3. Kielce and Surroundings

We associate the Świętokrzyskie region with one of the oldest mountains in Europe—the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, as well as with Kielce—the Castle Hill with its cathedral and palace, Chęciny—the Royal Castle, or the “Raj” Cave. The Świętokrzyskie region has no shortage of protected nature and exceptional monuments or original modern architecture set in the natural terrain. The capital of the Świętokrzyskie Province itself, Kielce is an exceptional Polish city in terms of greenery, especially protected greenery. There are as many as five nature reserves within the boundaries of Kielce, and a large area of the city is under nature protection as the Chęciny and Kielce Landscape Park. This is a total area of approximately 6410.84 hectares out of the 10,945 hectares of the city, or 58.53% of the protected landscape area [

5], which is 6% less compared to 2014 [

6]. Kielce boasts numerous green spaces, which are considered its main asset. Kielce’s nature conservation and development policy is based on preserving the city’s abundant green spaces and maintaining proximity to nature, which is intended to improve the quality of life for its residents. At the same time, the city strives to develop by utilising these resources for recreational purposes, as well as supporting sustainable development and investment. Kielce is also located in the historically and naturally unique area of the Świętokrzyski Geopark, listed in 2021 on the UNESCO World Geoparks Network [

5], and is therefore often referred to as the “largest open-air museum of geology”.

Of the five reserves, four are geological reserves of inanimate nature; the locations of the reserves can be seen in

Figure 2. These include the “Kadzielnia” Reserve located in the city centre, another in the south-eastern part of the city “Wietrznia”, another in the western part of Kielce—“Ślichowice” and “Biesak- Białogon” in the south-western part of Kielce, at the foot of the Kamienna Góra Hill. “Karczówka” is the fifth reserve—a landscape reserve. These unique sites exemplify the symbiosis of the city and nature, with the urban fabric and architectural objects blending into the hand of naturally shaped areas and the reclaimed areas of former quarries and mines.

The nature reserves in Kielce are a glimpse of the Świętokrzyskie region, which is rich in unique natural features. Currently, there are 77 nature reserves in the region, with 7 more planned. Nature in this region is in symbiosis with human habitats and the architecture that constitutes them. Protected nature drives development in the Świętokrzyskie region not only in terms of tourism but also as an attractive place for investment and residence. People who value contact with nature often choose this region and the city of Kielce as a place to live.

5. Examples of Symbiosis and Reclamation in Europe and Poland

Man’s symbiosis with nature is important because nature, and the nature that comprises it, is a fundamental part of human life; “because humans evolved in nature, it is where we feel most comfortable, even if we do not always realise it”, according to the theory of Yoshifumi Miyazaki, a physical anthropologist and deputy director of the Centre for Health Environment and Field Science at Chiba University in Tokyo [

14]. Actions contributing to the return to nature, especially of degraded areas, include reclamation.

Most of the former mines have been subjected to a reclamation process in order to restore the original nature and use values of areas damaged by human economic activity. Both abroad [

15,

16,

17] and in Poland [

18,

19,

20], there are many examples of reclamation (usually after mining operations). The predominant examples of reclamation in forestry and water-recreational directions include:

A kaolin mine site near the town of Bodelva, (Cornwall County, UK). In the 1990s, an area of approximately 15 ha left over from an open-cast kaolin mining operation completed in the 19th century was reclaimed. The Eden Project was established in 2001, but the idea and the beginning of its realisation date back to 1996, and it serves as a botanical garden and ecological institution. It is one of the largest natural complexes created in a disused quarry. The area contains a structure built within it, composed of light-transmitting domes, where plants from all parts of the world are cultivated. The site has a natural, educational, and tourism function [

21].

The site of the decommissioned Golpa-Nord lignite mine in Gräfenhainichen, Germany, where an open-cast lignite mine operated from 1964 to 1991. After the closure of the mine, the site was transformed into a landscaped park opened in 2000. Ferropolis—the ‘iron city’ which serves as an industrial museum for mining machinery. The area is being developed for tourism and is a popular venue for musical, sporting, and cultural events [

22].

The site of the Prosper-Haniel coal mine in Bottrop, Germany. A mine was established in the area in 1863 and operated continuously until 2018. The main idea behind the reclamation of the area is the creation of a place to serve as a religious centre, with a Stations of the Cross and a museum of mining equipment, as well as the introduction of numerous tree and shrub plantings; the area is being developed for recreation and leisure [

23].

A clay mine site in Grossbettenrain, Germany. The working was operated by a clay tile manufacturer between 2000 and 2016. The planned reclamation work started in 2010. The site was divided into two zones—agricultural use (afforestation and fruit tree planting) and ecological use (partly from a meadow and wooded area) [

24].

Areas of former sulphur extraction by borehole mining—the “Jeziórko” sulphur mine (near Tarnobrzeg, Podkarpackie province) and the “Jeziórko” mine exploited sulphur deposits by underground smelting in 1967–2001. An area of approximately 1300 ha has been rehabilitated, where a water-forest-meadow ecosystem has been created that serves a recreational function for local residents [

25].

Areas left by open-cast sulphur mining [

26], former Sulphur Mine “Machów”, near Tarnobrzeg, Subcarpathian Province. The Machów mine exploited sulphur deposits using the open-cast method between 1969 and 1992, after which a working of about 560 ha and a depth of 110 m was reclaimed. As a result of the activities, a place with a recreational and leisure function for residents and tourists has been created—a water-forest-meadow ecosystem [

27].

A former limestone quarry site in the Kraków area of Krzemionki, now Bednarski Park. A limestone quarry had been located in the area of the present park since medieval times; the quarry was closed at the end of the 19th century, and the park was opened in 1896. The park area was modernised in the following years, and the work was carried out in stages. The space is made up of ‘gardens’, varied in layout and style, and contains numerous plantings integrated into the quarry landscape. A place with a leisure and recreational function for residents and tourists has been created [

28,

29].

The area formerly occupied by a limestone quarry in Krakow is now the Zakrzówek Lagoon and Park. The Zakrzówek quarry was established shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War and was finally closed in 1992. The Zakrzówek Lagoon was created after the limestone quarry was flooded in 1992; the entire park site, including the lagoon and adjacent green areas, covers about 100 hectares, and in this area, there is a place with recreational and leisure functions for residents and tourists [

30].

Reclamation is of great importance in many respects. In addition to the huge natural role, as can be seen from the examples, it can also be seen that cultural considerations also play a special role in the reclamation process [

16]. And it should be noted that the management of old quarries is of great importance for the protection of geological heritage [

30].

6. Kielce and Surroundings—Examples of Reclamations

Kielce and its surrounding areas represent one of the earliest and most prominent examples in Poland of the reclamation of post-mining landscapes, successfully transformed into nature reserves, an amphitheatre, and educational centres. It is here that all the reserves were created at sites of earlier mineral exploitation and are the most important historical remains of former quarries operating since the 16th century [

31]. Due to the exceptional natural values, the variety of rock geological formations, and the remains of disused quarries, it was decided to protect these areas in order to prevent them from losing their exceptional values through destruction. These areas have also been of interest in terms of reclamation activities [

32]. Over time, reclaimed areas under protection have been revitalised with the addition of architecture related to cultural or educational functions. As a result, they fit well into the urban space and are now recreational areas [

33].

In 1952, the first geological reserve in Poland, the “Ślichowice” Rock Reserve in Kielce, was established and named after Jan Czarnocki. The reserve was established on the site of two Devonian limestone quarries quarried here in the first half of the 20th century, in the interwar period. A rocky perch of 0.55 ha separating the two workings west and east of the disused quarry was protected; mining at the east quarry ceased in 1968 [

32]. Here, geological profiles were exposed during mining in the form of two tectonic folds—an overthrown one and a recumbent one—serving as a reminder of the tectonic movements known as the Variscan [

33]. In the Ślichowice Reserve, there is an emerald lake that was created at the bottom of a rock excavation. There is also an emerald lake in the “Kadzielnia” Reserve (pow. 0.6 ha), where exploitation of Devonian limestone began in the 18th century and the quarry was closed in the 1960s. In 1931, the summit rock outcrop known as “Skała Geologów” (295 m above sea level) was protected, and the inanimate nature reserve was established in 1962. The “Biesak-Białogon” reserve was created in 1981. The site comprises just over 13.04 hectares of former quartzite sandstone quarry with surrounding woodland and a small reservoir [

27]. The largest reserve with an area of 17.59 hectares is “Wietrznia”, which includes three former quarries: “Wietrznia”, “Międzygórz” and “Esten Międzygórz”. This post-mining area is the result of the mining of the Upper Devonian limestone deposit, which began in the 19th century and was completed in 1974 [

34]. The “Wietrznia” nature reserve named after Zbigniew Rubinowski was established in 1999 and protects one of the longest profiles of the Upper Devonian in Poland. Another reserve within the city limits of Kielce, since the second half of the 20th century, is Karczówka (336 m above sea level), with an area of 26.37 ha. Although the site is best known for its St. Charles Borromeo Church, built between 1624 and 1631, it is also known for its former convent. Charles Borromeo Church and the monastery of the former Fr. Bernardines, since 1956 occupied by the Pallottines, are located on a hill that was formerly a mining area. You can see many traces of miners working here since the late Middle Ages. Valuable ores were mined at the site, primarily deposits of galena [

35]. In 1933, the Polish Forestry Directorate recognised Karczówka as a nature reserve, while in 1953 a landscape reserve was established on an area of 26.62 ha, which lies only 4 km from the centre of Kielce. Inactive quarries are also located on the northern slopes of Malik Hill, the site of the aforementioned ‘Paradise’ Cave.

