Bridging the Gap: Assessing Sanitation Practices and Community Engagement for Sustainable Rural Development in the King Sabatha Dalindyebo Municipality, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

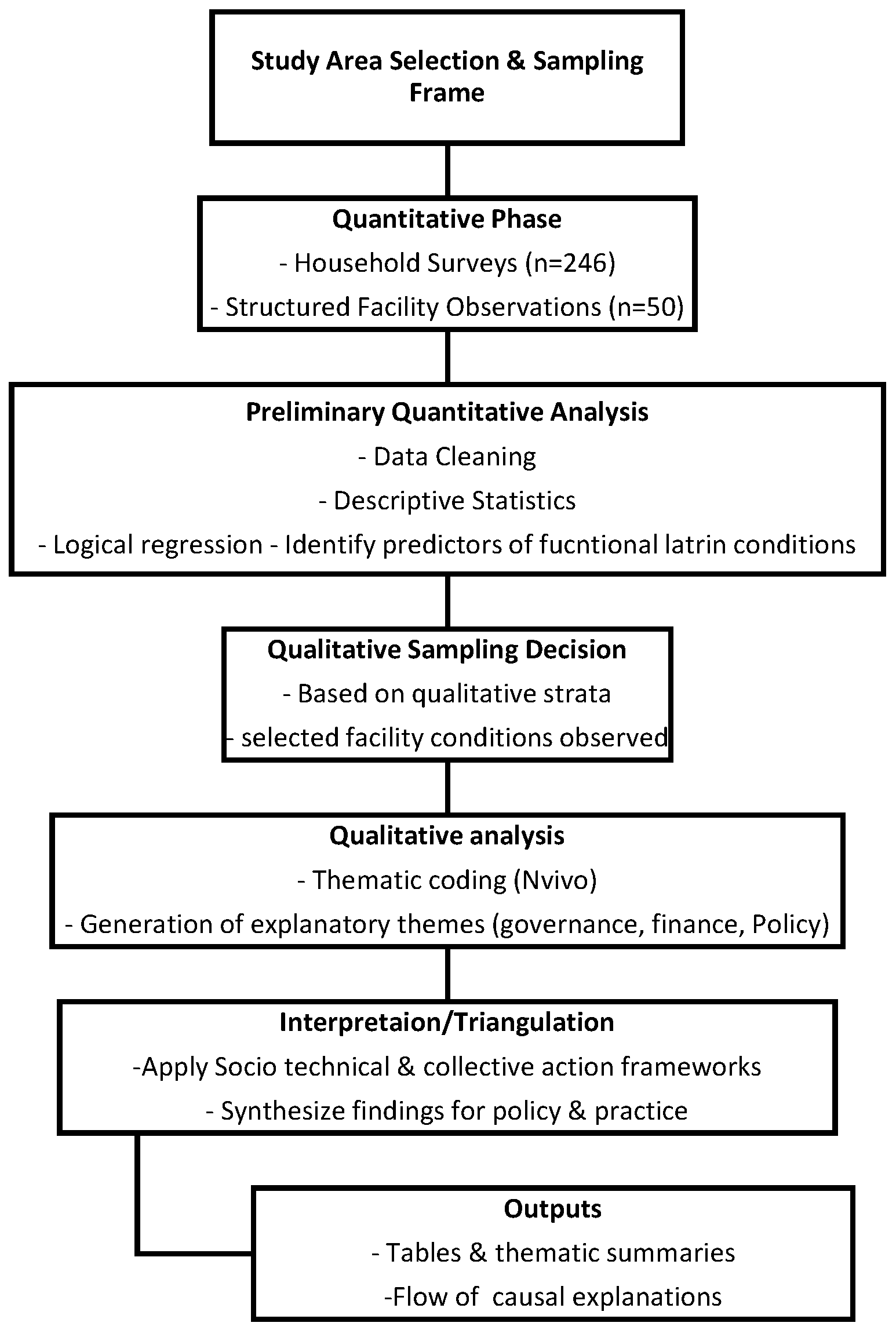

2.1. Research Design and Triangulation

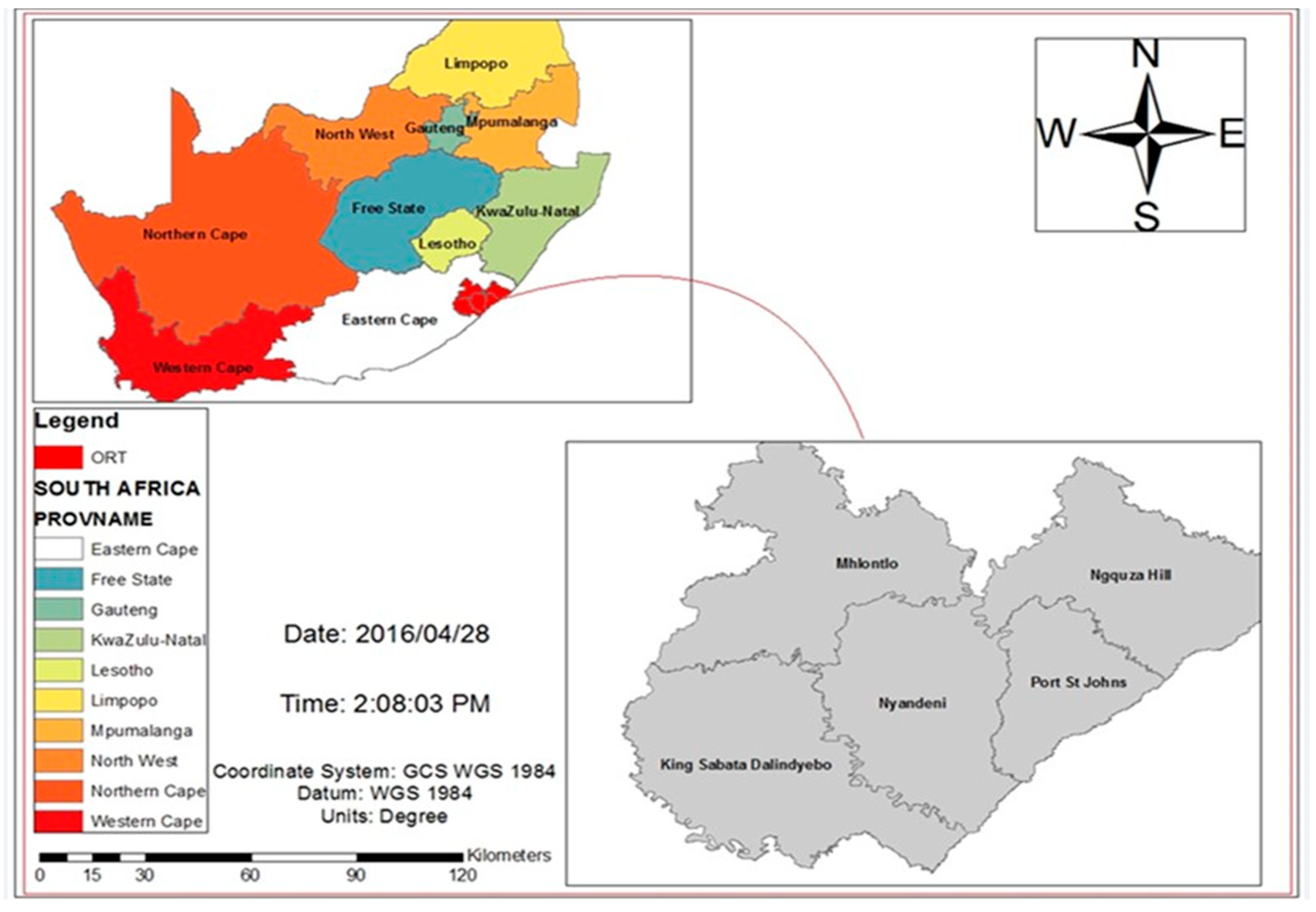

2.2. Study Area and Timing

2.3. Data Collection and Instruments

2.3.1. Sampling Strategy

2.3.2. Instrument Development and Reliability

2.4. Measurement of Variables

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethics Approval

2.7. Data Management and Quality Control

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Sanitation Systems

3.2. Facility Conditions and Maintenance

3.3. Hygiene and Water Infrastructure

3.4. Community Engagement in Sanitation Projects

3.5. Socio-Cultural and Economic Influences

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy, Demographics, and Tenure as Causal Drivers

4.2. Situating KSD in Sub-Saharan Africa

4.3. Generalizable Lessons

4.4. Policy and Practice Implications

4.5. Theoretical Contributions

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Funding for maintenance: Allocate a portion of capital grants for recurrent operation and maintenance to ensure repairs and pit-emptying services are accessible.

- Ward-level governance: Establish elected, gender-balanced WASH committees with delegated budgets and authority for site approvals, safety audits, and local contract management.

- Targeted subsidies: Implement a Smallholder Sanitation Fund to provide means-tested support for pit emptying and repairs for households earning below ZAR 3000 per month.

- Gender-sensitive design: Incorporate lockable doors, path lighting, and inclusive siting criteria into sanitation infrastructure standards.

