Carbon Emission Efficiency in China (2010–2025): Dual-Scale Analysis, Drivers, and Forecasts Across the Eight Comprehensive Economic Zones

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Super-Efficiency SBM Model with Undesirable Outputs

- Model type: Super-SBM with undesirable outputs

- Returns-to-scale assumption: Variable returns to scale (VRS)

- Solver: MATLAB R2022b, linprog (interior-point algorithm)

- Convergence tolerance: 1 × 10−6

- Epsilon adjustment: ε = 1 × 10−6 added to undesirable outputs

3.2. Malmquist-Luenberger Index

3.3. ARIMA-LSTM Forecast Model

- (1)

- ARIMA models the linear structure of the CEE series to obtain fitted values ;

- (2)

- residuals are modeled by LSTM to capture nonlinear effects;

- (3)

- the final forecast is derived by residual correction: .

3.4. Tobit Model

4. Variable Selection and Data Source

4.1. Input and Output Variables

4.1.1. Input Variables

4.1.2. Output Variables

4.2. Influencing Factors of CEE

4.3. Data Source

5. Results Analysis

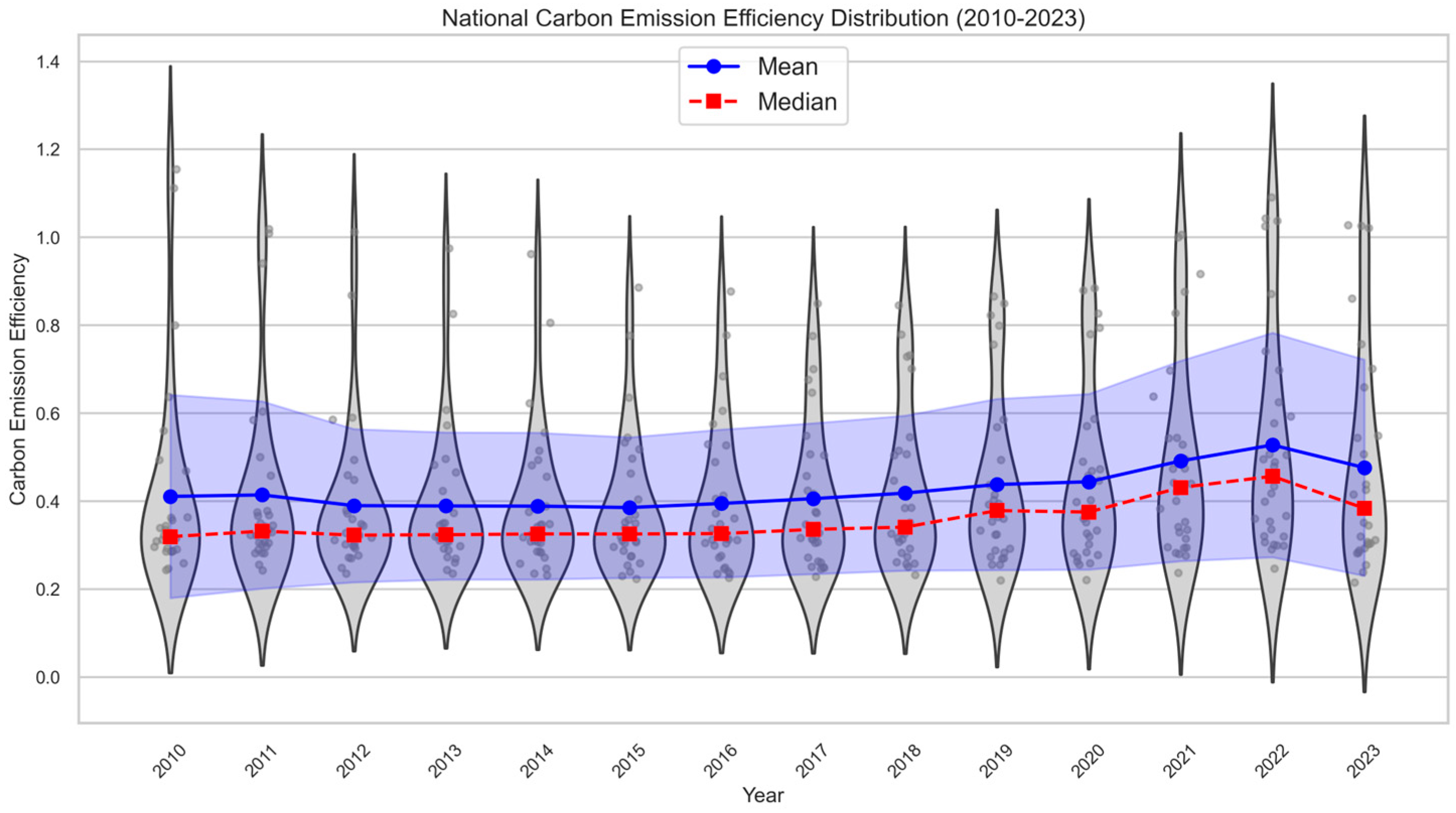

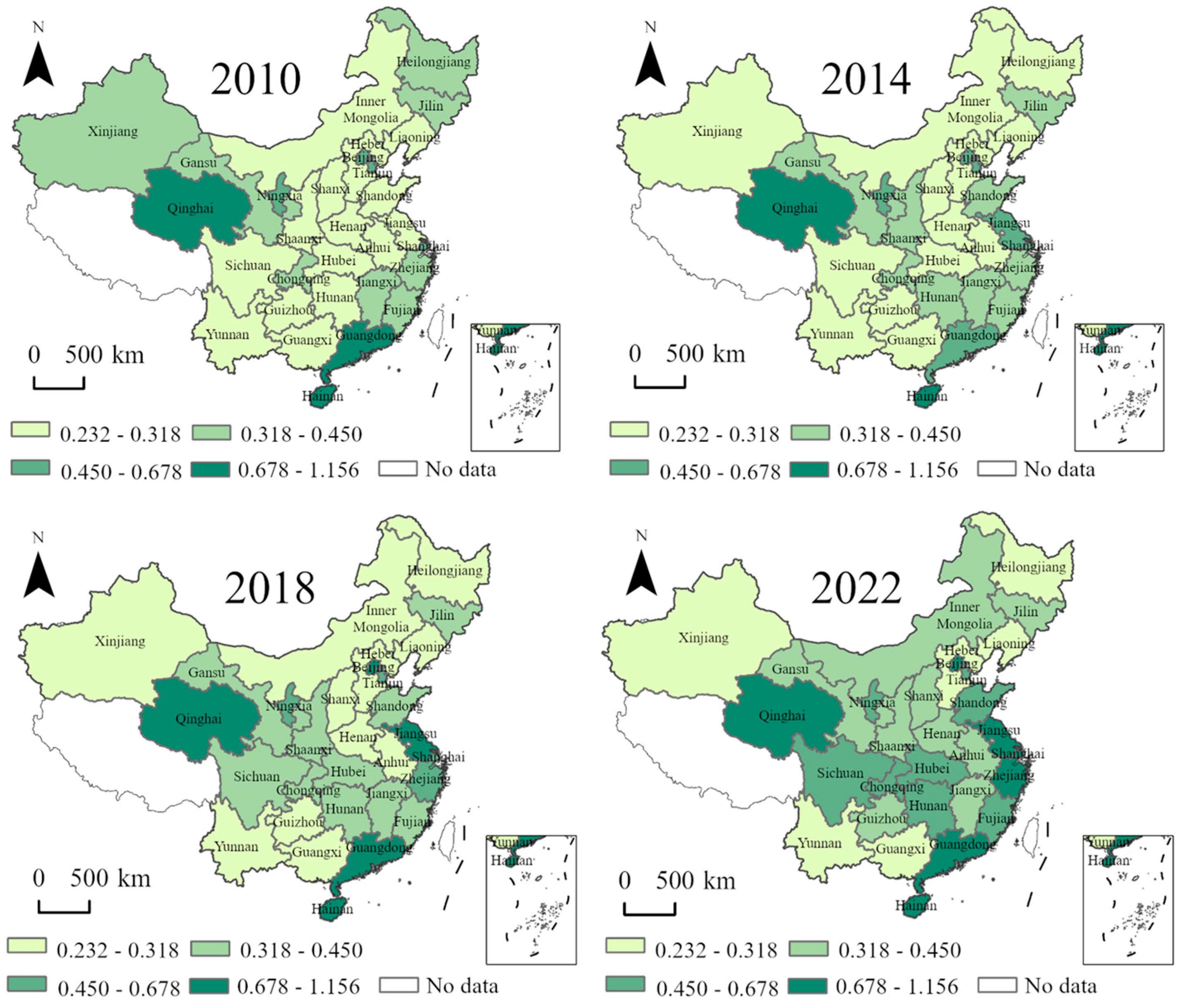

5.1. Static Analysis of CEE in China

5.1.1. Measurement and Analysis of Provincial CEE

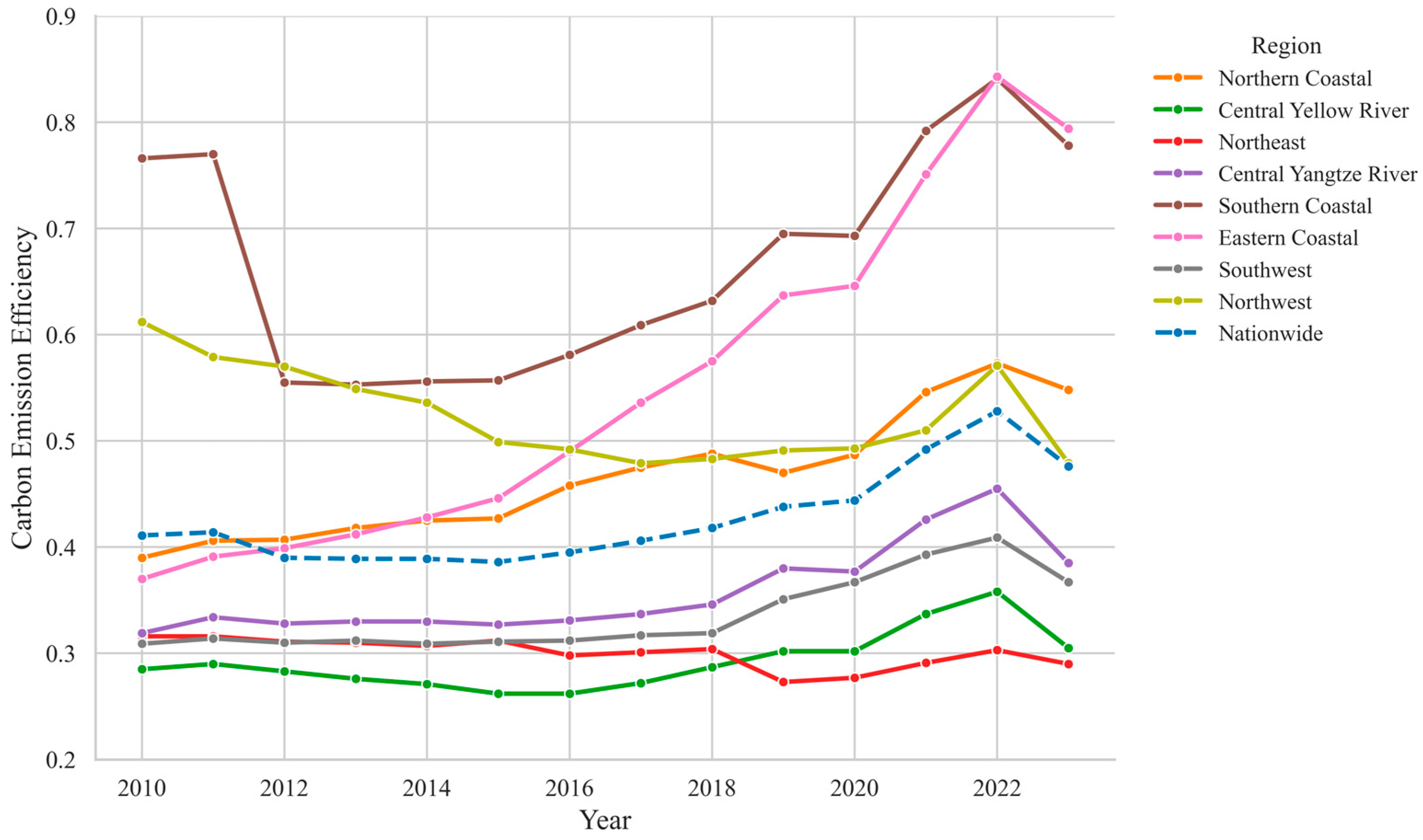

5.1.2. Measurement and Analysis of CEE in Eight Comprehensive Economic Zones

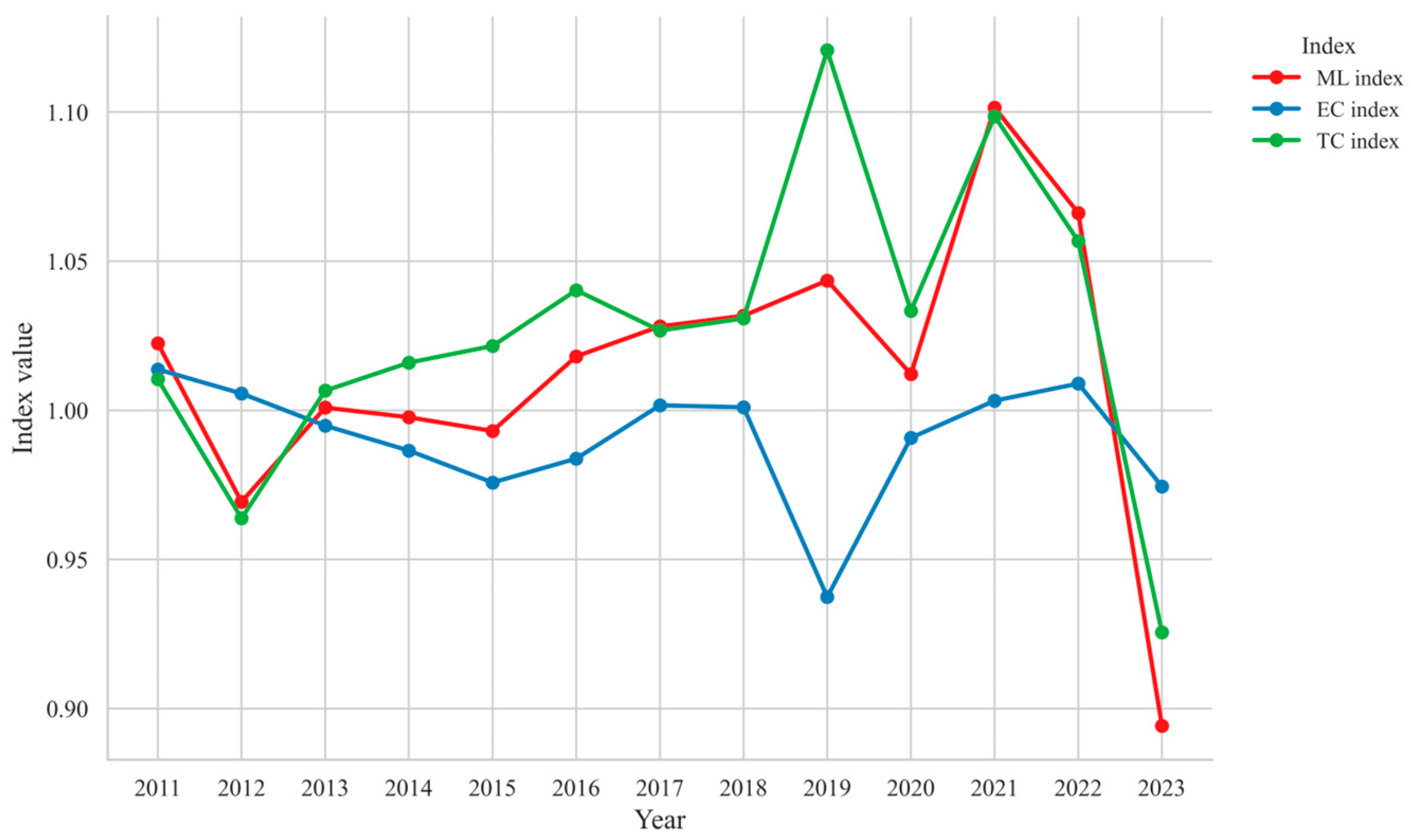

5.2. Dynamic Analysis of CEE Changes

5.2.1. Dynamic Analysis of Provincial CEE Changes

- TC-led type, Coastal—Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Guangdong: efficiency gains are primarily propelled by TC, with EC providing supportive co-movements.

