Work Engagement, Job Crafting, and Their Effects on Green Work Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose

1.2. Contribution

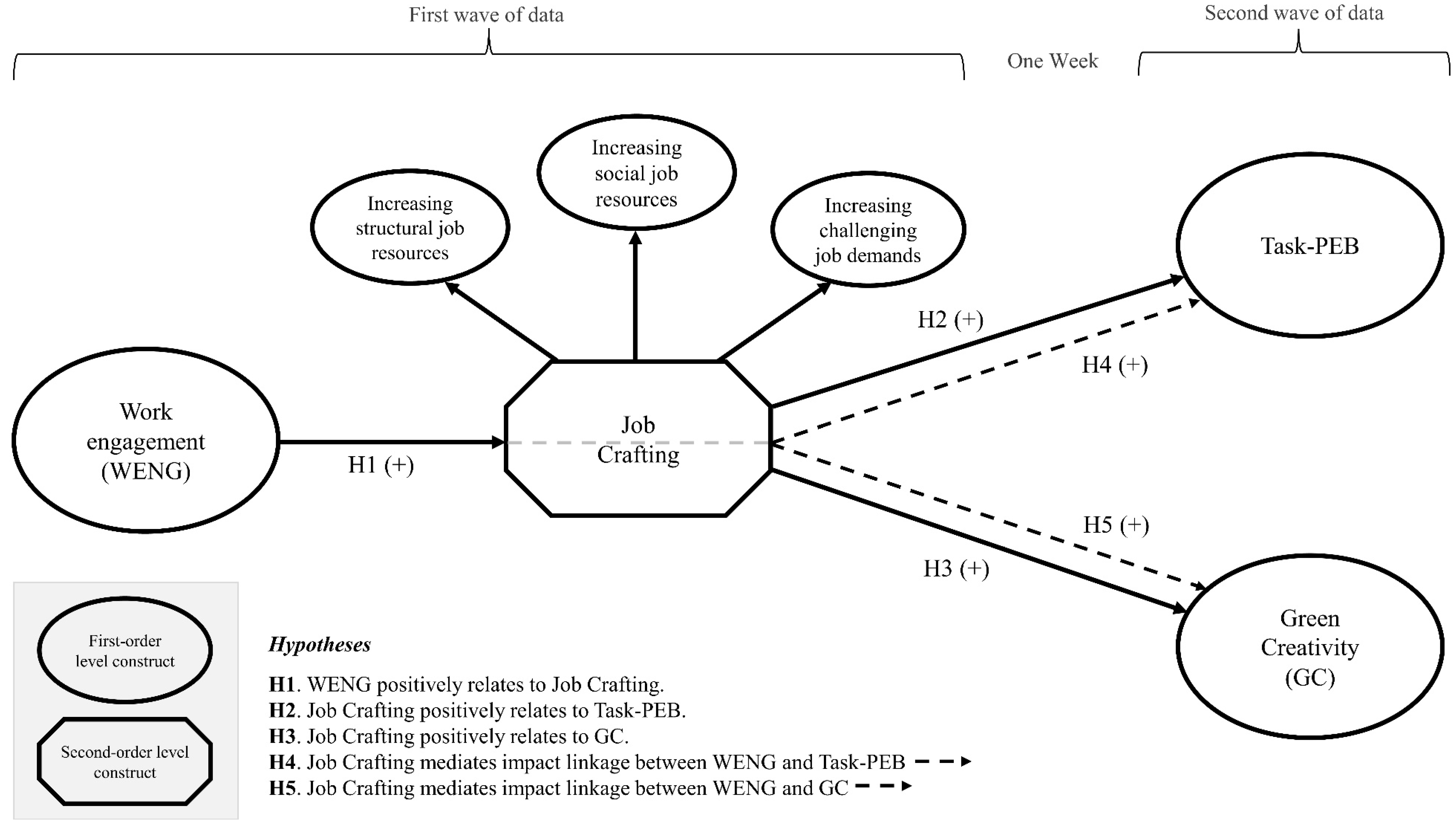

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Composite Analysis

4.2. Configuration and Measurement of Compounds

4.3. The Marker Variable

4.4. Test of Research Hypotheses

4.5. Assessment of the Model’s Predictive Strength

