2.5. Strategy Implementation

- A.

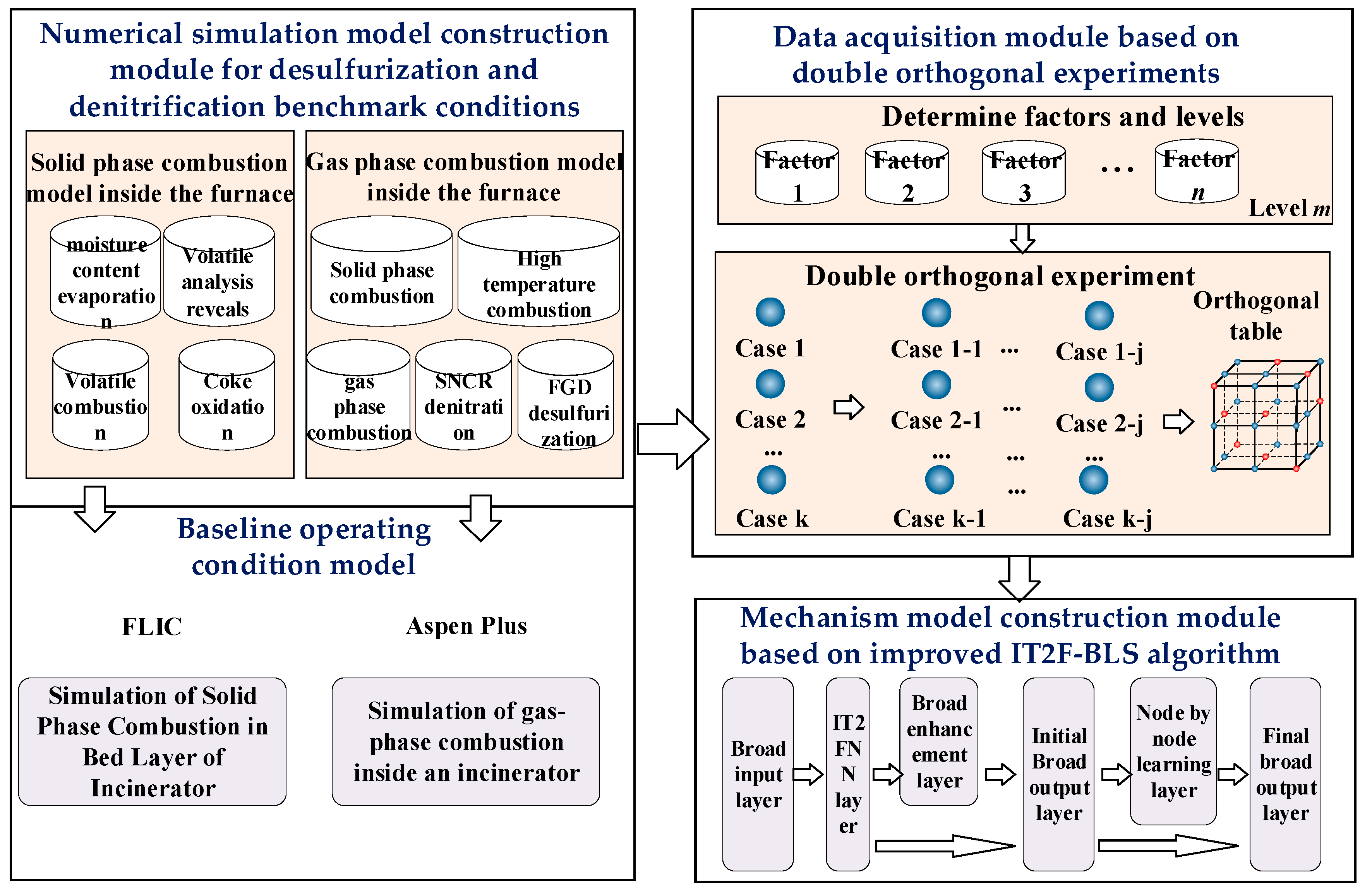

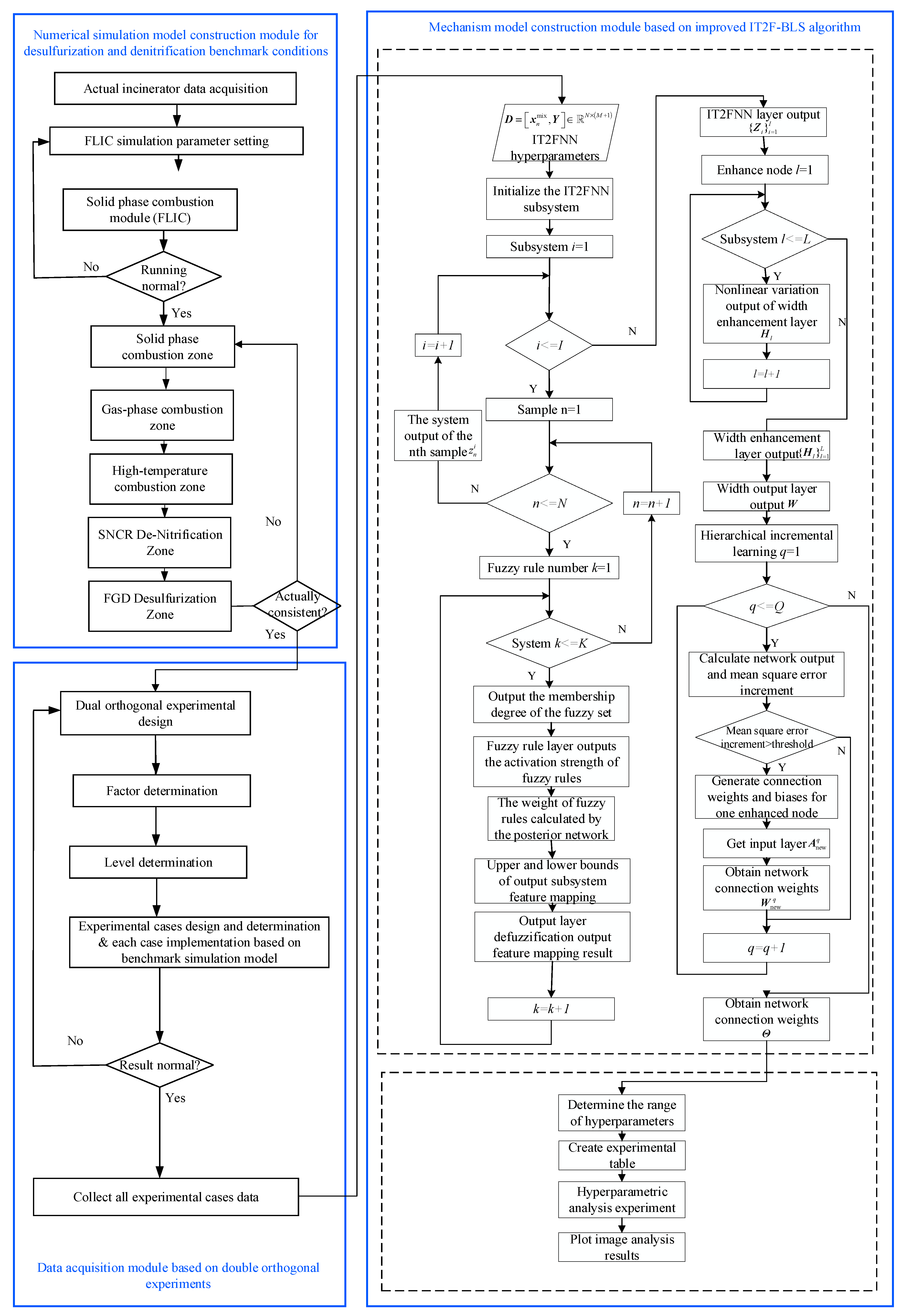

Numerical simulation model construction module for desulfurization and denitrification benchmark conditions

We adopt a multi-software coupling mode to simulate the internal combustion process of the incinerator, which is divided into a solid-phase combustion process on the bed and a gas-phase combustion process above the grate. The solid-phase combustion process on the bed is numerically simulated using FLIC, and the calculation results are imported into Aspen Plus V12.1 as the boundary conditions for the grate bed inlet. Then, a gas-phase combustion simulation is carried out in Aspen Plus V12.1. Considering the uncertainty of MSW composition and the complexity of the combustion process, a steady-state analysis is conducted under the following assumptions: the incinerator is in a stable operating state, the reactions inside the furnace can reach equilibrium, and the temperature and pressure of each reactor are constant without considering pressure loss and heat loss; during the entire incineration process, assuming uniform air distribution, it can fully react with MSW; the main components of MSW are C, H, O, N, S, and Cl, among which C is converted into gas and ash; ash does not participate in the reaction; the gas-phase N element reacts to generate gas compounds; solid N reacts alone to generate NO; the S element generates SO2 and SO3; the Cl element generates HCl. Due to the complex composition of tar, its related reactions are not included in the simulation process.

- (1)

