Abstract

The polar regions face growing threats from climate change, making sustainable practices in polar cruise tourism essential. This study examines the role of marketing in promoting sustainability by analysing cruise operators’ websites (n = 50) and testing alternative advertising strategies. Survey findings (n = 790) highlight that well-crafted sustainability advertisements can reduce interest in close-up wildlife interactions, increase willingness to pay for conservation-focused trips, and promote the adoption of sustainable technologies in travel. Content analysis shows that award-winning operators emphasise conservation, sustainability, and community engagement through distinctive digital traits. While traditional adverts were preferred for their adventure focus, sustainability adverts resonated with those valuing education. This study provides valuable insights for operators, policymakers, and researchers dedicated to advancing sustainable tourism in the polar regions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Growth of Polar Cruise Tourism

The polar regions, renowned for their uniqueness and fragility [1,2,3], are increasingly threatened by anthropogenic climate change and global warming [3,4,5,6]. The polar amplification of global warming [7,8,9,10] has accelerated glacial retreat, ice shelf collapse, and sea ice loss, transforming these regions into last-chance tourism destinations [11,12,13,14] as travellers seek to experience them before irreversible changes occur.

Polar cruise tourism has seen substantial growth in visitor numbers and activities [15,16]. Google trend analysis from 2019 to 2022 shows a 51% increase in interest for Antarctica cruises and a 47% rise for Arctic cruises [17]. This growth is reflected in academic research, shifting from early descriptive studies to more complex analyses of management, regulation, and ecological impact. Initially, research focused on documenting polar tourism, but recent studies explore governance, ecological interactions, tourist motivations, and community perspectives [16,18,19].

The rapid expansion of polar tourism underscores the urgent need for sustainable practices to protect these vulnerable ecosystems and wildlife [6,11,20,21]. The combined impact of increasing tourist numbers and melting ice highlights the importance of sustainable tourism in both practical and academic contexts [6,22,23]. Balancing tourism development with the needs of local communities and wildlife is critical, with significant implications for governance and management strategies in polar cruise tourism [24,25].

1.2. Management and Sustainability

Managing polar cruise tourism requires effective strategies to mitigate its environmental and cultural impacts. In Antarctica, the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO) promotes safe and environmentally responsible tourism [26], providing guidelines for operators and participating in the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM). The Antarctic Treaty 1959 [27] designates Antarctica as a region for peace and science, ensuring responsible use. In the Arctic, the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators (AECO) plays a key role in sustainable tourism management, establishing guidelines for wildlife interaction, waste management, and community engagement to minimise environmental impact and protect cultural heritage [28]. Additionally, Arctic nations such as Iceland, Norway, and Canada implement country-specific regulations addressing environmental protection, indigenous rights, and resource management.

Cruise tourism presents significant environmental and social challenges [29,30,31]. Its impacts vary in permanence, intensity, and scale [16]. While economic benefits and increased environmental awareness through citizen science initiatives [20] can be positive, negative effects include habitat destruction, carbon emissions, pollution, wildlife disturbances, and biosecurity risks like disease transmission [32,33,34,35,36]. Research [31,37,38] highlights issues such as solid waste pollution, overcrowding, and the homogenisation of port experiences, as well as stress concerns over air emissions and wildlife interactions, advocating for integrated environmental and sociocultural strategies. The effects of human disturbances on wildlife and marine heritage [39,40,41,42] and local communities [43] further underscore the need for robust visitor guidelines.

Mitigating these impacts requires strategic tourism management, including education, interpretation, and planning, to reduce environmental harm and foster conservation awareness [23,26,44,45,46,47]. While some studies question whether polar cruise tourism enhances tourists’ pro-environmental attitudes [11], other research suggests that educational initiatives by operators can significantly improve environmental understanding and conservation behaviours [48]. Additionally, a growing number of tourists are seeking sustainable tourism experiences in polar regions [32], highlighting tourism’s potential to promote environmental stewardship in these fragile ecosystems. This is particularly relevant in the context of increasing social media use and the role of influencer marketing, word-of-mouth, and consumer-led dialogue within the broader marketing landscape [49].

