Sustainable Urban Development Through Creative Film Industries: From Hollyłódź to Bollywood

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Creative Industries and Their Relationship to the Film Sector

3.2. The Great Acceleration, the Great Inequality, and the Urgency for Sustainable Development

3.3. Creative Industries and Sustainable Development: A Framework

4. Results

4.1. Łódź Case Study

4.1.1. City Profile

4.1.2. Łódź Film Cluster

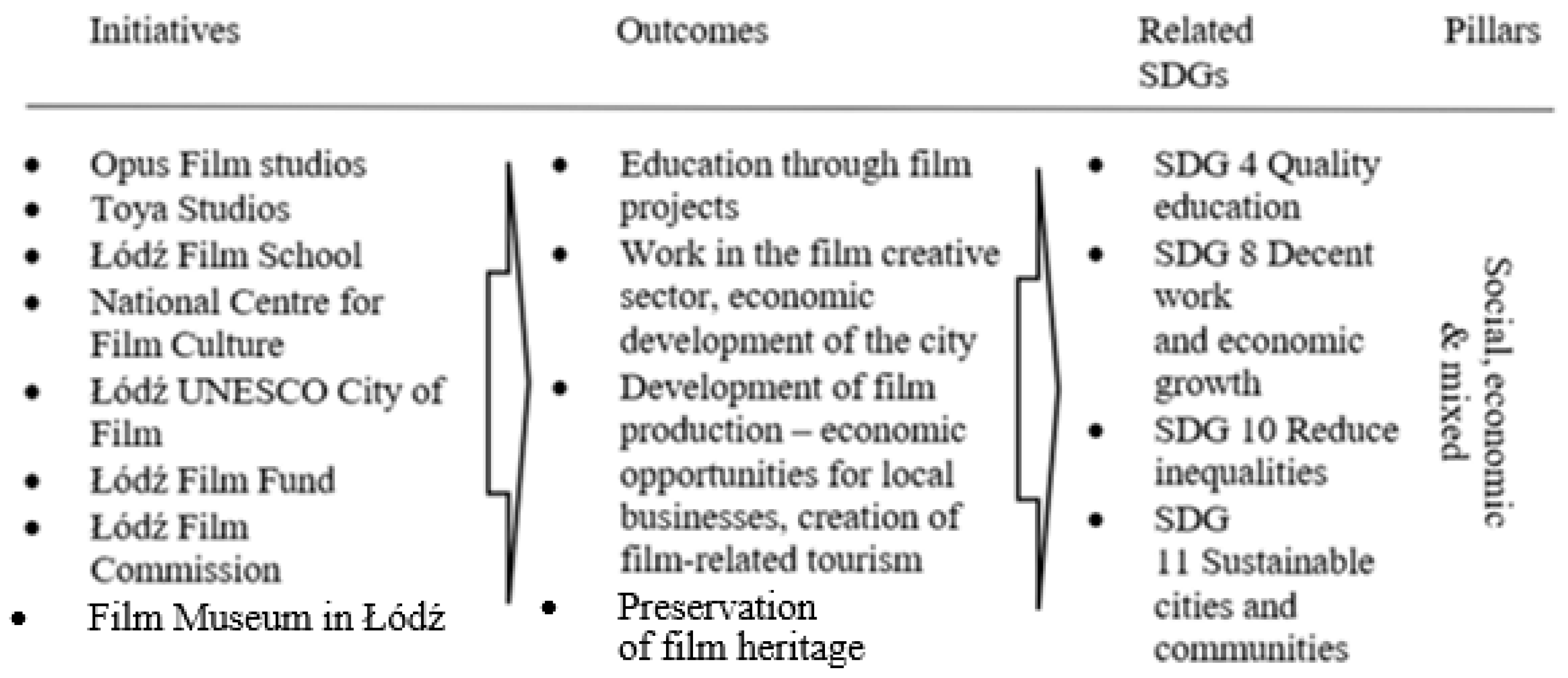

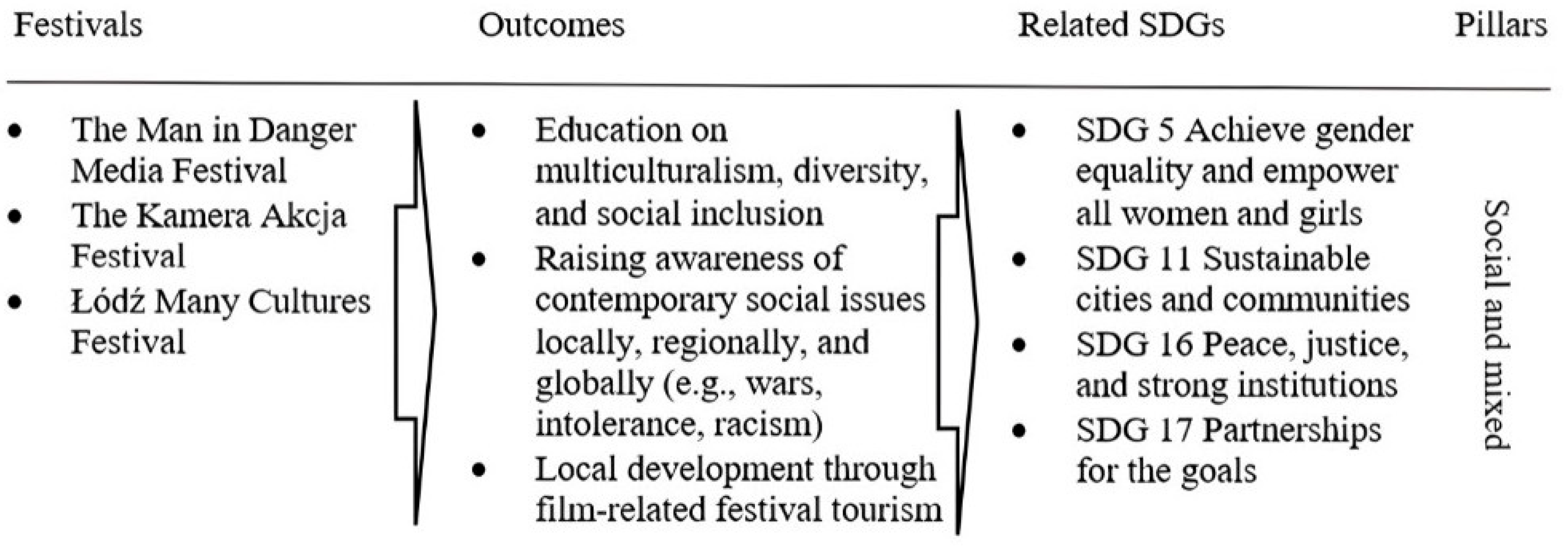

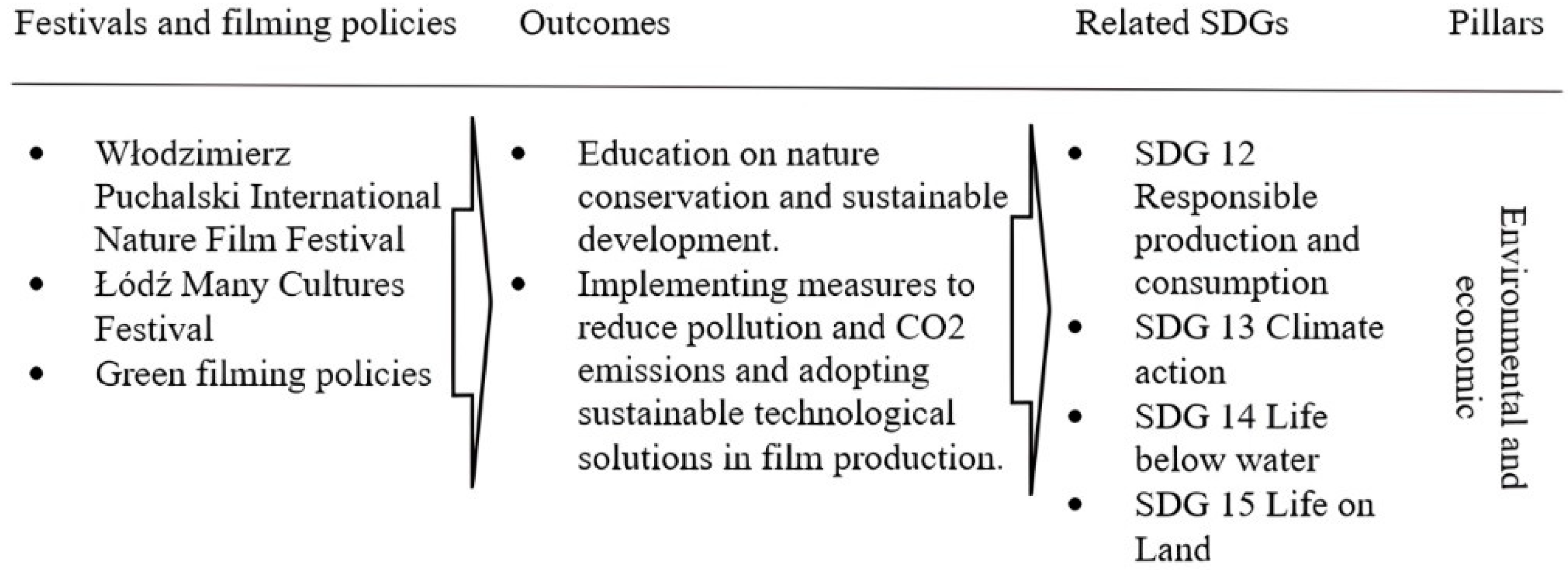

4.1.3. Sustainable Development Perspective

4.2. Mumbai Case Study

4.2.1. City Profile

4.2.2. The Evolution of Bollywood and the Mumbai Film Cluster

4.2.3. Bollywood’s Share and Impact

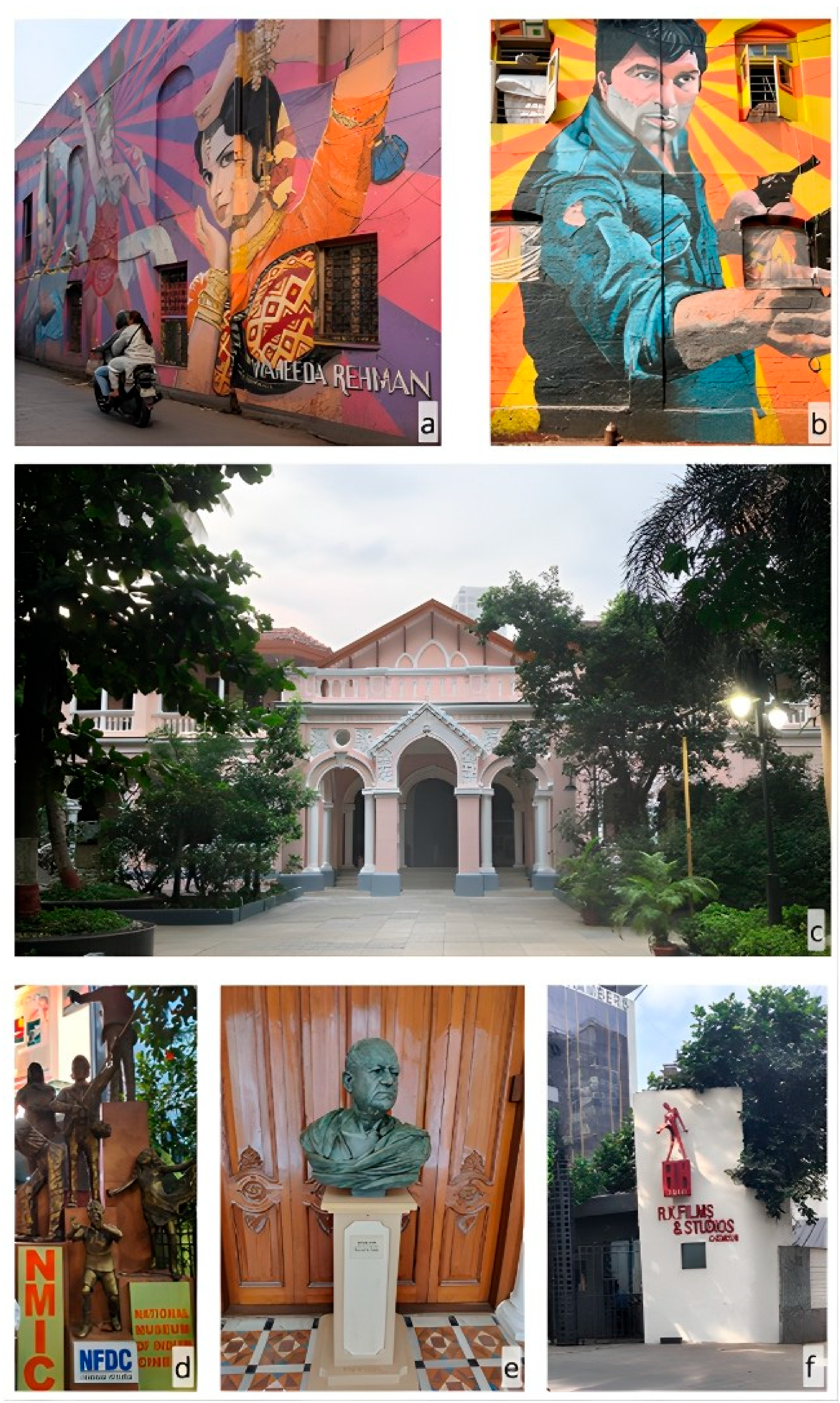

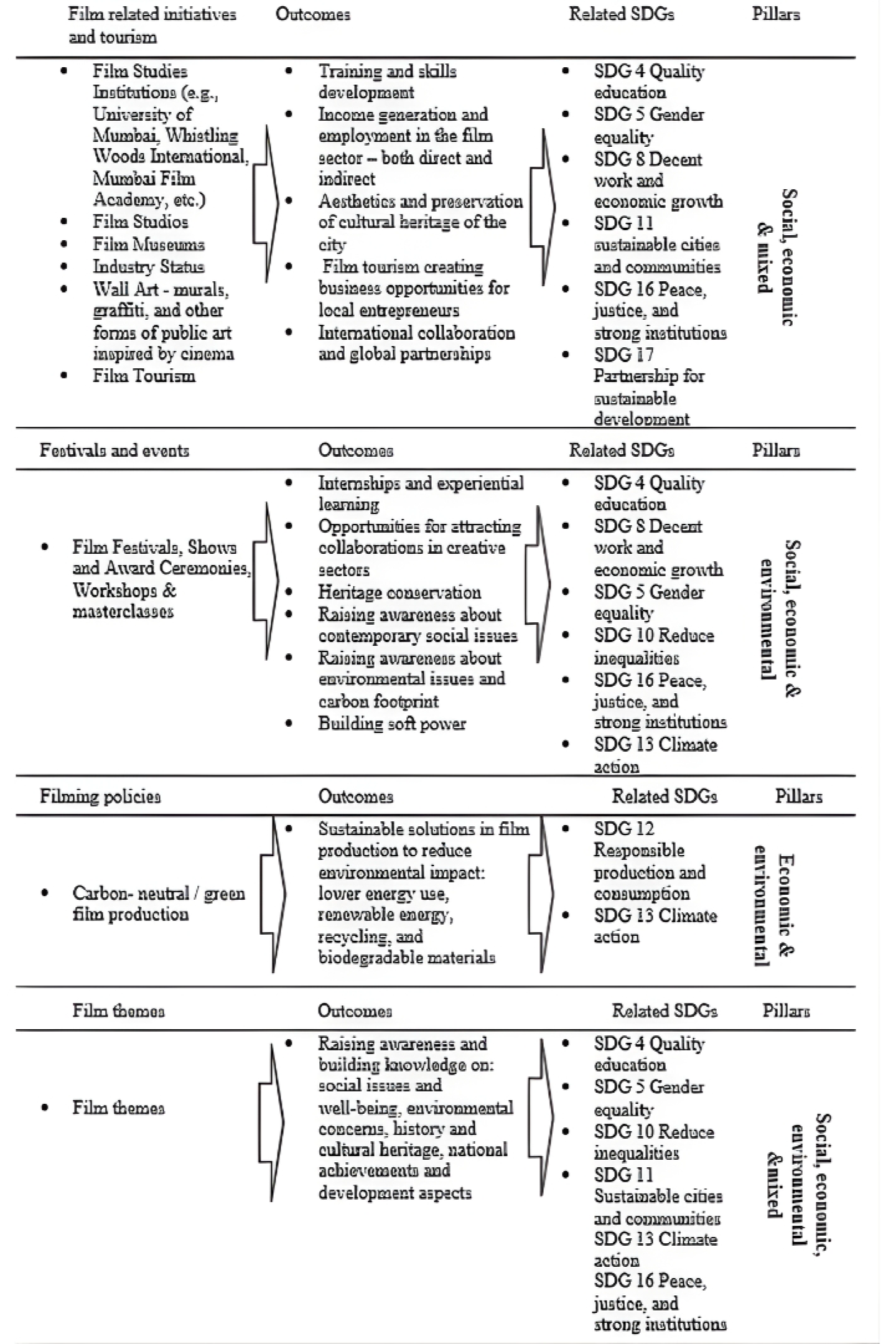

4.2.4. Mumbai Film Industry and Its Contribution to SDGs

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oyekunle, O.A. The contribution of creative industries to sustainable urban development in South Africa. In Science, Technology, and Innovation in BRICS Countries; Patra, S.K., Muchie, M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, D. Rethinking creative cities?: UNESCO, sustainability, and making urban cultures. In Re-Imagining Creative Cities in Twenty-First Century Asia; Gu, X., Lim, M.K., O’Connor, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bertoni, A.; Dubini, P.; Monti, A. Bringing Back in the Spatial Dimension in the Assessment of Cultural and Creative Industries and Its Relationship with a City’s Sustainability: The Case of Milan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comunian, R.; Chapain, C.; Clifton, N. Creative industries & creative policies: A European perspective? City Cult. Soc. 2014, 2, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, S.; Hauerwaas, A.; Holz, V.; Wedler, P. Culture in sustainable urban development: Practices and policies for spaces of possibility and institutional innovations. City Cult. Soc. 2018, 13, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Draper, J.; Malek, K.; Padron, T.C.; Olson, E. Bridging theory and practice: An examination of how event-tourism research aligns with UN sustainable development goals. J. Travel Res. 2024, 63, 1583–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Turkina, E.; Van Assche, A. The nexus between the cultural and creative industries and the Sustainable Development Goals: A network perspective. Reg. Stud. 2024, 58, 841–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, J.; Wood, E.; Quinn, B. Social sustainability in Event Management- a critical commentary. Event Manag. 2024, 28, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, B. Cultural policy and urban regeneration in Western European cities: Lessons from experience, prospects for the future. Local Econ. 2004, 19, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victory, J. Green shoots: Environmental sustainability and contemporary film production. Stud. Arts Humanit. 2015, 1, 54–68. Available online: https://www.sahjournal.com/article/6006/galley/13750/view (accessed on 30 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- McCormack, C.M.; Martin, K.; Williams, K.J. The full story: Understanding how films affect environmental change through the lens of narrative persuasion. People Nat. 2021, 3, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudny, W. Festival tourism—The concept, key functions and dysfunctions in the context of tourism geography studies. Geogr. J. 2013, 65, 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchberg, V.; Kagan, S. The roles of artists in the emergence of creative sustainable cities: Theoretical clues and empirical illustrations. City Cult. Soc. 2013, 4, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kääpä; P. Environmental Management of the Media: Policy, Industry, Practice; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lopera-Mármol, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M. Green shooting: Media sustainability, a new trend. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, K. Green Filmmaking: A Guide to Sustainable Movie Production; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tunio, M.N.; Sánchez, A.; Hatem, Y.M.L.; Zakaria, A.M. (Eds.) Sustainability in Creative Industries: Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Creative Innovations—Volume 1; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, C. Postcolonial Bombay: Decline of a cosmopolitanism city? Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2008, 26, 480–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A. Postcolonial Mumbai: The paradoxical city. In From the City as a Project to the City Project Volume I: History; Mena, F.C., Alvarez, S.R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, R. Provincializing the global city: From Bombay to Mumbai. Soc. Text 2004, 22, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, B. Urbanism, mobility and Bombay: Reading the postcolonial city. J. Postcolonial Writ. 2011, 47, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudny, W. Socio-Economic Changes in Lodz–Results of Twenty Years of System Transformation. Geogr. Časopis 2012, 64, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D.C. Is the post-in postcolonial the post-in post-Soviet? Toward a global postcolonial critique. Publ. Mod. Lang. Assoc. 2001, 116, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandru, C. Worlds Apart? A Postcolonial Reading of Post-1945 East-Central European Culture; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tlostanova, M.V.; Mignolo, W. Learning to Unlearn: Decolonial Reflections from Eurasia and the Americas; The Ohio State University Press: Columbus, OH, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola, E. Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L.L.; Goldberg, C.B. Editors’ comment: So, what is a conceptual paper? Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/creative-cities/lodz (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: https://citiesoffilm.org/mumbai/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.opusfilm.com/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- The National Centre for Film Culture in Lodz. Available online: https://ec1lodz.pl/narodowe-centrum-kultury-filmowej/o-nckf/czym-jest-nckf2 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Chenoy, D. Foreword in Film Tourism in India—A Beginning Towards Unlocking Its Potential. FICCI. 2019. Available online: https://creativefirst.film/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Low-resolution_EY-FICCI_Shoot-at-site1.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Dematdive. How Much Can the Indian Film Industry Contribute to the Indian Economy: 2023 and Beyond? 2023. Available online: https://dematdive.com/indian-film-industry/#:~:text=In%20the%20third%20quarter%20of,and%20resurgence%20post%20the%20pandemic (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Pożycka, P. Łódź—Miasto Kreatywne: Badanie Potencjału Kreatywnego Łodzi na tle Wybranych Miast Polski; University of Łódź: Łódź, Poland, 2012; Available online: https://nck.pl/upload/attachments/302509/d_miasto_kreatywne.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Sangeet Natak Akademi. Ministry of Culture, Government of India; Creative Cities Network: Mumbai, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, T.W.; Horkheimer, M.K. Aufklärung als Massenbetrug. In Dialektik der Aufklärung; Adorno, T.W., Ed.; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1947; pp. 141–191. