1.1. Background

Since China’s opening-up in 1978, rapid economic growth has been accompanied by pronounced environmental pressures and sizable cross-regional differences in air quality. Air pollution worsens residents’ quality of life, raises infant mortality, and dampens business activity [

1]. Despite major efforts by the Chinese government to improve air quality, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment’s Report on National Air Quality in 2023 indicates that more than 40% of cities still fail to meet air quality standards. Moreover, with extreme weather events occurring more frequently, the share of areas facing severe environmental pollution has trended upward in recent years. Over the same period, China’s labor income has risen modestly since 2007 but remains below levels in advanced economies and below the global average [

2]. Other studies further indicate that China faces severe income inequality and imbalances in wealth distribution [

3]. Our study provides new micro-level evidence on an environmental channel that helps explain China’s slow growth in labor income and persistent distributional inequality.

We focus on a basic question: who bears the cost of air pollution? The adverse health effects of pollution have received wide attention in the literature [

4]. Deteriorating air quality leads to numerous health problems, including respiratory infections, cardiovascular disease, and lung cancer [

5]. Air pollution is considered a major environmental hazard for human health, affecting not only physical but also psychological, cognitive, and emotional well-being; elevated risks of anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline attest to this [

6,

7]. Beyond direct health effects, air pollution is linked to a broad range of economic activities [

8]. Evidence suggests that higher pollution can worsen mood or heighten risk aversion, distorting subjective probabilities of future events and reducing demand for risky assets [

9,

10]. Conversely, better weather conditions are associated with more optimistic sentiment and increased financial activity [

11,

12].

We begin by proposing an optimal compensation-contract model with uncertainty. When air pollution reduces firms’ marginal product and increases earnings volatility, total labor income at the firm level declines. Risk-averse firms tend to lower the intensity of risk-sensitive executive incentives (equity and performance pay) and concomitantly cut executive cash compensation to curb cash outlays [

13]. By contrast, nominal wages for rank-and-file employees are constrained by institutional factors such as minimum-wage rules and collective bargaining; firms therefore adjust more on the employment margin—particularly the number of low-skill workers—to compress the overall wage bill [

14].

