Social Practices for Climate Mitigation: A Big Data Analysis of Russia’s Environmental Online Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

- Materials: physical artifacts and infrastructure (e.g., for the practice of cycling—the availability of bicycles and bike lanes);

- Competence: skills and knowledge necessary to perform the practice (e.g., for cycling—the ability to ride a bike and awareness of routes);

- Meaning: symbolic and emotional aspects (e.g., for cycling—choosing a bicycle as an eco-friendly mode of transport).

3. Methods and Results

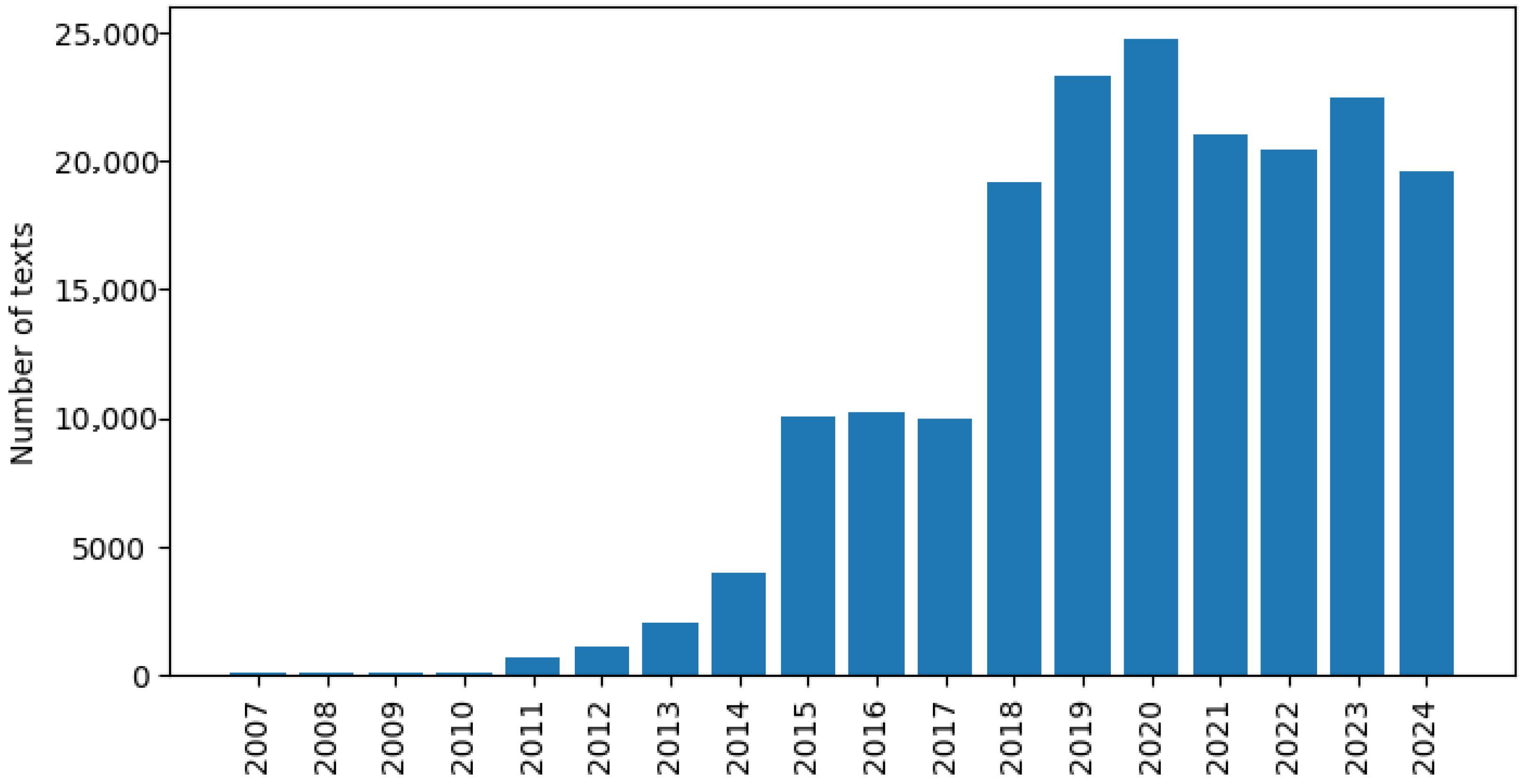

3.1. Data Collection

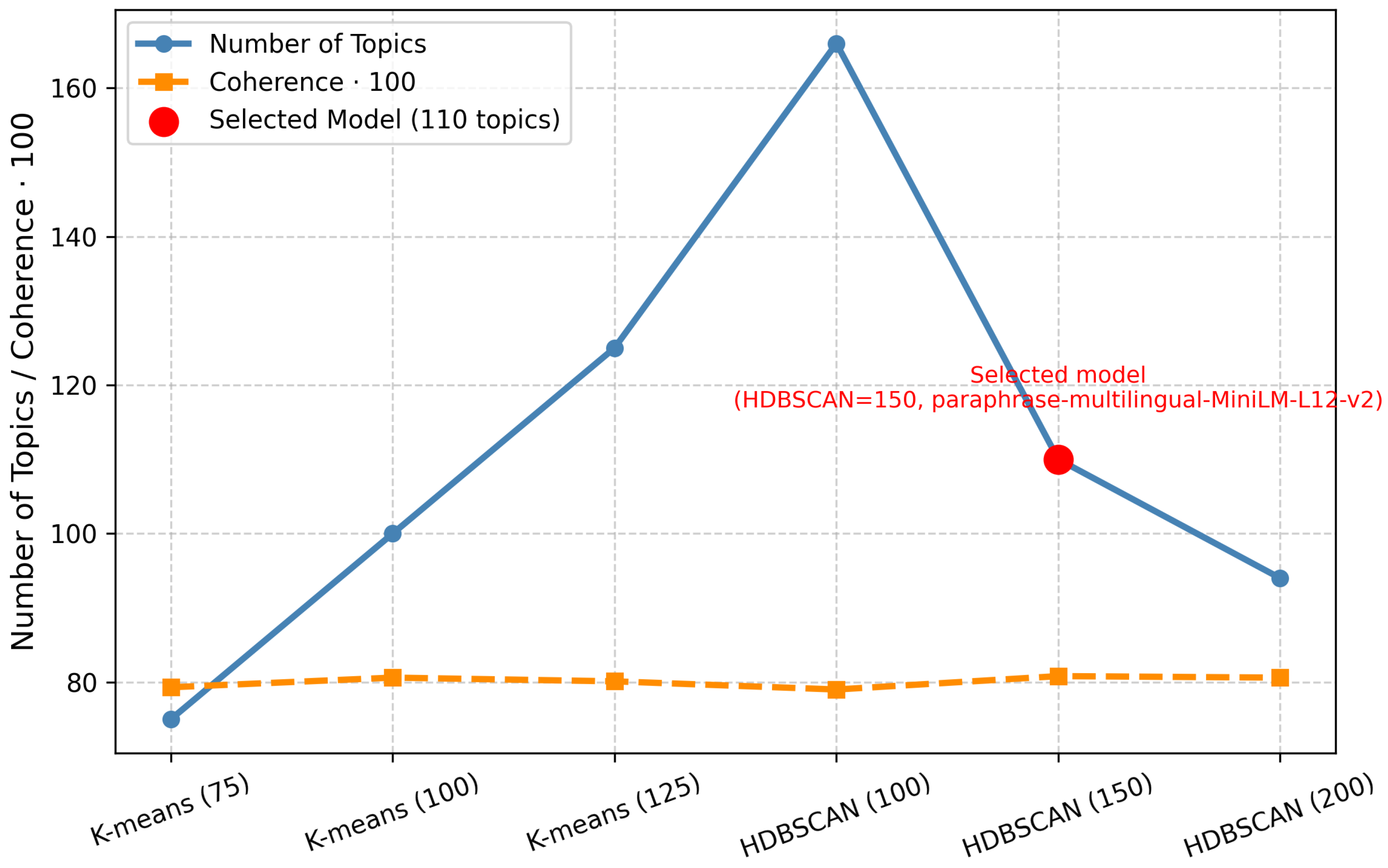

3.2. Topic Modeling

3.3. Analyzing Topics

- 1.

- Analyze the results of the topic modeling: keywords, examples.

- 2.

- Determine which social practices correspond to each topic.

- 3.

- Compile a list of social practices mentioned in the posts of environmental communities.

- 1.

- Actors of practices:

- Business (organizations, enterprises);

- The state (mentioned relatively infrequently);

- Public organizations, including NGOs, environmentally oriented movements.

- 2.

- Objects of practices:

- Forests (cultivating a caring attitude towards trees, organizing tree planting, engaging in planting initiatives);

- Stray animals;

- Household;

- Greening of the activities, products, and services of enterprises.

- 3.

- Informational and educational events:

- Event formats: lectures, webinars, informational forums, conferences, networking events (with and without discussion, unilateral information provision).

- Event focus: developing environmental thinking, responsibility, awareness; educating and informing about existing environmental practices, environmental problems, eco-tourism; promoting an eco-friendly lifestyle; promotional messages from company representatives offering eco-friendly goods and services; inciting public protests, primarily against company activities and the construction of infrastructure projects.

- 4.

- Educational initiatives of various orientations:

- For businesses, including environmental professionals and other decision-makers in the field of ecology;

- For employees of enterprises who are parents, to transmit eco-practices within families;

- For the general public.

- 5.

- Creation of digital maps containing environmentally significant information:

