How Consumers’ Motivations Influence Preferences for Organic Agricultural Products in Türkiye?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Organic Agriculture

1.2. Motivations for Organic Agricultural Products

1.2.1. Health Motivation

1.2.2. Economic Motivation

1.2.3. Environmental Motivation

1.2.4. Social Motivation

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Methodology of the Research

- Outer VIF (Outer model VIF) values should be <10.

- p values of factor weights should be <0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lamonaca, E.; Cafarelli, B.; Calculli, C.; Tricase, C. Consumer Perception of Attributes of Organic Food in Italy: A CUB Model Study. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, I.A.V.; Toral, J.N.; Vázquez, Á.T.P.; Hernández, F.G.; Ferrer, G.J.; Cano, D.G. Potential for Organic Conversion and Energy Efficiency of Conventional Livestock Production in a Humid Tropical Region of Mexico. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutter, O. Report Submitted by the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- IFOAM. International Federation of Organic Agricultural Movements. 2025. Available online: https://www.ifoam.bio/why-organic/organic-landmarks/definition-organic (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Boz, İ.; Kılıç, O. Measures to be Taken for the Development of Organic Agriculture in Türkiye. Turk. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 8, 390–400. [Google Scholar]

- Sadiq, M.; Adil, M.; Paul, J. Does Social Influence Turn Pessimistic Consumers Green? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2937–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M.; Gupta, B. Determinants of Organic Food Consumption. A systematic Literature Review on Motives and Barriers. Appetite 2019, 143, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.; Gangahagedara, R.; Gamage, J.; Jayasinghe, N.; Kodikara, N.; Suraweera, P.; Merah, O. Role of Organic Farming for Achieving Sustainability in Agriculture. Farming Syst. 2023, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterstein, J.; Zhu, B.; Habisch, A. How Personal and Social-Focused Values Shape the Purchase Intention for Organic Food: Cross-Country Comparison Between Thailand and Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Jørgensen, A.K.; Sandager, S. Consumer Decision Making Regarding a “Green” Everyday Product. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, M.H. Food Choice Motives for Consumers in Lebanon: A Descriptive Study. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2607–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiryürek, K. The Concept of Organic Agriculture and Current Status of in the World and Turkey. J. Agric. Fac. Gaziosmanpaşa Univ. 2011, 28, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pezikoğlu, F. Determination of the Policies Related to Application Systems of the Sustainable Agricultural Practices in Turkey. Ph.D. Thesis, Bursa Uludag University, Nilüfer, Türkiye, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Akkaya, F. Türkiye’de Ekolojik (Organik) Ürün Üretimi ve Pazarlaması. Türkiye II. In Proceedings of the Ekolojik Tarım Sempozyumu-Bildiriler, Antalya, Türkiye, 14–16 November 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Araştırma ve Piyasa Geliştirme Müdürlüğü. Dünya ve Türkiye’de Organik Tarımın Durumu. ITB İzmir Ticaret Borsası 2025. Available online: https://itb.org.tr/dosya/rapordosya/dunya-ve-turkiyede-organik-tarim.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Aral, O.; Cufadar, Y. Investigation of Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviours of University Students/Consumers About Organic Animal Products. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 2242–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, D. Consumer Perceptions of Natural and Organic Cosmetics: A Qualitative Study in The Context of Gender and Media Influence. J. Mark. Mark. Res. 2025, 18, 637–674. [Google Scholar]

