1. Introduction

The year 2022 marked the time when the size of the worldwide impact investing market topped the USD trillion mark (1.164 trillion USD according to the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN)—[

1]). In 2024, the size of the impact market reached 1.571 trillion USD [

2]. Between 2015 and 2024, the impact market expanded at an extraordinary pace, rising from USD 77.4 billion to USD 1164 billion—on average, this translates into a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of approximately 35 percent.

This is a positive trend for increasing mobilization of private finance for development which is, however, also associated with serious challenges for investors. One of the main challenges that the industry faces is how to distinguish impact investing from other sustainable or responsible (aligned) investments [

3]. With the GIIN defining impact measurement and management as “identifying and considering the positive and negative effects one’s business actions have on people and the planet, and then figuring out ways to mitigate the negative and maximize the positive in alignment with one’s goals” [

4], the difficulty in importantly differentiating impact investing from other forms of sustainable or responsible investing indeed remains. This is due to two main reasons: the first is associated with the emergence of many (aligned) financial products and services that claim to be impact investments but lack a genuine net positive impact contribution for the planet and society. The second reason is linked to the proliferation of bespoke impact metrics, many of which lack rigorous criteria underpinning their selection and use. The use of impact metrics is mostly concerned on the one hand, with impact reporting and, on the other, with impact performance measurement. However, the measurement of impact performance remains so far underdeveloped. Thus, there is a need to further harmonize how the impact performance of investments is measured to appropriately inform investors’ decision-making.

In this paper, we argue that in order to close the estimated financing gap of around

$4 trillion additional investment needed annually for developing countries that is required to achieve the sustainable development goals (SDGs) [

5], investors need crucially to be provided with access to robust yet simple impact performance metrics: First, as resources are scarce, finite, and mutually exclusive, development finance needs to be channeled to investments with the strongest impact potential with regard to the SDGs. Unlocking SDG-relevant capital will depend, even more, on effective methods that allow for ex ante decision-making amongst investment options and ex-post assessment of net forecasted and resulting impact of these investments. Second, consensus on impact performance metrics, i.e., standardization in impact measurement will allow impact investors to know whether they have attained their SDG-intended impact based on and measured comparatively to widely accepted impact measurement and impact management practices. Third, differentiating impact from aligned investments is important because many financial products and services claim to be impact investments but lack a genuine net positive impact contribution for the planet and for society (impact washing). In other words, impact investors, such as Development Financial Institutions (DFIs), governments, foundations, pension funds and others will gain access to and benefit from robust impact performance metrics that will help them move to systematically reporting incremental impact towards SDG goals, and which allows comparability of efficacy as well as efficiency across projects and institutions over time.

It could thus be argued that impact performance measurement needs to move in a similar direction to how (robustly) financial performance is assessed (e.g., with well-defined indicators such as return on equity, return on assets, risk-adjusted return, etc.). Similarly to financial performance analysis, impact performance measurement would consider the impact position of investments and investees within their operating context. In this regard, impact performance analysis should focus on reviewing, assessing, and comparing impact metrics disclosures and other contextual information across investors and projects. In short, for impact investing to continue to grow and to allocate resources efficiently, it needs to be able to rely on impact performance metrics that foster comparability between investments around similar impact sectors and themes.

The objective of this study is to contribute to the development and implementation of a “synthetic” impact performance measurement approach by proposing a set of rigorous impact performance metrics—based on a theory of change (ToC) and inspired both from practice and academia—for a defined pilot economic sector, that can be adopted by many impact investors and firms to assess the impact performance of their investments. We anticipate that this study will set solid methodological foundations in impact performance measurement for our intended audience which comprises primarily impact investors, such as the DFIs, as well as other institutions such as banks, private foundations, pension funds, insurance companies, family offices, individual investors, non-governmental organizations, and corporates that wish to reach impact objectives on part of their wealth allocation.

Impact performance measurement is important for several reasons. First, it enables impact investors to decide on the optimal allocation of their funds with respect to their generated net impact contribution. Second, impact performance measurement can enable these investors to track whether their expected net impact contributions were met over a specific horizon, or if corrective measures need to be taken ex-post (such as downsizing, adjusting, or even stopping a given investment project). Third, impact performance can, when contrasted with the financial performance measurement of investments, inform investors about potential “net impact versus financial performance” trade-offs, and when this is the case what they are willing to undertake to meet their dual objectives. Finally, comparable impact performance measurement is a prerequisite to enable the impact investing industry to grow efficiently and selectively to stir capital to those investments that have the highest incremental impact contribution over a specific horizon.

In our study, we first review the criteria for selecting impact metrics used by practitioners and academics, and based on that survey (

Supplementary Materials S1) and our own judgement, we propose a set of five relevant criteria (intentionality, measurability, feasibility, incrementality, and comparability) to select “proper” impact performance metrics that would enable impact investors to go beyond impact reporting needs towards enabling them to conduct impact performance measurement. Second, we screen impact metrics used by practitioners and in academic papers against these five criteria, for a specific economic sector.

This systematic approach led to the benchmarking of a sample of 84 impact metrics—selected from those proposed by academia and practice—for a pilot economic sector, namely credit finance, which is the sector that attracts the largest dollar amounts of impact investments. This sector is also unique in that it contributes only indirectly to net impact through its financial intermediation attribute, in this sense it is an enabler to the impact generation capacity of the real economy. In this benchmarking exercise, each selected impact metric was assessed against the predefined criteria to examine whether it fulfilled the necessary conditions to enable impact performance measurement. The goal was then to propose, based on our findings and an underlying ToC, a “selected” number of impact metrics that are deemed “relevant” for impact performance measurement within the credit finance sector.

