1. Introduction

E-commerce of organic products has become an area of exponential growth, driven largely by digitalisation during the pandemic; the emergence of chatbots, voice search and live commerce [

1]; and increased concern for responsible consumption [

2]. This boom poses significant challenges, including the growing contradiction between the convenience offered by digital platforms and consumer concerns about privacy. The extensive collection of data on purchasing behaviour and location exposes consumers to potential breaches of their personal information, which increases perceived risk and weakens trust in digital environments [

3].

Along these lines, Lee et al. [

4] warn that while enhancing transparency through the disclosure of environmental information may increase the credibility of the offer, it also increases the exposure of personal data to third parties, which ultimately erodes consumers’ initial trust. To understand this complex balance between transparency, control and trust, various studies have turned to Social Cognitive Theory (SCT). Afolabi et al. [

5], for example, explored the relationship between privacy concerns, perceived risk, and control over information and trust, showing that the latter directly influences behavioural intention. In the specific context of green consumption, the influence of trust on the intention to purchase sustainable products has been confirmed [

6], as well as in online shopping environments [

7], reinforcing the relevance of this theoretical approach for the study of green e-commerce.

E-commerce for organic products poses an additional requirement for trust because the product’s “credibility” attributes (e.g., organic certification, origin, environmental impact) are not easily verifiable at the time of purchase. Therefore, consumers rely heavily on trust in the website or supplier, as well as credible informational signals, to reduce uncertainty and foster purchase intention [

8,

9] to drive online purchases [

10].

Although previous studies have linked SCT factors to trust and online purchase intention, evidence remains limited in the context of organic product e-commerce and rarely integrates risk and privacy control alongside social influence and perceived usefulness within a single model. Our extended SCT framework explicitly combines these cognitive and social variables, thereby going beyond prior applications that typically focused on either social influence or privacy-related constructs in isolation.

On the other hand, despite the growing prominence of information and communication technologies (ICT) in digital consumer environments [

11], research specifically focused on the role of gender in relation to these technologies remains limited [

12,

13]. Gender role theory suggests that women tend to be more relationship-oriented, placing greater importance on social cues and normative approval, while men tend to be more task-oriented and respond better to utilitarian risks [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Therefore, the expanded SCT model, which includes social influence, is particularly relevant as it takes into account the subjective norm aspect, which will help us to verify whether social influence affects women more, while risk-related factors affect men more [

18]. Although some studies have addressed gender differences in the usability of online travel agency websites [

19] or in work behaviour within sectors such as catering [

20], there is little research analysing how gender influences interaction with digital purchasing platforms, particularly in contexts linked to green consumption. Exploring these differences can provide relevant insights for the design of more inclusive and tailored applications that respond to specific gender preferences and contribute to improving the user experience in sustainable e-commerce.

This paper addresses a gap in the literature by examining the extent to which perceived usefulness, social influence, and privacy factors extend the explanatory power of the original SCT framework [

21,

22,

23] to anticipate trust in websites and providers of eco-friendly products and, consequently, behavioural intentions, such as purchase intention. To this end, information was collected through online surveys of 821 users. By jointly modelling website trust and provider trust as dual antecedents of online purchase intention, our study provides an integrated view of how social influence and privacy-related factors shape organic e-commerce, a combination that, to our knowledge, has not been tested empirically before.

This study also examines differences in the perception of these cognitive and social factors according to consumer gender. The importance of this study lies in understanding how males and females experience and relate to technology differently. This can help in adapting marketing strategies, using advertising segmentation, and personalising the privacy services of applications and platforms to meet the specific needs and preferences of each gender. Furthermore, by understanding these differences, more inclusive and equitable practices can be promoted, creating more satisfying and enriching experiences.

In line with the above, this study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: How do privacy-related and social cognitive factors jointly shape trust in websites and providers in the context of organic e-commerce?

RQ2: Do these mechanisms differ between males and females in terms of their impact on trust and online purchase intention?

2. Theoretical Framework

Sustainable consumers prioritise aspects such as health, the environment and ethical values in their purchases. These aspects have been shown to be key drivers of organic product purchases [

24]. For example, studies on natural cosmetics also point to this trend: consumers, especially younger and more educated ones, are increasingly aware of the environmental impact of their purchases and choose organic and eco-certified products [

25]. In addition, events such as the pandemic have reinforced the demand for healthy and green goods: many consumers have become more thoughtful about their purchasing habits, opting for items that promote personal and environmental health [

24]. Likewise, personal experiences related to recommendations from family and friends are decisive when it comes to purchasing goods [

18]. All of this highlights the orientation towards sustainable consumption based on motivations related to health and social well-being, which are mediated by personal influence and personal values.

However, despite these factors having been studied in depth, challenges remain in the adoption of organic products. Azizan et al. point out that, despite positive attitudes towards organic products, barriers such as high prices, limited accessibility and a lack of confidence in certifications are delaying their adoption [

24].

Sustainable consumption trends have also been analysed in the field of e-commerce. Teerapong and Sawangproh studied the intention to purchase plant-based foods online and showed that trust in the digital brand, social influence (e.g., recommendations on social media) and perceived product value significantly explain this purchase intention. In fact, in their model, trust in the online store was the most influential factor in purchasing decisions for eco-friendly products. In addition, these authors highlight that consumer self-efficacy further strengthens this purchase intention in the digital environment [

10].

