1. Introduction

Nature connectedness reflects an individual’s enduring sense of inclusion of nature in the self and an affective connection to the natural environment [

1,

2,

3]. Extensive evidence indicates that higher levels of nature connectedness are associated with improved mental health, enhanced subjective well-being, and stronger engagement in environmentally protective behaviors [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Additionally, a growing body of scholarly work has highlighted the significance of prosociality. Prosociality, encompassing actions, dispositions, and values oriented toward the welfare and benefit of others, constitutes a fundamental dimension of human social functioning [

8,

9]. Prosociality is not only a key indicator of positive individual development and adaptive functioning, but also facilitates interpersonal harmony and intergroup integration, as well as broader social cohesion, collective resilience, and societal well-being [

10].

Although these constructs have often been studied in isolation, emerging theoretical and empirical perspectives suggest they may be psychologically intertwined. Nature connectedness may broaden moral concern and foster empathy, and prosocial dispositions may, in turn, increase sensitivity to the natural world, creating a mutually reinforcing cycle of concern for nature and other people [

11,

12]. The integration of concern for nature and others may constitute a moral foundation for communities oriented toward ecological and social well-being [

13,

14]. Specifically, in the face of escalating socio-ecological crises, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and social fragmentation [

15,

16], examining how psychological connection to nature relates to prosocial orientations toward humans offers critical insights into building sustainable societies.

1.1. Nature Connectedness

Although often used interchangeably, nature exposure, nature relatedness, and nature connectedness represent distinct but interrelated constructs. Nature exposure refers to the objective or behavioral experience of being in natural environments, encompassing both the frequency and duration of contact with nature (e.g., time spent outdoors or participation in nature-based activities, [

17]). Nature relatedness, is a trait-like construct describing an individual’s stable and affective sense of connectedness with the natural world [

2]. It extends beyond mere environmental activism or an appreciation for beautiful scenery, encompassing a deep understanding and appreciation of our interconnectedness with all living things. Nature connectedness is conceptually narrower yet more integrative—it captures the subjective sense of oneness and emotional attachment to nature, combining cognitive, affective, and behavioral components that shape both immediate experiences in nature and enduring pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors [

18].

The cognitive dimension of nature connectedness involves the inclusion of nature within the self-concept, such that individuals perceive themselves as inherently linked to the natural world, which shapes environmental attitudes and moral concern for ecological systems [

3]. The emotional dimension reflects affective affinity toward nonhuman life, including feelings of care, empathy, and concern for animals, plants, and ecosystems, which motivate pro-environmental intentions and behaviors [

1,

19]. The behavioral dimension captures individuals’ tendencies to engage in actions demonstrating engagement with and responsibility for the natural environment, such as conservation efforts, sustainable practices, or participation in ecological activities, which both express and reinforce underlying cognitive and emotional connections [

2,

20].

A substantial body of research has documented the benefits of nature connectedness for both individual functioning and broader ecological outcomes. Individuals high in nature connectedness consistently report greater psychological well-being, including enhanced vitality, life satisfaction, and reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms [

4,

5,

21]. These psychological benefits are theorized to arise from a strengthened sense of belonging to a larger ecological whole and a more coherent self-concept, which together facilitate attentional restoration and support adaptive emotional regulation [

3,

22]. Furthermore, nature connectedness is a robust predictor of environmentally protective behaviors, such as conservation efforts, sustainable consumption, and ecological citizenship [

6,

7]. This relationship is underpinned by an expanded sense of moral inclusion and empathic concern for nonhuman life, whereby recognition of ecological interdependence motivates actions aimed at preserving environmental integrity.

Although nature connectedness exhibits trait-like stability, it is also sensitive to developmental, cultural, and situational influences, highlighting its potential for growth across the lifespan. Developmental research shows that the foundational predisposition for an ecological-moral sense appears early in ontogeny [

23], and this early-emerging sensitivity becomes more robust and complex with age [

24]. Early exposure to natural environments, immersive outdoor experiences, and educational programs that emphasize ecological knowledge and emotional engagement with the natural world have all been shown to strengthen individuals’ connection to nature [

25,

26]. Reflective practices, such as mindfulness in natural settings or exercises encouraging recognition of humans’ interdependence with ecological systems, can further reinforce affective and cognitive components of nature connectedness, promoting enduring pro-environmental attitudes [

11]. The malleability of nature connectedness suggests that targeted interventions, ranging from educational programs to structured nature experiences, can foster stronger connections to the natural world, supporting both individual flourishing and responsible environmental engagement.

1.2. Prosociality

Prosociality comprises behavioral, dispositional, and value-based dimensions that jointly account for individual differences in concern for others [

27,

28,

29]. Prosocial behavior comprises voluntary actions intended to benefit others, such as helping, sharing, cooperating, and comforting [

10]. Beyond observable actions, prosociality is characterized by enduring individual traits that predispose people toward other-oriented behavior, including the capacity for empathy and perspective-taking [

30,

31], as well as broader dimensions of personality such as agreeableness and honesty–humility [

32,

33]. Traits reflect what people are like, while values express what people consider important and desirable [

34]. Prosocial values, such as self-transcending values of universalism and benevolence, represent a deliberate prioritization of the welfare of others and the collective, guiding moral reasoning, shaping long-term goals, and sustaining prosocial actions even in the absence of immediate interpersonal cues or external incentives [

35,

36,

37].

These three facets of prosociality are mutually connected, jointly contributing to the expression of prosocial tendencies. Prosocial traits and values provide relatively stable psychological foundations that help explain interindividual differences and intraindividual consistency in prosocial behaviors [

27,

38,

39]. For instance, prosocial decisions in the Dictator Game and Trust Game capture a general cooperative disposition rather than merely shared situational features [

40]; trait gratitude likewise predicts greater generosity and trust in both charitable donation tasks and incentivized trust games [

41]. Beyond their influences on behavior, prosocial traits and values also shape one another. Although traits are primarily conceptualized as having a biological basis and values are understood to be shaped to a greater extent by environmental and cultural influences [

42], they do not operate independently. Instead, they engage in a dynamic, reciprocal relationship: innate predispositions can influence the endorsement of particular values [

43,

44], and internalized values can, in turn, become integral components of the personality structure [

45,

46].

While prosocial behavior, traits, and values are interrelated, the mere presence of one component does not guarantee another. For instance, prosocial acts can reflect strategic reputation management rather than genuine altruism [

47,

48]; moral judgment often fails to translate into action due to a preference for moral hypocrisy, the motivation to appear moral while avoiding the cost of actually being moral [

49]; and robust empathic tendencies may be overridden by competing self-enhancing or materialistic values [

50]. Therefore, mature and sustained prosociality requires the integration of these elements into a coherent self-system. Through this process, being a prosocial person becomes central to one’s identity and self-concept [

51,

52], shifting motivation from instrumental or socially pressured compliance to self-determined enactment rooted in a need for self-consistency and felt responsibility [

53,

54]. This self-determined motivation fosters a genuine concern for the welfare of people, the environment, and society, leading to consistent and autonomous prosocial action across contexts without reliance on external incentives or cost–benefit calculations.

1.3. The Link Between Nature Connectedness and Prosociality

Although often examined separately, both prosociality and nature connectedness may be expressions of a broader psychological orientation: an expansive moral concern, or moral expansiveness, reflecting the degree to which individuals extend moral regard beyond the self to a wide range of human and nonhuman entities [

55]. This generalized capacity for care has deep evolutionary roots, most notably articulated in the biophilia hypothesis [

56,

57], which posits that human adaptive success depended not only on intra-group cooperation but also on an innate sensitivity to ecological systems. This evolutionary framework suggests that the adaptive disposition to care for the natural world (biophilia) and the capacity for care toward conspecifics likely co-evolved, sharing and reinforcing common neurobiological and psychological substrates, such as the neural circuits for attachment, care, and empathy. Extending this view, contemporary research has begun to delineate the psychological processes through which nature connectedness and prosociality mutually reinforce each other.

