1. Introduction

Effective student classification is crucial for identifying and supporting students who face academic difficulties. Classification processes determine access to interventions, special education services, and individualized learning support [

1,

2]. However, international research has consistently shown that these systems often exhibit inconsistencies, biases, and structural challenges [

3,

4]. Framed within broader agendas for building resilient education systems, classification and its associated monitoring architecture serve as enabling mechanisms for achieving equitable, long-term improvement, particularly in relation to SDG 4 (inclusive and equitable quality education) and SDG 10 (reduced inequalities) [

5,

6]. Misclassification may result in either overrepresentation or underrepresentation of particular student groups, leading to inappropriate educational placements and long-term academic disadvantage [

7].

The importance of robust and equitable classification systems cannot be overstated. Classification schemes are not merely administrative mechanisms; they also function as gatekeepers to resources, support, and educational opportunities. When classification is flawed, students may be denied the necessary assistance or be directed into services that do not meet their actual needs. For instance, misidentification can exacerbate stigma, reduce student motivation, or entrench barriers to inclusion [

8]. In various contexts, scholars have documented that classification judgments are susceptible to subjective interpretations, contextual influences, and implicit bias [

4,

8]. From a systems perspective, these risks underscore the need for coherent evaluation and assessment frameworks, as well as responsible data stewardship, so that classification is defensible, transparent, and continually improvable over time [

9,

10].

Furthermore, classification systems may inadvertently reflect and reinforce social inequities. For example, studies in the United States have shown that race, gender, linguistic background, and school-level factors correlate with differential rates of special education placement, sometimes independently of students’ objective academic performance. In particular, implicit bias and structural pressures may lead to the overidentification of marginalized groups or the underidentification of others, resulting in disproportionality [

4,

11]. In terms of sustainable improvement, such disproportionality undermines equity commitments and signals governance gaps that require inclusive policy design and evidence-informed monitoring [

5,

6].

In educational systems worldwide, accurate and equitable classification has become increasingly important as schools strive to implement inclusive education frameworks that cater to the diverse needs of learners. Classification is not merely a technical process of labeling but is deeply intertwined with questions of equity, access, and resource allocation. Decisions about how students are classified have a significant impact on their educational trajectories, influencing the type and quality of support they receive and shaping broader institutional practices, including curriculum differentiation, teacher training, and policy development. Consequently, classification is both a pedagogical and a socio-political process that requires careful reflection and continual refinement. Aligning these processes with sustainable governance entails embedding them in continuous evaluation and feedback cycles, integrating them with national monitoring functions, and utilizing them to support adaptive capacity across schools [

9].

Building on these international frameworks, Qatar has made notable progress toward inclusive education by expanding access and aligning national priorities with global commitments such as the CRPD and SDG 4. However, translating these policy directions into everyday school practice remains uneven, reflecting systemic challenges that distinguish the Qatari context from other reform-driven education systems. This makes Qatar an important case for examining how inclusive governance frameworks operate when ambitious national reforms intersect with local capacity constraints and evolving cultural expectations.

The challenges associated with classification are further amplified in contexts undergoing rapid educational reform, such as the State of Qatar. In recent years, Qatar has prioritized inclusive education as part of its broader national education strategy, aligning with international frameworks such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [

12] and the Sustainable Development Goals [

5]. Indeed, Qatar has expanded the number of inclusive schools and integration programs across the system [

13]. However, translating policy commitments into consistent and high-quality practice has encountered obstacles related to infrastructure, professional capacity, resource allocation, and stakeholder buy-in. Within this evolving educational landscape, questions around the consistency, fairness, and effectiveness of student classification processes become particularly pressing. Situated within national planning priorities, including the Third Qatar National Development Strategy (2024–2030), these questions highlight the need to link inclusion reforms to long-term system capabilities and equitable service delivery [

14].

Moreover, research in the Qatari context has noted that support structures, diagnostic services, and accommodation provisions remain fragmented and unevenly distributed across schools and regions. Scholars have highlighted persistent gaps between policy and implementation, including limited coordination among educational, medical, and social service sectors, variation in teacher readiness for inclusive instruction, and uneven uptake of monitoring and evaluation practices [

15]. In sum, while Qatar has made commendable strides toward inclusion, systemic challenges remain that create fertile ground for misclassification, inconsistent monitoring, and inequitable outcomes. From a systems-improvement lens, these patterns indicate the need for integrated data systems and standardized monitoring protocols that reduce duplication, support resource optimization, and enable the longitudinal tracking of learners’ progress [

16].

Research has emphasized that classification cannot be fully understood without considering the voices of stakeholders directly involved in the process. Teachers, school leaders, special education coordinators, and policymakers play central roles in interpreting guidelines, applying criteria, and implementing monitoring systems. Their experiences, perceptions, and practices shape how classification policies are enacted in everyday school settings. Capturing these perspectives is therefore essential to understanding both the strengths and shortcomings of current systems and to identifying pathways for improvement. As a governance loop, structured stakeholder feedback supports adaptive policy, strengthens accountability, and enhances the resilience of inclusive schooling over time [

6,

9].

Given these complexities, examining stakeholder perspectives on student classification and progress monitoring in Qatari schools provides an important opportunity to contribute to global debates on inclusive education. It enables a nuanced understanding of how international challenges manifest in local contexts, while highlighting context-specific factors such as cultural norms, family engagement, and institutional resources. By examining these dynamics, this study aims to generate insights that inform local policy and practice and offer broader implications for countries seeking to enhance inclusive education systems. In line with the Sustainable Development Agenda, the analysis examines how classification and monitoring mechanisms can facilitate equitable and sustainable improvements consistent with SDG 4 commitments in rapidly reforming systems [

5,

6].

Qatar has undertaken substantial reforms in its education system, aiming to align with international standards while responding to local needs [

17,

18,

19]. However, despite policy advancements, there remain gaps in how students with academic difficulties are identified and supported in schools. Teachers, school leaders, parents, and support staff often encounter challenges related to referral procedures, diagnostic criteria, resource availability, and professional development [

18,

20]. Placing these challenges within a sustainability frame underscores the importance of capacity development, equitable resource distribution, and policy coherence across sectors so that classification and monitoring are not episodic acts but sustained, improvable practices embedded in routine functioning [

9,

14].

These challenges are significant in inclusive education contexts, where the classification of struggling students must balance the need for individualized support with the principles of equity and non-discrimination [

21]. In Qatar, although inclusion is a national priority, implementation varies across schools, and stakeholder voices are not always central to the policy-to-practice process. There is limited empirical research from the Qatari context that captures how key stakeholders, including teachers, school leaders, special educators, and parents, perceive the classification process and what improvements they deem necessary. In this context, qualitative insights can guide governance coherence, capacity-building, and data integration, ensuring that classification and progress monitoring operate as continuous, evidence-informed processes that advance SDG 4 commitments over time [

6,

9,

12].

The main issue in the current study is the gap between Qatar’s ambitious inclusive education policies and their inconsistent implementation. To analyse this gap, this study employs a theoretical framework that combines the principles of sustainable inclusive governance [

6,

9] with the theory of education system improvement [

22]. This framework provides an analytical lens for examining classification and monitoring systems across several interconnected dimensions.

