1. Introduction

Water is an indispensable natural resource for human life and an essential economic resource for the production and sustenance of enterprises. China is a water-scarce country with low water resources carrying capacity and enterprises [

1]. As a significant consumer of water resources, the quantity of wastewater discharged is increasing, as is the complexity of the treatment process. According to the annual “China Water Resources Bulletin” in 2021, the total water consumption of the country was 592.02 billion m

3, of which 1049.6 billion accounted for 17.7% of the industrial water, and compared with 2020, the industrial water consumption had increased by 1.92 billion m

3 (

Figure 1 shows the status of China’s industrial wastewater discharges). The prevailing situation of water resource scarcity and inequitable allocation has become a significant impediment to the sustainable advancement of water resource management [

2]. As early as the 1970s, due to public dissatisfaction with the adverse impacts of enterprises on the ecological environment, the United States, the Netherlands, and Canada introduced corresponding laws and regulations to improve the water audit system [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Subsequently, in 2013, the Working Group on Environmental Auditing of International Organisations (WGEA) issued the Methodology for Water Audits of International Organisations of Supreme Audit Institutions (SAIs), highlighting the need for the application of water audits by national audit institutions due to the current situation of water scarcity and stress [

7]. As a result, in 2009, the city of Suzhou, China, took the lead in formally launching corporate water audits nationwide. Subsequently, the governments of Jiangsu Province, Shanghai Municipality, Shandong Province, Beijing Municipality, and Hebei Province, in conjunction with the water resources departments, have issued local rules and regulations, which have further refined the provisions related to corporate water use audits at the legal level, in order to enhance their standardization and operability in practice (

Table 1). The Chinese government has made it clear that “comprehensively improving water safety and security capacity is a major strategic programme”, and corporate water audits are one of the key developments in realizing China’s major water safety strategy. In order to guide provincial water administrative authorities to actively take effective measures to broaden investment and financing channels in the field of water conservation, to absorb the investment of idle capital from the society, and to provide cash flow support for enterprises, the Ministry of Water Resources of China vigorously promoted the “Water Conservation Loan” financial service in February 2023, which is aimed at providing effective incentives to enterprises with outstanding water resource optimization and management. The water use audit system helps enterprises to avoid water waste and ecological pollution by supervising their water safety, by solving and optimizing their problems of water abstraction, water use, water conservation, water consumption, and water withdrawal (discharge), and by better helping them to “find out the bottom of the barrel, and prescribe the right medicine”, so as to improve the management of water audits and deepen the sustainable development of their production activities [

8,

9].

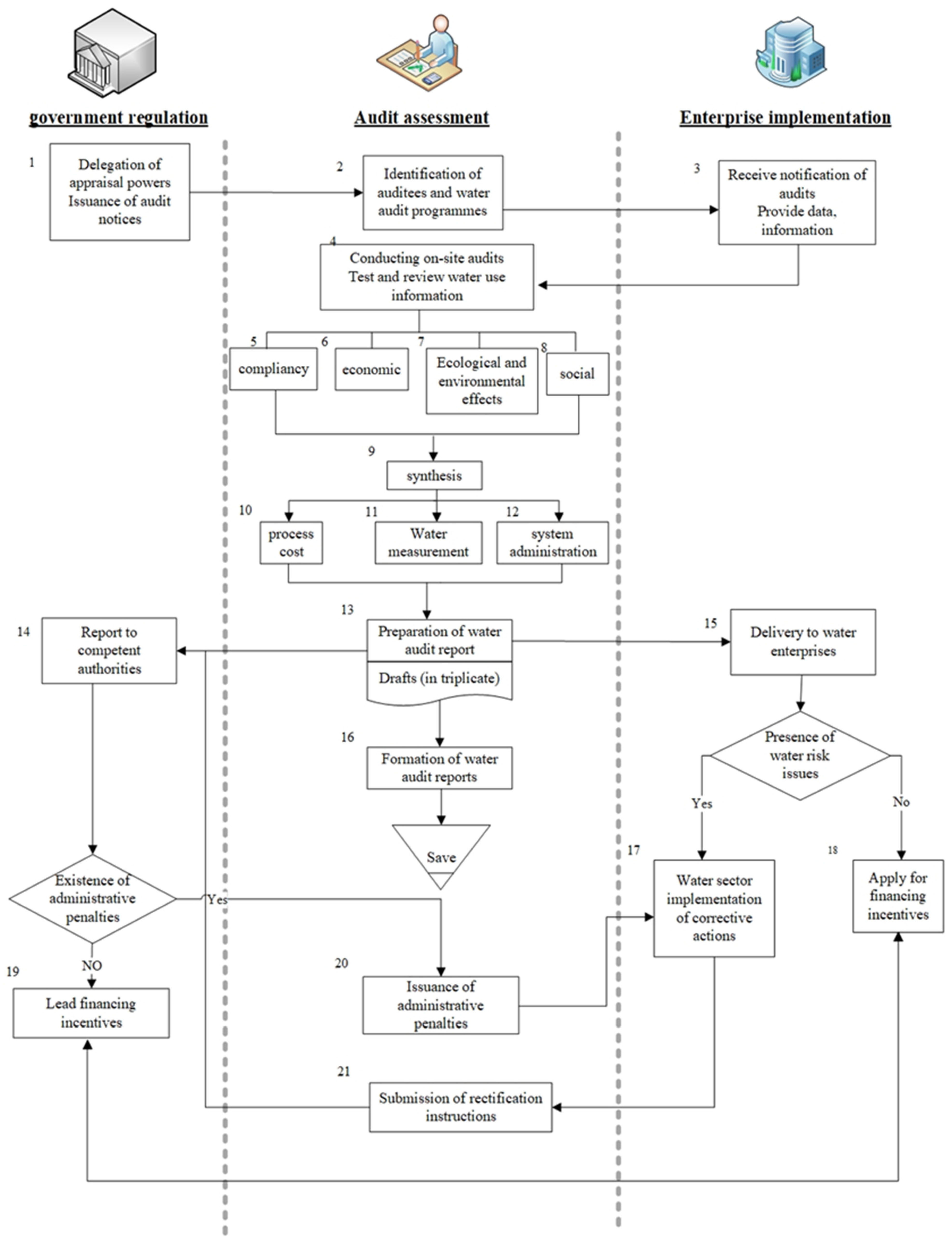

The objective of the water use audit system is to enhance water use efficiency, reduce water wastage and encourage the sustainable use and conservation of water resources by auditing and regulating the use of water resources in enterprises. The Corporate Water Audit Service Framework is based on the establishment of appropriate regulatory bodies and management mechanisms under the water audit system to promote water use efficiency and the sustainable use of water resources. Within this framework, the water use audit process plays a pivotal role, comprising a series of steps designed to ensure that the audit is comprehensive, accurate, and actionable (

Figure 2). The evaluation of water use audits employs four dimensions: compliance, economy, ecological and environmental impacts, and society. Compliance refers to the necessity for enterprises to comply with national laws and regulations, as well as other policy documents, industry standards, water-saving technologies, and water technology. This is performed in order to avoid the negative effects that could result from penalty costs and production costs. The concept of economy is defined as the value of indicators, such as quantitative and qualitative indicators, for testing the composite enterprise’s water use and water conservation. These indicators can be used to help enterprises achieve the greatest possible profits while consuming the least amounts of resources. The ecological impact of wastewater discharges on the water ecology and water environment is a key consideration for enterprises, as it helps them to avoid discharges that could harm drinking water sources, contaminate soil, and contribute to the eutrophication of water bodies. Social factors, such as a statistical survey of the enterprise’s satisfaction with the surrounding public and the sustainability of its own water management, are also important. This helps enterprises to better promote their commitment to, and fulfillment of, their social responsibilities. By analyzing the corporate water audit process, it can be seen that the auditing body can gain a comprehensive understanding of the enterprise’s water use and put forward effective management recommendations. The government regulator can serve as a basis for formulating and implementing relevant policies and measures. At the same time, enterprises can also use this framework to improve water use efficiency, reduce resource waste, and achieve sustainable development. Consequently, the corporate water audit framework is of considerable significance and utility in enhancing water use efficiency and safeguarding water resources.