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, W. Illuminations: Essays and Reflections; Zohn, H., Translator; Fontana: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, J. The Cultural and Creative Industries: A Review of the Literature; Arts Council England: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, S. Cunningham, S. Culture, services, knowledge: Television between policy regimes. In A Companion to Television; Wasko, J., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hesmondhalgh, D.; Pratt, A.C. Cultural industries and cultural policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2005, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R. Cities and the creative class. City Community 2003, 2, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, S.; Dunlop, S. A critique of definitions of the cultural and creative industries in public policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2007, 13, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turok, I. Cities, clusters, and creative industries: The case of film and television in Scotland. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2003, 11, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loots, E.; Betzler, D.; Bille, T.; Borowiecki, K.J.; Lee, B. New forms of finance and funding in the cultural and creative industries: Introduction to the special issue. J. Cult. Econ. 2022, 46, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, J.; Cunningham, S.; Hartley, J.; Ormerod, P. Social network markets: A new definition of the creative industries. J. Cult. Econ. 2008, 32, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A. Creative cities: The cultural industries and the creative class. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2008, 90, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J. Beyond the creative city: Cognitive–cultural capitalism and the new urbanism. Reg. Stud. 2014, 48, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J.K. The New Industrial State; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, V.R. The Service Economy; National Bureau of Economic Research Distributed by Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Touraine, A. La Société Post-Industrielle; Editions Denoël: Paris, France, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society: The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1996; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cudny, W.; Comunian, R.; Wolaniuk, A. Arts and creativity: A business and branding strategy for Lodz as a neoliberal city. Cities 2020, 100, 102659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, F. Remaking European cities: The role of cultural politics. In Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration: The West European Experience; Bianchini, F., Parkinson, M., Eds.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 1993; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Milestone, K. Regional variations: Northernness and new urban economies of hedonism. In From the Margins to the Centre: Cultural Production and Consumption in the Post-Industrial City; O’Connor, J., Wynne, D., Eds.; Arena: Aldershot, UK, 1996; pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Creativity and tourism in the city. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Bie, C. Creative class agglomeration across time and space in knowledge city: Determinants and their relative importance. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, C. The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators; Earthscan Publications: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Howkins, J. The Creative Economy: How People Make Money from Ideas; Penguin: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. Creative cities, creative spaces and urban policy. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1003–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J. Struggling with the creative class. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2005, 29, 740–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratiu, D.E. Creative cities and/or sustainable cities: Discourses and practices. City Cult. Soc. 2013, 4, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hoeven, A.; Hitters, E. Live music and the New Urban Agenda: Social, economic, environmental and spatial sustainability in live music ecologies. City Cult. Soc. 2023, 32, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Gibson, C.; Khoo, L.M.; Semple, A.L. Knowledges of the creative economy: Towards a relational geography of diffusion and adaptation in Asia. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2006, 47, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Valck, M. Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, A. Creative class politics: Unions and the creative economy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2016, 22, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudny, W. The Influence of The “KOMISARZ Alex” TV Series on The Development of Łódź (Poland) in The Eyes of City Inhabitants. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2014, 22, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namyślak, B. Cooperation and Forming Networks of Creative Cities: Polish Experiences. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 2411–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, M.; Croy, W.G. Film tourism: Integrated strategic tourism and regional economic development planning. Tour. Anal. 2015, 20, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Broadgate, W.; Deutsch, L.; Gaffney, O.; Ludwig, C. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The great acceleration. Anthr. Rev. 2015, 2, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.C. Anthropocene: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Volume 558. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, L.E.; Bauer, A.; Edgeworth, M.; Ellis, E.; Finney, S.; Gibbard, P.; Gill, J.L.; Maslin, M.; Merritts, D.; Ruddiman, W.; et al. The Anthropocene serves science better as an event, rather than an epoch. J. Quat. Sci. 2022, 37, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshitaishvili, B. From Anthropocene to noosphere: The great acceleration. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, A.J. Planetary Overload: Global Environmental Change and the Health of the Human Species; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Görg, C.; Plank, C.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Mayer, A.; Pichler, M.; Schaffartzik, A.; Krausmann, F. Scrutinizing the Great Acceleration: The Anthropocene and its analytic challenges for social-ecological transformations. Anthr. Rev. 2020, 7, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brou, D.; Chatterjee, A.; Coakley, J.; Girardone, C.; Wood, G. Corporate governance and wealth and income inequality. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2021, 29, 612–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.K.M. The economic marginality of ethnic minorities: An analysis of ethnic income inequality in Singapore. Asian Ethn. 2004, 5, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Sachs, J.D. The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-D. Event and Sustainable Culture-Led Regeneration: Lessons from the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Liverpool. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, J. The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning; Common Ground Publishing: Altona, VIC, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Soini, K.; Dessein, J. Culture-sustainability relation: Towards a conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Sun, Y.; Lin, P.-H.; Lin, R. Sustainable Development in Local Culture Industries: A Case Study of Taiwan Aboriginal Communities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A. Turystyka Zrównoważona; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N.; Cullen, C.; Pascual, J. Cities, culture and sustainable development. In Cultural Policy and Governance in a New Metropolitan Age, Cultures and Globalization Series; Anheier, H.K., Isar, Y.R., Hoelscher, M., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2012; Volume 5, pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R. Sustainable urban development: Definition and reasons for a research programme. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 1998, 10, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Agenda 21: Programme of Action for Sustainable Development. United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), Rio de Janeiro. 1992. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/outcomedocuments/agenda21 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- United Nations. The Habitat Agenda: Istanbul Declaration on Human Settlements. United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II). 1996. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/habitat/istanbul1996 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- United Nations. The New Urban Agenda. United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III). 2016. Available online: https://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Kopeć, K.; Materska-Samek, M. Green Filming in Poland. An Interplay Between Necessity, Environmental Responsibility and Green Incentives. Eduk. Ekon. I Menedżerów 2024, 68, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutalov, S.; Iastremska, O.; Kulinich, T.; Shofolova, N.; Zelenko, O. Symbiosis of Creativity and Sustainability: Modelling the Dynamic Relationship Between Sustainable Development and Cultural and Creative Industries in the EU Countries, Great Britain and Ukraine. Probl. Ekorozwoju 2024, 2, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; Geng, H. Digital Creative Industries in the Yangtze River Delta: Spatial Diffusion and Response to Regional Development Strategy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, G.; Bifulco, F. Sustainability in Purpose-Driven Businesses Operating in Cultural and Creative Industries: Insights from Consumers’ Perspectives on Società Benefit. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyykkönen, M.; De Beukelaer, C. What is the role of creative industries in the Anthropocene? An argument for planetary cultural policy. Poetics 2025, 109, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hana, N.; Kondrateva, G.; Martin, S. Emission-smart advertising: Balancing performance with CO2 emissions in digital advertising. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 209, 123818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Pai, C.H. Promoting carbon neutrality and green growth through cultural industry financing. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, E.S.; Pinheiro, R.M.; Zyzak, B. Knowledge bases and regional development: Collaborations between higher education and cultural creative industries. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2018, 24, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, H. Indigenous festivals in the Pacific: Cultural renewal, decolonization and nation-building. Pac. Am. Stud. 2020, 20, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, T.; Stadler, R.; Jepson, A.S. Positive power: Events as temporary sites of power which “empower” marginalised groups. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 2391–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, F.; Lewis, C.; Prayag, G. This is what being queer looks like: The roles LGBTQ+ events play for queer people based on their social identity. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündüz Özdemirci, E. Greening the screen: An environmental challenge. Humanities 2016, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubitt, S. Unsustainable cinema: Global supply chains. In Ecocinema Theory and Practice 2, 1st ed.; Rust, S., Monani, S., Cubitt, S., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, A.C. The cultural contradictions of the creative city. City Cult. Soc. 2011, 2, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, H. Hollywood’s Dirtiest Secret: The Hidden Environmental Costs of the Movies; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, L.U. Let’s Deal with the Carbon Footprint of Streaming Media. Afterimage J. Media Arts Cult. Crit. 2020, 47, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, L.U.; Przedpełski, R. The carbon footprint of streaming