Development of a Strategy to Reduce Food Waste in a Preschool Food Service

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Food Waste Quantification Methods and Strategies for Its Reduction

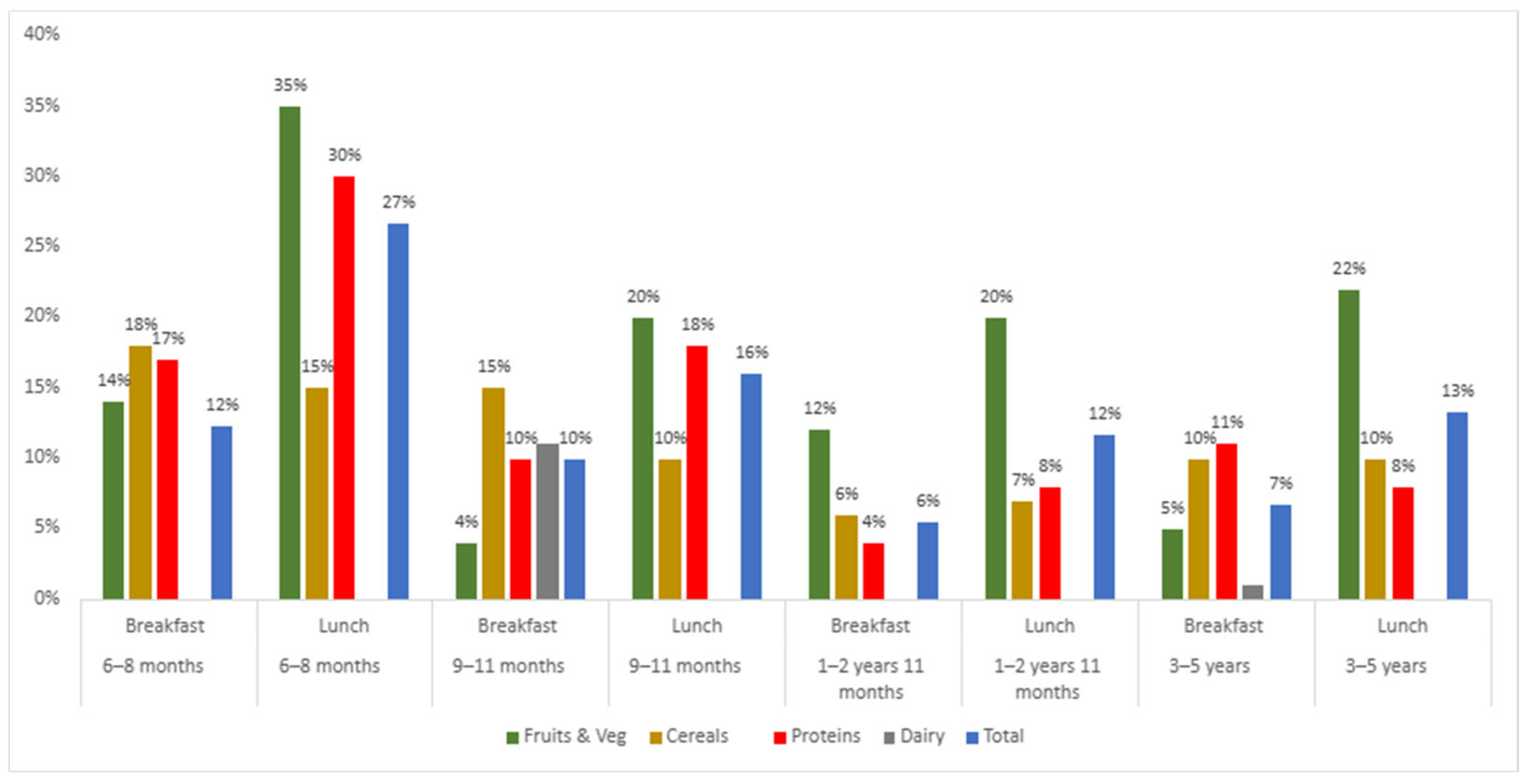

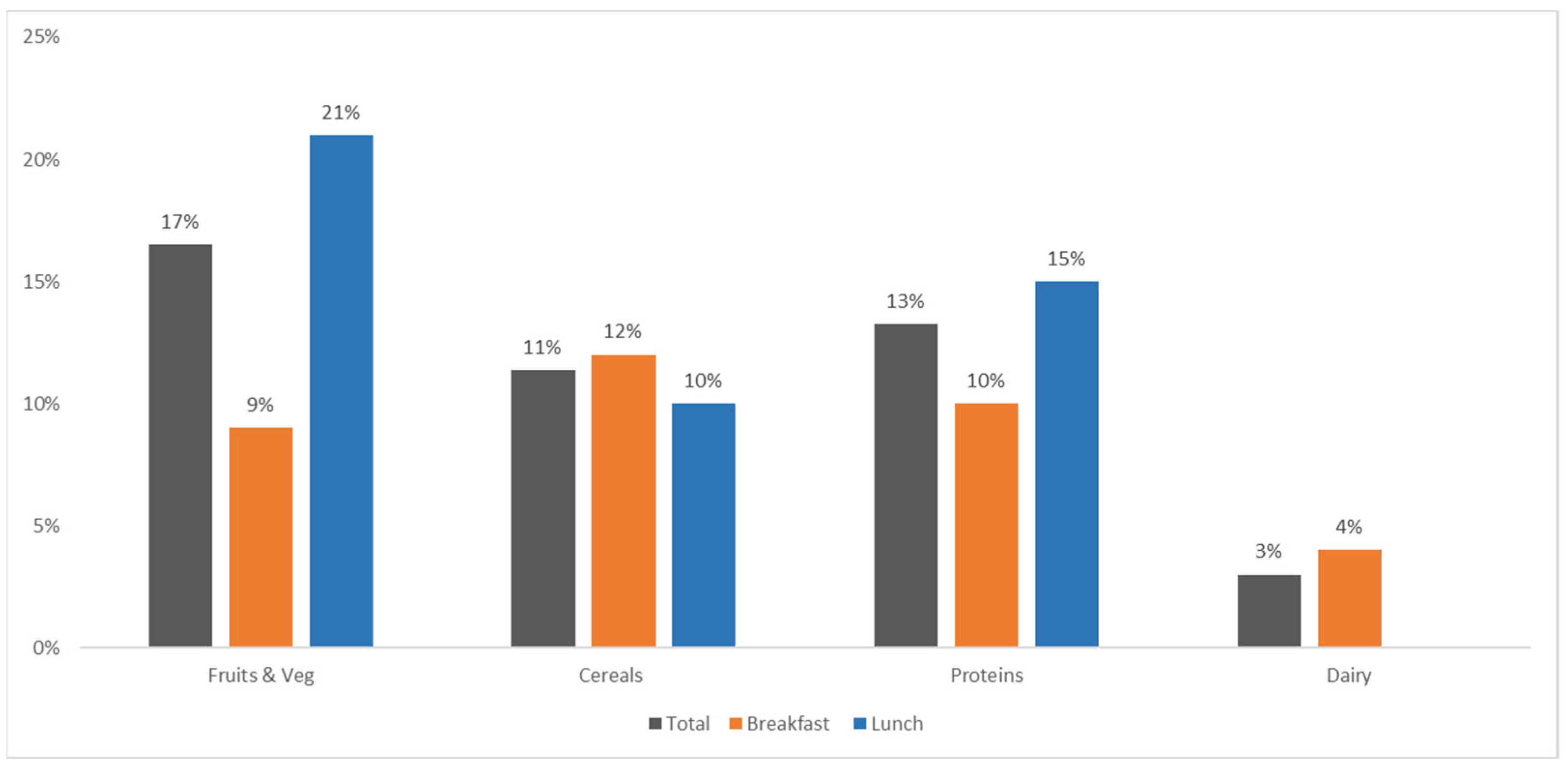

3.2. Diagnostic Activity in the Food Service

3.3. Perception of Food Consumption and Waste

3.3.1. Children’s Perception

3.3.2. Caregivers’ Interviews

3.3.3. Staff Interviews

4. Discussion

Strategy and Action Plan

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. FAO and UNEP Issue Call for Action on International Day of Awareness of Food Loss and Waste; UN Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food waste within food supply chains: Quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Tracking Progress on Food and Agriculture-Related SDG Indicators 2022; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Think Eat Save Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste. 2024. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/food-waste-index-report-2024 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Alzate Yepes, T.; Orozco Soto, D.M. Pérdida y desperdicio de alimentos. Problema que urge solución. Perspect. Nutr. Humana 2021, 23, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefadola, B.P.; Viljoen, A.; du Rand, G. Causes of Food Waste in a University Food Service Operation: An Investigation Based on the Systems Theory. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2023, 12, 1176–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.M.; Chih, C.; Teng, C.C. Food Waste Management: A Case of Taiwanese High School Food Catering Service. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundin, N.; Malefors, C.; Strotmann, C.; Orth, D.; Kaltenbrunner, K.; Obersteiner, G.; Scherhaufer, S.; Sjölund, A.; Persson Osowski, C.; Strid, I.; et al. Sustainability assessment of educational approaches as food waste prevention measures in school catering. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 481, 144196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, D.d.C.; Vidigal, M.D.; Farage, P.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Nakano, E.Y.; Botelho, R.B.A. Environmental, social and economic sustainability indicators applied to food services: A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, B.; Clowes, A. Why and How to Measure Food Loss and Waste: A Practical Guide; Commission for Environmental Cooperation: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arriz-Jorquiera, M.; Acuna, J.A.; Rodríguez-Carbó, M.; Zayas-Castro, J.L. Hospital food management: A multi-objective approach to reduce waste and costs. Waste Manag. 2024, 175, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, N.V.; Lermen, F.H.; Echeveste, M.E.S. A systematic literature review on food waste/loss prevention and minimization methods. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 286, 112268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathmanathan, V.; Rajadurai, J.; Alahakone, R. What a waste? An experience in a secondary school in Malaysia of a food waste management system (FWMS). Heliyon 2023, 9, e20327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzelli, M.; Iori, E.; Ihle, R.; Vittuari, M. Can changing the meal sequence in school canteens reduce vegetable food waste? A cluster randomized control trial. Food Policy 2025, 130, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, M.; Puppin Zandonadi, R.; Raposo, A.; Ginani, V.C. Food waste on foodservice: An overview through the perspective of sustainable dimensions. Foods 2021, 10, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzby, J.C.; Guthrie, J.F. Electronic Publications from the Food Assistance & Nutrition Research Program Plate Waste in School Nutrition Programs Final Report to Congress; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nohlen, D. El método comparativo. In Antologías Para el Estudio y la Enseñanza de la Ciencia Política. Volumen III: La Metodología de la Ciencia Política, 1st ed.; de la Barquera, S., Arroyo, H., Eds.; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2020; Volume 3, pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- ICBF; FAO. Guía Alimentarias Basadas en Alimentos Para la Población Colombiana Mayor de 2 Años, 2nd ed.; ICBF, Ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J. Management by Objectives Theory—Still Effective for Current Business Management? Adv. Econ. Manag. Political Sci. 2024, 69, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo Víquez, C.; Peña Vásquez, M. Cuantificación del desperdicio de alimentos en servicios de alimentación de la Universidad de Costa Rica. Perspect. Nutr. Humana 2021, 23, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamente, M.; Afonso, A.; De Los Ríos, I. Exploratory analysis of food waste at plate in school canteens in Spain. Granja 2018, 28, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Lindgren, S.; Persson Osowski, C. Mapping of food waste quantification methodologies in the food services of Swedish municipalities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 137, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Malefors, C.; Bergström, P.; Eriksson, E.; Osowski, C.P. Quantities and quantification methodologies of food waste in Swedish hospitals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, H.; Malefors, C.; Röös, E.; Eriksson, M. Identification and modelling of risk factors for food waste generation in school and pre-school catering units. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apelman, L.; Roos, E.; Olofsson, J.K.; Sandvik, P. Exploration of the relationship between olfaction, food Neophobia and fruit and vegetable acceptance in school-aged children. Food Qual. Prefer. 