The main findings of our study can be summarized as follows: First, there is a challenge around the availability of robust impact performance metrics. While there is a large number of financial metrics to assess the financial performance of investments, there are very few impact metrics that allow investors to capture impact performance effectively. Second, there is complementarity rather than substitutability between the set of impact metrics that are identified in the academic and practitioner literature. Third, we observed that out of the pre-selected metrics for the credit finance sector, more than half of the metrics passed the test of our first three criteria (intentionality, measurability, and feasibility, as elaborated in

Section 2.1) which are relevant for impact reporting. However, there was no single metric that passed the test of fulfilling all five criteria (that is, including incrementality and comparability), which are collectively needed for impact performance assessment. Furthermore, we observed that academic metrics do a better job of fostering comparability (55.6% versus 15.4% for the practitioner metrics). Thus, an important conclusion of our study is that the impact investing industry should consider adopting impact performance metrics that also satisfy the two last criteria proposed, namely, incrementality, and comparability. Finally, we propose a limited set of impact performance metrics based on a simplified theory of change for the credit finance sector, which satisfies the five proposed criteria.

While efforts are underway to harmonize existing impact metrics sets, our approach was to leverage and complement these initiatives. Indeed, our main contribution is to design a systematic approach to assess a large number of impact metrics in the credit finance sector under the prism of them enabling investors to also measure impact performance related to the main outcomes of the sector’s ToC. Our second contribution is that beyond looking at impact metrics and criteria used by practitioners, we also integrated impact metrics and selection criteria stemming from the academic literature. Third and most importantly, our benchmarking study further assessed which practitioner-proposed impact metrics are suitable for impact performance measurement. Finally, our benchmarking approach can be viewed as a common good that can be generalized to select proper impact performance metrics for other economic sectors and impact themes (e.g., agriculture, health, manufacturing, energy, jobs, gender, climate, and renewable energy) so that impact investors have a solid base to assess the overall impact performance of their investments and to benchmark their impact performance against the industry. This is in line with the potential role of academics in the “Roadmap for the Future of Impact Investing” proposed by the GIIN, partly described as “Develop and promote clear best practices... to address the current fragmentation of approaches and lay a foundation for analysis, rating, and comparing impact across investments within a given theme” [

6].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Our Proposed Impact Metrics Selection Criteria

In selecting our criteria, we followed three principles: First, the impact of a specific investment is different from the impact reported for a firm’s overall operations. In our pilot study, we wanted to capture the former primarily. Drawing a comparison with financial performance, the former is related to the internal rate of return of a specific investment, while the latter could be related to the return on assets a firm is delivering. Second, given the complexity inherent in impact measurement, we prioritized a smaller set of criteria that would reflect the ability of investors to conduct impact reporting and impact performance measurement. Third, the choice of our proposed select set of criteria was ultimately guided by the fact that we wanted to go beyond the mere objective of impact reporting to also enable investors to conduct impact performance analysis. Note that the link to an underlying ToC is a necessary condition for both reporting and performance, but while it may be sufficient for reporting, it is not sufficient for impact performance analysis.

To allow for the impact performance assessment of projects and impact investors over time, first, the metrics need to capture the intention behind impact at the onset of an investment decision/strategy. Second, we account for a universally admitted imperative namely, that impact metrics should be quantifiable. Indeed, while we recognize the systemic nature of impact and the importance of qualitative approaches, we would like to point to their inherent limitations in terms of comparing performance. Third, the metrics need to be easily computed (that implies good quality data availability). The first three criteria that we propose of intentionality, measurability, and feasibility, allow investors to report on the impact achieved by an investment but are not mutually sufficient to capture their impact performance. To reach the goal of impact performance measurement we need to ensure that two additional conditions are met: first, that organic growth is discounted for and that only the investment’s incremental impact be captured (incrementality) and second, that the metrics allow comparability across projects and investors over time. Importantly, in the context of this paper, only externalities associated with the investment that have been clearly identified and documented in the literature are recognized.

The above considerations, in addition to a comprehensive review of academic and practitioner literature on impact measurement approaches to be found in

Supplementary Materials S1, ultimately led us to propose a select set of five criteria that are listed and described below:

Intentionality—The metric captures a core effect(s) expected from the investment, as described in a ToC (which states the outputs, outcomes, and impact generated by investments in specific sectors or themes, including sizable and significant externalities). As a reference, the metric clearly addresses the following IMP dimensions of impact: What is the intended outcome? Who experiences it? How much of the outcome is experienced? [

7]

Measurability—The impact metric is quantitative and can be expressed in predefined units. The methodology (or formula) used to compute the metric should be explicitly disclosed and reproducible.

Feasibility—The data that is required to compute the metric is easily accessible and of good quality.

Incrementality—The metric measures the incremental effects of the investment being (partially or fully) funded. To account for the “pure” investment’s effects, controlling (i.e., discounting) for the organic growth of an existing or ongoing activity is necessary. Similarly to intentionality, the metric clearly addresses the following IMP dimensions of impact: What is the intended outcome? Who experiences it? How much of the outcome is experienced? [

7].

Comparability—The metric measures tangible outcomes and allows comparison among investors or investments. This implies that the metric: (a) complies with the measurability criterion; and (b) is normalized to account for the size of the investment and is time consistent.

In our analysis, we also found that other features of the metric could be considered by investors based on their specific needs: a. Prospectiveness: The metric documents the investment’s intended contribution towards achieving a specific goal; b. Compliance: The metrics are compatible with existing regulation; c. Standardization: The metric adheres to (a) specific globally accepted standard(s) and/or is/are recognized by standard setting bodies.

Our select set of advocated impact metrics selection criteria thus accounts for the need to consider intentionality, precise impact metrics, and good quality data, consistent with what investors have requested (see

Supplementary Materials S1). The fulfillment of these three criteria represents a necessary condition to conduct impact reporting, yet there is a need to go beyond these requirements by distinguishing between organic and investment-driven growth (incrementality) and focusing on metrics that foster comparability to move from impact reporting to impact performance measurement.