1.3. The Importance of Branding and Marketing

Marketing and advertising shape popular culture, influencing how destinations like Antarctica are perceived. Throughout history, Antarctica has been framed through various narratives, including heroism, commerce, protection, peace, science, and transformation [50,51,52]. These narratives inform tourism marketing strategies. Early commodification focused on commercial products such as seal furs, whale blubber, and krill oil, exemplified by the 1895 “Antarctic Whalebone” brand [50]. In contrast, modern NGO marketing positions Antarctica as a place in need of protection, aligning with the Greening of Antarctica campaign. It is also depicted as a sanctuary for scientific research, reinforced by the Antarctic Treaty and National Antarctic Programs. Additionally, tourism advertising presents Antarctica as a destination for personal transformation and self-improvement [51]. These tourism imaginaries assign both intrinsic and economic value to destinations, shaping attraction efforts and influencing visitor perceptions [53]. Disseminated through print media, digital content, and video, these narratives impact tourism operations, behaviours, and local communities [54].

Digital media, particularly websites and social media platforms of polar tourism operators, play a crucial role in shaping tourism experiences, especially during pre-trip information-seeking [55,56]. Marketing and advertising significantly influence tourists’ perceptions and behaviours towards sustainable tourism [11,26]. While current marketing often emphasises Antarctica’s extreme conditions to appeal to adventure and transformation [57], it must also address managing visitor expectations and minimising environmental impacts [37,40]. Research highlights the need for visitor guidelines and innovative management strategies to reduce the human impact on wildlife and marine ecosystems [22,41]. In this context, marketing and communication serve as valuable management tools.

Sustainable tourism development requires marketing approaches that encourage responsible visitor behaviours [31,43]. A critical research area is the strategic use of pre-trip communication to shape visitor expectations and guide participation in sustainable activities [56,58]. Setting sustainable expectations can, in turn, influence business operations toward more environmentally responsible practices. This underscores the need to better understand consumer behaviour and purchasing decisions related to sustainability. Furthermore, marketing represents a key research avenue in exploring how strategic communication can drive demand for sustainable tourism [59].

1.4. Marketing Transformation

Antarctic travel is frequently marketed as a transformative experience, prominently featured in advertisements and branding that depict it as a place for self-discovery, personal growth, and journeys fostering environmental awareness [50,51,57]. These narratives, prevalent in tourism marketing, highlight Antarctica as a place where visitors can become “Antarctic Ambassadors,” advocating for conservation and sustainable practices [50,60]. However, while these marketing efforts aim to promote environmental stewardship and educate tourists about conservation issues, their actual impact on pro-environmental behaviours remains under-researched [22]. Understanding and leveraging these transformative narratives through effective marketing strategies could help sustainable practices in polar cruise tourism.

Technological advancements, such as high-definition cameras, extensive internet access, and instant sharing capabilities, have revolutionised the creation and dissemination of tourism media, including polar cruise tourism [56]. These technologies, embedded within global tourism practices, offer a rich area for research. As digital media becomes increasingly integral to global tourism, websites and social media have become vital platforms for promoting and facilitating consumer choices, especially in nature-based tourism ventures [61]. Understanding consumers’ decision-making processes is crucial for refining communication strategies that promote sustainable consumption [62,63]. Research on the application of marketing and advertising in polar cruise tourism, however, is scarce.

Building on evidence that advertising strongly shapes travellers’ provider choices [64], this research examines how polar cruise operators communicate sustainability on their websites. By analysing site content through a sustainability and conservation lens, the research addresses a clear gap in the literature and highlights the ethical and strategic stakes of advertising in fragile destinations such as Antarctica. It pairs a review of current sustainability marketing practices with tests of alternative advertising approaches to identify more effective strategies for encouraging sustainable polar cruise tourism and to inform both scholarship and industry practice. Specifically, this research addresses the following:

- Research gap

- There is little empirical work on how marketing and advertising are applied in polar cruise tourism and what they actually do to shape sustainable choices.

- Although “transformative” Antarctic marketing is common, its impact on pro-environmental behaviours remains under-researched.

- A critical missing piece is evidence on the strategic use of pre-trip communication to set expectations and guide participation in sustainable activities, linked to a better understanding of consumer decision-making around sustainability.

- Research goal

- The study aims to (1) audit operators’ websites for sustainability and conservation messaging and (2) develop and test advertising approaches with consumers to identify marketing strategies that encourage sustainable polar cruise tourism.

- Methodologically, it links a visual website content analysis to a controlled consumer experiment (constant imagery; copy varies; sustainability vs. adventure) measuring preferences, behavioural intentions, and willingness-to-pay (WTP).

- Research questions

- What sustainability and conservation elements do polar cruise operators present on their websites, and how are they integrated into marketing communications? (Website content analysis.)

- How does advertising copy that foregrounds sustainability (versus adventure) affect consumer preferences, behavioural intentions, and willingness-to-pay for polar cruises when imagery is held constant? (Consumer experiment.)