- Structural-upgrade type, Central—Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan: during 2018–2019, TC dominated due to industrial upgrading and process retrofits; in 2022–2023, an energy-use rebound coincided with simultaneous declines in both TC and EC.

- Allocation-constrained type—Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang: weak governance and factor-allocation efficiency limit sustained improvement; episodic TC upticks have not translated into durable gains.

- Resource-dependent type—Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, Xinjiang: many operate upstream in resource-intensive and process industries; EC is persistently weak and TC improvements have not yielded lasting efficiency upgrades.

- TC-driven but unstable type, Southwest —Sichuan, Chongqing, Guizhou, Yunnan: TC raised efficiency in 2018–2019, yet the momentum proved hard to maintain; widespread shortfalls in managerial and allocation efficiency (low EC) meant that 2022–2023 combined external shocks with internal bottlenecks, producing volatile gains.

- Structure-sensitive type, Small-scale—Hainan, Qinghai: small economic size and narrow industrial bases heighten the risk of TC–EC mismatches, leading to fluctuation in the ML index.

5.2.2. Dynamic Analysis of CEE Changes in the Eight Comprehensive Economic Zones

6. Drivers of China’s CEE and Forecasts

6.1. Historical-Stage Analysis of Influencing Factors (2010–2023)

6.2. ARIMA-LSTM Based Forecasts of CEE in China

- Input layer—sliding window of five observations (the most recent five residuals) to predict the next period;

- LSTM layer—one recurrent layer with 16–32 hidden units, capturing short-term fluctuations and long-range dependencies;

- Fully connected (FC) layer—projects the hidden representation to a single scalar output;

- Output layer—one-step-ahead residual forecast.

6.3. Future Analysis of Influencing Factors (2024–2025)

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

7.1. Conclusions

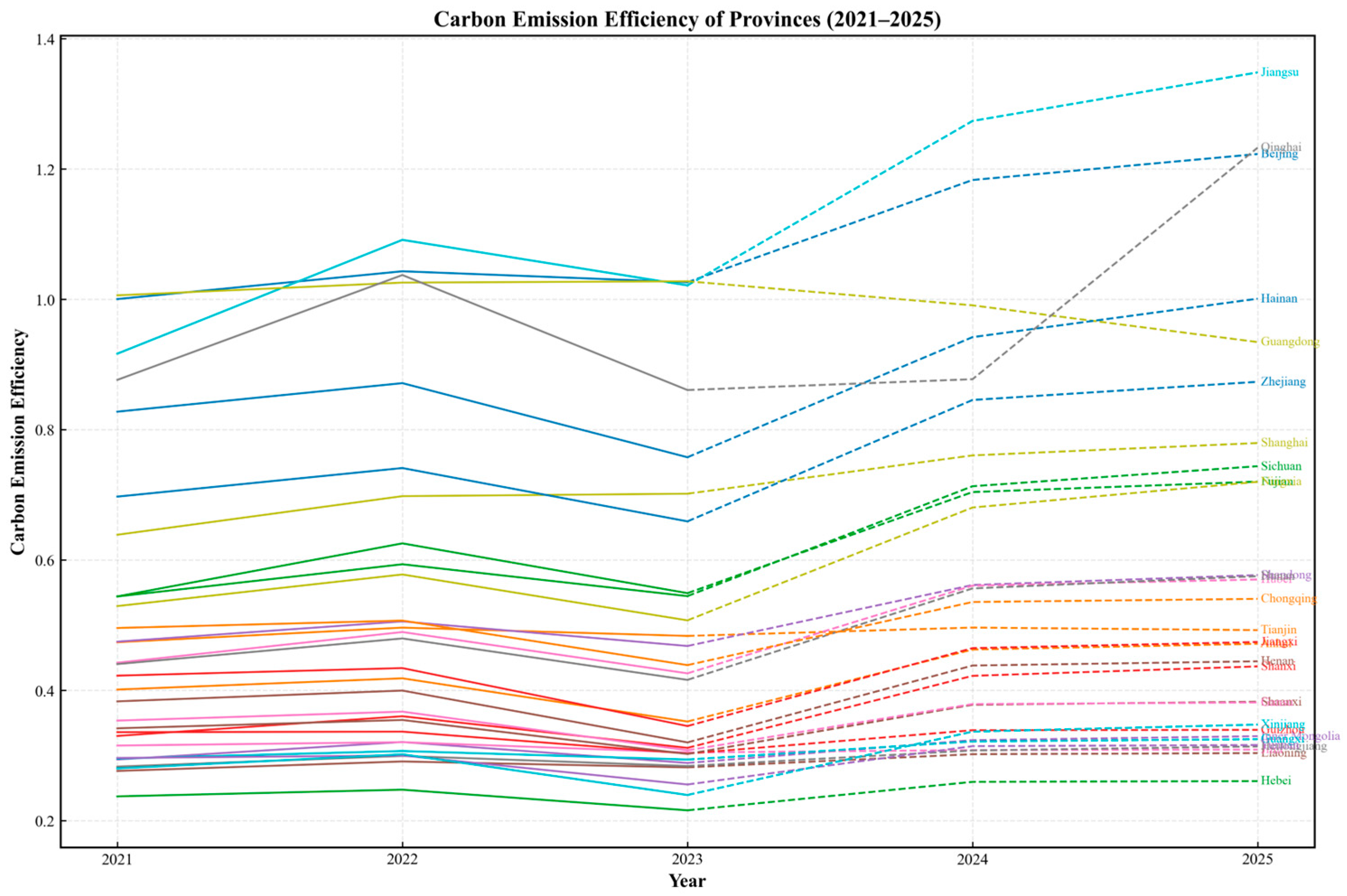

- Nationally, CEE remains low on average but is rising steadily. During the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025), forecasts indicate continued and stable gains in CEE, albeit with limited magnitude. Notable regional disparities persist across the eight comprehensive economic regions. The Eastern and Southern Coastal zones maintain the highest and still-rising efficiency, while the Northern Coastal and Central Yangtze River regions occupy intermediate positions with sustained energy-use pressures. The Southwest and Northwest show relatively lower efficiency but possess favorable green-resource endowments and significant transition potential. The Northeast and Central Yellow River regions remain at the lower end, exhibiting gradual but limited improvement.

- Regionally, efficiency performance differs mainly due to variations in industrial structure, resource endowments, and energy transition progress rather than distinct technological frontiers. The Eastern and Southern Coastal regions sustain leadership through technological upgrading and industrial optimization, though recent gains have moderated. The Northern Coastal region shows an early-high/late-low trajectory, largely reflecting slowing efficiency improvement. In the Central Yangtze River, efficiency rose during 2018–2019 but declined in 2022–2023 amid economic restructuring pressures. The Southwest improved rapidly in 2018–2019, driven by renewable expansion, then stabilized due to geographic and infrastructure constraints. The Northwest remains constrained by energy intensity and resource dependence, while the Northeast continues to lag due to rigid industrial structures and managerial inefficiency. The Central Yellow River region remains coal-dependent, with slow progress toward transition.

