1. Introduction

This article examines how inclusive innovation can sustainably strengthen the prickly pear value chain in the municipality of Sonsón, Antioquia. The guiding research question is clear: under what conditions can an inclusive innovation approach enhance the economic, social, environmental, and cultural performance of a local agri-food chain without eroding its traditional knowledge and territorial ties? This issue is particularly relevant to Latin America, where agri-food systems based on native species simultaneously face market pressures, climate risks, and technological lag, but also present opportunities for differentiation through quality, traceability, and health-related attributes [

1]. In this context, prickly pear cultivation emerges as a crop with valorization potential due to its nutritional and nutraceutical uses. However, it faces postharvest and logistical constraints that limit its competitiveness in extended value chains unless supported by appropriate institutional arrangements and local capabilities [

1].

In Sonsón, recent assessments report productive fragmentation, limited processing capacity, weak interinstitutional coordination, and dependence on intermediaries, all of which affect quality, standardization, and value distribution [

2]. These characteristics are commonly associated with oligopsonistic market structures, which reduce the bargaining power of small-scale producers and hinder the capture of value at the origin [

3]. Furthermore, the literature on value chain governance shows that the definition of standards, pricing, and access requirements tends to be concentrated in dominant actors when coordination and learning mechanisms that support the upgrading of local suppliers are absent [

4,

5]. Thus, a tension arises between the need to preserve traditional knowledge and territorial identity, and the urgency to enhance the performance of the chain according to sustainability criteria.

Inclusive innovation offers a valuable framework for addressing these gaps, as it emphasizes appropriate technologies, community participation, distributive justice, and capacity-building throughout the processes of creating, adopting, and disseminating innovations [

6,

7,

8]. Methodologically, this study employs qualitative tools such as interviews and focus groups, alongside quantitative methods including producer characterization surveys, farm georeferencing, and agent-based modeling. Although the latter yields quantitative outputs, it is informed by qualitative data. This approach responds to local capacities through hybrid schemes that integrate market standards, while seeking to avoid isolated pilot interventions that fail to transform value chain governance. Emphasis is placed on the role of inclusive intermediaries who bridge knowledge, institutions, and markets within contexts of asymmetric power [

9,

10,

11,

12].

This study offers a dual contribution. Conceptually, it proposes an integrative framework that links inclusive innovation, value chain governance, and territorial performance, an approach rarely explored in the existing literature, making this a pioneering study intended to serve as a reference for future research. Practically, it presents a model with operational criteria that can support the design of replicable interventions in other Latin American crops. The findings show that combining community capacities, technical and institutional support, fairer commercialization mechanisms, and coordination arrangements oriented toward joint learning enables value redistribution toward the origin, enhances value chain resilience, and expands opportunities for women and youth all without compromising cultural coherence or environmental sustainability [

1,

2,

3,

4,

7].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method

This manuscript is structured as an exploratory–explanatory case study, following a mixed-methods approach with a qualitative emphasis. It is grounded in the principles proposed by Bunge [

13] regarding the combination of methodological pathways to address complex phenomena, as well as in the holistic perspective of Hurtado [

14], which promotes the integration of social, cultural, and technical dimensions. In this regard, the study incorporates Creswell’s [

15] approach to coherently and contextually articulate qualitative and quantitative designs in applied social research [

16]. Accordingly, the research contributes to applicable and transformative knowledge from multiple dimensions.

2.2. Methodology

This study explores the causal relationships between the social, productive, and governance conditions of prickly pear cultivation and the potential for its sustainable strengthening through inclusive innovation strategies. Methods of direct observation, systematic analysis, and inductive-deductive reasoning are employed, enabling the construction of inferences from specific territorial experiences toward broader interpretive models, in line with the epistemological postulates of Bunge [

13].

Fieldwork was conducted between December 2024 and August 2025 across 14 villages (veredas) in the municipality of Sonsón. It included the administration of structured, population-based surveys covering all local producers, totaling 112 families, with a focus on sociodemographic, productive, and service access variables. The population was composed of 46% women and 54% men; additionally, 21% were youth under the age of 20, and 17% were internally displaced persons.

The study followed a concurrent mixed methods design. Three focus groups were conducted with 18 producers selected based on criteria of seniority, geographic location, and diversity of experiences. 12 semi-structured interviews were also carried out with key actors in the local ecosystem, including public officials, peasant leaders, processors, and academic technicians. Participatory techniques such as social cartography and collective mapping of the production process were employed, along with an observation instrument designed to characterize the commercial dimension, including distribution channels, sales modalities, and market perceptions.

The research combined primary and secondary sources, following Hurtado’s [

14] holistic approach, complemented by document review and bibliographic analysis as outlined by Sabino [

17]. Data processing followed a mixed methods approach, in accordance with the methodological guidelines of Sampieri [

18]. Quantitative data were processed using Excel and IBM SPSS Statistics 29.0.0, applying descriptive statistics and non-probabilistic cluster sampling [

19].

Qualitative data were compiled and subjected to analytical triangulation in Excel, with the refined data used to construct thematic analysis using Atlas.ti.8. The approaches were integrated through a nested concurrent triangulation design, with priority given to qualitative data such as interviews, focus groups, and direct observation processes. Results were presented in tables, graphs, and cross-tabulated matrices, following the systematization guidelines proposed by Méndez [

20] for social and business research.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

The research was conducted with institutional approval from the Universidad Católica de Oriente, the Municipality of Sonsón, and the Alianza Oriente Sostenible (AOS). All participants signed informed consent forms, ensuring respect for the community, confidentiality of the information, and adherence to ethical standards throughout the research process.

3. History and Culture of the Crop

Ethnographic and testimonial findings from the villages of Sonsón reveal that the cultivation of prickly pear has deep roots in the region’s agricultural history, dating back to the early 20th century, particularly in the villages of “Alto de Sabanas.” The prickly pear was initially introduced as a domestic plant with multiple uses, providing food, shade, boundary demarcation, and ornamental value. This domestic relationship fostered a sense of closeness and affection toward the plant. Sustained and promoted by farming families, the practice has been appropriated and transmitted across generations, becoming an empirical form of knowledge that is also part of the rural identity of Sonsón.

Field evidence suggests that the “prickly pear community” relationship has been preserved largely through the efforts of rural women and older adults, who have maintained the cultivation under adverse conditions such as rural population aging, social conflict, pressure from commercial monocultures, lack of technical assistance, and the absence of generational renewal. In this regard, the prickly pear has functioned as a relational good, which Bourdieu [

21] defines as a resource imbued with affective, cultural, and symbolic meanings that transcend its economic value.

These actors have contributed to sustaining a peasant economy based on reciprocity, where the commercialization of prickly pear occurs primarily through informal channels via trusted intermediaries or direct sales among neighbors. This has solidified the crop as an expression of cultural and territorial resistance, in line with what Silva [

22] and Toledo [

23] refer to as agroecological heritage: a set of knowledge, practices, and biodiversity tied to the territory and its collective memory. However, agronomic decisions continue to rely on traditional knowledge and manual tools, reflecting an ongoing tension between cultural and technical sustainability [

24]. Nevertheless, all producers expressed interest in receiving technical training, indicating a willingness to modernize without compromising the cultural values embedded in cultivation.