- Mapping specially protected natural areas and other green zones offering recreational opportunities and pedestrian trails;

- Mapping cycling routes to expand the use of eco-friendly transport;

- Mapping the locations of establishments implementing eco-practices (recycling and hazardous waste collection points, cafes, restaurants, animal shelters, package-free stores);

- Mapping pollution sources (executed by specialists from environmental organizations or volunteers; maps are created in Russian and foreign languages, making them accessible to tourists, foreign students, etc.).

- 6.

- Environmental competitions:

- For businesses;

- For the general public, including creatively oriented contests (photo, film creation).

- 7.

- Awarding environmental prizes:

- To businesses (organizations, enterprises);

- To individuals (volunteers, etc.).

- 8.

- Engaging people in eco-practices (recruitment), including:

- Recruiting participants from the public (i.e., volunteers, e.g., for forest planting initiatives);

- Recruiting staff—future employees for public environmental organizations themselves.

- 9.

- Fundraising:

- For aiding shelters for stray animals and protecting wildlife;

- For renting premises for eco-centers (indicating that this activity needs support from sponsors or state funding).

- 10.

- Practical activities involving active citizens and volunteers:

- Forest maintenance and tree planting;

- Clean-up campaigns;

- Separate waste collection: hazardous waste to minimize its release into the environment and the associated consequences; recyclable waste to ensure it is processed into useful products;

- Item exchange: toys, clothes.

- 11.

- Practices of refusal:

- Refusing a non-eco-friendly product in favor of another, more eco-friendly alternative;

- Refusing to purchase a product altogether.

- 12.

- The practices by companies, organizations, and enterprises in greening their activities and developing the ESG concept, including:

- Alternative energy;

- Circular economy, waste recycling: recycling household waste (commonly mentioned practices include recycling Christmas trees, plastic, including plastic collected from the ocean); recycling industrial waste;

- Creating and advertising environmentally improved products, including: products with objectively improved environmental aspects; pseudo-eco-friendly products (marketed as eco-friendly without sufficient grounds = greenwashing).