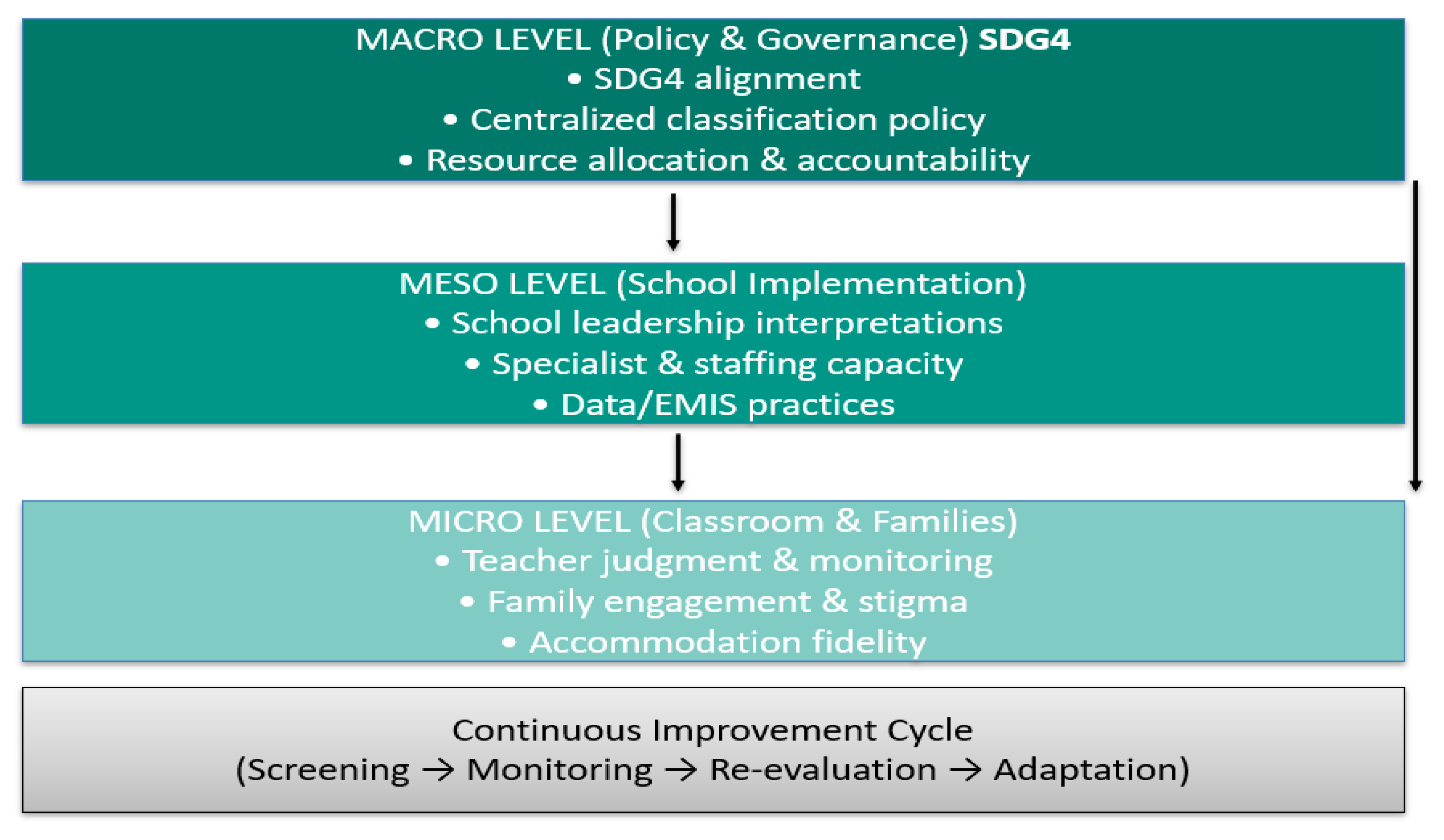

The concept of sustainable inclusive governance views inclusive education not simply as a set of isolated programs, but as an integrated system of practices, policies, and relationships. This framework emphasizes coordination and consistency across levels: ministry, school, and classroom, ensuring alignment between sustainable governance frameworks and SDG alignment (macro-level). It also addresses capacity building through equitable distribution of human and material resources, including specialists, training, data, coordination mechanisms, and professional capabilities (meso-level). Furthermore, accountability and data culture underscore the need to use data from monitoring systems to improve practices, moving beyond mere reporting. Finally, the focus is on stakeholder engagement, by involving teachers and families in the decision-making process (micro-level).

The theory of Improving Education Systems offers a practical overview of how policies can be translated into effective and sustainable practices on the ground [

22]. It highlights essential implementation components, including sustainable training, practical training (in-service training), and feedback. It also highlights implementation barriers, such as a lack of coordination between agencies (e.g., diagnostic centers and schools) or insufficient training in the use of monitoring tools.

This study employs this lens to understand the case of Qatar. Through this integrated framework, the challenges revealed by the study (such as reliance on external reports, fragmented monitoring systems, and lack of resources) can be interpreted not as isolated issues, but rather as indicators of weak governance coordination between diagnostic centers and schools, a capacity gap at the school level to implement continuous monitoring, and a weak data culture where data is not translated into improvement decisions.

Consequently, the classification and monitoring process in this study is not evaluated in isolation, but rather as a vital function within a broader educational governance system that seeks to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 4). Thus, guided by this framework, this study seeks to address that gap by exploring stakeholder perspectives through two key questions:

What challenges do stakeholders perceive in current practices of student classification for students with academic difficulties in Qatari schools, and how do these challenges affect the sustainability, equity, and resilience of inclusive education efforts aligned with SDG 4?

What specific improvements do stakeholders recommend to enhance these practices, with emphasis on data integration, governance coherence, and capacity-building that can support sustainable, system-wide implementation over time?

4. Findings

The thematic analysis of interview transcripts generated 817 initial codes, which were refined and consolidated into 213 final codes grouped into 16 subthemes under 6 overarching themes. These themes reflect stakeholders’ perspectives on student classification and progress monitoring in Qatari schools, including Classification Inconsistencies, Resource and Staff Shortages, Family Resistance and Collaboration, Policy and Accommodation Gaps, Fragmented Monitoring Systems, and Innovative Inclusive Practices. To guide the interpretation of these findings, a multi-level conceptual model was developed linking stakeholder perspectives to sustainable governance and system improvement across macro-, meso-, and micro-levels (

Figure 1), thereby establishing the analytic framework for organizing the results.

Table 1 presents the themes, subthemes, and representative example codes that emerged from the thematic analysis.

4.1. Classification Inconsistencies

Stakeholders raised substantial concerns about the consistency and reliability of the student classification system in Qatar, which an external center manages. As the national authority, this center diagnoses students and assigns them to one of three levels of support. While this centralized model is intended to standardize classification, participants reported that, in practice, the process is marked by inconsistencies and gaps. Participants explained that classifications often depend heavily on external reports from this center, which may not fully capture students’ day-to-day learning needs. Additionally, participants described how school-level practices varied significantly, with coordinators and administrators interpreting classifications differently across institutions. Finally, stakeholders highlighted persistent challenges with disability classification itself, noting unclear criteria, overlapping categories, and frequent difficulty distinguishing between learning difficulties, behavioral issues, and developmental conditions. The three emerging subthemes, reliance on external reports, variability in school-level practices, and challenges with disability classification, illustrate a system that lacks the flexibility, clarity, and iterative review necessary to ensure accurate, equitable, and educationally meaningful support over time. These findings illustrate that a centralized diagnostic policy (macro-level) creates a paper-based system that constrains teachers’ professional judgment (micro-level) in daily assessment. This relationship is shaped by coordinators’ different interpretations of reports (meso-level), leading to inconsistent practices across schools.