Most of the reserves, such as “Biesak-Białogon”, are not developed for tourism; however, designated hiking trails have been established to allow visitors to explore the area. In some reserves, such as the “Kadzielnia” or more recently the “Wietrznia” Reserve, beautifully integrated facilities have been designed and built, making use of and highlighting the terrain and natural values of the area.

7. The Symbiosis of Architecture and Protected Nature: Examples in and Around Kielce

Reclamation activities, especially those with a naturalistic focus, combined with cultural, educational, and recreational directions, lead to the extraction of natural values and bring man back closer to nature. The result is a unique symbiosis of nature and man, combined with architecture that is skilfully integrated into the area and brings out its qualities. One of the best examples of the symbiosis between architecture and protected nature is in Kielce and its surroundings.

Looking at Kielce’s history dating back to the Middle Ages and the development of the city, which has been linked for centuries to the extraction of ores, it can be said that the city was formed on the site of former quarries. Following the cessation of their exploitation, these areas were subjected to land reclamation and protection measures. As a result of this process, many nature reserves were established alongside which the urban development of the growing city emerged, thus allowing the city to live in symbiosis with nature from its inception.

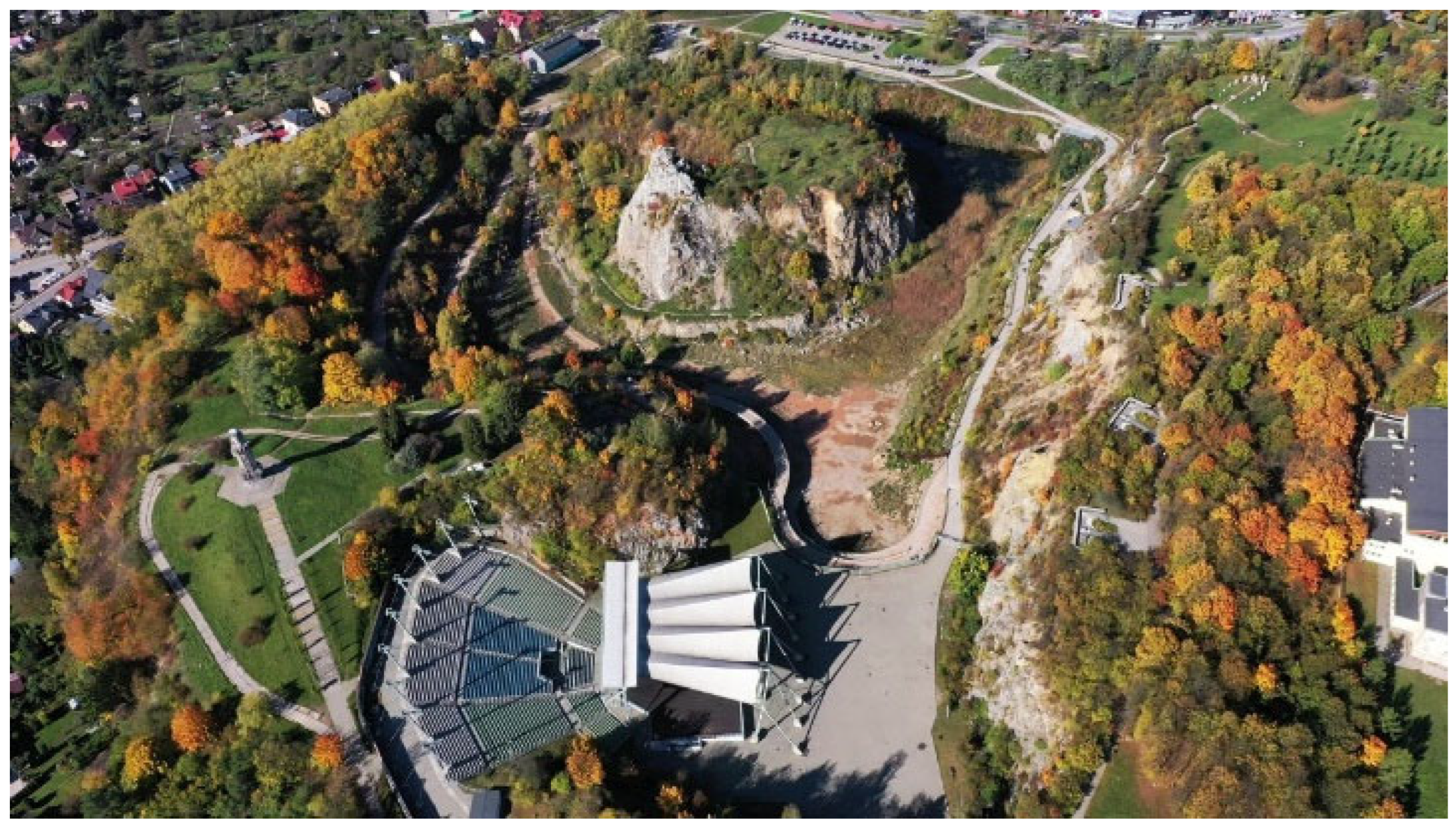

An excellent example of the symbiosis of nature and urban fabric is the “Kadzielnia” Nature Reserve located in the heart of Kielce. The landscape of “Kadzielnia” has been shaped by centuries of limestone mining. As early as the 1820s, when plans were made to create a park in Kielce, it was intended to dedicate a vast complex of land including Kadzielnia for recreation [

36]. However, it was only the protection of the area, starting with the Geologists’ Rock, and the reclamation of the former mine area since the 1960s that made it a symbol of Kielce’s renewal. The area underwent additional regeneration in the 1970s, during which the site—shaped by human activity—was creatively transformed by designing an amphitheatre on its southeastern side and on the north side of the emerald lake, which originally surrounded the Geologists’ Rock formation on three sides. The first amphitheatre on Kadzielnia, designed by architect Jan Żak, was opened in 1971 during the celebration of the Nine Centuries of Kielce (

Figure 5a,b). The stage at the time was used not only as a concert stage but also as a summer cinema. “Kadzielnia”, thanks to its cultural function, was very popular and frequented by residents. The amphitheatre is currently in shape after being rebuilt between 2008 and 2010. The facility was enlarged and upgraded, with the addition of a fixed canopy over the stage and a folding canopy over the auditorium. The stage is the largest in Poland at more than 1250 m

2. The main entrance for spectators is located on Legionów Avenue, while performers and staff have a separate, conflict-free access route from the Krakowska Street. Despite the large scale of the building, the “stage among the rocks” fits perfectly into the site found after the excavations (

Figure 6), and artists appreciate the venue’s unique atmosphere and acoustic qualities. The architectural form and function do not interfere with the perception of the qualities of the reserve; in fact, they emphasise them, as do the other attractions that were introduced during the recent revitalisation of the area (between 2014 and 2020). Thanks to the protection, but above all the reclamation and revitalisation of the site, today it is a place where history meets the present, and nature meets culture and architecture.

