Policy Implementation and Sustainable Governance in Chinese SOEs: A Study of Mixed-Ownership Reform and ESG Rating Divergence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

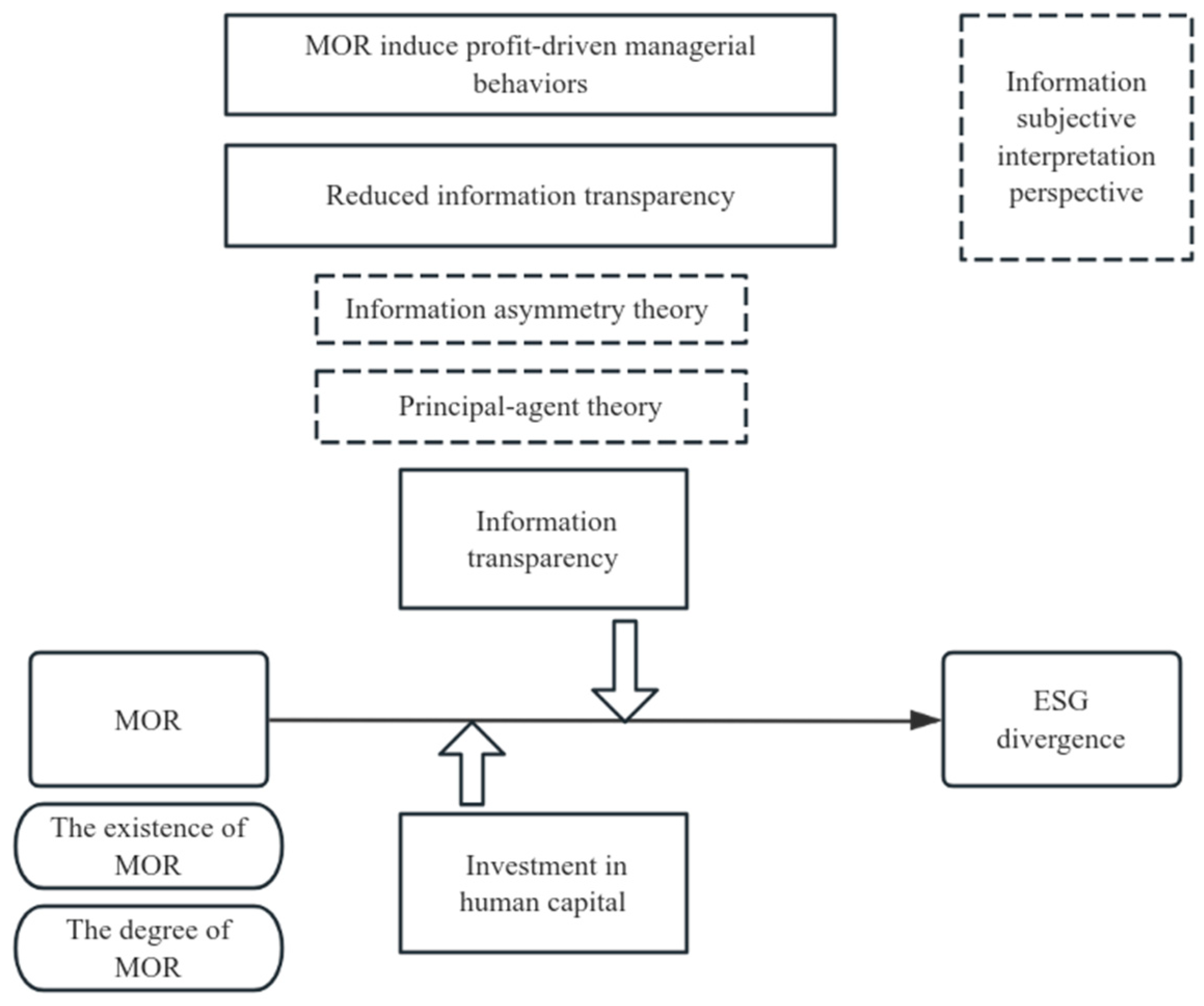

3. Hypotheses Development

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

4.2. Model Design

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Baseline Results

5.3. Robustness Checks

5.4. Heterogeneity Test

- Equity concentration degree

- 2.

- Firm size

- 3.

- Industry

- 4.

