Zinc Kiln Slag Recycling Based on Hydrochloric Acid Oxidative Leaching and Subsequent Metal Recovery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

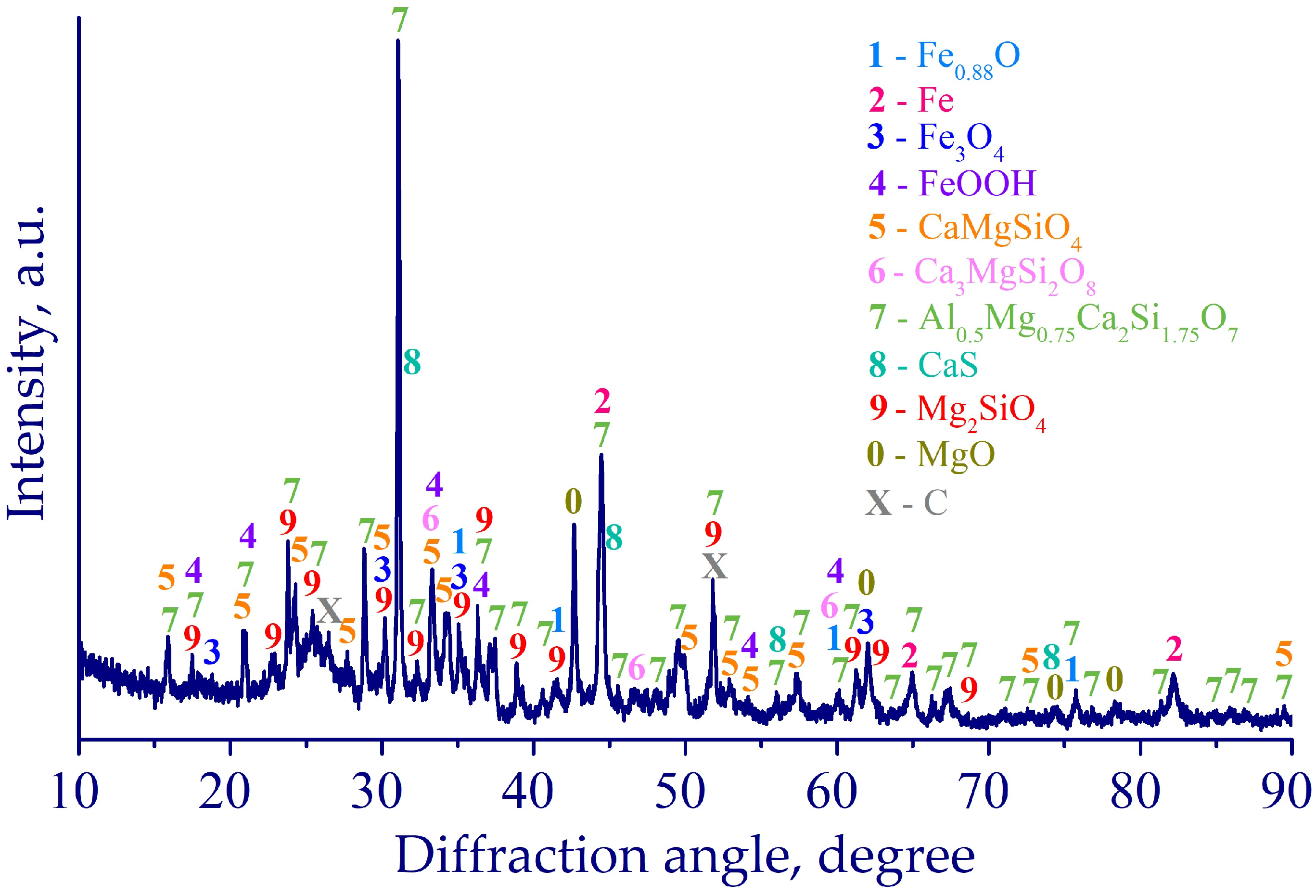

2.1. Raw Materials

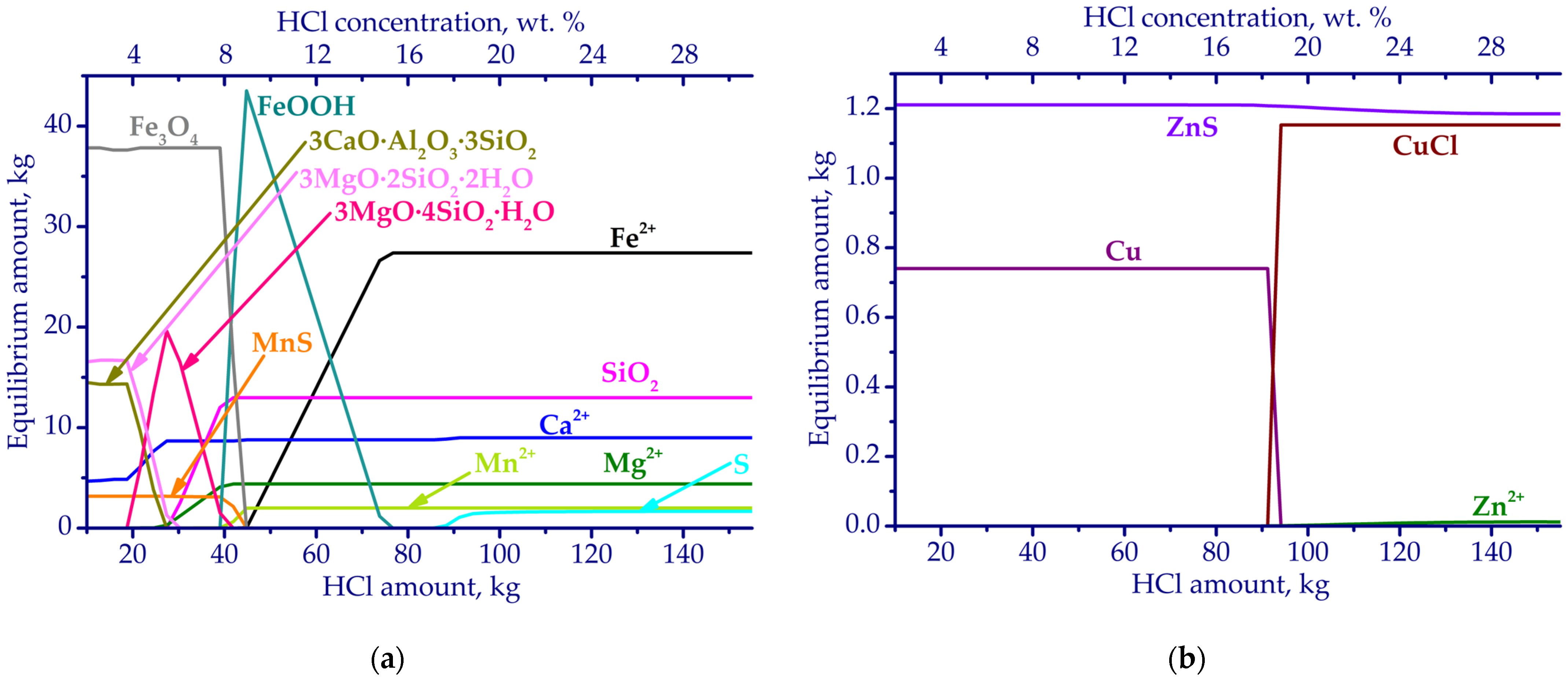

2.2. Thermodynamic Simulation Method

2.3. Experiments

