

11]. More critically, this usage pattern shows clear stratification. Older adults with non-agricultural household registration, higher level of education and higher income use platforms more frequently, while those with less social participation and lower social status spend longer durations [

12]. Amid COVID-19, health codes and other digital tools moved from conveniences to survival essentials. This structural pressure sped up older groups’ reliance on smart devices, with the usage pattern persisting post-pandemic [

13].

Older adults’ digital enthusiasm coexists with normative discomfort as they show lower tolerance for phubbing than younger groups and view it as a breach of social etiquette [

14,

15]. This tension amid rapid smartphone adoption suggests that their intensive use follows an under-theorized logic, especially in the context of sustainable digital aging. Digital sustainability research focuses on technological systems that boost well-being while minimizing harm [

16,

17,

18]. For aging populations, this framework asks whether digitalization supports quality of life, autonomy and social integration in later years [

19]. However, there is a disconnect between research on older adults’ tech use and sustainability concerns. WeChat groups enable their participation in community affairs [

20], yet smartphone dependence among them is both an individual psychological issue and a social problem related to digitalized living environments [

21]. This reveals a binary dilemma in existing research. Studies either frame digital inclusion as evident progress or treat excessive use as addictive behavior requiring intervention. Neither path examines whether such digitalization truly serves older adults’ long-term interests or merely shifts care responsibilities from families and the state to corporate platforms that extract value through the attention economy.

This disconnect presents a paradox. Why do Chinese older adults who uphold collectivist norms and view family obligations as moral constraints [

22] persistently engage in behaviors they deem “not quite right”? Technology acceptance models focused on instrumental utility [

23] fail to explain this behavior that violates norms. Frameworks like compensatory internet use theory [

24] that were developed for young Western populations overlook later life motivations specific to this cultural context.

The paradox persists due to core research limitations. Age bias and Western centrism dominate phubbing studies. These studies focus almost exclusively on young Western adults [

25] and pathologize the behavior as impulse control failure without acknowledging potential adaptive functions in unfulfilling co-present interactions. Research also prioritizes usage consequences such as impacts on loneliness [

26], relationships between social capital and self-rated health [

27], and associations with depression [

28,

29] over underlying mechanisms. Studies on Chinese older adults show victim bias. They focus on technology adoption barriers or instrumental uses like mobile payments [

30] rather than intensive use patterns and frame these older adults as passive phubbing victims instead of active agents. To date, there has been no comprehensive investigation into the underlying motives and mechanisms driving phubbing behavior among East Asian older adults, particularly in China. Furthermore, the existing literature lacks analyses of the longitudinal effects of such behavior on well-being and social integration across various social strata, especially when evaluated within a sustainability paradigm.

To address this research gap, this study reframes older adults as active phubbing participants rather than affected individuals and explores their intensive smartphone use via a sustainability lens, focusing on three paradoxes [

31,

32,

33]. It reconstructs the Push–Pull–Mooring theory (PPM) [

34,

35], which adapts push as structural deficits, pull as compensatory digital functions, and mooring as stratification mechanisms. This theoretical framework remains underexploited within gerontological research. Based on in-depth interviews with 24 urban older adults (60–75), this study investigates four core questions about these mechanisms: push drivers, pull affordances, mooring determinants, and cultural operation and sustainability implications. It contributes theoretically by extending PPM to aging contexts, empirically by examining phubbing from a sustainability perspective, and practically by advocating structural reforms for sustainable digital aging.

This study provides a critical framework for achieving a sustainable and inclusive digital future, and the findings are critically aligned with several UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The research supports SDG 3 on health and well-being by highlighting the impact of digital technology on the mental and social health of older adults. It advances SDG 10 on reduced inequalities by exposing epistemic inequality as a foundational driver of digital exclusion for this demographic. The demand for institutional and design-oriented interventions directly advances SDG 9, guiding the establishment of robust and equitable infrastructure for sustainable digital transformation. Additionally, this research underscores the significance of SDG 17 concerning collaborative frameworks. Achieving sustainable digital aging necessitates coordinated interventions across policy architects, technological innovators, and community stakeholders. In the absence of such alignment, digitalization threatens to generate “problem shifting” [

18]. Strategic partnerships mitigate these externalities from exacerbating socioeconomic disparities. Effective collaboration prevents these costs from deepening social inequalities.

The following sections proceed as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on digital stratification and compensatory technology use within sustainability frameworks.

Section 3 describes the research methods.

Section 4 presents empirical themes organized around push–pull–mooring dynamics.

Section 5 discusses theoretical integration and proposes the Digital Compensation Framework.

Section 6 concludes with reflections on policy implications for sustainable digital aging.

2. Literature Review

Research on smartphone use among older adults presents contradictory narratives. Dominant perspectives highlight technology’s function in facilitating active aging through social connection and independence [

19]. Meanwhile, phubbing research stigmatizes intensive digital participation as impulse control failure but focuses almost entirely on young Western populations [

2,

36]. Neither stream explains why older adults persistently engage intensively despite recognizing excessive use as problematic, or why identical behaviors produce drastically different consequences across groups.

These dilemmas stem from three theoretical limitations. Existing research individualizes technology use as a psychological variable, ignoring how institutional arrangements transform voluntary choices into structural coercion. Research assumes homogeneity among older populations, masking the ways in which cultural capital stratifies the consequences of technology use. A sustainability perspective examining whether digitalization patterns serve long-term well-being or merely shift care responsibilities to attention economy-driven platforms remains absent.

This review traces the evolution of digital inequality research from access gaps to outcome disparities, synthesizes sociological explanations of structural deficits and compensatory use, evaluates the Push–Pull–Mooring framework’s relevance and limitations for aging studies, and proposes a theoretical basis for a Digital Compensation Framework that integrates cultural specificity and sustainability.

2.1. From Digital Divide to Digital Stratification

Digital divide research evolved through three stages: from access gaps revealing differences in technology ownership [

37], to skills inequality showing access alone does not ensure effective use [

38] to outcome disparities demonstrating technology only yields benefits when users have the requisite digital capital [

39,

40]. This progression reveals that equalizing access and skills alone fails to eliminate inequality, as underlying social structures determine who benefits from technology participation.

Researchers applying Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital reveal that digital capital accumulation exhibits path dependence [

41]. Higher offline cultural capital yields greater returns when entering the digital sphere, while low capital produces cumulative disadvantage [

42]. Yoon et al. demonstrated that the relationship between educational disparities and the impact of smartphone use is mediated by critical digital literacy, defined as the capacity to assess platform algorithms and resist manipulative practices [

43]. For older populations, Seifert et al. conducted a five-year study, showing that notwithstanding substantial increases in smartphone penetration, among users with similar usage frequency, only highly educated users reported enhanced social connections [

44]. This “digital Matthew effect” [

45] suggests technology amplifies rather than eliminates inequality.

From a sustainability perspective, this stratification reveals how digitalization without structural support undermines social sustainability by exacerbating existing inequalities. When platforms become primary media for social participation, but favor educated and digitally literate users, digital transformation intensifies ageism [

46]. Achieving sustainable digital aging requires examining how technological systems distribute benefits and harms across heterogeneous older populations.

Nevertheless, existing research treats older adults as a homogeneous group, comparing them with younger users while rarely examining within-group heterogeneity. This homogenizing treatment masks how inequality becomes stratified through intensive smartphone use. Furthermore, stratification scholarship predominantly examines behavioral outcomes, such as variations in skill acquisition or usage patterns, while seldom addressing epistemological stratification, specifically the disparities in individuals’ abilities to discern the underlying structural determinants influencing their experiences. Bourdieu noted that dominated groups often internalize narratives of subordinate positions, impeding recognition of shared grievances that could catalyze group efforts [

47]. Such cognitive stratification remains nearly absent in digital participation research among older adults. Our understanding remains limited regarding the extent to which cultural capital influences older adults’ ability to ascribe digital challenges to systemic determinants rather than individual shortcomings.