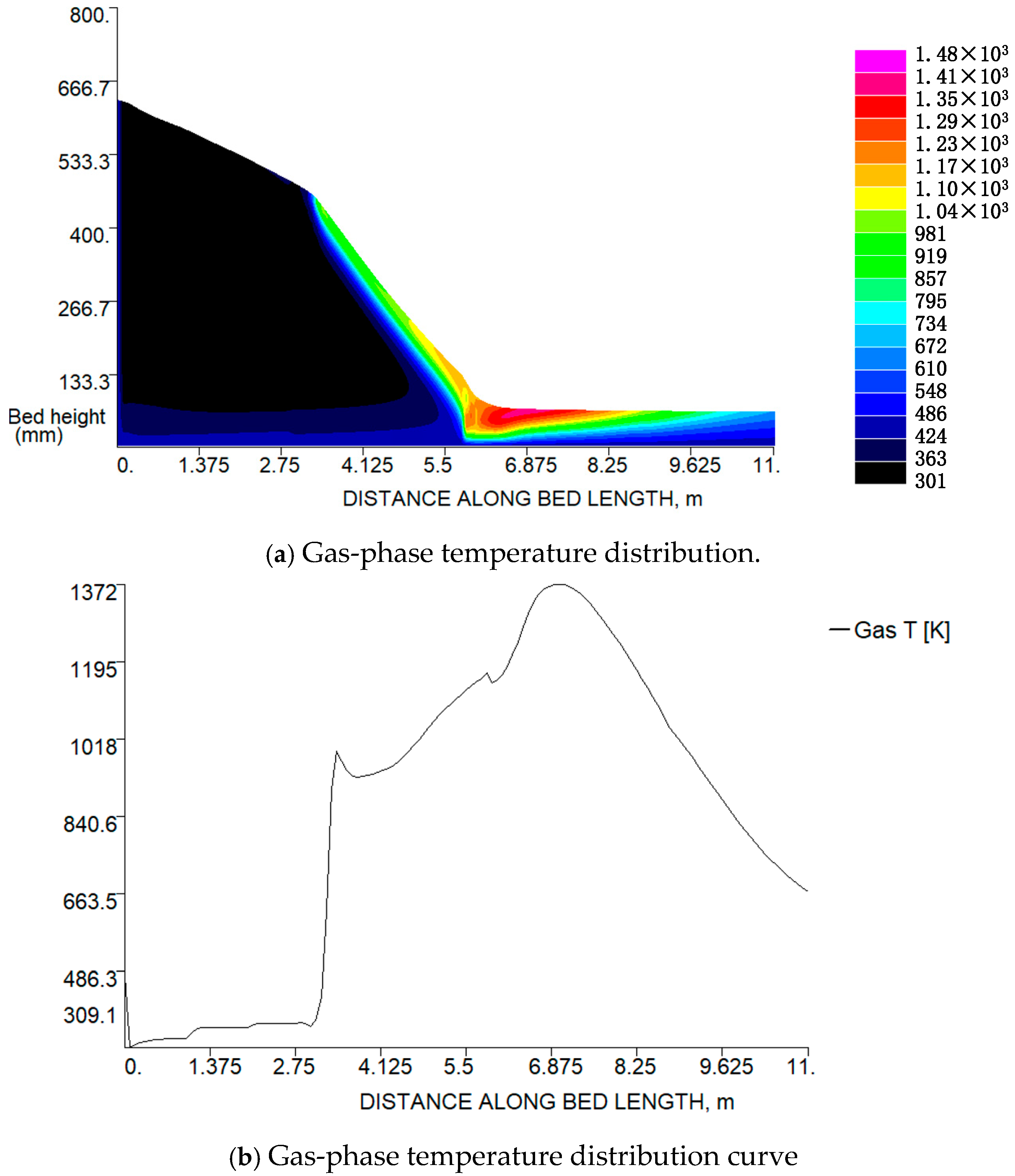

Solid-state combustion simulation based on FLIC

When MSW enters the incinerator from the feeder, it is first subjected to radiation heating on the bed, and water is released as evaporation proceeds. The release rate can be expressed as follows:

where

represents the rate of the water evaporation reaction;

is the surface area of the particles;

represents the heat generated by the evaporation of solid moisture;

is the MSW temperature;

is the convective mass transfer coefficient between a solid and gas;

and

are the water concentrations in the solid and gas phases, respectively;

is the amount of heat absorbed by convective and radiative heat transfer solids, as follows:

where

represents the solid emissivity;

is the Boltzmann radiation constant;

is the gas temperature;

