Challenges and Responsibilities in Service-Based Sustainable Fashion Retail: Insights and Guidelines from a Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What components characterise service-based business models that support sustainability in the fashion retail sector?

- RQ2: What insights emerge from experts in the fashion retail sector regarding the challenges, opportunities, and responsibilities associated with adopting service-based sustainable models?

- RQ3: How can the findings from literature and expert consultation be integrated into a set of guidelines for sustainable, service-oriented fashion retail?

2. Literature Review

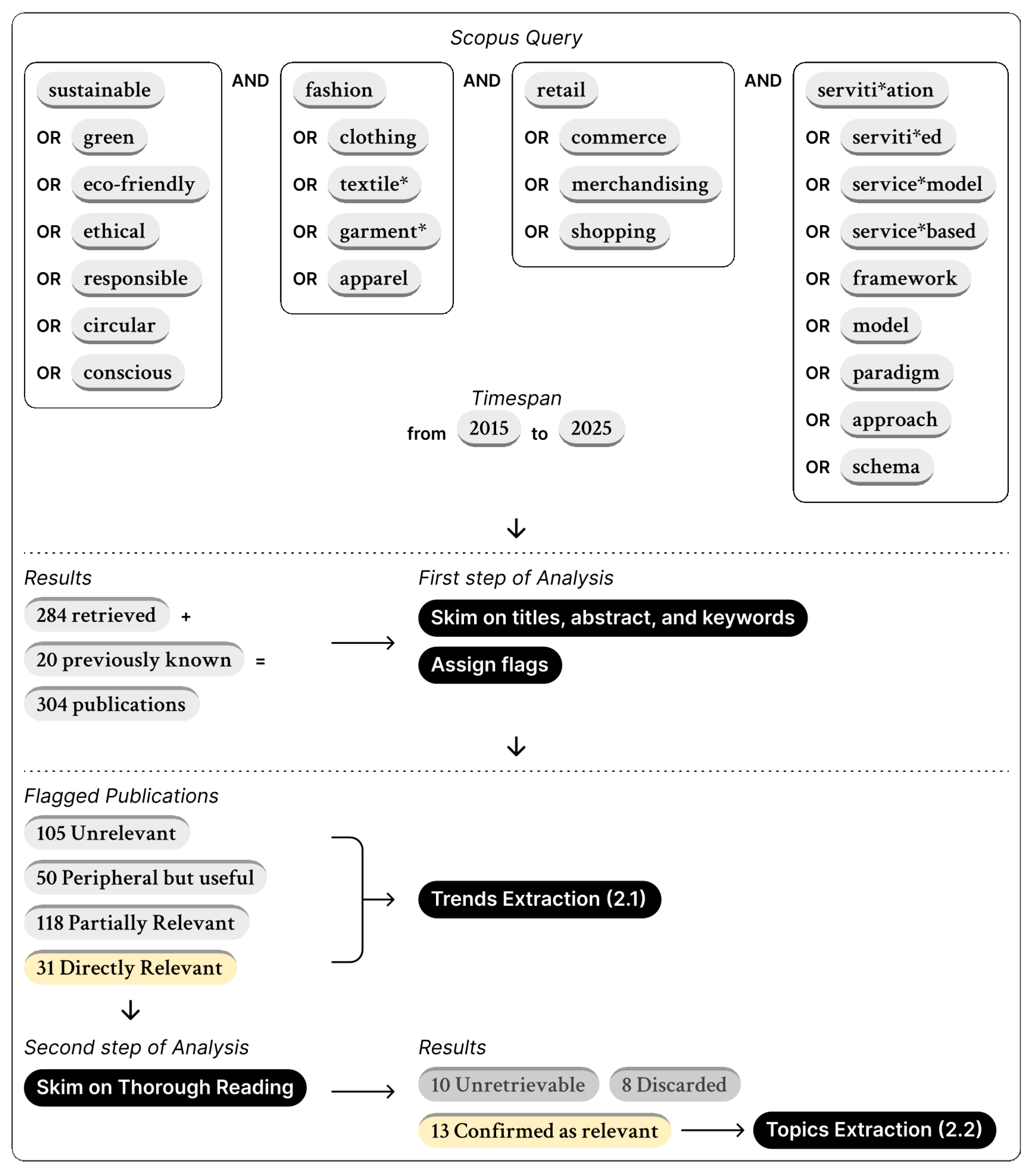

2.1. Trends in Service-Based Sustainable Fashion Retail

2.2. Components of Service-Based Business Models in Fashion Retail

| Title | Year | Methods | Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Engagement in Circular Consumption Systems: A Roadmap Structure for Apparel Retail Companies [26] | 2024 | Literature Review, semi-structured interviews, roadmap development based on the Grand Challenges framework [111] | 4, 7, 8 |

| Modeling the supply chain sustainability imperatives in the fashion retail industry: Implications for sustainable development [27] | 2024 | Literature review, expert feedback, Pareto analysis, and the Bayesian Best–Worst Method (BWM) | 1, 2, 4, 8 |

| Communicating sustainability to children through fashion retail third places [38] | 2025 | Literature review and focus group | 4 |

| Scaling circular business models: Strategic paths of second-hand fashion retail [108] | 2025 | Process-based study | 3, 4, 8 |

| Exploring Scalability from a Triple Bottom Line Perspective: Challenges and Strategic Resources for Fashion Resale [102] | 2023 | exploratory interviews | 2, 3, 5, 6 |

| Trade-offs in supply chain transparency: The case of Nudie Jeans Co [73] | 2015 | Single case in-depth analysis and managers interviews | 1, 4 |

| Green merchandising of textiles and apparel in a circular economy: Recent trends, framework, challenges and future prospects towards sustainability [40] | 2025 | Literature review | 1, 4 |

| Back to the future of fashion: Circularity and consumer ethics [107] | 2025 | Quantitative survey analysis | 2, 4, 5 |

| Advancing circular economy in the textile industry: A Comprehensive Study of Reverse Logistics and Operational Practices in Austria [89] | 2025 | Literature review and qualitative questionnaire-based expert interviews | 2, 3 |

| Adoption of Eco-Friendly Waste Reduction Practices in the Clothing Retail Sector in Cape Town [63] | 2024 | Purposive sampling and in-depth interviews | 1, 2, 3, 5 |

| Eco-Transcendence in Fashion Retail [106] | 2024 | Survey administered with convenient sampling and statistical analysis | 1, 2, 4, 7, 8 |

| The challenges to circular economy in the Indian apparel industry: A qualitative study [109] | 2025 | Literature review and DELPHI study | 4, 5, 8 |

| The role of human resource management (HRM) for the implementation of sustainable product-service systems (PSS)-An analysis of fashion retailers [101] | 2018 | Quantitative questionnaire and ANOVA analysis | 5 |

| Components and Description |

|---|

| C1—Long-term supply chain sustainability and transparency This component highlights the importance of certifications, audits, and verifiable sustainability standards that ensure compliance, reliability, and ethical practices. It also discusses the balance between transparency and collaboration, noting that full disclosure may conflict with cooperative supplier relationships. |

| C2—Adoption of digitisation and technological solutions Digital technologies such as AI, robotics, 3D sampling, and data management systems are key enablers of sustainability and efficiency. They improve supply chain transparency, reduce environmental impact, and enhance brand–consumer interactions in both physical and digital environments. |

