Overcoming Pluralistic Ignorance—Brief Exposure to Positive Thoughts and Actions of Others Can Enhance Social Norms Related to Climate Action and Support for Climate Policy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. “Community Voices” as Normative Social Media

1.2. Psychological Variables Considered in This Study

- Social norms: Descriptive norms are the perception of what others are currently doing. Prescriptive norms are perceptions of what others should be doing. Norm awareness is the degree to which an individual perceives that they understand a particular norm.

- Psychological distance of climate change: This metric assesses perceived separation between an individual and climate change. It encompasses four dimensions of psychological distance—temporal, spatial, social, and hypothetical—related to climate change [18]. Van Lange et al. [19] have argued that reducing the psychological distance of climate change is an important strategy for motivating climate action. Intuitively, this makes sense. However, while some studies (e.g., [20,21]) have found support for this hypothesis, others [22,23,24] have found mixed results.

- Environmental Cognitive Alternatives Scale (ECAS): This scale measures an individual’s ability to imagine a more harmonious and sustainable relationship between humans and nature [25]. The scale is grounded in social identity theory, which argues that people are more likely to work for social change if they can imagine a more positive future. Recent research supports the idea that increases in a positive vision for the future lead to more willingness to act [26].

- Positive and negative emotions related to climate change and action: Prior research suggests that emotional reactions to climate change, and their impact on behavior, are complex. While positive emotions have been linked to increases in climate action, there is no “one size fits all” approach to increasing positive emotions through climate messaging [27]. Qualitative evidence suggests that exposure to role models engaged in climate action can increase positive emotions [28]. Negative emotional reactions to climate change abound, and a growing literature documents the negative impacts of climate anxiety (e.g., [29]). The general consensus on negative emotions among communications experts is that they are not effective in reliably encouraging engagement on climate change [30,31]. However, some research has found that negative emotions do contribute to constructive responses (e.g., [32,33,34]).

- Collective Efficacy: The belief that behavior can be undertaken that will have a desired impact is thought to be a key determinant of action [1]. Because climate change is a problem that must be solved collectively, we focused on assessing collective efficacy—an individual’s sense that, as a group, people can address climate change. Mitigation efficacy is the perception that the extent of climate change can be reduced. Adaptation efficacy is the perception that the negative impacts of climate change that will inevitably occur can be reduced. In this study, we measured both.

- Policy support: Behavioral action is challenging to directly measure in a survey, particularly in response to a short-term manipulation. Support for climate action policies is an important attitudinal outcome that has implications for voting behavior and the willingness of elected officials to support policy and is therefore a reasonable surrogate for behavior.

1.3. Hypotheses

- Exposure to climate action-focused CV content

- Exposure to climate-focused CV content will increase norms related to climate action. We expect this to be the most direct and highest magnitude impact with the simple rationale that seeing others engage in climate action should increase viewers’ sense that others are, indeed, engaging in climate action. CV content included in the study included messages related to both prescriptive and descriptive norms. However, since participants would be observing the thoughts and actions of others in this study, we hypothesized a larger impact on descriptive than on prescriptive norms.

- Exposure will: decrease participants’ psychological distance related to climate change; increase ECAS; and increase behavioral efficacy related to climate action. The rationale for these hypotheses is that seeing others engage in climate action should: make climate change feel more immediate and less distant; provide examples that help viewers envision a positive future; and give the viewer specific and salient ideas of climate behaviors they themselves might engage in.

- Exposure will have counteracting impacts on emotions. Confronting climate change induces anxiety and fear and may therefore increase negative emotions and decrease positive emotions, even when participants are exposed to positive actions that address climate change. On the other hand, seeing people taking positive action could logically enhance hope and efficacy and thereby increase positive emotions and decrease negative emotions.

- Exposure will increase support for climate policy. Support for policy should be influenced by norms, psychological distance, and efficacy; if these go up as expected, then policy support should follow.

- Exposure to pro-social CV content

- Similar to exposure to climate-focused content, we also expected that exposure to pro-social CV content that does not relate to climate change would increase norms related to climate action. Our rationale for this expectation is that although pro-social content does not directly relate to climate change, simply seeing others engaged in a wide range of different kinds of pro-social thought and action in their communities should increase the sense that others are engaging in positive thought and action, including action that addresses climate change.