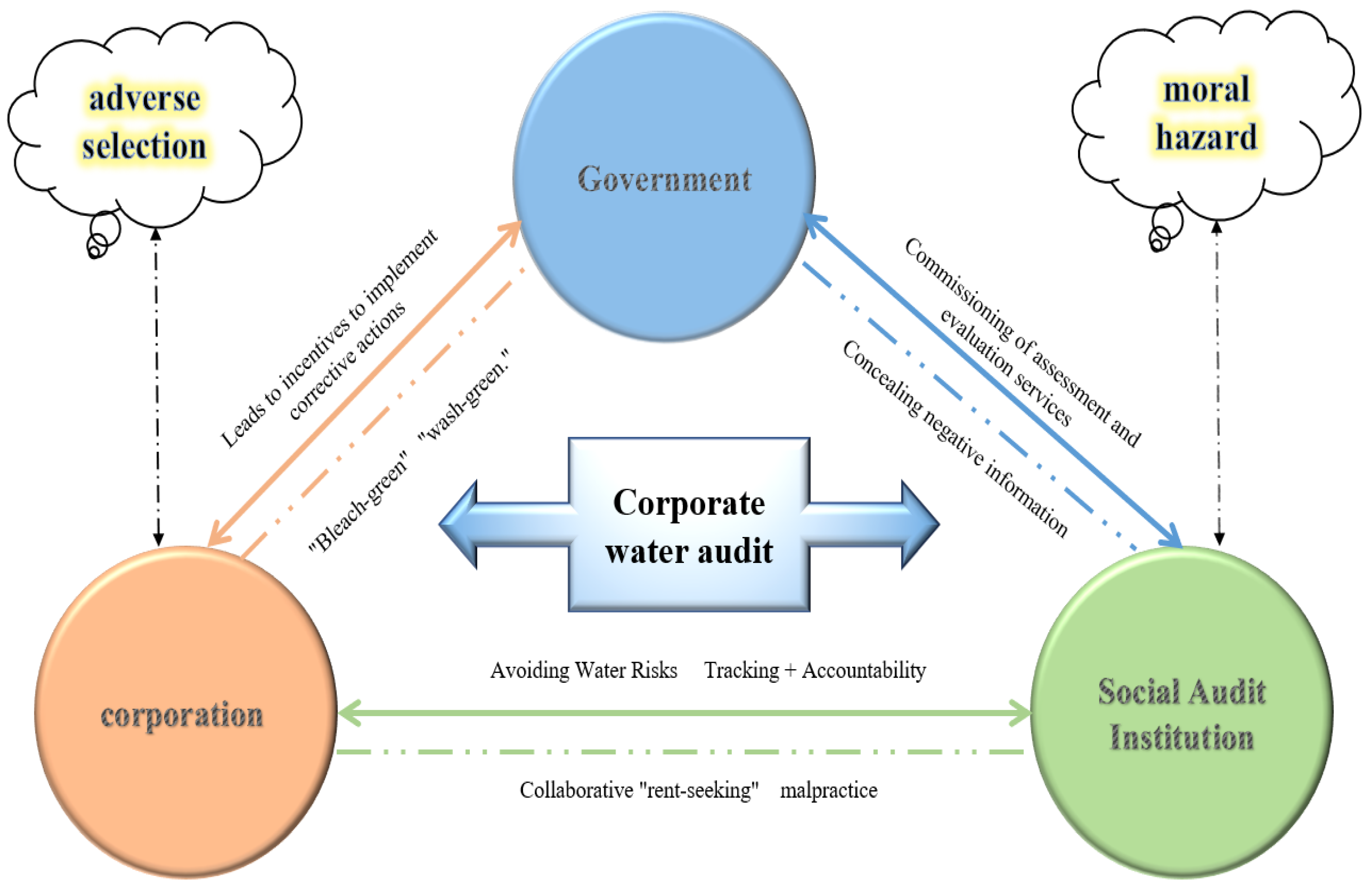

The phenomenon of information asymmetry is widespread and refers to instances when one party has an information advantage over the other, which is essentially an “imbalance” of information [

10]. Information asymmetry is created when information is inaccurately transmitted between the parties involved, resulting in distorted information. Thus, contrary to the original intent of the government in developing the water audit system, information asymmetry exists throughout the process of regulating the corporate water audit system. In order to enhance the impartiality and independence of supervision, the government delegates the right of annual assessment to the public (third-party auditing organization), and the third-party auditing organization performs the fiduciary responsibility of enterprise water use auditing and issues the auditing report. This enables the government to take the corresponding administrative penalties or to pursue the legal responsibility of ensuring that the enterprise complies with the regulations on the use of water and fulfills the social responsibility of environmental protection, and allows the formation of a system of power and responsibility of government supervision, social assessment, and implementation of the rectification of the enterprises from the top down [

11]. As can be seen, a clear contractual relationship is formed between the government, the third-party auditor, and the enterprise to ensure that the agent acts in accordance with the principal’s wishes and that reasonable safeguards are provided to both parties. However, in practice, between provincial water administrative authorities and third-party audit institutions there is a dynamic game between national and personal interests [

12], resulting in moral hazard; when the third-party auditor publishes the water audit report, it is difficult for the government to verify the accuracy and truthfulness of the results, while the auditor may take advantage of the loophole of information asymmetry [

13], make up false audit reports, or engage in reverse behavioral choices, such as “rent-seeking”, in conjunction with enterprises, in order to obtain preferential policy support for green financial services, or engage in “rent-seeking”, malpractice, and other adverse behavioral choices in conjunction with the enterprise [

11]. This ultimately puts audit firms in a predicament of unfavorable regulatory penalties and reputational damage (

Figure 3). Simultaneously, within the enterprise–water-audit framework, information asymmetry challenges pre- and post-event classification and trilateral interaction mapping, leading to pre-contractual adverse selection. Prior to contract signing, significant information gaps between transacting parties trigger market failure where “inferior entities drive out superior ones”. Specifically, the party with information superiority tends to conceal its true capabilities or operational status, leading the information-disadvantaged party to make decisions that fail to meet expectations or even result in losses, due to a lack of critical information. A post-contractual moral hazard emerges: after contract execution, the information-advantaged party exploits the difficulty of fully observing their actions to deviate from the contract’s original intent, engaging in opportunistic behavior. Their conduct sacrifices the interests of the information-disadvantaged party to pursue additional gains for themselves (

Table 2). This reveals the core hazards of information asymmetry: pre-contractual adverse selection triggers “bad money drives out good”, where compliant enterprises and high-quality audit institutions face marginalization due to higher costs, allowing non-compliant entities to dominate the market and exacerbate implementation deviations in water audit systems. Post-contractual moral hazard induces “contract failure”, leading to escalating government regulatory costs, inefficient incentive policies, persistent water waste and pollution issues among enterprises, and the diminished credibility of the audit system.

As a result, reforms related to corporate water auditing systems have been slow and less effective than expected. Some questions for reflection arise in the above context, then, such as how do the relationships between the three stakeholders—the government, businesses, and third-party auditors—interact with each other? Can the incentives promoted by the government solve the problem of information asymmetry that exists among enterprises and third-party auditors? Additionally, does the third-party auditor, as an important social institution, play a real monitoring and governance role? The study of these issues is of great practical significance. From this point of view, the government, third-party auditing institutions, and enterprises have different subject interests, interactions, and mutual influence, and there are obvious game characteristics in the development of water auditing systems. This study uses the game method to analyze the information asymmetry problem of enterprise water auditing, and to provide a new research perspective for the promotion of China’s environmental policy and policy implementation.

2. Literature Review

The existing literature on government environmental audits, natural resource asset exit audits, water resource optimization, water environment issues, water resource conflicts, and water resource management has garnered significant attention and importance within both domestic and international academic circles. These topics have become focal points for numerous scholars, yielding substantial research outcomes. Among these findings are themes closely related to water use audits. This paper explores three key dimensions: the evolution of water audit systems, the application of tripartite bargaining in environmental regulation, and mechanisms for mitigating information asymmetry. It provides clearer guidance for future research directions.

The Evolution of Water Auditing Systems: The Logic of Addressing Information Asymmetry from International Standards to Chinese Practice.

The water audit system fundamentally originated as a response to the issue of “corporate water information concealment”. In the 1970s, the U.S. Clean Water Act and the Dutch Water Resources Management Act pioneered mandatory corporate disclosure of water withdrawal and discharge data. This legal framework aimed to bridge the “businesses–public–government” information gap through legal constraints, with the core objective of reducing adverse selection where companies conceal water usage violations beforehand [

14,

15]. By the early 21st century, the institutional focus shifted toward “standardization”. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) released the ISO 14046 [

16] Water Footprint Accounting Guide, which, for the first time, incorporated the entire “water withdrawal–use–discharge” process into the audit scope. Subsequently, the 2013 Water Audit Methodology by the Working Group on Environmental Auditing (WGEA) proposed a three-dimensional framework of “Compliance–Economic–Ecological Impact.” This framework further reduced information asymmetry between audit bodies and enterprises by refining audit indicators, specifically addressing the moral hazard of post-audit data falsification [

17]. China’s water audit system follows a “gradual approach to mitigating information asymmetry”. In 2009, Suzhou pioneered the “Administrative Measures for Enterprise Water Audit,” reducing government pre-screening costs for audit service quality by specifying “qualification requirements for audit institutions” and “enterprise data submission checklists” [

8]. Subsequently, provinces like Jiangsu and Shanghai followed suit by enacting Water Conservation Regulations, refining “audit report verification procedures” to curb post-audit collusion between audit agencies and enterprises. In 2023, the Ministry of Water Resources promoted the “Water Conservation Loan” policy, making “participation in compliant water audits” a prerequisite for enterprises to obtain low-interest loans. This positive incentive reduces the adverse selection of enterprises “concealing water usage deficiencies to evade audits” [

11]. However, existing practices still face challenges, such as “significant regional disparities in incentive standards” and “insufficient cross-regional mutual recognition of audit results”, leading to the uneven mitigation of information asymmetry for enterprises operating across provinces.