4. Discussion

4.1. Alignment with National Policy and Public Engagement

4.2. The Russian Context: Digital Compensation for Institutional Deficit

4.3. Systemic Interventions and Practice Interconnections

4.4. Verification of Hypotheses on Practice Domains and Discourse

4.5. Policy Implications and Pathways for Institutional Uptake

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- Public authorities can systematically integrate the identified, publicly-supported social practices into formal climate adaptation and mitigation strategies. This involves recognizing these grassroots actions as viable, ready-made policy instruments that have already gained traction within the population.

- 2.

- Public authorities should leverage online communities as strategic communication and engagement channels to promote climate policy measures, co-create solutions, and mobilize public participation on a large scale, thereby enhancing the legitimacy and reach of state-led initiatives.

- 3.

- Policymaking processes for climate action should formally incorporate activists and representatives from influential environmental online communities. Their involvement in discussions and decision-making can bridge the gap between institutional policy design and grassroots realities, fostering a sense of ownership and increasing the likelihood of public acceptance.

- 4.

- Funding mechanisms within national and regional climate programs should be allocated to support events and projects organized by these online communities. Providing material support for proven, community-driven initiatives represents a high-impact investment for implementing tangible climate actions and building social capital.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID | Topic Label | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Current Focuses of Environmental Policy | plastic, plastics, bag, bottle, plastic, packaging, recycling, paper, labeling, single-use |

| 1 | Attitude Toward the Environmental Agenda | USA, Russia, China, politics, international, country, security, military, attitude, report |

| 2 | Eco-Lifestyle and Positive Connections | thank you, our friend, person, everything, this, entire, very, done, more |

| 3 | Job Ads and Vacancies Related to the ESG Agenda | district, Mon, further, access, st., Fri, Mon–Fri, Fri access, Mon–Fri access, closed employee |

| 4 | Environmental Volunteer Campaigns | shore, volunteer, camp, lake, project, trash, cleanup, Vuoksa, clean, trail |

| 5 | Eco-Education and Environmental Awareness | school, lesson, environmental, child, kids, project, class, waste, schoolchild, collection |

| 6 | Solving Waste Problems from Households and Companies | waste, garbage, container, recycling, site, container-related, MSW (municipal solid waste), collection, landfill, container site |

| 7 | Announcements of Initiatives and Competitions in Environmental Volunteering | volunteer, campaign, recyclables, this, all, point, Yarekomobil, thanks, help |

| 8 | Environmental Volunteering | bottle cap, kindergarten, thanks, school, kindergarten, child, cap charity, child, charity, parent |

| 9 | Protection of Birds and Animals Bred for Fur | bird, feeder, animal, species, chick, feathered, nest, this, which, inhabit |

| 10 | Environmental Software Products | game, clean game, clean, cup, cleanliness cup, trash, team, cleanliness, participant, complete |

| 11 | Eco-Friendly Approach to New Year Celebrations | New Year, gift, New Year’s, year, new, holiday, December, eco-friendly, friend, our |

| 12 | Educational and Practical Events on Forest Protection and Reforestation | planting, forest, to plant, tree, plant-a-forest, plant the forest, forest-related, agro-care, planting project, forest planting project |

| 13 | Environmental Optimization of Transport Logistics | electric car, automobile, km, electric, transport, bus, e-bus, company, charging, electric vehicle |

| 14 | Environmental Research and Volunteering in the Arctic and Antarctic | Arctic, expedition, Arctic, island, green Arctic, volunteer, northern, Arctic volunteer, polar, year |

| 15 | Environmental Optimization of the Fashion Industry | clothing, item, fashion, fabric, textile, recycling, wardrobe, which, collection, brand |

| 16 | Protection of Domestic and Wild Animals | dog, shelter, animal, stray, stray animal, pet, cat, help, food, owner |

| 17 | Waste from Household Appliances | battery, accumulator, battery collection, used, disposal, recycling, collection, container, MegapolisResource, hazardous |

| 18 | Environmental Advertising | price, sell, DM (direct message), rub, size, storage room, price rub, question DM, DM sell, delivery |

| 19 | Vegan and Eco-Friendly Catering Establishments | meat, product, food, plant-based, vegetarian, dish, vegetarianism, vegan, nutrition, restaurant |

| 20 | ESG-Themed Conferences | forum, environmental, project, development, Moscow, Russia, ecology, event, organization, participant |

| 21 | Emissions of Pollutants into Atmospheric Air | air, pollution, air pollution, city, emission, substance, atmosphere, enterprise, atmospheric, concentration |

| 22 | Problems of Pollution and Conservation of Water Resources | water, river, water-related, pollution, reservoir, drinking, drinking water, purification, can, water resource |

| 23 | Innovations in Legislation and Practice of Waste Management in Russia | waste, garbage, separate, collection, separate collection, Russia, recycling, year, landfill, region |

| 24 | Documentary Films on Environmental Topics | film, documentary, director, cinema, festival, documentary film, planet, world, which, screening |

| 25 | Climate Change and Related Business Transformation | climate, change, climate change, climatic, warming, global, global warming, temperature, consequence, gas |

| 26 | Changes in Environmental Practices During the Coronavirus Pandemic | coronavirus, vaccine, virus, pandemic, vaccination, human, inoculation, infection, case, disease |

| 27 | Book Exchanges Involving Libraries and the Public | book, book-related, library, auction, literature, storage room, bookcrossing, rural library, lot, our |

| 28 | Online Resources on Waste Management | nicotine, unique component, unique component spray, addiction harmful to health, formula helps quickly, addiction harm, health harm detailed, combined special, quick easy to quit, nicotine addiction harm |