- We likewise expect exposure to pro-social content to increase ECAS and increase behavioral efficacy related to climate action. Our rationale for this expectation follows from our expectation that norms will spill over to include climate action; simply seeing others engaged in a variety of pro-social actions in their communities should still: increase the sense that social problems (including climate change) can be solved; provide examples that help viewers envision a positive future (including improved human relations with nature); and enhance the viewers perception that challenges (including climate change) can be addressed through behavioral choices that the viewer might engage in.

- Pro-social CV content that is unrelated to climate action should have no appreciable impact on participants’ psychological distance related to climate change.

- Impacts on climate norms, psychological distance, ECAS and climate action efficacy should all be weaker for pro-social CV content than for climate-focused CV content because the pro-social content does not directly address climate. Concrete examples of positive climate action should be more impactful on all of these than non-climate-focused pro-social content because of their direct rather than indirect nature.

- Exposure to pro-social CV content will decrease negative emotions related to climate change and increase positive emotions. We expect this because seeing pro-social thought and action related to a range of social issues should elicit a positive emotional response to a broad set of social issues, including climate change.

- Exposure should increase support for climate policy. Support for policy should be influenced by norms, distance and efficacy; if these increase as expected, then policy support should follow.

- Exposure to CV content derived from one’s region

- CV content will elicit a greater response from the regional NE Ohio sample than from the national sample. Specifically, relative to the national sample, we expected the NE Ohio sample to exhibit increased norms, decreased psychological distance, increased ECAS, increased behavioral efficacy, and increased policy support. The rationale for these regional-impact hypotheses is that we anticipate that NE Ohio residents will identify with NE Ohio-derived CV content more strongly than participants who do not live in NE Ohio.

- We considered alternative hypotheses with respect to the emotional impact of exposure to regional climate-action CV content. For example, decreased psychological distance could both enhance the salience and concomitant anxiety associated with the reality of climate change. On the other hand, seeing people in one’s region take action could increase hope and optimism that the problem can be solved.

2. Materials and Methods

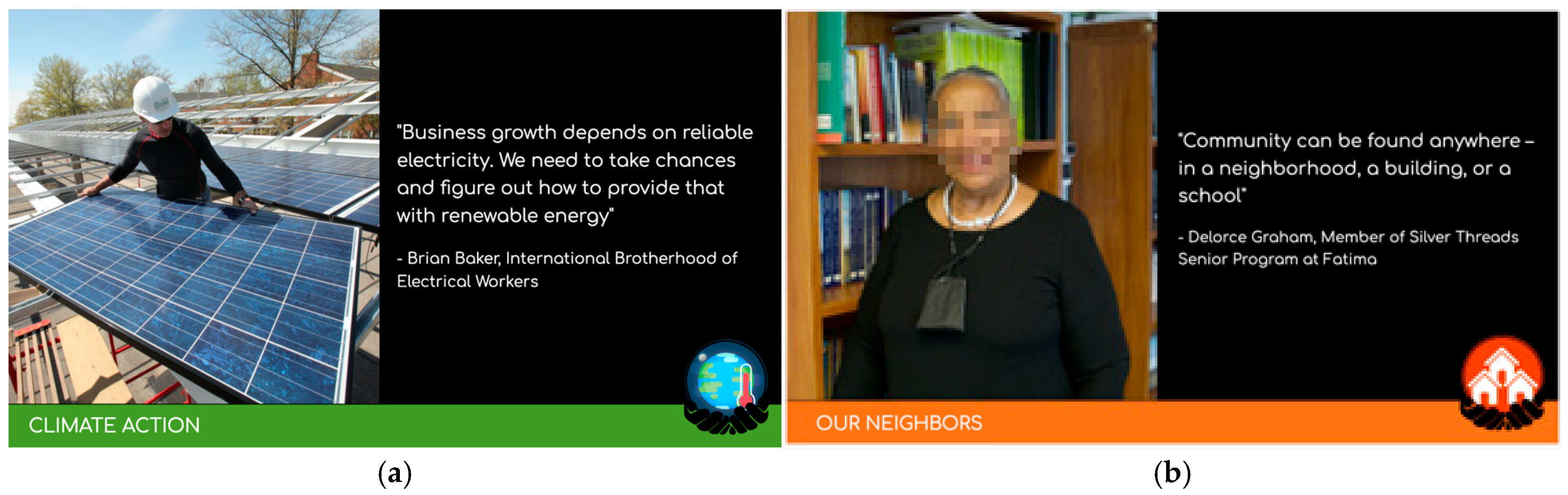

2.1. The Northeast Ohio Climate Action Community Voices Project

- Depicts examples of climate concern and action

- Depicts a diversity of messengers that include a range of political affiliations, race and ethnicity, occupation, age, and urban vs. rural locality