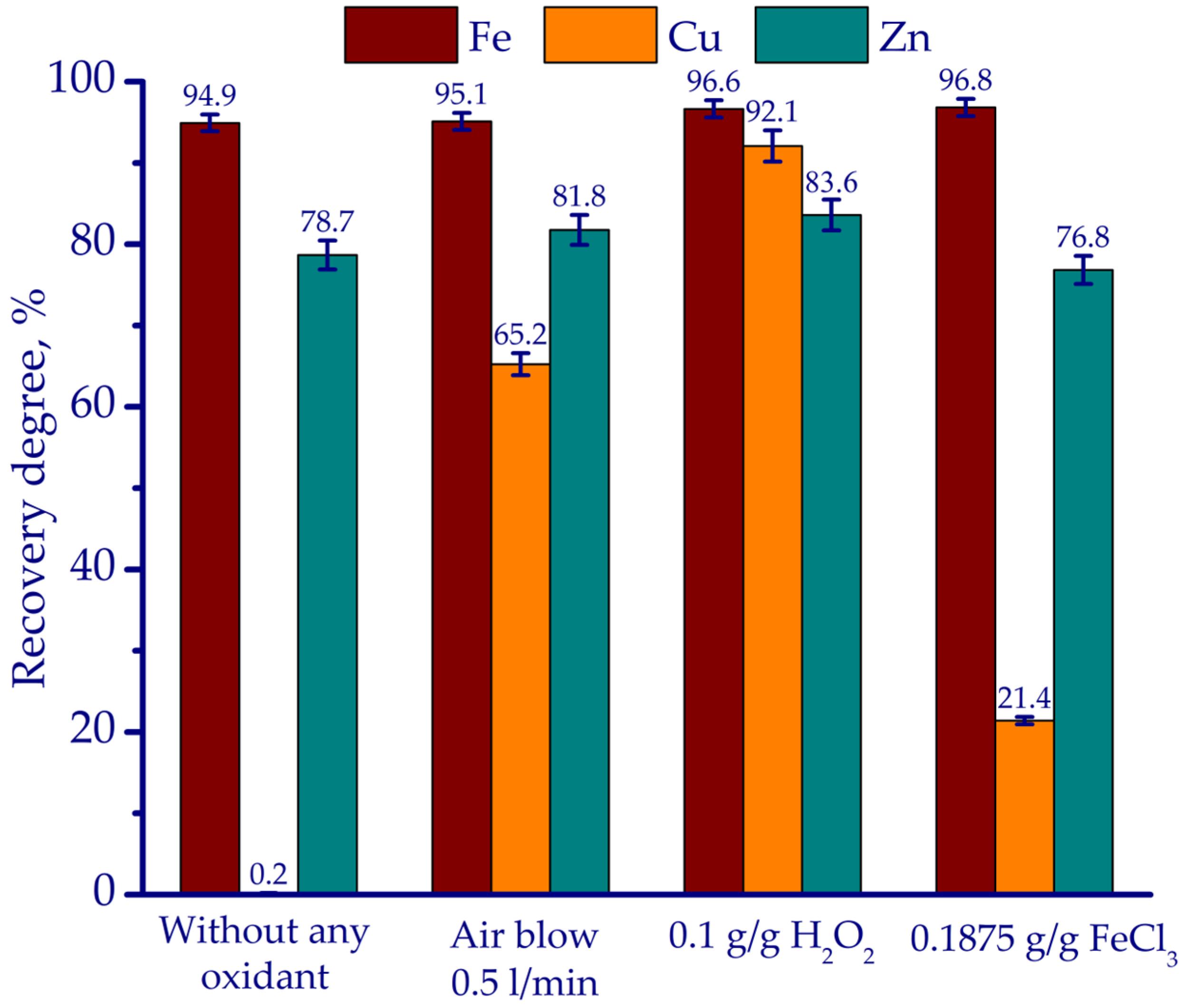

2.3.1. Hydrochloric Acid Leaching of the ZKS Sample

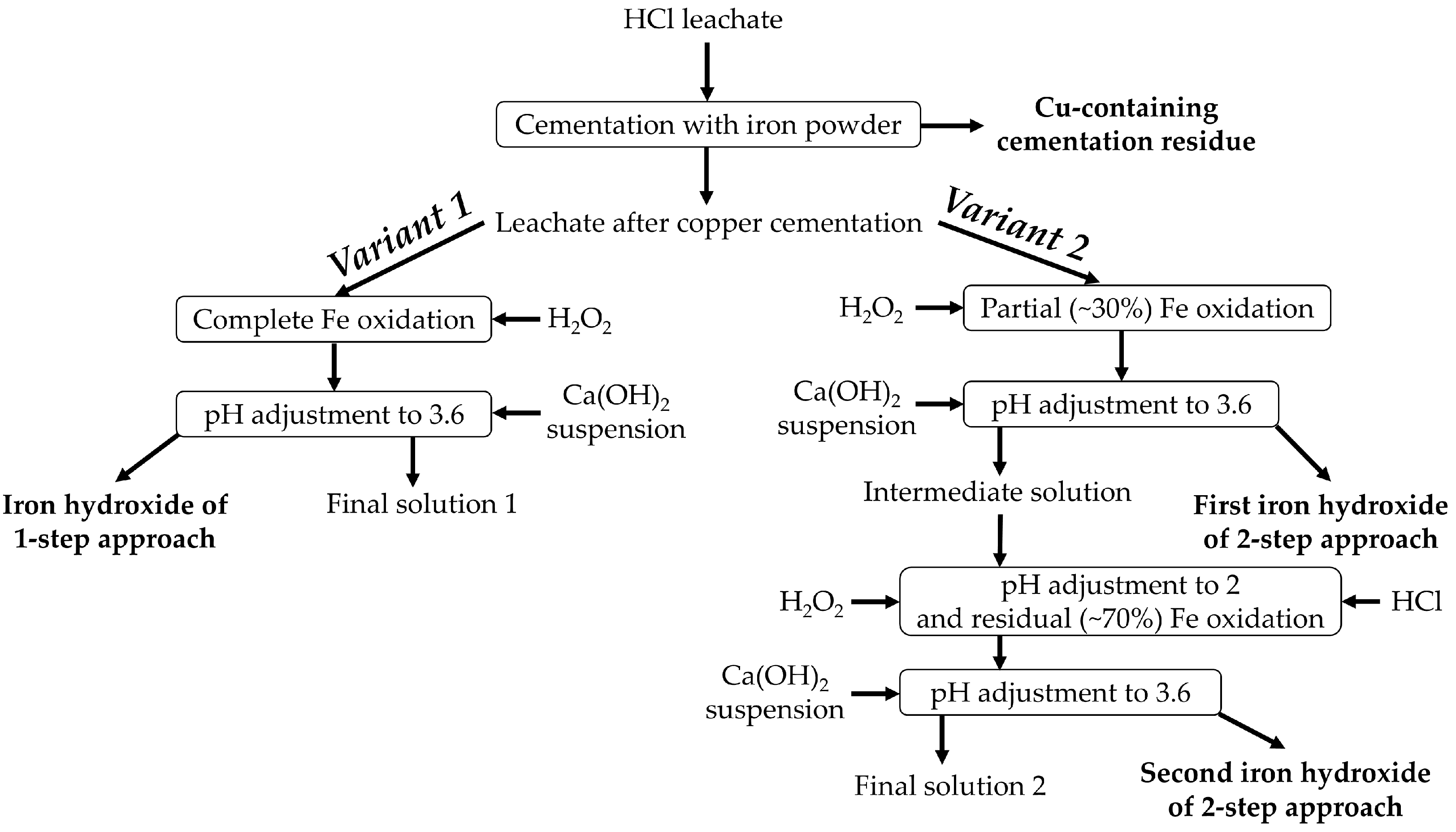

2.3.2. Precipitation of Copper and Iron

2.4. Analysis Methods

3. Results

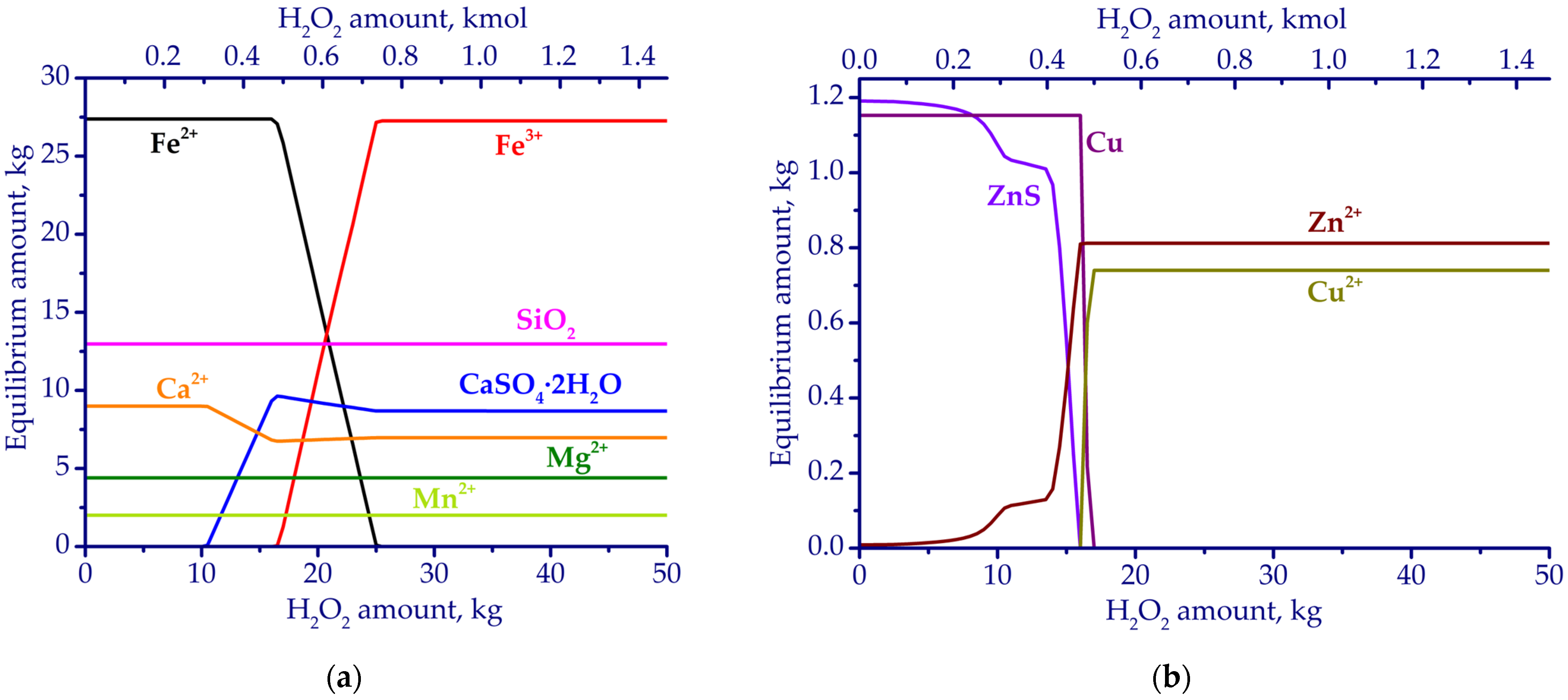

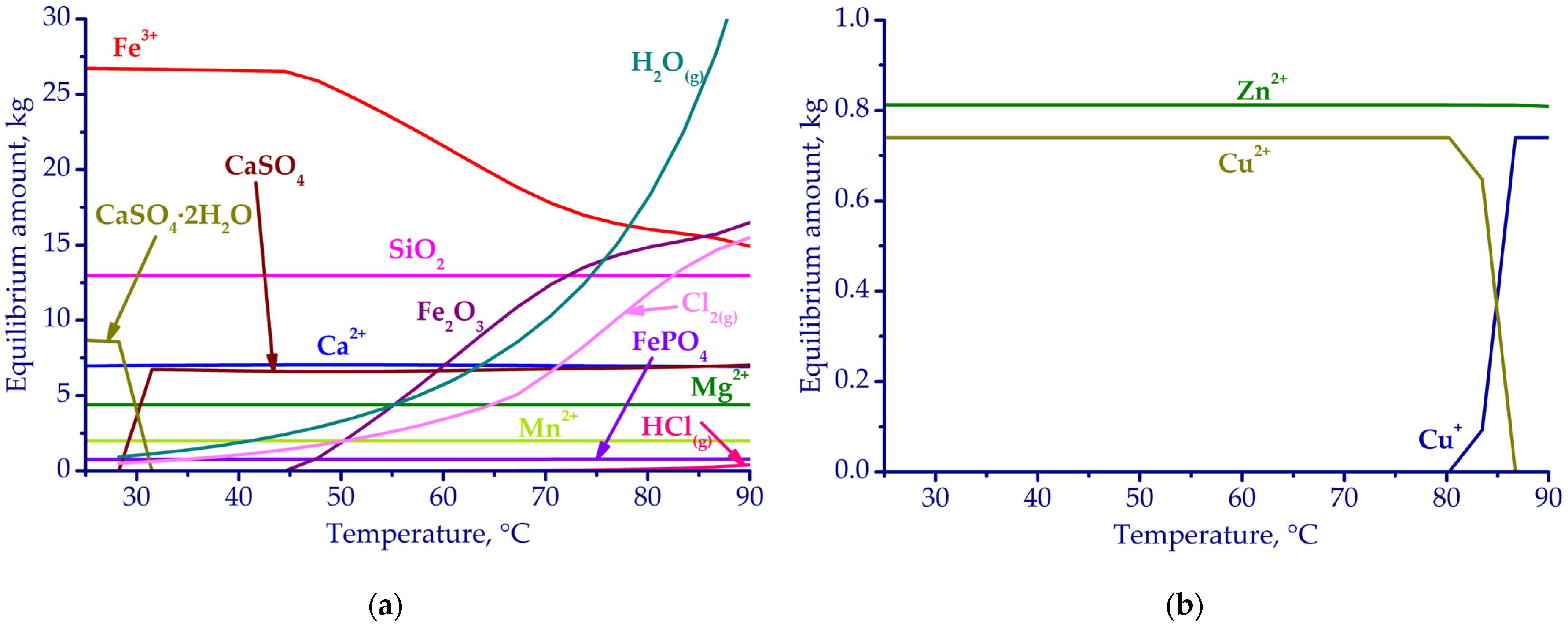