Findings on the role of gender in sustainable consumption are mixed. On the one hand, several studies indicate that women tend to consume more eco-friendly products than men. For example, Magnusson et al. and Rimal et al. [

15,

26,

27] reported that women have a greater preference for organic foods than men. In a recent study of American consumers, Gundala et al. [

15] showed that gender moderates certain relationships in the sustainable purchasing model: specifically, the attitude-purchase intention relationship and the subjective norm-purchase intention relationship behaved differently for men and women when purchasing organic foods.

SCT is one of the leading theories for the study of human behaviour [

28]. It proposes that learning takes place in social contexts through the interaction between the person, the environment and behaviour [

29]. In this framework, learning, motivation and behaviour processes result from the reciprocal causality between personal and cognitive, behavioural and environmental factors [

30]. Thus, internal determinants, environmental influences and cognitive, affective and biological events affect each other bidirectionally and condition decision-making [

31,

32]. In particular, individual factors (knowledge, experiences, attitudes, and psychological states) influence behaviour, while external factors (the social and physical environment) also act as predictors [

33]. The social environment comprises the individual’s closest relationships [

34], and the physical environment includes natural and built elements [

35].

The selection of SCT is justified for two reasons. First, although the literature has used this framework to study trust and incorporate social influence and perceived usefulness as predictors of trust in technological contexts [

5,

22,

36,

37], a gap has been detected in the existing literature in that these factors have not been integrated together with control and perceived risk within an SCT framework for e-commerce of organic products. Second, gender differences in these processes have received little attention in sustainable consumption contexts. We fill this gap by proposing and testing a unified SCT-extended model explaining trust in website/provider and online purchase intention of organic products, and by formally testing gender as a moderator of the key structural path.

2.1. Trust on the Website and the Supplier

In recent years, online security breaches have grown exponentially, causing privacy concerns to become a key issue for consumers [

38]. In the context of websites or applications, trust plays a key role in reducing privacy risks related to service providers [

39]. Therefore, in a technological context, it is necessary to assess privacy concerns, perceived risk to privacy and perceived control, as well as their impact on people’s trust in a website.

Privacy issues can be understood as concerns that third parties may share or access personal information without permission, or use it in unauthorised ways [

40]. Rapid technological advances and the proliferation of mobile devices have increased privacy risks, leading to widespread misuse of personal data by various entities, which undermines the credibility of companies [

41]. Lack of consumer trust in service providers to properly access, use, and store their personal information can lead to reluctance to connect with online retail providers [

42]. On this basis, it is understood that significant concerns about a person’s privacy when browsing the internet will decrease trust in the website and green product providers. Therefore, it is established that