1.2. Research Hypothesis

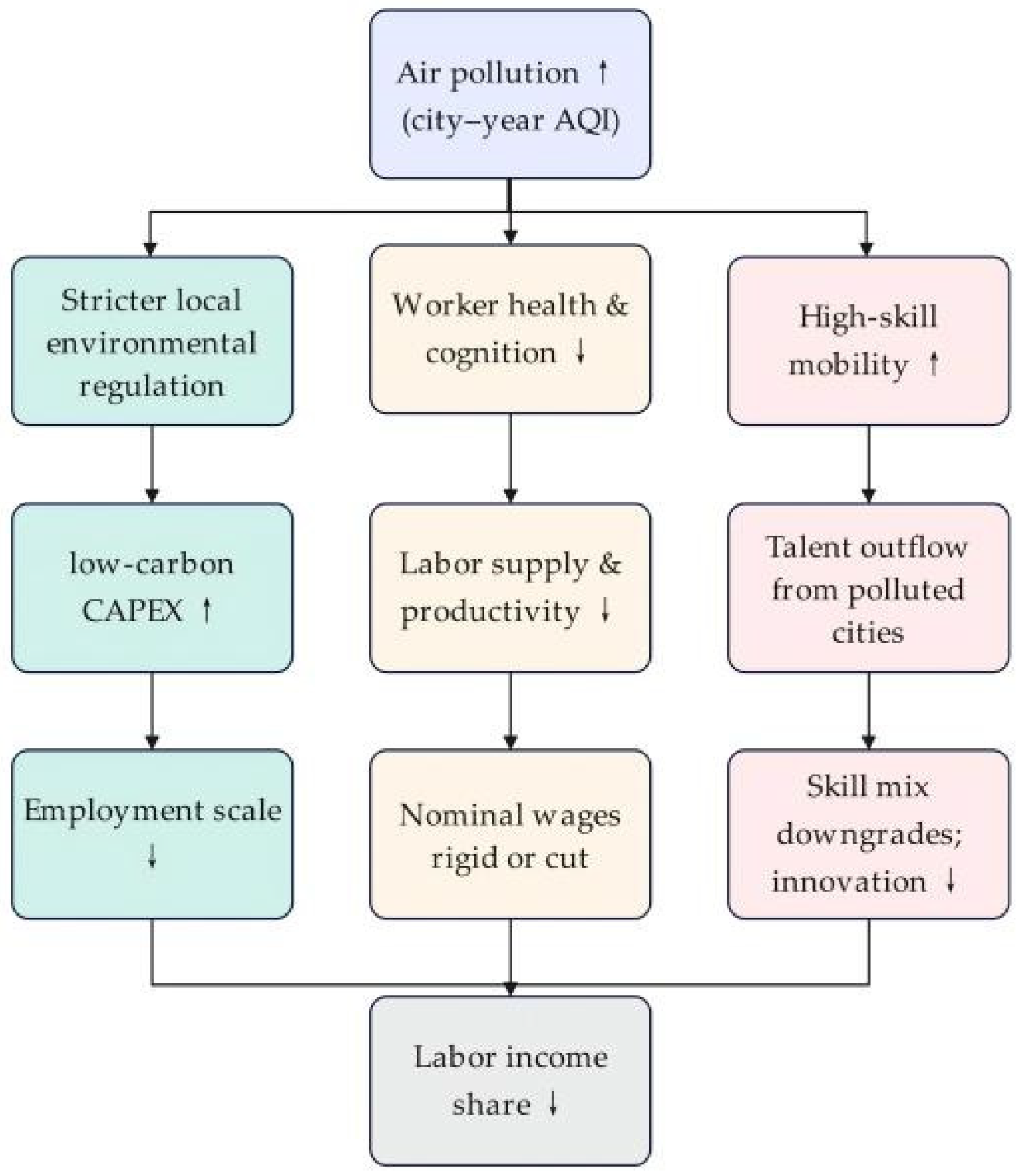

Air pollution has certain negative externalities, adversely affecting the input of production factors and the quality of the production environment. In areas with more severe air pollution, firms face stricter environmental regulations from local governments. These government regulations compel firms to allocate part of their output to the purchase of green and low-carbon equipment or to adopt stricter emission reduction measures [

15]. Consequently, companies must invest more in green capital to combat pollution, which undoubtedly increases their operational costs. To ensure maximization of profits, firms may reduce the scale of employment in the short term to cope with rising production costs. The crowding-out effect of production factors leads to a decline in labor share within firms.

Moreover, air pollution also impacts employees’ productive activities. On one hand, air pollution can severely damage employees’ cognitive abilities and physical health. Employees may choose to reduce their labor supply and lower their productivity during periods of high air pollution, especially in outdoor occupations. Additionally, employees who commute long distances might opt for remote work or take leave to avoid the hazards of air pollution during their commute, which would also decrease the labor supply and reduce employee income. On the other hand, in China, employees are typically at a disadvantage in wage negotiations [

16], leading companies facing continually declining labor productivity to often reduce wages to decrease costs. This undeniably has a negative impact on the labor share (

Figure 1).

Incontestably, air pollution is becoming an increasingly critical factor influencing the occupational decisions of the labor force [

17]. Prolonged exposure to significant air pollution levels elevates the risk of developing respiratory ailments and lung cancer among workers. Meanwhile, air pollution also profoundly affects employees’ families, particularly impacting the elderly and children more adversely than adults [

18].

As the market economy rapidly develops and barriers to labor mobility decrease, employees are increasingly moving to areas with lower air pollution to reduce its risks. Employees with higher education and technical skills, who face lower mobility costs and have greater advantages in the job market, are more likely to relocate to cities with better air quality in response to pollution’s adverse effects [

19]. These employees are more concerned about how air pollution impacts their health, which gives them greater mobility. As a result, air pollution’s brain drain effect is stronger in companies with higher levels of human capital [

20,

21]. The loss of high-skilled talent, which is crucial for a company’s human capital, leads to a reduction in labor income share. A formal analysis of the underlying mechanism is provided in the

Supplementary Materials.

