COVID-19 and the Merit-Order Effect of Wind Energy: The Case of Nord Pool Electricity Markets †

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Government Measures to Handle the Pandemic Situation

1.2. Effect on Local Electricity Price Due to Predicaments

1.3. Effect of Wind Energy Production (WEP) on Local Electricity Price (LEP) and Government Measures

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Descriptive Statistics

2.3. Preliminary Tests

2.3.1. Cross-Sectional Dependence Test for Panels

2.3.2. Panel Unit Root Tests

2.3.3. Panel ARDL Cointegration Test

2.4. Econometric Methodology

- Short-run price fluctuations: Since the PMG estimator permits heterogeneous short-run adjustments across panel units, it accounts for country-specific variations in price dynamics due to wind intermittency. This is particularly relevant for Denmark, where sudden drops in wind energy generation may lead to increased reliance on backup power sources, thereby increasing price volatility.

- Long-run equilibrium effects: The model constrains the long-run relationship to be homogenous across countries, ensuring that the general trend of price reduction due to wind energy penetration is accurately captured while allowing for short-term deviations.

- Asymmetry in price responses: If price effects from wind fluctuations are asymmetric (e.g., low wind speeds leading to sharper price spikes than the price reductions seen during high wind speeds), the inclusion of error correction dynamics in ARDL estimation helps capture these asymmetric adjustments. (To further reinforce the robustness of our findings, additional analyses could involve nonlinear specifications (e.g., NARDL) to explicitly model the asymmetric effects of wind variability on price volatility. This would provide deeper insights into how Denmark’s electricity prices react differently to increases and decreases in wind generation [59]. This should be left to another independent study.)

