Abstract

Open Government Data (OGD) portals have the potential to be powerful tools for advancing progress toward the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In this paper, we examine the extent to which U.S. municipal open data portals support SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and a more complete set of sustainable city indicators, which we call SDG 11+. We focus on the 19 U.S. cities ranked in the 2024 Sustainable Cities Index. Amazingly, none of the cities had data that directly addressed SDG 11 indicators, showing a pressing need to link U.S. OGD portals with the SDGs. In terms of SDG 11 target areas, data were most available for transportation (31% of datasets) and green and public spaces (25% of datasets), though these databases often lacked demographic and equity details. Cities ranking highly on sustainability (New York, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C.) had far more such datasets available than low-ranked cities (Atlanta, Tampa, and Pittsburgh). We propose an expanded list of urban sustainability indicators (some within other SDGs) and recommend that cities emphasize coordination with the SDGs, usability, breadth of content, links with policy, timely updating, and greater disaggregation of data when managing OGD portals.

1. Introduction

The UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Agenda 2030) serves as a global framework for sustainability planning. Among its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), each with associated targets and indicators, SDG 11 addresses the challenges of sustainable urbanization [1]. Indeed, SDG 11 is at the core of Agenda 2030, linking 10 out of 17 SDGs, 30% of targets, and 39% of indicators [2]. However, with less than five years left to achieve the SDGs by 2030, global progress remains insufficient. This shortfall highlights not only weaknesses in data infrastructure but also fundamental issues in how progress is measured and tracked, for example, regarding which set of indicators is best for monitoring all dimensions of progress toward sustainable cities [3]. Under SDG 11, a sustainable city in 2030 is expected to offer an inclusive, safe, accessible, and affordable environment for all residents (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A Sustainable City in Agenda 2030 through the Lens of SDG 11.

According to the UN-sponsored Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development, a “data revolution” is necessary to monitor progress toward SDGs, hold governments accountable, and promote sustainable development, leading to “more empowered people, better policies, more informed decisions, and increased participation and accountability” [4], p. 6.

Municipal Open Government Data (OGD) portals have the potential to be powerful tools in advancing progress toward SDG 11. OGD refers to information from governments that is available to the public free of charge, can be reused without restrictions, and is platform-independent, machine-readable, and often de-identified [5,6,7,8]. Starting around 2009, many cities developed open data portals to enhance transparency, improve accountability, stimulate economic growth, encourage innovation, empower citizens, combat corruption, achieve environmental goals, and provide better public services [9,10]. But these portals are still evolving and have much room for improvement.

Previous research has not systematically examined how OGD can support SDG 11. Therefore, more empirical studies are needed to understand how OGD can effectively contribute to sustainable development at the city level, particularly in advancing Agenda 2030 and SDG 11. In this paper, we assess the extent to which open data portals in 19 U.S. cities relate to SDG 11 as well as a more inclusive potential list of urban sustainability indicators, which we call SDG 11+. We consider open data portals of all US cities ranked in the 2024 Sustainable Cities Index Report (SCI 2024), an independent, international rating of urban sustainability. First, we review whether the datasets accessible through keyword searches align with SDG 11. Second, we develop the SDG 11+ indicator list and determine the availability of OGD portal data for those more comprehensive metrics. Finally, we offer recommendations for improving open data portals to support SDG 11 and urban sustainability generally.

2. Background

2.1. Urban Sustainability Indicators

Urban sustainability indicators serve multiple purposes: systematic monitoring of social, economic, and environmental changes; early warning of problems; target setting; performance evaluation; and public information, education, and communication [11]. Because no single indicator can fully capture the complexity of urban sustainability, using a diverse set of indicators is necessary to reflect various dimensions.

Since the mid-1990s, many cities have implemented indicators to measure urban systems and benchmark their sustainability performance. Pioneering city-level initiatives in the U.S. include the Sustainable Seattle Indicators of Sustainable Community, which tracked 40 key indicators across environmental, social, and economic realms, the Jacksonville Quality of Life Progress Report, with over 50 indicators, and the Boston Indicators Project, which analyzes as many as 350 measures of civic well-being [12,13,14]. Other cities, including San Francisco and Portland, have incorporated sustainability indicators into planning documents and climate action strategies [15,16].

Similar frameworks exist globally, and the growing worldwide availability and quality of data make it possible for such indicator systems to advance sustainable development. Satterthwaite (2016) argues that the success of SDG 11 depends on the availability and accessibility of robust data [17]. Merino-Suam et al. (2020) surveyed urban sustainability indicators worldwide, identifying 2847 metrics in use [18]. The most common subjects are employment, green areas per capita, water consumption, air quality, income, waste generated, education, crime, poverty, and life expectancy.

The UN SDG framework utilizes targets (general areas of focus for each goal) and indicators (more specific metrics). These are intended to provide a basis for informed political decision-making by fostering public awareness of sustainability dimensions and guiding conceptualization of problems and solutions [19]. Ten targets and 15 indicators are associated with SDG 11. There are seven numerically labeled primary targets that we consider in this study, and three letter-labeled complementary or additional targets that track policy frameworks or implementation strategies rather than direct outcomes [20].

Developing globally applicable urban sustainability metrics is difficult. Verma and Raghubanshi (2018) reviewed 341 peer-reviewed articles on this topic and identified two types of obstacles: internal challenges inherent to indicator development (e.g., methodological flaws, lack of theoretical base), and external challenges such as data scarcity, policy inertia, and lack of consensus [21]. Thomas et al. (2021) examined 484 urban sustainability indicators sourced from 40 indices and found them inadequate for evaluating progress toward SDG 11, citing the absence of benchmarks, realistic targets, and disaggregated equity measures [22]. Simon et al. (2015) argue that no indicators of SDG 11 are universally important, relevant, and easy to report on in terms of data availability [23]. Drawing on experiences from cities in the Global South such as Kampala and Mumbai, Satterthwaite (2016) emphasizes that many local governments lack the resources or systems to collect neighborhood-level data on housing, infrastructure, and services—data that is essential for monitoring SDG 11 targets [17].

Valencia et al. (2019) specifically criticize the usability of Targets 11.5 and 11.b of SDG 11, which aim to reduce the harm of disasters [24]. They argue that the focus on disasters would divert attention from smaller but more frequent impacts that, cumulatively over time, may result in severe social and economic damage. In their view, Target 11.b and its indicators fail to address either the quality of policies or the effectiveness of their implementation [24]. Simon et al. (2015) criticize indicator 11.2 (the proportion of the population that has convenient access to public transport) [23]. They interviewed city officials from Gothenburg, Sweden, who consider the indicator to be of little relevance, and argue that this indicator should include topography, physical obstacles, and safety issues such as lighting and open paths [23].