2025, 126, 105384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, R.; Maximino, P.; Nogueira, L.R.; de Paula, N.G.; Fussi, C.; Fisberg, M. Tactile and smell/taste sensitivity and accepted foods according to sensory properties: A cross-sectional study with children from a reference center in feeding difficulties. Int. J. Nutrol. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widajati, E.; Kristianto, Y. Involvement of Mother in Development of Fruit and Vegetables-Based Food Products for Kindergarten Students. 2024. Available online: https://proceeding.ressi.id/index.php/IConMC (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Nickel, V.R. Children Don’t Like Eating What They’re Supposed to Eat… A Study of Public Catering for Children in Hungary from a Historical Perspective. Acta Ethnogr. Hung. 2024, 68, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.Y.; Bech, A.C.; Sørensen, H.; Olsen, A.; Bredie, W.L.P. Food texture preferences in early childhood: Insights from 3–6 years old children and parents. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 113, 105063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawecka, P.; Kostecka, M. The role of the family environment and parental nutritional knowledge in the prevention of behavioral feeding disorders in toddlers and preschool children—A narrative review. J. Health Inequalities 2024, 10, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, T.V.E.; Rauh, E.M. Eating behaviors of children in the context of their family environment. Physiol. Behav. 2010, 100, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brand, A.J.P.; Hendriks-Hartensveld, A.E.M.; Havermans, R.C.; Nederkoorn, C. Child characteristic correlates of food rejection in preschool children: A narrative review. Appetite 2023, 190, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira-de-Almeida, C.A.; Weffort, V.R.S.; Ued Fda, V.; Ferraz, I.S.; Contini, A.A.; Martinez, E.Z.; Ciampo, L.A.D. What causes obesity in children and adolescents? J. Pediatr. 2024, 100, S48–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sick, J.; Højer, R.; Olsen, A. Children’s self-reported reasons for accepting and rejecting foods. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mualem, R. The Effect of Dietary Preferences on Academic Performance Among Kindergarten-Aged Children. Neurosci. Neurol. Surg. 2023, 13, 01–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, P.; De Rosso, S.; Moura, A.F.; Galler, M.; Philippe, K.; Pickard, A.; Rageliene, T.; Sick, J.; Van Nee, R.; Almli, V.L.; et al. Bringing down barriers to children’s healthy eating: A critical review of opportunities, within a complex food system. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2023, 37, 331–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Food Group | Age Group | Meal Time | % Critical Waste | Preparation | Food Group | Age Group | Meal Time | % High Waste | Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRUITS & VEGGIES | 6–8 months | Breakfast | 0% | Apple | FRUITS & VEGGIES | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 17% | Salad (spinach, papaya, mango, and cream) |