4.2. Reliance on External Reports

Stakeholders consistently emphasized that the classification system in Qatari schools remains heavily dependent on reports from external diagnostic centers, which are mandated to assess students and assign them to one of three levels of support. Although this centralized framework was initially intended to promote uniformity across schools, teachers and coordinators underscored that, in practice, it often produces rigid and sometimes inaccurate classifications. Reports were frequently characterized as superficial, repetitive, or disconnected from students’ lived realities regarding their academic and social functioning in the classroom. As one teacher expressed in frustration, “Sometimes we receive reports from X Center that look copy-pasted … you end up needing to sit with the student yourself to really understand their case.”

Participants highlight a broader tension between medicalized, external assessments and the context-specific insights educators acquire through their daily interactions with students. Several participants explained that while such reports provide diagnostic labels, they seldom include detailed recommendations that could guide instructional practice. As a result, schools are left with classification decisions that carry an air of authority but lack the actionable specificity needed to support teaching and learning. One participant was particularly critical of the descriptive limitations of these reports, observing, “The medical report is descriptive rather than quantitative … very brief, weak … we need the report to be more detailed, not just numbers.”

The reliance on external documentation was also seen as undermining educators’ professional role in the classification process. Teachers repeatedly conveyed that their classroom judgments and longitudinal observations were marginalized in favor of reports, even when the latter conflicted with the realities they observed. The result, as one coordinator put it, was a form of “paper diagnosis” in which classification decisions were determined more by documents than by nuanced understandings of student needs. One special education teacher explained the extent of this reliance, saying, “The medical reports … are the main criterion for classifying students in Qatar … as a teacher or as a member of the special education team … we have no authority to classify students except through this requirement.” Another participant reflected on the consequences of such dependence, noting that vague and generalized language within reports limited their practical value: “The language of the report is vague … and this causes many problems in accurately identifying student needs.”

While the classification framework in Qatar is highly structured, it risks reducing students to static categories rather than acknowledging their evolving learning trajectories. Without stronger integration between external assessments and school-based evaluations, classifications are likely to remain shallow, inflexible, and misaligned with educational needs. This concern was captured succinctly by a coordinator who stressed the disjunction between documentation and lived experience:

“Sometimes we read the medical report … and find that the report says one thing, but the reality is another … it was written that the student had autism … but from our two years of experience with him, we found otherwise.”

4.3. Variability in School-Level Practices

In addition to concerns about reliance on external reports, stakeholders highlighted inconsistent application of classification practices across schools. Although Qatar’s classification system is centralized in principle, participants emphasized that, in practice, considerable discretion is left to schools, coordinators, and individual teachers. This discretion creates considerable variability in how similar cases are assessed, classified, and supported across different institutions. Stakeholders described this situation as confusing for teachers and families and inequitable for students, as outcomes often depend on subjective judgments of school staff rather than a unified, consistently applied framework. One school leader explained this challenge succinctly: “Classification differs from one school to another … every coordinator interprets it according to their own experience.”

Educators observed that such variability was especially pronounced in cases involving autism spectrum disorder, where academic and behavioral functioning vary widely. Participants expressed concern that students with strong academic abilities were sometimes placed in the highest level of support simply because of their diagnosis, regardless of their actual performance. As one teacher noted: “Autism is always problematic … some cases are academically excellent but are classified straight into Level 3.” This observation highlights how institutional discretion, combined with the absence of nuanced criteria, can result in placements that do not accurately reflect students’ profiles or support needs.

Participants also underscored that inconsistencies extend beyond diagnostic interpretation to the everyday implementation of classification decisions. While some schools have developed flexible approaches to adapt classifications to student needs, others interpret them rigidly, limiting opportunities for integration and tailored support. One coordinator gave a striking example: “Sometimes two students with the same condition … in one school they classify one as ‘Classified Student’, and in another school they consider the other as ‘Regular’.” Such disparities suggest that classification is not only uneven but also shaped by institutional culture, coordinators’ training, and the resources available at each school. As a result, students may experience markedly different educational pathways despite having similar needs.

Another area of variability reported by participants concerned the lack of systematic follow-up to ensure that initial classifications remain accurate over time. Teachers and principals explained that once students are classified, they are often left in the same category for years without re-evaluation, even when their abilities or needs change. As one principal observed: “The student is classified at the beginning … but there is no follow-up or regular review to ensure the classification is accurate.” Such practices restrict the system’s adaptability and risk locking students into categories that no longer reflect their current capabilities.

4.4. Challenges with Disability Classification

A third issue that stakeholders repeatedly emphasized was the challenge of accurately classifying students with disabilities. Although Qatar’s system mandates that students be placed into three levels of support, participants argued that the criteria used to distinguish between disability categories remain unclear, inconsistently applied, and often misaligned with students’ complex learning profiles. Teachers, coordinators, and administrators consistently described classification decisions as confusing and prone to misinterpretation, with significant implications for the support students receive in schools.

Several stakeholders highlighted the difficulty of distinguishing between learning difficulties, slow learning, and developmental conditions such as autism. As one coordinator explained: “Sometimes a student is classified as having autism when he does not, and sometimes learning difficulties are mistaken for delayed or slow learning.” The absence of fine-grained diagnostic tools, as participants argued, results in overlapping categories where students are placed based on broad impressions rather than nuanced assessments. Another teacher described how such misclassification leaves students with inappropriate support plans: “You get a report saying the student has learning difficulties … but when you teach him, you realize he is normal; his problem is more behavioral.”

Educators also reflected on the consequences of inconsistent application of classification across schools and teams. One principal observed: “There are students who are classified as Level 3 … even though they could integrate with their peers … but because there are no clear criteria, they end up in the most restrictive level.” Another teacher highlighted how the rigid application of disability labels can obscure students’ strengths: “A student might be weak in reading but strong in mathematics … yet he is classified as having learning difficulties in general.”

Stakeholders further noted that inconsistent classification criteria across institutions contribute to parental resistance and confusion. Parents often question why their child is placed in a restrictive category in one school but considered “regular” in another. As one coordinator recounted: “Parents come to us saying: why is my son here, while in his old school he wasn’t.” These observations underscore the impact of unclear and inconsistently applied standards, which not only complicate educational planning but also strain communication between schools and families, reducing trust in the process and the likelihood of sustained, collaborative support.

4.5. Resource and Staff Shortages

Another central theme that emerged from stakeholder perspectives was the shortage of human and material resources required to implement and sustain the classification and progress-monitoring system at scale. Participants emphasized that, despite policy commitments to inclusion and equity, schools often lack the necessary specialists, manageable class sizes, and sufficient staffing to provide individualized support with fidelity. Teachers described how the absence of professionals, such as speech and occupational therapists, undermines the accuracy of student classification and longitudinal progress monitoring, limiting their capacity to design targeted interventions. Similarly, overcrowded classrooms and heavy teaching workloads were highlighted as barriers that prevent educators from giving students with learning difficulties the attention they require and from translating progress-monitoring data into instructional adjustments. The shortage of specialists not only reflects a systematic resource allocation deficit (macro-level) but also directly impacts the ability to implement individual interventions (micro-level). This scarcity places additional burdens on teachers and support teams in schools (meso-level) and strains already limited resources.