| 29 | Item Exchange | album, album of new things accumulated, show off new things, house full of unnecessary items, ready to give away kindly, dress up and show off, dress up and show off new things, items ready to give away, album accumulated house, message admin |

| 30 | Event Ads for Item Exchange | arrival, clothes, item, pillowcase, storage room, new arrival, new, campaign, arrival campaign, top |

| ID | Topic Label | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 31 | Gardening in the City or Apartment | plant, flower, leaf, seed, fruit, species, red, variety, this, look |

| 32 | Weekends, Holidays, and School Days | tomorrow, morning, good, good morning, weekend, day, sleep, cleanup day, week, today |

| 33 | Possible Joint Activities for Children and Parents | Qiwi, rub Qiwi Qiwi, send rub Qiwi, send rub, rub Qiwi, Qiwi Qiwi, Qiwi send rub, Qiwi Qiwi send, Qiwi send, send |

| 34 | Environmental Practices in the Music Industry | concert, song, music, Ecoloft, musical, dance, sing, evening, sound, verse |

| 35 | Environmental Contests for the Public | contest, winner, prize, raffle, participant, congratulate, result, gift, receive |

| 36 | Trend Toward Eco-Friendly Fashion | dress, size, clothing, sell, price, thousand, women’s, women’s clothing, new, DM |

| 37 | Ecology and Smartphones | phone, equipment, smartphone, electronic, sell, GB, price, electronics, device, headphones |

| 38 | Educational and Monitoring Initiatives on Forest Protection | fire, forest, forest fire, flame, grass, forest, burn, bonfire, firefighter, dry |

| 39 | Eco-Trails, Nature Reserves, and Parks | reserve, park, natural, territory, mountain, island, lake, national, located, place |

| 40 | Environmental Festivals for Business and the Public | festival, master, master class, class, eco-festival, eco, event, environmental, take place, program |

| 41 | Birthdays of Eco-Activists, Eco-Projects, and Eco-Friendly Birthdays | birthday, birth, day, congratulate, wish, protected, dzo, let, our birth |

| 42 | Microplastics in the Ocean | ocean, microplastic, plastic, plastics, microplastic particles, particle, marine, plastic, scientist, water |

| 43 | Examples of Solar Energy Projects | solar, panel, battery, solar battery, energy, power plant, solar panel, solar power plant, solar energy, capacity |

| 44 | Benefits of Trees and Forests for Humans | tree, forest, oak, trunk, forest planting, birch, grow, sequoia, fir |

| 45 | The Everyday Life of a Family: Children, Daily Routine, and Values | child, stroller, bottle cap, girl, mother, kind, family, pantry, treatment, money |

| 46 | Greening of Production and Human Lifestyle | separately, bottle, bag, plastic, accept, film, campaign, bank, labeling, paper |

| 47 | Motives and Components of an Eco-Friendly Lifestyle | ecology, eco-friendly, ecological, life, nature, environment, surrounding, surrounding environment, human |

| 48 | Online Store Advertising | album, arrival, item leaving home, item leaving, leaving home, admin Igor, Igor, admin, leave, home number card |

| 49 | Online Eco-Oriented Marathons | marathon, protected, task, team, Friends of the Protected Islands, Friends of the Protected Islands marathon, participant, friend, protected island |

| 50 | Worms Beneficial for Nature | worm, worms, vermicomposter, substrate, biohumus, box, vermicomposting, compost, little worm, feed |

| 51 | Art and Ecology | artist, art, sculpture, painting, art, work, create, female artist, trash, own |

| 52 | Photography and Ecology | photography, photographer, photo, photoshoot, photo session, photo contest, album, frame, shooting |

| 53 | Environmental Awards | award, nomination, eco-positive, application, ecological, contest, project, eco-positive award, winner, year |

| 54 | Eco-Friendly New Year’s Tree | fir, New Year, tree, fir, woodchip, New Year tree, little fir, artificial, January, living |

| 55 | Protest Environmental Actions and Clean-Up Campaigns | action, sale, pantry, Sunday, clothes shoes, point, clothes, remotely, store location, shoes |

| 56 | Eco Practices in Coffee Shops | coffee, tea, cup, coffee-related, coffee shop, sachet, tea-related, cup, drink, disposable |

| 57 | Educational Environmental Events | nature, planet, human, our planet, Earth, protect, everything, life |

| 58 | Various Forms of Public Opinion Expression on Environmental Issues | clean, movement, Tatarstan, Clean movement, ecological, republican, republic, Republic of Tatarstan, willbecleantatarstan, ecological movement |

| 59 | Protection of Cetaceans, Including Dolphins | whale, dolphin, marine, mammal, shark, animal, marine mammal, whale-related, sea, species |

| 60 | Cycling Movement in Cities as an Eco-Friendly Practice | bicycle, cycling, transport, city, cyclist, car, bike ride, car day, day, movement |

| ID | Topic Label | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 61 | Volunteer Actions on Ecology and Health Topics | volunteer, Perm, recruitment, event, date time, date, volunteer age, number of volunteers, time commitment, commitment |

| 62 | Environmental Videos | video, clip, this video, watch, this, clip, video clip, our video, watch |

| 63 | Job Vacancies Related to Corporate Image and Recycling | work, vacancy, hour, schedule, side job, required, collector, day, hours per day, work |

| 64 | Fish Resources | fish, salmon, Rybinsk, river, marine, water, Sakhalin, fisherman, sea, species |

| 65 | Environmental Initiatives of Service Sector Companies and Recycling from the Population | lamp, mercury, mercury-containing, thermometer, LED, light bulb, dangerous, mercury-containing, energy-saving, hazardous waste |

| 66 | Forest Protection and Reforestation | forest, logging, tree, forest-related, deforestation, climate, tropical, ecosystem, gas, soil |

