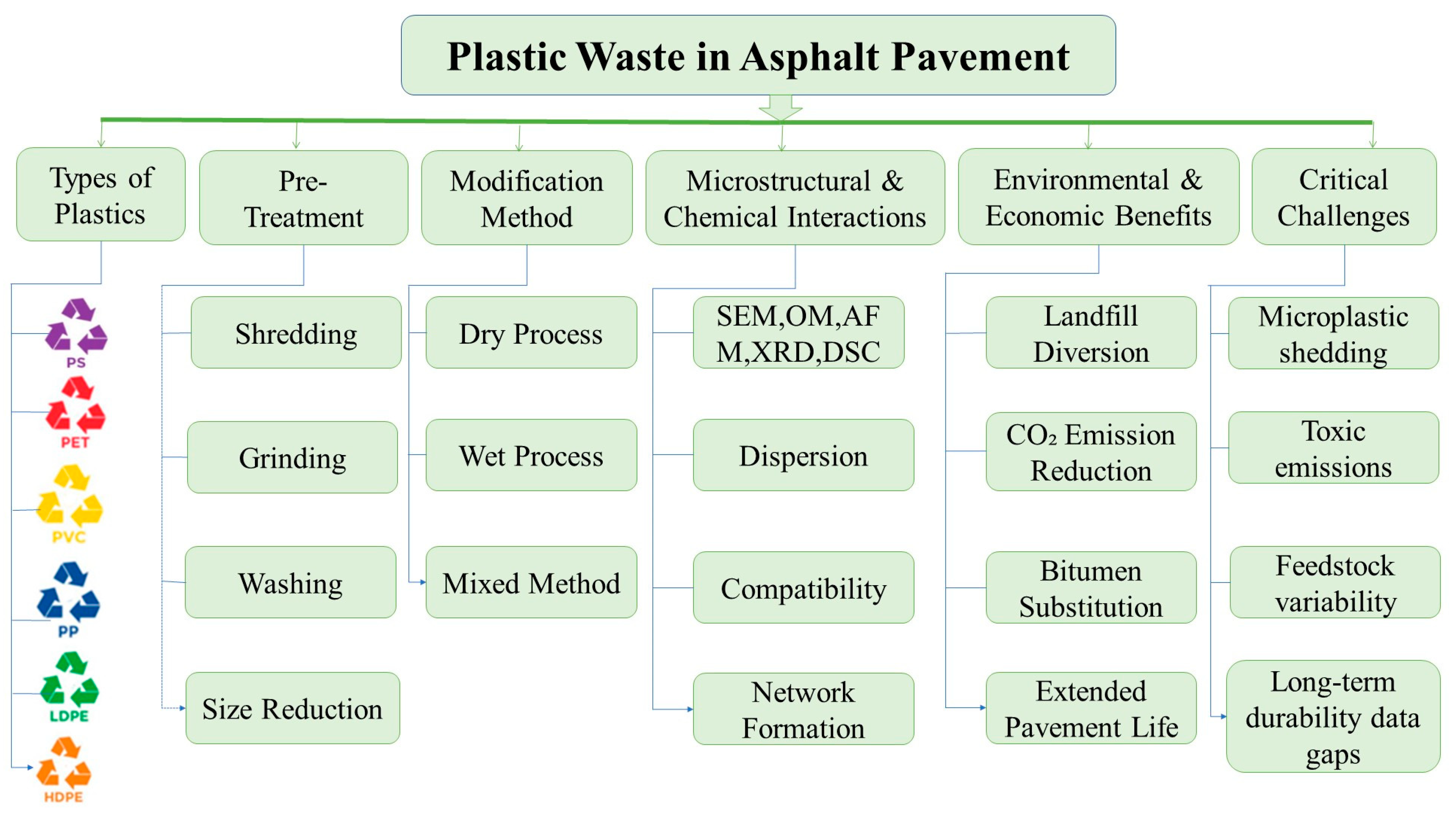

Plastic-Waste-Modified Asphalt for Sustainable Road Infrastructure: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