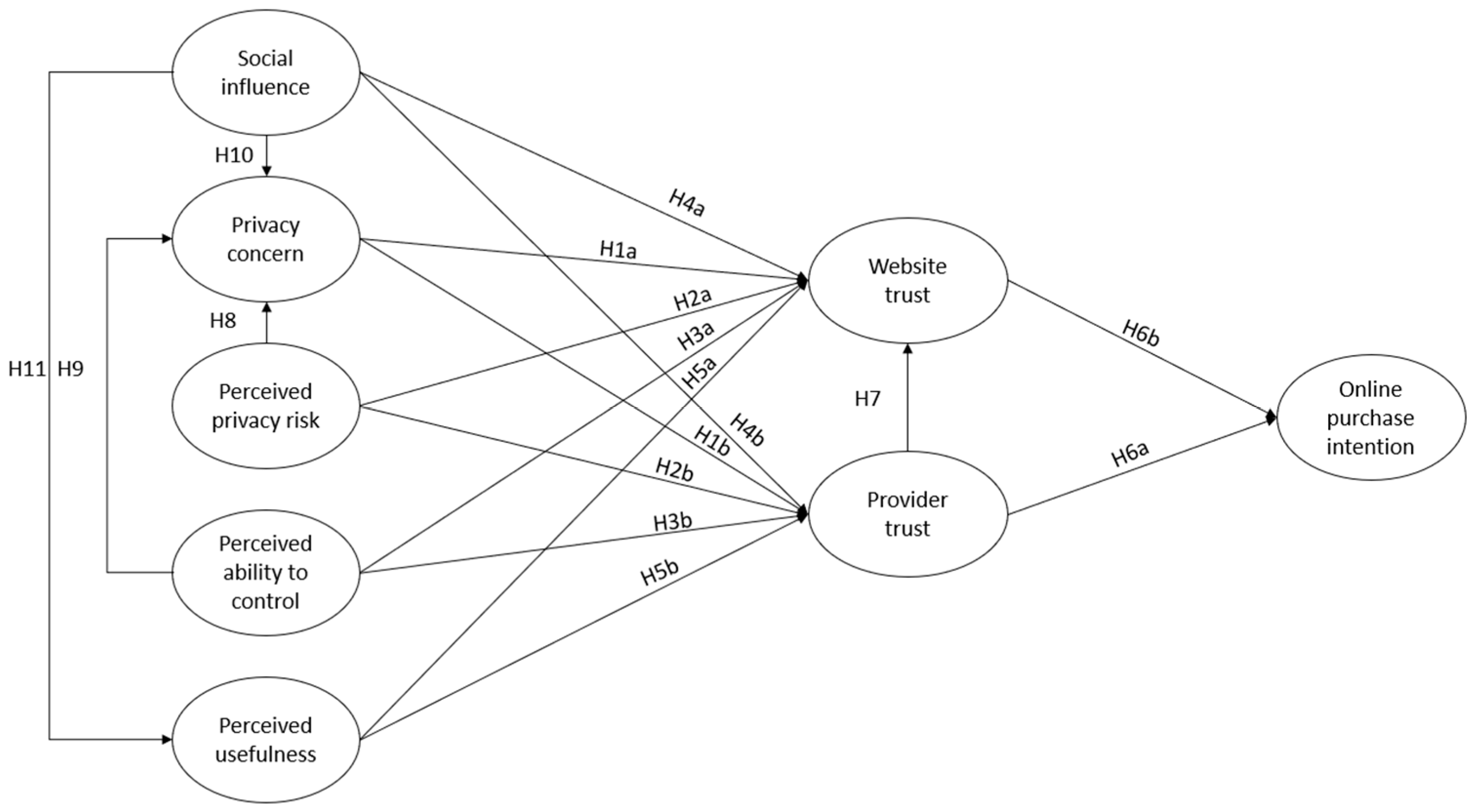

H1: Privacy concerns have a negative impact on website trust (a) and supplier trust (b).

Furthermore, perceived privacy risk is the risk that users perceive when using online communication [

43]. This variable identifies the fear that exists in the user’s mind regarding the loss of confidential information [

44]. The risk associated with the use of personal information has been identified as a key concern among users [

45] tending to prefer websites that provide privacy [

46]. In turn, three sources of risk have been identified in e-commerce transactions: technology, the supplier, and the product or service, which directly affect the risk perceived by consumers [

47,

48]. Several studies have shown that perceived privacy risk has a negative impact on trust [

5,

49]. Therefore, it is understood that when people perceive that their personal information is at risk while purchasing organic products, they will have lower levels of trust in companies and websites due to the concern they will experience as a result of the violation of their right to privacy. In this regard, it is established that

H2: Perceived privacy risk has a negative impact on website trust (a) and supplier trust (b).

Furthermore, perceived control can be understood as the perceived ability of users to decide what personal information is used or not [

50]. People have a natural desire to control their privacy and avoid losing control of their personal information [

51]. Therefore, consumers who have control over the personal information they share will trust service providers more [

52]. We therefore propose that greater consumer control over the personal information they share will lead to greater trust in online companies and service providers, as consumers will know at all times exactly what data is being offered and shared with those companies. Thus, it is established that

H3: Perceived control has a positive impact on trust on the website (a) and in the provider (b).

On the other hand, social influence refers to how the opinions and expectations of people who are important to someone affect their decisions about what they should or should not do [

53]. This influence usually comes from people known to the individual, such as family members and friends [

54,

55]. Social influence plays an important role in behavioural intention [

56,

57] and influences levels of trust, especially in online activities [

58]. When people perceive positive opinions from their social circles regarding the adoption of technology, they are likely to share the same opinion [

59]. Li et al. [

60] highlight the importance of social influence on cognitive factors for the initial development of trust. Although some studies claim a positive correlation between social influence and trust [

22] this link remains unexplored in e-commerce contexts for organic products. Therefore, it is established that

H4: Social influence has a positive impact on website trust (a) and supplier trust (b).

Finally, perceived usefulness is the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would improve their performance or experience [

61]. If consumers believe that using an app or website for selling organic products is useful, they will have a higher level of trust in that service provider [

62]. The individual perception of the usefulness of a website or application in terms of security, reliability and accuracy is an essential element of trust among consumers [

63]. From this perspective, the usefulness of an application or website must first be demonstrated in order for consumers to trust it [

64].

Furthermore, it has been found that perceived usefulness has a positive effect on trust in different contexts, for example, in AI-based smart health services [

65]. Therefore, it is understood that trust will increase if consumers perceive the shopping app or website of an organic product provider as useful. Therefore,

H5: Perceived usefulness has a positive impact on website trust (a) and supplier trust (b).

2.2. Influence on Behavioural Intentions

Trust is a critical factor in purchase decision-making and behaviour. It is defined as “a psychological state in which individuals are willing to accept vulnerability based on their positive expectations about another person’s intentions or behaviour” [

66]. Trust fosters long-term relationships by reducing users’ uncertainty when adopting risky behaviours [

67].

The relationship between trust and behavioural intentions has been widely explored in the literature. In the field of food services, trust has been found to significantly influence consumer loyalty [

68,

69] and willingness to recommend the service [

70]. In the context of online shopping, a direct link has also been identified between trust and behavioural intentions [

7]. Therefore, trust in the website may precede the intention to purchase products online [

71]. Considering the above, higher levels of trust will increase consumers’ intention to make online purchases due to a greater sense of trust in the services offered in terms of customer service, quality and dedication. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6: Trust in the supplier (a) and on the website (b) has a positive impact on the intention to make an online purchase of organic products.

H7: Trust in the supplier has a positive impact on trust on the website.

2.3. Influence on Privacy Concerns and Perceived Usefulness

In addition, it has been found that privacy concerns are assessed by factors such as perceived control and perceived privacy risk [

72]. Today, the personal information of Internet users is often exposed and used without authorisation [

73]. This raises privacy concerns due to the associated risks and lack of control over one’s personal information [

72]. Recent studies have demonstrated the positive influence of perceived privacy risk [

49] and the negative influence of perceived control [

74] for privacy reasons. Therefore, it is established here that consumers who are risk-averse with regard to their personal data will be more cautious about their privacy. However, if they have control over the information they provide, they will be less concerned. On this basis, it is hypothesized that

H8: Perceived privacy risk has a positive impact on privacy concerns.