| C3—Breadth-scaling This component explores how circular business models can be scaled through replication, standardisation, and strategic partnerships. It addresses operational challenges such as inventory management and the individual handling of garments, which complicate scalability in online and offline contexts. |

| C4—Depth-scaling Depth-scaling focuses on systemic cultural and institutional change to foster consumer understanding, trust, and responsible behaviour. It underscores the importance of educational experiences, storytelling, and value-driven communication to promote sustainability-oriented mindsets. |

| C5—Enhancement of human resources The success of service-based retail models relies on skilled, motivated employees and supportive labour conditions. Professional growth, fair wages, participatory decision-making, and cross-disciplinary expertise are critical for value co-creation with consumers and partners. |

| C6—Functional and experiential brick-and-mortar shops Physical stores act as operational hubs for circular practices and as experiential spaces that enhance customer engagement. Their design and functions support product take-back, education, and interaction, bridging logistics with immersive brand experiences. |

| C7—Communication strategies Effective sustainability communication requires coherence between corporate values, product offerings, and consumer expectations. Transparent and consistent messages help prevent greenwashing and reinforce consumer trust in retailers’ environmental and ethical commitments. |

| C8—Institutional support to sustainable business models Institutional and policy frameworks play a crucial role in facilitating the transition toward circular economy models. Financial incentives, regulatory support, and context-sensitive policies are essential to improve the viability and scalability of sustainable retail practices. |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants in the Focus Group