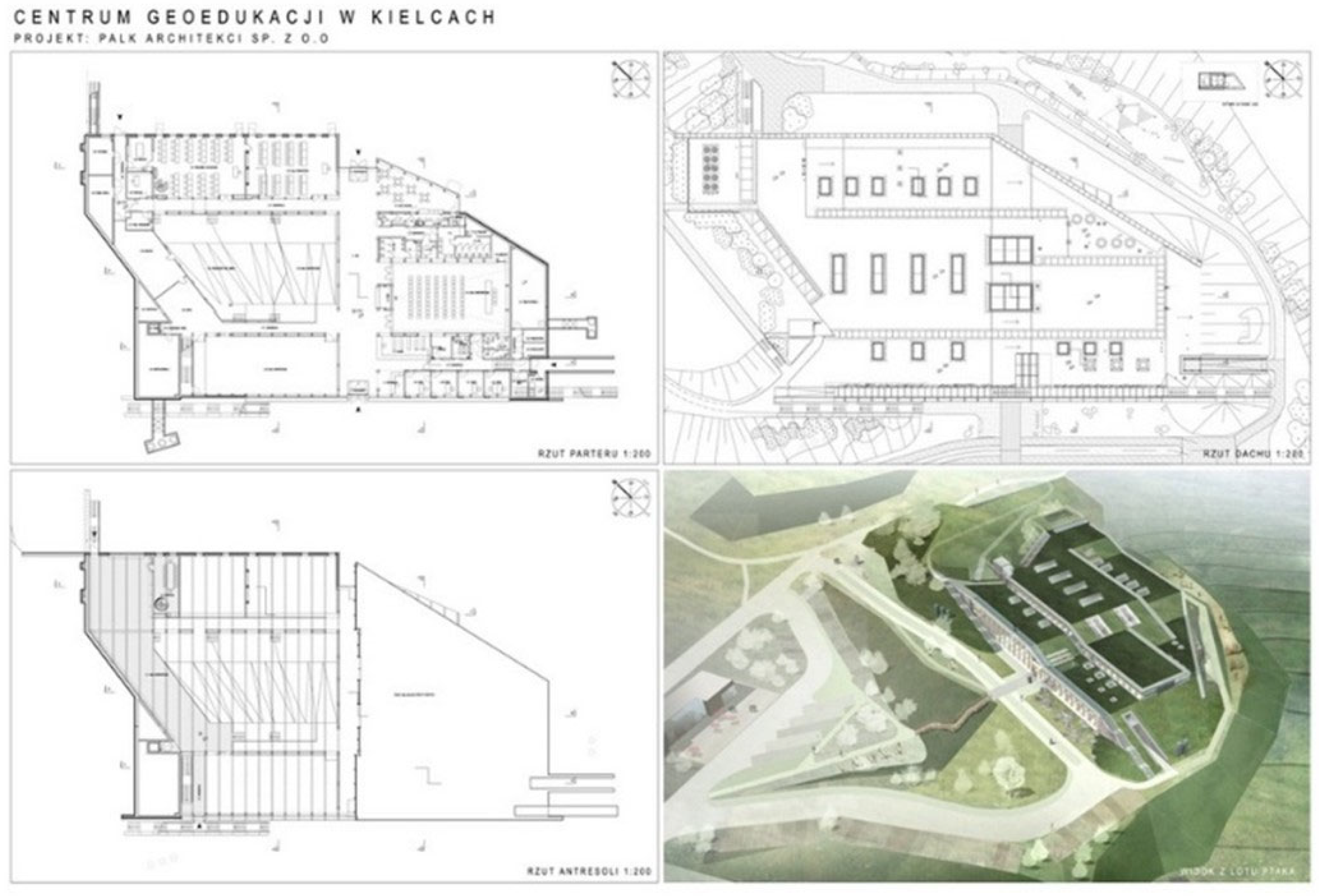

The “Wietrznia” Nature Reserve named after Zbigniew Rubinowski is the largest reserve in the city. Here we can “read the history of the Earth” mainly from the Devonian period, whose rock wall is the longest geological section in Poland (over 800 m long). There are a few viewpoints and tracts on the edge of the Wietrznia Nature Reserve. There is also a 60-metre-long cave with rich flowstone decoration. Numerous landscape and historical values led to the creation of the Center for Geo Education—Geonatura Kielce on the reserve in 2011, according to a design concept selected in a national architectural competition (

Figure 7). The architectural studio PALK Architekci Sp. z o.o. designed a modern glazed building, perfectly integrated into an area shaped by nature and man in the course of exploitation, which emphasises the protected qualities of the surroundings. The building was integrated into the landscape through its unusual shape and the use of construction materials such as local stone, extensive glazing, and greenery, including on the roof (

Figure 8a,b). The architecture of this building is an extension of the natural landscape, not its dominant feature. The structure also features a functional and uniquely designed interior, dominated by stone and sustainable wood. It is a venue for permanent and temporary exhibitions on geological topics, as well as for thematic workshops.

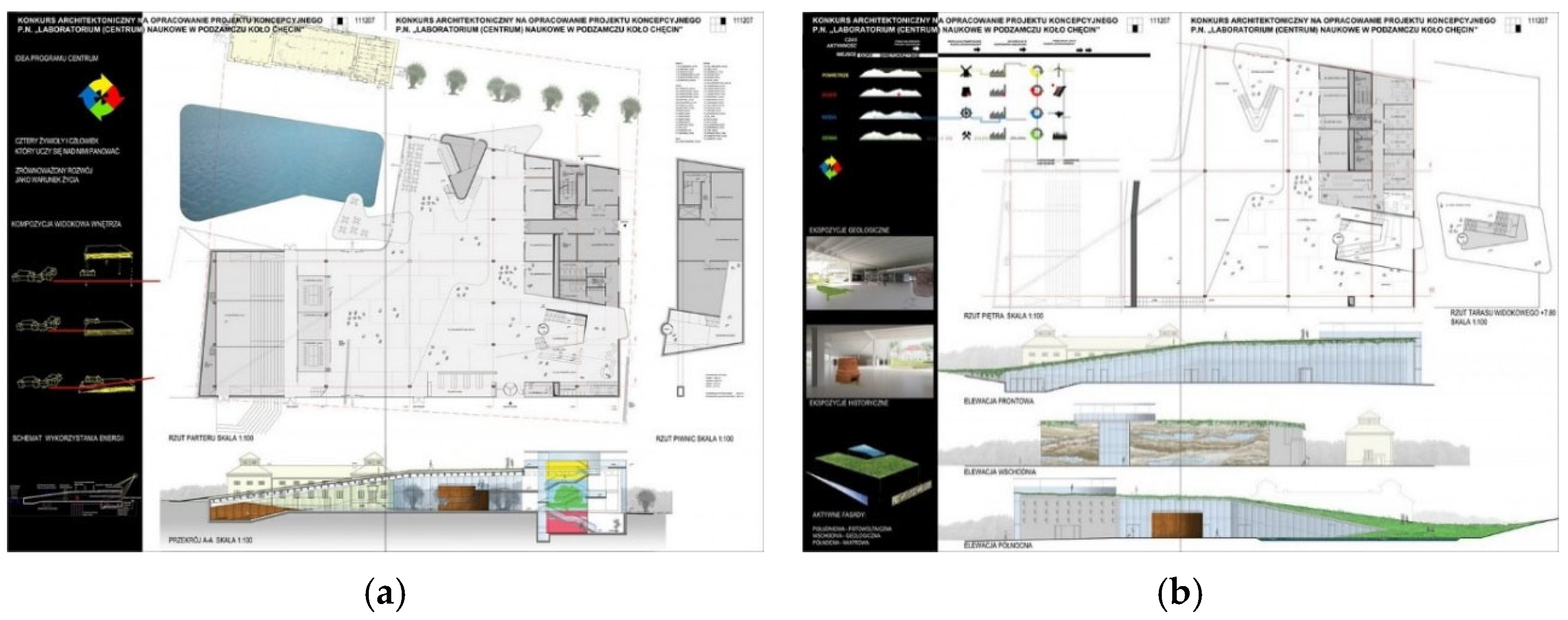

Another example of modern architecture perfectly integrated into the terrain and landscape is the Leonardo Da Vinci Science Centre in Podzamcze Chęcińskie (2011, 2013–2014). The facility was built on the model of the Copernicus Science Centre in Warsaw to create a place for awakening science in the community. The modern building was constructed as part of the revitalisation of the site of the former agricultural school complex, together with a fortified manor house built in the 17th century for Jan Branicki [

42]. The authors of the project that won the concept competition, eM4.Pracownia Architektury. Brataniec, designed an original architecture, well-suited to the 21st century, while at the same time keeping it within the landscape and cultural context (

Figure 9a,b). The main objective was to create a concept that meets the conservation and landscape considerations for the form of the building. Therefore, the contemporary architectural form has been adapted to the existing spatial layout of the site by using local building material and glazing that reflects the surroundings and de-materialises the volume (

Figure 10a). The single-space interior provides ample opportunity to utilise the facility. The connection between the centre, the palace, and the open landscape is provided by a sloping roof introducing the visitor from the grounds to a vantage point located on the roof of the building. The palace (

Figure 10b), which had existed here since the 17th century, was renovated and adapted to its new function. The historic structure is reflected in the glazing of the new building, thus connecting history with the present.

8. Social Research—Analysis of Survey Results

8.1. Aim and Research Objectives

The aim of this social research was to examine the level of environmental awareness among the residents of the city of Kielce and the Świętokrzyskie region, as well as to determine how they perceive the relationship between nature and architecture within the concept of sustainable development. The study also aimed to identify the degree of knowledge regarding local nature reserves and to assess the perceived importance of the symbiosis between nature and architecture in the urban context.

The following research questions were formulated:

What is the level of knowledge of Kielce residents and inhabitants of the Świętokrzyskie region regarding local forms of nature protection?

How do residents perceive the relationship between architecture and the natural environment?

Do residents believe that harmony between nature and architecture exists in Kielce?

Which demographic, educational, and spatial factors influence this perception?