2.1. The Application of Tripartite Game Theory in Environmental Regulation: The Absence and Supplementation of “Particularity” in Water Audit Scenarios. Core Research Framework: The Extension from “Binary Game Theory” to “Tripartite Interaction”

Research on game theory in environmental regulation has gradually expanded from a “government–enterprise” dual framework to a “government–enterprise–third-party institution” tripartite model; Qu Guohua et al. [

18] introduced international environmental auditing as a third-party entity, exploring the evolutionary paths and patterns of decision-making among the three parties under the intervention of third-party international audits. Their findings revealed that third-party international environmental auditing can drive polluting enterprises to actively implement green environmental behaviors. Based on frequent violations by third-party environmental monitoring agencies, Kou Po et al. [

19] employed an evolutionary game model to study the behavioral evolution of these agencies in scenarios of subjective oversight deficiencies and objective regulatory inadequacies by polluting enterprises and local governments. Notably, some studies have adopted a “dynamic game” perspective: Zhang Ming et al. [

20] constructed a “central inspection team-local government–enterprise” tripartite model, finding that the “cyclical pressure” from central inspections can compel local governments to strengthen oversight, indirectly reducing enterprises’ preemptive concealment of violations. Chen Zhisong et al. [

21], while emphasizing “government–enterprise collaboration” in watershed water resource allocation games, excluded third-party auditing entities, failing to capture the core role of audit agencies as information intermediaries in water audits.

2.2. Research on Mechanisms to Mitigate Information Asymmetry: The “Synergy Gap” Between Technological Tools and Institutional Design. Technological Tool Innovation: Breakthroughs from “Data Quantification” to “Process Visualization”

Zhang et al. [

22] enhanced the transparency of corporate water usage data by over 50% through the introduction of implicit indicators, such as the “evaporation loss coefficient” and “water recycling rate”, directly reducing opportunities for companies to conceal water usage deficiencies beforehand. Barrington et al. [

23] employed water auditing techniques to investigate an oil refinery in Western Australia. Their research demonstrated that water auditing serves as a straightforward and effective method for revealing water management procedures and driving continuous improvement, thereby advancing the ideal practice of zero liquid discharge. Lyu et al. [

24] enhanced traditional water accounting and audit frameworks. By leveraging data from water flow meters and water accounting reports, they conducted a follow-up study on Coca-Cola Beverages (Hebei) Co., Ltd. (Hebei, China). Their findings indicate that water auditing significantly benefits industrial enterprises by promoting cleaner production and improving water efficiency. Agana et al. [

6] tested a water management model incorporating water auditing against the water management strategies of manufacturing companies in West Melbourne. They found that water auditing activities not only create water flow diagrams to identify water-saving opportunities in usage processes and achieve significant cost savings, but also uncover water usage violations during audits, enabling timely management interventions to address water risks. Nandini Manne et al. [

25] used Indian steam power plants as a case study. By quantifying plant water flows and conducting systematic water audits, they proposed water-saving measures and recommendations, providing robust support for optimizing corporate water resource management.

2.3. Concurrently Incentive and Regulatory Mechanisms: Shortcomings in the Transition from “Single-Subject” to “Tripartite Collaboration”. Institutional Mechanism Research Exhibits “Breakthroughs by Distinct Actors”

Regarding positive incentives, Xu Zhiyao et al. [

26] found that the “reward mechanism” in government environmental performance audits enhances corporate cooperation; the Ministry of Water Resources’ “water-saving loans” reduce adverse selection where enterprises conceal water usage deficiencies through cash flow support. Lu Rui and Tang Kai [

27] indicate that “reputational penalties” (e.g., license revocation) imposed by governments on audit agencies are more effective than fines intended to curb rent-seeking. Li Yanru et al. [

28] observed in natural resource asset exit audits that accountability mechanisms linking audit outcomes to local government performance evaluations reduce the probability of collusion between local governments and enterprises.

As indicated by the preceding literature review, research on corporate water audits in China has predominantly focused on optimizing government oversight. Few studies have addressed the dual dimensions of information asymmetry—pre-event and post-event (adverse selection and moral hazard)—and there remains a significant gap in analyzing the information gap mechanisms within the tripartite interaction. This study breaks from traditional static approaches by integrating information asymmetry theory with evolutionary game theory, filling a gap in the literature by “analyzing tripartite information interactions and dynamically capturing strategy evolution”. Unlike conventional audits that address information asymmetry, this research examines the issue within the context of corporate water audits, using an evolutionary game model [

29]. First, a tripartite game model involving the government, enterprises, and third-party audit agencies is constructed. Second, we analyze strategy choices and parameter impacts in different scenarios, deriving evolutionary stable equilibrium solutions. Finally, we draw conclusions about the decision-making behavior of game participants, offering significant practical implications for optimizing government water audit system strategies. This research enhances understanding of the relationships among governments, enterprises, and third-party audit agencies, mitigates information asymmetry, improves corporate information transparency and reliability, and provides a reference for formulating effective water audit system strategies. It holds significant importance for achieving new pathways in modern water management and mitigating water risks within China’s modern industrial system. Simultaneously, it addresses deficiencies in the public service capabilities of government water administrative departments.

3. Game Rules and Modeling

3.1. Introduction to the Rules of the Game

(1) Evolutionary Participation Subject: Referencing Zhang et al., Kou et al., and existing research results, based on the evolutionary game theory, this research set out the following basic game subject [

30,

31]. In the water auditing system, considering the response to the higher degree of relevance of the government (G), enterprises (C) and the third-party auditor (A) in participating, the three parties in the game process are limited rationality, in order to facilitate the later game model construction, and the information asymmetry phenomenon of the parties to the game is analyzed. The optimal strategy is found by analyzing and playing the game several times.

(2) Strategic Assumptions of Government Behavior: Two behavioral strategies are possible for the water authority (government). One is that the government fulfills its responsibility to strictly supervise the water use audit process, which centers on actively promoting and providing green finance-related products and services, such as water-saving loans, to enterprises with better water resource management, as means of incentives and penalties. The purpose of this strategy is to incentivize the research, development, and application of water-saving technologies by enterprises, thus promoting a smooth shift in the market in the direction of green development. The second option is that the water authorities do not fulfill their responsibilities, and a negative attitude towards the water audit process and malfeasance occur. In this strategy, the water authorities do not take the initiative to provide incentivized financial services or intervene in the activities of companies and third-party water auditors. Therefore, the set of strategies of the government is G = (G1, G2) = (fulfillment of duties, non-performance of duties), and x (0 ≤ G ≤ 1) is used to denote the probability of the government’s strategy of choosing to fulfill its duties, and 1-x is the benefit of the government’s strategy of choosing not to fulfill its duties.

(3) Strategic Assumptions about Firm Behavior: Two different behavioral strategies are possible for firms. One is to actively cooperate with the water audit system. Under this strategy, enterprises will cooperate actively, provide relevant data and information, fully cooperate with the inspection and assessment work of the auditing institution, take the problems and suggestions in the audit report seriously, and take active measures to carry out internal rectification and optimization to improve water resource management and water saving efficiency. The second involves negative cooperation with the water audit system. Since there is a certain degree of information asymmetry between enterprises and both the government and third-party audits, enterprises will weigh their benefits to choose honesty or concealment. Under this strategy, in order to cope with the concerns and pressures of various stakeholders, they may disclose the audit report to whitewash their water environment performance and create a green image of corporate sustainability [

28]. Therefore, the enterprise’s strategy set is E = (E1, E2) = (positive cooperation, negative concealment), Y (0 ≤ E ≤ 1) denotes the probability of the enterprise’s strategy of choosing to cooperate positively, and 1-Y is the enterprise’s strategic gain from choosing to cooperate negatively.