- Feil, A.A.; Cyrne, C.C.S.; Sindelar, F.C.W.; Barden, J.E.; Dalmoro, M. Profiles of Sustainable Food Consumption: Consumer Behavior Toward Organic Food in Southern Region of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, M.J.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Consumers’ Attention, Experience, and Action to Organic Consumption: The Moderating Role of Anticipated Pride and Moral Obligation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-L.; Chiu, S.F.; Tan, R.R.; Siriban-Manalang, A.B. Sustainable Consumption and Production for Asia: Sustainability Through Green Design and Practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubicic, M.; Saric, M.M.; Klarin, I.; Rumbak, I.; Baric, I.C.; Ranilovic, J.; El-Kenawy, A.; Papageorgiou, M.; Vittadini, E.; Bizjak, M.C.; et al. Motivation for Health Behaviour: A Predictor of Adherence to Balanced and Healthy Food Across Different Coastal Mediterranean Countries. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 91, 105018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürkenbeck, K. Consumer Trust in Organic Food Producers and Its Influence on Consumers’ Attitudes Toward Food Reformulation and Its Sensory Consequences. Food Humanit. 2023, 1, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Health Motive and the Purchase of Organic Food: A Metaanalytic Review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.Z.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Usman, S.; Ali, N.B.; Asi, M.R. Variation of Deoxynivalenol Levels in Corn and Its Products Available in Retail Markets of Punjab, Pakistan and Estimation of Risk Assessment. Toxins 2021, 13, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japutra, A.; Vidal-Branco, M.; Higueras-Castillo, E.; Molinillo, S. Unraveling the Mechanism to Develop Health Consciousness from Organic Food: A Cross-Comparison of Brazilian and Spanish Millennials. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueasangkomsate, P.; Santiteerakul, S. A Study of Consumers’ Attitudes and Intention to Buy Organic Foods for Sustainability. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 34, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Caso, D.; Del Giudice, T.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Cicia, G. Explaining Consumer Purchase Behavior for Organic Milk: Including Trust and Green Selfidentity within the Theory of Planned Behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 76, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Kushwah, S.; Salo, J. Why Do People Buy Organic Food? The Moderating Role of Environmental Concerns and Trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.S.; Ilter, B. Motives Underlying Organic Food Consumption in Turkey: Impact of Health, Environment, and Consumer Values on Purchase Intentions. Econ. World 2017, 5, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, S.; Deveci, F.G.; Yildiz, T. Do We Know Organic Food Consumers? The Personal and Social Determinants of Organic Food Consumption. Istanb. Bus. Res. (IBR) 2019, 48, 2630–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengi, Ç.Ö.; Akçakaya, S.D.; Ekici, E.M. Relationship Between Sustainable Food Literacy, Organic Food Consumption and Climate Change Awareness and Worry in Türkiye. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, C.; Best, T. Low-Carbohydrate, High-Fat Dieters: Characteristic Food Choice Motivations, Health Perceptions and Behaviours. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 62, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, J.; Huang, W.; Tang, Y.; Li, R.Y.M.; Yue, X. Health-Driven Mechanism of Organic Food Consumption: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Li, M.; Hao, Y. Purchasing Behavior of Organic Food Among Chinese University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grankvist, G.; Biel, A. The Importance of Beliefs and Purchase Criteria in the Choice of Eco-Labeled Food Products. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azlie, W.E.; Zahari, M.S.; Majid, H.N.A.; Hanafiah, M.H. To What Extent Does Consumers’ Perceived Health Consciousness Regarding Organic Food Influence Their Dining Choices at Organic Restaurants? An Empirical Investigation. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 34, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, F.; Tohidi, A. Analysis of Green Word-of-Mouth Advertising Behavior of Organic Food Consumers. Appetite 2024, 198, 107324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Maroscheck, N.; Hamm, U. Are Organic Consumers Preferring or Avoiding Foods with Nutrition and Health Claims? Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 30, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Screti, C.; Edwards, K.; Blissett, J. Understanding Family Food Purchasing Behaviour of Low-Income Urban UK Families: An Analysis of Parent Capability, Opportunity and Motivation. Appetite 2024, 195, 107183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polimeni, J.M.; Iorgulescu, R.I.; Mihnea, A. Understanding Consumer Motivations for Buying Sustainable Agricultural Products at Romanian Farmers Markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melovic, B.; Cirovic, D.; Backovic-Vulic, T.; Dudic, B.; Gubiniova, K. Attracting Green Consumers as a Basis for Creating Sustainable Marketing Strategy on the Organic Market-Relevance for Sustainable Agriculture Business Development. Foods 2020, 9, 1552. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, M.T.; Mackay, C.M.L.; Droogendyk, L.M.; Payne, D. What Predicts Environmental Activism? The Roles of Identification with Nature and Politicized Environmental Identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 61, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, M.C.; Fiorillo, D. Other-Regarding Preferences in Pro-Environmental Behaviours: Empirical Analysis and Policy Implications of Organic and Local Food Products Purchasing in Italy. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 343, 118174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.H.; Nguyen, P.M. Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Norm Activation Model to Investigate Organic Food Purchase Intention: Evidence from Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditlevsen, K.; Denver, S.; Christensen, T.; Lassen, J.A. Taste for Locally Produced Food-Values, Opinions and Sociodemographic Differences Among ‘Organic’ and ‘Conventional’ Consumers. Appetite 2020, 147, 104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S. Mapping the Values Driving Organic Food Choice Germany vs the UK. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 995–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviani, D. Food, Mass Media and Lifestyles. A Hyperreal Correlation. Ital. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 3, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kihlberg, I.; Risvik, E. Consumers of Organic Foods-Value Segments and Liking of Bread. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 471–481. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J. Organic Food as Self-Presentation: The Role of Psychological Motivation in Older Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Organic Food. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puska, P. Does Organic Food Consumption Signal Prosociality? An Application of Schwartz’s Value Theory. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2019, 25, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, H.; Şenel, M. Investigating Consumer Motivations in the Purchase of Organic Foods Using Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique. Karabük Univ. J. Inst. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bozpolat, C. Motivations Guiding Organic Food Purchase Intention: An Examination Within The Framework of Self-Determination Theory. Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli Univ. J. ISS 2025, 15, 1251–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Wilkins, S. Purposive Sampling in Qualitative Research: A Framework for the Entire Journey. Qual. Quant. 2025, 59, 1461–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, J.; Reinders, M.J. Social Identification, Social Representations, and Consumer Innovativeness in an Organic Food Context: A Cross-National Comparison. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, H.; Oerlemans, L.; Van Stroe-Biezen, S. Socialinfluence on Sustainable Consumption: Evidence from a Behavioural Experiment. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muposhi, A.; Dhurup, M. A Qualitative Inquiry of Generation Y Consumers’ Selection Attributes in the case of Organic Products. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2016, 15, 9571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Zepeda, L.; Sirieix, L. Exploring the Social Value of Organic Food: A Qualitative Study in France. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, E.J.; Hur, W.M. The Mediating Role of Norms in the Relationship Between Green Identity and Purchase Intention of Eco-Friendly Products. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2012, 19, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.M.; Lauro, C. PLS Path Modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avkıran, N.K. Rise of the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: An Application in Banking. Int. Ser. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2018, 267, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using smartPLS 3.0. In An Updated Guide and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Malissiova, E.; Tsokana, K.; Soultani, G.; Alexandraki, M.; Katsioulis, A.; Manouras, A. Organic Food: A Study of Consumer Perception and Preferences in Greece. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.S.C.; Faria, C.P.; Jose, J.F.B.S. Organic Food Consumers and Producers: Understanding their Profiles, Perceptions, and Practices. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandallıoğlu, A. Consumption of Organic Agricultural Products and Consumer Tendencies in Adana. Ph.D. Thesis, Çukurova University Institute of Natural and Applied Sciences Department of Agricultural Economics, Adana, Türkiye, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- İnci, H.; Karakaya, E.; Şengül, A.Y. Factors Affecting Organic Product Consumption (Diyarbakır Case). J. Agric. Nat. 2017, 20, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Kadirhanoğulları, İ.H.; Karadaş, K.; Özger, Ö.; Konu, M. Determination of Organic Product Consumer Preferences with Decision Tree Algorithms: Sample of Igdir Province. Yuz. Yıl Univ. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 31, 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Ngobo, P.V. What Drives Household Choice of Organic Products in Grocery Stores? J. Retail. 2011, 87, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, H.; Wright, D. Marketing Tothenewwellnessconsumer: Understandingtrends in Wellness(1e); The Hartman Group: Bellevue, WA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Iranian Students’ Intention to Purchase Organic Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraboina, R.; Cooper, O.; Amini, M. Segmentation of Organic Food Consumers: A Revelation of Purchase Factors in Organic Food Markets. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.H.; Lee, C.H.; Huang, C.T. Why Buy Organic Rice? Genetic Algorithm Based Fuzzy Association Mining Rules for Means-End Chain Data. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 692–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortheix, F.M.; Schwartz, S.H. Values that Underlie and Undermine Well-Being: Variability Across Countries. Eur. J. Personal. 2017, 31, 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, K.; Tapas, P.; Paliwal, M. Evaluating the Efect of Values Infuencing the Choice of Organic Foods. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecevit, M.Z.; Baş, T.; Öztek, M.Y. Do Organic Products Have Social Value? A Qualitative Research on Turkey. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2022, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, T. Australians’ Organic Food Beliefs, Demographics and Values. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Matharu, M.; Gupta, M. Examining Consumer Purchase Intention Towards Organic Food: An Empirical Study. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2023, 9, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, S. Role of Consumer Health Consciousness, Food Safety & Attitude on Organic Food Purchase in Emerging Market: A Serial Mediation Model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafees, L.; Hyatt, E.M.; Garber, L.L.; Das, N.; Boya, Ü.O. Motivations to Buy Organic Food in Emerging Markets: An Exploratory Study of Urban Indian Millennials. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, Ş.G.; Kırcova, İ. Consumers’ Approach towards Organic Foods and Marketing Communication Suggestions. Turk. Rev. Commun. Stud. 2020, 35, 338–367. [Google Scholar]