Within this context, prickly pear remains a part of peasant identity in the face of agricultural homogenization, which is primarily driven by avocado and coffee (65%), followed by tamarillo and lime (15%). Although it occupies a minority share, it still accounts for approximately 12% of the agricultural area, mainly within family farms, home gardens, orchards, and living fences. This reflects territorial continuity and highlights the value of traditional agricultural practices in rural innovation processes, which, as Cummings [

25] argues, do not arise solely from the introduction of external technologies but also from the recognition of traditional knowledge and local farming practices.

3.1. Productive Dynamics and Technological Gaps

The system is characterized by heterogeneity, aging productive infrastructure, and limited expansion. Small-scale agriculture predominates, with minifundiums representing 82% of producers. These are composed mainly of family units with low levels of mechanization and limited access to cultivation technification processes, and a strong reliance on traditional knowledge [

26]. This situation affects the overall performance of the crop, which although it allows for weekly harvests and provides a steady income stream (cash flow) operates with narrow profit margins (See

Table 1).

From a technological standpoint, there is a low adoption of modern practices: pruning, waste management, and phytosanitary control are carried out empirically, without standardized protocols, which contributes to the incidence of diseases such as scab, rot, and seepage. This situation is compounded by the fact that producers face financial and technical constraints to invest in machinery [

27]. Additionally, the lack of planning, weak associativity, and limited technical assistance are factors that undermine rural competitiveness [

28].

At the regional level, there is a noticeable technological gap, particularly in access to and use of information technologies, one that could be reduced through technical training programs tailored to the rural environment [

29,

30]. In parallel, some agroecological practices with more aggressive commercial dynamics have led to the displacement of prickly pear cultivation in certain areas of the municipality [

31].

Spatially, the distribution of prickly pear cultivation is atomized, with strong dependence on intermediaries and weak territorial coordination, which according to Cazella and Búrigo [

32] undermines competitiveness and limits the agroindustrial development of prickly pear production in the region.

3.2. Agroecological, Spatial Conditions and Territorial Concentration of Production

Agroecological changes have emerged as a response to the dominant agro-industrial model, driven by supply and demand, which has increasingly distanced producers from consumers and resulted in the erosion of commercial and associative ties, as well as ecological balance [

33]. In contrast, agroecology offers an alternative grounded in food sovereignty, environmental justice, and peasant knowledge. More than a technical solution, it represents a process of dialogue among the various actors in the production chain, one that values traditional knowledge, fosters learning networks, and strengthens local governance [

34,

35]. In Sonsón, where family farming plays a fundamental role, prickly pear cultivation stands out as an agroecological option that preserves peasant identity and promotes territorial sustainability [

36].

The cultivation of prickly pear in the municipality of Sonsón, Antioquia, takes place under a set of agroecological, climatic, and territorial conditions that create a highly favorable environment for continuous production. This system is located within an altitudinal range between 1500 and 2600 m above sea level, where average temperatures range from 17 °C to 23 °C, relative humidity is around 60%, and annual rainfall varies between 600 and 1100 mm. These parameters support the physiological development of the crop, reduce the incidence of diseases, and enable the production of consistently high-quality commercial fruit [

37]. Additionally, the influence of air currents from the Cauca River, the Aures River, and the winds from the Nevado del Ruiz contribute to thermal stability and reduce the impacts of abrupt climate changes, generating agroclimatic resilience [

38].

Territorial analysis reveals a correlation between productive villages and their respective thermal zones. In villages located between 2400 and 2600 m, such as “El Brasil” and “Alto de Sabanas,” higher levels of diffuse radiation, cooler nighttime temperatures, and conditions favoring firmness, coloration, and shelf life of the fruit are observed ideal characteristics for specialized or export markets [

39]. In contrast, villages located between 2000 and 2200 m present slightly warmer temperatures that accelerate ripening, allowing for harvests up to two weeks earlier than in higher areas. This dynamic suggests the feasibility of implementing staggered harvesting routes, which would support a continuous supply of fruit throughout the season and open differentiated market windows [

37].

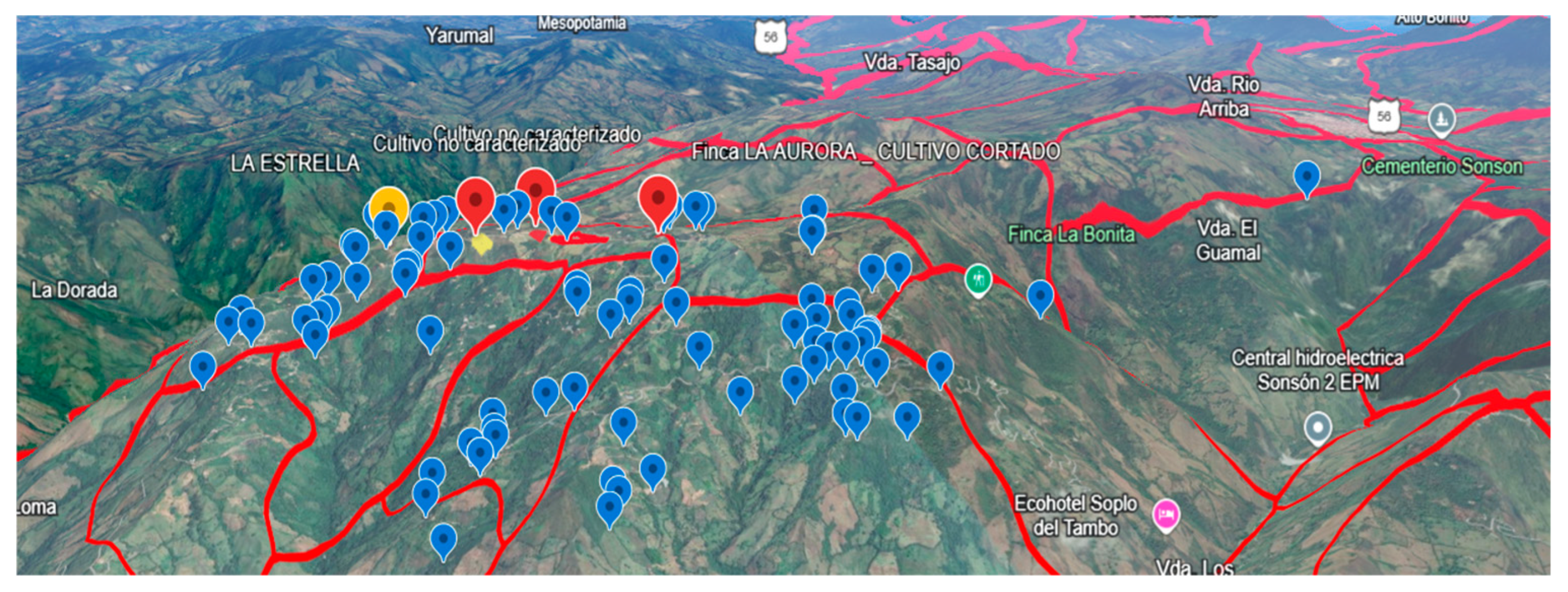

During the characterization process, a database was compiled containing 112 farms with geographic coordinates and minimum productive records, including cultivated area, crop age, and yield. This information was integrated into a Geographic Information System (GIS), which enabled the spatial visualization of the most consolidated production hubs, such as “Roblal Arriba” and “El Brasil,” as well as the identification of dispersed productive zones in peripheral villages. The GIS also revealed significant variations in accessibility, topography, and microclimatic conditions factors that are essential for planning differentiated interventions, guiding technical assistance, and designing commercially strengthening strategies based on empirical evidence.