represents the ambient temperature;

is the convective heat transfer coefficient between solid and gas.

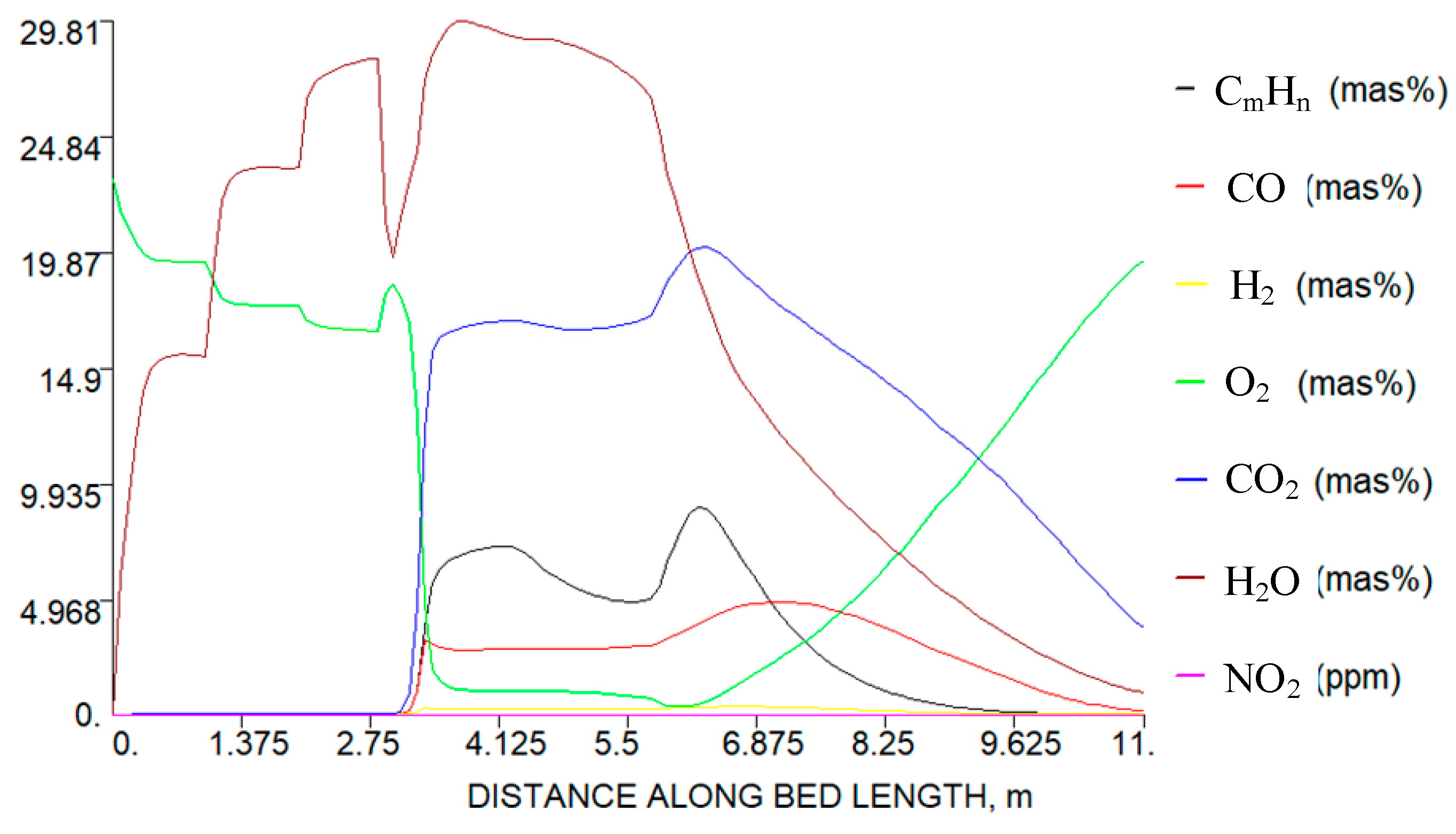

After the evaporation of water, dry MSW begins to release volatile compounds at high temperatures, mainly composed of trace compounds such as hydrocarbons (CmHn), CO, CO

2, H

2, O

2, etc., as follows:

Using a relatively simple and accurate one-step global reaction model [

24], the release rate of volatile matter is proportional to the remaining volatile matter and temperature, as shown in the following equation:

where

represents the reaction rate of volatile matter;

is the final yield of volatile matter;

is the release amount of volatile matter at time;

is the universal gas constant;

represents the pre-exponential factor of volatile combustion rate;

is the activation energy.