Overall, many authors agree that urban sustainability indicators are a vital tool but that developing them is difficult due to (1) internal challenges such as methodological flaws and lack of theoretical grounding and (2) external challenges including data scarcity, policy inertia, and insufficient disaggregated equity measures [17,21,22,23,24]. Although SDG 11 represents a step forward toward such indicators, there is substantial room for improvement.

2.2. Open Data Portals of Cities

Open data is a trend in the urban planning world about which relatively little has been written. Having good data publicly available can help public officials, citizens, and the media evaluate progress towards local goals, state and federal targets, the SDGs, and other frameworks. It can also play an important educational role, especially if well-curated and accompanied by visualizations and user-friendly dashboards, and is highly useful to researchers, students, NGOs, and other public agencies.

An OGD portal serves as a one-stop shop for data consumers, empowering the public with access to a wealth of information. These sites often provide functions such as data format conversion, visualization options, and query endpoints [25,26,27]. In addition to the wide variety of information collected from citizens and institutions, modern OGD portals include features for learning about, requesting, mapping, displaying, creating, and converting published data (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sample OGD Portals of U.S. Cities.

Open data portals first appeared in the late 2000s and expanded rapidly through the 2010s and early 2020s. The U.S. federal government launched Data.gov in 2009, starting with just 47 datasets. Later that year, the Obama Administration issued the Open Government Directive, requiring agencies to release previously unreleased data within 45 days and providing concrete guidance for the nascent movement. The 2013 Open Data Policy further accelerated growth by mandating data inventories and public listings. By 2025 the portal hosted more than 300,000 datasets from over 100 agencies and attracted more than a million monthly pageviews [9].

At the municipal level, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and New York were early pioneers. Their websites were organized by categories such as transportation, environment, housing, and public safety, and provided visualization tools and downloadable files for users. As of 2025, over 140 OGD portals had been established in the USA, hosting more than 312,000 datasets [28].

Several examples illustrate how open data benefits residents in U.S. cities. New York City’s Restaurant Violations database allows users to search and view restaurant inspection results published by the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. That city’s Crash Mapper enables users to track traffic accidents so as to evaluate the impact of Vision Zero improvements on traffic safety. Similarly, San Francisco showcases open data through projects like the Property Information Map, which consolidates property, zoning, and permitting data into a single accessible platform. Seattle’s OGD portal includes Building Energy Benchmarking Data, which requires owners of buildings larger than 20,000 square feet to track and report annual energy performance. Users can coordinate this database with the city’s Building Emissions Performance Standard (BEPS), establishing greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets for building owners, so as to help the city achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 [29].

2.3. Impact and Criticisms of OGD

Ojo et al. (2015) argue that open data is one of the most impactful tools cities can offer to their citizens and communities, enabling influence across various areas—such as the economy, environment, and equity—as well as shaping policy [30]. Meuleman et al. (2022) find that countries with stronger OGD performance tend to achieve better sustainability-related governance, particularly in environmental outcomes, public participation, and transparency [31]. According to Ahlgren et al. (2016), OGD allows residents, local businesses, and organizations to analyze conditions, develop policy proposals, and evaluate civic action [32]. With this foundation, a wide range of unanticipated sustainable ideas, theories, and innovations emerge [32]. Such discussions highlight that open data is not only a technical resource but also a tool for advancing urban equity and sustainability. Drawing on frameworks such as Agyeman et al.’s (2003) concept of just sustainability, Harvey’s (2008) concept of the right to the city, and Taylor’s (2017) concept of data justice, equitable access to and use of OGD can be seen as central to realizing inclusive, sustainable urban development [33,34,35]. At the same time, Ruijer et al. (2020) emphasize that open data systems should be developed through active people-centered interactions in ways that encourage ongoing communication [36].

However, data access is never neutral politically, technologically, or socio-culturally. According to Johnson (2015) and Brandusescu (2017), questions of what information to collect, how to collect it, how to present it, and which analytical frameworks to apply impact its credibility, impact, and usefulness [37,38]. According to Kitchin (2013), open data can further empower the empowered and reproduce power imbalances [39]. Public sector data embeds a high degree of social privilege and values in terms of what data is generated, who it relates to, and whose interests a dataset represents and excludes.

Kitchin et al. (2015) argue that open data projects are complex socio-technical systems with diverse stakeholders and agendas [40]. After reviewing several open data projects, Helbig et al. (2012) reported that many of them were simple websites with miscellaneous data files and little attention given to user-friendliness, content quality, or user consultation [41]. The tendency of those in power to release information selectively, framed so as to trumpet strengths and hide weaknesses, is a common issue that many researchers and analysts face. Open data curators thus face challenges in presenting credible and relevant data insulated from partisan manipulation. On their part, users must consider the data in a broader context, take into account its provenance, and consider the interests of those who collected it to avoid being misled.

Harrison et al. (2012) and Lourenço (2013) argue that simply making data available does not necessarily lead to improved public governance and citizen empowerment [42,43]. According to Zurada and Karwowski (2011), users often find it difficult to analyze large volumes of data and draw meaningful conclusions [44]. Zuiderwijk and Janssen (2013) highlight that non-standardized data can lead to significant variation in terms of semantics, comparisons, and general schema [45]. The quality of data, portal organization, and design of search functions greatly affect users’ ability to discover relevant datasets and indicators.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Sources

For a sample of large U.S. cities oriented toward sustainable development, we chose the 19 municipalities ranked in the Arcadis’ Sustainable Cities Index 2024 report (SCI 2024). This list is part of a global convenience sample of 100 cities which Arcadis rated on 67 indicators across three dimensions of sustainable development: people (social), planet (environmental), and profit (economic) [46] (see Table 1). While other sustainability rankings exist with varying outcomes, the SCI 2024 is an independent, up-to-date international assessment that highlights a set of relatively high-performing U.S. cities (though by no means all; Portland, Austin, and Minneapolis, for example, are not represented).

Table 1.

U.S. Cities Appearing in the Arcadis Sustainable Cities Index 2024.

The cities in this sample varied greatly in size, ranging from 300,000 to 8.4 million. Geographically, they represent 14 U.S. States and the District of Columbia in all regions of the country. For our analysis, we used published data from the official OGD portals of these cities (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The Data Sources for the Study.

3.2. Data Search and Analysis for SDG 11

To examine whether portals contained data reflecting indicators of SDG 11, we focused on the seven numerical outcome-oriented targets of SDG 11 (11.1 to 11.7), along with their corresponding 12 indicators (11.1.1 to 11.7.2). We excluded the three letter-designated targets (11.a, 11.b, and 11.c) and their associated indicators (11.a.1, 11.b.1, and 11.b.2), as these targets are conceptually vague, inconsistently defined, and often lack measurable, quantitative indicators [20]. These also emphasize national-level linkages between urban, peri-urban, and rural areas—a scope that falls outside the city-level focus of this study.

