To address the objective of assessing the economic effects of adopting a holistic sustainability approach, we investigate the short-term economic impact of a three-pillar sustainable certification on Italian wineries. The decision to focus on the short-term is primarily based on the relatively recent adoption of these standards, which means that sufficient data for conducting long-term analyses is not yet available. In addition, from a theoretical perspective, a negative economic impact in the short term could constitute a barrier for the adoption of this type of certification and, more generally, for engaging in sustainability pathways. Indeed, although there may be benefits in the long term, companies could be discouraged by the prospect of making substantial investments or facing initial costs that are not immediately offset by market advantages. For these reasons, a short-term analysis results particularly relevant.

To estimate the economic impact of the adoption of the certification on wineries, we followed a structured logical strategy to conduct the analysis:

In the following, all the mentioned steps of the impact analysis implementation are illustrated in detail.

3.1. Economic Indicators and Causal Model

The effect of the certification on economic performance was evaluated considering two economic dimensions: profitability and liquidity. Structural indicators, such as those related to financial solidity or independence, were not included, as they are less meaningful in a short-term perspective. These indicators reflect in fact the financial structure and long-term sustainability of a firm, typically influenced by strategic decisions and investment that unfold over extended periods. Since this study aims to assess the short-term effects of certification, it is more appropriate to focus on more immediate outcomes, such as profitability and liquidity indicators, rather than on structural variables whose variation generally requires a longer time horizon.

Specifically, EBITDA/Sales and ROA were used to measure the impact of the sustainable certification on wineries’ profitability. The choice fell on these two indicators because, compared to others such as ROI, ROE (Return on Equity) or ROS, they allow for more direct and effective assessment of operational profitability and efficiency in the use of company resources. ROA and EBITDA/Sales are widely used in financial analysis and provide timely signals of operational and strategic changes, thus aligning coherently with the objective of assessing the short-term impacts of sustainability certification [

48,

49]. EBITDA (Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) divided by sales, measures the operational efficiency of a company expressing its ability to generate profits from its operations. A variation in this indicator for sustainable wineries may be due to a different level of operating costs or to different volumes and/or prices of the sales. On the other hand, the ROA measures the profitability of a firm relative to its total assets and thus helps to understand how much profit a company can generate with its assets. Again, a variation in ROA for sustainable wineries could be due to a different degree of efficiency in the management of resources.

Liquid ratio (LR) and Current Ratio (CR) were used to evaluate the impact of sustainable certification on liquidity. The literature on measuring the effects of adopting sustainable practices on liquidity is rather limited, especially in a short period. Therefore, the choice fell on these indicators as they are reliable and commonly used measures to assess a company’s ability to meet its short-term financial obligations [

50]. The LR expresses a company’s ability to cover its short-term liabilities with its liquid assets. The CR measures a company’s ability to cover its current liabilities with its total current assets (also including inventories). Compared to LR, CR is less stringent as it also includes inventories, which may not be easily convertible to cash. Both indexes express the short-term financial strength of a company, and their potential variation for sustainable wineries could be due to a different ease of access to credit by obtaining financing with more or less favorable terms or, again, due to different efficiency of resource management or different levels of sales and revenues.