- Environmental safeguards: Enforce a 30 m setback between new pits and water sources, supported by municipal GIS mapping and compliance monitoring.

Final Reflection

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Draft Household Survey Questionnaire–Rural Sanitation in KSD

- Study Title: Assessing the Sustainability of Household Sanitation in King Sabata Dalindyebo Local Municipality, Eastern Cape, South Africa

- Instructions to Respondent: This survey is confidential. Your honest responses will help improve sanitation services in your community. Please answer all questions as accurately as possible.

- Section 1: Household Demographics

- Household ID: _______

- Ward Name: _______

- Respondent Name (optional): _______

- Age of Respondent: _______ years

- Gender of Respondent: ☐ Male ☐ Female ☐ Other

- Highest Level of Education Completed:☐ No formal education☐ Primary school☐ Secondary school☐ Tertiary/College/University

- Household Income (monthly, ZAR): ☐ <1500 ☐ 1500–3000 ☐ 3001–5000 ☐ >5000

- Household size (number of members): _______

- Section 2: Sanitation Facilities

- Does your household have access to a sanitation facility? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Type of sanitation facility (check all that apply):☐ Ventilated Improved Pit (VIP) latrine☐ Pit latrine without ventilation☐ Flush toilet connected to sewer☐ Flush toilet with septic tank☐ Ecological sanitation (EcoSan) toilet☐ Other: _______

- How long has the facility been in use? _______ years

- Current condition of the facility:☐ Good (no major repairs needed)☐ Requires minor maintenance☐ Requires major repairs☐ Abandoned/not in use

- Who is responsible for maintenance?☐ Household members☐ Neighbourhood committee☐ Municipality☐ Other: _______

- Section 3: Use and Functionality

- How often do household members use the facility?☐ Always ☐ Sometimes ☐ Rarely ☐ Never

- If not always, why? (select all that apply)☐ Unsafe at night☐ Poor hygiene/odor☐ Broken or collapsed☐ Full/requires emptying☐ Other: _______

- Have you ever abandoned a pit or dug a new one? ☐ Yes ☐ No⚬ If yes, what was the main reason? __________________________

- Section 4: Affordability and Maintenance

- Approximate cost of routine maintenance (repairs, slab replacement, etc.): ZAR _______

- Is this cost affordable for your household? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Have you ever paid for pit emptying services? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- ⚬

- If yes, how much? ZAR _______

- Was this cost affordable? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Would your household benefit from a subsidy or small grant for sanitation maintenance? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Section 5: Community Engagement

- Are you aware of any ward-level WASH committee? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Have you ever participated in sanitation planning or maintenance activities? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- How would you rate community participation in sanitation-related decisions?☐ High ☐ Medium ☐ Low ☐ None

- In your opinion, what could improve sanitation sustainability in your community? __________________________

- Section 6: Health and Safety Perceptions

- Have any household members experienced illness related to poor sanitation in the past year? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- ⚬

- If yes, specify: __________________________

- Do you feel safe using the facility, especially at night? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Are there any gender-specific risks associated with sanitation facilities in your community? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- ⚬

- If yes, describe: __________________________

- End of Questionnaire

- Interviewer Notes:

- Observe the facility condition during the visit and record structural issues, ventilation status, slab integrity, and cleanliness.

- Assign a unique Household ID for linkage with facility observations.

Appendix B

- VIP Latrine Observation Checklist–King Sabata DalindyeboStudy Title: Assessing the Sustainability of Household Sanitation in King Sabata Dalindyebo Local Municipality, Eastern Cape, South AfricaInstructions to Observer: Please complete this checklist during the household visit. Observe objectively and record the status of each feature as accurately as possible.Section 1: Identification

- Household ID: _______

- Ward Name: ______

- Observation Date: _______

- Observer Name: ______

Section 2: Facility Type- Type of facility:☐ Ventilated Improved Pit (VIP) latrine☐ Pit latrine without ventilation☐ Flush toilet connected to sewer☐ Flush toilet with septic tank☐ Ecological sanitation (EcoSan) toilet☐ Other: _______

Section 3: Structural Condition- Pit integrity:☐ Intact ☐ Minor cracks ☐ Major cracks ☐ Collapsed/unsafe

- Slab condition:☐ Intact and level ☐ Cracked ☐ Broken or missing

- Foot-rest platforms:☐ Present and stable ☐ Damaged ☐ Missing

- Vent pipe:☐ Present and mesh intact ☐ Present but mesh damaged ☐ Missing

- Superstructure (walls/roof):☐ Good ☐ Needs minor repairs ☐ Needs major repairs ☐ Abandoned