- At the national level, technological development exerts the most consistent and significant positive effect on CEE, confirming technological progress as a sustained driver of improvement rather than a region-specific frontier shift. Economic development and industrial restructuring also show persistent positive impacts, which strengthen in the forecast period, indicating closer coupling between green transformation and efficiency gains. Population density and energy consumption remain significant negative drivers, though their effects gradually moderate with the advancement of green-city and energy-transition policies. Regional heterogeneity in coefficients reflects structural, institutional, and developmental differences, highlighting the need for place-based and differentiated strategies to enhance efficiency and advance coordinated decarbonization.

7.2. Policy Implications

- (1)

- Lead with green innovation. Technological innovation is verified as the most influential positive driver of CEE at both national and regional levels. Eastern and southern coastal regions, already innovation-intensive, should further integrate research and application, promote the commercialization of clean technologies in the energy, transport, and construction sectors, and strengthen intellectual property protection to sustain innovation-driven growth. Lagging regions such as the Northeast and Central Yellow River should expand fiscal and credit incentives for low-carbon technology adoption. Targeted R&D subsidies, preferential tax treatment, and talent programs can help accelerate technological diffusion and narrow regional gaps.

- (2)

- Fuse growth with low-carbon transition. Economic development remains a statistically significant and stable contributor to efficiency, suggesting that growth and decarbonization can advance in parallel when driven by green investment and productivity improvement. Policymakers should maintain steady growth while continuously upgrading the industrial structure. Encouraging the expansion of modern services, high-value manufacturing, and circular-economy industries can replace energy- and emission-intensive sectors. Compact, transit-oriented, and green urban development will further mitigate efficiency losses in high-density areas. Integrating industrial restructuring with sustainable urbanization will accelerate the shift from resource-driven to innovation-driven growth.

- (3)

- Optimize industrial structure. The Tobit results identify industrial upgrading as the second most important positive determinant of CEE. Regions dominated by heavy industry should accelerate structural transformation and promote cleaner production. Implementing capacity replacement and emission control mechanisms for sectors such as steel, cement, and chemicals, alongside fiscal rebates or low-interest loans for firms meeting energy-intensity and emission targets, can generate tangible efficiency gains. These measures will gradually shift local economies toward a cleaner, more efficient industrial system.

- (4)

- Accelerate energy-mix transition. Energy consumption exerts a significant negative effect on efficiency, underscoring the need to reduce fossil dependency. Expanding renewable energy capacity and improving grid integration—especially in the Southwest and Northwest—will strengthen CEE over time. Dynamic energy pricing, carbon budgets, and performance-linked fiscal incentives should reward conservation and penalize inefficiency. Integrating energy-saving indicators into local government evaluations will reinforce accountability and ensure the long-term sustainability of efficiency gains.

- (5)

- Promote sustainable urbanization and population balance. Population density shows a robust negative relationship with CEE, implying that excessive urban concentration strains resources and increases emission intensity. Advancing a new type of urbanization supported by green infrastructure, smart mobility, and low-carbon buildings is thus essential. Balanced population and industrial distribution through metropolitan–county coordination can reduce congestion and energy waste. Improved urban planning standards integrating land use, transportation, and environmental management will help alleviate efficiency losses from over-urbanization.

- (6)

- Raise the quality of foreign direct investment. Although the national-level coefficient for FDI is statistically insignificant, regional results indicate positive effects in innovation-oriented regions (e.g., Southern and Northern Coasts) but negative spillovers in areas with weaker environmental governance. Hence, FDI should be reoriented toward high-tech and clean industries through tax incentives, green finance, and performance-based evaluation. Encouraging localized R&D and international cooperation on low-carbon technologies will enhance both technological upgrading and regional convergence in carbon efficiency.

- (7)

- Strengthen governance and coordination. Effective carbon governance requires coherent multi-level coordination. Integrating carbon-efficiency targets into fiscal performance, planning, and environmental assessments ensures policy alignment. The Tobit analysis underscores the growing importance of institutional and governance quality, reflected in the moderate but positive coefficient of government intervention. Strengthening the carbon-inclusive mechanism that links enterprises and individuals to emission-reduction incentives, promoting inter-regional carbon trading, and enhancing digital monitoring will further reinforce governance-driven efficiency improvement.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEE | Carbon Emission Efficiency |

| SBM | Slack-Based Measure |

| ML | Malmquist-Luenberger |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| LSTM | Long Short-term Memory |

| TD | Technological Development |

| ED | Economic Development |

| IS | Industrial Structure |

| EP | Environmental Protection |

| FDI | Foreign Direct Investment |

| EC | Energy Consumption |

| GI | Government Intervention |

| UR | Urbanization |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Lucey, B.M.; Urquhart, A.; Vigne, S.A. Why the global economy is more uncertain than ever, and what to do about it. Nature 2025, 643, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, L.C.; Zheng, W.; Zeng, L.E. Research on China’s Carbon Dioxide Emissions Efficiency from 2007 to 2016: Based on Two Stage Super Efficiency SBM Model and Tobit Model. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao 2021, 57, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y. Calculation of CEE in China and analysis of influencing factors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 111208–111220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.X.; Huang, R. CEE and influencing factors in Central and Eastern European countries based on Super-SBM model. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2024, 20, 581. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, Y.; Yokobori, K. Environment, Energy, and Economy: Strategies for Sustainability; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mielnik, O.; Goldemberg, J. The evolution of the “carbonization index” in developing countries. Energy Policy 1999, 27, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, B.W. Is the energy intensity a less useful indicator than the carbon factor in the study of climate change? Energy Policy 1999, 27, 943–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.M.; Timilsina, G.R. Factors affecting CO2 intensities of power sector in Asia: A Divisia decomposition analysis. Energy Econ. 1996, 18, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, L.-C.; Wu, G.; Tsai, H.-T.; Wei, Y.-M. Changes in carbon intensity in China: Empirical findings from 1980–2003. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, J.; Akimoto, K. Carbon intensity of the Japanese iron and steel industry: Analysis of factors from 2000 to 2019. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 345, 130920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, M.; Lin, R. Does lower regional density result in less CO2 emission per capita? Evidence from prefecture-level administrative regions in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 29887–29903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurlod, J.D.; Noailly, J. The impact of green innovation on energy intensity: An empirical analysis for 14 industrial sectors in OECD countries. Energy Econ. 2018, 71, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Huang, Q. The Impact mechanism of Global value chain embedment on CEE: The Belt and Road Initiative Evidence and enlightenment of manufacturing industry in countries along the Route. China’s Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Aigner, D.; Lovell, C.A.K.; Schmidt, P. Formulation and estimation of stochastic frontier production function models. J. Econom. 1977, 6, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrala, R.; Goel, R.K. Global CO2 efficiency: Country-wise estimates using a stochastic cost frontier. Energy Policy 2012, 45, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Zou, C.Y. Regional disparity, affecting factors and convergence analysis of carbon dioxide emission efficiency in China: On stochastic frontier model and panel unit root. Zhejiang Soc. Sci. 2011, 11, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan, R. A multi-factor efficiency perspective to the relationships among world GDP, energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2006, 73, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradan, D.; Vassiliev, A. Marginal costs of carbon dioxide abatement: Empirical evidence from cross-country analysis. Rev. Suisse D Econ. Stat. 2005, 141, 377. [Google Scholar]