To locate the datasets associated with indicators of SDG 11, we utilized a two-step online search strategy. First, we used exact wording from the indicators of SDG 11 as search terms in the internal search engines of portals to determine the number of datasets directly linked to SDG 11. Next, we searched for wording related to the narrative and target area to identify datasets indirectly associated with SDG 11. For example, to explore whether a portal contains datasets addressing affordable housing in line with the SDG 11 framework, we utilized its search engine with terms drawn from the indicator 11.1.1 of SDG 11, such as ‘inadequate housing,’ ‘informal settlements,’ and ‘population living in slums.’ We drew additional search terms from the narrative of the related target (11.1 of SDG 11)—‘upgrade slums,’ ‘basic services,’ and ‘affordable housing.’ A summary of the datasets for SDG 11 in 19 U.S. cities is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Search Results of Current SDG 11 Datasets of 19 U.S. Cities.

The search focused exclusively on datasets, rather than other types of documents, such as stories, maps, or reports. We excluded datasets not intended for regular updates and examined each dataset’s description and variables to determine whether it contained data relevant to the SDG 11 targets or indicators of interest. We categorized datasets into two distinct groups. ‘Datasets directly reflecting SDG 11′ were those in which the indicator of interest could be reached in one click. ‘Datasets indirectly reflecting SDG 11′ were those in which the indicator could be calculated from other fields in no more than three arithmetic operations. For example, for indicator 11.1.1 of SDG 11, we would look for data on the population living in inadequate conditions and the total population and then divide the former by the latter.

3.3. Development of SDG 11+

SDG 11 targets and indicators were the result of high-level political negotiations and often contain confusing language. Scholars have raised concerns about their clarity and relevance [23,24,47]. To determine how well open data portals support a broader and better defined set of urban sustainability indicators, we developed the SDG 11+ indicators based on (a) SDG 11 indicators that are well-focused and broadly quantifiable; (b) insights from the urban sustainability literature; (c) city-related targets and indicators from the other SDGs; and (d) other commonly available city indicators, including from regulatory and certification systems such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM), and International Standard 37120 (ISO 37120) [48] Sustainable Cities and Communities (see Table 4). Appendix A contains a detailed table comparing existing SDG 11 targets and indicators (shaded in grey) to proposed SDG 11+ targets and indicators, along with rationale for each.

Table 4.

SDG 11+ Urban Sustainability Targets and Indicators.

SDG 11+ indicators are well-focused and broadly quantifiable. For example, SDG indicator 11.1.1 is “the proportion of the urban population living in slums, informal settlements, or inadequate housing.” However, the terms “slums”, “informal settlements,” and “inadequate housing” are difficult to define and often carry culturally relative meanings. “Affordable housing” is a more widely used term. U.S. cities commonly calculate the percentage of households spending more than 30% of their income on housing (“cost-burdened households”) [49]. Globally, similar measures are used, such as income-to-rent and income-to-mortgage ratios and median house price-to-income ratios. Whereas none of the OGD portals contained datasets corresponding to the exact SDG 11 terminology, 15 of 19 returned datasets on cost-burdened households in response to a search on “affordable housing.” Thus, the SDG 11+ indicator for “affordable housing” based on the percentage of income spent on housing seems most reasonable.

The literature on urban sustainability has provided key insights for identifying relevant SDG 11+ indicators. For example, Ewing and Cervero (2017) demonstrated that greater urban accessibility, compactness, and reduced GHG emissions are associated with reduced vehicle miles traveled (VMT), and many North American jurisdictions are using this metric [50]. We therefore included ‘the percentage change in VMT annually’ as an SDG 11+ indicator. Another example is the Environmental Justice Mapping and Screening Tool, which identifies populations at higher health risk from living within 300 m of major roadways [51]. Meanwhile, the Health Effects Institute (2010) found that 30–45% of residents in large North American cities live within 300–500 m of major roads [52]. Therefore, we added the ‘% population living within 300 m of major polluters’ SDG 11+ indicator.

The SDG 11+ indicators also incorporate relevant city-related targets and indicators from other SDGs. As we mentioned, SDG 11 is linked to 10 of the 17 SDGs, covering 30% of all targets and 39% of all indicators [2]. Building on these insights, we examined sustainability-related topics such as poverty, food security, education, energy, equity, climate action, and water, aligning each with its corresponding SDG to integrate these diverse dimensions into the enhanced SDG 11+ framework. We included SDGs that address key aspects of urban sustainability not already covered in SDG 11 (Appendix A). For example, as noted earlier, the ‘percentage change in VMT annually’ indicator also relates to SDG 13 since it directly affects GHG emissions, car dependency, urban sprawl, and the use of public space for motor vehicles.

It is reasonable to include required regulatory datasets within OGD systems and SDG 11+ indicators. Many jurisdictions must now report air quality and GHG emission datasets to higher levels of government; these datasets are likely to become increasingly standardized worldwide. Other datasets are only locally required currently, but may become more widely used in the future. For example, San Francisco provides Municipal Energy Benchmarking and Municipal Natural Gas Equipment Inventory datasets, which are mandated by local ordinances to report annual energy and natural gas usage for all non-residential buildings. These are likely to be useful as energy use indicators. Similar datasets in Los Angeles and New York illustrate how mandated open data can move beyond disclosure to actively drive policy interventions aimed at reducing GHG emissions and improving energy efficiency [53,54]. Likewise, Boston’s Building Energy Reporting and Disclosure Ordinance (BERDO) strengthens transparency and efficiency in managing building-related GHG emissions and achieving net-zero targets by 2050 [55]. Additionally, many cities reuse datasets from broader national sources, such as the U.S. Census, the American Community Survey, and various health-oriented surveys. These demographically oriented datasets, alone or correlated with environmental or public service data, can help quantify equity indicators, and are highly useful within OGD systems and potentially a next-generation SDG 11 indicator framework.

Once we developed SDG 11+, we used the same search method as with SDG 11 to check whether datasets exist on each portal for the new indicators.

