Sustainable Urban Futures: Transportation and Development in Riyadh, Jeddah, and Neom

Abstract

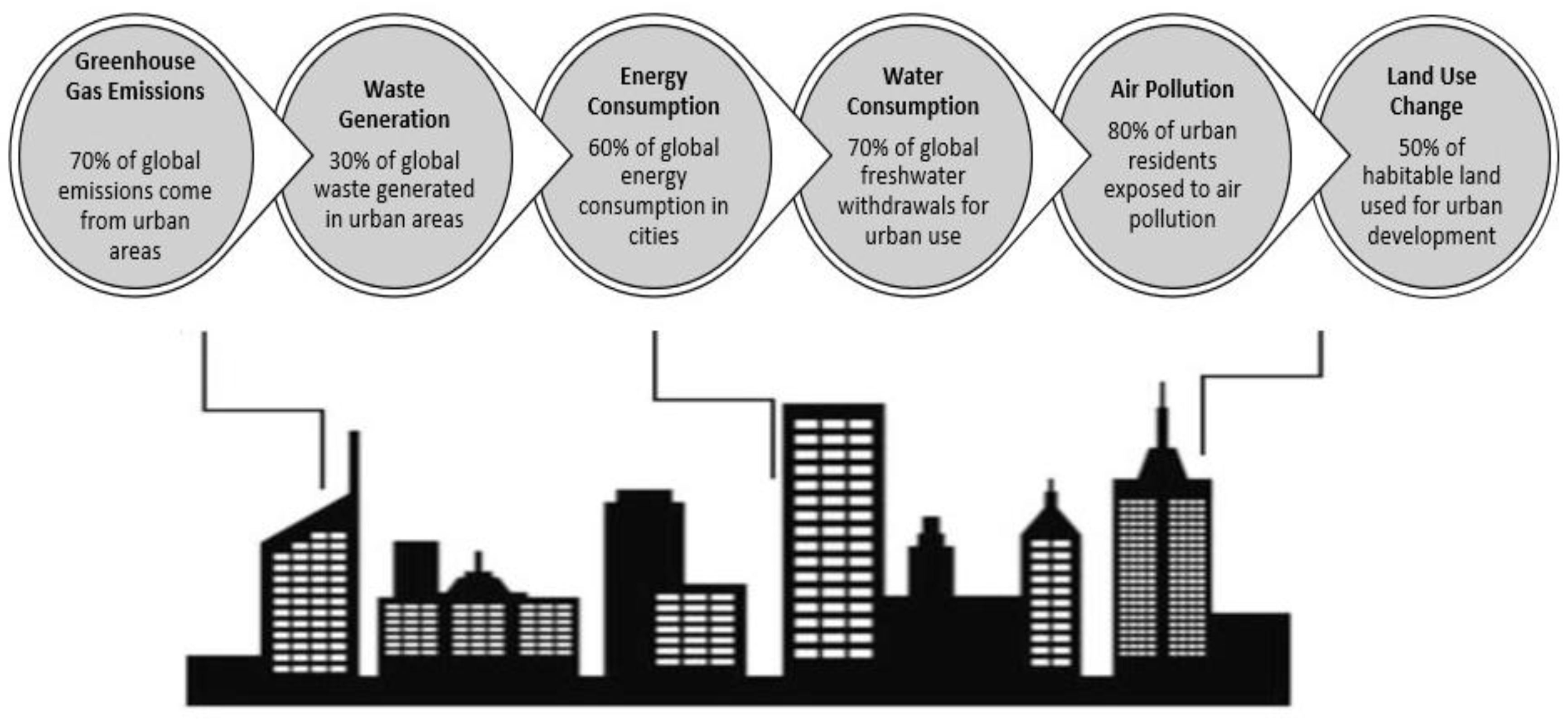

1. Introduction

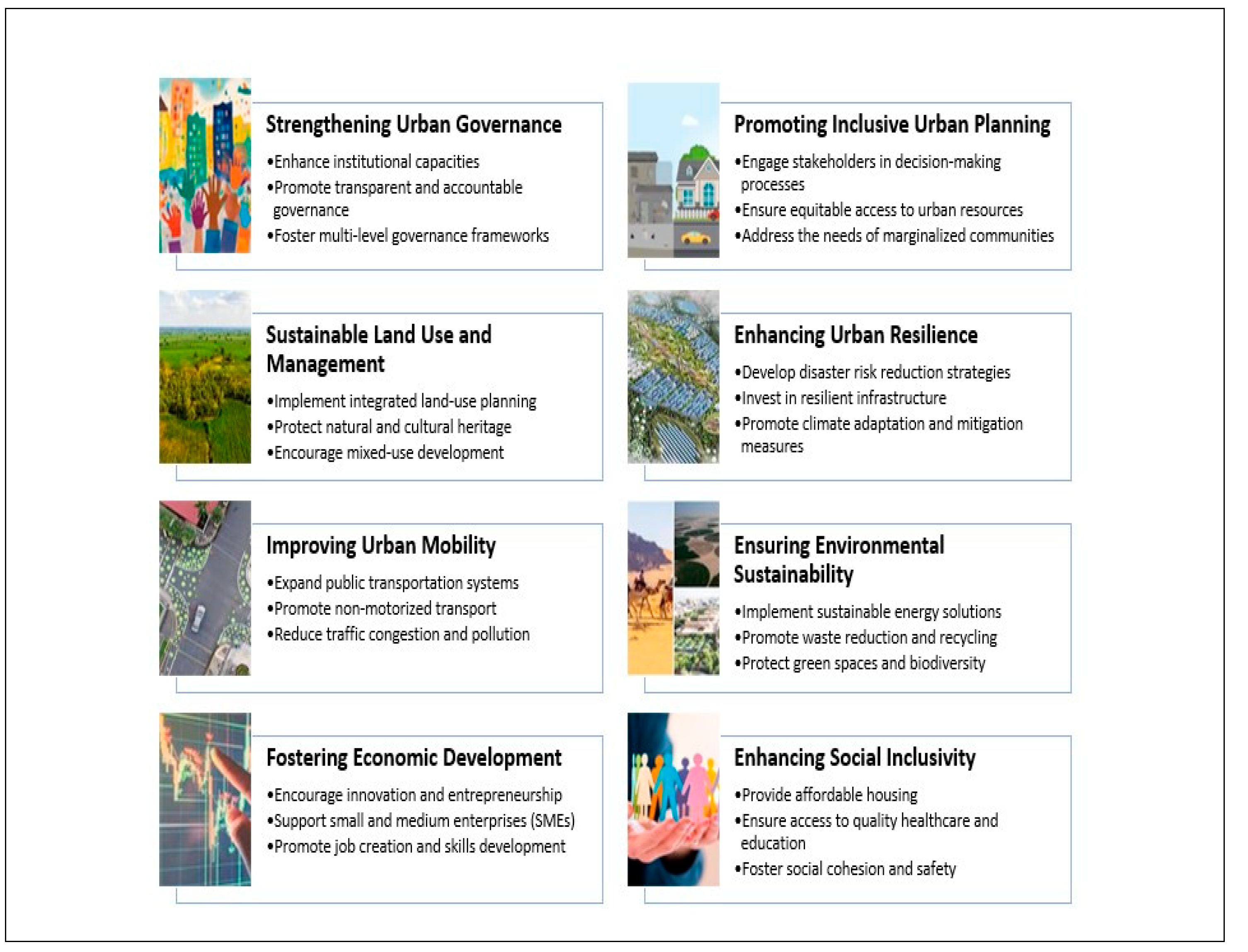

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Areas

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Sampling Strategy

3.5. Research Framework

3.6. Data Analysis

3.7. Ethical Consideration

4. Results

4.1. Environmental Sustainability

4.2. Social Sustainability

4.3. Economic Sustainability

4.4. Governance and Policy Effectiveness

4.5. Transportation and Mobility

4.6. Global Urban Planning Models

5. Discussion

6. Novelty of the Study and Future Research Directions

7. Limitations of the Study

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, T.; Wu, J.; Chen, S. Keeping track of greenhouse gas emission reduction progress and targets in 167 cities worldwide. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 696381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gurney, K.R.; Kılkış, Ş.; Seto, K.C.; Lwasa, S.; Moran, D.; Riahi, K.; Keller, M.; Rayner, P.; Luqman, M. Greenhouse gas emissions from global cities under SSP/RCP scenarios, 1990 to 2100. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 73, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuah, K.G.B.; Abdulai, R.T. Urban land and development management in a challenged developing world: An overview of new reflections. Land 2022, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.K.; Vishnoi, S. Urbanization and sustainable development for inclusiveness using ICTs. Telecommun. Policy 2022, 46, 102311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacyira, A.K. Urbanization: Emerging challenges and a new global urban agenda. Brown J. World Aff. 2016, 23, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Chen, L.; Cheng, J.; Yu, J. Identifying interlinkages between urbanization and Sustainable Development Goals. Geogr. Sustain. 2022, 3, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiliotopoulou, M.; Roseland, M. Urban sustainability: From theory influences to practical agendas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. The Rio declaration on Environment and Development. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Sáez, E.; Lerma-Arce, V.; Coll-Aliaga, E.; Oliver-Villanueva, J.