Nature connectedness facilitates prosociality through two distinct yet complementary mediating pathways. Firstly, nature connectedness reduces physiological stress (e.g., lower cortisol levels) and restores depleted cognitive and emotional resources (e.g., executive function, emotional regulation), which is necessary for attending to and investing in the welfare of others [

4,

21]. Beyond restoration, nature connectedness frequently elicits self-transcendent emotions such as awe, wonder, and humility, which shift focus away from the self and toward larger entities and collective concerns [

58,

59]. This self-transcendence involves an expansion of self-boundaries interpersonally, temporally, and transpersonally, fostering a heightened sense of connection to something larger than oneself [

60,

61]. By reducing self-focus and enhancing felt connection to the broader world, transcendence enables individuals to overcome the egoistic constraints that often inhibit prosocial action, thereby promoting empathy, compassion, and willingness to act for the benefit of others beyond immediate social circles [

62].

From the perspective of Self-Determination Theory [

63], these restorative and transcendental experiences jointly fulfill the basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Restorative effects reduce external pressures and cognitive fatigue, thereby enhancing the sense of autonomy and competence in one’s capacity to act. Self-transcendent experiences, in turn, strengthen the sense of relatedness—feeling connected to others and to the larger web of life. When these needs are satisfied, individuals experience an intrinsic motivation to engage in prosocial behavior, not out of obligation or social expectation but as an authentic expression of an integrated self. In this way, nature connectedness nurtures the internal motivational foundation that sustains prosocial tendencies over time.

Prosociality may also foster a deeper sense of connection with the natural world. At its core, prosociality is grounded in care, a genuine concern for others that transcends external expectations or immediate social obligations. Empathy and perspective-taking, the psychological foundation of care, facilitate recognition of ecological interdependence and broaden the boundaries of moral regard to encompass nonhuman entities [

64]. Longitudinal evidence has demonstrated that general caring and concern for future generations (generativity) predict sustained engagement in environmental actions years later [

65]. These findings suggest that prosocial orientations may cultivate stronger bonds with the natural world, highlighting the reciprocal nature of prosociality and nature connectedness as interconnected dimensions of a broader ethic of care.

A growing body of empirical evidence generally supports a positive association between nature connectedness and prosociality, with reported correlation coefficients typically ranging from small to medium-large (e.g.,

r = 0.21 to 0.54) in studies that report significant effects. However, the literature is not entirely consistent. Some studies have observed non-significant relationships (e.g., [

66,

67]), and the magnitude of effects shows considerable heterogeneity. Such variability may stem from differences in sample characteristics, cultural contexts, and especially the measurement approaches used. Both nature connectedness and prosociality are multidimensional constructs, and measures emphasizing different facets may yield divergent results. These discrepancies underscore the need for a quantitative synthesis. To date, meta-analytic work on this topic has largely operationalized prosociality in terms of pro-environmental behaviors (e.g., [

6,

7]). While environmental behaviors can indeed be considered a form of prosocial action, they do not capture prosociality directed toward human beneficiaries. Thus, a pivotal, yet unresolved theoretical question is whether the morality underpinning nature connectedness is domain-specific—concerned solely with the environment—or an expression of a broader moral orientation. If nature connectedness is part of a generalized moral expansiveness [

55], it should correlate not only with pro-environmental behaviors but also with prosociality directed at other people. By quantitatively synthesizing the association between nature connectedness and human-directed prosociality, it thereby sheds new light on the ongoing theoretical discussion regarding the structure of morality itself.

1.4. The Current Study

While the environmental benefits of nature connectedness are well documented, its potential to promote human-directed prosociality remains underexplored. Building on this gap, the present research conducts the first comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between nature connectedness and prosociality. Specifically, this meta-analysis pursues two main aims. First, it seeks to estimate the overall strength of the association between nature connectedness and prosociality across studies. Based on prior evidence, we hypothesize a positive association between the two constructs (H1). Second, it investigates potential moderators that may account for the heterogeneity of findings, including sample characteristics (e.g., age, gender, cultural context) and measurement features (e.g., dimensions of nature connectedness and prosociality assessed). Given the limited empirical evidence, these moderator analyses are posed as exploratory research questions.

By addressing these aims, this study provides a more precise estimate of the relationship between nature connectedness and prosociality, clarifies sources of inconsistency in the literature, and extends previous meta-analytic work by examining human-directed prosociality. Together, these contributions advance the understanding of the psychological foundations of an expansive moral concern that bridges social and ecological domains.

2. Materials and Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines [

68], with the PRISMA 2020 checklist included in the

Supplementary Materials. The review protocol was not preregistered.

2.1. Research Strategy

We conducted a comprehensive literature search up to August 2025 in five electronic databases: Web of Science, PsycInfo, Scopus, ScienceDirect, and ProQuest. Search terms combined concepts related to nature connectedness (including “nature connectedness,” “connection to nature,” “nature relatedness,” “inclusion of nature in self,” and “environmental identity”) with those related to prosociality (including “prosocial,” “altruism,” “cooperation,” “kindness,” and “volunteering”). Database-specific syntax was applied to accommodate the requirements of each database. We did not apply any restrictions on publication year, allowing us to capture a diverse range of studies. In addition to database searching, we examined the reference lists of all included articles and relevant reviews to identify additional eligible studies. Furthermore, to reduce the risk of publication bias, we issued a call for unpublished data by contacting prominent researchers in the field via the forum and mailing listservs of Division 34 (Society for Environmental, Population, and Conservation Psychology) of the American Psychological Association and the Society for Personality and Social Psychology.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In the present meta-analysis, we conceptualized natural connectedness as a relatively stable, trait-like individual difference reflecting the extent to which individuals include nature as part of their self-concept and experience a subjective sense of connection with the natural world. Accordingly, only explicit self-report trait measures of identification with or connection to nature were included. In contrast, state-based measures of momentary connection with nature (e.g., fluctuations across contexts or experimental manipulations) and studies relying solely on parent- or teacher-reports were excluded to ensure conceptual clarity and commensurability across studies.

Prosociality was defined as actions, values, or stable dispositions aimed at benefiting others or society. Although altruistic environmental concern (i.e., concern about environmental problems due to their potential negative consequences for other people) can be construed as an altruistic value, such measures are embedded within environmental attitudes rather than general prosociality toward humans or society, and were therefore excluded. Likewise, to maintain conceptual clarity and avoid overlap with existing meta-analyses on nature connectedness and pro-environmental outcomes, studies that measured only individual-level pro-environmental actions (e.g., recycling, sustainable transportation, reduced meat consumption, green purchasing) were excluded. However, conservation-related volunteering was retained when it reflected broader community or civic engagement (e.g., environmental stewardship embedded within social, educational, or communal activities) rather than solely individual ecological actions.

Studies were eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (a) employed at least one measure of nature connectedness and at least one measure of prosociality; (b) reported a statistical relationship between nature connectedness and prosociality; and (c) provided sufficient information to compute an effect size and its variance (e.g., correlation coefficient and sample size).

All study designs were considered; however, experimental studies were included only if they reported a baseline measure of the relationship between nature connectedness and prosociality, prior to any experimental manipulation. All age groups were included as eligible samples because there was no theoretical or practical reason to exclude any particular group. For the same reason, no exclusions were made based on the country where the study was conducted or the time when it was conducted. Both published and unpublished studies were eligible for inclusion. Studies published in languages other than English were excluded. Qualitative studies, the literature reviews, theoretical papers, and other non-empirical works were also excluded. Studies that did not report adequate statistical information to compute an effect size were excluded unless such data could be obtained directly from the study authors.

Consistent with common practice in systematic reviews [

69], we considered study validity during screening. The methodological quality of the included studies was generally high based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal criteria. The majority of studies satisfactorily met the standards for participant inclusion, sample description, and measurement properties. Although some studies presented minor limitations, such as incomplete reporting of sample demographics, none contained shortcomings serious enough to undermine the validity of their overall findings.