1.3. Main Findings and Contributions

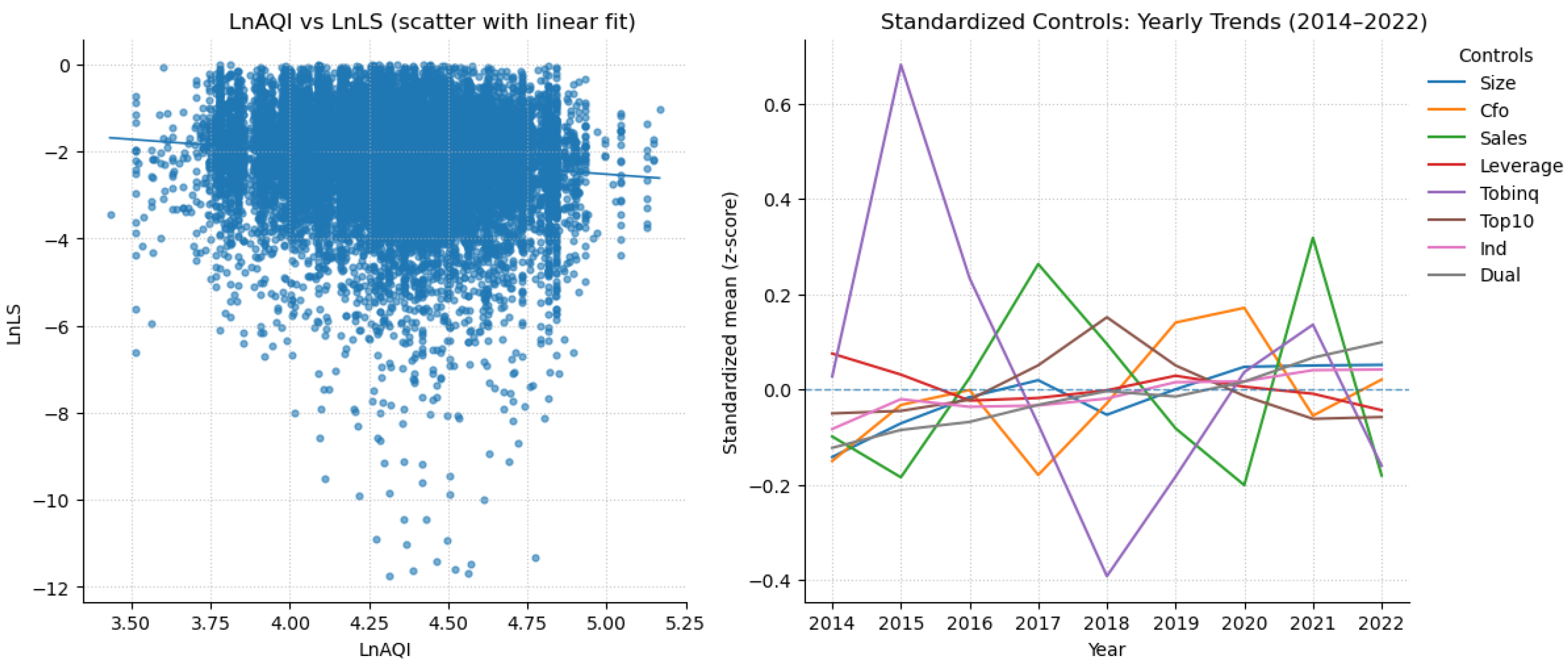

We measure air quality by the average concentrations of six pollutants, including common measures such as PM2.5 and CO. Air-pollution data come from ground monitoring stations that have been built out since 2012 to cover China’s major prefecture-level cities. We aggregate daily city-station readings into annual averages to construct a city–year measure of pollution intensity. Listed firms are mapped to cities based on their registered location or principal place of business, and firm-year financials are obtained from annual reports. We define a firm’s labor income share as the ratio of employee compensation to output. To account for unobserved factors affecting labor income, our baseline identification includes industry and year fixed effects. Using the Air Quality Index (AQI) available since 2013, we find that firms located in regions with worse air quality exhibit significantly lower labor income within the firm. Quantitatively, a 1% increase in air pollution is associated with a 0.37% decline in firm-level labor income.