We should note that while SDG 11+ indicators provide a robust starting point for cities seeking to monitor progress toward urban sustainability, it is also crucial to include analysis by factors such as gender, age, race, disability status, income, and geographic area. This detailed analysis allows for more effective targeting of interventions and equips city planners, policymakers, and urban development professionals with the tools needed to make a meaningful impact.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Relation of OGD Portals to Current SDG 11 Indicators

Amazingly, no datasets published on the portals of these 19 U.S. cities directly reflect SDG 11 indicators, and no portals directly discuss the SDGs. This shows a pressing need to link U.S. OGD portals to the SDGs. According to Abraham and Iyer (2021) and Temmer and Jungcurt (2021), reasons for low U.S. use of the Agenda 2030 framework may include low public awareness, political resistance to international agendas, lack of federal or state mandates, lack of committed bottom-up stakeholders, use of the SDGs as educational rather than policy tools, and difficulties in finding data corresponding to the framing of SDG indicators [56,57].

Most portals provided multiple datasets indirectly related to SDG 11. In these U.S. cities, we identified a total of 495 datasets indirectly reflecting SDG 11 (see Table 3). For instance, these cities make available 83 datasets related to Target 11.1 (affordable housing). Examples include San Francisco’s Affordable Housing Pipeline, organized by the number of units and income, New York’s Rent Affordability dataset with building-by-building information on units, and Los Angeles’ tracking of the city’s progress toward goals of permitting 100,000 new housing units and constructing 15,000 affordable units. However, these datasets do not directly correspond to indicator 11.1.1 ‘Proportion of the urban population living in slums, informal settlements, or inadequate housing,’ or indeed to any standardized metric of housing affordability.

The availability of related datasets varied significantly across SDG 11 targets. The largest number corresponded to Target 11.2 (affordable and sustainable transport systems, 151 datasets or 31% of the total datasets) and Target 11.7 (access to safe and inclusive spaces, 126 datasets or 25% of the total datasets). However, many of these datasets lack the demographic information needed to be maximally useful in terms of capturing equity-oriented aspects of urban sustainability. For Target 11.2, data addressing transportation needs for women and older persons is typically missing. For Target 11.7, data often do not consider open space usage by women, children, older persons, and persons with disabilities. City portals contained few datasets corresponding to Targets 11.5 (disasters; 1% of the total datasets), 11.4 (cultural and natural heritage; 3% of the total datasets), and 11.3 (inclusivity and participation; 8% of the total datasets).

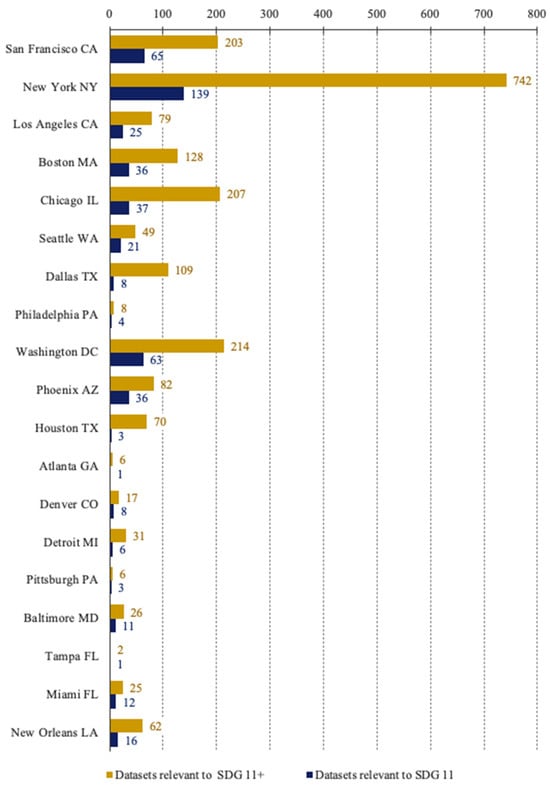

Most indirectly related datasets come from the cities ranked highest in the SCI 2024. Of the 459 datasets on these portals, 86.7% (398) are from the nine top-ranked cities, while the nine lowest-ranked cities contribute only 13.3% (61). New York, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. alone account for 267 datasets, more than half of the total. In contrast, several low-ranked cities provide only one to three datasets each (e.g., Atlanta, Tampa, Houston, Pittsburgh). Vigorous open data systems thus appear to correlate highly with a city’s sustainability performance.

Overall, although municipal open data portals provide some datasets indirectly related to SDG 11 targets and indicators, portals vary widely, and this mechanism for providing public data related to sustainable city progress appears to be little used as of yet by American cities. This is a major opportunity for the future.

4.2. The Relation Between OGD and SDG 11+

Using the same method as for datasets related to SDG 11, we identified 13 datasets directly related to SDG 11+ indicators, meaning that these datasets exactly contained the data needed to measure the indicator. For example, San Francisco has a Vision Zero Benchmarking dataset that provides the number of traffic fatalities per 100,000 residents for a given year. New York offers the NYC Climate Budgeting Report, which forecasts reductions in emissions and particulate matter (tPM2.5) as a result of city actions. Additionally, both Los Angeles and Chicago have datasets that measure deaths attributed to disasters per 100,000 population.

While this is a relatively small number, we also identified 2066 datasets indirectly reflecting indicators of SDG 11+ (Table 5), meaning that these indicators could be produced relatively easily from existing data via several arithmetic operations, for example, by calculating per capita figures.

Table 5.

All Datasets Related to SDG 11 and SDG 11+ Indicators in 19 U.S. Cities.

Thus, these OGD portals as they currently stand show strong potential to supply datasets related to SDG 11+, enabling comprehensive analyses of urban sustainability (see Figure 3). Portals still varied widely: the top-ranked cities account for over 84% of datasets related to SDG 11+, while the lower-ranked cities contribute only 12%. So, more effort is needed to develop standardized sustainability indicators within open data systems for most cities.

Figure 3.

Datasets Relating to SDG 11 vs. SDG 11+ for 19 U.S. Cities.

4.3. Recommendations for Improvement of OGD Portals

The above analysis of open data portals of 19 U.S. cities helped us identify key areas for improvement. Development of specific datasets related to SDG 11 or broader sustainable city indicator sets, such as SDG 11+, is one area for improvement. Beyond that, several topics require attention: improving usability, enhancing content and connecting data to policy, prioritizing data integrity, providing timely updates, adding more disaggregated data, and adopting an “all-of-society” approach. Actions in these areas could improve OGD portal functionality generally and could help position portals to play a more central role in promoting and monitoring urban sustainability. Such actions will require leadership from the political sphere as well as within institutions.

Usability concerns the ease with which users can discover data. Search functions and labelling are central to this task. Potential improvements include allowing users to filter datasets, providing complete descriptions for each data column, defining acronyms in dataset titles, and eliminating duplicate datasets that differ only slightly in content. For instance, the OGD portals for Boston and Phoenix do not offer the option to filter search results by document type, such as files, stories, or charts, while searches on the San Francisco and New York portals using the same keywords sometimes fail to retrieve identical datasets. Seattle presents ‘Paid Parking Occupancy’ as five separate datasets covering 2018 through 2022; these could easily be consolidated for clarity.