4.6. Lack of Specialists

Stakeholders repeatedly emphasized that one of the most critical barriers to implementing an effective classification and monitoring system in Qatari schools is the shortage of clinical, therapeutic, and behavioral specialists. Participants’ perceptions highlight a persistent service-delivery gap between classification outcomes and the support actually provided to students, driven by a shortage of specialists. While the national system identifies students and assigns them to levels of need, the absence of in-school professionals means that classifications often remain labels without evidence-informed, ongoing interventions and progress reviews. Teachers and coordinators described how the lack of experts in speech therapy, occupational therapy, and behavioral support leaves a gap between classification and practice, as students are diagnosed but not provided with timely, sustained services or documented in routine monitoring systems. One teacher pointed to this gap directly, noting the absence of professionals inside schools: “We classify the student, but we do not have the staff or tools to support him.” Another participant highlighted the specific absence of speech therapy services, which are essential for many students with communication difficulties: “We don’t have a speech therapist in the school … and the students who need sessions end up waiting or going outside.”

Similarly, a coordinator explained how occupational therapy, though vital for supporting motor and functional challenges, was not readily available: “The student needs occupational therapy … but this is not available in the school … in the end, he stays in class without receiving the service he needs,” resulting in delays and missed windows for early intervention. Beyond therapeutic specialists, participants also emphasized the importance of behavioral support staff in maintaining classroom-level feasibility and fidelity, particularly in inclusive settings where teachers struggle to manage diverse needs within large classrooms. One teacher explained: “If there were a behavioral specialist to support the teacher, it would make a big difference … right now the teacher faces everything alone.”

4.7. Overcrowded Classrooms

In addition to the shortage of specialists, stakeholders identified overcrowded classrooms as a significant barrier to effective classification and progress monitoring, as well as to the fidelity of accommodations. Teachers and coordinators described how large class sizes reduce opportunities for differentiated instruction and small-group support, making it challenging to address the diverse needs of students with learning difficulties. Even when students are accurately classified, the reality of overcrowded classrooms means that the recommended support often cannot be implemented with fidelity. One teacher explained the challenge directly: “The classrooms are overcrowded … I have more than thirty students … I can’t follow up on every student who has a difficulty.”

Stakeholders also emphasized that overcrowding influences teachers’ priorities, causing them to focus on curriculum pacing and coverage rather than providing differentiated instruction. A coordinator described how classroom density constrains flexibility: “The large number of students makes the teacher focus on finishing the curriculum … they cannot give extra time to the student who has difficulties.”

Further, participants reported that systemic pressure to complete curricular requirements leaves little room for individualized interventions, even when students’ needs are well documented, thereby weakening the validity of progress-monitoring data and hindering data-informed instruction. A school leader described how curriculum demands restrict teachers’ flexibility: “The student does not benefit from the material … the curriculum still needs to be more flexible, especially for students with disabilities.” Some participants further explained that the impact of overcrowding extends beyond the quality of teaching to students’ lived experiences. Students with learning difficulties often become less visible in formative data and classroom routines, where the sheer number of peers overshadows their struggles. As one teacher reflected, students who require additional support may be left behind: “The student who needs special follow-up is not visible among 30 or 35 students … he gets lost in the crowd.”

Administrators also echoed these concerns, noting that overcrowded classrooms compound other resource shortages and staffing constraints. Without teaching assistants or specialists, teachers are left to manage academic, behavioral, and social needs simultaneously, an unsustainable arrangement that further reduces routine, documented monitoring of students with difficulties. One principal observed: “In overcrowded classes, the teacher is more occupied with management than teaching … and as a result, monitoring students with difficulties is almost non-existent.”

4.8. Teacher Workload

Stakeholders emphasized that excessive teacher workload is a significant barrier to effective classification and progress monitoring, as well as to translating data into effective instructional practice. Teachers and coordinators explained that the combination of full teaching schedules, large numbers of students, and the responsibility of managing multiple individualized education plans (IEPs) and associated paperwork often leaves little time for meaningful follow-up or co-planning with specialists. Even when classifications are accurate and progress-monitoring tools are available, the practical demands of everyday teaching make it difficult for educators to implement individualized interventions with sufficient intensity and continuity. One teacher described this burden explicitly: “The teacher has many classes and individual plans … the daily pressure makes it difficult to follow up on every student with a difficulty.”

Stakeholders also reflected on how workload pressures affect the quality of progress monitoring. Teachers often complete required forms and reports, but the process can become compliance-oriented rather than genuinely reflective of student progress, resulting in ‘paper progress’ without corresponding classroom change. A coordinator explained: “The teacher fills in the report … but does not have time to apply the strategies or follow up daily … the work has become more paperwork than practice.” In addition, participants noted that the demands of preparing lessons, grading assignments, managing classroom behavior, and entering/analyzing monitoring data often compete with the time required for monitoring students with learning difficulties. One principal summarized the problem by highlighting the tension between teaching responsibilities and support duties: “The teacher is required to finish the curriculum, grade papers, and prepare lessons … on top of that, they have students needing special follow-up.”

Teachers further reported that the cumulative effect of these pressures can lead to emotional strain and an increased risk of burnout, resulting in feelings of frustration and a decline in motivation. A participant noted that while many teachers are committed to inclusion, the workload often makes them feel unsupported: “We want to support students … but without support or a reduction in workload, the teacher feels like they are working alone.”

4.9. Family Resistance and Collaboration

A further theme that emerged from stakeholder perspectives was the role of families in supporting or hindering the classification and progress-monitoring process, as well as in follow-through on support plans and monitoring routines. Participants consistently highlighted how parents’ attitudes, beliefs, and levels of engagement shape the implementation of inclusive education in schools and influence whether monitoring data are used to adjust instruction. On one hand, educators reported encountering parental denial, stigma, and resistance, particularly when children were identified as needing a Level 3 of support. On the other hand, several teachers and coordinators shared positive examples of parents who collaborated closely with schools, engaged in daily communication, reinforced strategies at home, and shared observations/data with teachers. These dual perspectives highlight the complexity of family involvement, where resistance can create significant barriers to accessing practical support and timely services. At the same time, collaboration can enhance both classification accuracy and student progress by strengthening home–school feedback loops. The subthemes of denial and stigma, as well as positive engagement, capture this dual role of families within the inclusive education system in Qatar in day-to-day implementation. Parental resistance is rooted not only in cultural and social beliefs at the (macro level). However, it is also reinforced by ineffective institutional communication from the school (meso-level) and by the inability of overburdened teachers (micro-level) to gain their trust and explain the process effectively.

4.10. Denial and Stigma

Stakeholders consistently emphasized that parental denial and the stigma surrounding special education present some of the most challenging barriers to effective classification and monitoring (including accommodations) in Qatari schools. Teachers, coordinators, and administrators explained that even when students display clear signs of learning or behavioral difficulties, many families refuse to acknowledge the problem. This resistance is particularly acute when placement in Level 3 is recommended, as parents often fear the label will negatively affect their child’s educational and social trajectory. One coordinator described this recurring challenge: “Some parents reject the idea of classification … they say there is nothing wrong with their child.”

Educators frequently connected this denial to broader cultural stigmas. Parents were described as fearing not only the label of “special education” but also the potential for their child to be viewed as less capable within the community. One teacher explained: “There are parents who are afraid of the term ‘Disability’ … they consider it a shame or stigma … and so they refuse to cooperate.” Another participant elaborated that this refusal is not simply emotional but strategic, as parents worry about the long-term consequences of having their child formally identified (e.g., perceived future placement limits or social stigma): “Sometimes when we tell parents that the student is placed in Level 3 … they completely refuse … they fear it will affect their future or how others perceive them.”