(4) Strategic Assumptions about Third-Party Auditors’ Behavior: Third-party auditors may adopt two different behavioral strategies. One is the strategy of strictly regulating auditing behavior. Under this strategy, the auditing institution strictly abides by the provisions of laws and regulations, and, once problems are found, they will immediately report them to the local water administrative department and provide relevant audit evidence and recommendations. The second strategy entails displaying rent-seeking behavior. There is information asymmetry between the third-party auditing organization and the government, and the personnel of the auditing organization take advantage of their position of information superiority, for the purpose of obtaining undue economic benefits. Therefore, the set of strategies of the third-party auditor is A = (A1, A2) = (Strict Audit, Audit Rent Seeking), and Z (0 ≤ A ≤ 1) is used to represent the probability of the strategy of the third-party auditor’s strict specification of the audit, and 1-Z is the benefit of the strategy of the third-party auditor’s choice of rent-seeking behavior.

(5) Other Variables Assumptions: Government departments, in their daily work to obtain the social benefits of S1, undertake the following: government daily supervision under the cost of C1; the government, based on the results of the audit of the enterprises, issue incentives, or based on the quality outside the penalty, the credibility of the degree increases R1, while the occurrence of rent-seeking third-party auditing institutions will be fined P with the removal of incentives and rewards L1. When the government does not perform its duties, the community’s trust in it declines, it is unable to obtain from the businessmen and third-party auditing institutions the correct information, and the government regulator will continue to grant subsidies L1, based on the inspection results of the third-party agency, without imposing any penalties.

Normal production activities of the enterprise revenue for S2 are as follows: If they actively cooperate with the government water auditing system norms, resulting in the treatment of water pollution environmental protection costs C2, they will receive incentives from the government department reward L1. If the enterprise negatively cooperates with the government water auditing system, and the sewage is secretly discharged but found by the third-party auditing department and reported to the government department, they need to pay the water environment penalties F, resulting in the intangible loss of the enterprise’s reputation for the W.

The third-party auditor’s normal audit profit is denoted S3, if the normal strict audit, under the cost of the same, found problems and reported them to the government, it would receive incentives L2. Enterprises’ negative cooperation with the government system of enterprise production violations is negated via a third-party auditor, used in order to help the enterprise to set the government incentives, and audit rent-seeking gains X1, and the occurrence of counterfeiting violation costs C3. If the law is violated by the relevant government departments, they must be investigated and punished. To summarize, the payoff matrix of the tripartite evolutionary game model of the government, enterprise, and third-party auditor is constructed as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

3.2. Model Construction

- (1)

Return function construction

According to

Table 1 and

Table 2, the expected return of the government in the game for choosing the strategy of “fulfillment of duties” is

, the expected return for choosing the strategy of “non-fulfillment of duties” is

, and the average expected return

are, respectively, as follows:

The expected payoff

for firms choosing the “active cooperation” strategy, the expected payoff

for firms choosing the “passive participation” strategy, and the average expected payoff is

, which, in the game are, respectively, as follows:

The expected

returns of the audit firms choosing the “strict audit” strategy, the expected returns

of the “rent-seeking” strategy, and the average expected returns

of the audit firms choosing the “rent-seeking” strategy in the game are, respectively:

- (2)

Solving evolutionary stabilization strategies using replicated dynamic equations

In the game process, if the return of a certain strategy is higher than the average return of other strategies of the group, it means that choosing this strategy can effectively resist the intrusion of other potential strategies and can better adapt to the evolutionary process of the group [

29]. In the following, we analyze the evolutionary stabilization strategies of enterprises, governments, and third-party auditors by constructing replication dynamic equations for governments, enterprises, and the public, respectively. The replicated dynamic equations for the government follow:

For the government, the conditions F(x) = 0 and F′(x) < 0 need to be satisfied. Derivation based on their replicated dynamic equations leads to the following three scenarios:

- ➀

When , at this point, F(x) ≡ 0. Thus, it is shown that all levels are at a steady state under this condition, i.e., the government’s strategy does not change over time, regardless of whether the government chooses to perform its duties or not.

- ➁

When , at this point, there exists F′(x) > 0 as well as F′(1) < 0. Therefore, X = 1 is an evolutionarily stable strategy point, where the government will choose a strict regulatory strategy.

- ➂

When , at this point, there exists F′(x) < 0 and F′(1) > 0. Therefore, X = 0 is the point of evolutionary stable strategy, and the government will choose the non-performance strategy. It is the lax regulatory approach, i.e., the water authority’s “lying down”, negative attitude towards the promotion of the water audit system.

Through the above analysis, some useful conclusions can be drawn from the governmental perspective. Firstly, reducing the cost of government regulation is an effective measure that can improve the efficiency and reputation of government regulation. Secondly, strengthening the penalties for enterprises that violate the law by discharging pollutants is also an important measure. The government can adopt tougher penalties to ensure that enterprises comply with environmental regulations so as to protect the environment and the public interest.

The firm-specific replication of dynamic equations follow:

Similarly for businesses, the need to fulfill equally similar conditions yields the following three scenarios:

- ➀

When , at this point, F(y) ≡ 0. Thus, the evolutionary strategy is always stable, no matter what value of y is taken.

- ➁

When , in this case, F′(y) > 0 and F′(1) < 0. Therefore, y = 1 is an evolutionarily stable strategy point, and the firm will choose to cooperate actively with the water audit system.

- ➂

When , at this point, F′(y) < 0 and F′(1) > 0. Therefore, y = 0 is the point of evolutionary stable strategy, and the enterprise adopts a more passive attitude towards the water audit work. It may perfunctorily cope with the audit work and may not actively cooperate with the related work.

Through the above analysis, it can be seen that unnecessary administrative penalties and reputational losses can be avoided through the intervention of incentive and penalty mechanisms, and the active reduction in water pollution costs by enterprises.

The replicated dynamic equations for third-party auditors follow:

Similarly for third-party auditors, the need to fulfill equally similar conditions yields the following three scenarios:

- ➀

When , at this point, F(z) ≡ 0. When the eight equilibrium points are substituted is always stable, no matter what value z takes.

- ➁

When , at this point, there exists F′(z) > 0 as well as F′(1) < 0. Therefore, z = 1 is the point of evolutionarily stable strategy, where the third-party auditor strictly regulates the auditing behavior.

- ➂

When , at this point, there exists F′(z) < 0 as well as F′(1) > 0. Therefore, z = 0 is the point of evolutionarily stable strategy, where rent-seeking behavior occurs and the third-party auditor may appear to fabricate false audit reports and generate audit rent-seeking gains.

Through the above analysis, under the incentive of the government, the supervision of the third-party auditor’s auditing of enterprises becomes positive; under the government’s failure to perform its duties, the third-party auditor is more prone to the rent-seeking phenomenon, and, therefore, the auditor who has violated the law is strictly punished.

The evolutionary stabilization strategy (ESS) for a system of differential equations can be obtained by associating Equations (10)–(12) according to the method proposed by Friedman. This strategy can be obtained by performing a local stability analysis on the Jacobi matrix of this system. The Jacobi matrix of this system can be obtained from Equation (13):

In system (10) (11) (12), let F(x) = F(y) = F(z) = 0, which leads to eight equilibrium points, E1 (0,0,0), E2 (0,0,1), E3 (0,1,0), E4 (0,1,1), E5 (1,0,0), E6 (1,0,1), E7 (1,1,0), and E8 (1,1,1). According to the evolutionary game theory, the equilibrium point that satisfies the Jacobi matrix when all eigenvalues are nonpositive is the evolutionary stability point (ESS) of the system.

3.3. Stability Analysis of Equilibrium Points

The following first analyzes the case where the equilibrium point is E1 (0, 0, 0), and it can be seen that the eigenvalues of the Jacobi matrix at this time are

;

;

. When the eight equilibrium points are substituted into the Jacobi matrix (13), you can, respectively, obtain the eigenvalues of the Jacobi matrix corresponding to the equilibrium points, as shown in

Table 5. It can be seen that in the replication of the dynamic equations there are two stable points, E4 (0,1,1) and E8 (1,1,1), through which the two scenarios on the stability of the evolution of the game can be analyzed and discussed.

- ➀

When , there exists an evolutionary stability point E4 (0,1,1), and the corresponding evolutionary stability strategy is (non-performance, active cooperation, and strict auditing), i.e., the government’s reward and punishment mechanism effectively constrains the enterprise and the third-party auditor, and the third-party auditor, with the sum of the costs of falsification and violation being higher than the benefits under rent-seeking, chooses the strict auditing strategy to inhibit the enterprise from inflicting negative behaviors on the water environment, and to promote the enterprise to optimize the management of water resources.

- ➁

When , the evolutionary stability point E8 (1,1,1), corresponding to the evolutionary stability strategy is (fulfillment of responsibilities, active cooperation, and strict auditing); that is, the enterprise facing the violation of the water and environmental penalties incurred, faces the loss of reputation, as well as the cost of extracting government subsidies, which is higher than the cost of environmental protection under the enterprise’s active governance, and the cost of the third-party auditor’s forgery and violation is higher than the sum of the cost of the rent-seeking under the gains—at this time, the corresponding eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix are all nonpositive, and the system has a stability point in this scenario.