- Emphasizes concern for future generations

- Expresses hope

- Expresses urgency

- Emphasizes: economic feasibility or gain of actions taken, equity and justice, civic engagement and/or health

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Measures

- Manipulation check/norm awareness. Participants responded to the item “I am aware of what others think about climate change” on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree). This item was designed to be a manipulation check, to ensure that participants exposed to climate content were aware that they had been exposed to it.

- Descriptive and Prescriptive Climate Norms. Participants responded to six questions based on items from the YPCCC’s “Climate Opinion Maps” survey [2]. Four items measured descriptive norms (e.g., “People in my community are taking action to address climate change”) and two items measured prescriptive norms (e.g., “People have a responsibility to protect the environment for future generations”) on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree). Exploratory factor analysis on all six items with oblimin rotation confirmed that these two factors explained 70% of the variance. Both subscales were reliable: descriptive norm alpha = 0.724, prescriptive norm alpha = 0.749.

- Psychological Distance of Climate Change. On a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree), survey participants rated agreement with statements designed to measure spatial, social, and temporal psychological distance (e.g., “Serious effects of climate change will mostly occur in communities far away from here”, “I don’t see myself as someone who will experience the effects of climate change”). The scale was reliable; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.805.

- Envisioning a Positive Environmental Future. Participants completed a subset of the Environmental Cognitive Alternatives Scale (ECAS), a 10-item scale designed to measure “the ability to imagine what a sustainable relationship between humans and the rest of nature might look like” [25]. Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree) to items such as, “It is easy to imagine a world where we no longer use fossil fuels”. The scale was reliable; Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.834.

- Positive and negative emotions. Using a four-point scale (1 = Not at all, 2 = Slightly, 3 = Moderately, 4 = Strongly), survey participants reported their levels of 9 different emotions in response to the prompt “How strongly do you feel each of the following emotions when you think about the issue of climate change?”. The four positive emotions (hopeful, brave, resilient and optimistic) and five negative emotions (guilty, angry, betrayed, sad and afraid) were presented in random order. Both scales were reliable, negation emotions Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.87, positive emotions Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.84.

- Efficacy. We used two items to measure participants’ sense of collective efficacy, at the community level, to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Participants read the statement, “consider two different ways that people cope with climate change. Mitigation is when people work to reduce the causes of climate change. This means reducing greenhouse gas emissions and/or removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Adaptation involves anticipating the impacts of a changing climate and taking action to prevent or minimize the damage caused. For example, this might mean installing air-conditioning to deal with extreme heat or installing sea walls to prevent flooding.”

- Policy Support. On a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree), survey participants rated how much they supported using “significant tax dollars” to mitigate climate emissions, adapt to a changing climate, invest in public transit, and invest in renewable energy. The scale was highly reliable; Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.921.

- Demographics. At the end of the study, participants were asked to report on their age, gender, education level, income, ethnicity, political orientation (measured on a seven-point scale between conservative and liberal), and rural, suburban or urban locality. These are reported in Table 1.

3. Results

3.1. Evaluating the Impact of Community Voices

3.2. Evaluating the Impact of Regional Content

3.3. Testing for Mediation of Effects on Policy Support

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Exposure to Pro-Social and Climate Action-Focused CV on Social Norms