The initial screening of studies was carried out independently by two researchers trained in environmental and social psychology. Each rater applied the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine whether a study qualified for the meta-analysis. Interrater reliability for eligibility decisions was high (Cohen’s κ = 0.87), which, according to the benchmarks proposed by Landis and Koch [

70], reflects almost perfect agreement. Most disagreements arose from the difficulty of distinguishing prosociality measures from conceptually related pro-environmental outcomes. These discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached, and the final set of studies was jointly confirmed for inclusion.

2.3. Coding Procedure

Two independent raters coded all studies included in the meta-analysis using a standardized coding form. The form captured information on (1) sample size, (2) sample type (e.g., students, community, or mixed), (3) age distribution and mean age, (4) gender distribution (percentage of female participants), (5) country in which the study was conducted, (6) type of publication (e.g., journal article, dissertation, or book chapter), (7) the effect size (correlation coefficient

r) for the association between natural connectedness and prosociality, (8) the scales or instruments used to measure natural connectedness, and (9) the scales or instruments used to measure prosociality. Interrater reliability was high, with absolute intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) ranging from 0.98 to 1.0 for continuous variables and Cohen’s Kappa values ranging from 0.83 to 1.0 for categorical variables, indicating substantial to almost perfect agreement [

70]. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Correlation coefficients were used as the effect size to quantify the relationship between nature connectedness and prosociality. To remove intrastudy bias, only one measure per construct was retained. For natural connectedness, multi-item trait scales with high reliability and broad conceptual coverage (e.g., Connectedness to Nature Scale) were prioritized over single-item indicators (e.g., Inclusion of Nature in Self). For prosociality, behavioral measures were prioritized when available. In their absence, validated prosocial behavior scales (e.g., Altruism Scale) were employed, and when such measures were not reported, related constructs (e.g., empathy, perspective-taking) were considered as proxies. All effect sizes were reported as correlation coefficients in the primary studies. Correlation coefficients were transformed to Fisher’s

Z values prior to meta-analysis to stabilize variance, especially as some correlations exceeded 0.30, and were converted back to

r for interpretation [

71].

Random-effects models were used to estimate the mean effect size, as variability in effect sizes across studies was expected due to differences in sample characteristics, measures, and contexts [

72]. Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q and I

2, with I

2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% interpreted as low, moderate, and high [

73]. Extreme effect sizes were identified based on Hanson and Bussière’s [

74] criteria, and analyses were conducted with and without potential outliers. The weight of studies with disproportionately large samples was adjusted to prevent them from dominating the results.

Potential publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots, Egger’s regression test, classic fail-safe N test, Orwin’s fail-safe N and Duval and Tweedie’s trim, ensuring that the meta-analytic findings were robust and not overly influenced by selective reporting of significant results. While advanced methods such as p-curve analysis could offer further insight, they could not be employed due to the inconsistent reporting of exact p values or test statistics across primary studies. Our assessment of publication bias was therefore reliant on Egger’s test and the trim-and-fill method, which represent a comprehensive approach given these constraints.

Moderator analyses were conducted using meta-regression and categorical subgroup analyses. Meta-regression was employed to examine the effects of continuous moderators, specifically the percentage of female participants and the mean age of each sample. For categorical moderators, we compared effect sizes across subgroups defined by (a) sample type, (b) geographic location of the sample, (c) nature connectedness scales, (d) dimensions of nature connectedness scales, (e) prosociality scales, and (f) dimensions of prosociality scales. Univariate subgroup analyses were performed to test whether effect sizes differed significantly across categories of each moderator.

3. Results

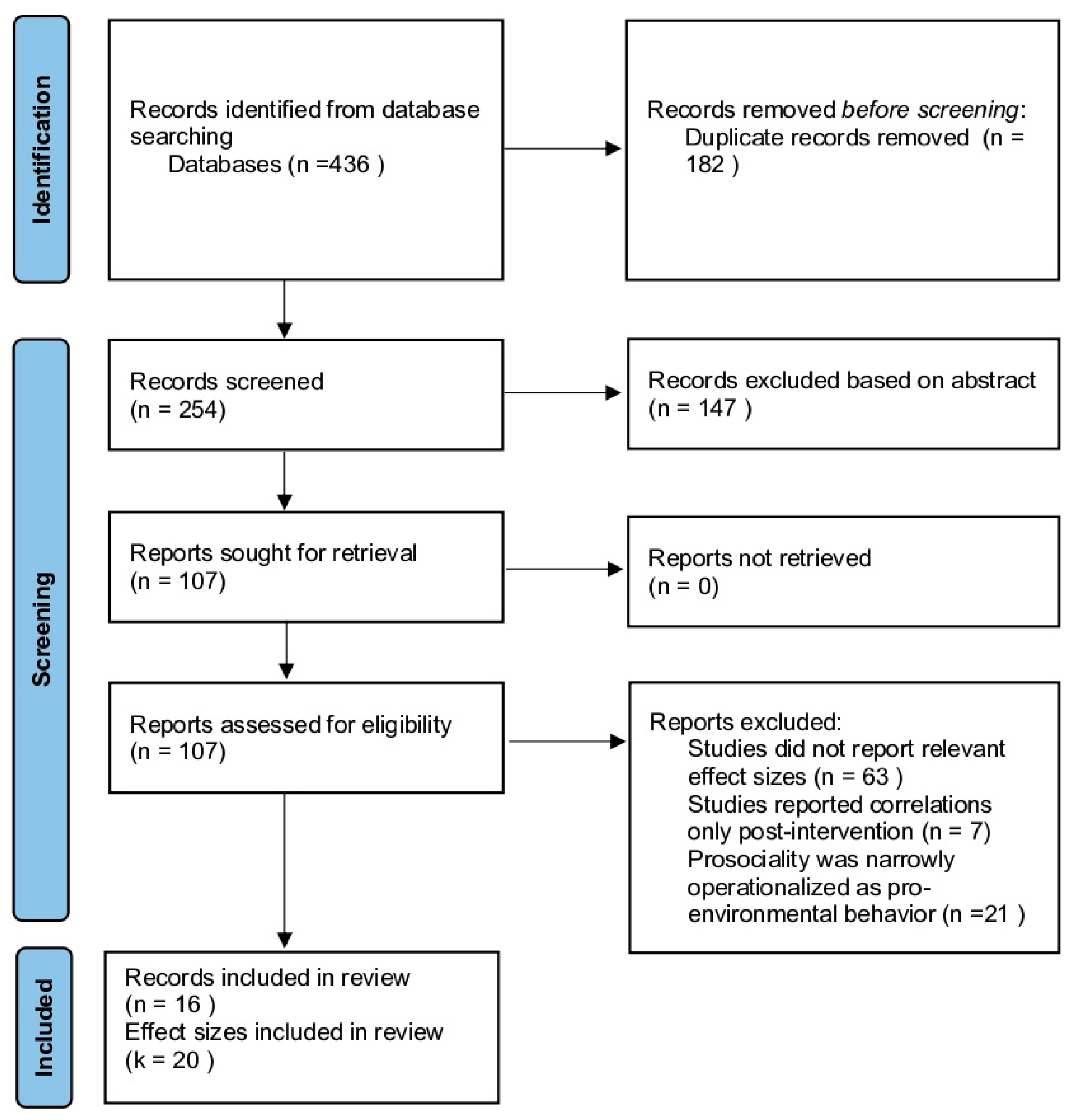

3.1. Study Selection

The literature search initially identified 436 records through database searches. After removing 182 duplicate records, 254 unique records were screened based on titles and abstracts. Of these, 147 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The remaining 107 reports were retrieved and assessed for eligibility through full-text review. No reports were excluded due to retrieval issues. Following eligibility assessment, 91 reports were excluded for the following reasons: (a) 63 did not report relevant effect sizes, (b) 7 reported correlations only post-intervention, and (c) 21 narrowly operationalized prosociality as pro-environmental behavior rather than human-directed prosociality. Ultimately, 16 reports comprising 20 independent studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. A detailed overview of the study selection process is presented in

Figure 1.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 shows the key characteristics of included studies. The publication years of the included studies ranged from 2004 to 2025. While a small number of early works were published between 2004 and 2014 (

n = 3), the vast majority of studies (

n = 13) have appeared in the past decade. Research activity has notably accelerated in recent years, with a concentration of publications between 2022 and 2025 (

n = 10), suggesting growing scholarly interest in the link between nature connectedness and prosociality.