3.1. Thermodynamic Simulation Results

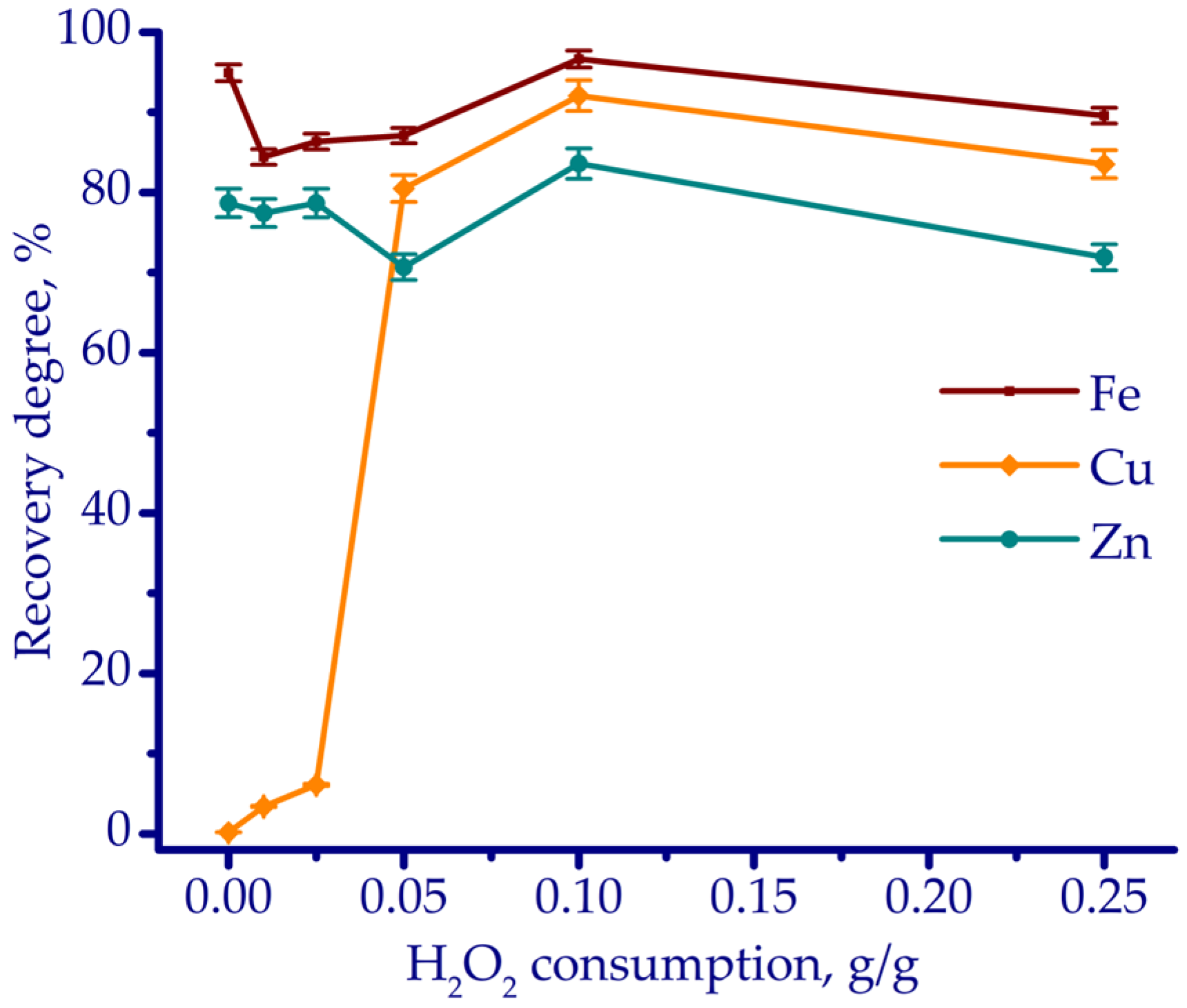

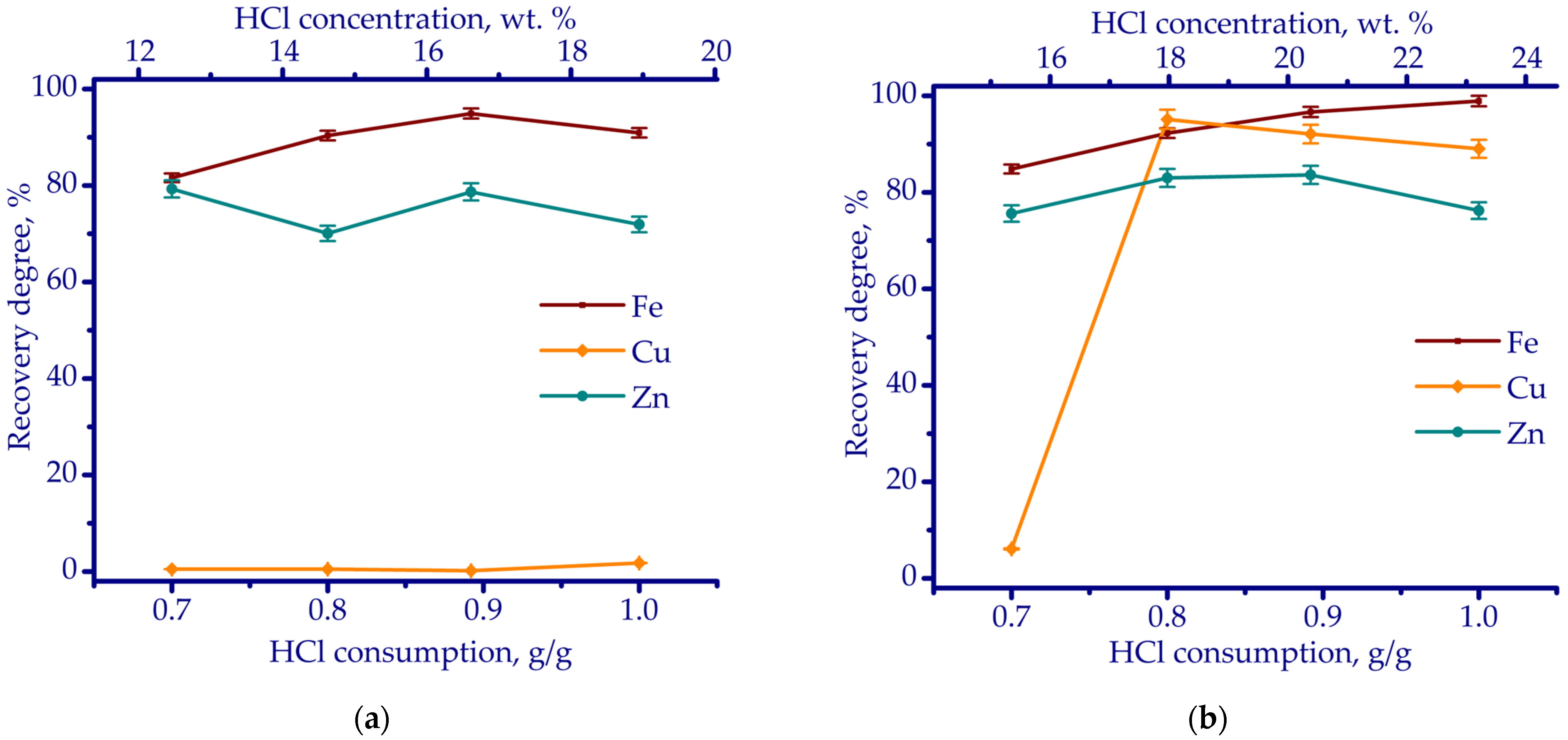

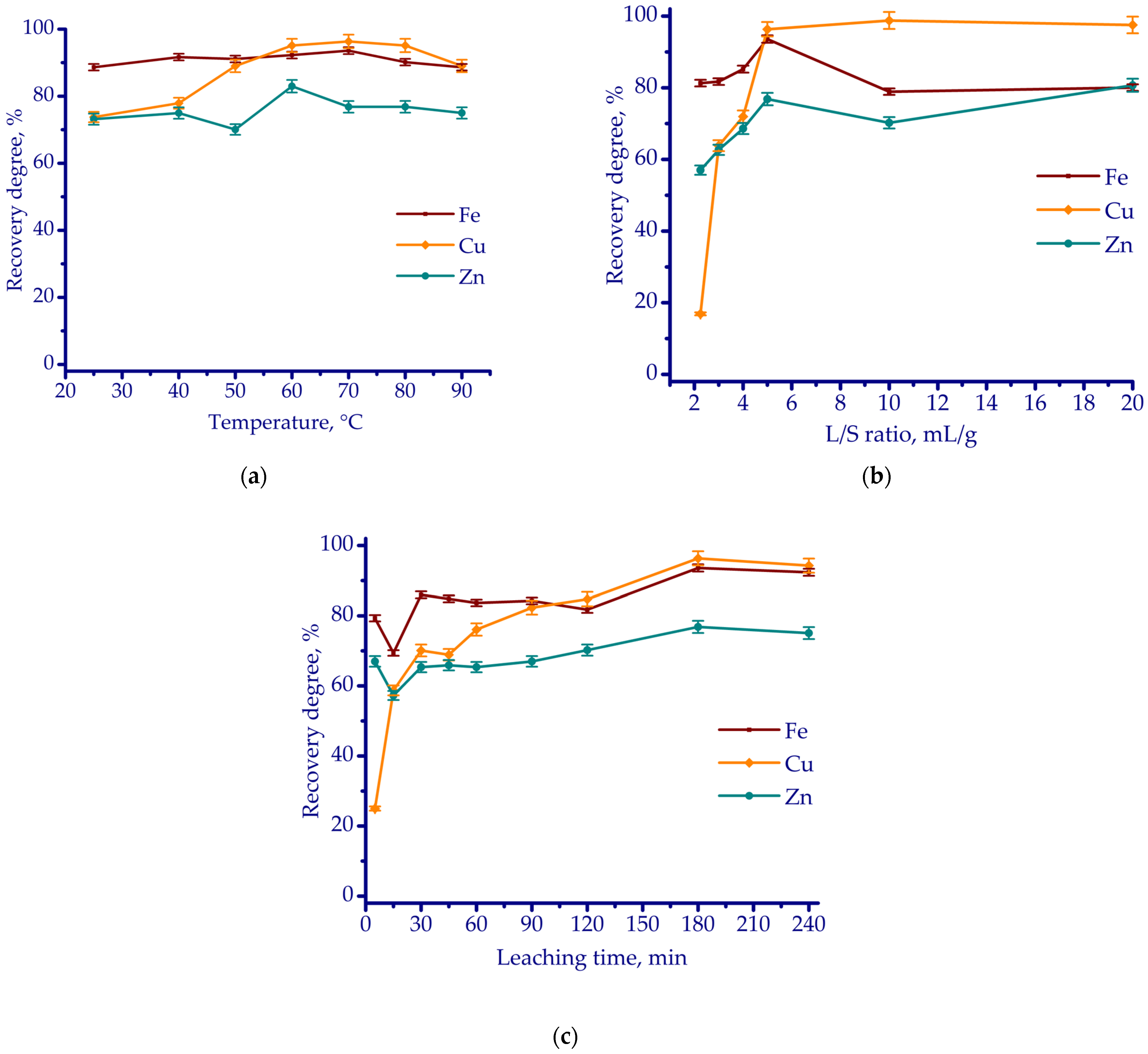

3.2. Leaching Experiments

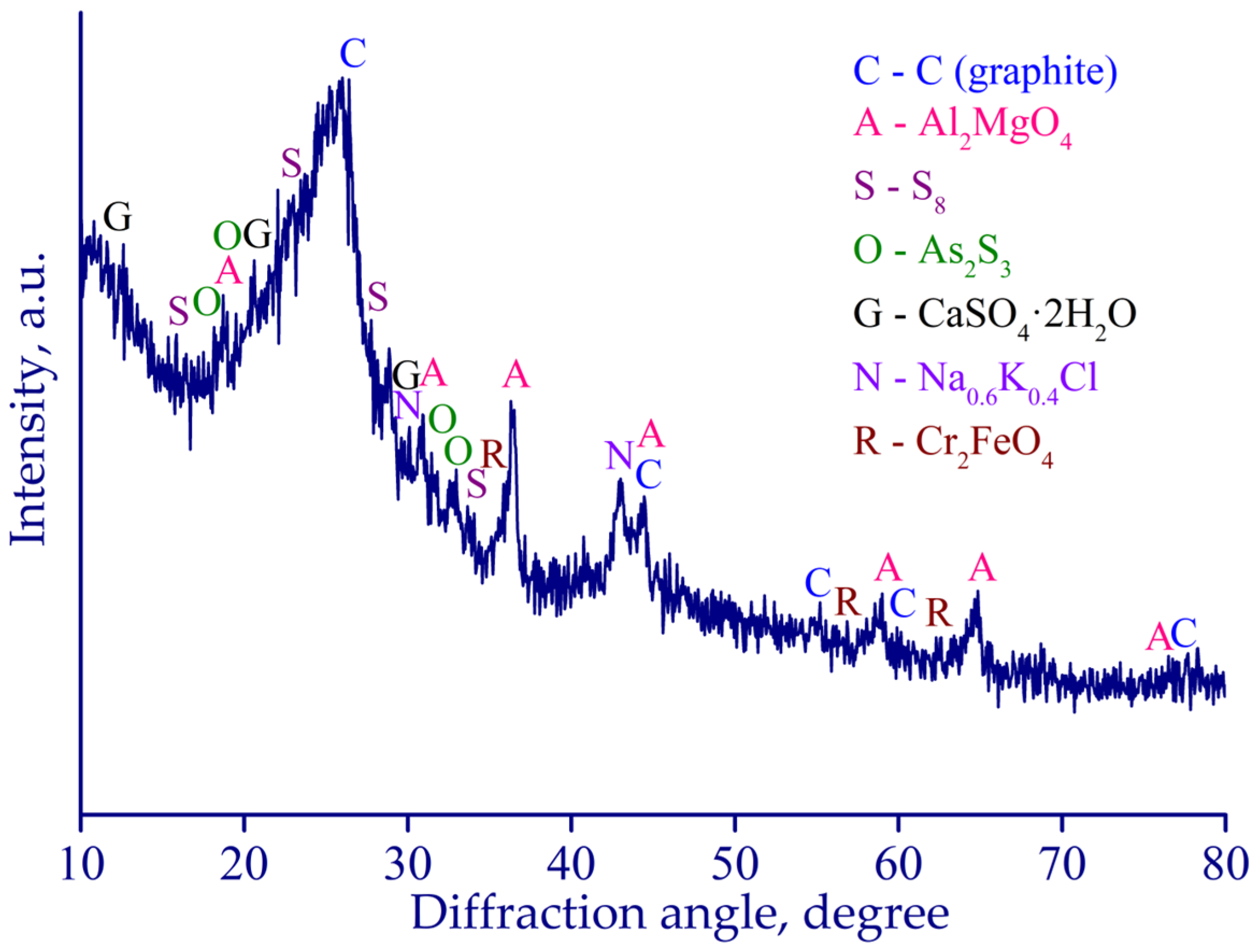

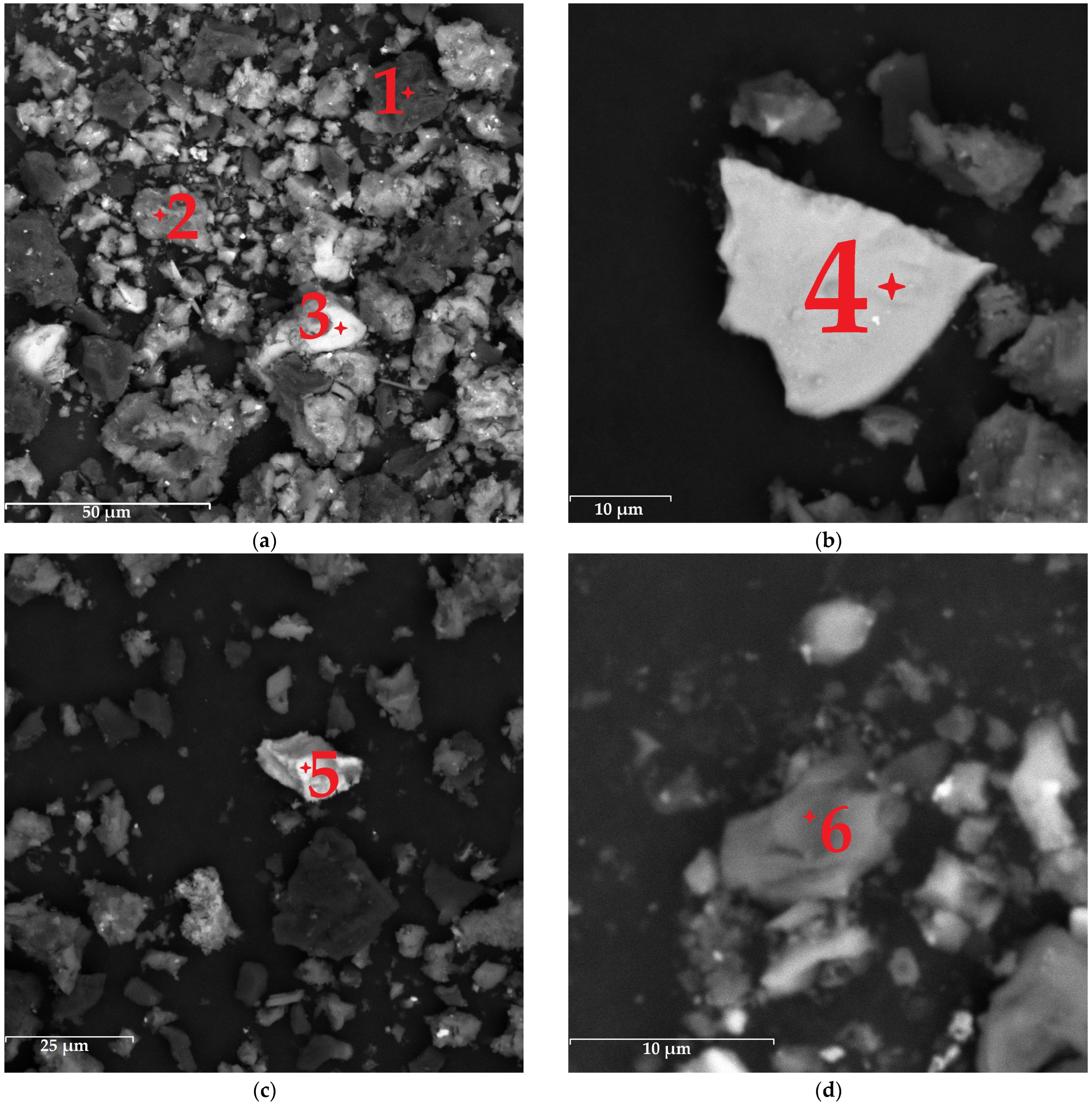

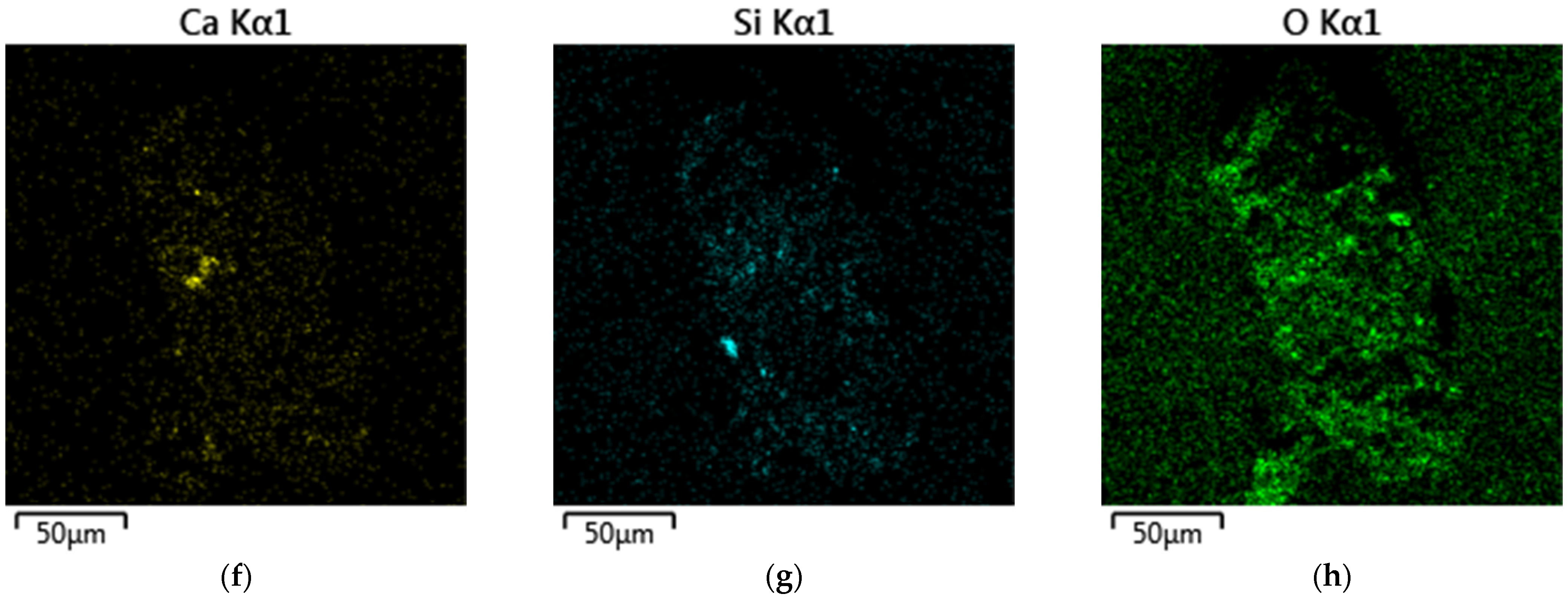