Teachers noted that such resistance complicates the development of IEPs or the creation of monitoring tools, as schools cannot proceed without parental consent and data-sharing permissions. One teacher expressed the frustration of this impasse: “We see that the student has clear difficulties … but the parents refuse classification … and we cannot complete the procedures without their approval.” Some educators further explained that parental denial not only delays access to services but also places additional strain on teachers, who must continue supporting students without the formal resources typically associated with classification. In such cases, teachers described relying on informal strategies while waiting for parental acceptance and documenting classroom observations to maintain a record of need. A coordinator described the mismatch between what schools observe and what parents are willing to admit: “Parents insist their child is excellent … while we see he has problems in reading and writing … this contradiction delays everything and interrupts early-intervention services.”

4.11. Positive Engagement

While many participants discussed denial and stigma, others shared encouraging examples of families that actively collaborate with schools to support classification and progress monitoring. Stakeholders emphasized that when parents engage constructively, they become critical partners in ensuring that classifications are accurate and interventions are implemented with fidelity and meaning. Positive family engagement was described as including daily communication with teachers, reinforcement of strategies at home, and active participation in meetings and IEPs (including timely consent for services and information sharing). One coordinator highlighted how cooperative families can ease the entire classification process: “When parents are cooperative … the procedures move much faster … the student receives the services they need without delay and services start earlier.”

Teachers also reflected on how parent engagement enhances progress monitoring by providing insights from outside the classroom (e.g., homework behaviors, home routines, and peer/sibling interactions). Parents who share observations from home help teachers gain a fuller understanding of students’ strengths and difficulties. One teacher explained: “The mother communicates with us almost daily … she tells us how her son handles homework or interacts with his siblings … this helps us understand more and adjust plans between reviews.” Another participant described how fathers, in particular, can play a crucial role when they are actively involved in follow-through and logistics: “There was a father who came himself every day to follow up with us … even the father became part of the plan … and that made a big difference for the student.”

Stakeholders emphasized that family engagement benefits students, fosters trust, and facilitates smoother collaboration between schools and households, as well as more consistent data sharing. When parents openly acknowledge their child’s difficulties, schools are better equipped to apply inclusive frameworks effectively and adjust interventions over time as part of a continuous monitoring cycle. A principal explained: “When parents acknowledge the problem and cooperate … we can work as one team … and the results appear quickly and are sustained over time.” Participants also noted that collaborative families often advocate for more resources or specific accommodations, prompting schools to provide additional support. A coordinator recalled one such case: “A mother always asked and requested curriculum adaptations … and this made us think of new ways to suit the student and to document adaptations in monitoring records.” These examples reveal how parental collaboration functions as a facilitator within the classification and monitoring system, counterbalancing the barriers created by denial and stigma.

4.12. Policy and Accommodation Gaps

Another theme that emerged strongly from stakeholder perspectives concerns the gaps between national policy frameworks and the accommodations actually available in schools. While Qatar has taken steps toward standardizing classification and promoting inclusive education, participants emphasized that policies are often fragmented or inconsistently applied at the point of implementation. Stakeholders described how the lack of a unified framework leads to confusion in schools, with different institutions applying classification and monitoring criteria in divergent ways and with varying levels of oversight and training. Teachers and coordinators also noted that accommodations for students with learning difficulties are often limited to granting extra time. At the same time, more substantial adjustments to the curriculum or assessment practices are rarely permitted (e.g., alternative formats, read-aloud/scribing, assistive technology, flexible scheduling, or task redesign grounded in Universal Design for Learning [UDL] principles). Participants emphasized the lack of systematic early screening, noting that the late classification of learning difficulties leads to persistent academic gaps that could have been addressed earlier through planned screening windows and routine progress-monitoring cycles.

4.13. Lack of a Unified Framework

Stakeholders repeatedly underscored that one of the most pressing challenges facing classification and progress monitoring in Qatar is the absence of a clear, unified national framework. While the system formally relies on centralized classification into three levels, participants explained that the criteria guiding schools remain vague and inconsistently communicated and operationalized. Teachers, coordinators, and administrators described this lack of coherence as a source of confusion, with schools applying different standards depending on local interpretation, available resources, staff training, or the discretion of individual staff members. One coordinator pointed to the ambiguity directly, explaining: “The common classification is the three levels … but the criteria are not sufficiently available.” Teachers echoed this concern, emphasizing that the lack of explicit guidelines leads to varied practices across schools. As one teacher observed: “There are no clear instructions from the Ministry … every school interprets the system in its own way.”

This fragmentation complicates educators’ work and undermines parents’ trust in the system. Participants explained that while the official criteria address the type of disability, the type of service, and the intensity of support required, these standards are not consistently applied across schools. As one participant observed: “The criteria used … depend on the type of disability, the type of service, and the intensity of the service … but every school interprets them differently.” Such variability creates confusion for families, who often question why their child is classified differently depending on the school, and leaves teachers struggling to implement support within a framework that lacks clear, consistent guidance. Stakeholders suggested that a unified framework should specify standard operating procedures (SOPs), including eligibility decision trees, re-evaluation intervals, accommodation menus by need, and data-sharing protocols, supported by a centralized case-management process and a unified EMIS platform for documentation.

Several educators also argued that the lack of a unified framework weakens monitoring, since there is no standardized approach for documenting and reviewing student progress across institutions. A coordinator reflected on this gap: “Reports differ from one school to another … we don’t have a unified platform or clear monitoring criteria.” Without a unified approach, as participants expressed, the system remains fragmented, leaving students vulnerable to misclassification and uneven support depending on their school context. Participants also called for routine progress-review cycles (e.g., termly or biannual) and an appeals/second opinion pathway to ensure classifications remain accurate over time.

4.14. Restricted Accommodations

Stakeholders also highlighted that the accommodations available to students with learning difficulties remain limited in both scope and flexibility. While the classification system formally acknowledges the need for differentiated support, teachers and coordinators explained that, in practice, the permitted adjustments are narrow, often limited to measures, such as granting extra time during exams (i.e., access to accommodations rather than instructional or assessment modifications when warranted).

Participants described how such limited accommodations fail to meet students’ diverse needs, reducing classification outcomes to symbolic labels rather than to actionable educational plans. One teacher noted the gap between students’ needs and the accommodations allowed, pointing out that schools often provide only the most minimal adjustments: “The accommodations we give are usually just extra time … there are no real modifications to content or assessment methods.” Another participant expressed frustration that some supportive measures, such as reading exam questions aloud to students with reading difficulties, are not permitted under current policy: “We are not allowed to read the questions to the student … even though this could help him understand what is required.”

Educators stressed that this narrow approach undermines the purpose of inclusive education, as students who require alternative methods to demonstrate their knowledge are assessed with the same rigid tools as their peers. A coordinator emphasized this point, explaining: “The student has an IEP, but when the exam comes, he sits for the same test … the result is that he appears weaker than his peers.” Teachers further explained that the narrow scope of accommodations has practical implications in their daily work. For instance, while extra time may support some students, it does not address difficulties related to comprehension, memory, or expressive language. As one teacher put it: “Extra time doesn’t solve the problem if the student doesn’t understand the question in the first place or cannot express himself.” Others added that even when teachers attempt to adapt lessons or assessments informally, such practices are not officially recognized, which reduces their consistency and effectiveness across classrooms. Stakeholders proposed an expanded, transparent accommodations menu (e.g., alternative item formats, scaffolded language supports, assistive technology, scribing/read-aloud in appropriate contexts, project-based assessments) linked to IEP goals, with expectations for documentation and fidelity checks.