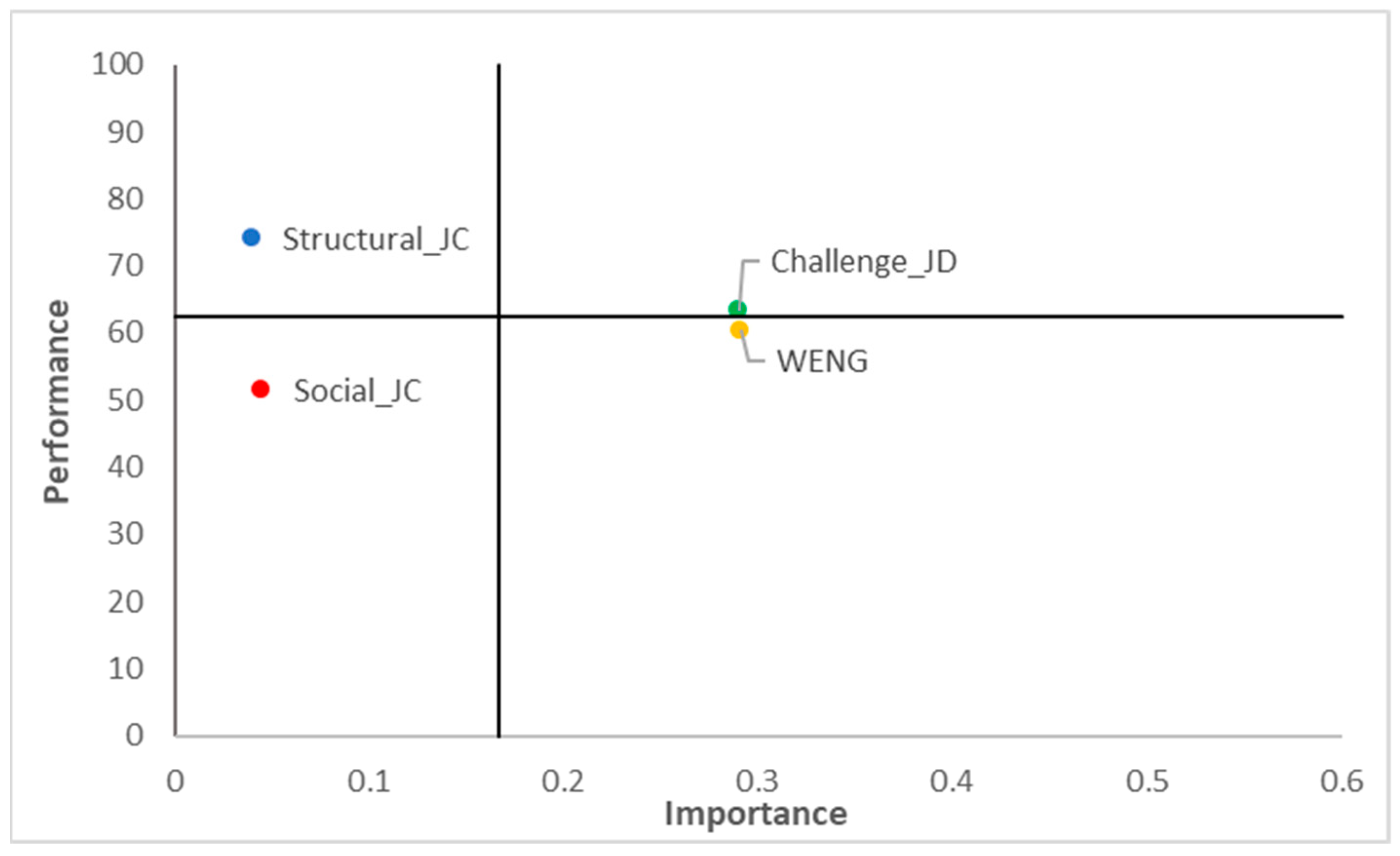

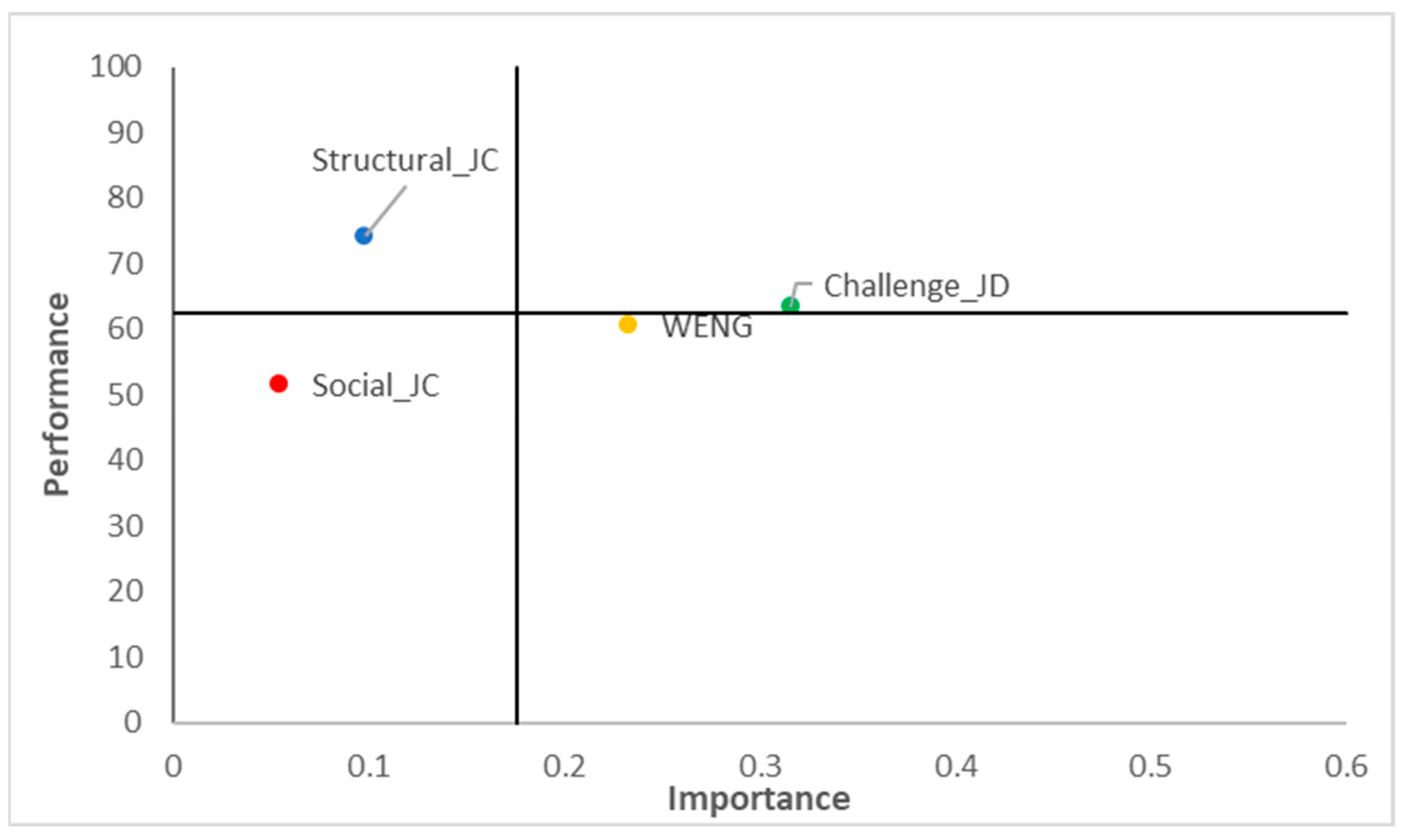

4.6. Importance–Performance Analysis

4.7. Robustness Model Check: Endogeneity

5. Discussion

5.1. General Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WENG | Work Engagement |

| TPEB | Task-Related Pro-Environmental Behavior |

| CCEs | Customer-Contact Employees |

| JC | Job Crafting |

| ES | Environmental Sustainability |

| JD-R | Job Demands–Resources |

| JRs | Job Resources |

| JDs | Job Demands |

| CMV | Common Method Variance |

| HOC | Higher-Order Construct |

| CCA | Confirmatory Composite Analysis |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait |

| VIFs | Variance Inflation Factors |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| IPMA | Importance–Performance Map |