The novelty of our suggested criteria set lies in the following (for an account of academic and practitioner literature on impact frameworks and metrics, see

Supplementary Materials S1): Our five-criteria methodology (intentionality, measurability, feasibility, incrementality, and comparability) critically reviews and consolidates best practice in the practitioner and academic discourse on impact measurement approaches/frameworks. The criteria that practitioners base their standards on, i.e., HIPSO, the GIIN’s guidelines, and the OECD guidelines, emphasize data clarity, availability, and comparability, but lack the methodological foundation that underpins scholarly methods, while the cause-and-effect links (e.g., between an investment and its actual, realized impact) inherently remain difficult to trace or attribute. Meanwhile, academia offers a robust conceptual foundation (with the notions of intentionality, additionality, double materiality, prospectiveness) without accounting for the operational challenges in the measurability or the feasibility of the data that are faced by impact investors. Our proposed impact performance measurement approach is novel in that it reconciles both: it proposes an empirically validated, binary-scored set of criteria which put data quality and quantitative usability in the foreground (measurability, feasibility, comparability) and operationalize methodological rigor (intentionality, incrementality). Intentionality is distinctively operationalized rather than assumed, with each metric being cross-referenced against a ToC and evaluated through the IMP’s five dimensions of impact (What, Who, How Much, Contribution, Risk), thus transforming an abstract concept into a concrete measurable property. Measurability necessitates quantification through explicit mathematical functions and thus encodes what practitioner frameworks describe only qualitatively. Feasibility finetunes the discussion of data availability by, importantly, recognizing that investors do not form a homogenous set. Incrementality is of significant theoretical novelty because it reinterprets the concepts of additionality and attribution into a concrete test that controls for organic growth, aligns with the IMP’s Contribution dimension, and suggests detrending as a quantitative method for isolating incremental effects. Comparability is successful in addressing a lacuna in the literature by stipulating that all such metrics used for direct comparison fulfill three conditions: the metric must be quantitative in character; it needs to be normalized by the size of the investment; and it must remain consistent across time. In doing so, comparability imports the analytical discipline of financial performance measurement into the impact realm.

After identifying and explaining the set of criteria for benchmarking specific impact performance metrics, we selected a representative economic sector (credit finance) for our benchmarking pilot study.

2.2. Economic Sector Identification

To inform the selection of the economic sector for the pilot study, we examined which sectors are prioritized by impact investors (

Supplementary Materials S2 and S3). This was done by reviewing the publicly available reports and disclosures by the signatories of the Operating Principles for Impact Management (

Supplementary Materials S2 and S3).

Three methods of aggregation were subsequently applied in order to understand which sectors emerged as those most invested in by impact investors. The first method was based on a pure count of the number of times a particular sector was mentioned by an investor in its 2022 sustainability or impact report. The second approach applied a weight to the sector as listed by an investor based on the AUM quartile the investor belonged to. The third approach used the data on the sectoral investment allocation as a share of the total amount invested where available, to reveal priority sectors.

Across all aggregation methods, financial markets/credit finance emerged as the top investment sector. In aggregation method 1, agriculture/agribusiness/food and manufacturing and industry ranked second and third, respectively. Under aggregation method 2, manufacturing and industry took the second spot, followed by agriculture/agribusiness/food. In aggregation method 3, infrastructure and transport ranked as the second and third most invested sectors. Financial markets and credit finance, however, emerged as the top sector across all three aggregation methods, comprising investments spanning both debt and equity, as well as other financial services.

Under the broader heading of financial markets and credit finance, firms used various terms to categorize their impact sectors such as financial services, credit finance, financial inclusion, equity, debt finance, private equity, and microfinance. Upon further scrutiny, several of these terms related to credit, therefore we decided to focus on credit finance as the pilot sector to be investigated in our study.

2.3. Describing a Theory of Change for the Credit Finance Sector

Before delving into a ToC for the credit finance sector, we provide a brief context about what a ToC is, how it is developed, and how it underlies impact measurement. According to the United Nations Development Group, a Theory of Change (ToC) is defined as “

a method that explains how a given intervention, or set of interventions, is expected to lead to specific development change, drawing on causal analysis based on available evidence” and includes “

…assumptions underpinning the theory of how change happens, and major risks that may affect it” as well as “

…partners and actors who will be most relevant for achieving each result” [

8] (pp. 4–5). Similar definitions have been articulated by the GIIN, Theory of Change, and Organizational Research Services Impact (ORS Impact) [

9,

10,

11], among others. In short, a ToC provides the rationale underlying how a specific intervention generates change, in the form of intermediate outcomes and contribution to broader impacts. It is worth mentioning that another related tool, which shares a similar purpose with the ToC, is the Logical Framework (or LogFrame).

The process for developing a ToC begins with the identification of the intended long-term goal of the program or intervention (or ultimate expected impact), and then considers the conditions (and chains of pre-conditions) that need to be in place to reach such intended goal. In addition to contextual pre-conditions, others are described as either outputs or outcomes. While outputs are the products, goods or services resulting from a specific intervention, outcomes are related to the change in well-being experienced by different stakeholders (people, organizations, and the environment) resulting from the intervention and the outputs it produces. Definitions of outcomes and impacts are provided by the Impact Management Project [

12]. Ideally, all identified outputs and outcomes will be accompanied by an indicator to assess success in meeting such preconditions. Defining such indicators, collecting relevant data and evidence to produce these and any further analysis—through pre-post comparisons all the way to quantitative evaluative methods such as difference-in-difference and randomized control trials (RCT)—is the core of what is called impact measurement. This is why the formulation of a ToC underlies the design and structure of impact measurement and monitoring systems.

