Impedance Characteristics and Stability Enhancement of Sustainable Traction Power Supply System Integrated with Photovoltaic Power Generation

Abstract

1. Introduction

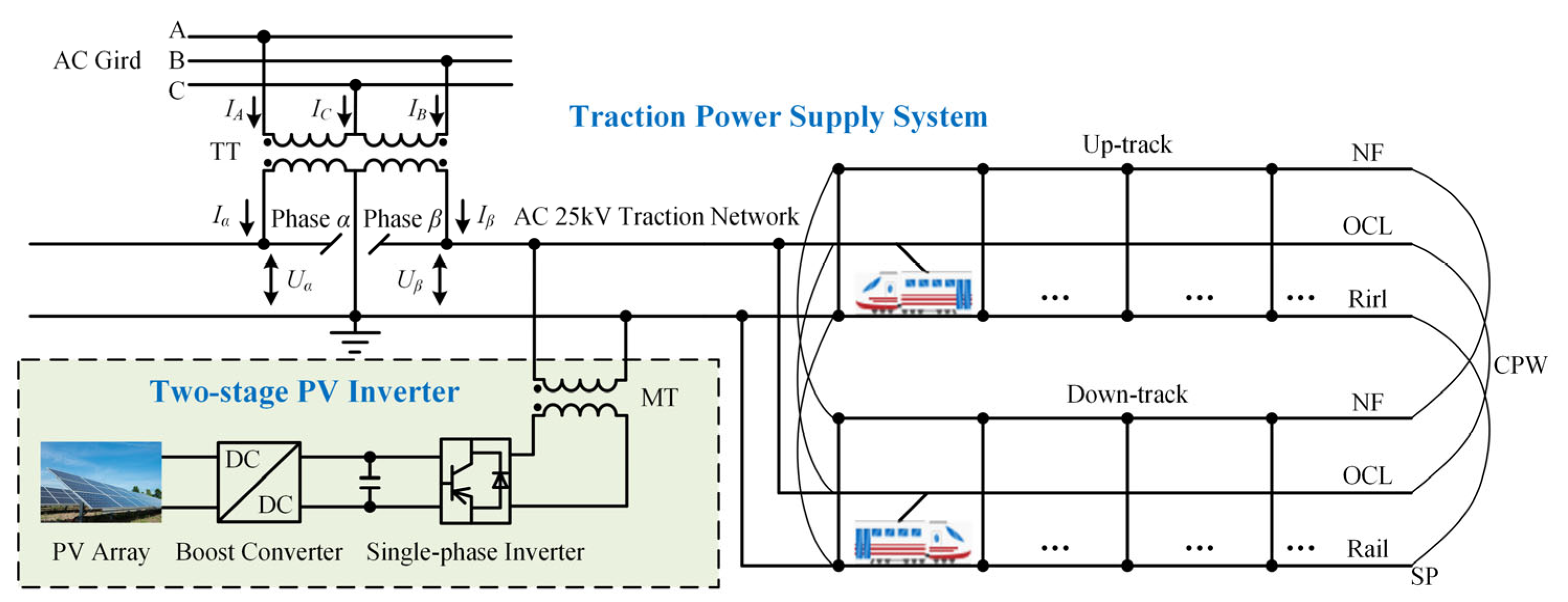

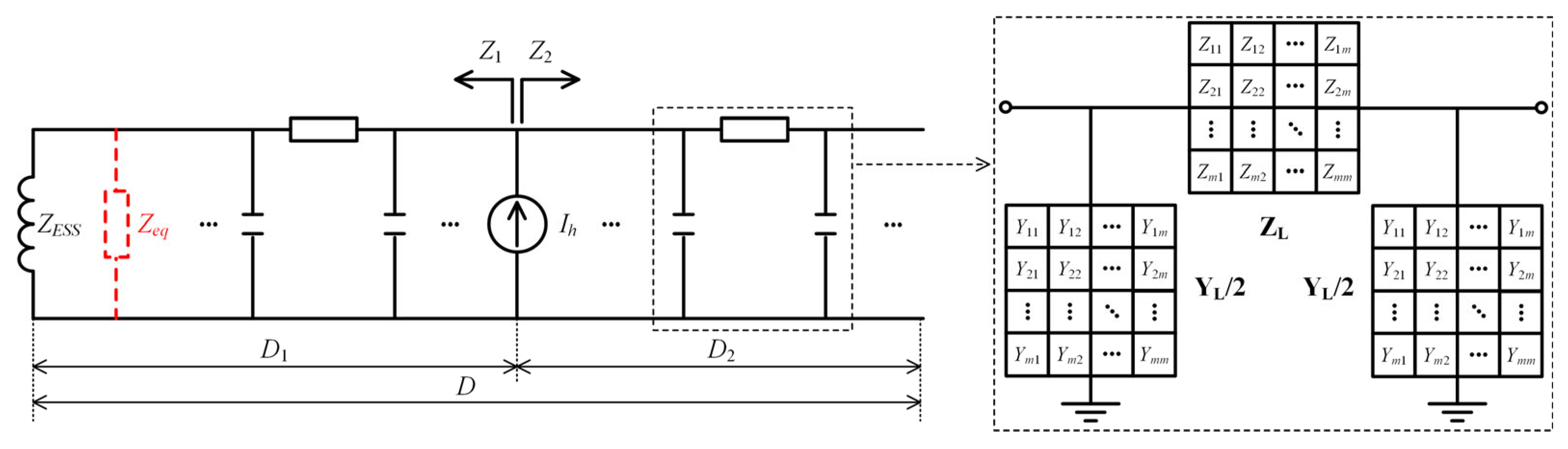

2. System Structure and Harmonic Model of TPSS Integrated with PV Power Generation

2.1. System Structure of TPSS Integrated with PV Power Generation

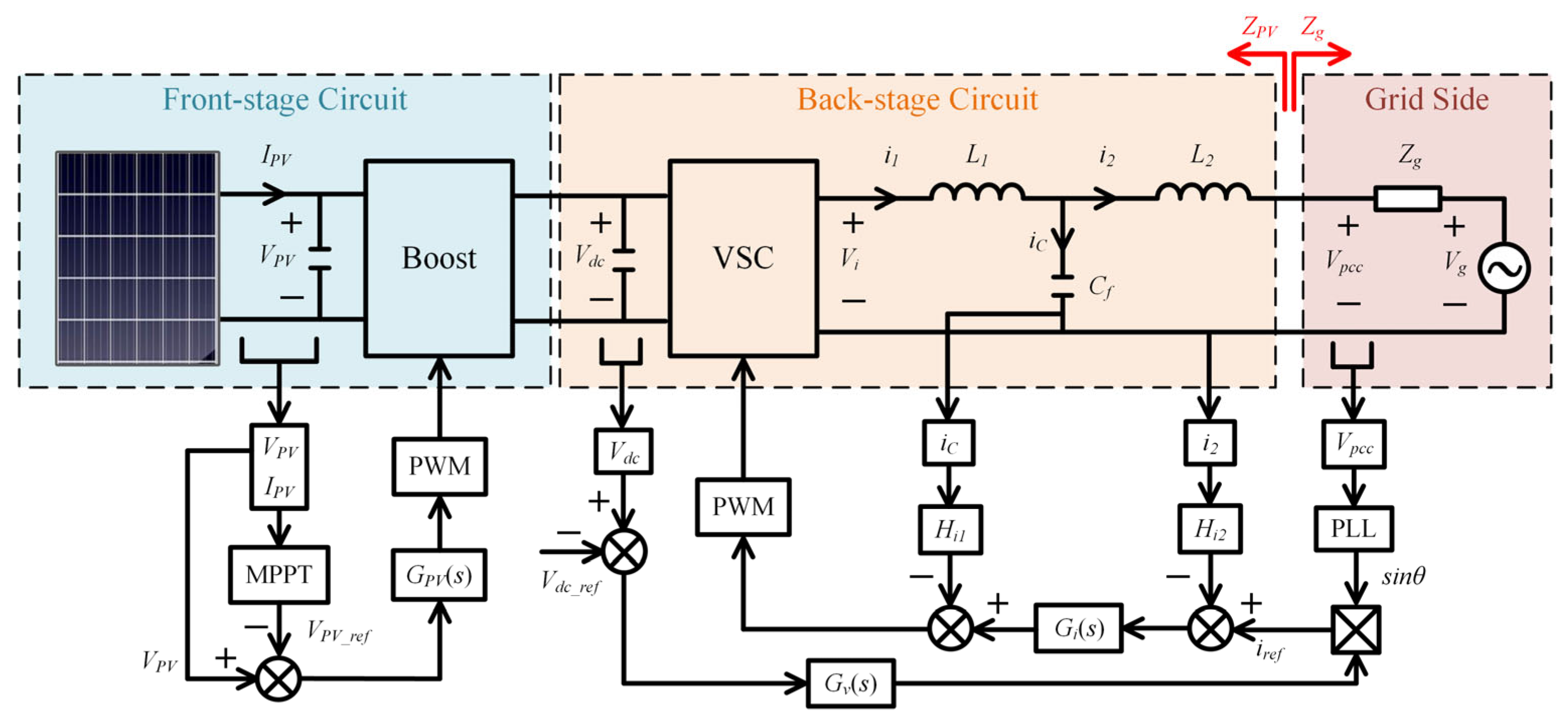

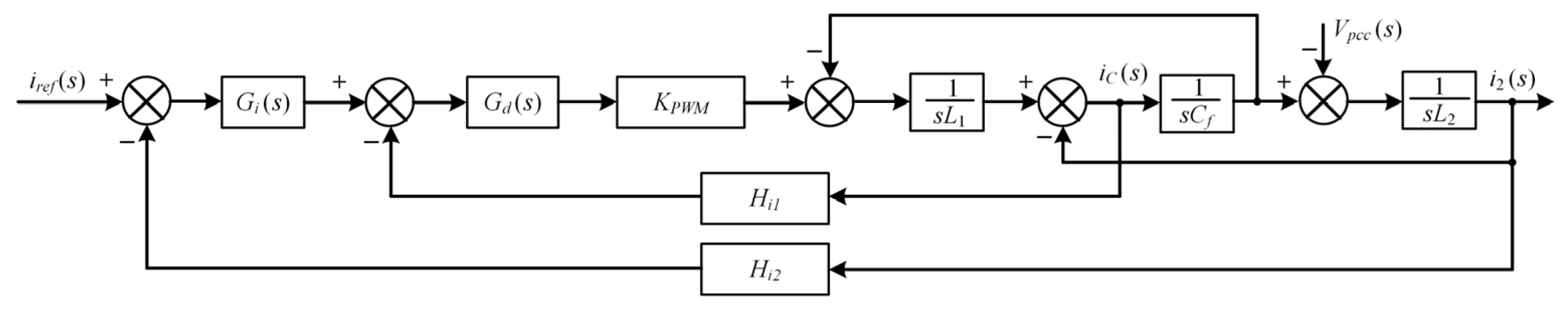

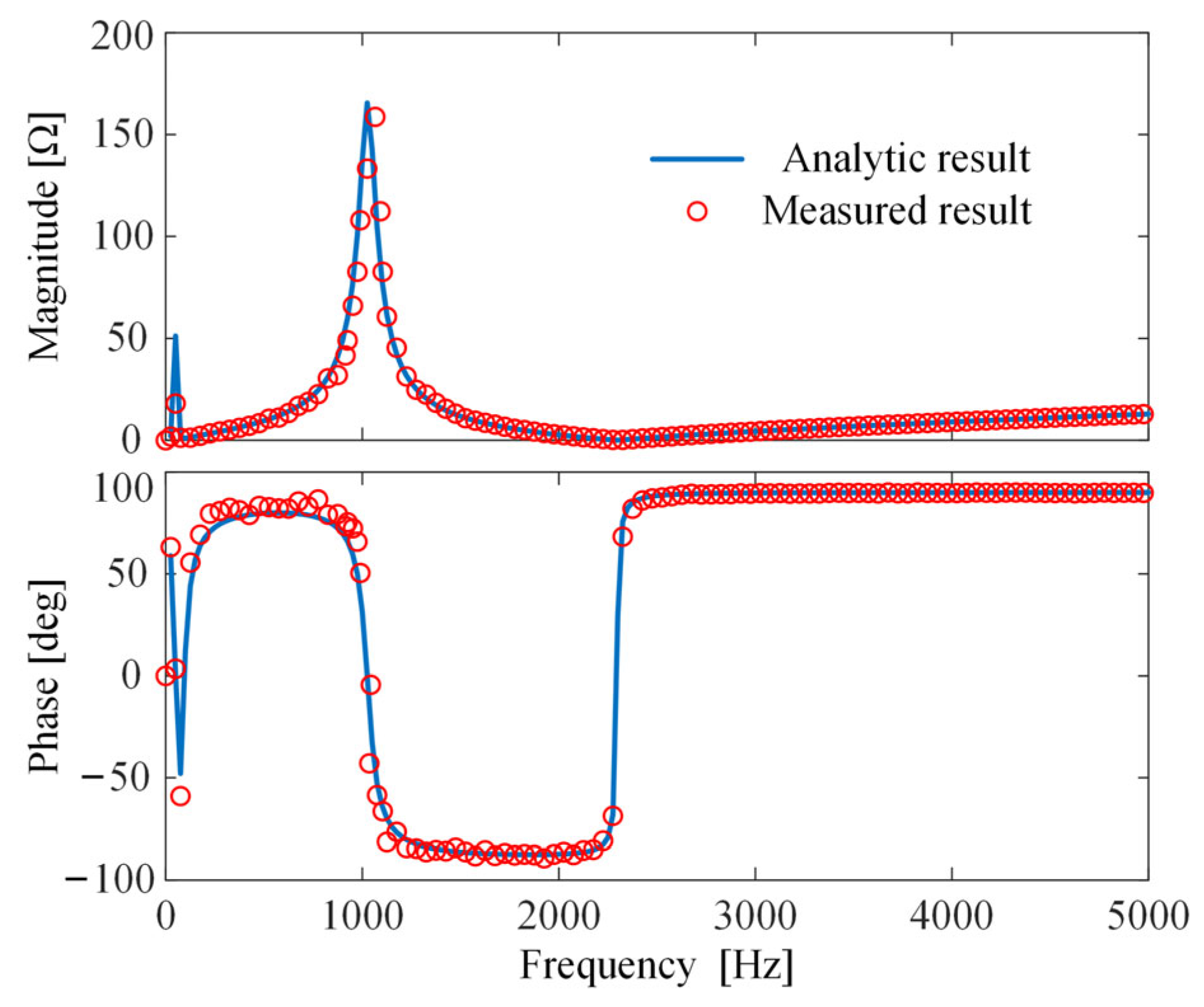

2.2. Harmonic Impedance Model of Two-Stage PV Inverter

2.3. Harmonic Impedance Model of TPSS Integrated with PV Power Generation

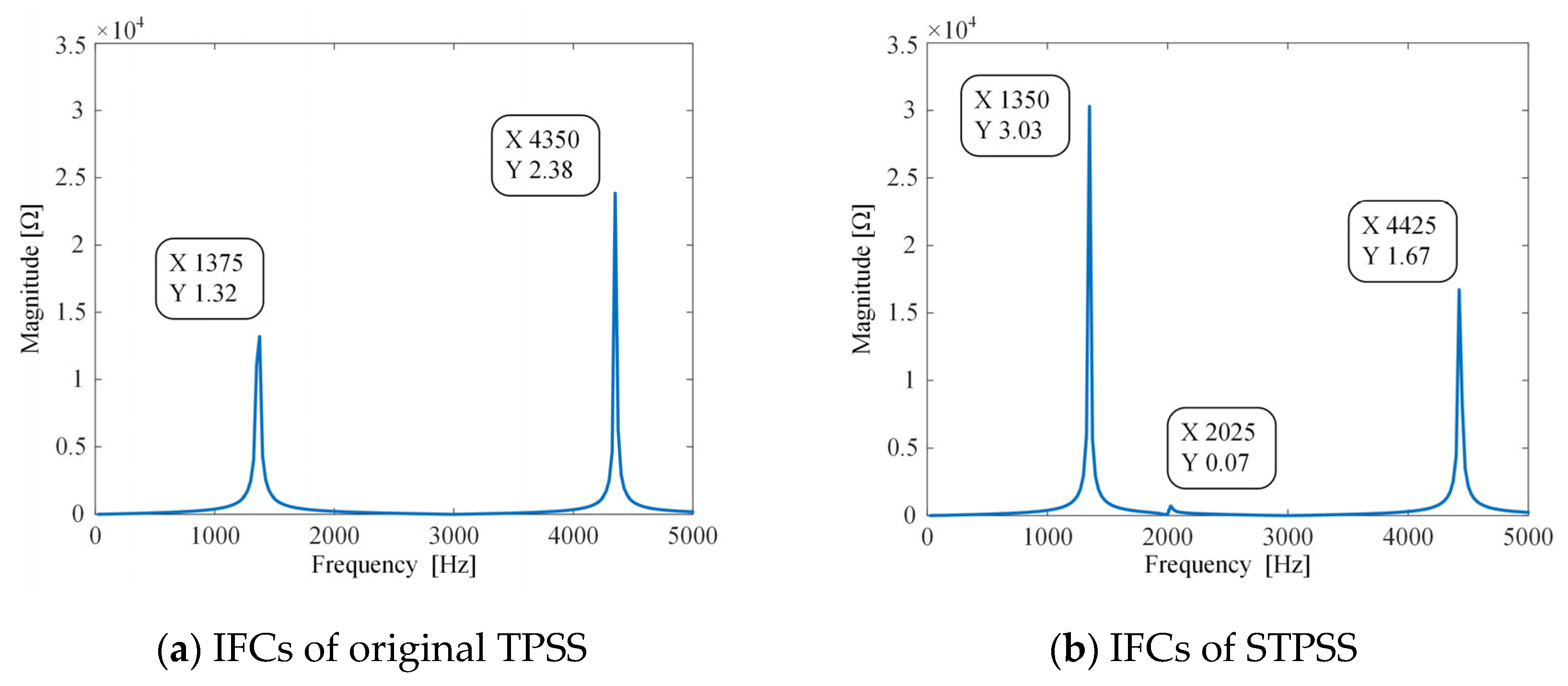

3. IFCs of TPSS Integrated with PV Power Generation

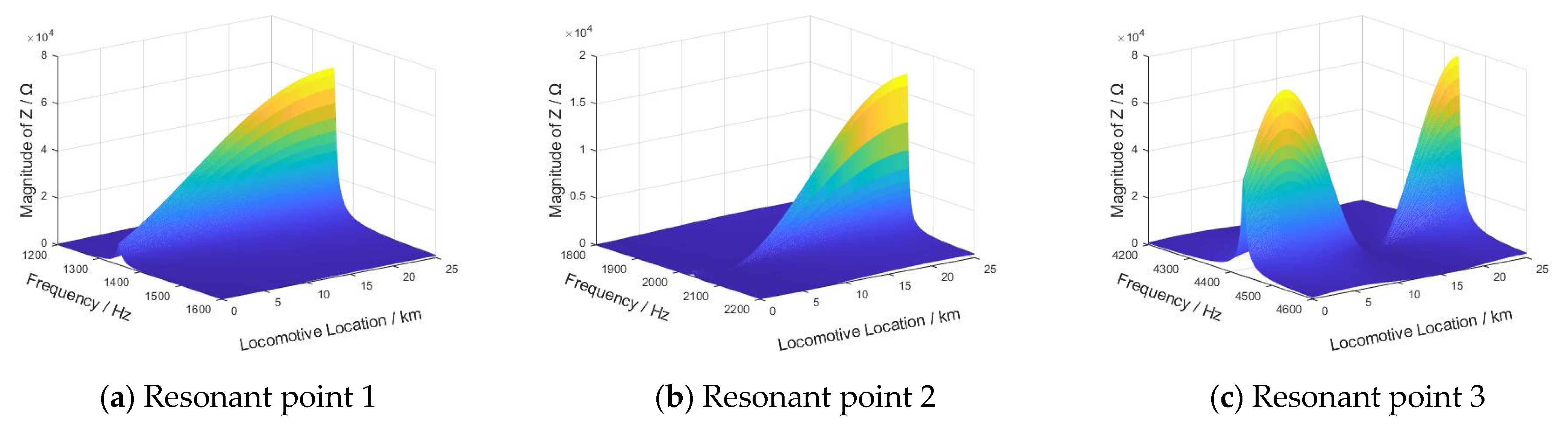

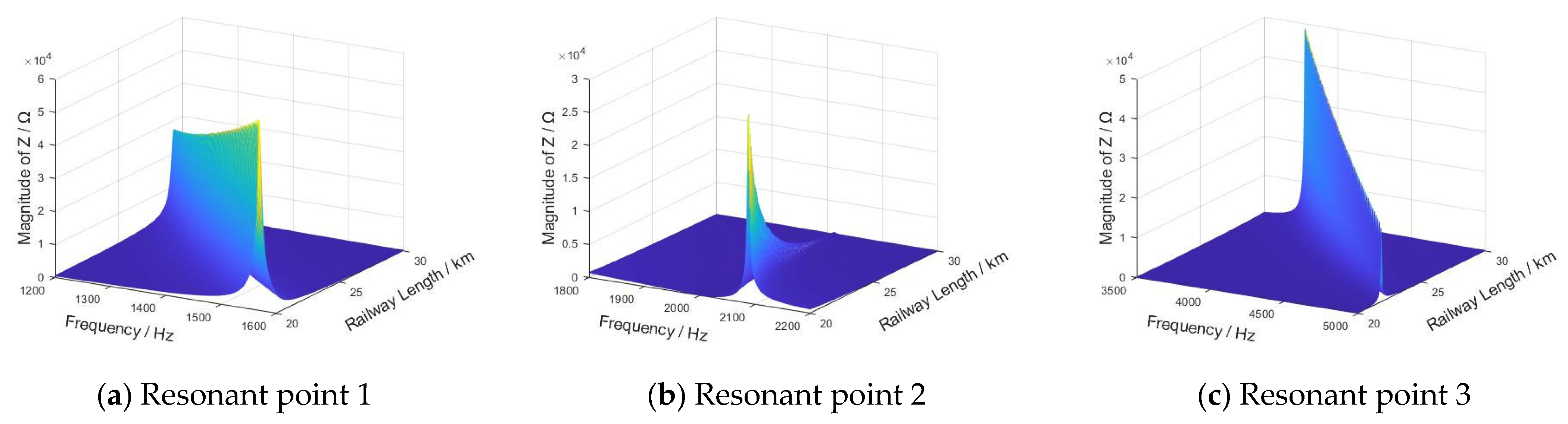

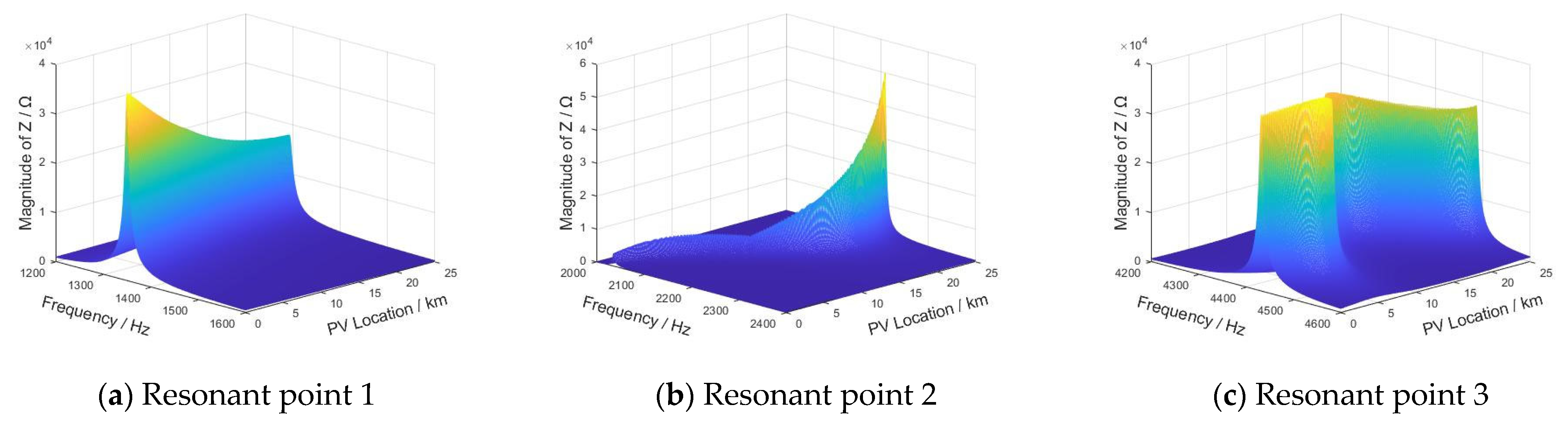

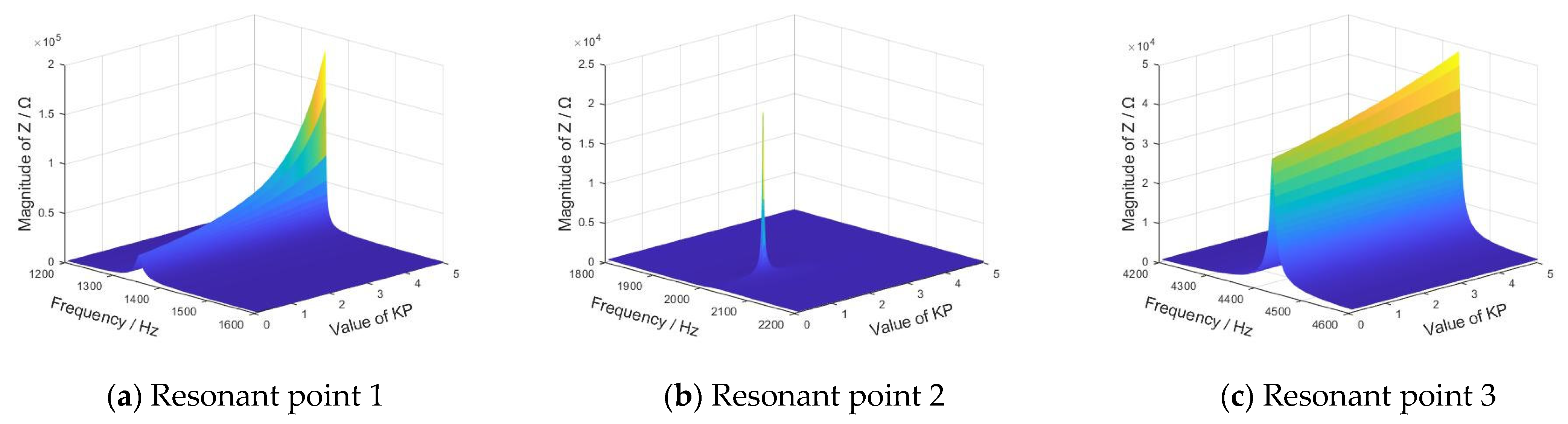

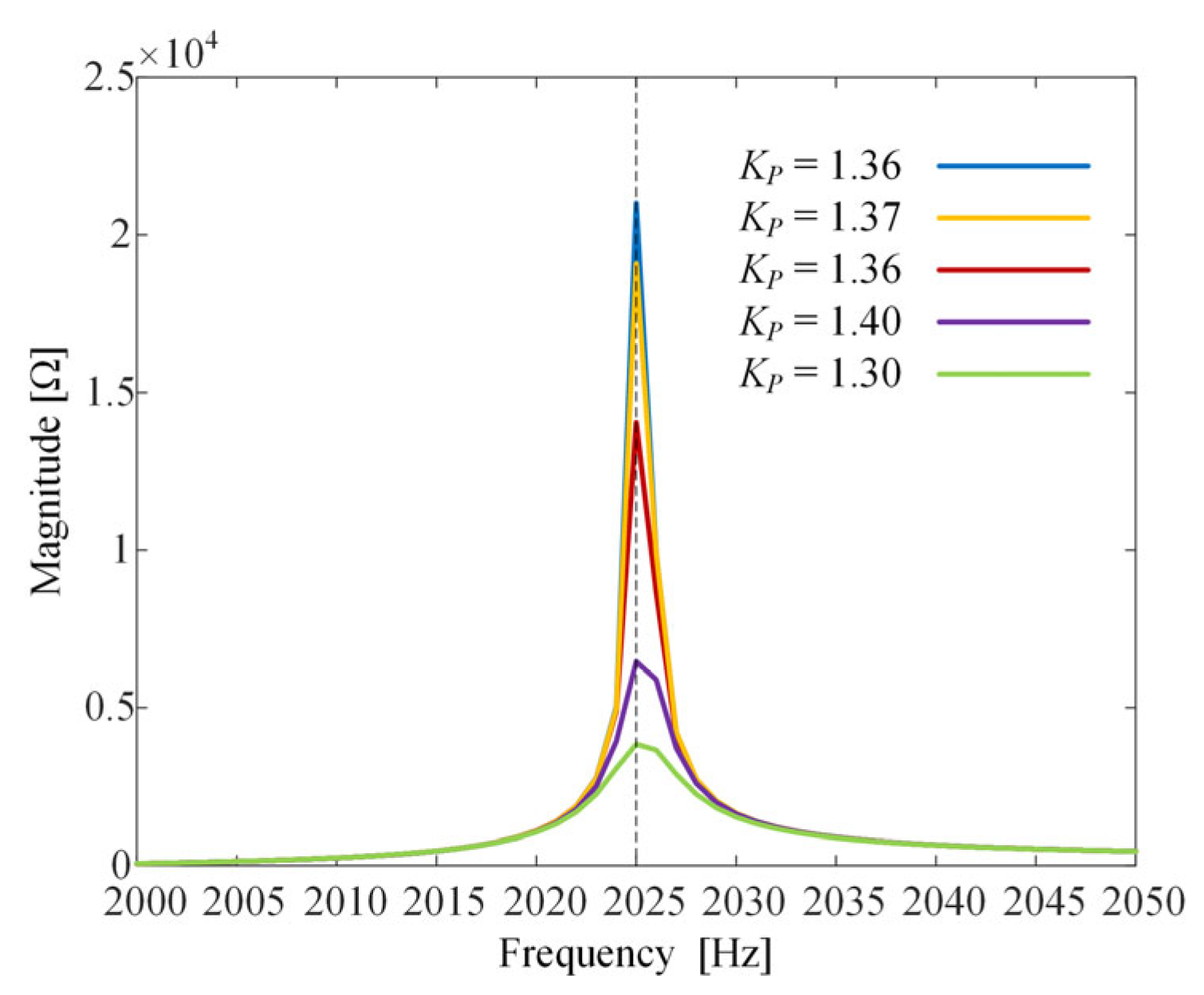

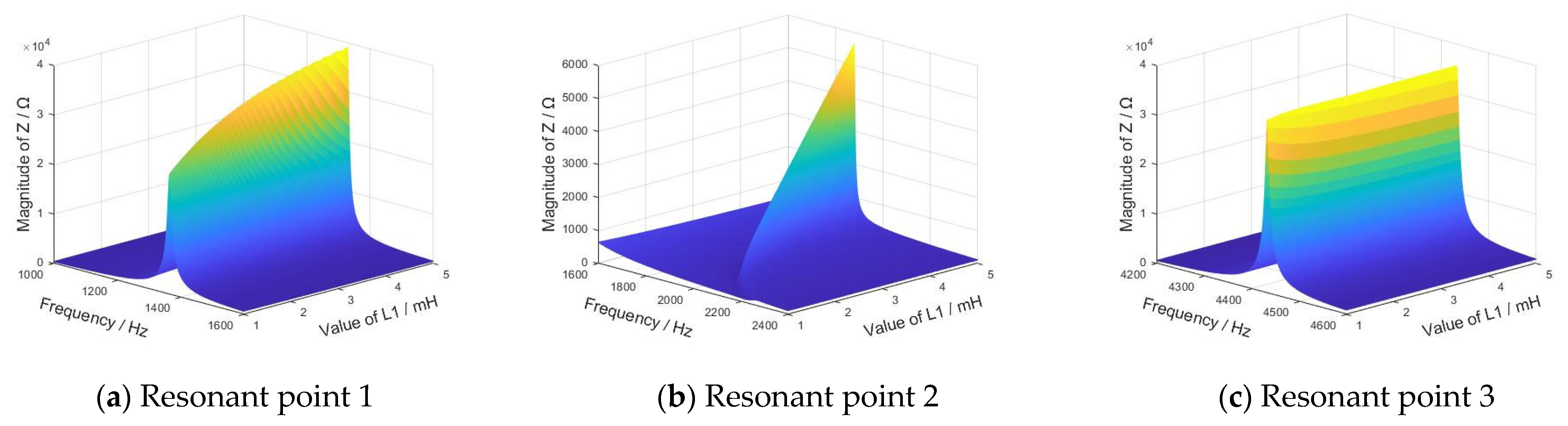

3.1. Influence Law of PV Power Generation on IFCs

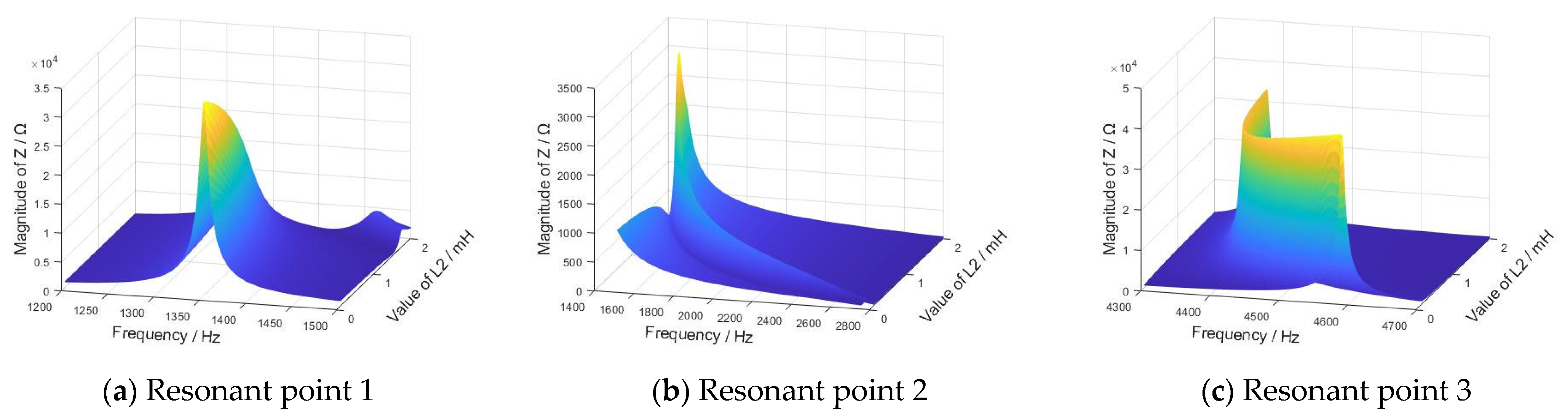

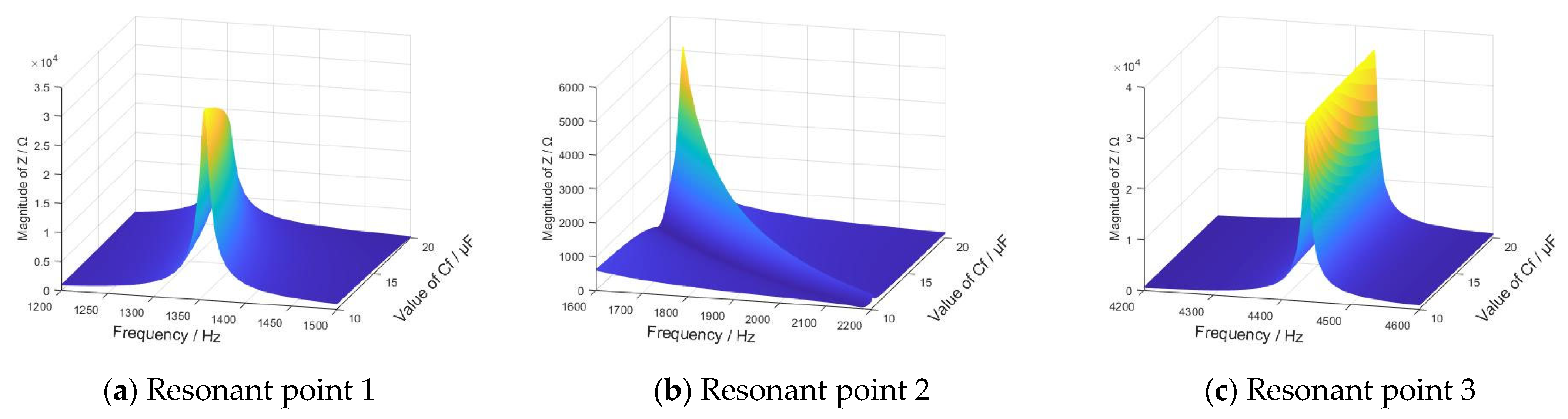

3.2. Influence Law of Critical System Parameters on IFCs

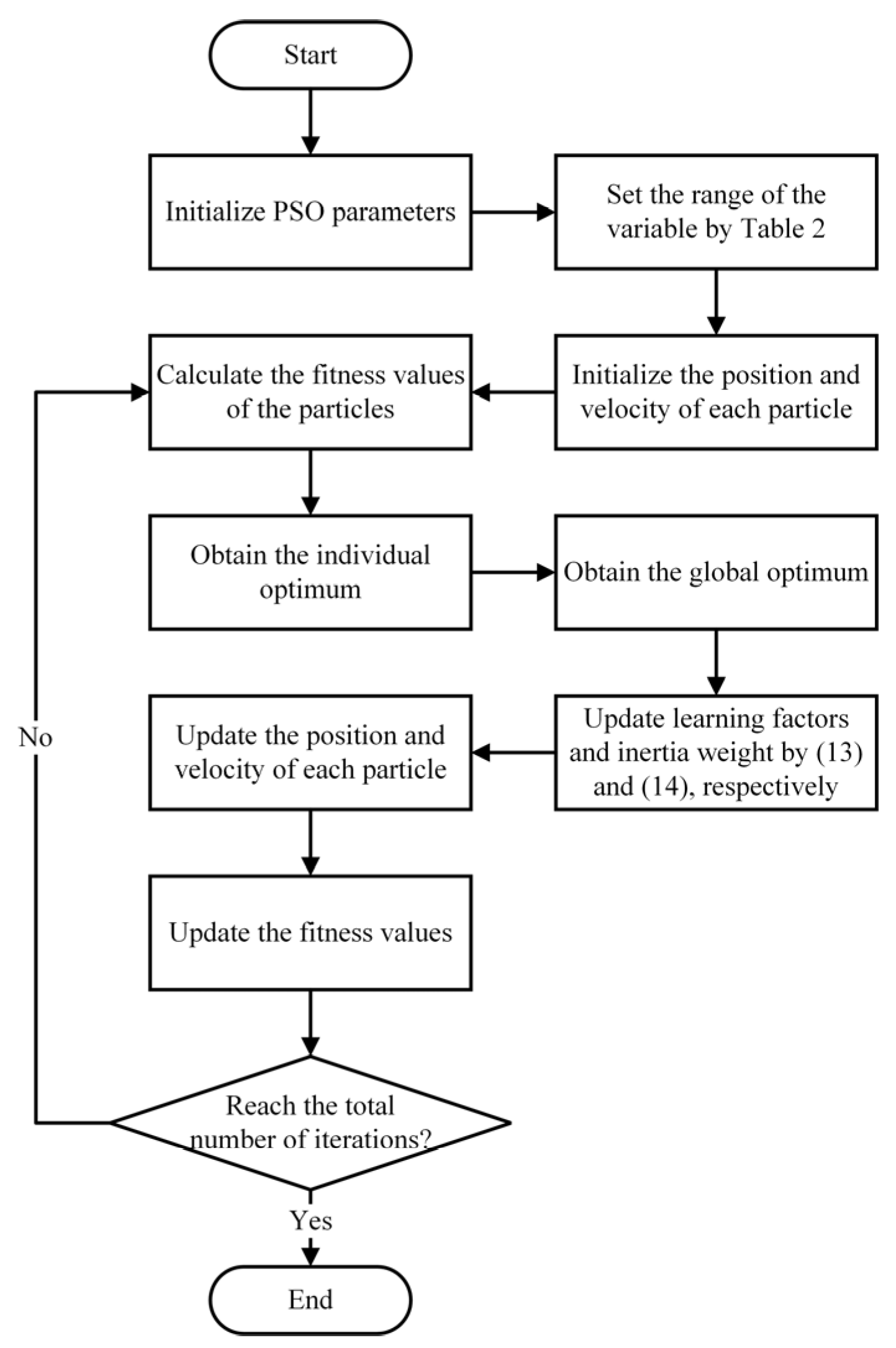

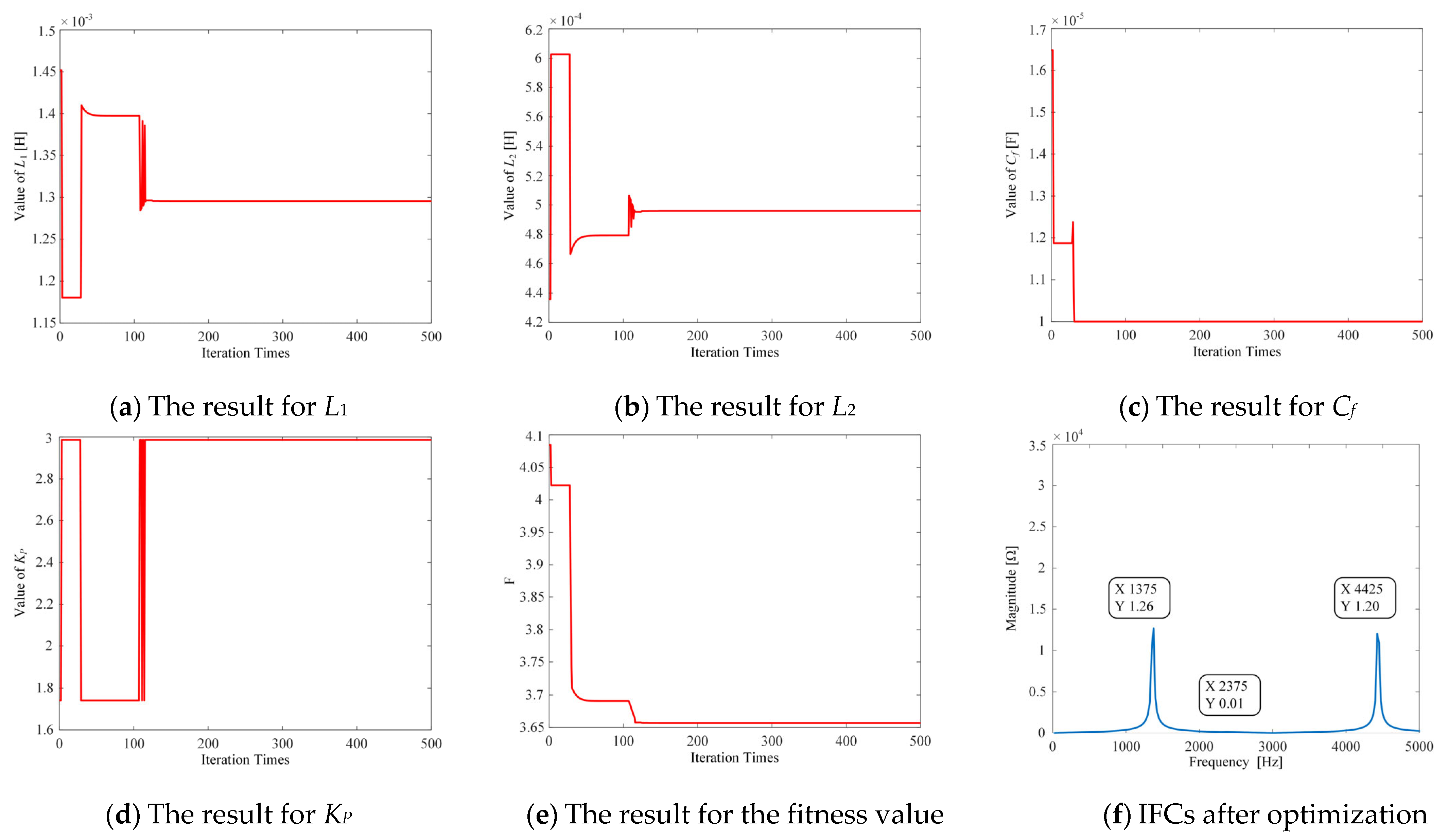

4. Multi-Parameter Co-Tuning Method Based on the Improved PSO Algorithm