Appendix A

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | ||||||||

| 2. Organizational tenure | 0.119 | - | |||||||

| 3. Work engagement | −0.056 | 0.206 * | - | ||||||

| 4. Structural JRs | 0.017 | 0.105 | 0.636 * | - | |||||

| 5. Social JRs | 0.101 | −0.047 | 0.324 * | 0.487 * | - | ||||

| 6. Challenging JDs | −0.010 | 0.105 | 0.654 * | 0.727 * | 0.515 * | - | |||

| 7. Task-related pro-environmental behavior | 0.136 | 0.133 | 0.285 * | 0.298 * | 0.226 * | 0.367 * | - | ||

| 8. Green creativity | 0.019 | 0.126 | 0.230 * | 0.328 * | 0.239 * | 0.372 * | 0.595 * | - | |

| 9. Place of birth | −0.143 | −0.041 | −0.072 | −0.010 | 0.037 | 0.002 | −0.053 | −0.113 | - |

| Mean | 0.620 | 2.520 | 3.610 | 3.940 | 3.030 | 3.530 | 3.740 | 3.270 | 0.690 |

| Standard deviation | 0.490 | 1.100 | 1.380 | 0.750 | 0.980 | 0.880 | 0.830 | 1.010 | 0.460 |

References

- Quan, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y. Empowered to excel: How and when customer empowering behaviors ignite employee customer-oriented citizenship behaviors. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2025, 34, 704724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, T.; Ozturen, A.; Karatepe, O.M.; Uner, M.M.; Kim, T.T. Management commitment to the ecological environment, green work engagement and their effects on hotel employees’ green work outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 3084–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Jolly, P.M. Engaging employees through transformational leadership: The mediating role of emotional energy. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 1169–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Translating responsible leadership into team customer relationship performance in the tourism context: The role of collective job crafting. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 1620–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguía, A.; Topa, G.; Pocinho, R.F.D.S.; Munoz, J.J.F. Direct effect of personality traits and work engagement on job crafting: A structural model. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2025, 220, 112518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Mattila, A.; Leong, A.M.W.; Cui, Z.; Sun, Z.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y. Examining the cross-level mechanisms of the influence of supervisors’ job crafting on frontline employees’ engagement and performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 4428–4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Crafting the sales job collectively in the tourism industry: The roles of charismatic leadership and collective person-group fit. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, A.; Badar, K. Does spiritual leadership promote employees’ green creativity? The mediating effect of green work engagement. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2025, 12, 756–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Han, Z. Environmentally-Specific Empowered Leadership and Employee Green Creativity: The Role of Green Crafting and Environmental Culture. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sürücü, L. The influence of green inclusive leadership on green creativity: A moderated mediation model. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2024, 33, 678–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darban, G.; Karatepe, O.M.; Rezapouraghdam, H. Does work engagement mediate the impact of green human resource management on absenteeism and green recovery performance? Empl. Relat. 2022, 44, 1092–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Farrukh, M.; Iqbal, M.K.; Farhan, M.; Wu, Y. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior: The role of organizational pride and employee engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Bai, J.; Wu, T. Should we be “challenging” employees? A study of job complexity and job crafting. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Matute, J.; Kubal-Czerwińska, M.; Mika, M. How to encourage food waste reduction in kitchen brigades: The underlying role of ‘green transformational leadership and employees’ self-efficacy. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 59, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.D.; Nguyen, T.T.N.; Nguyen, H.N.; Nguyen, M.H. Sustainable management in the hospitality industry: The influence of green human resource management on employees’ pro-environmental behavior and environmental performance. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights, 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, T.A.; Farooq, R.; Talwar, S.; Awan, U.; Dhir, A. Green inclusive leadership and green creativity in the tourism and hospitality sector: Serial mediation of green psychological climate and work engagement. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1716–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, T. Do qualitative and quantitative job insecurity influence hotel employees’ green work outcomes? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.; Li, C. Impact of green inclusive leadership on employee green creativity: Mediating roles of green passion and green absorptive capacity. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2025, 46, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, A.K.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Hanafiah, M.H.; Aziz, R.C.; Mohamed, A.E.; Ashraf, M.U.; Azam, N.R.A.N. Empowering pro-environmental potential among hotel employees: Insights from self-determination theory. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 1070–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansong, A.; Andoh, R.P.K.; Ansong, L.O.; Hayford, C.; Owusu, N.K. Toward employee green creativity in the hotel industry: Implications of green knowledge sharing, green employee empowerment and green values. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights, 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.; Gull, N.; Xiong, Z.; Shu, A.; Faraz, N.A.; Pervaiz, K. The influence of inclusive leadership on hospitality employees’ green innovative service behavior: A multilevel study. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 56, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, H.E.; Uysal, M. Leadership, green innovation, and green creativity: A systematic review. Serv. Ind. J. 2022, 42, 280–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Huang, L.M.; He, M.; Ye, B.H. Understanding pro-environmental behavior in tourism: Developing an experimental model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 57, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Raza, A.; Rafiq, M. Environmentally specific authentic leadership and team green creative behavior based on cognitive-affective path systems. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 3662–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.I.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Fawehinmi, O. Green HRM and hospitality industry: Challenges and barriers in adopting environmentally friendly practices. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Wang, Y. Green intellectual capital and green competitive advantage in hotels: The role of environmental product innovation and green transformational leadership. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 57, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P. Greening the Workplace: Theories, Methods, and Research; Palgrave MacMillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Hassannia, R.; Karatepe, T.; Kim, T.T. Test of a moderated mediation model of green huma resource management, workplace spirituality, environmental commitment, and green behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 126, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.F.; Sabino, A.; Antunes, V. The effect of green human resources management practices on employees’ affective commitment and work engagement: The moderating role of employees’ biospheric value. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, R.S.; Karatepe, O.M.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Rescalvo-Martin, E.; Enea, C. Green human resource management, job embeddedness and their effects on restaurant employees’ green voice behaviors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 3453–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayla, O.; Kelees, H.; Silik, C.E.; Akbulut, C. How does the green and non-green star moderate the effect of hotel environmental strategy on sustainable awareness and green employee behavior? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, E.; Zappalà, S.; Topa, G. Job crafting as a mediator between work engagement and wellbeing outcomes: A time-lagged study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, H.; Tian, F.; Ho, J.A.; Roh, T.; Latif, B. Understanding voluntary pro-environmental behavior among colleagues: Roles of green crafting, psychological empowerment, and green organizational climate. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.E. Job crafting to innovative and extra-role behaviors: A serial mediation through fit perceptions and work engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 106, 103288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, J. The greater the incentives, the better the effect? Interactive moderating effects on the relationship between green motivation and green creativity. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands—Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Tims, M.; Derks, D. Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Hou, X. The effects of job crafting on tour leaders’ work engagement: The mediating role of person-job fit and meaningfulness of work. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1649–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beer, L.T.; Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting and its impact on work engagement and job satisfaction in mining and manufacturing. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2016, 19, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y. Does work engagement mediate the influence of job resourcefulness on job crafting? An examination of frontline hotel employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1684–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Nambudiri, R. Work engagement, job crafting and innovativeness in the Indian IT industry. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1381–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleel, A.; Sarmad, M. Inclusive leader and job crafting: The role of work engagement and job autonomy in service sector organizations. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2024, 11, 948–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Ampofo, E.T.; Kim, T.T.; Oh, S. The trickle-down effect of leader psychological capital on follower creative performance: The mediating roles of job crafting and knowledge sharing. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 3168–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, G.J. Using a person-environment fit model to predict job involvement and organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1987, 30, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawela, M.; Bayraktar, O.; Karabulut, A.T.; Sari, B.; Alqahtani, M.S. Advancing sustainability in Turkish hospitality sector: The interplay between green HRM, eco-friendly behaviors, and organizational support. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaque, S.; Ansari, N.Y. Empowering sustainability: The role of green human resource management in fostering pro-environmental behavior in hospitality and employees. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights, 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badwy, H.E.; Qalati, S.A.; El-Bardan, M.F. Revolutionizing sustainable success: Unveiling the power of green human resource management, green innovation and green human capital. Benchmarking Int. J. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasamy, U.; Joseph, M.S.; Parayitam, S. Green human resource management practices and employee green behavior. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 67, 2810–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasami, M.; Phetvaroon, K.; Dewan, M.; Stosic, K. Does employee resilience work? The effects of job insecurity on psychological withdrawal behavior and work engagement. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2024, 7, 2862–2882. [Google Scholar]