H9: Perceived controllability has a negative impact on privacy concerns.

Similarly, it has been found that social influence affects individuals’ decision-making [

75] and that public opinion has a significant effect on the value of privacy [

76]. Various studies have pointed out that social norms have a positive effect on privacy concerns. In turn, social influence has been found to be a determinant of the perceived usefulness of a system [

77]. However, empirical evidence on the link between social norms and privacy concerns remains mixed. In highly sensitive contexts, individual risk assessments and perceptions of control may override normative pressure, so that social approval does not necessarily translate into lower privacy concerns [

72,

73,

76]. Therefore, it is understood that the positive opinions, comments, and reactions of consumers’ close social contacts will reduce their privacy concerns and lead to greater perceived usefulness of the apps and websites of online providers of eco-friendly products. Thus, the final hypotheses proposed are as follows:

H10: Social norms have a negative impact on privacy concerns.

H11: Social norms have a positive impact on perceived usefulness.

2.4. Research Hypothesis Development on Gender Differences

The interaction between sociodemographic variables and SCT has been little used in the e-commerce literature [

78,

79]. Taking into account all sociodemographic variables, gender has been considered one of the main determinants of purchasing behaviour intentions [

14,

80]. These differences have been studied in different disciplines, such as marketing [

81], mobility [

82], economics [

83] and tourism [

84].

Females and males have different interests and needs that are shaped by their different environments and social constraints [

85]. Therefore, they develop different preferences, attitudes and behaviours that are reflected in society, ethics and culture [

19,

86]. In the field of e-commerce, researchers have found that gender differences have a significant impact on consumers’ cognition, emotions, experience, and decision-making [

87,

88].

Gender cognitive differences affect people’s preferences, information seeking, and website navigation [

19]. For example, deeply rooted cultural beliefs and stereotypes can contribute to gender differences in technology use and computer literacy [

89]. Males tend to be more task-oriented, and females more relationship-oriented, which has implications for how each gender processes, evaluates, retrieves information, and makes judgements [

90].

Gender differences have been shown to play an important role in the adoption of ICTs [

91]. Traditionally, females have a lower perception of their ICT skills [

92]. On the other hand, males are more likely to trust websites [

93] and have greater self-efficacy in terms of system use [

94] which can lead to greater management with regard to ICT use.

Similarly, females are more likely to use more available information in the decision-making process than males, who only use certain information before making a decision. This leads to faster decision-making by males [

95]. Despite numerous studies on gender differences in e-commerce [

87,

88], very little attention has been paid to the study of gender differences in e-commerce for organic products and their influence on purchase intentions.

In particular, Abubakar et al. [

71] investigated the moderating impact of gender in the medical tourism sector; Maddux and Brewer [

96] examined differences in interdependence within the domain of trust; and Landhari and Leclerc [

97] analysed how loyalty towards banking service providers differs between males and females. In this regard, it has been highlighted that females have higher perceptions than males regarding energy saving [

98] and the potential risks associated with space travel [

99].

In sustainable e-commerce contexts, this implies that social cues (e.g., subjective norms) would influence women more, while men would be more influenced by cognitive risk assessments. For example, Teangsompong and Sawangproh [

10] show that trust is the factor that has the greatest impact on the intention to purchase sustainable products.

Investigating gender differences in perceptions of the sale of eco-friendly products in e-commerce is crucial to addressing disparities in the sector. Perceptions inform gender-specific policies, improve strategies, and adapt features, driving review intentions. Understanding divergent perceptions improves marketing and promotes gender equality, increasing engagement and satisfaction for all users. Drawing on gender role theory, females are typically described as more relationship-oriented and communal, which increases their sensitivity to social cues and normative approval, whereas males tend to adopt more task-oriented and agentic roles, giving greater weight to risk, control and performance-related information. In sustainable e-commerce contexts, this implies that social cues (e.g., subjective norms and recommendations) are likely to exert a stronger influence on females’ trust formation, while males’ trust may be more strongly shaped by perceived privacy risks and their perceived ability to control data and transactions [

12,

14,

17].

H12: The impact of social influence (a), privacy concern (b), perceived privacy risk (c), perceived ability to control (d), and perceived usefulness (e) on website trust is greater for females than for males.

H13: The impact of social influence (a), privacy concern (b), perceived privacy risk (c), perceived ability to control (d) and perceived usefulness (e) on trust in the provider is greater for females than for males.

H14: The impact of trust in the website (a) and in the provider (b) on the intention to purchase organic products online is greater for females than for males.

3. Methodology

Data collection was carried out through an online survey of organic product consumers. A random sampling method stratified by gender and age group was used to ensure the representativeness of different population segments. In practice, the survey was distributed through a national online consumer panel, inviting only people who reported having purchased or consumed organic products at least occasionally (a criterion to ensure the relevance of the questions). Spain was selected because it is a mature European market with high penetration of organic products [

24]. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with respondents being informed of the study’s objective and giving their informed consent at the start of the questionnaire. During the fieldwork (August to November 2024), 850 responses were obtained, of which 821 were valid and used in the analysis (after discarding 29 questionnaires due to incompleteness or inconsistencies in the responses, thus ensuring data quality). The final sample showed a slight male predominance (53.6% men, 46.4% women) with an average age of 33, ranging from young adults to those over 50. In terms of education, 39.4% had a university degree, 18.3% had technical training, 12.4% had secondary education and 12.3% had a high school diploma, among other levels. The declared monthly income was mainly concentrated in the €1000–3000 range (55.3% of participants), while 43.5% earned less than €1000 and 1.3% earned more than €3000. These characteristics (summarised in

Table 1) indicate that the sample includes a diversity of sociodemographic profiles. To ensure the quality of the information collected, in addition to the aforementioned pilot test, the research team carefully monitored the consistency of the responses and complied at all times with ethical principles and current data protection legislation. Thanks to these procedures, a reliable and representative data set is available to test the hypotheses put forward.