- Degree of ESG disclosure

5.5. Further Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Y.T.; Guo, X.M.; Zeng, X.L. ESG Information Disclosure and ESG Rating Divergence: Consensus or Disagreement? A Comprehensive Discussion on the Institutional Norms of ESG in China. Account. Res. 2024, 1, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.Q.; Yang, Q.Q.; Hu, J. ESG rating divergence and stock price synchronicity. China Soft Sci. 2023, 8, 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.J.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, Y. Domestic and International Manifestations, Causes, and Countermeasures of Divergence in ESG Ratings. J. Nanhua Univ. 2023, 24, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.; Tang, Y. ESG rating and corporate debt financing cost: An empirical test based on multi-period DID. Manag. Mod. 2022, 6, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Zhao, X.; Jin, H. The impact of corporate ESG performance on its financing costs. Sci. Decis. 2022, 11, 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsantonis, S.; Serafeim, G. Four Things No One Will Tell You About ESG Data. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2019, 31, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhayawansa, S.; Tyagi, S. Sustainable Investing: The Black Box of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Ratings. J. Wealth Manag. 2021, 24, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongjun, X.; Xue, L. Responsible multinational investment: ESG and Chinese OFDI. Econ. Res. J. 2022, 57, 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xue, S. Green taxation and corporate ESG performance: A quasi-natural experiment based on the Environmental Protection Tax Law. Financ. Res. 2022, 9, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Avramov, D.; Cheng, S.; Lioui, A.; Tarelli, A. Sustainable investing with ESG rating uncertainty. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 145, 642–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Yang, H.Y.; Zhang, X.Y. ESG Rating Disagreement and the Cost of Debt. Chin. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2023, 4, 22–43+124. [Google Scholar]

- Dimson, E.; Marsh, P.; Staunton, M. Divergent ESG Ratings. J. Portf. Manag. 2020, 47, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Renneboog, L. On the Foundations of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 853–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.M.; Serafeim, G.; Sikochi, A. Why is corporate virtue in the eye of the beholder? The case of ESG ratings. Account. Rev. 2022, 97, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough, M.D.; Wand, X.; Wei, S. Does Voluntary ESG Reporting Resolve Disagreement Among ESG Rating Agencies? Eur. Account. Rev. 2024, 33, 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, Q.L. Research on the Causes of ESG Rating Divergence: From the Perspective of Literature Review. Financ. Mark. Res. 2023, 11, 130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.P.; Meng, Y.J.; Hu, B. Corporate ESG Performance and Debt Financing Costs: Theoretical Mechanisms and Empirical Evidence. Econ. Manag. J. 2023, 45, 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Y.; Liang, R.X.; Li, Y. Does ESG Affect Stock Liquidity? A Dual Perspective Based on ESG Ratings and Rating Disagreements. Stud. Int. Financ. 2023, 11, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.J.; Ding, X.J.; San, Z.Y. ESG Rating Divergence and Audit Risk Premium. Audit. Res. 2023, 6, 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.T.; Tian, B.A.; Shangguan, X.L. Does ESG Rating Disagreement Affect Auditor Risk Response Behavior? Based on the Perspective of Disclosure of Key Audit Matters. J. Financ. Dev. Res. 2023, 9, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Li, S.; Pan, J. The impact of ESG rating divergence on corporate social responsibility behavior: Evidence from targeted poverty alleviation. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2025, 45, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.F.Y.; Wang, Y.F.; Wu, Z.F. ESG Rating Disagreements and Corporate Green Innovation: Empirical Evidence from Chinese A-Share Listed Companies. Soft Sci. 2024, 38, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wu, L.; Xiao, Z. State-owned enterprise restructuring and IPO financing scale. Financ. Res. 2014, 3, 164–179. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Yu, M. Ownership structure and corporate innovation in privatized firms. Manag. World 2015, 4, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.Z.; Jin, Q.L. Mixed-Ownership Reform of State-Owned Enterprises and Investment Flexibility. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 50, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yin, X. How does mixed ownership reform affect corporate cash holdings? Manag. World 2018, 11, 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, G.; Liu, J.; Ma, X. Non-state-owned shareholder governance and executive compensation incentives in state-owned enterprises. Manag. World 2018, 5, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, C.; Lu, J.; Tao, Z. An empirical study on the effectiveness of state-owned enterprise restructuring. Econ. Res. 2006, 8, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.N.; Zhu, C.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Yao, S.Y.; Lou, Y.L. Asymmetry of Governance Mechanisms and Risk-Taking in the Mixed-Ownership Reform of State-Owned Enterprises. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2024, 27, 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.; Mai, S. Research on the impact of mixed ownership reform of state-owned enterprises on corporate social responsibility. Sci. Res. Manag. 2021, 11, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Z. Mixed ownership reform of state-owned enterprises, social responsibility information disclosure, and the preservation and appreciation of state-owned assets. Soft Sci. 2020, 34, 32–36. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/rkx202003006 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Ma, W.J.; Yu, B.J. Enterprise Ownership Attributes and Disagreements between Chinese and Foreign ESG Ratings. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 6, 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z. Is non-state-owned director governance pursuing immediate interests? Evidence from dividend distribution and related-party transactions of mixed-ownership reform state-owned enterprises. Econ. Issues 2024, 1, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D. Capital transfer, related-party transactions, and earnings management: Empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies. Econ. Manag. 2010, 32, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Qi, Z.; Wang, C.; Chen, X. Does mixed ownership reform improve enterprises’ radical innovation level? A perspective based on the enterprise life cycle. Financ. Res. 2022, 1, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Sun, L.; Guo, T.; Jiang, H.L. “Mixed ownership reform” and internal control quality: Empirical evidence from listed state-owned enterprises. Account. Res. 2020, 8, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Yin, M. Can improving internal control quality reduce divergence in corporate ESG ratings? Sci. Decis. 2024, 10, 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L. Equity concentration, internal control, and social responsibility. Study Pract. 2015, 10, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Liao, Y. A study on the differences and optimization of ESG rating systems: Evidence from Bloomberg and Wind. Financ. Regul. Res. 2023, 7, 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Y.; Gong, L. State-owned, privately-owned mixed shareholding and corporate performance improvement. Econ. Res. 2017, 3, 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.X.; Li, M.H. “Reverse” Mixed-Ownership Reform of Private Enterprises and Audit Opinions. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2023, 11, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhang, Z. Research on the mandatory disclosure standards of environmental information in heavily polluting industries. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2021, 23, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y.; Zhan, J.; Peng, Y. Research on the impact of executives’ green awareness on ESG rating divergence. J. Guizhou Univ. Financ. Econ. 2025, 3, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Shi, X.; Luo, R. The Economic Impact of Mixed Ownership Reform of State-owned Enterprises on Labor Allocation. Reform 2024, 11, 40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Cui, Y.W. An evaluation of the effectiveness of introducing technological strategic investors in the mixed-ownership reform of state-owned enterprises: From the perspective of corporate innovation. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2025, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y. Mixed-ownership reform of SOEs and ESG performance: Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 80, 1618–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Theme | Representative Studies | Core Focus | Contribution of This Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed-Ownership Reform (MOR) | [26,27,29,30,31] | Effects on governance risk, performance, and social responsibility | Extends the MOR literature to sustainability evaluation, focusing on ESG divergence |