3.2. Discussion Guide

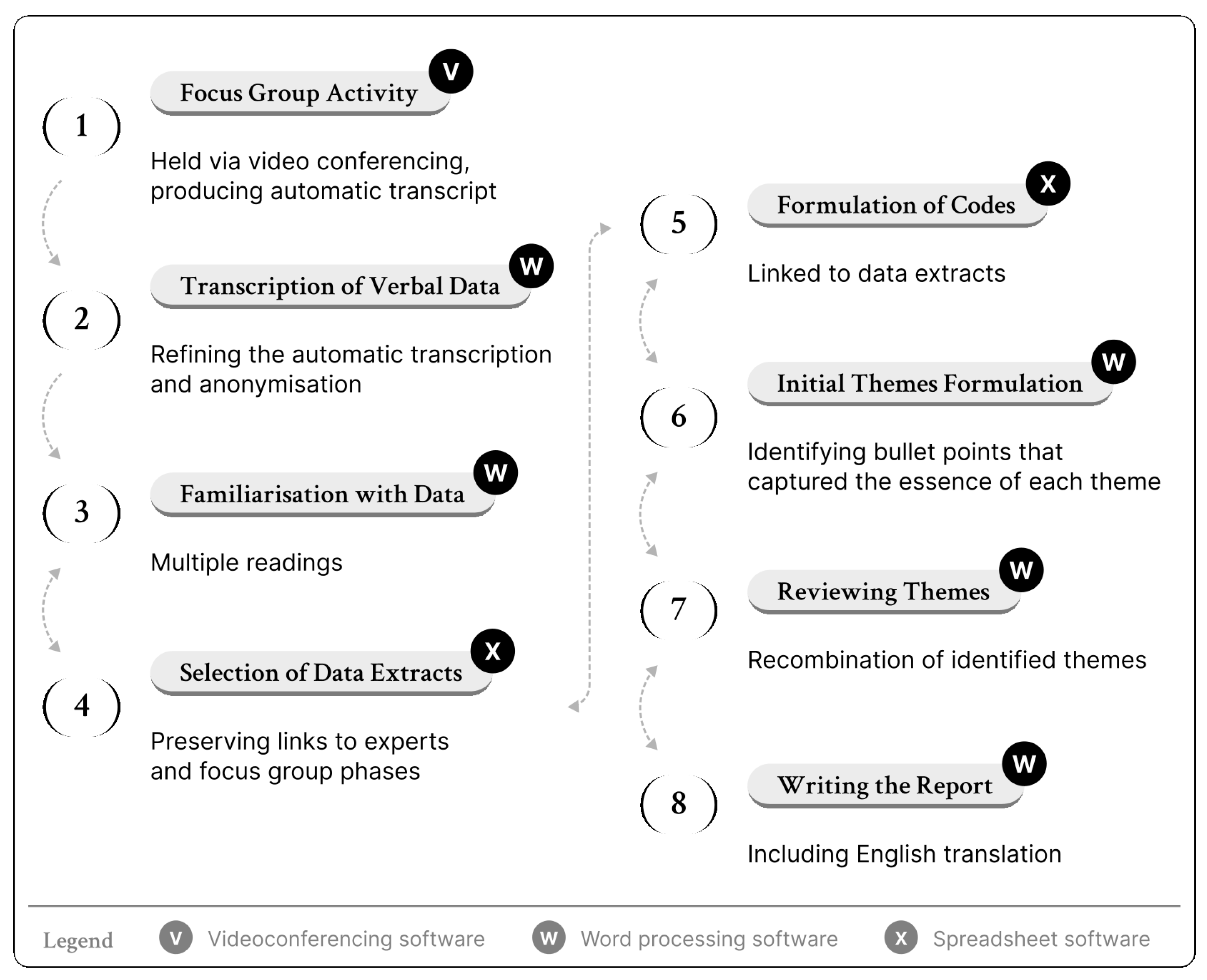

3.3. Conduction of the Activity and Analysis of Results

4. Results: Emerging Themes from the Focus Group Analysis

4.1. Retail as a Driver of Sustainability-Oriented Mindset

4.2. Retail as a Window over the Supply Chain

4.3. Servitised Retail in Support of a Sustainable Consumption

4.4. Sustainable Retail as an Experiential Space

4.5. Transparency and Traceability as Founding Values of Sustainable Retail

4.6. The Role of EU Policies in Sustainable Fashion

4.7. Opportunities for Improving the Mapping of Service-Based Fashion Retail

4.8. Stakeholders Interested in a Framework of Sustainable and Service-Based Retail

4.9. Other Opportunities: AI, Cross-Fertilisation, and Brand Accountability

4.10. Cross-Fertilisation from the Agriculture Sector

4.11. Brand Accountability

5. Discussion

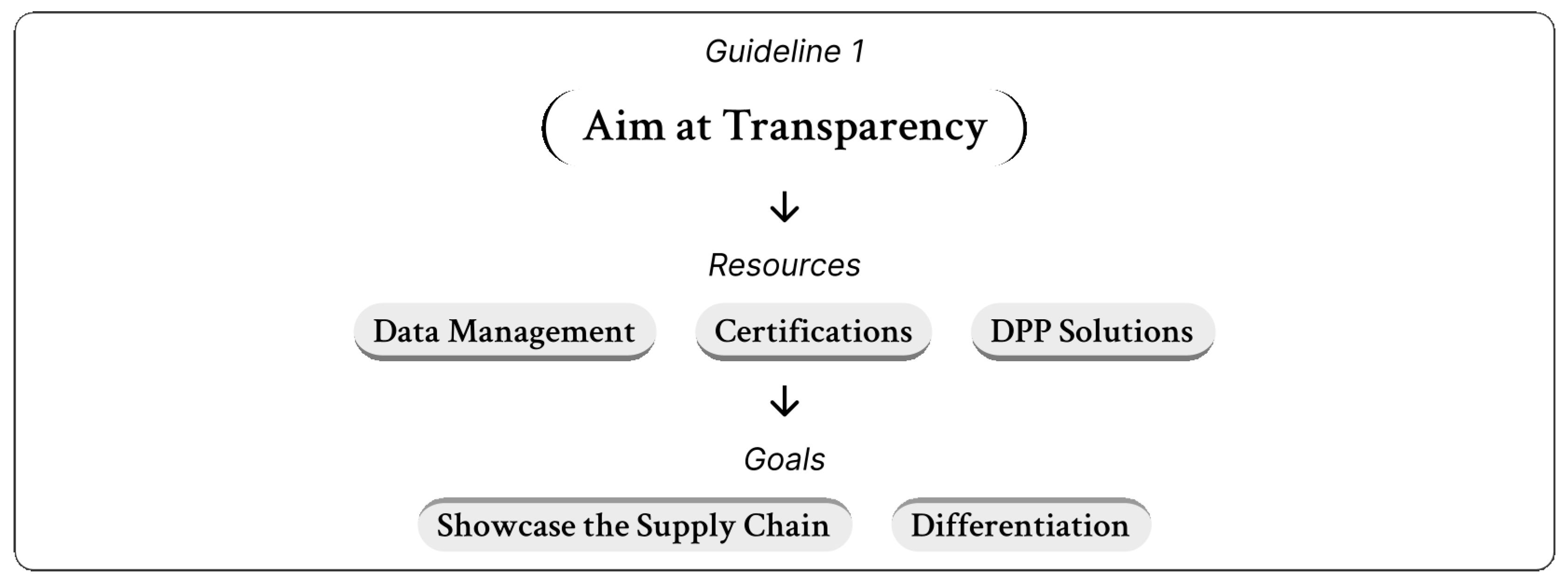

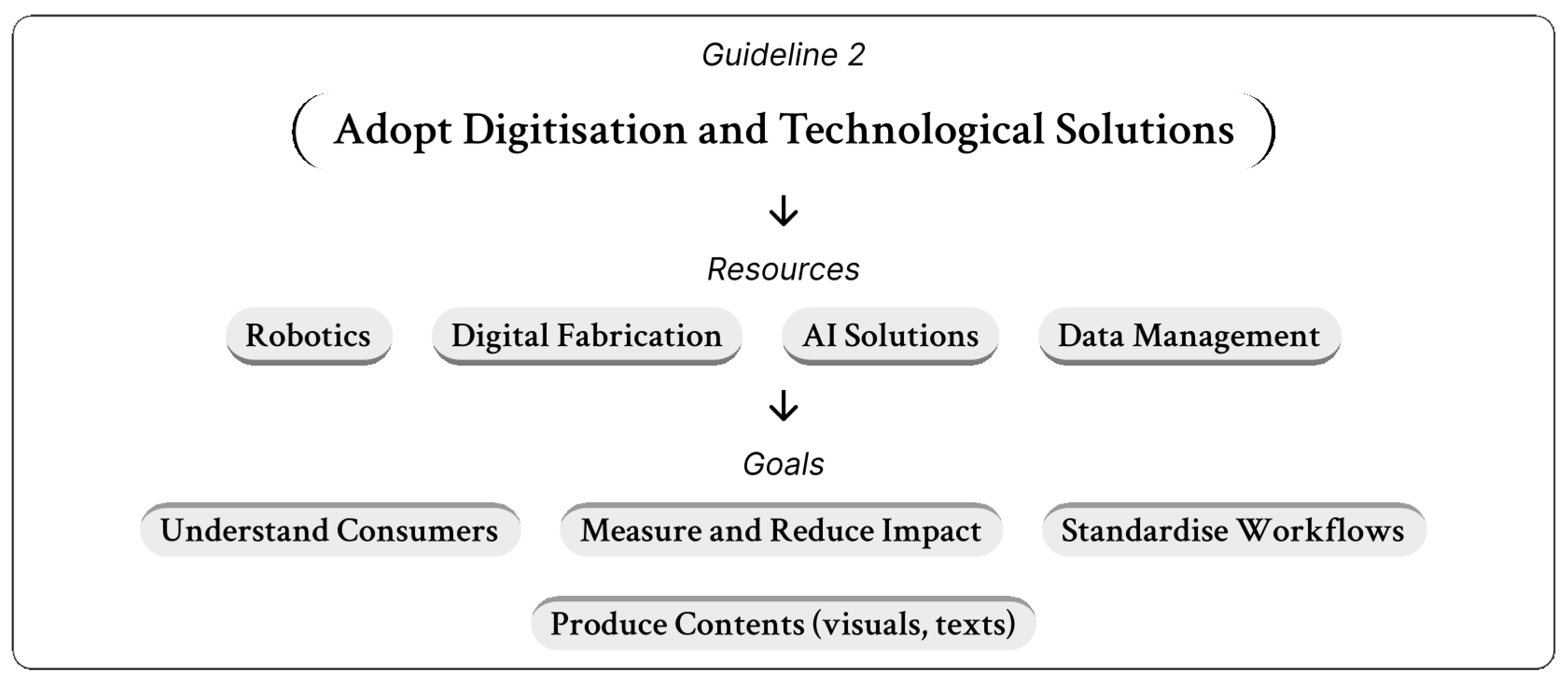

5.1. Guidelines for Service-Based Fashion Retail

5.1.1. Aim at Transparency

5.1.2. Adopt Digitisation and Technological Solutions

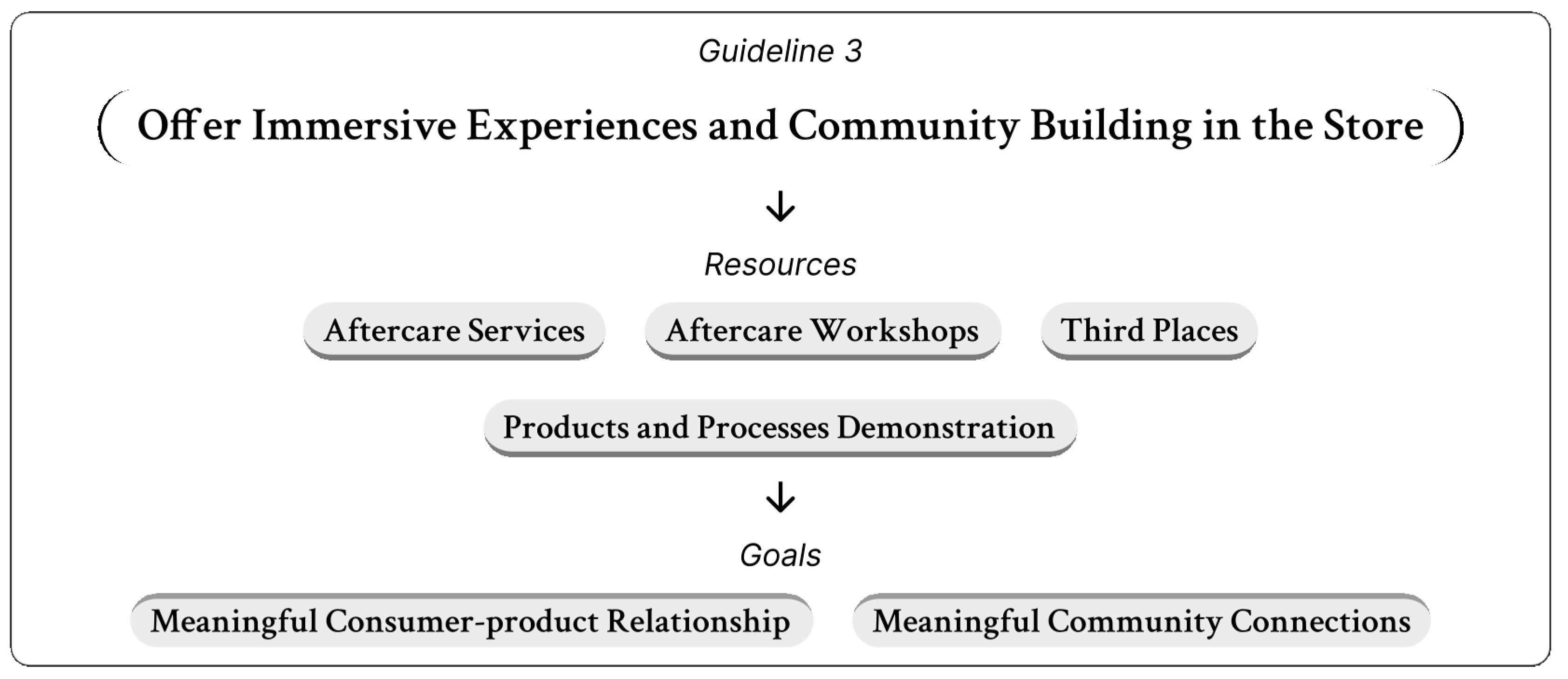

5.1.3. Offer Immersive Experiences and Community Building in the Store

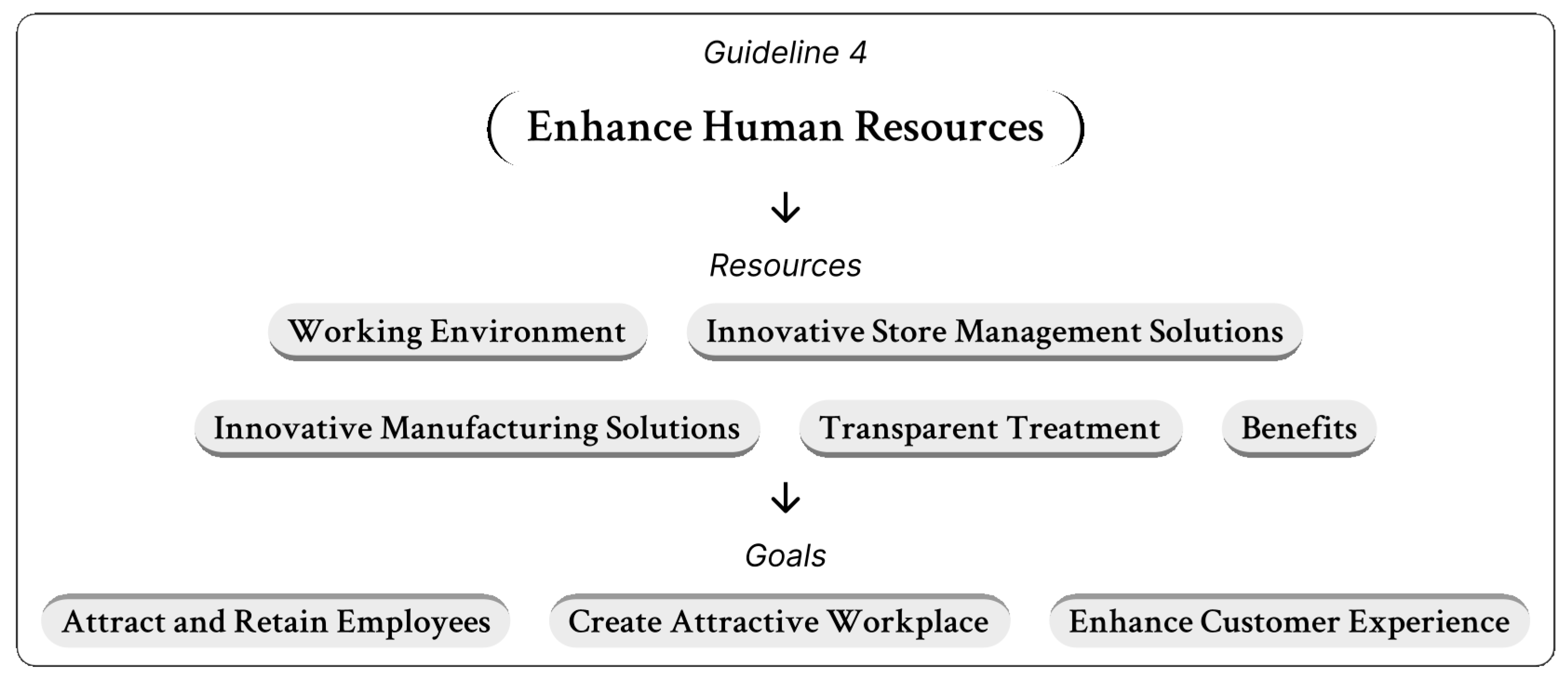

5.1.4. Enhance Human Resources

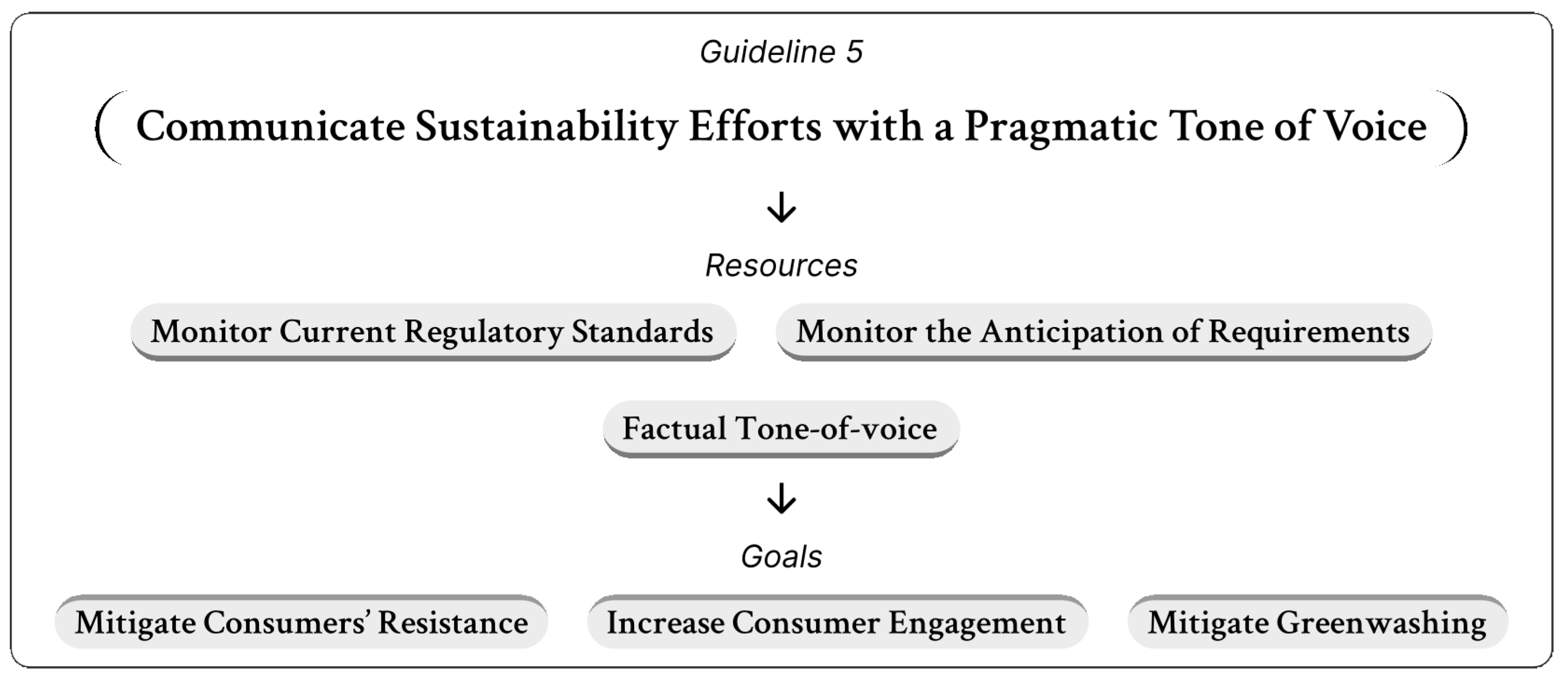

5.1.5. Communicate Sustainability Efforts with a Pragmatic Tone of Voice

5.2. Limitations and Further Works

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kronthal-Sacco, R.; Whelan, T. Sustainable Market Share Index; NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Bus Strat. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-1-900961-27-1. [Google Scholar]

- Giddings, B.; Hopwood, B.; O’Brien, G. Environment, Economy and Society: Fitting Them Together into Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Aguiar Hugo, A.; De Nadae, J.; Da Silva Lima, R. Can Fashion Be Circular? A Literature Review on Circular Economy Barriers, Drivers, and Practices in the Fashion Industry’s Productive Chain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Heshmati, A.; Rashidghalam, M. Circular Economy Business Models with a Focus on Servitization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultberg, E.; Pal, R. Lessons on Business Model Scalability for Circular Economy in the Fashion Retail Value Chain: Towards a Conceptual Model. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potting, J.; Hekkert, M.; Worrell, E.; Hanemaaijer, A. Circular Economy: Measuring Innovation in the Product Chain; PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, A.A.; Remmen, A. (Eds.) Background Report for a UNEP Guide to LIFE CYCLE MANAGEMENT: A Bridge to Sustainable Products; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vezzoli, C.; Conti, G.M.; Macrì, L.; Motta, M. Designing Sustainable Clothing Systems The Design for Environmentally Sustainable Textile Clothes and Its Product-Service Systems; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-88-351-4011-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A. Eight Types of Product–Service System: Eight Ways to Sustainability? Experiences from SusProNet. Bus Strat. Environ. 2004, 13, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, E. Collaborative Consumption in the Fashion Industry: A Systematic Literature Review and Conceptual Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 325, 129261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, G.F.; Spagnoli, A. Collaborative Fashion Consumption: Second-Hand PSSs as Agent of Change. In Proceedings of the Entanglements and Flows Service Encounters and Meanings, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 28 November 2023; pp. 458–477. [Google Scholar]