4.2. Differences in Response Between NE Ohio Sample and National Sample

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E.; Rosenthal, S.; Kotcher, J.; Goddard, E.; Carman, J.; Ballew, M.; Verner, M.; Myers, T.; Marlon, J.; et al. Climate Change in the American Mind: Beliefs & Attitudes, Spring 2024; Yale University and George Mason University: New Haven, CT, USA, 2024; Available online: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/app/uploads/2024/07/climate-change-american-mind-beliefs-attitudes-spring-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- IPSOS. Global Commons Survey 2024. Earth4All. 2024. Available online: https://earth4all.life/global-survey-2024/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Cialdini, R.B. Influence, New and Expanded: The Psychology of Persuasion; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkman, G.; Geiger, N.; Weber, E.U. Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Allport, F.H. Students’ Attitudes: A Report of the Syracuse University Reaction Study; Craftsman Press: Syracuse, NY, USA, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, D.A.; Miller, D.T. Pluralistic ignorance and the perpetuation of social norms by unwitting actors. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 1, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, S.M.; Sparkman, G.; Kraft-Todd, G.T.; Bicchieri, C.; Centola, D.; Shell-Duncan, B.; Vogt, S.; Weber, E.U. Scaling up change: A critical review and practical guide to harnessing social norms for climate action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2022, 23, 50–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, C.M. To create serious movement on climate change, we must dispel the myth of indifference. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M.; Schultz, P.W.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. Normative social influence is underdetected. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsen, K. Unleashing the Power of Digital Signage: Content Strategies for the 5th Screen; Taylor & Francis: Burlington, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.E.; Frantz, C.M. Changing culture through pro-environmental messaging delivered on digital signs: A longitudinal field study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, C.M.; Petersen, J.; Lucaites, K. Novel approach to delivering pro-environmental messages significantly shifts norms and motivation, but children are not more effective spokespeople than adults. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, J.E.; Frantz, C.M.; Shammin, M. Using sociotechnical feedback to engage, educate, motivate, and empower environmental thought and action. Solutions 2014, 5, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, A.; Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N. The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lange, P.A.M.; Huckelba, A.L. Psychological distance: How to make climate change less abstract and closer to the self. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, L.S.; Spence, A. Reducing, and bridging, the psychological distance of climate change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.S.; Zwickle, A.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Wilson, R. The perceived psychological distance of climate change impacts and its influence on support for adaptation policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 73, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Dessai, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Morton, T.A.; Pidgeon, N.F. Psychological responses to the proximity of climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Valkengoed, A.M.; Steg, L.; Perlaviciute, G. The psychological distance of climate change is overestimated. One Earth 2023, 6, 362–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hurlstone, M.J.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I.; Lawrence, C. Climate change from a distance: An analysis of construal level and psychological distance from climate change. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 438569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.D.; Schmitt, M.T.; Mackay, C.M.L.; Neufeld, S.D. Imagining a sustainable world: Measuring cognitive alternatives to the environmental status quo. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.E.; Schmitt, M.T.; Mackay, C.M.L.; Wright, J.D. Experimentally elevating environmental cognitive alternatives: Effects on activist identification, willingness to act, and opposition to new fossil fuel projects. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 101, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.R.; Zaval, L.; Markowitz, E.M. Positive emotions and climate change. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, L. The power of positive role models: Youth climate activism in films. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2021, 11, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S.; Nicholson-Cole, S. “Fear won’t do it”: Promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shome, D.; Marx, S.; Appelt, K.; Arora, P.; Balstad, R.; Freedman, A.; Handgraaf, M.; Hardisty, D.; Krantz, D.; Leiserowitz, A.; et al. The Psychology of Climate Change Communication: A Guide for Scientists, Journalists, Educators, Political Aides, and the Interested Public; Center for Research on Environmental Decisions, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, T.A.; Maibach, E. Emotional responses to climate change information and their effects on policy support. Front. Clim. 2023, 5, 1135450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K.; van den Broek, K.L.; Bhullar, N.; Aquino, S.D.; Marot, T.; Schermer, J.A.; et al. Climate anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental action: Correlates of negative emotional responses to climate change in 32 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Parodi, G.; Feygina, I. Engaging people on climate change: The role of emotional responses. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 571–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohio Secretary of State. Results by County [Excel File]. 2024 General Election Results. 2024. Available online: https://www.ohiosos.gov/globalassets/elections/2024/gen/official/statewide-race-summary.xlsx (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency. Cleveland-Elyria Metropolitan Statistical Area Priority Climate Action Plan. eNEO2050, 2024, March. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-02/cleveland-elyria-msa-pcap.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- City of Cleveland Mayor’s Office of Sustainability & Climate Justice. Draft Cleveland Climate Action Plan. City of Cleveland. 2024. Available online: https://www.clevelandohio.gov/city-hall/office-mayor/sustainability/cleveland-climate-action-plan (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- US Census Bureau. RACE. Decennial Census, DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171), Table P1. Available online: https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALPL2020.P1?q=2020+decennial+P1 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- US Census Bureau. RACE. Decennial Census, DEC Demographic and Housing Characteristics, Table P8. Available online: https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALDHC2020.P8?q=2020+decennial+P8 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q.; Coronado-Medina, A.; Arias-Pérez, J.; Perdomo-Charry, G.; Pérez, E.; Tavits, M.; Qin, X.; Liu, X.; et al. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.A.K.; Nelson, L.D.; Steele, C.M. Do messages about health risks threaten the self? Increasing the acceptance of threatening health messages via self-affirmation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 1046–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.R.; Napper, L. Self-affirmation and the biased processing of threatening health-risk information. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Koningsbruggen, G.M.; Das, E.; Roskos-Ewoldsen, D.R. How self-affirmation reduces defensive processing of threatening health information: Evidence at the implicit level. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palm, R.; Bolson, T. Climate Change and Sea Level Rise in South Florida; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenefeld, J.J.; McCauley, M.R. Local is not always better: The impact of climate information on values, behavior and policy support. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2016, 6, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Pidgeon, N. Framing and communicating climate change: The effects of distance and outcome frame manipulations. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovins, L.H.; Wallis, S.; Wijkman, A.; Fullerton, J. A Finer Future: Creating an Economy in Service to Life; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.W.; Prentice-Dunn, S. Protection Motivation Theory and preventive health: Beyond the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Res. 1986, 1, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothe, E.J.; Ling, M.; North, M.; Klas, A.; Mullan, B.A.; Novoradovskaya, L. Protection motivation theory and pro-environmental behaviour: A systematic mapping review. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable (N = 978) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| 707 | 72.2 |