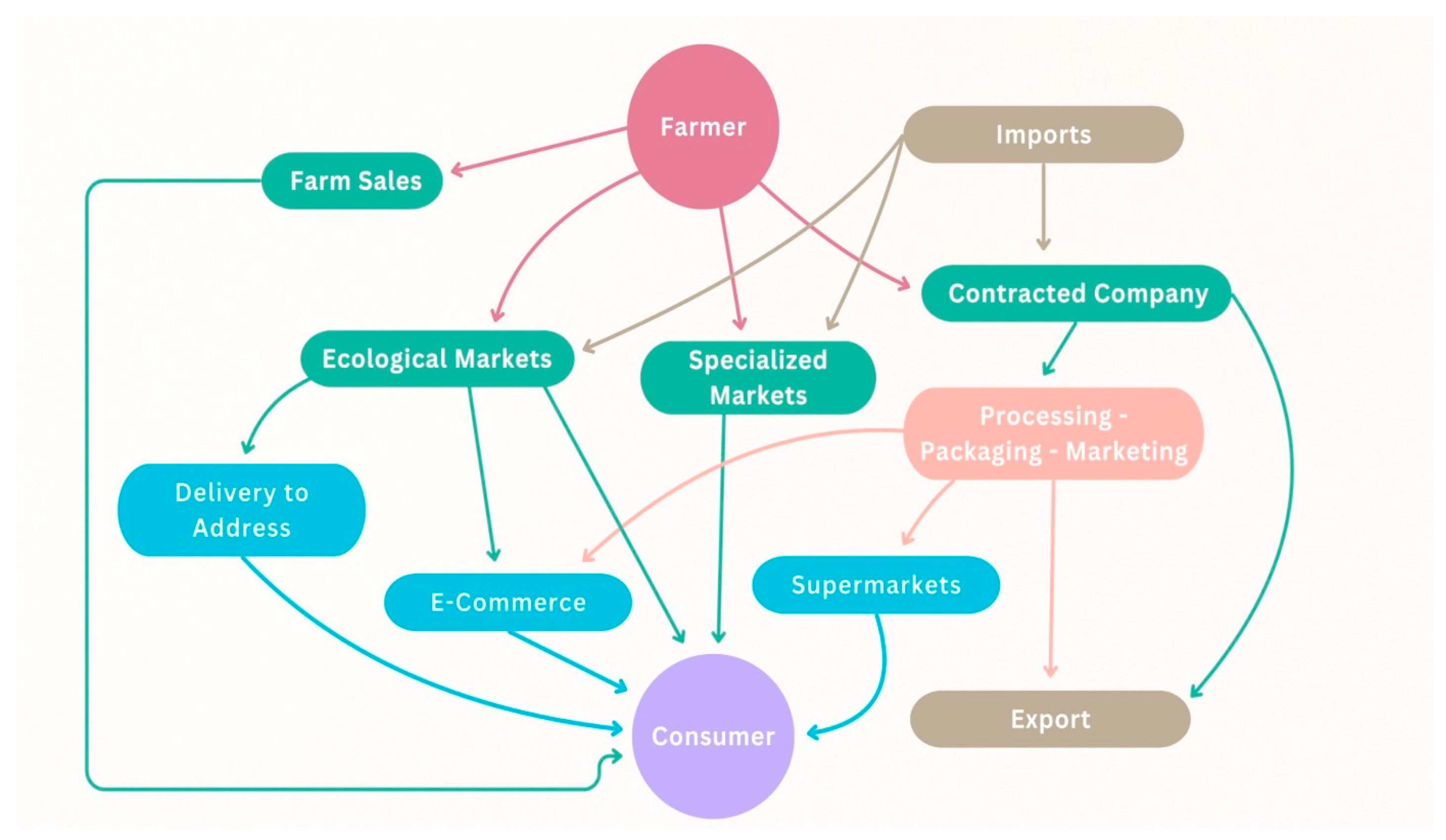

- T.C. Tarım ve Orman Bakanlığı. 2025. Available online: https://arastirma.tarimorman.gov.tr/yalovabahce/Belgeler/brosurler/OrganikTarimsalUrunlerinPazarlanmasi.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- İnan, R.; Bekar, A.; Urlu, H. An Assessment of Consumers of Organic Food Purchase Behavior and Attitudes. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2021, 9, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kürkçü, B. Understanding Health Concerns and Social Value Perceptions in Consumers Intentions to Consume Functional Food: The Moderating Role of Health Knowledge. Master’s Thesis, Nevşehir Hacı Bektaş Veli University, Nevşehir, Türkiye, 2022. Available online: https://acikerisim.nevsehir.edu.tr/bitstream/handle/20.500.11787/7981/BERNA%20K%C3%9CRK%C3%87%C3%9C.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Uzundumlu, A.S.; Sezgin, A. Analysis of Factors Effecting Organic Product Consumption. A Case Study of Erzurum Province. IBAD J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 441–451. [Google Scholar]

| Motivation | Statements of the Variables |

|---|---|

| Health motivation (HM) | Organic agricultural products do not contain additives. |

| Organic agricultural products do not contain genetically modified substances. | |

| Organic agricultural products are richer in nutritional value. | |

| Organic agricultural products guarantee food safety. | |

| Economic motivation (ECOM) | Buying organic agricultural products supports the local economy. |

| Buying organic agricultural products supports small farmers. | |

| The price paid for organic agricultural products is used to buy higher quality products. | |

| Environmental motivation (EM) | Organic farming protects the soil because it does not use chemical pesticides and fertilizers. |

| Organic farming protects water resources because it does not use chemical pesticides and fertilizers. | |

| Organic farming is necessary for the sustainability of agriculture in the future. | |

| Organic farming protects animal health and welfare. | |

| Social motivation (SOCM) | Consuming organic agricultural products provides a person with social status. |

| Consuming organic agricultural products is preferred by conscious consumers. | |

| Buying organic agricultural products makes a person feel special. Allows chatting with others interested in organic agricultural products. |

| Hypothesis | Theory | Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | HM positively affects attitudes and purchasing behavior towards organic products. | TPB [23] | HM → positive attitude → purchase |

| H2 | EM positively affects attitudes and purchasing behavior towards organic products. | VBN [24] | EM → personal norm → pro-environmental behavior |

| H3 | SOCM positively affects attitudes and purchasing behavior towards organic products. | VBN [24] | SOCM → social norm → purchase behavior |

| H4 | ECOM positively affects attitudes and purchasing behavior towards organic products. | TPB [23] | ECOM → perception of economic benefit → positive attitude → purchase |