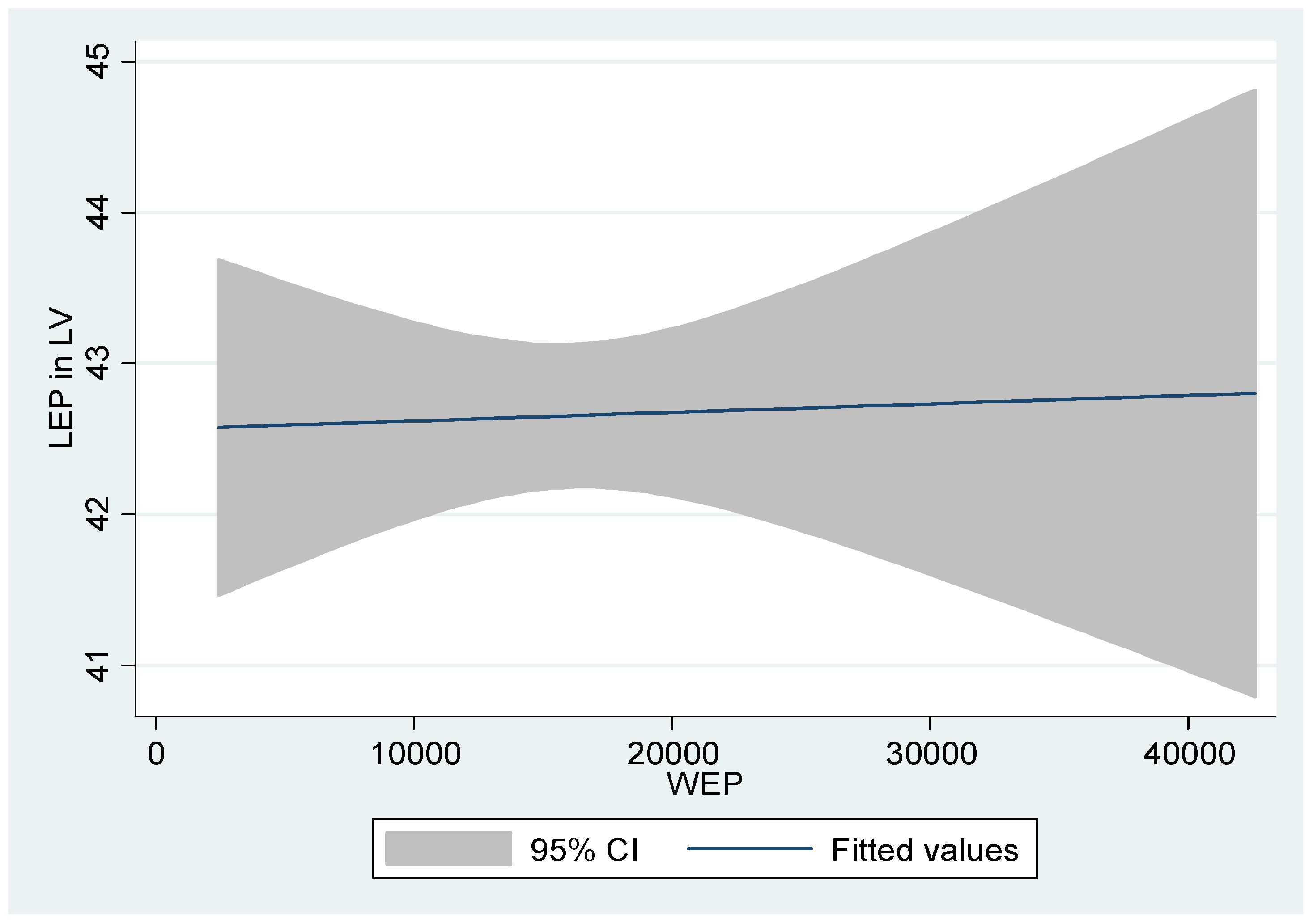

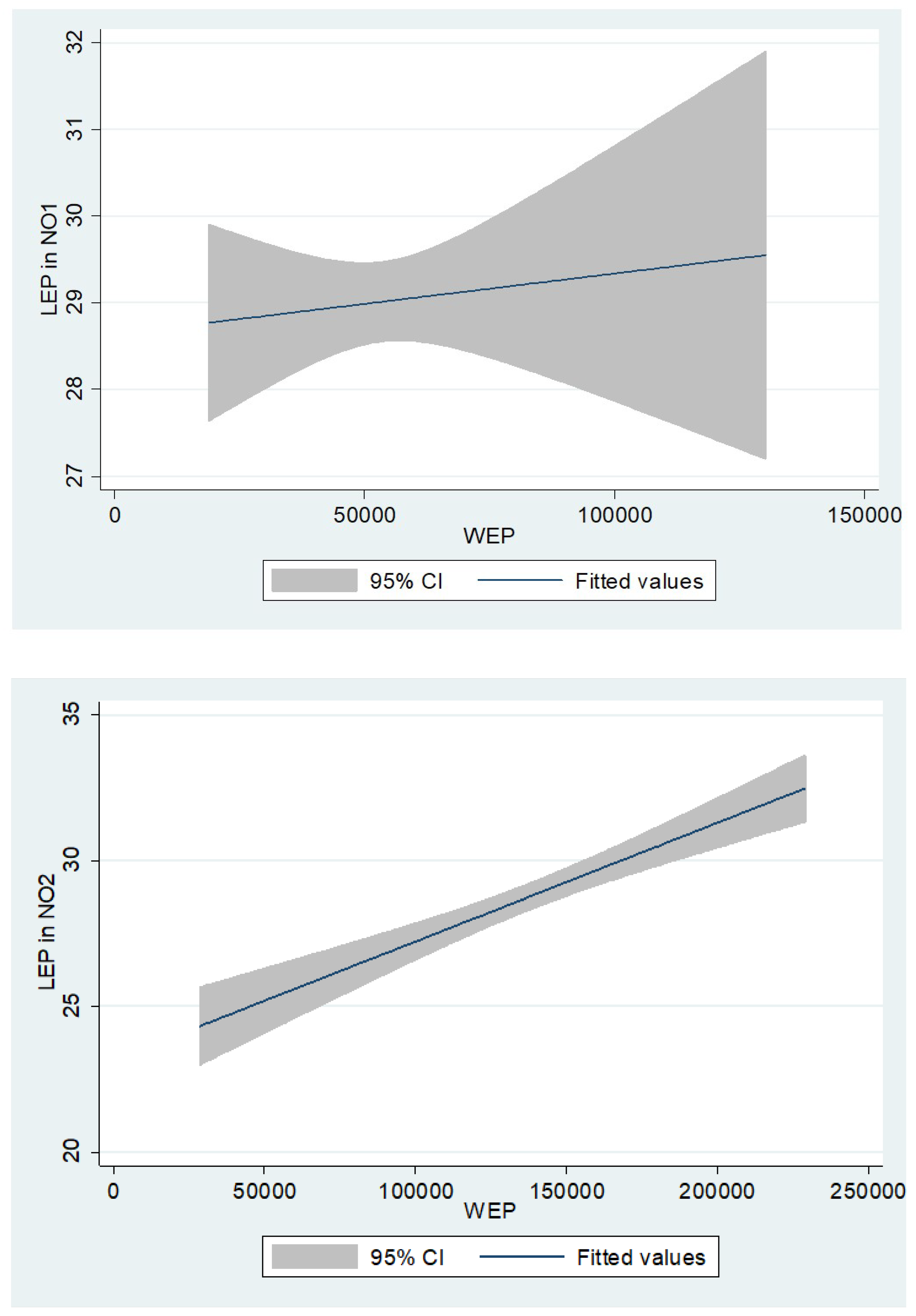

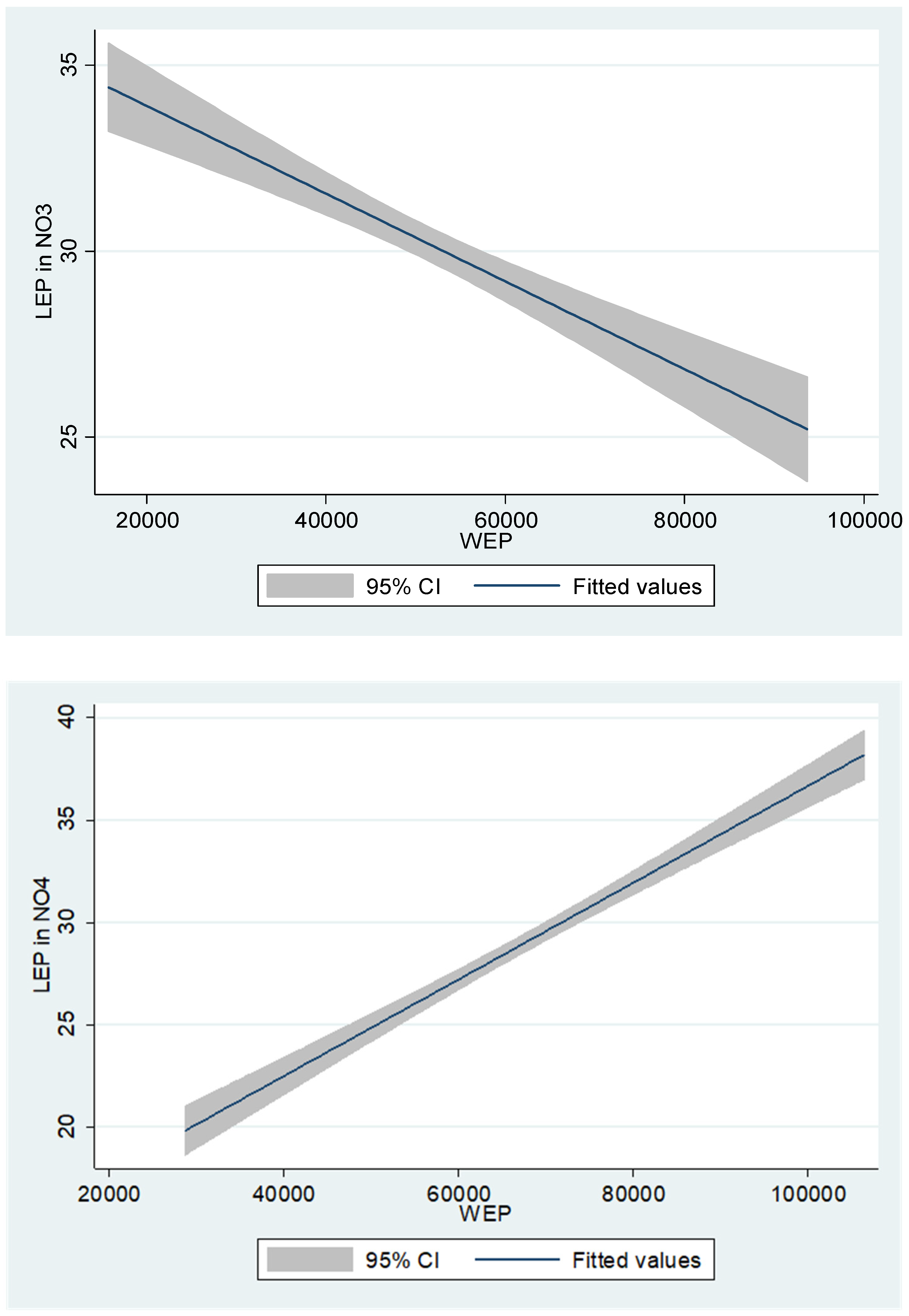

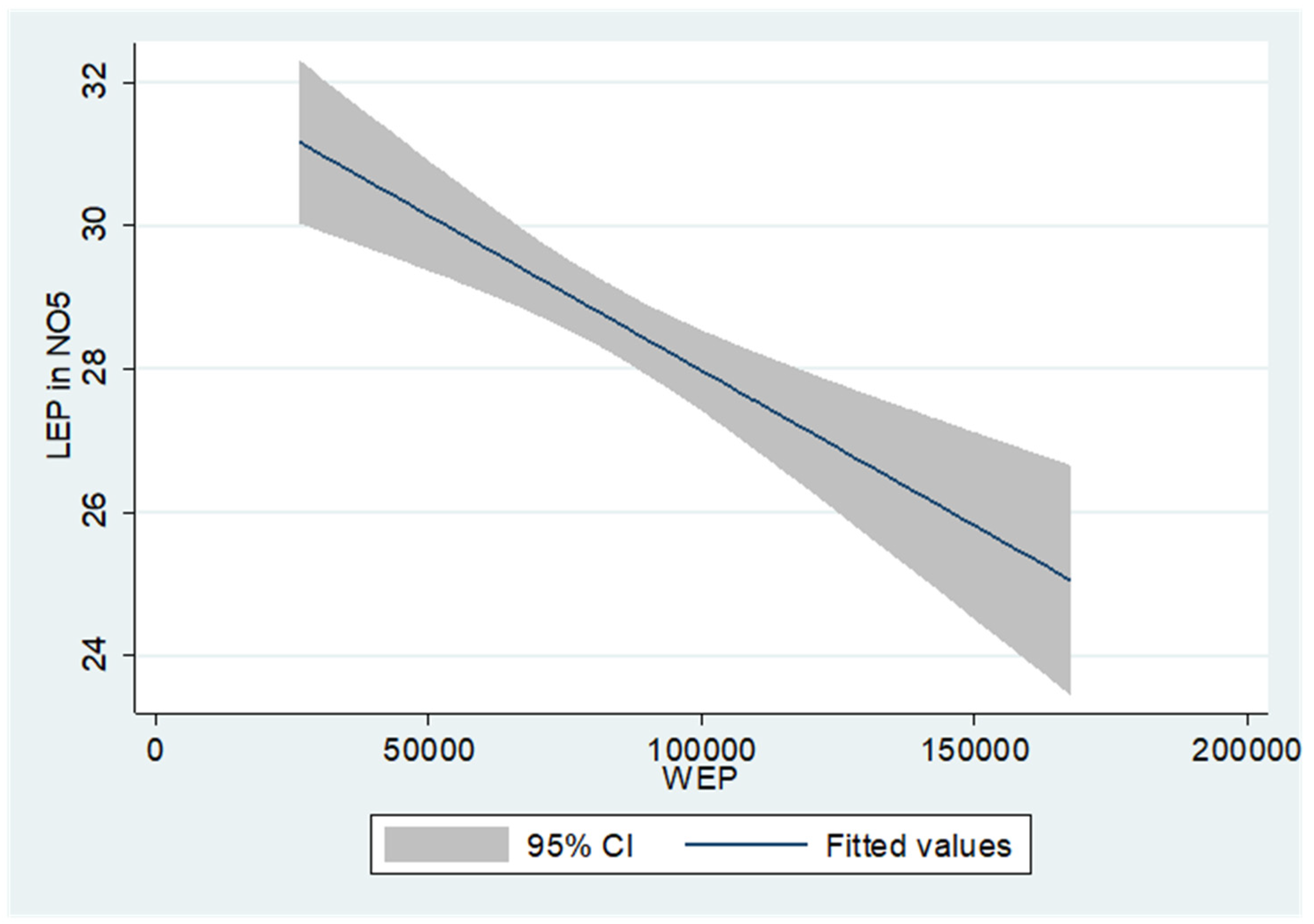

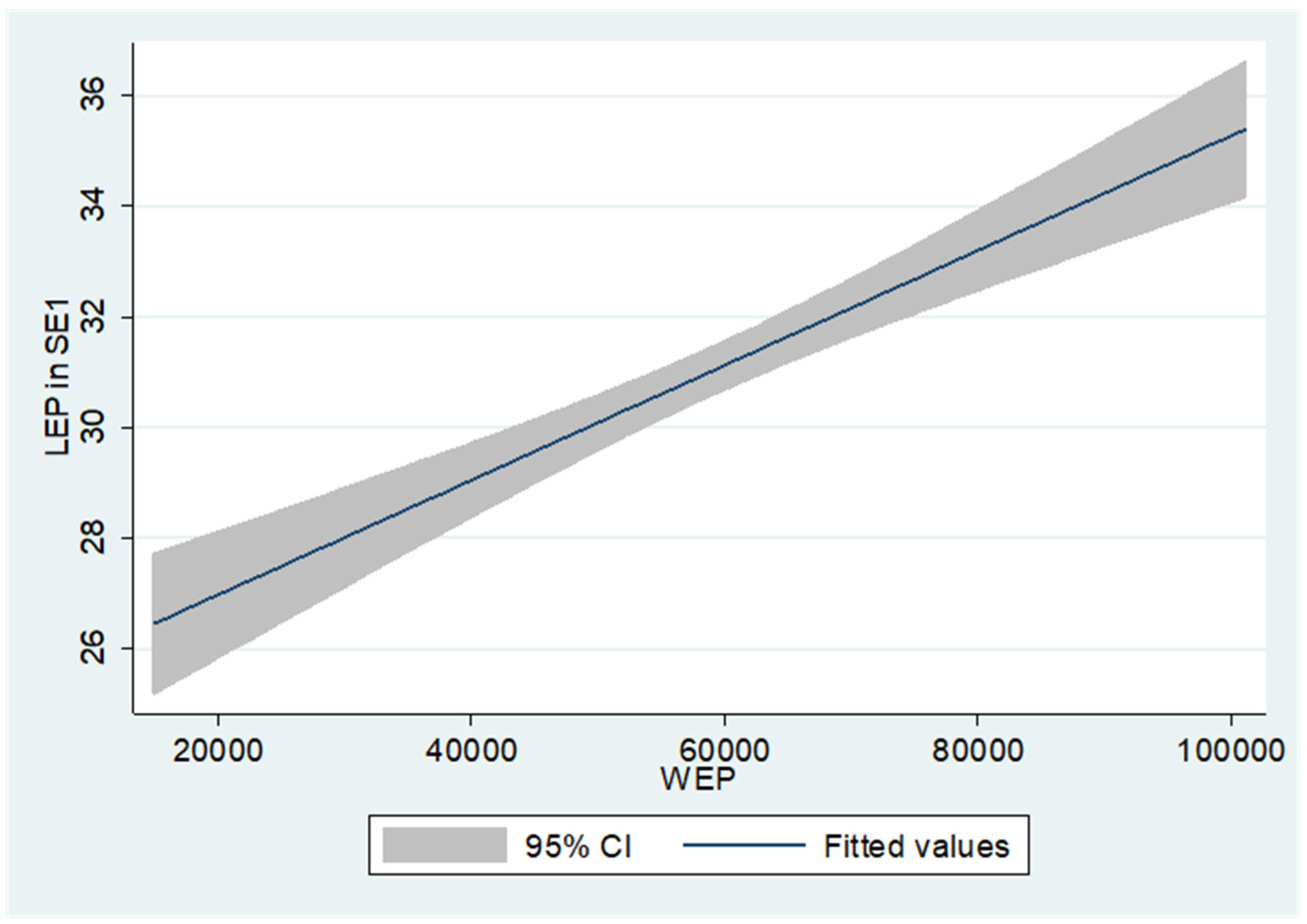

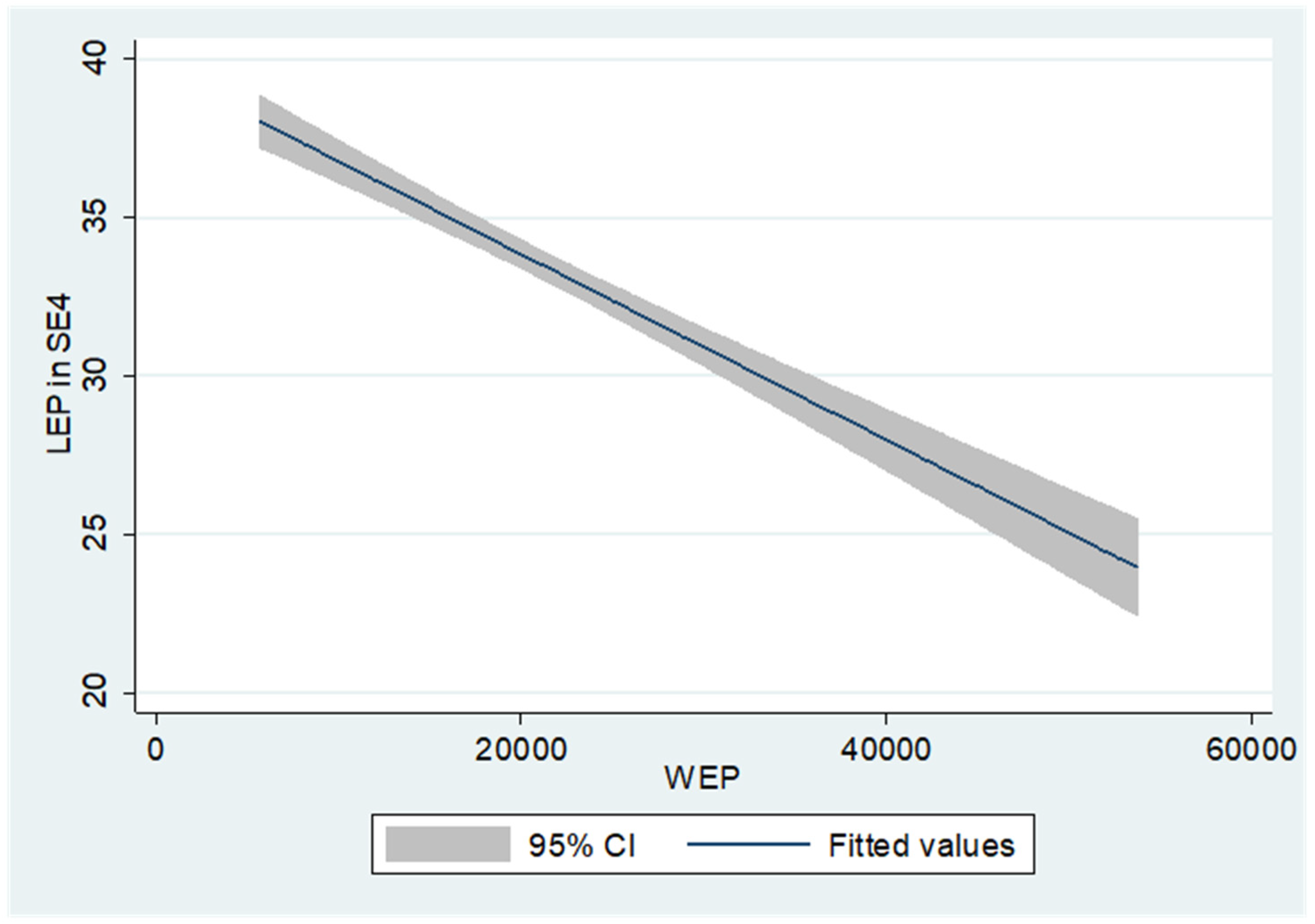

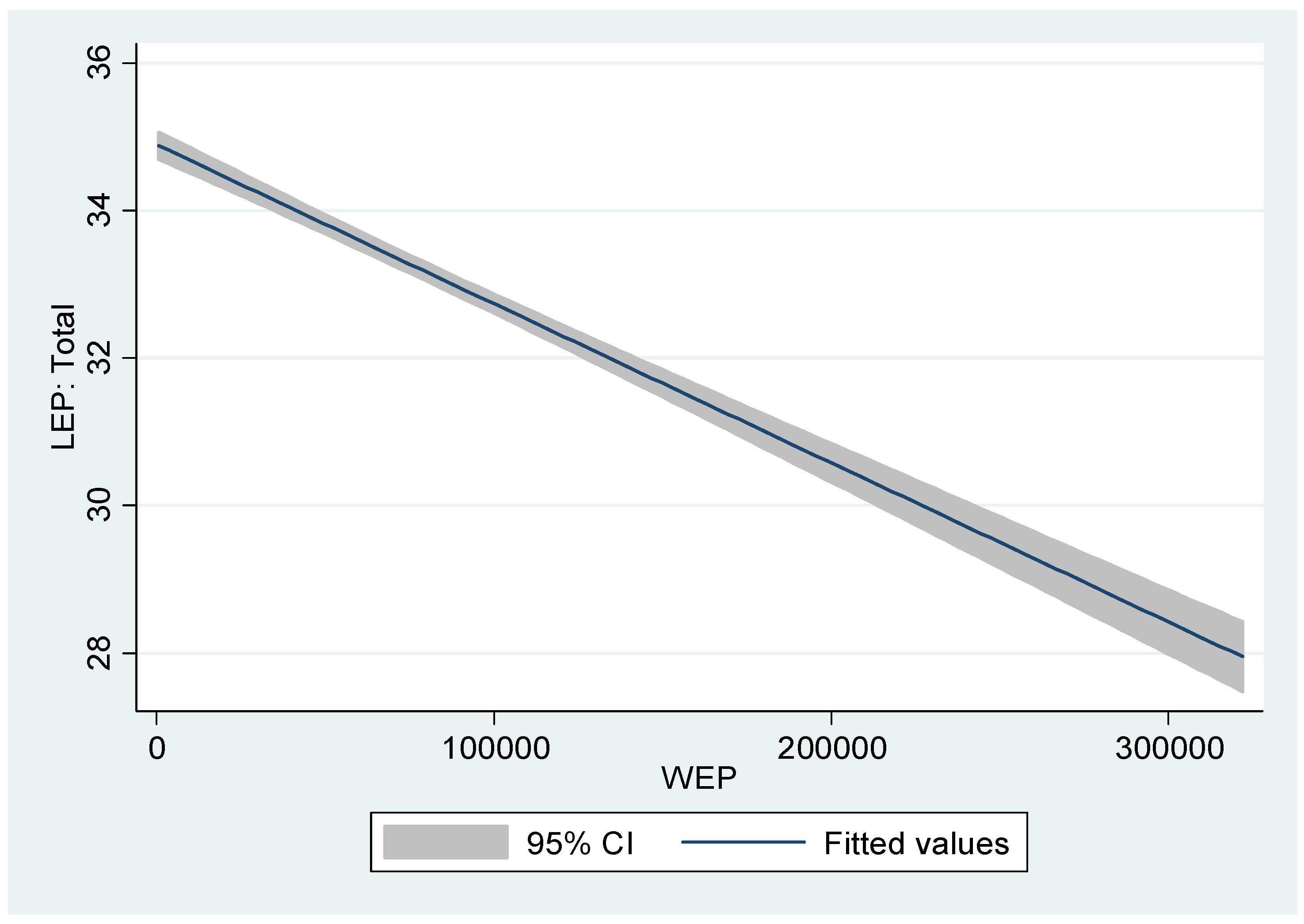

3. Results

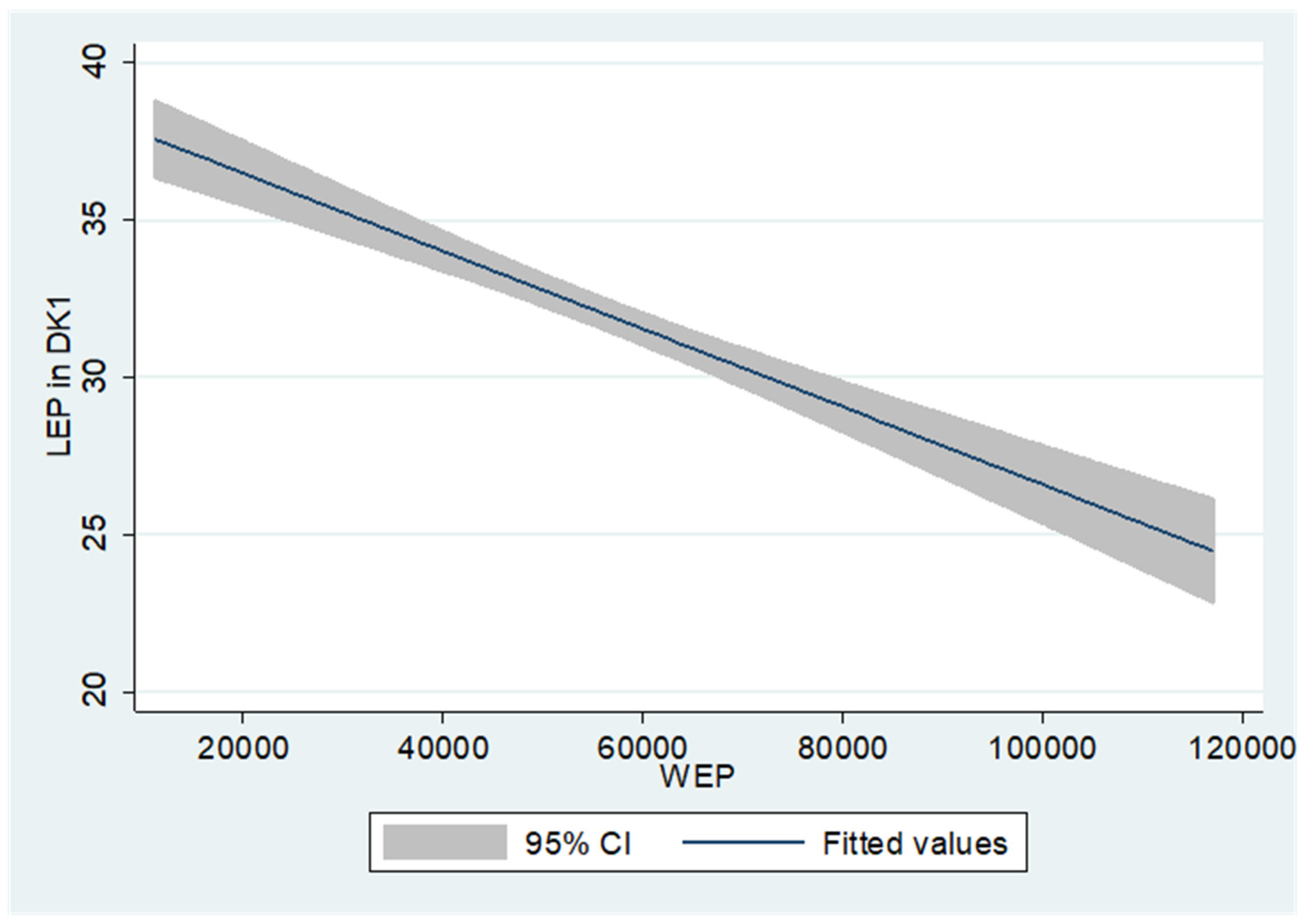