| 138 | 14.1 |

| 51 | 5.2 |

| 42 | 4.3 |

| 7 | 0.7 |

| 6 | 0.6 |

| 27 | 2.8 |

| Income Level | ||

| 214 | 21.9 |

| 334 | 34.2 |

| 299 | 30.5 |

| 131 | 13.4 |

| Education Level | ||

| 122 | 12.5 |

| 29 | 3.0 |

| 197 | 20.1 |

| 78 | 8.0 |

| 348 | 35.5 |

| 204 | 53.0 |

| Urban vs. Rural Locality | ||

| 260 | 26.6 |

| 565 | 57.7 |

| 153 | 15.6 |

| Political Orientation | ||

| 188 | 19.2 |

| 140 | 14.3 |

| 118 | 12.1 |

| 186 | 19.0 |

| 121 | 12.4 |

| 119 | 12.2 |

| 106 | 10.8 |

| Gender | Education Level | Income Level | Ethnicity | Political Orientation | Urban vs. Rural Locality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Norm Awareness (Manipulation Check) | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 ** | −0.08 * | −0.03 | −0.04 |

| Descriptive Climate Norms | 0.01 | 0.18 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.15 ** |

| Prescriptive Climate Norms | 0.15 * | 0.07 * | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.43 ** | −0.13 ** |

| Psychological Distance | −0.18 ** | 0.01 | 0.07 * | −0.02 | 0.39 ** | 0.05 |

| Negative Emotions | −0.07 * | 0.09 ** | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.15 ** | −0.01 ** |

| Positive Emotions | 0.12 ** | −0.03 | −0.09 ** | −0.04 | −0.43 ** | −0.07 ** |

| Policy Support | 0.12 ** | 0.07 | −0.04 ** | 0.06 | −0.51 ** | −0.17 ** |

| Mitigation Efficacy | 0.08 * | 0.12 ** | 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.09 ** | −0.08 * |

| Adaptation Efficacy | −0.05 | 0.11 ** | 0.12 ** | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.07 |

| Exposure Group | No Exposure N = 314 | Pro-social Exposure N = 310 | Climate Action Exposure N = 270 | Main Effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | F (2886) | p | Eta Sq | |

| Climate Norm Awareness (Manipulation Check) | 3.97 a | (0.99) | 4.12 a | (0.70) | 4.259 b | (0.72) | 8.961 | <0.001 ** | 0.02 |

