1. Introduction

“Trade-in for new”, as a new approach to recycling used products, is increasingly adopted by firms. It not only promotes the recycling and reuse of used products but also increases the sales of new products [

1], consolidates the consumer base [

2], and boosts firm profits [

3]. It is reported that many home appliance firms have achieved performance growth through the “trade-in for new” marketing strategy. For instance, in 2023, the well-known Chinese home appliance brand Gree Electric Appliances announced an investment of 400 million dollars to launch a “trade-in for new” program for home appliances. This program is expected to bring its total operating revenue to between 28.4 billion and 29 billion dollars, representing a significant increase from 26.3 billion dollars in the previous year1. Beyond these business benefits, such programs deliver tangible environmental value amid the global e-waste crisis. According to the 2024 Global E-Waste Monitor [

4], global e-waste generation reached 62 million tons annually, with only 22% undergoing formal recycling; the remaining waste is often landfilled or informally dismantled, leading to severe soil and groundwater contamination. Concurrently, the extraction of virgin materials (e.g., cobalt for electronics, aluminum for appliances) accounts for approximately 15% of global carbon emissions. Trade-in programs, by facilitating the formal recovery and recycling of used products, deliver numerous environmental benefits, including reduced e-waste mismanagement and the substitution of virgin material demand [

5]. For instance, Apple’s trade-in program for iPhones enables the recovery of aluminum, cobalt, and rare earth elements, with each recycled device reducing the carbon footprint of new product manufacturing by 30–40% [

6]. This dual contribution—driving corporate growth while mitigating environmental harm—makes trade-in for new a pivotal practice aligned with the goals of the circular economy.

However, the trade-in models adopted by different firms vary. For example, companies such as The North Face, H & M, and Zara have adopted the trade-in for new model. Under this model, customers can return old goods or equipment to the merchant and offset part or all of the cost of purchasing new goods from the firm based on the assessed value of the old goods, thereby obtaining brand-new goods or equipment. However, some firms also adopt a trade-in for cash model. Consumers can directly exchange the products they recycle for cash returns without having to purchase any new products. Therefore, this model offers consumers greater flexibility. The American office supplies company Staples offers this model, allowing consumers to bring their old devices to their stores in exchange for cash returns. Additionally, some companies adopt both of the above trade-in models simultaneously. For instance, Samsung offers two trade-in models worldwide: the Samsung Recycling Express (i.e., trade-in for cash) and the Trade-in Program (trade-in for new). The American video game company GameStop offers a recycling service for video game software and hardware, allowing customers to offset the purchase of new products with old ones or receive cash returns directly. Despite the prevalence of these business practices, the determinants influencing firms’ adoption of distinct trade-in models remain underexplored in extant literature.

It is noteworthy that firms tend to adopt different pricing strategies when considering consumer segments. Some firms tend to attract new consumers to expand their potential market, such as Xiaomi, which offers new consumers coupons with no minimum spend through its official website. Others place more emphasis on repeat customers, believing that it is in their best interest to consolidate existing consumers and promote repeat purchases. Swedish furniture brand IKEA offers exclusive member benefits such as specific discounts, coupons or freebies to existing customers through its furniture membership program IKEA Family. Other firms believe that they should not emphasize all old customers, but rather focus on those who are more loyal. They believe that loyal consumers are a valuable resource for firms, and that they are more adherent to the company and bring higher value. Adidas, for example, has further segmented its membership program by setting a higher membership level for loyal consumers who have made more purchases or repeated purchases, thus offering more favorable prices. Moreover, an increasing number of studies demonstrate that loyal consumers also influence the retail price of products and the amount of rebate offered under various trade-in models, which has a significant impact on the choice of trade-in model [

7,

8]. Then, in such a segmented market environment, how should firms weigh and determine the consumer groups they focus on? Considering the far-reaching impact of loyal consumers, how should firms implementing the “trade-in” program set their product pricing and rebate strategies, and how will this affect their choice of trade-in model?