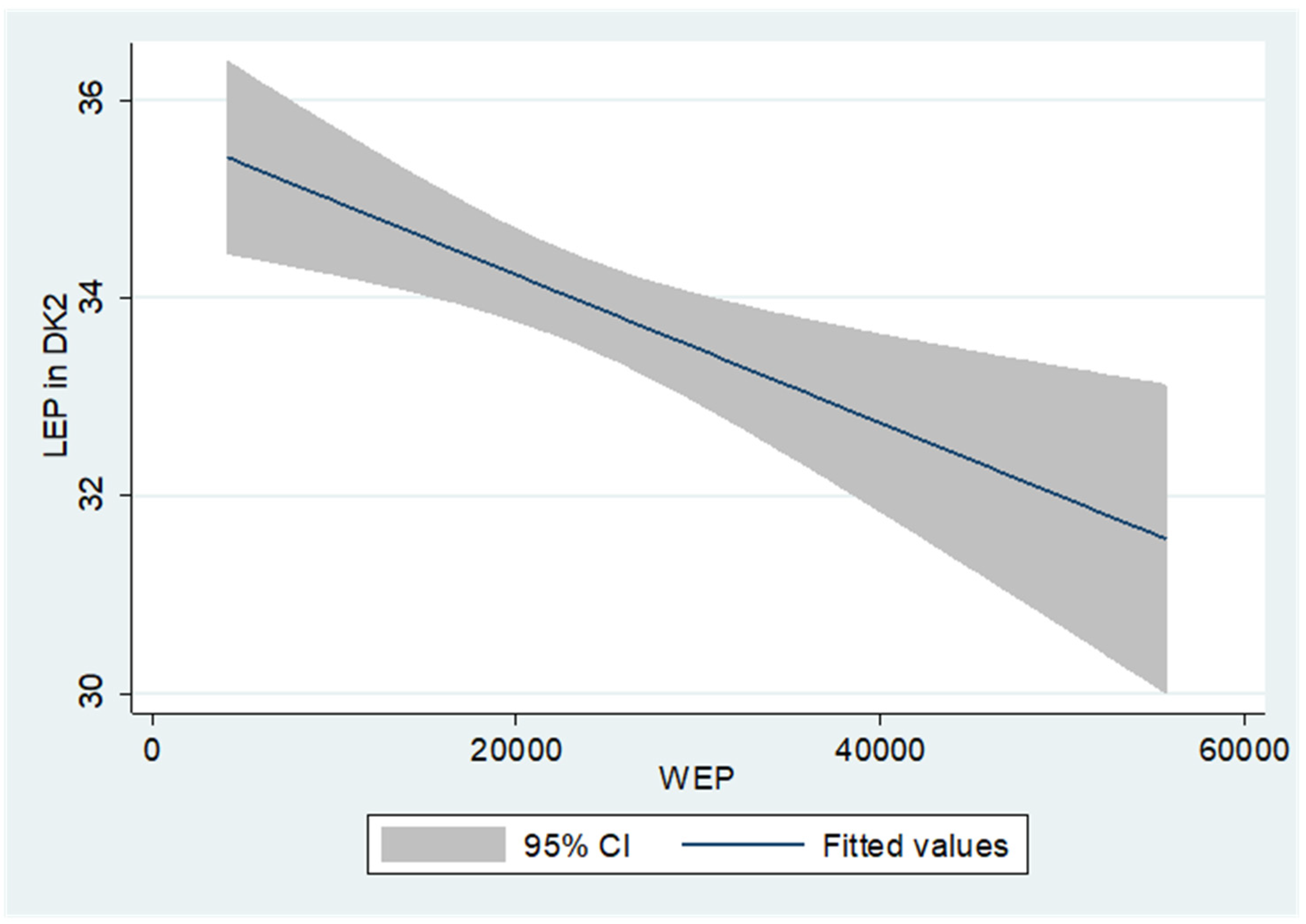

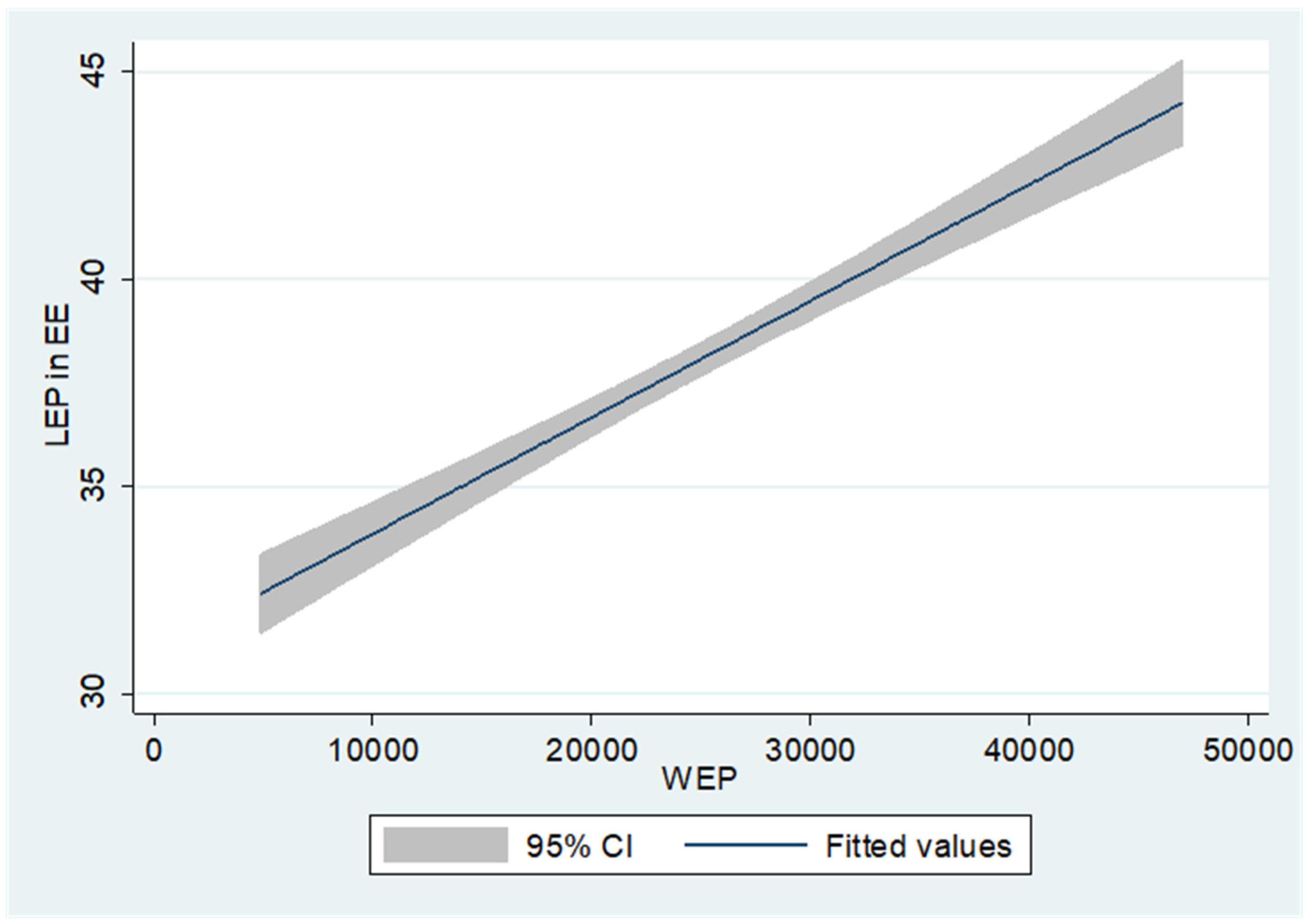

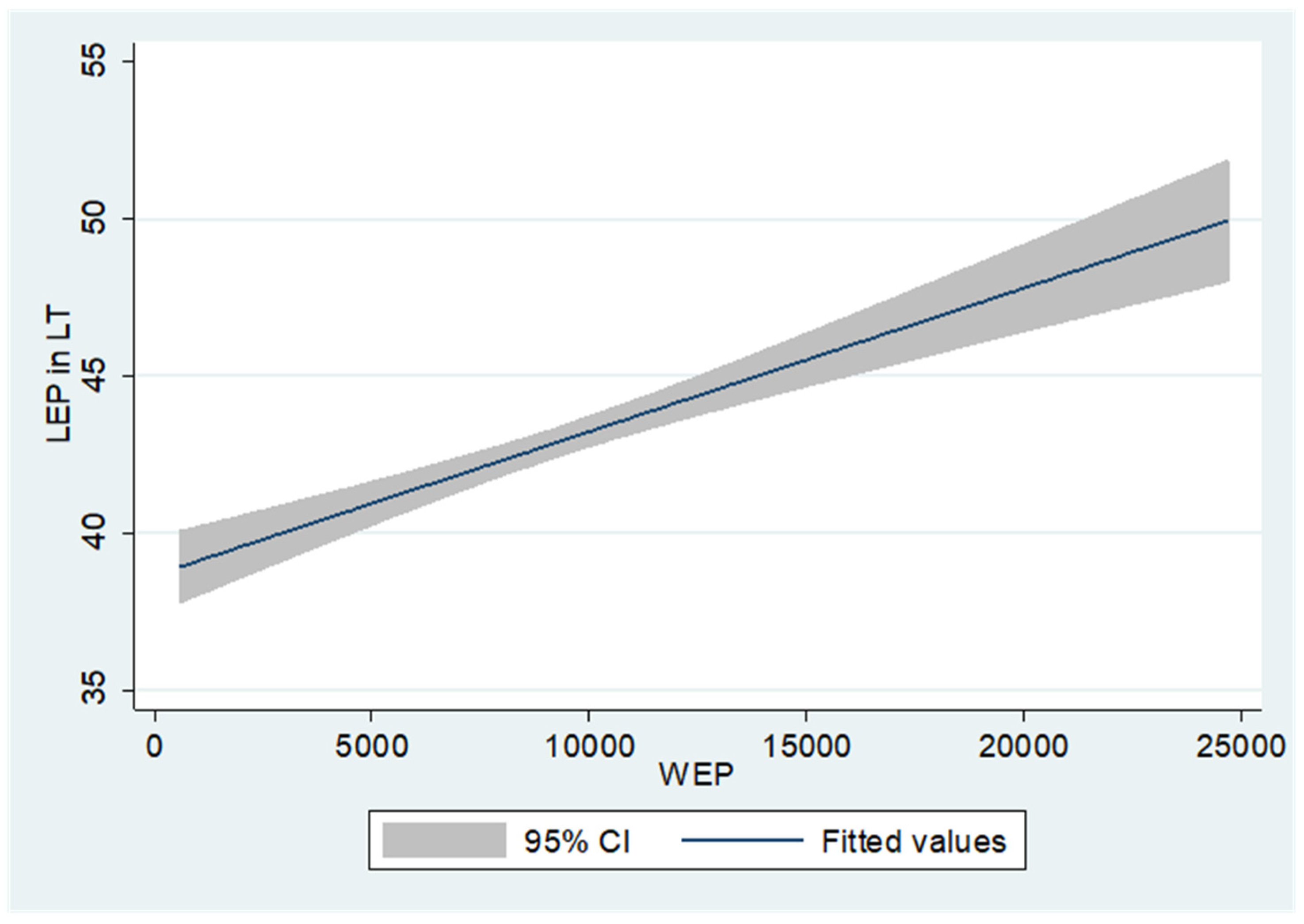

3.1. Long-Term Results

3.2. Short-Term Results

3.3. Comparison with Previous Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADF | Augmented Dickey–Fuller |

| ARDL | Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| CCC-19 | COVID-19 Confirmed Cases |

| CCV-19 | COVID-19 Death Cases |

| CHI | Containment Health Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CIPS | Cross-sectional augmented of Im, Pesaran, and Shin |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Infectious Disease |