-V. Contribution of green urban areas to the achievement of SDGs. Case study in Valencia (Spain). Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağlar, M.; Gürler, C. Sustainable Development Goals: A cluster analysis of worldwide countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 8593–8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. Urban sustainability assessment: An overview and bibliometric analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A.H. Sustainable Urbanization between Two Ambitious Global Agendas: An Integration Approach. In Urban Agglomeration-Extracting Lessons for Sustainable Development; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Development Report 2022; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kose, M.A.; Ohnsorge, F. Falling Long-Term Growth Prospects: Trends, Expectations, and Policies; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kosovac, A.; Acuto, M.; Jones, T.L. Acknowledging urbanization: A survey of the role of cities in UN frameworks. Glob. Policy 2020, 11, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, H.; Chatterji, T. SDG 11 sustainable cities and communities: SDG 11 and the new urban agenda: Global sustainability frameworks for local action. In Actioning the Global Goals for Local Impact: Towards Sustainability Science, Policy, Education and Practice; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Cugurullo, F. The sustainability of artificial intelligence: An urbanistic viewpoint from the lens of smart and sustainable cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Lin, G.; Huang, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, H. China’s changing city-level greenhouse gas emissions from municipal solid waste treatment and driving factors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180, 106168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, X. Mega urban agglomeration in the transformation era: Evolving theories, research typologies and governance. Cities 2020, 105, 102813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinyanjui, M. National Urban Policy: Tool for Development. In Developing National Urban Policies: Ways Forward to Green and Smart Cities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 51–85. [Google Scholar]