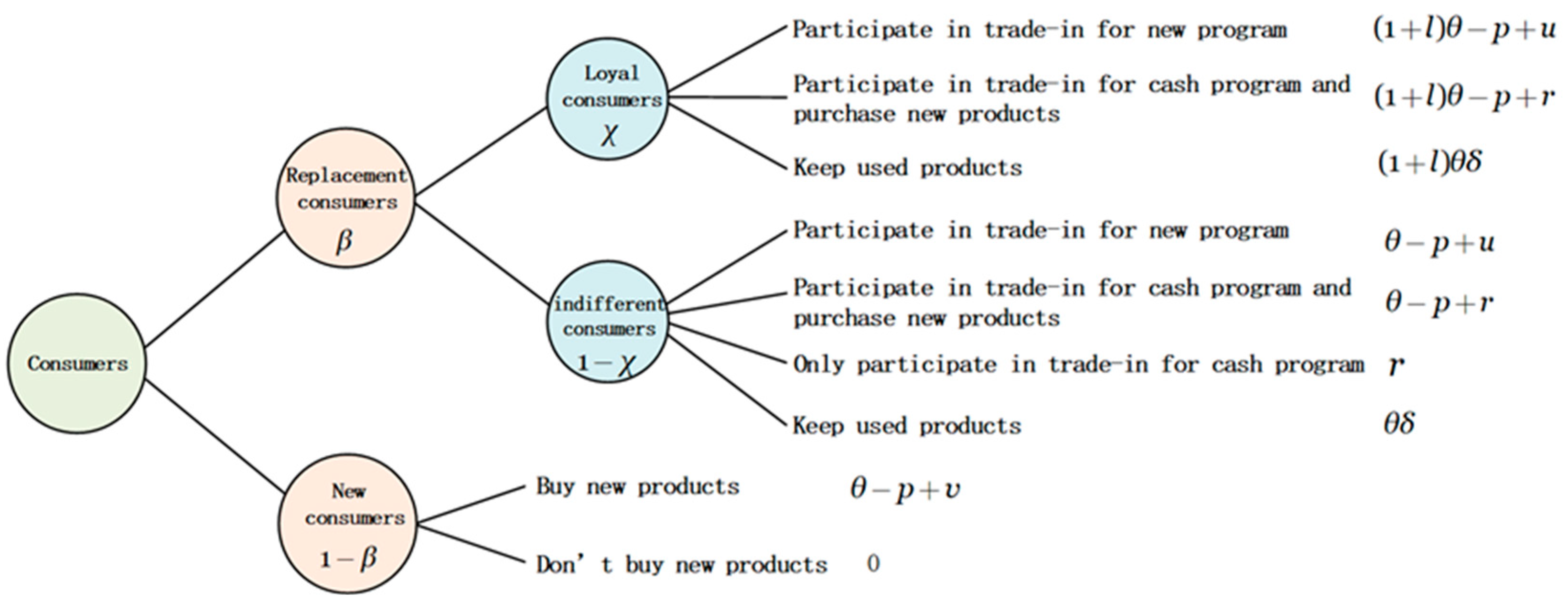

For this reason, this study divides the market into replacement consumers who have purchased the firm’s products and new consumers [

9]. Replacement consumers are further divided into loyal consumers and indifferent consumers [

6]. In the context of firm trade-in, by considering the influence of loyal consumers, the following questions are explored: (1) How should the firm set retail prices and rebates (trade-in rebates and cash rebates) under different trade-in models? (2) From the perspective of the firm, under the three models of trade-in, which market segment should firm target, specifically replacement consumers or new consumers? If the replacement consumers are captured, should the firm focus more on loyal consumers or indifferent consumers? (3) What is the optimal trade-in model for the firm? How does this model impact the loyal consumer group? How does this model change affect consumer surplus?

To answer the above questions, this paper focuses on a firm under three distinct trade-in models: namely, trade-in for new (Model N), trade-in for cash (Model C) and hybrid trade-in (Model H). Under Model N, the firm provides a special trade-in rebate to consumers who return used products, which can only be used when purchasing new products from the firm. Under Model C, the firm provides a cash rebate, which the consumer is free to dispose of, whether it is used for the purchase. Model H combines the features of the two models by offering both types of rebates. Meanwhile, to better capture the impact of consumer segmentation, we categorize consumers into replacement groups (loyal consumers and indifferent consumers) and new consumers, where loyal consumers have a higher perceived value of the product. With the help of consumer utility theory, we first solve the optimal retail price, rebate amount and profit for each model. Then, this paper discusses the influence of the proportion of different types of consumers on the optimal strategy and profit of firm, and clarifies the consumer groups that the firm should pay attention to under different trade-in models. Finally, by comparing the profits under the three-trade-in model, this paper determines the optimal trade-in model for the firm. In addition, by further analyzing the consumer surplus under different trade-in models, this paper will also obtain information about the impact of the trade-in model on consumers.

The analysis in this paper yields several important results. First, the generosity of the trade-in rebate under different models is significantly affected by the proportion of loyal consumers. Specifically, in the trade-in for new model (Model N), the firm reduces the rebate as the proportion of loyal consumers increases, leveraging their inherent brand stickiness to minimize incentive costs. In contrast, for the trade-in for cash (Model C) and hybrid (Model H) models, the firm adjusts the rebate amount based on segment composition. Second, the choice of the optimal trade-in model depends critically on the interaction between the proportion of loyal consumers and the rebate differential. For example, when the proportion of loyal consumers exceeds a certain threshold, the hybrid trade-in model becomes the dominant strategy, balancing loyal consumer retention with rebate incentives. Third, we find that the hybrid trade-in model consistently maximizes the consumer surplus of indifferent consumers due to its flexibility, while loyal consumers benefit more from the trade-in for new model when their market share is dominant.

This study makes three key contributions to the literature. First, this paper introduces a new market segmentation framework that distinguishes between loyal and indifferent consumers in the replacement consumer group, addressing a gap in prior trade-in research on the homogeneity of replacement behavior. By analytically modeling how loyalty-driven preferences affect pricing and rebates, we extend existing theories on consumer heterogeneity in trade-in programs. Second, we enrich the literature on trade-in models by systematically comparing trade-in for new model, trade-in for cash model, and hybrid trade-in models. Third, we provide actionable insights for firms: (i) trade-in for new models should target loyal consumers through tailored rewards (e.g., VIP privileges), whereas trade-in for new and hybrid models require firms to focus on indifferent consumers through promotions; and (ii) startups with lower loyalty adopt the trade-in for new model, whereas established firms with higher customer loyalty are advised to adopt the hybrid trade-in model that not only maximizes firm profits but also enhances consumers’ flexibility in choice. These implications are consistent with real-world practices, such as Apple’s “trade-in for new + cash” hybrid program, which caters to both loyal iPhone users and price-sensitive regular users.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature.