We now describe a brief ToC for credit finance in the context of impact investing. The goal of impact investments to increase credit finance is to support economic growth, and in many cases to do so while expanding the base of individuals and firms benefiting from such growth. There is ample evidence and theory in the literature showing that credit finance allows individuals to increase their well-being—either through consumption smoothing, pursuing business opportunities, or improving their skill set to achieve higher wages—and/or to support the growth of firms—by expanding their production capacity as well as allowing them to operate more efficiently and become more productive. To achieve this impact, on the one hand, individuals receiving credit make rational and responsible decisions about their consumption or education, upskilling or business investments. Similarly, firms receiving financing need to make appropriate decisions on the use of the financing to grow their business. At this level, outcomes would be measured by increases in income and welfare for targeted groups of individuals and sales, assets, job creation, and productivity growth by targeted firms. For these outcomes to occur, the economy needs to provide some level of opportunities for individuals (on entrepreneurship and employment) and an adequate business environment (including macroeconomic stability and regulations) for firms to operate. In addition, for these individuals and firms to access credit, the appropriate financial infrastructure needs to be in place (in the form of credit bureaus and transactional systems) and financial intermediaries need to have adequate capacity and systems (e.g., credit rating systems, loan officers skills, network and infrastructure to reach different groups of individuals and firms) to allocate increasing volumes of credit to those individuals and firms likely to succeed with their objectives. At this level, the measurement would focus on outputs related to the numbers and volumes of credit to targeted groups of individuals and firms by the specific financial intermediary(ies) that received the impact investment. This could be complemented by non-performing loan indicators to assess the quality of internal credit allocation systems. The inputs provided by investors to financial intermediaries to produce such outputs take the form of different financing instruments (e.g., equity investments, loans or credit lines, risk-sharing facilities, guarantees) as well as technical assistance. This ToC description for credit finance is broadly in line with ToC examples on SME financing and financial inclusion from different organizations (e.g., Calvert Impact, EIB, and IFC [

13,

14,

15]).

In summary, by investing in credit finance, impact investors expect to generate additional economic growth—likely with a focus on a specific group of individuals (e.g., young individuals, women, other vulnerable groups) or firms (e.g., SMEs, women-led businesses, or smallholder farmers), or by the use of borrowed funds (e.g., education loans for individuals or climate finance for firms)—by supporting the credit expansion of investee financial institution(s) (FIs) they are funding. Given that measuring outcomes at the borrowing beneficiary level is not feasible, impact performance indicators should focus on how FIs’ targeted credit line portfolios evolve following their impact investment.

2.4. Identifying Key Impact Metrics Used in the Credit Finance Sector

In

Section 2.2, we articulated why credit finance is a “unique” sector, stressing the fact that information on the sectoral allocation of investments labelled as “impact” investments was not always available whereas priority sectors for impact investors were not labelled as “impact” investments. Credit finance is deemed a “special” sector for another reason. Credit finance focuses on managing capital, facilitating transactions, and channeling funds to productive sectors that allow these to produce goods and services in the real economy. Credit finance, as a sector, acts as an intermediary and supports economic activity by providing liquidity and credit. In contrast, the real economy produces tangible goods and services. Consequently, credit finance is designed to be able to capture indirect effects, while real economy sectors are more conducive for the attribution of direct effects.

After selecting our pilot sector, we identified the impact metrics already used by impact investors who allocate funds in the credit finance sector as well as metrics that are proposed in the academic literature for credit finance. For that purpose, we first created a list of 177 metrics and KPIs which are publicly available and used by practitioners in the financial markets and institutions category. The impact metrics originated from investors who had signed the Operating Principles for Impact Management (OPIM) as of February 1st, 2023. In a second stage, we focused on HIPSO and IRIS+ impact metrics as these indicators are proposed by the two networks, the HIPSO and the GIIN, encompassing the largest groups of impact investors and as there is wide consensus for their usage. We, therefore, selected 39 HIPSO/IRIS+ metrics [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42] that represent widely available impact metrics that specifically apply to the credit finance sector. These 39 impact metrics comprised the set of practitioners’ metrics that we then benchmarked in our pilot study.

We also reviewed 220 academic articles, exclusively focusing on empirical and survey papers. We noted that there is a scarcity of academic papers directly discussing impact metrics and indicators. This initial screening, nevertheless, led to a total inventory of 266 academic metrics and KPIs. These impact metrics/KPIs, however, covered all economics sectors, thus we narrowed our search to the credit finance sector by selecting those impact metrics that were mentioned in academic papers whose keywords and/or JEL classifications apply to the credit finance sector. Out of the initial set of 266 metrics, we ended up with 45 academic metrics [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62] that were relevant for the credit finance sector. Thus, in total, the benchmarking study was performed on 84 impact metrics among which 39 stem from practice [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42] and 45 from academia [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62] (see

Supplementary Materials S4 for details). It is worth noting that externalities are not accounted for by most metrics we investigated. This is understandable, as in the evolution the industry would focus first on direct effects that are usually observable and measurable, while indirect effects are not necessarily observable and would require estimation methodologies. Since many of these externalities can be proxied with some direct effect/observable output or outcome measure, it might be better to focus the industry’s agenda on furthering the convergence on impact reporting and create one on impact performance measurement.

For this assessment, we constructed a systematic benchmarking protocol based on our five established criteria. Each metric underwent an independent review by the three co-authors and two research assistants through a two-round evaluation procedure. In the initial iteration, each reviewer mapped each metric against the five criteria and employed a binary score (1 for match, 0 for non-match) based on definitions presented in

Section 2.1. This step addressed the intrinsic logic of every metric, prioritizing its theoretical basis, methodological clarity, data needs, and comparability potential. The second iteration aggregated all the individual evaluations and compared them systematically in order to pinpoint inconsistencies. Contrasting scores were then collectively investigated in order for the team to engage in debate about the cause of disagreement, i.e., varying perceptions of ToC fit, availability of data, or normalization assumptions. This process yielded an overall consensus score for each metric-criterion combination. This method enabled the team to build iterative consensus-based benchmarking results so that final decisions were anchored in an open and robust evaluation process. For future applications, calculating an inter-rater reliability statistic, such as a Kappa coefficient, could enable one to quantify the level of agreement among evaluators in the first stage and thus further enhance the objectivity of the benchmarking analysis in the second stage.