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Apple | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 18% | Apple | ||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Mango | 9–11 months | Lunch | 18% | Vegetables with mayonnaise | ||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 0% | Papaya | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 19% | Stew cucumber | ||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 0% | Pear | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 20% | Chard with egg | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 0% | Pumpkin with green peas | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 20% | Pear | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 0% | Salad (lettuce, tomato, avocado, cilantro) | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 21% | Beetroot salad | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 0% | Salad (spinach, papaya, mango, and cream) | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 21% | Vegetable (carrot, pumpkin) | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 0% | Vegetable (carrot, pumpkin) | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 22% | Pumpkin with green peas | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 1% | Watermelon | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 23% | Salad (cucumber, tomato, and cilantro) | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 1% | Papaya | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 23% | Pumpkin with green peas | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 1% | Salad (spinach and mango) | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 23% | Vegetable (carrot, pumpkin) | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 2% | Avocado | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 27% | Pumpkin with green peas | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 2% | Salad (lettuce, tomato and carrot) | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 28% | Chard with egg | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 2% | Watermelon | 9–11 months | Lunch | 29% | Beetroot salad | ||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 3% | Watermelon | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 33% | Pumpkin with green peas | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 4% | Mango | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 36% | Salad (grated carrot and tomato) | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 4% | Salad (spinach and mango) | 9–11 months | Lunch | 39% | Salad (spinach, papaya, mango, and cream) | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 4% | Salad (spinach, papaya, mango, and cream) | 9–11 months | Lunch | 41% | Salad (lettuce and tomato) | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 5% | Avocado | 9–11 months | Lunch | 43% | Salad (cucumber, tomato, and cilantro) | ||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 5% | Pear | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 50% | Salad (spinach, apple, and cream) | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 5% | Salad (lettuce, tomato, avocado, cilantro) | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 53% | Salad (spinach and mango) | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 5% | Vegetables with mayonnaise | 9–11 months | Lunch | 69% | Salad (grated carrot and tomato) | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 6% | Apple | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 88% | Salad (spinach, apple, and cream) | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 6% | Papaya | 6–8 months | Breakfast | 100% | Granadilla | ||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 6% | Papaya | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 9% | Mango | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 9% | Salad (cucumber, tomato, and cilantro) | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 10% | Avocado | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 10% | Pear | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 10% | Stew cucumber | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 12% | Salad (lettuce, tomato, avocado, cilantro) | ||||||