Prickly pear cultivation is distributed across 14 villages in the municipality, with a marked concentration in a central productive corridor. Villages such as “Roblal Arriba” and “El Brasil” account for 41% of the characterized farms, followed by “Hidalgo,” “Alto de Sabanas,” and “La Aguadita.” This pattern indicates that over half of the production is located within a radius of less than 6 km, representing a strategic opportunity to organize technical assistance processes, peer-to-peer training, and collective aggregation. “Roblal Arriba” and “El Brasil” not only concentrate more than 20% of the total production each but also report yields above 16 t/ha (tons per hectare), a technical unit that expresses the quantity of fruit obtained per unit of cultivated area.

The integration of GIS with direct field observations, interviews with producers and institutional actors, and participatory exercises in the villages significantly improved the quality of the territorial diagnosis and deepened the understanding of the spatial logic of prickly pear cultivation in Sonsón. This tool not only enabled the visualization of productive hubs and the characterization of variables such as altitude, slope, and accessibility, but also facilitated the identification of patterns of concentration, dispersion, and agroclimatic suitability.

The integration of GIS with qualitative instruments enhanced the quality of the territorial diagnosis and deepened the understanding of the spatial logic of prickly pear cultivation in Sonsón. Additionally, it served as a technical tool for decision making related to territorial planning of the crop, the design of staggered harvest routes, the segmentation of zones based on agroecological conditions, and the projection of associated value chains. The combination of empirical data with spatial analysis generated applicable scenarios for technical assistance, commercial coordination, and the formulation of local public policies. As Zhang [

40] the use of participatory cartographic tools enables the construction of intervention models grounded in territorial evidence, strengthening agrarian governance and rural planning capacity from an integrative perspective (See

Figure 1).

This set of agroclimatic conditions positions Sonsón as the only municipality in Antioquia capable of sustaining continuous prickly pear production throughout the year. This comparative and competitive advantage creates opportunities for the implementation of origin labels, the promotion of differentiated agroecological practices, and the development of territorial valorization strategies framed within rural tourism, gastronomic experiences, and small-scale agroindustry.

4. Commercialization: Bottlenecks and Structural Dependence

Field analysis reveals that the prickly pear commercialization system in Sonsón operates under a highly concentrated model, with limited participation of producers in strategic decision making. The evidence points to an oligopsony-type structure, as defined by Rogers and Sexton [

41], in which prices are set and distribution channels are determined without consulting farmers, thereby restricting their bargaining power and economic autonomy (See

Figure 2). This configuration constitutes a structural barrier that not only limits the adoption of agricultural technologies but also perpetuates dynamics of informality and dependence, ultimately undermining the sustainability of the local agrifood system [

42].

Considering this scenario, value chain analysis offers a key tool for understanding how the value generated within the prickly pear production system is distributed. In this context, small-scale producers face a power asymmetry [

3] that places them at a disadvantage compared to actors with greater institutional or commercial capacity, such as processors and traders. These unequal relationships result in schemes where technical standards, certifications, and market requirements are defined by the stronger links in the chain, without considering the structural limitations of smallholder farmers. As a result, market access is conditioned by the ability to meet costly requirements that are not always accompanied by clear incentives or support mechanisms [

43].

Given this, value chain governance plays a fundamental role in defining not only the rules of engagement among key actors but also the mechanisms through which power is distributed, conflicts are managed, and strategic alliances are built. In the case of prickly pear production in Sonsón, the absence of inclusive governance has created coordination gaps that weaken the production chain. The active involvement of public entities, such as the municipal government, becomes essential to generate enabling conditions through clear regulations, specialized technical assistance, and negotiation platforms [

43].

A specific focus on value chain governance refers to the way in which rules are established among actors, how they are implemented, and who holds control over them, thus determining the distribution of benefits among the actors involved [

5]. According to Gereffi [

4], there are five types of governance that shape relationships and power within the chain: Market governance, where relationships are simple and regulated by prices; Modular governance, involving complex but codifiable interactions; Relational governance, based on trust and close ties; Captive governance, characterized by the dependence of small suppliers; and Hierarchical governance, involving vertical control, typical of integrated structures. These typologies help to understand how control and cooperation dynamics vary across different productive and commercial contexts.

In analyzing the prickly pear value chain in Sonsón, a predominance of captive governance is observed, in which, according to Gereffi [

4], small producers face a high degree of dependency on more powerful actors, such as intermediaries or processors. This situation limits their agency and bargaining capacity, affecting the fair distribution of value. To overcome this, it is necessary to strengthen associative processes, improve institutional coordination, and promote more equitable commercialization models based on inclusive innovation and participatory governance [

44].

However, despite this adverse productive structure and the logistical limitations that severely undermine the competitiveness of prickly pear cultivation, there remain sociocultural elements that contrast with this precariousness and could serve as catalysts for transformation. While weak organizational structures and the lack of infrastructure consolidate an unfavorable oligopsony environment for producers, the cultural rootedness of the crop and the presence of heritage orchards in the terms of Koohafkan and Altieri [

45] offer a different narrative, in which tradition can be revalorized as a tool for social cohesion looking toward the future.

In contrast to the current disarticulation, these identity-based elements make it possible to envision scenarios where current forms of associativity and collective training enable new models of collaborative governance [

46], aimed at recovering the value of the prickly pear as a driver of territorial development. These dynamics strengthen the rural social fabric, improve negotiation capacity with other actors in the chain, and help position the prickly pear as a traditional product of the municipality.

The reliance on intermediaries is exacerbated by geographic barriers such as topography, which leads to significant losses during the post-harvest process. However, these limitations also represent a strategic opportunity: the historical cohesion around prickly pear cultivation could facilitate the reactivation of associative forms. Although the lack of organization limits the capacity to respond to the concentrated power of the market, the promotion of training processes and collaborative governance could break the cycle of low prices and declining motivation to continue cultivation.

Nevertheless, prickly pear cultivation presents global advantages that position it as a strategic crop: its high nutritional value, adaptability to arid climates, and potential in healthy food markets. However, these opportunities coexist with structural challenges that hinder its effective insertion into global value chains. The high perishability of the fruit, variability in quality, and low consumer awareness demand comprehensive solutions that combine technological innovation and organizational strengthening. In Sonsón, a chain marked by informality and weak institutional coordination could be transformed through strategies that strengthen associativity, modernize production, and enhance commercialization without losing sight of the symbolic and cultural capital that sustains this agricultural practice and grants it territorial identity.