The meta-analysis included a total of 16 studies (comprising 20 independent samples) with a cumulative sample size of 34,512 participants. Sample sizes varied widely, from a minimum of 102 to a maximum of 26,848 participants, with a median sample size of approximately 354. The proportion of female participants ranged from 44.4% to 79%, with an overall average of approximately 62.26%.

The overall age distribution across studies was broad, spanning from 11 to 89 years. Mean ages varied substantially, from 11.92 to 54.89 years. 9 samples used student populations, 9 samples used mixed or general population samples, and 2 samples were classified as community samples, consisting of non-student adult participants. Among the student samples, one study included participants aged 12–20 years, representing a school-based adolescent population.

Geographically, the studies were conducted in 13 different countries/regions. The distribution was as follows: the United States was the most represented (n = 7), followed by Australia (n = 3), and China (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), the UK (n = 1), Russia (n = 1), Chile and Mexico (combined sample, n = 1), Chile/Spain/Mexico/Guatemala (combined sample, n = 1), Germany (n = 1), and Turkey (n = 1). This distribution indicates a diverse but predominantly Western and English-speaking sample base.

3.3. Measures

Across the 20 included samples, nature connectedness was most commonly assessed with the Connectedness to Nature Scale [

1] (11 studies). Additional instruments comprised the Connection to Nature Scale adapted from [

75] (4 studies), the Inclusion of Nature in Self [

3] (2 studies), and single-study uses of the Nature Relatedness Scale [

2], a mixed short form combining items from the Connection to Nature Index [

76] and the Connectedness to Nature Scale [

1], and a study-developed measure inspired by Nature Contact Questionnaire [

77], Connectedness to Nature Scale [

1], and Brief Measure of Nature Relatedness [

78]. In this meta-analysis, these instruments were treated as conceptually convergent operationalizations of nature connectedness, as all capture the perceived psychological bond or inclusion of the natural world within the self. However, to account for potential measurement heterogeneity, the primary dimension emphasized by each instrument (cognitive, affective, or multidimensional) was coded and examined as a moderator in subsequent analyses.

The Connectedness to Nature Scale [

1] (11 studies) primarily captured cognitive and affective aspects of nature connectedness. Measures including the Connection to Nature Scale(modified from [

75] (4 studies) and the Nature Relatedness Scale [

2] (1 study) encompassed cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions. The Inclusion of Nature in Self scale [

3] (2 studies) focused mainly on cognitive aspects. Among the study-developed measures, the measure of [

79] targeted affective aspects, whereas the measure of [

80] addressed both affective and behavioral components.

Prosociality was most frequently measured by the Altruism Scale [

81] (4 studies), followed by the Dispositional Positive Emotions Scale—Self-Transcendent Emotions [

82] (3 studies). The Big Five Inventory—Agreeableness [

83] and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index—Perspective Taking [

84] each appeared in 2 studies. Single-study measures included the Prosocialness Scale for Adults [

85], the Prosocial Tendencies Measure [

86], the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire—Prosocial Subscale [

87], the Value Orientations—Altruistic Subscale [

88], Self-Transcendence Value [

34], the Gratitude Questionnaire [

89], HEXACO Honesty–Humility [

90], Behavioral, Emotional, and Social Skills Inventory (BESSI)—Cooperation [

91], and Prosocial Behavioral Intentions [

92].

These measures were categorized into three primary dimensions of prosociality: behavioral tendencies, personality traits, and values. Measures of behavioral tendencies, including the Altruism Scale, Prosocialness Scale for Adults, Prosocial Tendencies Measure, SDQ Prosocial Subscale, and Prosocial Behavioral Intentions assess self-reported or intended prosocial actions. The Dispositional Positive Emotions Scale—Self-Transcendent Emotions, Big Five Inventory—Agreeableness, Interpersonal Reactivity Index, Perspective Taking, Gratitude Questionnaire, HEXACO Honesty–Humility, and BESSI—Cooperation assess stable dispositional characteristics associated with prosociality. The Value Orientations—Altruistic Subscale and Self-Transcendence Value capture moral motivations and value-based prosocial inclinations.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Sample Size | Sample Type | Age Distribution/

Mean Age | Females (%) | Location | Nature Connectedness Scales | Prosociality Scales | Type of Publication | Effect Size (r) |

|---|

| Chen and Pensini, 2024 [93] | 715 | Mixed | 18–85

52.36 | 70.3% | Australia | Connection to Nature Scale (modified from [75]) | Prosocial Behavioral Intentions [92] | PRJ | 0.46 |

| Dillon and Lee, 2023 [94] | 268 | Mixed | 18–35

23.85 | 69.2% | Singapore | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | Value Orientations—Altruistic Subscale [88] | PRJ | 0.30 |

| Duong and Pensini, 2023 [95] | 632 | Mixed | 18–88

54.89 | 72.7% | Australia | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | HEXACO–Honesty-Humility Subscale [90] | PRJ | 0.39 |

| Feraco, Carbone, and Meneghetti, 2025 [96] | 702 | Students | 12–20

16.18 | 45.4% | Italia | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | BESSI–Cooperation [91] | PRJ | 0.25 |

| Jacobs and McConnell, 2022 [97] S1 | 266 | Students | NR

19.09 | 54.5% | USA | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | Dispositional Positive Emotions Scale–Self-Transcendent Emotions [82] | PRJ | 0.35 |

| Jacobs and McConnell, 2022 [97] S2 | 404 | Students | NR

18.97 | 73.8% | USA | Inclusion of Nature in Self [3] | Dispositional Positive Emotions Scale–Self-Transcendent Emotions [82] | PRJ | 0.21 |

| Jacobs and McConnell, 2022 [97] S3 | 402 | Students | NR

NR | NR | USA | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | Dispositional Positive Emotions Scale–Self-Transcendent Emotions [82] | PRJ | 0.40 |

| Markowitz et al., 2012 [66] | 115 | Students | 18–31

19 | 72% | USA | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | Big Five Inventory—Agreeableness Subscale [83] | PRJ | 0.06 |

| Mayer and Frantz, 2004 [1] S2 | 102 | Students | NR

NR | NR | USA | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | Interpersonal Reactivity Index–Dispositional Perspective Taking Ability [84] | PRJ | 0.37 |

| Mayer and Frantz, 2004 [1] S4 | 135 | Mixed | 14–89

36 | 65.9% | USA | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | Interpersonal Reactivity Index–Dispositional Perspective Taking Ability [84] | PRJ | 0.51 |

| Mead et al., 2021 [80] | 138 | Mixed | 18–68

33.32 | 79% | U.K | Nature Connection (study-developed; inspired by [1,77,78]) | Gratitude Questionnaire [89] | PRJ | 0.26 |

| Mei et al., 2024 [12] | 289 | Community | NR

30.98 | 44.6% | China | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | Prosocial Tendencies Measure [98] | PRJ | 0.54 |

| McConnell and Jacobs, 2020 [67] | 202 | Students | NR

18.83 | 65.3% | USA | Inclusion of Nature in Self [3] | Self-transcendence Value [34] | PRJ | 0.13 |

| Neaman et al., 2022 [99] S1 | 841 | Mixed | 16–80

31.2 | 71% | Russia | Connection to Nature Scale (modified from [75]) | Altruism Scale [81] | PRJ | 0.25 |