4. Simulation Analysis and Implications

For the more ideal stability state, E4 (0,1,1) and E8 (1,1,1), in the system, and according to the method of parameter assignment in the literature [

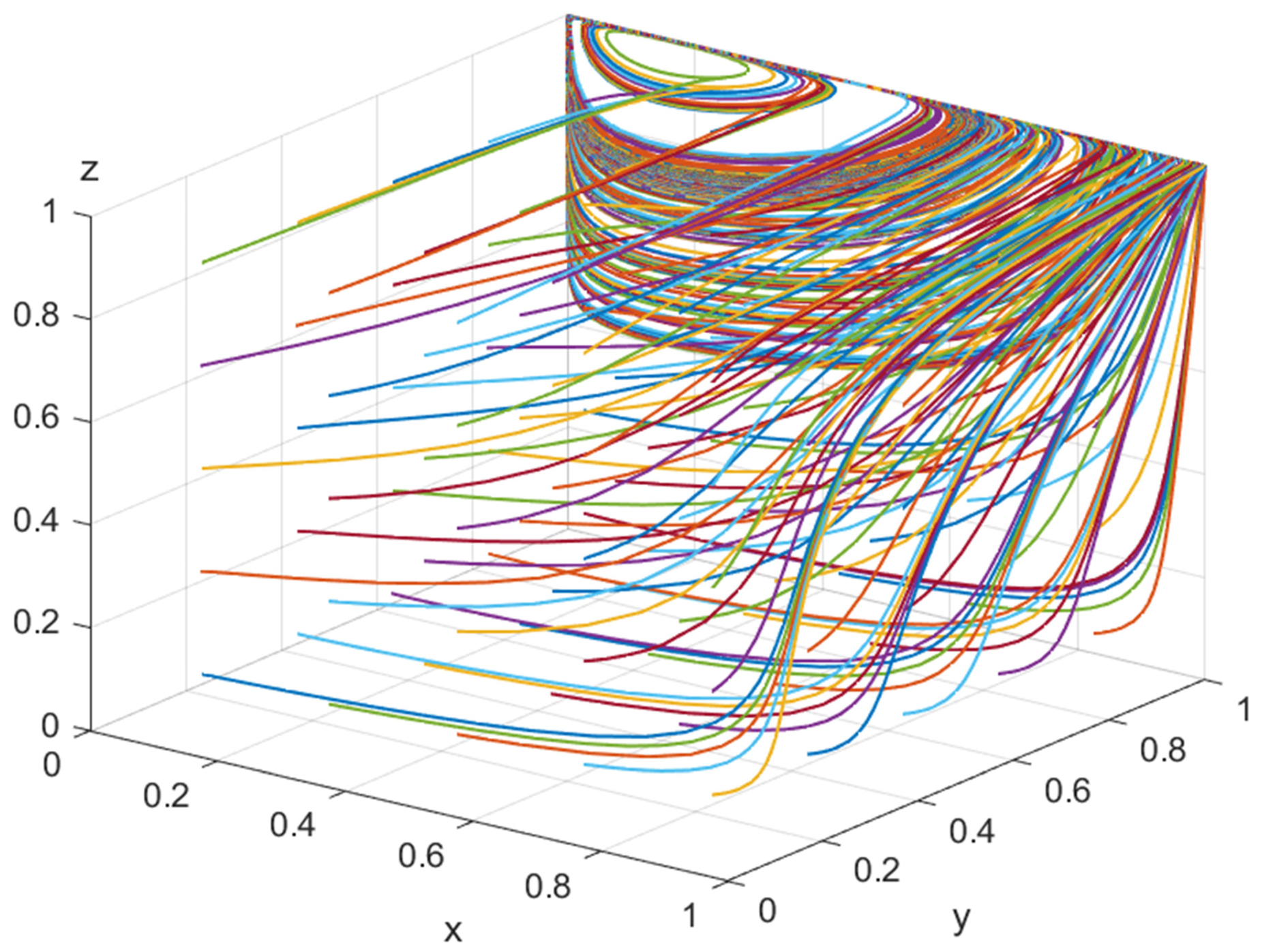

30], for let array 1: C1 = 2, C2 = 4, C3 = 3, R1 = 0.5, P = 20, L1 = 6, L2 = 4, F = 10, W = 8, X1 = 6; for let array 2: C1 = 2, C2 = 4, C3 = 3, R1 = 5, P = 20, L1 = 6, L2 = 4, F = 10, W = 8, X1 = 6; and the rest of the parameters are the same as array 1 to satisfy the conditions in case 1 and case 2.1, respectively. Numerical simulation is carried out by the MATLAB 2022b software, to validate the accuracy of the evolutionary stability above as well as to explore the role of comparing and contrasting the different strategic means in solving the information asymmetry.

4.1. Model Check

In order to verify the validity of the stability analysis of the equilibrium point of the system, the following considerations were made, including the impact of different parameters on the government, enterprises, and third-party auditing organizations to choose the strategy, the array 1 to meet the conditions of ①, and the array 2 to meet the conditions of ②, and the two groups of values were simulated for 50 times, and the results of the operation are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5.

As can be seen from

Figure 2, the system evolves to (0,1,1) under the condition of array 1, i.e., the government does not fulfill its responsibility, the enterprise actively cooperates, and the third-party auditor strictly audits, which is the same as that described in condition ①. It can be seen in

Figure 3 that the system evolves to (1,1,1) under the condition of array 2, when the combination of strategies (the government fulfills its responsibility, the enterprise actively cooperates, and the third-party auditor strictly audits) existed, which is consistent with the condition described in condition ②, and the simulation analysis is in line with the conclusion of the evolutionary stability above, indicating that the model is accurate and reliable, and can guide the collaborative management of water authorities, enterprises, and third-party audit institutions. The simulation analysis is consistent with the above conclusion of evolutionary stability, indicating that the model is accurate and reliable, and is a guide for the collaborative governance of water authorities, enterprises, and third-party auditors. The effects of C1, C3, L1, L2, and F on the process and results of the evolutionary game are analyzed under condition ②.

4.2. Evolutionary Impacts Under Government Regulation

Under research condition ②, C1 is assigned values of 2, 6, and 10 to replicate the results of the simulation of the dynamic system of equations evolving over time for 50 times, and, as can be seen in

Figure 5, we can see that the probability of firms and third-party auditors gradually increases with time. This result proves the importance of government regulation. In the initial stage, the probability of enterprises and third-party organizations may be low (

Figure 6a,b) because the government’s supervision of enterprises and third-party auditing organizations is weak, and the motivation to participate in supervision is relatively low. However, over time, increased government pressure to regulate the water auditing system leads to more active participation in the oversight process by firms and third-party auditors, which leads to a rapid increase in the probability of firms and third-party agencies. The comparison in

Figure 6c shows that third-party auditors are professional and independent in monitoring and assessing the water environment behaviors of enterprises, and the pressure from the government has a more significant effect on them, which makes them more likely to be guided by the government’s regulation and to increase their participation more quickly at the government’s request.

Insight 1: The importance of government oversight is demonstrated in two ways. First, sustained government pressure on companies to participate in water audits can encourage companies and third-party auditors to participate actively in water audits. Continued government pressure makes companies aware of the importance of water audits and encourages them to take steps to participate in audits to meet the standards and requirements set by the government. Secondly, the impact of government pressure on third-party auditors is even more significant. Third-party organizations, as independent auditing entities, increase their engagement more rapidly under government oversight. Regulatory pressure from the government encourages third-party organizations to strengthen their auditing capabilities and provide high-quality auditing services to meet the need for the transparency and reliability of government information. The key role of government in maintaining public services for corporate water management was emphasized, as well as the importance of government oversight in promoting the active participation of corporations and third-party organizations. The risk of information asymmetry is reduced by emphasizing the importance of government oversight to ensure that the information it provides is truthful and reliable.