Based on a literature review and the conceptual framework of sustainable development, the following research hypotheses were proposed:

H1. Residents of Kielce demonstrate a relatively high level of environmental awareness; however, their knowledge about local forms of nature protection is fragmentary.

H2. Most respondents consider the protection of nature reserves important but perceive it as insufficient at the local level.

H3. The perception of the symbiosis between nature and architecture is positively correlated with education level and place of residence (urban vs. suburban areas).

These are local studies designed to show that activities related to reclamation and nature conservation are important for the community and serve to create an urban environment in symbiosis with nature.

8.2. Research Methodology

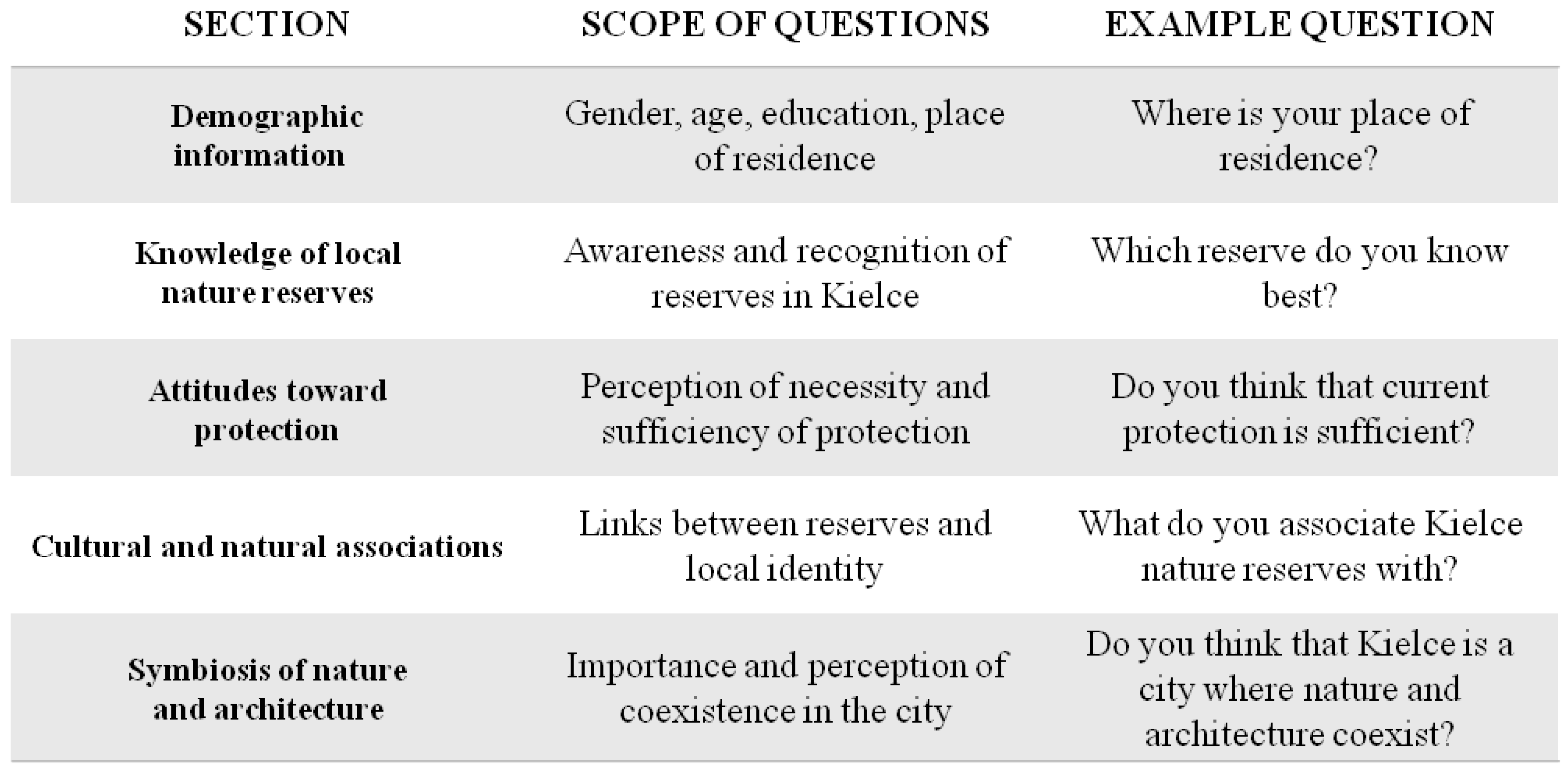

The research was conducted using an online questionnaire distributed via Google Forms between April and May 2025. The survey consisted of 18 closed-ended questions concerning the knowledge of nature reserves, perceptions of their function, environmental attitudes, and the perceived importance of the integration—symbiosis—between nature and architecture. The table below presents a summary of the questionnaire structure, as shown in

Figure 11.

The questionnaire was disseminated through social media platforms (including local Kielce community groups and Świętokrzyskie regional forums), allowing for a broad and diverse sample. The sampling method was purposive with random elements, encompassing both city residents and individuals from outside the administrative borders of Kielce, including tourists visiting the region.

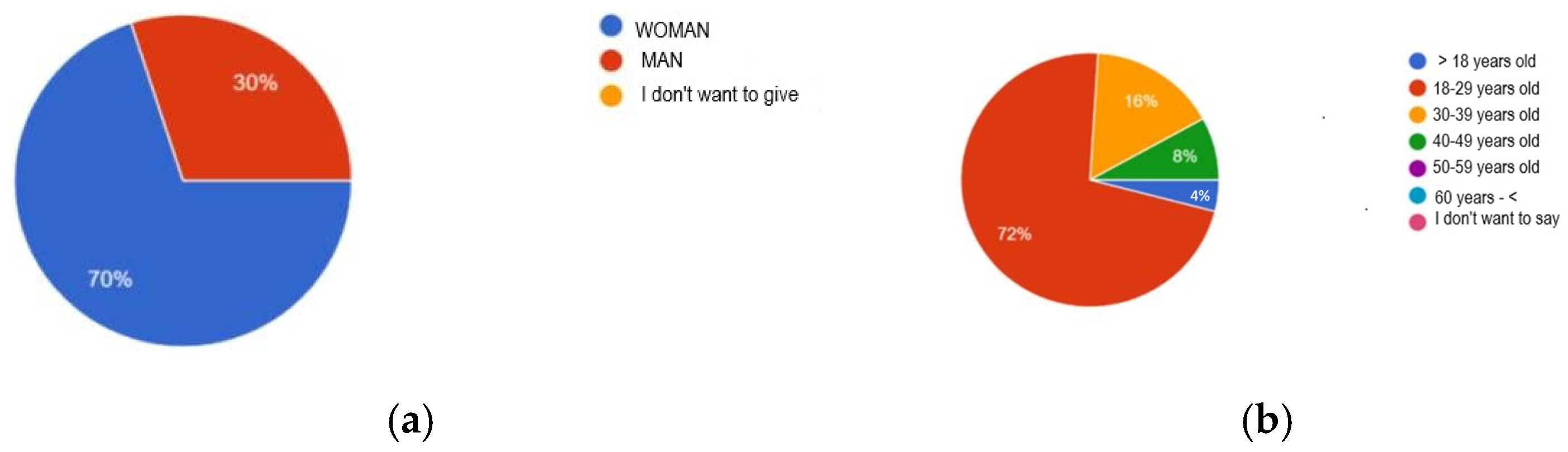

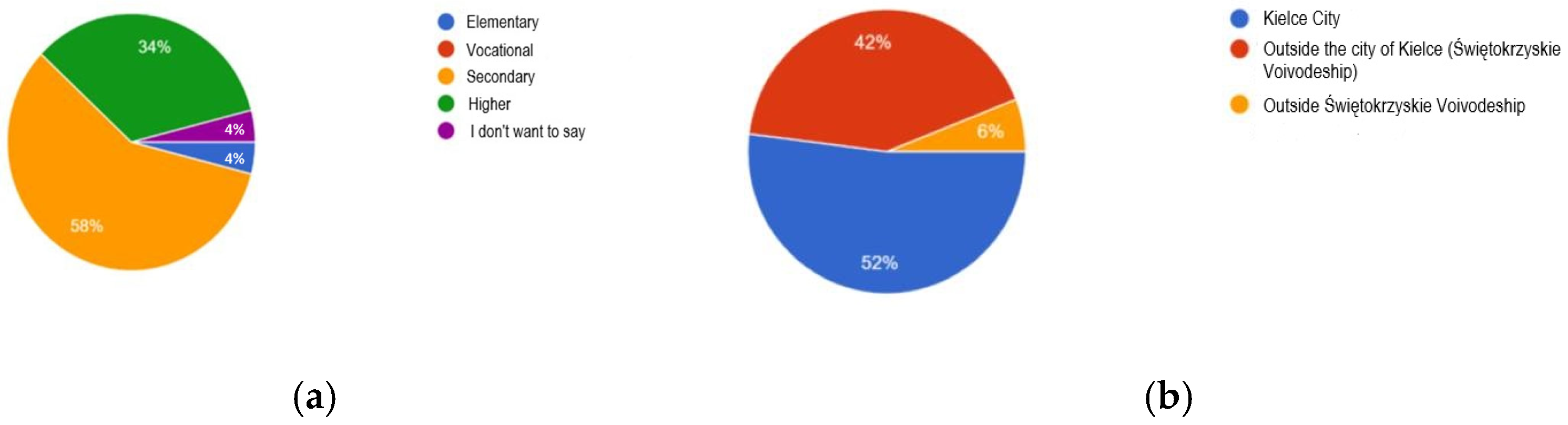

A total of 50 participants took part in the study—70% women and 30% men—as shown in

Figure 12a. The respondents were divided into six age groups, with the majority aged 18–29 years (72%), and the smallest group under 18 years old (4%), as shown in

Figure 12b.