- Zaim, O.; Taskin, F. Environmental efficiency in carbon dioxide emissions in the OECD: A non-parametric approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2000, 58, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Lu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, H. Analysis of regional differences and influencing factors on China’s carbon emission efficiency in 2005–2015. Energies 2019, 12, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 130, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K.; Sahoo, B.K. Degree of scale economies and congestion: A unified DEA approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 158, 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.; Petersen, N.C. A procedure for ranking efficient units in data envelopment analysis. Manag. Sci. 1993, 39, 1261–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G. Evaluation of regional carbon emissions performance based on SE-SBM model: Taking Shandong Province as an example. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 32, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Xi, S. Evaluation of carbon emission efficiency of resource-based cities and its policy enlightenment. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gao, S.; Huang, Y.; Shi, C. Spatio-temporal evolution and trend prediction of urban carbon emission performance in China based on super-efficiency SBM model. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 75, 1316–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xiao, Y. Spatio-temporal Evolution and Trend Prediction of Transport Carbon Emission Efficiency. Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 1879–1887. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Guo, X. Research on the Spatio-temporal Evolution Characteristics of Carbon Emission Efficiency in China’s Transportation Industry. East China Econ. Manag. 2023, 37, 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Li, S.; Meng, X.; Peng, Y.; Tang, W. Study on regional differences of carbon emission efficiency: Evidence from Chinese construction industry. Energies 2023, 16, 6882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Chen, M. Evaluation of Carbon Emission Efficiency in the Construction Industry Based on the Super-Efficient Slacks-Based Measure Model: A Case Study at the Provincial Level in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jia, G. Spatial spillover and threshold effects of high-quality tourism development on carbon emission efficiency of tourism under the “double carbon” target: Case study of Jiangxi, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Bai, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhang, C.; Jing, L.; Wang, L.; Zou, J. Comprehensive measurement and influencing factors of carbon emission efficiency of tourism in the Yellow River Basin. Arid Land Geogr. 2023, 46, 2074–2085. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Zhong, C.; Geng, Y.; Dong, F.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y. A bibliometric review of carbon footprint research. Carbon Footpr. 2024, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Ma, D.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, N.; Wang, L.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, J.; An, B.; Xiao, Y. Spatiotemporal differentiation of carbon emission efficiency and influencing factors: From the perspective of 136 countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 879, 163032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.Q.; Nie, M. Regional differences in the efficiency of industrial carbon emissions in China. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2012, 9, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Li, T.; Duan, X. Spatial and temporal evolution of urban CEE in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 114471–114483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Liu, X. Spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of urban CEE in China: Based on heterogeneous spatial stochastic frontier model. Geogr. Res. 2023, 42, 3182–3201. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, P.; Wang, Y.; Ye, T.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Chen, W. Carbon emission efficiency of 284 cities in China based on machine learning approach: Driving factors and regional heterogeneity. Energy Econ. 2024, 129, 107222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, N. Spatio-temporal evolution and influencing factors of carbon emission efficiency in low carbon city of China. J. Nat. Resour. 2022, 37, 1261–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, R.; Wang, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of carbon emission efficiency in the Yellow River Basin of China: Comparative analysis of resource and non-resource-based cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, X. Carbon emission efficiency measurement and influencing factor analysis of nine provinces in the Yellow River basin: Based on SBM-DDF model and Tobit-CCD model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 33263–33280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Liu, W. Analysis of the spatial–temporal evolution and driving factors of carbon emission efficiency in the Yangtze River economic Belt. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Su, C. Spatial-temporal evolution and driving factors of carbon emission efficiency of cities in the Yellow River Basin. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Sun, F.; Hu, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution, regional differences, and influencing factors of CEE in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2024, 33, 1325–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, R.; Cheng, Y. Impacts of innovation factor agglomeration on CEE in the Yellow River Basin. Geogr. Res. 2024, 43, 577–595. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, N.; Wang, C.; Yan, P. Provincial CEE and driving factors along the Belt and Road in China under carbon peak and carbon neutrality. Coal Eng. 2022, 54, 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Huang, X.; Chuai, X.; Sun, S. Spatio-temporal Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Carbon Emissions Efficiency in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2020, 29, 1486–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Shao, H. Spatiotemporal interactions and influencing factors for carbon emission efficiency of cities in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yin, J.; Wei, D.; Luo, X.; Ding, Y.; Xia, R. Industrial carbon emission efficiency prediction and carbon emission reduction strategies based on multi-objective particle swarm optimization-backpropagation: A perspective from regional clustering. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, K.; Li, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, C. Examining the impacts of network position on urban carbon emissions efficiency in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2023, 78, 2864–2882. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Hu, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B. Evaluation of the sustainable development level of the Belt and Road countries and its impact factors. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Tan, X.; Managi, S. Carbon neutrality commitment for China: From vision to action. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 1741–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.W. A perpetual inventory of national wealth. In Studies in Income and Wealth; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1951; Volume 14, pp. 5–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Recalculating the Capital of China and a Review of Li and Tang’s Article. Econ. Res. J. 2003, 7, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, H.J. Reestimating the capital stock of China: 1952–2006. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2008, 10, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 2589-2020; General Rules for Calculation of the Comprehensive Energy Consumption. Standardization Administration of PRC: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Long, L. Eco-Efficiency and Effectiveness Evaluation toward Sustainable Urban Development in China: A Super-Efficiency SBM–DEA with Undesirable Outputs. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 14982–14997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinniah, S.; Al Mamun, A.; Md Salleh, M.F.; Makhbul, Z.K.M.; Hayat, N. Modeling the Significance of Motivation on Job Satisfaction and Performance Among the Academicians: The Use of Hybrid Structural Equation Modeling–Artificial Neural Network Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 935822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Index | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Input indexes | Number of industry employee | Employment size (10,000 persons) |

| Energy resource | Fossil fuel consumption (10,000 tons standard coal) | |

| Desirable output index | GDP | Expressed by regional GDP (RMB 100 million), calculated at constant prices in 2000 |

| Undesirable output index | Carbon emission | Energy-consumption-related carbon emissions from each region (10,000 tons) |

| Types | NCVi [kJ/kg or kJ/m3] | CCi [kg/GJ] | COFi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coal | 20,934 | 26.37 | 0.90 |

| Coke | 28,470 | 29.5 | 0.90 |

| Crude oil | 41,868 | 20.1 | 0.98 |

| Gasoline | 43,124 | 18.90 | 0.98 |

| Kerosene | 43,124 | 19.60 | 0.98 |

| Diesel | 42,705 | 20.20 | 0.98 |

| Fuel oil | 41,868 | 21.1 | 0.98 |

| Natural gas | 38,931 | 15.32 | 0.99 |

| Variable | Variable Explanation | Unit | Winsorized | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population density (PD) | Total population of the region/administrative area | person/km2 | No | Characterize the population distribution characteristics of each province and region |

| Urbanization (UR) | Proportion of the urban population in the total population | % | No | Reflecting the degree of population agglomeration towards urban areas in a region |

| Economic development (ED) | Average nighttime light intensity per province (annual mean of DMSP/OLS and VIIRS data) | nW/cm2/sr | No | Measuring the economic output level of a region |

| Technological development (TD) | Technology expenditure/fiscal expenditure | % | No | Reflecting the government′s support for technological innovation and development |

| Energy consumption (EC) | Total energy consumption | 10,000 tons of standard coal | No | Reflecting the degree of dependence on coal for energy use |

| Foreign direct Investment (FDI) | Foreign direct investment/regional gross domestic product | % | No | Reflecting the dependence and impact of regional economy on foreign investment |

| Government intervention (GI) | Fiscal expenditure/regional gross domestic product | % | No | Reflecting the government’s regulation of social activities |

| Environmental regulation (ER) | Energy conservation and environmental protection fiscal expenditure/fiscal expenditure | % | No | Measures the government’s investment in energy conservation and environmental governance, reflecting regulatory commitment and implementation intensity. |

| Industrial structure (IS) | Value added of the tertiary industry/Value added of the secondary industry | % | No | Important indicators of economic development |

| Environmental protection (EP) | Environmental protection expenditure/fiscal expenditure | % | No | Indicates the intensity of government investment specifically in pollution control, ecological restoration, and waste management. |

| Provinces | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0.561 | 0.585 | 0.586 | 0.608 | 0.623 | 0.636 | 0.685 | 0.700 | 0.729 | 0.823 | 0.879 | 1.000 | 1.043 | 1.026 | 0.749 |

| Tianjin | 0.494 | 0.500 | 0.494 | 0.496 | 0.494 | 0.497 | 0.528 | 0.549 | 0.546 | 0.443 | 0.447 | 0.474 | 0.496 | 0.483 | 0.496 |