- Gabler, C.B.; Landers, V.M.; Agnihotri, R.; Morgan, T.R. Environmental orientation on the frontline: A boundary-spanning perspective for supply chain management. J. Bus. Logist. 2023, 44, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang-Van, T. Emotional and behavioral responses of consumers toward the indoor environmental quality of green luxury hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, G.; Lugosi, P.; Hawkims, E. Factors influencing hospitality employees’ pro-environmental behaviors toward food waste? Sustainability 2022, 14, 9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatter, A. Challenges and solutions for environmental sustainability in the hospitality industry. Sustainability 2022, 15, 11941. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, N.; Hadaya, P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Cheah, J.H.; Becker, J.M.; Ringle, C.M. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Schuberth, F. Using confirmatory composite analysis to assess emergent variables in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Peterson, R.A.; Brown, S.P. Structural equation modeling in marketing: Some practical reminders. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2012, 20, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, G.C.; Nitzl, C.; Roldán, J.L. Mediation analyses in partial least squares structural equation modeling: Guidelines and empirical examples. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Proksch, D.; Ringle, C.M. Revisiting Gaussian copulas to handle endogenous regressors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Proksch, D.; Sarstedt, M.; Pinkwart, A.; Ringle, C.M. Addressing endogeneity in international marketing applications of partial least squares structural equation modeling. J. Int. Mark. 2018, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E. Design your own job through job crafting. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Eslamlou, A. Outcomes of job crafting among flight attendants. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2017, 62, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.I.; Qabool, S.; Anwar, A.; Khan, S.A. Green human resource management practices: A hierarchical model to evaluate the pro-environmental behavior of hotel employees. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 8, 1217–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Cropanzano, R. The conservation of resources model applied to work-family conflict and strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 71 (38) |

| Female | 116 (62) |

| Age | |

| 18–27 | 88 (47.1) |

| 28–37 | 58 (31) |

| 38–47 | 20 (10.7) |

| 48–57 | 10 (5.3) |

| 58 and above | 11 (5.9) |

| Education | |

| Secondary and high school | 53 (28.3) |

| Two-year college degree | 42 (22.5) |

| Four-year college degree | 86 (46) |

| Graduate degree | 6 (3.2) |

| Organizational tenure | |

| Below 1 year | 17 (9.1) |

| 1–5 years | 105 (56.1) |

| 6–10 years | 34 (18.2) |

| 11–15 years | 18 (9.6) |

| 16–20 years | 8 (4.3) |

| Longer than 20 years | 5 (2.7) |

| Marital status | |

| Single or divorced | 145 (77.5) |

| Married | 42 (22.5) |

| Position | |

| Entry-level | 53 (28.3) |

| Supervisory | 134 (71.7) |

| Discrepancies | First-Order Level | Second-Order Level | Conclusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | HI99 | Value | HI99 | ||

| SRMR | 0.046 | 0.050 | 0.045 | 0.047 | Supported |

| dULS | 1.108 | 1.296 | 0.571 | 0.606 | Supported |

| dG | 0.580 | 0.677 | 0.268 | 0.337 | Supported |

| Composite | Mean | SD | Kurtosis | Skewness | Loadings | α | pA | pC | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work engagement | 0.949 | 0.951 | 0.957 | 0.711 | |||||