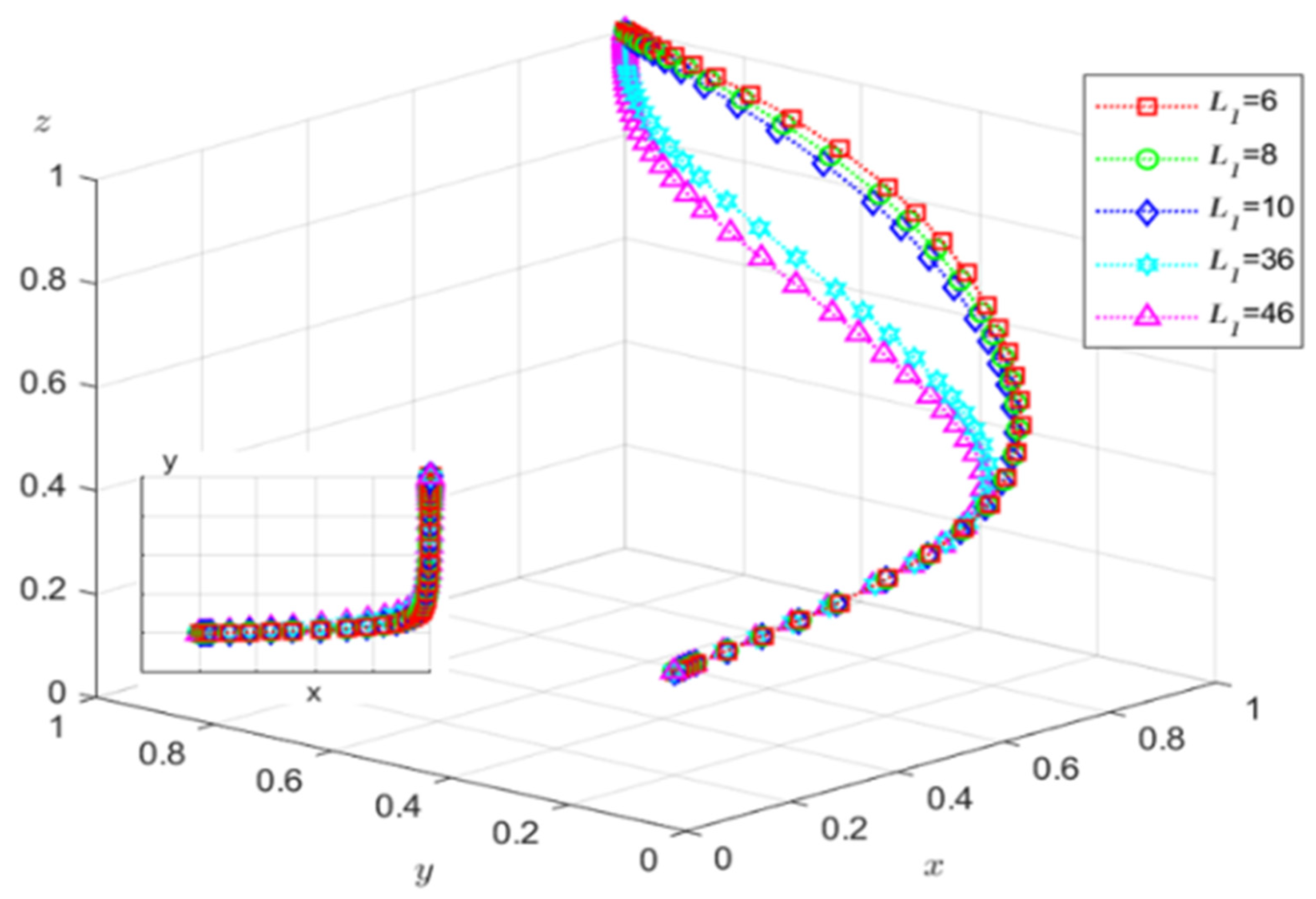

4.3. Evolutionary Impacts Under Incentive Subsidies

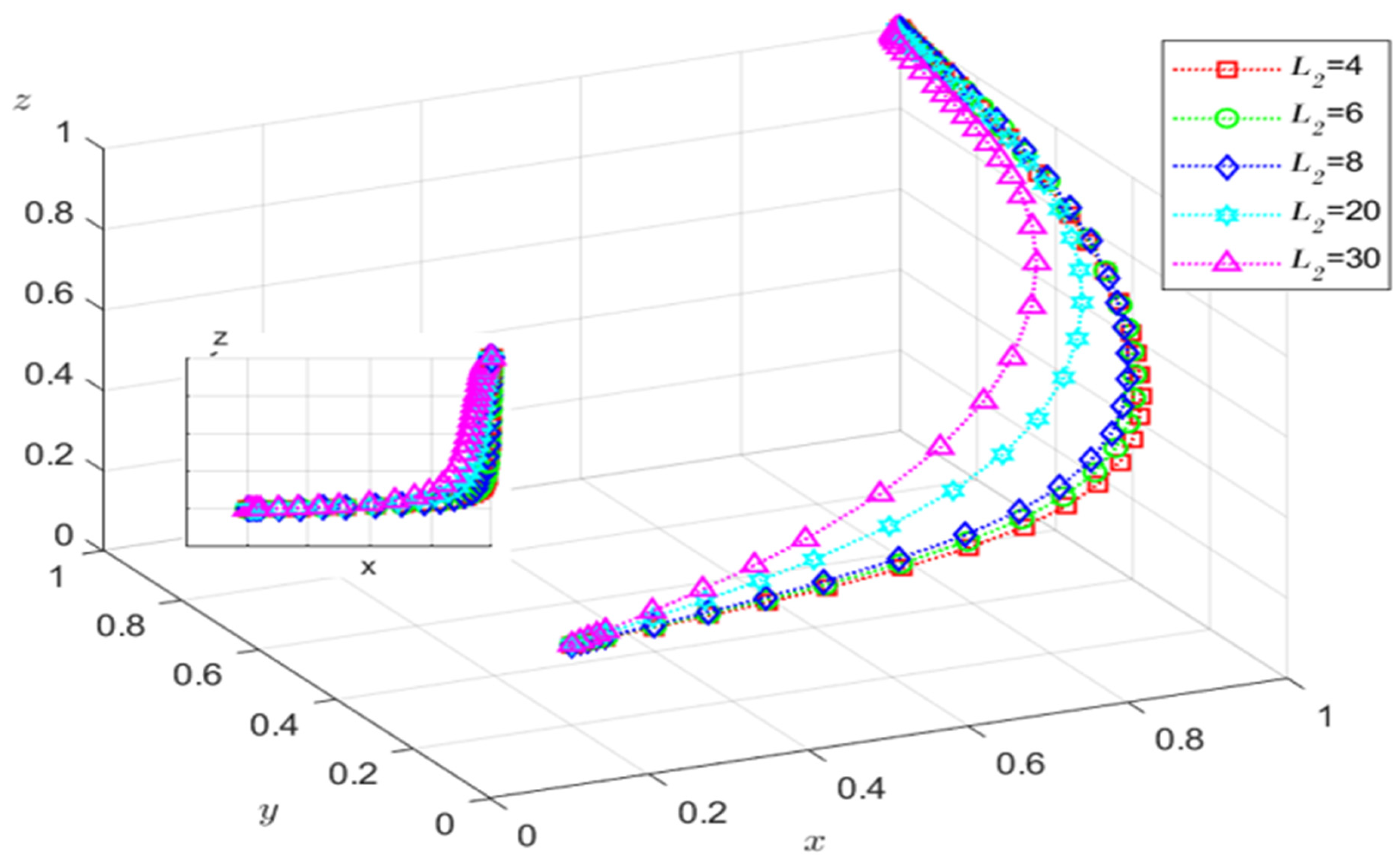

For the information-disadvantaged party, incentive subsidy policy is one of the important strategies to solve the information asymmetry problem. Under the same condition study, under the condition that other parameters are certain, assign L1 = 6, 8, 10, 36, 46, and L2 = 4, 6, 8, 20, 30, respectively. The effect of the change in incentive subsidy strength on the system evolution results when enterprises and third-party auditors participate in the water audit system.

Figure 7 shows that as time increases, we find a gradual increase in the probability of firms subsidizing institutions. In the initial stage, the institutional probability of firms subsidizing may be low because the financing incentive is not yet fully realized and firms may prefer other strategies. However, at L1 values of 36 and 46, this upward trend is more pronounced, and the financing incentives provided by the government make firms more motivated and capable of choosing subsidy-related strategies to gain more benefits and returns. This indicates the importance of government-led financing incentives in driving firms to adopt subsidy-related strategies. Government incentives can reduce the financial pressure and risk of firms in the decision-making process while increasing their motivation to participate in subsidized institutions.

Figure 8 shows that the impact of government incentives for audit firms gradually emerges as government incentives increase. Under this incentive mechanism, audit firms are motivated to improve the quality and level of their audits in order to obtain rewards from the government. Over time, audit firms gradually adopt rigorous auditing strategies and evolve to a more cooperative and sustainable state. At the same time, this dynamic evolution helps to raise the level and standard of the entire auditing profession, and promotes the development of the auditing profession in a more professional and standardized direction.