- Which messaging approach more effectively promotes sustainable polar cruise choices and intentions overall? (Comparative effectiveness of tested strategies.)

- Research hypotheses

H1 (Industry practice).

Award-recognised operators display a higher prevalence and depth of sustainability/conservation/education cues on their websites than non-award operators.

H2a (Wildlife proximity norm).

Sustainability-framed copy lowers the desire for close wildlife encounters relative to adventure copy.

H2b (WTP—conservation).

Sustainability-framed copy increases willingness to pay for conservation-contributing trips.

H2c (WT—technology).

Sustainability-framed copy increases willingness to pay for sustainable on-board technologies.

H2d (Engagement).

Sustainability-framed copy increases engagement intentions (like/share/search/talk).

H3 (Immediate appeal).

In forced binary choice with identical imagery, adventure-framed advertisements receive more immediate preference votes than sustainability-framed advertisement.

H4 (Manipulation validity).

With imagery held constant, between-advertisement differences in outcomes are attributable to message framing (copy), not to visuals.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 details our two-stage methodology, linking a visual website content analysis of 50 polar cruise operators with a controlled consumer experiment that varies advertising copy while holding imagery constant. Section 3 reports the results from the website audit and the experiment (preferences, behavioural intentions, and willingness-to-pay). Section 4 discusses the implications for sustainable polar cruise marketing and connects the findings to the prior literature. Section 5 concludes, outlining practical recommendations, limitations, and avenues for future research.

2. Methodology

This study contributes a novel, two-stage design that links a visual website content analysis of polar cruise operators to a consumer experiment, with the audit directly informing stimulus construction. Please see Table 1 for the detailed, step-by-step schematic of the two-stage methodological workflow. Advertising stimuli are systematically controlled—identical layouts and photographic frames—while only the copy varies (sustainability vs. adventure). We combine forced-choice preferences with behavioural intentions and willingness-to-pay measures, capturing both attitudinal and consequential outcomes. Together, these elements constitute a replicable pipeline for translating sustainability guidelines into tested visual communications.

Table 1.

Two-stage methodological workflow with numbered steps.

2.1. Website Content Analysis

2.1.1. Sampling

The sampled polar cruise operators were retrieved by using two means: (i) recording all the polar tourism operators in either the IAATO or AECO’s member lists, (ii) using the queries “polar cruise” on Google Search on 10 July 2023 and recording the official websites (exclusive of advertisements, blogs, and social media) of polar cruise companies in the top 100 search results. Such top results from search engines usually reflect the representative or most active/popular websites in a certain field, which is considered an important sample source for studies involving website content analysis [55]. The list of polar cruise operators was then carefully reviewed to avoid duplicates. Travel agencies, government agencies, and tourism operators that only offer non-cruising products (e.g., flights) were excluded from the sample. Next, the official websites of the remaining polar cruise operators were checked. Any operators that had no available websites or had only non-English websites were also removed from the sample dataset. The final number of polar cruise operators sampled was 50. These operators’ official websites (all pages) were downloaded and saved as offline pages for subsequent content analysis.

2.1.2. Profile of Operators

To develop a basic understanding of the sampled polar cruise operators, we identified a series of descriptive attributes used to describe each operator by carefully reviewing the websites of the sampled operators. The attributes are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Profile attributes of polar tour operators.

2.1.3. Coding

We developed a coding system to analyse website content on sustainability, conservation, and education. The codebook comprised two categories: (i) sustainability and conservation (12 codes) and (ii) education (nine codes), informed by the study’s objectives and Reamer’s [56] analysis of whale-watching cruise websites. Table 3 details the codes and descriptions [56]. Each website was assessed for the presence of relevant content, with codes recorded as “present” or “absent” in the SPSS dataset. Chi-square tests were conducted to determine differences in sustainability, conservation, and education content among polar cruise operators based on their profile attributes.

Table 3.

Coding System and Description of Codes.

2.1.4. Visual Research Design and Stimulus Development

Stimulus development procedure. Advertisement stimuli were derived from the website audit—capturing what operators currently communicate—and guided by best-practice visual communication principles from the literature [59]. This ensured the designs were both ecologically valid and theoretically grounded.

Foundational visual insights: our website audit coded sustainability, conservation, and education signals across operators’ sites (e.g., best-practice, responsible wildlife encounters, and education on board). These codes revealed which visual and narrative elements (e.g., proximity to wildlife, conservation/education framing) are most prevalent in award-winning operators’ digital communications and thus should be manipulated directly in experimental advertisements.