5. Innovation, Transformation, and Market Alternatives

Despite structural limitations, an emerging local innovation ecosystem around prickly pear cultivation is beginning to take shape in Sonsón. Ethnographic findings and data collected from focus groups reveal that some producers have initiated small-scale transformation processes, producing artisanal goods such as jams, wines, sweets, and culinary preparations based on prickly pear and nopal. These initiatives have been led primarily by rural women, who have employed creative strategies to diversify the crop’s uses and enhance its symbolic and economic value.

However, these experiences still require stronger technical support, business mentoring, and connection to broader institutional and commercial networks. The lack of standardized prototypes, labeling, sanitary certifications, and branding strategies limits their consolidation as competitive value-added lines. In this context, it is essential to implement product design and incubation programs with a market-oriented approach, territorial identity, and economic sustainability programs that both recognize and strengthen local knowledge systems.

In parallel, the associative fabric within the prickly pear production ecosystem faces significant challenges. Current cooperation practices are mostly limited to neighborhood ties, such as tool sharing or informal coordination of transport, while a historical distrust toward collective processes persists, stemming from past failed experiences with cooperatives. However, this scenario also opens the door to envision new forms of organization that are more inclusive, transparent, and adapted to the realities of smallholder farmers. Additionally, the concentration of purchasing power in the hands of intermediaries and the lack of rural participation mechanisms limit access to fairer markets and reduce the possibilities for shared innovation.

Overcoming the current fragmented landscape requires the construction of collaborative governance frameworks that rebuild trust among producers, promote training processes with a differential approach, and support commercialization models that recognize and value territorial diversity. In this context, the concept of inclusive innovation becomes especially relevant. This concept is understood as an intentional process aimed at reducing social exclusion through innovation, with a bottom-up structure that encourages co-creation with the community [

6,

7,

11].

This approach suggests that innovation should not only unlock the economic potential of strategic products such as prickly pear cultivation in the municipality of Sonsón, but also strengthen the social fabric, expand opportunities for rural women and youth, and position the territory as a benchmark for sustainable agroindustry with a unique identity [

8]. As Villalba [

47] and Foster and Heeks [

9] emphasize, the success of these systems depends on the articulation of actors with both innovation and inclusion capacities, on the recognition and valorization of traditional, scientific, and technological knowledge, and on the strengthening of inclusive intermediaries capable of integrating historically excluded actors into knowledge generation and appropriation dynamics.

6. Proposed Model of Inclusive Innovation

Building on the scalable inclusive innovation model proposed by Villalba [

10], this study presents a context-specific adaptation that addresses the sociocultural, productive, and governance conditions of prickly pear cultivation in Sonsón. This approach follows the premise that inclusive innovation must be an intentional process of endogenous development [

48,

49], one that integrates technical, economic, and cultural capacities with the active participation of historically excluded actors [

6,

7]. Drawing from the five pillars proposed by Villalba [

10], and considering the specificities previously analyzed, the following section outlines the foundational elements that guide this proposal (See

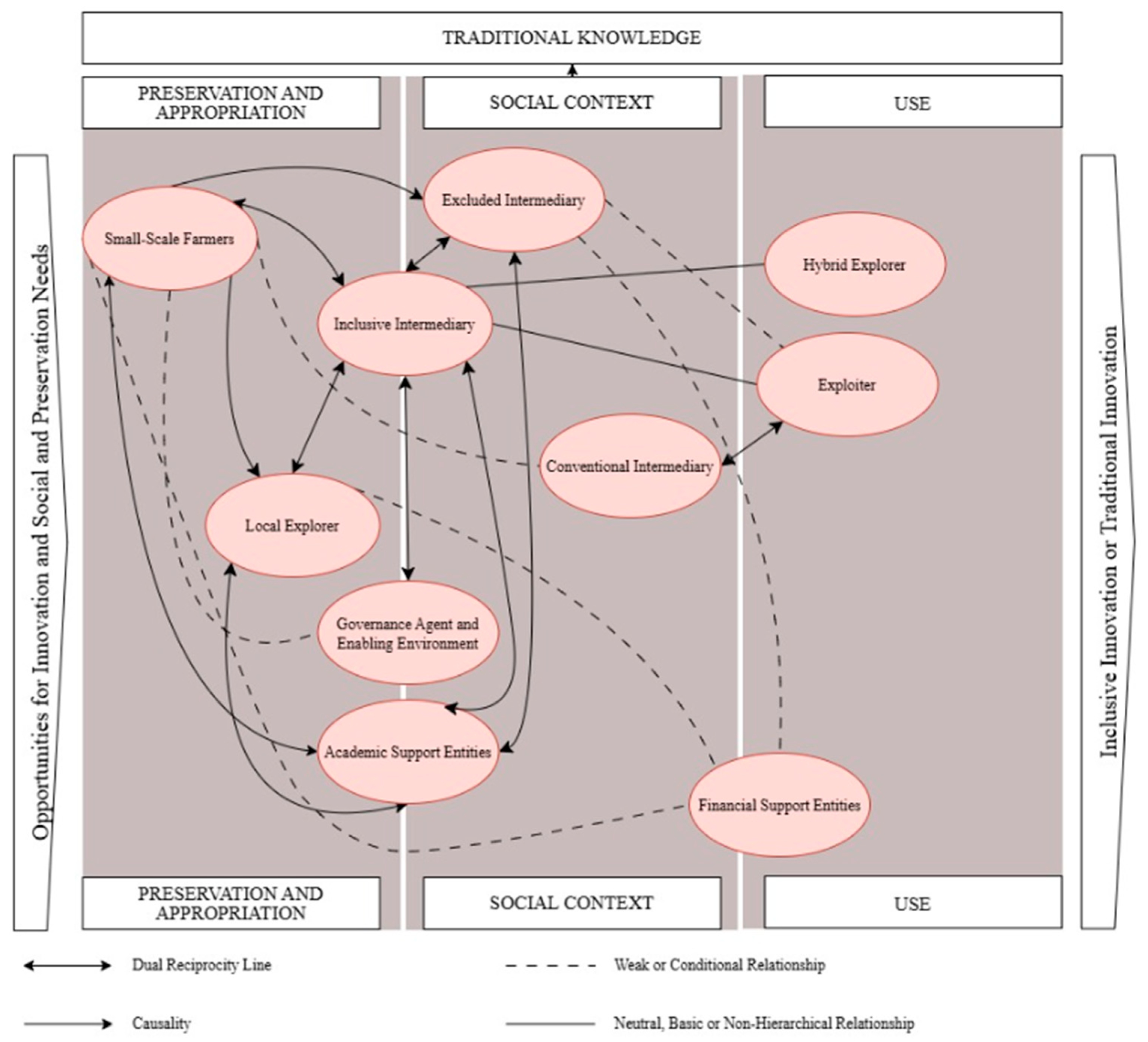

Figure 3).

- 1.

Innovation Base: In the model proposed by Villalba [

10], this foundation focuses on appropriate technological development, the adaptation of tools, and the technical validation of productive processes and prototypes. In the case of Sonsón, while the technological orientation is maintained, the emphasis shifts toward the balanced integration of technical innovations with peasant knowledge systems, recognizing that solutions must respond not only to efficiency criteria but also to the feasibility of adoption by small-scale producers. This hybridization between scientific and empirical knowledge serves as a bridge to improve post-harvest management, standardize phytosanitary protocols, and optimize cultivation practices without eroding the local agroecological heritage [

8,

9].