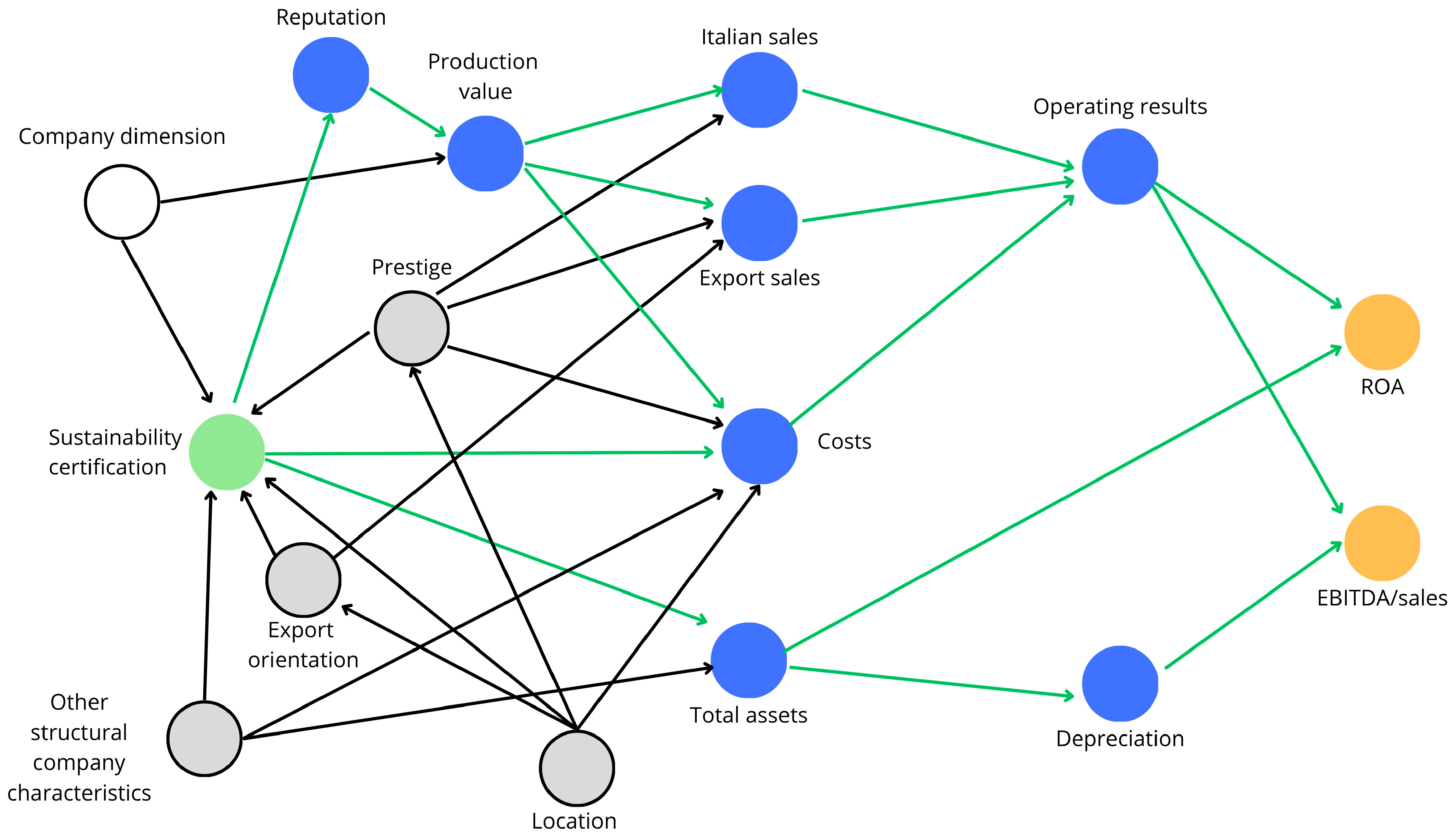

The logic behind the effects of the certification on the outcome indicators is represented in the form of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs—

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). In impact evaluation, DAGs play a double role. First, they are a useful way to stimulate analytical reasoning about the causal relationships between the treatment, the outcomes, and other factors possibly affecting these relationships. Second, they allow, through a set of standardized rules, to identify potential confounders to control for in the analysis in order to avoid biased causal estimates. The last feature is particularly important, as it allows the researcher to select the estimation technique and the econometric model specification based on theory. Conversely, when the covariates are included blindly in the model specification, without considering their position within the causal chain, biases may be introduced, thus distorting the causal effect that is the object of estimation [

51].

As such, the DAGs in the figures visually represent how sustainability certification is hypothesized to affect wineries’ profitability (

Figure 1) and liquidity (

Figure 2) through a network of direct and indirect pathways mediated by various economic variables.

In terms of profitability, it is hypothesized that certification affects performance through three main channels. Operationally, certification (Sustainable certification in the figure) may lead to changes in the company’s cost structure (Costs). While sustainable practices could generate savings in the medium to long term (e.g., through increased efficiency), they may result in higher initial costs. In addition, the certification cost itself (i.e., the fee to pay to be certified) adds to the standard operating costs, increasing them. Higher operating costs, in turn, negatively affect the operating income (Operating results), influencing both EBITDA/Sales and ROA values.

On the asset side, certification may require new investments in sustainable processes and technologies, increasing the value of Total assets. On the one hand, the increased value of assets, if not matched by an equivalent increase in operating results, directly lowers the ROA. On the other hand, asset increase leads to increased Depreciation, potentially negatively impacting also EBITDA/Sales.

In terms of potential benefits, the certification may increase the Reputation of the company, a particularly relevant element in the wine sector, where product image and perceived quality play a central role in purchasing decisions. In a market perspective, a higher Reputation is expected to lead to increased demand, which might be reflected (i) in higher quantities sold at the same price, (ii) in the same quantity sold at a higher price, or (iii) in a combination of the two. In all these cases, this leads to an increase in the Production value, which can be allocated in the national (Italian sales) and/or in the export (Export sales) market in different shares, producing an increase in Operating results.