| Descriptive Climate Norms | 3.14 a | (0.80) | 3.32 b | (0.079) | 3.44 c | (0.81) | 10.63 | <0.001 ** | 0.02 |

| Prescriptive Climate Norms | 4.30 a | (0.93) | 4.49 b | (0.68) | 4.42 b | (0.86) | 5.02 | 0.007 ** | 0.01 |

| Psychological Distance | 2.46 a | (0.97) | 2.20 b | (0.86) | 2.25 b | (0.95) | 7.75 | <0.001 ** | 0.02 |

| ECAS | 3.16 a | (1.06) | 3.27 a | (0.95) | 3.20 a | (1.01) | 1.17 | 0.31 | 0.00 |

| Mitigation Efficacy | 2.57 a | (0.84) | 2.69 a | (0.74) | 2.61 a | (0.85) | 1.28 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| Adaptation Efficacy | 3.03 a | (0.74) | 2.95 a | (0.75) | 3.01 a | (0.77) | 0.97 | 0.38 | 0.00 |

| Negative Emotions | 2.20 a | (0.81) | 2.20 a | (0.74) | 2.25 a | (0.81) | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.00 |

| Positive Emotions | 2.13 a | (0.87) | 2.30 b | (0.86) | 2.10 a | (0.75) | 6.00 | 0.00 ** | 0.01 |

| Policy Support | 3.60 a | (1.20) | 3.81 b | (0.91) | 3.69 ab | (1.12) | 3.76 | 0.02 * | 0.01 |

| No Exposure | Pro-Social Exposure | Climate Action Exposure | Exposure Group × Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV | Sample | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | F(2886) | p | Eta Sq |

| Climate Norm Awareness (Manipulation Check) | NE Ohio | 3.98 (1.03) | 4.13 (0.68) | 4.28 (0.72) | 0.005 | 0.10 | 0.000 |

| National | 3.96 (0.96) | 4.10 (0.72) | 4.24 (0.75) | ||||

| Descriptive Climate Norms | NE Ohio | 3.13 (0.84) | 3.30 (0.76) | 3.51 (0.79) | 1.14 | 0.32 | 0.003 |

| National | 3.14 (0.80) | 3.35 (0.83) | 3.68 (0.84) | ||||

| Prescriptive Climate Norms | NE Ohio | 4.39 (0.80) | 4.49 (0.66) | 4.40 (0.83) | 1.85 | 0.16 | 0.004 |

| National | 4.20 (1.03) | 4.48 (0.69) | 4.43 (0.88) | ||||

| Psychological Distance | NE Ohio | 2.46 (0.96) | 2.25 (0.83) | 2.35 (0.92) | 0.95 | 0.39 | 0.002 |

| National | 2.45 (0.98) | 2.15 (0.90) | 2.15 (0.96) | ||||

| ECAS | NE Ohio | 3.24 (1.03) | 3.27 (0.93) | 3.04 (0.97) | 4.31 | 0.01 * | 0.01 |

| National | 3.069 (1.07) | 3.28 (0.96) | 3.35 (1.04) | ||||

| Mitigation Efficacy | NE Ohio | 2.60 (0.79) | 2.74 (0.68) | 2.60 (0.82) | 0.26 | 0.77 | 0.001 |

| National | 2.54 (0.88) | 2.64 (0.81) | 2.60 (0.90) | ||||

| Adaptation Efficacy | NE Ohio | 3.01 (0.69) | 2.98 (0.69) | 2.99 (0.77) | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.001 |

| National | 3.03 (0.78) | 2.94 (0.83) | 3.09 (0.77) | ||||

| Negative Emotions | NE Ohio | 2.26 (0.81) | 2.21 (0.73) | 2.23 (0.78) | 0.71 | 0.49 | 0.002 |

| National | 2.15 (0.80) | 2.19 (0.76) | 2.27 (0.84) | ||||

| Positive Emotions | NE Ohio | 2.30 (0.82) | 2.39 (0.81) | 2.10 (0.76) | 3.79 | 0.02 | 0.008 |

| National | 1.95 (0.85) | 2.20 (0.90) | 2.09 (0.73) | ||||

| Policy Support | NE Ohio | 3.69 (1.13) | 3.79 (0.91) | 3.61 (1.14) | 2.45 | 0.09 | 0.006 |