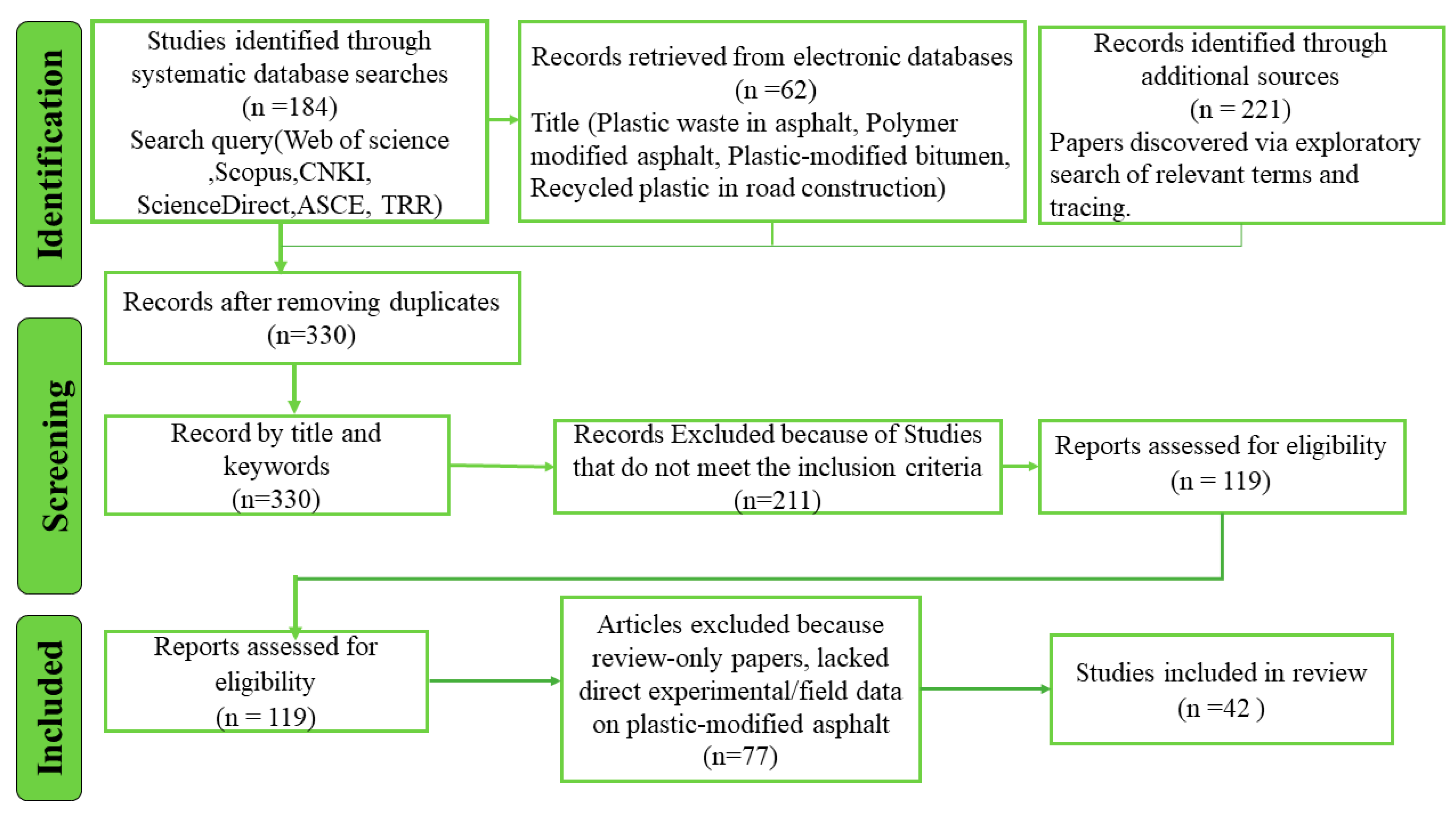

2. Objective and Methodology

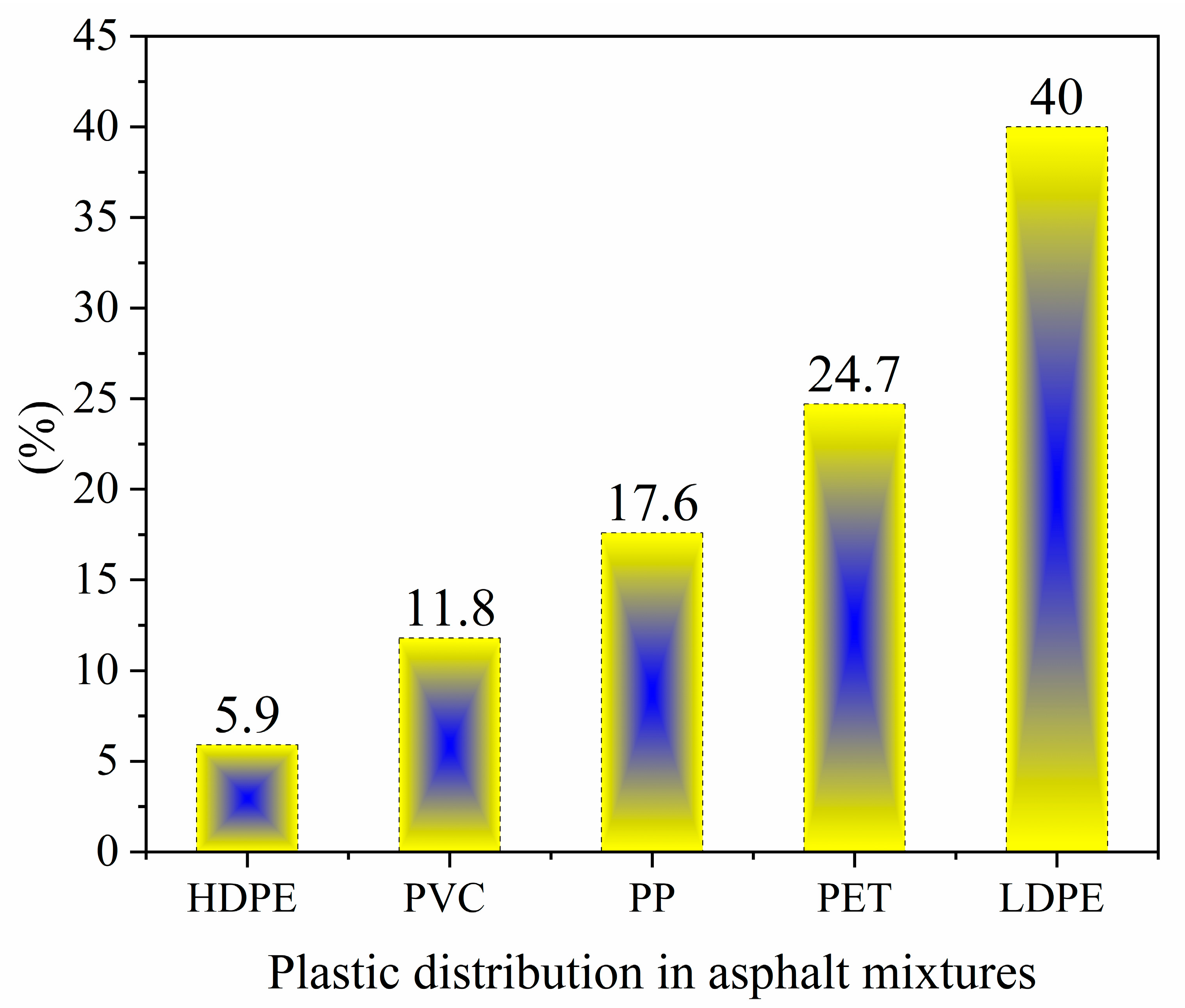

3. Plastic Classification

3.1. Pre-Treatment of Waste Plastics

3.2. Chemical and Thermal Degradation of Waste Plastics for Asphalt Modification

3.2.1. Chemical Degradation

3.2.2. Thermal Degradation

3.3. Integrating of Plastics in Asphalt Modification

3.3.1. Asphalt Modified with Plastic Using the Dry Process

3.3.2. Asphalt Modified with Plastic Using the Wet Process

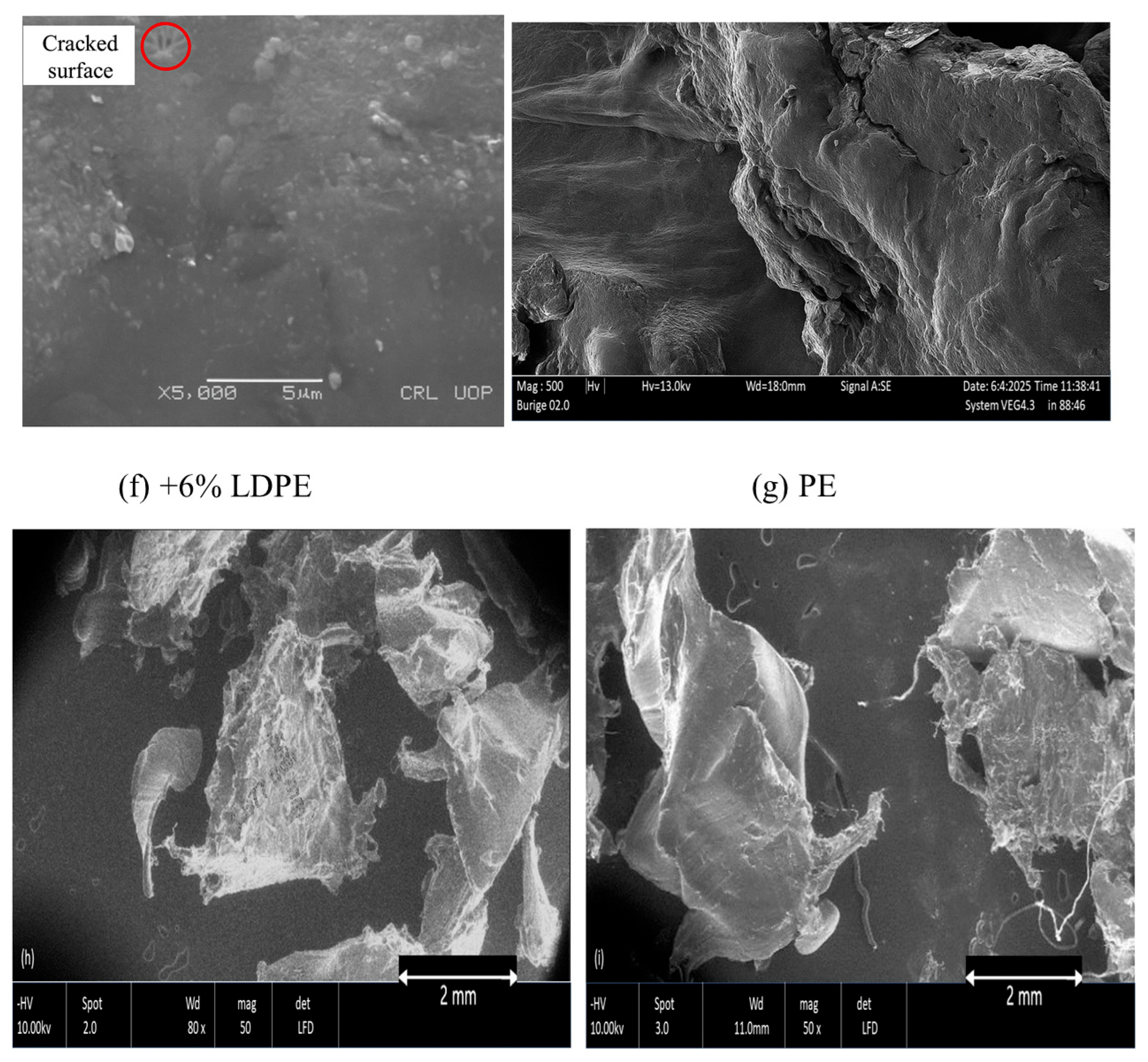

4. Microscopic Analysis of Recycled Plastic in Asphalt

Mechanisms of Micro-Level Modification

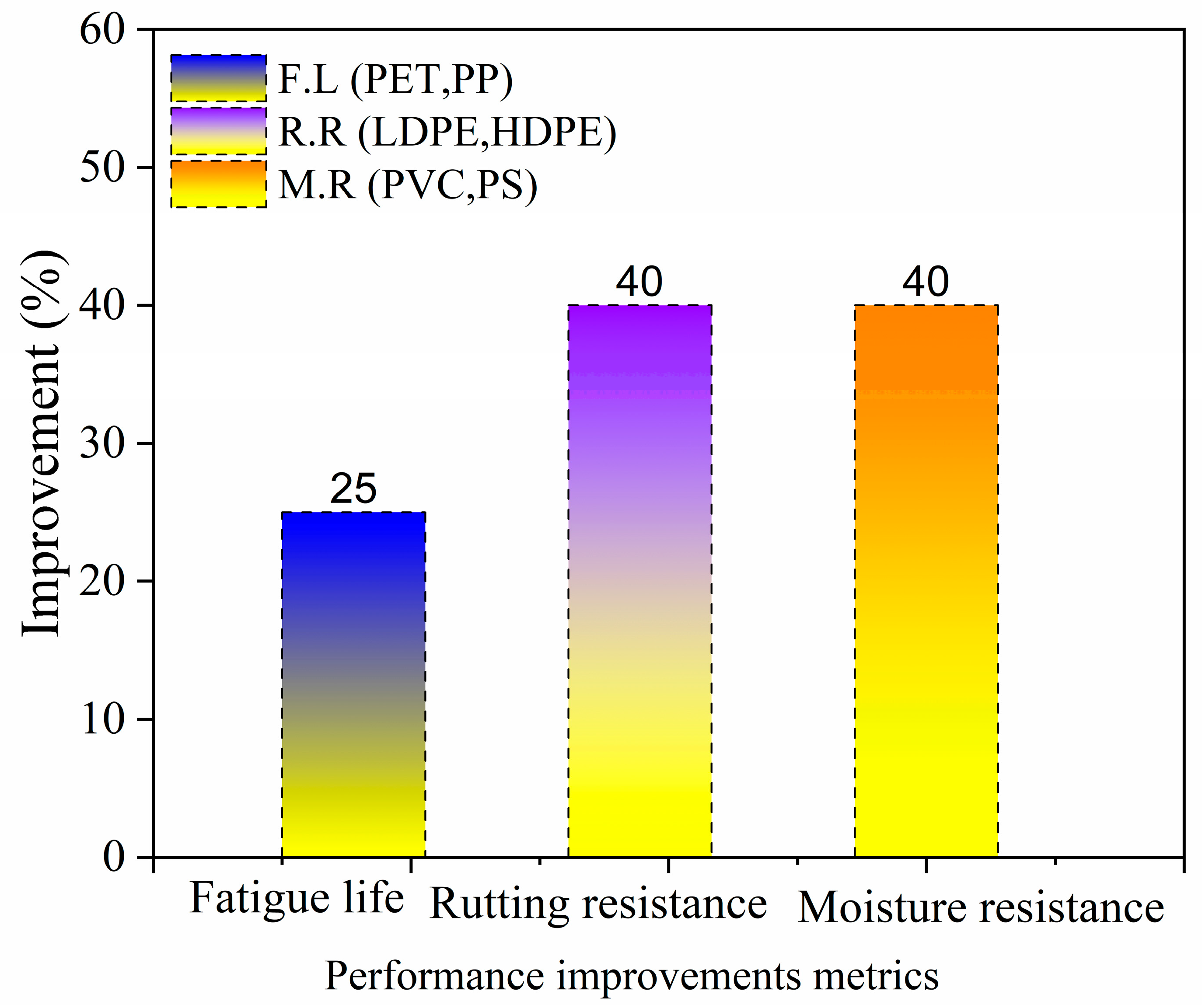

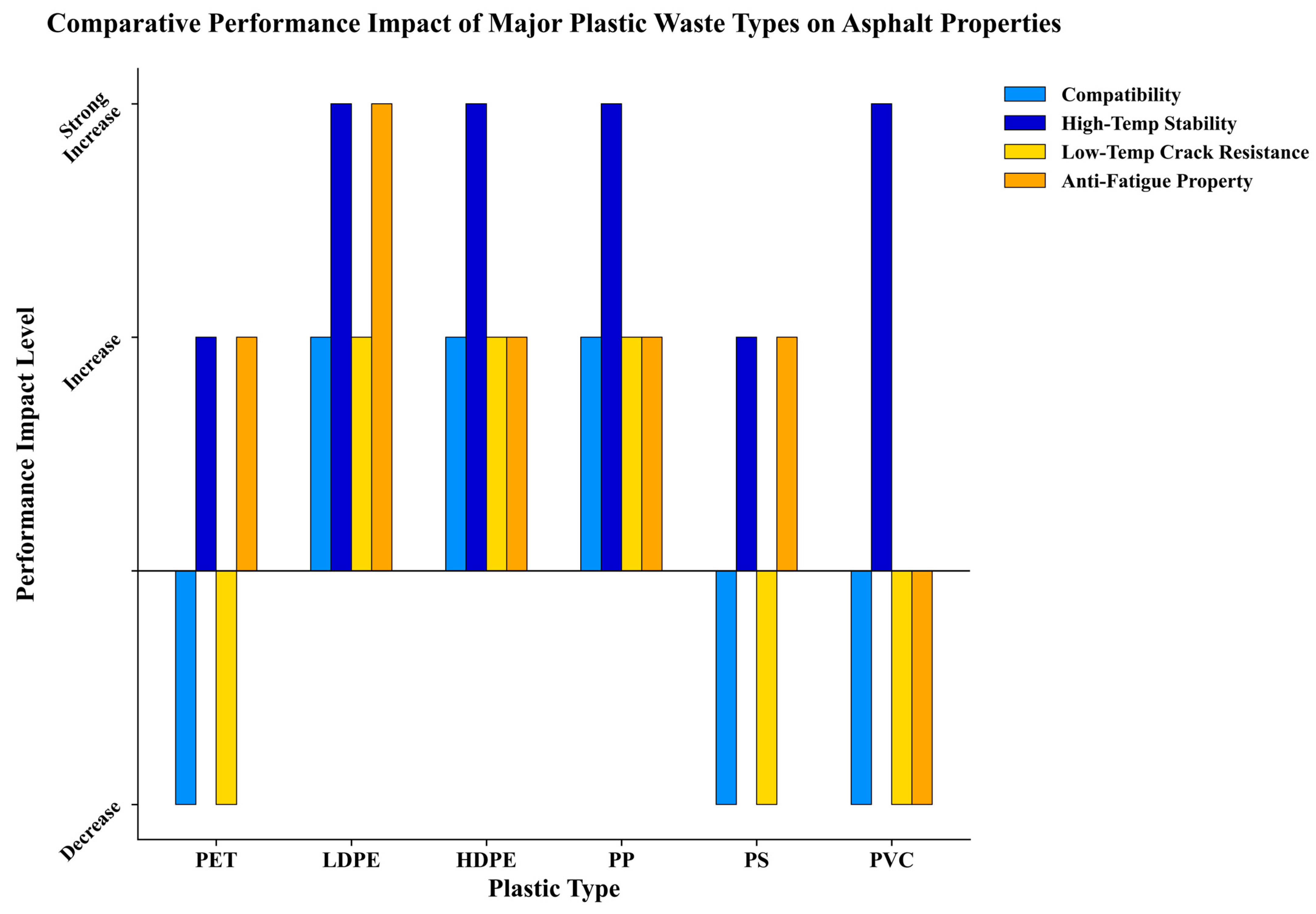

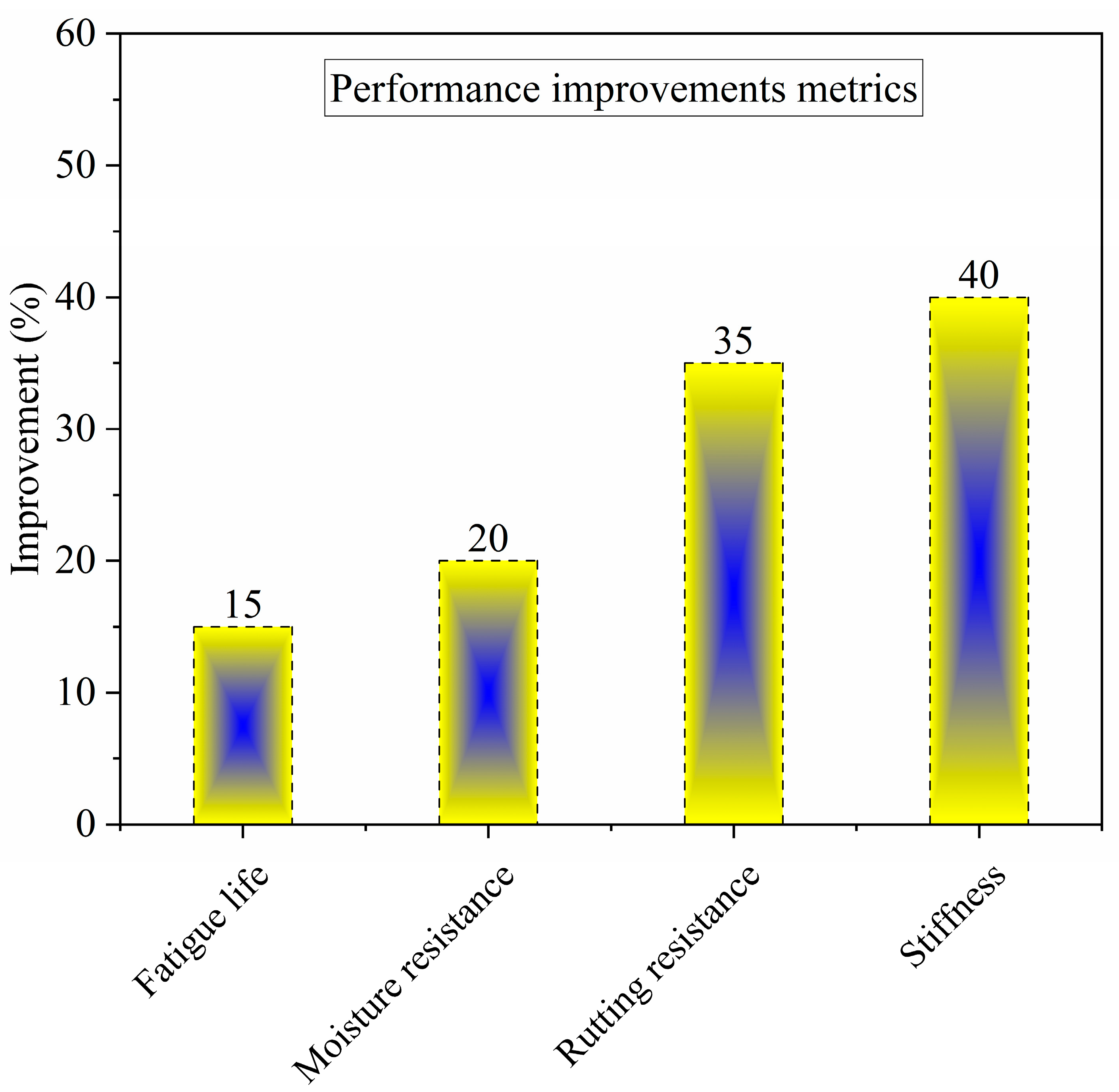

5. Road Performance of Plastic-Modified Asphalt

5.1. Rutting and High-Temperature Performance

5.2. Fatigue, Cracking, and Low-Temperature Behavior

5.3. Moisture Resistance and Durability

5.4. Compatibility and Storage Stability of Plastic-Modified Asphalt

5.5. Performance Variability

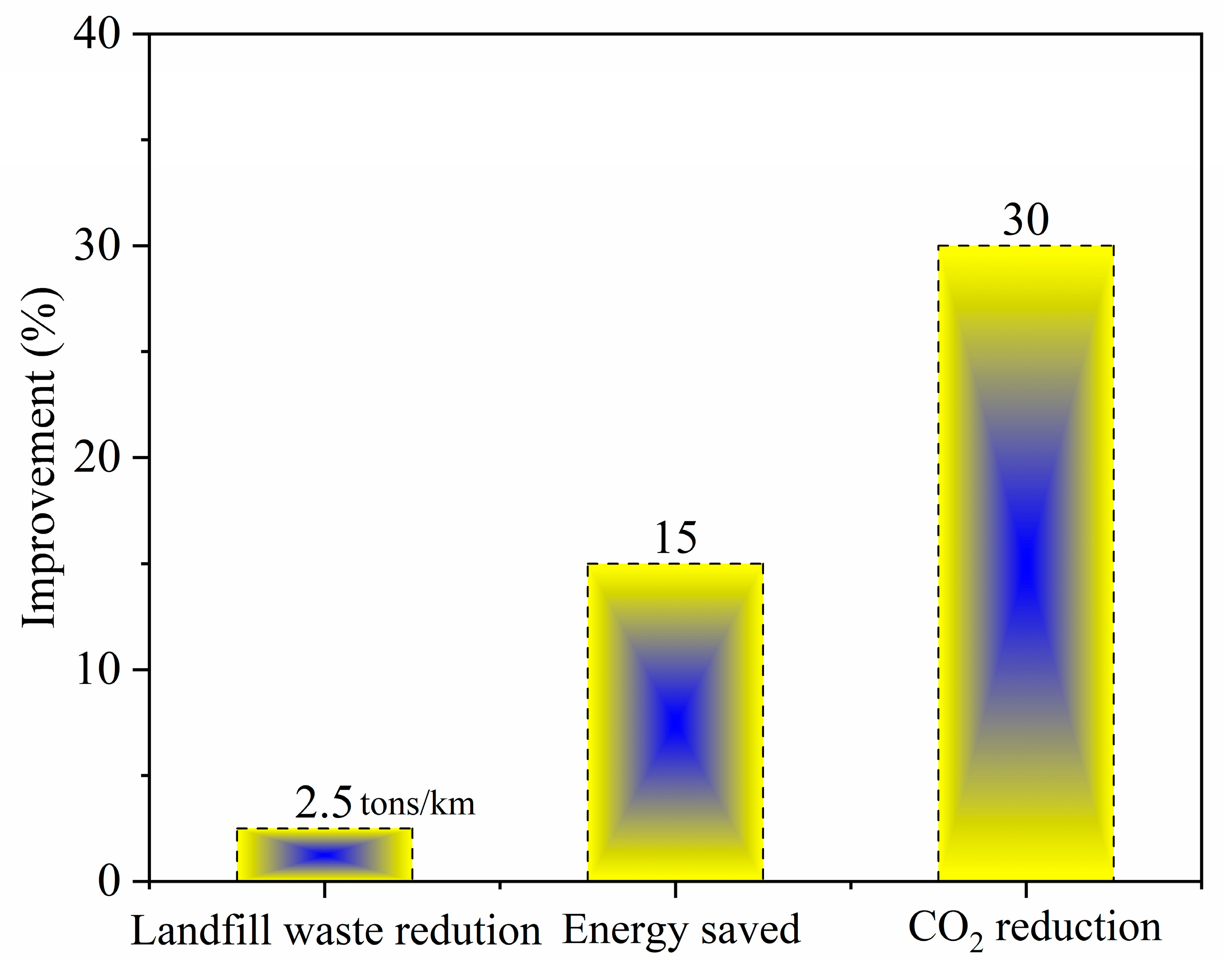

6. Environmental Concerns and Mitigation Strategies

6.1. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment

6.2. Economic Impact

7. Field Implementation of Waste Plastic in Asphalt Mixtures

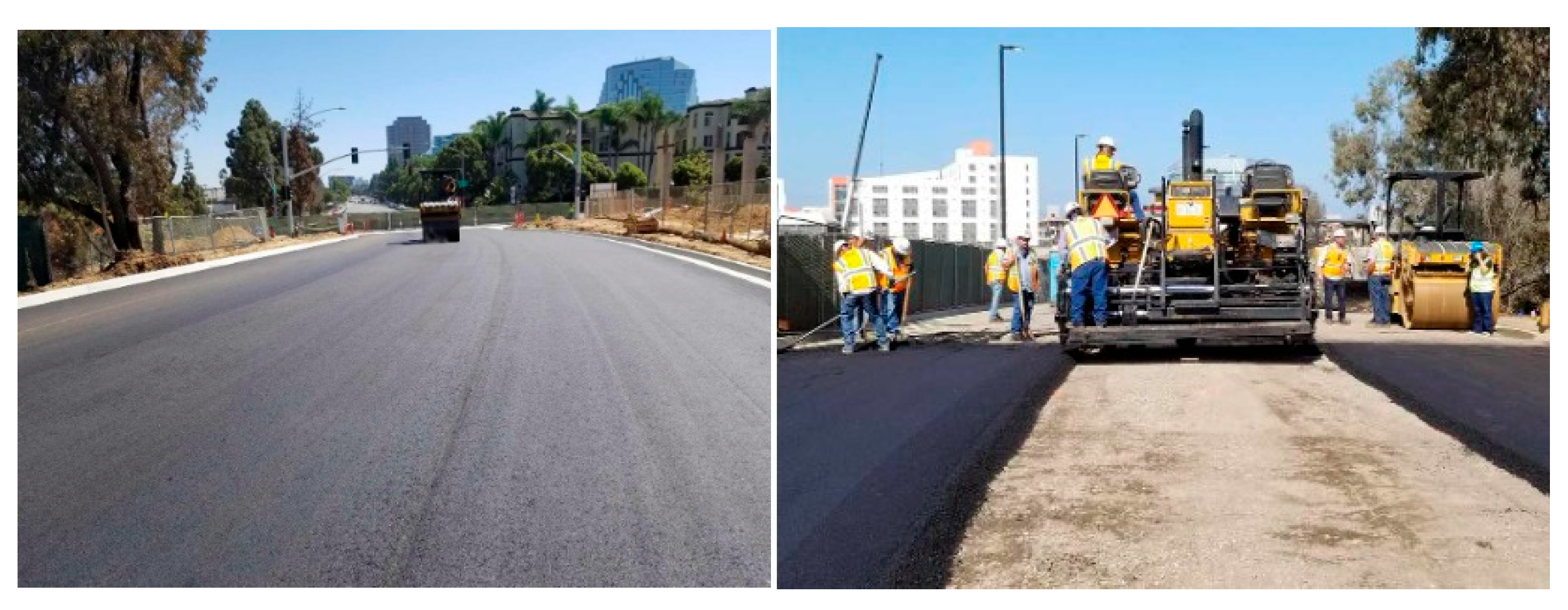

7.1. USA

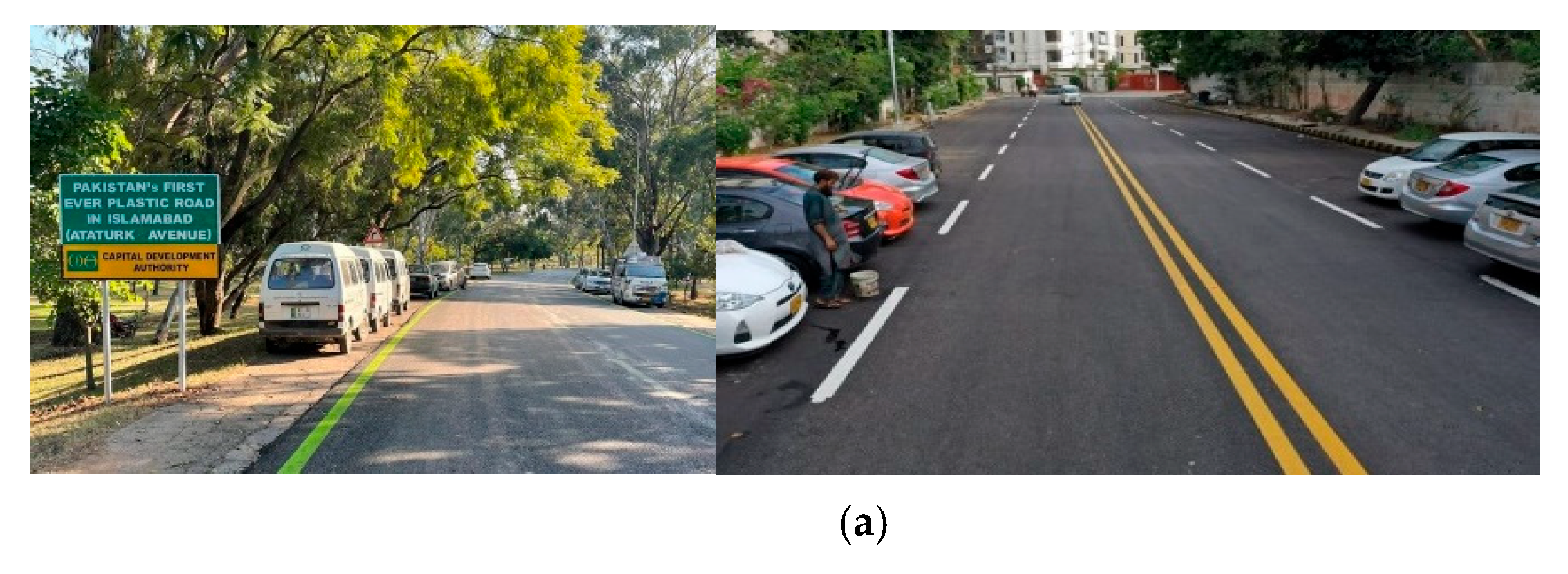

7.2. Pakistan

7.3. China

7.4. India

7.5. UK

7.6. Indonesia

8. Critical Challenges and Research Gaps

9. Conclusions

10. Future Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| LDPE | Low-density polyethylene |

| HDPE | High-density polyethylene |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| OM | Optical microscopy |

| FM | Fluorescence microscopy |

| ESEM | Environmental scanning electron microscopy |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Plastic Pollution. 2018. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the Future of Plastics. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_New_Plastics_Economy.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Pandey, P.; Dhiman, M.; Kansal, A.; Subudhi, S.P. Plastic Waste Management for Sustainable Environment: Techniques and Approaches. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2023, 5, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, P.; Kaur, D.P.; Raj, S.; Sorout, J. Recycling/Reuse of Plastic Waste as Construction Material for Sustainable Development: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 86156–86179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belioka, M.-P.; Achilias, D.S. How Plastic Waste Management Affects the Accumulation of Microplastics in Waters: A Review for Transport Mechanisms and Routes of Microplastics in Aquatic Environments and a Timeline for Their Fate and Occurrence (Past, Present, and Future). Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplastics 2024, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, H.; Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, A.; Ivanovich Vatin, N.; Mohamed, A.M.; Deifalla, A.F.; Mehmood, I. Plastic Waste Management Strategies and Their Environmental Aspects: A Scientometric Analysis and Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhao, T.; Miao, J.; Kong, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, M.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W. Evaluation framework for bitumen-aggregate interfacial adhesion incorporating pull-off test and fluorescence tracing method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 451, 138773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Leng, Z.; Lan, J.; Wang, W.; Yu, J.; Bai, Y.; Sreeram, A.; Hu, J. Sustainable Practice in Pavement Engineering through Value-Added Collective Recycling of Waste Plastic and Waste Tyre Rubber. Engineering 2021, 7, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, M. Waste Management Won’t Solve the Plastics Problem—We Need to Cut Consumption. Nature 2024, 633, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S. Three Ways to Solve the Plastics Pollution Crisis. Nature 2023, 616, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.A. 4 Ways Pakistan Is Tackling Plastic Waste and Pollution; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Junaid, M.; Jiang, C.; Eltwati, A.; Khan, D.; Alamri, M.; Eisa, M.S. Statistical analysis of low-density and high-density polyethylene modified asphalt mixes using the response surface method. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.; Khan, M.I.; Saleem, M.U. Performance Evaluation of Asphalt Modified with Municipal Wastes for Sustainable Pavement Construction. Sustainability 2016, 8, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowska-Baryła, I.; Bernat, K.; Zaborowska, M. Plastic Waste Degradation in Landfill Conditions: The Problem with Microplastics, and Their Direct and Indirect Environmental Effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pforzheimer, A.; Truelove, A. Trash in America; Frontier Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Center, J.E.S. Solid Waste Management and Recycling Technology of Japan–Toward a Sustainable Society; Ministry of the Environment: Tokyo, Japan, 2012.

- Brown, A.; Börkey, P. Plastics Recycled Content Requirements; OECD Environment Working Papers; OECD: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Sha, A.; Jiang, W.; Lu, Q.; Du, P.; Hu, K.; Li, C. Eco-friendly bismuth vanadate/iron oxide yellow composite heat-reflective coating for sustainable pavement: Urban heat island mitigation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 140645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasileiro, L.; Moreno-Navarro, F.; Tauste-Martínez, R.; Matos, J.; Rubio-Gámez, M.d.C. Reclaimed Polymers as Asphalt Binder Modifiers for More Sustainable Roads: A Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.; Mataraarachchi, S. A Review of Landfills, Waste and the Nearly Forgotten Nexus with Climate Change. Environments 2021, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukowski, A.; Olejniczak, J.I. Fractionation of Cadmium, Lead and Copper in Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Bottom Ash. J. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 21, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatachalam, V.; Spierling, S.; Endres, H.-J. Recyclable, but Not Recycled—An Indicator to Quantify the Environmental Impacts of Plastic Waste Disposal. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1316530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, N.F.A.; Foggo, A.; Thompson, R.C. Characterising the Deterioration of Different Plastics in Air and Seawater. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 141, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, B.; Chen, Z.; Zhong, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Hu, W. Atmospheric Phthalate Pollution in Plastic Agricultural Greenhouses in Shaanxi Province, China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 269, 116096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Aziz, S.; Rashid, R.M.; Baig, A.U. Overview of Pakistan’s Transportation Infrastructure from Future Perspective: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Appl. Res. Multidiscip. Stud. 2023, 4, 2–26. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.M. Infrastructure Development and Public-Private Partnership: Measuring Impacts of Urban Transport Infrastructure in Pakistan; ADBI Working Paper Series; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, J. Pakistan: Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Corridor Development Investment Program; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong City, Philippines, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook; Central Intelligence Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Nazir, E.; Nadeem, F.; Véronneau, S. Road Safety Challenges in Pakistan: An Overview. J. Transp. Secur. 2016, 9, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Che, T.; Mohseni, A.; Azari, H.; Heiden, P.A.; You, Z. Preliminary Study of Modified Asphalt Binders with Thermoplastics: The Rheology Properties and Interfacial Adhesion between Thermoplastics and Asphalt Binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 301, 124373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Peng, L.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, Q.; Li, X. Study on Viscoelastic Properties of Various Fiber-Reinforced Asphalt Binders. Materials 2024, 17, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Bai, Y. Viscoelastic Properties of Asphalt Mixtures with Different Modifiers at Different Temperatures Based on Static Creep Tests. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tan, G.; Liang, C.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y. Study on Viscoelastic Properties of Asphalt Mixtures Incorporating SBS Polymer and Basalt Fiber under Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Polymers 2020, 12, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safaeldeen, G.I.; Al-Mansob, R.A.; Al-Sabaeei, A.M.; Yusoff, N.I.M.; Ismail, A.; Tey, W.Y.; Azahar, W.N.A.W.; Ibrahim, A.N.H.; Jassam, T.M. Investigating the Mechanical Properties and Durability of Asphalt Mixture Modified with Epoxidized Natural Rubber (ENR) under Short and Long-Term Aging Conditions. Polymers 2022, 14, 4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaled, T.T.; Kareem, A.I.; Mohamad, S.A.; Al-Hamd, R.K.S.; Minto, A. The Performance of Modified Asphalt Mixtures with Different Lengths of Glass Fiber. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, A.A.; Farag, R.K.; Kandil, U.F.; El-Shafie, M.; Saleh, A.M.M.; El-Kafrawy, A.F. Thermo-Mechanical Properties Improvement of Asphalt Binder by Using Methylmethacrylate/Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, J.N.; Alzeebaree, R.; Hussein, N.A. Using Polymers to Improve Asphalt Pavement Performance, A Review. Proc. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 2944, 020021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, K. Using Waste Plastics as Asphalt Modifier: A Review. Materials 2021, 15, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.-F.; Lin, Q.-B.; Su, Q.-Z.; Zhong, H.-N.; Nerin, C. Identification of Recycled Polyethylene and Virgin Polyethylene Based on Untargeted Migrants. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 30, 100762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Meng, X.; You, Z. Laboratory Evaluation on Comprehensive Performance of Polyurethane Rubber Particle Mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaan, N.; Chegenizadeh, A.; Nikraz, H. Laboratory Properties of Waste PET Plastic-Modified Asphalt Mixes. Recycling 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Birgisson, B.; Kringos, N. Polymer Modification of Bitumen: Advances and Challenges. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 54, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaan, N.S.; Chegenizadeh, A.; Nikraz, H.; Rezagholilou, A. Investigating the Engineering Properties of Asphalt Binder Modified with Waste Plastic Polymer. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 1569–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joohari, I.B.; Giustozzi, F. Chemical and High-Temperature Rheological Properties of Recycled Plastics-Polymer Modified Hybrid Bitumen. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 123064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.M.B.; Silva, H.M.R.D.; Oliveira, J.R.M.; Fernandes, S.R.M. Incorporation of Waste Plastic in Asphalt Binders to Improve Their Performance in the Pavement. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2013, 6, 457. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, S.; White, G.; Verstraten, L. Principles for Incorporating Recycled Materials into Airport Pavement Construction for More Sustainable Airport Pavements. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7611; Standard Practice for Coding Plastic Manufactured Articles for Resin Identification. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Kibria, M.G.; Masuk, N.I.; Safayet, R.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Mourshed, M. Plastic Waste: Challenges and Opportunities to Mitigate Pollution and Effective Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2023, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacovelli, C. Single-Use Plastics: A Roadmap for Sustainability; International Environmental Technology Centre: Osaka, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hınıslıoğlu, S.; Ağar, E. Use of Waste High Density Polyethylene as Bitumen Modifier in Asphalt Concrete Mix. Mater. Lett. 2004, 58, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, M.N.; Aziz, M.A.A.; Jamin, N.F.M.; Salehan, N.A.M. Modification of Bitumen Using Polyacrylic Wig Waste. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1930, 020051. [Google Scholar]