| DFE | Dynamic Fixed Effects |

| DK | Denmark |

| EE | Estonia |

| EEA | European Economic Area Agreement |

| EPI | Economic Policy Index |

| EU | European Union |

| EU ETS | European Union Emissions Trading System |

| FI | Finland |

| GSI | Government Stringency Index |

| GWh | Gigawatt-hour |

| IPS | Im, Pesaran, and Shin |

| LEP | Local Electricity Price |

| LM | Lagrange Multiplier |

| LT | Latvia |

| LV | Latvia |

| MG | Mean Group |

| MWh | Megawatt-hour |

| NW | Norway |

| PMG | Pooled Mean Group |

| PPA | Purchase Power Agreements |

| RALS | Residual Augmented Least Squares |

| SE | Sweden |

| TCIPS | Truncated Cross-sectional augmented of Im, Pesaran, and Shin |

| US | United States |

| WEP | Wind Energy Production |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Variables | Notation | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Local Electricity Price | LEP | Local Electricity Price in Euros. |

| Wind Energy Production | WEP | Wind Energy Production in MWh. |

| Government Stringency Index | GSI | Higher numbers on a scale of 0 to 100 denote more stringent COVID-19-related government regulations and limitations. |

| Containment Health Index | CHI | Better virus containment is indicated by higher values on the index, which normally spans from 0 to 100. |

| Economics Policy Index | EPI | A more accommodating economic policy posture is indicated by higher values, while a more restrictive stance is indicated by lower values. The index normally goes from 0 to 100. |

| COVID-19 Confirmed Death | CCD-19 | Total number of COVID-19-related deaths. |

| COVID-19 Confirmed Cases | CCC-19 | Total number of COVID-19-related cases. |

| Statistics | LEP | WEP | GSI | CHI | EPI | CCC-19 | CCD-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 20.33955 | 75,944.61 | 43.50066 | 40.00940 | 43.26275 | 31,203.96 | 1213.866 |

| Median | 17.73500 | 61,512.00 | 50.00000 | 47.62000 | 37.50000 | 8912.500 | 255.0000 |

| Maximum | 107.4200 | 307,951.0 | 87.04000 | 76.67000 | 100.0000 | 437,379.0 | 8727.000 |

| Minimum | −14.37000 | 2431.000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| Std. Dev. | 15.20087 | 63,686.25 | 23.19269 | 18.86467 | 27.83101 | 61426.05 | 2165.384 |

| Skewness | 0.952031 | 1.036769 | −0.684225 | −1.063694 | −0.014762 | 3.757571 | 1.801314 |

| Kurtosis | 4.155320 | 3.399146 | 2.443343 | 2.910775 | 2.348256 | 19.45588 | 4.638427 |

| Jarque–Bera | 1134.650 | 1019.967 | 499.2516 | 1037.094 | 97.36563 | 74,863.76 | 3582.996 |

| Probability | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| Observations | 5490 | 5490 | 5490 | 5490 | 5490 | 5490 | 5490 |

| LEP | WEP | CCC-19 | CCD-19 | GSI | CHI | EPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEP | 1.000000 | ||||||

| ----- | |||||||

| WEP | −0.231025 | 1.000000 | |||||

| (0.0000) | ----- | ||||||

| CCC-19 | 0.089923 | 0.146751 | 1.000000 | ||||

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | ----- | |||||

| CCD-19 | 0.039580 | 0.167449 | 0.807515 | 1.000000 | |||

| (0.0034) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | ----- | ||||

| GSI | −0.089099 | −0.047411 | 0.337575 | 0.376672 | 1.000000 | ||

| (0.0000) | (0.0004) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | ----- | |||

| CHI | 0.003809 | −0.085018 | 0.360282 | 0.388556 | 0.958722 | 1.000000 | |

| (0.7778) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | ----- | ||

| EPI | 0.288253 | −0.213782 | 0.212505 | 0.215859 | 0.634595 | 0.729088 | 1.000000 |

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | ----- |

Appendix A.2

| Test | Breusch-Pagan LM | Pesaran Scaled LM | Bias-Corrected Scaled LM | Pesaran CD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Statistic | Prob. | Statistic | Prob. | Statistic | Prob. | Statistic | Prob. |

| LEP | 14,005.79 | 0.0000 | 959.2455 | 0.0000 | 959.2249 | 0.0000 | 102.7843 | 0.0000 |

| WEP | 5312.917 | 0.0000 | 359.3804 | 0.0000 | 359.3599 | 0.0000 | 53.56542 | 0.0000 |

| GSI | 31,684.81 | 0.0000 | 2179.214 | 0.0000 | 2179.193 | 0.0000 | 177.5544 | 0.0000 |

| CCC-19 | 36,387.38 | 0.0000 | 2503.722 | 0.0000 | 2503.701 | 0.0000 | 190.6909 | 0.0000 |

| CCD-19 | 31,350.07 | 0.0000 | 2156.115 | 0.0000 | 2156.094 | 0.0000 | 174.3654 | 0.0000 |

| CHI | 34,072.50 | 0.0000 | 2343.980 | 0.0000 | 2343.959 | 0.0000 | 184.4641 | 0.0000 |

| EPI | 28,041.83 | 0.0000 | 1927.824 | 0.0000 | 1927.804 | 0.0000 | 165.9556 | 0.0000 |

| Variables | None | |||

| CIPS | p-Value | Truncated CIPS | p-Value | |

| T-Stat | T-Stat | |||

| LEP | −3.88014 | <0.01 | −3.88014 | <0.01 |

| WEP | −3.51233 | <0.01 | −3.51233 | <0.01 |

| GSI | −2.21927 | <0.01 | −2.21927 | <0.01 |

| CCC-19 | −1.07349 | ≥0.1 | −1.78589 | <0.05 |

| CCD-19 | −0.35708 | ≥0.1 | −0.67443 | ≥0.1 |

| CHI | −1.86017 | <0.01 | −1.86017 | <0.01 |

| EPI | −3.27169 | <0.01 | −3.27169 | <0.01 |

| Variables | With constant | |||

| CIPS | p-value | Truncated CIPS | p-value | |

| T-stat | T-stat | |||

| LEP | −4.10308 | <0.01 | −4.10308 | <0.01 |

| WEP | −4.08823 | <0.01 | −4.07992 | <0.01 |

| GSI | −2.55766 | <0.01 | −2.55766 | <0.01 |

| CCC-19 | −1.35202 | ≥0.1 | −2.04964 | ≥0.1 |

| CCD-19 | −0.47934 | ≥0.1 | −0.89795 | ≥0.1 |

| CHI | −2.12315 | <0.01 | −2.121315 | <0.01 |

| EPI | −3.29349 | <0.01 | −3.29349 | <0.01 |

| Variables | With constant and trend | |||

| CIPS | p-value | Truncated CIPS | p-value | |

| T-stat | T-stat | |||

| LEP | −4.24799 | <0.01 | −4.29799 | <0.01 |

| WEP | −4.38077 | <0.01 | −4.31591 | <0.01 |

| GSI | −2.40792 | ≥0.1 | −2.40792 | ≥0.1 |

| CCC-19 | −2.32947 | ≥0.1 | −2.32947 | ≥0.1 |

| CCD-19 | 0.03405 | ≥0.1 | −3.41875 | <0.01 |

| CHI | −2.04407 | <0.01 | −2.04407 | <0.01 |

| EPI | −3.72087 | <0.01 | −3.72087 | <0.01 |

| Variables | None | |||

| CIPS | p-Value | Truncated CIPS | p-Value | |

| T-Stat | T-Stat | |||

| LEP | −10.97256 | <0.1 | −5.99797 | <0.1 |

| WEP | −12.44047 | <0.1 | −6.12 | <0.1 |

| GSI | −9.34911 | <0.1 | −6.12 | <0.1 |

| CCC-19 | −1.7889 | <0.1 | −0.13482 | <0.1 |

| CCD-19 | 0.65766 | ≥0.1 | −0.13482 | ≥0.1 |

| CHI | −11.48152 | <0.1 | −6.12 | <0.1 |

| EPI | −10.63739 | <0.1 | −6.12 | <0.1 |

| Variables | With constant | |||

| CIPS | p-value | Truncated CIPS | p-value | |

| T-stat | T-stat | |||

| LEP | −10.96015 | <0.1 | −6.0566 | <0.1 |

| WEP | −12.42641 | <0.1 | −6.19 | <0.1 |

| GSI | −9.38225 | <0.1 | −6.19 | <0.1 |

| CCC-19 | −2.06773 | ≥0.1 | −2.06773 | ≥0.1 |

| CCD-19 | 0.74254 | ≥0.1 | −0.71244 | ≥0.1 |

| CHI | −11.49814 | <0.1 | −6.19 | <0.1 |

| EPI | −10.63144 | <0.1 | −6.19 | <0.1 |

| Variables | With a constant and trend | |||

| CIPS | p-value | Truncated CIPS | p-value | |

| T-stat | T-stat | |||

| LEP | −11.10454 | <0.1 | −6.2913 | <0.1 |

| WEP | −12.42848 | <0.1 | −6.42 | <0.1 |

| GSI | −9.44568 | <0.1 | −6.42 | <0.1 |

| CCC-19 | −2.23269 | ≥0.1 | −2.23269 | ≥0.1 |

| CCD-19 | 0.28484 | ≥0.1 | −3.20967 | <0.1 |

| CHI | −11.58176 | <0.1 | −6.42 | <0.1 |

| EPI | −10.63195 | <0.1 | −6.42 | <0.1 |

| Model | None | With Constant | With a Constant and Trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | p-Value | Statistic | p-Value | Statistic | p-Value | ||

| WEP, GSI | Gt | −4.580 | 0.000 | −5.302 | 0.000 | −6.167 | 0.000 |

| Ga | −48.293 | 0.000 | −61.511 | 0.000 | −83.872 | 0.000 | |

| Pt | −19.123 | 0.000 | −22.113 | 0.000 | −25.773 | 0.000 | |

| Pa | −54.719 | 0.000 | −71.842 | 0.000 | −96.157 | 0.000 | |

| WEP, CHI | Gt | −4.643 | 0.000 | −5.165 | 0.000 | −6.304 | 0.000 |

| Ga | −50.856 | 0.000 | −60.805 | 0.000 | −85.142 | 0.000 | |

| Pt | −19.674 | 0.000 | −21.994 | 0.000 | −31.948 | 0.000 | |

| Pa | −57.933 | 0.000 | −71.502 | 0.000 | −111.278 | 0.000 | |

| WEP, EPI | Gt | −4.643 | 0.000 | −5.135 | 0.000 | −5.912 | 0.000 |

| Ga | −50.856 | 0.000 | −60.107 | 0.000 | −76.765 | 0.000 | |

| Pt | −19.674 | 0.000 | −22.041 | 0.000 | −30.493 | 0.000 | |

| Pa | −57.933 | 0.000 | −70.971 | 0.000 | −102.307 | 0.000 | |

| WEP, CCC-19 | Gt | −4.778 | 0.000 | −5.674 | 0.000 | −5.805 | 0.000 |

| Ga | −41.373 | 0.000 | −59.242 | 0.000 | −65.488 | 0.000 | |

| Pt | −19.023 | 0.000 | −22.802 | 0.000 | −23.687 | 0.000 | |

| Pa | −43.927 | 0.000 | −67.149 | 0.000 | −74.475 | 0.000 | |

| WEP, CCD-19 | Gt | −5.064 | 0.000 | −5.338 | 0.000 | −5.645 | 0.000 |

| Ga | −59.064 | 0.000 | −65.803 | 0.000 | −71.414 | 0.000 | |

| Pt | −20.905 | 0.000 | −21.933 | 0.000 | −22.590 | 0.000 | |

| Pa | −63.451 | 0.000 | −71.784 | 0.000 | −76.379 | 0.000 | |

Appendix A.3

| Dependent Variable: LEP | Independent Variables | Coefficient | Prob * | Impact of a 1% Increase | WEP Impact of Extra 1 GW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1—ARDL(2, 2, 2) | WEP | −5.94E−05 | 0.0114 ** | −0.006% | −0.06€ |