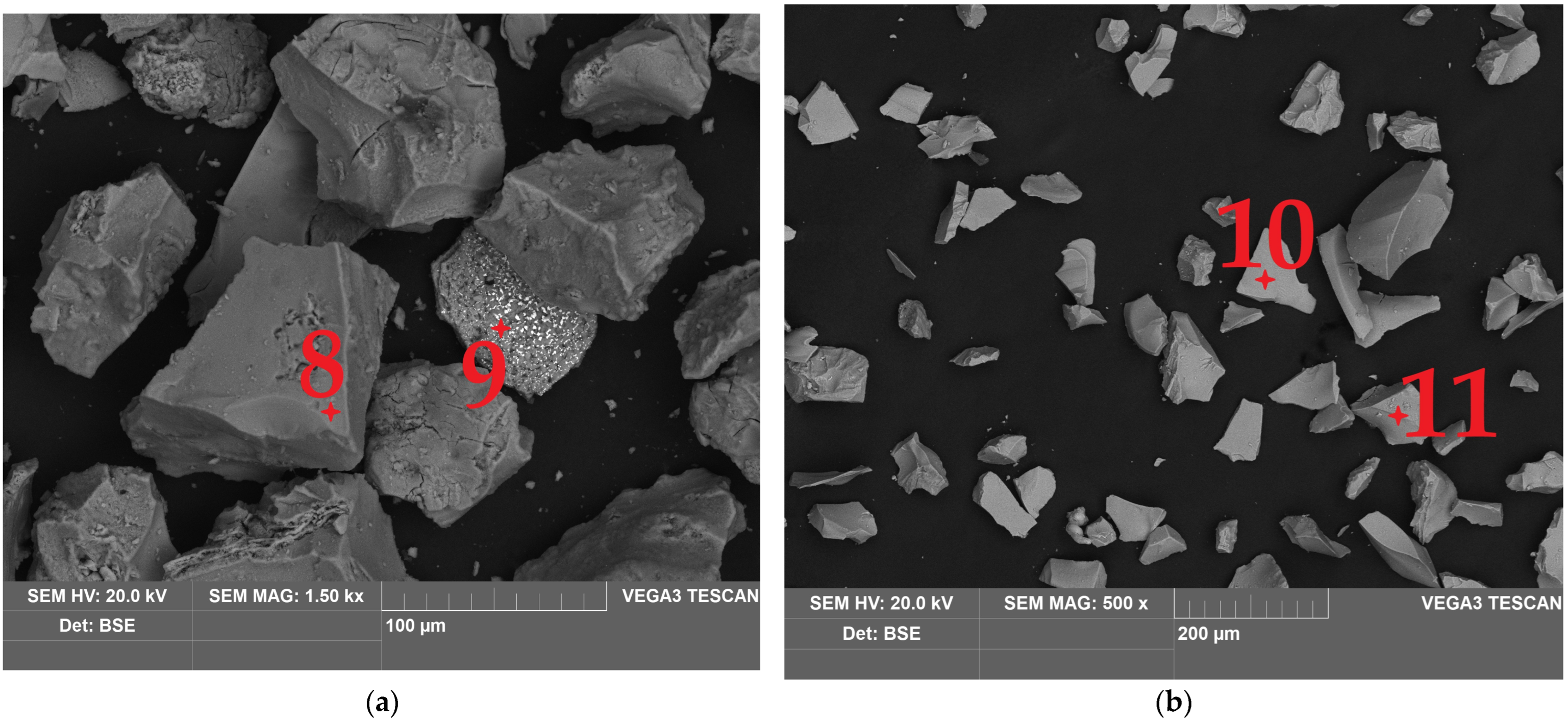

3.3. Characterization of Leaching Products

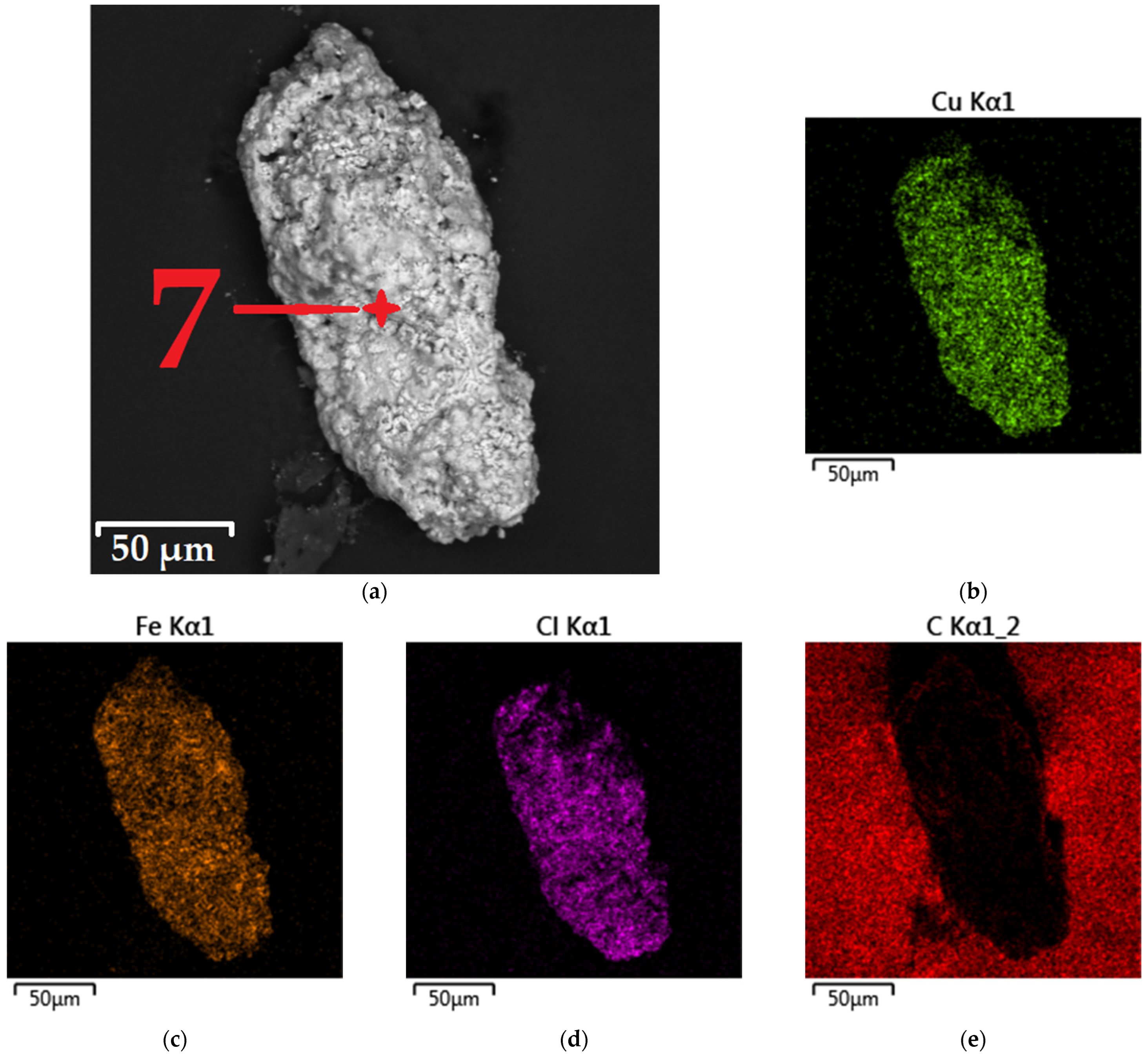

3.4. Copper Precipitation

3.5. Iron Precipitation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- According to thermodynamic simulation followed by laboratory-scale experiments, HCl leaching proved to be the most effective in terms of reagent consumptions of 0.8 g HCl and 0.1 g H2O2 per gram of ZKS, with an L/S ratio of 5 mL/g, maintained at 70 °C for 180 min. Under these conditions, the recovery rates of Cu, Fe, and Zn reached 96.3%, 93.6%, and 76.8%, respectively.