5. Simulation Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Zhang, M.; Li, C. Distributed photovoltaic grid connected power generation system for high-speed railway. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on New Energy Power Engineering (ICNEPE), Huzhou, China, 24–26 November 2023; pp. 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Gu, X.; Chen, C. Robustness assessment of power network with renewable energy. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 217, 109138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, F.; Yin, W.; Liu, K. Photovoltaic potential prediction and techno-economic analysis of China railway stations. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 3696–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Ahmad, R.; Xavier, B. Integrating renewable energy into the electric railway system in dense urban regions. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Smart Power & Internet Energy Systems (SPIES), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 4–6 December 2024; pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinomi, N.; Tian, Z.; Yang, N.; Kano, N.; Jiang, L. Analysis of energy efficiency and resilience for AC railways with solar PV and energy storage systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2024, 2, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Wu, H.; Mao, Y.; Wu, T.; Song, G.; Terzic, J.S.; Shahidehpour, M. Photovoltaic power generation and energy storage capacity cooperative planning method for rail transit self-consistent energy systems considering the impact of DoD. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.; Tu, C.; Xiao, F.; Hou, Y.; Shen, X. Parallel-execute-based real-time energy management strategy for STPSS integrated PV and ESS. Appl. Energy 2025, 385, 125538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Dai, C.; Chen, W.; Gao, S. Experimental investigation and adaptability analysis of hybrid traction power supply system integrated with photovoltaic sources in AC-fed railways. IEEE Trans. Transport. Electrific. 2021, 7, 1750–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Hu, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, K.; He, Z. Combined active and reactive power flow control strategy for flexible railway traction substation integrated with ESS and PV. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 1969–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, N.; Xu, J.; Xiang, J.; Liu, Y.; Kong, L. High-order harmonic elimination and resonance damping based on inductive-filtering transformer for electrified railway transportation system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 5157–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, M.; Molinas, M.; Song, K.; Liu, Q. Assessing high-order harmonic resonance in locomotive-network based on the impedance method. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 68119–68131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Sun, B.; Yang, Q.; Wu, M.; He, T. Harmonic overvoltage analysis of electric railways in a wide frequency range based on relative frequency relationships of the