- Behl, A.; Sharma, G.; Kumar, G. A Sustainable Approach: Utilization of Waste PVC in Asphalting of Roads. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 54, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariadi, D.; Saleh, S.M.; Yamin, R.A.; Aprilia, S. Utilization of LDPE Plastic Waste on the Quality of Pyrolysis Oil as an Asphalt Solvent Alternative. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2021, 23, 100872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Goad, M.A. Waste Polyvinyl Chloride-modified Bitumen. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 101, 1501–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Cortavitarte, M.; Lastra-González, P.; Calzada-Pérez, M.Á.; Indacoechea-Vega, I. Analysis of the Influence of Using Recycled Polystyrene as a Substitute for Bitumen in the Behaviour of Asphalt Concrete Mixtures. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, S.A.; Meyer, D.E.; Edelen, A.N.; Ingwersen, W.W.; Abraham, J.P.; Barrett, W.M.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Randall, P.M.; Ruiz-Mercado, G.; Smith, R.L. Mining Available Data from the United States Environmental Protection Agency to Support Rapid Life Cycle Inventory Modeling of Chemical Manufacturing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 9013–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrington, A. Recycling of Plastics. In Applied Plastics Engineering Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 191–217. [Google Scholar]

- Ashish, P.K.; Sreeram, A.; Xu, X.; Chandrasekar, P.; Jagadeesh, A.; Adwani, D.; Padhan, R.K. Closing the Loop: Harnessing Waste Plastics for Sustainable Asphalt Mixtures—A Comprehensive Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameur, A.B.; Valentin, J.; Baldo, N. A Review on the Use of Plastic Waste as a Modifier of Asphalt Mixtures for Road Constructions. CivilEng 2025, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadri, A.A.; Partal, P.; Ahmad, N.; Grenfell, J.; Airey, G. Chemically Modified Bitumens with Enhanced Rheology and Adhesion Properties to Siliceous Aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmedzade, P.; Demirelli, K.; Günay, T.; Biryan, F.; Alqudah, O. Effects of Waste Polypropylene Additive on the Properties of Bituminous Binder. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 2, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdul Wahhab, H.I.; Dalhat, M.A.; Habib, M.A. Storage Stability and High-Temperature Performance of Asphalt Binder Modified with Recycled Plastic. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2017, 18, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.A.; Vargas, M.A.; Sánchez-Sólis, A.; Manero, O. Asphalt/Polyethylene Blends: Rheological Properties, Microstructure and Viscosity Modeling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 45, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Capitão, S.; Bandeira, R.; Fonseca, M.; Picado-Santos, L. Performance of AC Mixtures Containing Flakes of LDPE Plastic Film Collected from Urban Waste Considering Ageing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 232, 117253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghuzlan, K.A.; Al-Khateeb, G.G.; Qasem, Y. Rheological Properties of Polyethylene-Modified Asphalt Binder. Athens J. Technol. Eng. 2013, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar, Z.N.; Karim, M.R.; Mahrez, A. A Review of Using Waste and Virgin Polymer in Pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 33, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Long, Z.; You, Z.; Ge, D.; Yang, X.; Xu, F.; Hashemi, M.; Diab, A. Review of Recycling Waste Plastics in Asphalt Paving Materials. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2022, 9, 742–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D6155; Standard Specification for Nontraditional Coarse Aggregates for Bituminous Paving Mixtures. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- AASHTO TP 129; Standard Method of Test for Determining the Rheological Properties of Asphalt Binder Using a Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Ge, D.; Yan, K.; You, Z.; Xu, H. Modification Mechanism of Asphalt Binder with Waste Tire Rubber and Recycled Polyethylene. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 126, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Guo, D.; Yu, R.; Zhang, M. Preparation, Characterization and Hot Storage Stability of Asphalt Modified by Waste Polyethylene Packaging. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.; Ferreira, A.; Almeida, A.; Santos, J. Incorporation of Plastic Waste into Road Pavements: A Systematic Literature Review on the Fatigue and Rutting Performances. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 407, 133441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.M.; Yousaf, J.; Khalid, U.; Li, H.; Yee, J.-J.; Naqvi, S.A.Z. Plastic Roads: Asphalt Mix Design and Performance. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennert, T.; Haas, E.; Ericson, C.; Wass, E., Jr.; Tulanowski, D.; Cytowicz, N. Impact of Recycled Plastic on Asphalt Binder and Mixture Performance; Rutgers University, Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Angelone, S.; Martinez, F.; Cauhape Casaux, M. A Comparative Study of Bituminous Mixtures with Recycled Polyethylene Added by Dry and Wet Processes. In Proceedings of the 8th RILEM International Symposium on Testing and Characterization of Sustainable and Innovative Bituminous Materials, Ancona, Italy, 7–9 October 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 583–594. [Google Scholar]

- Dalhat, M.A.; Al-Abdul Wahhab, H.I. Performance of Recycled Plastic Waste Modified Asphalt Binder in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2017, 18, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Ahmed, I.; Islam, M.A.; Ahsan, Z.; Saha, S. Recent Developments and Diverse Applications of High Melting Point Materials. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsch, J.; Piringer, O. Characteristics of Plastic Materials. In Plastic Packaging Materials for Food: Barrier Function, Mass Transport, Quality Assurance, and Legislation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 9–45. [Google Scholar]

- Buncher, M. Learning More About Recycled Plastics in Asphalt Pavements. Asph. Mag. 2021, 36, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, R.; Raja, R.M. Effectiveness Evaluation of Shredded Waste Expanded Polystyrene on the Properties of Binder and Asphalt Concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 7429188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadinia, E.; Zargar, M.; Karim, M.R.; Abdelaziz, M.; Ahmadinia, E. Performance Evaluation of Utilization of Waste Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) in Stone Mastic Asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, T.B.; Karim, M.R.; Syammaun, T. Dynamic Properties of Stone Mastic Asphalt Mixtures Containing Waste Plastic Bottles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 34, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Liu, P.; Yu, R.; Liu, X. Preparation Process to Affect Stability in Waste Polyethylene-Modified Bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 54, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadidy, A.-R.I. Evaluation of Pyrolisis Polypropylene Modified Asphalt Paving Materials. Al-Rafidain Eng. J. 2006, 14, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zoorob, S.E.; Suparma, L.B. Laboratory Design and Investigation of the Properties of Continuously Graded Asphaltic Concrete Containing Recycled Plastics Aggregate Replacement (Plastiphalt). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2000, 22, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadidy, A.I.; Yi-qiu, T. Effect of Polyethylene on Life of Flexible Pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movilla-Quesada, D.; Raposeiras, A.C.; Silva-Klein, L.T.; Lastra-González, P.; Castro-Fresno, D. Use of Plastic Scrap in Asphalt Mixtures Added by Dry Method as a Partial Substitute for Bitumen. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F.; Rubio, M.C.; Martinez-Echevarria, M.J. Analysis of Digestion Time and the Crumb Rubber Percentage in Dry-Process Crumb Rubber Modified Hot Bituminous Mixes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 2323–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muringayil Joseph, T.; Azat, S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Moini Jazani, O.; Esmaeili, A.; Kianfar, E.; Haponiuk, J.; Thomas, S. Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Recycling: A Review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyathiar, P.; Kumar, P.; Carpenter, G.; Brace, J.; Mishra, D.K. Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Bottle-to-Bottle Recycling for the Beverage Industry: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, P.J.; Al-Qadi, I.L. Pre-and Post-Peak Toughening Behaviours of Fibre-Reinforced Hot-Mix Asphalt Mixtures. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2014, 15, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, S.; Tsusaka, T.W. Assessing the Selection of PET Recycling Options in Japan: Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 4761–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Ganjidoust, H.; Maghanaki, A.A. Use of Plastic Waste (Poly-Ethylene Terephthalate) in Asphalt Concrete Mixture as Aggregate Replacement. Waste Manag. Res. 2005, 23, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.S.; Ahmad, S.A. The Impact of Polyethylene Terephthalate Waste on Different Bituminous Designs. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2022, 69, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziari, H.; Nasiri, E.; Amini, A.; Ferdosian, O. The Effect of EAF Dust and Waste PVC on Moisture Sensitivity, Rutting Resistance, and Fatigue Performance of Asphalt Binders and Mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 203, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, S. Modification of Waterproofing Asphalt by PVC Packaging Waste. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2009, 15, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köfteci, S.; Ahmedzade, P.; Kultayev, B. Performance Evaluation of Bitumen Modified by Various Types of Waste Plastics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 73, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalhat, M.A.; Al-Abdul Wahhab, H.I.; Al-Adham, K. Recycled Plastic Waste Asphalt Concrete via Mineral Aggregate Substitution and Binder Modification. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2019, 31, 04019134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghaee Moghaddam, T.; Soltani, M.; Karim, M.R. Evaluation of Permanent Deformation Characteristics of Unmodified and Polyethylene Terephthalate Modified Asphalt Mixtures Using Dynamic Creep Test. Mater. Des. 2014, 53, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, M.; Nasr, D. Properties of Asphalt Modified with Devulcanized Polyethylene Terephthalate. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2016, 34, 1424–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, S.; Haji Seyed Javadi, N.; Bayat, H.; Hajimohammadi, A. Assessment of Binder Modification in Dry-Added Waste Plastic Modified Asphalt. Polymers 2024, 16, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandramouli, K.; Satyaveni, A.; Subash, C.G. Plastic Waste: It’s Use in Construction of Roads. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Eng. 2016, 5, 290–295. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, A.; Rehman, M.A.U. A Mini-Review on the Use of Plastic Waste as a Modifier of the Bituminous Mix for Flexible Pavement. Clean. Mater. 2022, 4, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, P.K.; Pandey, S.P. Utilization of Plastics in Road Construction. Int. J. Adv. Res. Innov. Ideas Educ. 2016, 2, 1440–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, S.; Hafeez, I.; Ullah, R. Sustainable Use of Waste Plastic Modifiers to Strengthen the Adhesion Properties of Asphalt Mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 235, 117496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manju, R.; Sathya, S.; Sheema, K. Use of Plastic Waste in Bituminous Pavement. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2017, 10, 804–811. [Google Scholar]