Portal content can be improved through systematic data curation, collecting data from municipal agencies and nongovernmental sources, and displaying it in standardized, user-friendly forms along with helpful text and visualizations (charts, graphics, maps, and other tools that dramatize the most relevant information). At the same time, portals can link data to specific city policy goals and SDG 11/SDG 11+. For example, San Francisco highlights “% of households spending over 30% of income on housing” using its “Housing Production—2005 to present” dataset, which details numbers of units affordable to households across different income levels. Phoenix’s portal showcases a variety of indicators related to ‘American Rescue Plan Act Funding from 2021 to 2024’ to help users understand how these resources are allocated. Such approaches aligning portal content with urban sustainability can be replicated across all policy areas.

Cities can improve data integrity by identifying key information and relationships between databases and ensuring that this material is accurate, standardized across departments, well-explained, and clearly presented. The OGD literature shows that many governments simply dump databases on portals with little review or user context [39,42,43,44,45,58]. While some portals provide large quantities of data, the quality varies, and the significance of the datasets is often unclear. Careful curation is therefore essential. For example, it would often improve data usability to integrate data from various sources into a single dataset, such as linking environmental, demographic, and socio-economic information into a dataset mapping flood vulnerability by neighborhood. Achieving integrations such as this requires standardized data structures and definitions across departments.

Numerous scholars have highlighted the lack of timely updates for published datasets [3,17,23,24]. Outdated information reduces the relevance and usability of OGD portals for decision-making. Regular updating requires identifying personnel and processes well in advance, ideally when the indicator or dataset is first created, and careful management to make sure that updating occurs.

Disaggregated data—broken down into small categories and units of spatial resolution—is essential for many purposes, including geographically detailed research, equity-oriented analysis, and SDG progress-tracking. Some city portals lack key categories of demographic data, and datasets have varying levels of spatial resolution. Files often have inconsistent characteristics across departments, making it difficult to combine, compare, or analyze data. Ensuring a high and consistent level of disaggregation means that data will be maximally useful for analysis and informed decision-making.

Finally, an “all-of-society” approach actively engages government departments, the private sector, civil society, academia, and local communities in both data collection and use ([4], p.24). Mechanisms to develop this approach include advisory boards, intra-governmental and community trainings, feedback forms, opportunities for users to contribute data, and OGD events. For example, the Seattle Open Data Portal includes a Customer Satisfaction Survey capturing feedback from individuals who interacted with officers after calling 911. Similarly, San Francisco has developed multiple survey datasets related to services, libraries, safety, street cleanliness, and commuting behaviors. Dallas uses a Community Survey to establish OGD priorities based on residents’ input. Consistent and systematic support for participatory data collection strengthens OGD’s ability to foster community engagement and drive measurable progress toward urban sustainability.

OGD portals can offer substantial opportunities to support urban sustainability and SDG 11. However, barriers such as political resistance, lack of standardized datasets, variable data quality, limited disaggregation, and usability challenges constrain their full potential. Addressing these issues through improved portal functionality, data curation, timely updates, and inclusive stakeholder engagement would enhance cities’ ability to translate open data into actionable insights and effective SDG-based policies.

5. Conclusions

This paper examined how well municipal OGD portals support SDG 11 by analyzing 19 U.S. cities ranked in the 2024 SCI and assessing the degree to which their portals contain datasets relevant to SDG 11 and an expanded set of indicators, SDG 11+. We found that while none of the portals directly displayed SDG 11 indicators, many offered datasets indirectly related to SDG 11. SDG 11+ indicators were more widely reflected and appear more likely to enable cities to leverage existing datasets for urban sustainability analyses.

However, significant barriers limit the effectiveness of OGD in supporting SDG 11. These include political resistance, a lack of standardization across datasets and departments, variable data quality and usability, limited disaggregation, and infrequent updates. Such challenges constrain the ability of open data to be translated into actionable insights for urban sustainability policies.

Despite these limitations, opportunities exist to strengthen OGD portals. Enhancing usability, improving data integrity and integration, linking datasets to city policies, providing timely updates, expanding disaggregation, and adopting an “all-of-society” approach can improve portal functionality and foster evidence-based decision-making. Explicit alignment with SDG 11, other SDGs, and broader sustainability indicators would further enable cities to track progress, compare performance, and implement more equitable and effective urban sustainability interventions.

Future research could further examine the applicability of the SDG 11+ indicator framework across diverse contexts, as well as open data portals beyond the 19 U.S. cities analyzed in this study. Such comparative analyses would provide valuable insights into how varying governance models, data infrastructure, and national/regional/local priorities influence the integration of open data into sustainable urban development policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.W. and G.N.N.; methodology, S.M.W. and G.N.N.; validation, S.M.W. and G.N.N.; formal analysis, S.M.W. and G.N.N.; investigation, S.M.W. and G.N.N.; data curation, G.N.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.W. and G.N.N.; writing—review and editing, S.M.W.; visualization, G.N.N.; supervision, S.M.W.; project administration, S.M.W. and G.N.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SDG 11 | Sustainable Development Goal 11—Sustainable Cities and Communities |

| OGD | Open Government Data |

| Agenda 2030 | The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development |

| SCI 2024 | the Arcadis’ Sustainable Cities Index 2024 report |

| LEED | Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design |

| BREEAM | Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method |

| ISO 37120 | International Standard 37120 |

| VMT | Vehicle Miles Traveled |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Existing SDG 11 Targets and Indicators and Potential SDG 11+ Targets and Indicators within the SDGs Framework with Rationalities.

Table A1.

Existing SDG 11 Targets and Indicators and Potential SDG 11+ Targets and Indicators within the SDGs Framework with Rationalities.