| 6–8 months | Lunch | 13% | Chard with egg | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 13% | Chard with egg | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 13% | Mango | ||||||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 13% | Mango | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 13% | Stew cucumber | ||||||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 14% | Watermelon | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 14% | Beetroot salad | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 14% | Granadilla | ||||||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 15% | papaya | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 15% | Salad (lettuce, tomato and carrot) | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 15% | Salad (grated carrot and tomato) | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 15% | Vegetables with mayonnaise | ||||||

| CEREAL | 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 0% | Corn arepa | CEREAL | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 11% | Steamed potato |

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Flavored cookie | 9–11 months | Lunch | 12% | Conchiglie | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 0% | Flavored cookie | 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 13% | Corn bread | ||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 0% | Flavored cookie | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 13% | Plantain with guava paste | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Soda crackers | 9–11 months | Lunch | 13% | Cassava (yuca) | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 0% | Soda crackers | 9–11 months | Lunch | 14% | Rice with carrot | ||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 0% | Wholemeal bread roll | 9–11 months | Lunch | 14% | Arracacha sticks | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Sliced bread | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 14% | Steamed creole potato | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 0% | Sliced bread | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 15% | Arracacha sticks | ||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Sliced bread | 9–11 months | Breakfast | 15% | Puff pastry bread | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 0% | Steamed potato | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 15% | Steamed potato | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 0% | Potato chips | 6–8 months | Lunch | 15% | Steamed creole potato | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 0% | Roasted ripe plantain | 9–11 months | Breakfast | 16% | Flavored cookie | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 0% | Roasted ripe plantain | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 16% | Ripe plantain boiled with cinnamon | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 0% | Roasted ripe plantain | 9–11 months | Breakfast | 17% | Soft bread | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 0% | Fried ripe plantain slices | 9–11 months | Lunch | 17% | Potato chips | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Toast | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 18% | Wholemeal bread roll | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 0% | Toast | 9–11 months | Lunch | 19% | Plantain with guava paste | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 1% | Soft bread | 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 20% | Wholemeal bread roll | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 1% | Rice with cilantro | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 21% | Pasta shells | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 1% | Rice with cilantro | 6–8 months | Lunch | 24% | Pasta shells | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 2% | Fried ripe plantain slices | 9–11 months | Breakfast | 25% | Wholemeal bread roll | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 2% | White rice | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 25% | Pasta shells | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 2% | Rice with noodles | 6–8 months | Breakfast | 26% | Soft bread | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 2% | Rice with noodles | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 28% | Arracacha sticks | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 2% | Rice with carrot | 9–11 months | Breakfast | 28% | Corn bread | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 3% | Corn arepa | 6–8 months | Lunch | 33% | Rice with carrot | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 3% | Ripe plantain boiled with cinnamon | 9–11 months | Lunch | 33% | Ripe plantain boiled with cinnamon | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 4% | White rice | 6–8 months | Lunch | 34% | Spaghetti | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 4% | Potato chips | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 40% | Cassava (yuca) | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 4% | Crispy potato | 9–11 months | Lunch | 43% | Crispy potato | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 5% | White rice | 6–8 months | Breakfast | 48% | Puff pastry bread | ||