| Hebei | 0.247 | 0.256 | 0.248 | 0.243 | 0.236 | 0.223 | 0.226 | 0.228 | 0.232 | 0.22 | 0.221 | 0.237 | 0.247 | 0.216 | 0.234 |

| Shanxi | 0.286 | 0.29 | 0.277 | 0.261 | 0.247 | 0.239 | 0.235 | 0.261 | 0.274 | 0.273 | 0.278 | 0.330 | 0.360 | 0.311 | 0.280 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.296 | 0.305 | 0.297 | 0.289 | 0.286 | 0.275 | 0.272 | 0.251 | 0.257 | 0.256 | 0.259 | 0.294 | 0.320 | 0.288 | 0.282 |

| Liaoning | 0.286 | 0.297 | 0.293 | 0.292 | 0.286 | 0.287 | 0.241 | 0.249 | 0.262 | 0.256 | 0.256 | 0.276 | 0.291 | 0.281 | 0.275 |

| Jilin | 0.323 | 0.308 | 0.312 | 0.322 | 0.324 | 0.339 | 0.348 | 0.348 | 0.344 | 0.293 | 0.302 | 0.315 | 0.320 | 0.304 | 0.322 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.340 | 0.342 | 0.328 | 0.315 | 0.310 | 0.309 | 0.305 | 0.305 | 0.308 | 0.270 | 0.273 | 0.283 | 0.299 | 0.284 | 0.305 |

| Shanghai | 0.469 | 0.459 | 0.459 | 0.466 | 0.456 | 0.463 | 0.489 | 0.504 | 0.515 | 0.569 | 0.571 | 0.639 | 0.698 | 0.702 | 0.533 |

| Jiangsu | 0.312 | 0.368 | 0.393 | 0.423 | 0.482 | 0.518 | 0.576 | 0.647 | 0.702 | 0.756 | 0.78 | 0.916 | 1.091 | 1.021 | 0.642 |

| Zhejiang | 0.328 | 0.345 | 0.344 | 0.346 | 0.347 | 0.358 | 0.406 | 0.457 | 0.507 | 0.585 | 0.587 | 0.697 | 0.741 | 0.659 | 0.479 |

| Anhui | 0.310 | 0.323 | 0.317 | 0.311 | 0.309 | 0.297 | 0.300 | 0.307 | 0.316 | 0.360 | 0.373 | 0.401 | 0.418 | 0.352 | 0.335 |

| Fujian | 0.344 | 0.350 | 0.349 | 0.350 | 0.348 | 0.350 | 0.361 | 0.373 | 0.386 | 0.437 | 0.458 | 0.544 | 0.625 | 0.549 | 0.416 |

| Jiangxi | 0.357 | 0.375 | 0.373 | 0.373 | 0.376 | 0.369 | 0.373 | 0.376 | 0.384 | 0.403 | 0.399 | 0.422 | 0.434 | 0.345 | 0.383 |

| Shandong | 0.259 | 0.281 | 0.299 | 0.326 | 0.346 | 0.352 | 0.396 | 0.424 | 0.447 | 0.394 | 0.403 | 0.474 | 0.506 | 0.468 | 0.384 |

| Henan | 0.244 | 0.243 | 0.236 | 0.235 | 0.232 | 0.230 | 0.236 | 0.263 | 0.292 | 0.354 | 0.352 | 0.383 | 0.399 | 0.320 | 0.287 |

| Hubei | 0.293 | 0.306 | 0.302 | 0.308 | 0.308 | 0.310 | 0.316 | 0.320 | 0.331 | 0.393 | 0.360 | 0.442 | 0.489 | 0.426 | 0.350 |

| Hunan | 0.316 | 0.329 | 0.323 | 0.327 | 0.327 | 0.332 | 0.337 | 0.344 | 0.351 | 0.364 | 0.377 | 0.440 | 0.479 | 0.416 | 0.362 |

| Guangdong | 0.801 | 1.019 | 0.449 | 0.483 | 0.515 | 0.545 | 0.606 | 0.677 | 0.732 | 0.849 | 0.827 | 1.006 | 1.026 | 1.028 | 0.754 |

| Guangxi | 0.286 | 0.282 | 0.27 | 0.273 | 0.272 | 0.274 | 0.276 | 0.272 | 0.282 | 0.284 | 0.282 | 0.295 | 0.307 | 0.293 | 0.282 |

| Hainan | 1.155 | 0.941 | 0.868 | 0.826 | 0.806 | 0.777 | 0.778 | 0.776 | 0.779 | 0.800 | 0.795 | 0.827 | 0.871 | 0.757 | 0.8400 |

| Chongqing | 0.364 | 0.378 | 0.379 | 0.389 | 0.389 | 0.404 | 0.413 | 0.417 | 0.411 | 0.443 | 0.473 | 0.495 | 0.507 | 0.438 | 0.421 |

| Sichuan | 0.290 | 0.302 | 0.304 | 0.307 | 0.306 | 0.306 | 0.312 | 0.328 | 0.338 | 0.414 | 0.469 | 0.544 | 0.593 | 0.544 | 0.383 |

| Guizhou | 0.316 | 0.322 | 0.323 | 0.320 | 0.318 | 0.318 | 0.311 | 0.317 | 0.314 | 0.324 | 0.327 | 0.336 | 0.336 | 0.303 | 0.32 |

| Yunnan | 0.288 | 0.283 | 0.272 | 0.269 | 0.258 | 0.254 | 0.249 | 0.251 | 0.251 | 0.288 | 0.284 | 0.296 | 0.300 | 0.255 | 0.271 |

| Shaanxi | 0.314 | 0.323 | 0.321 | 0.320 | 0.321 | 0.305 | 0.305 | 0.315 | 0.326 | 0.325 | 0.320 | 0.341 | 0.354 | 0.302 | 0.321 |

| Gansu | 0.363 | 0.367 | 0.359 | 0.351 | 0.342 | 0.319 | 0.314 | 0.312 | 0.326 | 0.334 | 0.334 | 0.353 | 0.367 | 0.308 | 0.339 |

| Qinghai | 1.112 | 1.009 | 1.013 | 0.975 | 0.962 | 0.886 | 0.877 | 0.850 | 0.845 | 0.865 | 0.885 | 0.876 | 1.037 | 0.861 | 0.932 |

| Ningxia | 0.637 | 0.604 | 0.591 | 0.573 | 0.556 | 0.533 | 0.529 | 0.507 | 0.504 | 0.494 | 0.490 | 0.529 | 0.578 | 0.507 | 0.545 |

| Xinjiang | 0.335 | 0.334 | 0.317 | 0.298 | 0.283 | 0.259 | 0.246 | 0.246 | 0.258 | 0.269 | 0.263 | 0.280 | 0.302 | 0.239 | 0.281 |

| Mean | 0.411 | 0.414 | 0.390 | 0.389 | 0.389 | 0.386 | 0.395 | 0.406 | 0.418 | 0.438 | 0.444 | 0.492 | 0.528 | 0.476 | —— |

| Median | 0.319 | 0.332 | 0.323 | 0.324 | 0.326 | 0.325 | 0.326 | 0.336 | 0.341 | 0.379 | 0.375 | 0.431 | 0.457 | 0.384 | —— |

| Region | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationwide | 0.411 | 0.414 | 0.390 | 0.389 | 0.389 | 0.386 | 0.395 | 0.406 | 0.418 | 0.438 | 0.444 | 0.492 | 0.528 | 0.476 |

| Northern Coastal | 0.390 | 0.406 | 0.407 | 0.418 | 0.425 | 0.427 | 0.458 | 0.475 | 0.488 | 0.470 | 0.487 | 0.546 | 0.573 | 0.548 |

| Central Yellow River | 0.285 | 0.290 | 0.283 | 0.276 | 0.271 | 0.262 | 0.262 | 0.272 | 0.287 | 0.302 | 0.302 | 0.337 | 0.358 | 0.305 |