| Existing SDG 11 Target | Existing SDG 11 Indicators | SDG 11+ Target | SDG 11+ Indicators | Rationale for Potential Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 11-Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable | ||||

| 11.1 By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums | 11.1.1 Proportion of urban population living in slums, informal settlements or inadequate housing | Affordable and adequate housing for all | --% of households spending over 30% of income on housing | Captures affordability across income groups |

| --Number of homeless persons per 100k residents | Addresses extreme housing deprivation | |||

| --% of new affordable housing units in annual new housing units | Tracks both housing supply and inclusion efforts | |||

| --% of residents living in housing with less than 97 ft2 (9 m2) per person | Highlights crowding and space adequacy | |||

| 11.2 By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons | 11.2.1 Proportion of population that has convenient access to public transport, by sex, age and persons with disabilities | Inclusive, affordable, safe, and sustainable transport | --% change in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) annually | Relates to GHG emissions, vehicle dependency, sprawl, and quality of life |

| --% of population living within 400 m of public transport with regular service | Captures not only proximity but also service quality and diversity of transport options | |||

| --% of trips made by walking, biking, and public transit | Tracks the use of sustainable and low-emission modes | |||

| --Transport-related fatalities and injuries per 100k residents | Provides a globally comparable safety benchmark that reflects system design | |||

| 11.3 By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries | 11.3.1 Ratio of land consumption rate to population growth rate | Sustainable land use | --Number of residents per acre/hectare of urban area | Measures land use efficiency: sprawl, density, and compactness |

| --Average % of land within each locally designated neighborhood used for (a) residential, (b) commercial, (c) industrial, and (d) institutional purposes | Measures land use mix in city-defined neighborhoods; higher mix indicates locally- and pedestrian-oriented communities | |||

| --Agricultural area per 100k residents | Tracks land used for urban farming and local food production. | |||

| 11.3.2 Proportion of cities with a direct participation structure of civil society in urban planning and management that operate regularly and democratically | Participatory and democratic decision-making | --% adult population voting in last municipal election | Reflects extent to which citizens are engaged in formal political processes | |

| --Number of registered NGOs, political parties, and annual protest events per 100k residents | Captures the vibrancy of civic life and political participation beyond elections | |||

| --Strength of open government requirements (open meetings, conflict-of-interest, public consultation, transparent election financing, and open data inventory) | Open and transparent government standards | |||

| --% women in elected and appointed positions | Indicates gender equity in decision-making. | |||

| 11.4 Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage | 11.4.1 Total per capita expenditure on the preservation, protection and conservation of all cultural and natural heritage, by source of funding (public, private), type of heritage (cultural, natural) and level of government (national, regional, and local/municipal) | Protected cultural and natural heritage | --# of heritage sites with legal protection status | Tracks legal safeguards against demolition, neglect, or misuse |

| --Number of ongoing cultural heritage initiatives, programs, or community-led preservation projects per year | Reflects real-world investment in preservation efforts | |||

| --Number of cultural institutions and sporting facilities per 100k population | Shows access to culture and sports. | |||

| 11.5 By 2030, significantly reduce the number of deaths and the number of people affected and substantially decrease the direct economic losses relative to global gross domestic product caused by disasters, including water-related disasters, with a focus on protecting the poor and people in vulnerable situations | 11.5.1 Number of deaths, missing persons and directly affected persons attributed to disasters per 100,000 population | Urban resilience | --Deaths attributed to disasters per 100k population | Provides a direct measure of risk and impact |

| 11.5.2 Direct economic loss attributed to disasters in relation to global domestic product (GDP) 11.5.3 (a) Damage to critical infrastructure and (b) the number of disruptions to basic services, attributed to disasters | --Social infrastructure spending per resident | Assesses public investment in education, health, and social services | ||

| 11.6 By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management | 11.6.1 Proportion of municipal solid waste collected and managed in controlled facilities out of total municipal waste generated, by cities 11.6.2 Annual mean levels of fine particulate matter (e.g., PM2.5 and PM10) in cities (population weighted) | Reduced pollution and resource use | --% of solid waste recycled | Reflects circular economy progress through comprehensive waste recovery |

| --Number of days with good air quality (AQI ≤ 50) annually | Captures frequency of healthy air | |||

| --Estimated reductions in tons of Particulate Matter 2.5 (tPM2.5) from city actions | Indicates air quality and pollution exposure | |||

| --% population living less than 300 m away from major polluters | Indicates population exposure to pollution and prevalence of environmental injustice | |||

| 11.7 By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities | 11.7.1 Average share of the built-up area of cities that is open space for public use for all, by sex, age and persons with disabilities 11.7.2 Proportion of persons victim of non-sexual or sexual harassment, by sex, age, disability status and place of occurrence, in the previous 12 months | Inclusive, safe, and accessible green and public spaces | --% of residents living within 800 m of green space | Measures physical accessibility to urban green areas for well-being and equity |

| --Amount of green space area in acres/hectares per 100k residents | Measures the overall quantity of green spaces | |||

| --Violent crime rate per 100k residents | Provides a widely used, comparable metric of public space safety | |||

| SDG 1-End poverty in all its forms everywhere | ||||

| 1.2 By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions | 1.2.1 Proportion of the population living below the national poverty line 1.2.2 Proportion of men, women, and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions | Reduced poverty | --% of urban population living in poverty according to national definitions | Provides basic yardstick on economic progress |

| --% of children living in poverty | Reveals intergenerational inequality and identifies vulnerable groups most impacted by poverty | |||

| SDG 2-Food End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture | ||||

| 2.1 By 2030, end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round | 2.1.1 Prevalence of undernourishment 2.1.2 Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the population, based on the Food Insecurity Experience Scale | Reliable access to affordable, nutritious food | --% of food consumed that is produced within 100 mi/160 km | Measures the sustainability and resilience of the urban food supply chain |

| --% of residents living within 800 m of a grocery store | Captures physical access to food | |||

| --% residents with obesity (Body Mass Index ≥ 30) in the total population | Serves as an early warning of poor nutrition and unhealthy lifestyles | |||

| SDG 3-Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages | ||||

| 3.7 By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services, including for family planning, information and education, and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programs 3.8 Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential healthcare services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all | 3.7.1 Proportion of women of reproductive age (aged 15–49 years) who have their need for family planning satisfied with modern methods 3.8.1 Coverage of essential health services 3.8.2 Proportion of population with large household expenditures on health as a share of total household expenditure or income | Good health and well-being | ---Average life expectancy, years | Tracks broad health and equity outcomes |

| --% of women of reproductive age with access to family planning | Measures reproductive health access for women | |||

| --Access to health care (Universal Health Coverage Index) | Shows health care adequacy | |||

| --Doctors/nurses per 100k residents | Indicates healthcare availability | |||

| SDG 4-Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all | ||||

| 4.1 By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes 4.7 By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development | 4.1.1 Proportion of children and young people (a) in grades 2/3; (b) at the end of primary; and (c) at the end of lower secondary achieving at least a minimum proficiency level in (i) reading and (ii) mathematics, by sex 4.7.1 Extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in (a) national education policies; (b) curricula; (c) teacher education and (d) student assessment | Inclusive, high-quality education and sustainability knowledge | --% of residents with at least a high school diploma | Measures access to basic educational services |

| --Number of public libraries per 100k residents | Reflects access to free, lifelong learning and public knowledge spaces | |||

| --% of public schools offering sustainable development curriculum | Captures integration of sustainable development concept and agenda into formal education | |||