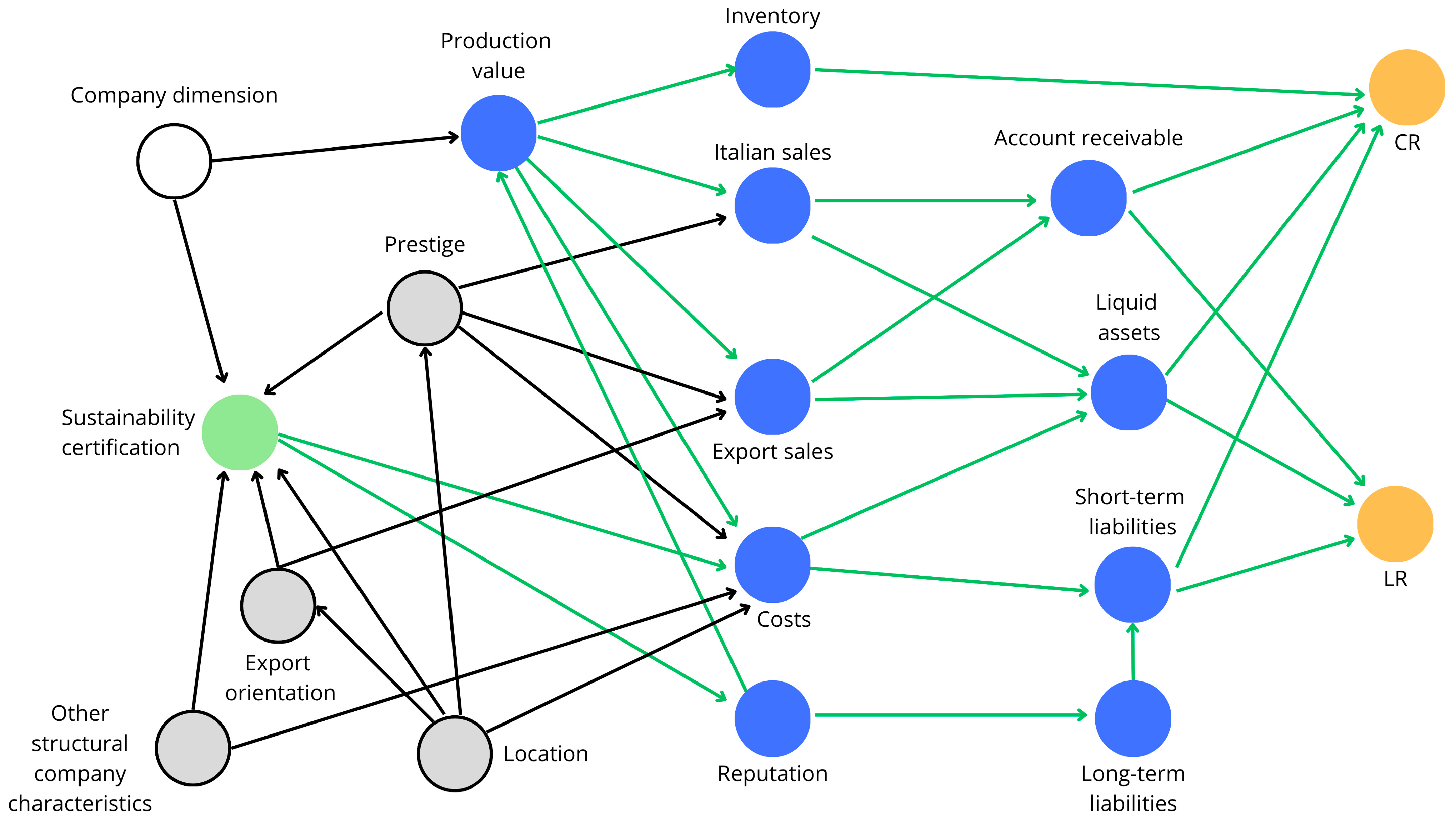

The second DAG (

Figure 2) describes the hypothesized relationships between certification and liquidity performance. Again, certification can influence liquidity through multiple mechanisms. First, the certification may contribute to the improvement of corporate

Reputation. On the one hand, the effect of

Reputation is similar to that observed for profitability indicators. In terms of liquidity, the higher values of national and export sales are expected to generate more liquid assets and accounts receivable, directly modifying the target indicators. On the other hand, a stronger reputation could increase the trust of financial institutions and other stakeholders, facilitating access to credit and leading to a reduction in

Long-term liabilities. The decrease in long-term debt, in turn, could reduce the need to resort to

Short-term liabilities, with positive effects on both liquidity indicators. Conversely, a higher level of long-term debt, resulting from substantial investments in sustainability, could also affect short-term indebtedness, potentially worsening liquidity indicators.