| H5 | Demographic variables positively affect attitudes and purchasing behavior towards organic products. | TPB & VBN [23,24] | Demographic characteristic → value/attitude → behavior |

| H6 | Attitude towards organic products positively affects purchasing behavior. | TPB [23] | Attitude → purchase behavior |

| Independent Variables | VIF | Independent Variables | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| EM1 | 1.984 | Age (26–35) | 1.000 |

| EM2 | 2.199 | Age (36–45) | 1.000 |

| EM3 | 2.236 | Age (46–55) | 1.000 |

| EM4 | 2.248 | Age (56–65) | 1.000 |

| ECOM1 | 1.811 | Age (66 and above) | 1.000 |

| ECOM2 | 1.843 | MSTA (Married) | 1.000 |

| ECOM3 | 1.106 | EDU (Primary School) | 1.000 |

| PBEH | 1.000 | EDU (Secondary School) | 1.000 |

| HM1 | 2.596 | EDU (High School) | 1.000 |

| HM2 | 2.668 | EDU (Vocational School) | 1.000 |

| HM3 | 1.863 | EDU (Faculty) | 1.000 |

| HM4 | 2.226 | EDU (Master’s/PhD) | 1.000 |

| SOCM1 | 1.404 | HSIZE (2) | 1.000 |

| SOCM2 | 1.074 | HSIZE (3) | 1.000 |

| SOCM3 | 1.383 | HSIZE (4) | 1.000 |

| SOCM4 | 1.149 | HSIZE (5 and above) | 1.000 |

| CAT1 | 1.312 | CHILD (1) | 1.000 |

| CAT2 | 1.252 | CHILD (2) | 1.000 |

| CAT3 | 1.906 | CHILD (3 and above) | 1.000 |

| CAT4 | 2.342 | Gender (Female) | 1.000 |

| CAT5 | 1.715 |

| Factor Weight | p | Factor Loading | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM1 → Environmental Motivation | 0.142 | 0.088 | 0.673 | <0.001 |

| EM2 → Environmental Motivation | 0.095 | 0.335 | 0.709 | <0.001 |

| EM3 → Environmental Motivation | 0.519 | <0.001 | 0.928 | <0.001 |

| EM4 → Environmental Motivation | 0.397 | <0.001 | 0.895 | <0.001 |

| ECOM1 → Economic Motivation | 0.567 | <0.001 | 0.915 | <0.001 |

| ECOM2 → Economic Motivation | 0.449 | <0.001 | 0.880 | <0.001 |

| ECOM3 → Economic Motivation | 0.184 | 0.002 | 0.468 | <0.001 |

| PBEH ← Purchasing Behavior | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HM1 → Health Motivation | 0.034 | 0.766 | 0.696 | <0.001 |

| HM2 → Health Motivation | 0.144 | 0.158 | 0.743 | <0.001 |

| HM3 → Health Motivation | 0.572 | <0.001 | 0.924 | <0.001 |

| HM4 → Health Motivation | 0.391 | <0.001 | 0.872 | <0.001 |

| SOCM1 → Social Motivation | 0.501 | <0.001 | 0.766 | <0.001 |

| SOCM2 → Social Motivation | −0.119 | 0.054 | 0.126 | 0.069 |

| SOCM3 → Social Motivation | 0.248 | <0.001 | 0.661 | <0.001 |

| SOCM4 → Social Motivation | 0.586 | <0.001 | 0.798 | <0.001 |

| CAT1 → Consumer Attitude | 0.144 | 0.002 | 0.580 | <0.001 |

| CAT2 → Consumer Attitude | 0.423 | <0.001 | 0.749 | <0.001 |

| CAT3 → Consumer Attitude | 0.076 | 0.176 | 0.678 | <0.001 |

| CAT4 → Consumer Attitude | 0.338 | <0.001 | 0.834 | <0.001 |

| CAT5 → Consumer Attitude | 0.338 | <0.001 | 0.787 | <0.001 |

| Factor Weight | p | Factor Loading | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM1 → Environmental Motivation | 0.142 | 0.085 | 0.672 | <0.001 |