media: Problems, calculations, solutions. In Film and Television Production in the Age of Climate Crisis: Towards a Greener Screen; Kääpä, P., Vaughan, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 207–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, H.; Kääpä, P.; Hjort, M. ‘Film education and the environment’—Special issue of the Film Education Journal. Film. Educ. J. 2025, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlin, G. Sustainable filmmaking: Understanding image as resource. Teach. Media Q. 2016, 4, 1–10. Available online: http://pubs.lib.umn.edu/tmq/vol4/iss3/4 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Jones, C. Greening the screen: Environmental sustainability and film production. In The Routledge Handbook of Sustainable Film; Mundy, P.C., Sundaram, S., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, H.; Kääpä, P. Introduction: Film and television production in the era of accelerated climate change—A greener screen? In Film and Television Production in the Age of Climate Crisis; Vaughan, H., Kääpä, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. The Cultural Economy of Cities: Essays on the Geography of Image-Producing Industrie; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liszewski, S.; Young, C. A Comparative Study of Łódź and Manchester: Geographies of European Cities in Transition; University of Łódź: Łódź, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kazimierczak, J.; Szafrańska, E. Demographic and morphological shrinkage of urban neighbourhoods in a post-socialist city: The case of Łódź, Poland. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2019, 101, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpakowska-Loranc, E.; Matusik, A. Łódź–Towards a resilient city. Cities 2020, 107, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, M.; Wawrzyniak, M.; Jonas, A. Przewodnik po Filmowej Łodzi; Centrum Inicjatyw na rzecz Rozwoju "Regio”: Łódź, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://lodz.travel/turystyka/co-zobaczyc/lodz-filmowa/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.filmschool.lodz.pl/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: https://lodzcityoffilm.com/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: http://toyastudios.pl/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: https://czlowiekwzagrozeniu.pl/o-festiwalu/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: https://kameraakcja.com.pl/en/homepage/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: https://lodzwielukultur.pl/o-festiwalu/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: http://www.festiwalpuchalskiego.pl/en/about-the-festival (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: https://lodzfilmcommission.pl/aktualnosci/green-filming-w-lodzi (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Shaban, A.M. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Urban and Regional Studies; Orum, A.M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, A.; Vermeylen, F.; Handke, C. Creative Industries in India; Routledge: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Maharashtra. Mumbai City. 2024. Available online: https://mumbaicity.gov.in/history/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Patankar, A.; Patwardhan, A.; Andharia, J.; Lakhani, V. Mumbai City report. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment and Urban Development Planning for Asian Coastal Cities, Bangkok, Thailand, 22–28 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sperling, J.; Romero-Lankao, P.; Beig, G. Exploring citizen infrastructure and environmental priorities in Mumbai, India. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 60, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.K.; Shekhar, R. Problems and development of slums: A study of Delhi and Mumbai. In Sustainable Smart Cities in India: Challenges and Future Perspectives; Sharma, P., Rajput, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 699–719. [Google Scholar]