The questionnaire consisted of an introduction and three thematic sections. The introduction outlined the research objectives and ensured compliance with data protection laws.

Section 1 covered attitudes and preferences regarding privacy, including perceived usefulness, subjective norms, privacy concerns and perceived control.

Section 2 focused on trust in organic product providers and the website.

Section 3 collected sociodemographic data such as age, gender, income and educational level. A 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) was used, with items phrased in positive terms to facilitate understanding and with specific adjustments for privacy-related variables.

Table 2 presents the scales used and their bibliographic references. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to assess the unidimensionality of the scales.

Data Analysis

SPSS 28 and AMOS 28 software were used for data analysis, which was performed using the maximum likelihood algorithm. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed, followed by a structural equation model (SEM), following Anderson and Gerbing [

106]. Fit indices such as χ

2, NFI, GFI, CFI and RMSEA were evaluated, seeking values close to 0.9 or 1.0 for NFI, GFI and CFI, and between 0.05 and 0.08 for RMSEA. The results confirmed the validity and reliability of the measurement model, supported by quadratic correlations greater than AVE between latent variables and significant correlations between constructs in the correlation matrix (

Table 3 and

Table 4).

5. Discussion, Implications and Conclusions

This study aimed to use an extended model of the SCT to analyse consumers’ intention to purchase organic products online, integrating variables such as privacy, perceived usefulness of tourism applications, social influence and trust in suppliers and the website. In addition, a theoretical model was proposed and developed to understand gender differences in privacy, perceived usefulness, social influence, trust and purchase intention, providing a holistic perspective of these constructs in males and females.

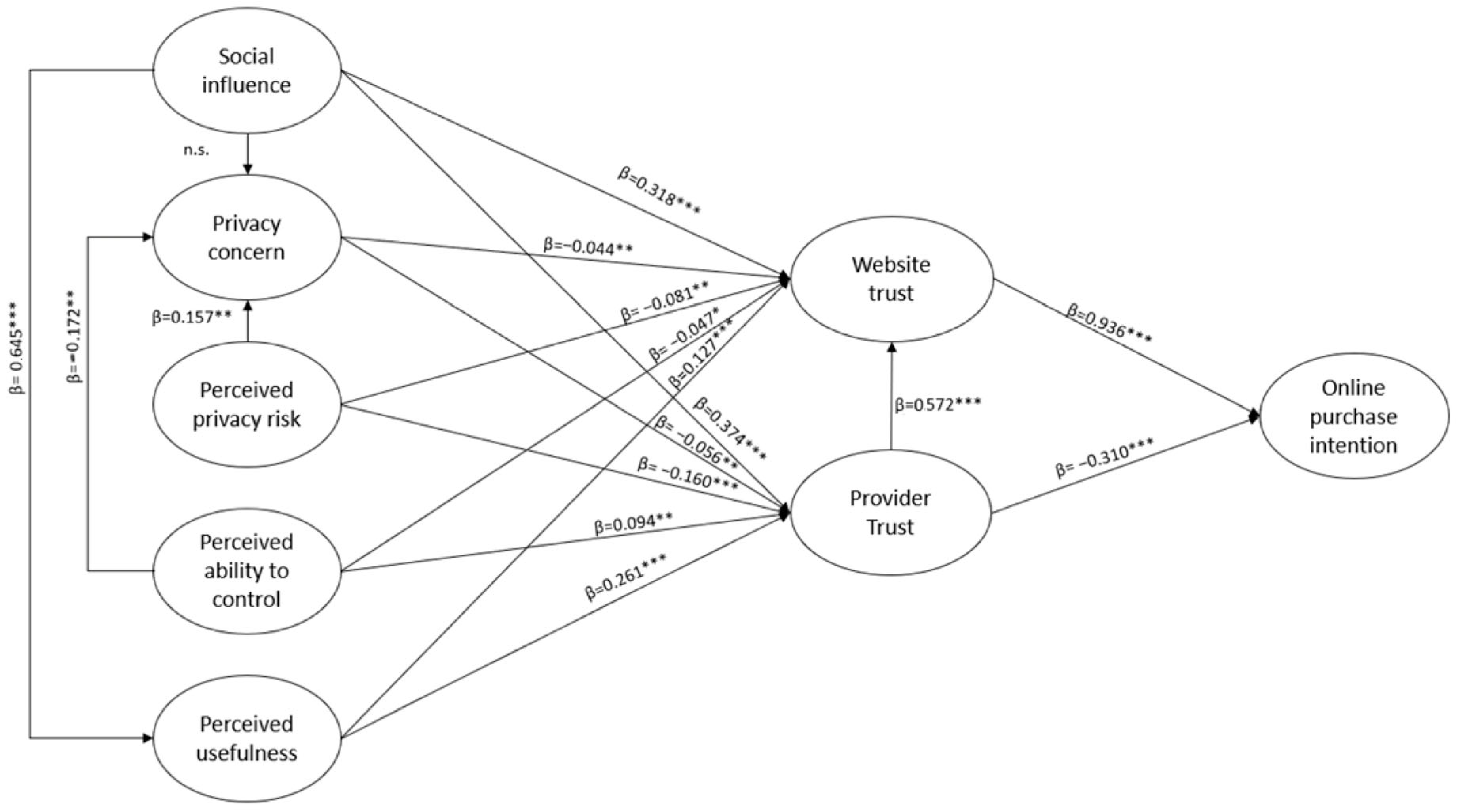

The results confirm that privacy concerns are a significant negative determinant of trust (H1a, H1b) [