Section 3 describes the research questions and relevant assumptions of the paper.

Section 4 constructs and solves the model presented in this paper and performs sensitivity analysis on the optimal decisions.

Section 5 performs numerical examples to illustrate the impact of key parameters and the choice of the firm’s trade-in model more intuitively.

Section 6 summarizes the full paper, obtains the appropriate managerial insights and provides an outlook for future research. All proofs are placed in

Appendix A and

Appendix B for the reader’s convenience.

4. Analysis and Results

In this section, we first construct the decision models under the three trade-in models, then derive the corresponding optimal product retail prices and rebates, and finally analyze the impact of key parameters on firms’ decisions under each model. For clarity of model presentation, superscripts

N,

C and

H are used to denote trade-in for new, trade-in for cash and hybrid trade-in, respectively. See

Appendix A for the derivation of the optimal solutions and the detailed proof process for the analysis.

4.1. Model N

In the scenario where the firm exclusively offers trade-in for new programs, the demand for trade-in from loyal consumers and indifferent consumers is denoted as

,

, respectively, while the demand from new consumers is represented by

. Under this model configuration, the firm’s profits structure comprises three distinct components: (i) profits generated from trade-in transactions with loyal consumers, (ii) profits derived from trade-in transactions with indifferent consumers, and (iii) profits arising from new consumers’ purchases of new products. Consequently, within the framework of Model N, the firm is confronted with the following optimization problem:

Proposition 1. Under Model N, the optimal retail price of the firm’s product is , the trade-in rebates are , and the firm’s profit is The consumer surplus of loyal consumers is ,

the consumer surplus of indifferent consumers is ,

the consumer surplus of new consumers is , the specific expression can be found in Appendix A.

Proposition 1 demonstrates that an increase in the proportion of loyal consumers leads the firm to gradually reduce trade-in rebates (). Because when loyal consumers grow in market proportion, their trade-in demand rises notably due to brand stickiness, with higher per-unit demand intensity () than indifferent consumers (). While indifferent consumers’ demand declines, the growth from loyal one’s offsets this drop, keeping total profits positive at constant unit margins. Thus, the firm can expand trade-in profit margins by reducing rebates instead of stimulating replacement demand. From a managerial perspective, this conclusion provides clear guidance: when facing a growing loyal consumer base, firms can shift resources originally allocated to trade-in rebates to other value-adding activities (e.g., new product R&D or after-sales service) instead of over-relying on rebate incentives. Notably, under the trade-in model, retail prices are unrelated to loyal consumer proportion (i.e., ), tied only to newcomer coupons and production costs—both in positive linear correlation with prices (i.e., ).

4.2. Model C

Under Model C, loyal consumers compare the utility of exchanging products for cash rebates and repurchasing new products against retaining old products, i.e.,

, indifferent consumers have three options: participating in the trade-in for cash to obtain cash rebates and continuing to purchase the firm’s new products, participating in the trade-in for cash to obtain cash without purchasing new products, or not participating in any trade-in programs. The market demands generated by the first two decisions of indifferent consumers are, respectively:

The firm’s profits consist of four components: (i) profits from loyal consumers participating in trade-in for cash and purchasing new products, (ii) profits from indifferent consumers participating in trade-in for cash and purchasing new products, (iii) residual value revenue from indifferent consumers participating in trade-in for cash, and (iv) profits from new consumers purchasing products. Consequently, within the framework of Model C, the firm is confronted with the following optimization problem:

Proposition 2. Under Model C, the firm’s optimal retail price, cash rebates are

The consumer surplus of loyal consumers is , the consumer surplus of indifferent consumers is , the consumer surplus of new consumers is , several intriguing conclusions can be drawn from Proposition 2.

(1) When the proportion of loyal consumers exceeds a certain threshold, retail prices and cash rebates increase with the proportion of replacement consumers; otherwise, they decrease with the proportion of replacement consumers. Specifically, when , and ; conversely, when , and . When the proportion of loyal consumers exceed a certain threshold, their sustained demand and brand loyalty give firms stronger pricing power, allowing them to raise prices and cash rebates to encourage repeat purchases and upgrades. Conversely, below this threshold, market demand relies more on price-sensitive indifferent consumers, prompting firms to cut prices and rebates to attract them.

(2) When the proportion of indifferent consumers exceeds a certain threshold, the firm’s retail price increases with the proportion of loyal consumers; otherwise, the retail price decreases with the proportion of loyal consumers. Specifically, when ,; when , .

When the proportion of indifferent consumers exceed a certain threshold, indicating many price-sensitive buyers, higher proportions of loyal consumers allow firms to raise prices—since loyal consumers remain loyal due to brand attachment, acting as a “safety net.” Conversely, below this threshold, with loyal consumers dominating, firms may cut prices to reward loyalty and encourage repeat purchases, as price becomes a less critical factor in the purchasing decision. Firms may adopt more consumer-friendly pricing to strengthen long-term relationships.

4.3. Model H

Under this model, the firm simultaneously offers the trade-in for new and trade-in for cash. In this context, loyal consumers can choose between participating in trade-in for new or retaining old products. It is worth noting that due to the prior assumption that the trade-in for new rebate is greater than or equal to the cash rebate , consumers always obtain higher utility from directly participating in trade-in for new than from exchanging products for cash rebates and then repurchasing new products. Therefore, under Model H, loyal consumers either choose to participate in trade-in for new or retain old products, with their demand for trade-in for new denoted as .