| Northeast | 0.316 | 0.316 | 0.311 | 0.310 | 0.307 | 0.312 | 0.298 | 0.301 | 0.304 | 0.273 | 0.277 | 0.291 | 0.303 | 0.290 |

| Central Yangtze River | 0.319 | 0.334 | 0.328 | 0.330 | 0.330 | 0.327 | 0.331 | 0.337 | 0.346 | 0.380 | 0.377 | 0.426 | 0.455 | 0.385 |

| Southern Coastal | 0.766 | 0.770 | 0.555 | 0.553 | 0.556 | 0.557 | 0.581 | 0.609 | 0.632 | 0.695 | 0.693 | 0.792 | 0.841 | 0.778 |

| Eastern Coastal | 0.370 | 0.391 | 0.399 | 0.412 | 0.428 | 0.446 | 0.490 | 0.536 | 0.575 | 0.637 | 0.646 | 0.751 | 0.843 | 0.794 |

| Southwest | 0.309 | 0.314 | 0.310 | 0.312 | 0.309 | 0.311 | 0.312 | 0.317 | 0.319 | 0.351 | 0.367 | 0.393 | 0.409 | 0.367 |

| Northwest | 0.612 | 0.579 | 0.570 | 0.549 | 0.536 | 0.499 | 0.492 | 0.479 | 0.483 | 0.491 | 0.493 | 0.510 | 0.571 | 0.479 |

| Province | 2010–2011 | 2014–2015 | 2018–2019 | 2022–2023 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 1.044 | 1.005 | 1.039 | 1.022 | 0.998 | 1.024 | 1.128 | 1.011 | 1.116 | 0.984 | 0.986 | 0.997 |

| Tianjin | 1.013 | 1.219 | 0.831 | 1.006 | 1.001 | 1.005 | 0.810 | 0.515 | 1.574 | 0.974 | 1.060 | 0.920 |

| Hebei | 1.037 | 1.031 | 1.006 | 0.949 | 0.920 | 1.032 | 0.950 | 0.781 | 1.217 | 0.872 | 0.955 | 0.913 |

| Shanxi | 1.016 | 0.996 | 1.021 | 0.969 | 0.961 | 1.008 | 0.998 | 0.923 | 1.082 | 0.865 | 1.018 | 0.850 |

| Inner Mongolia | 1.029 | 1.007 | 1.021 | 0.962 | 0.950 | 1.013 | 0.995 | 0.929 | 1.072 | 0.900 | 1.008 | 0.893 |

| Liaoning | 1.038 | 1.031 | 1.007 | 1.004 | 0.947 | 1.060 | 0.978 | 0.893 | 1.095 | 0.969 | 1.132 | 0.855 |

| Jilin | 0.955 | 0.938 | 1.018 | 1.047 | 1.041 | 1.005 | 0.852 | 0.790 | 1.079 | 0.950 | 1.062 | 0.895 |

| Heilongjiang | 1.008 | 0.982 | 1.027 | 0.997 | 0.979 | 1.019 | 0.879 | 0.812 | 1.082 | 0.948 | 1.073 | 0.884 |

| Shanghai | 0.978 | 0.942 | 1.038 | 1.017 | 0.983 | 1.034 | 1.104 | 1.013 | 1.090 | 1.005 | 1.012 | 0.993 |

| Jiangsu | 1.179 | 1.015 | 1.162 | 1.075 | 1.007 | 1.067 | 1.078 | 0.986 | 1.093 | 0.936 | 1.002 | 0.935 |

| Zhejiang | 1.051 | 1.023 | 1.027 | 1.029 | 0.980 | 1.051 | 1.155 | 0.970 | 1.191 | 0.890 | 0.967 | 0.920 |

| Anhui | 1.044 | 1.041 | 1.003 | 0.961 | 0.957 | 1.004 | 1.138 | 1.065 | 1.069 | 0.841 | 0.914 | 0.921 |

| Fujian | 1.017 | 0.997 | 1.020 | 1.007 | 1.001 | 1.006 | 1.133 | 1.039 | 1.090 | 0.878 | 0.912 | 0.962 |

| Jiangxi | 1.051 | 1.069 | 0.983 | 0.982 | 0.709 | 1.385 | 1.050 | 0.954 | 1.100 | 0.795 | 0.915 | 0.869 |

| Shandong | 1.086 | 1.010 | 1.075 | 1.018 | 0.975 | 1.044 | 0.883 | 0.795 | 1.110 | 0.925 | 1.027 | 0.901 |

| Henan | 0.995 | 0.983 | 1.012 | 0.992 | 0.987 | 1.005 | 1.211 | 1.011 | 1.198 | 0.801 | 0.853 | 0.939 |

| Hubei | 1.043 | 1.040 | 1.002 | 1.008 | 1.012 | 0.996 | 1.188 | 1.008 | 1.178 | 0.870 | 0.928 | 0.938 |

| Hunan | 1.042 | 1.028 | 1.013 | 1.014 | 1.010 | 1.005 | 1.037 | 0.899 | 1.153 | 0.867 | 0.934 | 0.929 |

| Guangdong | 1.273 | 0.987 | 1.290 | 1.057 | 0.991 | 1.067 | 1.159 | 1.008 | 1.150 | 1.002 | 0.983 | 1.020 |

| Guangxi | 0.987 | 0.968 | 1.019 | 1.007 | 0.986 | 1.022 | 1.005 | 0.919 | 1.093 | 0.957 | 1.121 | 0.854 |

| Hainan | 0.815 | 1.041 | 0.783 | 0.964 | 1.069 | 0.902 | 1.027 | 0.977 | 1.051 | 0.869 | 0.971 | 0.896 |

| Chongqing | 1.040 | 1.028 | 1.012 | 1.038 | 1.041 | 0.998 | 1.078 | 0.983 | 1.096 | 0.865 | 0.980 | 0.883 |

| Sichuan | 1.039 | 1.042 | 0.998 | 1.003 | 0.993 | 1.010 | 1.224 | 0.996 | 1.229 | 0.918 | 1.008 | 0.911 |

| Guizhou | 1.021 | 1.021 | 1.000 | 1.002 | 1.018 | 0.984 | 1.033 | 0.954 | 1.083 | 0.900 | 1.039 | 0.866 |

| Yunnan | 0.983 | 0.970 | 1.013 | 0.982 | 0.968 | 1.014 | 1.147 | 1.062 | 1.080 | 0.852 | 0.972 | 0.876 |

| Shaanxi | 1.027 | 1.001 | 1.026 | 0.950 | 0.937 | 1.014 | 0.996 | 0.908 | 1.098 | 0.853 | 0.969 | 0.880 |

| Gansu | 1.010 | 1.013 | 0.997 | 0.933 | 0.946 | 0.986 | 1.025 | 0.971 | 1.055 | 0.838 | 0.961 | 0.872 |

| Qinghai | 0.907 | 1.007 | 0.901 | 0.921 | 0.980 | 0.940 | 1.024 | 1.015 | 1.008 | 0.830 | 0.984 | 0.843 |

| Ningxia | 0.948 | 0.992 | 0.955 | 0.959 | 1.009 | 0.950 | 0.979 | 0.959 | 1.022 | 0.878 | 0.601 | 1.461 |

| Xinjiang | 0.998 | 0.985 | 1.013 | 0.914 | 0.918 | 0.996 | 1.043 | 0.976 | 1.069 | 0.793 | 0.888 | 0.893 |

| Mean | 1.022 | 1.014 | 1.010 | 0.993 | 0.976 | 1.022 | 1.044 | 0.937 | 1.121 | 0.894 | 0.974 | 0.926 |

| Regions | 2010–2011 | 2014–2015 | 2018–2019 | 2022–2023 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Coastal | 1.045 | 1.066 | 0.988 | 0.999 | 0.973 | 1.026 | 0.943 | 0.776 | 1.254 | 0.939 | 1.007 | 0.933 |

| Eastern Coastal | 1.069 | 0.993 | 1.076 | 1.040 | 0.990 | 1.051 | 1.112 | 0.990 | 1.124 | 0.944 | 0.994 | 0.949 |