- MCGM. Mumbai: The Hub of Indian Cinema. Available online: https://www.mcgm.gov.in/irj/go/km/docs/documents/HomePage%20Data/Film%20Industry%20in%20Mumbai.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Available online: https://citiesoffilm.org (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/creative-cities/mumbai (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Curiositea. Mumbai, Wall Art and Bollywood. 2015. Available online: https://indiancuriositea.wordpress.com/2015/06/04/mumbai-wall-art-and-bollywood/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Pal, D.; Dream Factory. A Journal of Politics & Culture. 2021. Available online: https://caravanmagazine.in/reviews-and-essays/dream-factory (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Delloitte. Economic Contribution of the Film and Television Industry in India, 2017. Delloitte Touche Tohmatsu India LLP (DTTILLP). 2018. Available online: https://www.mpa-apac.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/India-ECR-2017_Final-Report.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Chavan, V. Pune: MTDC to Cash in on Popular Film Locales to Boost Tourism. Mumbai Mirror, 29 September 2017. Available online: https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/other/pune-mtdc-to-cash-in-on-popular-film-locales-to-boost-tourism/articleshow/60878734.cms (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- KPMG. Transforming Location into Vacation: A Report on Film Tourism. 2024. Available online: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/in/pdf/2024/03/transforming-location-into-vacation-a-report-on-film-tourism.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Kumar, A. The Popularity of India’s Cinema and the Role of Soft Power. Centre for Studies of Plural Societies. Available online: https://cspsindia.org/the-popularity-of-indias-cinema-and-the-role-of-soft-power (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Broskhan, P.; Rajesh, R. Sustainability communication in Indian film: Are popular Bollywood films promoting sustainable development goals (sdgs)? An analysis of Jhund (2022). Bol. Lit. Oral. 2024, 11, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1069850/bio/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Available online: https://tinyurl.com/y5xz295d (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Available online: https://news.wildlifesos.org/bollywood-actress-alia-bhatt-joins-the-wild-side/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Gautam, N. How Bollywood, OTT Platforms Are Adopting Sustainable Practices to Combat Climate Change. Outlook, Planet, 10 August 2024. Available online: https://www.outlookbusiness.com/planet/industry/how-bollywood-ott-platforms-are-adopting-sustainable-practices-to-combat-climate-change (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chin, W.L.; Nechita, F.; Candrea, A.N. Framing film-induced tourism into a sustainable perspective from Romania, Indonesia and Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C. Sydney’s creative economy: Social and spatial challenges. In Talking About Sydney: Population, Community and Culture in Contemporary Sydney; Freestone, R., Randolph, B., Butler-Bowdon, C., Eds.; UNSW Press: Sydney, Australia, 2006; pp. 185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Klinsky, S.; Golub, A. Justice and sustainability. In Sustainability Science: An Introduction; Heinrichs, H., Martens, P., Michelsen, G., Wiek, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, M.; Wang, F.; Xiang, S.; Lin, B.; Gao, C.; Li, J. Inheritance or variation? Spatial regeneration and acculturation via implantation of cultural and creative industries in Beijing’s traditional compounds. Habitat Int. 2020, 95, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The right to the city. New Left Rev. 2008, 53, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.; Pratt, A. In the social factory? Immaterial labour, precariousness and cultural work. Theory Cult. Soc. 2008, 25, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, J. Creative cities and (un)sustainability: Cultural perspectives. Cultura 2010, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, M.; Lange, B. Paradoxes of the creative city: Contested territories and creative upgrading—The case of Berlin, Germany. Erde 2012, 143, 351–371. [Google Scholar]