The gas released by high-temperature MSW in the furnace mixes with the surrounding air and rapidly burns. Simplified gaseous combustible volatiles include CmHn and CO, and their combustion reactions are as follows:

The combustion rate or kinetic rate related to temperature is provided by the following equations:

The combustion of combustible volatile gases is not only limited by reaction kinetics but also by the mixing rate of combustible gases with surrounding air. Assuming that the mixing rate inside the bed is proportional to the energy loss through the bed, the mixing rate can be expressed as follows:

where

is an empirical constant,

is the mass fraction of gaseous reactants,

is the gas mass diffusion coefficient,

is the air velocity,

is the gas density,

is the particle diameter,

is the bed void ratio, and

is the stoichiometric coefficient in the reaction.

The actual combustion reaction rate of volatile matter is taken as the minimum value of the temperature-related kinetic rate

and oxygen mixing rate

, as shown in the following equation:

During volatilization analysis, MSW particles will form coke, and the main products of further gasification are CO and CO

2. The reaction equation can be expressed as follows:

where the range of coefficient

is 0.5–1, which can be determined according to Arthur’s law.

The rate of coke combustion can be expressed as follows:

where

is the reaction rate of coke combustion;

is the partial pressure of oxygen;

and

are the rate constants caused by chemical kinetics and diffusion, respectively.

At the initial stage of model construction, a one-step reaction model with a simplified form (e.g., volatile release rate is exponentially related to remaining volatiles and temperature) is preferred to quickly validate the feasibility of the coupling framework between FLIC and Aspen Plus. This simplified treatment aims to reduce the initial complexity of the multi-software coupling and focuses on the construction of the full life cycle modeling framework. Subsequently, we will refer to the subdivision method of pyrolysis behavior of solid waste components and the idea of kinetic parameter calibration in the study of Dong et al. [

25] to improve the accuracy of solid-phase combustion simulation.

- (2)

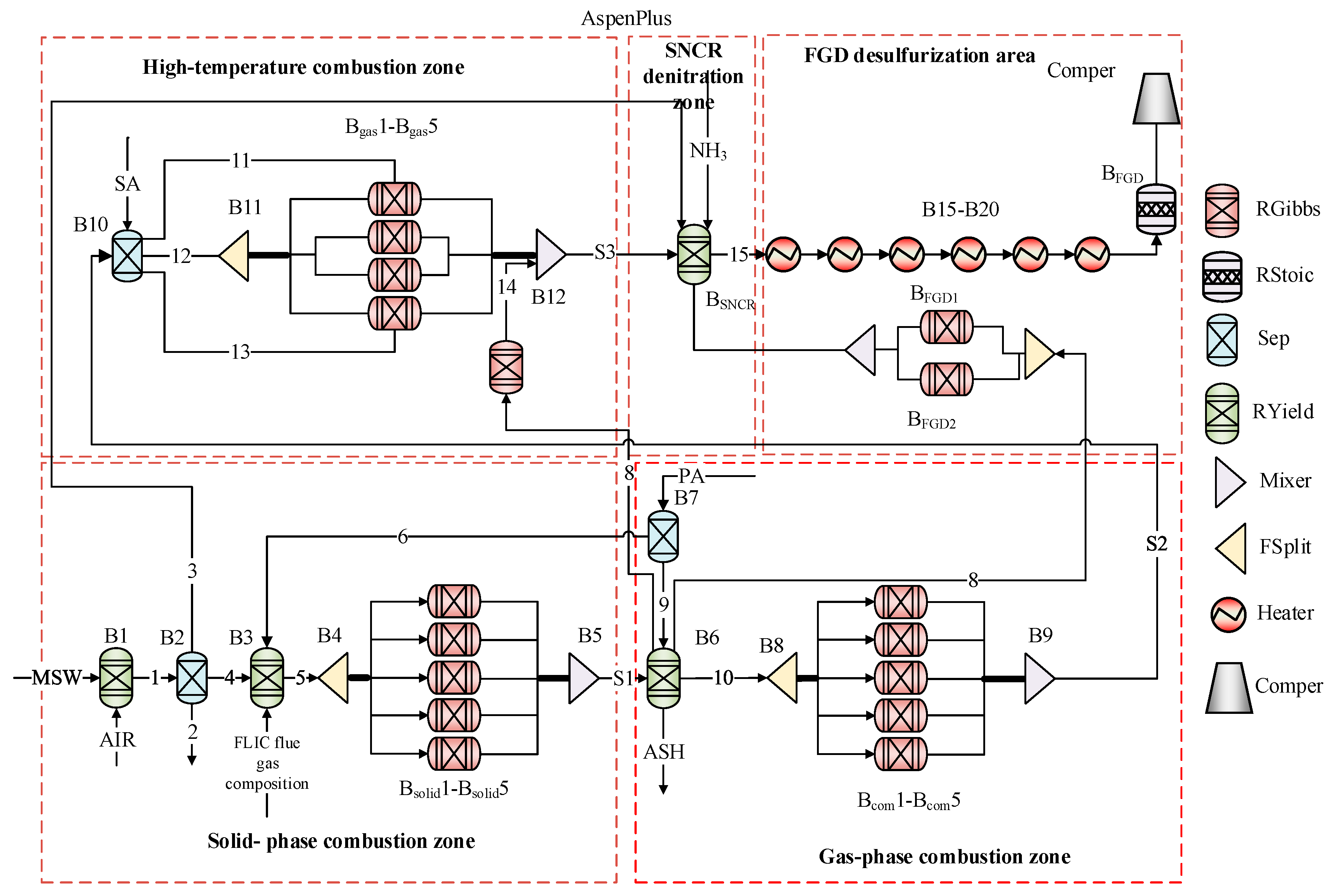

Gas phase combustion simulation based on Aspen Plus

The overall numerical simulation model of gas-phase combustion based on Aspen Plus is shown in

Figure 4.