| Southern Coastal | 1.035 | 1.008 | 1.031 | 1.010 | 1.021 | 0.992 | 1.106 | 1.008 | 1.097 | 0.916 | 0.955 | 0.959 |

| Central Yellow River | 1.017 | 0.997 | 1.020 | 0.968 | 0.959 | 1.010 | 1.050 | 0.942 | 1.112 | 0.855 | 0.962 | 0.890 |

| Northeast | 1.000 | 0.983 | 1.018 | 1.016 | 0.989 | 1.028 | 0.903 | 0.831 | 1.085 | 0.956 | 1.089 | 0.878 |

| Central Yangtze River | 1.045 | 1.045 | 1.000 | 0.991 | 0.922 | 1.098 | 1.103 | 0.982 | 1.125 | 0.844 | 0.923 | 0.914 |

| Northwest | 0.966 | 0.999 | 0.967 | 0.932 | 0.963 | 0.968 | 1.018 | 0.980 | 1.039 | 0.835 | 0.859 | 1.017 |

| Southwest | 1.014 | 1.006 | 1.008 | 1.007 | 1.001 | 1.006 | 1.097 | 0.983 | 1.116 | 0.898 | 1.024 | 0.878 |

| National wide | 1.022 | 1.014 | 1.010 | 0.993 | 0.976 | 1.022 | 1.044 | 0.937 | 1.121 | 0.894 | 0.975 | 0.926 |

| Variables | National wide | Northern Coastal | Eastern Coastal | Southern Coastal | Central Yellow River | Northeast | Central Yangtze River | Northwest | Southwest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technological development (TD) | 0.5045 *** | 1.2819 *** | −0.2527 *** | 0.4217 ** | 0.3786 *** | −0.0574 | 0.3683 *** | −0.3023 *** | 0.3930 *** |

| (0.0598) | (0.0651) | (0.0816) | (0.1820) | (0.1272) | (0.5167) | (0.1311) | (0.0961) | (0.0851) | |

| Economic development (ED) | 0.2054 *** | 0.6289 *** | 0.4427 | 0.2893 ** | 0.4680 *** | −0.6085 ** | 0.2090 | −0.9180 *** | 0.3359 *** |

| (0.0590) | (0.0687) | (0.3046) | (0.1385) | (0.1221) | (0.2880) | (0.2923) | (0.0783) | (0.0804) | |

| Industrial structure (IS) | 0.2144 *** | 0.3278 | 0.7338 *** | 1.2684 *** | −0.3028 *** | −0.6722 *** | 0.6615 *** | −0.3929 *** | 0.0677 |

| (0.0526) | (0.2947) | (0.1739) | (0.1500) | (0.0791) | (0.1333) | (0.1288) | (0.0613) | (0.1991) | |

| Environmental protection (EP) | 0.1848 *** | −0.0821 | −0.1808 ** | 0.1822 ** | 0.3006 *** | 0.1684 | −0.3497 *** | 0.4936 * | 0.2010 ** |

| (0.0419) | (0.1552) | (0.0879) | (0.0889) | (0.0816) | (0.1939) | (0.0631) | (0.2700) | (0.0933) | |

| Population density (PD) | −0.1260 ** | 0.2313 | −1.0401 *** | −1.9260 *** | −0.3471 ** | 0.4857 ** | −0.4522 *** | 0.5260 *** | 0.5096 *** |

| (0.0564) | (0.4955) | (0.2967) | (0.4649) | (0.1486) | (0.2247) | (0.0927) | (0.1004) | (0.1388) | |

| Energy consumption (EC) | −0.1235 *** | −0.0894 | 0.7711 *** | 2.5080 *** | −0.0925 | −1.7493 *** | −0.2213 ** | −0.4123 | 0.5178 *** |

| (0.0450) | (0.2126) | (0.1503) | (0.5183) | (0.1572) | (0.4099) | (0.0942) | (0.5410) | (0.1046) | |

| Environmental regulation (ER) | 0.0241 | 0.0767 ** | 0.1096 | 0.4721 *** | −0.2203 ** | −0.0144 | −0.1495 ** | 0.2369 *** | 0.1965 ** |

| (0.0407) | (0.0366) | (0.0912) | (0.0939) | (0.0920) | (0.1493) | (0.0708) | (0.0709) | (0.1001) | |

| Government intervention (GI) | 0.0870 * | 0.0096 | −0.5180 *** | −0.2383 | −0.2451 ** | 0.2495 | 0.2977 ** | −0.3907 *** | 0.0249 |

| (0.0479) | (0.1728) | (0.1385) | (0.2026) | (0.1198) | (0.1631) | (0.1345) | (0.0818) | (0.1276) | |

| Urbanization (UR) | −0.1093 | −0.7625 *** | 1.5206 *** | 0.3526 | 0.1496 | 0.6939 ** | 0.2931 | 1.3966 *** | 0.2418 |

| (0.0785) | (0.1081) | (0.3469) | (0.3015) | (0.5408) | (0.3331) | (0.1146) | (0.0937) | (0.3580) | |

| Foreign direct investment (FDI) | 0.0696 | 0.1244 *** | −0.1748 | 0.2703 *** | −0.0816 | −0.2364 ** | 0.1977 *** | 0.0965 | −0.1712 ** |

| (0.0469) | (0.0443) | (0.2549) | (0.0802) | (0.1490) | (0.1135) | (0.0659) | (0.1391) | (0.0678) |

| Variables | Baseline Tobit | Lagged Tobit (L1) | Mundlak Mean (m_) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technological development (TD) | 0.500 *** | 0.073 *** | 0.083 * |

| Economic development (ED) | 0.259 *** | 0.042 * | −0.035 |

| Industrial structure (IS) | 0.208 *** | 0.021 | 0.009 |

| Environmental protection (EP) | 0.145 *** | −0.028 *** | 0.058 ** |

| Population density (PD) | 0.127 ** | 1.194 *** | −1.243 * |

| Energy consumption (EC) | −0.095 *** | −0.038 * | −0.038 |

| Environmental Regulation (ER) | 0.055 | −0.002 | 0.021 ** |

| Government intervention (GI) | 0.043 | −0.014 | 0.071 * |

| Urbanization (UR) | 0.026 | −0.002 * | 0.015 |

| Foreign direct Investment (FDI) | 0.014 | 0.005 | −0.006 |

| Period | TD | ED | IS | EP | PD | EC | ER | GI | UR | FDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical | 0.505 *** | 0.205 *** | 0.214 *** | 0.185 *** | −0.126 ** | −0.124 *** | 0.024 | 0.087 * | −0.109 | 0.070 |

| (0.060) | (0.059) | (0.053) | (0.042) | (0.056) | (0.045) | (0.041) | (0.048) | (0.079) | (0.047) | |

| Forward | 0.500 *** | 0.259 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.145 *** | −0.127 ** | −0.095 ** | 0.055 | 0.043 | −0.037 | −0.004 |

| (0.053) | (0.055) | (0.048) | (0.038) | (0.051) | (0.042) | (0.038) | (0.045) | (0.070) | (0.042) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, Y.; Li, H. Carbon Emission Efficiency in China (2010–2025): Dual-Scale Analysis, Drivers, and Forecasts Across the Eight Comprehensive Economic Zones. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10007. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210007

Shen Y, Li H. Carbon Emission Efficiency in China (2010–2025): Dual-Scale Analysis, Drivers, and Forecasts Across the Eight Comprehensive Economic Zones. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10007. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210007

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Yue, and Haibo Li. 2025. "Carbon Emission Efficiency in China (2010–2025): Dual-Scale Analysis, Drivers, and Forecasts Across the Eight Comprehensive Economic Zones" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10007. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210007

APA StyleShen, Y., & Li, H. (2025). Carbon Emission Efficiency in China (2010–2025): Dual-Scale Analysis, Drivers, and Forecasts Across the Eight Comprehensive Economic Zones. Sustainability, 17(22), 10007. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210007