- Iran, S.; Schrader, U. Collaborative Fashion Consumption and Its Environmental Effects. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. (JFMM) 2017, 21, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Goworek, H.; Ryding, D. (Eds.) Sustainability in Fashion: A Cradle to Upcycle Approach; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-51252-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, T.; Peck, D.; Geldermans, B.; Van Timmeren, A. The Role of Urban Manufacturing for a Circular Economy in Cities. Sustainability 2020, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermerwe, S.; Rada, J. Servitization of Business: Adding Value by Adding Services. Eur. Manag. J. 1988, 6, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanatlı, M.A.; Karaer, Ö. Servitization as an Alternative Business Model and Its Implications on Product Durability, Profitability & Environmental Impact. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 301, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, P.; Tosun, G. The Impact of Servitization on Perceived Quality, Purchase Intentions and Recommendation Intentions in the Ready-to-Wear Sector. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. (JFMM) 2023, 28, 460–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuren, F.H.; Gomes Ferreira, M.G.; Cauchick Miguel, P.A. Product-Service Systems: A Literature Review on Integrated Products and Services. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.; Plepys, A. Product-Service Systems and Sustainability: Analysing the Environmental Impacts of Rental Clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana. Principi CNMI per la Sostenibilità del Retail; Goldmann & Partners: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ricchiardi, A.; Bugnotto, G. Customized Servitization as an Innovative Approach for Renting Service in the Fashion Industry. CERN IdeaSquare J. Exp. Innov. 2019, 3, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defee, C.C.; Randall, W.S.; Gibson, B.J. Roles and Capabilities of the Retail Supply Chain Organization. J. Transp. Manag. (JOTM) 2009, 21, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.M.; Moreira, N.; Ometto, A.R. Consumer Engagement in Circular Consumption Systems: A Roadmap Structure for Apparel Retail Companies. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2024, 4, 1405–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.d.T.I.; Karmaker, C.L.; Karim, R.; Misbauddin, S.M.; Bari, A.B.M.M.; Raihan, A. Modeling the Supply Chain Sustainability Imperatives in the Fashion Retail Industry: Implications for Sustainable Development. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos Rudolph, L.T.; Bassi Suter, M.; Barakat, S.R. The Emergence of a New Business Approach in the Fashion and Apparel Industry: The Ethical Retailer. J. Macromarketing 2023, 43, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overdiek, A. Opportunities for Slow Fashion Retail in Temporary Stores. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. (JFMM) 2018, 22, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheny, R.L. Building a Case for Slow Retail Design. In Proceedings of the Designing Retail and Services Futures 2023: Reimagining the Future for Retail and Service Design Theory and Practices, London, UK, 30 March 2023; Design Research Society: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, B.; Varley, R. Retail Futures: Customer Experience, Phygital Retailing, and the Experiential Retail Territories Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, S.; Palakshappa, N.; Stangl, L.M. Sustainability in Retail Services: A Transformative Service Research (TSR) Perspective. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2022, 32, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda, L. Overcoming Barriers for Sustainable Fashion: Bridging Attitude-Behaviour Gap in Retail. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. (IJRDM) 2024, 52, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brito, M.P.; Carbone, V.; Blanquart, C.M. Towards a Sustainable Fashion Retail Supply Chain in Europe: Organisation and Performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 114, 534–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elli, T.; Spagnoli, A.; Iannilli, V.M. Mapping Service-Based Retailing to Improve Sustainability Practices in the Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; De Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Van Der Grinten, B. Product Design and Business Model Strategies for a Circular Economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, B. Commercial, Social and Experiential Convergence: Fashion’s Third Places. J. Serv. Mark. (JSM) 2019, 33, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elízaga, R.; Alexander, B.; Sádaba, T. Communicating Sustainability to Children through Fashion Retail Third Places. Manag. Decis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You through the Day, 1st ed.; Paragon House: New York, NY, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-1-55778-110-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman, M.T.; Khan, M.S.H. Green Merchandising of Textiles and Apparel in a Circular Economy: Recent Trends, Framework, Challenges and Future Prospects towards Sustainability. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, J.; Parker, L.; McQuilten, G.; Bigolin, R. Fashionable Altruism: The Marketing of Fashion-Based Social Enterprise. Soc. Enterp. J. 2025, 21, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, W.; Yin, Y. Optimal Strategies for a Multi-Channel Recycling Supply Chain in the Clothing Industry: Considering Consumer Types. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. (IJCST) 2023, 35, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Sadhukhan, J.; Druckman, A.; James, K. A Comparison of Circular Business Models Using Life Cycle Assessment, Focusing on Clothing Retail, Distribution and Use. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, F.; Rahm, I.; Fuentes, C. Digital Platforms for Circular Shopping: Slowing down and Speeding up Second-Hand Clothing Consumption. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, F.; Hofmann Trevisan, A.; Vitti, M.; Caldarelli, P.; Dukovska-Popovska, I.; Downes, S.; Taisch, M.; Terzi, S.; Sassanelli, C. Market Needs for a Circular Transition: Implemented Practices and Required Skills. In Advances in Production Management Systems. Production Management Systems for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous Environments; Thürer, M., Riedel, R., Von Cieminski, G., Romero, D., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 728, pp. 262–274. ISBN 978-3-031-71621-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, R.; Jayarathne, A. Digitalization in the Textiles and Clothing Sector. In The Digital Supply Chain; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 255–271. ISBN 978-0-323-91614-1. [Google Scholar]