- Goli, A.; Rout, B.; Cyril, T.; Govindaraj, V. Evaluation of Mechanical Characteristics and Plastic Coating Efficiency in Plastic-Modified Asphalt Mixes. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2023, 16, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Sun, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Hu, Y.; Temitope, A.A. Analysis of the Influence of Production Method, Plastic Content on the Basic Performance of Waste Plastic Modified Asphalt. Polymers 2022, 14, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, A.; Zamare, G.; Renge, V.C.; Tayde, S.; Bharsakale, G. An Overview on Waste Plastic Utilization in Asphalting of Roads. J. Eng. Res. Stud. 2012, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y. Performance Study of Waste PE-Modified High-Grade Asphalt. Polymers 2023, 15, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, X.; Polaczyk, P.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, M.; Huang, B. The Utilization of Waste Plastics in Asphalt Pavements: A Review. Clean. Mater. 2021, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Fan, W.; Ren, F.; Lv, X.; Xing, B. Influence of Polyphosphoric Acid (PPA) on Properties of Crumb Rubber (CR) Modified Asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 117094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.T.; Shahid, M.A.; Mahmud, N.; Habib, A.; Rana, M.M.; Khan, S.A.; Hossain, M.D. Research and Application of Polypropylene: A Review. Discov. Nano 2024, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddah, H.A. Polypropylene as a Promising Plastic: A Review. Am. J. Polym. Sci. 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, Z.; Padhan, R.K.; Sreeram, A. Production of a Sustainable Paving Material through Chemical Recycling of Waste PET into Crumb Rubber Modified Asphalt. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.K.; Vikranth, J. A Study on Use of Plastic Waste (Polypropylene) in Flexible Pavements. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Res. 2017, 7, 554–560. [Google Scholar]

- Sangiorgi, C.; Eskandarsefat, S.; Tataranni, P.; Simone, A.; Vignali, V.; Lantieri, C.; Dondi, G. A Complete Laboratory Assessment of Crumb Rubber Porous Asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 132, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, L. Influences of Interface Properties on the Performance of Fiber-Reinforced Asphalt Binder. Polymers 2019, 11, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takaikaew, T.; Tepsriha, P.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Hoy, M.; Kaloush, K.E.; Arulrajah, A. Performance of Fiber-Reinforced Asphalt Concretes with Various Asphalt Binders in Thailand. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.X.; Chang, C.L.; Yang, H.R. Comparing Tests on Water Relating Stability of Polyester and Polyacrylonitrile Fiber Reinforced Asphalt Mixture. Adv. Mat. Res. 2011, 287, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarres, A.; Hamedi, H. Effect of Waste Plastic Bottles on the Stiffness and Fatigue Properties of Modified Asphalt Mixes. Mater. Des. 2014, 61, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.-D.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, K.W. Laboratory Evaluation of Flexible Pavement Materials Containing Waste Polyethylene (WPE) Film. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 1890–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.; Yaghoubi, E.; Wong, Y.C.; Horpibulsuk, S. Recycled Plastic Granules and Demolition Wastes as Construction Materials: Resilient Moduli and Strength Characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 147, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C136-06; Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2006.

- Li, J.; Uhlmeyer, J.S.; Mahoney, J.P.; Muench, S.T. Updating the Pavement Design Catalog for the Washington State Department of Transportation: Using 1993 AASHTO Guide, Mechanistic–Empirical Pavement Design Guide, and Historical Performance. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2154, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Sun, D.; Cheng, L.; Pang, C. Composition and Degradation of Turbine Oil Sludge. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 125, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultrone, G.; Sebastián, E. Fly Ash Addition in Clayey Materials to Improve the Quality of Solid Bricks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelalochana, V.D.; Scardi, P.; Ataollahi, N. Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Waste in Electrochemical Applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, M.T.; Shbeeb, L. The Use of Polyethylene in Hot Asphalt Mixtures. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2007, 4, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, M.B.; Qureshi, N.A.; Hussain, A.; Iqbal, M.J. Enhancement of Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA) Properties Using Waste Polymers. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2019, 44, 8239–8248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastra-González, P.; Calzada-Pérez, M.A.; Castro-Fresno, D.; Vega-Zamanillo, Á.; Indacoechea-Vega, I. Comparative Analysis of the Performance of Asphalt Concretes Modified by Dry Way with Polymeric Waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 112, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, R.; Khan, M.A.; Sami, O.B.; Yadav, P.K.; Srivastava, P.K. A Study on the Plastic Waste Treatment Methods for Road Construction. Int. J. Adv. Res. Ideas Innov. Technol. 2017, 3, 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, A.; Haverkamp, R.G.; Robertson, T.; Bryant, J.; Bearsley, S. Studies of the Microstructure of Polymer-modified Bitumen Emulsions Using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy. J. Microsc. 2001, 204, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polacco, G.; Filippi, S.; Merusi, F.; Stastna, G. A Review of the Fundamentals of Polymer-Modified Asphalts: Asphalt/Polymer Interactions and Principles of Compatibility. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 224, 72–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.; Li, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X. Combined Modification of Asphalt by Waste PE and Rubber. Polym. Compos. 2008, 29, 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Li, T.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, D. Modification of Asphalt by Packaging Waste-polyethylene. Polym. Compos. 2008, 29, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yunusa, M.; Yan, B.; Zhang, X.; Chang, X. Micro-Morphologies of SBS Modifier at Mortar Transition Zone in Asphalt Mixture with Thin Sections and Fluorescence Analysis. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2021, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, H.; Liang, P.; Chai, C.; Yan, C.; Zhou, S. Investigation on Preparation Method of SBS-Modified Asphalt Based on MSCR, LAS, and Fluorescence Microscopy. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.S.; FAREED, M. Characterization of Bitumen Mixed with Plastic Waste. Int. J. Transp. Eng. 2015, 3, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Z.; Guo, N.; Tang, X.; Ding, Y.; You, L.; Xu, F. Microstructural Evolution of Asphalt Induced by Chloride Salt Erosion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 343, 128056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Shen, F.; Ding, Q. Micromechanism of the Dispersion Behavior of Polymer-Modified Rejuvenators in Aged Asphalt Material. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AASHTO T283; Standard Method of Test for Resistance of Compacted Asphalt Mixtures to Moisture-Induced Damage (T283-14). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO): Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Ullah, S.; Raheel, M.; Khan, R.; Khan, M.T. Characterization of Physical & Mechanical Properties of Asphalt Concrete Containing Low-& High-Density Polyethylene Waste as Aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 301, 124127. [Google Scholar]

- Padhan, R.K.; Leng, Z.; Sreeram, A.; Xu, X. Compound Modification of Asphalt with Styrene-Butadiene-Styrene and Waste Polyethylene Terephthalate Functionalized Additives. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, U.; Zamin, B.; Tariq Bashir, M.; Ahmad, M.; Sabri, M.M.S.; Keawsawasvong, S. Comprehensive Study on the Performance of Waste HDPE and LDPE Modified Asphalt Binders for Construction of Asphalt Pavements Application. Polymers 2022, 14, 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Cao, D.; Zhang, Y.; He, M. Effect of Linear Low Density-Polyethylene Grafted with Maleic Anhydride (LLDPE-g-MAH) on Properties of High Density-Polyethylene/Styrene–Butadiene–Styrene (HDPE/SBS) Modified Asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, K.; Tan, S.; Van Seters, T.; Henderson, V.; Passeport, E.; Drake, J. Pavement Wear Generates Microplastics in StormwaterRunoff. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 481, 136495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, G.; He, M.; Lim, S.M.; Ong, G.P.; Zulkati, A.; Kapilan, S. Recycling of Plastic Waste in Porous Asphalt Pavement: Engineering, Environmental, and Economic Implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 140865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Majhi, D.; Roy, T.K.; Chanda, D. Moisture Damage Analysis of Bituminous Mix by Durability Index Utilizing Waste Plastic Cup. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lü, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Shao, L.; Ye, J.; He, P. Is Incineration the Terminator of Plastics and Microplastics? J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Audén, C.; Sandoval, J.A.; Jerez, A.; Navarro, F.J.; Martínez-Boza, F.J.; Partal, P.; Gallegos, C. Evaluation of Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Polyethylene Modified Bitumen. Polym. Test. 2008, 27, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Xin, X.; Fan, W.; Wang, H.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Z. Phase Behavior and Hot Storage Characteristics of Asphalt Modified with Various Polyethylene: Experimental and Numerical Characterizations. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 203, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Jing, H.; Zhang, X.; Shi, W.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, L.; Wang, X.; Hoff, I. Sustainable Utilization of Recycled Waste in High-Viscosity Asphalt Binders: Case for Improvement in Aging Resistance. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, M.R.; Mikhailenko, P.; Piao, Z.; Bueno, M.; Poulikakos, L. Analysis of Waste Polyethylene (PE) and Its by-Products in Asphalt Binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 280, 122492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyshyev, S.; Korchak, B.; Miroshnichenko, D.; Lebedev, V.; Yasinska, A.; Lypko, Y. Obtaining New Materials from Liquid Pyrolysis Products of Used Tires for Waste Valorization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhotnikova, E.S.; Ganeeva, Y.M.; Frolov, I.N.; Firsin, A.A.; Yusupova, T.N. Assessing the Structure of Recycled Polyethylene-Modified Bitumen Using the Calorimetry Method. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 138, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.I.; Newbury, D.E.; Michael, J.R.; Ritchie, N.W.M.; Scott, J.H.J.; Joy, D.C. Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; ISBN 1493966766. [Google Scholar]