| 67 | Eco Practices and Innovations in the Lifecycle of Footwear | shoes, sneaker, pair, sole, recycle, material, old, recycling, old shoes, company |

| 68 | Protection of Wild Bears | bear, polar bear, white, cub, animal, polar bear, polar, female bear, brown, brown bear |

| 69 | Announcements on the Schedule of Environmental Initiatives | point, work, schedule, Lysva, work point, Tselinny, street, work, mode, work schedule |

| 70 | Growth of Green Energy, Green Jobs Boom, and Workforce Shortages | energy, renewable, source, energy source, renewable source, energy sector, electricity, renewable energy source, solar, geothermal |

| 71 | Results of Recycling Activities | kg, rubles, campaign, paper, glass, recyclables, thank, glass kg, kg glass, LLC |

| 72 | Robots Helping Solve Environmental Problems | robot, drone, unmanned, airplane, company, UAV, device, flight, assistance, capable |

| 73 | Eco-Friendly Healthcare | medicine, drug, expired, pill, blister, expired medicine, medication, disease, doctor, first aid kit |

| 74 | Searching for and Purchasing Eco-Friendly Goods | album, dress up and show off new items, album accumulates at home, show off new items album, new items album, new items album accumulates, task to write admin, show off new items, accumulates at home unused, ready to give kindly |

| 75 | Eco-Friendly Approach to Children’s Toys | toy, child, children, doll, material, children’s toy, exchange, item, develop, play |

| 76 | Loyalty to Cats and Support for Cat Cafés | cat, kitty, kitten, shelter, cat café, animal, feline, scratching post, bed |

| 77 | Litter on Earth and in Space | space-related, space, space debris, orbit, satellite, Mars, astronaut, Earth, trash, flight |

| 78 | Environmental Protest Actions and Their Consequences | rally, against, protest, activist, construction, picket, resident, landfill, region, Shies |

| 79 | Recommendations and Practical Actions by Producers and Consumers to Reduce Carbon Footprint | carbon, carbon footprint, footprint, emissions, gas, greenhouse, company, calculator, compensate, own carbon |

| 80 | Climate Change and Glaciers | glacier, ice, melting, glacier melting, Arctic, icy, Antarctica, scientist, year, change |

| 81 | Results of Environmental Volunteer Actions | ruble, amount, donation, money, contribution, collection, subscription, campaign, assistance |

| 82 | Eco Practices: Furniture Recycling and Use of Eco-Bags | bag, furniture, chair, IKEA, bag, old, string bag, eco bag, banner, material |

| 83 | Sustainable Development and Greening Activities of Regions and Companies | Russia, ecological, year, ecology, Russian, year ecology, rating, Moscow, environment, surrounding environment |

| 84 | Educational Environmental Initiatives and Green Marketing Services | eco-labeling, product, greenwashing, product, eco-friendly, sign, packaging, production, ecological, labeling |

| 85 | Eco-Friendly Practices in Winter | snow, winter, winter project, winter, snowy, winter project BBT, BBT, project BBT, Baikal, ice |

| 86 | Problems in Protecting Citizens’ Environmental Rights | violation, district, landfill, urban district, plot, control, waste, land, Solnechnogorsk, land plot |

| 87 | Environmentally-Oriented Educational Programs and University Competitions | school, teacher, USE (Unified State Exam) exam, education, exam, Russian, training, university, language, student |

| 88 | Opportunities of Wind Energy | wind-related, wind, turbine, blade, wind generator, energy, power station, windmill, wind turbine, wind power station |

| 89 | Holidays Related to Environmental Activities | day, Earth Day, Earth, worldwide, surrounding, planet, holiday, environment, World Day, environment |

| 90 | Social Advertising for Nature Protection | advertisement, social advertisement, poster, social, promotional, clip, billboard, nature, which, this |

| ID | Topic Label | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 91 | Eco-friendly Transport and Safe Urban Mobility | street point, location, person, travel, route, street, arrival, long-distance travel, come, starting point |

| 92 | Campaigns of Environmental Volunteer Centers | curator, campaign, point, street, separator, microdistrict, district, coordinator, eco center, square |

| 93 | Airlines: Harm of Activities and Its Compensation | oil, gas, infographic, energy sector, coal, airplane, emissions, energy infographic, EU, fuel |

| 94 | Communication with Internet Audience | news, question, column, post, group, subscribe, newsletter, community, your |

| 95 | Remote Work and Labor Trends in Russia | Russian, Russia, Russian, pandemic, year, salary, person, benefit, company, Snowden |

| 96 | Holidays Related to Volunteers and Philanthropists | day, holiday, Russia, congratulate, Russia Day, year, celebrated, country, all |

| 97 | Harm of Balloons to the Environment | air, balloons, balloon, air balloons, small balloon, air balloon, launch, sky, graduation, celebration |

| 98 | Humor on the Topic of Studying | humor, joke, comic, sound humor, stand-up, laughter, Ecoloft, eco humor, minute, real laboratory |

| 99 | Nature in Different Seasons | snowdrop, spring, autumn, day, spring-related, flower, forest planting, snowdrop day, April, winter |

| 100 | Harm of Cigarette Butts to the Environment | cigarette, butt, tobacco, cigarette-related, e-cigarette, smoking, tobacco-related, filter, electronic, alcohol tobacco |

| 101 | Giving a Second Life to Unnecessary Items or Waste | arrival, children’s arrival, new children’s arrival, new children’s, new, children, children’s arrival world, arrival world, buy item leaving, can buy item |

| 102 | Eco-Friendly House Construction | house, building, roof, wooden, architect, build, construction, wood, material, domed |

| 103 | Eco-Friendliness of Toothbrushes | brush, tooth, toothbrush, toothpaste, tooth paste, tube, recycling, plastic, bristle, tooth |

| 104 | Eco-Friendly Agriculture | permaculture, farming, soil, farm, Holzer, farmstead, plant, harvest, organic, natural farming |

| 105 | Eco-Tourism | tourism, ecotourism, eco-tourism, tourist-related, tourist, nature, rural, local, trail, travel |

| 106 | Cooperation on Environmental Issues | expert, ecological, survey, platform, question, eco-project, own, project, community, your |

| 107 | Benefits of Bees | bee, honey, insect, bee-related, beekeeper, pesticide, pollination, plant, pollinator, beekeeping |

| 108 | Creativity Using Recyclables | master, masterclass, class, lighthouse, Darina, draw, sign up, registration, material, Ecoloft |

| 109 | Ecology and Transport | ecomobile, accept, bottle, packaging, transparent, container, labeling, route, vial, glass |