2.2. Structural Deficits and Compensatory Digital Use

Understanding older adults’ intensive digital participation requires shifting from psychological frameworks that emphasize individual choice to sociological theories that articulate structural constraints. Age stratification theory elucidates how societies distribute roles, opportunities, and resources according to age-based hierarchical frameworks [

48]. When institutional systems do not adjust to shifting demographic patterns, which is a phenomenon Dannefer [

49] describes as structural lag, systematic disadvantages result, such as identity erosion post-retirement, increased loneliness linked to the empty-nest phase after offspring transition to independence, and heightened risks of age-related social marginalization.

Critical gerontology [

50] expands this perspective by analyzing how neoliberal policies push older adults out of offline society [

51] while forcing them into digital participation to access basic services [

1,

52]. When welfare distribution, medical appointments, and transportation systems require smartphone use, usage behavior shifts from free choice to structural coercion. Chinese urban research confirms that older adults were compelled to use smartphones during COVID-19 lockdowns, highlighting the limitations of voluntarism assumptions in technology acceptance models [

13,

53]. From a sustainability perspective, current policy architectures shift care costs from states and families to corporate platforms that generate revenue through attention extraction, while providing limited support for sustainable well-being, exemplifying what sustainability scholars term “problem shifting” [

18].

What sustains user stickiness after structural deficits drive initial adoption? Kardefelt-Winther’s compensatory internet use theory posits that alleviating negative emotions online when encountering negative life situations can trigger problematic internet use [

24]. However, this theory treats compensation as an individual psychological process, ignoring macro-structural conditions and how platform design shapes compensation patterns.

Critical research gaps emerge. While existing research confirms that structural deficits predict loneliness or depression, it has not explored how these deficits drive compensatory digital participation patterns. No research systematically maps correspondences between offline deficits and digital activities. Compensation theory inadequately explains how platform mechanisms maintain user engagement after initial emotional repair. We lack an explanatory framework for how structural conditions interact with platform characteristics to produce sustained high intensity use that may harm rather than promote long-term well-being.

2.3. Push–Pull–Mooring (PPM) Framework and Its Limitations

The PPM framework establishes a theoretical architecture for synthesizing structural push factors, platform pull factors and stratified mooring factors. This theory posits that behavioral change arises from push factors driving change, pull factors attracting alternative options, and mooring factors facilitating or constraining change [

34,

35]. Recently applied in technology contexts [

54], PPM offers potential for analyzing the platform participation of older adults.

However, existing PPM applications have three limitations that weaken their utility for sustainability analysis. PPM psychologizes push factors as individual dissatisfaction rather than structural constraints. Users dissatisfied with one platform switch to others, assuming a voluntary choice, while ignoring how institutional arrangements influence technology adoption. When welfare services require smartphone access, push effects are coercive, not preferential. This individualized framing obscures how policy choices create unmet psychosocial needs that drive compensatory participation.

The PPM framework characterizes pull factors as inherent platform attributes, such as enhanced processing velocities or expanded user networks, rather than as compensatory mechanisms addressing particular unfulfilled requirements. Platform attractiveness depends on matches between digital affordances and offline deficits. Empty-nest parents may find parasocial relationships through short-video platforms particularly compelling, while those experiencing knowledge devaluation may gravitate toward recognition systems offering alternative validation. This contextualized logic explains why powerful network effects have not led to platform monopolization among older users who maintain multi-platform portfolios, addressing different structural deficits.

PPM conceptualizes mooring factors as binary adoption constraints, such as switching costs or learning curves, treating them as barriers to migration rather than mechanisms that produce ongoing stratification. However, anchorage functions in a dual capacity: it simultaneously empowers through authentic capability augmentation, such as navigation applications reinstating spatial self-determination, while also ensnaring individuals through self-perpetuating cycles of dependence, such as the decline in health resulting from extended screen usage, which diminishes mobility and exacerbates digital reliance. Cultural capital moderates which mooring pattern dominates. High-capital users strategically leverage empowering affordances while resisting entrapping mechanisms through multi-platform diversification and offline network maintenance. Low-capital users often concentrate on single platforms, making entire digital social networks dependent on the stability of a single system, which intensifies vulnerability when technical failures or platform policy changes occur.

Most phubbing studies draw their samples from Western populations. However, it’s possible that compensatory mechanisms function differently across cultures, as normative structures influence the subjective interpretations of structural deficiencies. In China, prevalent empty-nest families disrupt traditional co-residence expectations inherent in Confucian filial piety. Empty nests have been found to be a stronger predictor of depression and loneliness in China than in Western countries [

55,

56]. This suggests that cultural differences may amplify the impact of structural deficiencies. Moreover, accelerated digitalization and super-app ecosystems, such as WeChat, create digital lock-in effects, where usage behavior becomes a structural necessity, contrasting with Western societies, where analog alternatives remain widely available. These differences suggest national policy configurations shape digitalization trajectories that either promote or hinder equitable aging processes.

2.4. Research Gaps and Research Objectives

Three critical research gaps emerge from this review. First, there is a noticeable gap in the theoretical underpinnings from a sustainability standpoint, elucidating the mechanisms through which structural determinants stimulate compensatory digital engagement among older individuals. While existing theories document correlations between loneliness or role loss and technology use, they do not clearly articulate linking mechanisms between offline deficits and platform-specific participation patterns. Which structural deficits correspond to which digital activities? How do platform functions satisfy unmet psychosocial needs? What are the ramifications of these engagement modalities on the enduring wellness and resilience of older individuals? Without addressing these questions, we cannot distinguish between adaptive compensation that promotes sustainable aging and exploitative compensation that damages well-being over time.

Second, research has not examined how cultural capital stratifies not only behavioral outcomes but also cognitive frameworks. Do high-capital older adults develop structural critical consciousness when facing identical barriers, while low-capital individuals internalize deficit narratives? Cognitive inequality is the most crucial aspect of digital stratification, as it hinders the collective action needed for structural change toward sustainable digital aging. When low-capital users attribute interface difficulties to personal incompetence rather than ageist design, they are unable to form common demands for age-friendly modifications or platform accountability mechanisms. Understanding this cognitive stratification reveals why the digital divide evolved from exclusion to differentiated inclusion, where everyone uses platforms, but outcomes reveal class differentiation resistant to politicization.

Third, existing research lacks a middle-range theory that integrates push, pull, and mooring mechanisms, while specifying cultural contingencies and sustainability implications. Existing theoretical frameworks remain confined to micro-psychological levels or macro-structural levels, lacking cross-level linkages. We urgently need a theory that explains how structural conditions guide individual choices of specific platforms, how platform functional characteristics satisfy needs that are unmet by offline environments, how existing inequalities moderate outcomes, and whether these patterns contribute to sustainable aging.

These research gaps serve as the starting point for this study. Building on the Push–Pull–Mooring theory and combining structural sociology with sustainability analysis, we construct the Digital Compensation Framework by redefining push factors as structural deficits produced by institutional arrangements, pull factors as contextualized function-need matching where platform affordances address specific offline deficits, and mooring factors as dual mechanisms that simultaneously enable empowerment and entrapment. Through qualitative analysis of 24 urban Chinese older adults’ intensive smartphone use, this study addresses four research questions:

RQ1: What structural deficits (push) drive high-intensity digital participation among older Chinese adults?

RQ2: Which digital platform affordances (pull) provide compensatory resources, and how do they match specific unmet needs?