| EM2 → Environmental Motivation | 0.094 | 0.326 | 0.708 | <0.001 |

| EM3 → Environmental Motivation | 0.519 | <0.001 | 0.928 | <0.001 |

| EM4 → Environmental Motivation | 0.398 | <0.001 | 0.895 | <0.001 |

| ECOM1 → Economic Motivation | 0.566 | <0.001 | 0.914 | <0.001 |

| ECOM2 → Economic Motivation | 0.450 | <0.001 | 0.881 | <0.001 |

| ECOM3 → Economic Motivation | 0.184 | 0.002 | 0.467 | <0.001 |

| PBEH ← Purchasing Behavior | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| HM1 → Health Motivation | 0.034 | 0.769 | 0.696 | <0.001 |

| HM2 → Health Motivation | 0.144 | 0.168 | 0.743 | <0.001 |

| HM3 → Health Motivation | 0.572 | <0.001 | 0.924 | <0.001 |

| HM4 → Health Motivation | 0.391 | <0.001 | 0.872 | <0.001 |

| SOCM1 → Social Motivation | 0.480 | <0.001 | 0.771 | <0.001 |

| SOCM3 → Social Motivation | 0.243 | <0.001 | 0.665 | <0.001 |

| SOCM4 → Social Motivation | 0.584 | <0.001 | 0.803 | <0.001 |

| CAT1 → Consumer Attitude | 0.141 | 0.003 | 0.577 | <0.001 |

| CAT2 → Consumer Attitude | 0.421 | <0.001 | 0.747 | <0.001 |

| CAT3 → Consumer Attitude | 0.080 | 0.158 | 0.680 | <0.001 |

| CAT4 → Consumer Attitude | 0.336 | <0.001 | 0.835 | <0.001 |

| CAT5 → Consumer Attitude | 0.341 | <0.001 | 0.789 | <0.001 |

| Coefficient (β) | Std. Deviation | t | p | R2 | Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSIZE (2) → PBEH | 0.017 | 0.057 | 0.291 | 0.771 | 0.207 | 0.181 |