| ESG Rating Divergence | [1,11,15,18] | Causes and economic consequences of divergence | Investigates MOR as a novel determinant of ESG divergence |

| Integrated Research Gap | — | Lack of analysis connecting ownership reform and ESG inconsistency | Provides first evidence of MOR’s relationship with ESG rating divergence through transparency and human capital pathways |

| Rating Agencies | ESG Ratings Methodology |

|---|---|

| Huazheng | 3 first-tier pillars, 16 second-tier themes, 44 third-tier key issues, 80 fourth-tier indicators, and 300+ underlying data points |

| FTSE Russell | 11 areas, more than 300 indicators |

| SynTao Green Finance | 14 core topics, 51 industry models, and 200 ESG indicators |

| Menglang | 6 first-tier, 30+ second-tier, and 90+ third-tier indicators covering 6 different dimensions |

| RKS | 56 industries 26 topics, 100+ indicators |

| Wind | 500+ management practice indicators, 1200+ risk indicators |

| Panel A: Aggregate ESG Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rating agencies | Median | Mean | Standard Dev | ||

| Huazheng | 4.44 | 4.55 | 1.16 | ||

| FTSE Russell | 2.4 | 2.66 | 1.10 | ||

| SynTao Green Finance | 5 | 5.41 | 1.08 | ||

| Menglang | 4.74 | 4.70 | 1.83 | ||

| RKS | 1.98 | 2.20 | 1.05 | ||

| Wind | 5.83 | 5.93 | 0.85 | ||

| Panel B: Correlations between ESG ratings | |||||

| Huazheng | FTSE Russell | SynTao Green Finance | Menglang | RKS | |

| Huazheng | 1 | ||||

| FTSE Russell | 0.31 | 1 | |||

| SynTao Green Finance | 0.32 | 0.65 | 1 | ||

| Menglang | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 1 | |

| RKS | 0.41 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 1 |

| Wind | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| Average | 0.51 | ||||