RQ3: What mooring mechanisms simultaneously empower and entrap older users, and how do these dual processes produce paradoxical consequences?

RQ4: How does cultural capital moderate compensation processes at behavioral and cognitive levels, producing cumulative stratification in digital participation outcomes?

By addressing these inquiries, we can explore the ways in which structural determinants give rise to unfulfilled requirements and how stratification modalities impinge upon the capacity of older individuals to effectively utilize digital platforms. It also discovers whether current digitalization trajectories promote sustainable ageing or merely shift care responsibilities to platforms that profit from attention extraction without supporting long-term well-being.

3. Data and Methods

This study adopts theory-driven thematic analysis [

57] and explores the phubbers phenomenon among urban older adults in China through the analytical framework of sustainable digital aging. This method can not only develop theories based on empirical data but also capture the subjective significance of participants’ digital practices and the structural conditions under which their choices are limited.

3.1. Sampling and Participant Recruitment

To optimize variance, we employed purposive sampling strategy for choosing interview participants. In this study, we define “older adults” as individuals aged 60 and above. This threshold aligns with the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly [

58] and relevant WHO guidelines regarding developing countries. Our analysis specifically focuses on the “young-old” cohort [

59] aged 60 to 75. This subgroup possesses baseline digital skills yet faces significant social role transitions. We excluded adults aged 75 and older due to higher rates of cognitive impairment [

60] which could compromise the depth of semi-structured interviews.

Theoretical sampling directs participant recruitment throughout the analytic and iterative phases of the study. The recruitment was conducted from April to September 2024 through community centers and online elderly activity groups. When describing the experience of using a smartphone, the initial materials should avoid using terms such as “phubbers” and “addiction” to prevent the prior influence of the pathological framework. Eligible participants were required to meet the following stipulations: fall within the 60–75 age bracket, possess a minimum of one year’s experience using a smartphone, and self-report a mean daily engagement of at least four hours. They should be able to sustain a conversation for over 60 min and conduct in-depth discussions in fluent Mandarin. Individuals currently residing in institutional care facilities or those with a diagnosed cognitive impairment will be excluded from the study.

Aligning with the guidelines for attaining data saturation within comparatively uniform groups, and informed by theoretical investigations [

57,

61], our selection process culminated in a cohort of 24 participants. During the 22nd through 24th interviews, the absence of novel codes or thematic categories, with only iterations of established themes emerging, suggested that thematic sufficiency was achieved. The study cohort consisted of 10 male and 14 female participants, ranging in age from 60 to 75 years (mean age, 69.0 years; SD, 3.8 years). The educational attainment of the participants ranged from primary school (

n = 3) to a master’s degree (

n = 3), including those with junior high school (

n = 6), senior high school (

n = 5), junior college (

n = 2), and bachelor’s degree (

n = 5) qualifications. The professional background encompasses a broad spectrum, from agricultural labor to university professor. The study population’s residential arrangements comprised 10 empty-nest households, eight conjugal households, and six households cohabiting with adult offspring. Participants’ daily smartphone usage ranged from 4 to 9 h. All participants have been using smartphones for more than three years to ensure that the data reflects the continuous usage patterns rather than the characteristics of the initial adoption stage.

Table 1 shows the detailed characteristics of the participants.

It should be noted that although our sample is comprehensive, it is confined to urban populations. We recognize that the findings may not be generalizable to rural or economically disadvantaged groups where digital access and infrastructure vary substantially. In addition, concerning socioeconomic status, this variable was not controlled during participant recruitment. Rather, differences in cultural capital and social stratification emerged organically through our analytical process.

3.2. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews lasted between 55 and 110 min (mean = 78 min) and were conducted in participants’ homes (n = 11), community centers (n = 8), or via WeChat video calls (n = 5). All interviews were audio-recorded with participant consent.

The interview guide covered four main areas. The first part focused on life background, using open-ended questions such as “Please talk about your life after retirement” to avoid presupposing negative experiences. The second part examined digital practices. Questions like “Please describe your typical daily routine of using a mobile phone” often prompted participants to demonstrate commonly used applications, revealing unspoken behavioral patterns and usage difficulties. The third part explored behavioral consequences through questions such as “Does mobile phone use affect your health or interpersonal relationships?”. When participants acknowledged problems yet continued high-intensity mobile phone use, this revealed a disconnect between cognitive awareness and actual behavior. The fourth part probed structural attributions by presenting contrasting viewpoints: “Some people believe that older adults struggle with technology due to aging; others argue that technology itself is not designed for older users. Which view resonates more with your experience?”. This question helped determine whether participants attributed difficulties to personal limitations or structural shortcomings.

Several adjustments were made to accommodate participants: using life history approaches as entry points, providing large-font materials for those with hearing difficulties, maintaining a conversational tone, and incorporating rest breaks during longer sessions. The research design strictly adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. In addition, to protect participants’ privacy, we assigned pseudonyms and encrypted all digital data. We also addressed vulnerability by offering frequent rest breaks and excluding individuals with cognitive impairments. Finally, member checking allowed participants to verify the accuracy of our records.

All interviews were transcribed verbatim in Chinese within 48 h, with notations marking laughter, pauses, and other paralinguistic features that conveyed emotional expression. Transcripts were imported into NVivo 15 software using anonymous identifiers (P-A to P-X). The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board.

3.3. Data Analysis

The analysis followed the iterative process of thematic analysis approach [

57], initiating coding work after the third interview, and data collection was carried out simultaneously. The entire analysis process is divided into three stages:

The first phase is the initial coding. All 24 interview records were coded line by line, generating a total of 156 coding items, covering the participants’ expressions and behavioral observations, such as “Talking more with strangers than with family members”, “becoming invisible after retirement”, “resisting home surveillance”, etc.

The qualitative data management and coding process were facilitated by NVivo software (Version 15, Lumivero, Denver, CO, USA). We utilized matrix coding queries to cross-tabulate themes against participant characteristics like education level to identify patterns of cultural capital. Additionally, over 60 analytic memos documented our coding decisions and ensured an auditable research trail. To enhance analytical rigor, we also employed a research assistant as an independent secondary coder to analyze a subset of interview transcripts. The initial comparison yielded a Cohen’s kappa of 0.73, prompting us to refine codebook definitions through collaborative negotiation. This recursive dialogue enabled us to refine analytical precision and methodological sophistication. For instance, we subdivided the broad category of family conflict into distinct codes: infantilizing control, asymmetric judgment, and epistemic evaluation. A subsequent round of coding confirmed improved consistency with a final kappa of 0.89, while persistent interpretative differences were retained to reflect the complexity of intergenerational dynamics.

The second phase is the theme identification. Through continuous comparison of cross-interview records, we consolidated 156 codes into 19 thematic topic categories (see

Table 2) and examined how these thematic changed with the different characteristics of the participants. Among them, cultural capital becomes a key moderating variable: participants with high cultural capital put forward structural criticism (for example, “This is a design of age discrimination”), while those with low cultural capital attributed their failure to themselves (for example, “My brain is not good enough”). In addition, living patterns also have an impact on behavioral patterns: empty-nest participants exhibit stronger pseudo-social attachments, while those living with family members face more intense intergenerational conflicts. All high-capital participants (

n = 10) made structural attributions, whereas most low-capital participants (7/10) attributed their failures to themselves.

The third phase is the thematic refinement and integration. The 19 categories have been integrated into five dimensions of the digital compensation framework: (1) Structural driving factors (4 themes); (2) Digital Pull Empowerment (4 Themes); (3) Competency Anchoring factors (4 themes); (4) Stratification of Cultural capital (2 themes); (5) Paradoxical Consequences (5 themes). These dimensions are formally summarized into five propositions (

Section 5).