- UN.ESCAP. The Transition of Asian and Pacific Cities to a Sustainable Future: Accelerating Action for Sustainable Urbanization; Environment and Development Division: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Popović, S.G.; Dobričić, M.; Savić, S.V. Challenges of sustainable spatial development in the light of new international perspectives-The case of Montenegro. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citaristi, I. United nations human settlements programme—UN-habitat. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2022; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Alismail, A.A.A.; Alqahtany, A.; Alhamoudi, A.M.; Aljoaib, S.I.; Almazroua, S.M. Framework for Improvement of National Urban Strategy Model of Saudi Arabia by Logical Comparison with Best Practices in the World. J. Sustain. Res. 2025, 7, e250006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, O. Political Economy of Transformation in Saudi Arabia. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alarabi, S.; Alasmari, F. Challenges and opportunities for small cities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A study of expert perceptions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosárová, D. Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030. In Proceedings of the Security Forum, Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 12–13 February 2020; pp. 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Moshashai, D.; Leber, A.M.; Savage, J.D. Saudi Arabia plans for its economic future: Vision 2030, the National Transformation Plan and Saudi fiscal reform. Br. J. Middle East. Stud. 2020, 47, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.M. Planning for urban sustainability: The geography of LEED®–Neighborhood Development™(LEED®–ND™) projects in the United States. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2015, 7, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H.; Bulkeley, H. Governing Climate Change Post-2012: The Role of Global Cities Case-Study: Los Angeles; Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research Working Paper; Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research: Norwich, UK, 2008; Volume 122. [Google Scholar]