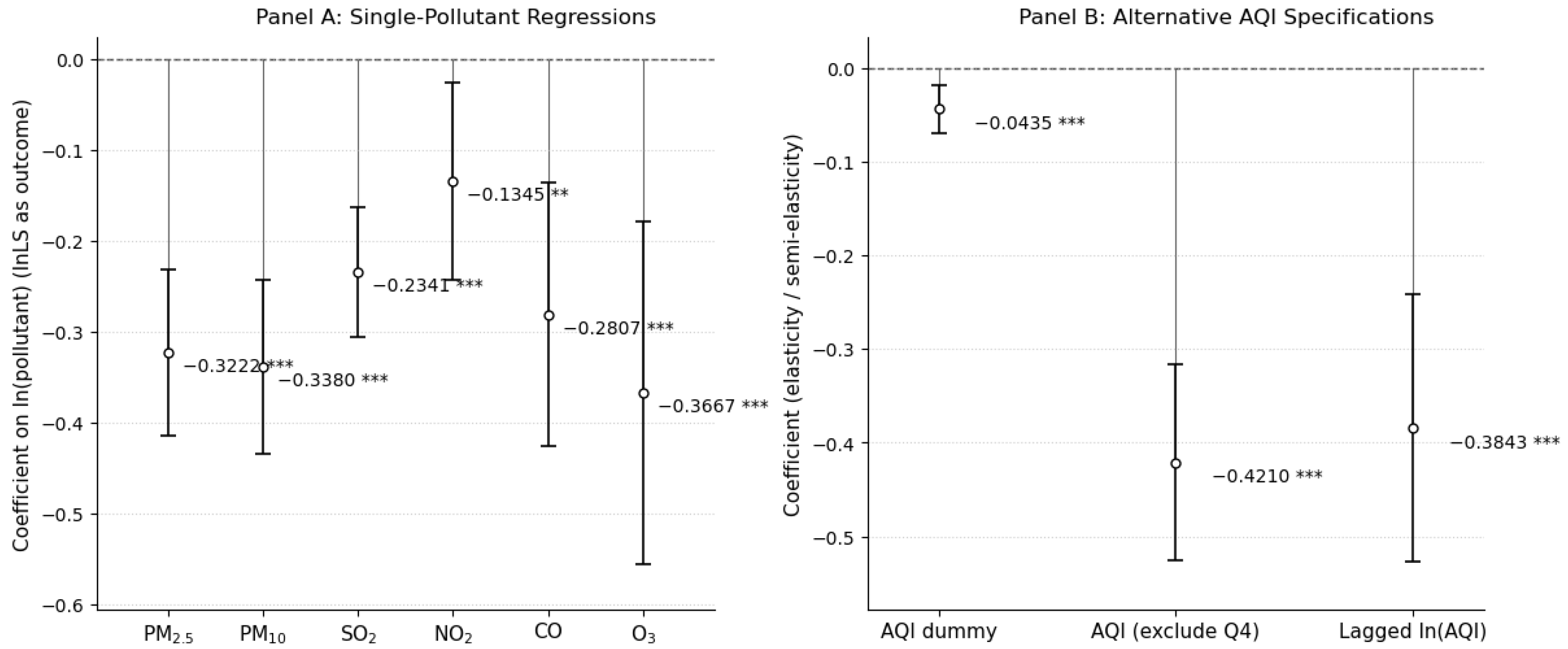

We evaluate several threats to identification. First, our AQI measure may not fully capture true pollution. Replacing AQI with annual averages of single pollutants (PM

2.

5, PM

10, SO

2, NO

2, CO, O

3) leaves the core results unchanged. Among these, O

3 shows the largest negative effect on labor income, followed by PM

10. Second, results may be sensitive to the sample period. Splitting the sample at 2017 yields no meaningful change in significance, and controlling for time trends produces consistent conclusions. Third, findings could be driven by specific cities. Excluding highly polluted regions and the large metropolitan areas of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen does not alter the results. Fourth, estimation concerns remain. We introduce stricter city fixed effects and adjust clustering to the industry-year and city-year levels to account for error correlation. Fifth, measurement of labor income may not perfectly reflect employees’ actual earnings. In

Section 3.2.4., we redefine firm labor income and standardize it by industry-year means; the overall evidence confirms the robustness of our baseline identification.