| gwe01 | 3.540 | 1.301 | −0.003 | −0.610 | 0.838 *** | ||||

| gwe02 | 3.610 | 1.452 | −0.460 | −0.542 | 0.849 *** | ||||

| gwe03 | 3.893 | 1.683 | −0.389 | −0.773 | 0.897 *** | ||||

| gwe04 | 3.091 | 1.835 | −1.027 | −0.245 | 0.854 *** | ||||

| gwe05 | 2.957 | 1.748 | −0.955 | −0.164 | 0.839 *** | ||||

| gwe06 | 3.957 | 1.592 | −0.097 | −0.732 | 0.786 *** | ||||

| gwe07 | 4.037 | 1.716 | −0.546 | −0.673 | 0.838 *** | ||||

| gwe08 | 3.765 | 1.635 | −0.554 | −0.557 | 0.864 *** | ||||

| gwe09 | 3.620 | 1.671 | −0.698 | −0.437 | 0.818 *** | ||||

| Job crafting | 0.821 | 0.875 | 0.891 | 0.734 | |||||

| Structural JRs | 0.899 *** | 0.889 | 0.891 | 0.923 | 0.751 | ||||

| Structural_JR01 | 3.930 | 0.998 | −0.246 | −0.707 | 0.883 *** | ||||

| Structural_JR02 | 3.914 | 1.120 | 0.197 | −0.981 | 0.894 *** | ||||

| Structural_JR03 | 4.043 | 0.953 | 0.061 | −0.797 | 0.884 *** | ||||

| Structural_JR04 | 3.979 | 0.907 | 0.359 | −0.781 | 0.803 *** | ||||

| Structural_JR05 | Dropped | ||||||||

| Social JRs | 0.747 *** | 0.855 | 0.877 | 0.893 | 0.627 | ||||

| Social_JR01 | 2.845 | 1.189 | −0.886 | 0.150 | 0.751 *** | ||||

| Social_JR02 | 3.027 | 1.293 | −1.117 | −0.020 | 0.839 *** | ||||

| Social_JR03 | 2.840 | 1.306 | −1.080 | 0.141 | 0.791 *** | ||||

| Social_JR04 | 2.952 | 1.255 | −1.019 | 0.026 | 0.823 *** | ||||

| Social_JR05 | 3.503 | 1.082 | −0.695 | −0.288 | 0.751 *** | ||||

| Challenging JDs | 0.914 *** | 0.841 | 0.849 | 0.887 | 0.611 | ||||

| Challeng_JD01 | 3.599 | 1.097 | −0.197 | −0.647 | 0.837 *** | ||||

| Challeng_JD02 | 3.743 | 1.023 | 0.488 | −0.887 | 0.764 *** | ||||

| Challeng_JD03 | 3.487 | 1.125 | −0.417 | −0.477 | 0.772 *** | ||||

| Challeng_JD04 | 3.636 | 1.218 | −0.482 | −0.688 | 0.778 *** | ||||

| Challeng_JD05 | 3.171 | 1.144 | −0.790 | −0.276 | 0.753 *** | ||||

| Task-related pro-environmental behavior | 0.917 | 0.932 | 0.947 | 0.857 | |||||

| tPEB01 | 3.733 | 0.938 | 0.511 | −0.733 | 0.897 *** | ||||

| tPEB02 | 3.749 | 0.875 | 0.563 | −0.692 | 0.940 *** | ||||

| tPEB03 | 3.738 | 0.866 | 0.870 | −0.710 | 0.940 *** | ||||

| Green creativity | 0.938 | 0.940 | 0.951 | 0.766 | |||||

| gc01 | 3.406 | 1.191 | −0.617 | −0.561 | 0.906 *** | ||||

| gc02 | 3.246 | 1.190 | −0.813 | −0.391 | 0.928 *** | ||||

| gc03 | 3.257 | 1.187 | −0.789 | −0.336 | 0.884 *** | ||||

| gc04 | 3.037 | 1.190 | −0.862 | −0.150 | 0.876 *** | ||||

| gc05 | 3.278 | 1.074 | −0.620 | −0.339 | 0.787 *** | ||||

| gc06 | 3.390 | 1.096 | −0.408 | −0.603 | 0.864 *** | ||||

| HTMTratio [HTMTinference] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 3 | 4 |

| (1) Work Engagement | - | ||||||

| (2) Job Crafting | 0.709 [0.589–0.810] | - | |||||

| (2.1) Structural JRs | 0.668 [0.547–0.771] | n/a | - | ||||

| (2.2) Social JRs | 0.361 [0.210–0.515] | n/a | 0.610 [0.499–0.717] | - | |||

| (2.3) Challenging JDs | 0.736 [0.623–0.827] | n/a | 0.836 [0.755–0.900] | 0.608 [0.478–0.727] | - | ||

| (3) Task-PEB | 0.307 [0.154–0.451] | 0.415 [0.255–0.559] | 0.340 [0.180–0.491] | 0.257 [0.130–0.408] | 0.421 [0.263–0.570] | - | |

| (4) Green Creativity | 0.244 [0.105–0.407] | 0.424 [0.263–0.577] | 0.351 [0.203–0.491] | 0.268 [0.137–0.426] | 0.421 [0.263–0.568] | 0.641 [0.528–0.742] | - |

| VIF | Path Coefficient (p-Value) | t-Value | CI | f2 | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects test | ||||||

| WENG → Task-PEB (c’1) | 1.863 | 0.082 (0.182) | 0.909 | −0.075; 0.222 | 0.004 | No effect |

| WENG → GC (c’2) | 1.863 | −0.028 (0.401) | −0.252 | −0.209; 0.156 | 0.001 | No effect |

| H1: WENG → Job Crafting (a1) | 1.000 | 0.657 (0.000) | 13.935 | 0.568; 0.726 | 0.758 | Supported |

| H2: Job Crafting → Task-PEB (b1) | 1.787 | 0.319 (0.000) | 3.683 | 0.169; 0.456 | 0.067 | Supported |

| H3: Job Crafting → GC (b2) | 1.787 | 0.400 (0.000) | 4.063 | 0.228; 0.550 | 0.106 | Supported |