In addition, higher production levels naturally lead to increased Inventory levels. While inventories do not influence the LR, they represent an essential component of current assets, thereby positively affecting the CR. Finally, the certification can have an additional effect on liquid assets, modifying the company’s cost structure. As illustrated before, the certification may produce an increase in the operating costs, at least in the short run, potentially affecting the accumulation of Liquid assets and Accounts receivable.

In both graphs, it is possible to identify a set of contextual variables that may simultaneously influence both the likelihood of obtaining sustainability certification and the economic performance under analysis. Specifically,

Company dimension,

Prestige,

Export orientation, Location and

Other structural company characteristics (such as type of company, characteristics of decision makers) are included in the DAGs as potential confounding variables. Although these do not play a mediating role between certification and economic performance, they can affect both dimensions, introducing potential bias if not properly controlled for [

51].

Larger firms generally have greater financial and organizational resources and are more exposed to stakeholder pressures, elements that may favor the adoption of sustainable certification schemes. At the same time, financial strength and potentially easier access to credit could translate into better liquidity positions, positively affecting the CR and LR. In addition, economies of scale and operational efficiency typical of larger firms could contribute to improved profitability, reflecting on indicators such as EBITDA/Sales and ROA [

39].

Similarly, firms characterized by high prestige, understood as the quality level of their productions, may be more inclined to adopt certifications, as they are consistent with a strategy oriented toward excellence and adherence to high standards throughout the production chain. This quality orientation, in addition to supporting profitability through the ability to charge higher prices, can also articulately affect liquidity.

Export orientation could influence both the propensity for certification and economic performance [

25]. More internationalized firms, in fact, may find themselves needing to adapt to more stringent environmental and social standards demanded by foreign markets, which could incentivize the adoption of certification. In addition, access to diversified and, in some cases, higher value-added markets could boost profitability. With regard to liquidity, export activity could have mixed effects: on the one hand, it could prolong the time it takes to collect trade receivables; on the other hand, access to more solid and reliable customers could strengthen financial stability and support, in particular, the CR.

Location can also influence both profitability and liquidity. In particular, it affects not only access to markets and services, but also cost structure and expected revenues, especially when companies operate in areas characterized by different reputations or take part in more or less profitable appellations, influencing both economic performance and propensity to adopt sustainability standards.

Finally, other structural characteristics of the company, such as the type of company in terms of ownership structure or characteristics of decision makers, can influence both profitability and liquidity and the propensity to adopt sustainability certifications. Firms with more articulated corporate structure or managerial management tend to have greater organizational and financial resources, which facilitate the adoption of sustainable standards and more efficient cost and liquidity management. Similarly, decision makers with high education or innovation orientation are more sensitive to the strategic benefits of certification [

52].

3.2. Data and Econometric Strategy

To assess the impact of sustainability certifications on firms’ economic performance, we use data extracted from the AIDA platform (last consultation March 2025). AIDA is a public database containing annual financial statement data of Italian companies for which financial reporting is mandatory. The database includes information on key economic indicators such as revenue, assets, profitability and liquidity.

In structuring the impact analysis, the treatment is represented by the achievement of the Sustainable Organization certification according to the Equalitas SOPD (Sustainable Organization–Product–Designation of origin) standard. Equalitas is, together with VIVA—Sustainability in vitiviniculture (the public standard developed in 2011 by the Ministry of Environment and Energy Security) [

53], one of the two sustainability standards in the Italian wine sector. It is promoted by Federdoc, the National Confederation of Voluntary Consortia for the Protection of Italian Wine Denominations and provides a holistic approach to sustainability. In fact, the Equalitas standard requires the adoption of a structured sustainability management system. In line with its nature of a three-pillar sustainability certification, this scheme is based on the integration of environmental, social and economic requirements that affect the entire wine supply chain: from vineyard management, winemaking and bottling to relations with suppliers, workers and local communities, also including economic stability and communication practices. The standard promotes a systemic approach based on continuous improvement and objective measurement of performance through specific indicators, periodic audits and reporting tools, such as the sustainability report. In Italy, around 300 companies are certified under Equalitas SOPD standard, accounting for approximately 45% of the total revenue of the national wine sector.