- 2.

Entrepreneurship Base: For Villalba [

10], the entrepreneurship base is structured around business training, the opening of commercialization channels, and access to microfinance. In the context of Sonsón, this component is reconfigured as associative entrepreneurship, in the sense proposed by Schmitter and Streeck [

50], which acknowledges past failures in formal associativity and proposes the development of entrepreneurial capacities through networks of progressive trust, with a particular emphasis on the leadership of rural women and youth. Additionally, priority is given to the articulation with differentiated markets that value territorial identity and productive diversification as strategies for risk mitigation [

6,

7].

- 3.

Cultural Base: In the framework proposed [

10], this base aims to safeguard peasant identity and traditional knowledge as pillars of inclusive innovation. In Sonsón, this dimension takes on a strategic nuance: prickly pear cultivation is not merely an agricultural activity but also a symbol of cultural resistance against agricultural homogenization. Its patrimonial value can become a key asset for accessing specialized markets. From this perspective, the valorization of historical memory and agroecological heritage emerges as a differentiating resource that, when properly managed, strengthens social cohesion and territorial resilience [

45].

- 4.

Governance Base: Villalba [

10] conceptualizes this base as institutional articulation, the formulation of supportive policies, and the establishment of transparency mechanisms. In the case of Sonsón, this pillar takes on a transformative role by being proposed as a tool to overcome the captive governance that characterizes the prickly pear value chain. The proposal centers on strengthening producers’ bargaining power through collaborative frameworks that integrate public, private, and community actors, with the aim of equitably redistributing the value generated and ensuring the sustainability of the productive system [

4,

48].

- 5.

Enabling Environment: Villalba [

10] defines this base as the set of economic, political, and environmental conditions that support the sustainability of the productive ecosystem. In the case of Sonsón, this pillar is expanded to incorporate critical aspects of physical and logistical connectivity, such as storage and transportation infrastructure, as well as the use of geographic information systems (GIS) to plan staggered harvests and optimize commercial routes. Additionally, the implementation of origin labels and the promotion of differentiated agroecological practices are proposed to strengthen the market positioning of prickly pear products in both national and international markets [

36].

7. Key Actors in the Inclusive Innovation Model for Prickly Pear Cultivation in Sonsón

The configuration of the inclusive innovation model for prickly pear cultivation in Sonsón is based on an adaptation of the framework proposed by Villalba [

10], complemented by the methodological contributions of Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) as a tool to represent and analyze the dynamic interactions among actors, knowledge flows, and governance relationships [

12]. This approach enables the capture of both formal connections and informal practices, highlighting the role of historically marginalized actors and facilitating the identification of inclusion trajectories [

51]. In this context, five types of agents are identified, whose articulation is essential for the functioning of the innovative ecosystem:

- 1.

Traditional Knowledge Promoters/Peasant Producers: Inspired by the concept of the “knowledge custodian”, this role in Sonsón is embodied by elderly producers, rural women, and families who have preserved the prickly pear cultivation tradition across generations. These actors safeguard an empirical body of knowledge that encompasses cultivation practices, varietal selection, natural pest control, and the multiple uses of the fruit, constituting an agroecological and cultural heritage that forms the foundation for contextualized innovation. Within the ABM framework, these agents act as nodes for the transmission of tacit knowledge, whose participation ensures that productive transformations do not erode territorial identity.

- 2.

Intermediaries: Intermediaries are key actors in linking producers to markets. According to Ruiz [

52], their central role lies in facilitating the flow of goods, information, and financial resources along the value chain, reducing transaction costs and assuming logistical functions such as aggregation, sorting, and distribution. However, this strategic position can also consolidate asymmetrical power relations that affect equity in the distribution of benefits, particularly in rural contexts where small-scale producers rely on limited commercialization channels.

In many territories, traditional intermediaries operate under schemes focused on supply chain efficiency and quality control, but without ensuring fair participation of producers in price formation. This phenomenon has been widely documented in small-scale agro-industrial chains, where market access depends on bargaining power, contact networks, and the technical requirements imposed by wholesale buyers. As a result, exclusionary dynamics emerge that marginalize associations and producers unable to meet such requirements or lacking the necessary infrastructure for aggregation and transportation.

In the case of Sonsón, these dynamics are evident in the prickly pear commercialization system, where producers generally depend on one or two local intermediaries who concentrate the purchase of fresh prickly pears, unilaterally set prices and payment terms, and prioritize product homogeneity, excluding smallholders who fail to meet size and quality standards

- 3.

Excluded Intermediaries: Based on the typology and systemic role of intermediaries in innovation systems proposed by Ruiz [

52], the first subset of agents is identified: excluded intermediaries. In the case of Sonsón, this group primarily consists of prickly pear producers’ associations that, due to institutional weaknesses and previously diagnosed coordination failures, have been unable to consolidate access to formal markets or have lost established connections with large buyers. In practice, these limitations have led to their exclusion from commercial circuits or participation in them with low bargaining power [

52]. This situation reduces their ability to contribute to technological diffusion and value addition and keeps them embedded in asymmetrical exchange relationships [

52].

- 4.

Conventional Intermediaries: A second subset is composed of conventional intermediaries. In the local context, these agents are responsible for collecting prickly pears at the village level in areas with productive potential, consolidating volume, and supplying larger-scale processors or traders. In addition to transportation logistics, they are typically in charge of basic quality verification and fruit classification. While they perform functions inherent to traditional channels, such as reducing search costs and coordinating transactions, their focus is primarily on commercial intermediation rather than the development of collective capacities. As a result, their contribution to innovation diffusion and the social linkage of knowledge is limited, since their economic incentives are mainly tied to the financial benefits derived from interactions with larger-scale traders [

52].

- 5.

Inclusive Intermediary: In recent years, the literature has increasingly adopted the category of inclusive intermediaries. In the case of Sonsón, this role is fulfilled by the Municipal Secretariat of Rural Assistance and Environment, which, according to Villa [

12], plays a strategic role in inclusive innovation systems by coordinating the bidirectional flow of knowledge between local actors and external networks. Their work, also documented in the Sustainability journal article, includes facilitating ongoing training processes, providing technical assistance tailored to the agroecological conditions of the territory, managing multi-actor cooperation networks, and promoting appropriate technologies that integrate social and environmental sustainability criteria [

53].

In Sonsón’s specific context, this agent proves critical as a catalyst for change: without its intervention, other actors lack the mechanisms, resources, and connections necessary to transform their individual capacities into collective outcomes. In Agent-Based Modeling (ABM), inclusive intermediaries are high centrality nodes that increase system connectivity, accelerate the adoption of inclusive innovations, and facilitate the transition from a fragmented and dependent ecosystem to one that is articulated and resilient.

Moreover, by reducing information asymmetries and negotiating better commercialization conditions, they strengthen participatory governance and expand the agency of historically marginalized producers, thus establishing themselves as the most decisive operational pillar of the inclusive innovation model for the prickly pear sector in Sonsón. As previously highlighted in the analysis of oligopsonistic structures, it is particularly important that this intermediary assumes an active role in price oversight and in mitigating the market concentration power of the oligopsony, thereby ensuring fairer commercialization conditions for smallholder farmers and traditional knowledge custodians

- 6.