- The remaining HCl leach residue was identified as predominantly graphite-based with 43.1 wt. % C, containing substantial fractions of non-crystalline silica, spinel phases, orthorhombic sulfur, and sodium-potassium halides. The remaining Cu, Fe, and Zn compounds in the residue were identified as various sulfides. After further treatment, the residue had the potential to be utilized in the Waelz process as a partial substitute for reducing agents.

- Cementation using iron powder enabled the recovery of 98.9% Cu and 91.2% As from the hydrochloric acid leachate.

- The two-step approach of iron precipitation achieved a recovery >90% of Fe, with about 70% concentrated in a low-impurity ferric hydroxide fraction with 52.2 wt. % Fe suitable for recycling.

- Thus, the integration of leaching and metal precipitation provides a scientifically validated and practically feasible approach based on a novel hydrochloric acid oxidative leaching route for the sustainable recycling of ZKS.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ZKS | Zinc kiln slag |

| L/S ratio | Liquid-to-solid ratio |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDS | Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| ICP-OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy |

| COD | Crystallography Open Database |

| CC | Chemical composition |

References

- Carrasco, C.; Keeney, L.; Walters, S.G. Development of a Novel Methodology to Characterise Preferential Grade by Size Deportment and Its Operational Significance. Miner. Eng. 2016, 91, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejtemaei, M.; Gharabaghi, M.; Irannajad, M. A Review of Zinc Oxide Mineral Beneficiation Using Flotation Method. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2014, 206, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araújo Neto, A.P.; Sales, F.A.; Ramos, W.B.; Brito, R.P. Thermo-Environmental Evaluation of a Modified Waelz Process for Hazardous Waste Treatment. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 149, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhathini, T.P.; Bwapwa, J.K.; Mtsweni, S. Various Options for Mining and Metallurgical Waste in the Circular Economy: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, S.P. Geopolymerization of Solid Waste of Non-Ferrous Metallurgy—A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolmachikhina, E.B.; Lugovitskaya, T.N.; Golibzoda, Z.M.; Lobanov, V.G. Alkaline Leaching of Spent Zinc-Containing Batteries Sintered in the Presence of Sodium Peroxide. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 2632–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wu, Y.; Tang, A.; Pan, D.; Li, B. Recovery of Scattered and Precious Metals from Copper Anode Slime by Hydrometallurgy: A Review. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 197, 105460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorai, B.; Jana, R.K. Premchand Characteristics and Utilisation of Copper Slag—A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2003, 39, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatak, N.M.; Parsons, M.B.; Seal, R.R. Characteristics and Environmental Aspects of Slag: A Review. Appl. Geochem. 2015, 57, 236–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, A.; Gogov, N.; Grigorova, D.; Hodjaoglu, G. Investigation of the Composition and Structure of Waelz Slag. SEPRM 2025, 6, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, D. Classification of Zinc Recovery Quality from EAF Dust Using Machine Learning: A Waelz Process Study. Eng. Perspect. 2024, 4, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecki, S.; Gargul, K.; Warzecha, M.; Stradomski, G.; Hutny, A.; Madej, M.; Dobrzyński, M.; Prajsnar, R.; Krawiec, G. High-Performance Method of Recovery of Metals from EAF Dust—Processing without Solid Waste. Materials 2021, 14, 6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gao, W.; Wen, J.; Gan, Y.; Wu, B.; Shang, H. Research progress in the recovery of valuable metals from zinc leaching residue and its total material utilization. Chin. J. Eng. 2020, 42, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, K.; Fu, T.; Gao, J.; Hussain, S.; AlGarni, T.S. Pyrometallurgical Recovery of Zinc and Valuable Metals from Electric Arc Furnace Dust—A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrekowitsch, J.; Steinlechner, S.; Unger, A.; Rösler, G.; Pichler, C.; Rumpold, R. Zinc and Residue Recycling. In Handbook of Recycling; Worrell, E., Reuter, M.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Chapter 9; pp. 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov, A.; Fediuk, R.; Amran, M.; Klyuev, S.; Klyuev, A.; Volokitina, I.; Naukenova, A.; Shapalov, S.; Utelbayeva, A.; Kolesnikova, O.; et al. Modeling of Non-Ferrous Metallurgy Waste Disposal with the Production of Iron Silicides and Zinc Distillation. Materials 2022, 15, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucheva, B.; Iliev, P.; Draganova, K.; Stefanova, V. Recovery of Copper and Zinc from Waelz Clinker Wasted from Zinc Production. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2014, 49, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gapparov, J.; Syrlybekkyzy, S.; Filin, A.E.; Kolesnikov, A.S.; Zhatkanbaev, Y. Overview of Techniques and Methods of Processing the Waste of Stale Clinkers of Zinc Production. MIAB 2024, 4, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov, A.S.; Serikbaev, B.E.; Zolkin, A.L.; Kenzhibaeva, G.S.; Isaev, G.I.; Botabaev, N.E.; Shapalov, S.K.; Kolesnikova, O.G.; Iztleuov, G.M.; Suigenbayeva, A.Z.; et al. Processing of Non-Ferrous Metallurgy Waste Slag for Its Complex Recovery as a Secondary Mineral Raw Material. Refract. Ind. Ceram. 2021, 62, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Niu, H.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Wei, C.; Fan, X.-X.; Huang, M. Present Situation and Prospect about Comprehensive Utilization of Zinc Kiln Slags. Multipurp. Util. Miner. Resour. 2008, 6, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobanov, V.G.; Kolmachikhina, O.B.; Polygalov, S.E.; Khabibulina, R.E.; Sokolov, L.V. Features of the Presence of Precious Metals in the Zinc Production Clinker. Russ. J. Non-Ferr. Met. 2022, 63, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh Vayghan, A.; Horckmans, L.; Snellings, R.; Peys, A.; Teck, P.; Maier, J.; Friedrich, B.; Klejnowska, K. Use of Treated Non-Ferrous Metallurgical Slags as Supplementary Cementitious Materials in Cementitious Mixtures. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanapur, N.V.; Tripathi, B.; Chandra, T. Incorporating Waelz Slag to Strengthen the Properties of Fine Recycled Aggregate Concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 104, 112235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, M.; Andrés, A.; Cheeseman, C.R. Acid Gas Emissions from Structural Clay Products Containing Secondary Resources: Foundry Sand Dust and Waelz Slag. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 115, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darama, S.E.; Gürkan, E.H.; Terzi, Ö.; Çoruh, S. Leaching Performance and Zinc Ions Removal from Industrial Slag Leachate Using Natural and Biochar Walnut Shell. Environ. Manag. 2021, 67, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shao, Y.; He, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, H.; Yang, S.; Chang, J.; Jiang, F. Current Status and Prospects of Comprehensive Recovery of Valuable Metals in Zinc Kiln Slag. Conserv. Util. Miner. Resour. 2019, 39, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Osto, G.; Mombelli, D.; Scolari, S.; Mapelli, C. Iron Recovery from Waelz Slag through Biogenic Carbothermic Reduction. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 3050, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, Y. Process optimization of preparing glass-ceramic from secondary slag of zinc extraction. Nonferrous Met. Sci. Eng. 2020, 11, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.L.; Recksiek, V.; Blenau, L.; Kelly, N.; Ebert, D.; Guy, B.M.; Viswamsetty, L.K.; Stelter, M.; Charitos, A.; Vaisanen, A.O.; et al. Sustainable Valorization of Waelz Slag: Recovery of Zinc, Manganese, and Iron with Slag Stabilization. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Lu, Y.; Li, L.; Ge, D.; Yang, H.; Leng, W.; Zhou, H.; Han, X.; Schmidt, N.; Ellis, M.; et al. An Effective Relithiation Process for Recycling Lithium-Ion Battery Cathode Materials. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2020, 4, 1900088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, P.; Stefanova, V.; Lucheva, B.; Kolev, D. Selective Autoclave Recovery of Copper and Silver from Waelz Clinker in Ammonia Medium. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2017, 52, 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K.; Guo, Z.; Xiao, X.; Wei, X. Effect of Moderately Thermophilic Bacteria on Metal Extraction and Electrochemical Characteristics for Zinc Smelting Slag in Bioleaching System. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 3120–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenepalli, T.; Chilakala, R.; Habte, L.; Tuan, L.Q.; Kim, C.S. A Brief Note on the Heap Leaching Technologies for the Recovery of Valuable Metals. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuk, P.; Melcher, F. Mineralogical and Chemical Quantification of Waelz Slag. Int. J. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. 2022, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, V.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Vithanage, M.; Alessi, D.S.; Selvasembian, R.; Naushad, M.; You, S.; Oleszczuk, P.; Ok, Y.S. Hydrometallurgical Processes for Heavy Metals Recovery from Industrial Sludges. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 1022–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Tan, S.; Sun, Z.; Ke, Y.; Peng, C.; Min, X. Near-Zero-Waste Processing of Jarosite Waste to Achieve Sustainability: A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeev, D.; Mikhailova, A.; Atmadzhidi, A. Kinetics of Iron Extraction from Coal Fly Ash by Hydrochloric Acid Leaching. Metals 2018, 8, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q. Novel Process for Comprehensive Utilization of Iron Concentrate Recovered from Zinc Kiln Slag. In Extraction 2018; Davis, B.R., Moats, M.S., Wang, S., Gregurek, D., Kapusta, J., Battle, T.P., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.-H.; Li, Q. Leaching of Iron Concentrate Separated from Kiln Slag in Zinc Hydrometallurgy with Hydrochloric Acid and Its Mechanism. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2017, 27, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnik, E. Hydrometallurgical Treatment of EAF By-Products for Metal Recovery: Opportunities and Challenges. Metals 2025, 15, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Du, P.; Zhang, L.; Long, Y.; Zhang, J. Stepwise extraction of zinc, indium and lead from secondary zinc oxide dusts experimental study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, Z.A. Greener and Sustainable Production: Production of Industrial Zinc (II) Acetate Solution and Recovery of Some Metals (Zn, Pb, Ag) from Zinc Plant Residue by Ultrasound-Assisted Leaching. J. Sustain. Metall. 2024, 10, 1484–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Match! version 3.16. Phase Analysis Using Powder Diffraction. Crystal Impact: Bonn, Germany, 2024.