Based on this definition of the treatment variable, the treated sample (TS) was selected by identifying from the Equalitas website (last consultation November 2024) the companies that achieved the SO certification in 2021–2022 and selecting those that had a public balance sheet on AIDA. The control sample (CS) was identified by selecting from AIDA the companies with an ATECO code–Italian Classification System used to categorize economic activities—corresponding to grape or wine production. Firms with the VIVA sustainable certification and in liquidation were excluded. In addition, the sample was further refined by excluding control companies with turnover above or below the maximum or minimum turnover of certified companies, considering a margin of +/−15%, in order to limit the impact analysis on a reliable common support region. The analysis was repeated using alternative thresholds of 5%, 10%, 20%: the results remained substantially stable, confirming the robustness of the findings. Cooperatives were excluded from both TS and CS since, given their goal of maximizing profits for members through the payment for grapes, they have indicators that are not comparable to those of private companies. Companies that did not have available all financial statement data necessary for the analysis were also excluded. This resulted in 59 companies for TS, of which 24 certified in 2021 and 35 certified in 2022, and 631 companies for CS.

To understand which factors we need to control for to obtain unbiased estimates of the causal effects of interest, we applied the back-door criterion [

51] on the DAGs reported in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. The back-door criterion postulates that one should control for (and only for) those variables that affect both the treatment (in our case, the decision to certify) and the outcome (in our case, the profitability and liquidity indicators). Following this logic, five confounders (i.e., variables that may bias the target causal estimate) are identified:

Company dimension,

Prestige,

Export,

Location and Other structural characteristics. These contextual variables and their effects on both certification and on outcomes are already presented in

Section 3.1. Economic indicators and causal model. One of them,

Company dimension, is observable, since the AIDA dataset, reporting information on companies’ turnover, makes it possible to measure their economic size. Therefore, this variable was used as a control variable to take into account differences in firms’ economic size that might affect the results.

However, the other confounders remain unobservable, since the AIDA dataset does not contain suitable data to measure them. Since failing to control for them would, according to our causal model, introduce a bias in the estimation of the economic impacts of the certification, we exploit the panel nature of the dataset. Because firms voluntarily decide to obtain the certification rather than being exposed to an exogenous intervention, we adopt a DiD framework, which allows us to control for unobserved firm- and owner-specific characteristics that are stable over time. In fact, a key strength of the DiD approach is its capacity to control for time-invariant factors that may otherwise confound the relationship between treatment and outcome [

54]. Among the factors assumed to be time-invariant, in addition to the companies’ structural characteristics, we can include regional characteristics (Location), such as natural conditions, regional market reputation, or policy support. Since the unbiasedness of the results critically hinges on this assumption, we decided to conduct the analysis over a 6-years period (from 2018 to 2023), where the assumption is more reliable.

In addition, since different companies certify in different years, the evaluation context is one of staggered treatment adoption. When the adoption of the treatment is staggered, its effect can be heterogeneous, depending on the year when a unit receives the treatment, on the year when the effect is measured, or on the time spent under the treatment. Treatment effect heterogeneity has been observed for other certification schemes [

55] and introduces a potential bias when using the classical two-way fixed effect (TWFE) estimator [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. To address this issue, the estimation of the certification effect is performed computing the Weighted Average of Slopes (WAS) through the nonparametric estimator introduced by [

61], which overcomes the issues connected with the standard TWFE estimator. Like other non-parametric estimators, it aims at identifying the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT) in its usual formulation in (1),

where

indicates the value of the outcome variable in the second time period,

indicates the treatment status at period

,

is a treatment indicator (1 for treated units, 0 for control units), and

is a vector of covariates. As already mentioned, in our case, the latter contains only the size of the company, as the others considered in the causal model are assumed to be time-invariant and therefore automatically controlled for by the DID nature of the estimator. For simplicity, we do not report here the full form of the estimator that allows to compute the counterfactual term (

), as its definition is not immediate and its explanation would require, in our opinion, an excessive load of technical information with respect to the objectives of this paper. The interested reader can directly refer to [

58] for a comprehensive understanding of the non-parametric estimator.

As a validity check, we tested the parallel trends assumption, conditional on the selected covariates, which requires that, in the absence of treatment, the evolution of the outcome for treated and untreated firms would have followed similar paths. The placebo estimators proposed in [

58] comparing pre-treatment trends of switchers and stayers are used for this purpose, ensuring that the identification strategy is credible.

_Li.png)