Finally, both authors acknowledge their dual positionality as adult children of aging parents and digital sociology researchers. This positionality influenced data collection and analysis through three primary mechanisms. First, shared generational experiences enabled rapid establishment of trust, facilitating in-depth exploration of daily challenges surrounding digital adaptation that might otherwise remain unexpressed. Second, personal proximity to the research topic presented potential for over-identification with participants’ narratives regarding familial oversight. To address this methodological concern, we systematically sought alternative perspectives emphasizing the protective motivations underlying such surveillance practices. Third, our theoretical grounding in critical gerontology oriented the research team toward structural interpretations. We counterbalanced this analytical framework through rigorous member validation. When participants challenged our understanding of intergenerational tensions, we integrated their corrections to capture the complex interplay between ageist assumptions and authentic caregiving concerns.

Table 2 presents the analytical evolution process from 156 initial codes to 19 intermediate categories and then to the five major theoretical dimensions and is organized according to the components of the framework.

4. Research Results

Based on 24 in-depth interviews, this section examines how structural deficits drive intensive smartphone engagement, how platform affordances provide compensatory resources, and how these processes produce paradoxical outcomes. Cultural capital influences both participation patterns and participants’ ability to interpret experiences in a structural rather than an individualistic manner.

4.1. Structural Push: Institutional Deficits Driving Participation

Intensive smartphone use among older adults stems from structural deficits that produce offline dissatisfaction. Four interrelated deficits emerged as mutually reinforcing forces driving digital substitution.

Migration-induced separation and empty-nest loneliness. Place-based welfare entitlements and the territorial allocation of public services raise the cost of family migration, particularly for households seeking to relocate across administrative boundaries [

62,

63]. Against a backdrop of uneven employment opportunities, these institutional barriers channel working-age adults toward destinations with stronger labor demand, while elderly parents typically remain in their places of origin [

64,

65]. This pattern of spatially fragmented families weakens intergenerational co-residence [

66,

67] and reconfigures caregiving arrangements in later life [

68].

Research confirms that spatial separation predicts loneliness more strongly in collectivist Asian societies than in Western contexts due to violated co-residence norms [

69]. P-A described his daily routine:

“My phone is always in my hand. The house is empty, my three children work in Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou. They visit twice yearly.”

Empty-nest participants reported substantially longer daily usage times compared to those living with family members, regardless of educational background. P-F, whose children live abroad, developed sustained parasocial attachments to compensate:

“I’ve watched this family vlogger daily for three years. It feels like watching my own grandchildren grow up. My real grandchildren live far away, but this child I see daily.”

This pattern illustrates how isolated older adults establish parasocial relationships through social media interactions [

70].

Retirement-induced role loss. Retirement led to identity ruptures, particularly severe for those who had previously defined themselves through their professional expertise. P-B reflected on this abruptness:

“For forty years, I was Professor Zhang. Students respected me, colleagues consulted me. Then overnight, I became nobody.”

P-B eventually restored aspects of his professional identity through technical Q&A communities where younger scholars consulted him: “Online, I’m still a professor. People ask me professional questions. My knowledge still matters”. This pattern of preserving professional identity through digital platforms was primarily observed among highly educated participants. In contrast, those who had engaged in manual labor viewed retirement as a physical relief rather than an existential crisis. This differential experience aligns with Atchley’s continuity theory, which posits that successful aging depends on maintaining valued social roles [

71].

Intergenerational knowledge devaluation. China’s expansion of university enrollment from 1.55% (1978) to 54.4% (2020) created stark generational divides in educational credentials [

72]. P-Q recounted her daughter’s dismissals:

“My daughter says traditional crafts are outdated, that nobody cares about needlework anymore. When I share health information, she immediately says I don’t understand science. A lifetime of experience seems worthless.”

Platform recognition systems provided alternative validation. P-Q’s needlework tutorials attracted thousands of followers who referred to her as “teacher” and sought her guidance. She contrasted this digital recognition with family devaluation: “Online, people value my knowledge. They call me ‘teacher,’ ask me to explain techniques. That recognition, I don’t get it from my own family”. Yet this compensatory validation also created new dependencies, with self-worth becoming linked to follower counts.

Age-based spatial exclusion. Chinese urban design favors young consumers, leaving many older adults feeling uncomfortable in public spaces. P-S explained her withdrawal:

“Shopping mall music gives me headaches. Parks have exercise equipment I can’t use. Even sidewalks feel hostile, with electric scooters whizzing past. These spaces tell me I don’t belong. At home with my phone, no one judges my age.”

This exclusion worked with other deficits to produce feedback loops. Prolonged device use led to physical discomfort, reduced mobility, decreased outdoor activities, and intensified phone reliance. P-I elaborated: “My neck and back hurt from looking down all day, so I lie down to use them, which makes me less active. Now, my mobility is worse, and going out becomes harder; as a result, I use my phone more. I’m trapped in this cycle”.

These four deficits reinforce each other: migration causes separation, retirement disrupts daily structure, intergenerational devaluation undermines social value, and spatial exclusion removes public alternatives. Together, they create conditions where intensive smartphone use represents rational adaptation to structural constraints rather than irrational impulse (see

Table 3).

4.2. Contextualized Pull: Function-Need Matching Logic

Platform affordances achieve function-demand matching with users’ unmet psychosocial needs, creating participation stickiness. While attention economy design amplifies usage intensity, interview evidence suggests that compensatory mechanisms drive continued participation by providing effective pathways that satisfy demand.

Parasocial relationships as alternative intimacy. Where families are spatially separated, platforms enable creators to meet audiences’ emotional needs through carefully arranged content. The family vloggers P-H follow their imagination of their own children’s lives:

“I watch their dining scenes, daily conversations, interactions with children—it’s like looking at a family who once lived together. Sometimes I forget they’re strangers. When they don’t update for a week, I genuinely worry.”

P-H recognized this relationship as one-sided, and the intimacy as artificially created, yet the emotional comfort remained genuine. This paradox reflects what media scholars term the “Para-Social Interaction” [

73], where audiences form affective bonds despite knowing interactions are mediated and non-reciprocal. Multiple participants acknowledged these relationships weren’t genuine but still gained psychological comfort from them.

Ambient intimacy through continuous connection. Many participants described WeChat groups as creating “online living rooms” through low-intensity communication. P-C maintained hundreds of contacts across dozens of groups, checking messages repeatedly throughout each day:

“Group chats make me feel friends are beside me, even when we haven’t met for months. Nobody discusses important matters—just seeing their messages and photos makes me feel less lonely. It’s like the teahouses we used to visit.”

This pattern exemplifies the “ambient intimacy”, where continuous lightweight exchanges maintain social presence without demanding intensive interaction [

74]. For migration-separated families, video communication platforms achieved sustained connection across distances. P-X, whose children live overseas, described their cross-border arrangement. “My daughter and I cook together via video call. She shows ingredients from an American supermarket, and I guide her through Chinese dishes. Though we’re thousands of miles apart, we still ‘have dinner together’”. Many participants noted limitations.

“It’s better than nothing, but the screen separates us. We cannot embrace, cannot truly share the meal.”

(P-M)

Professional knowledge validation communities. Content platforms spawned niche communities where traditional skills gained admirers. P-Q drew a clear distinction between platform recognition and family dismissal.

“My daughter said embroidery is a dying art nobody cares about, but thousands of fans think otherwise. They ask detailed technique questions and tell me I’m protecting cultural heritage. Finally, someone recognizes what I’ve mastered.”