Indifferent consumers, meanwhile, have three options: participating in trade-in for new to obtain trade-in rebates and continue purchasing the firm’s new products, engaging in trade-in for cash to receive cash, or not participating in any trade-in programs. The demands for the trade-in for new and trade-in for cash among indifferent consumers are, respectively:

In this context, the firm’s profits are composed of four distinct components: (i) profits generated from loyal consumers’ participation in trade-in for new, (ii) profits derived from indifferent consumers’ engagement in trade-in for new, (iii) residual value revenue arising from indifferent consumers’ participation in trade-in for cash, and (iv) profits from new consumers’ purchases of products. Consequently, within the framework of Model H, the firm is confronted with the following optimization problem:

Proposition 3. Under Model H, the firm’s optimal retail price, trade-in rebates, and cash rebates are

The firm’s profits are

, the consumer surplus of loyal consumers is , the consumer surplus of indifferent consumers is , the consumer surplus of new consumers is .

Proposition 3 reveals that under Model H, when the rebate gap is high, product pricing and trade-in rebates increase with the proportion of replacement consumers. Specifically, when , we have , , . Conversely, when the rebate gap is small, the impact of replacement consumers’ proportion on retail prices and rebates depends on the proportion of loyal consumers. Only when the proportion of loyal consumers is sufficiently high will retail prices and trade-in rebates rise with the increase in replacement consumers; otherwise, they will decline. Formally, when , if , then ; otherwise, .

When trade-in rebate and cash rebate gaps are large, consumers prefer trade-in for new. As replacement consumers grow, trade-in for new demand rises, so firm raise prices for higher margins while increasing rebates to offset demand loss—forming positive correlations , , . When rebate gaps narrow, enough trade-in demand requires loyal consumers to reach a threshold. Their lower price sensitivity allows firms to raise prices and cash rebates to balance demand, creating a conditional positive link between replacement consumer proportions and pricing/rebate strategies.

Additionally, regarding the impact of loyal consumers on retail prices, this study finds that: (i) When the residual value of recycled used products is low, retail prices decline as the proportion of loyal consumers increases. (ii) Conversely, when the residual value of recycled used products is high, retail prices rise with the proportion of loyal consumers only if the loyal consumer proportion exceeds a specific threshold. Specifically, when , . when , if , ; otherwise, . When the residual value of used products is low, their materials/components offer limited reuse value. Thus, higher loyal consumer proportions drive the firm to cut prices for new sales, offsetting poor recycling profits. When used products have high residual value: if loyal consumers are few, the firm reduces retail prices to promote trade-in for new as this segment grows; once loyal consumers exceed a threshold, their stable base shows low price sensitivity, allowing the firm to raise prices without harming sales.

5. Numerical Examples

In this section, numerical examples will be used to analyze the impacts of the proportions of loyal consumers and replacement consumers on rebate-to-price ratio, firm profits, the choice of trade-in model and consumer surplus. Referencing the research of Tang et al. (2023) [

7] and combining with the actual research background of this paper, the basic parameter values are set as follows:

.

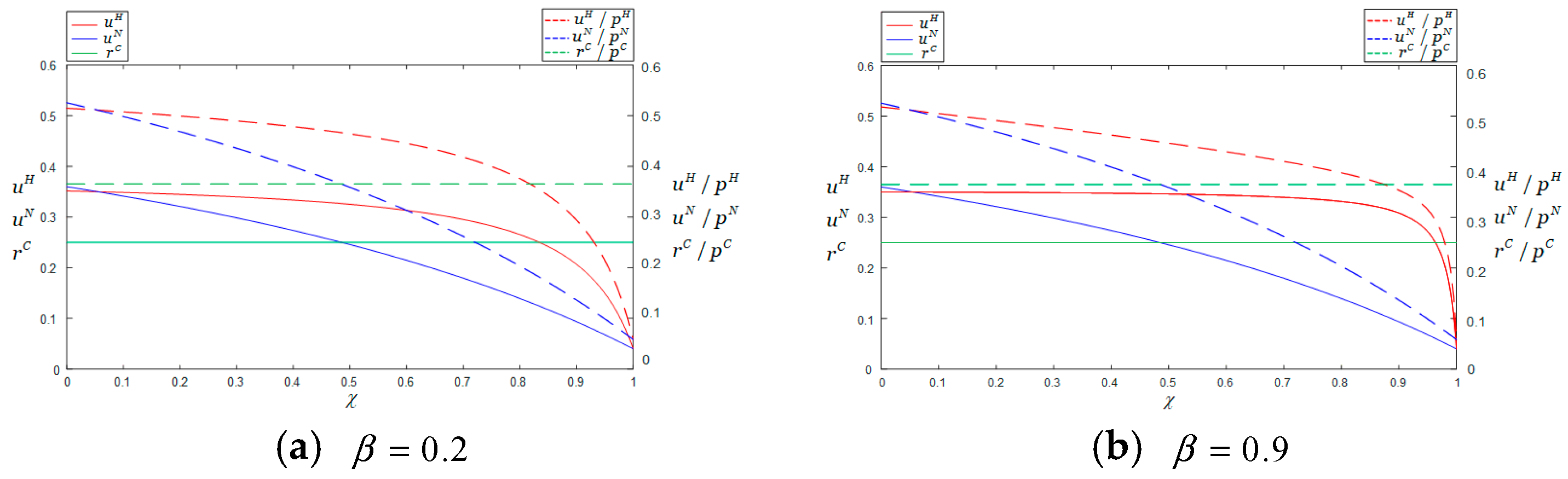

Figure 2 illustrates the impact of the proportion of loyal consumers on trade-in rebates and the rebate-to-price ratio (rebate intensity) under different trade-in models. The horizontal axis represents the proportion of loyal consumers