Local Explorers: This type of agent refers to peripheral innovators, characterized by their pursuit of opportunities beyond conventional practices. In Sonsón, this category is embodied by young people and entrepreneurs who connect social innovation, the development of value-added products, and the opening of new commercialization channels, such as tourism routes and gastronomic fairs. From an Agent-Based Modeling (ABM) perspective, these explorers function as search and diversification agents, increasing the system’s resilience to external shocks while simultaneously expanding opportunities for integration into differentiated markets.

- 7.

Hybrid Explorers: A second category corresponds to hybrid explorers, who focus on the valorization of prickly pear as a basis for generating derivative goods that open new economic opportunities. This profile is reflected in individual initiatives by producers who, through artisanal or semi-industrial processes, produce jams, liquors, and other processed products. These practices not only expand and diversify the uses of the fruit but also strengthen income sustainability and contribute to greater economic resilience in the territory.

- 8.

Exploiter/Commercial Operator: In Sonsón, exploiters represent a segment of private entrepreneurs with the capacity to establish strategic partnerships with exporters or major fruit distributors, enabling them to access specialized markets. According to Villa [

12], this role is key to ensuring economic sustainability within inclusive innovation systems, as it transforms accumulated knowledge into tangible competitive advantages. However, the limited national supply of the product and the municipality’s geographic location contribute to the persistence of a highly concentrated commercialization model, in which these actors hold a disproportionate amount of power within the value chain.

- 9.

Governance and Enabling Environment Agents: Inclusive innovation systems cannot be consolidated without an institutional framework that, in line with what was proposed by North and Bárcena [

54], facilitates coordination, establishes clear rules, and generates enabling conditions. In the case of Sonsón, this role is fulfilled by entities responsible for regulating and overseeing productive and environmental processes, such as the Colombian Agricultural Institute (Instituto Agropecuario Colombiano—ICA) in matters related to agriculture and exports, and the Regional Autonomous Corporation for the Basins of the Negro and Nare Rivers (Corporación Autónoma Regional de las Cuencas de los Ríos Negro y Nare—CORNARE) regarding environmental management practices. Likewise, citizen participation mechanisms and emerging community associations represent important institutional components. In this process, the inclusive intermediary plays a transversal relational role by articulating and facilitating the flow of information and trust among producers, institutions, and markets.

- 10.

Academic Support Entities: This group is composed of universities and educational and research institutions that play a fundamental role in inclusive innovation systems. Their contribution goes beyond the training of human capital; it also includes the preservation and valorization of local knowledge, the production and transfer of scientific and technological knowledge, and the integration of territorial actors into the National System of Science, Technology, and Innovation.

According to Villa [

12], these entities fulfill a strategic function by articulating dispersed capacities and fostering the bidirectional flow of knowledge among communities, the productive sector, and government institutions. This not only allows for the adaptation of technological solutions to the agroecological and sociocultural conditions of the territory but also strengthens participatory governance and collective learning, essential elements for innovation to be both socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable.

In the case of Sonsón, universities and training centers can act as connection nodes between prickly pear producers, national and international academic networks, and high-value markets, facilitating applied research processes, certification, product transformation, and value-added generation.

- 11.

Financial Support Entities: This group is composed of financial institutions that facilitate the economic leverage of actors within the prickly pear production chain, including the Agrarian Bank (Banco Agrario), savings and credit cooperatives, and other financial entities. Their main function is to reduce gaps in access to formal credit by providing relevant, high-quality financing mechanisms tailored to agricultural production cycles and the specific needs of the sector.

According to De Olloqui, Andrade, and Herrera [

55], financial inclusion in Latin America and the Caribbean faces structural challenges such as low coverage in rural areas, a lack of financial products adapted to the needs of small-scale producers and limited financial literacy. Overcoming these limitations requires expanding the range of services, easing eligibility requirements, and promoting digitalization to reduce costs and barriers to access.

Similarly, Yaron, Benjamin, and Piprek [

56] emphasize that the design of rural financial instruments must consider income seasonality, liquidity constraints, and the institutional strengthening of financial entities operating in rural areas to generate a sustainable impact on local development.

In contexts like that of the municipality of Sonsón, where traditional collateral and borrowing capacity are often limited, these institutions can implement flexible credit products linked to associative schemes and value chains, so that financing becomes a catalyst for innovation rather than a barrier.

The adaptation of these types of agents to the context of Sonsón enables the mapping of existing relationships and the projection of transformation pathways in which inclusive innovation fosters economic sustainability, social cohesion, and the strengthening of cultural identity. The model proposes strategic routes to make prickly pear cultivation a profitable, sustainable, and culturally meaningful activity that contributes to territorial sovereignty and generational renewal.

The incorporation of responsible research and innovation practices, understood as processes that integrate social and inclusive innovation, strengthens sustainable development and provides the project with a methodological and ethical foundation for evaluating its economic, social, cultural, and environmental impact. This approach ensures that value chain strengthening responds to local challenges with community participation, environmental respect, and responsible governance, aligning rural innovation with collective wellbeing [

57].

8. Explanation of the Inclusive Innovation Model for Prickly Pear Cultivation in Sonsón

Figure 4 presents the positioning of the actors that make up the prickly pear ecosystem in the municipality of Sonsón, based on innovation opportunities and social needs, supported by three pillars: preservation and appropriation of the fruit and traditional knowledge, social context, and use. In this regard, it can be observed that some actors are in intermediate positions, as they participate in more than one link of the chain and their objectives are not limited to a single pillar. Additionally, the specific capacities of each actor are defined according to their role and contribution to the ecosystem, giving rise to either inclusive or traditional innovations.

In a second phase, the focus is placed on the interaction among actors based on their capacities and in correspondence with the pillars previously described. As a complement, the model illustrating these relationships is presented, using conventions from Atlas.ti.

Figure 4 shows how the peasant producer and the inclusive intermediary emerge as cross-cutting relational actors within the ecosystem, as reflected in the multiplicity of bidirectional lines. The peasant producer assumes this role due to their essential function in preserving both the fruit and the ancestral knowledge associated with it. In turn, the inclusive intermediary plays a transversal role by focusing on key processes for prickly pear producers, such as supporting the commercialization of the fruit and managing learning processes. This figure becomes particularly relevant when considering past failed attempts at association and commercialization, which largely faltered due to the absence of an intermediary prioritizing collective benefit over individual interests. Overcoming these limitations could strengthen associative processes and, consequently, enhance prickly pear commercialization.

In this scenario, the inclusive intermediary gains even greater importance, acting as a key player in the process of inclusive innovation, grounded in the endogenous capacities of the communities. This bottom-up development approach offers greater chances of success, since starting from the community allows for a more equitable balance among actors and reduces power asymmetries, particularly those of an oligopsonic nature, that in previous experiences hindered the consolidation of associative processes.