This recognition mattered especially for participants whose professional value was devalued in everyday life. Yet when engagement metrics declined, this recognition brought vulnerability. P-Q admitted she compulsively checked follower counts and grew frustrated when a post got fewer likes than usual. Research on older content creators documents similar patterns where platform metrics become proxies for social worth [

75].

Digital archaeology enabling relationship recovery. Alumni reunion groups facilitated the reconnection of former classmates who had been separated for decades. P-O described how junior high classmates gradually reunited online:

“Someone started a group, then invited others one by one. Within months, thirty classmates from fifty years ago had reconnected. We share old photos, remember deceased teachers, talk about current lives, as if time reversed.”

This functionality addresses late-life stages where mortality becomes salient and life review prominent. Multiple participants maintained the coherence of their personal narratives through reestablishing ties with foundational identity constructs and meaningful relational bonds. Given mobility limitations and geographic dispersion, offline reunions were logistically unrealistic.

These four affordances address genuine psychosocial needs unmet in the original framework. Yet the compensatory resources they offer come bundled with attention economy logic, leading to problematic outcomes (see

Table 4).

4.3. Mooring Duality: Coexistence of Empowerment and Entrapment

Smartphones don’t just fill functional gaps—they expand what participants can do in ways that feel empowering. Yet compensatory participation simultaneously produced adverse effects for most participants. Empowerment and exploitation coexist rather than occurring sequentially, pointing to sustainability challenges.

4.3.1. Empowering Anchors

Cognitive agency in health decisions. Mobile health platforms enabled people without medical training to participate in informed decisions about their care. P-N contrasted current versus past doctor-patient interactions:

“Before smartphones, I passively followed doctors’ orders. I couldn’t understand my condition or judge treatment plans. Now I study diagnostic results, research options, and arrive at appointments with specific questions. I’m involved in decisions about my own health.”

This empowerment meant more for participants with less formal schooling. P-L explained how online information helped her avoid unnecessary surgery: “The doctor said I needed surgery immediately, but I found articles about conservative treatment showing similar cases improved without operations. I mentioned these options. The doctor reconsidered. We tried conservative treatment, and it worked”. Research confirms that internet-enabled health information seeking can empower older patients, though effectiveness depends on digital literacy levels [

76].

Spatial autonomy through navigation. Digital maps restored spatial confidence eroded by declining abilities. P-V emphasized how much this mattered: “Before smartphones, I couldn’t go anywhere unfamiliar alone. New routes confused me, so I depended on my kids to drive me. That dependence was hard. Now I explore new neighborhoods confidently, even went to Beijing alone and figured out subway transfers I thought impossible”.

Financial independence via mobile payment. For some participants, this brought dignity as well as convenience. P-K, a retired accountant, discussed financial dependence: “Before mobile payment, I had to ask my son for cash every time I went shopping. At my age, asking for pocket money was humiliating, like turning back into a child. Now I handle my own pension. That autonomy means everything”.

Yet fintech didn’t feel empowering to everyone. Participants with less digital skill constantly worried about mistakes. P-U expressed ongoing fears: “Sometimes I’m scared I’ll hit the wrong button and send money to the wrong person. The interface feels designed to confuse people like me”.

These expanded capabilities demonstrate genuine autonomy, setting digital support apart from mere dependence. Yet, technical failures or platform policy changes quickly created new vulnerabilities, as evident when participants had their accounts frozen or devices broke down (see

Table 5).

4.3.2. Entrapping Dependencies

Physical health deterioration. Many participants developed musculoskeletal problems, eye strain, and sleep disruption. P-F experienced emotional comfort through parasocial attachment but also suffered from chronic pain.

“I keep my head down all day looking at my phone, causing constant neck and back pain. The pain means I can only lie down and look at my phone, so I’m even less active. My reduced mobility makes me less willing to go out, which makes me more dependent on my phone. I’m caught in a vicious cycle that I can’t escape.”

This feedback loop appeared across multiple cases: health problems resulting from device use weakened mobility and outdoor activity, making screen use the only realistic daily option, which in turn exacerbated existing health issues.

Psychological dependence. P-C described her relationship with WeChat groups:

“I can’t help checking my phone every few minutes, even when there are no new messages. Leaving the phone in another room makes me anxious, even knowing there’s nothing urgent.”

The gap between awareness and behavior was evident. Participants recognized their usage patterns as problematic but found it challenging to change habits. P-D described this predicament: “I understand I should look at my phone less. I tell myself every day to cut back, but then what? Sitting alone in the apartment, I would stare at the empty walls. At least the phone gives me something”.

Financial fraud. Scams targeted emotional vulnerabilities rather than cognitive deficits, exploiting victims’ loneliness through carefully built social relationships. P-R, a retired accountant with decades of banking experience, was defrauded of ¥50,000:

“Everyone in the group called each other ‘auntie’ and ‘uncle,’ just like family. Every day we chatted about grandchildren, discussed health issues, and shared meal photos. It felt like genuine friendship. When investment opportunities came up, it felt like family helping each other. I never suspected fraud because this wasn’t a cold transaction. They spent months before talking about money, already building what seemed like a real relationship.”

P-R’s professional financial knowledge proved useless against social manipulation. She reflected: “In professional settings, I easily spot financial scams. But this was different. They exploited my loneliness, not gaps in my knowledge”. After this incident, P-R blamed inadequate platform oversight rather than personal gullibility. Research on elder fraud confirms that social engineering tactics exploit affective rather than cognitive vulnerabilities [

77].

Family conflicts from “infantilizing” control. P-E’s son enforced daily usage limits through monitoring software, which she saw as deeply disrespectful:

“My son installed software limiting my phone use to three hours daily and tracking which apps I use. I raised him from birth, but now he treats me like a child who can’t manage time responsibly. The more he restricts me, the more I want to use my phone. It’s not that I really need it that much, but my freedom and dignity feel violated.”

P-E eventually figured out how to delete and reinstall the monitoring software to hide usage traces: “We’re now in a power struggle. This isn’t about the phone anymore, but whether I’m still an adult who deserves autonomy”.

Several participants observed that families often made asymmetric judgements when using electronic devices simultaneously, with older adults frequently being criticized. P-X described this typical scenario: “We sat together, everyone looking down: my son checking stocks, daughter-in-law chatting, grandson playing games, me reading the news. But they said, ‘using it too long is bad for your eyes,’ telling me to use it less. Why is it only I who sees the problem?”.

Intergenerational cognitive conflicts extended to the systematic dismissal of the knowledge that older adults acquired and shared through various platforms. Thirteen participants (54%) reported such experiences. P-M recalled repeated conflicts: “I forwarded health articles on nutrition and traditional therapies, but she wouldn’t even look and declared them all junk. When she found scientific papers and sent them to me, she expected me to treat them as the absolute truth. We both get information from the internet. Why is her knowledge legitimate while mine is not?”.

These consequences illustrate how compensatory participation can lead to adverse effects on physical health, psychological well-being, financial security, and family relationships. Yet when participants interpreted these consequences, significant differences emerged in structural versus individualized explanations along cultural capital lines (see

Table 6).

4.4. Cultural Capital as a Stratifying Moderator

Digital inequality’s most crucial dimension lies not in access differences or usage patterns, but in the ability to recognize the structural forces that shape experiences. Cultural capital differentiates both participation behaviors and interpretive frameworks, leading to cumulative divergence in outcomes.

Behavioral stratification. Participants with higher levels of education showed more strategic platform use. P-B described her usage boundaries. P-B described her usage boundaries: “I keep my platform use very distinct. WeChat is only for contacting family. I also insist on meeting old friends for tea once a month. Online cannot completely replace offline. These tools are aids, not everything”.