- Oreto, C.; Russo, F.; Veropalumbo, R.; Viscione, N.; Biancardo, S.A.; Dell’Acqua, G. Life Cycle Assessment of Sustainable Asphalt Pavement Solutions Involving Recycled Aggregates and Polymers. Materials 2021, 14, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, M.; Ahmed, R.; Ali, A.W.; Lee, S.-J. SEM and ESEM Techniques Used for Analysis of Asphalt Binder and Mixture: A State of the Art Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 186, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, Y.; Guangxun, E.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Ren, J.; Lin, Z. Recycling of Waste Polyethylene in Asphalt and Its Performance Enhancement Methods: A Critical Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 451, 142072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jew, P.; Shimizu, J.A.; Svazic, M.; Woodhams, R.T. Polyethlene-modified Bitumen for Paving Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1986, 31, 2685–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, P.; Nien, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, W.; Chen, J. Thermal and Rheological Properties of Maleated Polypropylene Modified Asphalt. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2005, 45, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.M.; Kabir, S.; Alhussain, M.A.; Almansoor, F.F. Asphalt Design Using Recycled Plastic and Crumb-Rubber Waste for Sustainable Pavement Construction. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Jiao, L.; Ni, F.; Yang, J. Evaluation of Plastic–Rubber Asphalt: Engineering Property and Environmental Concern. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 71, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, V.; Manthos, E.; Mantalovas, K.; Di Mino, G. Multi-Recyclability of Asphalt Mixtures Modified with Recycled Plastic: Towards a Circular Economy. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, M.; Mohamed Rehan, K. Rheological Evaluation of Bituminous Binder Modified with Waste Plastic Material. In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Hydrocarbons & Chemistry (ISHC5), Algiers, Algeria, 23–25 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Garg, R. Rheology of Waste Plastic Fibre-Modified Bitumen. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2011, 12, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, Z.O.G.; Shaver, M.P. Mechanical Recycling of Packaging Plastics: A Review. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42, 2000415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhan, R.K.; Mohanta, C.; Sreeram, A.; Gupta, A. Rheological Evaluation of Bitumen Modified Using Antistripping Additives Synthesised from Waste Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET). Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2020, 21, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Hu, C.; Adhikari, S.; Wu, C.; Yu, M. Evaluation of Waste Express Bag as a Novel Bitumen Modifier. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Zhang, N.; Lv, S.; Cabrera, M.B.; Yuan, J.; Fan, X.; Liu, H. Correlation Analysis of Chemical Components and Rheological Properties of Asphalt after Aging and Rejuvenation. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04022303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, L.; Yuxia, Z.; Yuzhen, Z. The Research of GMA-g-LDPE Modified Qinhuangdao Bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmedzade, P.; Fainleib, A.; Günay, T.; Starostenko, O.; Kovalinska, T. Effect of Gamma-Irradiated Recycled Low-Density Polyethylene on the High-and Low-Temperature Properties of Bitumen. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2013, 2013, 141298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gao, S.; He, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhuang, R.; Zeng, S.; Yu, J. Effect of aging on structure and properties of self-healing-enhanced SBS modified asphalt with dual dynamic chemical bonds. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouali, M.; Ghorbel, E.; Derriche, Z. Phase Separation and Thermal Degradation of Plastic Bag Waste Modified Bitumen during High Temperature Storage. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 239, 117872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R.; Yin, F.; Moraes, R. Recycled Plastics in Asphalt Part A: State of the Knowledge; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, T.; Zhou, L.; Xu, J.; Qin, Y.; Chen, W.; Dai, J. Rheology and Thermal Stability of Polymer Modified Bitumen with Coexistence of Amorphous Phase and Crystalline Phase. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 178, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Montalvo, L. Repurposing Waste Plastics into Cleaner Asphalt Pavement Materials: A Critical Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.K.; Gao, Y.; Almansour, A.I. Rheological and Microstructural Characterization of Novel High-Elasticity Polymer Modifiers in Asphalt Binders. Polymers 2025, 17, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberge, M.; Prud’homme, R.E.; Brisson, J. Molecular Modelling of the Uniaxial Deformation of Amorphous Polyethylene Terephthalate. Polymer 2004, 45, 1401–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xie, Y. Crumb Tire Rubber Polyolefin Elastomer Modified Asphalt with Hot Storage Stability. Prog. Rubber Plast. Recycl. Technol. 2016, 32, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Sun, G.; Zhu, X.; Ye, F.; Xu, J. Intrinsic Temperature Sensitive Self-Healing Character of Asphalt Binders Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Fuel 2018, 211, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Tang, X.; Ding, Y.; Miljković, M.; Khanal, A.; Ma, W.; You, L.; Xu, F. Influence of Sea Salt on the Interfacial Adhesion of Bitumen–Aggregate Systems by Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 336, 127471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, G.; Lv, S.; Gao, J.; Kowalski, K.J.; Valentin, J.; Alexiadis, A. Self-Healing Behavior of Asphalt System Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 254, 119225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wang, H. Molecular Dynamics Study of Oxidative Aging Effect on Asphalt Binder Properties. Fuel 2017, 188, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Liu, Q.; Guo, M.; Wang, D.; Oeser, M. Study on the Effect of Aging on Physical Properties of Asphalt Binder from a Microscale Perspective. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 187, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Roy, T.K. Effect of Waste Plastic and Waste Tires Ash on Mechanical Behavior of Bitumen. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2016, 28, 04016006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Crucho, J.; Abreu, C.; Picado-Santos, L. An Assessment of Moisture Susceptibility and Ageing Effect on Nanoclay-Modified Ac Mixtures Containing Flakes of Plastic Film Collected as Urban Waste. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špaček, P.; Hegr, Z.; Beneš, J. Practical Experiences with New Types of Highly Modified Asphalt Binders. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 236, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Hu, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y. Comparative Study of Asphalts Modified by Packaging Waste EPS and Waste PE. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2011, 50, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhotnikova, E.S.; Frolov, I.N.; Ganeeva, Y.M.; Firsin, A.A.; Yusupova, T.N. Rheological Behavior of Recycled Polyethylene Modified Bitumens. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2019, 37, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, C.J.; Brown, H.; Serrat, C. Case Study: Wet Processed Plastics in Asphalt. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 99th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 12–16 January 2020; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, H.; Hu, W.; Polaczyk, P.; Huang, B. Potential Alternative to Styrene–Butadiene–Styrene for Asphalt Modification Using Recycled Rubber–Plastic Blends. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Weng, Z.; Wu, D.; Du, Y. Aggregate-level 3D analysis of asphalt pavement deterioration using laser scanning and vision transformer. Autom. Constr. 2025, 178, 106380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.H. LCA of Plastic Waste Recovery into Recycled Materials, Energy and Fuels in Singapore. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Leng, Z.; Lan, J.; Chen, R.; Jiang, J. Environmental and Economic Assessment of Collective Recycling Waste Plastic and Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement into Pavement Construction: A Case Study in Hong Kong. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.M.; He, M.; Hao, G.; Ng, T.C.A.; Ong, G.P. Recyclability Potential of Waste Plastic-Modified Asphalt Concrete with Consideration to Its Environmental Impact. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 439, 137299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Pham, A.; Stasinopoulos, P.; Giustozzi, F. Recycling Waste Plastics in Roads: A Life-Cycle Assessment Study Using Primary Data. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lastra-González, P.; Lizasoain-Arteaga, E.; Castro-Fresno, D.; Flintsch, G. Analysis of Replacing Virgin Bitumen by Plastic Waste in Asphalt Concrete Mixtures. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2022, 23, 2621–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, A.P. Economics and Viability of Plastic Road: A Review. J. Curr. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 3, 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Keijzer, E.E.; Leegwater, G.A.; de Vos-Effting, S.E.; De Wit, M.S. Carbon Footprint Comparison of Innovative Techniques in the Construction and Maintenance of Road Infrastructure in The Netherlands. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 54, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojobi, A.O.; Nwobodo, S.E.; Aladegboye, O.J. Recycling of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Plastic Bottle Wastes in Bituminous Asphaltic Concrete. Cogent Eng. 2016, 3, 1133480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, R.; Sekar, A.R.C.; Sundarakannan, B.; Velkennedy, R. A Technique to Dispose Waste Plastics in an Ecofriendly Way–Application in Construction of Flexible Pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topsfield, J. Plastic and Glass Road That Could Help Solve Australia’s Waste Crisis. The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, S.; Khwaja, M.A. Plastic Waste Use in Road Construction: Viable Waste Management? Sustainable Development Policy Institute: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gul, S.; Ullah, Q.; Qasim, M. Bio-Waste Management Legislation Regulations and Policies: A Case Study of Pakistan. Pak. J. Int. Aff. 2022, 5, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A.; Farhan, A.; Ahmad, A.; Shah, S.K.; Khan, M. UTILIZATION OF WASTE PLASTIC AS A BINDER REPLACEMENT IN BITUMEN. J. Mech. Contin. Math. Sci. 2019, 14, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Karim, S.B.; Norman, S.; Koting, S.; Simarani, K.; Loo, S.-C.; Mohd Rahim, F.A.; Ibrahim, M.R.; Md Yusoff, N.I.; Nagor Mohamed, A.H. Plastic Roads in Asia: Current Implementations and Should It Be Considered? Materials 2023, 16, 5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, R.R.N.; Chandrasekhar, K.; Roy, P.; Khan, A. Challenges and Opportunities: Plastic Waste Management in India. 2018. Available online: http://www.teriin.org/sites/default/files/2018-06/plastic-waste-management_0.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Hossain, R.; Islam, M.T.; Shanker, R.; Khan, D.; Locock, K.E.S.; Ghose, A.; Schandl, H.; Dhodapkar, R.; Sahajwalla, V. Plastic Waste Management in India: Challenges, Opportunities, and Roadmap for Circular Economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, G.M.; Faxina, A.L. Asphalt Concrete Mixtures Modified with Polymeric Waste by the Wet and Dry Processes: A Literature Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 312, 125408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.; Crowe, M.R.; Najah, P.; Mellor, S. Quarterly Comment by Trinity Chambers: Newcastle, UK Alice Richardson, Matthew R Crowe, Parissa Najah, Shada Mellor. Environ. Law Rev. 2020, 22, 306–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.; Reid, G. Recycled Waste Plastic for Extending and Modifying Asphalt Binders. In Proceedings of the 8th Symposium on Pavement Surface Characteristics (SURF 2018), Brisbane, Australia, 2–4 May 2018; pp. 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bank, W. Plastic Waste Discharges from Rivers and Coastlines in Indonesia. In Plastic Waste Discharges from Rivers and Coastlines in Indonesia; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types | Density (g/cm3) | Melting Point (°C) | Source | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | 1.04–1.07 | 210–249 | Disposable food containers, takeout containers, compact disc cases, laboratory test tubes, packaging materials, CD storage cases. | Rigidity and strength, thermoplastic nature, wide availability | Brittleness at low temperatures, poor UV resistance, compatibility issues |

| PET | 1.16–1.58 | 250–260 | Plastic beverage bottles, food packaging materials, soft drink bottles, and water bottles. | High strength and stiffness, chemical resistance, high melting point | Poor compatibility with bitumen, brittleness, hydrophilic nature |

| PVC | 1.34–1.39 | 180–200 | Plumbing fittings, pipes, window framing, structural profiles, cable insulation, and garden hose. | Flame retardant, high hardness, and durability | Critical thermal degradation, poor compatibility, environmental and health hazard |

| PP | 0.90–0.91 | 145–165 | Drinking straws, furniture, packaging materials, plastic containers, piping systems, and automotive components. | Chemical resistance, toughness and impact resistance, high melting point | Susceptibility to UV degradation, low-temperature brittleness, poor UV resistance |

| LDPE | 0.91–0.94 | 110–125 | Plastic shopping bags, storage trays, food containers, agricultural films, and water bottles. | Excellent flexibility, chemical resistance, easy blending | Low rigidity, weak UV resistance |

| HDPE | 0.94–0.97 | 130–149 | Plastic bottle packaging, children’s toys, shampoo bottles, piping, and household items. | Durable, moisture resistance, recyclable | Reduced flexibility, compatibility, and homogeneity |

| Type | Physical Method | Material Composition | Size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET | Crushing | Particle | 0.45–1.18 mm | [58,59,60,61] |

| Extruding | Pellet | 0.45–1.18 mm | ||

| Grinding | Pieces | 0.45–0.50 mm | ||

| PVC | Pulverization | Powder form | 0.45–0.50 mm | [62] |

| Plastic | Effect on Bituminous Mixtures | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PP, PS | Bituminous mixtures with 10–15% waste plastic by weight (wb) showed no signs of stripping even after 72 h of water soaking. The aggregate impact value and the stability of the bituminous mixture (BM) both showed improvement. | [77] |