9. Limitations and Recommendations of the Research

The geographical location of prickly pear producers presents a challenge, as many are situated in remote and hard-to-reach rural areas, which may compromise the accuracy of population data. In fact, during the research process, a few cases were identified in which the prickly pear crops had been cleared. It is recommended to promote associativity processes that can help overcome the difficulties posed by limited accessibility and geographic dispersion, thereby facilitating data collection and coordination with other actors in the value chain.

The focus groups and semi-structured interviews were based on self-reported data from community actors; therefore, the information may be subjective, as it reflects perceptions, interpretations, and lived experiences, but may also be influenced by memory bias or social desirability. Additionally, the researcher’s interaction with local actors may introduce observer bias.

Access to systematized secondary information on prickly pear cultivation proved challenging due to the specific characteristics of the crop and its geographic location. A key methodological limitation lies in the absence of long-term cross-sectional data. It would be desirable to conduct studies with broader longitudinal designs that allow for more precise forecasting exercises to evaluate the long-term impacts of inclusive innovation. Additionally, further research is needed on native crops that are currently at risk of disappearing due to institutional weakness and the lack of policies aimed at protecting traditional knowledge.

It is further recommended that local authorities and public policy makers develop comprehensive agricultural information systems focused on non-traditional crops, in order to strengthen decision making, reduce data fragmentation, and promote the advancement of emerging crops. Future research is expected to contribute to the design of public policies, partnerships, or agreements aimed at generating monetary or non-monetary incentives to support the consolidation of inclusive intermediaries. Likewise, inclusive innovation projects should be leveraged to promote the cultivation of native species through the development of technologies and innovations that value Indigenous knowledge and ancestral practices.

10. Conclusions

The methodology, developed through a mixed-methods approach and combined with qualitative techniques such as in-depth interviews and focus groups, enabled the participation of rural communities, women and youth leaders, municipal administration, and universities. This demonstrated the project’s social component, alongside technical processes such as georeferencing and territorial characterization, which facilitated a comprehensive understanding of the prickly pear ecosystem in Sonsón. This process highlighted the potential for fostering inclusive innovation strategies, rural community cohesion, and territorial sustainability.

Prickly pear cultivation in Sonsón constitutes a high-value agro-productive system with significant patrimonial, economic, and socio-cultural importance. However, it faces bottlenecks such as weak local organization, dependency on intermediaries, limited generational renewal, and insufficient institutional coordination. In this context, a socially inclusive innovation model is proposed, one that integrates traditional knowledge and territorial capabilities, bringing together community, governmental, private, and academic actors to drive productive strengthening processes.

The application of the model goes beyond the context of Sonsón, given its scalable and modular structure, which is well suited for rural territories in Andean or semi-arid regions such as Colombia, Peru, or Mexico, where challenges such as the exclusion of small-scale producers and the breakdown of intergenerational continuity threaten biodiversity and traditional agricultural practices. Its focus on collaborative learning and adaptive governance makes it replicable across other agri-food chains involving traditional or native crops. However, its implementation requires robust institutional frameworks, with clear indicators, transparency mechanisms, and guarantees of distributive equity.

The model brings together elderly individuals as custodians of agroecological knowledge, alongside inclusive intermediaries who promote equitable linkages within the value chain. It is grounded in three pillars: preservation and appropriation of knowledge, social context, and use. Structured through a bottom-up approach based on local capacities, the model aims to reduce power asymmetries, promote fair trade schemes, and enhance value redistribution. In this context, the inclusive intermediary emerges as a key governance agent for fostering endogenous development and territorial resilience.

Strengthening trust-based relationships among local actors is essential to overcoming historical fragmentations and fostering synergies and cooperation between producers and institutions. The model proposes fair marketing channels and agro-industrial transformation as key value-added strategies. This vision, aligned with principles of territorial social responsibility, enables prickly pear cultivation to be not only profitable but also relevant and equitable [

44].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.V.A., Y.P.D.C. and D.A.V.R.; Methodology, C.C.V.A., Y.P.D.C. and D.A.V.R.; Software, C.C.V.A., Y.P.D.C. and D.A.V.R.; Validation, C.C.V.A., Y.P.D.C. and D.A.V.R.; Formal analysis, C.C.V.A., Y.P.D.C. and D.A.V.R.; Investigation, C.C.V.A., Y.P.D.C. and D.A.V.R.; Data curation, C.C.V.A., Y.P.D.C. and D.A.V.R.; Writing—original draft, C.C.V.A., Y.P.D.C. and D.A.V.R.; Writing—review and editing, C.C.V.A., Y.P.D.C. and D.A.V.R.; Visualization, C.C.V.A., Y.P.D.C. and D.A.V.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project is developed and proposed by Universidad Católica de Oriente, with the support of Alianza Oriente Sostenible (AOS), funded by the European Union. It is a regional initiative committed to strengthening the agro-industrial sector and promoting sustainability in Oriente Antioqueño.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Comité de Ética de la Universidad Católica de Oriente. This project is part of an agreement approved by the Alcaldía de Rionegro (Antioquia, Colombia), in which the ethical guidelines are established in Clause 18, under the identification code 1000 07 019 2020 PS0037-2024, approved on 4 December 2024, and registered in the Electronic System for Public Procurement (SECOP II).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO; ICARDA. Crop Ecology, Cultivation and Uses of Cactus Pear; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy; International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas: Beirut, Leb anon, 2017; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i7012en/I7012EN.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Secretaría de Asistencia Rural y Medio Ambiente de Sonsón. Interviews and Technical Assessments for the Prickly Pear Project; Sonsón Mayoralty: Antioquia, Colombia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, R. Market power, misconceptions, and modern agricultural markets. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 95, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G.; Humphrey, J.; Sturgeon, T. The governance of global value chains. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2005, 12, 78–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, J.; Schmitz, H. Chain governance and upgrading: Taking stock. In Local Enterprises in the Global Economy: Issues of Governance and Upgrading; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2004; p. 349. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzens, S.; Sutz, J. Innovation in informal settings: Reflections and proposals for a research agenda. Innov. Dev. 2014, 4, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R.; Foster, C.; Nugroho, Y. New models of inclusive innovation for development. Innov. Dev. 2014, 4, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplinsky, R. Schumacher meets Schumpeter: Appropriate technology below the radar. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Heeks, R. Conceptualising inclusive innovation: Modifying systems of innovation frameworks to understand diffusion of new technology to low-income consumers. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2013, 25, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, M.L.; Ruiz Castañeda, W.; Robledo, J. Configuration of inclusive innovation systems: Function, agents and capabilities. Res. Policy 2023, 52, 104796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño, B.; Villalba, M.L.; Acosta, M.; Villegas, C.; Calderón, E. Towards the conceptual understanding of social innovation and inclusive innovation: A literature review. Innov. Dev. 2022, 12, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, E.J.; Ruiz, C.A.; Robledo, J. Inclusive innovation systems configuration for rural territories: An agent-based modelling approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, M. La Ciencia: Su Método y Su Filosofía. Laetoli. 2018. Available online: https://users.dcc.uchile.cl/~cgutierr/cursos/INV/bunge_ciencia.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Hurtado, J. Metodología de la Investigación Holística; Servicios y proyecciones para América Latina: Caracas, Venezuela, 2000; Available online: https://ayudacontextos.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/jacqueline-hurtado-de-barrera-metodologia-de-investigacion-holistica.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Creswell, J.W.; Fetters, M.D.; Ivankova, N.V. Designing a mixed methods study in primary care. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charli, M.S.; Eshete, S.K.; Debela, K. Learning how research design methods work: A review of Creswell’s Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Qual. Rep. 2022, 27, 2956–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, C.A. El Proceso de Investigación; Panamericana Editorial: San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sampieri, R.; Mendoza, C. Metodología de la Investigación: Las Rutas Cuantitativa, Cualitativa y Mixta; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N. Investigación de Mercados: Conceptos Esenciales; Pearson Educación: Polanco, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, C.E. Metodología de la Investigación: Diseño y Desarrollo del Proceso de Investigación en Ciencias Empresariales; Alpha Editorial: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Razones Prácticas. Sobre La Teoría de La Acción; Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R. Hacia una valoración patrimonial de la agricultura. Scr. Nova 2008, 7, 741–798. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, V.M.; Barrera, N. La Memoria Biocultural: La Importancia Ecológica de Las Sabidurías Tradicionales; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, M. La identidad cultural del territorio como base de una estrategia de desarrollo sostenible. Rev. Ópera 2007, 7, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, A.R. Building innovation capabilities in small scale rural agro industries of El Salvador. Rev. Iberoam. Cienc. Tecnol. Soc.–CTS 2013, 8, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinosa, L.J. Los saberes tradicionales y los conocimientos científicos sobre dirección en la empresa latinoamericana: Puentes y barreras. Cofin Habana 2018, 12, 190–203. [Google Scholar]