Insight 2: The impact of incentive subsidies for water auditing systems can be seen in two ways. First, governments can provide incentives for companies to adopt behaviors that are consistent with the government’s policy objectives, by providing subsidies and directing financing incentives to enhance compliance and transparency in water management. These incentives encourage companies to proactively engage in water auditing activities, adopt sustainable water management strategies, and push companies to improve their water management practices. Second, the government can provide incentives to third-party auditors that conduct rigorous audits, to improve audit quality and standards. When third-party auditors are recognized and rewarded by the government, investors and stakeholders are more likely to trust the information and opinions provided by the auditors, which, in turn, enhances market transparency and protects investor rights. In addition, government rewards for rigorously audited audit firms can be used as part of the establishment of an effective regulatory mechanism.

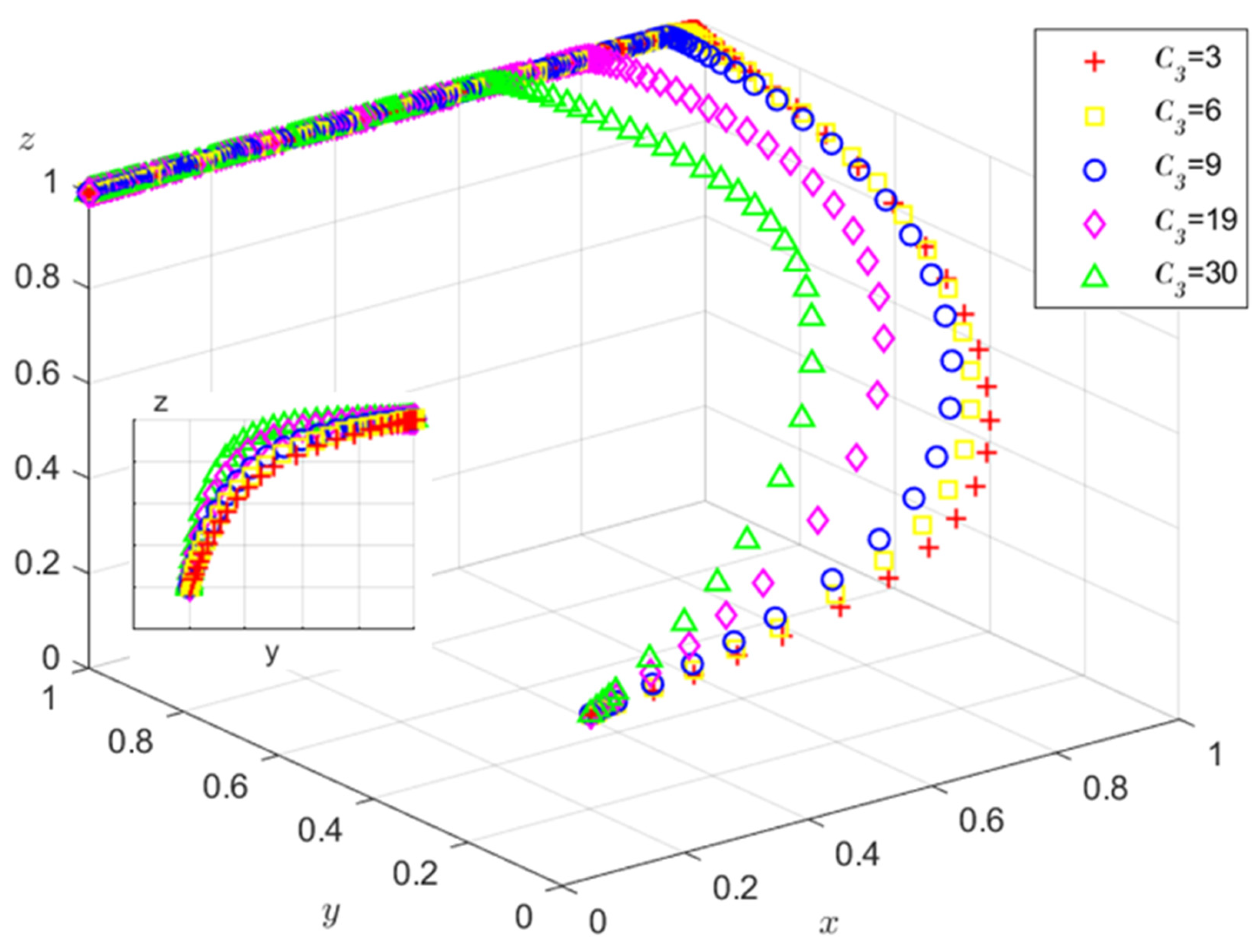

4.4. Evolutionary Impacts Under High Rent-Seeking Costs

Under the same conditions of the study, under the condition that other parameters are certain, F is assigned the value of C3 = 3, 6, 9, 19, and 30. It can be seen from

Figure 9 that as C3 increases, i.e., as the cost of third-party auditing institutions’ falsification and violation of rules rises, the probability of enterprises participating in cooperation “rent-seeking” decreases. This is because a higher cost of fraud increases the risk of cooperation, which may lead to legal liability, reputation damage, or market penalty. Therefore, enterprises are more likely to avoid cooperation with high-risk third-party organizations. The rising costs of fraud and violations by third-party auditors may trigger increased legitimacy requirements. Government and market demand for legitimacy and transparency from firms are likely to increase in response to potential risks from third-party organizations. This may include stronger regulatory and auditing regimes, higher compliance requirements, and increased penalties. Firms should avoid engaging in “rent-seeking” for audit cooperation to avoid the negative reputations associated with non-compliance.

Insight 3: When the cost of fraud and violation of third-party auditing organization is high, it will affect the probability of enterprises’ participation in cooperative “rent-seeking”. When choosing a third-party auditing organization, enterprises will be affected by the organization’s market reputation, industry influence, and other factors, and if the third-party auditing organization’s rent-seeking costs are very high, the probability that enterprises will participate in cooperation to “rent-seeking” will be reduced in this case. They will be more cautious in assessing costs and benefits, and may face higher legitimacy requirements. This change in the evolutionary game will, in turn, push enterprises to pay more attention to legitimacy, thus improving the stability and fairness of the market and resolving the risk of information asymmetry.

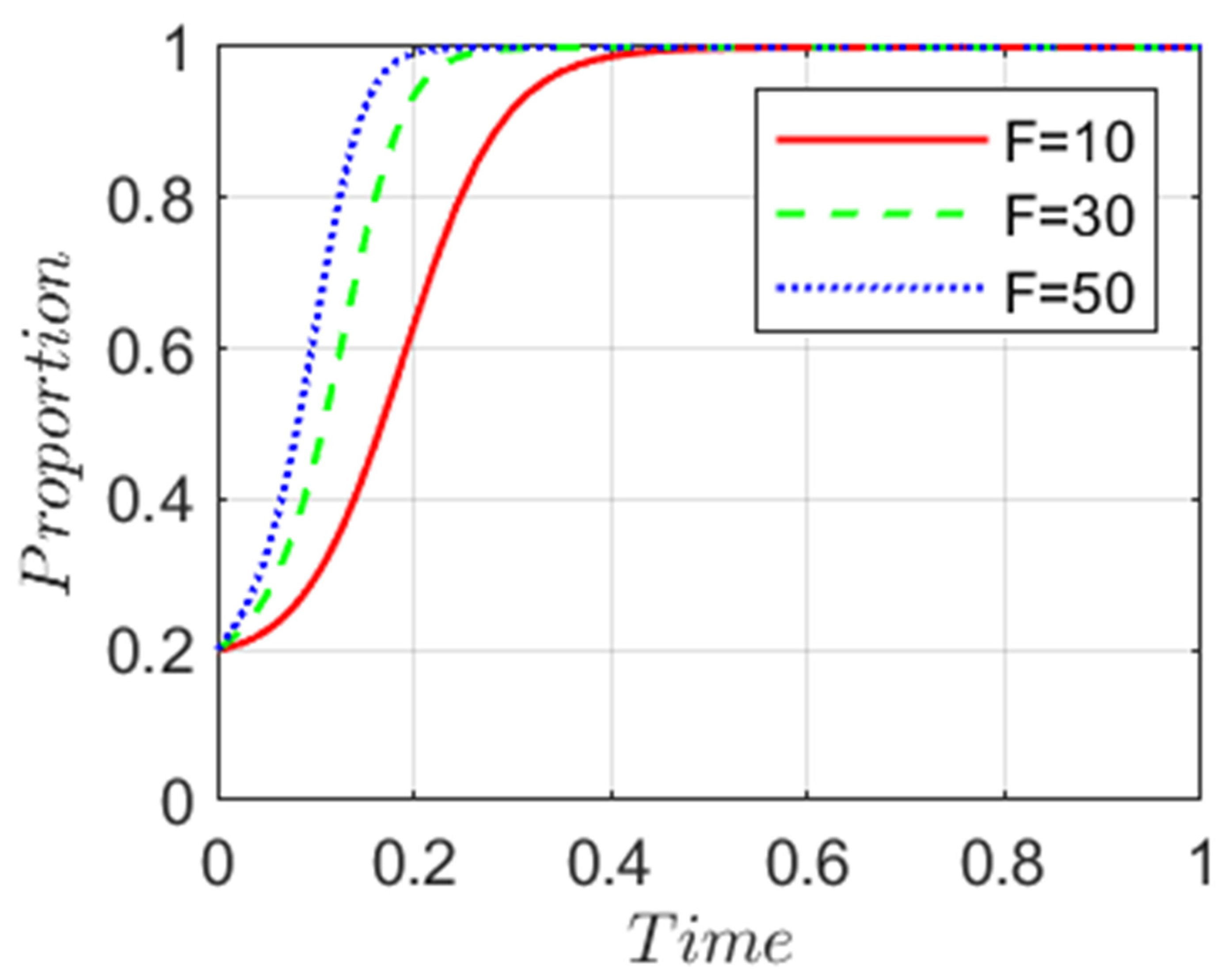

4.5. Evolutionary Impact Under Third-Party Endorsement

Under the same conditions of the study, under the condition that other parameters are certain, the value of F = 10, 30, and 50 is assigned.