- Toșa, C.; Paneru, C.P.; Joudavi, A.; Tarigan, A.K.M. Digital Transformation, Incentives, and pro-Environmental Behaviour: Assessing the Uptake of Sustainability in Companies’ Transition towards Circular Economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 47, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M. Virtual Influencers in Niche Markets: Unlocking Opportunities for Targeted Marketing. In Practical Frameworks for New-Age Digitalization Business Strategy; Tee, P.K., Song, B.L., Ho, R.C., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 273–306. ISBN 979-8-3373-2018-2. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, S.; Jiang, Z.; Lyu, J. Sustainable Style without Stigma: Can Norms and Social Reassurance Influence Secondhand Fashion Recommendation Behavior among Gen Z? J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2024, 15, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.M.; Nguyen, T. Eco or Ego? Promoting Second-Hand Luxury Consumption Using Message Appeals. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2025, 53, 889–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C. Green & Sustainable Luxury: A Strategic Evidence. In Thriving in a New World Economy; Plangger, K., Ed.; Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; p. 270. ISBN 978-3-319-24146-3. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, L. Exploring Young Consumers’ Perceptions towards Sustainable Practices of Fashion Brands. Fash. Style Pop. Cult. 2024, 11, 527–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Yang, Z. Empirical Analysis on Intra-Industry Trade in Textile between China and Vietnam. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1423, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran, S.; Martinez, C.J.; Walsleben, L.S. Unraveling the Closet: Exploring Reflective Decluttering and Its Implications for Long-Term Sufficient Clothing Consumption. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2024, 15, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Lan, L.; Watkins, J. Pre-Owned Fashion as Sustainable Consumerism? Opportunities and Challenges in the Vietnam Market. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. (JFMM) 2023, 27, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Akbari, M.; Maleki Far, S. Recent Sustainable Trends in Vietnam’s Fashion Supply Chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, S.; Niguse, T.; Olubiyi, T.O.; Adula, M.; Kebede, K. Sustainable Fashion-Based Innovations and Consumer Behavior in Ethiopia. In Advances in Business Strategy and Competitive Advantage; Olubiyi, T.O., Behera, S.K., Tran, T.A., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 167–196. ISBN 979-8-3693-7853-3. [Google Scholar]

- Khurana, K.; Tadesse, R. A Study on Relevance of Second Hand Clothing Retailing in Ethiopia. Res. J. Text. Appar. (RJTA) 2019, 23, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadlapalli, A.; Rahman, S.; Rogers, H. A Dyadic Perspective of Socially Responsible Mechanisms for Retailer-Manufacturer Relationship in an Apparel Industry. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. (IJPDLM) 2019, 49, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebal, M.A.; Jackson, F.H. Cues for Shaping Purchase of Local Retail Apparel Clothing Brands in an Emerging Economy. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. (IJRDM) 2019, 47, 1013–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geegamage, T.; Ranaweera, A.; Halwatura, R. Pre-Loved or Hatred? Consumers’ Perception of Value towards Second-Hand Fashion Consumption in Sri Lanka. Res. J. Text. Appar. (RJTA) 2024, 28, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumarana, T.T.; Karunathilake, H.P.; Punchihewa, H.K.G.; Manthilake, M.M.I.D.; Hewage, K.N. Life Cycle Environmental Impacts of the Apparel Industry in Sri Lanka: Analysis of the Energy Sources. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1346–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S.; Patnaik, A. Adoption of Eco-Friendly Waste Reduction Practices in the Clothing Retail Sector in Cape Town. Text Leather Rev. 2024, 7, 1360–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muposhi, A.; Chuchu, T. Influencing Millennials to Embrace Sustainable Fashion in an Emerging Market: A Modified Brand Avoidance Model Perspective. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. (JFMM) 2024, 28, 738–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S.; Isaacs, S. Using Entrepreneurship to Address Economic Challenges. In Europe in the New World Economy: Opportunities and Challenges; Chivu, L., Ioan-Franc, V., Georgescu, G., De Los Ríos Carmenado, I., Andrei, J.V., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 405–414. ISBN 978-3-031-71328-6. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, A.; Ramachandaran, S.D. Online Apparel Purchase and Responsible Consumption Among Malaysians. TEM J. 2023, 12, 2378–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramany, R.; Chan, T.-J.; Mohan, Y.M.; Lau, T.-C. Purchasing Behaviour of Sustainable Apparels Using Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Predictive Approach. Malays. J. Consum. Fam. Econ. 2022, 29, 179–215. [Google Scholar]

- Beuria, R.K.; Kondasani, R.K.R.; Mahato, J. Unraveling the Impact of Minimalism on Green Purchase Intention: Insights from Theory of Planned Behavior. Res. J. Text. Appar. (RJTA) 2024, 29, 1038–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Pandey, M.; Kakkar, A. A Review of Consumer Perspectives on Green Apparel. In Emerging Trends in Traditional and Technical Textiles; Midha, V.K., Fangueiro, R., Rajendran, S., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Materials; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; Volume 55, pp. 185–193. ISBN 978-981-97-5901-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran, P. Barriers to Sustainable Transition in the Fashion Industry: Insights from India. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2025, 21, 2466286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srividya, N.; Atiq, R.; Volety, N.S. Qualitative Research on Responsible Consumption Concerning Apparel. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2024, 12, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Giri, A.; Alzeiby, E.A. Analyzing the Motivators and Barriers Associated with Buying Green Apparel: Digging Deep into Retail Consumers’ Behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egels-Zandén, N.; Hulthén, K.; Wulff, G. Trade-Offs in Supply Chain Transparency: The Case of Nudie Jeans Co. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eruguz, A.S.; Karabağ, O.; Tetteroo, E.; Van Heijst, C.; Van Den Heuvel, W.; Dekker, R. Customer-to-Customer Returns Logistics: Can It Mitigate the Negative Impact of Online Returns? Omega 2024, 128, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, E. Orchestration Capabilities in Circular Supply Chains of Post-Consumer Used Clothes—A Case Study of a Swedish Fashion Retailer. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiaroli, V.; Alvino, L.; Verdonk, E.; Dangelico, R.M.; Fraccascia, L. Sustainability across Borders: Which Factors Influence Sustainable Footwear Choices? An Empirical Study on Italian and Dutch Consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 521, 146133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacheo, A.; Caratù, M.; Mainolfi, G. The Paths of Heritage Luxury Brands in the Digital Age: Italian Case Studies from the Fashion Industry. Micro Macro Mark. 2025, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Liu, J. Hidden Footprints in Reverse Logistics: The Environmental Impact of Apparel Returns and Carbon Emission Assessment. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Albuquerque Landi, F.F.; Fabiani, C.; Pioppi, B.; Pisello, A.L. Sustainable Management in the Slow Fashion Industry: Carbon Footprint of an Italian Brand. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess 2023, 28, 1229–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, R.; Zhang, D.; Parry, G.; Wood, S.; Merlano, E.F. Scoping Innovative Retail Product Returns Pathways. Strategy Leadersh. 2025, 53, 658–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magano, J.; Turčinkova, J.; Santos, M.C.; Correia, R.; Serebriannikov, M. Exploring Apparel E-Commerce Unethical Return Experience: A Cross-Country Study. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2650–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederlaender, M.; Liebau, U.; Chen, Y.; Breustedt, E.; Driouech, S.; Werth, D. Strategic Returns Prevention in E-Commerce: Simulating Financial and Environmental Outcomes Through Agent-Based Modeling. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence, Porto, Portugal, 23–25 February 2025; SCITEPRESS-Science and Technology Publications: Setúbal, Portugal, 2025; pp. 453–462. [Google Scholar]