Most respondents held secondary (58%) or higher education (34%), indicating a relatively high educational level within the sample, as shown in

Figure 13a. The majority lived within the city of Kielce (52%), followed by those living in the Świętokrzyskie region outside the city boundaries (42%), while 6% resided outside the region, as shown in

Figure 13b.

8.3. Research Results and Interpretation

8.3.1. Environmental Awareness and Knowledge of Nature Protection

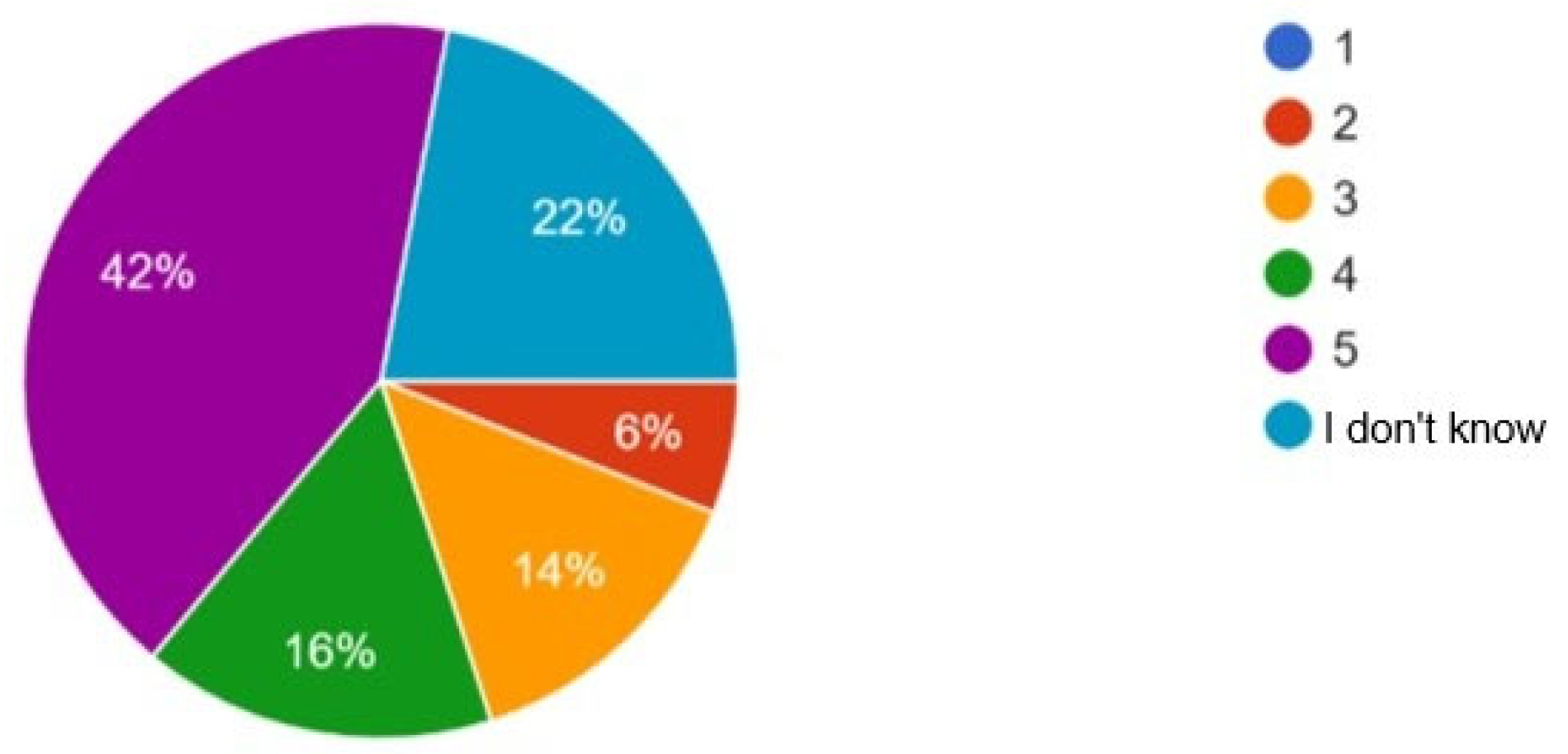

A vast majority of respondents (80%) were aware that the city of Kielce contains green areas protected as inanimate and landscape nature reserves. This finding suggests a generally positive level of ecological awareness among residents, likely resulting from the city’s rich natural landscape and its visibility in local media and public spaces.

However, less than half (42%) could indicate the exact number of nature reserves within the city limits. This points to a superficial understanding—while respondents recognise the existence of protected areas, they lack detailed knowledge about their number and legal status. Moreover, 22% admitted having no knowledge of this issue, highlighting the need for enhanced local environmental education, as shown in

Figure 14.

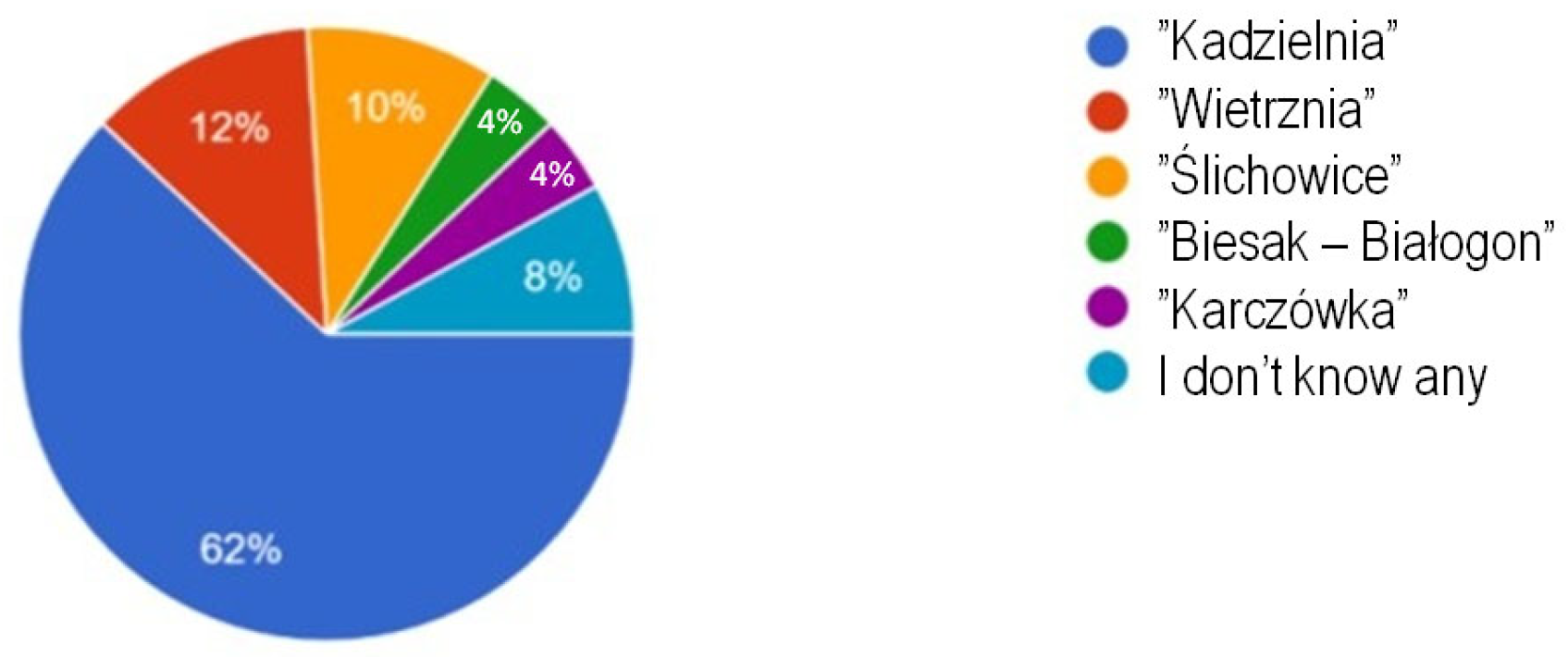

8.3.2. Most Recognised Nature Reserves

Among the listed nature reserves, Kadzielnia was identified by 62% of respondents as the best-known site, followed by Wietrznia (12%) and Ślichowice (10%). Only a few respondents mentioned Biesak–Białogon and Karczówka (4% each), while 8% could not identify any reserve, as shown in

Figure 15.