| Neaman et al., 2022 [99] S2 | 418 | Mixed | 12–80

33.5 | 59% | Chile and Mexico | Connection to Nature Scale (modified from [75]) | Altruism Scale [81] | PRJ | 0.28 |

| Neaman et al., 2023 [100] | 438 | Students | 11–19

15 | 51% | Chile, Spain, Mexico, and Guatemala | Connection to Nature Scale (modified from [75]) | Altruism Scale [81] | PRJ | 0.36 |

| Rahe and Jansen, 2024 [101] | 184 | Mixed | 17–74

31.39 | 70.6% | Germany | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | Prosocialness Scale for Adults [85] | PRJ | 0.30 |

| Whitten et al., 2018 [79] | 26,848 | Students | NR

11.92 | 49.7% | Australia | three items drawn from the Connection to Nature Index [76] and the Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire—Prosocial Behavior Subscale (SDQ) [87] | PRJ | 0.30 |

| Yurtsever and Angin, 2022 [102] | 305 | Community | NR

NR | NR | Turkey | Nature Relatedness Scale [2] | Altruism Scale [81] | PRJ | 0.40 |

| Zhang, Howell, and Iyer, 2014 [103] | 1108 | Mixed | 18–88

41.08 | 44.4% | USA | Connectedness to Nature Scale [1] | Big Five Inventory—Agreeableness Subscale [83] | PRJ | 0.31 |

3.4. The Association Between Nature Connectedness and Prosociality

In line with the recommendations of [

104], Pearson’s correlation coefficients (

r) were interpreted using empirically derived thresholds specific to psychological research, with

r = 0.10 considered small,

r = 0.20 moderate, and

r = 0.30 large. These cut-offs offer a more empirically grounded benchmark for assessing effect sizes in psychological studies than the conventional Cohen’s rule of thumb. The correlations between nature connectedness and prosociality across the included studies ranged from 0.06 to 0.54. Specifically, effect sizes of

r = 0.06 and

r = 0.13 were non-significant, representing negligible associations, whereas the remaining 18 correlations were statistically significant. Among these significant effects, 8 were in the moderate range (

r = 0.20–0.30), and 10 reached or exceeded the threshold for large effects (

r ≥ 0.30).

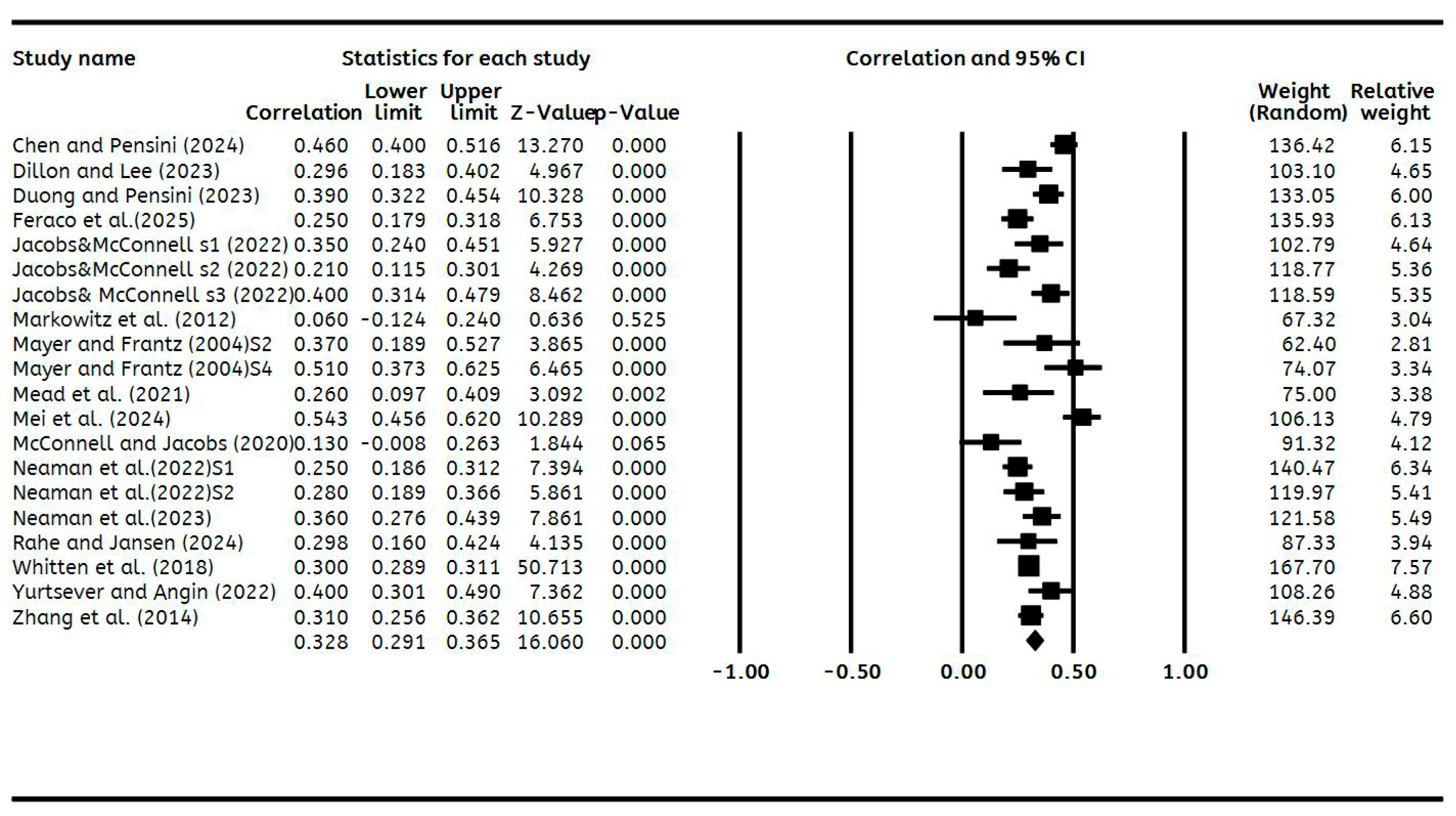

To test the hypothesis that higher levels of nature connectedness would be associated with greater prosociality, a mean effect size was calculated across all included samples (

k = 20,

N = 34,512). The meta-analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Version 3.7; Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA), employing a random-effects restricted maximum likelihood estimation model. The overall mean weighted effect size was

r = 0.33, 95% CI [0.291, 0.365],

p < 0.001. In line with the empirically derived benchmarks for individual differences research in psychology [

104], this represents a large effect, indicating a positive and reliable association between nature connectedness and prosociality.

Figure 2 displays the corresponding forest plot of study effect sizes.