- Gry, S.; Niederlaender, M.; Lodi, A.N.; Mutz, M.; Werth, D. A Conceptual Approach for an AI-Based Recommendation System for Handling Returns in Fashion E-Commerce. In Smart Business Technologies; Van Sinderen, M., Hammoudi, S., Wijnhoven, F., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 2132, pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-3-031-67903-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sneha, K.; Badrinath, P. FITS: Fashion Innovation Through Synthesis. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Emerging Technologies in Computing and Communication (ETCC), Bangalore, India, 26 June 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Niederlaender, M.; Driouech, S.; Gry, S.; Lodi, A.N.; Biswas, R.; Werth, D. Towards Waste Reduction in E-Commerce: A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms and Optimisation Techniques for Garment Returns Prediction with Feature Importance Evaluation. SN Comput. Sci. 2025, 6, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.; Fan, Z.; Chi, C.; Wan, Y. An LSTM-Based System for Accurate Breast Shape Identification and Personalized Bra Recommendations for Young Women. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2025, 107, 103736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Rajasekaran, A.; Sathawane, N.; Nandal, N.; Wagh, M.N.; Jadhav, M. Machine Learning Effects on Consumer Decision-Making and Purchase Behavior in the Fashion Industry of India. In Proceedings of the 2024 Ninth International Conference on Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (ICONSTEM), Chennai, India, 4 April 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, L.; Spinler, S. From Returns to Re-Usage: A Data-Driven Strategy for Sustainable Packaging—A Case Study in e-Commerce. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 510, 145584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandner, M.; Pfoser, S.; Voraberger, E.; Brandtner, P.; Schauer, O. Advancing Circular Economy in the Textile Industry: A Comprehensive Study of Reverse Logistics and Operational Practices in Austria. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 263, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.-J.; Choi, T.-M.; Zhang, T. Commercial Used Apparel Collection Operations in Retail Supply Chains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 298, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabro Cardoso, G. Community-Driven Consumption Dynamics: An Analysis of How Consumer Participation in Fashion Retailing Can Strength Sustainability. Fash. Highlight 2024, 3, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mu, X.; Li, G.; Xu, Z.; Yu, X.; Ma, J. Mannequin2Real: A Two-Stage Generation Framework for Transforming Mannequin Images Into Photorealistic Model Images for Clothing Display. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 2773–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeganathan, K.; Szymkowiak, A. Bridging Digital Product Passports and In-Store Experiences: How Augmented Reality Enhances Decision Comfort and Reuse Intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, M.; Deng, Q.; Hribernik, K.A.; Thoben, K.-D.; Ciaccio, G. Towards a Service Marketplace to Empower Circular Economy Transition: An Example Application in the Supply Chain of Textile Industry. In Advances in Production Management Systems. Production Management Systems for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous Environments; Thürer, M., Riedel, R., Von Cieminski, G., Romero, D., Eds.; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 728, pp. 235–249. ISBN 978-3-031-71621-8. [Google Scholar]

- Donmezer, S.; Demircioglu, P.; Bogrekci, I.; Bas, G.; Durakbasa, M.N. Revolutionizing the Garment Industry 5.0: Embracing Closed-Loop Design, E-Libraries, and Digital Twins. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, G.; Kamble, S.S.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Shrivastava, A.; Belhadi, A.; Venkatesh, M. Antecedents of Blockchain-Enabled E-Commerce Platforms (BEEP) Adoption by Customers–A Study of Second-Hand Small and Medium Apparel Retailers. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Soomro, M.A.; Zahid Piprani, A.; Yu, Z.; Tanveer, M. Sustainable Supply Chain Practices and Blockchain Technology in Garment Industry: An Empirical Study on Sustainability Aspect. J. Strategy Manag. (JSM) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Breslin, J.G. Peer to Peer Energy Trade Among Microgrids Using Blockchain Based Distributed Coalition Formation Method. Technol. Econ. Smart Grids Sustain. Energy 2018, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, S.; Fidelis, A.C. Digital Approach to Slow Fashion: Mapping Second-Hand Stores in Porto. Fash. Highlight 2025, SI1, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, O. Twirl Store: Pioneering Sustainable Textile Practices by Closing the Loop. Emerald Emerg. Mark. Case Stud. (EEMCS) 2024, 14, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M. The Role of Human Resource Management (HRM) for the Implementation of Sustainable Product-Service Systems (PSS)—An Analysis of Fashion Retailers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultberg, E.; Pal, R. Exploring Scalability from a Triple Bottom Line Perspective: Challenges and Strategic Resources for Fashion Resale. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2023, 3, 2201–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.J.; Mohd Suki, N.; Ho, P.S.Y.; Akhtar, M.F. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on Consumer Purchase Intention of Apparel Products with Mediating Role of Consumer-Retailer Love. Soc. Responsib. J. 2024, 20, 998–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P. Researching the Vulnerable: A Guide to Sensitive Research Methods; SAGE: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4129-1253-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic, D.; Tanner, J. Vulnerable People, Groups, And Populations: Societal View. Health Aff. 2007, 26, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwal, A.; Sarkar, M.; Gautam, R.S.; Rastogi, S.; Sharma, S. Eco-Transcendence in Fashion Retail. In Proceedings of the 2024 Second International Conference on Advances in Information Technology (ICAIT), Chikkamagaluru, India, 24 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Novo-Corti, I.; Membiela-Pollan, M.; Tirca, D.M. Back to the Future of Fashion: Circularity and Consumer Ethics. E+M 2025, 28, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultberg, E. Scaling Circular Business Models: Strategic Paths of Second-Hand Fashion Retail. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. (JFMM) 2025, 29, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A.A.; Chandra, R. The Challenges to Circular Economy in the Indian Apparel Industry: A Qualitative Study. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2025, 29, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D. The Role of Markup in the Digital Humanities. Hist. Soc. Res. 2016, 37, 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; Howard-Grenville, J.; Joshi, A.; Tihanyi, L. Understanding and Tackling Societal Grand Challenges through Management Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1880–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acocella, I. Il Focus Group: Teoria e Tecnica, 2nd ed.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2015; ISBN 978-88-464-9257-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cannavò, L.; Frudà, L. Ricerca Sociale, 1st ed.; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2007; ISBN 978-88-430-3944-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zammuner, V.L. I Focus Group; Aggiornamenti Aspetti della Psicologia; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2003; ISBN 978-88-15-08494-1. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. The Sustainable Fashion Communication Playbook Shifting the Narrative: A Guide to Aligning Fashion Communication to the 1.5-Degree Climate Target and Wider Sustainability Goals; UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme): Nairobi, Kenya, 2023; ISBN 978-92-807-4048-6. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, B. Why the Way Fashion Talks about Sustainability Needs to Change. Vogue Business, 27 June 2023. Available online: https://www.vogue.com/article/why-the-way-fashion-talks-about-sustainability-needs-to-change-united-nations-sustainable-fashion-communication (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Pangarkar, A.; Arora, V.; Shukla, Y. Exploring Phygital Omnichannel Luxury Retailing for Immersive Customer Experience: The Role of Rapport and Social Engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Kannan, P.K.; Inman, J.J. From Multi-Channel Retailing to Omni-Channel Retailing. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, T.L. Moderating Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Group Facilitation; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7619-2043-4. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Profiles | Participants |