In

Figure 4, the numerical simulation model comprises a solid-phase combustion zone, a gas-phase combustion zone, a high-temperature combustion zone, an SNCR desulfurization zone, and an FGD desulfurization zone. Its coupling with FLIC is demonstrated by obtaining the solid-phase combustion flue gas components from FLIC and inputting them into the B3 module. The output of the B3 module is then mixed with primary air and fed into subsequent modules for further experimentation. The functions of each module are outlined in

Table 3.

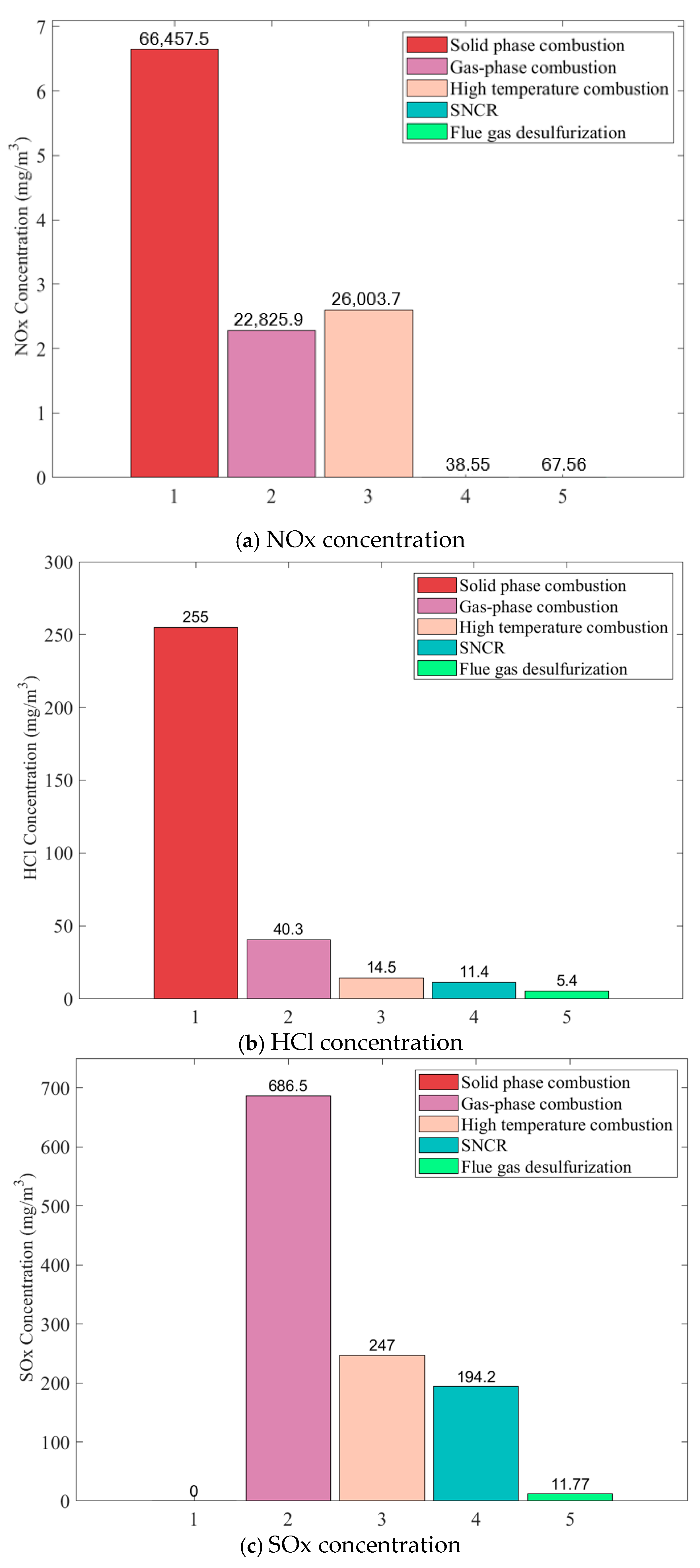

- (1)

Solid phase combustion zone: In the numerical simulation of this zone, MSW first enters the drying module B1, where moisture is removed through B2. The dried MSW then enters B3, where it is mixed with primary air. After passing through splitter B4, the mixture flows into reactors Bsolid1-Bsolid5 for solid-phase combustion simulation. These reactors simulate the generation of conventional gas products such as NO2, NO, HCN, NH3, SO2, SO3, HCl, and others. The generation ratio of HCN and NH3 is set to 9. Finally, the products from all modules flow into mixer B5, where the relevant reactions occur:

- (2)

Gas-phase combustion zone: This zone simulates the reactions that occur as MSW enters the grate and heats up to 500 °C. First, the products from the solid-phase combustion zone flow into separator B6, where solid slag such as ASH is discharged. Next, char-N is directed into reactor Bgas5, while the remaining gas is mixed with primary air and flows into diverter B8. After diversion, the gas enters reactors Bcom1-Bcom5 to simulate gas-phase combustion reactions. Finally, the products from all modules are mixed after entering mixer B9. The relevant reactions are as follows:

- (3)

High-temperature combustion zone: This zone simulates the process when the furnace temperature ranges between 500 °C and 800 °C. Initially, the gas-phase combustion products and secondary air flow into separator B10, where they are mixed and separated, with HCN and NH3 being isolated from other conventional gases. The separated NH3 and HCN then flow into reactors Bgas1 and Bgas4. The remaining gases are split by splitter B11 and directed into reactors Bgas1-Bgas4 for high-temperature combustion simulation. The main reactions are as follows:

In addition to NO

2 being reduced to NO at temperatures above 600 °C, this zone also contains some reducing gases that reduce NOx, such as CO’s reduction reaction with NO [

26]:

In addition, Char-N, which is separated from the gas-phase combustion zone and flows into Bgas5, undergoes the following decomposition reaction:

Finally, all products flow into mixer B12 together.