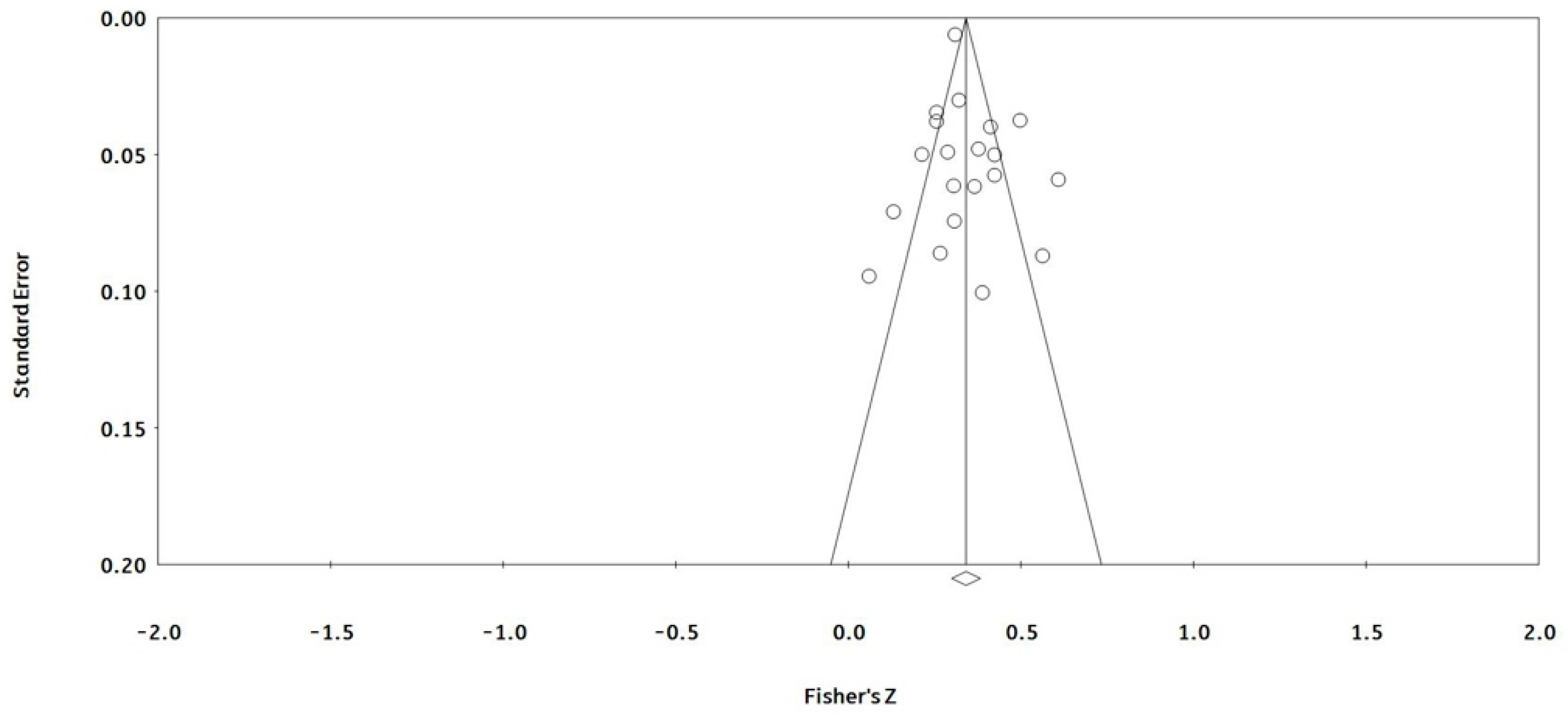

Publication bias was assessed through inspection of the funnel plot and formal statistical tests. While advanced methods such as p-curve analysis could offer further insight, they could not be employed due to the inconsistent reporting of exact

p values or test statistics across primary studies. Our assessment of publication bias was therefore reliant on Egger’s test and the trim-and-fill method, which represent a comprehensive approach given these constraints. Visual inspection indicated symmetry in the funnel plot (

Figure 3), suggesting a balanced distribution of studies around the mean effect. Consistently, Egger’s regression test revealed no significant evidence of publication bias, with the intercept not differing significantly from zero (

B0 = 0.68, 95% CI [−0.70, 2.05],

t (18) = 1.04,

p = 0.31). Further assessment using Duval and Tweedie’s Trim and Fill method indicated that when searching for missing studies to the right of the mean effect, two studies were imputed, resulting in a slightly higher combined effect (

r = 0.346, 95% CI [0.306, 0.383]) compared with the original estimate (

r = 0.328, 95% CI [0.291, 0.365]). When searching to the left of the mean, no studies were imputed, and the effect estimate remained unchanged. Classic Fail-Safe

N analysis indicated that 7875 null studies would be required to bring the meta-analytic effect size to a non-significant result. Orwin’s fail-safe

N further indicated that 44 studies with an average correlation of 0 would be required to reduce the combined effect size below

r = 0.1. Together, these analyses suggest that the meta-analytic effect is robust both statistically and substantively and is unlikely to be meaningfully influenced by unpublished or missing studies.

Heterogeneity tests indicated that the effects included in the meta-analysis were significantly heterogeneous,

Q(19) = 98.44,

p < 0.001,

I2 = 80.70%, suggesting substantial variability across studies. To examine whether any single study disproportionately influenced the overall effect, potential outliers were evaluated following Hanson and Bussière’s criteria [

74]. Specifically, the study with the lowest effect size (

r = 0.06) and the study with the highest effect size (

r = 0.54) were removed in separate sensitivity analyses. In both cases, the

Q statistic did not decrease by more than 50% (

Q(18) = 91.02 and

Q(18) = 73.96, respectively), indicating that no study qualified as an outlier. This high level of heterogeneity suggests that the variability in effect sizes across studies is largely due to true differences between studies rather than sampling error, supporting further exploration of potential moderators. Based on these findings, the high level of heterogeneity appears to reflect true differences between studies rather than the influence of a single extreme effect, supporting further exploration of potential moderators.

3.5. Moderator Analyses

Method of meta-regression was conducted to examine whether the mean age of participants and the proportion of females in samples moderated the association between nature connectedness and prosociality. Results indicated that samples with a higher mean age demonstrated significantly greater effect sizes (slope = 0.0061, SE = 0.002, 95% CI [0.0022, 0.0099], p = 0.002). In contrast, a higher percentage of female participants in the samples was associated with significantly smaller effect sizes (slope = −0.0048, SE = 0.0022, 95% CI [−0.0092, −0.0005], p = 0.0303).

To further elucidate the sources of heterogeneity and examine the robustness of the overall effect, categorical moderator analyses were conducted based on sample type, geographic location of the sample, nature connectedness scales, dimensions of nature connectedness scales, prosociality scales, and dimensions of prosociality scales (see

Table 2). The analysis for sample type revealed a statistically significant moderating effect,

Q(2) = 6.42,

p = 0.04. The effect size was largest in community samples (

r = 0.47, 95% CI [0.32, 0.60],

p < 0.001,

k = 2), followed by mixed samples (

r = 0.34, 95% CI [0.28, 0.40],

p < 0.001,

k = 9), and was smallest, though still substantial, in student samples (

r = 0.28, 95% CI [0.23, 0.33],

p < 0.001,

k = 9). This pattern may be partially explained by the previously identified influence of participant age. Given that community samples typically comprise older adults with more life experience, while student samples are exclusively younger, the effect size gradient aligns with the positive association between mean sample age and effect size. The analysis for geographic location did not yield a significant moderating effect,

Q(4) = 3.33,

p = 0.50. Crucially, all regional effect sizes were significantly different from zero, underscoring the robustness and cross-cultural generalizability of the positive link between nature connectedness and prosociality.

A significant moderating effect was found for the specific type of nature connectedness scale used, Q(4) = 16.18, p = 0.003. The strength of the correlation varied across instruments. The strongest association was observed for the Nature Relatedness scale (r = 0.40, 95% CI [0.30, 0.49], p < 0.001, k = 1), followed by the Connectedness to Nature Scale (r = 0.35, 95% CI [0.29, 0.41], p < 0.001, k = 11) and the Connection to Nature Scale (r = 0.34, 95% CI [0.23, 0.44], p < 0.001, k = 4). Study-developed measures yielded a significant correlation of comparable magnitude (r = 0.30, 95% CI [0.29, 0.31], p < 0.001, k = 2). In contrast, the Inclusion of Nature in Self (INS) scale, a single-item pictorial measure, demonstrated a significantly weaker, albeit still significant, association (r = 0.18, 95% CI [0.11, 0.26], p < 0.001, k = 2).

Furthermore, a analysis categorizing scales based on their psychological dimensionality also revealed a significant moderating effect, Q(4) = 13.24, p = 0.01. Scales encompassing a combination of affective and cognitive components (r = 0.35, 95% CI [0.29, 0.41], p < 0.001, k = 11) and those integrating affective, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions (r = 0.35, 95% CI [0.26, 0.44], p < 0.001, k = 5) yielded the strongest effects. Purely affective (r = 0.30, 95% CI [0.29, 0.31], p < 0.001, k = 1) and affective-behavioral composites (r = 0.26, 95% CI [0.10, 0.40], p = 0.002, k = 1) demonstrated moderate correlations. Notably, scales focusing solely on the cognitive dimension (e.g., the INS scale) exhibited the weakest association with the outcome variable (r = 0.18, 95% CI [0.11, 0.26], p < 0.001, k = 2). These findings indicate that the observed relationship is robust across operationalizations but is meaningfully moderated by the choice of instrument. Specifically, multi-dimensional scales that include affective elements show stronger associations, while cognitively focused measures show weaker ones.