, the left vertical axis represents the rebate amount, and the right vertical axis represents the ratio of rebate to price. The legend provides explanations for each line in the graph. The red solid line, blue solid line, and green solid line represent the rebate amounts under model H, N, and C, respectively, as the proportion of loyal consumers changes. The red dashed line, blue dashed line, and green dashed line represent the ratio between rebates and pricing under model H, N, and C, respectively, as the proportion of loyal consumers changes. Panel (a) depicts a scenario with a relatively low proportion of replacement consumers. In this context, as the proportion of loyal consumers increases, both the rebate amount and rebate intensity exhibit a declining trend across all three trade-in models. When the proportion of loyal consumers is low, Model N (Trade-in for cash) yields the highest rebate amount and rebate intensity.

This phenomenon can be attributed to the firm’s willingness to offer higher rebates to attract and maintain the loyalty of these consumers. Meanwhile, to incentivize indifferent consumers to opt for the trade-in strategy, the firm must also set relatively high rebates to enhance the strategy’s attractiveness. As the proportion of loyal consumers gradually increases, to maintain their satisfaction and loyalty while simultaneously appealing to indifferent consumers who are less interested in trade-in program or seek more choices, the firm will provide higher rebates and rebate-to-price ratios under Model H than under the other two models. When the proportion of replacement consumers in the market is relatively high (

), there will be significantly substantial trade-in demand. Against this backdrop, firm can meet these demands without offering high trade-in rebates. Therefore, as shown in

Figure 2b, when the proportion of replacement consumers in the market is high, each unit increase in the proportion of loyal consumers leads to a more pronounced decline in the unit trade-in rebate.

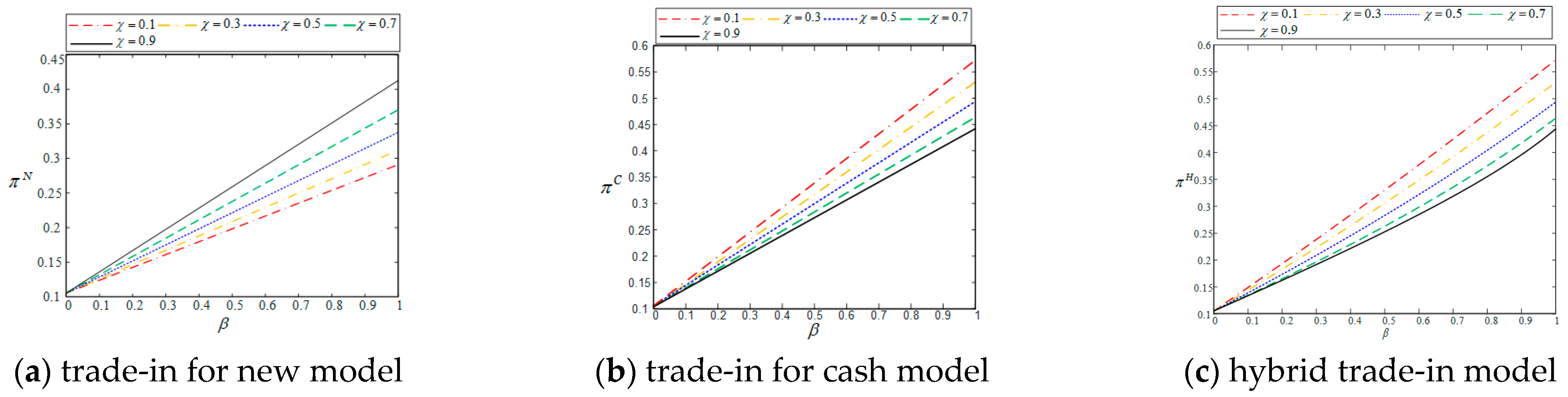

This article has drawn

Figure 3 to illustrate the situation where the firm’s profits change with the proportion of loyal consumers and replacement consumers. The horizontal axis represents the proportion of replacement consumers, the vertical axis represents the firm profit under the Model N, C, and H, respectively. The red line, yellow line, blue line, green line and black line represent the situation where the proportion of loyal consumers is 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 0.9, respectively, and the firm’s profit changes with the variation of replacement consumers.

Figure 3 shows that as the proportion of replacement consumers in the market increases, firm profits also grow. Notably, under Model N, an increase in the proportion of loyal consumers enhances firm profits, while under Models C and H, an increase in the proportion of indifferent consumers boosts firm profits. Due to trade-in incentives, replacement consumers exhibit greater demand for new products compared to new consumers. Moreover, when replacement consumers engage in trade-in program, the firm obtains unit profits from trade-in program that exceed those from new consumers’ purchases of new products by capturing the residual value of the products. Therefore, under all three models, the firm attach greater importance to replacement consumers. In Model N, loyal consumers are more critical to the firm due to their higher demand for trade-in program. In contrast, in Models C and H, indifferent consumers become the focal point for the firm as their ability to participate in both trade-in for new and trade-in for cash model generates greater profits. It is worth noting that although prior research has found that the rebate gap leads to different impacts on pricing for replacement consumers, our analysis reveals that the rebate gap does not affect the trends in how replacement consumers and loyal consumers influence firm profits under Model H. For this reason,

Figure 3 only depicts the scenario where the rebate gap

.