These results confirm that Kadzielnia functions as a natural and cultural landmark of Kielce, symbolising successful integration between nature and architecture within the urban fabric. The combination of recreational functions (amphitheatre, walking routes) with geological and ecological value (limestone formations, water body, protected flora, and fauna) contributes to its strong local identity.

8.3.3. Associations with Nature Reserves and Urban Landscape

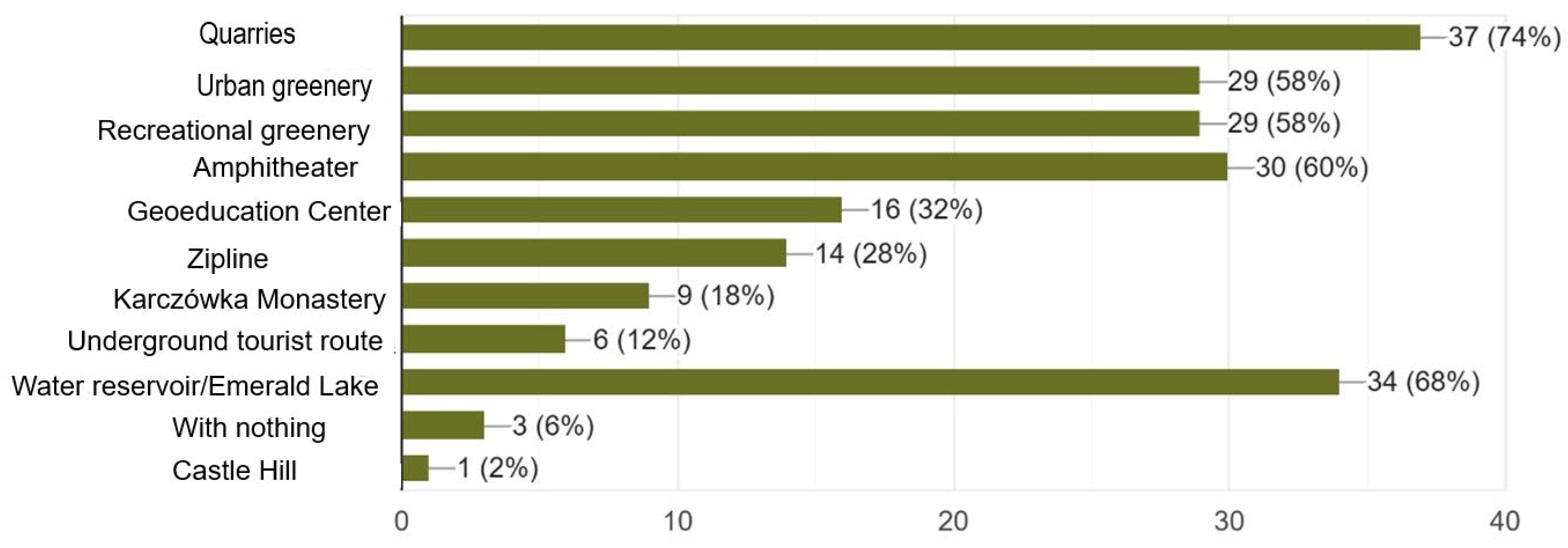

In a multiple-choice question on what respondents associate with Kielce nature reserves, the most frequent answers were quarries, emerald lake/water reservoir, amphitheatre, urban greenery, and recreational parks. These associations confirm a strong connection between the city’s natural and geological heritage and public perception, showing that reserves are seen not only as areas of protection but also as spaces for leisure and social interaction (

Figure 16).

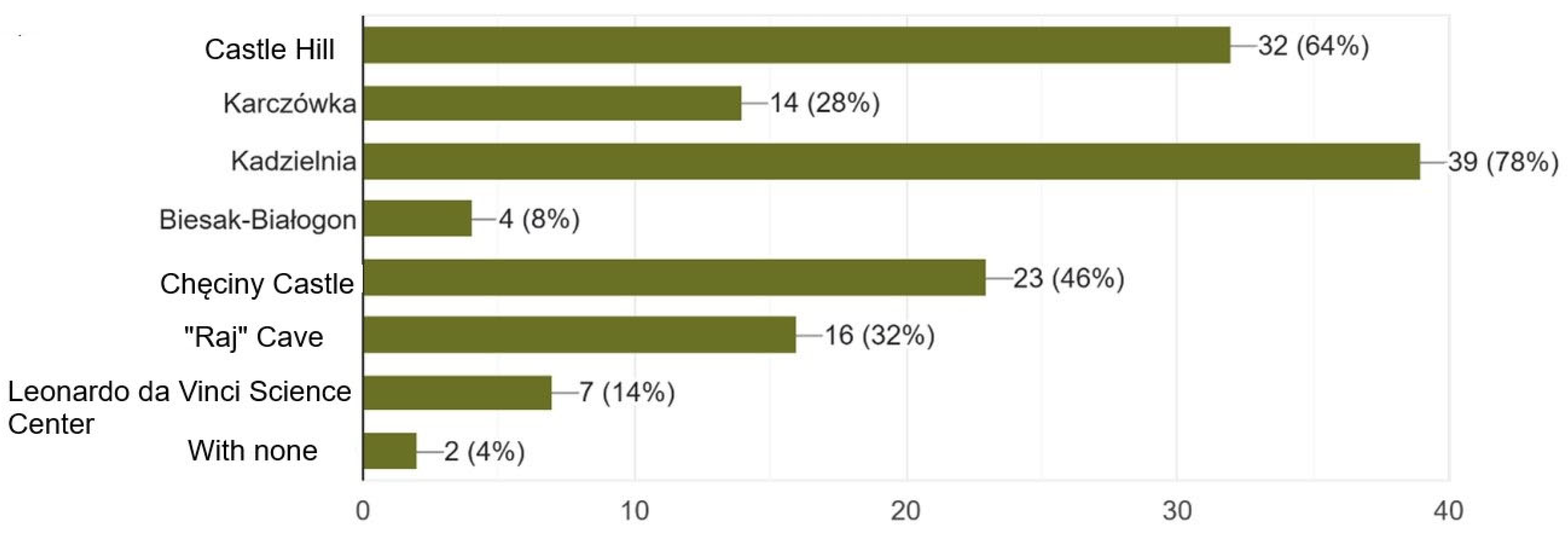

When asked about places most strongly associated with Kielce and its surroundings, respondents most often chose Kadzielnia, Castle Hill (Cathedral Basilica and former Bishops’ Palace), and Chęciny Castle. These responses suggest that both natural and cultural elements shape the city’s spatial identity—consistent with the concept of sustainable development as the harmonious coexistence of nature and culture (

Figure 17).

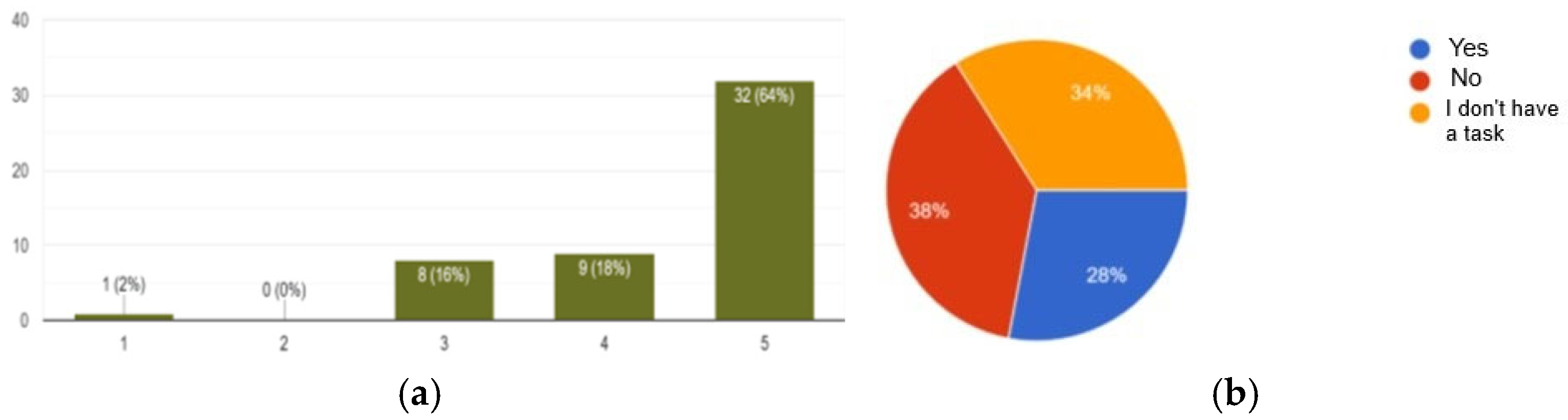

8.3.4. Attitudes Toward Nature Protection

Regarding the importance of protecting nature reserves, 64% of respondents rated it as “very important” and 18% as “important,” while only 2% considered it unimportant. These results demonstrate strong environmental values among residents of Kielce and the region (

Figure 18a).