| GSI | −1.51E−01 | 0 *** | −15.124% | ||

| Model 2—ARDL(2, 2, 2) | WEP | −6.72E−05 | 0.0041 *** | −0.007% | −0.07€ |

| CHI | −2.08E−01 | 0 *** | −20.814% | ||

| Model 3—ARDL(2, 2, 2) | WEP | −5.01E−05 | 0.0443 ** | −0.005% | −0.05€ |

| EPI | −1.06E−01 | 0 *** | −10.560% | ||

| Model 4—ARDL (7, 2, 2) | WEP | −9.11E−05 | 0.0201 ** | −0.009% | −0.09€ |

| CCC-19 | 7.09E−05 | 0.0006 *** | 0.007% | ||

| Model 5—ARDL(7, 3, 3) | WEP | −6.33E−08 | 9.99E-01 | 0.000% | 0.00€ |

| CCD-19 | 2.44E−03 | 0.0001 *** | 0.244% |

| Models | M.1—ARDL(2, 2, 2) | M.2—ARDL(2, 2, 2) | M.3—ARDL(2, 2, 2) | M.4—ARDL (7, 2, 2) | M.5—ARDL(7, 3, 3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Prob | Coefficient | Prob | Coefficient | Prob | Coefficient | Prob | Coefficient | Prob |

| COINTEQ01 | −0.253283 | 0 | −0.252424 | 0 | −0.23823 | 0 | −0.124524 | 0 | −0.114209 | 0 |

| D(LEP(-1)) | −0.01865 | 0.3688 | −0.019212 | 0.3653 | −0.025792 | 0.2187 | −0.148417 | 0 | −0.158345 | 0 |

| D(LEP(-2)) | −0.150052 | 0 | −0.190569 | 0 | ||||||

| D(LEP(-3)) | −0.100086 | 0.0011 | −0.1008 | 0.002 | ||||||

| D(LEP(-4)) | −0.100868 | 0 | −0.099988 | 0 | ||||||

| D(LEP(-5)) | −0.10459 | 0.0178 | −0.107992 | 0.0161 | ||||||

| D(LEP(-6)) | −0.06736 | 0 | −0.069974 | 0 | ||||||

| D(WEP) | 0.000176 | 0.2856 | 0.000178 | 0.283 | 0.000178 | 0.2869 | 0.000143 | 0.3722 | 0.000135 | 0.4218 |

| D(WEP(-1)) | 0.000176 | 0.0267 | 0.000177 | 0.0261 | 0.000176 | 0.0278 | 0.000153 | 0.0412 | 0.000145 | 0.0725 |

| D(WEP(-2)) | 2.32E−06 | 0.9609 | ||||||||

| D(GSI) | 0.038117 | 0.307 | ||||||||

| D(GSI(-1)) | −0.051398 | 0.3524 | ||||||||

| D(CHI) | 0.00315 | 0.8702 | ||||||||

| D(CHI(-1)) | −0.035815 | 0.5638 | ||||||||

| D(EPI) | 0.016662 | 0.4817 | ||||||||

| D(EPI(-1)) | −0.051328 | 0.1118 | ||||||||

| D(CCC-19) | 0.002029 | 0.0685 | ||||||||

| D(CCC-19(-1)) | −0.001071 | 0.262 | ||||||||

| D(CCD-19) | 0.06454 | 0.1995 | ||||||||

| D(CCD-19(-1)) | −0.069117 | 0.219 | ||||||||

| D(CCD-19(-2)) | 0.081761 | 0.1751 | ||||||||

| C | −34.08625 | 0 | −38.05059 | 0 | −35.36801 | 0 | 3.705778 | 0 | 2.543353 | 0.0001 |

| @TREND | 0.015924 | 0 | 0.017584 | 0 | 0.016033 | 0 | ||||

| Significant | ||||||||||

| Not significant | ||||||||||

| Ho: Does Not Homogeneously Cause | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables/Prob. | LEP | WEP | GSI | EPI | CHI | CCC-19 | CCD-19 |

| LEP | 0 | 0.8379 | 0.8345 | 0.5096 | 0 | 0 | |

| WEP | 0 | 0.0007 | 0.5346 | 0.0021 | 0 | 0 | |

| GSI | 0.0648 | 0 | 0 | 0.0024 | 0.0754 | 0 | |

| EPI | 0.012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0088 | 0 | |

| CHI | 0.4089 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0727 | 0 | |

| CCC-19 | 0 | 0.7480 | 0 | 0.0001 | 0 | 0 | |

| CCD-19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1785 | 0.0038 | 0 | |