More specifically, regarding intentionality, we verified whether a particular impact metric actually captured a core effect induced by the investment, according to the pathways of the simplified ToC for the sector described in

Section 2.3, and whether it touched on the IMP dimensions of impact in an explicit manner. For measurability, we checked whether a metric was quantitative, expressed in pre-defined units, and supported by an explicit, reproducible formula or approach. In terms of feasibility, we evaluated the data availability and quality needed to calculate each metric, taking into account whether representative impact investors could obtain the respective information. While DFIs tend to release standardized information, other impact investors might rely on granular or proprietary data that are not available for public access, which had an effect on our scoring. For incrementality, we conducted the test to ascertain whether the metric was measuring incremental effects of an investment once organic growth was controlled for. Lastly, for comparability, we ascertained whether the metric was measuring tangible outcomes and was scalable such that comparisons could be made across investors, investment sizes, and over time. This criterion-specific two-step procedure enhanced inter-rater reliability while ensuring a rigorous, transparent, and replicable measure quality assessment. Following this process, in

Section 4 (Discussion), we present concrete examples in four metrics that met all five requirements using a detrending approach (see

Supplementary Materials S5 for more details) (

Table 1).

3. Results

This benchmarking case study conducted on our set of academic and practitioners’ metrics, led to several interesting conclusions. We start by making two general observations. First, we found that there is a mismatch between the set of impact metrics proposed in the academic and practitioners’ literature. Indeed, out of the total sample of 84 metrics, only 7 matched closely, 20 matched to some degree, and 57 were totally distinct. This, in some sense, is good news as it suggests that there is complementarity rather than substitutability among the available impact metrics provided by academics and practitioners and that there might be synergies in having both communities work together on addressing impact measurement challenges.

Second, we encountered a challenge around impact metrics availability: we could identify a large number of financial metrics to assess the financial performance in the credit finance sector but were left with a relatively small pool of 84 eligible impact metrics to run our benchmarking analysis on. Going forward, it would be interesting to examine if this finding is common across all economic sectors or specific to the benchmarked credit finance sector.

We now turn to the interpretation of the main results of our benchmarking study which are summarized in the figure below.

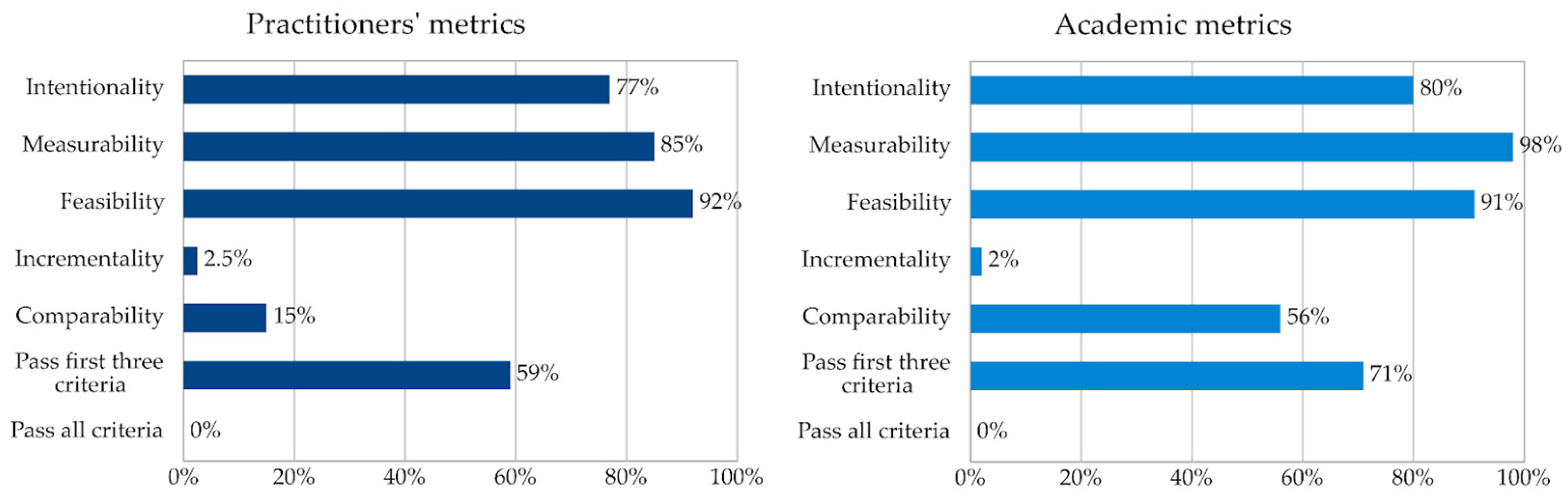

Figure 1 shows, for both sets of metrics, the percentage of metrics that fulfilled the first three as well as all five benchmarking criteria. Not surprisingly, a large fraction of the analyzed metrics (59% and 71% for the practitioners’ and academic metrics, respectively) passes the bar of the three first benchmarking criteria of intentionality, measurability, and feasibility. These are precisely the criteria that impact investors need to satisfy for impact reporting purposes and it leads us to assert that investors are ready to report on credit finance-generated impact but could benefit in this respect as well from adopting metrics proposed by academia. However, and more surprisingly, the same figure suggests that there is no single metric, whether from academia or from practice, that passes the test of all the five criteria that collectively are necessary for impact performance assessment.

This granular analysis clearly shows why all metrics fail to pass the bar of meeting all five criteria. This is mainly because most metrics—whether advocated by practitioners or by academia—do a poor job at meeting the comparability and especially the incrementality criterion, both of which are essential for impact performance measurement. It is worth noting that 76.92% (80%) of the practitioners’ (academic) metrics satisfy the intentionality criterion that is the core link to the underlying ToC. Furthermore, academic metrics do a better job at fostering comparability compared to practitioners’ metrics (55.6% versus 15.4%) probably because a higher percentage of these metrics (98% versus 85%) are deemed measurable and because academics are more aware of the necessity to normalize metrics in order to foster comparability of the impact achieved by investments of various sizes, for instance. This large discrepancy is also probably because practitioner metrics are designed mainly for investee/portfolio level reporting and accountability, and are hence usually absolute, stock/flow counts (e.g., number or value of loans outstanding) depended on every investor’s idiosyncratic size, scope, and reporting period, without mandatory normalization by investment size. Denominators (per dollar invested, per borrower, per total assets) and baseline conventions are often not spelled out or differ from investor to investor, which compromises cross-investor comparability. In contrast, academic metrics are employed more commonly for panel or cross-section comparison and hence tend to (i) have normalized forms (growth rates, proportions, ratios, rates), and (ii) showcase time consistency (annualized change on a common horizon). This systematic application of normalization and common measurement “windows” generates a higher proportion of metrics that satisfy our comparability criterion in the academic set. However, when it comes to incrementality, less than 3% of the metrics—whether from academia or from practitioners—comply with this criterion. This is quite a disappointing finding as it suggests that more than 97% of the metrics do not control for the organic growth that would have been achieved without the project or investment that is being considered. Thus, if the credit finance sector is considered as a growing (shrinking) sector this would mean that impact investors overall would have a tendency to overestimate (underestimate) their investment’s effective impact.

