Towards Sustainable Digital Entrepreneurship: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and the Moderating Influence of Social Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Determinants of Digital Entrepreneurship Intentions

2.2. The Roles of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Social Support in Digital Entrepreneurship

2.3. Digital Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia

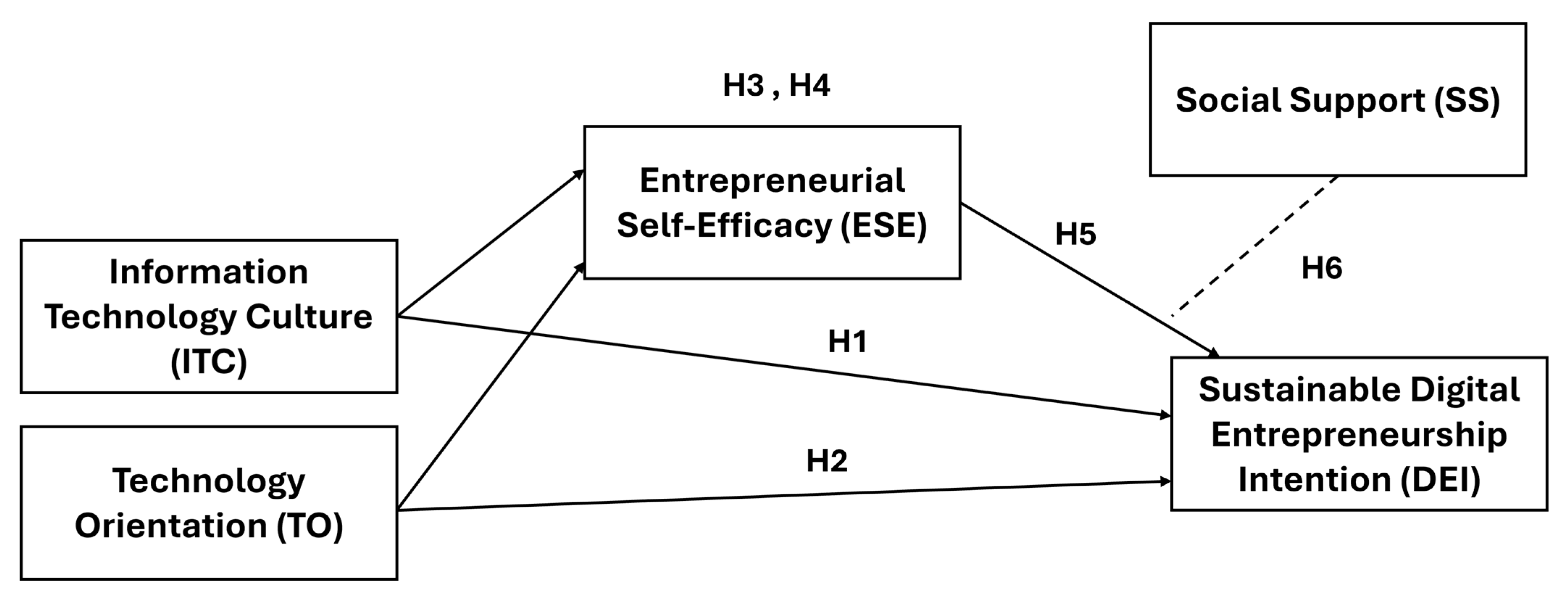

3. Conceptual Framework

4. Methodology

5. Results

5.1. Demographic Profiles of the Survey Participants

5.2. Construct Validity and Reliability

5.2.1. Convergent Validity and Reliability

5.2.2. Discriminant Validity