5] and that perceived privacy risk also has a negative effect on trust (H2a, H2b) [

5,

112]. Conversely, perceived control over information has a positive effect on trust (H3a, H3b) [

5,

113]. The strong positive effect of social influence on both types of trust (H4a, H4b) is consistent with findings in organic and plant-based online contexts, where recommendations and social cues significantly enhance trust and purchase intention [

6,

10].

Perceived usefulness is positively related to trust (H5a, H5b) [

65]. As for the other effects, both dimensions of trust are positively linked to online purchase intention (H6a, H6b) [

6,

7,

114], and trust in the supplier improves trust in the website (H7). Among the antecedents, privacy concerns decrease when perceived control increases (H8) and increase when perceived privacy risk increases (H9), while social influence does not significantly affect privacy concerns (H10); social influence positively affects perceived usefulness (H11) [

49,

73,

115]. By contrast, H10 was not supported, as social influence did not significantly reduce privacy concerns. This suggests that, in organic e-commerce, privacy worries are primarily driven by individual risk perceptions and perceived control rather than by social approval, which is consistent with studies showing that privacy decisions often reflect personal cost–benefit evaluations even in socially rich environments. This may be because privacy concerns in e-commerce tend to be driven by individual risk perceptions rather than social approval. For example, Statista [

116] reports that around 74% of online consumers are very concerned about privacy.