A preliminary moderator analysis of each specific prosociality scale revealed significant heterogeneity, Q(12) = 69.08, p < 0.001. The observed effect sizes for individual scales ranged from small and non-significant (e.g., for the BFI Agreeableness Subscale) to large and highly significant (e.g., for the Prosocial Tendencies Measure), indicating that the strength of the correlation varied substantially across different measurement instruments. These variations likely reflect both substantive differences in construct coverage and instability in estimates due to several measures being represented by a single study. To provide a more theoretically meaningful synthesis, we grouped the instruments into three broad, conceptually derived categories based on their primary measurement focus: (a) prosocial behavioral tendencies, capturing self-reported frequencies of past prosocial acts or generalized behavioral intentions; (b) prosocial traits, which encompass dispositions such as agreeableness, honesty-humility, cooperation, gratitude, and perspective-taking; and (c) prosocial values, representing abstract motivational goals and guiding principles. The test of between-group heterogeneity was not statistically significant, Q(2) = 3.12, p = 0.21. This indicates that the magnitude of the correlation did not differ significantly across these three overarching conceptual domains.

Notwithstanding the non-significant Q-test, an inspection of the point estimates reveals a consistent and theoretically meaningful pattern. The strongest association was observed for scales measuring Prosocial Behavioral Tendencies (r = 0.36, 95% CI [0.30, 0.42], p < 0.001, k = 8). Scales assessing Prosocial Traits yielded a slightly lower, yet robust correlation (r = 0.32, 95% CI [0.26, 0.38], p < 0.001, k = 10). The smallest point estimate was found for Prosocial Values (r = 0.22, 95% CI [0.05, 0.37], p = 0.01, k = 2); however, the notably wide confidence interval for this dimension, likely attributable to the small number of studies (k = 2), suggests this estimate should be interpreted with caution. In summary, while the overall difference between the three broad dimensions of prosociality was not statistically significant, the pattern of results suggests a gradient where more concrete, behavioral measures demonstrate the strongest associations, followed by stable personality traits, with more abstract values showing the weakest association. The non-significant finding at this higher level of categorization may indicate that differences within each dimension (i.e., among the various specific scales) are substantial, potentially outweighing the differences between them. The positive and significant correlations for all three dimensions confirm that prosociality, regardless of its operationalization, is a robust correlate of nature connectedness.

4. Discussion

The present meta-analysis synthesized evidence from 20 independent samples (

N = 34,512) to quantitatively examine the association between nature connectedness and prosociality. The results revealed a robust, positive overall correlation (

r = 0.33,

p < 0.001), which, according to empirically derived thresholds, constitutes a large effect in psychological research [

104]. The robustness of our primary finding is supported by a series of publication bias analyses. Importantly, Egge’s regression test was non-significant, indicating no statistical evidence of funnel plot asymmetry and a low likelihood of substantial publication bias. This was visually confirmed by a symmetrical funnel plot. Moreover, Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill adjustment estimated that potentially missing studies would, if anything, lead to a slightly larger effect size, reinforcing rather than undermining our conclusion. Combined with fail-safe

N calculations suggesting an implausibly large number of unpublished null studies would be needed to nullify our results, these tests collectively affirm that the observed association is both reliable and robust.

Our findings align with and extend the existing meta-analytic literature on nature connectedness. Previous syntheses have robustly established its link to pro-environmental behavior (e.g., [

6,

7]) and to personal well-being (e.g., [

21,

105]). The present meta-analysis confirms that a stronger bond with nature is associated with enhanced human functioning. Crucially, it demonstrates that the scope of its benefits transcends concern for the environment and the self, extending robustly to other-directed, human-focused moral and social outcomes. This pattern suggests that nature connectedness fosters a generalized capacity for care that is multi-directional, simultaneously promoting actions that benefit the ecosystem, the self, and the wider human community.

The current synthesis directly addresses a key gap in the existing literature. As noted, prior research has yielded inconsistent results, with some studies reporting significant associations and others finding none. Moreover, existing meta-analytic work has largely operationalized prosociality narrowly in terms of pro-environmental behaviors (e.g., [

6,

7]). While crucial, this focus leaves a critical question unanswered: Is the bond with nature specifically linked to caring for the environment, or does it extend to a broader ethic of care that encompasses human well-being? By synthesizing studies that measure prosociality directed toward other people, the current meta-analysis offers a definitive answer. The primary theoretical contribution of this meta-analysis lies in demonstrating that the psychological bond with nature is not an isolated moral domain, but rather a manifestation of a broader ethic of care that encompasses humanity itself. Our finding of a robust, positive association between nature connectedness and human-directed prosociality provides strong empirical support for the moral expansiveness framework [

55]. This evidence suggests that the essence of “environmental morality” may, at its core, reflect a generalized capacity for care that transcends specific targets—whether a forest or a fellow human being. Such a perspective challenges domain-specific interpretations of moral concern and positions an expansive moral self-identity as the critical nexus bridging ecological and social forms of care.

Our results, which favor a generalized model of care, invite a critical comparison between competing theoretical accounts to further clarify the psychological meaning of this association. Empathy-based models posit that prosociality arises from affective resonance—feelings of compassion, sympathy, or empathic concern that motivate helping behavior toward those in need [

30,

49]. From this perspective, nature connectedness promotes prosociality because it enhances emotional attunement and self-transcendent emotions such as awe or gratitude, which broaden one’s capacity for empathy. In contrast, the moral expansiveness framework [

55] emphasizes the scope rather than the intensity of moral concern: individuals high in nature connectedness extend their moral circle beyond the self to include both human and nonhuman entities. While the empathy-based view highlights proximal emotional mechanisms, the moral expansiveness account situates the effect within a broader moral-cognitive orientation. The present findings suggest that these perspectives are not mutually exclusive but complementary. Affective engagement with nature may provide the emotional substrate for empathy, which, when integrated into one’s self-concept and moral identity, fosters an expanded moral regard encompassing people and the planet alike.

Beyond confirming this robust overall relationship, moderator analyses yielded further nuance, revealing that the strength of the association is shaped by both the characteristics of the samples studied and, most notably, by how the core constructs are measured. Meta-regression analyses indicated that the association strengthened significantly with the mean age of the samples. Categorical moderator analysis also revealed that the strongest effects were found in community samples, followed by mixed samples, with the smallest (though still substantial) effects in student samples. These results suggest that the integration of nature connectedness with a prosocial orientation may be a developmental process, deepening with life experience, social maturity, and perhaps greater opportunities for reflection and value internalization [

106,

107], whereby older individuals may more coherently incorporate care for nature and care for others into a self-integrated moral identity [

108,

109]. This developmental trajectory implies a potential underlying mechanism wherein sustained interactions with nature across the lifespan progressively strengthens both environmental and moral identities, culminating in a more stable and generalized prosocial disposition.

Conversely, a higher percentage of female participants was associated with a slightly weaker effect size. This may reflect ceiling effects or reduced variability in prosocial measures among women, who often report higher levels of both prosociality and nature connectedness than men [

110,

111]. It is also possible that gender-role socialization fosters prosocial orientations among women irrespective of nature connectedness [

112], thereby attenuating the incremental predictive value of nature connectedness in predominantly female samples.

The non-significant moderating effect of geographic location is a theoretically informative finding. The fact that the positive association was robust across all cultural regions studied, with all effect sizes significantly different from zero, provides compelling evidence for its cross-cultural generalizability. This robustness suggests that the link between nature connectedness and prosociality may be a fundamental aspect of human psychology, transcending specific cultural norms or economic conditions.