- Gražulis, S.; Chateigner, D.; Downs, R.T.; Yokochi, A.F.T.; Quirós, M.; Lutterotti, L.; Manakova, E.; Butkus, J.; Moeck, P.; Le Bail, A. Crystallography Open Database—An Open-Access Collection of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 726–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HSC Chemistry, version 9.9; Metso: Pori, Finland, 2023.

- Pitzer, K.S. Activity Coefficients in Electrolyte Solutions, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, M.P.; Waters, J.F.; Turner, D.R.; Dickson, A.G.; Clegg, S.L. Chemical Speciation Models Based upon the Pitzer Activity Coefficient Equations, Including the Propagation of Uncertainties: Artificial Seawater from 0 to 45 °C. Mar. Chem. 2022, 244, 104095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulaev, A.; Melamud, V. Two-Stage Oxidative Leaching of Low-Grade Copper–Zinc Sulfide Concentrate. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, D.J.; Graber, T.A.; Angel-Castillo, A.H.; Hernández, P.C.; Taboada, M.E. Use of Hydrogen Peroxide as Oxidizing Agent in Chalcopyrite Leaching: A Review. Metals 2025, 15, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, Y.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Low, Y.C.; Choong, S.W.; Low, K.O. Hydrometallurgical Extraction of Zinc and Iron from Electric Arc Furnace Dust (EAFD) Using Hydrochloric Acid. J. Phys. Sci. 2018, 29, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Staden, P.J.; Petersen, J. Towards Fundamentally Based Heap Leaching Scale-Up. Miner. Eng. 2021, 168, 106915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Yi, B.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Han, Y.; Deng, Z.; Hu, X.; Chen, M.; Gong, J. Enhancing Co, Mo and Al Leaching from Spent HDS Catalysts during Scale-up Process Based on Fluid Dynamic and Leaching Mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 359, 130554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Q.; Xun, L.; Zhen, S.; Liu, D. The Investigation of Optimizing Leaching Efficiency of Al in Secondary Aluminum Dross via Pretreatment Operations. Processes 2020, 8, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delina, R.E.G.; Perez, J.P.H.; Stammeier, J.A.; Bazarkina, E.F.; Benning, L.G. Partitioning and Mobility of Chromium in Iron-Rich Laterites from an Optimized Sequential Extraction Procedure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 6391–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, M.G. Dissolution Kinetics of Chromite in Hydrochloric Acid Solutions. Philipp. Eng. J. 1990, 11, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, A.A.; Adekola, F.A. Hydrometallurgical Processing of a Nigerian Sphalerite in Hydrochloric Acid: Characterization and Dissolution Kinetics. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 101, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo-Rodríguez, N.G.; Soria-Aguilar, M.D.J.; Martínez-Luévanos, A.; Almaguer-Guzmán, I.; Chaidez-Félix, J.; Carrillo-Pedroza, F.R. Direct Acid Leaching of Sphalerite: An Approach Comparative and Kinetics Analysis. Minerals 2020, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, R.T.; Ford, R.G. Use of Hydrochloric Acid for Determining Solid-Phase Arsenic Partitioning in Sulfidic Sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 4921–4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadmahmoudi, G.; Karimi, S.; Abdollahi, H.; Karimi, M.; Rezaei, A.; Alagha, L. Electrochemical Insights into the Direct Dissolution of Impure Sphalerites and Their Partial Oxidation in an Acidic Environment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrijević, M.; Antonijević, M.M.; Dimitrijević, V. Investigation of the Kinetics of Pyrite Oxidation by Hydrogen Peroxide in Hydrochloric Acid Solutions. Miner. Eng. 1999, 12, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitai, A.G.; Gablina, I.F.; Bol’shikh, A.O. Formation of Elemental Sulfur during the Oxidation Leaching of Chalcocite. Russ. Metall. 2022, 2022, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Dai, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Application of Zero-Valent Iron Nanoparticles for the Removal of Aqueous Zinc Ions under Various Experimental Conditions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, S.; Johnson, M.D.; Korfiatis, G.P.; Meng, X. Chemical Reactions between Arsenic and Zero-Valent Iron in Water. Water Res. 2005, 39, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Parsons, C.T.; Slowinski, S.; Van Cappellen, P. Co-Precipitation of Iron and Silicon: Reaction Kinetics, Elemental Ratios and the Influence of Phosphorus. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xie, Z.; Yang, Y.; Gao, B.; Wang, J. Effects of Calcium on Arsenate Adsorption and Arsenate/Iron Bioreduction of Ferrihydrite in Stimulated Groundwater. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyaev, A.; Wilson, B.P.; Lundström, M. Study on Valuable Metal Incorporation in the Fe–Al Precipitate during Neutralization of LIB Leach Solution. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Li, Z.; Zuo, X.; Chen, J.; Shakiba, S.; Louie, S.M.; Rixey, W.G.; Hu, Y. Coprecipitation of Fe/Cr Hydroxides with Organics: Roles of Organic Properties in Composition and Stability of the Coprecipitates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 4638–4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Saunders, J.A. Effects of pH on Metals Precipitation and Sorption: Field Bioremediation and Geochemical Modeling Approaches. Vadose Zone J. 2003, 2, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Van Genuchten, C.M. Deep-Dive into Iron-Based Co-Precipitation of Arsenic: A Review of Mechanisms Derived from Synchrotron Techniques and Implications for Groundwater Treatment. Water Res. 2024, 249, 120970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheck, J.; Lemke, T.; Gebauer, D. The Role of Chloride Ions during the Formation of Akaganéite Revisited. Minerals 2015, 5, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushi, K.; Aoyama, K.; Yang, C.; Kitadai, N.; Nakashima, S. Surface Complexation Modeling for Sulfate Adsorption on Ferrihydrite Consistent with in Situ Infrared Spectroscopic Observations. Appl. Geochem. 2013, 36, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudinsky, P.; Vasileva, E.; Dyubanov, V. Recycling Potential of Copper-Bearing Waelz Slag via Oxidative Sulfuric Acid Leaching. Metals 2025, 15, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, M.L. Initial Steps in the Reaction of H2O2 with Fe2+ and Fe3+ Ions: Inconsistency in the Free Radical Theory. Reactions 2023, 4, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.J.; Wen, S.M.; Deng, J.S.; Liu, J.; Nie, Q. Leaching chalcopyrite with sodium chlorate in hydrochloric acid solution. Can. Metall. Q. 2012, 51, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujić, S.; Popović, M.P.; Conić, V.; Janošević, M.; Alimpić, F.; Bajić, D.; Milenković-Anđelković, A.; Abramović, F. Ozone/Thiosulfate-Assisted Leaching of Cu and Au from Old Flotation Tailings. Molecules 2025, 30, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yussupov, K.; Aben, E.; Akhmetkanov, D.; Aben, K.; Yussupova, S. Investigation of the solid oxidizer effect on the metal geotechnology efficiency. Min. Miner. Depos. 2023, 17, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.M.; Ghorbani, Y.; Hernández, P.C.; Justel, F.J.; Aravena, M.I.; Herreros, O.O. Cupric and Chloride Ions: Leaching of Chalcopyrite Concentrate with Low Chloride Concentration Media. Minerals 2019, 9, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumbo-Pacheco, P.; Townley, B.; Kelm, U.; Vargas, T. Chloride leaching of copper ores: Influence of NaCl on gangue dissolution and its effect on copper leaching kinetics. Miner. Eng. 2025, 233, 109640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughlaimi, I.; Bakher, Z.; Toukhmi, M.; Zouhri, A. Evaluation and Comparative Analysis of Heavy Metal Leaching Efficiency by Nitric Acid, Perchloric Acid and Sulfuric Acid from Moroccan Phosphate Solid Waste. Turk. Chem. Soc. Sect. B Chem. Eng. 2025, 8, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoraga, M.; Yucel, T.; Ilhan, S.; Kalpakli, A.O. Investigation of Selective Leaching Conditions of ZnO, ZnFe2O4 and Fe2O3 in Electric Arc Furnace Dust in HNO3. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2022, 87, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S.; Ghosh, A.; Saravanan, V.; Jain, R. Hydrometallurgical separation of iron and copper from copper industrial dust waste and recovery of copper as copper oxide. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action. 2025, 7, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, A.; Čopák, L.; Golubenko, D.; Dvořák, L.; Vavro, M.; Yaroslavtsev, A.; Šeda, L. Recovery of Hydrochloric Acid from Industrial Wastewater by Diffusion Dialysis Using a Spiral-Wound Module. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Chiang, W.-P.; Hsieh, P.-Y. Recovery of Kish Graphite from Steelmaking Byproducts with a Multi-Stage Froth Flotation Process. Recycling 2023, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, P.A.; Khodyko, I.I.; Poroshin, E.A.; Ivakin, D.A. Use of Petroleum Coke in the Waelz Process. Tsvetnye Met. 2019, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, M.; Di Maio, F.; Sprecher, B.; Yang, X.; Tukker, A. An Overview of the Waste Hierarchy Framework for Analyzing the Circularity in Construction and Demolition Waste Management in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 803, 149892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, R.P.; Srikant, S.S.; Rao, R.B.; Mohanty, B. Recovery of Basic Valuable Metals and Alloys from E-Waste Using Microwave Heating Followed by Leaching and Cementation Process. Sādhanā 2019, 44, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temur, H.; Yartaşı, A.; Kocakerim, M.M. A Study on the Optimum Conditions of the Cementation of Copper in Chlorination Solution of Chalcopyrite Concentrate by Iron Scraps. BAÜ Fen. Bil. Enst. Derg. 2006, 8, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Shishkin, A.; Mironovs, V.; Vu, H.; Novak, P.; Baronins, J.; Polyakov, A.; Ozolins, J. Cavitation-Dispersion Method for Copper Cementation from Wastewater by Iron Powder. Metals 2018, 8, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-España, J.; Ilin, A.; Yusta, I. Metallic Copper (Cu[0]) Obtained from Cu2+-Rich Acidic Mine Waters by Two Different Reduction Methods: Crystallographic and Geochemical Aspects. Minerals 2022, 12, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konaté, F.O.; Vitry, V.; Yonli, A.H. Leaching of Base Metals in PCBs and Copper Cementation by Iron Powder. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 15, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iepure, G.; Pop, A. Treatment of Acid Mine Water from the Breiner-Băiuț Area, Romania, Using Iron Scrap. Water 2025, 17, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Ji, W.; Lin, X. Reductive Leaching Kinetics of Indium and Further Selective Separation by Fraction Precipitation. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xia, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, H.; Zheng, G. Effective cementation and removal of arsenic with copper powder in a hydrochloric acid system. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 70832–70841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Li, G.; He, D.; Fu, X.; Sun, W.; Yue, T. Resource-Recycling and Energy-Saving Innovation for Iron Removal in Hydrometallurgy: Crystal Transformation of Ferric Hydroxide Precipitates by Hydrothermal Treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeonidis, K.; Papadopoulou, V.; Tresintsi, S.; Kokkinos, E.; Katsoyiannis, I.; Zouboulis, A.; Mitrakas, M. Efficiency of Iron-Based Oxy-Hydroxides in Removing Antimony from Groundwater to Levels below the Drinking Water Regulation Limits. Sustainability 2017, 9, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, I.; Filoni, L.; Poli, M.; Apollonio, C.; Petroselli, A. Regenerating Iron-Based Adsorptive Media Used for Removing Arsenic from Water. Technologies 2023, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.Y.; Cheong, Y.W.; Yim, G.J.; Min, K.W.; Geroni, J.N. Recovery of Fe, Al and Mn in Acid Coal Mine Drainage by Sequential Selective Precipitation with Control of pH. CATENA 2017, 148, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulos, P.; Agatzini-Leonardou, S.; Oustadakis, P.; Tsakiridis, P.E. Zinc Recovery from Purified Electric Arc Furnace Dust Leach Liquors by Chemical Precipitation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3550–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.E. Review of Metal Sulphide Precipitation. Hydrometallurgy 2010, 104, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.K.; Kumar, V.; Singh, R.J. Review of Hydrometallurgical Recovery of Zinc from Industrial Wastes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2001, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fe | Ca | Si | Al | Mg | Mn | Na | K | P | S | Zn | Cu | Pb | As | Sb | Ni | Ti | V | Cr | Ba | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26.23 | 8.99 | 5.40 | 2.80 | 4.40 | 2.00 | 0.54 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 2.20 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 0.066 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 17.1 |