When asked whether existing forms of nature protection are sufficient, responses were more varied: 28% found them adequate, 38% inadequate, and 34% had no opinion. This indicates scepticism toward the effectiveness of local environmental policy and the need for better public communication about ongoing ecological initiatives (

Figure 18b).

However, 94% of respondents agreed that nature protection measures are necessary, confirming a high level of public acceptance for environmental conservation and a foundation for implementing sustainable development strategies at the local level.

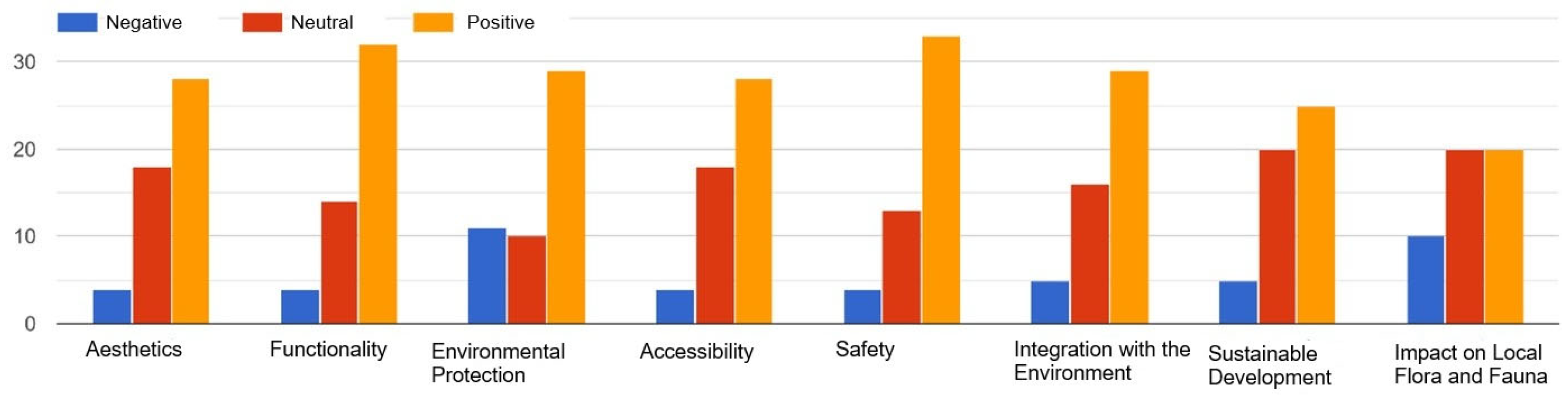

8.3.5. Impact of Architecture on Natural Areas

Respondents were also asked to assess the impact of architecture on nature reserves, classifying it as positive, neutral, or negative. Most perceived architecture as having a positive influence, suggesting that they see potential for coexistence between built and natural environments in urban spaces (

Figure 19).

8.3.6. Symbiosis of Nature and Architecture—Social Perception

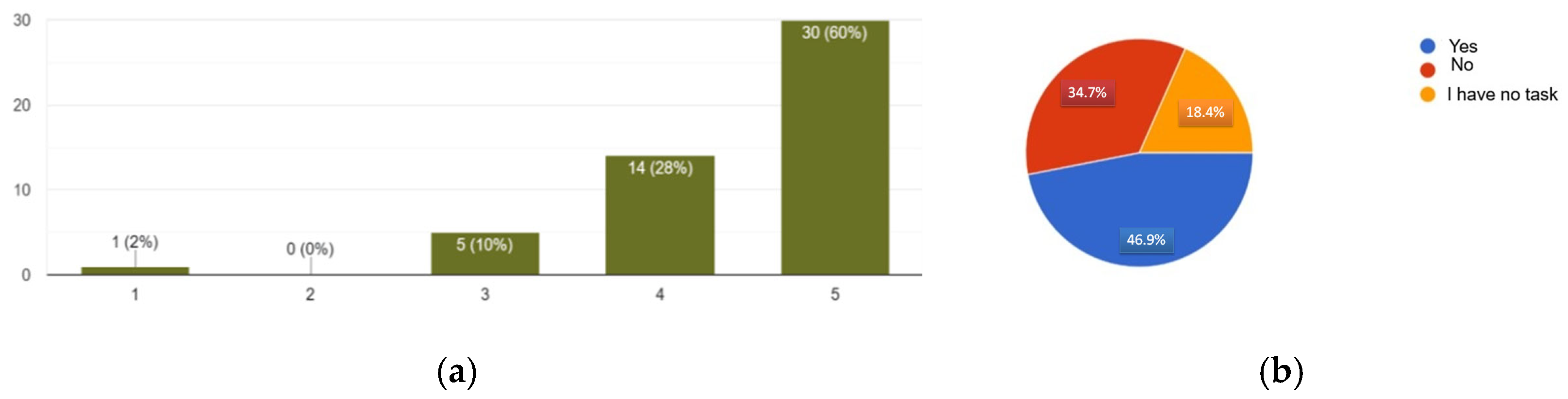

In the final section, respondents evaluated the importance of the symbiosis between nature and architecture. Over half (60%) considered it very important and 28% important, while only one person (2%) found it irrelevant (

Figure 20a). This reflects strong support for integrating natural components into architectural and urban design processes.

When assessing the actual situation in Kielce, 46.9% believed that harmony between nature and architecture exists in the city, 34.7% disagreed, and 18.4% were neutral (

Figure 20b). These findings suggest that residents recognise the potential for such symbiosis but perceive a gap between the ideal and its current implementation.

8.4. Significance of the Research for the Theory and Practice of Sustainable Development

The conducted social research holds significant theoretical and practical relevance for the science of sustainable development, particularly in the context of integrating the natural environment with urbanised space.

From a theoretical perspective, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of how urban residents perceive the relationship between nature and architecture in a local context. The findings indicate that ecological awareness is a multifaceted phenomenon shaped by cultural, educational, and spatial factors. The results confirm that the perception of sustainability extends beyond environmental dimensions to include aesthetic, cultural, and identity-related values, as reflected in the associations between nature reserves and architectural–landscape features (e.g., amphitheatre, quarry, urban greenery).

The research thus develops the theory of the symbiosis between nature and architecture within sustainable design, emphasising the role of social perception in planning processes. The results may serve as a basis for further studies on the role of local communities in shaping sustainable cities, as well as on the influence of environmental awareness on policy implementation.

The findings also highlight that sustainable development is relational and contextual—its interpretation depends on local heritage, geography, and social identity, supporting the concept of place-based sustainability. This aligns with global sustainability research (e.g., SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities), underscoring the importance of local context in achieving global goals.

From a practical perspective, the results provide valuable insights for local governments, urban planners, and architects. They reveal the need to strengthen environmental education and to integrate natural features into urban design. The data may support

the development of green infrastructure strategies combining ecological, social, and aesthetic functions;

the revitalization of post-industrial areas, such as quarries, by incorporating them into public and educational spaces;

the design of environmental education and community participation programmes;

the implementation of green architecture and nature-based design principles integrating natural and built environments.

The findings may also serve as a diagnostic tool for assessing public attitudes toward nature and as a reference point for further empirical research, both comparative and longitudinal. For medium-sized cities like Kielce—rich in geological and ecological assets—the results point to directions for development that combine heritage protection with contemporary urban growth.

In summary, this study contributes to the theory and practice of sustainable development by highlighting the importance of social awareness in implementing local environmental strategies, emphasising the role of community perception in creating sustainable urban environments, and illustrating the necessity of harmonising nature protection with architectural development in a participatory and balanced manner.

8.5. Research Limitations

This study is exploratory in nature, and its results cannot be fully generalised to the entire population of Kielce or the Świętokrzyskie region. The main limitations include the small sample size (n = 50) and the online sampling method, which may lead to an overrepresentation of younger and digitally active individuals.

Moreover, since the data are based on self-reported responses, they reflect declared attitudes rather than actual environmental behaviour.

Future studies should involve larger and more diverse samples and apply mixed research methods, such as in-depth interviews, field observations, or GIS spatial analysis. This would allow for a more robust verification of the hypotheses concerning public perception of the relationship between nature and architecture in the context of sustainable urban development.

8.6. The Relevance of Research Findings for Other Post-Industrial Cities—Practical and Scientific Implications

The results of the research conducted in Kielce, a city with a distinctly post-industrial character and rich in inanimate natural heritage, can serve as an important reference point for other urban centres in Poland and Europe that face similar challenges related to the transformation of degraded industrial areas into spaces conducive to sustainable development.