References

- Dubois, G.; Sovacool, B.; Aall, C.; Nilsson, M.; Barbier, C.; Herrmann, A.; Bruyère, S.; Andersson, C.; Skold, B.; Nadaud, F.; et al. It starts at home? Climate policies targeting household consumption and behavioral decisions are key to low-carbon futures. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 52, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Whitmarsh, L. Habit and climate change. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Creutzig, F.; Roy, J.; Lamb, W.F.; Azevedo, I.M.; Bruine de Bruin, W.; Dalkmann, H.; Edelenbosch, O.Y.; Geels, F.W.; Grubler, A.; Hepburn, C.; et al. Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creutzig, F.; Roy, J.; Devine-Wright, P.; Díaz-José, J.; Geels, F.W.; Grubler, A.; Maïzi, N.; Masane, E.; Mulugetta, Y.; Onyige, C.D.; et al. Demand, services and social aspects of mitigation (Chapter 5). In IPCC 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 503–612. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L.; Zhu, J.; Benson, D. Partnership building? Government-led NGO participation in China’s grassroots waste governance. Geoforum 2022, 137, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concari, A.; Kok, G.; Martens, P. Recycling behaviour: Mapping knowledge domain through bibliometrics and text mining. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upham, P.; Oltra, C.; Boso, À. Towards a cross-paradigmatic framework of the social acceptance of energy systems. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 8, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, P.; Boneva, T.; Chopra, F.; Falk, A. Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechezleprêtre, A.; Fabre, A.; Kruse, T.; Planterose, B.; Sanchez Chico, A.; Stantcheva, S. Fighting climate change: International attitudes toward climate policies. Am. Econ. Rev. 2025, 115, 1258–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretter, C.; Schulz, F. Public support for climate policies and its ideological predictors across countries of the Global North and Global South. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 233, 108603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Devine-Wright, P.; Mander, S.; Rowley, J.; Ryder, S. Realising a locally-embedded just transition: Sense of place, lived experience, and social perceptions of industrial decarbonisation in the United Kingdom. Glob. Environ. Change 2025, 94, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grechyna, D. Raising awareness of climate change: Nature, activists, politicians? Ecol. Econ. 2025, 227, 108374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Carbon capability revisited: Theoretical developments and empirical evidence. Glob. Environ. Change 2024, 87, 102895. [Google Scholar]

