1. Introduction

Virtual Reality (VR) has become an increasingly important tool in architectural design, especially in the context of user experience and spatial understanding. Traditionally, stakeholders involved in the design process (that is, investors, designers, or future users) relied on two-dimensional drawings, static 3D views, or physical models to evaluate spatial proposals. However, these methods often fell short in conveying accurate perceptions of scale, proportion, and spatial relationships. The introduction of immersive visualization tools, particularly mobile-based VR, offers a cost-effective and widely accessible means to experience an unbuilt environment from a human perspective. At the same time, the growing coverage of VR in popular media illustrates its rising cultural and professional relevance in the architectural domain [

1,

2].

This paper investigates the application of smartphone-powered VR in residential architectural design using Building Information Modeling (BIM) software and mobile VR glasses. The research makes an attempt to evaluate the effectiveness of mobile-based VR in facilitating occupant-centric and sustainable design decisions in residential architecture. In particular, it investigates how smartphone-powered immersive VR affected users’ spatial understanding, decision-making, engagement, and comfort when applied in early-stage design reviews for residential architecture. The study explores the usability of mobile VR both during collaborative sessions with architects and in independent, home-based use scenarios outside professional environments. This is the reason why relatively simple mobile glasses were used, enabling the participants to continue the immersive experience in their private homes. While VR applications in architecture have been studied in various experimental and professional settings, little attention has been given to its use in non-professional contexts, such as private homes. Broader reviews confirm the relevance of VR in education, conceptual design, and industry-wide adoption trends [

3,

4,

5], yet its application in small-scale residential architecture remains scarce. This study addresses that gap by exploring how mobile VR can extend beyond collaborative sessions with architects to independent, home-based use by residential clients.

To clarify the scope of analyses, the following research questions were formulated:

To what extent does immersive VR facilitate stakeholders’ comprehension of spatial layout, room proportions, and circulation within single-family residential projects?

What are the usability, intuitiveness, and comfort perceptions of non-expert users when interacting with mobile VR walkthroughs?

How does the use of smartphone-based VR affect user participation and design decision-making compared to traditional 2D documentation?

These questions aim to assess both the cognitive value of VR in design communication and its practical contribution to minimizing design errors and aligning outcomes with user expectations.

The study focuses on ten single-family house projects developed in Poland between 2023 and 2025, involving twenty-three investors and future users (individuals and couples). It explores how immersive walkthroughs influenced their spatial comprehension, supported design decision-making, and reduced the need for revisions. Because of the limited size of the study group, the research should be treated as a pilot study preceding further comprehensive analyses on the subject.

The digital building models were developed using BIM software and subsequently integrated into immersive VR environments. Each model included parametric metadata for architectural components such as walls, floors, roofs, windows, doors, and interior furnishings, capturing properties such as materials, thicknesses, and surface textures. Minor design modifications identified during immersive walkthroughs were implemented in real time during interactive design sessions, whereas major spatial or structural changes were introduced later following technical coordination.

By presenting a practice-based methodology supported by user feedback, the study contributes to the broader discourse on digital tools in architecture, with emphasis on accessibility, realism, and communication efficiency. It also reinforces the idea of sustainable design by improving the comfort and well-being of future building occupants. Its added value stems from real-life, contemporary architectural practice of several design studios in Poland.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Virtual Reality and Building Information Modeling in Architecture

Recent advancements in the integration of BIM and VR have significantly enhanced the ability of such environments to communicate both spatial and technical data to non-expert users and to convey detailed architectural information beyond mere geometry. In addition to enabling realistic walkthroughs, these systems allow stakeholders to interact with digital buildings in ways that support informed, user-centered design decisions [

1,

2,

3]. Virtual Reality technologies offer new ways to visualize and interact with spatial designs throughout the entire project lifecycle and may be applied to enterprises of different complexity, like single-family houses, large-scale urban transformation projects [

6], or historical buildings [

7].

Early research by Whyte [

8] emphasized the cognitive impact of immersive environments on architectural thinking, showing that VR changes not only how designers perceive space, but also how they explore and communicate ideas. The study highlighted that immersive media introduces alternative design workflows, allowing users to “inhabit” yet-unbuilt environments and reflect on form, proportion, and functionality from a human-scale perspective. This established VR not merely as a visualization tool, but as a medium capable of shaping design cognition and collaboration between people involved in the design process.

Shehadeh [

6] shows that embedding BIM data into immersive platforms facilitates real-time data accessibility and multidisciplinary coordination, enabling architects and clients to interact with layered building metadata, such as material specifications, thermal properties, and spatial constraints, directly within a VR walkthrough. Coppens et al. [

9] demonstrate how parametric modeling tools, when coupled with immersive interfaces, allow users to dynamically modify geometric parameters in VR while simultaneously observing the effects on spatial logic and structural behavior. Azarby and Rice [

10] found that eye-level immersive VR (IVRIE) significantly improved spatial perception and influenced design decision-making, compared to desktop VR setups, highlighting the cognitive advantages of full immersion over semi-immersive systems.

With the development of more accessible VR tools, research has broadened to examine not just spatial perception but also practical applications and learning outcomes. Subsequent studies have explored the integration of VR with other technologies to enhance real-world implementation. For example, Wang et al. [

11] demonstrated how combining Virtual and Augmented Reality with BIM enables real-time site coordination and error prevention in large-scale industrial construction projects in the liquefied natural gas industry. Integrating AR/VR into BIM workflows enhances the precision of onsite decision-making and reduces miscommunication between stakeholders. This integration is increasingly relevant in architectural contexts where real-time data, construction logistics, and user experience intersect [

4,

12].

From a user-centered perspective, VR also plays a key role in improving spatial comprehension among non-experts. Tuker and Tong [

13] compared the effectiveness of three different methods, namely physical field trips, VR simulations, and video walkthroughs, in helping participants to understand complex building layouts. Their findings showed that immersive VR experiences enhanced users’ ability to recall spatial relationships and organization, especially in large or unfamiliar buildings. This suggests that VR is not just an efficient substitute for physical site visits but may outperform traditional reconnaissance in terms of spatial memory and orientation.

Educational aspects have also benefited from VR integration. Kraus et al. [

14] demonstrated that VR notably enhances understanding of complex construction details among novice users, combining greater enjoyment with improved learning performance when compared to traditional 2D instruction. Furthermore, Monteiro et al. [

15] compared spatial knowledge gains from VR-based navigation versus real-world movement in a controlled maze task. Although both modes yielded similar time efficiencies, behavioral differences emerged, indicating that virtual environments can support spatial learning and that further work is needed to investigate these differences [

3,

16].

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that VR became more than a visualization tool, especially when integrated with data-rich environments like BIM. It has evolved into a multi-dimensional tool in architecture and construction, enhancing cognition, supporting coordination, and strengthening participatory design processes. What is more, VR allows stakeholders to engage with the building environment in ways that are spatially, visually, and functionally coherent [

11,

15,

17].

2.2. Spatial Perception and Cognition in VR

Spatial perception plays a critical role in architectural decision-making, particularly in the early design stages, where abstract representations must be translated into an understanding of physical space. Virtual Reality has emerged as a valuable tool in this context, offering users a first-person perspective of unbuilt environments. Numerous studies confirm that immersive VR environments significantly enhance users’ ability to comprehend proportions, distances, and layout relationships—especially among laypersons with limited technical background [

18].

For instance, Kuliga et al. [

10] conducted a comparative study between real and virtual walkthroughs in a university building and demonstrated that VR can provide a similarly effective spatial experience, with users reporting strong alignment between their perceptions in both environments. Similarly, Pausch et al. [

19] emphasized the importance of scale immersion for non-expert users, concluding that human-scale experiences in VR enable better comprehension of spatial hierarchies and circulation flows (i.e., the way people move through and navigate the building) compared to two-dimensional drawings. This has been further confirmed in immersive architectural simulations that demonstrated how spatial decision-making can be improved when users inhabit virtual environments [

20,

21].

Visual parameters of the VR system, particularly the field of view (FOV), have also been shown to directly influence spatial cognition. Grinyer and Teather [

22] demonstrated that narrower FOVs impair performance in object tracking and orientation tasks, reducing users’ confidence in estimating distances and room proportions. Lin et al. [

23] further investigated the effects of FOV on presence, enjoyment, memory, and simulator sickness, confirming that wider fields of view correlate positively with presence and spatial understanding. In a comprehensive review, Renner et al. [

24] analyzed over a decade of studies on egocentric distance perception in VR, concluding that users often underestimate distances in virtual settings due to visual and proprioceptive dissonance.

Augmented and virtual reality systems with wide-FOV capabilities have been proposed as a way to mitigate these perceptual limitations. Ren et al. [

25] showed that wider visual angles increase task awareness and spatial immersion, allowing users to more accurately judge room dimensions and functional zones. Steinicke et al. [

26] added that calibrating FOVs in head-mounted displays can dramatically alter users’ perception of realism, which is especially critical in architectural applications where trust in spatial configuration is essential. Moreover, Creem-Regehr et al. [

27] explored the cognitive consequences of restricted FOV conditions and found a marked decrease in users’ accuracy when estimating distances. This has important implications for VR-based architectural visualization, where default visualization settings often exaggerate perspective angles, potentially distorting spatial comprehension [

28].

These studies emphasize that the effectiveness of VR as a spatial cognition tool depends not only on the immersive content but also on the technical calibration of the display system, particularly FOV parameters. For architectural applications, especially involving residential clients, the alignment of visual realism with correct perception is vital for ensuring that spatial decisions are both informed and intuitive.

2.3. Mobile-Based VR and BIM + VR

While much attention has been given to high-end, tethered VR systems in architectural contexts, mobile-based VR solutions offer an accessible and scalable alternative that integrates seamlessly into everyday workflows. Tools such as BIM + VR or BIM-empowered platforms (e.g., BIMxAR) facilitate immersive interaction with architectural models on standard smartphones, using lightweight viewers without requiring specialized hardware [

29,

30]. In parallel, advances in low-cost optical metrology, such as structured-light scanning and calibration methods [

3], contribute to generating accurate 3D environments that can be directly integrated into mobile VR platforms.

Previous studies have demonstrated that Historic Building Information Modeling (HBIM) models, rich in parametric and architectural metadata, can be effectively ported into mobile VR/AR contexts, enabling heritage visualization and interactive learning on portable devices [

31]. This approach has been further expanded through the development of AR-enhanced mobile platforms that integrate BIM data to improve comprehension of architectural sections, showing that even mobile experiences can enhance spatial learning and user understanding [

32].

In parallel, other research highlights the importance of optimizing mobile VR for usability and comfort. Techniques such as field-of-view (FOV) reduction and depth-of-field adjustments have been shown to significantly mitigate motion sickness [

33]. Studies evaluating VR-based design review systems confirm their effectiveness in supporting architectural visualization for single-family residential design, while immersive design presentation tools for mobile VR have demonstrated positive effects on users’ cognitive load and decision-making [

13,

29].