| Mediating effects test | ||||||

| H4: WENG → Job Crafting → Task-PEB (a1b1) | 0.209 (0.000) | 3.467 | 0.114; 0.313 | Full mediation | Supported | |

| H5: WENG → Job Crafting → GC (a1b2) | 0.262 (0.000) | 3.709 | 0.150; 0.379 | Full mediation | Supported | |

| TOTAL EFFECT on Task-PEB | 0.291 (0.000) | 4.002 | 0.166; 0.404 | |||

| TOTAL EFFECT on GC | 0.234 (0.002) | 2.886 | 0.089; 0.358 | |||

| Control variables | ||||||

| Gender → Task-PEB | 1.035 | 0.244 (0.089) | 0.199 | −0.035; 0.520 | 0.016 | No effect |

| Organizational Tenure → Task-PEB | 1.069 | 0.078 (0.183) | 1.331 | −0.042; 0.189 | 0.007 | No effect |

| Gender → GC | 1.035 | −0.029 (0.842) | 0.199 | −0.306; 0.271 | 0.000 | No effect |

| Organizational Tenure → GC | 1.069 | 0.106 (0.090) | 1.697 | −0.021; 0.222 | 0.012 | No effect |

| Determination coefficient | R2 | Adjusted R2 | ||||

| Job Crafting | 0.431 | 0.428 | ||||

| Task-PEB | 0.142 | 0.133 | ||||

| GC | 0.146 | 0.137 | ||||

| Estimated model fit | Discrepancy value | HI99 | ||||

| SRMR | 0.048 | 0.048 | Supported | |||

| dULS | 0.633 | 0.639 | Supported | |||

| dG | 0.276 | 0.339 | Supported | |||

| Items of DV | PLS | LM | PLS-LM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2predict | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| Task-PEB | |||||||

| tPEB01 | 0.038 | 0.926 | 0.711 | 0.968 | 0.750 | −0.042 | −0.039 |

| tPEB02 | 0.076 | 0.846 | 0.662 | 0.876 | 0.687 | −0.030 | −0.025 |

| tPEB03 | 0.055 | 0.847 | 0.654 | 0.890 | 0.684 | −0.043 | −0.030 |

| Green Creativity | |||||||

| gc01 | 0.046 | 1.170 | 0.981 | 1.210 | 1.007 | −0.040 | −0.026 |

| gc02 | 0.034 | 1.176 | 0.991 | 1.208 | 1.014 | −0.032 | −0.023 |

| gc03 | 0.002 | 1.194 | 0.996 | 1.240 | 1.045 | −0.046 | −0.049 |

| gc04 | 0.042 | 1.173 | 0.970 | 1.204 | 1.006 | −0.031 | −0.036 |

| gc05 | 0.027 | 1.065 | 0.897 | 1.086 | 0.908 | −0.021 | −0.011 |

| gc06 | 0.001 | 1.102 | 0.920 | 1.142 | 0.960 | −0.040 | −0.040 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | p-Value | Value | p-Value | Value | p-Value | Value | p-Value | Value | p-Value | |

| Copula in WENG → Task-PEB | 0.545 | 0.074 | 0.485 | 0.125 | ||||||

| Copula in Job Crafting → Task-PEB | 0.413 | 0.279 | 0.213 | 0.590 | ||||||

| Copula in WENG → GC | 0.184 | 0.541 | 0.187 | 0.559 | ||||||

| Copula in Job Crafting → GC | 0.066 | 0.863 | −0.011 | 0.978 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gurcham, K.; Karatepe, O.M.; Rescalvo-Martin, E.; Avci, T. Work Engagement, Job Crafting, and Their Effects on Green Work Outcomes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210090

Gurcham K, Karatepe OM, Rescalvo-Martin E, Avci T. Work Engagement, Job Crafting, and Their Effects on Green Work Outcomes. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210090

Chicago/Turabian StyleGurcham, Ksenia, Osman M. Karatepe, Elisa Rescalvo-Martin, and Turgay Avci. 2025. "Work Engagement, Job Crafting, and Their Effects on Green Work Outcomes" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210090

APA StyleGurcham, K., Karatepe, O. M., Rescalvo-Martin, E., & Avci, T. (2025). Work Engagement, Job Crafting, and Their Effects on Green Work Outcomes. Sustainability, 17(22), 10090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210090