By contrast, participants with less education recognized problems but lacked strategic differentiation. P-W reflected: “I basically rely on WeChat for everything. I scroll through group chats in the morning, and suddenly it’s afternoon and I haven’t done anything else. I know I should control my usage time, but I don’t know how because each thing seems indispensable at the moment”.

The phrase “don’t know how” reveals the essence of low-capital participants’ predicament, which is not a cognitive deficit but a lack of operational knowledge to transform awareness into practice.

This pattern aligns with Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital, where educational credentials provide not just skills but “schemes of perception” that enable strategic action [

47]. Infrastructure fragility made this difference concrete. When device failures, platform malfunctions or operational errors made WeChat unavailable, users who relied on a single platform experienced a systemic collapse of their digital social life. In contrast, those who maintained multi-channel contacts were able to preserve their connections.

Cognitive stratification. Cultural capital influenced how participants interpreted identical predicaments, producing different psychological outcomes. Highly educated groups demonstrated structural critical capacity, tracing interface barriers to ageist design principles and platform capital logic. P-B connected specific usage difficulties to underlying business models rather than attributing them to personal ability:

“These applications assume users are all young people with superior vision and quick reflexes. Tiny fonts, complicated navigation, brief delays before screens reset, this is ageist design. Developers ignore our needs because we don’t belong to the target market or profitable user group. This is discrimination.”

Such structural criticism protected psychological health by avoiding self-blame while identifying intervention targets, creating possibilities for political mobilization. When P-R experienced fraud losses, she concluded: “These needs policy solutions, stronger platform accountability mechanisms, and more complete regulatory frameworks. It cannot be solved just by individual caution”.

Participants with lower levels of education who faced similar barriers tended to blame interface difficulties on personal incompetence, demonstrating an internalized attribution.

“These apps are a bit too complicated for people like me. I’m not smart enough to understand all the functions. Young people learn things much faster. We elderly can only accept our limitations. Technology development has already exceeded what people like me can handle.”

(P-T)

After experiencing fraud losses, P-T blamed herself entirely: “I was too naive, too trusting. Others would not fall for it. It’s all because I am stupid”. This self-reproach triggered an intense sense of shame, which prevented her from seeking help and blocked her awareness of structural problems. She had completely internalized responsibility for these problems, attributing them to defects in platform governance.

Mechanisms producing cognitive stratification. Three mechanisms jointly produced this cognitive stratification. First, the educational background provided conceptual tools for structural attribution. Highly educated participants articulated usage predicaments as “platform design only considers young people” or “businesses ignore elderly users for profit” rather than “I can’t learn”. Second, occupational experience shaped attribution habits through long-term work practice. Management and education backgrounds made participants accustomed to analyzing institutional environments and process defects, while manual labor backgrounds reinforced thinking patterns of “solving problems through personal effort under given conditions”. Third, social networks influenced the accessibility of different interpretive frameworks. In high cultural capital groups’ social circles, discussions about platform problems more often pointed to design flaws or business logic issues. In contrast, the exchanges of low capital groups focused more on personal coping skills or self-blame. This pattern reflects what Robinson et al. term “digital capital” [

78], where offline advantages compound into online disparities through differential skills, usage patterns, and outcomes.

This cognitive stratification determined whether identical usage predicaments would be understood as “unreasonable platform design” or “inadequate personal ability,” which then affected coping strategies. The former might seek external support, propose improvements, or participate in protecting consumer rights. The latter tended toward self-blame, reduced usage, or complete reliance on others. Notably, even though low-capital elderly groups equally bore the adverse effects of unfriendly design, their individualized attribution weakened possibilities for forming collective demands, such as demanding age-friendly modifications or strengthened platform regulation.

Cultural capital differences influenced the cognitive frameworks of older adults in relation to digital predicaments, leading to cumulative differentiation across multiple dimensions, including platform usage strategies, social network maintenance, time boundary management, and psychological coping (see

Table 7). This multi-level inequality mutually reinforced itself through several processes that increased vulnerability for low cultural capital groups: relying on a single platform raised technical risks; offline social networks weakened, reducing support systems; and individualized attribution made help-seeking less likely.

4.5. Multi-Level Impacts: From Individual Symptoms to Systemic Consequences

The preceding sections documented phubbing’s paradoxical effects at the individual level. However, these micro-level experiences aggregate into meso-level community changes and macro-level societal challenges, revealing phubbing as a structural phenomenon rather than isolated deviance.

(1) Micro-level impacts. At the individual level, phubbing produces health costs, psychological dependency, financial vulnerability, and family tensions. These manifest as reduced quality of life despite initial compensatory relief. P-F’s case exemplifies this duality. Parasocial attachments alleviated loneliness but produced chronic neck pain that further limited mobility, creating a self-reinforcing cycle.

(2) Meso-level impacts. At the community level, intensive smartphone use diminishes local social capital. Sixteen participants reported reduced participation in neighborhood activities, replacing face-to-face civic engagement with online information consumption. This threatens community cohesion traditionally sustained through physical co-presence. Family caregiving burdens increase as adult children must manage tech-related problems (e.g., password resets, fraud prevention, health monitoring), creating new dependencies that paradoxically contradict smartphones’ empowering potential. Intergenerational tensions over asymmetric usage judgments fragment family solidarity, with describing such conflicts as “cold wars” or “power struggles”.

(3) Macro-level impacts. The platforms extract economic value through attention monetization and targeted advertising without corresponding contributions to social welfare or care infrastructure, exemplifying what critical theorists characterize as “data colonialism” [

79]. Furthermore, cognitive stratification suppresses collective mobilization for age-friendly reforms. Low cultural capital groups’ self-blame prevents formation of common demands for regulatory intervention or inclusive design standards, allowing exploitative practices to persist unchallenged.

(4) Cross-level reinforcement. These levels mutually reinforce through feedback mechanisms. Micro-level health decline reduces outdoor mobility, intensifying digital dependency. Meso-level community withdrawal weakens offline support networks that might buffer vulnerability. Macro-level policy inaction, resulting from cognitive hierarchies that impede unified advocacy, allows structural deficits to persist, reproducing conditions that drive compensatory participation. This multi-level cascade reveals phubbing not as individual pathology but as systemic mismatch between rapid technological change and lagging institutional adaptation.

These findings underscore the need for interventions targeting institutional roots rather than individual behaviors. Sustainable digital aging requires reforms at all three levels.

5. Discussion

This study challenges the pathologizing interpretation of intensive smartphone use among older adults, proposing instead that such behavior represents rational adaptation to structural deficits. The findings posit that instead of pathologizing high-intensity technology use as an addiction necessitating behavioral interventions, as prior studies have [

2], it should be understood as an adaptive response to structural inadequacies. These include immigration policies fostering familial separation, mandatory retirement devaluing experienced contributions, educational advancements marginalizing vocational skills, and urban development patterns promoting age-based social exclusion of seniors from community life. The paradigm shift from individual pathology to structural causation introduces new pathways for digitally sustainable aging.

5.1. The Digital Compensation Framework (DCF): Reconstructing Push–Pull–Mooring

This study employs Push–Pull–Mooring theory [

34,

35] as the analytical foundation, as its bidirectional dynamic logic captures offline deficits and platform pulls, its mooring dimension explains persistent participation despite harm, and its middle-range abstraction accommodates macro institutional arrangements and micro cognitive mechanisms. However, PPM’s consumer behavior origins limit its application to older adults’ digital participation.

First, traditional PPM assumes users voluntarily switch platforms due to dissatisfaction. We demonstrate that older adults cannot “switch” away from structural deficits like empty-nest loneliness or retirement role loss. Migration between platforms occurs not due to dissatisfaction but because different platforms compensate for different deficits. WeChat provides ambient intimacy for daily connection needs, while content platforms offer parasocial relationships for deeper emotional voids. This function-need matching logic explains multi-platform portfolios that PPM’s switching cost framework cannot account for.