Importantly, recent studies highlight the role of integrated BIM + VR workflows in improving the clarity, accuracy, and efficiency of collaborative design review processes. Such integrations have been shown to support stakeholders’ engagement and communication, particularly in early design phases where critical decisions about space usage and layout are made [

34,

35]. By connecting BIM metadata with real-time immersive environments, users (both professionals and laypersons) gain a deeper understanding of spatial configurations and construction logic, which improves the overall decision-making process [

17,

36].

Despite these encouraging findings, empirical research focused specifically on small-scale residential architectural contexts remains limited. To address this gap, the present study evaluates user experiences, design decision-making, and perceived comfort across ten single-family house projects using BIM model-powered mobile VR walkthroughs. An additional contribution of this study lies in documenting design changes resulting from user feedback during VR walkthroughs (described in

Table 1 and

Section 4.12), which is rarely reported in previous literature on VR in residential architecture. While previous studies have examined the use of VR for design communication and spatial evaluation in controlled or professional settings [

37,

38], relatively little research has focused on the adoption of smartphone-based VR in non-professional environments, such as private homes. Early works on mobile VR have demonstrated its potential for on-site or experimental scenarios [

39], and some recent studies have applied VR to support citizen participation in domestic contexts [

40]. However, these approaches remain scarce in the domain of residential architecture. This study, therefore, addresses a gap by exploring how mobile VR can extend beyond collaborative sessions with architects to independent, home-based use by residential clients.

3. Materials and Methods

Twenty-three individuals (12 men and 11 women), including couples, participated in the study as stakeholders engaged in the architectural design of single-family homes. All participants were future residents of the proposed houses and represented a wide age range spanning three generations. This demographic diversity reflects the potential of contemporary technologies such as virtual reality to support inclusive engagement across different age groups and varying levels of digital proficiency.

The study focused on ten single-family residential projects handled between 2023 and 2025 by an architectural practice in Lublin, Poland. Each design was developed using advanced 3D modeling and visualized through BIM + VR tools, enabling immersive walkthroughs and interactive design discussions. The houses featured traditional masonry construction with reinforced concrete elements, including structural slabs in prefabricated ribbed-block ceiling Teriva system or monolithic systems. Roof construction included gable and multi-pitched types, consistent with common regional residential typologies. The projects also varied in usable floor area, covering a broad range of spatial layouts to reflect the diverse needs of future occupants.

Given the immersive nature of the experience, aspects such as visual attention, peripheral awareness, and camera motion played a critical role in users’ perception. Studies have shown that visual distraction and attention dynamics significantly impact the effectiveness of VR environments [

41]. Furthermore, peripheral vision contributes to perceptual realism and spatial comprehension [

42], while target selection and tracking accuracy may be compromised under dynamic camera conditions [

43].

3.1. Survey Design and Methodology

To evaluate user experience and the perceived value of BIM + VR walkthroughs in the residential design process, a structured questionnaire was administered to all 23 participants (

Appendix A). The questionnaire comprised seven thematic sections, aligned with the analytical categories reported in

Section 4:

Demographic profile and prior VR exposure—age, role, background, and previous experience with VR.

Device usability and navigation—ease of use of the BIM + VR application, headset handling, orientation, and session duration.

Realism and immersion—perceived realism, presence, and first-impression reflections after the walkthrough.

Interior visual perception and material legibility—clarity of finishes, lighting, and visual readability of interior elements.

Perceived impact on spatial understanding—room proportions, circulation, and comprehension of layout relationships.

Influence on design decision-making—engagement, confidence in decisions, differences between 2D drawings and VR, and decision support.

Overall comfort and orientation—physical reactions (if any), comfort, and ability to maintain spatial orientation.

The survey also included open-ended questions for additional reflections and closed multiple-choice formats for consistency in analysis. The results offered insights into not only the cognitive impact of VR but also its practical comfort, independent usability, and role in stakeholder empowerment. To ensure transparency, the questionnaire was distributed at the end of each project cycle and completed independently by each participant or couple. All responses were anonymized.

3.2. Tools and Equipment

The immersive VR experience was facilitated through a BIM software with integrated VR visualization on mobile devices. The BIM models were developed using a professional architectural design environment and subsequently exported to a dedicated viewer platform optimized for smartphone-based VR walkthroughs.

The base computing system used for BIM model development was equipped with a 2.9 GHz quad-core Intel Core i7 processor, 16 GB of 2133 MHz LPDDR3 memory, and a Radeon Pro 460 graphics card with 4 GB of dedicated video memory. This setup provided sufficient performance for detailed 3D modeling, parametric editing, and real-time visual optimization before VR deployment.

To deliver immersive experiences, the finalized models were accessed via mobile VR cardboard glasses in the form of compact, lens-equipped viewers to hold smartphones. The choice of equipment was driven by mobility, accessibility, and ease of deployment outside professional environments. Unlike high-end tethered VR systems that require specialized hardware, extensive setup, or stationary use, cardboard-based viewers allowed stakeholders to engage with the architectural space at their own convenience, either at home, in the design studio, or directly on-site at the planned construction site. The portability of this approach proved particularly valuable in enabling personal reflection and spatial testing without the need for expert supervision.

Moreover, the flexibility of smartphone-based systems allowed participants to revisit the design multiple times, using familiar devices in environments that matched their intended future use. These conditions enabled more natural exploration of spatial configurations and contributed to a more context-sensitive understanding of scale, orientation, and functional layout. The importance of this flexibility was also reflected in the survey, which included specific questions regarding the duration and context of VR usage across different sessions.

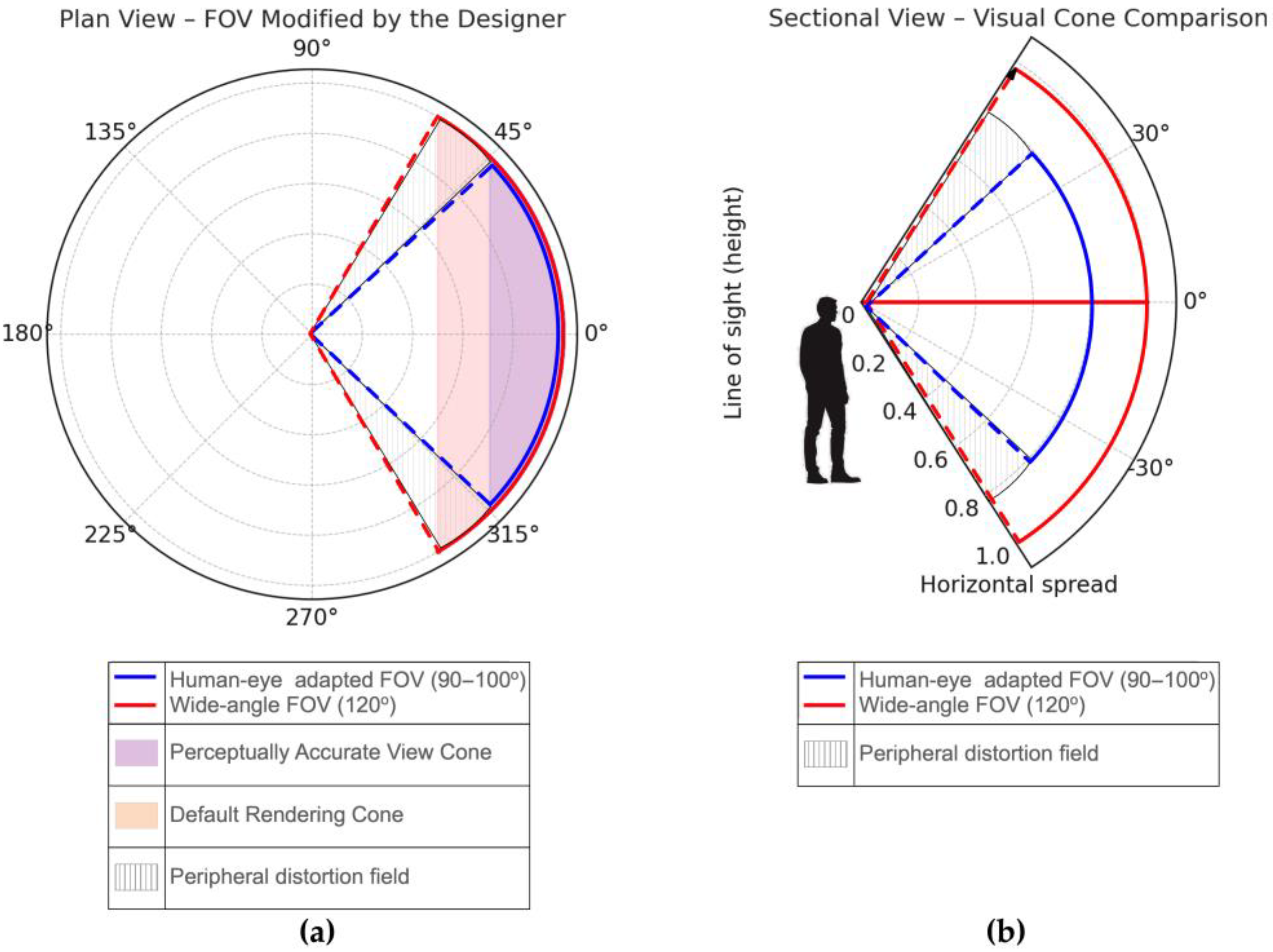

From a technical perspective, a key optimization step involved the manual calibration of the FOV within the virtual environment. Most architectural visualization tools apply exaggerated perspective settings by default, which can distort spatial proportions and depth perception. For this study, the FOV was adjusted to approximately 90–100 degrees, closely matching the natural horizontal visual field of the human eye, as shown in

Figure 1. This adjustment ensured that participants perceived scale and depth more accurately during immersive walkthroughs, thus reducing perceptual distortions and increasing the reliability of the spatial feedback they provided.

An extended FOV enhances immersion and breadth of view, but can compromise geometric fidelity and perception of spatial relationships, creating a “fish-eye” effect that can mislead users evaluating architectural layouts.