| SDG 5-Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls | ||||

| 5.1 End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere 5.2 Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation | 5.1.1 Whether or not legal frameworks are in place to promote, enforce and monitor equality and non-discrimination on the basis of sex 5.2.1 Proportion of ever-partnered women and girls aged 15 years and older subjected to physical, sexual or psychological violence by a current or former intimate partner in the previous 12 months, by form of violence and by age | Gender equality | --% of urban women in poverty | Highlights women’s economic status |

| --Number of women’s suicides per 100k population | Tracks the severity of gender-based health and violence impacts | |||

| --Women’s mortality rate [number of deaths] per 100k population | Indicates women’s health outcomes | |||

| --Number of women’s organizations & support centers per 100k residents | Reflects the availability of institutional and community-based support for women’s empowerment, safety, and participation | |||

| SDG 6-Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all | ||||

| 6.1 By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all | 6.1.1 Proportion of population using safely managed drinking water services | Safe, affordable drinking water | --% of population lacking access to safe drinking water | Measures the extent of basic water access and identifies underserved areas |

| --Total Dissolved Solids (milligrams per liter) in public water supply | Provides a widely used water quality indicator related to safety and health | |||

| --% of buildings reporting annual water benchmarking data | Tracks progress on urban water management and transparency | |||

| SDG 7-Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all | ||||

| 7.2 By 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix | 7.2.1 Renewable energy share in the total final energy consumption | Renewable energy | --% of buildings reporting annual energy benchmarking data | Promotes transparency and efficiency in urban energy use |

| --% renewable energy in electric power | Basic measure of the renewable energy transition | |||

| SDG 8-Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all | ||||

| 8.5 By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value | 8.5.2 Unemployment rate, by sex, age and persons with disabilities | Decent work and economic growth | --Unemployment rate | Reflects economic health |

| --Number of businesses per 100k population | Indicates diverse local economic activity | |||

| --Number of green jobs per 100k population | Captures local economic adaptation + progress toward a just green transition | |||

| --Inflation rate, % | Indicates economic pressure on households | |||

| SDG 10-Reduce inequality within and among countries | ||||

| 10.3 Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard 10.4 Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality | 10.3.1Proportion of population reporting having personally felt discriminated against or harassed within the previous 12 months on the basis of a ground of discrimination prohibited under international human rights law 10.4.1 Labor share of GDP 10.4.2 Redistributive impact of fiscal policy on the Gini index | Reduce inequality | --City-level Gini coefficient (from 0 to 1) | Offers a widely recognized, quantifiable snapshot of overall income inequality |

| --% of population guaranteed anti-discrimination protections related to jobs, housing, and services | Basic legal protections for many classes of people | |||

| --% of population guaranteed free or affordable legal assistance | Helps ensure equal treatment within the justice system | |||

| SDG 13-Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts | ||||

| 13.2 Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning 13.3 Improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning | 13.2.2 Total greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) per year 13.3.1 Extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in (a) national education policies; (b) curricula; (c) teacher education; and (d) student assessment | Climate mitigation, adaptation, and equity | --Total and per capita GHG emissions | Provides baseline climate indicator |

| --Climate resilience centers per 100k population | Measures community preparedness for climate risks | |||

| --% of municipal climate-related spending targeted to disadvantaged populations (by income, race, age, disability, or location) | Captures the equity dimension of climate action by showing how city resources are distributed to those most at risk | |||