| Variable Name | Variable Abbreviation | Variable Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ESG rating divergence | The degree of divergence in ESG ratings is measured by the standard deviation of scores from six rating agencies: Huazheng, RKS, SynTao Green Finance, Wind, FTSE Russell, and Menglang | |

| Independent variable | MOR | Mix_dum | The dummy variable is defined as whether the proportion of non-state shareholders among the top ten shareholders exceeds 10% (coded as 1 if true, 0 otherwise). |

| Mix_ratio | The sum of the proportion of shares held by non-state shareholders among the top ten shareholders. | ||

| Controlled variables | Firm size | Size | The natural logarithm of total assets |

| Debt-to-Asset Ratio | Lev | Debt-to-asset ratio | |

| Return on Total Assets | ROA | Net income/total assets | |

| Return on Equity | ROE | Net income/total shareholders’ equity | |

| Cash Flow Level | Cashflow | Operating cash flow/sales | |

| Sales growth rate | Growth | Revenue change rate compared to last year | |

| The proportion of independent directors | Indep | The number of independent directors/the number of board directors | |

| Top ten ratio | Top10 | The shareholding ratio of the top ten shareholders | |

| Market-to-book ratio | BM | Market-to-book ratio | |

| TobinQ | TobinQ | TobinQ | |

| Years Since Listing | ListAge | Years since listing | |

| Turnover of total capital | ATO | Net sales/Average total assets | |

| Board size | Bsize | The natural logarithm of total directors |

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | p25 | p50 | p75 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esg_div | 10,365 | 0.930 | 0.820 | 0 | 0 | 0.840 | 1.640 | 3.130 |

| Mix_dum | 10,365 | 0.570 | 0.500 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10,365 | 21.82 | 20.60 | 0.940 | 5.130 | 13.28 | 34.29 | 78.61 | |

| Size | 10,365 | 22.93 | 1.420 | 19.92 | 21.92 | 22.79 | 23.78 | 27.16 |

| Lev | 10,365 | 0.490 | 0.200 | 0.0700 | 0.340 | 0.500 | 0.640 | 0.950 |

| ROA | 10,365 | 0.0300 | 0.0600 | −0.330 | 0.0100 | 0.0300 | 0.0500 | 0.220 |

| ROE | 10,365 | 0.0400 | 0.160 | −1.030 | 0.0200 | 0.0600 | 0.110 | 0.470 |

| Cashflow | 10,365 | 0.0500 | 0.0700 | −0.170 | 0.0100 | 0.0500 | 0.0800 | 0.280 |

| Growth | 10,365 | 0.140 | 0.470 | −0.700 | −0.0500 | 0.0700 | 0.220 | 5.220 |

| Indep | 10,365 | 0.380 | 0.0600 | 0.300 | 0.330 | 0.360 | 0.420 | 0.600 |

| Top10 | 10,365 | 0.570 | 0.150 | 0.220 | 0.460 | 0.570 | 0.680 | 0.920 |

| BM | 10,365 | 1.640 | 1.910 | 0.0500 | 0.530 | 1.010 | 1.960 | 14.25 |

| TobinQ | 10,365 | 1.900 | 1.460 | 0.770 | 1.080 | 1.410 | 2.110 | 15.40 |

| ListAge | 10,365 | 2.750 | 0.550 | 1.100 | 2.480 | 2.940 | 3.140 | 3.430 |

| ATO | 10,365 | 0.620 | 0.480 | 0.0400 | 0.310 | 0.510 | 0.780 | 3.380 |

| Bsize | 10,365 | 0.770 | 0.0900 | 0.480 | 0.730 | 0.790 | 0.790 | 1 |

| Variables | Esgdiv | Esgdiv | Esgdiv | Esgdiv |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Mix_dum | 0.077 *** | 0.046 *** | ||