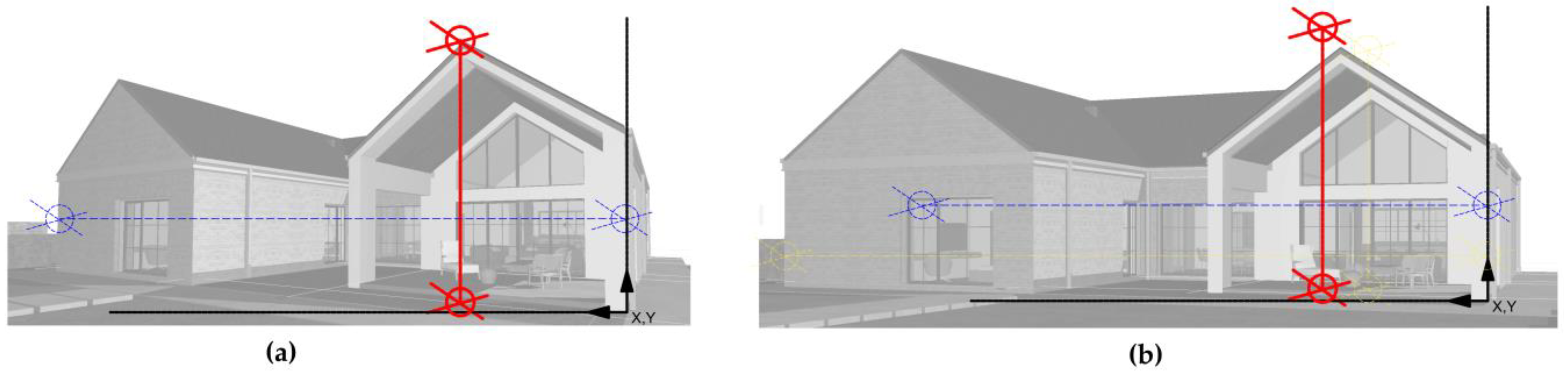

Figure 2 shows how different FOV settings impact the perceived geometry of architectural spaces in immersive visualization. Color-coded axes and guide lines are used to emphasize distortions in both width and height perception under different FOV conditions:

Red lines indicate the vertical reference axis and show how vertical exaggeration occurs in the extended 120° FOV. The vertical lines appear stretched, especially near the top of the gable wall, simulating increased ceiling height;

Blue lines represent the horizontal eye-level reference axis. They illustrate how the visual width of the façade expands unnaturally under wider FOV settings. This can lead to misinterpretation of room or window proportions;

Yellow lines (visible in the calibrated 95° FOV only) mark the natural visual envelope consistent with human binocular vision. These lines indicate more accurate spatial boundaries and are used to contrast the realistic perception with the distorted wide-angle view above.

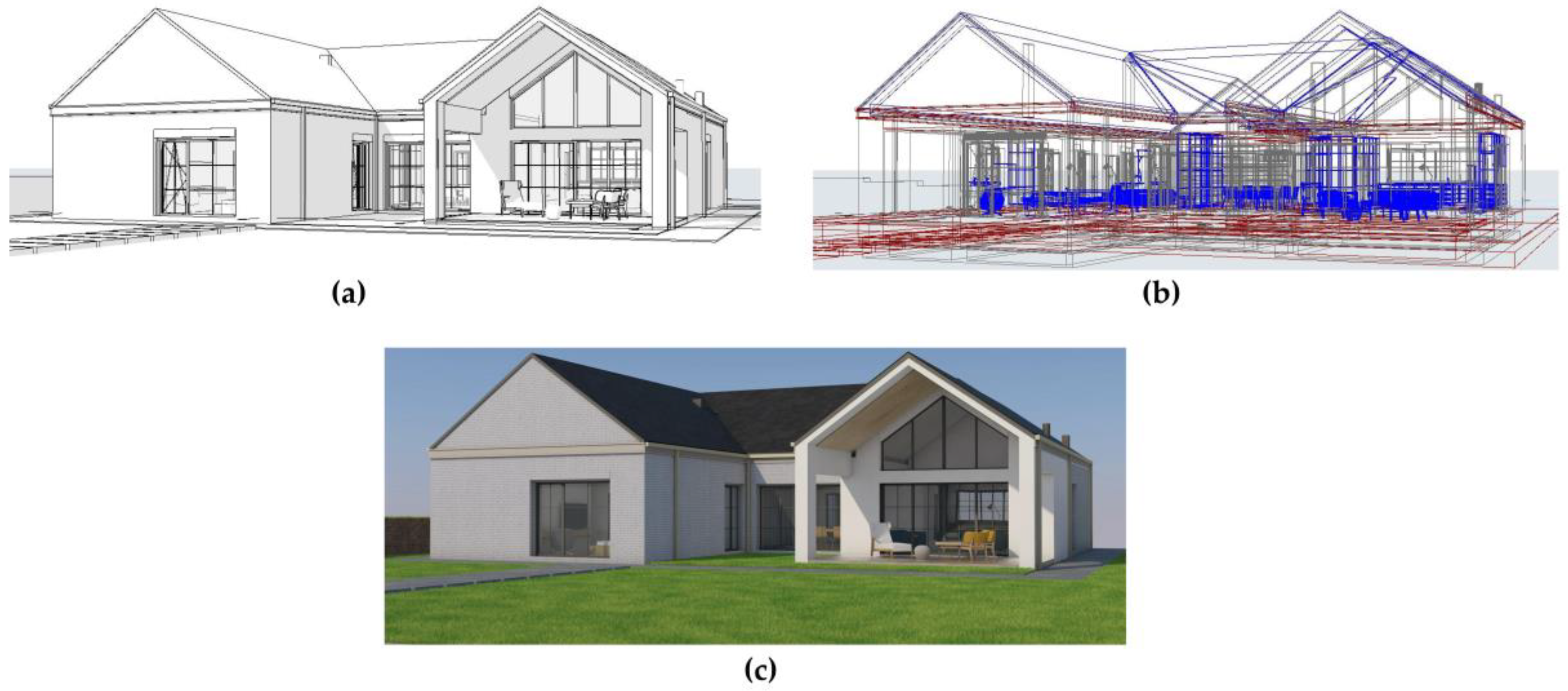

To ensure immersive walkthroughs were both perceptually accurate and information-rich, all architectural models used in this study were developed following a structured, three-stage BIM + VR preparation workflow (

Figure 3). This process began with basic volumetric and geometric modeling in a wireframe environment, progressed through full parametric modeling with metadata assignments in a BIM platform, and concluded with the export of VR-ready visualizations calibrated for human-scale viewing. The workflow included:

A wireframe architectural concept used to verify spatial logic and overall layout;

A parametric BIM model integrating multilayered data on materials, thicknesses, and system elements (structural, architectural, and interior);

A VR-rendered visualization adjusted for mobile display, with FOV calibration (~95°) to preserve spatial realism and reduce visual distortion during immersive sessions.

Participants experienced immersive virtual walkthroughs using smartphone-based VR headsets with stereoscopic rendering, enabling a realistic depth perception of the architectural environment. The virtual models were visualized using the BIM + VR application, which supported gyroscopic head tracking and dual-lens display compatible with low-cost VR viewers (e.g., cardboard-type devices). The scene was rendered in stereoscopic view, providing two slightly offset images (one for each eye) to simulate binocular vision (

Figure 4). Such visualization methods are compatible with low-cost mobile VR systems and do not require professional hardware or technical assistance. Each session included a guided and a self-directed exploration phase, during which users could freely examine both the interior and exterior of the proposed residential design.

The VR experience was accessed on participants’ personal smartphones (Android or iOS), placed into a VR viewer with lenses positioned to align with the stereoscopic display. Calibration settings ensured that the FOV and head rotation matched realistic proportions, particularly for sessions 4–10, where optimized FOV settings were implemented. Each participant was presented with their residential project in the VR environment during the conceptual or early technical design phase.

4. Results

This section presents the results of a structured survey conducted among 23 private investors who participated in immersive virtual walkthroughs of ten single-family residential projects using smartphone-based VR. The survey was administered electronically through an online form accessible on both desktop and mobile devices, ensuring flexible participation. The collected data were organized into seven thematic categories to reflect the full scope of the user experience and technology evaluation, as was described in

Section 3.1. Visual summaries of the quantitative results are provided in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14.

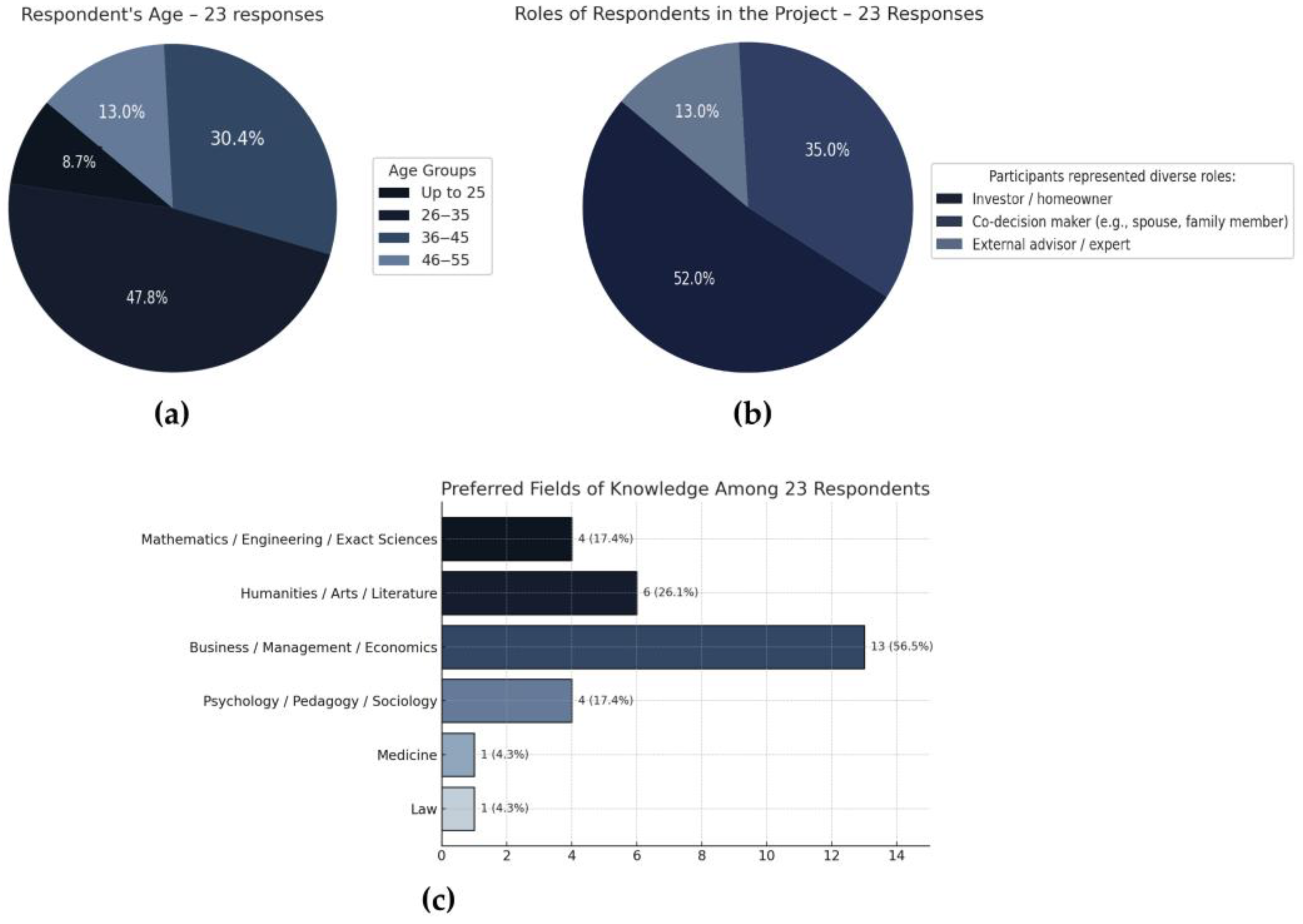

4.1. User Demographics and Stakeholder Profiles

Before examining the effects of mobile-based VR on design perception, the survey assessed participants’ demographic characteristics and background knowledge. As illustrated in

Figure 5a, the age distribution shows that 47.8% of respondents were between 26 and 35 years, 30.4% were aged 36 to 45, 13.0% were 46 to 55, and 8.7% were under 25. The majority of respondents were in an age group typically active in private investment or professional decision-making roles.