- Cedeño, M.I.; Rosillo, G.B.; Sánchez, A.K. El Nivel de Producción y Su Aporte Al Desarrollo Local de la Parroquia Abdón Calderón del Cantón Portoviejo (Ecuador); En Hélices y anclas para el desarrollo local; Universidad de Cartagena: Cartagena, Colombia, 2019; pp. 256–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, J.E.; Díaz, Y.P.; Bohórquez, F.G. Análisis de la competitividad del sector agrícola de los municipios de Arbeláez y San Bernardo. Vestig. Ire 2017, 1, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Prada, U.E.; Orella, M.L.; Salinas, M. Apropiación de Sistemas de Tecnologías de la Información para toma de decisiones de productores agroindustriales basada en videojuegos serios. Una revisión. Inf. Tecnológica 2019, 30, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, F.S. Política agrícola en Costa Rica y su efecto sobre el campesinado: ¿Tendrá la educación “alguna vela en este entierro”? Rev. Electrónica Educ. 2022, 3, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I. Agroecology: A brief account of its origins and currents of thought in Latin America. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2017, 41, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazella, A.A.; Búrigo, F.L. Sistemas territoriais de financiamento rural: Para pensar o caso brasileiro. Emancipação 2013, 13, 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, D.H.; Moreno, M.d. Resistencia a la transición agroecológica en México. Región Soc. 2022, 34, e1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Toledo, V.M. The agroecological revolution in Latin America: Rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants. J. Peasant. Stud. 2011, 38, 587–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, O.F.; Rosset, P.M. La agroecología en una encrucijada: Entre la institucionalidad y los movimientos sociales. Rev. Bras. de Desenvolv. Territ. Sustentável 2016, 2, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliessman, S.R. Agroecología: Plantando las raíces de la resistencia. Agroecología 2013, 8, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- David, O.O. Manejo Post-Cosecha Del Higo (Opuntia Ficus-Indica). Paquetes de Capacitación Sobre Manejo Post-Cosecha de Frutas y Hortalizas, No. 10. SENA, Bogotá. 1998. Available online: https://repositorio.sena.edu.co/handle/11404/6062 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Pabón, J.D.; Arias, P.A.; Espinoza, A.F.; Flores, J.C.; Goubanova, L.F.; Lavado, C.; Masiokas, W.; Solman, M.H.; Villalba, R. Observed and projected hydroclimate changes in the Andes. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokar, A.; Zare, H.; Zakerin, A.; Jahromi, A.A. Influence of photo-selective nets on tree physiology and fruit quality of fig (Ficus carica L.) under rainfed conditions. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2021, 21, 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ruijs, A.; Van, I.E. Economic performance of agrienvironmental policy in China: A GIS-based multi-objective analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 85, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.T.; Sexton, R.J. Assessing the importance of oligopsony power in agricultural markets. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1994, 76, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongabo, P. Technology and innovation trajectories in the Rwandan Agriculture sector: Are value chains an option? Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2022, 14, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallontire, A.; Greenhalgh, P. Establishing CSR Drivers in Agribusiness; Natural Resources Institute: Kent, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez, D.A.; Palacio, S.A. Un acercamiento a la comprensión de la responsabilidad social empresarial en comercializadoras y productores de hortensias en el Oriente antioqueño. Lebret 2017, 9, 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Koohafkan, P.; Altieri, M.A. Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems: A Legacy for the Future; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cerroblanco, V.; López, M.; Vega, D. Asociatividad y cadenas de valor: Estudio de caso de una marca colectiva de mezcal en Guanajuato, México. PSN: Other International Political Economy: Trade Policy (Topic). Rev. Acad. Neg. 2021, 7, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, M.L. La Emergencia de Los Sistemas de Innovación Inclusivos: Aportes a Su Comprensión Desde la Modelación Basada en Agentes. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/82168 (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Vázquez, A. Desarrollo endógeno y globalización. Eure 2000, 26, 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, A. Desarrollo endógeno. Teorías y políticas de desarrollo territorial. Investig. Reg.-J. Reg. Res. 2007, 11, 183–210. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitter, P.C.; Streeck, W. The Organization of Business Interests: Studying the Associative Action of Business in Advanced Industrial Societies (MPIfG Discussion Paper 99/1). Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies; Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung: Köln, Germany, 1999; Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/43739/1/268682569.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Sutz, J. Ciencia, Tecnología, Innovación e Inclusión Social: Una agenda urgente para universidades y políticas. Psicol. Conoc. Soc. 2010, 1, 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, W.L. Análisis del Impacto de Los Intermediarios en Los Sistemas de Innovación: Una Propuesta Desde El Modelado Basado en Agentes. 2016. Available online: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/56636 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Agrosavia. Modelo de Transferencia de Tecnología Participativo; Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria: Bogotá, Colombia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C.; Bárcena, A. Instituciones, Cambio Institucional y Desempeño Económico; Fondo de Cultura Económica: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- De Olloqui, F.; Andrade, G.; Herrera, D. Inclusión Financiera en América Latina y El Caribe: Coyuntura Actual y Desafíos Para Los Próximos Años; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID): Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yaron, J.; Benjamin, M.; Piprek, G. Rural Finance: Issues, Design, and Best Practices; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez, D.A.; Duque, Y.P.; Villalba, M.L.; Torres, C.; Gil, A.M.; Arango, M.I.; Aguirre, D.A. Using of Social Return on Investment Index-SROI as Tool of Responsible Research and Innovation. Colombian University Case. In Proceedings of the International Association for the Management of Technology Conference, Porto, Portugal, 8–11 July 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 163–171. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

_Li.png)