4.15. Need for Early Screening

Stakeholders emphasized that one persistent weakness of the classification and monitoring system in Qatari schools is the lack of systematic early screening. Teachers, coordinators, and administrators repeatedly stressed that students with learning difficulties are often identified late, sometimes only after academic struggles become severe and entrenched. This delay, participants explained, not only widens learning gaps but also makes intervention less effective, as students lose confidence and develop behavioral or motivational issues in response to repeated failure. Teachers described how the absence of early screening often leaves them as the first to notice difficulties, but without formal processes to act quickly. A teacher explained: “We notice the problem in first or second grade … but the official procedures only start years later.” Another participant underscored that waiting until problems escalate places additional stress on both teachers and families: “Parents come to us late, after the student has failed more than once … whereas with early detection we could have helped from the beginning.”

Coordinators also emphasized that late classification undermines the credibility of the classification system, since many students are labeled only after years of underachievement rather than through proactive assessments. One coordinator explained: “Classification comes as a reaction after the student is already affected … not as part of a preventive plan from the start.” Stakeholders suggested that early screening is about earlier diagnosis and preventing misclassification. Without baseline data on students’ developmental and cognitive profiles, schools may confuse temporary delays or attention issues with formal learning disabilities. A teacher pointed out this challenge: “A student might have a temporary weakness in reading … but without early screening, he is immediately considered to have learning difficulties.” Educators further argued that early screening could help reduce stigma by framing classification as part of a natural developmental process rather than as a label applied only when students have already fallen behind. As one school leader explained: “If there was early assessment for all students … it would be natural and would not create sensitivity for parents … and it would not tie classification to failure.” Moreover, stakeholders’ accounts consistently pointed to early screening as an essential but missing link in creating a proactive, equitable, and educationally meaningful classification and monitoring system. Participants proposed a universal screening model (e.g., KG–Grade 2) using validated tools in literacy, numeracy, language, attention/behavior, followed by a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS/RTI), scheduled progress checks (e.g., every 6–8 weeks), and clear parent-communication/consent templates to enable timely referrals and reduce false positives/negatives.

4.16. Fragmented Monitoring Systems

A further theme that emerged from the interviews was the fragmentation of progress monitoring practices across schools. Stakeholders explained that while classification places students into formal categories, the subsequent monitoring of their development is often inconsistent, disconnected, and heavily reliant on paperwork rather than digitized, interoperable systems. Teachers and coordinators described how multiple, overlapping tools, such as student files, IEP reports, and informal teacher notes, are used in parallel, but are rarely aligned through standard templates or shared protocols. Still, they rarely coordinated in a way that produced a coherent, cumulative picture of student progress. Participants also highlighted the lack of a unified data platform, leading to repeated assessments and duplication of effort. This fragmentation results in missed opportunities to track long-term growth and to initiate timely reviews of classifications. In concert, these accounts reflect a fragmented rather than systematic monitoring system, leaving schools without the robust evidence base needed to adapt interventions or to review the accuracy of classifications over time. Stakeholders pointed to the need for a privacy-protected, role-based EMIS with unique student identifiers, standardized forms, and automated re-evaluation reminders to support longitudinal analysis and instructional decision-making.

4.17. Multiple Disconnected Tools

Stakeholders described how progress monitoring in Qatari schools relies on multiple tools that often operate in isolation, creating a fragmented, inefficient system. Teachers, coordinators, and administrators pointed out that documentation typically includes student files, IEPs, progress reports, and informal teacher notes. However, these tools are not integrated, and information is rarely shared across staff members or institutions using common data standards or version control. As a result, participants explained, the process becomes more about fulfilling administrative requirements (compliance) than about generating meaningful insights into students’ development. One coordinator explained this dynamic clearly: “Each student has a file, an IEP, and a follow-up report … but these tools are not connected … each person writes in their own way.”

Teachers echoed this concern, emphasizing that the use of disconnected monitoring tools often results in duplication. For example, the same information may be recorded across multiple documents without improving the understanding of student progress. One teacher described this frustration: “Sometimes we write the same notes on more than one form … and in the end there is no real follow-up in practice.” Administrators noted that the absence of a standardized monitoring framework leads to wide variation in report quality, depending on individual teachers’ styles and the time available to them. A principal reflected on this inconsistency: “Reports differ from one teacher to another … there is no standardized format that makes follow-up clear.” Participants suggested consolidating documentation into a single student record with standardized fields, drop-down taxonomies, and time-stamped entries so that progress evidence accumulates and is auditable across years and schools.

Several participants also noted that the lack of alignment among tools leads to confusion when evaluating students’ progress over time. Without a single, coherent record, it becomes difficult to track whether interventions are working or whether a student’s classification remains accurate. One teacher summarized this problem: “The problem is that the tools exist but are not connected … so every year we start from scratch instead of building on what came before.” These perspectives suggest that using multiple disconnected tools contributes to inefficiency and weakens schools’ ability to make data-driven decisions about classification and progress monitoring. A unified template and timeline would reduce duplication and shift monitoring from paperwork to improvement.

4.18. Limited Data Integration

Stakeholders emphasized that, beyond the use of multiple disconnected tools, the absence of a unified platform for storing and sharing student information is one of the most critical weaknesses of the current monitoring system. Teachers, coordinators, and administrators explained that data on student progress is scattered across files, forms, and reports, making it challenging to construct a coherent picture of a student’s development. As a result, monitoring often becomes fragmented, with essential details lost in transition or repeated unnecessarily. One coordinator described the inefficiency of this system: “The information is scattered … there is no single place that brings everything together.” Teachers also noted that the lack of integration creates redundancy, requiring them to repeatedly assess and document the same student without building on prior evaluations. One teacher noted: “We repeat the same assessments every term … because the old data isn’t saved or easily accessible.” Stakeholders noted that, without a “single source of truth,” longitudinal trends cannot be visualized, early warning thresholds are not flagged, and targeted supports are delayed.

This fragmentation not only wastes valuable time but also undermines the reliability of monitoring data. A principal explained that without integrated records, it is difficult to verify whether interventions are effective or whether a student’s classification needs adjustment: “The information is not connected … so it’s hard to know if the plan worked or not.” Participants recommended establishing secure data-sharing agreements and role-based permissions, so that external reports, school assessments, and IEP updates are automatically ingested into a unified record via standardized formats/APIs.

Some participants further observed that limited data integration weakens communication between schools and external diagnostic centers. Because schools lack a unified reporting system, external reports often do not align with school-based data, resulting in further inconsistencies in how students are classified and monitored. One coordinator described this disconnect: “The report comes from the center in one format, and the school reports are in another … there is no link between them … and it is the student who is affected.” The stakeholders also illustrated how the lack of integrated data systems constrains schools’ ability to track student progress longitudinally, adapt interventions, and ensure accurate classifications over time. Participants emphasized that interoperable platforms and shared taxonomies (e.g., common codes for needs, accommodations, and interventions) are essential for maintaining cumulative records, facilitating timely re-evaluation, and ensuring consistent communication with families and external providers.