Kielce represents a city which—despite its medium size—possesses a unique geological landscape and several protected natural areas located within its administrative boundaries. The results of the social survey indicate that the local community perceives the potential for a symbiosis between nature and architecture and recognises the importance of nature protection, while at the same time considering existing actions as insufficient. These findings may be interpreted as a diagnosis of the state of environmental awareness and the quality of environmental management, which could be analogous for other post-industrial cities, particularly those located in regions with high levels of urbanisation and strong industrial heritage (e.g., Częstochowa, Wałbrzych, Tarnowskie Góry, Bytom, or Zabrze).

From a scientific perspective, the research conducted in Kielce and the Świętokrzyskie region demonstrates that the process of rebuilding the human–environment relationship in urban space is conditioned not only by spatial or environmental factors but also by cultural and social dimensions. The findings confirm that residents’ perception of the symbiosis between nature and architecture can serve as an important indicator of urban sustainability, complementing traditional environmental or economic metrics.

In practical terms, these results can be used by local governments, urban planners, and architects as a model for diagnosing local environmental awareness and as a starting point for designing revitalization strategies for post-industrial areas. The example of Kielce shows that the success of such transformation depends on the integration of the following aspects:

Environmental—Protection and rehabilitation of existing inanimate nature reserves.

Architectural—Integration of natural landscape elements with new urban structures.

Social—Community participation in urban design and the strengthening of local identity based on natural heritage.

Educational—Enhancement of ecological awareness and responsibility for the urban environment.

Such an approach increases the universality and applicability of the study results, offering a transferable framework for other post-industrial cities. The findings from Kielce confirm that even in medium-sized cities it is possible to achieve sustainable development goals by combining natural and cultural values within urban planning processes.

From a theoretical standpoint, this research contributes to the development of sustainability science by indicating that the symbiosis of nature and architecture can be regarded as an interdisciplinary research category that encompasses ecological, social, and aesthetic dimensions. This allows for an expansion of sustainable city analyses to include perceptual and cultural factors, which have so far been underrepresented in quantitative research.

In summary, the experience of Kielce can serve as a case study with strong comparative potential for other post-industrial centres, providing inspiration for developing local strategies of spatial and social transformation in the spirit of sustainable development. Incorporating similar studies into a network of comparative analyses would increase the universality of conclusions and enhance both the scientific and practical value of the concept of integrating nature and architecture in 21st-century cities.

9. Discussion

9.1. Introduction: Symbiosis of Nature and Architecture in the Context of Sustainable Development

The symbiosis between nature and architecture refers to designing buildings and spaces that enable a harmonious coexistence with the surrounding natural environment. Within the framework of sustainable development, this concept implies not only aesthetic integration with the landscape but also the mutual reinforcement of ecological, social, and cultural functions.

This study illustrates these relationships through the example of Kielce and the Świętokrzyskie region, a unique area of geological and natural heritage where post-industrial sites, such as former quarries, have been transformed into nature reserves and recreational–educational spaces.

The analysis confirms that architecture and nature in this region create a new quality of urban space in which humans become participants in natural processes rather than their antagonists. This approach reflects contemporary urban planning directions aligned with the principles of nature-based solutions (NBS) and urban resilience frameworks [

44].

9.2. Reclamation as a Tool for Building Socio-Environmental Resilience

The reclamation of post-mining areas in Kielce plays a key role in shaping socio-environmental resilience. This process not only restores ecological value but also supports the rebuilding of social bonds, local identity, and environmental awareness.

Transformed areas such as Kadzielnia, Wietrznia, and Ślichowice have become spaces for recreation, education, and community engagement, strengthening social integration and promoting a sustainable model of interaction with natural resources.

When compared with European examples—such as Golpa-Nord and Prosper-Haniel in Germany—the case of Kielce demonstrates that resilience does not have to rely solely on large-scale infrastructural investment. It may instead emerge from social learning, local participation, and cooperation between institutions that collectively shape the relationship between landscape and culture.

Thus, reclamation becomes a catalyst not only for environmental but also for social transformation, contributing to improved quality of life and the city’s long-term ecological stability [

45,

46].

9.3. Design Principles Supporting the Symbiotic Integration of Architecture and Nature

The harmonious integration of architecture and nature is achieved through specific design principles combining local identity, ecological sensitivity, and aesthetic coherence. In the analysed examples from Kielce and the Świętokrzyskie region, several strategies have been implemented to preserve the landscape identity of place:

Use of local materials (limestone, dolomite, locally sourced wood), which reduces the carbon footprint and reinforces visual coherence with the geological landscape.

Topographic adaptation—buildings are embedded in natural landforms, using existing rock formations and elevation differences (e.g., the Kadzielnia Amphitheatre).

Passive and ecological solutions—natural ventilation systems, green roofs, rainwater retention, permeable surfaces, and the use of renewable energy sources.

Ecological compositional strategies—minimising excessive interference with the natural environment by limiting building density and maintaining ecological corridors.

In comparison with the Eden Project in the United Kingdom, where architecture assumes an expressive and dominant form, the solutions in Kielce are characterised by subtle integration and a sense of “growing out” of the landscape. As a result, space acquires not only aesthetic but also educational and ecological dimensions, fostering a positive human–nature relationship [

47,

48].

9.4. Protection of Tangible and Intangible Heritage in the Context of Symbiosis

The symbiosis between architecture and nature encompasses not only ecological but also heritage-related dimensions—both tangible and intangible.

In Kielce, former quarries have become spaces that preserve traces of the past while introducing them into a new functional context. The preserved stone structures, geological exposures, and remnants of industrial activity constitute the tangible record of history, while new architectural forms reinterpret these elements through educational, cultural, and recreational functions.

At the same time, the intangible layer of heritage—the memory of local stonemasonry traditions, regional identity, and narratives associated with the mining history—is sustained. In this way, architecture acts as a mediator between the memory of place and contemporary use, supporting sustainable development grounded in cultural continuity.

Unlike projects such as Prosper-Haniel, where heritage is mainly presented in a musealised form, the Kielce model emphasises active reinterpretation of heritage—its incorporation into everyday urban life. This approach strengthens cultural resilience and the long-term preservation of local values [

49].

9.5. Long-Term Ecological Efficiency and the Need for a Systemic Approach

The long-term ecological efficiency of reclamation and the symbiosis between architecture and nature requires the development of effective evaluation tools. At present, Kielce lacks an integrated system for monitoring environmental outcomes such as biodiversity, water retention, emission reduction, and air quality improvement.

The introduction of measurable indicators would make it possible to assess not only environmental conditions but also the social benefits arising from the integration of architecture and nature.

Systemic actions are also necessary—combining spatial planning, cultural landscape protection, and environmental education. Interdisciplinary research connecting architecture, environmental science, sociology, and economics can support the creation of management models that ensure the ecological and social sustainability of reclaimed areas [

50].

9.6. Conclusion: The City in Harmony with Nature

The case of Kielce and the Świętokrzyskie region confirms that sustainable urban development is based on the coexistence of natural values, cultural heritage, and human creativity.

The reclamation of degraded areas—supported by an environmentally aware society and responsible spatial policy—creates the conditions for cities to develop in harmony with nature.

The symbiosis of architecture and nature, encompassing the protection of tangible and intangible heritage while supporting socio-environmental resilience and long-term ecological efficiency, represents one of the key directions for the future of sustainable urban development.

10. Final Conclusions

The symbiosis of nature and architecture is the design of buildings and spaces so that they coexist harmoniously in harmony with the surrounding natural environment. The publication shows the symbiosis of urban space and architecture with protected nature areas and the natural environment, using the city of Kielce and its surroundings as an example. Particular attention has been paid to post-mining areas, such as former quarries, which have also gained a new cultural or educational and didactic function thanks to their inclusion in the form of a nature conservation reserve and through reclamation and revitalisation. The existence of the city’s reserves and the architecture in them testifies to the fact that man can live in symbiosis with nature.

The authors show how the protection of nature and cultural heritage and the principles of the concept of sustainability can be effectively implemented in city planning and its architecture. This is exemplified by buildings such as the amphitheatre at Kadzielnia, the “Wietrznia” Geocentre, or the Leonardo da Vinci Science Centre in PodzamczeChęcińskie, which blend harmoniously into the natural landscape while creating a form that is an extension of it and using sustainable building materials and ecological solutions. The article shows examples of implementation from Poland and other European countries and the results of the survey, which showed that the inhabitants of Kielce and the Świętokrzyskie region are aware of and appreciate the protection of cultural and natural heritage and are aware of the existence of nature reserves in the city area. The survey showed that protection in the form of nature reserves is very important to the respondents; however, in their opinion, such protection in the city of Kielce remains insufficient. The results from the survey demonstrate the growing awareness and support for initiatives that combine urban development with nature care and how important the symbiosis of nature and architecture is.