| 6–8 months | Lunch | 5% | Rice with noodles | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 49% | Cassava (yuca) | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 5% | Rice with carrot | ||||||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 5% | Soda crackers | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 5% | Soda crackers | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 5% | Corn bread | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 5% | Steamed creole potato | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 5% | Crispy potato | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 5% | Plantain with guava paste | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 5% | Spaghetti | ||||||

| 6–8 months | Lunch | 6% | White rice | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 6% | Rice with cilantro | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 6% | Puff pastry bread | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 7% | Puff pastry bread | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 7% | Steamed creole potato | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 7% | Spaghetti | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 8% | Fried ripe plantain slices | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 8% | Soft bread | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 9% | Corn arepa | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 9% | Rice with noodles | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 10% | Spaghetti | ||||||

| PROTEINS | 6–8 months | Lunch | 0% | Grilled pork | PROTEINS | 6–8 months | Lunch | 16% | Ground pork |

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 0% | Beef goulash | 9–11 months | Lunch | 16% | Tuna with vegetables | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 0% | Stewed ground beef | 9–11 months | Lunch | 18% | Meatball in sauce | ||

| 6–8 months | Lunch | 0% | Stewed ground beef | 9–11 months | Lunch | 18% | Beans | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 0% | Chicken hearts | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 18% | Tuna with vegetables | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 0% | Chicken hearts | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 19% | Grilled pork | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 0% | Beans | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 19% | Tuna with vegetables | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 0% | Chickpeas | 9–11 months | Lunch | 22% | Grilled chicken breast | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 0% | Egg with corn | 6–8 months | Lunch | 23% | Grilled chicken breast | ||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 0% | Blended egg | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 24% | Grilled beef | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Scrambled eggs with tomatoes and onions | 9–11 months | Breakfast | 25% | Boiled egg | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 0% | Scrambled eggs with tomatoes and onions | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 25% | Beef liver | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Scrambled egg | 9–11 months | Lunch | 26% | Chickpeas | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Cheese omelet | 9–11 months | Lunch | 27% | Roasted pork | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 0% | Cheese omelet | 9–11 months | Lunch | 27% | Lentils | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 0% | Grilled chicken breast | 6–8 months | Lunch | 28% | Beef | ||

| 6–8 months | Lunch | 0% | Stewed chicken breast | 9–11 months | Lunch | 29% | Stewed pork | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 1% | Grilled beef | 9–11 months | Lunch | 29% | Chicken breast | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 1% | Scrambled egg | 9–11 months | Lunch | 34% | Grilled beef | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 1% | Chicken breast | 9–11 months | Lunch | 36% | Beef liver | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 2% | Beef goulash | 6–8 months | Lunch | 37% | Chicken hearts | ||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 3% | Beef goulash | 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 37% | Beef liver | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 3% | Ground beef | 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 39% | Boiled egg | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 3% | Roasted pork | 6–8 months | Lunch | 54% | Ground beef | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 3% | Lentils | 6–8 months | Breakfast | 55% | Boiled egg | ||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 3% | Grilled chicken breast | 6–8 months | Lunch | 88% | Bolognese ground beef | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 3% | Stewed chicken breast | 6–8 months | Lunch | 100% | Roasted pork | ||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 4% | Stewed pork | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 4% | Stewed ground beef | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 5% | Meatball in sauce | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 5% | Meatball in sauce | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 5% | Hamburger patty | ||||||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 5% | Scrambled egg | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 5% | Scrambled egg | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 6% | Ground beef | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 6% | Ground beef | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 7% | Hamburger patty | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 7% | Pork in pineapple sauce | ||||||

