A Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Human Resource Management: Integrating Green Practices, Ethical Leadership, and Digital Resilience to Advance the SDGs

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Synthesize fragmented literature on Green HRM, Ethical Leadership, and Digital Resilience into a unified conceptual structure.

- (2)

- Articulate theoretical linkages and propositions connecting HRM practices to employee well-being and sustainability outcomes.

- (3)

- Outline a future research agenda to guide empirical validation across sectors and contexts.

- (1)

- It introduces an integrative theoretical model that bridges ethics, digitalization, and sustainability within HRM.

- (2)

- It advances a multi-level (micro–meso–macro) conceptualization of Sustainable HRM, linking individual, organizational, and societal outcomes.

- (3)

- It provides a foundation for empirical validation through future cross-sectoral and cross-national studies.

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Conceptual Background of Sustainable HRM

2.2. Core Theoretical Lenses for Sustainable HRM

2.3. Summary and Integrative Insights

3. Conceptual Development Approach (Methodology)

3.1. Rationale for a Conceptual Article

3.2. Process of Conceptual Development

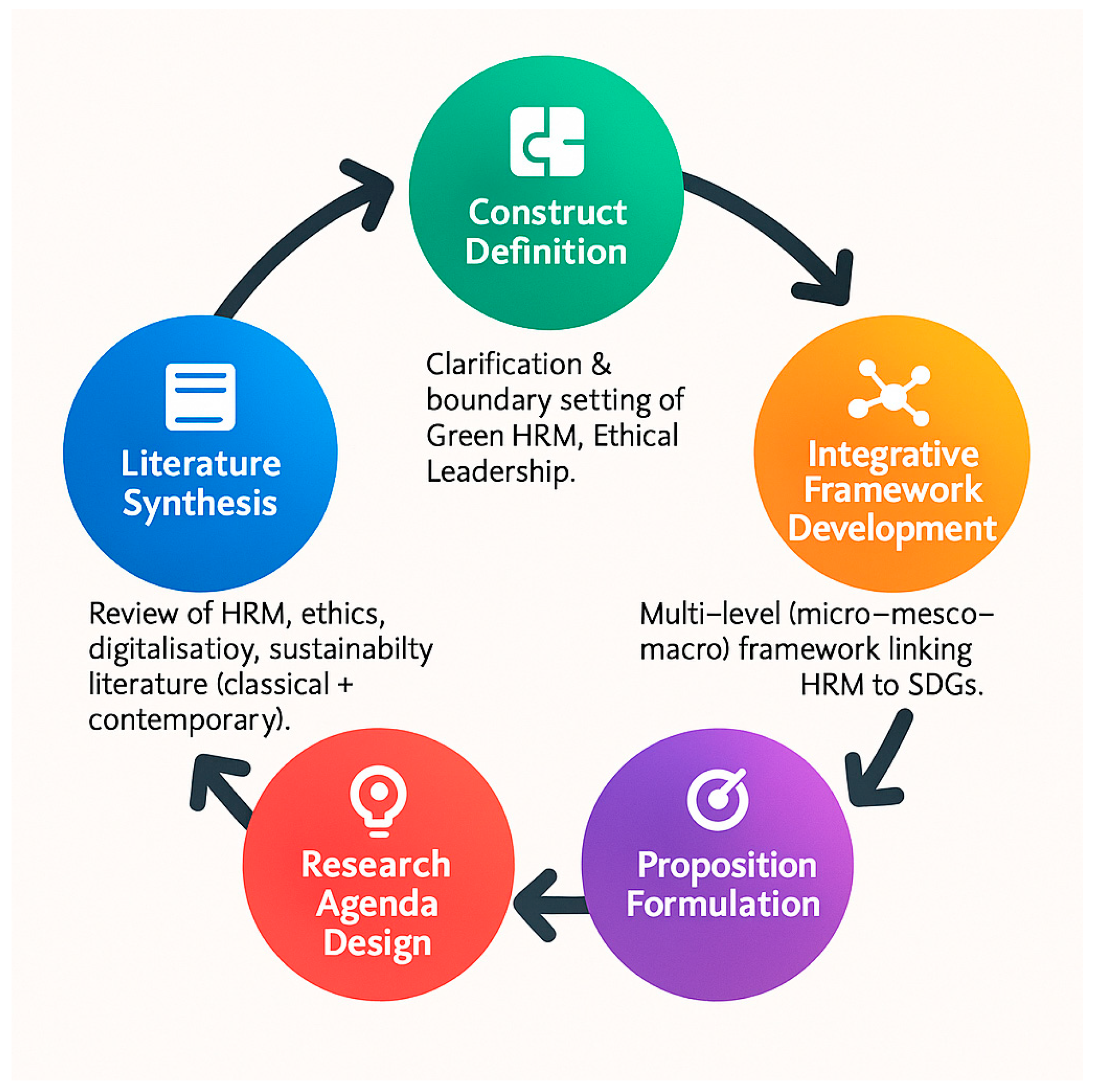

3.3. Visualization of the Methodological Approach

3.4. Positioning Within HRM and Sustainability Research

4. Key Constructs

4.1. Core Constructs: Green, Ethical, and Digital Dimensions

4.2. Mediating and Outcome Variables: Employee Well-Being and Sustainability Outcomes

4.3. Integrative Summary and Implications for Framework Development

5. Conceptual Framework

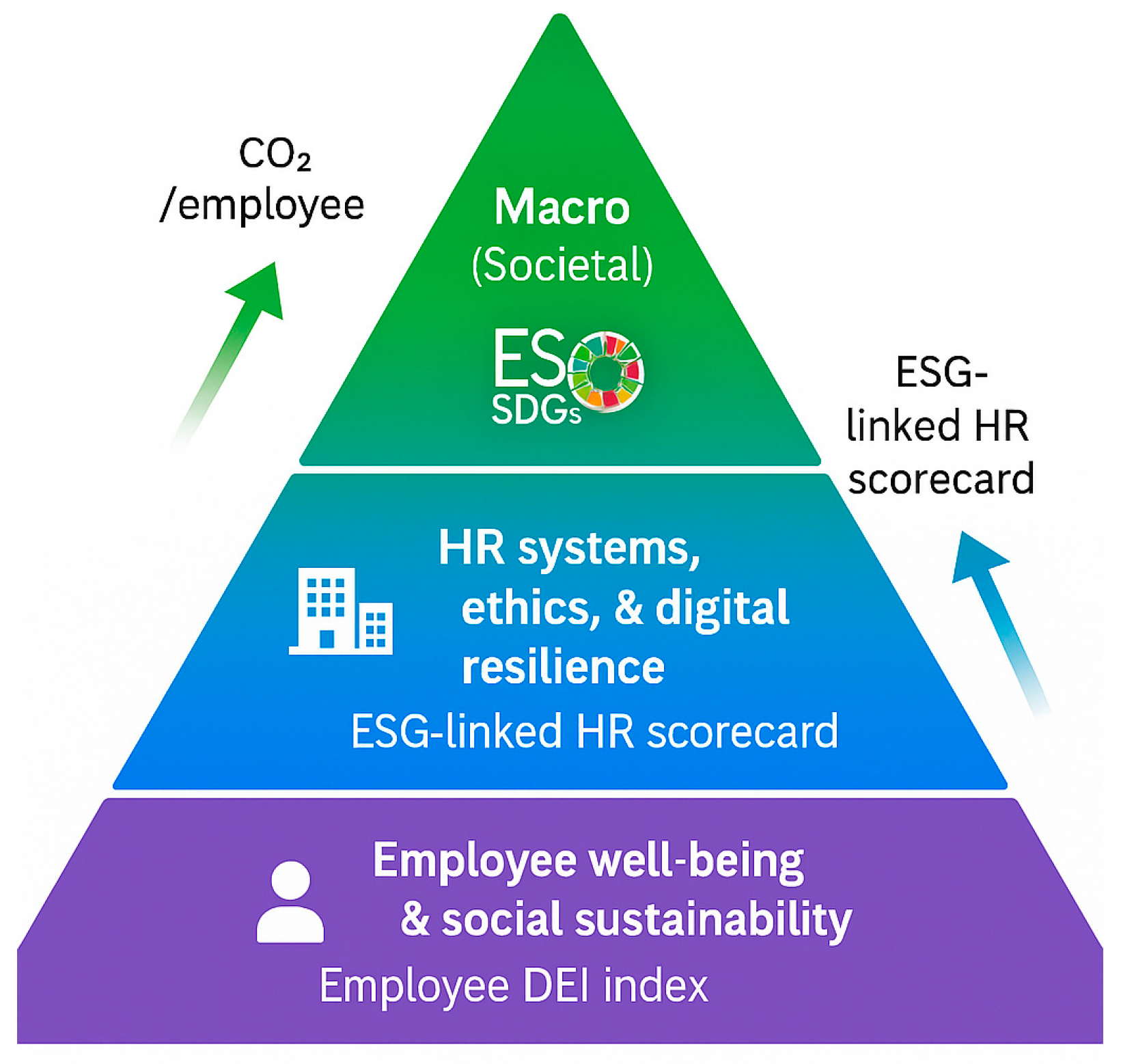

5.1. Multi-Level Integration

5.2. Flow of Relationships

5.3. Visual Framework