| Element | Chemical Composition, wt. % | Remaining in the Residue (%β) | Recovery into the Leachate (%ω) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | 5.89 | 8.6 ± 2.3 | 91.4 ± 2.3 |

| Cu | 0.35 | 16.3 ± 4.5 | 83.7 ± 4.5 |

| Zn | 0.34 | 15.9 ± 4.5 | 84.1 ± 4.5 |

| Al | 1.28 | 17.4 ± 2.6 | 82.6 ± 2.6 |

| As | 0.49 | 55.3 ± 2.4 | 44.7 ± 2.4 |

| Ba | 0.37 | 70 ± 1.6 | 30 ± 1.6 |

| Ca | 1.00 | 4.3 ± 3.1 | 95.7 ± 3.1 |

| Cd | 0.0039 | 7.1 ± 3.0 | 92.9 ± 3.0 |

| Cr | 0.73 | 69.5 ± 1.6 | 30.5 ± 1.6 |

| K | 0.43 | 77.3 ± 1.2 | 22.7 ± 1.2 |

| Mg | 0.64 | 5.6 ± 5.1 | 94.4 ± 5.1 |

| Mn | 0.36 | 6.9 ± 5.0 | 93.1 ± 5.0 |

| Na | 0.16 | 11.3 ± 4.8 | 88.7 ± 4.8 |

| Ni | 0.008 | 4.6 ± 9.7 | 95.4 ± 9.7 |

| P | 0.355 | 84.5 ± 0.8 | 15.5 ± 0.8 |

| Pb | 0.064 | 8.1 ± 9.4 | 91.9 ± 9.4 |

| Sb | 0.11 | 71.7 ± 1.5 | 28.3 ± 1.5 |

| Si | 12.07 | 85.1 ± 0.5 | 14.9 ± 0.5 |

| Ti | 0.36 | 98.8 ± 0.07 | 1.2 ± 0.07 |

| C | 43.5 | 96.9 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.1 |

| S | 4.0 | 69.3 ± 0.98 | 30.7 ± 0.98 |

| Cl | 2.19 | n/a 1 | n/a |

| Element | Spectrum Point | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| C | 98.8 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Si | 0.6 | 28.8 | 3.9 | - | 1.4 | - |

| S | 0.3 | 2.2 | 87.3 | 69.2 | 48.6 | 67.0 |

| Ti | 0.2 | 0.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Al | 0.1 | 0.7 | - | - | - | - |

| O | - | 60.5 | 8.1 | - | 3.1 | - |

| Fe | - | 3.4 | 0.3 | 30.8 | 5.1 | - |

| Cl | - | 2.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Cr | - | 0.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Ba | - | 0.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Cu | - | 0.2 | - | - | - | 33.0 |

| As | - | 0.2 | - | - | - | - |

| Mg | - | 0.5 | - | - | - | - |

| P | - | 0.5 | - | - | - | - |

| Ca | - | - | 0.3 | - | - | - |

| Zn | - | - | - | - | 40.1 | - |

| Mn | - | - | - | - | 1.6 | - |

| Element | Composition of Initial Mother Leachate, mg/L (V = 50 mL) | Composition of Solution After Cementation, mg/L (Dilution to 100 mL) | Recovery from the Leachate into the Cementation Product, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | 28,090 | 15,200 | −6.8 1 |

| Cu | 830 | 4.5 | 98.9 |

| Zn | 788 | 330 | 16.2 |

| As | 102 | 4.5 | 91.2 |

| Cd | 23.1 | 11.5 | 0.43 |

| Spectrum Point | Element | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | Fe | Cl | O | S | Si | |

| 7 | 18.7 | 15.3 | 15.9 | 49.1 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Approach | Fraction (Mass) | Index | Element | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | Al | Cr | Sb | Mn | Zn | Cu | Pb | As | Cd | Ni | |||

| One-step | Single (100%) | CC, wt.% | 36.1 | 1.52 | 0.11 | 0.002 | 0.42 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.043 | 0.006 | 0.027 |

| %ω | 93.8 | 85.1 | 81.3 | 23.2 | 14.7 | 57.8 | 1.6 | 62.6 | 30.5 | 18.1 | 50.9 | ||

| ±Δ%ω | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 0.04 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.4 | ||

| Two-step | First (28.9%) | CC, wt.% | 38.0 | 3.53 | 0.65 | 0.015 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.188 | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| %ω | 20.8 | 41.6 | 97.1 | 40.7 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 11.2 | 28.3 | 1.9 | 1.8 | ||

| ±Δ%ω | 0.6 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.05 | 0.05 | ||

| Second (71.1%) | CC, wt.% | 52.2 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | |

| %ω | 70.1 | 23.1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 6.5 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.2 | ||

| ±Δ%ω | 2 | 0.7 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.014 | 0.026 | 0.015 | 0.185 | 0.008 | 0.017 | 0.033 | ||

| Spectrum Point | Element | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | Al | Ca | Mg | Na | Zn | Pb | As | P | Cr | Si | S | Cl | O | |

| 8 | 23.1 | 6.1 | 2.1 | 0.4 | - | 0.3 | 1.5 | - | - | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 12.9 | 51.4 |

| 9 | 11.2 | 4.5 | 0.3 | - | - | - | - | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | - | 0.8 | 6.1 | 76.3 |

| 10 | 25.0 | 1.4 | 0.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.8 | 9.3 | 63.1 |

| 11 | 18.9 | 1.2 | 0.2 | - | 1.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.6 | 7.8 | 69.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grudinsky, P.; Vasileva, E.; Dyubanov, V. Zinc Kiln Slag Recycling Based on Hydrochloric Acid Oxidative Leaching and Subsequent Metal Recovery. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210171

Grudinsky P, Vasileva E, Dyubanov V. Zinc Kiln Slag Recycling Based on Hydrochloric Acid Oxidative Leaching and Subsequent Metal Recovery. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210171

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrudinsky, Pavel, Ekaterina Vasileva, and Valery Dyubanov. 2025. "Zinc Kiln Slag Recycling Based on Hydrochloric Acid Oxidative Leaching and Subsequent Metal Recovery" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210171

APA StyleGrudinsky, P., Vasileva, E., & Dyubanov, V. (2025). Zinc Kiln Slag Recycling Based on Hydrochloric Acid Oxidative Leaching and Subsequent Metal Recovery. Sustainability, 17(22), 10171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210171