4.19. Innovative Inclusive Practices

Despite the systemic challenges highlighted in earlier themes, many stakeholders also described innovative and adaptive practices that schools and teachers have developed to bridge gaps in classification and monitoring and to translate progress data into day-to-day instructional adjustments. These practices often emerged from educators’ professional creativity and their commitment to inclusion, even when formal resources or policies were limited or inconsistently applied. Teachers reported experimenting with various classroom strategies, including peer modeling, learning stations, and project-based learning, to support students with diverse needs and to provide multiple means of engagement and expression (aligned with UDL principles). Coordinators and principals discussed the growing use of technology and artificial intelligence (AI) to facilitate assessments and tailor instruction, particularly through digital platforms that provide immediate feedback and cumulative, time-stamped records. In addition, several participants described using behavioral interventions, including individualized behavior plans, shadow teachers, and targeted strategies to manage classroom dynamics, with documented response-to-intervention cycles and regular review points.

4.20. Classroom Strategies

Stakeholders frequently highlighted how teachers use creative classroom strategies to support students with learning difficulties, particularly when formal classification and monitoring systems fall short or are slow to update. These approaches, although not always formally documented, were described as essential for enabling participation and fostering inclusion within everyday lessons, as well as for generating formative evidence (e.g., exit tickets, quick checks) that can inform subsequent support and instruction. Teachers explained that such strategies often emerge from trial and error, collaboration among colleagues, and a strong sense of responsibility toward ensuring that all students are engaged in the learning process through small-group instruction, scaffolded tasks, and accessible materials. One teacher described using peer modeling to help students with learning difficulties acquire skills more naturally in a supportive environment: “We let the advanced students sit with peers who have difficulties … the student learns faster when he sees his friend applying it.” Others spoke about creating learning stations or small groups to differentiate instruction, noting that this structure allows them to provide targeted support without isolating students and to record short notes on student responses during each station. A coordinator explained: “We divided the class into groups … each group had a different activity … this allowed students with difficulties to participate more effectively.”

Teachers also experimented with project-based learning to provide opportunities for students with difficulties to demonstrate strengths outside traditional tests and to capture evidence via rubrics that reflect growth over time. One participant recalled a particularly successful example: “In one of the practical projects … the students who are usually not doing well in exams excelled noticeably.” Educators further stressed the importance of flexible teaching strategies, such as using visuals, breaking down instructions, and providing repeated practice with clear success criteria. A teacher explained how these adjustments help make the curriculum more accessible: “I change the way of explaining by using pictures and simple examples … the student understands better than with theoretical talk alone.”

Stakeholders described these strategies as filling the gap left by limited accommodations and fragmented monitoring, noting that teachers often rely on their professional judgment to adapt lessons in real-time while logging brief observations that can be compiled into IEP reviews. While not standardized, these practices reflect a strong commitment to inclusion and demonstrate how educators are innovating within their classrooms to meet the diverse learning needs of their students and to generate actionable, classroom-level data.

4.21. Technology and AI Use

Stakeholders also identified the growing role of technology and AI in supporting classification and monitoring practices, particularly as schools seek ways to overcome resource shortages and large class sizes. Teachers and coordinators described how digital tools can provide immediate feedback, enable differentiated instruction, and help track student progress more systematically than paper-based reports through dashboards, trend lines, and alerts. These innovations, while not yet standardized across schools, were viewed as promising practices that enhance the accuracy and efficiency of support for students with learning difficulties when integrated with existing school records. One coordinator explained how digital platforms would support classroom instruction: “If we used more platforms to monitor the student … they would provide immediate reports on each one’s level.”

Teachers noted that AI-enabled applications could help identify patterns in student performance that may not be apparent in traditional assessments (e.g., error types or timing patterns). A teacher described how such tools aid in tailoring instruction: “There are programs that measure the student’s interaction with activities … and show if he struggles with a specific part … this will help us adjust the plan.” Others highlighted how technology reduces the burden of manual paperwork and supports continuous monitoring. One participant reflected: “Instead of writing everything manually … we upload the data to the electronic system … and this makes review and follow-up easier.”

Participants also highlighted the potential of AI to facilitate more equitable monitoring by reducing reliance on subjective teacher judgments when used in conjunction with teacher professional judgment and validated measures. A coordinator commented on this benefit: “AI allows us to monitor the student objectively… it doesn’t depend solely on the teacher’s opinion.” At the same time, some educators cautioned that while technology provides valuable tools, it requires training and resources to be used effectively, as well as policies for data privacy, consent, and responsible use. As one teacher noted: “The platforms require that all teachers know how to use them … we need more training.” These perspectives demonstrate that, although the integration of technology and AI remains uneven, stakeholders view it as a promising avenue for enhancing classification and monitoring, making them more systematic, data-driven, and responsive to student needs, provided there is training, technical support, and interoperability with school systems.

4.22. Behavioral Interventions

In addition to academic strategies and technology, stakeholders emphasized the importance of behavioral interventions as part of inclusive practices in Qatari schools. Teachers and coordinators noted that many students with disabilities also present with behavioral or social challenges that influence their academic performance. Without targeted behavioral support, they explained, progress monitoring and academic interventions often fail to reach their full potential because instructional time is lost to management challenges. As a result, educators have developed a range of classroom-based strategies, individualized behavior plans, and the use of shadow teachers to address behavioral needs alongside academic goals using function-based assessments and clear reinforcement schedules. One teacher described how individualized behavior plans are designed to guide both students and staff in responding to specific behavioral challenges: “We write a behavior plan for the student … it has clear steps for the teacher and the student … this makes management easier.”

Coordinators also pointed out that assigning shadow teachers is one of the most effective approaches for students with more significant behavioral difficulties. A coordinator explained: “Some students need to have a shadow teacher with them … to help them stay focused and regulate their behavior throughout the day.” Participants noted that role clarity, basic training, and daily logs enhance the effectiveness of shadow support, enabling progress to be reviewed. Teachers further reported that simple classroom adjustments, such as establishing clear routines, using positive reinforcement, and providing frequent breaks, play a key role in managing classroom dynamics and in capturing observable data points (e.g., frequency counts, duration) over time. One participant reflected on this: “I use positive reinforcement with the students … whenever he follows the expected behavior, I give them a small reward … and this motivates them.” Another teacher emphasized the role of structured routines in reducing behavioral incidents: “A student with ASD needs a clear daily schedule … if there is no routine, he becomes anxious and displays unwanted behaviors.”

Participants emphasized that addressing behavioral challenges is crucial to creating an environment where academic support is practical. They explained that when behavior is managed successfully, students are more engaged, teachers are less burdened, and progress monitoring reflects a more accurate picture of student development because instructional plans can be implemented with fidelity and reviewed against clear targets.

5. Discussion

The results are interpreted through a framework that combines the principles of sustainable inclusive governance [

6,

9] and the theory of education system improvement [

22]. The framework illustrates that classification and monitoring challenges are not isolated phenomena but stem from complex interactions across systemic levels (macro, meso, and micro). Three key dynamics exemplify these systemic interactions: first, through the interplay between centralization and flexibility (macro vs. micro). The centralized classification policy (macro), which delegates diagnostic responsibility to an external center, has significantly limited teachers’ professional flexibility (micro). Instead of relying on their daily observations and contextual assessments, teachers are now often restricted to external reports, which are sometimes described as “superficial” or “repetitive.” Despite its intent to standardise practices, this centralised approach has inadvertently undermined the teacher’s role as a key partner in the diagnostic process, creating a gap between the formal diagnosis and the daily educational reality the teacher monitors. Second, from the perspective of the interaction between policy and resources (macro vs. meso level), despite an ambitious inclusion policy (macro), the lack of resources at the school level (meso), represented by a scarcity of specialists and overcrowded classrooms, prevents its effective implementation. This contradiction creates a situation in which formal classifications alone are insufficient to ensure student support, as schools lack the capacity to deliver the necessary interventions. Consequently, the ambitious policy becomes a practical burden on schools rather than a support tool, widening the gap between political ambition and operational reality.