5.4. Framing for Reviewers

6. Propositions & Research Agenda

6.1. Conceptual Propositions

6.2. Flow of Relationships

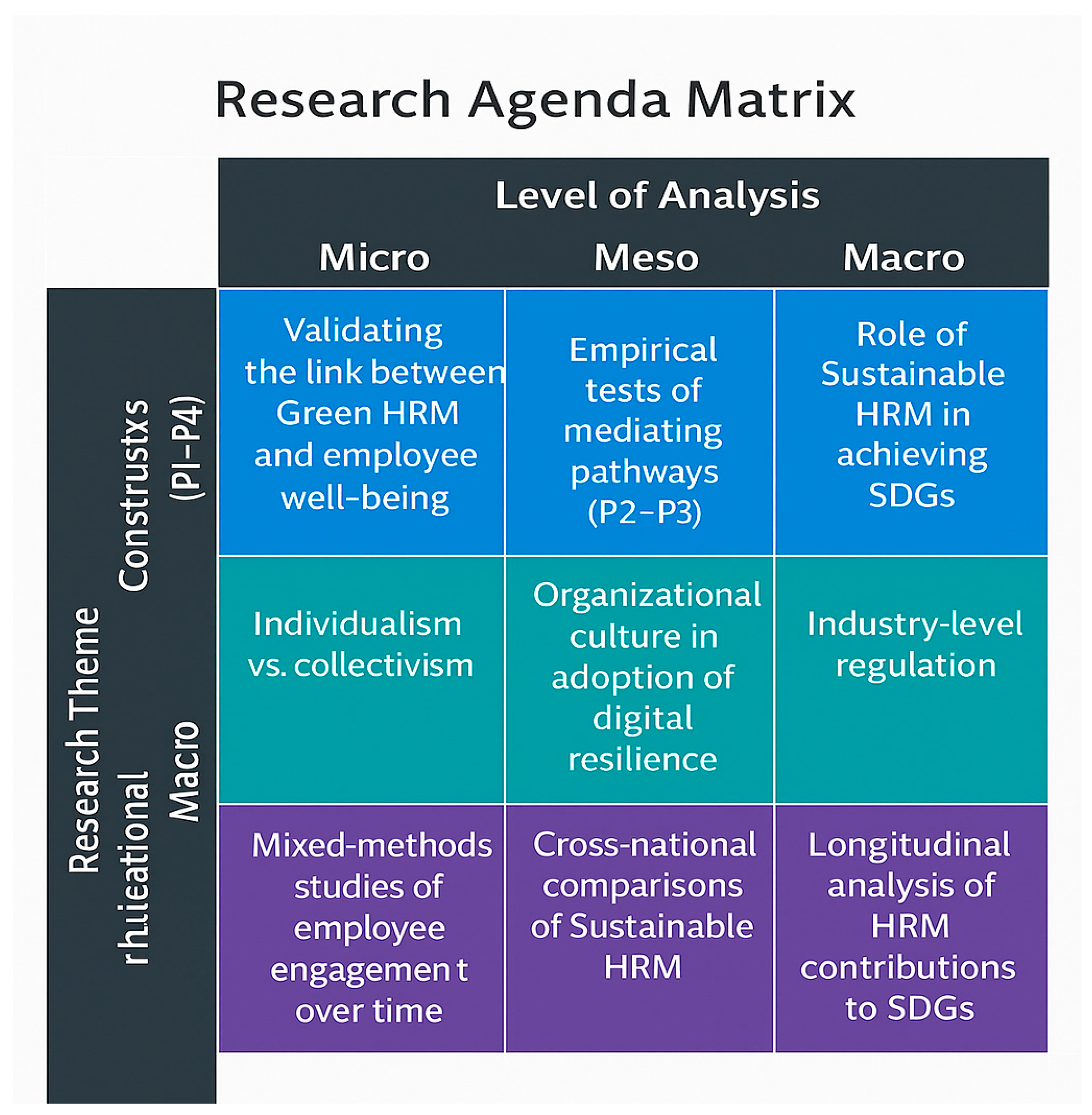

6.3. Research Agenda Matrix

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

- ▪

- Manufacturing: Align green recruitment and training with carbon reduction targets.

- ▪

- Hospitality: Foster employee engagement in sustainable service practices and digital transparency in HR systems.

- ▪

- Higher education: Embed sustainability competencies and ethical leadership development into faculty and staff management.

7.3. Policy Implications

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| HRM | Human Resource Management |

| Green HRM (GHRM) | Green Human Resource Management |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| RBV | Resource-Based View |

| SET | Social Exchange Theory |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