Figure 10 shows that the penalty imposed by the third-party auditor on the violating firms can have an impact on the rate of the stable point of the system’s evolution. That is, the larger the penalty, i.e., the harsher the punishment imposed on the violating firms, the faster the rate of adjustment of the system evolution to the stable point will be. Penalties imposed by third-party auditors can force, offending firms to change their strategic behavior by weakening their competitiveness. The presence of penalties exposes the offending firms to more disadvantages in market competition, and to the risk of financial losses and reputational damage. This penalty effect prompts the offending firm to adjust its behavior and become more inclined to comply with the rules and take measures to optimize the management of water resources.

Insight 4: Third-party auditors, as important social institutions, promote the disclosure of information on water use by enterprises through auditing, assessment, and penalization, which improves the transparency of water resources’ management and reduces the risk of information asymmetry. In addition, corporate management can reduce adverse selection by strengthening regulatory compliance and establishing appropriate internal control mechanisms for water resource management to ensure compliance with regulations and to ensure social responsibility. At the same time, the accuracy of the audit results can identify opportunities for improvement and innovation, leading to the adoption of more sustainable water management strategies. Enterprises should respond positively to the audit organization’s recommendations and suggestions, which can help build a good reputation for corporate social responsibility.

The study’s findings exhibit a relationship of “partial corroboration with core divergence” to the existing literature. In terms of corroboration, its conclusion that government regulation drives corporate water audits aligns with Xu Zhiyao et al. (2023)’s [

26] assertion that “government audits improve water quality” and Li Yanru et al. (2022)’s [

28] view that “strict regulation enhances pollution control effectiveness”. The finding that “incentive mechanisms enhance stakeholder motivation” corroborates Qu Guohua et al. (2021)’s [

18] conclusion that “incentives drive third parties to promote green behavior”. The divergence lies in the existing literature’s predominant focus on government–enterprise dyadic interactions and neglect of third-party auditor involvement and information asymmetry conflicts. Furthermore, it emphasizes policy effectiveness verification with limited analysis of tripartite conflicts of interest. This paper centers on information asymmetry, constructing a government–enterprise–third-party evolutionary game model. It derives novel conclusions, such as “reduced rent-seeking costs lower corporate violation probability” and “third-party penalties accelerate system stabilization”, thereby filling gaps in the literature, using a government–enterprise–third-party evolutionary game model centered on information asymmetry. The differences stem from three aspects: the research perspective shifts from “binary interaction” to “tripartite coordination”, better aligning with real-world scenarios; the core issue evolves from “validating policy effectiveness” to “resolving information asymmetry dilemmas”; and the analytical method transitions from “static empirical analysis” to “dynamic evolutionary game theory”, enabling the capture of long-term strategic shifts among actors and providing more precise theoretical support for water audit practices

5. Conclusions and Suggestion

This study constructs a three-party evolutionary game model involving enterprises (Agent 1), government (Agent 2), and third-party audit agencies (Agent 3) within the context of China’s industrial water management. Through MATLAB simulations of strategy evolution paths under various parameter combinations, the core conclusion is reached: when regulatory fines for corporate water violations exceed 30% of annual water costs, penalties for third-party audit fraud surpass twice the illegal gains, and when post-compliance water savings cover 1.5 times audit expenses, the three parties converge to an evolutionary stable equilibrium: “enterprises voluntarily accept audits, regulators conduct spot checks, and third-party agencies perform truthful audits”. Under this equilibrium, industrial water efficiency improves by 19.2% compared to the baseline scenario. Based on these simulation results, the following actionable policy recommendations are proposed:

Optimal Subsidy Rate Range and Implementation Rules: The subsidy rate range is set at 15–22%, determined through elasticity analysis of “fiscal burden versus corporate incentives”. At a 15% subsidy rate, industrial enterprises in eastern regions demonstrate a 68% willingness to participate in audits—a 42% increase compared to the no-subsidy scenario. When the subsidy rate exceeds 22%, the marginal increase in water-saving efficiency per unit of subsidy drops to 0.3%, significantly reducing the efficiency of fiscal fund utilization. Subsidies are disbursed only when two conditions are met: enterprises proactively commission third-party institutions for audits, and audit results demonstrate annual water-saving efficiency improvements exceeding 8%. The subsidy process follows a “audit-first, subsidy-later” approach. Regulatory authorities verify audit reports before directly offsetting water fees through enterprise water accounts, preventing fund diversion.

Third-Party Agency Blacklist Criteria and Management Mechanism: Blacklist determination criteria are categorized into three scenarios: 1. The cumulative occurrence of two audit reports within one year with an error rate exceeding 5% (error rate determined by regulatory authority’s sample verification data). 2. One instance of data falsification (including tampering with enterprise water usage records or fabricating water conservation data). 3. Failure to file audit projects as required on three occasions. Upon inclusion in the blacklist, the institution undergoes a 30-day public notice period (to receive appeals from enterprises and the public). If no objections are raised, its audit qualifications are suspended for 1–3 years (fraudulent acts result in an immediate 3-year suspension). During this period, the institution must participate in compliance training organized by regulatory authorities. After the suspension period, business operations may resume only upon passing a qualification review.

Scope of Application and Country-Specific Adaptability: The findings of this study are primarily applicable to the Chinese context. Model parameters—such as the delineation of regulatory authority based on the Water Resources Law of the People’s Republic of China and the enterprise water pricing standards referenced from China’s water pricing reform policies—are designed within China’s institutional framework. These conclusions provide direct guidance for implementing water audit systems for industrial enterprises across eastern, central, and western China. Simultaneously, it holds reference value for countries with per capita water resources below 1000 cubic meters (the UN-recognized “water scarcity” threshold) and those facing industrial water use control pressures; Israel, for instance, maintains an industrial water conservation subsidy rate of approximately 18–25% (exceeding China’s upper limit). Given its extreme water scarcity and substantial fiscal support for water-saving technologies, Israel could adopt China’s dual “subsidy + blacklist” mechanism while increasing subsidy rates to align with its resource endowment. South Africa could adopt China’s tiered penalty system for blacklisting. Given its decentralized water regulatory framework, incorporating provincial oversight bodies into blacklist determination would enhance policy enforcement efficiency. For resource-rich nations with lenient industrial water controls (e.g., Brazil, Canada), this study’s conclusions hold limited applicability, though the standardized audit process design remains relevant.

Research Limitations and Future Directions: Existing studies exhibit three key limitations: First, the model fails to incorporate the impact of sudden water resource crises (such as regional droughts). Under drought conditions, enterprises may conceal violations due to soaring water costs, while third-party institutions may lower audit standards under corporate pressure. Subsequent research should develop dynamic game models incorporating crisis variables. Second, data sources exhibit regional bias. Eastern industrial enterprises constitute 72% of the study sample (primarily from the Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta), while samples from water-intensive industries in central and western regions (e.g., coal chemical and metallurgy) are insufficient. Given the complex water usage processes and higher audit difficulty in these sectors, the applicability of the model conclusions to them requires validation through supplementary research. Third, the impact of digital technologies on audit efficiency remains unaccounted for. Current audits primarily rely on manual ledger verification, whereas technologies like smart water meters and IoT real-time monitoring can reduce audit error rates to below 3%. Future research should quantify the influence of digital technologies on third-party strategy selection. Additionally, the study did not address the strategic differences between SMEs and large enterprises (SMEs bear higher audit cost ratios and exhibit lower participation willingness). Future research could refine the game model by enterprise size and propose differentiated policies. Extended Research Value: The dual “incentive-constraint” policy framework developed in this study is applicable not only to water audit scenarios but is also extendable to environmental regulatory contexts, such as carbon emission audits and environmental facility operation audits. It provides methodological insights into designing multi-stakeholder environmental governance systems.