Regarding their involvement in the project (

Figure 5b), over half (52.0%) identified as the main investor or homeowner, while 35.0% participated as co-decision makers (such as spouses or family members) and 13.0% were external advisors or experts. This confirms that the feedback represented both direct clients and individuals indirectly involved in the design process.

In terms of intellectual and educational background (

Figure 5c), a significant portion of respondents (56.5%) declared a primary interest in business, management, or economics. Additionally, 26.1% preferred humanities, arts, or literature, while 17.4% indicated interests in both technical disciplines (mathematics/engineering) and social sciences (psychology/sociology). Smaller proportions represented medicine (4.3%) and law (4.3%). This diversity suggests that the survey group brought a range of cognitive perspectives and professional expectations into their VR experience.

Figure 5.

Respondent demographics and stakeholder profiles: (a) age distribution; (b) project roles; (c) educational/professional background.

Figure 5.

Respondent demographics and stakeholder profiles: (a) age distribution; (b) project roles; (c) educational/professional background.

4.2. Previous Exposure and Frequency of VR Use

A majority of the respondents (65.2%) had no previous experience with VR tools before this study, while 34.8% reported having used such technology at least once (

Figure 6a). This suggests that for most participants, the immersive walkthrough constituted a novel experience. Only 17.4% had used such devices multiple times, and 21.7% had tried them once (

Figure 6b). A significant 60.9% of participants had never used cardboard-based VR, confirming a generally low familiarity with immersive visualization tools in residential design contexts.

In terms of device types, 82.6% of participants used cardboard headsets provided by the architect. Other cardboard viewers were used by 8.7%, while plastic headsets (e.g., Meta Quest) accounted for 4.3%. Only one participant (4.3%) did not use any headset during the evaluation. These results highlight the practicality and accessibility of low-cost smartphone-based solutions in architectural practice (

Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

Experience with Mobile VR: (a) ease of use of the BIM + VR application and viewer; (b) duration of each VR session experienced by participants; (c) degree of independence in using VR without technical assistance.

Figure 6.

Experience with Mobile VR: (a) ease of use of the BIM + VR application and viewer; (b) duration of each VR session experienced by participants; (c) degree of independence in using VR without technical assistance.

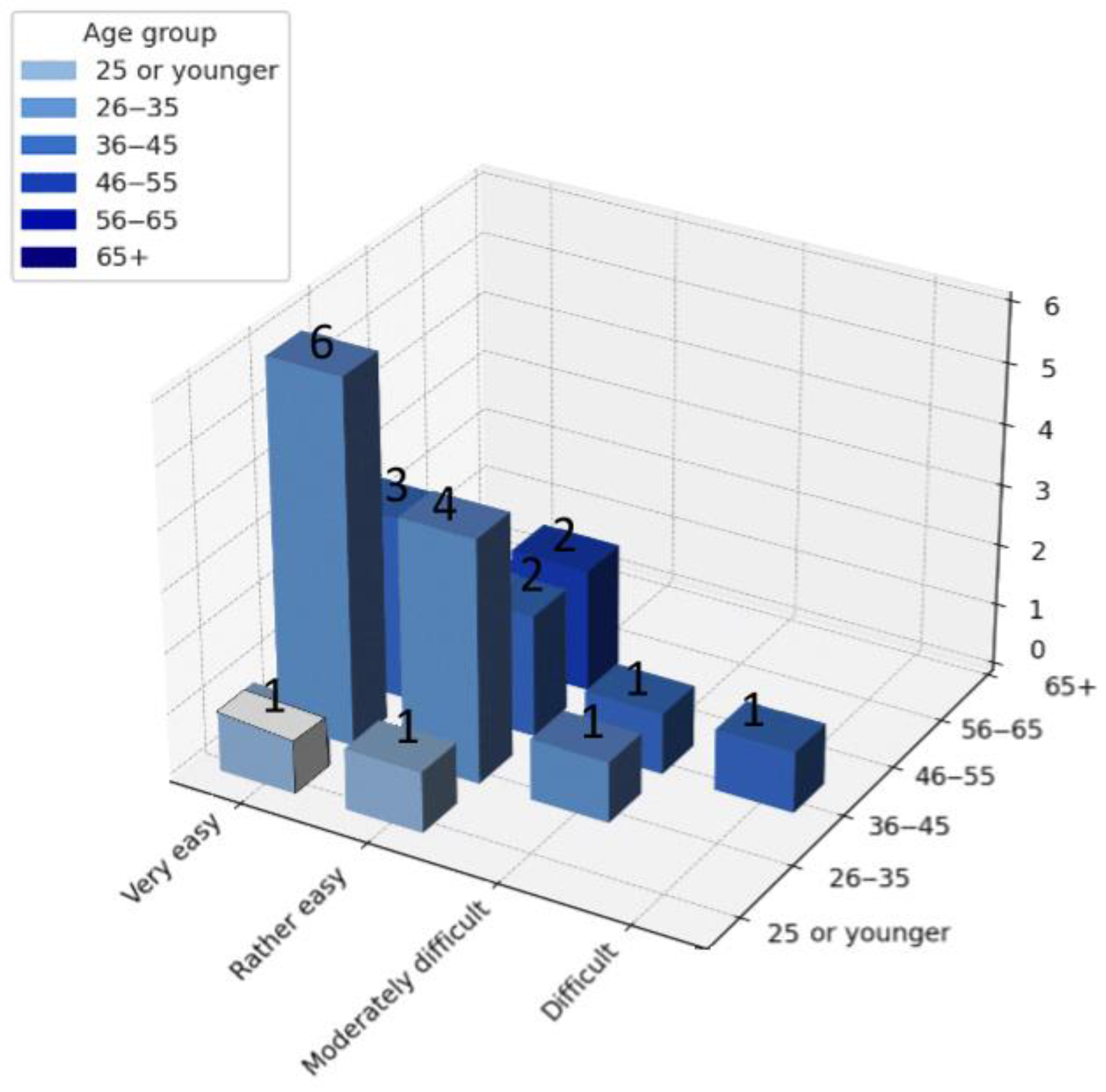

4.3. Comfort, Ease of Use, and Navigation

The comfort level of using mobile VR goggles is presented in

Figure 7a. Among the 23 respondents, 34.8% rated the experience as very comfortable, another 34.8% as rather comfortable, 17.4% remained neutral, and 13.0% found the use of VR rather uncomfortable. Notably, none of the participants marked the experience as “very uncomfortable,” suggesting a generally positive or at least tolerable user experience.

As shown in

Figure 7b, participants evaluated the ease of using the VR application on smartphones or tablets. A combined 86.9% found the application either very easy (47.8%) or rather easy (39.1%) to operate. Only 8.7% found it moderately difficult, and a minimal 4.3% considered the interface difficult. This indicates that the technological barrier to entry for mobile-based VR applications is low, even among first-time users.

Navigation ability within the virtual environment is depicted in

Figure 7c. A majority of 56.6% reported being able to explore the virtual house without difficulty, while 39.1% navigated with some difficulty. Only 4.3% stated that they were unable to navigate freely. It confirms that smartphone-based VR systems are generally accessible, though some users may benefit from introductory guidance or simplified controls.

Figure 7.

Perceived design impact of the VR experience: (a) Better understanding of spatial relationships through VR; (b) Influence of VR sessions on actual design decisions; (c) Reduction in design-related doubts and uncertainties due to immersive walkthroughs.

Figure 7.

Perceived design impact of the VR experience: (a) Better understanding of spatial relationships through VR; (b) Influence of VR sessions on actual design decisions; (c) Reduction in design-related doubts and uncertainties due to immersive walkthroughs.

When examined by age group (

Figure 8), the 26–35 demographic emerged as the main contributor across all categories, reflecting the age distribution of the sample. Within this group, most respondents indicated that VR was either “very easy” or “rather easy” to use, confirming a high level of digital literacy and adaptability to immersive technologies. Users aged 36–45 and 46–55 also reported predominantly positive experiences, although a few responses indicated minor usability challenges. Participants aged 25 or younger and above 55 years represented only a marginal share of the dataset, limiting the possibility of broader statistical conclusions in these groups.

Figure 8.

Perceived ease of use of the virtual walkthrough application on smartphone/tablet, presented by age group. Numbers 1 to 6 mean the number of the respondents.

Figure 8.

Perceived ease of use of the virtual walkthrough application on smartphone/tablet, presented by age group. Numbers 1 to 6 mean the number of the respondents.

Overall, the results indicate that ease of use was consistently high across age groups, reinforcing the potential of mobile-based virtual walkthroughs as an accessible and user-friendly medium in architectural design communication.

4.4. Physical Discomfort and Negative Reactions

The occurrence of physical discomfort among respondents during or after the VR experience is presented in

Figure 9. A majority of 69.6% declared no negative physical reactions, so the use of mobile-based VR goggles was generally well tolerated. However, 26.1% reported experiencing multiple symptoms over time, such as eyestrain or slight dizziness. An additional 4.3% selected “Other,” which may include isolated or mild effects not listed in the predefined options. Despite some discomfort, the short-term use of smartphone-enabled VR systems in architectural contexts is largely safe and manageable for most users.

Figure 9.

Occurrence of negative physical reactions to VR usage.

Figure 9.

Occurrence of negative physical reactions to VR usage.