- Sandanayake, M.; Bouras, Y.; Vrcelj, Z. Environmental sustainability in infrastructure construction—A review study on Australian higher education program offerings. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brolan, C.E.; Smith, L. No One Left Behind: Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals in Australia; Western Sydney University: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tarek, S.; Ouf, A.S.E.-D. Biophilic smart cities: The role of nature and technology in enhancing urban resilience. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2021, 68, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Mohammed, R.A.; Nashwan, A.J.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Abdalla, A.Q.; Ameen, B.M.M.; Khidhir, R.M. Using thematic analysis in qualitative research. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2025, 6, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, F.O.; Kess-Momoh, A.J.; Ibeh, C.V.; Elufioye, A.E.; Ilojianya, V.I.; Oyeyemi, O.P. Entrepreneurial innovations and trends: A global review: Examining emerging trends, challenges, and opportunities in the field of entrepreneurship, with a focus on how technology and globalization are shaping new business ventures. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingmann, A. Rescripting Riyadh: How the capital of Saudi Arabia employs urban megaprojects as catalysts to enhance the quality of life within the city’s neighborhoods. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2023, 16, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmi, M.; Hegazy, I.; Qurnfulah, E.; Maddah, R.; Ibrahim, H.S. Using sustainable development indicators in developing Saudi cities—Case study: Makkah city. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2021, 16, 1328–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasiri, F.; Dąbrowski, M.; Rocco, R.; Forgaci, C. The Impact of Recent Policies on the Transformation of Local Participatory Urban Planning in Saudi Arabia. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Twynam, C.; Booth, C.; Abbey, S. Boldly Going Where No Sustainability Assessment Tool Has Gone Before. In Proceedings of the International Sustainable Ecological Engineering Design for Society (SEEDS) Conference 2025, Loughborough, UK, 3–5 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, W.-P. Sustainable Strategy Development and Planning. In Solutions For Sustainability Challenges: Technical Sustainability Management and Life Cycle Thinking; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bahreldin, I.; Samir, H.; Maddah, R.; Hammad, H.; Hegazy, I. Leveraging advanced digital technologies for smart city development in Saudi Arabia: Opportunities, challenges, and strategic pathways. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2025, 20, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Towards concentration and decentralization: The evolution of urban spatial structure of Chinese cities, 2001–2016. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 80, 101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhubashi, H.; Alamoudi, M.; Imam, A.; Abed, A.; Hegazy, I. Jeddah strategic approaches to sustainable urban development and vision 2030 alignment. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2024, 19, 1098–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamoudi, M.; Imam, A.; Majrashi, A.; Osra, O.; Hegazy, I. Integrating intelligent and sustainable transportation systems in Jeddah: A multidimensional approach for urban mobility enhancement. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2024, 19, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariram, N.; Mekha, K.; Suganthan, V.; Sudhakar, K. Sustainalism: An integrated socio-economic-environmental model to address sustainable development and sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, M.; Fleischer, T. From ambition to implementation: Institutionalisation as a key challenge for a sustainable mobility transition in Germany. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2023, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, A.; Rashidghalam, M. Assessment of the urban circular economy in Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehbaghi, K.; Trigunarsyah, B.; Balli, A. Sustainable urban development: Strategies to support the Melbourne 2017-2050. Int. J. Strateg. Eng. (IJoSE) 2020, 3, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, U. Copenhagen: Resilience and liveability. Field Actions Sci. Rep. 2018, 18, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Edelenbos, J.; Boonstra, B. A reflexive turn in urban governance. In Reflexive Urban Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- De Geus, T.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Silvestri, G. A balancing act: Radicality and capture in institutionalising reflexive governance for urban sustainability transitions. Urban Transform. 2024, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Jagt, A.P.; Kiss, B.; Hirose, S.; Takahashi, W. Nature-based solutions or debacles? The politics of reflexive governance for sustainable and just cities. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 2, 583833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant ID | Position/Role | City Focus | Years of Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Urban Planning Official | Riyadh | 15 years |