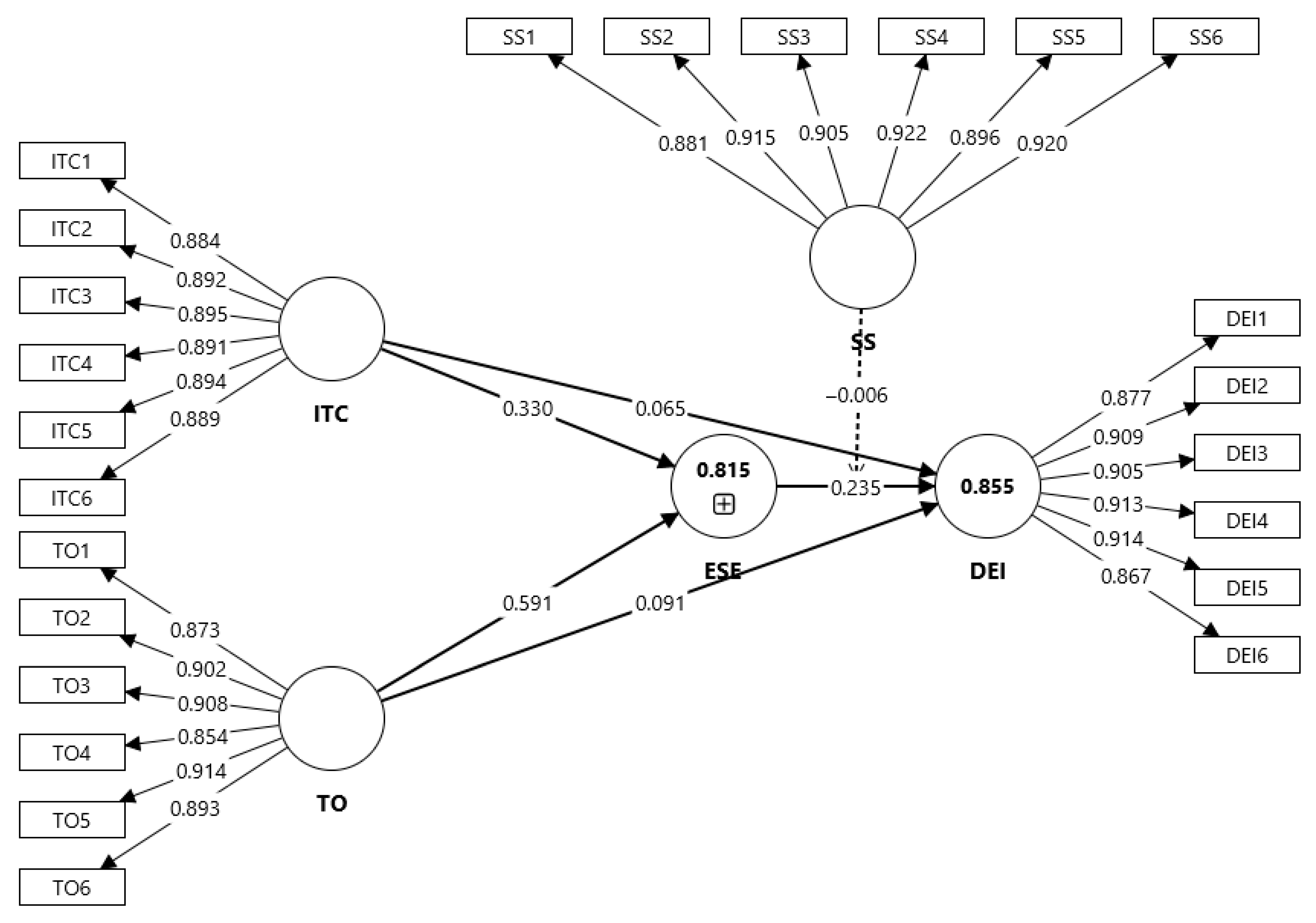

5.3. Measurement Model

5.3.1. The R-Square Values

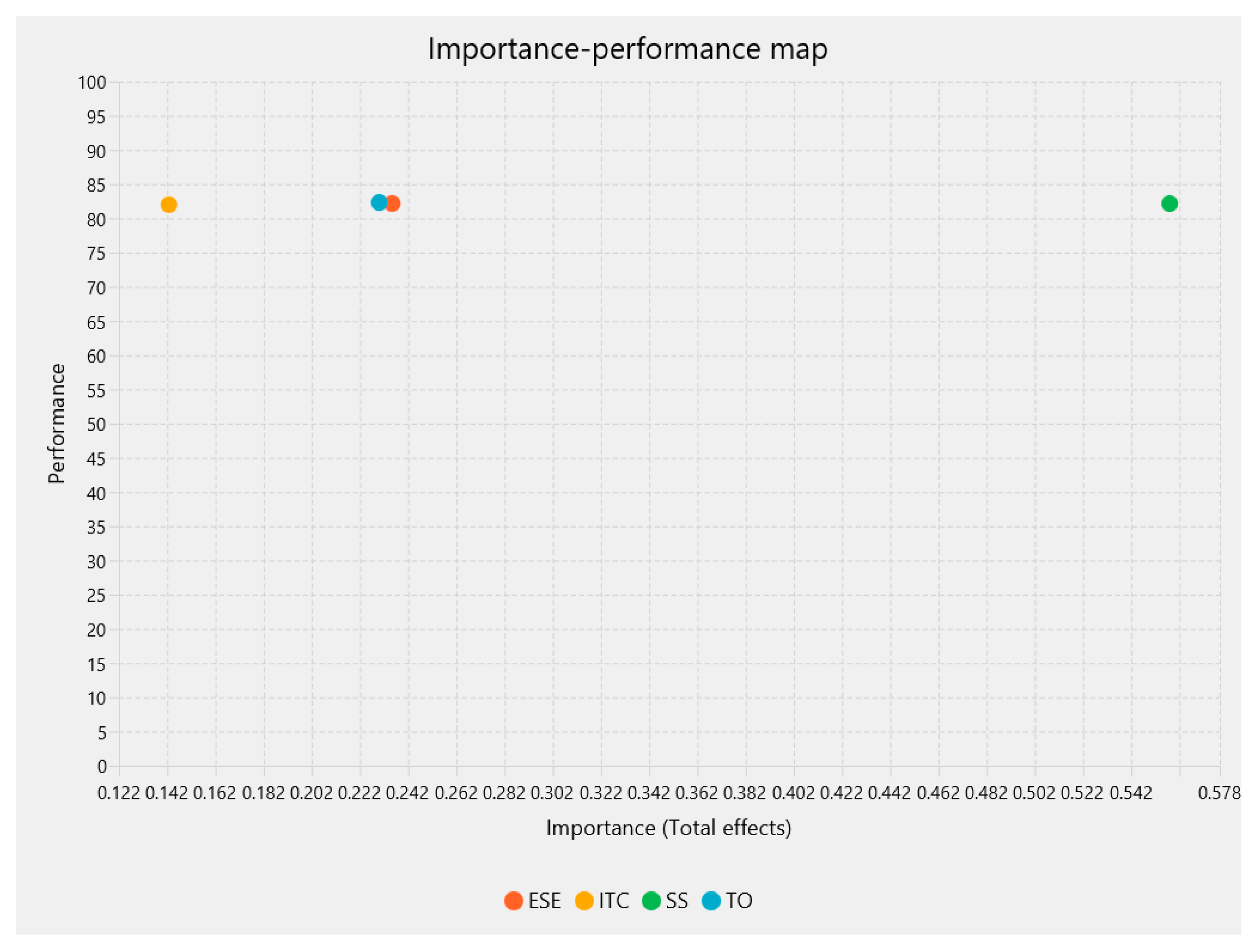

5.3.2. Importance-Performance Map

5.4. Hypotheses Testing in Structural Model

6. Discussion

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

8. Limitations & Directions for Future Research

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Priyanka, R.; Ravindran, K.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Karuppiah, K.; Jaganathan, P. A TISM Decision Modeling Framework for Identifying Key Elements of Organizational Culture in Start-up Companies: Implications for Sustainable Development. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Chaudhuri, R.; Chatterjee, S. Adoption of digital technologies by SMEs for sustainability and value creation: Moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, M.; Kritikos, A.S.; Rodríguez, D.; Stier, C. Self-efficacy and entrepreneurial performance of start-ups. Small Bus. Econ. 2023, 61, 1027–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.Y.; Chi, H.J.; Yang, C.C. Task value, goal orientation, and employee job satisfaction in high-tech firms. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Naudé, W. Destructive digital entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship and Conflict; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 292–328. [Google Scholar]