- Brodovskaya, E.; Dombrovskaya, A.; Karzubov, D. Digital communities of civil and political activists in Russia: Integration, governance and mobilization potential. Russ. Soc. Humanit. J. 2020, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parma, R. Engagement of Russian citizens in public participation online. Vestn. RFBR Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 5, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabanova, M. Ethical consumption as a sphere of Russian civil society: Factors and the development potential of market practices. Ekon. Sotsiologiya 2023, 24, 13–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsepilova, O.; Golbraih, V. Environmental activism: Resource mobilisation for “garbage” protests in Russia in 2018–2020. J. Sociol. Soc. Anthropol. 2020, 23, 136–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, O.; Glazkova, A. GreenRu: A Russian Dataset for Detecting Mentions of Green Practices in Social Media Posts. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedotova, A.; Kurtukova, A.; Romanov, A.; Shelupanov, A. Semantic clustering and transfer learning in social media texts authorship attribution. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 39783–39803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipari, F.; Lázaro-Touza, L.; Escribano, G.; Sánchez, Á.; Antonioni, A. When the design of climate policy meets public acceptance: An adaptive multiplex network model. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 217, 108084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, L.; Stagl, S.; Schemel, B. Social acceptance of climate policies: Insights from Austria. Ecol. Econ. 2025, 237, 108708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, C.; Bryant, P.; Corner, A.; Fankhauser, S.; Gouldson, A.; Whitmarsh, L.; Willis, R. Building a social mandate for climate action: Lessons from COVID-19. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebedeva, D. Boycotts and buycotts: Profiles of ecologically responsible consumers among Russian urban citizens. Monit. Public Opin. Econ. Soc. Changes 2025, 3, 108–133. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, R.A.; Wicki, M. What explains citizen support for transport policy? the roles of policy design, trust in government and proximity among Swiss citizens. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 75, 101973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazkova, A.; Zakharova, O. From Data to Grassroots Initiatives: Leveraging Transformer-Based Models for Detecting Green Practices in Social Media. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Ecology, Environment, and Natural Language Processing (NLP4Ecology2025), Tallinn, Estonia, 2 March 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zakharova, O.V.; Glazkova, A.V.; Pupysheva, I.N.; Kuznetsova, N.V. The importance of green practices to reduce consumption. Chang. Soc. Personal. 2022, 6, 884–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, O.; Glazkova, A. Green Waste Practices as Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Actions: Grassroots Initiatives in Russia. BRICS Law J. 2024, 11, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. VK—Leading Social Network in Russia by Users. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/13094/vk/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Hui, A.; Schatzki, T.R.; Shove, E. The Nexus of Practices: Connections, Constellations, Practitioners; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reckwitz, A. Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2002, 5, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E.; Watson, M.; Pantzar, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Laakso, S.; Niva, M.; Eranti, V.; Aapio, F. Reconfiguring everyday eating: Vegan Challenge discussions in social media. Food Cult. Soc. 2022, 25, 268–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkkeli, K.; Mäkelä, J.; Niva, M. Elements of practice in the analysis of auto-ethnographical cooking videos. J. Consum. Cult. 2020, 20, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E. Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Hanna, P.; Higham, J.; Cohen, S.; Hopkins, D. Can we fly less? Evaluating the ‘necessity’ of air travel. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2019, 81, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breadsell, J.K.; Eon, C.; Morrison, G.M. Understanding resource consumption in the home, community and society through behaviour and social practice theories. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, M. “People gather for stranger things, so why not this?” Learning sustainable sensibilities through communal garment-mending practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warde, A. The sociology of consumption: Its recent development. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, N.; Whitmarsh, L.; Capstick, S.; Hargreaves, T.; Poortinga, W.; Thomas, G.; Sautkina, E.; Xenias, D. Climate-relevant behavioral spillover and the potential contribution of social practice theory. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2017, 8, e481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Browne, A.; Evans, D.; Foden, M.; Hoolohan, C.; Sharp, L. Challenges and opportunities for re-framing resource use policy with practice theories: The change points approach. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 62, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A. Transport in transition: Doi moi and the consumption of cars and motorbikes in Hanoi. J. Consum. Cult. 2017, 17, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J. Modes of eating and phased routinisation: Insect-based food practices in the Netherlands. Sociology 2019, 53, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabin, S.; Haq, S.M.A. Linking social practice theories to the perceptions of green consumption: An overview. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J. Technologies within and beyond practices. In The Nexus of Practices; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cass, N.; Schwanen, T.; Shove, E. Infrastructures, intersections and societal transformations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 137, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulis, E.; Pilet, J.B.; Vittori, D.; Rojon, S. When climate assemblies call for stringent climate mitigation policies: Unlocking public acceptance or fighting a losing battle? Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 171, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancha-Hernandez, E.; Becerril-Viera, I. Learning from practice: Expanding the OECD’s impact evaluation criteria based on experiences of subnational climate assemblies in France, Spain and Portugal. Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 163, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durdovic, M.; Kolářová, M.; Čermák, D. Public resistance to climate policy amid energy crisis and populism: The case of the European Green Deal in the Czech Republic. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 123, 104033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabherwal, A.; Sparkman, G. A review of consistency in climate action: The role of social interactions and institutions in cultivating positive behavioral spillover. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2025, 61, 101475. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen, J.; Vatn, A.; Aasen, M. The chicken or the egg? Spillover between private climate action and climate policy support. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 99, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmel, K.; Klimova, A.; Mitrokhina, E. The politicization of environmental discourse in Arkhangelsk region: The landfill site at Shies railroad station. J. Soc. Policy Stud. 2020, 18, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- VTsIOM. Ecological Agenda: Ten Months Before the State Duma Elections (Analytical Report). Analytical Report, 2020. Available online: https://wciom.ru/analytical-reviews/analiticheskii-obzor/ehkologicheskaja-povestka-za-desjat-mesjacev-do-vyborov-v-gosdumu (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

- Mamaev, I.D.; Mitrofanova, O.A. Linguistic features for detecting hidden network communities. Terra Linguist. 2024, 55, 102–115. [Google Scholar]

- Koncha, V. BERT in focus: Topic modeling the transformation of collective identities of the participants of the Black Lives Matter movement in response to the counter-protest. Political Sci. 2025, 1, 219–239. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Frolov, A.; Agurova, A. Index analysis of active citizenship in social networks. Bull. Irkutsk. State Univ. Geoarchaeology, Ethnol. Anthropol. Ser. 2019, 29, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.R.; Wells, R.; Zollo, F.; Roche, J. Unpacking social media’engagement’: A practice theory approach to science on social media. J. Sci. Commun. 2024, 23, y02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanda, I.L.D.; Yang, M.; Shi, H.; Jiang, P. Leveraging natural language processing and community detection for shaping manufacturing communities in social manufacturing. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheddak, A.; Ait Baha, T.; Es-Saady, Y.; El Hajji, M.; Baslam, M. BERTopic for enhanced idea management and topic generation in Brainstorming Sessions. Information 2024, 15, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, W.; Bogaert, M.; Van den Poel, D. LLM-assisted topic reduction for BERTopic on social media data. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases (ECML PKDD 2025), Porto, Portugal, 15–19 September 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Karamolegkou, A.; Borah, A.; Cho, E.; Choudhury, S.R.; Galletti, M.; Ghosh, R.; Gupta, P.; Ignat, O.; Kargupta, P.; Kotonya, N.; et al. NLP for social good: A survey of challenges, opportunities, and responsible deployment. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.22327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D. Natural Language Processing for Social Good: Contributing to research and society. it-Inf. Technol. 2025, 67, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Korobov, M. Morphological analyzer and generator for Russian and Ukrainian languages. In International Conference on Analysis of Images, Social Networks and Texts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 320–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, S. NLTK: The natural language toolkit. In Proceedings of the COLING/ACL 2006 Interactive Presentation Sessions, Sydney, Australia, 17–18 July 2006; pp. 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Making Monolingual Sentence Embeddings Multilingual using Knowledge Distillation. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 4512–4525. [Google Scholar]

- Zmitrovich, D.; Abramov, A.; Kalmykov, A.; Kadulin, V.; Tikhonova, M.; Taktasheva, E.; Astafurov, D.; Baushenko, M.; Snegirev, A.; Shavrina, T.; et al. A Family of Pretrained Transformer Language Models for Russian. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), Torino, Italy, 20–25 May 2024; pp. 507–524. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, F.; Yang, Y.; Cer, D.; Arivazhagan, N.; Wang, W. Language-agnostic BERT Sentence Embedding. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 878–891. [Google Scholar]