Section 4: Hygiene and Cleanliness- Cleanliness of floor:☐ Clean ☐ Some fecal matter/wetness ☐ Dirty/unsafe

- Evidence of recent emptying or maintenance: ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Odor level: ☐ Minimal ☐ Moderate ☐ Strong

- Presence of flies or other vectors: ☐ None ☐ Some ☐ Many

Section 5: Accessibility and Safety- Accessibility:☐ Easy access ☐ Some obstruction ☐ Difficult to access

- Lighting (night-time use): ☐ Adequate ☐ Poor ☐ None

- Door functionality: ☐ Lockable ☐ Non-lockable ☐ Missing

- Pathway condition: ☐ Safe and stable ☐ Uneven or slippery ☐ Unsafe

Section 6: Usage Indicators- Signs of regular use (footprints, wetness, supplies): ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Abandonment indicators (overgrown, unused, damaged): ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Number of users (estimate if possible): _______

Section 7: Environmental Risk- Distance to nearest water source (meters): _______

- Evidence of leakage or pit overflow: ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Nearby vegetation or drainage issues: ☐ Yes ☐ No

Section 8: Additional Notes- Any unusual observations: __________________________

- Recommendations for follow-up or repairs: __________________________

End of Checklist

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Sanitation and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514705 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene 2000–2017: Special Focus on Inequalities; UNICEF/WHO: New York, NY, USA, 2019; 140p, ISBN 978-92-415-1623-5. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516235 (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- WaterAid; Remissa Mak. Practical Guidance to Address Gender Equality While Strengthening Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Systems. 2020. Available online: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/sites/g/files/jkxoof256/files/practical-guidance-to-address-gender-equality-while-strengthening-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-systems.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey 2020; Stats SA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182020.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Augsburg, B.; Rodríguez-Lesmes, P. Sanitation dynamics: Toilet acquisition and its economic and social implications in rural and urban contexts. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2020, 10, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Water Affairs. Guidelines for Pit-Latrine Construction and Maintenance; DWA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201709/41100gon982.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Ntlangula, L.; Xelelo, Z.; Chitongo, L. Evaluating Enforcement Strategies for Curbing Illegal Waste Dumping: A Case Study of King Sabata Dalindyebo Local Municipality, South Africa. IRASD J. Manag. 2025, 7, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zembe-Mkabile, W.; Noble, M.; Wright, G. Multiple Deprivations in the Eastern Cape. In Reflections from the Margins: Complexities, Transitions and Developmental Challenges—The Case of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa; African Sun Media: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2021; pp. 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, J. Making dysfunctional municipalities functional: Towards a framework for improving municipal service delivery performance in South African municipalities. Commonw. J. Local Gov. 2024, 29, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Putting sanitation and wastewater management centre stage. In Global Report on Sanitation and Wastewater Management in Cities and Human Settlements; United Nations Human Settlements Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; pp. 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukes, L.S.; Schmidt, S. Manual emptying of ventilated improved pit latrines and hygiene challenges—A baseline survey in a peri-urban community in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2020, 32, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubatsi, J.B.; Wafula, S.T.; Etajak, S.; Ssekamatte, T.; Isunju, J.B.; Kimbugwe, C.; Olweny, M.; Kayiwa, D.; Mselle, J.S.; Halage, A.A.; et al. Latrine characteristics and maintenance practices associated with pit latrine lifetime in an informal settlement in Kampala, Uganda. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2021, 11, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson-Hebert, M.; Rosemarin, A.; Winblad, U. Ecological sanitation. In The Business of Water and Sustainable Development; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellet, M.; Tushabe, W. Ecosan Toilets in a Barrel; Ecosan Toilets in a Barrel: Low-Cost Container Compost Toilets for Households in Camps and Settlements; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.practicalactionpublishing.com/book/3034/ecosan-toilets-in-a-barrel (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Barton, G.H. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (3rd Edition; International Student Edition) by John W. Creswell & Vicki L. Plano Clark. Cogn. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 1, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotten, S.R.; Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Mixed Methodology: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Contemp. Sociol. 1999, 28, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Triangulation in Data Collection. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; Sage Publishing: London, UK, 2018; pp. 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J. Urban community-led total sanitation: A potential way forward for co-producing sanitation services. Waterlines 2016, 35, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, S.J.; Forster, T. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene in Post-Emergency Contexts: A Study on Establishing Sustainable Service Delivery Models; Oxfam: Nairobi, Kenya; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugard, J. Sanitation in South Africa. In The Right to Sanitation in India; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thole, B. Water and Sanitation Poverty in Informal Settlements of Sub-Saharan Africa. In Clean Water and Sanitation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phaswana-Mafuya, N. Health aspects of sanitation among Eastern Cape (EC) rural communities, South Africa. Curationis 2006, 29, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevenhörster, P. Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, Cambridge 1990. In Schlüsselwerke der Politikwissenschaft; Springer VS: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: A review of criticisms and elaborations of the Multi-Level Perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 39, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overview of Sanitation Systems | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Value/Description | Statistic/Note |