| P2 | Urban Planning Official | Jeddah | 12 years |

| P3 | Urban Transport Planners | NEOM | 5 years |

| P4 | Urban Transport Planners | Riyadh | 11 years |

| P5 | Environmental Specialist | NEOM | 10 years |

| P6 | Environmental Specialist | Riyadh | 13 years |

| P7 | Local Government Official | Riyadh | 11 years |

| P8 | Local Government Official | Jeddah | 8 years |

| P9 | Community Organization Leader | Jeddah | 9 years |

| P10 | Community Organization Leader | Riyadh | 8 years |

| City | Key Environmental Challenges | Stakeholder Perspective | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riyadh | Rely heavily on fossil energy | Strong support for the Green Riyadh initiative | Need for enforcement and long-term monitoring |

| Jeddah | Pollution and lack of green infrastructure | Importance of proactive environmental planning | Environmental quality is closely linked to health and livability |

| NEOM | Large-scale environmental ambitions in early-stage planning | Visionary goals are widely recognized, with ongoing focus on practical implementation and collaboration | Success depends on transparent monitoring and strong stakeholder engagement |

| City | Social Inclusion Issues | Stakeholder Perspective | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riyadh | Opportunities to improve public participation and inclusion | Demands more inclusive decision-making and planning by the community | Strengthening community trust through participation |

| Jeddah | Attention to older neighbourhoods and social cohesion | Promote the value of historical areas and low-income groups’ redevelopment | Encourages socially sensitive and inclusive redevelopment |

| NEOM | New emphasis on the integration of existing communities | Seek clarity on beneficiaries and inclusive development | Highlights the role of equity and social justice in planning |

| City | Economic Focus | Stakeholder View | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riyadh | Mega-projects driving growth and jobs | Strong growth; concerns over equity | Need for inclusive benefits and integration of SEA (Social and Environmental Accountability) |

| Jeddah | Trade, cultural tourism, and infrastructure | Tourism thrives; the limited community gains | Enhance public participation and secure more funding for heritage preservation |

| NEOM | Innovation, tech, and foreign investment | Promising diversification; inclusivity remains unclear | Clarify inclusivity and improve transparency in development plans |

| City | Governance Structure | Stakeholder Perception | Policy Implementation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riyadh | Multi-agency governance with robust inter-agency cooperation and strategic master planning | Seeing as progressive, transformative, and more efficient in governance and development | Managing rapid urban growth and sustainable implementation at scale |

| Jeddah | Mixed governance and changing planning systems and active regional collaboration (e.g., Saudi-Emirati Coordination Council) | Adopted different governance systems | Poor coordination of policy implementation and insufficient stakeholder involvement remain challenges |

| NEOM | Very centralized, visionary leadership and strategic policy coordination | Seen as innovative and strategically controlled under a top-down vision | Balancing ambitious goals and practical implementation and stakeholder involvement |

| City | Key Issues | Stakeholder Views | Future Outlook |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riyadh | Car dependence; limited metro accessibility | Metro is a step forward, but it is not designed for the average commuter | Moderate progress with risk of exclusivity; need to improve accessibility and affordability |

| Jeddah | Lack of integrated public transport; weak pedestrian and cycling infrastructure | The transport system is disorganized and often fails in older and low-income areas | Requires a comprehensive multimodal strategy and improved urban integration |

| NEOM | Ambitious AI-driven, autonomous, carbon-neutral transport vision | The mobility plan is innovative but lacks clarity on practical implementation and equitable access | High innovation potential; implementation and inclusiveness remain to be demonstrated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almatar, K.M. Sustainable Urban Futures: Transportation and Development in Riyadh, Jeddah, and Neom. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210133

Almatar KM. Sustainable Urban Futures: Transportation and Development in Riyadh, Jeddah, and Neom. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210133

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmatar, Khalid Mohammed. 2025. "Sustainable Urban Futures: Transportation and Development in Riyadh, Jeddah, and Neom" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210133

APA StyleAlmatar, K. M. (2025). Sustainable Urban Futures: Transportation and Development in Riyadh, Jeddah, and Neom. Sustainability, 17(22), 10133. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210133