This study goes beyond identifying gaps in existing impact measurement approaches, by proposing a new set of impact performance metrics (Discussion) designed specifically for credit finance. The impact performance metrics (which are defined and detailed in

Supplementary Materials S5) move the impact measurement debate towards the direction of robust financial performance-like methods by capturing the incremental impact effects of investments, adjusted for underlying economic trends. The goal is thus to allow a clearer distinction between organic portfolio growth and growth attributable to impact investments. The analysis presented in

Supplementary Materials S1 also reinforces the need for impact performance metrics. While investors and standard-setters increasingly emphasize reliability, comparability, and feasibility, few existing frameworks provide tools that can measure investment efficiency or incremental impact in a comparable way, a point that is further highlighted in

Supplementary Materials S1. Our proposed impact performance metrics for the credit finance sector aim to bridge this gap by offering a structured, transparent approach to assessing impact performance rather than merely outcome reporting.

Through the analysis of these combined findings, we can thus make three important recommendations:

Investors should use impact metrics that distinguish between organic and investment-driven growth.

Investors should use normalized metrics.

The impact investment community would benefit from working closer with academia, to learn about academic metrics that foster comparability.

4. Discussion

As a by-product of this study, we next ask how to construct impact metrics that would allow impact investors to conduct impact performance measurement using the five criteria proposed for our chosen sector, credit finance. As shown in the previous section, the intentionality, measurability, and feasibility (through data quality and availability) criteria seem to already be mainstream in the impact measurement practices of investors and academics. Thus, we focus on the underlying requirements to comply with the two last criteria of comparability and incrementality.

First, regarding comparability, the main challenge we encountered with the evaluated metrics was that most of these metrics measure outcomes at the institution level in absolute terms, which in most cases are driven by the size of the underlying financial institution’s overall operation. For example, the value of loans outstanding observed for financial institutions at any given point in time are driven by the financial institutions’ balance sheet size, and are, therefore, not comparable. Similarly, metrics measured at the investment level in absolute terms will depend on the size of the overall investment associated with the measured outcome. Therefore, adjusting metrics to comply with comparability—for impact performance purposes, will in general involve normalizing metrics to discount their dependency on the size of investees’ operations or investment programs underlying gross absolute outcomes. These normalizations may include the calculation of growth rates, changes in percentage shares, and when appropriate, controlling for the dollar size of the investments undertaken by investee firms to generate the measured outcome. In all these cases, it is important that, in addition, these changes are measured over a common time period, to preserve comparability (e.g., annual growth rates, change in percentage shares over N years). These normalizations seem to be a relatively straightforward and doable task. In fact, our findings show that more than half of the impact metrics advocated by academics are measurable and normalized and thus foster comparability.

Second, as the results from our evaluation show, complying with incrementality seems to be the most challenging of all the five criteria proposed. The underlying factors to comply with incrementality are to (i) measure changes in outcomes driven by the investment, and (ii) discount the organic growth that would have occurred in the absence of the investment. Collecting impact data over time to measure changes in outcomes is the ultimate objective of many of the evaluated metrics. Therefore, it should be straightforward to identify impact performance indicators based on existing metrics measuring absolute outcomes at a point in time. The second factor, discounting organic growth certainly requires more effort to implement, but it is critical to impact performance measurement. It is core to complying with Principle 4 of the Operating Principles for Impact Management, which requires impact investors to “

…assess, in advance and, where possible, quantify the concrete, positive impact potential deriving from the investment” [

63]; and is also in line with the Evaluation Cooperation Group’s Good Practices, which implies that impact evaluation “

focuses on quantifying the incremental contribution to results that is attributable to the intervention” (Evaluation Cooperation Group) [

64]. The difficulty in complying with this criterion is that it is hard for investors to establish credible counterfactuals for the organic growth of their investee firms. Investors could nevertheless circumvent this problem and control for organic growth by adopting agreed detrended (or demeaned) metrics, or other simplified methodologies aimed at proxying (counterfactual) organic growth. Detrended metrics for instance, proxy organic growth through the average growth achieved by the firm over a given past horizon (e.g., one to three, or three to five years), and subtract it from the total growth realized (or expected to be realized) during a given reporting period to account for incrementality in their selected impact metrics. One should however be aware of the fact that detrending using a sufficiently long time period to be representative works well in normal times but might be difficult to implement during periods of rapid economic or regulatory change, such as during financial crises. In such cases, one could perhaps use a detrending approach which relies on a mean computed with exponentially declining weights. Despite its limitations, we consider detrending to be a necessary step—even if imprecise at times—to discount the organic growth of the impact performance metrics. Another alternative, provided long enough time series data is available, would be to use standardized metrics that remove the average long-term growth and divide by its standard deviation.