References

- Ehnert, I.; Parsa, S.; Roper, I.; Wagner, M.; Muller-Camen, M. Reporting on sustainability and HRM: A comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world’s largest companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, C.; Brookes, M. Sustainable development goals and new approaches to HRM: Why HRM specialists will not reach the sustainable development goals and why it matters. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Z. Pers. 2024, 38, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, J.W.; Nafees, L.; Westerman, J. Cultivating Support for the Sustainable Development Goals, Green Strategy and Human Resource Management Practices in Future Business Leaders: The Role of Individual Differences and Academic Training. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banga, C.M.; Gobind, J. Implementation of sustainability in human resource management: A literature review. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2025, 23, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Muller-Camen, M.; Redman, T.; Wilkinson, A. Contemporary developments in Green (environmental) HRM scholarship. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.; Szabó-Szentgróti, G.; Walter, V. A systematic literature review on green human resource management (GHRM): An organizational sustainability perspective. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2371983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, A.S.A.; Alshammrei, S.; Nawaz, N.; Tayyab, M. Green Human Resource Management and Sustainable Performance with the Mediating Role of Green Innovation: A Perspective of New Technological Era. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 901235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostu, S.-A.; Gigauri, I. Mapping the Link Between Human Resource Management and Sustainability: The Pathway to Sustainable Competitiveness. In Reshaping Performance Management for Sustainable Development; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, A.A.; Uddin, M.A.; Rana, T.; Biswas, S.R.; Dey, M. Socially responsible human resource management for sustainable performance in a moderated mediation mechanism. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalvo-Falcón, J.V.; Sánchez-García, E.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Martínez-Falcó, J. Green human resource management and economic, social and environmental performance: Evidence from the Spanish wine industry. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, M.M.; Yang, M.M.; Wang, Y. Sustainable human resource management practices, employee resilience, and employee outcomes: Toward common good values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 62, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Green Human Resource Management: Policies and practices. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2015, 2, 1030817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Paillé, P.; Jia, J. Green human resource management practices: Scale development and validity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 56, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangwal, D.; Chaudhary, A.; Kumar, R.; Oberoi, S.S.; Kumar, V. Green HRM, employee pro-environmental behavior, and environmental commitment. Acta Psychol. 2025, 258, 105153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J. Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-J.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, T.-H. ‘The Power of Ethical Leadership’: The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Creativity, the Mediating Function of Psychological Safety, and the Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serviss, E.R.; Manix, K.G.; Oglesby, M.T.; Howard, M.C.; Gleim, M.R. Ethical leadership in a remote working context: Implications for salesperson well-being and performance. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2025, 45, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Gutiérrez, F.J.; Stone, D.L.; Castaño, A.M.; García-Izquierdo, A.L. Human Resources Analytics: A systematic Review from a Sustainable Management Approach | La analítica de recursos humanos: Una revisión sistemática desde la perspectiva de una gestión sostenible. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Y Organ. 2022, 38, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Ferreira, M.R. Where Is Human Resource Management in Sustainability Reporting? ESG and GRI Perspectives. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutaula, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Gillani, A.; Budhwar, P.S.; Dey, P.K. Linking HRM with Sustainability Performance Through Sustainability Practices: Unlocking the Black Box. Br. J. Manag. 2025, 36, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E. Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Sustainable human resource management: Six defining characteristics. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2022, 60, 146–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soekotjo, S.; Sosidah, S.; Kuswanto, H.; Setyadi, A.; Pawirosumarto, S. A Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Human Resource Management: Integrating Ecological and Inclusive Perspectives. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. SDG Actions Platform. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- United Nations. THE 17 GOALS. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, J.; Unerman, J. Achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Christ, K.L.; Wenzig, J.; Burritt, R.L. Corporate sustainability management accounting and multi-level links for sustainability—A systematic review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2022, 24, 480–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhayawansa, S.; Adams, C.A.; Neesham, C. Accountability and governance in pursuit of Sustainable Development Goals: Conceptualising how governments create value. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2021, 34, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. Sustainability Reporting and Value Creation. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2020, 40, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Kaur, K.; Patel, P.; Kumar, S.; Prikshat, V. Integrating sustainable development goals into HRM in emerging markets: An empirical investigation of Indian and Chinese banks. Int. J. Manpow. 2025, 46, 792–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Sakib, M.N.; Sanju, N.L.; Sabah, S.; Chowdhury, F.; Rahman, M.M. Aspects and practices of green human resource management: A review of literature exploring future research direction. Future Bus. J. 2025, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-García, I.; Alonso-Muñoz, S.; González-Sánchez, R.; Medina-Salgado, M. Human resource management and sustainability: Bridging the 2030 agenda. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 2033–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Decramer, A.; Van Waeyenberg, T.; Aust, I. Moving Beyond the Link Between HRM and Economic Performance: A Study on the Individual Reactions of HR Managers and Professionals to Sustainable HRM. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevene, P.; Buonomo, I. Green Human Resource Management: An Evidence-Based Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farndale, E.; Paauwe, J. SHRM and context: Why firms want to be as different as legitimately possible. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2018, 5, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, C.; Mayrhofer, W.; Smale, A. Crossing the streams: HRM in multinational enterprises and comparative HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, P. Conceptual and methodological issues in international and comparative HRM: Transferring lessons from comparative public policy. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2024, 34, 101015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, A.; Sanders, K.; Hu, J. The Sustainable Human Resource Practices and Employee Outcomes Link: An HR Process Lens. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, F.L.; Dickmann, M.; Parry, E. Building sustainable societies through human-centred human resource management: Emerging issues and research opportunities. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Cooke, F.L.; Stahl, G.K.; Fan, D.; Timming, A.R. Advancing the sustainability agenda through strategic human resource management: Insights and suggestions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 62, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, N. Innovative Human Resource Management Strategies for Circular Economy Transition: Comparative Insights from Portugal and Sweden. Merits 2025, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, P.; Parajuli, D.; Upadhyay, J.P. Determinants and Challenges of Green Human Resource Management Practices in Small and Medium Scale Industries. SMS J. Enterpreneurship Innov. 2022, 9, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savanevičienė, A.; Salickaitė-Žukauskienė, R.; Šilingienė, V.; Bilan, S. Ensuring sustainable human resource management during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Lithuanian catering organisations. Econ. Sociol. 2022, 15, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresia, F. The Contribution of Sustainable Human Resource Management to International Trade Governance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marler, J.H.; Boudreau, J.W. An evidence-based review of HR Analytics. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 28, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarouk, T.; Brewster, C. Conceptualising the future of HRM and technology research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 2652–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijerink, J.; Boons, M.; Keegan, A.; Marler, J. Algorithmic human resource management: Synthesizing developments and cross-disciplinary insights on digital HRM. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 2545–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, K.C.; Valentine, M.A.; Christin, A. Algorithms at work: The new contested terrain of control. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 366–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, I.; Wildhaber, I.; Adams-Prassl, J. Big Data in the workplace: Privacy Due Diligence as a human rights-based approach to employee privacy protection. Big Data Soc. 2021, 8, 20539517211013051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, D. How do employees form initial trust in artificial intelligence: Hard to explain but leaders help. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2024, 62, e12402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Hong, A.; Li, Y. Assessing the Role of HRM and HRD in Enhancing Sustainable Job Performance and Innovative Work Behaviors through Digital Transformation in ICT Companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Dunford, B.B.; Snell, S.A. Human resources and the resource based view of the firm. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S. Green Human Resource Management—A Synthesis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Qadeer, N.; Zámečník, R.; Javed, M.; Nawal, A. Towards a greener tomorrow: Investigating the nexus of GHRM, technology innovation, and employee green behavior in driving sustainable performance. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2442095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimo, I.D.; Sulistyaningsih, E. Greening the workforce: A systematic literature review of determinants in green HRM. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2429793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Nawaz, M.R.; Ishaq, M.I.; Khan, M.M.; Ashraf, H.A. Social exchange theory: Systematic review and future directions. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1015921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieserling, A. Blau (1964): Exchange and Power in Social Life. In Schlüsselwerke der Netzwerkforschung; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y. Enhancing Pro-Environmental Behavior Through Green HRM: Mediating Roles of Green Mindfulness and Knowledge Sharing for Sustainable Outcomes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Sanchez-Famoso, V.; Valéau, P.; Ren, S.; Mejia-Morelos, J.H. Green HRM through social exchange revisited: When negotiated exchanges shape cooperation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 3277–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirno, R.R.; Islam, N.; Happy, K. Green HRM and ecofriendly behavior of employees: Relevance of proecological climate and environmental knowledge. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cruz, J.; Rincon-Roldan, F.; Pasamar, S. When the stars align: The effect of institutional pressures on sustainable human resource management through organizational engagement. Eur. Manag. J. 2025, 43, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galleli, B.; Amaral, L. Bridging Institutional Theory and Social and Environmental Efforts in Management: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.C.; Cardy, R.L.; Huang, L.S.R. Institutional theory and HRM: A new look. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 316–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wang, Z. The Influence of Institutional Pressures on Environmental, Social, and Governance Responsibility Fulfillment: Insights from Chinese Listed Firms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Pak, A.; Roh, T. The interplay of institutional pressures, digitalization capability, environmental, social, and governance strategy, and triple bottom line performance: A moderated mediation model. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 5247–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, F.L. From Strategic HRM to Sustainable HRM? Exploring a Common Good Approach Through a Critical Reflection on Existing Literature. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeazzo, A.; Miandar, T.; Carraro, M. SDGs in corporate responsibility reporting: A longitudinal investigation of institutional determinants and financial performance. J. Manag. Gov. 2024, 28, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zihan, W.; Makhbul, Z.K.M.; Alam, S.S. Green Human Resource Management in Practice: Assessing the Impact of Readiness and Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Change. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Gupta, P.; Alghafes, R.; Broccardo, L. How Green Human Resource Management Boost Resilience. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 7048–7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Babu, V.; Murugesan, V.P. Human resource analytics revisited: A systematic literature review of its adoption, global acceptance and implementation. Benchmark. Int. J. 2024, 31, 2360–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Dong, Z.; Kularatne, I.; Rashid, M.S. Exploring approaches to overcome challenges in adopting human resource analytics through stakeholder engagement. Manag. Rev. Q. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnis, D.J. A Framework for Conceptual Contributions in Marketing. SSRN Electron. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, J.P.; Durand, R. Moving Forward: Developing Theoretical Contributions in Management Studies. J. Manag. Stud. 2014, 51, 995–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Valéau, P.; Renwick, D.W. Leveraging green human resource practices to achieve environmental sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashdi, D.R.; Birman, N.A. 5Cs for 5Ps: Achieving sustainable development goals through transforming human resource management. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 522, 146293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christina, J.L.; Alamelu, R.; Nigama, K. Synthesizing the impact of sustainable human resource management on corporate sustainability through multi method evidence. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, D.; Tian, L.; Qiu, W. The Study on the Influence of Green Inclusive Leadership on Employee Green Behaviour. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 5292184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindeeba, D.S.; Tukamushaba, E.K.; Bakashaba, R.; Atuhaire, S. Green human resources management and green innovation: A meta-analytic review of strategic human resources levers for environmental sustainability. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P. Green human resource practices for individual environmental performance: A meta-review. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2025, 42, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeudoka, B.C.; Igwe, C.O. Human Resource Management and Green Marketing. In Regulatory Frameworks and Digital Compliance in Green Marketing; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 209–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, S.S.; Edgar, D. Nurturing green behaviour: Exploring managerial competencies for effective green human resource management in hotels. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2025, 9, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Valéau, P.; Azeem, M.U. Configurations of green human resources practices for environmental sustainability. Rev. Gest. Ressour. Hum. 2024, 134, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, K.M.; Meijerink, J.; Keegan, A. Human Resource Management and the Gig Economy: Challenges and Opportunities at the Intersection between Organizational HR Decision-Makers and Digital Labor Platforms. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistiawan, J.; Herachwati, N.; Khansa, E.J.R. Barriers in adopting green human resource management under uncertainty: The case of Indonesia banking industry. J. Work.-Appl. Manag. 2024, 17, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.; Jaaron, A. The Impact of Green Human Resource Management Practices with Sustainable and Operational Performance: A Conceptual Model. In Innovation of Businesses, and Digitalization during COVID-19 Pandemic; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.; Rawshdeh, Z.; Allui, A.; AlMagoushi, N. The Effect of Perceived Socially Responsible HRM Practices on Employee’s Attitudes and the Moderator Role of Ethical Leadership in Saudi Arabia. In Navigating the Technological Tide: The Evolution and Challenges of Business Model Innovation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronnie, L. The challenge of toxic leadership in realising Sustainable Development Goals: A scoping review. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 22, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racelis, A. Ethical Leadership, Sustainable Governance, and the Prevention of Fraud. In Corporate Governance, Organizational Ethics, and Prevention Strategies Against Financial Crime; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M. Ethical leadership practices in managing organizational change: A qualitative study in Bangladesh. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, O.S.; Huertas-Valdivia, I.; Üzüm, B.; Contreras-Gordo, I. Responsible leadership and job embeddedness in hospitality: The role of managers’ light-triad personality and employees’ prosocial identity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 131, 104351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannor, F.O.; Baysah, J.O. Ethical Leadership Challenges in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: An In-depth Analysis. Pan-Afr. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2025, 6, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.H.; Khatibi, A.; Talib, Z.M.; George, R.A. Ethical leadership in environmental, social and governance (ESG) adoption for Malaysian micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2025, 41, 657–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qawasmeh, E.; Qawasmeh, F. Examining the Hybrid Digitalization of HRM in Jordanian Banks: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2024, 21, 2502–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Khan, M.H. Framing algorithmic management: Constructed antagonism on HR technology websites. New Technol. Work Employ. 2025, 40, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marabelli, M.; Lirio, P. AI and the metaverse in the workplace: DEI opportunities and challenges. Pers. Rev. 2025, 54, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, H.; Khatibi Bardsiri, A.; Bardsiri, V.K. Machine Learning Approaches for Predicting Employee Turnover: A Systematic Review. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, U.; Subramanian, P.; Srivastava, S.; Dwivedi, A. A study of Artificial Intelligence impacts on Human Resource Digitalization in Industry 4.0. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 7, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fu, N.; Chadwick, C.; Harney, B. Untangling human resource management and employee wellbeing relationships: Differentiating job resource HR practices from challenge demand HR practices. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2024, 34, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoir, M.; Sinha, V. Employee well-being human resource practices: A systematic literature review and directions for future research. Future Bus. J. 2024, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Dyrka, S.; Kokiel, A.; Urbańczyk, E. Sustainable HR and Employee Psychological Well-Being in Shaping the Performance of a Business. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karia, N.; Davadas Michael, R.C. Environmental Practices That Have Positive Impacts on Social Performance: An Empirical Study of Malaysian Firms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, B.S.; Priya, M.R.S.R. Human Resource Frontiers: Pioneering Humane Innovations for Fair Treatment of Workers in the Gig Economy. In Humanistic Management in the Gig Economy: Dignity, Fairness and Care; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C. Conclusion: Future of work and employee wellbeing. In Work-Life Balance, Employee Health and Wellbeing; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger Ploszaj, H.H.; Rocha Fernandes, B.H.; Camou Viacava, J.J.; Nassar Cardoso, A. Understanding the associations between ‘work from home’, job satisfaction, work-life balance, stress, and gender in an organizational context of remote work. Discov. Psychol. 2025, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, J.; Eslami, A. Hypothesized the relationship between work–family boundaries, work–life balance, workload, and employees’ well-being: Moderated mediation analysis. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2025, 44, 852–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menshikova, M.; Bonacci, I.; Scarozza, D.; Zifaro, M. The employee satisfaction with the new normal ways of working: A cluster analysis. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2025, 19, 863–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Arora, R.G. Examining the Influence of Green Human Resource Practices on Organisational Citizenship Behaviour for Environment in Indian Banking: Mediating role of green crafting through JD-R theory perspectives. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Kaur, H.; Rupčić, N.; Sanjeev, R. Aligning green HRM practices with green organisational citizenship behaviour to achieve organisational outcomes. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S. Promoting employees’ retention and functional presenteeism through well-being oriented human resource management practices: The mediating role of work meaningfulness. Evid. -Based HRM A Glob. Forum Empir. Scholarsh. 2025, 13, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annosi, M.C.; van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Karamanavi, D.; de Gennaro, D. Mutual gains through sustainable employability investments: Integrating HRM practices for organisational competitiveness. Pers. Rev. 2025, 54, 1048–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gašić, D.; Berber, N.; Slavić, A.; Jelača, M.S.; Marić, S.; Bjekić, R.; Aleksić, M. The Key Role of Employee Commitment in the Relationship Between Flexible Work Arrangements and Employee Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeksha; Mukherji, R.K.; Sharma, R. Employee Engagement in CSR: The Role of Green HRM in Building a Sustainable Culture. In Developments in Corporate Governance; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvnjak, B.; Kohont, A. The Role of Sustainable HRM in Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypniewska, B.; Baran, M.; Kłos, M. Work engagement and employee satisfaction in the practice of sustainable human resource management—Based on the study of Polish employees. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 1069–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.W.; Kok, S.K.; McClelland, R. The impact of green training on employee turnover intention and customer satisfaction: An integrated perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 3006–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasnaki, M. Exploring ethical leadership and green human resource management for social sustainable performance improvement: Evidence from the Greek maritime industry. Ind. Commer. Train. 2024, 56, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakira, E.; Shereni, N.C. Fostering environmental performance through green human resource management practices in hotels: The moderating role of green inclusive leadership. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2025, 24, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Kaur, H.; Bhat, D.A.R. Green Human Resource Management, Green Organisational Citizenship Behaviour and Organisational Sustainability in the Post-Pandemic Era: An Ability Motivation Opportunity and Resource Based View Perspective. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2025, 8, e70126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, N.A.A. The predictive power of technology leadership and green HRM toward green innovation, work engagement and environmental performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2025, 74, 2159–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housheya, N.; Atikbay, T. The Role of Green HRM in Promoting Green Innovation: Mediating Effects of Corporate Environmental Strategy and Green Work Climate, and the Moderating Role of Artificial Intelligence. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.W.; Rowan, B. Talking About Organizations Podcast. 2023. Available online: www.talkingaboutorganizations.com (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Sharif, S.; Malik, S.A. Does green HRM and intellectual capital strengthen psychological green climate, green behaviors and creativity? A step towards green textile manufacturing. J. Intellect. Cap. 2025, 26, 644–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwumah, K.; Sappor, P.; Sarpong, F.A. Navigating the Green Path: Strategies for Enhancing Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment Through Green HRM Practices. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 3045–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Piwowar-Sulej, K.; Agarwal, R.; Yaqub, M.Z. Sustainability-Oriented Leadership and Business Strategy: Examining the Roles of Procedural Environmental Justice and Job Embeddedness. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 2917–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakra, N.; Kashyap, V. Responsible leadership and organizational sustainability performance: Investigating the mediating role of sustainable HRM. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2025, 74, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Akhtar, M.W.; Zahoor, N.; Khan, M.A.S.; Adomako, S. Triggering employee green activism through green human resource management: The role of green organizational learning and responsible leadership. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1085–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čižiūnienė, K.; Voronavičiūtė, G.; Marinkovic, D.; Matijošius, J. Sustainable Human Resource Management in Emergencies: The Case of the Lithuanian Logistics Sector. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmić, A.; Ćosić, M. Digital human resource management influence on the organizational resilience. Organ. Manag. J. 2025, 22, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, H.; Moreira, S.B. Human Capital at the Crossroads of Sustainability: Integrating Key Trends in HRM with the Sustainable Development Goals. In Integrated Science to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, D.G.; Wood, G.; Szamosi, L.T. Human Resource Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Abidin, R.Z.U.; Qammar, R.; Qadri, S.U.; Khan, M.K.; Ma, Z.; Qadri, S.; Ahmed, H.; ud din Khan, H.S.; Mahmood, S. Pro-environmental behavior, green HRM practices, and green psychological climate: Examining the underlying mechanism in Pakistan. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1067531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, Z.; Hussain, S. Green Transformational Leadership: Bridging the gap between Green HRM Practices and Environmental Performance through Green Psychological Climate. Sustain. Futures 2023, 6, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, R.; Singh, N.; Nagpal, M. Integrating Sustainable HRM With SDGs. In Implementing ESG Frameworks Through Capacity Building and Skill Development; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Human Capital to Implement Corporate Sustainability Business Strategies for Common Good. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Usman, M.; Shafique, I.; Ogbonnaya, C.; Roodbari, H. Can HR managers as ethical leaders cure the menace of precarious work? Important roles of sustainable HRM and HR manager political skill. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 35, 1824–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S.; Kaur, A.; Renwick, D.W.S. Green Human Resource Management and Green Culture: An Integrative Sustainable Competing Values Framework and Future Research Directions. Organ Environ. 2024, 37, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, K.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. When does CSR-facilitation human resource management motivate employee job engagement? The contextual effect of job insecurity. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2024, 34, 1063–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakra, N.; Kashyap, V. Investigating the link between socially-responsible HRM and organizational sustainability performance—An HRD perspective. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2024, 48, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekhorst, J.A.; Frawley, S. The pragmatic side of workplace heroics: A self-interest perspective on responding to mistreatment in work teams. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 3169–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theory | Key Constructs Explained | Level of Analysis | Proposed Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource-Based View (RBV) | Green HRM Practices; Human Capital Capabilities | Organizational | Sustainable value creation through rare, valuable, and inimitable resources |