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Misselwitz, P.; Salcedo Villanueva, J. The urban dimension of the SDGs: Implications for the New Urban Agenda. Cities Alliance Discuss. Pap. 2015, 3, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Statistics Division. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- United Nations. Independent Expert Advisory Group on a Data Revolution for Sustainable Development. A World That Counts: Mobilising the Data Revolution for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: http://www.undatarevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/A-World-That-Counts.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Attard, J.; Orlandi, F.; Scerri, S.; Auer, S. A systematic review of open government data initiatives. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.; Perini, F. Researching the emerging impacts of open data: Revisiting the ODDC conceptual framework. J. Commun. Inform. 2016, 12. Available online: https://openjournals.uwaterloo.ca/index.php/JoCI/article/view/3246 (accessed on 10 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Meschede, C.; Siebenlist, T. Open data portals for urban sustainable development: People, policies, and technology. In Smart Cities and the UN SDGs; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, S.G.; Young, A. Open Data in Developing Economies: Toward Building an Evidence Base on What Works and How; African Minds: Cape Town, South Africa, 2017; p. 284. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/28916 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- OpenGovData. (n.d.). Home. Available online: https://opengovdata.org (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Chignard, S. A Brief History of Open Data. ParisTech Review. 2013. Available online: https://www.paristechreview.com/2013/03/29/brief-history-open-data/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Alberti, M. Measuring urban sustainability. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1996, 16, 381–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Seattle. Indicators of Sustainable Community: A Report to Citizens on Long-Term Trends in Our Community; Sustainable Seattle: Seattle, WA, USA, 1995; Available online: https://ise.unige.ch/isdd/IMG/pdf/Indicateurs.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Jacksonville Community Council Inc. (JCCI). Quality of Life Progress Report; Jacksonville Community Council Inc.: Jacksonville, FL, USA, 2020; Available online: https://jcciweb.wixsite.com/jcci/indicators (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Boston Foundation. Boston Indicators Project; Boston Foundation: Boston, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.bostonindicators.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- City of San Francisco. Sustainability Plan for the City of San Francisco; San Francisco Department of the Environment: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; Available online: https://www.sfenvironment.org/media/9485 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- City of Portland. Portland’s Climate Action Plan: Local Strategies to Address Climate Change; Bureau of Planning and Sustainability: Portland, OR, USA, 2015. Available online: https://www.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2019-07/cap-2015_june30-2015_web_0.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Satterthwaite, D. A new urban agenda? Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Saum, A.; Halla, P.; Superti, V.; Boesch, A.; Binder, C.R. Indicators for urban sustainability: Key lessons from a systematic analysis of 67 measurement initiatives. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 119, 106879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Kingsbury, B.; Merry, S.E. The local-global life of indicators: Law, power, and resistance. In The Quiet Power of Indicators. Measuring Governance, Corruption, and Rule of Law; Merry, S.E., Davis, K.E., Kingsbury, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Goal 11: Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Verma, P.; Raghubanshi, A.S. Urban sustainability indicators: Challenges and opportunities. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Hsu, A.; Weinfurter, A. Sustainable and inclusive–Evaluating urban sustainability indicators’ suitability for measuring progress towards SDG-11. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2021, 48, 2346–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; Arfvidsson, H.; Anand, G.; Bazaz, A.; Fenna, G.; Foster, K.; Jain, G.; Hansson, S.; Evans, L.M.; Moodley, N.; et al. Developing and testing the urban sustainable development goal’s targets and indicators—A five-city study. Environ. Urban. 2015, 28, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, S.C.; Simon, D.; Croese, S.; Nordqvist, J.; Oloko, M.; Sharma, T.; Taylor Buck, N.; Versace, I. Adapting the Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda to the city level: Initial reflections from a comparative research project. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2019, 11, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, C.; Spiliotopoulou, L.; Charalabidis, Y. Open data movement in Greece: A case study on open government data sources. In Proceedings of the 17th Panhellenic Conference on Informatics, Thessaloniki, Greece, 19–21 September 2013; pp. 279–286. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2491845.2491876 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Linders, D.; Wilson, S.C. What is open government? One year after the directive. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Digital Government Research Conference: Digital Government Innovation in Challenging Times, College Park, MD, USA, 12 June 2011; pp. 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kučera, J.; Chlapek, D.; Nečaský, M. Open government data catalogs: Current approaches and quality perspective. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Government and the Information Systems Perspective, Bangkok, Thailand, 25–27 August 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 152–166. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-40160-2_13 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Data.gov. (n.d.b). Celebrating 15 Years of Data.Gov. Available online: https://data.gov/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Seattle Channel. Mayor Signs New Building Emissions Performance Standards into Law [Video]. Seattle Channel. 13 December 2013. Available online: https://www.seattlechannel.org/mayor-and-council/mayor/city-of-seattle-mayor-videos?videoid=x152936 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Ojo, A.; Curry, E.; Zeleti, F.A. A tale of open data innovations in five smart cities. In Proceedings of the 2015 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Koloa, Hawaii, 5–8 January 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 2326–2335. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7070094 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Meuleman, J.; Kwok, W.M.; Aquaro, V. Open government data for sustainable development: Trends, policies and assessment: Continuing the pilot assessment of the Open Government Data Index (OGDI). In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Guimarães, Portugal, 4–7 October 2022; pp. 256–265. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3560107.3560149 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Ahlgren, B.; Hidell, M.; Ngai, E.C.H. Internet of things for smart cities: Interoperability and open data. IEEE Internet Comput. 2016, 20, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, J.; Bullard, R.D.; Evans, B. (Eds.) Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. “The Right to the City”: New Left Review (2008). In The City Reader; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, L. What is data justice? The case for connecting digital rights and freedoms globally. Big Data Soc. 2017, 4, 2053951717736335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijer, E.; Grimmelikhuijsen, S.; Van Den Berg, J.; Meijer, A. Open data work: Understanding open data usage from a practice lens. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2020, 86, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.A. How data does political things: The processes of encoding and decoding data are never neutral. In LSE Impact Blog, London School of Economics and Political Science; The London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2015; Available online: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2015/10/07/how-data-does-political-things/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Brandusescu, A. Open Data is About People, Not Just Innovation. SciDev.Net. 7 July 2017. Available online: https://www.scidev.net/global/data/opinion/open-data-people-innovation.html (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Kitchin, R. Four Critiques of Open Data Initiatives. The Programmable City. 9 November 2013. Available online: https://progcity.maynoothuniversity.ie/2013/11/four-critiques-of-open-data-initiatives/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Kitchin, R.; Lauriault, T.P.; Mcardle, G. Knowing and governing cities through urban indicators, city benchmarking and real-time dashboards. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2015, 2, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbig, N.; Cresswell, A.M.; Burke, G.B.; Luna-Reyes, L. The Dynamics of Opening Government Data: A White Paper; Centre for Technology in Government, State University of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.ctg.albany.edu/media/pubs/pdfs/opendata.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Harrison, T.M.; Guerrero, S.; Burke, G.B.; Cook, M.; Cresswell, A.; Helbig, N.; Hrdinová, J.; Pardo, T. Open government and e-government: Democratic challenges from a public value perspective. Inf. Polity 2012, 17, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, R.P. Open government portals assessment: A transparency for accountability perspective. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Government, Koblenz, Germany, 16–19 September 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 62–74. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-40358-3_6 (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Zurada, J.; Karwowski, W. Knowledge discovery through experiential learning from business and other contemporary data sources: A review and reappraisal. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2011, 28, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuiderwijk, A.; Janssen, M. A coordination theory perspective to improve the use of open data in policy-making. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Government, Koblenz, Germany, 16–19 September 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 38–49. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-40358-3_4 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Arcadis. Sustainable Cities Index 2024. 2000 Days to Achieve a Sustainable Future. 2024. Available online: https://www.arcadis.com/en/knowledge-hub/perspectives/global/sustainable-cities-index-2024 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Nabiyeva, G.N.; Wheeler, S.M. How Is SDG 11 Linked with Other SDGs? Evidence from the United Nations Good Practices. Highlights Sustain. 2024, 3, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 37120; Sustainable Cities and Communities—Indicators for City Services and Quality of Life. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. America’s Rental Housing 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/americas-rental-housing-2022 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. “Does compact development make people drive less?” The answer is yes. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2017, 83, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. EJSCREEN Technical Document: Environmental Justice Mapping and Screening Tool. 5 May 2015. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-05/documents/ejscreen_technical_document_20150505.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Health Effects Institute. Traffic-Related Air Pollution: A Critical Review of the Literature on Emissions, Exposure, and Health Effects (HEI Special Report 17). 2010. Available online: https://www.healtheffects.org/publication/traffic-related-air-pollution-critical-review-literature-emissions-exposure-and-health (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Inland Empire Energy. (n.d.). Energy Benchmarking Requirements Throughout California: A City-By-City Guide. Available online: https://www.inlandempireenergy.com/insights/energy-benchmarking-requirements-throughout-california-a-city-by-city-guide (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- New York City Department of Buildings. (n.d.). LL97 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction. NYC.Gov. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/site/buildings/codes/ll97-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reductions.page (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- City of Boston. City of Boston Climate Action Plan. 2019. Available online: https://www.boston.gov/departments/environment/boston-climate-action (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Abraham, D.B.; Iyer, S.D. Introduction: Localizing SDGs and empowering cities and communities in North America for sustainability. In Promoting the Sustainable Development Goals in North American Cities: Case Studies & Best Practices in the Science of Sustainability Indicators; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temmer, J.; Jungcurt, S. Data for good for all: Enabling all communities to track progress toward SDG implementation. In Promoting the Sustainable Development Goals in North American Cities: Case Studies & Best Practices in the Science of Sustainability Indicators; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 97–108. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-59173-1_8 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Janssen, M.; Charalabidis, Y.; Zuiderwijk, A. Benefits, adoption barriers and myths of open data and open government. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2012, 29, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).