Third, it is worth noting that impact performance metrics complying with all criteria, including comparability and incrementality, are already used by selected DFIs as well as by some impact investors, but unfortunately these are not publicly available, nor part of broad harmonization or standardization efforts. Furthermore, the Compass methodology launched by the GIIN in 2021 [

65] is an effort to move the industry towards impact performance comparability. It focuses on three types of analytical figures: scale, pace, and efficiency. While scale indicators measure changes in outcomes in absolute terms, pace indicators measure annualized changes in outcomes in percentage terms, both relative to an observable baseline. As discussed before, while useful for contextualization and reporting purposes, these types of indicators would not comply with all the criteria proposed in this paper for impact performance measurement. Scale indicators are not comparable across investments or investors as they depend on the size of investees’ operations or underlying investment volumes, while both scale and pace indicators do not fully comply with the incrementality criterion as they do not necessarily measure the incremental outcomes attributable to the specific investment being (partially or fully) funded by the impact investor, after discounting organic growth. The COMPASS methodology seems to be agnostic about measuring outcomes for entire investee firms’ operations or specific investment programs following a use of proceeds approach. As discussed before the latter is in line with what is expected from impact investors following the Operating Principles for Impact Management (Principle 4) [

63], while the former could be used in special cases where it is not possible to delineate specific use of proceeds of the impact investment (e.g., equity investments or investments that are part of a corporate finance investment program). On the other hand, efficiency indicators (e.g., change in investment-generated outcomes per dollar invested) would be the closest to complying with all of our five criteria, provided that organic growth is discounted from the total growth in outcomes. It is worth mentioning that the concept of organic growth and of a counterfactual are included in the COMPASS methodology document. However, when using the Compass approach to build financial inclusion benchmarks, the GIIN limited its analysis to scale and pace indicators, as “

…data do not allow for the analysis of impact Efficiency, or the amount of impact generated per dollar invested” [

66]. These challenges are consistent with the findings of this study on the availability and use of appropriate metrics that impact investors could follow and report on, for impact performance measurement purposes.

Fourth, having identified the key adjustments required for impact metrics to comply with the impact performance measurement criteria, we turn to the question of how to construct appropriate impact performance metrics for credit finance. Given the challenges that we have documented in this study related to the proliferation of impact metrics in the market and the lack of appropriate impact performance measurement metrics for credit finance, we want to contribute to the current debate and practice by proposing a few metrics that comply with the five criteria defined in this paper.

We thus propose, as fifth, the following streamlined set of impact performance metrics—each proposed impact metric’s exact formula (including the detrending) is described in

Supplementary Materials S5 that are all based on the credit finance theory of change discussed in

Section 2.3, most can be constructed using as a basis some of the metrics already collected by practitioners at different points in time and further allow us to capture the impact performance associated with impact investing in the credit finance sector in a robust way:

Detrended average annual growth rate in [SME, women-led business, smallholder farmers, low-income or vulnerable population groups, environmental or climate finance; others] loan portfolios; it is detrended by [GDP growth, total credit growth, others…].

Detrended average annual growth rate in the number of [SME, women-led business, smallholder farmers, low-income or vulnerable population groups, environmental or climate finance; others] loans. This indicator provides assurance that the growth in portfolio shares and volume of loans is being accompanied by an increase in the number of ultimate beneficiaries. It is worth noting that the detrending suggested for the second and third indicators is from the FIs own historical data. For these indicators detrending by a macro or sector trend as for the first indicator doesn’t apply, as these are changes in the composition and allocation of credit, rather than in pure growth rates (please refer to

Supplementary Materials S5).

Detrended total change in the share of [SME, women-led business, smallholder farmers, low-income or vulnerable population groups, environmental or climate finance; others] loans to total loans.

Ratio of detrended change in [SME, women-led business, smallholder farmers, low-income or vulnerable population groups, environmental or climate finance; others] loan portfolio to Impact Investor’s funding. This indicator measures the incremental volume of loans provided by the investee FI, beyond the trend in loan volumes to target beneficiaries/themes, directly funded by the impact investor. It is expressed in the form of a multiplier.

As an illustration of the practical application of the five-criteria approach, we analyzed a set of impact performance metrics for women-led businesses in credit finance portfolios (see

Supplementary Materials S5. The first indicator, the detrended average annual growth rate in loans to women-led businesses, captures whether the portfolio’s expansion into the segment exceeds macro or sectoral trends such as GDP or cumulative credit growth that drive financial institutions’ portfolio growth, thus separating the incremental effect of the investment in improving access to finance for women. The second and third metrics, the detrended average annual growth rate in the number of loans to women-led businesses and the detrended total change in the share of loans to women-led businesses relative to total loans, ensure that observed portfolio growth is associated with an increase in the number of ultimate women borrowers and a reallocation of credit toward women-led enterprises. Detrending for these is dependent on the financial institution’s own historical data rather than macro-level benchmarks, because the associated changes represent portfolio composition rather than pure growth. Finally, the ratio of detrended change in loans to women-led businesses to the amount of impact investor funding measures the incremental loan volume generated per unit of investment, serving as a multiplier of effectiveness. Individually, these indicators satisfy intentionality by associating observed changes to a ToC focused on promoting gender equity through access to finance; measurability by utilizing quantitative and replicable data; feasibility by using regularly collected, sex-disaggregated portfolio data; incrementality through detrending that discounts organic growth and isolates the investment’s contribution; and comparability for instance by accounting for growth rates or by normalizing with respect to overall loans size or to investor funding.

These indicators all capture the main intent that most impact investors have when investing to expand access to credit finance through financial institutions, along the lines of the brief ToC discussion above. Some DFIs and impact investors also use indicators about improvement in tenors or less restrictive conditions on collateral requirements. However, these ultimately will be reflected indirectly in higher volumes of loans outstanding. These indicators can be measured by all kinds of impact investors as they are based on information that is usually available from financial institutions, while also complying with the incrementality and comparability criteria proposed in this paper. Furthermore, these indicators will allow investors to close the gap between standard financial analysis (i.e., estimation and monitoring of financial returns and risk-adjusted returns on their investments) and impact performance measurement.