| Social Exchange Theory (SET) | Ethical Leadership; Employee Engagement; Well-being | Individual/Group | Reciprocal relationships fostering trust, engagement, and pro-environmental behavior |

| Institutional Theory | Digital Resilience; Accountability and Legitimacy | Organizational/Societal | Compliance with external norms, enhancing transparency and sustainability legitimacy |

| Construct | Definition | Boundary | Illustrative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green HRM Practices | HR practices aligned with environmental objectives to reduce ecological footprints. | HR-focused practices with direct environmental impact, not general CSR. | Green recruitment, eco-training, green rewards. |

| Ethical and Responsible Leadership | Leadership behaviors grounded in fairness, justice, and accountability in HR decisions. | Focused on HR-related leadership ethics, not corporate-level CSR. | Role modeling, fair decision-making, accountability mechanisms. |

| Digital Resilience in HR | Capacity of HR to adopt digital tools adaptively while ensuring fairness and transparency. | Restricted to HR tech, not general organizational digitalisation. | HR analytics, AI recruitment, automated appraisals. |

| Employee Well-Being and Social Sustainability | Holistic employee outcomes including health, work–life balance, and DEI. | Focus on employee-centered outcomes, not only organizational benefits. | Mental health programs, flexible work, DEI policies. |

| Sustainability Outcomes | HRM-driven contributions to SDGs, ESG reporting, and long-term sustainability. | Limited to HRM-related impacts, not entire corporate sustainability. | HR-linked ESG metrics, workforce diversity in reports, carbon footprint reduction. |

| No | Proposition | Description/Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | Green HRM practices positively influence employee well-being. | Green-oriented HR policies enhance employee engagement, satisfaction, and sustainable behaviors. |

| P2 | Ethical leadership positively moderates the relationship between Green HRM and employee well-being. | Ethical and responsible leadership strengthens the link between HRM practices and employee outcomes through fairness and moral guidance. |

| P3 | Digital resilience in HR systems positively affects organizational sustainability outcomes. | The adaptive use of digital tools supports transparency, accountability, and environmental performance. |

| P4 | Employee well-being mediates the relationship between Green HRM and sustainability outcomes. | Well-being acts as the psychological mechanism translating HR practices into sustainable organizational performance. |

| P5 | Ethical leadership positively moderates the relationship between digital resilience and institutional legitimacy. | Organizations with strong ethical leadership convert digital resilience into credible, legitimate ESG and SDG outcomes by ensuring transparency and fairness. |

| P6 | Employee well-being mediates the relationship between sustainable HRM practices and sustainability outcomes. | Employee well-being serves as the key mechanism through which Sustainable HRM drives organizational and societal sustainability, without conditional or multi-path effects. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurniawan, B.; Marnis; Samsir; Jahrizal. A Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Human Resource Management: Integrating Green Practices, Ethical Leadership, and Digital Resilience to Advance the SDGs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219904

Kurniawan B, Marnis, Samsir, Jahrizal. A Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Human Resource Management: Integrating Green Practices, Ethical Leadership, and Digital Resilience to Advance the SDGs. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219904

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurniawan, Buyung, Marnis, Samsir, and Jahrizal. 2025. "A Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Human Resource Management: Integrating Green Practices, Ethical Leadership, and Digital Resilience to Advance the SDGs" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219904

APA StyleKurniawan, B., Marnis, Samsir, & Jahrizal. (2025). A Conceptual Framework for Sustainable Human Resource Management: Integrating Green Practices, Ethical Leadership, and Digital Resilience to Advance the SDGs. Sustainability, 17(21), 9904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219904