This module is the location with the highest NOx concentration in the whole MSWI process because, at this temperature, many intermediate products like HCN and NH3 are decomposed into NOx. Additionally, fixed nitrogen undergoes conversion reactions. In this zone, sulfur (S) appears in the form of SO2 and SO3, while chlorine (Cl) is present as HCl and Cl2.

- (4)

SNCR denitration zone: This zone simulates the SNCR denitrification process. First, the products from the high-temperature combustion zone enter the BSNCR yield reactor, where water and NH3 are also introduced. The main reactions are as follows:

Furthermore, the gas processed by the SNCR enters reactors B15-B20 to simulate the cooling effect of the three-stage superheater and three-stage economizer, before finally flowing into the subsequent modules.

- (5)

FGD desulfurization zone: This zone simulates the FGD desulfurization process. The purified gas from the SNCR process flows into BFGD1 and BFGD2, where lime is injected for the desulfurization reaction. The main reactions are as follows:

The generation and consumption of HCN, NH

3 and other intermediates in the waste incineration process have significant time-dependence (e.g., the HCN release rate in the solid-phase combustion stage varies with the time of grate advancement, and the reaction rate of NH

3 with NO

x in the SNCR region fluctuates with the residence time), and the existing models do not adequately quantify this dynamic property, which may lead to the prediction bias of pollutant concentrations. The “generalized solution method of spatio-temporally dependent source terms” proposed by Ding et al. [

27] provides an important idea to deal with such problems, which is especially suitable for the mathematical description of unsteady reaction processes, and we will focus on solving these problems in the future.

- B.

Data acquisition module based on double orthogonal experiments

This article adopts a double orthogonal experimental design to obtain multiple sets of manipulated and non-manipulated variable values under various operating conditions. The process is as follows:

- (1)

We determine the experimental factor and its level , and then we obtain the orthogonal experimental table . This provides experimental cases that can be obtained.

- (2)

Based on the cases obtained from the first orthogonal experiment, the experimental factor and its level are re-determined to obtain orthogonal experimental tables .

- (3)

The experimental case can be obtained, with a total of operating conditions.

The

experimental cases obtained above are sequentially input into the multi-software coupled desulfurization and denitrification numerical simulation model

, which can be expressed as follows:

where

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

represent the feed rate amount, grate speed, primary air volume in the drying section, moisture content, particle size, particle mixing coefficient, secondary air volume, secondary air temperature, urea feeding flow rate, and lime feeding amount, respectively;

represents the coupled numerical simulation model constructed in the previous text;

represents the concentration of relevant pollutants for coupling numerical simulation models.

At this point, virtual simulation mechanism data of desulfurization and denitrification-related pollutants under the conditions have been obtained.

- C.

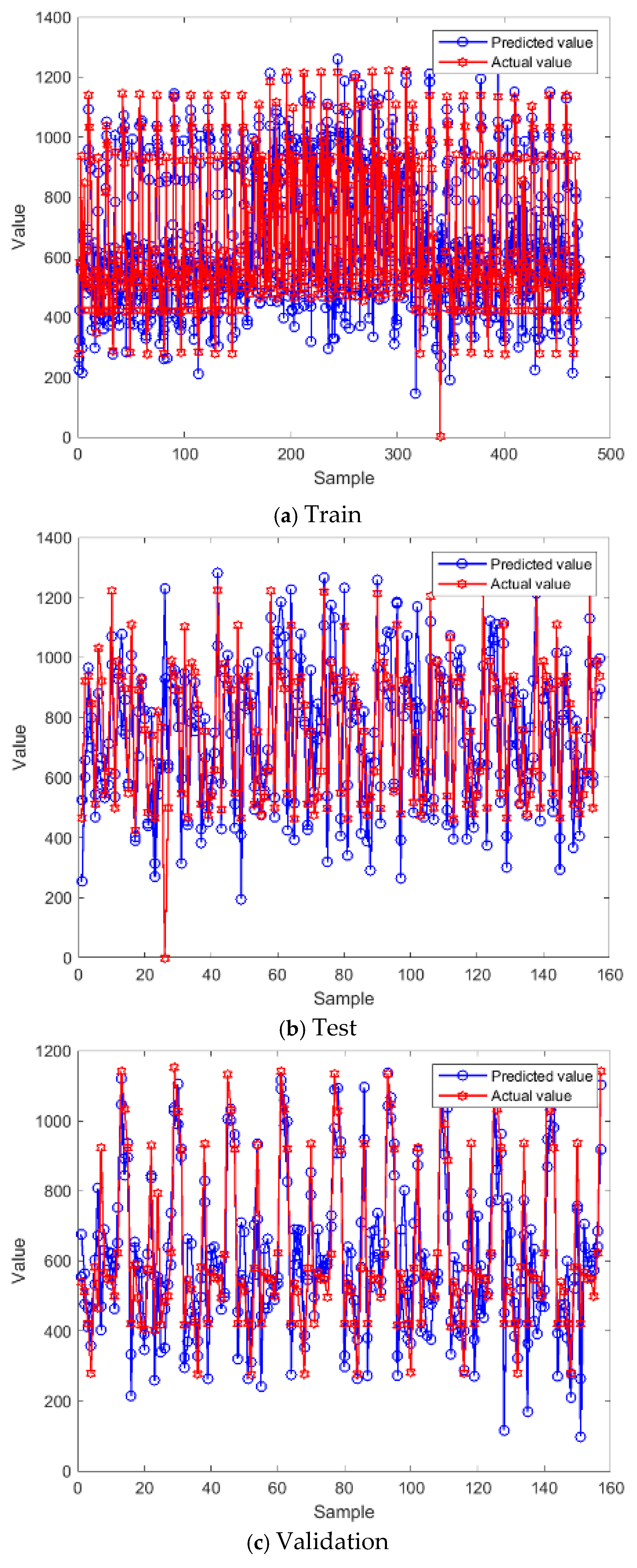

Mechanism model construction module based on an improved IT2FBLS algorithm

The improved IT2FBLS network consists of two main phases: the training phase and the hierarchical incremental learning phase. The model training phase includes a width input layer, an IT2FNN layer, a width enhancement layer, and an initial width output layer. The hierarchical incremental learning phase consists of a node-by-node learning layer and a final width output layer.