There is great interest from many impact investors in indicators that reflect outcomes at the ultimate beneficiary level. These include, for example, job creation related to additional borrowing by MSMEs, improvements in productivity and income-driven by expanded access to financing to farmers, and emissions reduction effects of climate financing targeted to firms. However, as discussed before, these data would be too costly to gather, and thus violate the feasibility criterion. Therefore, in practice, such indicators usually imply estimations built on the expected growth in the number and volumes of loans, for which there are different methodologies that DFIs and impact investors can use. A few investors, like the IFC, go a step beyond this and try to establish expectations of broader market effects, which in general go beyond the control of the investee FI, and are therefore outside the scope of the proposed impact performance measurement in this paper. The recommendation is therefore to limit the scope of impact performance measurement for credit finance to a select set of indicators based on data that can be collected from investee FIs. Investors performing estimations of outcomes at the beneficiary level should continue working towards converging around robust methodologies to report on such externalities and expected benefits, and to use properly designed impact evaluation metrics to document evidence on these effects.

The applicability of this proposed approach was illustrated through this pilot case study in the credit finance sector and can be extended across SDG themes and sectors, for example in jobs, gender, and climate as well as manufacturing, energy, and agriculture. Through this pilot case study, we have provided a detailed roadmap through the establishment of an impact performance measurement approach, the cataloguing of impact metrics per theme/sector from academic and practitioner sources, a robust benchmarking exercise, and the convergence around metrics that meet the criteria of intentionality, measurability, feasibility (all three are pertinent for reporting purposes) as well as comparability and incrementality (all five are necessary for impact performance measurement).

All in all, the impact investing industry is confronted with the necessity to construct more technical metrics to appropriately measure impact performance and to facilitate their disclosure by public means. This is a necessary condition if the industry wants to be able to conduct impact performance measurement in parallel to financial performance measurement and empower investors with proper corrective measures to build credible benchmarks to make better-informed decisions for their investments. More importantly, it is a necessary condition to attract larger pools of capital that scale the industry’s critically needed contribution to meeting the SDGs.

5. Conclusions

Summarizing our main findings, we note the discrepancy that exists between a large set of robust metrics to assess financial performance and the scarcity of proper impact performance metrics. Moreover, it seems that academics and practitioners do not align in terms of the impact metrics that they propose, and that the latter would gain from collaborating with academics to develop more suitable impact metrics that, at least, capture comparability.

As a result of our benchmarking exercise for the credit finance sector, we note that while more than half of the metrics fare well in terms of the first three criteria—intentionality, measurability, and feasibility—that are necessary for impact reporting, there is still substantial progress to be made within the impact investing industry to develop impact performance measurement metrics that capture the last two criteria, namely comparability and especially incrementality. We suggested learning from academia when it comes to using normalization and thus complying with comparability and we further presented a pragmatic approach to control for organic growth and thus account for incrementality to enable investors to undertake impact performance measurement. Finally, we propose a streamlined theory of change (ToC) for the credit finance sector based on which we advocate parsimony in the number of impact metrics to be used by impact investors to track the performance of their targeted funding, and we provide concrete examples of impact performance metrics that could be used to comply with all the proposed criteria as well as with the proposed ToC for the credit finance sector.

However, to generalize our findings and draw firm conclusions, it is necessary to expand on our study by enlarging its sectoral reach (agriculture, manufacturing, health, energy, and others) as well as its thematic focus (climate, nature, gender diversity, poverty reduction and other). In parallel, it is necessary to establish a dialogue with impact and aligned investors as well as impact investing standard setters about our advocated set of impact performance metrics selection criteria and sector/theme-specific impact performance metrics recommendations.

Our study, and to some extent similar studies in this field, also bears some limitations, which present an opportunity for further research efforts: First, with impact investing remaining a relatively new investment strategy underpinned by limited academic research, the data collection for our study was challenging in many aspects. There were very few academic articles that proposed a methodology that would either put forward a set of criteria or a selection method for computing relevant impact metrics, adjusted for sectoral and dimensional needs. In addition, extracting the metrics and KPIs both from the academic and the practitioner literature posed an additional challenge, in that the definitions of the metrics, where they existed, remained, in many instances qualitative and too descriptive, thus lacking the fine-tuning needed to evaluate their compliance with the proposed set of criteria.

Second, our results may lack statistical power as they are based on a rather limited universe of 84 impact metrics. This challenge might be sector-specific and can be mitigated as we enlarge the scope to other sectors, impact dimensions, and/or more comprehensive sets of metrics (which may include those used internally by impact investors though not publicly available).

Third, while we looked for ways to capture quantitatively rigorous metrics (in their definition and expression), we recognize that there is also value in accounting for the qualitative elements thereof. For example, regarding SDG8, i.e., decent work and economic growth, HIPSO’s TA-05 metric is about “female direct jobs supported (operations and maintenance)” [

67] including a detailed description of this definition. However, there are two issues. Knowing from the data whether the creation of female jobs also means that the work conditions are decent is hard to establish. Furthermore, establishing a link between this metric or other relevant metrics with the SDG end goal (impact) which is to “by 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value” [

68] will remain challenging. This latter remark extends to most qualitative metrics.

Fourth, our research will remain focused on three key objectives: determining if the intended impact—based on an underlying theory of change for the select sector—is achieved, evaluating whether the collected data effectively enables us to identify the anticipated outputs, and recommending metrics that allow impact investing to scale. These guiding principles will continue to shape our approach. Given that we have limited data on the end beneficiaries of credit finance, as detailed information is scarce, it is essential to remain aligned with what can realistically be measured.

Our goal in this paper was to strengthen the impact performance measurement process by presenting a select number of coherent impact performance metrics for sectors and themes (e.g., through a pilot study for the credit finance sector. For the latter, we proposed four coherent impact performance metrics that we hope will be helpful to improve the decision-making and impact performance assessment of impact investors and investees, both in the developed and in the developing world. While existing standards usually focus on impact reporting metrics, our proposed work is to leverage and complement existing reporting metrics to develop a set of coherent impact performance metrics that allow for comparability. This would bring the assessment of impact performance measurement at par with assessments of financial performance in the industry and more importantly, it would enable us to increase the capital allocation efficiency that is desperately needed to fulfill the SDGs.