Figure 10 illustrates the distribution of self-reported negative physical reactions to VR across different age groups. The majority of respondents did not experience discomfort while using VR, regardless of age. The dominant demographic, the 26–35 age group, accounted for the largest share of both symptom-free and symptom-reporting participants. Notably, negative symptoms such as dizziness or temporary discomfort were primarily reported among the 26–35 and 46–55 age groups, suggesting that both younger and middle-aged users may encounter adaptation challenges when interacting with immersive environments. Respondents aged 25 or younger and those above 55 years represented only a small fraction of the sample and therefore contributed minimally to the observed variation.

These findings indicate that while VR is generally well tolerated, the age structure of participants should be taken into account when implementing mobile-based VR tools in architectural practice. The results suggest that immersion and usability may be age-sensitive factors, which may influence both the design process and stakeholder engagement.

Figure 10.

Comparison of age distribution in relation to negative physical reactions to VR usage: (a) respondents’ answers (no; yes—multiple symptoms; other) depending on age; (b) the interaction between response categories and age groups. Numbers 1 to 6 mean the number of the respondents.

Figure 10.

Comparison of age distribution in relation to negative physical reactions to VR usage: (a) respondents’ answers (no; yes—multiple symptoms; other) depending on age; (b) the interaction between response categories and age groups. Numbers 1 to 6 mean the number of the respondents.

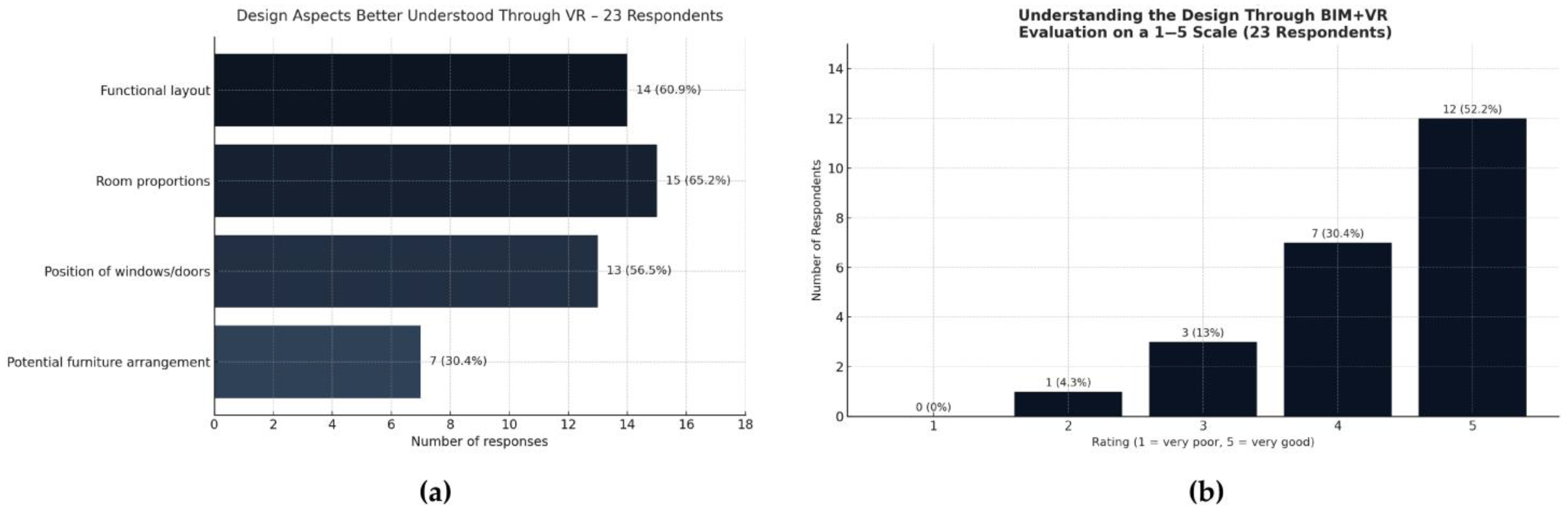

4.5. Spatial Understanding and Design Clarity Through VR

The participants were asked which design aspects became clearer through the use of VR. The most frequently indicated elements were room proportions (65.2%) and functional layout (60.9%), as presented in

Figure 11a. These were followed by the position of windows and doors (56.5%) and the potential furniture arrangement (30.4%). These results confirm that immersive visualization is particularly effective for conveying volumetric and functional characteristics of a space, while secondary aspects, such as furniture placement, may require further refinement or contextual support for full clarity.

Participants also rated their overall understanding of the project using the combined BIM + VR environment, on a 5-point scale (1 = very poor, 5 = very good), as shown in

Figure 11b. Over half of the respondents (52.2%) rated their understanding as very good, and 30.4% as good. Moderate ratings (3) were given by 13.0%, while only 4.3% selected a low rating (2), and none selected the lowest value (1). These responses suggest that immersive BIM-VR tools improve the clarity of design intentions compared to traditional visualization methods.

Figure 11.

Spatial understanding through VR: (a) Aspects of the architectural design; (b) Respondents’ ratings of their overall understanding of the design using BIM + VR on a 5-point scale (1 = very poor, 5 = very good).

Figure 11.

Spatial understanding through VR: (a) Aspects of the architectural design; (b) Respondents’ ratings of their overall understanding of the design using BIM + VR on a 5-point scale (1 = very poor, 5 = very good).

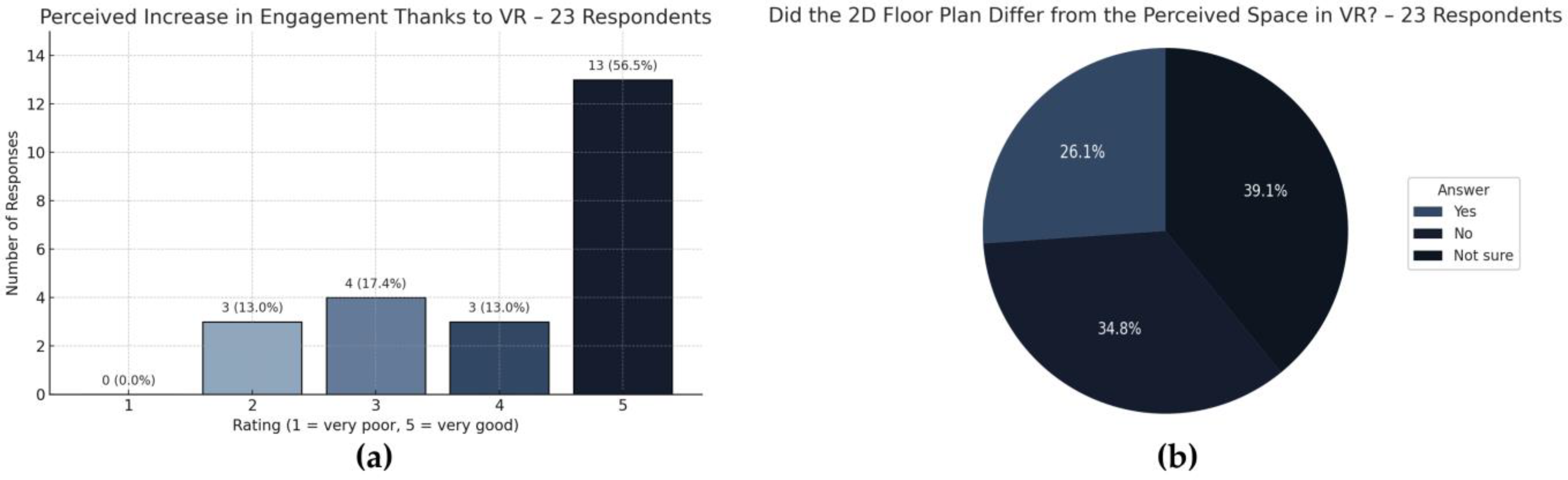

4.6. User Engagement and Spatial Perception Discrepancy

More than half of respondents (56.5%) rated the increase in their engagement with the design thanks to the use of VR as very high (rating 5), and an additional 13.0% selected rating 4 (

Figure 12a). Moderate improvement (rating 3) was noted by 17.4% of participants. Only 13.0% rated their engagement low (rating 2), while no one selected the lowest score (1). Therefore, immersive visualization has the potential to noticeably boost user involvement in the design process.

Figure 10b investigates the perceived discrepancy between the traditional 2D floor plan and the spatial impression generated in VR. While 34.8% of participants stated that the 2D plan matched their perception, 39.1% were not sure, and 26.1% reported that the space felt different when experienced immersively. Consequently, VR may reveal spatial relationships or proportions that are not easily grasped through conventional drawings.

Figure 12.

Perception and engagement: (a) Perceived increase in engagement thanks to VR; (b) Perceived difference between 2D floor plan and VR experience.

Figure 12.

Perception and engagement: (a) Perceived increase in engagement thanks to VR; (b) Perceived difference between 2D floor plan and VR experience.

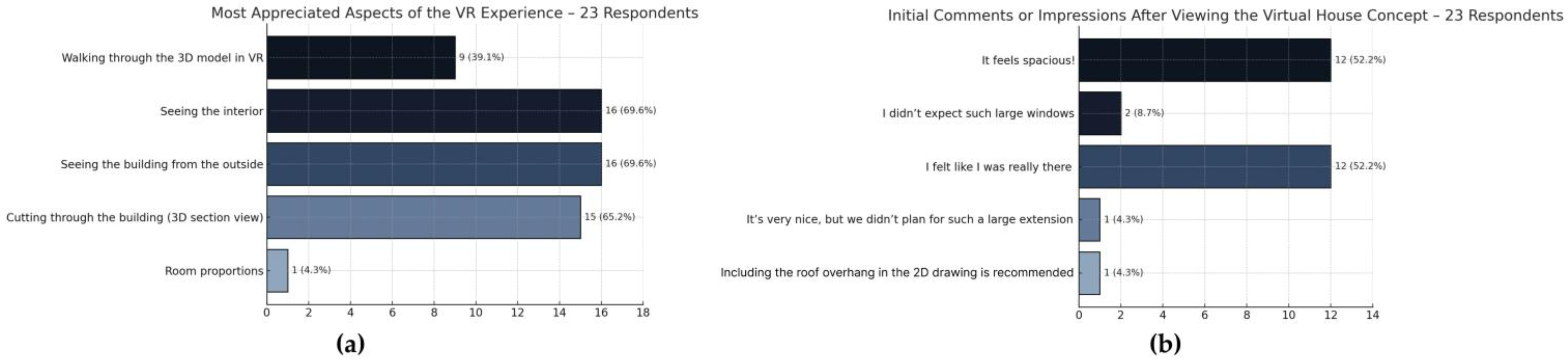

4.7. Most Valued VR Features and First Impressions

The most appreciated aspects of the VR experience were seeing the building’s interior (69.6%), seeing the building from the outside (69.6%), and 3D section views (cut-throughs) (65.2%). Walking through the 3D model was noted by 39.1% of respondents, while only 4.3% mentioned room proportions as a standout feature (

Figure 13a). These responses suggest that spatial immersion and global visualization of the architectural concept were more valued than isolated dimensional attributes.