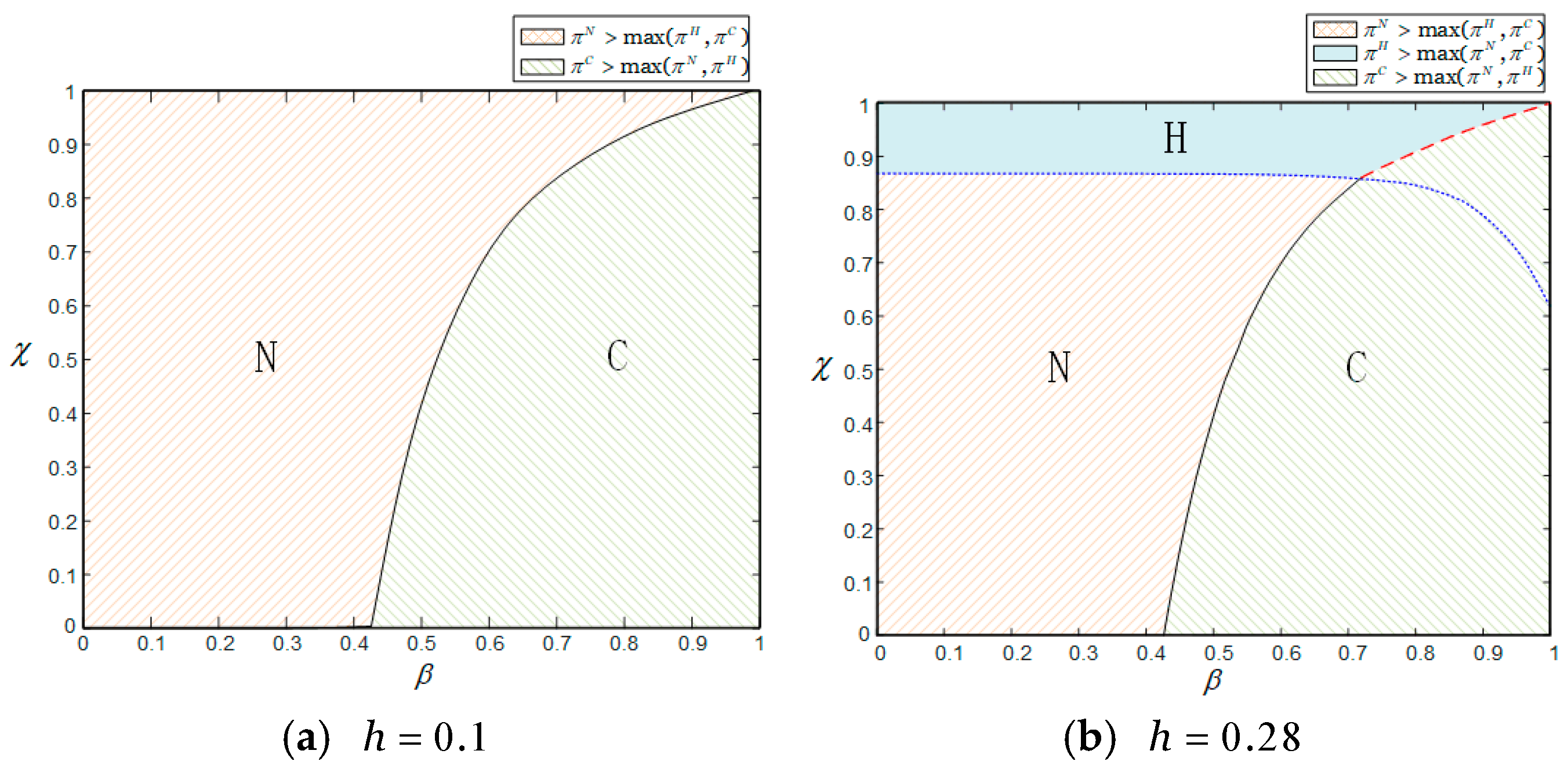

Figure 4 demonstrates the impact of market segmentation on a firm’s selection of trade-in models. The horizontal axis represents the proportion of replacement consumers, while the vertical axis represents the proportion of loyal consumers. Together, these two factors influence the firm’s model selection. The red, green, and blue areas, respectively, indicate the situation where the firm achieves the maximum profit by adopting Model N, C, and H, that is

,

,

. As previously analyzed, the rebate gap

affects pricing. Therefore, this paper will consider scenarios where

and

.

Figure 4 shows that with a small rebate gap, a firm’s model selection mainly depends on the proportions of replacement consumers and loyal consumers in the market. When the proportion of replacement consumers is below a moderate level, adopting Model N is always more beneficial for the firm. However, when the proportion of replacement consumers exceeds a certain threshold, the firm tend to offer Model N to further strengthen the loyalty of consumers if the proportion of loyal consumers is high. In contrast, if the proportion of loyal consumers is low, the firm are more inclined to provide Model C to attract greater participation from indifferent consumers.