| HSIZE (3) → PBEH | 0.086 | 0.067 | 1.290 | 0.197 | ||

| HSIZE (4) → PBEH | 0.115 | 0.069 | 1.680 | 0.093 | ||

| HSIZE (5 and above) → PBEH | 0.118 | 0.062 | 1.902 | 0.057 | ||

| CHILD (1) → PBEH | 0.011 | 0.032 | 0.333 | 0.739 | ||

| CHILD (2) → PBEH | 0.038 | 0.027 | 1.404 | 0.160 | ||

| CHILD (3 and above) → PBEH | 0.014 | 0.033 | 0.424 | 0.671 | ||

| GENDER (Female) → PBEH | 0.078 | 0.033 | 2.393 | 0.017 | ||

| ECOM → PBEH | 0.054 | 0.039 | 1.406 | 0.160 | ||

| EDU (Primary School) → PBEH | 0.045 | 0.310 | 0.147 | 0.883 | ||

| EDU (Secondary School) → PBEH | 0.144 | 0.335 | 0.430 | 0.667 | ||

| EDU (High School) → PBEH | 0.148 | 0.531 | 0.278 | 0.781 | ||

| EDU (Vocational School) → PBEH | 0.123 | 0.535 | 0.230 | 0.818 | ||

| EDU (Faculty) → PBEH | 0.124 | 0.610 | 0.204 | 0.839 | ||

| EDU (Master’s/PhD) → PBEH | 0.073 | 0.369 | 0.199 | 0.842 | ||

| MSTA (Married) → PBEH | 0.014 | 0.042 | 0.345 | 0.730 | ||

| HM → PBEH | 0.016 | 0.041 | 0.382 | 0.703 | ||

| SOCM → PBEH | 0.180 | 0.035 | 5.134 | <0.001 | ||

| CAT → PBEH | 0.254 | 0.043 | 5.896 | <0.001 | ||

| AGE (26–35) → PBEH | 0.027 | 0.048 | 0.572 | 0.567 | ||

| AGE (36–45) → PBEH | −0.008 | 0.052 | 0.151 | 0.880 | ||

| AGE (46–55) → PBEH | −0.029 | 0.046 | 0.638 | 0.524 | ||

| AGE (56–65) → PBEH | 0.030 | 0.044 | 0.679 | 0.497 | ||

| AGE (66 and above) → PBEH | −0.002 | 0.033 | 0.052 | 0.958 | ||

| EM → PBEH | −0.030 | 0.042 | 0.695 | 0.487 | ||

| HSIZE (2) → CAT | 0.028 | 0.049 | 0.580 | 0.562 | 0.518 | 0.503 |

| HSIZE (3) → CAT | 0.004 | 0.055 | 0.071 | 0.943 | ||

| HSIZE (4) → CAT | −0.004 | 0.057 | 0.070 | 0.944 | ||

| HSIZE (5 and above) → CAT | −0.010 | 0.050 | 0.190 | 0.849 | ||

| CHILD (1) → CAT | −0.018 | 0.029 | 0.638 | 0.523 | ||

| CHILD (2) → CAT | −0.003 | 0.022 | 0.143 | 0.886 | ||

| CHILD (3 and above) → CAT | −0.032 | 0.030 | 1.058 | 0.290 | ||

| GENDER (Female) → → CAT | 0.027 | 0.025 | 1.088 | 0.277 | ||

| ECOM → CAT | 0.202 | 0.041 | 4.951 | <0.001 | ||

| EDU (Primary School) → CAT | 0.207 | 0.199 | 1.038 | 0.299 | ||

| EDU (Secondary School) → CAT | 0.249 | 0.212 | 1.173 | 0.241 | ||

| EDU (High School) → CAT | 0.474 | 0.337 | 1.405 | 0.160 | ||

| EDU (Vocational School) → CAT | 0.538 | 0.342 | 1.574 | 0.116 | ||

| EDU (Faculty) → CAT | 0.677 | 0.385 | 1.760 | 0.079 | ||

| EDU (Master’s/PhD) → CAT | 0.434 | 0.236 | 1.843 | 0.066 | ||

| MSTA (Married) → CAT | 0.026 | 0.033 | 0.808 | 0.419 | ||

| HM → CAT | 0.258 | 0.043 | 5.929 | <0.001 | ||

| SOCM → CAT | 0.221 | 0.033 | 6.685 | <0.001 | ||

| AGE (26–35) → CAT | 0.057 | 0.036 | 1.604 | 0.109 | ||

| AGE (36–45) → CAT | 0.119 | 0.040 | 2.992 | 0.003 | ||

| AGE (46–55) → CAT | 0.092 | 0.036 | 2.537 | 0.011 | ||

| AGE (56–65) → CAT | 0.093 | 0.030 | 3.045 | 0.002 | ||

| AGE (66 and above) → CAT | 0.010 | 0.032 | 0.296 | 0.767 | ||

| EM → CAT | 0.137 | 0.047 | 2.914 | 0.004 |

| Model | Index | Value | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated | SRMR | 0.020 | Excellent |

| d_ULS | 0.399 | Acceptable | |

| d_G | 0.551 | Acceptable | |

| Estimated | SRMR | 0.020 | Excellent |

| d_ULS | 0.416 | Acceptable | |

| d_G | 0.602 | Acceptable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aydın Eryılmaz, G. How Consumers’ Motivations Influence Preferences for Organic Agricultural Products in Türkiye? Sustainability 2025, 17, 10539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310539

Aydın Eryılmaz G. How Consumers’ Motivations Influence Preferences for Organic Agricultural Products in Türkiye? Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310539

Chicago/Turabian StyleAydın Eryılmaz, Gamze. 2025. "How Consumers’ Motivations Influence Preferences for Organic Agricultural Products in Türkiye?" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310539

APA StyleAydın Eryılmaz, G. (2025). How Consumers’ Motivations Influence Preferences for Organic Agricultural Products in Türkiye? Sustainability, 17(23), 10539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310539

_Li.png)