| VIP latrine ownership | 63.4% (95% CI 57.4–69.4) | χ2(2) = 46.8; p < 0.001 |

| Unimproved pit usage | 19.6% (95% CI 13.9–25.3) | — |

| Open defecation | 7.3% (95% CI 4.0–10.6) | OR = 4.1 (1.7–9.9); p < 0.01 |

| Flush/septic system use | 8.1% (95% CI 4.1–12.1) | OR = 3.2 (1.8–5.6); p < 0.001 |

| Communal facility uses | 1.6% (95% CI 0.0–3.2) | — |

| Settlement-type variation (water-based vs. pit-based) | Formal 28% vs. Traditional < 5% | χ2(2) = 46.8; p < 0.001 |

| Facility Conditions and Maintenance | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Value/Description | Statistic/Note |

| VIPs in good condition | 22% (95% CI 10.9–33.1) | — |

| VIPs needing major repair | 58% (95% CI 44.7–71.3) | — |

| Abandoned VIPs | 20% (95% CI 8.3–31.7) | — |

| Mean VIP age | 5.6 years (SD 2.3) | — |

| Household-paid maintenance | 86.2% | — |

| Cannot afford pit-emptying (ZAR 1500–2500 per visit) | 78% (95% CI 73.7–84.3) | χ2(1) = 39.2; p < 0.001 |

| Dug a new pit when full (environmental/public health risk) | 64.8% | — |

| Hygiene and Water Infrastructure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Value/Description | Statistic/Note |

| Any communal or yard tap | 68% (95% CI 62.2–73.8) | — |

| Reliable water supply (≥95% days) | 28% (95% CI 22.4–33.6) | OR = 2.5 (1.6–3.9); p < 0.01 |

| Functional handwashing facility (water + soap) | 35% (95% CI 29.2–40.6) | — |

| Handwashing facility present but no consumables | 41.9% (95% CI 35.7–48.1) | — |

| No handwashing facility | 23.1% (95% CI 18.0–28.4) | — |

| Community Engagement in Sanitation Projects | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Value/Description | Statistic/Note |

| Attendance at IDP meetings | 36.7% (95% CI 30.9–42.5) | — |

| Never participated in sanitation planning | 32.1% (95% CI 26.7–37.5) | — |

| Invitation to men vs. women | 49% vs. 24% | χ2(1) = 21.5; p < 0.001 |

| Effect of education on participation | OR = 1.4 (95% CI 1.1–1.8); p < 0.01 | — |

| Level of community power (Arnstein’s ladder) | Consultation | — |

| Socio-Cultural and Economic Influences | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Value/Description | Statistic/Note |

| Cited cost as barrier to maintenance | 79% (95% CI 73.7–84.3) | χ2(1) = 33.7; p < 0.001 |

| Abandoned-pit households earning less than ZAR 3000 per year | 88% | — |

| New pits ≤ 30 m from streams/wells | 52% (95% CI 38.3–65.7) | — |

| Qualitative themes | Financial barriers; Water-table risks; Gender/safety; Institutional disconnect; Cultural acceptance | Thematic analysis of interviews/FGDs |

| Cited cost as barrier to maintenance | 79% (95% CI 73.7–84.3) | χ2(1) = 33.7; p < 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buso, S.; Okello, T.W. Bridging the Gap: Assessing Sanitation Practices and Community Engagement for Sustainable Rural Development in the King Sabatha Dalindyebo Municipality, South Africa. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10565. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310565

Buso S, Okello TW. Bridging the Gap: Assessing Sanitation Practices and Community Engagement for Sustainable Rural Development in the King Sabatha Dalindyebo Municipality, South Africa. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10565. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310565

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuso, Siyakubonga, and Tom Were Okello. 2025. "Bridging the Gap: Assessing Sanitation Practices and Community Engagement for Sustainable Rural Development in the King Sabatha Dalindyebo Municipality, South Africa" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10565. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310565

APA StyleBuso, S., & Okello, T. W. (2025). Bridging the Gap: Assessing Sanitation Practices and Community Engagement for Sustainable Rural Development in the King Sabatha Dalindyebo Municipality, South Africa. Sustainability, 17(23), 10565. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310565