vehicle–grid coupling system. Energies 2020, 13, 6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Lu, W.; Hu, H.; Zhu, X.; He, Z. Stability enhancement method based on adaptive virtual impedance control for a PV-integrated electrified railway system. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Hui, Y.; He, Y.; Han, X.; He, X.; Wang, P. Impedance model based coordination control of secondary ripple in DC microgrid. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 29723–29737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E.; Han, Y.; Lin, X.; Yang, P.; Blaabjerg, F.; Zalhaf, A.S. Impedance characteristics investigation and oscillation stability analysis for two-stage PV inverter under weak grid condition. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 209, 108053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Hu, G.; Liu, F.; Zhang, G. Multiple vehicles and traction network interaction system stability analysis and oscillation responsibility identification. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 6148–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Hu, H.; Xiao, D.; Song, Y.; He, Z. An improved controlled-frequency-band impedance measurement scheme for railway traction power system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 3, 2184–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, M.; Li, J.; Yang, S. Frequency-scanning harmonic generator for (inter) harmonic impedance tests and its implementation in actual 2 × 25 kV railway systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 4801–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Wu, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, Q.; Agelidis, V.G.; Konstantinou, G. High-order harmonic resonances in traction power supplies: A review based on railway operational data, measurements, and experience. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 2501–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuar, M.N.K.; Abdullah, N. Dominant harmonic current reduction using passive power filter. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Power and Energy (PECon), Langkawi, Malaysia, 5–6 December 2022; pp. 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirasugol, S.; Domkitpanya, T.; Narongrit, T.; Areerak, K. Harmonic elimination of AC electric railway systems using shunt active power filters. In Proceedings of the 2024 12th International Electrical Engineering Congress (iEECON), Pattaya, Thailand, 6–8 March 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, H.V.; Raveendran, R. Trapezoidal PWM scheme for selective harmonic elimination in multilevel inverters. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Recent Advances in Intelligent Computational Systems (RAICS), Kothamangalam, India, 16–18 May 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, W.; Chen, H.; Deng, W.; Chen, H.; Zhao, H. Multi-strategy particle swarm and ant colony hybrid optimization for airport taxiway planning problem. Inf. Sci. 2022, 612, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Zhu, H.; Sun, X.; Lin, S. Evaluation of power supply capability and quality for traction power supply system considering the access of distributed generations. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2020, 14, 3644–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaneto, U.C.; Knight, A.M. Full-order and simplified dynamic phasor models of a single-phase two-stage grid-connected PV system. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 26712–26728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhari, B.; Karchi, N. Design, modeling and analysis of LCL filter for three phase inverter. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Smart Power Control and Renewable Energy (ICSPCRE), Rourkela, India, 19–21 July 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.G.P.; Dias, R.F.S.; Rolim, L.G.B. Disturbance rejection analysis of grid-connected VSCs controlled in the stationary reference frame under voltage harmonic disturbances. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 8th Southern Power Electronics Conference and 17th Brazilian Power Electronics Conference (SPEC/COBEP), Florianopolis, Brazil, 26–29 November 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Xie, S. Study on resonance characteristic of continuous co-phase traction power supply system. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2023, 17, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, X. Research on multi-objective microgrid operation optimization based on improved particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Mechatronics Technology (ICEEMT), Hangzhou, China, 5–7 July 2024; pp. 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subsystems | Parameters | Symbols | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traction transformer | Transformation ratio | KTT | 110 kV/27.5 kV |

| Railway | Railway length | D | 25 km |

| Resistance value | r | 0.106 Ω/km | |

| Inductance value | l | 1.728 mH/km | |

| Capacitance value | c | 17.96 nF/km | |

| Matching transformer | Transformation ratio | KMT | 27.5 kV/1 kV |

| PV inverter | Rated capacity | SPV | 1 MW |

| Number of parallel inverters | n | 5 | |

| DC-link voltage | Vdc | 2000 V | |

| Proportional gain of current controller | KP | 1 | |

| Inverter-side inductor | L1 | 2 mH | |

| Grid-side inductor | L2 | 0.5 mH | |

| Filter capacitor | Cf | 12 μF |

| Parameters | Symbols | Ranges |

|---|---|---|

| Locomotive location | D1 | [0 km, 25 km] |

| Railway length | D | [20 km, 30 km] |

| PV integration location | X | [0 km, 25 km] |

| Proportional gain of current controller | KP | [0, 5] |

| Inverter-side inductor | L1 | [1 mH, 5 mH] |

| Grid-side inductor | L2 | [0.1 mH, 2 mH] |

| Filter capacitor | Cf | [10 μF, 20 μF] |

| Parameters | Resonant Point 1 | Resonant Point 2 | Resonant Point 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Magnitude | Frequency | Magnitude | Frequency | Magnitude | |