Third, from the perspective of the school-family interaction (meso vs. macro level), cultural values and societal stigma (macro) clearly influence families’ attitudes and acceptance of their children’s classification. However, the school’s (meso) lack of effective, standardized communication protocols exacerbates this resistance. The lack of a clear and consistent framework for engaging parents and explaining the process leaves families with two choices: passive acceptance or complete rejection. Therefore, the success of any classification and integration policy requires simultaneous treatment at both the community (awareness raising) and institutional (building schools’ communication capacity) levels.

The dominance of the medical model in classification processes exemplifies this systemic interaction. Stakeholders have consistently noted that over-reliance on external medical reports leads to inconsistencies and marginalizes educational perspectives… The marginalization of educators’ opinions appears common, often distorting the classification of and response to students’ actual learning needs. These practices, which rely on a medical model-based classification system, render classification judgments susceptible to subjective interpretation and contextual influences [

8]. Consequently, this situation leads to evident contradictions in attempts to make informed decisions about students. Moreover, there is a critical need to make data-driven decisions using multiple approaches, while acknowledging the persistent reliance on external medical reports. This contradiction diminishes educators’ role and clearly contradicts global practices that emphasize the interconnectedness between standardized diagnoses and educational practice [

47]. In fact, as a result of these deviant practices, some phenomena have emerged, such as “paper diagnosis”, wherein classification decisions were dictated more by documents than by a nuanced comprehension of students’ needs, leading to misclassification and inappropriate support [

7,

23]. These inconsistencies reflect the variability stated in the findings, where disparities between schools resulted in unequal opportunities for pupils with disabilities to receive timely and adequate support services.

Thus, these phenomena could lead to a poor classification process and individualized practices by teachers, ultimately resulting in inadequate integrated support [

47]. Although the Qatari educational system adopts a centralized, standardized approach, it inadvertently exacerbates discrepancies through discretionary practices in schools. This draws attention to important questions about the system’s consistency with modern global hybrid systems (medical and educational). It also raises concerns about whether these practices lead to inequality, as in cases of autism spectrum disorder, where strengths are disregarded, or in cases of learning difficulties, where the diagnosis is arduous and complex. This conclusion is consistent with the national context outlined in the

Section 4, where schools reported difficulties in identifying and categorizing learners, resulting in unequal access to services and accommodations.

Furthermore, the negative interaction between politics and resources (macro–meso) creates an evident paradox: the government allocates a larger budget than other countries in the MENA region, yet shortages of resources and personnel persist. This points to a systemic capacity issue, where resource and staff shortages, coupled with fragmented monitoring systems, directly reduce the accuracy of both classification and monitoring. This challenge also appears in other rapidly reforming systems [

9]. This shortage is more likely to convert inclusive education into mere physical presence rather than adequate support. The use of multiple disconnected tools and the absence of an integrated data platform prevent the longitudinal tracking of students’ progress, hindering the system’s ability to be adaptive and evidence-informed [

16,

29]. This situation is likely to have negative consequences for teachers who are already burdened by crowded classrooms and heavy administrative workloads, creating a clear gap in the implementation of inclusive education [

48]. This predicament is prevalent in specific reform systems in which policy exceeds capabilities [

17]. As stated in the

Section 4, participants consistently identified low expertise and insufficient professional development opportunities as key impediments to maintaining inclusive practices. Addressing these capability shortfalls should be prioritized in future implementation plans.

The findings also indicated that the classification of disability is not only a technical issue but also a culturally and socially negotiated process influenced by institutional discretion and resource restrictions. This issue is deeply rooted in the local culture, wherein disability is viewed through a traditional social lens rather than a progressive one [

3,

11]. As disability is seen in Islamic societies as a curse, punishment, test, and/or stigma [

49], the fear of these consequences in the Qatari context leads to a broader stigma and a high level of anxiety of social judgment, which is more likely to result in under-classification, as in other regional and cultural contexts where disability is stigmatized. Consequently, our findings underscore the urgent need to reform the current system to be more responsive to cultural contexts, viewing parents as partners rather than obstacles [

4]. The participants’ emphasis on strengthening family–school partnerships suggests that awareness campaigns and culturally sensitive communication strategies could help overcome stigma and enhance early classification processes. This perspective is supported by the literature, which indicates that “top-down” decisions lacking parental involvement are futile [

3].

Although Qatar has made notable progress in addressing issues for people with disabilities, the gap between policy and practice remains evident. Several issues exemplify this gap, including the lack of a unified framework, limited accommodations, and insufficient early detection. Although Qatar has made significant progress in developing policies to effectively address the learning needs of students with disabilities [

14,

17], this progress is not yet reflected in standard operating procedures, expanded accommodations, or thorough early screening linked to tiered support programs. Thus, the policy vision cannot be consistently implemented in classrooms, perpetuating a gap between policy and practice that remains a continuous challenge to achieving the desired and sustainable educational reform [

22]. This finding emphasizes the importance of translating policy intentions into standardized operational procedures, ensuring consistency across schools and alignment with the principles of UDL and RTI frameworks.

Crucially, the findings demonstrate that innovative and inclusive practices showcase teachers’ agency and resilience. These innovative practices demonstrate that teachers are not passive recipients or implementers within a flawed educational system, but active agents whose creativity reflects an authentic pedagogy of inclusive education, bridging systemic gaps even in the absence of formal support. Instead, they are active agents who develop adaptive classroom strategies, experiment with technology/AI, and implement behavioral interventions. It reflects the pedagogy of inclusive education [

26], where teachers can use their creativity to bridge systemic gaps, even in the absence of formal support.

Comparative evidence across Gulf and Arab systems suggests that cultural orientations toward disability, particularly concerns about social standing and stigma, shape families’ willingness to seek or accept formal classification, even where supportive national policies exist. Studies in the region document how labeling effects and community perceptions can dampen referrals, delay identification, or trigger resistance, thereby weakening the link between policy ambition and day-to-day practice in schools [

50,

51]. In Qatar and neighboring systems, these dynamics intersect with capacity constraints and uneven teacher preparation, resulting in variability in how inclusive education is implemented, despite formal commitments to inclusion and system improvement [

15,

34]. In this respect, the Qatari case exemplifies how cultural norms and institutional conditions mediate the implementation of inclusive governance, reinforcing the need for culturally responsive communication and family–school partnership strategies to support timely and equitable classification.

By contrast, in many Western contexts, inclusion has been framed more consistently through rights-based discourses aligned with the CRPD, which has supported earlier identification, stronger parental participation, and the normalization of school–family collaboration as part of routine inclusive practice [

12,

32]. Research on inclusive pedagogy and whole-school inclusion further emphasizes proactive, universal design–oriented responses that reduce reliance on deficit labels and help align classroom practices with system-level equity goals [

1,

2,

23,

24,

26]. These contrasts underscore that policy frameworks alone are insufficient; the cultural and pedagogical orientations that surround disability meaningfully condition how classification and monitoring mechanisms take root in schools. For rapid system reform, this implies that governance and data architectures should be paired with deliberate strategies to build cultural readiness and pedagogical capacity, ensuring that international commitments translate into locally legitimate, sustainable practices [

6,

9].