| (3.91) | (2.69) | |||

| 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | |||

| (2.78) | (3.13) | |||

| Size | 0.207 *** | 0.210 *** | ||

| (20.40) | (20.73) | |||

| Lev | −0.095 * | −0.099 * | ||

| (−1.69) | (−1.77) | |||

| ROA | −0.882 *** | −0.896 *** | ||

| (−3.34) | (−3.40) | |||

| ROE | −0.024 | −0.021 | ||

| (−0.26) | (−0.23) | |||

| Cashflow | 0.107 | 0.103 | ||

| (0.97) | (0.94) | |||

| Growth | −0.046 *** | −0.048 *** | ||

| (−4.13) | (−4.27) | |||

| Indep | −0.047 | −0.028 | ||

| (−0.29) | (−0.17) | |||

| Top10 | 0.029 | −0.010 | ||

| (0.45) | (−0.16) | |||

| BM | −0.054 *** | −0.053 *** | ||

| (−7.68) | (−7.64) | |||

| TobinQ | 0.050 *** | 0.051 *** | ||

| (10.14) | (10.34) | |||

| ListAge | 0.018 | 0.017 | ||

| (1.00) | (0.98) | |||

| ATO | −0.007 | −0.006 | ||

| (−0.34) | (−0.27) | |||

| Bsize | 0.011 | 0.037 | ||

| (0.11) | (0.34) | |||

| Constant | 0.318 ** | −4.363 *** | 0.332 ** | −4.432 *** |

| (2.09) | (−17.09) | (2.25) | (−17.42) | |

| N | 10,365 | 10,365 | 10,365 | 10,365 |

| R2 | 0.491 | 0.546 | 0.490 | 0.547 |

| Controls | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Industry/year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Mix_Diversity | Esgdiv4 | Esgdiv4 | L. Mix | L. Mix | PSM | PSM | DID |

| Mix_dum_post | 0.050 * | |||||||

| (1.70) | ||||||||

| Post | −0.006 | |||||||

| (−0.20) | ||||||||

| Mix_diversity | 0.021 ** | |||||||

| (2.28) | ||||||||

| Mix_dum | 0.060 *** | 0.066 *** | 0.038 ** | |||||

| (3.54) | (3.55) | (2.17) | ||||||

| 0.001 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.001 *** | ||||||

| (3.20) | (3.54) | (2.60) | ||||||

| Constant | −4.403 *** | −1.137 *** | −1.211 *** | −4.296 *** | −4.386 *** | −4.583 *** | −4.625 *** | −4.363 *** |

| (−17.31) | (−4.27) | (−4.55) | (−15.55) | (−15.95) | (−17.05) | (−17.23) | (−17.09) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 10,365 | 10,365 | 10,365 | 8572 | 8572 | 8458 | 8458 | 10,365 |

| R-squared | 0.546 | 0.420 | 0.420 | 0.503 | 0.504 | 0.546 | 0.547 | 0.546 |

| industry/year | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Panel A | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Higher Top10 | Lower Top10 | Higher Top10 | Lower Top10 | |

| Mix_dum | 0.039 | 0.046 ** | ||

| (1.13) | (2.36) | |||

| 0.001 | 0.002 *** | |||

| (1.30) | (3.18) | |||

| Constant | −4.585 *** | −4.260 *** | −4.685 *** | −4.303 *** |

| (−10.38) | (−13.47) | (−10.50) | (−13.63) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 2592 | 7773 | 2592 | 7773 |

| R-squared | 0.542 | 0.558 | 0.542 | 0.559 |

| industry/year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Panel B | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Larger Firm | Smaller Firm | Larger Firm | Smaller Firm | |

| Mix_dum | −0.017 | 0.081 *** | ||

| (−0.72) | (3.61) | |||

| 0.000 | 0.002 *** | |||

| (0.31) | (4.11) | |||

| Constant | −5.495 *** | −1.872 *** | −5.477 *** | −1.935 *** |

| (−11.87) | (−3.46) | (−11.90) | (−3.60) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 4897 | 5468 | 4897 | 5468 |

| R-squared | 0.575 | 0.548 | 0.575 | 0.549 |

| industry/year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Panel C | Polluted = 1 | Polluted = 0 | Polluted = 1 | Polluted = 0 |

| Mix_dum | 0.079 *** | 0.034 | ||

| (2.74) | (1.63) | |||

| 0.002 ** | 0.001 ** | |||

| (2.20) | (2.53) | |||

| Constant | −3.527 *** | −4.692 *** | −3.616 *** | −4.762 *** |

| (−8.96) | (−15.94) | (−9.07) | (−16.24) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 3175 | 7190 | 3175 | 7190 |

| R-squared | 0.566 | 0.540 | 0.566 | 0.540 |

| industry/year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Panel D | ESG_dis = 1 | ESG_dis = 0 | ESG_dis = 1 | ESG_dis = 0 |