- Bedda, W.E.; Al-Ashry, H.; Ead, H.A. AI-Enabled Digital Marketing in Startups: A Systematic Review of Global Practices and Egyptian Implementation Challenges. J. Bus. Commun. Technol. 2025, 4, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumangkit, S.; Pradhani, R.A.; Suryanto; Husin, H.; Sentosa, I.; Hadi, A.S. Impact of Technology-Based Service Innovation on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in Luxury Hotels. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Conference on Creative Communication and Innovative Technology (ICCIT), Kota Cirebon, Indonesia, 15–16 August 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Guilherme, A.A.; de Oliveira Cardoso, N.; Ames, J.P.; de Oliveira Pires, M.; de Lara Machado, W. Measuring University Students Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, Intention, Orientation, and Competence: A Systematic Review of Psychometric Instruments. Trends Psychol. 2025, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukanja, M. Examining the Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Self-Efficacy, and Perceived Business Performance on Managers’ Attitudes Towards AI and Its Adoption in Hospitality SMEs. Systems 2024, 12, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.J.J.; Chin, J.W.; Wegner, D.; Nungsari, M. Institutional environments, self-efficacy, outcome expectations and country context: Serial mediating effects on entrepreneurial intentions and decision-making. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2025, 32, 1225–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B.N. Entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial intention: The role of social support and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshashai, D.; Leber, A.M.; Savage, J.D. Saudi Arabia plans for its economic future: Vision 2030, the National Transformation Plan and Saudi fiscal reform. Br. J. Middle East. Stud. 2020, 47, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarrak, M.S.; Alokley, S.A. FinTech: Ecosystem, opportunities and challenges in Saudi Arabia. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, D.; Mathews, M.; D’Costa, R. Youth Entrepreneurship in the Arab World. In Entrepreneurship in the Arab World; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lesinskis, K.; Mavlutova, I.; Spilbergs, A.; Hermanis, J. Digital transformation in entrepreneurship education: The use of a digital tool KABADA and entrepreneurial intention of generation Z. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakre, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Z. The impact of information technology culture and personal innovativeness in information technology on digital entrepreneurship success. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 204–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; AlWadi, B.M.; Kumar, H.; Ng, B.K.; Nguyen, D.N. Digital transformation of family-owned small businesses: A nexus of internet entrepreneurial self-efficacy, artificial intelligence usage and strategic agility. Kybernetes 2025, 54, 6223–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.; Brady, B. A Guide to Youth Mentoring: Providing Effective Social Support; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, H.T.; Beimborn, D.; Weitzel, T. How social capital among information technology and business units drives operational alignment and IT business value. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014, 31, 241–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Agarwal, S.; Tripathi, V. Exploring factors influencing the entrepreneurial intentions of the youth community towards green ICT to encourage environmental sustainability: Evidence from an emerging economy. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2024, 90, e12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewkumpol, N.; Rattanawiboonsom, V.; Yawised, K. The Role of Digital Technology Adoption on Competitive Advantage and Firm Performance: Evidence from Fruit and Vegetable Processing SMEs in Thailand. J. Community Dev. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2025, 18, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larabi, C. Linking intangible resources to predict firm performance through technology innovation and strategic flexibility: Leveraging the resource-based view of the manufacturing firms. J. Strat. Manag. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Adiguzel, Z.; Sonmez Cakir, F.; Karaaslan, N. Examination of the effects of technology orientation, technology innovation strategy and strategic orientation on information technology companies in technoparks. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.N.D.; Nguyen, H.H. Examining the role of family in shaping digital entrepreneurial intentions in emerging markets. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241239493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Perkmen, S.; Toy, S.; Caracuel, A. Extended social cognitive model explains pre-service teachers’ technology integration intentions with cross-cultural validity. Comput. Sch. 2023, 40, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, S.; Bhunia, A.K. A Serial Mediation Model of the Relationship between Digital Entrepreneurial Education, Alertness, Motivation, and Intentions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevill, A.; Trehan, K.; Easterby-Smith, M. Perceiving ‘capability’ within dynamic capabilities: The role of owner-manager self-efficacy. Int. Small Bus. J. 2017, 35, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Dwivedi, A. Digital Entrepreneurship Competency And Digital Entrepreneurial Intention: Role of Entrepreneurial Motivation. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 2310–2322. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, C.D. AI literacy and higher education students’ digital entrepreneurial intention: A moderated mediation model of AI self-efficacy and digital entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Ind. High. Educ. 2025, 09504222251370089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D.; Le, T.T.; Dang, N.S.; Do, N.D.; Vu, A.T. Unraveling the determinants of digital entrepreneurial intentions: Do performance expectancy of artificial intelligence solutions matter? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2024, 31, 1327–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D.; Ngo, T.V.N.; Nguyen, T.P.T.; Tran, N.M.; Pham, H.T. Digital entrepreneurial education and digital entrepreneurial intention: A moderated mediation model. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2024, 10, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloulou, W.; Ayadi, F.; Ramadani, V.; Dana, L.P. Dreaming digital or chasing new real pathways? Unveiling the determinants shaping Saudi youth’s digital entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2023, 30, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzar, J.; Noor, S.; Tajik, O. Convenience sampling. Int. J. Educ. Lang. Stud. 2022, 1, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsudin, M.F.; Hassim, A.A.; Abd Manaf, S. Mastering Probability and Non-Probability Methods for Accurate Research Insights. J. Postgrad. Curr. Bus. Res. 2024, 9, 38–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.K. How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: A simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 12, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmardeh, M.; Mohammed Hasan, A.; Muhammadi, P.; Al-Rashdi, F. A comparative study of gender representation in EFL coursebooks in the Middle East. J. Multicult. Educ. 2025, 19, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.A.E.; Hegazy, R.E. A framework for eradicating women discrimination in architectural design firms in Egypt and GCC countries. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2024, 18, 541–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarni, A. Testing the Construct Validity and Reliability of the Student Learning Interest Scale Using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). J. Penelit. Pendidik. IPA 2024, 10, 6322–6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. The Assessment of Reliability. Psychom. Theory 1994, 3, 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, H.N. Investigation of Intention to Use e-Commerce in the Arab Countries: A Comparison of Self-Efficacy, Usefulness, Culture, Gender, and Socioeconomic Status in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Ph.D. Thesis, Nova Southeastern University, Davie, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Asem, A.; Mohammad, A.A.; Ziyad, I.A. Navigating digital transformation in alignment with Vision 2030: A review of organizational strategies, innovations, and implications in Saudi Arabia. J. Knowl. Learn. Sci. Technol. 2024, 3, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytras, M.D. An integrated transformative learning strategy at national level: Bold initiatives toward vision 2030 in Saudi Arabia. In Active and Transformative Learning in STEAM Disciplines; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 281–296. [Google Scholar]