However, when the rebate gap is high, the scenario changes. Model C’s optimal region remains consistent with the prior case, but the firm always chooses Model H when the proportion of loyal consumers is extremely high. This is because: with a very high proportion of loyal consumers, the firm must both maintain their loyalty and maximize this advantage to expand the market or increase revenue. Model H offers two options: trade-in for new products and trade-in for cash, balancing the needs of both loyal and indifferent consumers. Loyal consumers prefer trade-in for new due to discounts and upgraded experiences, while indifferent consumers favor trade-in for cash to dispose of used products for returns. Thus, Model H becomes the preferred strategy, enabling the firm to balance diverse needs, maximize residual value gains, and gain flexibility for market expansion.

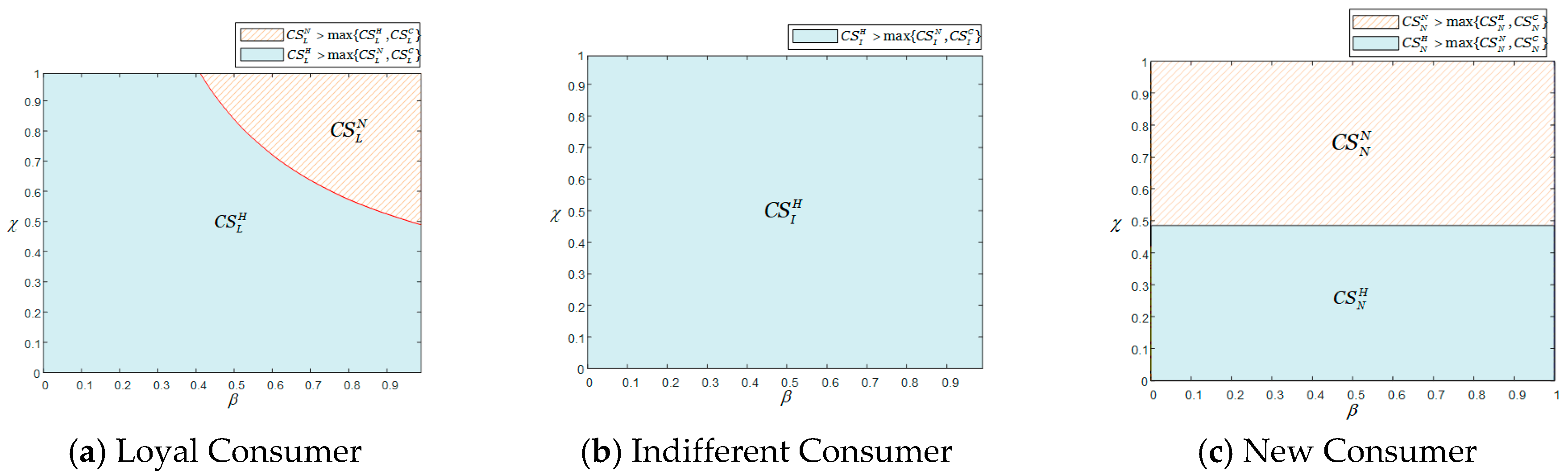

Figure 5 further illustrates the impact of a firm’s trade-in programs on consumers. The horizontal axis represents the proportion of replacement consumers, while the vertical axis represents the proportion of loyal consumers. Together, these two factors influence the consumer surplus. The red, blue area, respectively, indicates the situation where the consumers achieve the maximum surplus by participating in Model N and H, that is

,

. Through numerical examples, we find that the magnitude of the rebate gap does not affect the main conclusions of the consumer model selection diagram; therefore, this paper only plots the scenario where

.

Figure 5a shows that loyal consumers do not choose Model C, and the choice between Model N and Model H depends on the proportions of replacement consumers and loyal consumers in the market. When the proportion of replacement consumers is low, Model H consistently yields higher consumer surplus for loyal consumers. When the proportion of replacement consumers is high, if the proportion of loyal consumers is also high, Model N yields higher consumer surplus for loyal consumers. The reason behind this lies in the generosity of trade-in rebates provided by the firm to consumers. As shown in

Figure 2, when both the proportion of replacement consumers and loyal consumers are high, the firm offers more generous trade-in rebates under Model N than under other models to stimulate product demand, which in turn brings higher consumer surplus to loyal consumers.

Figure 5b indicates that indifferent consumers always prefer Model H. Compared with Model N and Model C, Model H offers greater flexibility: indifferent consumers can either directly exchange for cash rebates to freely allocate cash or engage in trade-in program to purchase new products at lower prices. This satisfies the personalized needs of indifferent consumers, thereby bringing higher consumer surplus to this group.

For new consumers, their purchase strategy of new products only considers the retail price of new products and the size of newcomer coupons. When the proportion of loyal consumers is below the threshold, it will lead to , so new consumers prefer Model H. As the proportion of loyal consumers in the market continues to rise, the retail price of products under Model N will be lower than that under Model H and Model C, at which point new consumers prefer Model N.