Second, compensatory internet use theory [

24] treats compensation as individual psychological coping. We structuralize this process. Compensation needs arise not from random negative events but from systematic institutional arrangements. Hukou policies create spatial family separation. Mandatory retirement creates role voids. These are not individual misfortunes but population-level patterns requiring structural interventions rather than behavioral modification.

Third, the third-level digital divide research documents outcome inequalities [

39,

40]. We identify the mechanism producing these outcomes. Cultural capital stratifies not just behaviors but cognitive frameworks. High-capital users attribute interface difficulties to ageist design. Low-capital users blame personal incompetence. This cognitive inequality prevents collective demands for platform accountability, perpetuating exploitation. We term this the fourth-order digital divide: inequality in recognizing and resisting structural exploitation.

Based on these corrections, we propose the Digital Compensation Framework (DCF) as a middle-range theory for understanding older adults’ technology participation under structural constraints (

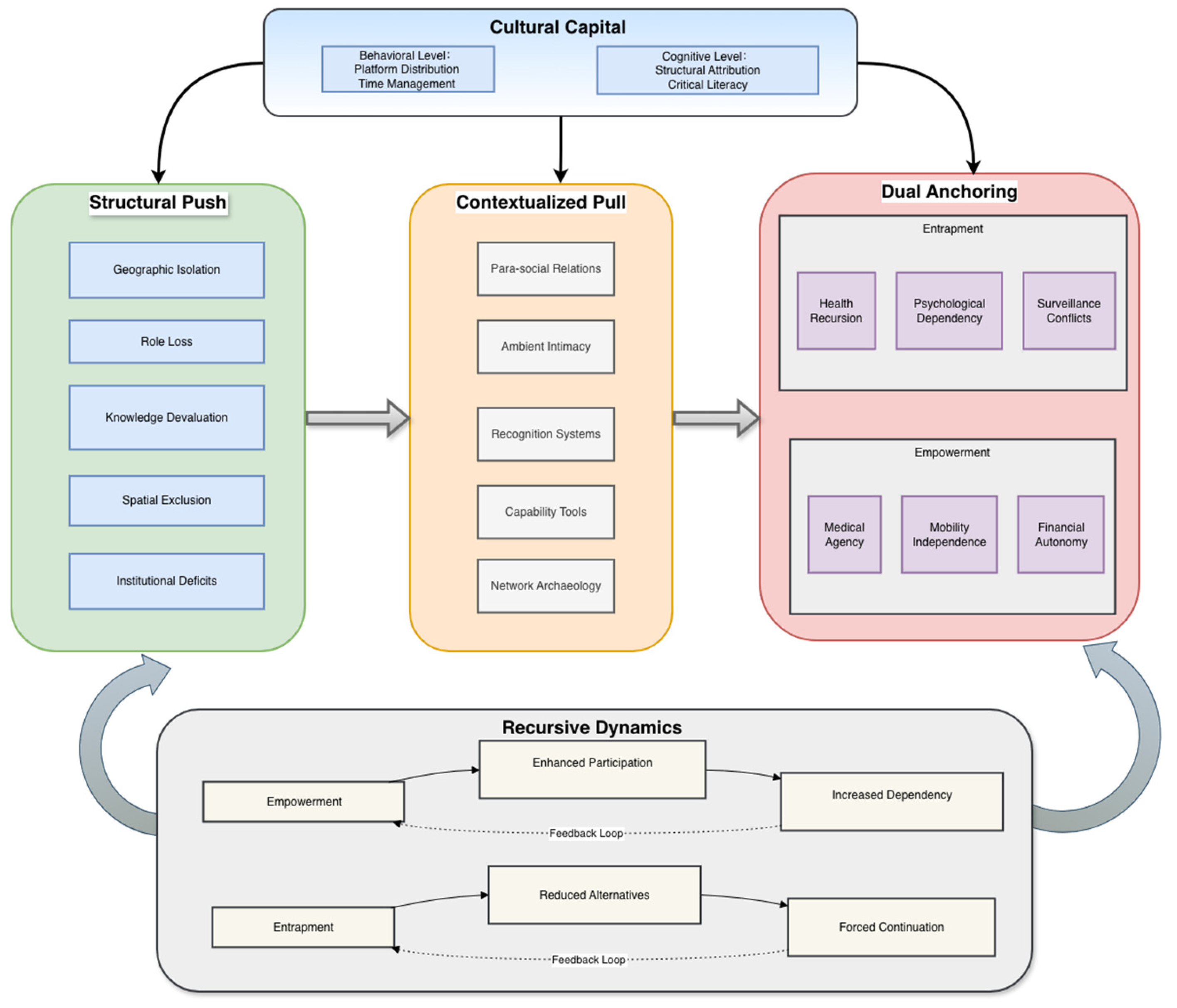

Figure 1). Five interrelated propositions constitute its core:

First, structural causation. Institutional deficits fundamentally drive compensatory participation. Deficit severity positively predicts participation intensity, independent of individual traits like educational background or digital literacy.

Second, contextualized matching. Platform choices follow function-need matching logic. Cross-platform migration resistance correlates positively with the irreplaceability of specific platform functions for targeting particular deficits.

Third, mooring duality. Mooring mechanisms bifurcate into empowering anchors (enabling capability expansion) and entrapping dependencies (creating exit barriers). Both may coexist in the same user.

Fourth, cultural capital moderation. Cultural capital moderates compensation effects at behavioral levels (platform usage strategies) and cognitive levels (attribution patterns). When capital convertibility is low, compensatory participation may intensify rather than alleviate vulnerability.

Fifth, recursive dynamics. Compensation strategies trigger self-reinforcing feedback loops, transforming initially adaptive responses into dependency traps. Loop direction is jointly moderated by cultural capital and external support systems.

This framework transforms PPM from a micro-theory explaining consumer platform migration into a meso-analytical model for understanding technology participation under structural constraints (

Figure 1).

Table 8 synthesizes the operational mechanisms and stratification effects across DCF dimensions, and

Table 9 clarifies DCF’s conceptual advances relative to existing theories.

Digital divide research evolved from access inequality [

80] to skills inequality [

38] to outcomes inequality [

39]. Our analysis extends this trajectory by identifying cognitive inequality as the central mechanism driving these stratified outcomes. This shifts the core inquiry beyond technical competence. The critical question is not whether older adults can use technology, but whether they can recognize and resist systemic exploitation.

Section 4.4 documented three cognitive dimensions distinguishing high and low cultural capital groups. First, problem recognition. High-capital users identify “design malice” as manipulative platform architecture. Low-capital users attribute interface barriers to personal incompetence. Second, responsibility attribution. High-capital users externalize (systemic problems, business logic). Low-capital users internalize (personal skills, inadequate effort). Third, resistance capacity. High-capital users strategically construct defenses through multi-platform diversification and usage boundaries. Low-capital users lack operational knowledge to transform awareness into practice.

Cognitive inequality’s most profound impact lies in suppressing collective action. Low-capital groups equally bear unfriendly design and platform exploitation. Yet their individualized attribution blocks consumer rights organizing, policy demands for age-friendly modifications, and regulatory pressure for platform accountability. This pattern reflects “recognition injustice” [

81], where dominated groups internalize deficit narratives that prevent politicization of shared grievances.