| D1 | None | Directly | None | Directly | None | Non-monotonic |

| D | Inversely | Inversely | Inversely | Inversely | Inversely | Directly |

| X | None | Inversely | Directly | Directly | Non-monotonic | None |

| KP | None | Directly | None | Non-monotonic | None | Directly |

| L1 | None | Directly | Inversely | Directly | None | None |

| L2 | Inversely | Inversely | Inversely | Directly | Inversely | Inversely |

| Cf | None | Inversely | Inversely | Directly | None | None |

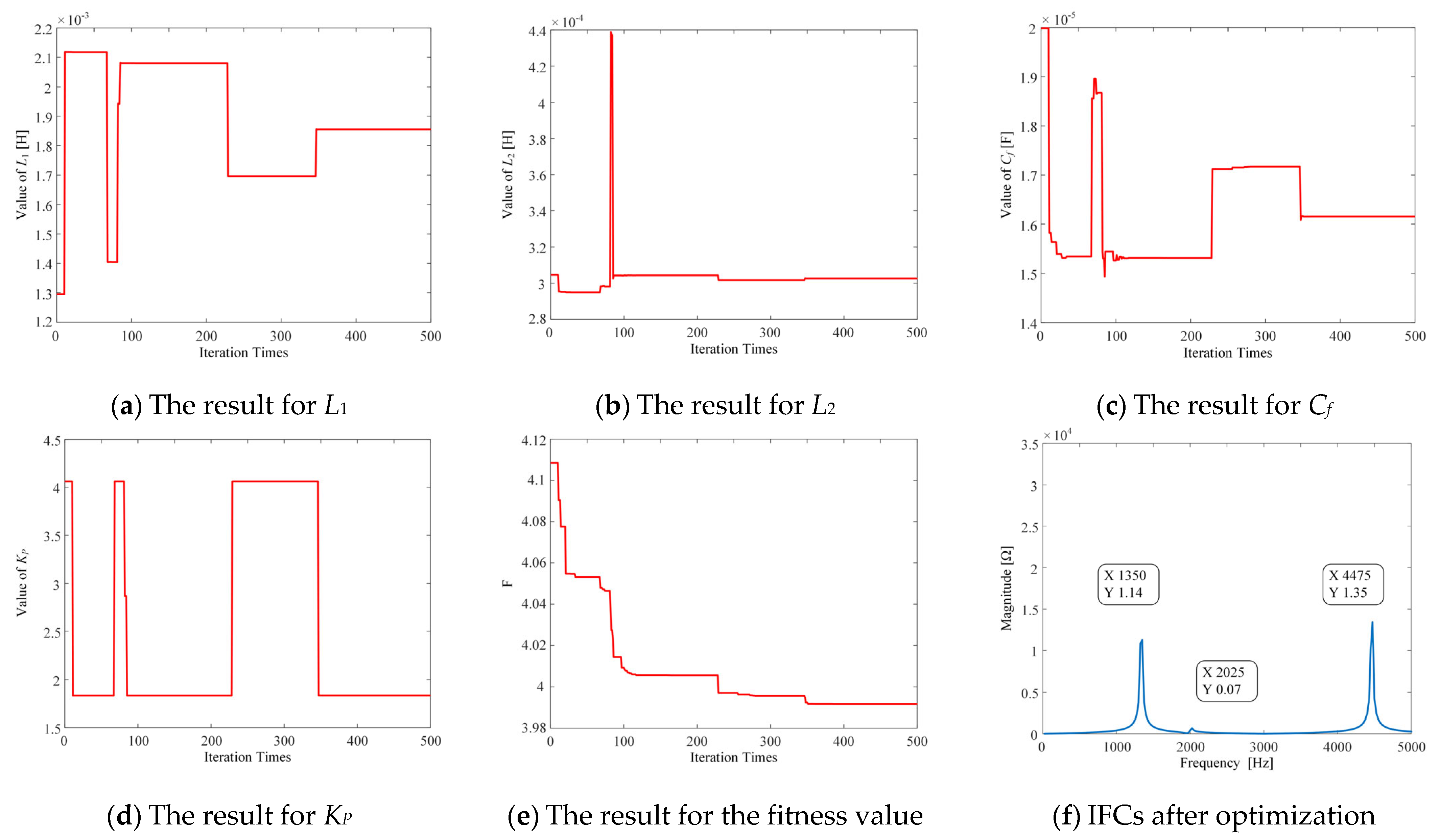

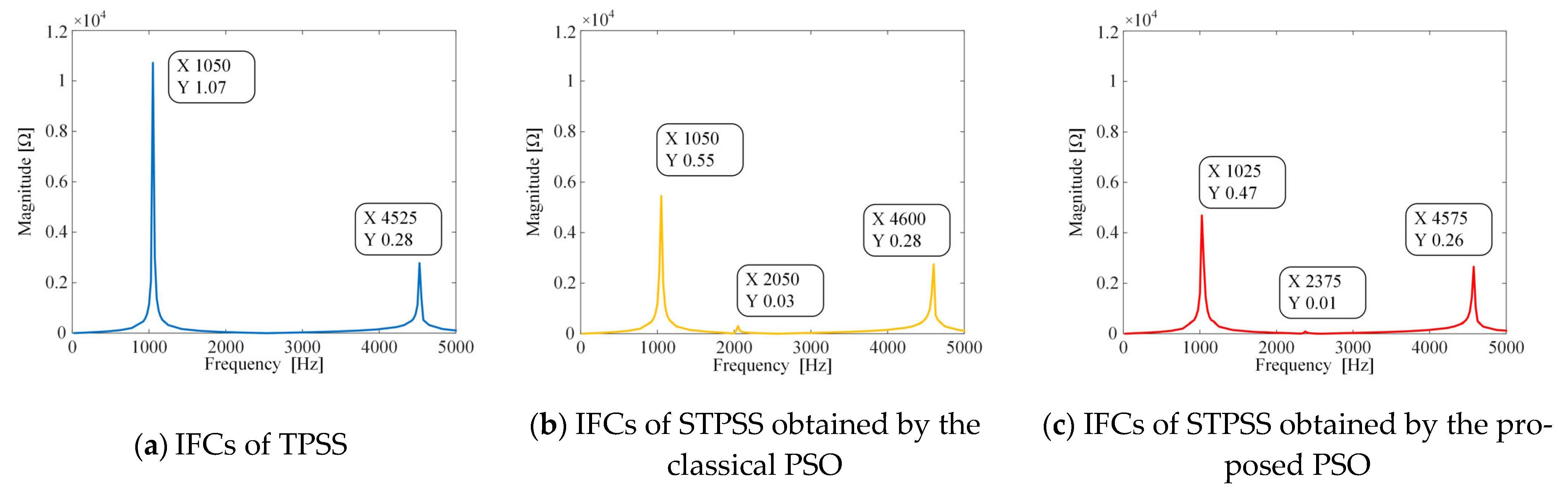

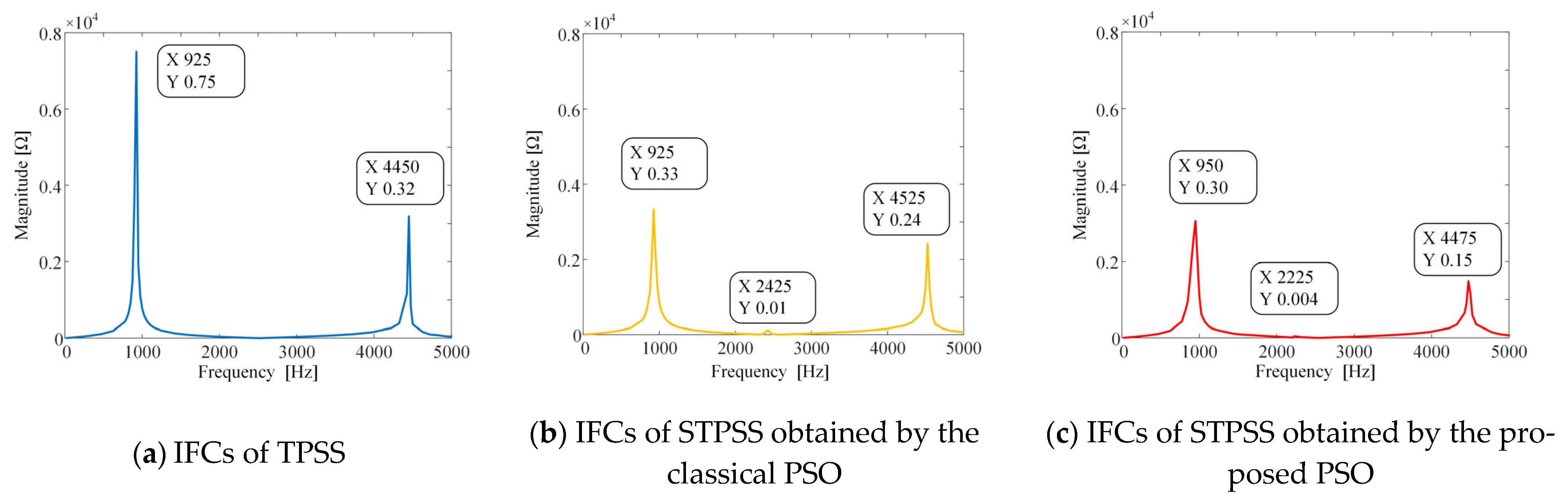

| Algorithm | L1 | L2 | Cf | KP | Iteration Times | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved PSO | 1.3 mH | 0.5 mH | 10μF | 2.96 | 120 | 3.65 |

| Classical PSO | 1.9 mH | 0.3 mH | 16μF | 1.83 | 350 | 3.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, P.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Cao, G.; Liu, Q.; Wu, M. Impedance Characteristics and Stability Enhancement of Sustainable Traction Power Supply System Integrated with Photovoltaic Power Generation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210055

Peng P, Zhang T, Yang X, Chen Y, Cao G, Liu Q, Wu M. Impedance Characteristics and Stability Enhancement of Sustainable Traction Power Supply System Integrated with Photovoltaic Power Generation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210055

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Peng, Tongxu Zhang, Xiangyan Yang, Yaozhen Chen, Guotao Cao, Qiujiang Liu, and Mingli Wu. 2025. "Impedance Characteristics and Stability Enhancement of Sustainable Traction Power Supply System Integrated with Photovoltaic Power Generation" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210055

APA StylePeng, P., Zhang, T., Yang, X., Chen, Y., Cao, G., Liu, Q., & Wu, M. (2025). Impedance Characteristics and Stability Enhancement of Sustainable Traction Power Supply System Integrated with Photovoltaic Power Generation. Sustainability, 17(22), 10055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210055