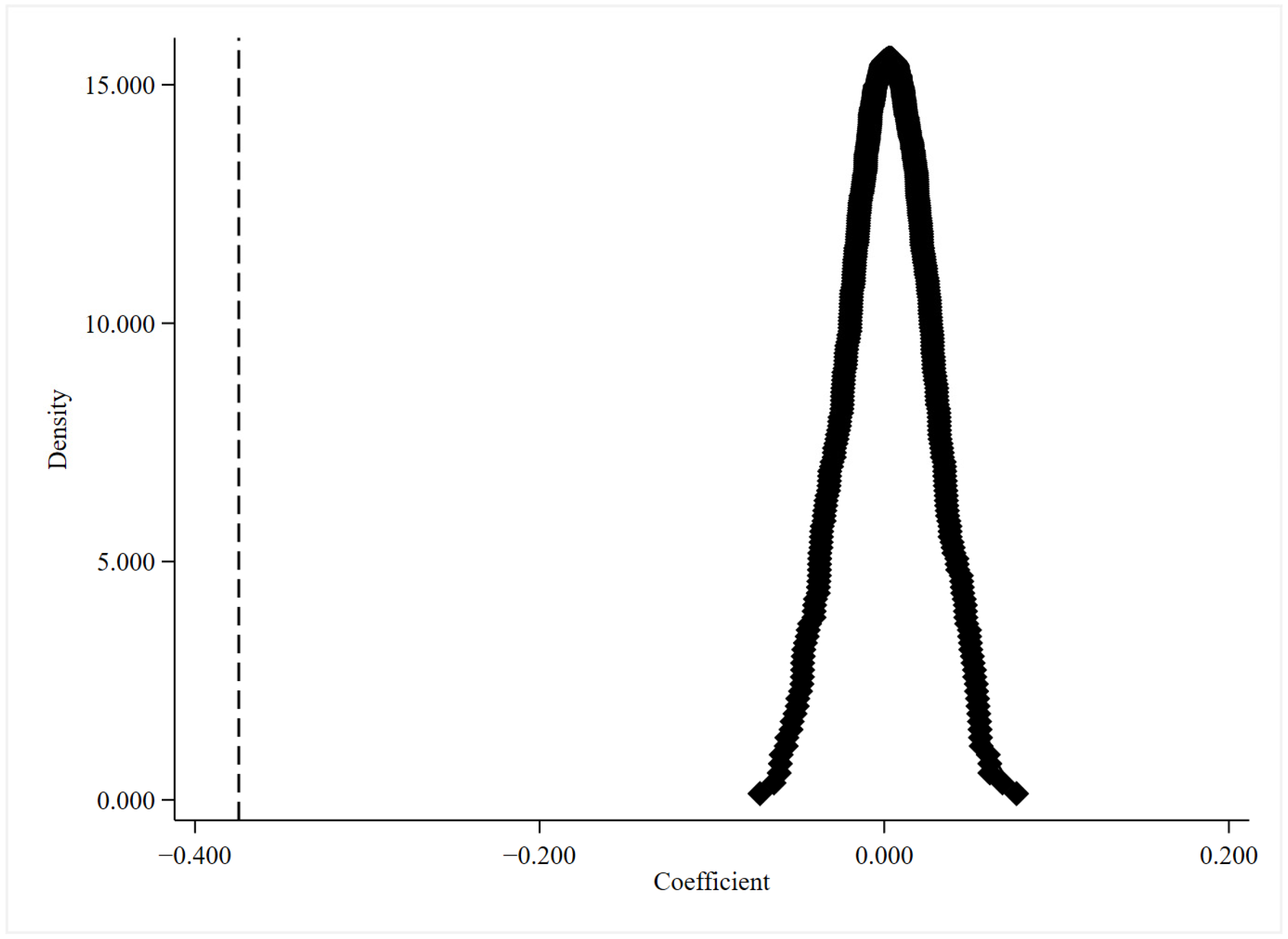

Causal identification may still face reverse-causality and omitted-variable concerns. First, firms’ compensation structures and profit-sharing schemes could shape environmental investment and emissions, thereby feeding back into local pollution levels. Second, regional differences in economic structure or policy could jointly affect pollution and labor income, introducing omitted-variable bias. To mitigate endogeneity, we use thermal inversion days as an instrumental variable. Typically, atmospheric temperature decreases with altitude, and the resulting convection disperses pollutants, lowering pollution levels. During thermal inversions, however, temperature rises with altitude, suppressing convection and trapping pollutants, thereby intensifying pollution. Inversion strength is, in theory, determined by complex meteorological systems and is exogenous to firm-level outcomes. Hence, using inversion strength as an instrument satisfies both relevance and exogeneity. Two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimates indicate that a 1% increase in air pollution reduces firm labor income by 0.74%, roughly twice the OLS estimate.

We use “spurious equality” to denote a decline in within-firm pay dispersion that is driven by disproportionate cuts at the top under pollution-induced uncertainty, while rank-and-file wages remain bound by downward nominal rigidity. This compression does not reflect welfare gains for lower-paid workers and is typically accompanied by employment adjustments and weaker innovation. This differs from “transitory equality,” a short-lived, symmetric and reversible compression that fades as temporary shocks dissipate, and from “artificial reduction of inequality,” a compression created by accounting or policy devices rather than real risk and cash-flow constraints. The stability of labor income is a key concern for policymakers, as it reflects distributive fairness and strongly influences long-term social stability and sustainable growth. Since disposable household income is primarily composed of labor income, a declining labor share threatens social equity, justice, and political stability [

22]. We document the economic consequences of reduced firm labor income. Treating pollution-induced changes in labor income as an exogenous driver, we find that firms’ human-capital structures and innovative activity deteriorate significantly: the share of highly educated employees (bachelor’s degree or above) declines, the share of low-skill workers (below high school) rises, and both total patents and invention patents fall.