- Alzamel, S. Building a Resilient Digital Entrepreneurship Landscape: The Importance of Ecosystems, Decent Work, and Socioeconomic Dynamics. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindakis, S.; Aggarwal, S. The entrepreneurial rise and technological innovation in the Middle East and North Africa. In Entrepreneurial Rise in the Middle East and North Africa: The Influence of Quadruple Helix on Technological Innovation; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Aminova, M.; Mareef, S.; Machado, C. Entrepreneurship Ecosystem in Arab World: The status quo, impediments and the ways forward. Int. J. Bus. Ethic-Gov. 2020, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.A.; Hassan, S.; Khan, S.J. Understanding digital entrepreneurial intentions: A capital theory perspective. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 6165–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.S.; Alraja, M.M. Understanding entrepreneurship intention and behavior in the light of TPB model from the digital entrepreneurship perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, C. Digital MENA: An overview of digital infrastructure, policies, and media practices in the Middle East and North Africa. In The handbook of media and culture in the Middle East; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Zayani, M. (Ed.) Digital Middle East: State and Society in the Information Age; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rabl, T.; Petzsche, V.; Baum, M.; Franzke, S. Can support by digital technologies stimulate intrapreneurial behaviour? The moderating role of management support for innovation and intrapreneurial self-efficacy. Inf. Syst. J. 2023, 33, 567–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, N.A.A.; Alkhathlan, K.A.; Haque, M.I.; Alkhateeb, T.T.Y.; Mahmoud, D.H.; Eliw, M.; Adow, A.H. Exploring the Entrepreneurial Intentions of Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University Students and the University’s Role Aligned with Vision 2030. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwale, Y.O.; Alaraifi, A.A.; Ababtain, A.K. Entrepreneurship, innovation, and economic growth: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. In Eurasian Economic Perspectives, Proceedings of the 28th Eurasia Business and Economics Society Conference, Coventry, UK, 29–31 May 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.; Alshallaqi, M. Exploring the impact of economic, social, and environmental factors on sustainable entrepreneurial intentions and behavior: Insights for advancing sustainable development. J. Strategy Innov. 2025, 36, 200550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J. The effect of computer self-efficacy on the behavioral intention to use translation technologies among college students: Mediating role of learning motivation and cognitive engagement. Acta Psychol. 2024, 246, 104259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloulou, W.J.; Al-Othman, N. Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. In Entrepreneurship in the Gulf Cooperation Council Region: Evolution and Future Perspectives; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2021; pp. 111–145. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.B.; Iqbal, S.; Hameed, I. Entrepreneurship (in light of Vision 2030). In Research, Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia: Vision 2030; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.U.; Arefin, M.S.; Yukongdi, V. Personality traits, social self-efficacy, social support, and social entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of gender. J. Soc. Entrep. 2024, 15, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almobaireek, W.N.; Manolova, T.S. Entrepreneurial motivations among female university youth in Saudi Arabia. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2013, 14 (Suppl. S1), S56–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Khan, M.B.; Shahab, A.; Hameed, I.; Qadeer, F. Science, technology and innovation through entrepreneurship education in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Sustainability 2016, 8, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauceanu, A.M.; Alpenidze, O.; Edu, T.; Zaharia, R.M. What determinants influence students to start their own business? Empirical evidence from United Arab Emirates universities. Sustainability 2018, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, A.S.; Fazal, S.A.; Seraj, A.H.A.; Al Marri, S.H.; Alsultan, W.S. Fostering potential entrepreneurs: An empirical study of the drivers of green self-efficacy in Saudi Arabia. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.; Abubakar, A.A.; Abdulmohsen Alfalah, A. The effect of psychological, market, economic, socio-cultural, entrepreneurial orientation and educational and skills factors on empowering women for new venture creation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Scale | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 338 | 90.9 | |

| Female | 34 | 9.1 | |

| Total | 372 | 100 | |

| Education | Scale | Frequency | Percent |

| Diploma after Higher School | 5 | 1.3 | |

| Higher School | 112 | 30.1 | |

| Bachelor | 253 | 68 | |

| Postgraduate | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Total | 372 | 100 | |

| Age | Scale | Frequency | Percent |

| Less than 30 | 370 | 99.5 | |

| 31–40 | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Total | 372 | 100 |