In

Figure 13b, respondents’ initial impressions after viewing the virtual model are summarized. The most frequently reported comments were “It feels spacious” and “I felt like I was really there” (both selected by 52.2%). Other comments, though less common, referred to unexpected features (e.g., window sizes), changes in perception of scale, and mismatch with expectations. This emphasizes the emotional and perceptual depth enabled by immersive technology at early design stages.

Figure 13.

Most valued aspects and initial reactions: (a) Most appreciated aspects of the VR experience; (b) First impressions after viewing the virtual house in VR.

Figure 13.

Most valued aspects and initial reactions: (a) Most appreciated aspects of the VR experience; (b) First impressions after viewing the virtual house in VR.

4.8. User Reflections and Perceptual Insights from Open-Ended Responses

Immediately after completing the VR walkthrough, respondents were invited to share their first impressions through open-ended comments. A content analysis of these spontaneous reactions revealed several key themes:

Over half of the participants (52.2%) described the virtual house as “spacious”, highlighting the impact of immersive scale perception;

An equally large group (52.2%) reported feeling a strong sense of presence, with comments such as “I felt like I was really there”;

Others commented on unexpected spatial features, such as large windows (8.7%), or provided design-related feedback (e.g., “we didn’t plan for such a large extension”);

A few participants (4.3%) referenced the ceiling height and its effect on perceived room scale, which suggests that subtle vertical proportions were effectively communicated through VR.

Other issues noticed and expressed by the respondents were:

Trust and immersion: many participants reported stronger emotional engagement in VR compared to 2D floor plans;

Perceived scale: a common remark was that VR made spaces feel “real”, helping participants catch potential design issues early;

Technical impressions: users appreciated the ability to look around freely and highlighted the importance of realistic visual scaling.

4.9. Avoiding Costly Construction Changes

Almost half of the respondents (47.8%) agreed that VR helped to avoid costly changes during the construction phase by enabling early detection of design conflicts (

Figure 14). Meanwhile, 43.5% of participants were uncertain, indicating that the long-term economic benefits of VR may not have been fully observable at the design stage. Only 8.7% stated that VR did not contribute to reducing the cost of the changes. While the preventive potential of VR is widely recognized, its measurable impact may depend on subsequent implementation during the building process.

Figure 14.

Impact of VR on construction changes.

Figure 14.

Impact of VR on construction changes.

4.10. Reduction in Doubts and Increase in Project Engagement

As presented in

Figure 15a, more than half of the respondents (52.2%) strongly agreed that VR reduced their doubts regarding the project (rating 5), while 17.4% rated this effect as 4, and 30.4% as 3. No participants selected the lowest ratings (1 or 2). This highlights the role of immersive visualization in clarifying design intent and building confidence among users.

Figure 15b illustrates the impact of VR on overall project engagement, confirming that VR significantly enhances active participation in the design process. A majority of 56.5% rated their engagement at the highest level (5), with an additional 13.0% selecting 4 and 17.4% selecting 3. Only 13.0% of respondents gave a low rating (2), and none selected 1.

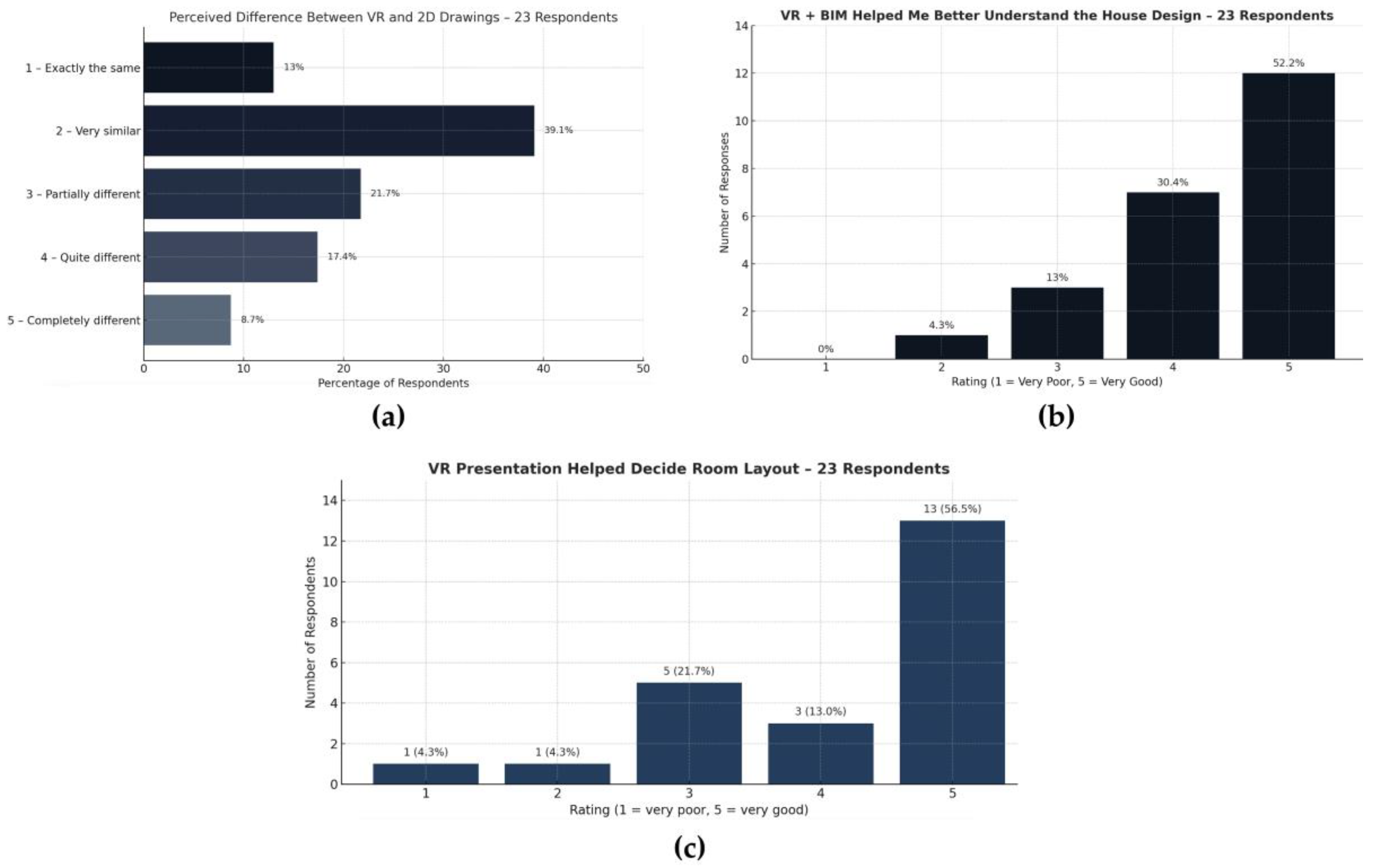

4.11. Comparison with 2D Drawings and Support for Design Decisions

Perceptions of differences between traditional 2D drawings and the VR experience varied, as illustrated in

Figure 16a. While 13.0% of respondents perceived them as the same and 39.1% as very similar, 21.7% found them partially different, 17.4% quite different, and 8.7% completely different. This indicates that VR often provides an enhanced or altered perception of spatial qualities compared to conventional representations.

In

Figure 16b, participants evaluated how VR combined with BIM supported their understanding of the house design. More than half (52.2%) rated this effect as very good (5), and 30.4% as good (4). Moderate ratings were given by 13.0%, while only 4.3% indicated limited impact (2). No respondents selected the lowest score (1), so it can be stated that BIM + VR synergy noticeably improved design comprehension.

Finally,

Figure 16c addresses whether VR presentations helped participants decide on room layouts. A majority (56.5%) strongly agreed (rating 5), and 13.0% agreed (rating 4). Another 21.7% rated the impact as moderate (3). Only 8.6% selected the lowest two ratings (1–2). These results underline the decision-supporting potential of immersive VR in early-stage planning.

4.12. Design Impacts

Immersive VR walkthroughs caused tangible design modifications in 8 out of the 10 projects studied. In total, 19 changes were identified and categorized into three groups:

Functionally significant adjustments (e.g., repositioning windows, altering room dimensions, modifying circulation paths);

Moderate layout changes (e.g., furniture rearrangements, clarifying access zones);

Cosmetic improvements (e.g., lighting mood, finish materials, perceived openness).

The comparative overview of all ten houses is presented in

Figure 17, where each column corresponds to subsequent design phases and rows represent individual projects. Several houses (e.g., Houses 3, 4, 6, and 9) were analyzed across two levels, highlighting vertical connections in addition to horizontal layouts. While most projects involved three phases, others (Houses 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10) underwent four distinct iterations, reflecting more intensive cycles of VR-based design refinement. A perspective layout combined with 3D sectional views was applied to clearly demonstrate how functional arrangements evolved across multiple floors and levels. This iterative structure emphasizes that VR served not only as a presentation tool but also as an active medium for guiding design evolution and user-informed decision-making.

In some projects, the floor area was significantly increased between the initial and final design stages (e.g., House 7 from 97 m

2 to 142 m

2; House 9 from 180 m

2 to 230 m

2), indicating that immersive walkthroughs revealed additional requirements and spatial needs of the users (

Table 1). The number of modifications varied from 5 to 19, with the highest levels recorded in House 3 and House 10. According to literature VR feedback most frequently resulted in functional layout changes, furniture rearrangements, and updates to the building massing [

44] (i.e., the overall volumetric form and proportions of the house). In several cases, it also influenced more complex revisions, such as roof geometry and exterior design.

5. Discussion

This study set out to examine the role of smartphone-based VR in residential architecture, with a focus on how immersive walkthroughs influence spatial understanding, design decision-making, and user engagement. The results demonstrated that VR not only enhanced clarity of spatial perception and improved communication between architects and clients but also triggered measurable design modifications across multiple projects. These findings position VR as more than a visualization tool, highlighting its potential as an active medium in iterative, user-driven design processes. The following discussion situates these outcomes within the broader context of architectural practice and research, addressing implications for technical calibration, user collaboration, and sustainable design.

5.1. Integration of VR in Architectural Practice

The results of this study align with the growing recognition of virtual reality as a valuable tool in contemporary architectural workflows. Previous research has documented the use of VR in large-scale and complex typologies, such as hospitals and urban planning [

11,

36,

45]. The present findings extend this discussion by demonstrating that even lightweight, smartphone-based VR solutions can deliver measurable benefits in the context of single-family housing. This confirms recent reports emphasizing the democratization of VR technology, which is increasingly available to both architects and private investors [

1,

2].