This explains how the digital divide evolved from “exclusion” to “differentiated inclusion” [

82], everyone uses platforms. However, usage outcomes reveal class differentiation, and this inequality resists politicization due to the absence of common demands. Cognitive inequality becomes the “invisible mechanism” that maintains digital capitalism by causing victims to attribute exploitation to themselves, thereby suppressing collective resistance to exploitative design.

Where high-capital users translate structural problems into political demands for design reform, low-capital users’ self-blame forecloses possibilities for collective mobilization. This cumulative disadvantage mechanism [

49] creates a spiral descent vulnerability trajectory for low-capital groups in the digital age.

5.2. Cross-Cultural Contingencies: Phubbing Behaviors in Eastern Versus Western Cultural Contexts

Compensatory mechanisms exhibit distinct operational patterns contingent upon cultural frameworks. While phubbing research originated in Western settings [

2,

3], critical differences suggest distinct dynamics in Eastern societies. Three dimensions differentiate Chinese older adults’ phubbing from Western counterparts.

(1) Normative structures and deficit perception. In Confucian-influenced societies, empty-nest arrangements violate filial piety norms emphasizing intergenerational co-residence [

22]. Spatial family separation represents moral failure rather than lifestyle choice. Research confirms empty-nest status predicts depression more strongly in China than Western nations [

55,

56]. This cultural amplification intensifies structural push factors driving compensatory digital use. By contrast, Western individualist cultures normalize independent living in later life. Empty nesting there reflects successful aging and autonomy rather than family abandonment [

83]. Consequently, Western older adults experience less acute psychosocial deficits requiring digital compensation.

(2) Digitalization trajectories and path dependency. China’s “leapfrog” digitalization created technological lock-in absent in gradual Western transitions. During COVID-19, Chinese elders faced absolute exclusion without health code apps [

13,

53]. Western counterparts retained analog alternatives like paper-based systems. This transforms technology use from preference to structural coercion. Moreover, Chinese super-app ecosystems (WeChat integrating messaging, payment, social media, government services) create higher switching costs than Western single-function platforms. When entire social networks migrate to one platform, non-adoption means social death. This binary differs from diversified Western digital ecosystems where multiple platforms serve separate functions.

(3) Institutional configurations and policy environments. Mandatory retirement ages create abrupt role transitions. Western phased retirement options allow gradual adjustment [

84]. Hukou-based welfare restrictions intensify migration-induced family separation in China. Western welfare portability enables family mobility. These institutional differences suggest compensatory phubbing may be more intensive and harder to resist in Eastern contexts where cultural norms, policy configurations, and technological architectures converge to intensify push factors while limiting exit options (see

Table 10).

5.3. Policy and Practical Implications: Toward Sustainable Digital Aging

Current digital sustainability frameworks rarely address aging populations. Through linking the DCF to the sustainability scholarship, we identify three mechanisms that move beyond simple SDG alignment to guide specific policy shifts.

The first mechanism is the non-substitutability of embodied care. Drawing on sustainability science, we distinguish weak sustainability, where technology replaces depleted resources, from strong sustainability, which recognizes irreplaceable resources. Our findings align with the latter that digital communication cannot fully substitute physical presence. However, policies often proceed as if it could. Empty-nest loneliness, rooted in migration policies and care infrastructure gaps, is monetized by platforms that extract attention, shifting care duties from states to corporations, which is a pattern Santarius et al. identify in environmental contexts [

18]. To address this under SDG 3, policy must target root causes through structural changes like intergenerational living support and gradual retirement, rather than penalizing adaptive digital coping strategies.

The second mechanism involves digital rebound effects. Energy research documents rebound effects where efficiency gains increase total consumption [

85]. Similar dynamics appear in digital aging. Smartphones initially empower older adults through navigation apps. Yet expanded capability enables greater usage. This produces health deterioration and reduces offline mobility. Linear adoption models miss these feedback loops. Sustainable interventions must design circuit breakers to prevent such spirals.

The third mechanism is stratified sustainability. Sustainable systems should distribute benefits and harms fairly [

86]. However, identical platforms systematically advantage well-capitalized users while simultaneously constraining resource-limited users. Environmental justice scholarship shows how green policies exacerbate inequalities when ignoring power differences [

87]. Digital aging policies risk the same outcome.

This relates to SDG 10 regarding reduced inequalities. Cognitive stratification reveals that digital participation can increase exclusion. Low-capital groups often blame themselves. Therefore, education must shift from teaching operational skills to improving cognitive abilities. This involves expanding digital literacy to include critical analysis of persuasive designs along with personalized support.

Finally, achieving SDG 17 requires cross-sector collaboration. The balance of responsibility must shift from users to platforms. Technology companies cannot solve these problems alone but must be held accountable. Governments should mandate age-appropriate evaluations and make algorithms easier to understand. We recommend banning addictive designs to correct power imbalances. The core transformation requires shifting from adapting the elderly to digital society to adapting digital society to diverse elderly populations. This ensures technological participation enhances long-term well-being.

6. Conclusions

This study challenges the pathologizing view of older adults’ intensive smartphone use, arguing that it is a rational adaptation to structural deficits rather than addictive dysfunction, and draws on in-depth interviews with urban Chinese older adults to explore how institutional arrangements drive such use, platform affordances provide contextual compensation, and these processes yield paradoxical outcomes moderated by cultural capital.

6.1. Key Findings

Four institutional shortfalls act as primary drivers: migration policies lead to family separation, mandatory retirement results in role loss, educational expansion devalues experiential knowledge, and ageist urban design fosters spatial exclusion. Together, these factors encourage older adults to turn to digital platforms for compensation.

Platforms, in turn, offer compensatory resources through a matching function to meet needs. They provide parasocial relationships to ease loneliness, validation for devalued skills, and tools that restore a sense of autonomy. However, this digital compensation is a double-edged sword. While it expands capabilities in areas like health management and mobility, it also creates new dependencies. These adverse outcomes include health deterioration, psychological distress, and vulnerability to financial fraud.

Critically, cultural capital emerges as the key stratifying variable that shapes these outcomes. Participants with higher cultural capital strategically utilized multiple platforms and attributed problems to external factors, such as flawed design or poor regulation. This protected their well-being and created potential for collective action. In contrast, those with lower cultural capital tended to rely on a single platform and internalize difficulties as personal failings. This self-blame intensified their vulnerability and prevented them from seeking collective solutions, thus perpetuating a cycle of digital disadvantage.

Based on these findings, we propose the Digital Compensation Framework to explain how older adults use technology in response to structural constraints. This framework redefines the Push–Pull–Mooring theory and clarifies the critical role of cultural capital in shaping whether digital engagement leads to empowerment or deepens social inequalities. By addressing structural roots of digital inequality in aging populations, this framework directly advances UN SDGs for health (SDG 3), industry (SDG 9), reduced inequality (SDG 10), and partnerships (SDG 17).

6.2. Limitations and Future Directions

This study also presents several limitations that inform subsequent inquiries: The analysis is constrained by its reliance on a cohort of intensive smartphone users within urban Chinese populations, thereby limiting the generalizability of findings to rural demographics or disparate cultural milieus. Cross-sectional investigations across heterogeneous environments would be requisite to validate the reproducibility of these observations in alternative contexts. Second, the cross-sectional methodology impedes causal determination, which calls for more longitudinal studies. Third, the qualitative assumptions require validation via large-scale structural equation modeling, and the absence of interventional studies calls for quasi-experimental designs contrasting behavioral and structural interventions. Furthermore, this paper champions a paradigm shift in digital gerontology by emphasizing the adaptation of technology and institutions to aging populations, reconceptualizing the digital divide as a manifestation of power dynamics rather than mere skill deficits and prioritizing systemic equity over individual behavioral adjustments. Interdisciplinary discourse is crucial for cultivating digital futures centered on well-being.