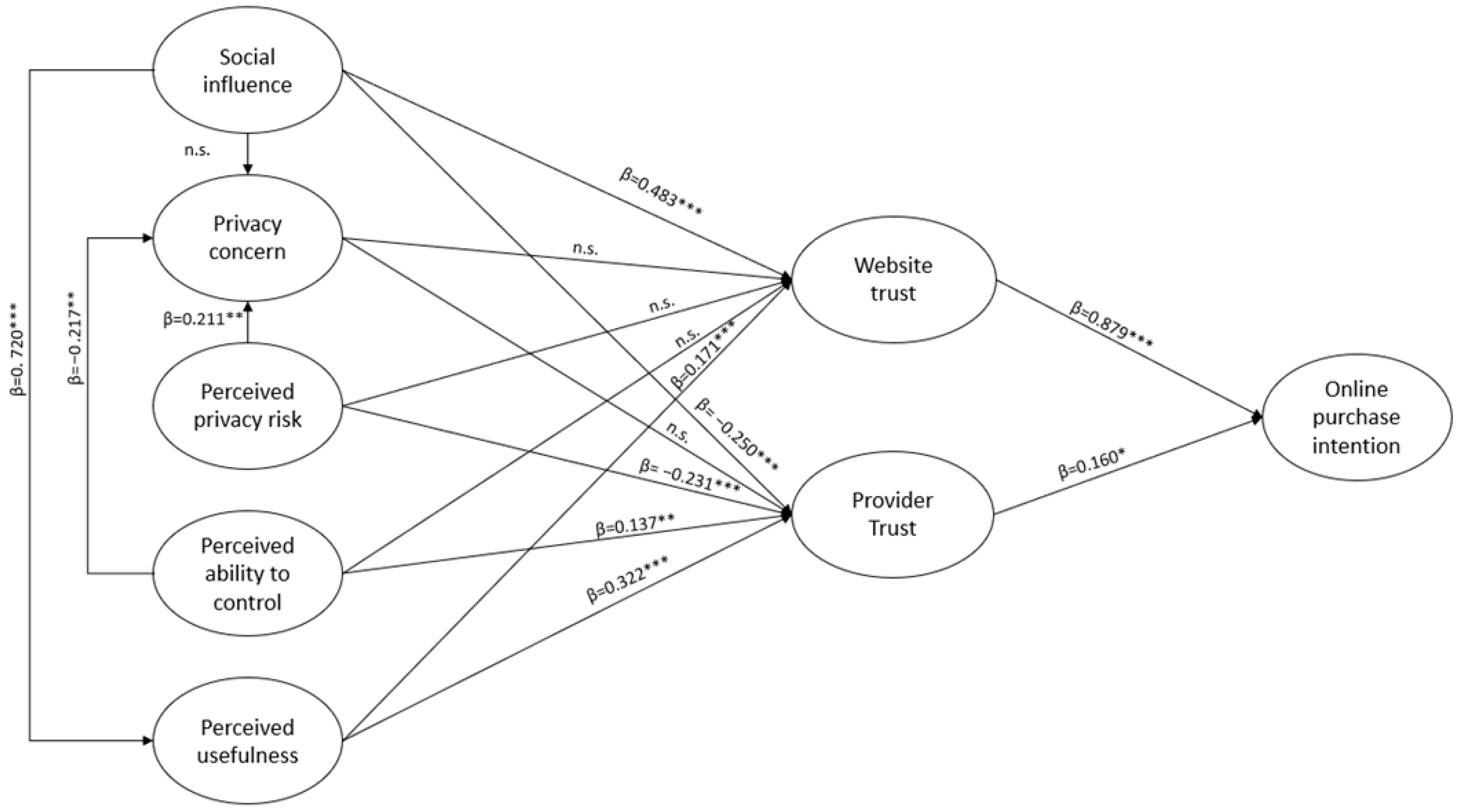

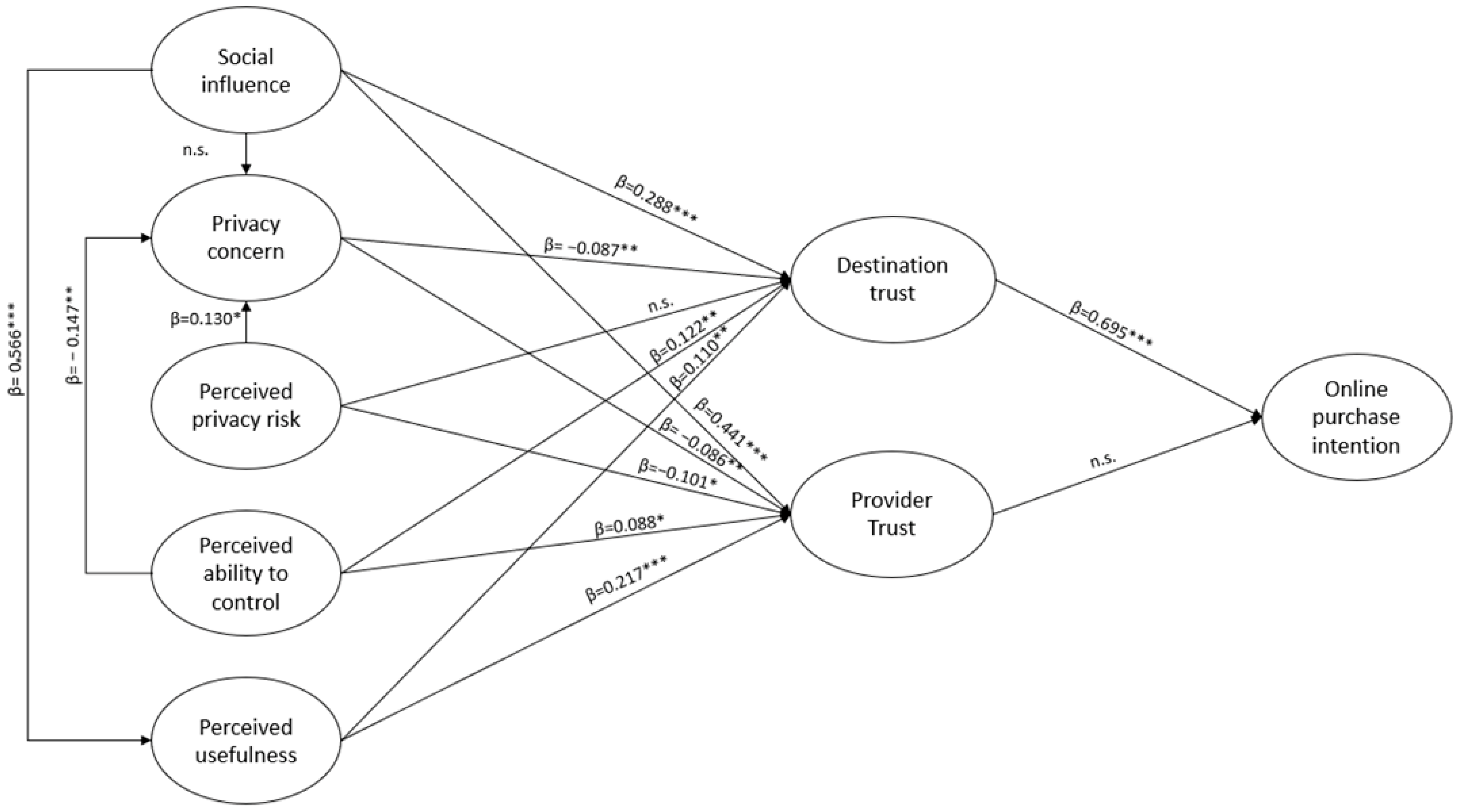

Multigroup analysis reveals asymmetries in significance across relationships. Mostly, the effects are significant for men but not for women; where the routes are significant in both groups, women often show stronger coefficients. For instance, privacy concern significantly undermines website trust only for males (H12b), which may reflect a more task- and security-oriented evaluation style: when men feel that their data are not sufficiently protected, they penalise the transactional platform more strongly. In contrast, perceived privacy risk and provider trust play a more salient role among females (H13c, H14b) [

92,

93]. This pattern is consistent with gender role theory and prior work suggesting that females place greater emphasis on relational aspects and on the credibility of human or organisational agents behind digital platforms, especially when products are credence goods such as organic products that cannot be fully verified at the point of purchase [

19,

97].

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study incorporates new variables such as social influence [

21,

22,

23] and perceived usefulness [

63,

65,

117] which improves the explanatory power of purchase intention through SCT. Although previous studies have also expanded this model using social influence and perceived usefulness variables in relation to trust, this has never been done for e-commerce of organic products, which is one of the main contributions of the present study.

It should also be noted that the components of the SCT model (privacy concern, perceived privacy risk, perceived control, social influence and perceived usefulness) explain 46.3% of the intention to purchase organic products online. This explanatory power, which is higher than that reported in previous studies (31%) [

7], distinguishes and reinforces the contribution of this study.