We further examine within-firm labor income distribution and show that air pollution compresses internal pay gaps through “larger cuts at the top”. Executive cash and equity compensation both decline significantly, while employees’ nominal pay is broadly insensitive. After standardizing compensation within industries, pollution significantly lowers the executive pay premium but does not affect the employee pay premium, resulting in a narrower premium gap. Moreover, in firms with higher stock-price volatility, the suppressing effect of pollution on equity-based pay is stronger; the negative impact on executive cash pay is somewhat attenuated but remains negative overall, consistent with the basic rigidity of nominal employee wages.

Our contributions are threefold. First, we add to research on how air pollution affects firms’ human capital. Prior work shows that improved air quality stabilizes labor supply and raises productivity [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27], while pollution increases absenteeism and sick leave and reduces the efficiency of human-capital utilization [

28,

29]. Direct evidence on how pollution shapes human capital within firms remains scarce. By analyzing a factor that has received limited attention—air pollution’s impact on firm-level labor income shares—we extend the discussion of the declining labor share. Second, we broaden the study of the economic consequences of a falling labor share. Our empirical results document a talent-loss effect—pollution leads to outflows of high-skill labor—and we show a further consequence: reduced innovation output. Third, we contribute to the literature on income distribution between executives and employees.

Our findings speak directly to the sustainability agenda by identifying a firm-level channel through which degraded air quality undermines decent work (via pay compression and wage rigidity), inclusive growth (through a falling labor share and widening distributional risks), and innovative capacity (via talent outflows and reduced high-quality patents). These mechanisms are not specific to China’s institutional setting: urbanization, transboundary pollution, and exposure to episodic shocks (e.g., thermal inversions, wildfires, dust storms) are common across both advanced and emerging economies. The link we document between environmental quality, wage-setting under risk, and human-capital allocation thus has broad applicability and policy salience. It also complements climate and air-pollution co-benefit strategies by showing that cleaner air can help preserve the labor share and sustain innovation during green transitions. Taken together, the results provide micro-level evidence to inform integrated policies that combine environmental regulation with labor-market and innovation policies in support of a just and sustainable transition worldwide.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 (“Material and Method”) describes data sources, variable construction, and our hypotheses.

Section 3 provides empirical evidence on the effects of air pollution on firm-level labor income shares, including baseline results, robustness checks, endogeneity analyses, and cross-sectional heterogeneity.

Section 4 delves into within-firm labor income distribution.

Section 5 concludes.