In addition to sample characteristics, a key finding is that the strength of the association between nature connectedness and prosociality varied substantially depending on how the constructs were measured. For nature connectedness, a clear hierarchy emerged: scales incorporating affective components (e.g., emotional affinity, love for nature), such as the Connectedness to Nature Scale [

1] and the Nature Relatedness Scale [

2], showed stronger correlations with prosociality than more cognitively oriented measures, such as the Inclusion of Nature in Self scale [

3]. This pattern illuminates a critical mediating pathway: affective engagement with nature is a potent catalyst for the self-transcendent emotions (e.g., awe, wonder) that are central to prosociality [

58,

59,

113]. These emotions, by shifting focus away from the self, can directly facilitate empathic concern and a willingness to act for the benefit of others, providing a plausible psychological mechanism that links the affective core of nature connectedness to prosocial outcomes.

Although cognitive aspects of nature connectedness alone exhibited relatively small effects on prosociality, their predictive value increased substantially when combined with affective and/or behavioral components. This pattern suggests that cognitive understanding of one’s relationship with nature, while necessary, is insufficient on its own to promote prosocial behavior. Rather, cognition appears to act synergistically with affective engagement and behavioral commitment, highlighting that a multi-dimensional integration of thoughts, feelings, and actions, which is consistent with a holistic environmental identity, underpins the strongest associations with prosociality. Environmental identity, as a facet of the self-concept reflecting one’s perceived connection to the nonhuman natural environment, provides a concrete framework through which individuals can translate abstract moral principles into self-relevant commitments [

114]. By situating oneself within a larger ecological system, environmental identity enhances perspective-taking, reinforces the salience of interdependence, and anchors moral concern in a tangible context. We posit that this process facilitates moral identity because moral self-concepts are strengthened when values are linked to personally meaningful and coherent self-structures. Specifically, when care for nature is internalized as a core component of who one is, it naturally reinforces and expands one’s moral orientation, fostering moral expansiveness [

55] and supporting prosocial behavior that extends to both human and nonhuman entities. This identity-level integration provides a more stable and enduring foundation for prosociality than situational empathy alone.

A theoretically informative pattern also emerged from the analysis of prosociality measures. It is crucial to note that the overall effect did not differ significantly across the three broad categories of prosociality, indicating that the association is robust across different conceptualizations. Nevertheless, an inspection of the point estimates suggests that nature connectedness demonstrated a stronger association with prosocial behavioral tendencies and prosocial traits than with prosocial values. This pattern can be parsimoniously interpreted by conceptualizing nature connectedness as a dispositional orientation characterized by empathy, openness, and self-transcendence—core features that it shares with prosocial personality traits [

115]. This shared motivational foundation allows for a more direct translation between the two dispositions and their behavioral manifestations. In other words, individuals with a strong, trait-like connection to nature are, by disposition, more likely to possess the empathetic and other-oriented tendencies that readily catalyze prosocial actions.

In contrast, the formation of abstract prosocial values is a more complex and protracted process, requiring the internalization of cultural norms, sustained socialization practices, as well as the development of advanced abstract thinking capabilities that allow individuals to reason about and commit to universal moral principles [

116,

117]. In another word, unlike traits or behaviors, which may directly reflect dispositional tendencies toward care, prosocial values emerge through extended processes of internalization and moral development. Consequently, while nature connectedness as a trait aligns closely with prosocial tendencies at the dispositional and behavioral level, its link to value systems may unfold more gradually and indirectly. For instance, repeated experiences of connectedness with nature may foster empathy and care that, through socialization practices in families, schools, and peer groups, gradually solidify into enduring value commitments. Self-transcendent emotions such as awe or gratitude, frequently evoked in contact with nature, may stimulate moral reflection and over time crystallize into prosocial value orientations.

4.1. Practical Implications

The robust association between nature connectedness and prosociality established in this meta-analysis offers a compelling foundation for designing targeted interventions in sustainability education and social innovation. The findings suggest that fostering a connection to nature can serve as a powerful lever for cultivating a more cooperative and caring society. To translate this evidence into practice, we propose two specific intervention models that directly operationalize our key findings.

First, we propose Nature-Integrated Social and Emotional Learning (NI-SEL) for educational settings. This model moves beyond traditional classroom-based SEL by using nature as an active context and resource for developing empathy, cooperation, and emotional regulation. An NI-SEL curriculum could include: (1) “Awe Walks” and Sensory Immersion to elicit self-transcendent emotions that reduce self-focus and broaden social awareness; (2) Collaborative Ecological Projects such as designing a school garden or building insect hotels, which require teamwork toward a shared, nature-based goal; and (3) Role-Playing and Perspective-Taking Exercises that encourage students to imagine the viewpoints of both animals and people affected by environmental issues. This model directly applies our finding that affective engagement is a critical pathway, using structured nature experiences to build the emotional underpinnings of prosociality within sustainability education.

Second, for community and corporate contexts, we propose Prosocial Environmental Volunteering (PEV) programs. Unlike standard environmental volunteering, PEV is explicitly designed to strengthen both community bonds and nature connectedness. These programs would integrate cooperative tasks, such as community-based habitat restoration or urban reforestation, with facilitated reflection that makes the link between caring for the environment and caring for the community explicit. For example, volunteers could work in small, interdependent teams to clear invasive species and then participate in a guided discussion on how interdependence in nature mirrors social interdependence. This model leverages our finding that the synergy of behavioral commitment and social cooperation underpins the strongest associations, positioning collective environmental action as a vehicle for social innovation and community resilience.

By proposing these concrete models, we provide a clear blueprint for educators, policymakers, and community leaders to simultaneously address social fragmentation and environmental challenges, harnessing the symbiotic relationship between human care for nature and care for one another.

4.2. Limitations

Several limitations of the current meta-analysis should be acknowledged. A primary limitation stems from the nature of the synthesized evidence. This review is a meta-analysis of correlational studies, which, by its very design, cannot establish causality. While this provides robust evidence for a reliable association between nature connectedness and prosociality, the inherent limitations of correlational designs preclude definitive conclusions regarding causality or directionality. It remains unclear whether heightened nature connectedness fosters prosocial tendencies, whether prosocial dispositions promote a stronger sense of connection to nature, or whether the relationship is bidirectional and mutually reinforcing. The correlational nature of the synthesized evidence precludes definitive conclusions about causality, leaving it unclear whether the link stems from nature connectedness fostering prosociality, the reverse causal pathway, a bidirectional influence, or confounding by unmeasured third variables (e.g., a general empathetic personality). Future research could specifically synthesize evidence from longitudinal and intervention studies, allowing for a more precise estimation of temporal sequencing and causal direction, and thereby complementing the correlational evidence established here.

Furthermore, the potential for non-independence of data should be considered. Several independent samples included in the analysis originated from the same research teams or large-scale collaborative projects. Although each sample comprised unique participants and was treated as an independent unit in our analyses, shared methodological approaches or measurement traditions within these research lineages may have introduced a clustering effect that our models could not fully account for. This might influence the precision of the estimated effects, though the robustness of our main findings suggests that the overall conclusion of a positive association remains valid.

Moreover, the scope and validity of our findings are constrained by the methodological choices and availability of primary studies. The reliance on self-reported measures of prosociality introduces the potential for common method bias and social desirability effects. Moreover, the search strategy and inclusion criteria, while comprehensive, may have missed unpublished studies, leading to a potential publication bias. Although statistical diagnostics indicated that this risk was relatively small, it cannot be completely ruled out.

Finally, the significant residual heterogeneity suggests that important sources of variability remain unaccounted for. While moderators such as measurement type and sample characteristics explained part of the variance, other factors, such as individual differences in emotional dispositions, early life experiences with nature, and the broader social or cultural contexts of participants, may further shape the strength of the association. Future primary studies should therefore provide more detailed reporting and systematically examine these factors to allow for a fuller understanding of the boundary conditions of the nature connectedness–prosociality link.