| 6–8 months | Lunch | 7% | Pork in pineapple sauce | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 7% | Pork in pineapple sauce | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 7% | Chicken hearts | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 7% | Scrambled eggs with tomatoes and onions | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 8% | Grilled pork | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 8% | Roasted pork | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 8% | Beans | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 10% | Grilled pork | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 10% | Stewed ground beef | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Lunch | 10% | Hamburger patty | ||||||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 10% | Scrambled eggs with tomatoes and onions | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 10% | Cheese omelet | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 10% | Lentils | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 11% | Egg with corn | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 12% | Beef | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 13% | Chickpeas | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Lunch | 14% | Stewed pork | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 14% | Beef | ||||||

| 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 15% | Boiled egg | ||||||

| 3–5 yrs | Lunch | 15% | Pork in pineapple sauce | ||||||

| 6–8 months | Breakfast | 15% | Egg with corn | ||||||

| 9–11 months | Breakfast | 15% | Egg with corn | ||||||

| DAIRY PRODUCTS | 1–2 yrs 11 months | Breakfast | 0% | Cheese | DAIRY PRODUCTS | 9–11 months | Breakfast | 11% | Cheese |

| 3–5 yrs | Breakfast | 1% | Cheese | ||||||

| Stage | Activity | Objective | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data collection (evaluate menu) | 1.1 Review and adjust menus based on waste data. Modify food preparations and portion sizes according to waste patterns (e.g., replace boiled eggs with scrambled, serve ripe fruits, reduce dry foods). | Improve acceptance of critical items (proteins, salads, cereals) by adapting texture, portion size, and presentation to each age group. | Direct weighing matrix, portion size charts, observation logs, staff meetings. |

| 2. Adjust menu | 1.2 Implement pilot menu trials. Introduce small-scale menu tests to assess the impact of changes in preparation and presentation | Evaluate improvements in acceptance and texture adaptation | Kitchen staff collaboration, child-friendly utensils, feedback forms. |

| 3. Education and awareness program | Conduct food education workshops for families and staff. Quarterly sessions focusing on food diversity, persistence in introducing new foods, and techniques to make meals more appealing. | Align home and institutional practices to reduce food neophobia and reinforce consistent exposure. | Educational materials, facilitators, workshop spaces. |

| Involve children in food preparation. Monthly pedagogical activities to encourage tasting and sensory exploration. | Promote familiarity with foods and positive emotional engagement during meals. | Safe kitchen tools, ingredients, supervision. | |

| 4. Improvement of the eating environment | Implement structured and supportive mealtime routines. Include pre-meal rituals (handwashing, table setting, food introduction). | Reduce anxiety and distraction; promote autonomy and positive mealtime behavior. | Visual routine materials, staff training. |

| Enhance presentation and dining area aesthetics. Use colorful plating and child-appropriate serving materials. | Increase sensory appeal and stimulate appetite. | Institutional kitchen equipment, tableware for children. | |

| 5. Continuous monitoring and evaluation | Weekly weighing and record keeping. Continue direct weighing and visual documentation of leftovers. | Quantify progress and identify emerging waste trends. | Scales, logbooks, trained staff. |

| Quarterly review of implementation impact. Evaluate behavioral changes and menu acceptance. | Ensure continuous improvement and evidence-based adjustments. | Evaluation tools (surveys, checklists), team meetings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cáceres Sandoval, M.L.; Cote Daza, S.P. Development of a Strategy to Reduce Food Waste in a Preschool Food Service. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10226. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210226

Cáceres Sandoval ML, Cote Daza SP. Development of a Strategy to Reduce Food Waste in a Preschool Food Service. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10226. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210226

Chicago/Turabian StyleCáceres Sandoval, Maria Lorena, and Sandra Patricia Cote Daza. 2025. "Development of a Strategy to Reduce Food Waste in a Preschool Food Service" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10226. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210226

APA StyleCáceres Sandoval, M. L., & Cote Daza, S. P. (2025). Development of a Strategy to Reduce Food Waste in a Preschool Food Service. Sustainability, 17(22), 10226. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210226