| Mix_dum | 0.064 * | −0.014 | ||

| (1.95) | (−0.50) | |||

| 0.002 * | 0.001 | |||

| (1.89) | (0.90) | |||

| Constant | −2.764 *** | −5.452 *** | −2.902 *** | −5.427 *** |

| (−5.53) | (−12.14) | (−5.85) | (−12.22) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 3175 | 7190 | 3175 | 7190 |

| R-squared | 0.566 | 0.540 | 0.566 | 0.540 |

| industry/year | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Esgdiv | Opaque | Esgdiv | Esgdiv | Opaque | Esgdiv |

| Opaque | 0.191 * | 0.183 * | ||||

| (1.81) | (1.74) | |||||

| Mix_dum | 0.057 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.056 *** | |||

| (3.11) | (2.98) | (3.06) | ||||

| 0.002 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.002 *** | ||||

| (3.52) | (3.53) | (3.45) | ||||

| Constant | −4.026 *** | 0.097 *** | −4.044 *** | −4.113 *** | 0.089 *** | −4.130 *** |

| (−15.58) | (3.83) | (−15.62) | (−15.97) | (3.51) | (−16.00) | |

| Observations | 9019 | 9019 | 9019 | 9019 | 9019 | 9019 |

| R-squared | 0.513 | 0.177 | 0.513 | 0.513 | 0.178 | 0.514 |

| year/industry | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Sobel | −0.005 *** (Z = −3.39) | −0.0002 *** (Z = −4.744) | ||||

| Goodman-1 | −0.005 *** (Z = −3.365) | −0.0002 *** (Z = −4.719) | ||||

| Goodman-2 | −0.005 *** (Z = −3.415) | −0.0002 *** (Z= −4.77) | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Esgdiv | ln_Human | Esgdiv | Esgdiv | ln_Human | Esgdiv |

| ln_Human | 0.035 * | 0.039 * | ||||

| (1.65) | (1.83) | |||||

| Mix_dum | 0.046 *** | −0.065 *** | 0.048 *** | |||

| (2.70) | (−3.95) | (2.82) | ||||

| 0.001 *** | −0.002 *** | 0.001 *** | ||||

| (3.11) | (−5.17) | (3.28) | ||||

| Constant | −4.360 *** | 8.769 *** | −4.667 *** | −4.428 *** | 8.883 *** | −4.775 *** |

| (−17.06) | (32.29) | (−14.66) | (−17.38) | (32.65) | (−14.95) | |

| Observations | 10,342 | 10,342 | 10,342 | 10,342 | 10,342 | 10,342 |

| R-squared | 0.546 | 0.422 | 0.546 | 0.546 | 0.427 | 0.546 |

| year/industry | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Sobel | −0.034 *** (Z = −8.98) | −0.001 *** (Z = −12.58) | ||||

| Goodman-1 | −0.034 *** (Z = −8.98) | −0.001 *** (Z = −12.57) | ||||

| Goodman-2 | −0.034 *** (Z = −8.99) | −0.001 *** (Z = −12.59) | ||||

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Esgdiv | Esgdiv |

| Mix_dum_DQ | −0.061 ** | |

| (−2.47) | ||

| Mix_ratio_DQ | −0.001 ** | |

| (−2.14) | ||

| Mix_dum | 0.246 *** | |

| (3.07) | ||

| 0.005 *** | ||

| (3.03) | ||

| DQ | 0.028 | 0.023 |

| (1.34) | (1.18) | |

| Constant | −4.159 *** | −4.180 *** |

| (−15.67) | (−16.05) | |

| Observations | 9019 | 9019 |

| R-squared | 0.514 | 0.514 |

| year/industry | YES | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X. Policy Implementation and Sustainable Governance in Chinese SOEs: A Study of Mixed-Ownership Reform and ESG Rating Divergence. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310576

Wang H, Sun Y, Wang X. Policy Implementation and Sustainable Governance in Chinese SOEs: A Study of Mixed-Ownership Reform and ESG Rating Divergence. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310576

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Hui, Yue Sun, and Xin Wang. 2025. "Policy Implementation and Sustainable Governance in Chinese SOEs: A Study of Mixed-Ownership Reform and ESG Rating Divergence" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310576

APA StyleWang, H., Sun, Y., & Wang, X. (2025). Policy Implementation and Sustainable Governance in Chinese SOEs: A Study of Mixed-Ownership Reform and ESG Rating Divergence. Sustainability, 17(23), 10576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310576