- Shabanova, M. Separate waste collection as Russians’ voluntary practice: The dynamics, factors and potential. Sotsiologicheskie Issled. 2021, 9, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolaeva, Y.V. Problems of institutionalization of waste management in Russia. Amazon. Investig. 2018, 7, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Ermolaeva, P.; Basheva, O.; Korunova, V. Environmental policy and civic participation in Russian megacities: Achievements and challenges from the perspective of urban stakeholders. J. Soc. Policy Stud. 2021, 19, 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Russian Federation. Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of March 11, 2023. No. 559-r on the Approval of the National Action Plan for the Second Stage of Adaptation to Climate Change for the Period Until 2025. Official Document, 2023. Available online: http://static.government.ru/media/files/DzVPGlI7JgT7QYRoogphpW69KKQREGTB.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

| Practices (1–20) | Practices (21–40) | Practices (41–60) | Practices (61–80) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Advocating for a zero-waste lifestyle | 21. Developing environmental self-awareness | 41. Mapping environmental practices, including through volunteer efforts | 61. Promoting eco-goods (and pseudo-eco-goods) |

| 2. Banning and restricting single-use plastic | 22. Developing green online platforms | 42. Mapping green and protected areas | 62. Promoting eco-responsible business |

| 3. Building an environmental culture | 23. Developing green urban reforms (including urban decarbonization) | 43. Mapping pollution sources | 63. Promoting eco-transport |

| 4. Caring for stray animals (cats, dogs) | 24. Engaging in tree planting initiatives | 44. Monitoring water pollution | 64. Promoting environmental responsibility |

| 5. Choosing eco-friendly purchases | 25. Exchanging items, toys, books | 45. Organizing eco-friendly holidays and Zero Waste events | 65. Promoting the Zero-Waste concept (refusing single-use products, using eco-friendly products) |

| 6. Cleaning Arctic zone of litter | 26. Feeding birds via feeders | 46. Organizing eco-networking events | 66. Protecting natural world objects |

| 7. Cleaning areas of litter and waste | 27. Fostering eco-responsibility | 47. Organizing environmental education | 67. Protesting against greenwashing |

| 8. Collecting hazardous waste for disposal (batteries, mercury thermometers, lamps) | 28. Greening production (manufacturing products from plastic waste) | 48. Organizing environmental education for enterprise employees | 68. Purchasing more eco-friendly goods |

| 9. Collecting plastic caps for charity | 29. Greening the production and consumption of smart gadgets | 49. Organizing environmental education/lessons about nature reserves and parks | 69. Raising funds to help rare and endangered animal species |

| 10. Composting food waste | 30. Handing over electronics and batteries for recycling | 50. Organizing environmental festivals and competitions (e.g., video contests, volunteers helping birds) | 70. Raising money to rent premises for an eco-center |

| 11. Conducting environmental control and supervision activities | 31. Hiring staff for green jobs | 51. Organizing green offices | 71. Recycling Christmas trees |

| 12. Conducting workshops | 32. Implementing alternative energy sources | 52. Participating in eco-initiatives (art practices, tree planting) | 72. Recycling plastic waste from the ocean |

| 13. Creating circular production systems | 33. Implementing ESG strategies at enterprises | 53. Participating in protest actions | 73. Refusing balloon releases |

| 14. Creating cycling and pedestrian zones | 34. Informing about climate change | 54. Playing eco-games (computer, board, offline; for public and business consumers) | 74. Refusing single-use items (e.g., single-use tableware in favor of deposit-based reusable containers) |

| 15. Creating eco-friendly products (e.g., batteries) | 35. Informing about eco-routes | 55. Practicing vegetarian nutrition | 75. Repairing broken items (e.g., mobile phones) |

| 16. Cultivating a caring attitude towards trees | 36. Informing about memorable dates for eco-activists | 56. Promoting a sustainable lifestyle and eco-habits | 76. Screening and discussing environmental films |

| 17. Delivering informational environmental lectures | 37. Informing about the contribution of worms to nature conservation | 57. Promoting alternative energy | 77. Selling eco-goods |

| 18. Developing and implementing mobile apps for solving environmental problems (e.g., sorting plastic) | 38. Informing about the results of environmental research (on micro-pollution and mitigation methods) | 58. Promoting eco-expeditions / eco-travel | 78. Separating waste |

| 19. Developing eco-technologies | 39. Informing about the use of solar panels, wind turbines | 59. Promoting eco-friendly agriculture | 79. Studying product labeling |

| 20. Developing environmental research (studying pollution sources and cleanup solutions, climate and environmental research) | 40. Mapping cycling and pedestrian zones | 60. Promoting eco-friendly construction | 80. Teaching sustainable fashion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zakharova, O.; Prituzhalova, O.; Glazkova, A.; Suvorova, L. Social Practices for Climate Mitigation: A Big Data Analysis of Russia’s Environmental Online Communities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10053. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210053

Zakharova O, Prituzhalova O, Glazkova A, Suvorova L. Social Practices for Climate Mitigation: A Big Data Analysis of Russia’s Environmental Online Communities. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10053. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210053

Chicago/Turabian StyleZakharova, Olga, Olga Prituzhalova, Anna Glazkova, and Lyudmila Suvorova. 2025. "Social Practices for Climate Mitigation: A Big Data Analysis of Russia’s Environmental Online Communities" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10053. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210053

APA StyleZakharova, O., Prituzhalova, O., Glazkova, A., & Suvorova, L. (2025). Social Practices for Climate Mitigation: A Big Data Analysis of Russia’s Environmental Online Communities. Sustainability, 17(22), 10053. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210053