6. Conclusions

To explore how market segmentation impacts a firm’s pricing, rebate decisions, and trade-in model selection, this paper considers a market with replacement consumers (further divided into loyal and indifferent types) and new consumers. The study first derives optimal pricing, rebates, and profits under three trade-in models (trade-in for new, cash, and hybrid) to analyze market segmentation’s influence on optimal decisions. Second, it examines how different consumer groups affect the firm’s profits and gains the insight that the firm should pay attention to which consumer groups. Thirdly, it compares profits across models to identify conditions for optimal model adoption. Finally, the study investigates the impact of trade-in models on various consumer groups. The main research findings are as follows:

First, under Model N, increasing the loyal consumer proportion consistently reduces trade-in rebates. Under Model H, however, the impact of the loyal consumer proportion on pricing depends on the thresholds of the used product’s residual value and the loyal consumer proportion. Second, under Model C, the effect of replacement consumer proportion on rebate decisions is contingent on loyal consumer proportion thresholds. Under Model H, this impact hinges on both the rebate gap and the loyal consumer proportion thresholds. By contrast, Model N shows the replacement consumers do not affect rebate decisions. Finally, numerical examples reveal rebate generosity: firms offer the most generous rebates under Model N when loyal consumer proportion is extremely low. As this proportion increases, Model H provides higher rebate intensity. When loyal consumer proportion is extremely high, rebate intensity under Model C exceeds that of the other two models as rebate intensity in Model N and H decreases.

For loyal consumers, the firm’s selection of Model C consistently proves disadvantageous to them. The choice between Model N and Model H depends on the proportions of replacement consumers and loyal consumers in the market. When the proportion of replacement consumers is low, Model H consistently yields higher consumer surplus for loyal consumers. When the proportion of replacement consumers is high, if the proportion of loyal consumers is also high, Model N generates higher consumer surplus for loyal consumers. For indifferent consumers, since Model H offers more personalized choices, they always prefer Model H. Finally, for new consumers, differences in consumer surplus depend solely on pricing differences across models, and rational new consumers tend to choose the model with lower pricing.

This study yields the following managerial insights from analyzing how market segmentation affects firm profits and optimal model selection: In practice, the firm often focuses exclusively on loyal consumers. However, this research reveals that under Model N, the firm should prioritize loyal consumers, while under Model C and H, ordinary consumers (indifferent consumers) should be the primary focus, as they drive higher profits. This paper summarizes the types of consumers firms should focus on and the corresponding measures in

Table 2. Regarding trade-in model selection, for start-ups with low proportions of replacement and loyal consumers, Model N is the optimal strategy. As firms grow and expand, shifting to Model C becomes the most strategic choice. When firms further scale and accumulate a large base of loyal consumers, adopting Model H is recommended. Real-world cases validate these findings. A CIRP report shows that 91% of consumers who bought Apple products in 2023 already owned iPhones, demonstrating Apple’s extremely high brand loyalty and large loyal consumer base. Correspondingly, Apple uses a hybrid trade-in model (Apple Trade In program), enabling consumers to trade in old devices for discounts on new products or convert trade-in values to cash—aligning with the study’s conclusions on Model H’s applicability for firms with high loyal consumer proportions. Furthermore, digital platforms like JD.com and Amazon Renewed play a key role in optimizing trade-in execution. Firms adopting Model C can leverage JD.com’s user profiling to target indifferent consumers (e.g., those with old phones browsing competitors) and send them tailored cash rebate offers. For Firms adopting Model H, integrating with Amazon Renewed’s certified inspection system reduces indifferent consumers’ trust costs (the rationality of the valuation of used items, the safety of cash refunds, etc.) in trade-in for cash, while linking trade-in for new to Amazon’s new product listings enhances loyal consumers’ convenience. This platform collaboration reduces operational costs and expands program reach, thereby broadening the practical applicability of the findings.

Consumer segmentation behavior serves as the central link connecting trade-in strategies to sustainable outcomes, as heterogeneous consumer preferences—whether for brand loyalty, trade-in flexibility, or price sensitivity—directly influence used products and their contribution to circular economy objectives. For loyal consumers, their strong brand attachment and willingness to engage in manufacturer-led programs create a crucial pathway for sustainable used product management. These consumers tend to trust a company’s ability to handle used products responsibly—such as through proper testing, refurbishment, or material recovery—and are more likely to participate in trade-in programs rather than discarding items or selling them through unregulated channels. This not only strengthens brand loyalty but also directs used products into Apple’s formal recycling and refurbishment system—avoiding environ-mental risks associated with unregulated disposal (e.g., chemical leakage from improper dismantling) and enabling the recovery of materials like aluminum and rare earth elements for reuse in new products [

6]. For firms implementing Model N (Trade-in for New), tailoring rebates to loyalty levels—such as linking dis-count amounts to past purchase frequency—further encourages this behavior, guiding more used products into sustainable circulation channels rather than informal markets.

For indifferent consumers, their focus on price and flexibility requires strategies that lower barriers to participation, rather than assuming they will default to unsustainable disposal methods. Such consumers often hesitate to engage in trade-ins if the process is cumbersome or the rewards are inflexible. However, when companies design Model C (Trade-in for Cash) or Model H (Hybrid Trade-in) to align with their preferences, these consumers actively contribute to sustainability. For example, Amazon Renewed’s integration with firms using Model H reduces trust barriers for indifferent consumers in cash rebate transactions (e.g., via certified product valuation) while ensuring that used products enter Amazon’s refurbishment or recycling network—thereby expanding the pool of products available for circular use [

5]. their participation redirects used products away from landfills or informal disposal and into formal circular systems, where residual value is preserved (e.g., through refurbishment for resale) or materials are recovered for reuse.

This paper points out several directions for future research. First, as real-world firms face industry competition and supply chain double markup effects, future studies could explore trade-in model selection in competitive or supply chain contexts. Second, since this paper employs a single-period model that does not address product upgrades or consumer strategic behavior, future research could adopt multi-period frameworks to analyze how product renewal and strategic consumer behavior influence trade-in model choices.