|---|---|

| Profile A: Manager from the fashion industry The profile describes professionals with a managing and strategic role in the fashion industry to bring into the discussion the perspectives of someone concerned with a company’s organisational and economic matters (i.e., managing directors, heads of buying, marketing directors, and CEOs). Two participants with contrasting backgrounds were selected: one from a sustainability-focused company, the other from the fast fashion sector. | Participant 1 Formerly an industrial designer, P1 works for an Italian fabric producer operating under strict environmental regulations. The company promotes its low-impact production as a value-added feature and recently entered the B2C market with an on-demand store model. |

| Participant 2 P2 is a professional in the fashion and luxury sectors and currently works for a multinational brand in the fast-fashion category. P2 has two decades of experience in the fashion field, particularly in management, retail buying, and e-commerce. | |

| Profile B: Social Entrepreneur in the Fashion System This profile includes professionals working in fashion-based social enterprises [41], supporting vulnerable groups [104,105] through labour inclusion and initiatives aligned with distributive justice [28]. Their activities include garment collection, sorting, upcycling, and social tailoring. | Participant 3 With a background in environmental engineering, P3 is an expert in circular economy and social cooperation. P3 chairs a long-standing SE in northern Italy that creates employment for vulnerable individuals by managing the reuse and resale of second-hand garments. |

| Profile C: Sustainable Fashion Communication Expert This profile includes professionals who raise public awareness of sustainable fashion by reporting on trends, technologies, policies, and events, and advocating for improved industry practices. Fashion communication often resonates with linear consumption models, but it can be a key factor in supporting the transition towards sustainability [115,116]. | Participant 4 P4 is a journalist with experience at a major women’s fashion magazine and later specialised in corporate sustainability communication. P4 is part of a collective that uses fine arts, including exhibitions and performances in retail spaces, to promote sustainable fashion. |

| Profile D: Retail Technologist This profile includes professionals who implement technological solutions in retail, focusing on phygital and omnichannel strategies to enhance customer experience and operational efficiency [117,118]. | Participant 5 With a background in industrial engineering, P5 has a decade of experience in digitalisation projects. P5 specialises in omnichannel strategies that connect consumers and brands through both digital and physical touchpoints, working in a company that develops scalable retail solutions. |

| Profile E: Sustainability Consultant The profile describes experts in techniques, regulations, methodologies and opportunities in activating sustainable transitions. They guide brands and manufacturers towards environmentally and socially responsible practices. | Participant 6 P6 has two decades of experience in the fashion industry as a slow fashion designer and a visual merchandising instructor. As an independent figure, P6 disseminates slow fashion concepts through various news outlets and co-founded a network that offers consultancy to startups and micro-enterprises focused on circular and socially responsible innovation. |

| Focus Group Phases | Focus Group Questions |

|---|---|

| Phase 1: Introduction Participants were informed that the session aimed to inquire the area of service-based fashion retail and its links to sustainability, with the goal of formulating insights to support businesses and designers in innovating the retail industry. The discussion was moderated to encourage diverse viewpoints without requiring consensus. Before starting, the moderator confirmed that while some participants had briefly met at public events (P1 with P3; P4 with P6), no close personal or hierarchical relationships were present, suggesting that focus group participants felt no interference in expressing their opinions. | No questions |

| Phase 2: Exploration This phase aims to explore perspectives around the theme of sustainable retail, asking participants broad questions to collect general opinions and experiences. | Q2.1 When you think of sustainable retail, what comes to mind? Q2.2 When you think of the servitisation of retail, what comes to mind? Q2.3 When you think of the pairing of servitisation and sustainability, what comes to mind? |

| Phase 3: Intensive Discussion This phase presents and discusses the mapping of service-based retail described in the introduction to foster experts’ reflections on the sector, evaluate the appropriateness of the mapping, and collecting suggestions for its improvement and deployment. The moderator used slides first to introduce the fundamental aspects of the framework (i.e., how it is created and its three main areas of services). Then slides are used to unpack the components of every area, using a storytelling approach based on incremental reveals to present content piece by piece, thereby preventing the audience from being overwhelmed. When needed, examples of services are provided to help participants understand the types of initiatives that have been mapped. Questions are asked after the presentation. | Q3.1 What do you think of the proposed service categorisation and the identified sub-groups? Which aspects would you modify, and how? Q3.2 Based on your professional expertise in the fashion industry, how frequently are the three previously described areas described together? Q3.3 Which types of retail can benefit from implementing one or more of these services? Q3.4 How do you think this mapping can be shared with retailers to encourage the implementation of one or more services? Q3.5 What opportunities and risks might be associated with implementing the presented services? |

| Phase 4: Conclusion The last phase aims to gather conclusive remarks by offering participants the opportunity to recall essential concepts or highlight any topics not addressed in the discussion. | Q4.1 Among the topics discussed, which do you consider the most relevant? And which aspects might have been overlooked? |

| Theme |

|---|

| 4.1 Retail as a Driver of Sustainability-Oriented Mindset |

| 4.2 Retail as a Window over the Supply Chain |

| 4.3 Servitised Retail in Support of a Sustainable Consumption |

| 4.4 Sustainable retail as an Experiential Space |

| 4.5 Transparency and Traceability as Founding Values of Sustainable Retail |

| 4.6 The Role of EU Policies in Sustainable Fashion |

| 4.7 Opportunities for Improving the Mapping of Service-based Fashion Retail |

| 4.8 Stakeholders Interested in a Framework of Sustainable and Service-based Retail |

| 4.9 Other opportunities: AI, cross-fertilisation, and brand accountability |

| 4.10 Cross-fertilisation from the Agriculture Sector |

| 4.11 Brand Accountability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elli, T. Challenges and Responsibilities in Service-Based Sustainable Fashion Retail: Insights and Guidelines from a Qualitative Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310474

Elli T. Challenges and Responsibilities in Service-Based Sustainable Fashion Retail: Insights and Guidelines from a Qualitative Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310474

Chicago/Turabian StyleElli, Tommaso. 2025. "Challenges and Responsibilities in Service-Based Sustainable Fashion Retail: Insights and Guidelines from a Qualitative Study" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310474

APA StyleElli, T. (2025). Challenges and Responsibilities in Service-Based Sustainable Fashion Retail: Insights and Guidelines from a Qualitative Study. Sustainability, 17(23), 10474. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310474