| LDPE, HDPE | A 2.3% increase in the tensile strength ratio (TSR) value was observed with the addition of 9% waste plastic by weight. An 8.2% increase in the tensile strength ratio (TSR) value was achieved with the addition of 9% waste plastic by weight. | [78] |

| PVC or HDPE pipes, plastic carry bags, disposable cups, and PET bottles. | The crushing value of plastic mix-coated aggregates was reduced by 40%, and the stability value of the bituminous mixture (BM) was improved with the addition of 10% waste plastic by weight. | [79] |

| Plastic | Effect on Bituminous Mixtures | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PP, PS | Softening point increased from 49.9 °C to 62–65 °C; penetration reduced by 30–35% | [91] |

| LDPE, HDPE | Softening point increased from 49.9 °C to 68 °C; penetration reduced by 41.8%; TSR increased by 11.7% | [92] |

| PVC and HDPE | The addition of 10% waste plastic by weight increased the softening point from 52 °C to 80 °C and reduced the penetration value from 79 mm to 67 mm | [93] |

| Symbol | Dry Method Processing Performance | Wet Method Processing Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| [96] | No stripping after 72 h soaking, ↑ impact resistance, ↑ mix stability | Not commonly used |

| [97,98] | Comparable Marshall stability at 5–15% aggregate replacement | ↑ Rutting and fatigue resistance (via glycolysis-modified PET) |

| [99] | ↑ Stiffness but ↓ low-temp cracking resistance; rarely used due to emissions | Reduced thermal susceptibility |

| [100] | No stripping after 72 h soaking, ↑ impact resistance | ↑ Softening point (49.9 → 68 °C), ↓ penetration by 41.8% |

| [101] | ↑ Marshall stability, ↑ moisture resistance (TSR 88–92%) | ↑ Rutting resistance (35–40%), ↑ stiffness, ↓ penetration |

| [102] | ↑ Marshall stability, improved moisture resistance | ↑ Softening point, ↓ penetration, ↑ rutting resistance, ↑ TSR (11.7%) |

| S. No | Technique | Plastic Types and Process | Key Findings | Region (Reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Scanning electron microscope (SEM) | LDPE (lubricant bottles), mixed plastics (Dry) | Both LDPE and HDPE aggregates reduced the density of asphalt mixture due to porous nature and increased air voids content. | Pakistan [113] |

| 2 | Scanning electron microscope (SEM) | Recycled polyethylene Terephthalate (Dry) | PET is uniformly dispersed within the asphalt binder matrix. | India [114] |

| 3 | Scanning electron microscope (SEM) | LDPE and HDPE sourced from bottles and bags at 0%, 2%, 4%, and 6% by weight of asphalt. | No microcracks could be observed on the surface of 6% HDPE-modified asphalt. | Russia [115] |

| 4 | Optical microscopy | The concentration of the linear low-density polyethylene grafted with maleic anhydride (LLDPE-g-MAH) was 0.13, 0.27, and 0.4 of asphalt weight. PET (milk bottles) | Small quantities of LDPE-g-MAH are incapable of forming a homogeneous system. | China [116] |

| 5 | Optical microscopy | PE/PP at 2%, 5%, and 10% by asphalt weight. (Dry) | Birefringent, fibrillar structures were observed in the 2% sample. In the 5% sample, insoluble, crystalline fibrils remained after extraction with CH2Cl2. | USA [117] |

| 6 | Optical microscopy | PE was added to asphalt in the range of 1 to 13 wt%, with a step size of 1–2%. | Separate particles of the polymer phase are distinguishable, while at high content, the polymer phase becomes harder to distinguish due to its greater integration into the asphalt. | Russia [118] |

| 7 | Optical microscopy | Waste plastic (PC) added at 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, and 4.5% of the asphalt’s weight. | A 2% PC concentration in the base asphalt exhibits a more uniform dispersion compared to higher proportions. With an increase in PC content, the bitumen becomes stiffer as the polymer chains expand. | India [119] |

| 8 | Optical microscopy | 4% HDPE by weight of asphalt. | The most effective way of decreasing the size of plastic particles in asphalt that will make them easier to disperse is pre-mixing with rubber. | USA [120] |

| 9 | Optical microscopy | Recycled polyethylene at 2%, 5%, 15%, and 25% by weight of asphalt. | At low content, RPE is evenly distributed throughout the continuous asphalt phase. At 15% content, the RPE phase is nearly continuous, with a larger dispersion area of the asphalt phase. | Spain [121] |

| 10 | Fluorescence microscopy (FM) | 5 wt.% of the PE/asphalt blends, HDPE, LDPE. | The percentages of larger polymer phase grew with the increase in time. | China [122] |

| 11 | Fluorescence microscopy (FM) | HDPE, medium density polyethylene and LDPE at 5% of the PE/asphalt mixtures. | The separation and development of the polyethylene phase are primarily caused by particle agglomeration, resulting in an increase in particle size. | China [123] |

| 12 | Fluorescence microscopy (FM) | (PE) from milk bags (3 mm granules) is added to asphalt in 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, and 10% by weight. | 2wt% polyethylene (PE), scattering spots are dispersed in the binder, while at 4, 6, and 8 wt%, the PE forms a filamentous structure and eventually a complete net-like structure. | China [124] |

| 13 | Environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM) | HDPE and LDPE plastic pellets at 5% by weight of asphalt. | High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) particles can generally be distinguished from the asphalt phase. LDPE-modified asphalt forms a typical binary blend, with distinct phases of asphalt | China [125] |

| 14 | Environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM) | PE pellets and PE shreds from packaging at 5% by weight. | PE particles exhibited a distinct, non-blended phase. Fibrils surrounding the particles indicated partial blending of PE with the binder. | Switzerland [126] |

| Features | Types | Major Finding | Region (Reference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermo-rheological performance | LDPE, HDPE | These polymer additives greatly enhanced asphalt’s rheological properties. Adding 10% (wt.) low-density polyethylene (LDPE) to asphalt achieves the optimal rutting resistance across various temperatures. | Saudi Arabia [139] |

| Thermo-rheological performance | PET | PET-based additives in crumb rubber-modified asphalt (CRMA) enhance rutting and fatigue resistance while increasing the rotational viscosity of the modified binders. The PET modifier enhances rutting resistance and reduces asphalt’s susceptibility to cracking and deformation at high temperatures. | Hong Kong, China [140] Australia [141] |

| Mechanical performance | Recycled polypropylene (PP) and rubber | Plastic–rubber asphalt (PRA) mixtures and styrene–butadiene–styrene (SBS) asphalt mixtures demonstrate similar performance in high-temperature stability, low-temperature flexibility, and water resistance. Plastic–rubber asphalt (PRA) is a promising material for enhancing various engineering properties of asphalt mixtures, offering significant improvements in performance and durability. | China [142] |

| Mechanical performance | Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) | High-density polyethylene with the wet mixing method offers superior adhesion properties. Modified Lottman and Hamburg wheel track tests outperform the Marshall stability test for assessing moisture damage. | Pakistan [143] |

| Types | Process | Rutting Resistance Increase (%) | Fatigue Life (%) | Moisture Resistance (%) | Region Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE | Wet/dry | 35 ± 7 | 18 ± 4 | 22 ± 5 | Warm climates |

| HDPE | Wet | 30 ± 6 | 15 ± 3 | 25 ± 6 | Hot regions |

| PP | Wet/dry | 32 ± 6 | 20 ± 5 | 24 ± 4 | Mixed climates |

| PET | Dry | 28 ± 5 | 25 ± 6 | 27 ± 4 | Tropical region |

| PVC | Wet | 26 ± 5 | 21 ± 4 | 35 ± 8 | Urban industrials zones |

| PS | Dry | 24 ± 5 | 16 ± 4 | 30 ± 7 | High-temperature environments |

| Types | GWP | CED | Landfill Diversion (KG) | AP (KG) | EP (KG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional asphalt | 85–95 | 1200–1350 | 0 | 1.8–2.2 | 0.4–0.6 |

| LDPE (6% wet) | 62–70 | 980–1100 | 60 | 1.4–1.7 | 0.3–0.5 |

| PET (10% dry) | 68–75 | 1050–1180 | 100 | 1.5–1.9 | 0.4–0.6 |

| PP (8% dry) | 70–78 | 1080–1200 | 80 | 1.6–1.8 | 0.35–0.55 |

| SBS (4.5% wet) | 105–115 | 1450–1600 | 0 | 2.5–2.8 | 0.7–0.9 |

| PVC (5% dry) | 75–85 | 1100–1250 | 50 | 3.0–3.5 | 0.8–1.1 |

| Landfilled Plastic 2016 | Weight% | Tons | Price/Ton $80 | Price/Ton $160 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 45 | 3,333,000 | 266,400,000 | 532,800,000 |

| PP | 19 | 1,406,000 | 112,480,000 | 224,960,000 |

| PS | 3 | 222,000 | 17,760,000 | 35,520,000 |

| PE/PP | 1 | 74,000 | 5,920,000 | 11,840,000 |

| PVC | 10 | 740,000 | - | - |

| PET | 3 | 222,000 | - | - |

| Rubber | 13 | 962,000 | - | - |

| Others | 6 | 444,000 | - | - |

| Total | 100 | 7,400,000 | 402,560,000 | 805,120,000 |

| Types | Bitumen Price ($/Ton) | Processing Cost ($/Ton) | Substitution Rate (%) | Life Extension (%) | LCC Savings ($) | LCC Savings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE | 350 | 50 | 5 | 10 | 13,391 | 7.96 |

| LDPE | 350 | 50 | 8 | 20 | 17,733 | 10.54 |

| HDPE | 350 | 75 | 10 | 15 | 13,891 | 8.26 |

| PP | 350 | 50 | 8 | 25 | 18,233 | 10.84 |

| PET | 350 | 75 | 11 | 25 | 18,733 | 11.14 |

| PVC | 350 | 150 | 5 | 10 | 12,891 | 7.66 |

| LDPE | 400 | 100 | 8 | 20 | 17,483 | 10.39 |

| HDPE | 400 | 75 | 10 | 15 | 14,891 | 8.85 |

| PP | 400 | 50 | 8 | 25 | 19,733 | 11.73 |

| PET | 400 | 75 | 11 | 25 | 19,983 | 11.88 |

| PVC | 400 | 150 | 5 | 10 | 13,141 | 7.81 |

| LDPE | 450 | 150 | 5 | 10 | 13,141 | 7.81 |

| HDPE | 450 | 75 | 10 | 15 | 15,391 | 9.15 |

| PP | 450 | 50 | 8 | 25 | 20,233 | 12.03 |

| PET | 450 | 75 | 11 | 25 | 20,733 | 12.33 |

| PVC | 450 | 150 | 5 | 10 | 12,891 | 7.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shah, S.K.; Gao, Y.; Abdelfatah, A. Plastic-Waste-Modified Asphalt for Sustainable Road Infrastructure: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219832

Shah SK, Gao Y, Abdelfatah A. Plastic-Waste-Modified Asphalt for Sustainable Road Infrastructure: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219832

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Syed Khaliq, Ying Gao, and Akmal Abdelfatah. 2025. "Plastic-Waste-Modified Asphalt for Sustainable Road Infrastructure: A Comprehensive Review" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219832

APA StyleShah, S. K., Gao, Y., & Abdelfatah, A. (2025). Plastic-Waste-Modified Asphalt for Sustainable Road Infrastructure: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability, 17(21), 9832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219832