| National | 3.51 (1.25) | 3.82 (0.92) | 3.77 (1.10) | ||||

| Dependent Variable = Climate Change Policy Support | |||||

| Community Voices vs. no Community Voices | Bootstrapped 95% CI | ||||

| Mediator | Effect of IV on Mediator (SE) | Unique Effect of Mediator (SE) | Indirect Effect (SE) | Lower | Upper |

| Descriptive Norms | 0.243 (0.056) *** | 0.082 (0.029) ** | 0.020 (0.008) ** | 0.006 | 0.038 |

| Prescriptive Norms | 0.161 (0.052) *** | 0.606 (0.038) *** | 0.097 (0.035) ** | 0.030 | 0.167 |

| Psychological Distance | −0.222 (0.059) *** | −0.167 (0.032) *** | 0.037 (0.013) ** | 0.020 | 0.065 |

| Positive Emotions | 0.090 (0.053) | 0.233 (0.034) *** | 021 (0.013) | −0.004 | 0.047 |

| Complete Model R2 = 0.614, F(7, 886) = 201.55, p < 0.001. Total effect of IV on DV: b = 0.148, p = 0.024. | |||||

| Pro-social Community Voices vs. no Community Voices | Bootstrapped 95% CI | ||||

| Mediator | Effect of IV on mediator (SE) | Unique effect of mediator (SE) | indirect effect (SE) | Lowe | Upper |

| Descriptive Norms | 0.186 (0.064) ** | 0.059 (0.037) | 0.011 (0.007) | −0.001 | 0.027 |

| Prescriptive Norms | 0.196 (0.060) *** | 0.648 (0.045) *** | 0.127 (0.040) *** | 0.049 | 0.207 |

| Psychological Distance | −0.252 (0.069) *** | −0.213 (0.038) *** | 0.054 (0.019) ** | 0.021 | 0.093 |

| Positive Emotions | 0.185 (0.063) ** | 0.216 (0.040) *** | 0.040 (0.016) *** | 0.011 | 0.074 |

| Complete Model R2 = 0.578, F(7, 616) = 120.34, p < 0.001. Total effect of IV on DV: b = 0.211, p = 0.005. | |||||

| Climate change Community Voices vs. no Community Voices | Bootstrapped 95% CI | ||||

| Mediator | Effect of IV on Mediator (SE) | Unique Effect of Mediator (SE) | Indirect Effect (SE) | Lower | Upper |

| Descriptive Norms | 0.312 (0.067) *** | 0.087 (0.036) * | 0.027 (0.012) * | 0.00 | 0.053 |

| Prescriptive Norms | 0.126 (0.066) * | 0.652 (0.045) *** | 0.082 (0.043) | −0.002 | 0.167 |

| Psychological Distance | −0.194 (0.072) ** | −0.158 (0.041) *** | 0.031 (0.015) * | 0.0096 | 0.065 |

| Positive Emotions | −0.018 (0.060) | 0.236 (0.044) *** | −0.004 (0.014) | −0.034 | 0.023 |

| Complete Model R2 = 0.653, F(7, 576) = 154.57, p < 0.001. Total effect of IV on DV: b = 0.082, p = 0.316. | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kearney, B.; Petersen, J.E.; Frantz, C.M. Overcoming Pluralistic Ignorance—Brief Exposure to Positive Thoughts and Actions of Others Can Enhance Social Norms Related to Climate Action and Support for Climate Policy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210318

Kearney B, Petersen JE, Frantz CM. Overcoming Pluralistic Ignorance—Brief Exposure to Positive Thoughts and Actions of Others Can Enhance Social Norms Related to Climate Action and Support for Climate Policy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210318

Chicago/Turabian StyleKearney, Bryn, John E. Petersen, and Cynthia McPherson Frantz. 2025. "Overcoming Pluralistic Ignorance—Brief Exposure to Positive Thoughts and Actions of Others Can Enhance Social Norms Related to Climate Action and Support for Climate Policy" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210318

APA StyleKearney, B., Petersen, J. E., & Frantz, C. M. (2025). Overcoming Pluralistic Ignorance—Brief Exposure to Positive Thoughts and Actions of Others Can Enhance Social Norms Related to Climate Action and Support for Climate Policy. Sustainability, 17(22), 10318. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210318