In the broad input layer, it does not transform the input data, which can be represented as follows:

where

represents the number of samples, and

represents the number of features of the input data.

The IT2FNN layer contains

subsystems. By taking the

-th sample of the

-th subsystem as an example, the details are shown as follows. In the antecedent network, the input layer passes the network input to the membership function layer, with a weight of 1 and a node count of

. The membership function layer fuzzifies the input variables and represents them in interval form, with a weight of 1 and several nodes

(representing the number of fuzzy rules), where each node represents an interval type-2 membership function. The input of this layer is the output of the input layer, which is the membership degree of the fuzzy set. After using Gaussian membership functions with uncertain mean to calculate the membership degree of a fuzzy set [

28], by taking the membership degree of the rule

corresponding to the

-th input as an example, the lower and upper bounds are calculated as follows:

where

represents

input variables;

and

, respectively, represent the lower and upper bounds of the uncertainty center of the

-th membership function corresponding to the

-th input variable;

represents the width of the

-th membership function corresponding to the

-th input variable.

The fuzzy rule layer constructs fuzzy rules and implements fuzzy inference calculation, with a weight of 1 and a node number of

. The input of this layer is the output of the membership function layer, and the output is the activation strength of the fuzzy rules. Taking the

-th fuzzy rule as an example, the calculation is as follows:

where

and

represent the lower and upper bounds of the activation strength of rule

, respectively.

The activation strength and consequent parameters of the descent layer combination rule complete the descent operation, and the weight is the weight of the consequent interval with 2 nodes. The input of this layer is the output of the fuzzy rule layer, which outputs the lower and upper bounds of the subsystem feature mapping. The calculation is as follows:

where

represents the weight of the consequent interval.

The output layer is de-fuzzified to obtain the model output, with weights of the lower-bound proportional value

and the upper-bound proportional value

. The input of this layer is the output of the descent layer, and the output is the feature mapping result. The calculation is as follows:

In the consequent network, the input layer passes the network output to the subsequent network. The hidden layer contains

node and outputs the weights of fuzzy rules in the antecedent network, which can be expressed as follows:

where

represents the output of the

-th node, which is the output weight of the

-th rule in the antecedent network;

represents the bias of the

-th node;

represents the weight from the

-th input to the

-th node;

represents the

-th input. Furthermore, the feature mapping output of the subsystem can be represented as follows:

where

. Finally, the output of the IT2FNN layer can be represented as follows:

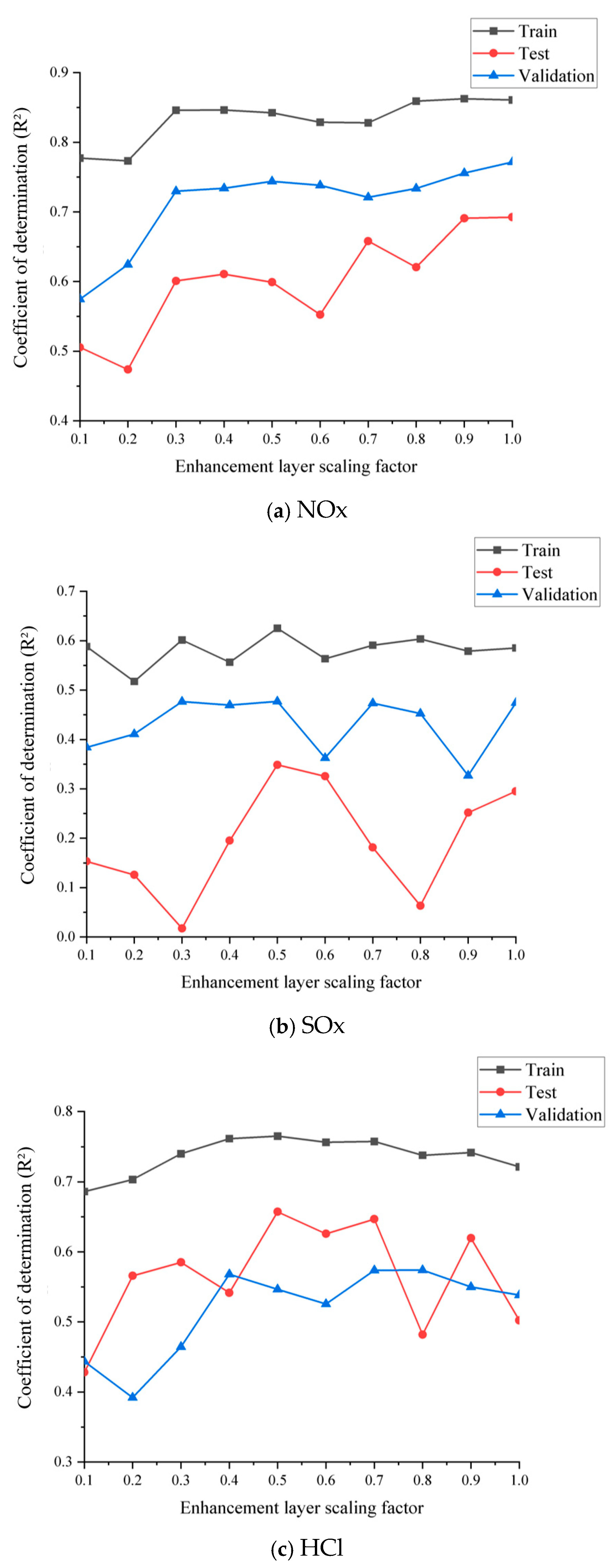

The broad enhancement layer contains

number of enhanced nodes, and the output of the IT2FNN layer is nonlinearly transformed using the

function, which can be expressed as follows:

where

and

represent the randomly generated connection weights and biases of the

i-th enhancement node in the IT2FNN layer and enhancement layer, respectively.