5.2. Impact on Spatial Understanding and Decision-Making

The survey revealed that VR improved the clarity of spatial perception. More than 60% of participants reported a better understanding of room proportions, functional layouts, and window and door placement (

Figure 11a). Similarly, over half of the respondents rated their overall comprehension of the design as very good when using BIM + VR (

Figure 11b). These results support existing evidence that immersive environments enhance users’ ability to detect potential design conflicts and validate architectural intentions early in the process [

22,

24]. Importantly, VR not only improved perception but also reinforced confidence in decision-making, reducing uncertainties typically associated with interpreting 2D drawings.

5.3. Technical Insights: The Role of Field of View

One of the unique contributions of this study concerns the role of the field of view in shaping user perception. Calibration of the FOV to approximately 95° produced a strong sense of realism while minimizing distortions, confirming prior findings by Renner [

24], Steinicke [

26], and Kellner et al. [

28]. Participants frequently commented that the VR walkthroughs felt “spacious” or that they “felt like really being there”, underscoring the importance of accurate scaling. These insights suggest that architects should pay careful attention to FOV settings when preparing VR models, as inappropriate calibration can misrepresent spatial proportions and compromise design communication.

5.4. User Engagement and Collaboration

The results also highlight the potential of VR to increase user engagement and strengthen collaboration between architects and clients. Over 56% of respondents rated their engagement as the highest possible (

Figure 13b), while qualitative feedback emphasized immersion and presence as distinctive qualities of the experience. These findings agree with previous studies on participatory design and user-centered workflows [

3,

5,

46]. Furthermore, they resonate with recent work showing that immersive collaboration platforms based on BIM + VR improve communication and decision-making in early design phases [

12,

17].

5.5. Design Modifications and Sustainability Implications

The comparative analysis of ten residential projects (

Table 1 and

Figure 17) demonstrates the tangible impact of VR on design outcomes. Immersive walkthroughs were the cause of design modifications in 8 out of 10 projects, generating a total of 19 changes. These ranged from functional adjustments (e.g., room dimensions, circulation paths), through moderate layout alterations (e.g., furniture placement, access zones), to cosmetic improvements (e.g., lighting mood, materials). In several cases, VR feedback also led to expansions of usable floor area. Such findings emphasize that VR not only facilitates visualization but actively drives iterative design refinement [

12,

29,

36]. From a sustainability perspective, this ability to identify and resolve issues before construction reduces costly modifications on-site and minimizes unnecessary material waste, supporting more efficient and resource-conscious building processes.

5.6. Limitations and Future Research

Despite these promising results, the study is limited by the relatively small sample size (23 participants) and its focus on single-family residential projects. Future research should investigate the long-term impact of VR-supported decision-making, for example, by surveying occupants after moving into the completed buildings to assess post-occupancy satisfaction. Comparative studies across different building types, such as offices, educational facilities, or healthcare environments, would further validate the presented findings [

4]. In addition, exploring the integration of higher-fidelity VR systems with haptic feedback or multi-user environments could expand the role of immersive technologies in collaborative design and sustainability-oriented workflows [

17,

36].

6. Conclusions

This study examined the use of smartphone-based VR in the context of single-family residential projects through a mixed-methods approach combining surveys, open-ended responses, and the analysis of ten case studies. The research was structured around three guiding questions concerning spatial comprehension, decision-making, and usability.

Firstly, the results indicated that immersive VR substantially improved stakeholders’ comprehension of architectural space. What is more, qualitative comments reinforced these findings. The outcomes show that VR effectively communicates volumetric qualities and allows users to anticipate potential design issues at an earlier stage.

Secondly, VR significantly influenced participation and decision-making. Walkthroughs increased user confidence, reduced uncertainty, and fostered dialogue between architects and clients. Importantly, VR also generated measurable modifications in the majority of the analyzed projects. These findings draw attention to VR as an active design tool that strengthens user-driven project development, rather than merely serving as a visualization medium.

Thirdly, the study confirmed the usability and comfort of smartphone-based VR for non-expert participants. At the same time, the research identified technical aspects (particularly the calibration of the field of view) as critical for maintaining perceptual accuracy, realism, and user comfort. This emphasizes the need for architects to treat VR not only as a communicative interface but also as a technical medium requiring careful preparation and testing.

Beyond these specific findings, the broader implications of this research accentuate the role of VR in supporting sustainable design. By enabling early detection of conflicts and more accurate alignment with user expectations, immersive walkthroughs help to reduce costly on-site modifications and minimize material waste. This positions VR as a tool not only for enhancing communication but also for advancing environmentally responsible and sustainable building practices.

While the study is limited to a relatively small sample and focused on single-family houses, it provides empirical evidence of the potential of smartphone-based VR in architecture. Future work should expand the scope to diverse building typologies, compare different VR platforms, and incorporate longitudinal post-occupancy studies to examine whether early VR-supported decisions transform into long-term satisfaction with the built environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.; methodology, R.S. and M.G.; software, R.S.; formal analysis, R.S.; investigation, R.S.; resources, R.S.; data curation, R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, R.S. and M.G.; visualization, R.S.; supervision, R.S. and M.G.; funding acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Lublin University of Technology, grant numbers FD-20/IL-4/022, FD-20/IL-4/030.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review by Institution Committee as the informed consent for publication was obtained from all identifiable human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and may be shared with the journal if required.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Age of respondent

☐ up to 25 years

☐ 26–35

☐ 36–45

☐ 46–55

☐ over 55

Which fields of knowledge interest you the most?

(You may select more than one answer)

☐ Mathematics/Engineering/Sciences

☐ Humanities/Arts/Literature

☐ Business/Management/Economics

☐ Psychology/Education/Sociology

☐ Other (please specify): ____________________________

Is this your first house project?

☐ Yes

☐ No

Your role in the project:

☐ Investor/homeowner

☐ Co-decision maker (e.g., family member)

☐ Other (please specify): ______________________________________

Have you had previous experience with Virtual Reality (VR) technology?

☐ Yes

☐ No

- 3.

How do you rate the ease of use of the BIM + VR app on smartphone/tablet?

☐ Very easy

☐ Rather easy

☐ Moderately difficult

☐ Difficult

☐ Very difficult

- 4.

Have you used the “VR mode” with cardboard goggles (cardboard or similar)?

☐ Yes, several times

☐ Yes, once

☐ No

- 5.

Were you able to move freely inside the house in BIM + VR?

☐ Yes, without problems

☐ Yes, but with some difficulties

☐ No

- 6.

How realistic did the VR space appear to you?

☐ Very realistic

☐ Rather realistic

☐ Moderately realistic

☐ Slightly realistic

☐ Unrealistic

- 7.

How much time in total did you spend viewing the BIM +VR model (throughout the design process)?

☐ up to 10 min

☐ up to 30 min

☐ up to 1 h

☐ over 1 h

- 8.

When was the BIM + VR model first used?

☐ Before receiving 2D drawings

☐ After reviewing 2D PDF drawings

☐ In parallel with 2D PDFs

- 9.

Which did you see first: the 2D PDF or the VR presentation?

☐ 2D PDF

☐ VR

☐ Both simultaneously

- 10.

Did the 2D drawing look different from the space seen in VR?

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Not sure

- 11.

How many changes did you make during the design process?

☐ up to 2

☐ up to 5

☐ up to 10

☐ more than 10

- 12.

Did VR help you better understand (you may select more than one):

☐ Functional layout

☐ Room proportions

☐ Window/door placement

☐ Potential furnishing

- 13.

After the VR presentation, did you suggest changes to the project?

☐ Yes

☐ No

- 14.

Did VR help avoid costly changes during construction?

☐ Yes

☐ No

☐ Hard to say

- 15.

Did you test the VR model on the actual site where the house will be built?

☐ Yes

☐ No

- 16.

Did you show your future house to other people?

☐ Yes

☐ No

- 17.

Whom did you show the project to? (If you answered “YES” to question 16)

☐ Immediate family

☐ Extended family

☐ Friends

☐ Others (who?): __________

- 18.

What did you like most in your BIM + VR experience?

☐ Walking inside the 3D model with VR glasses

☐ Seeing the interior

☐ Seeing the building from outside

☐ Viewing building sections (3D cut)

☐ Other (please specify): ____________________________

- 19.

Which aspects of the VR presentation should be improved?

☐ Smoother transitions between rooms

☐ More accurate furniture representation

☐ Clearer markings in the 3D model

☐ Other: ____________________________

- 20.

What additional elements would you like to see in the VR presentation?

☐ Different interior color schemes

☐ Daylight simulation

☐ More detailed furnishings

☐ Other: ____________________________

- 21.

What was your first reaction/comment after seeing the house concept?

☐ “It feels spacious!”

☐ “I didn’t expect such large windows.”

☐ “I felt like I was really there.”

☐ Other: ____________________________

- 22.

Additional remarks or reflections:

(Other insights, opinions, or ideas for the future)

..................................................................................

..................................................................................

- 23.

What floor area did you initially plan for the project?

☐ up to 100 m2

☐ up to 150 m2

☐ up to 200 m2

☐ up to 300 m2

☐ over 300 m2

- 24.

What is the final designed floor area of the house?

☐ up to 10 m2 smaller than planned

☐ up to 20 m2 larger than planned

☐ up to 20 m2 smaller than planned

☐ up to 20 m2 larger than planned

☐ more than 30 m2 larger than planned

☐ more than 30 m2 smaller than planned

- 25.

Does the final floor area differ from what was initially assumed?

☐ Yes, it is larger

☐ Yes, it is smaller

☐ No, it matches

Please rate the following statements on a scale of 1–5

(1 = very poor, 5 = very good):

- 6.1.

VR/BIM + VR helped me better understand the house design.

☐ 1 ☐ 2 ☐ 3 ☐ 4 ☐ 5

- 6.2.

Thanks to VR I felt more engaged in the project.

☐ 1 ☐ 2 ☐ 3 ☐ 4 ☐ 5

- 6.3.

The VR presentation helped me decide on the room layout.

☐ 1 ☐ 2 ☐ 3 ☐ 4 ☐ 5

- 6.4.

After the VR presentation I had fewer doubts about the project.

☐ 1 ☐ 2 ☐ 3 ☐ 4 ☐ 5

- 6.5.

I would like all architects to offer this kind of presentation.

☐ 1 ☐ 2 ☐ 3 ☐ 4 ☐ 5

- 6.6.

Realism of VR space compared to actual scale and proportions

☐ 1—very unrealistic

☐ 2—rather unrealistic

☐ 3—neutral

☐ 4—rather realistic

☐ 5—very realistic

- 6.7.

Ease of use of BIM + VR app on smartphone/tablet

☐ 1—very difficult

☐ 2—rather difficult

☐ 3—average

☐ 4—rather easy

☐ 5—very easy

- 6.8.