In terms of gender, the proposed constructs explained 35.7% of the variance in the behavioural intention of male consumers and 56.5% in female consumers. This implies that females are more willing to trust and purchase organic products online, considering the antecedent variables of the proposed model.

5.2. Social and Management Implications

This study offers numerous social and management implications that should be taken into account by companies selling organic products online. Las recomendaciones se organizan en cuatro grupos prioritarios: privacidad, confianza, diseño de plataforma y estrategias de marketing.

First, managers should replace generic notices with features that increase control when data is requested or shared, such as implementing one-click privacy presets that group together options for cookies, tracking and communication options, real-time alerts about what data is being shared, and allowing access to be revoked at any time, and providing a privacy dashboard with export/delete tools, retention periods and a permission history.

Given that concern and perceived risk can erode trust, it would be advisable to offer options that allow users to control the data shared during registration, payment and account management. For female consumers, managers could design a concise ‘privacy summary’ page that visually explains what data are collected, why they are needed, and how they can be modified, together with a one-click option to adjust all privacy settings. For male consumers, emphasising concise security badges (e.g., encryption standards and audit seals) and a ‘quick checkout’ option with pre-saved privacy preferences can help maintain a smooth, efficiency-oriented transaction experience.

It has been shown that trust in the website has a decisive influence on purchase intent, and that trust in the seller significantly reinforces it. For this reason, trust must be strengthened in both the product and communication layers. It is advisable to explicitly provide evidence of regulatory compliance, such as publishing GDPR statements and displaying accreditations (e.g., ISO/IEC 27001 and ISO/IEC 27701), as well as implementing two-factor authentication systems or the use of passkeys, together with a clear incident response policy.

It is also essential to show signs of reliability and fairness, such as transparent refund policies, delivery statistics, and verified purchase reviews. In the case of male consumers, it is recommended to highlight security badges, encryption claims, and audit frequency using concise technical language. For female consumers, it is advisable to accompany guarantees with clear summaries and microscopy geared towards control and understanding.

Trust is strengthened when users perceive clear utility and credible social signals. Therefore, the utility of the purchase should be prioritised with quick searches and filters tailored to organic products (origin, certification, cultivation method, ingredients), as well as comparison tools and explainable recommendations that indicate why an item is suggested. Integrate structured social proof, such as reviews from verified buyers, community questions and answers, and lists of creators who select assortments by need (e.g., low-waste shopping, family-friendly basics). Place these modules at the top of category and product pages. For female consumers, emphasise community endorsements and AI-developed shortlists based on personal tastes and previous shopping preferences; for male consumers, emphasise efficiency-oriented designs by measuring interaction with user-generated content, saved items, and shared items.

Marketing communications must reflect socio-cognitive relationships. For female consumer segments, the credibility of the community (ambassadors, verified reviews, creator packages) and a narrative (storytelling) of transparency that shows what data is collected, why, and how controls work should be taken into account, emphasising traceability, eco-labels, and real customer experiences with organic products. For male consumers, provide secure payments with passkeys, fast shipping SLAs, and a performance framework with concise technical guarantees. For male consumers, simplicity and page loading speed are important (e.g., ‘Buy Now’ with a saved privacy preset).

From a broader sustainability perspective, gender-tailored trust and privacy strategies can contribute to increasing the adoption of organic products, which has been associated with lower pesticide use and reduced environmental impact. By making organic e-commerce platforms more trustworthy and inclusive for both males and females, companies not only improve conversion rates but also support wider sustainability goals related to responsible consumption and climate mitigation.

5.3. Conclusions

This study fills a gap in the literature by applying an extended SCT model to organic product e-commerce, taking into account privacy, social influence, perceived usefulness of websites and gender differences between males and females in the context of organic product e-commerce. The results obtained support the appropriateness of including measures that capture aspects of privacy, social influence, usefulness and trust, with the latter standing out as a determining factor in behavioural purchase intention.

In light of the results obtained, website managers and, in particular, suppliers of organic products should take the necessary steps to attract and retain consumers and encourage them to purchase organic products. To this end, privacy aspects could be strengthened by collecting only the necessary personal information, guaranteeing user anonymity on websites and providing greater transparency on how personal data is collected, stored and used.

It is important to take into account gender differences between males and females, reinforcing and facilitating technology accessibility for females and strengthening the role of males in issues related to privacy, trust and social influence. Staff training, inclusive marketing campaigns, personalised privacy policies and greater website accessibility can help increase trust and purchase intent.

This study is limited to a single country (Spain), which is characterised by strong enforcement of EU data protection regulations and a relatively high penetration of organic products. These institutional and cultural conditions may heighten consumers’ sensitivity to privacy concerns, perceived risk and perceived control in online organic purchases, so the strength of some privacy-trust-intention relationships identified here may not be directly generalisable to countries with more relaxed data protection regimes or lower familiarity with organic products. The sample also includes only online consumers, and, in terms of measurement, the analysis focuses on comparing structural relationships and examining gender differences. In addition, the study addresses organic product e-commerce in general, without distinguishing between specific suppliers or product subcategories.

As future lines of research, we recommend conducting cross-country comparisons (e.g., Spain versus other markets) to examine how cultural and regional norms regarding privacy, organic consumption and gender shape the privacy-trust-intention links, as well as expanding the multigroup analysis to other segmentation variables such as age or income level. We also suggest incorporating additional antecedents, such as the credibility of organic certifications and personal environmental values, and, to reinforce causal inference, combining longitudinal designs with field or A/B experiments.