The initial broad output layer contains 3 nodes, and its output can be represented as follows:

where

and

represent the connection weights between the IT2FNN layer and the enhancement layer and the output layer, respectively;

represents the network output during the training phase;

represents the network input;

represents the network connection weights. According to Equation (51), we can obtain the following:

where

represents the generalized inverse matrix, and

represents the true value of the model.

Due to the difficulty in directly obtaining

practical problems,

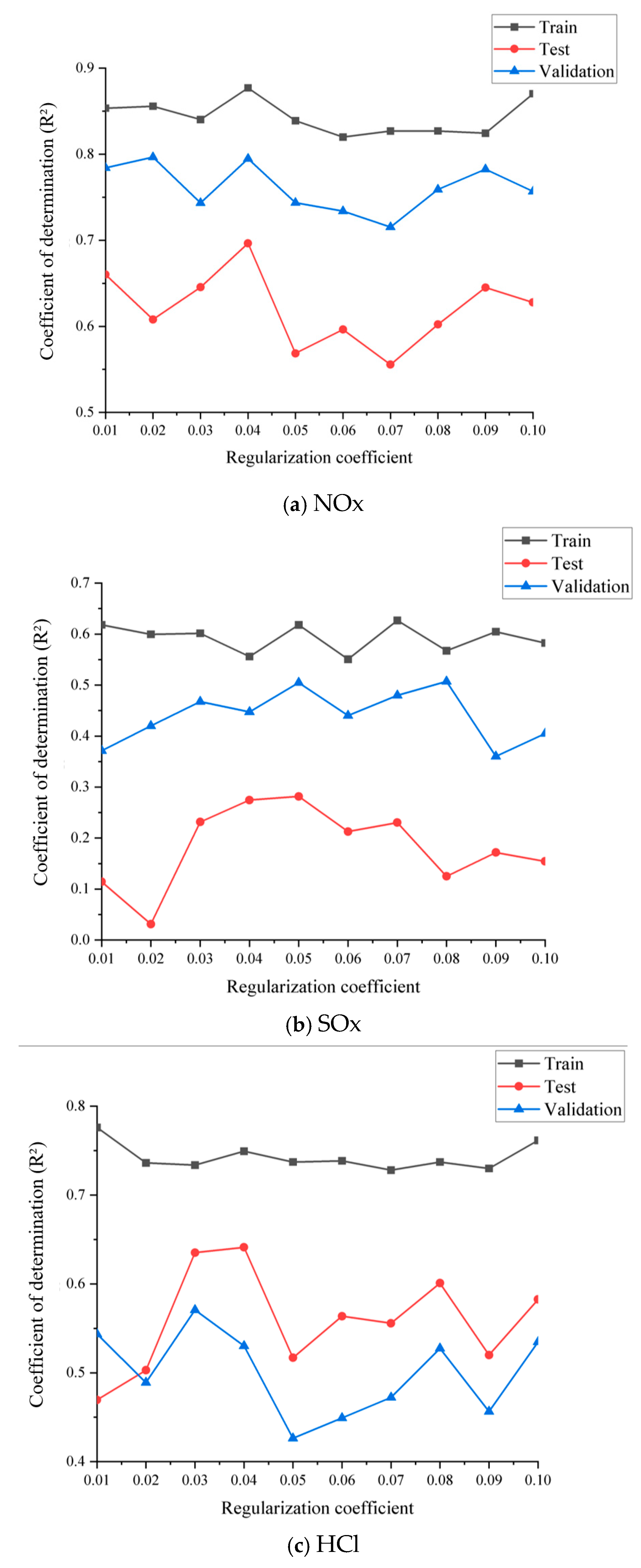

regularization is used to transform them into an optimization problem, whose expression is the following:

where

represents the regularization coefficient, and

. Furthermore, by using ridge regression estimation, the Moore–Penrose inverse matrix

is obtained as follows:

where

represents the identity matrix. Finally, the calculation

is as follows:

- (2)

Hierarchical incremental learning phase

For the node-by-node learning layer, based on the feature nodes and enhancement nodes in the training phase, the layer is divided for hierarchical incremental learning ( represents the number of network outputs). By taking the -th output as an example, the node-by-node learning process is described as follows.

First, we calculate the mean square error (MSE) between the

-th output and the true value, expressed as follows:

where

represents the mean square error of the

-th output after adding

enhancement nodes;

and

represent the output and truth of the

-th sample model, respectively.

Then, we calculate the MSE increment before and after adding the enhancement node to the

-th output, which is expressed as follows:

If

does not meet the set threshold

, the incremental learning process is performed on the

-th output enhancement node of the network. The augmentation matrix is updated as follows:

According to Equation (52), the network weight after adding enhanced nodes can be expressed as follows:

The pseudo-inverse matrix of the input matrix after adding enhanced nodes can be expressed as follows:

where

;

where

.

Therefore, the weight matrix of the enhanced node after adding the

-th output can be expressed as follows:

For the final broad output layer, by repeating the above process until all outputs of

satisfy

, the weights of the network are obtained. The expression is as follows:

where

represents the hierarchical incremental learning process.

Finally, the output of the improved IT2FBLS network can be represented as follows:

The existing feature nodes and enhancement nodes during the training process are shared in each layer of hierarchical incremental learning, and the subsequent layer of incremental learning is based on the total number of nodes trained in the previous layer. Therefore, the number of enhancement nodes for the improved IT2FBLS network after training is denoted as .