How different was the VR experience compared to 2D drawings?

☐ 1—identical

☐ 2—very similar

☐ 3—somewhat different

☐ 4—quite different

☐ 5—completely different

- 6.9.

VR helped me make better decisions and avoid costly changes

☐ 1—definitely not

☐ 2—probably not

☐ 3—hard to say

☐ 4—probably yes

☐ 5—definitely yes

- 6.10.

Thanks to VR I felt more engaged in designing the house

☐ 1—definitely not

☐ 2—probably not

☐ 3—hard to say

☐ 4—probably yes

☐ 5—definitely yes

☐ Other: __________

- 26.

Did you receive assistance from the architect while using VR?

☐ Yes

☐ No

- 27.

Which smartphone did you use? (Open answer)

☐ iPhone (Apple)

☐ Samsung

☐ Xiaomi

☐ Realme

☐ Other: ____________________________

- 28.

Which VR goggles did you use?

☐ Google cardboard (provided by the architect)

☐ Other cardboard

☐ Plastic (e.g., BoboVR)

☐ Other: __________

- 29.

How comfortable was using VR for you?

☐ 1—very uncomfortable

☐ 2—rather uncomfortable

☐ 3—neutral

☐ 4—rather comfortable

☐ 5—very comfortable

- 30.

Did using VR cause any negative effects?

☐ Yes → ☐ headache ☐ eye strain ☐ dizziness ☐ discomfort

☐ No

☐ Hard to say

Other: ____________________________

- 31.

How do you rate the overall cooperation process with the architect using VR/BIM + VR?

☐ 1—very poor

☐ 2—poor

☐ 3—average

☐ 4—good

☐ 5—very good

References

- Chow, A.R. How Virtual Reality Could Transform Architecture. 2024. Available online: https://time.com/6964951/vr-virtual-reality-architecture-meta-quest/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Murray, P. The Most Exciting Uses of Virtual Reality Right Now. 2016. Available online: https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/the-most-exciting-uses-of-virtual-reality-samsung-gear-oculus-google-tilt (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Samala, A.D.; Rawas, S.; Rahmadika, S.; Criollo-C, S.; Fikri, R.; Sandra, R.P. Virtual reality in education: Global trends, challenges, and impacts—Game changer or passing trend? Discov. Educ. 2025, 4, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noghabaei, M.; Heydarian, A.; Balali, V.; Han, K. A Survey Study to Understand Industry Vision for Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications in Design and Construction. arXiv 2005, arXiv:2005.02795. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz González, E.M.; Belaroussi, R.; Soto-Martín, O.; Acosta, M.; Martín-Gutierrez, J. Effect of Interactive Virtual Reality on the Teaching of Conceptual Design in Engineering and Architecture Fields. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehadeh, A.; Alshboul, O.; Taamneh, M.M.; Jaradat, A.Q.; Alomari, A.H.; Arar, M. Advanced integration of BIM and VR in the built environment: Enhancing sustainability and resilience in urban development. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorenza, J.; Rimella, N.; Calandra, D.; Osello, A.; Lamberti, F. Enhancing HBIM-to-VR workflows: Semi-automatic generation of virtual heritage experiences using enriched IFC files. DAACH 2025, 36, e00391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, J.; Nikolić, D. Virtual Reality and the Built Environment, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppens, A.; Mens, T.; Gallas, M.-A. Parametric Modelling within Immersive Environments: Building a Bridge Between Existing Tools and Virtual Reality Headsets. In Proceedings of the 36th eCAADe Conference—Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, Łódź, Poland, 19–21 September 2018; Volume 2, pp. 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarby, S.; Rice, A. Understanding the Effects of Virtual Reality System Usage on Spatial Perception: The Potential Impacts of Immersive Virtual Reality on Spatial Design Decisions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Truijens, M.; Hou, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Integrating Augmented Reality with Building Information Modeling: Onsite Construction Process Controlling for Liquefied Natural Gas Industry. Autom. Constr. 2014, 40, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Keung, C.; Suh, M.; Kim, T.W. Evaluation Framework for BIM-Based VR Applications in Design Phase. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2021, 8, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuker, C.; Tong, T. Comparing Field Trips, VR Experiences and Video Representations on Spatial Layout Learning in Complex Buildings. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.01968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M.; Rust, R.; Rietschel, M.; Hall, D. Improved Perception of AEC Construction Details via Immersive Teaching in Virtual Reality. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.10617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, D.; Wang, X.; Liang, H.-N.; Cai, Y. Spatial Knowledge Acquisition in Virtual and Physical Reality: A Comparative Evaluation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.07624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenani, S.; Durmazoğlu, M.Ç.; Gürer, E.; Kutlu, Z.G.; Dane, G. Designing in an Immersive Virtual Reality Environment: Implications for Design Education. In Extended Reality (XR Salento 2025), Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 15738, pp. 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podkosova, I.; Reisinger, J.; Kaufmann, H.; Kovacic, I. BIMFlexi-VR: A Virtual Reality Framework for Early-Stage Collaboration in Flexible Industrial Building Design. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 3, 782169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.W. Distance perception in virtual reality: A meta-analysis of the effect of head-mounted display characteristics. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2022, 29, 4978–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausch, R.; Proffitt, D.; Williams, G. Quantifying immersion in virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques (SIGGRAPH ’97), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 3–8 August 1997; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ângulo, A.; Vásquez de Velasco, G. Immersive Simulation of Architectural Spatial Experiences. In Knowledge-Based Design; Bernal, M., Gómez, P., Eds.; Blucher Design Proceedings: São Paulo, Brazil, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazzetti, L.; Banfi, F. Historic BIM for Mobile VR/AR Applications. In Mixed Reality and Gamification for Cultural Heritage; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinyer, K.; Teather, R.J. Effects of Field of View on Dynamic Out-of-View Target Search in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality Conference and 3D User Interfaces (IEEE VR), Christchurch, New Zealand, 12–16 March 2022; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.J.W.; Duh, H.B.-L.; Parker, D.E.; Abi-Rached, H.; Furness, T.A. Effects of Field of View on Presence, Enjoyment, Memory, and Simulator Sickness in a Virtual Environment. In Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 24–28 March 2002; pp. 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, R.S.; Velichkovsky, B.M.; Helmert, J.R. The Perception of Egocentric Distances in Virtual Environments—A Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2013, 46, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Goldschwendt, T.; Chang, Y.; Höllerer, T. Evaluating Wide-Field-of-View Augmented Reality with Mixed Reality Simulation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality Conference, Greenville, SC, USA, 19–23 March 2016; pp. 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinicke, F.; Bruder, G.; Jerald, J.; Frenz, H.; Lappe, M. Estimation of detection thresholds for redirected walking techniques. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2010, 16, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creem-Regehr, S.H.; Willemsen, P.; Gooch, A.A.; Thompson, W.B. The influence of restricted viewing conditions on egocentric distance perception: Implications for real and virtual environments. Perception 2005, 34, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellner, F.; Bolte, B.; Bruder, G.; Rautenberg, U.; Steinicke, F.; Lappe, M. Geometric Calibration of Head-Mounted Displays and Its Effects on Distance Estimation. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2012, 18, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrugo, A.G.; Gao, F.; Zhang, S. State-of-the-art active optical techniques for three-dimensional surface metrology: A review. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2020, 37, B60–B77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, Z.; Shaghaghian, Z.; Yan, W. BIMxAR: BIM-Empowered Augmented Reality for Learning Architectural Representations. 2022. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359814688_BIMxAR_BIM-Empowered_Augmented_Reality_for_Learning_Architectural_Representations (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Banfi, F. HBIM, 3D Drawing and Virtual Reality for Archaeological Sites and Ancient Ruins. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2020, 11, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, A.Z. Enhancing BIM Methodology with VR Technology. In State of the Art Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality Knowhow, 1st ed.; Mohamudally, N., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhanom, I.; Griffin, N.N.; MacNeilage, P.; Folmer, E. The Effect of a Foveated Field-of-view Restrictor on VR Sickness. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Atlanta, GA, USA, 22–26 March 2020; pp. 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.M.D.; Oyedele, L.O.; Demian, P.; Beach, T.H. A Research Agenda for Augmented and Virtual Reality in Architecture, Engineering and Construction. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 45, 101122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitbas, E.; Nowosad, A.; Engels, G. BIM-VR: Supporting Construction and Architectural Visualization through BIM and AR/VR: A Systematic Literature Review. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.12274. [Google Scholar]

- Heydarian, A.; Carneiro, J.P.; Gerber, D.J.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Hayes, T.; Wood, W. Immersive Virtual Environments versus Physical Built Environments: A Benchmarking Study for Building Design and user-built environment explorations. Autom. Constr. 2015, 54, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Klerk, R.; Duarte, A.M.; Medeiros, D.P.; Duarte, J.P.; Jorge, J.; Lopes, D.S. Usability studies on building early stage architectural models in virtual reality. Autom. Constr. 2019, 103, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safikhani, S.; Keller, S.; Schweiger, G.; Pirker, J. Immersive Virtual Reality for Extending the Potential of Building Information Modeling in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction Sector: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2022, 15, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moural, A.; Øritsland, T.A. User Experience in Mobile Virtual Reality: An On-Site Experience. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 4, 152–159. Available online: https://gispoint.de/fileadmin/user_upload/paper_gis_open/DLA_2019/537663016.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Guler, M.; Bekiri, V.; Baldauf, M.; Zimmermann, H.-D. Virtual Reality for Home-Based Citizen Participation in Urban Planning —An Exploratory User Study. In HCI in Business, Government and Organizations; Nah, F.F.H., Siau, K.L., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.J.; Bailenson, J.N. How Immersive Is Enough? A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Immersive Technology on User Presence. Media Psychol. 2016, 19, 272–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.J.; Beitner, J.; Võ, M.L.-H. The Importance of Peripheral Vision When Searching 3D Real-World Scenes: A Gaze-Contingent Study in Virtual Reality. J. Vis. 2021, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjalizo Alonso, F.; Kajastila, R.; Takala, T.; Matveinen, M.; Kytö, M.; Hämäläinen, P. Virtual Ball Catching Performance in Different Camera Views. In Proceedings of the 20th International Academic Mindtrek Conference (AcademicMindtrek ’16), Tampere, Finland, 17–18 October 2016; pp. 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, F.D.K. Architecture: Form, Space, and Order, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kuliga, S.; Thrash, T.; Dalton, R.C.; Hölscher, C. Virtual Reality as an Empirical Research Tool—Exploring User Experience in a Real Building and a Corresponding Virtual Model. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2015, 54, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umair, M.; Sharafat, A.; Lee, D.-E.; Seo, J. Impact of Virtual Reality-Based Design Review System on User’s Performance and Cognitive Behavior for Building Design Review Tasks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).