| Creative industries (CIs) play a significant role in raising awareness of CO2 emissions and the ecological importance of marine and terrestrial ecosystems through green production, diverse artistic projects, media initiatives, and public campaigns. Through the integration of environmental themes into creative production and cultural expression, CI can cultivate a deeper societal appreciation of ecological values and strengthen collective commitment to the preservation of both marine and land-based ecosystems | Environmental Pillar | ||

| SDG 13—Climate Action Undertake urgent measures to address climate change and mitigate its environmental, social, and economic impacts | SDG 14—Life Below Water Conserve and sustainably manage oceans, seas, and marine resources to ensure their long-term ecological health and resilience | SDG 15—Life on Land Protect, restore, and promote the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems; manage forests responsibly; combat desertification; and halt biodiversity loss | |

| Integrating arts and cultural education can improve learning outcomes, foster creativity, and enrich educational content by incorporating local cultural traditions and practices | The cultural and creative industries can advance gender equality by empowering female artists and ensuring equitable access to cultural resources, opportunities, and representation | Cultural expressions and heritage can serve as instruments for peacebuilding and reconciliation, promoting participatory governance, inclusive dialog, and social cohesion | Social Pillar |

| SDG 4—Quality Education Ensure inclusive and equitable access to quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all individuals. | SDG 5—Gender Equality Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls by challenging discriminatory norms, eliminating harmful practices, and ensuring equal rights and opportunities. | SDG 16—Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions Promote peaceful, inclusive, and just societies by ensuring access to justice for all and fostering effective, accountable, and transparent institutions at every level. | |

| CIs generate substantial employment and drive economic growth by creating jobs across traditional craftsmanship, the arts, media, and creative tourism. | CIs promote responsible production and consumption by fostering green economy initiatives and sustainable practices. Through media and cultural expressions, they can advocate for the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). | Economic Pillar | |

| SDG 8—Decent Work and Economic Growth Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth by ensuring full and productive employment, decent working conditions, and equal opportunities for all. | SDG 12—Responsible Consumption and Production Encourage sustainable patterns of production and consumption by reducing carbon emissions, waste, and pollution; fostering a green economy; and integrating the SDGs into business and industry practices. | ||

| CIs can help reduce inequalities by supporting marginalized communities and artists, among others from the Global South. They also stimulate economic recovery in crisis-affected areas by strengthening creativity, culture, and tourism. | Culture plays a pivotal role in urban and regional development by contributing to the social and economic vitality of places through heritage conservation, the growth of creative industries, and the promotion of cultural tourism. | CIs can foster international collaboration and build global networks that advance sustainable development. Through their influential platforms, they raise awareness of the SDGs and engage diverse audiences in intercultural dialog | Mixed |

| SDG 10—Reduced Inequalities Reduce social and economic disparities within and among countries by promoting inclusive policies, equitable opportunities, and fair access to resources. | SDG 11—Sustainable Cities and Communities Build inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities by enhancing infrastructure, improving accessibility, expanding green spaces, and fostering social and economic opportunities. | SDG 17—Partnerships for the Goals Strengthen and revitalize global partnerships to support the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals through collaboration, knowledge exchange, and shared resources. | |

| Pillar | Related SDGs | Actions/Contributions | City |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | SDG 13 (Climate Action) | Carbon-neutral film production, climate-awareness themes | Łódź/Mumbai |

| SDG 14 (Life Below Water) | Nature-themed film festivals on ecosystems Environmental education through film | Łódź | |

| SDG 15 (Life on Land) | Łódź | ||

| Social | SDG 4 (Quality Education) | Film schools, festivals, workshops, internships, and museums | Łódź/Mumbai |

| SDG 5 (Gender Equality) | Gender equality in film themes and festivals, and women’s empowerment | Łódź/Mumbai | |

| SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) | Promoting tolerance, justice, inclusivity, and intercultural dialog through film themes and festivals | Łódź/Mumbai | |

| Economic | SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) | Jobs in the film sector, creative entrepreneurship, festival economy | Łódź/Mumbai |

| SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) | Green filming, sustainable production | Łódź/Mumbai | |

| Mixed | SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) | Inclusive, diversity-focused festivals and film productions promoting equal opportunities | Łódź/Mumbai |

| SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) | Urban regeneration through film heritage and tourism development | Łódź/Mumbai | |

| SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) | International film partnerships and exchanges | Łódź/Mumbai | |

| UNESCO Film City cooperation, co-productions | Łódź/Mumbai |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cudny, W.; Sattar, S.; Barwiński, M. Sustainable Urban Development Through Creative Film Industries: From Hollyłódź to Bollywood. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210256

Cudny W, Sattar S, Barwiński M. Sustainable Urban Development Through Creative Film Industries: From Hollyłódź to Bollywood. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210256

Chicago/Turabian StyleCudny, Waldemar, Sanjukta Sattar, and Marek Barwiński. 2025. "Sustainable Urban Development Through Creative Film Industries: From Hollyłódź to Bollywood" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210256

APA StyleCudny, W., Sattar, S., & Barwiński, M. (2025). Sustainable Urban Development Through Creative Film Industries: From Hollyłódź to Bollywood. Sustainability, 17(22), 10256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210256