| Significant at 1% or 5% | |||||||

| Significant at 10% | |||||||

| Not significant | |||||||

References

- Ahmad, T.; Baig, M.; Hui, J. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic and Economic Impact. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juergensen, J.; Guimón, J.; Narula, R. European SMEs Amidst the COVID-19 Crisis: Assessing Impact and Policy Responses. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2020, 47, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maital, S.; Barzani, E. The Global Economic Impact of COVID-19: A Summary of Research; Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy Research: Haifa, Israel, 2020; pp. 1–12. Available online: https://www.neaman.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Global-Economic-Impact-of-COVID19_20200422171634.350.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Mastropietro, P.; Rodilla, P.; Batlle, C. Emergency Measures to Protect Energy Consumers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Global Review and Critical Analysis. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 68, 101678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Suomalainen, K.; Sharp, B.; Yi, M.; Sheng, M.S. Impact of wind-hydro dynamics on electricity price: A seasonal spatial econometric analysis. Energy 2022, 238, 122076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pointel, J.B. La Réglementation Economique dans les Pays Scandinaves de L’union Européenne. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01794518/document (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Sovacool, B.K. The avian benefits of wind energy: A 2009 update. Renew. Energy 2013, 49, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, E.A.; Ulfarsson, G.F.; Gardarsson, S.M.; Matthiasson, T. The effect of wind energy production on cross-border electricity pricing: The case of western Denmark in the Nord Pool market. Econ. Anal. Policy 2018, 58, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, S.; Morthorst, P.E.; Awerbuch, S. The Economics of Wind Energy; European Wind Energy Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2009; Volume 3, Available online: https://www.unioviedo.es/ate/manuel/seasturlab/EWEA.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Mertens, S. Wind Energy in the Built Environment; Multi Science Publishing Company: Brentwood, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, V. Wind Energy: Renewable Energy and the Environment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Izquierdo, M.; del Río, P. An analysis of the socioeconomic and environmental benefits of wind energy deployment in Europe. Renew. Energy 2020, 160, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidur, R.; Rahim, N.A.; Islam, M.R.; Solangi, K.H. Environmental impact of wind energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2423–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarin, S.A.; Bello, M.O. Wind energy and sustainable electricity generation: Evidence from Germany. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 9185–9198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, S. Impacts of wind energy on the environment: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Priya, B.; Srivastava, S.K. Response to the COVID-19: Understanding Implications of Government Lockdown Policies. J. Policy Model. 2021, 43, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allcott, H.; Braghieri, L.; Eichmeyer, S.; Gentzkow, M. The Welfare Effects of Social Media. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 629–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeletos, G.M.; Pavan, A. Efficient Use of Information and Social Value of Information. Econometrica 2007, 75, 1103–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargain, O.; Aminjonov, U. Trust and Compliance to Public Health Policies in Times of COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 2020, 192, 104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmendier, U.; Nagel, S. Depression Babies: Do Macroeconomic Experiences Affect Risk Taking? Q. J. Econ. 2011, 126, 373–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonov, A.; Sacher, S.; Dubé, J.P.; Biswas, S. Frontiers: The persuasive effect of Fox News: Noncompliance with social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mark. Sci. 2022, 41, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, R.K.; Brooks, S.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Rubin, G.J. How to improve adherence with quarantine: Rapid review of the evidence. Public Health 2020, 182, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, M.; Ho, T.K.; Tsang, A. Containment Measures during the COVID Pandemic: The Role of Non-Pharmaceutical Health Policies. J. Policy Model. 2023, 45, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, P.M.R.; Mariano, S.J.P.S.; Calado, M.R.A.; Pombo, J.A.N. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Electric Energy Load and Pricing in the Iberian Electricity Market. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 4833–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, K. The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effect on Electricity Consumption in Sweden. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:1809315 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Pradhan, A.K.; Rout, S.; Khan, I.A. Does market concentration affect wholesale electricity prices? An analysis of the Indian electricity sector in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Util. Policy 2021, 73, 101305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigerna, S.; Bollino, C.A.; D’Errico, M.C.; Polinori, P. COVID-19 Lockdown and Market Power in the Italian Electricity Market. Energy Policy 2022, 161, 112700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Facing the Electricity Crisis in Europe. 2020. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/lu/en/Industries/energy/research/facing-the-electricity-crisis-in-europe.html (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- González-López, R.; Ortiz-Guerrero, N. Integrated Analysis of the Mexican Electricity Sector: Changes during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Electr. J. 2022, 35, 107142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lopez, M.; Moreno, R.; Alvarado, D.; Suazo-Martínez, C.; Negrete-Pincetic, M.; Olivares, D.; Basso, L.J. The diverse impacts of COVID-19 on electricity demand: The case of Chile. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 138, 107883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, I.; Moreno-Munoz, A.; Quintero-Jiménez, P.; Garcia-Torres, F.; Gonzalez-Redondo, M.J. Electricity demand during pandemic times: The case of the COVID-19 in Spain. Energy Policy 2021, 148, 111964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Tan, Z.; He, Y.; Xie, L.; Kang, C. Implications of COVID-19 for the electricity industry: A comprehensive review. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 6, 489–495. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9160443/ (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Leach, A.; Rivers, N.; Shaffer, B. Canadian Electricity Markets during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Initial Assessment. Can. Public Policy 2020, 46, S145–S159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczygielski, J.J.; Brzeszczyński, J.; Charteris, A.; Bwanya, P.R. The COVID-19 storm and the energy sector: The impact and role of uncertainty. Energy Econ. 2022, 109, 105258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, N.; Zarazua de Rubens, G.Z.; Enevoldsen, P.; Behzadi Forough, A. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Electricity Sector in Spain: An Econometric Approach Based on Prices. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 6320–6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, G.; Wu, J.; Zhong, H.; Xia, Q.; Xie, L. Quantitative assessment of US bulk power systems and market operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Energy 2021, 286, 116354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbrügge, S.; Schott, P.; Weibelzahl, M.; Buhl, H.U.; Fridgen, G.; Schöpf, M. How Did the German and Other European Electricity Systems React to the COVID-19 Pandemic? Appl. Energy 2021, 285, 116370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akrofi, M.M.; Antwi, S.H. COVID-19 Energy Sector Responses in Africa: A Review of Preliminary Government Interventions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 68, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, V.B.; Bonatto, B.D.; Pereira, L.C.; Silva, P.F. Analysis of the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Brazilian Distribution Electricity Market Based on a Socioeconomic Regulatory Model. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 132, 107172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazo, J.; Aguirre, G.; Watts, D. An Impact Study of COVID-19 on the Electricity Sector: A Comprehensive Literature Review and Ibero-American Survey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, C.K.; Zarnikau, J.; Kadish, J.; Horowitz, I.; Wang, J.; Olson, A. The impact of wind generation on wholesale electricity prices in the hydro-rich Pacific Northwest. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 4245–4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, V.; Ansari, M.A. Wind farm integration effect on electricity market price. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Energy Efficient Technologies for Sustainability (ICEETS), Nagercoil, India, 10–12 April 2013; pp. 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Nieta, A.A.S.; Contreras, J.; Munoz, J.I.; O’Malley, M. Modeling the Impact of a Wind Power Producer as a Price-Maker. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2014, 29, 2723–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketterer, J.C. The Impact of Wind Power Generation on the Electricity Price in Germany. Energy Econ. 2014, 44, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Curtis, J. The Effects of Wind Generation Capacity on Electricity Prices and Generation Costs: A Monte Carlo Analysis. Appl. Econ. 2016, 48, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Dehkordi, P.; Rakai, L.; Zareipour, H.; Rosehart, W. Big data analytics for modeling the impact of wind power generation on competitive electricity market prices. In Proceedings of the 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; pp. 2528–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancucci Martinez-Anido, C.; Brinkman, G.; Hodge, B.M. The Impact of Wind Power on Electricity Prices. Renew. Energy 2016, 94, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhmad, F.; Percebois, J. Wind Power Feed-In Impact on Electricity Prices in Germany 2009–2013. Eur. J. Comp. Econ. 2016, 13, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Badyda, K.; Dylik, M. Analysis of the Impact of Wind on Electricity Prices Based on Selected European Countries. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makalska, T.; Varfolomejeva, R.; Oleksijs, R. The Impact of Wind Generation on the Spot Market Electricity Pricing. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2018 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe, EEEIC/I and CPS Europe 2018, Palermo, Italy, 12–15 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirdemo, A. The Impact of Wind Power Production on Electricity Price Volatility. Master’s Thesis, Luleå Tekniska Universitet, Luleå, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Csereklyei, Z.; Qu, S.; Ancev, T. The Effect of Wind and Solar Power Generation on Wholesale Electricity Prices in Australia. Energy Policy 2019, 131, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Sun, R.; Guo, F. Impact of Renewable Energy Power Generation Share on Germany’s Electricity Prices. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.P.; Rodrigues, P.M.M. The impact of wind generation on the mean and volatility of electricity prices in Portugal. In Proceedings of the 2015 12th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Lisbon, Portugal, 19–22 May 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineau, P.-O.; Nasseri, Y.; Rafizadeh, N. The Effects of Wind Power Generation on the Electricity Price: High Frequency Evidence from New York. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Veraart, A. Modelling the impact of wind power production on electricity prices by regime-switching Levy semistationary processes. SSRN Electron. J. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dorrell, J.; Lee, K. The Price of Wind: An Empirical Analysis of the Relationship Between Wind Energy and Electricity Price Across the Residential, Commercial, and Industrial Sectors. Energies 2021, 14, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulm, L.; Koduvere, H.; Palu, I. ‘Discount’-the renewable energy production impact on electricity price. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 61st Annual International Scientific Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering of Riga Technical University, RTUCON 2020—Proceedings, Riga, Latvia, 5–7 November 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doering, K.; Sendelbach, L.; Steinschneider, S.; Anderson, C.L. The Effects of Wind Generation and Other Market Determinants on Price Spikes. Appl. Energy 2021, 300, 117316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Sharp, B.; Suomalainen, K.; Sheng, M.S.; Guang, F. The impact of COVID-19 containment measures on changes in electricity demand. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2022, 29, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ederer, N. The Market Value and Impact of Offshore Wind on the Electricity Spot Market: Evidence from Germany. Appl. Energy 2015, 154, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosius, E.; Seebaß, J.V.; Wacker, B.; Schlüter, J.C. The Impact of Offshore Wind Energy on Northern European Wholesale Electricity Prices. Appl. Energy 2023, 341, 120910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirth, L. The Market Value of Variable Renewables: The Effect of Solar Wind Power Variability on Their Relative Price. Energy Econ. 2013, 38, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, M.; Fürsch, M. The Impact of an Increasing Share of RES-E on the Conventional Power Market—The Example of Germany. Z. Energiewirtschaft 2009, 33, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, M.; Keeley, A.R.; Matsumoto, K.I.; Tanaka, K.; Managi, S. Beyond the merit order effect: Impact of the rapid expansion of renewable energy on electricity market price. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 114037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreouli, E.; Brice, E. Citizenship under COVID-19: An Analysis of UK Political Rhetoric during the First Wave of the 2020 Pandemic. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 32, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Miera, G.S.; del Río González, P.; Vizcaíno, I. Analyzing the Impact of Renewable Electricity Support Schemes on Power Prices: The Case of Wind Electricity in Spain. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 3345–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, Á.; Ortega, Á. A Structural Analysis of the Merit-Order Effect in the Spanish Day-Ahead Power Market; Working Paper; UC3M; Universidad Carlos III de Madrid: Getafe, Spain, 2021; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10016/33298 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Bell, W.P.; Wild, P.; Foster, J.; Hewson, M. Revitalising the Wind Power Induced Merit Order Effect to Reduce Wholesale and Retail Electricity Prices in Australia. Energy Econ. 2017, 67, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, D.P.; Marques, A.C.; Damette, O. The Merit-Order Effect on the Swedish Bidding Zone with the Highest Electricity Flow in the Elspot Market. Energy Econ. 2021, 102, 105465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, N.C.; da Silva, P.P. The “Merit-Order Effect” of Wind and Solar Power: Volatility and Determinants. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 102, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, B.; Selcuk, O.; Dastan, S.A. The Merit Order Effect of Wind and River Type Hydroelectricity Generation on Turkish Electricity Prices. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 1298–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azofra, D.; Jiménez, E.; Martínez, E.; Blanco, J.; Saenz-Díez, J.C. Wind Power Merit-Order and Feed-in-Tariffs Effect: A Variability Analysis of the Spanish Electricity Market. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 83, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clò, S.; Cataldi, A.; Zoppoli, P. The Merit-Order Effect in the Italian Power Market: The Impact of Solar and Wind Generation on National Wholesale Electricity Prices. Energy Policy 2015, 77, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.; Sá, J.; Santana, J. Renewable Generation, Support Policies and the Merit Order Effect: A Comprehensive Overview and the Case of Wind Power in Portugal. In Electricity Markets with Increasing Levels of Renewable Generation: Structure, Operation, Agent-Based Simulation, and Emerging Designs; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 227–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cludius, J.; Hermann, H.; Matthes, F.C.; Graichen, V. The Merit Order Effect of Wind and Photovoltaic Electricity Generation in Germany 2008–2016: Estimation and Distributional Implications. Energy Econ. 2014, 44, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensfuß, F.; Ragwitz, M.; Genoese, M. The merit-order effect: A detailed analysis of the price effect of renewable electricity generation on spot market prices in Germany. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 3086–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, S.; Bushnell, J.B. Are Residential Electricity Prices Too High or Too Low?: Or Both? Working Paper, No. 24756; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Antweiler, W.; Muesgens, F. On the Long-Term Merit Order Effect of Renewable Energies. Energy Econ. 2021, 99, 105275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Kakhbod, A.; Ozdaglar, A. Competition in Electricity Markets with Renewable Energy Sources. Energy J. 2017, 38 (Suppl. S1), 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.; Vasilakos, N.V. The Long-Term Impact of Wind Power on Electricity Prices and Generating Power. ESRC Centre for Competition Policy Working Paper Series. 2011. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1851311 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Bublitz, A.; Keles, D.; Fichtner, W. An Analysis of the Decline of Electricity Spot Prices in Europe: Who Is to Blame? Energy Policy 2017, 107, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askitas, N.; Tatsiramos, K.; Verheyden, B. Estimating Worldwide Effects of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions on COVID-19 Incidence and Population Mobility Patterns Using a Multiple-Event Study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1972 Available online:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B.H. A Companion to Econometric Analysis of Panel Data; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/A+Companion+to+Econometric+Analysis+of+Panel+Data-p-9780470744031 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Okui, R.; Wang, W. Heterogeneous Structural Breaks in Panel Data Models. J. Econom. 2021, 220, 447–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J. Panel Data Models with Interactive Fixed Effects. Econometrica 2009, 77, 1229–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Perron, B.; Moon, H.; Perron, B. Testing for a Unit Root in Panels with Dynamic Factors. J. Econom. 2004, 122, 81–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. J. Appl. Econom. 2007, 22, 265–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.S.; Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. Testing for Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panels. J. Econom. 2003, 115, 53–74. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/econom/v115y2003i1p53-74.html (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Kao, C. Spurious Regression and Residual-Based Tests for Cointegration in Panel Data. J. Econom. 1999, 90, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. Critical Values for Cointegration Tests in Heterogeneous Panels with Multiple Regressors. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1999, 61, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P.; Pedroni, P. Panel Cointegration: Asymptotic and Finite Sample Properties of Pooled Time Series Tests with an Application to the PPP Hypothesis. Econom. Theory 2004, 20, 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J. Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2007, 69, 709–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J.; Edgerton, D.L. A simple test for cointegration in dependent panels with structural breaks. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2008, 70, 665–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persyn, D.; Westerlund, J. Error-correction–based cointegration tests for panel data. Stata J. 2008, 8, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.P. Pooled Mean Group Estimation of Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999, 94, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.; Gachino, G.; Hoque, A. Electricity Consumption and Economic Growth in the GCC Countries: Panel Data Analysis. Energy Policy 2016, 98, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, K.; Begum, R.A.; Syed Abdullah, S.M.; Jaafar, M. Dynamics of energy use, technological innovation, economic growth and trade openness in Malaysia. Energy 2015, 90, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolde-Rufael, Y.; Weldemeskel, E.M. Environmental policy stringency, renewable energy consumption, and CO2 emissions: Panel cointegration analysis for BRIICTS countries. Energy Policy 2020, 17, 568–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogwijk, M.; Van Vuuren, D.; de Vries, B.; Turkenburg, W. Exploring the Impact on Cost and Electricity Production of High Penetration Levels of Intermittent Electricity in OECD Europe and the USA, Results for Wind Energy. Energy 2007, 32, 1381–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaraite, J.; Kažukauskas, A.; Brännlund, R.; Chandra, K.; Kriström, B. Intermittency and Pricing Flexibility in Electricity Markets. SSRN Electron. J. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhout, F.; Brand, A. The Impact of Wind Power on Day-Ahead Electricity Prices in The Netherlands. In Proceedings of the 2011 8th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Zagreb, Croatia, 25–27 May 2011; pp. 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauritzen, J. What Happens When It’s Windy in Denmark? An Empirical Analysis of Wind Power on Price Variability in the Nordic Electricity Market. SSRN Electron. J. 2012, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martí-Ballester, C.P. Do Renewable Energy Mutual Funds Advance Towards Clean Energy-Related Sustainable Development Goals? Renew. Energy 2022, 195, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, E.E.O.; Acheampong, A.O. Energy Justice and Economic Growth: Does Democracy Matter? J. Policy Model. 2023, 45, 160–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, J.D.; Morris, S.; Shin, H.S. Communication and Monetary Policy. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2002, 18, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.; Shin, H.S. Social Value of Public Information. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1521–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.; Naeem, M.A. Clean Energy, Australian Electricity Markets, and Information Transmission. Energy Res. Lett. 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roques, F.A.; Newbery, D.M.; Nuttall, W.J. Investment incentives and electricity market design: The British experience. Rev. Netw. Econ. 2005, 4, 93–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidukienė, L.; Skaistė, G. Sustainable Development of Lithuanian Electricity Energy Sector. J. Econ. Dev. Stud. 2013, 1, 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Johansson, D.J. Adapting to uncertainty: Modeling adaptive investment decisions in the electricity system. Appl. Energy 2024, 358, 122603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, V.; Ercolano, S.; Pinto, M. Fighting the COVID Pandemic: National Policy Choices in Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions. J. Policy Model. 2022, 44, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgar, F.J.; Stefaniak, A.; Wohl, M.J. The Trouble with Trust: Time-Series Analysis of Social Capital, Income Inequality, and COVID-19 Deaths in 84 Countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 263, 113365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attila, J. Corruption, Globalization and the Outbreak of COVID-19. SSRN Working Paper. 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3742347 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Ezeibe, C.C.; Ilo, C.; Ezeibe, E.N.; Oguonu, C.N.; Nwankwo, N.A.; Ajaero, C.K.; Osadebe, N. Political Distrust and the Spread of COVID-19 in Nigeria. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1753–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebka, B.; Kanungo, R.P.; Wildman, J. The Transition from COVID-19 Infections to Deaths: Do Governance Quality and Corruption Affect It? J. Policy Model. 2024, 46, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffron, R.J.; Körner, M.F.; Schöpf, M.; Wagner, J.; Weibelzahl, M. The Role of Flexibility in the Light of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond: Contributing to a Sustainable and Resilient Energy Future in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaïd, F.; Al-Sarihi, A.; Al-Mestneer, R. Balancing Climate Mitigation and Energy Security Goals amid Converging Global Energy Crises: The Role of Green Investments. Renew. Energy 2023, 205, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marugán, A.P.; Márquez, F.P.G.; Perez, J.M.P.; Ruiz-Hernández, D. A Survey of Artificial Neural Network in Wind Energy Systems. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 1822–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiaw, L.; Sow, G.; Fall, S. Application of Neural Networks Technique in Renewable Energy Systems. Available online: https://ijssst.info/Vol-15/No-5/data/5198a006.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Lilleker, D.; Coman, I.A.; Gregor, M.; Novelli, E. Political Communication and COVID-19: Governance and Rhetoric in Global Comparative Perspective. In Political Communication and COVID-19; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 333–350. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/63306/9781003120254_webpdf.pdf?sequence=1#page=356 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Montiel, C.J.; Uyheng, J.; Dela Paz, E. The Language of Pandemic Leaderships: Mapping Political Rhetoric During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Polit. Psychol. 2021, 42, 747–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, N. Reforming European Electricity Markets: Lessons from the Energy Crisis. Energy Econ. 2023, 126, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerdalli, S.; Trabelsi, E. Impact of Wind Energy Production on Nord Pool Electricity Market Prices Pre and During COVID-19. In Proceedings of the Conférence Internationale sur les Sciences Appliquées et l’Innovation (CISAI-2023), Sousse, Tunisia, 10–11 July 2023; Proceedings of Engineering & Technology. Volume 77. [Google Scholar]