| S/n | Constructs | Items | FL | CA | CR (rho_a) | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Information Technology Culture (ITC) | ITC1 | 0.883776 | 0.947968 | 0.948484 | 0.793518 |

| ITC2 | 0.891991 | |||||

| ITC3 | 0.894797 | |||||

| ITC4 | 0.89132 | |||||

| ITC5 | 0.894061 | |||||

| ITC6 | 0.888787 | |||||

| 2 | Technology Orientation (TO) | TO1 | 0.872661 | 0.947868 | 0.949548 | 0.793554 |

| TO2 | 0.901727 | |||||

| TO3 | 0.907919 | |||||

| TO4 | 0.854209 | |||||

| TO5 | 0.91418 | |||||

| TO6 | 0.892726 | |||||

| 3 | Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE) | ESE1 | 0.909978 | 0.954673 | 0.95543 | 0.81539 |

| ESE2 | 0.907409 | |||||

| ESE3 | 0.907295 | |||||

| ESE4 | 0.923928 | |||||

| ESE5 | 0.887712 | |||||

| ESE6 | 0.880926 | |||||

| 4 | Social Support (SS) | SS1 | 0.881045 | 0.956595 | 0.956913 | 0.821868 |

| SS2 | 0.914868 | |||||

| SS3 | 0.904748 | |||||

| SS4 | 0.921522 | |||||

| SS5 | 0.89626 | |||||

| SS6 | 0.920289 | |||||

| 5 | Sustainable digital entrepreneurship Intention (DEI) | DEI1 | 0.876707 | 0.951659 | 0.952298 | 0.805661 |

| DEI2 | 0.909262 | |||||

| DEI3 | 0.904827 | |||||

| DEI4 | 0.913206 | |||||

| DEI5 | 0.913824 | |||||

| DEI6 | 0.866523 |

| DEI | ESE | ITC | SS | TO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEI | 0.897586 | ||||

| ESE | 0.80963 | 0.90299 | |||

| ITC | 0.820236 | 0.828774 | 0.890796 | ||

| SS | 0.811037 | 0.812608 | 0.826071 | 0.906569 | |

| TO | 0.840955 | 0.832159 | 0.810339 | 0.848964 | 0.890817 |

| S/n | Items | R-Square |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | DEI | 0.854601398 |

| 2 | ESE | 0.814656171 |

| S/n | Relationship | Std. Beta | Std. Dev | (t-Values) | p-Values | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ITC -> DEI | 0.065 | 0.076 | 0.852 | 0.197 | Not Supported |

| H2 | TO -> DEI | 0.091 | 0.096 | 0.950 | 0.171 | Not Supported |

| H3 | ITC -> ESE -> DEI | 0.078 | 0.034 | 2.256 | 0.012 | Supported |

| H4 | TO -> ESE -> DEI | 0.139 | 0.067 | 2.083 | 0.019 | Supported |

| H5 | ESE -> DEI | 0.235 | 0.100 | 2.362 | 0.009 | Supported |

| H6 | SS x ESE -> DEI | −0.006 | 0.023 | 0.270 | 0.394 | Not Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Mamary, Y.H.; Abubakar, A.A.; Jazim, F. Towards Sustainable Digital Entrepreneurship: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and the Moderating Influence of Social Support. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310499

Al-Mamary YH, Abubakar AA, Jazim F. Towards Sustainable Digital Entrepreneurship: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and the Moderating Influence of Social Support. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310499

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Mamary, Yaser Hasan, Aliyu Alhaji Abubakar, and Fawaz Jazim. 2025. "Towards Sustainable Digital Entrepreneurship: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and the Moderating Influence of Social Support" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310499

APA StyleAl-Mamary, Y. H., Abubakar, A. A., & Jazim, F. (2025). Towards Sustainable Digital Entrepreneurship: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and the Moderating Influence of Social Support. Sustainability, 17(23), 10499. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310499