- Aldy, J.E.; Gerarden, T.D.; Sweeney, R.L. Investment versus Output Subsidies: Implications of Alternative Incentives for Wind Energy. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2023, 10, 981–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizamir, S.; Iravani, F.; Yücel, Ş. Investment in Wind Energy: The Role of Subsidies. Georgetown McDonough School of Business Research Paper 3868573. 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3868573 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Idsø, J. Growth and Economic Performance of the Norwegian Wind Power Industry and Some Aspects of the Nordic Electricity Market. Energies 2021, 14, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesten, E.; Jolink, A.; Chappin, M. Investments in the Dutch Onshore Wind Energy Industry: A Review of Investor Profiles and the Impact of Renewable Energy Subsidies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2519–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechmann, A.; Barlas, T.; Madsen, H.A. Incorporating Electricity Prices in Wind Turbine Design: Introducing the AEV Metric. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2745, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A.; Hand, M.; Wiser, R.; Lantz, E.; Dalla Riva, A.; Berkhout, V.; Lacal-Arántegui, R. Land-Based Wind Energy Cost Trends in Germany, Denmark, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, and the United States. Appl. Energy 2020, 277, 114777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seljom, P.; Tomasgard, A. Short-term uncertainty in long-term energy system models—A case study of wind power in Denmark. Energy Econ. 2015, 49, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, E.; Norén, V.; Madsen, H. Consumption Management in the Nord Pool Region: A Stability Analysis. Appl. Energy 2015, 146, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, C.V.; Mitu, N.E. Price behavior and market integration in European Union electricity markets: A VECM analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyndecka, M.A. EEA Law and the Climate Change. The Case of Norway. Pol. Rev. Int’l Eur. L 2020, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Bergot, A.; Liang, C.; Xiang, W.N.; Huang, Z. Environmental Issues Associated with Wind Energy—A Review. Renew. Energy 2015, 75, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Ahmed, Z.; Pata, U.K.; Kartal, M.T.; Erdogan, S. Do Investments in Green Energy, Energy Efficiency, and Nuclear Energy R&D Improve the Load Capacity Factor? An Augmented ARDL Approach. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, E.E.O.; Acheampong, A.O.; Aluko, O.A. Impact of Rural-Urban Energy Equality on Environmental Sustainability and the Role of Governance. J. Policy Model. 2024, 46, 304–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | MG | PMG | DFE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-run homogeneity | Fully heterogeneous (allows different long-run coefficients for each panel unit) | Homogeneous (imposes a common long-run relationship) | Homogeneous (imposes a common long-run relationship) |

| Short-run dynamics | Fully heterogeneous (each unit has different short-run coefficients) | Heterogeneous (each unit has different short-run coefficients) | Homogeneous (same short-run dynamics across all units) |

| Efficiency | Low (due to high parameter variability) | Higher than MG (due to imposed long-run homogeneity) | High, but at the cost of restrictive homogeneity |

| Suitability | Best when panel units are fundamentally different (e.g., cross-country studies with structural differences) | Best when long-run relationships are expected to be similar, but short-run adjustments vary | Best when both short- and long-run relationships are assumed to be identical across all units |

| Potential issue | High variability may lead to inefficient estimates | Risk of bias if long-run homogeneity assumption is incorrect | Overly restrictive, may produce biased estimates if true that short-run heterogeneity exists |

| Similar Findings | Long-Run Impact | Short-Run Impact | Explanation |

| [53] | Reduction in electricity prices | Greater availability of renewable energy sources, reducing the reliance on more expensive fossil fuel-based generation. | |

| [55] | Decline in average prices | The greater generation from wind power contributes to a decline in average prices, as wind energy is typically cheaper and reduces the overall cost of electricity production. | |

| [101] | Decline in the day-ahead electricity prices | When the load is relatively low (and hard to increase) and renewable energy resources are abundant, the low marginal costs of renewable energy could lead to prolonged periods of near-zero or even negative marginal electricity prices. | |

| [54] | Reduction in average prices | Increase in price volatility | Wind generation lowers average prices by adding more supply to the market, but it also increases price volatility due to the intermittent nature of wind power |

| [43] | Reduction in electricity prices | This can be attributed to the presence of wind power producers who have the ability to influence market prices through their generation capacity. By offering electricity at lower prices, they can contribute to overall price reductions in the market. | |

| [87] | Decrease in intraday price volatility | There is increased supply unpredictability when significant amounts of wind power are generated. | |

| [41] | Reduction in price level | Increase in price variance | As wind generation increases, it can contribute to lower average spot prices due to its cost-effectiveness, but the variability in wind availability can introduce uncertainty and increase price volatility. |

| [102] | Depressed average day-ahead prices | The functioning of energy market prices and policies is significantly impacted by the effects of uncertainty in forecasting renewable power. | |

| [100] | Depressed prices | As the share of wind power increases, it displaces more expensive conventional generation sources, thereby reducing the overall cost of electricity production and leading to lower prices. | |

| Different findings | Long-Run Impact | Short-Run Impact | Explanation |

| [57] | Increase in electricity prices | The positive relationship between wind energy and electricity prices is influenced by market dynamics, such as the costs associated with integrating intermittent renewable sources into the grid. | |

| [60] | Variation across seasons | The variation in price reduction across seasons suggests that factors like seasonal electricity demand patterns and the availability of other energy sources may affect the price impact of wind penetration. | |

| [52] | Increase in electricity prices | The positive relationship between wind and solar power generation and wholesale electricity prices could be attributed to increased investment costs and grid infrastructure required to integrate these intermittent sources. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guerdalli, S.; Trabelsi, E. COVID-19 and the Merit-Order Effect of Wind Energy: The Case of Nord Pool Electricity Markets. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9859. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219859

Guerdalli S, Trabelsi E. COVID-19 and the Merit-Order Effect of Wind Energy: The Case of Nord Pool Electricity Markets. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9859. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219859

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuerdalli, Seifeddine, and Emna Trabelsi. 2025. "COVID-19 and the Merit-Order Effect of Wind Energy: The Case of Nord Pool Electricity Markets" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9859. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219859

APA StyleGuerdalli, S., & Trabelsi, E. (2025). COVID-19 and the Merit-Order Effect of Wind Energy: The Case of Nord Pool Electricity Markets. Sustainability, 17(21), 9859. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219859