Stimulus logic: guided by that audit, we built six portrait-format adverts in matched pairs that hold the image constant while swapping the copy: control (adventure/close-up encounter emphasis) versus test (sustainability/education/conservation emphasis). Photographs systematically vary human–wildlife framing: (A) penguin with distant/blurred humans and boats, (B) penguins only, (C) close human–penguin proximity—allowing us to test textual effects while acknowledging visual sensitivity to distance cues. Layout, typography, and length were held constant across all six adverts.

Experimental controls and tools: participants were randomly assigned to advert conditions with order balancing, then the intentions were evaluated (like/share/search/talk) on 5-point scales before completing a binary forced-choice between sustainability versus adventure versions of the same image. We implemented this in a mainstream survey platform, sampling ensured balanced groups, and we analysed open-ended responses qualitatively and quantitative outcomes with standard statistical packages.

Rationale: Holding images constant within pairs eliminates confounding by photographic content and isolates the treatment effect of message framing. Embedding human–wildlife distance operationalises a visual best-practice consideration surfaced by the audit. Forced-choice plus intentions and WTP items capture both preference trade-offs and action-oriented outcomes; randomisation and order balancing minimise position effects.

2.2. Consumer Reception Survey

We surveyed a national adult sample (n = 790 valid responses) with balanced assignments across content and order groups, enabling clean comparisons between message effects. Demographic distributions were similar across groups. Participants were recruited via CloudResearch Connect between 1 and 8 August 2024 using unique panel links. Eligibility was screened prior to consent and required age ≥ 18, current U.S. residence, and interest in polar cruise tourism (i.e., willingness to consider a cruise). Eligible respondents who consented were randomly assigned to advertising-copy conditions (e.g., sustainability vs. adventure) while imagery was held constant, the survey platform balanced groups automatically. In total, 811 panellists initiated the survey; after applying the pre-specified exclusion rules above, 790 respondents provided valid data and were retained for analysis (97.4% of starters). Randomization remained balanced across conditions.

2.2.1. Sampling and Data Analysis

The questionnaire, incorporating Experiments I and II, was developed using the online survey platform Qualtrics XM. It underwent pre-testing and pilot testing to ensure clarity and correct execution of the experiments following University of Otago Ethics research approval (Reference D23/210). Respondents were recruited via CloudResearch Connect, a widely used platform for distributing surveys and gathering high-quality responses efficiently. Once the target sample size (n = 800) was achieved, the data were downloaded for analysis. One-way ANOVA, Univariate General Linear Model (GLM), and Chi-square tests were used to assess the differences between experimental groups. Statistical analysis was conducted in SPSS Version 27, while open-ended responses were analysed using NVivo Version 14.

2.2.2. Design of the Experimental Advertisements

Six experimental advertisements with distinct images and text but a consistent design were developed for the survey to compare consumer preferences for traditional versus sustainability-focused marketing. Each advert followed a 3:4 portrait ratio, featuring a capitalised headline, a sub-headline, and a photographic image, accompanied by eight lines of descriptive text in black on a white background. The layout remained uniform across all six adverts, with variations in text and imagery distinguishing sustainable and unsustainable tourism messaging between the test and control groups.

As detailed in Table 4, the control adverts (A1, B1, C1) shared identical text highlighting adventure, close-up wildlife encounters, and entertainment, while the test group (A2, B2, C2) used the same structure to focus on sustainability, education, and conservation. Each advert contained one of three photographic images (Table 4), all featuring penguins and the Antarctic environment (e.g., sea, ice). Two images included humans: the first (A1, A2) showed blurred humans and boats in the background, while the third (C1, C2) depicted a sharply focused human close to a penguin. The second image (B1, B2) contained no human presence. For further details on the images, see Table 4.

Table 4.

The specific content in the six experimental advertisements.

2.2.3. Questionnaire

The survey questionnaire comprised four sections. First, participants were asked about prior polar cruise experiences and destinations. The second section included 12 questions assessing their likelihood of taking an Antarctic cruise (Q2), evaluations, and behavioural intentions after viewing experimental adverts (Q3–5) and attitudes towards responsible travel, sustainable tourism, and financial support for conservation (Q6). Participants were randomly shown either a control (A1) or test (A2) advert and provided feedback on likes/dislikes (Q3–4) and behavioural intentions (Q5).

To examine the effect of advert exposure on sustainability perceptions (Q6), the display order varied, appearing either before or after Q2 and Q6. This created four experimental groups: two content groups (A1/A2) and two order groups (before/after). The survey platform ensured balanced sample sizes across groups.

Participants rated four behavioural intentions—liking/sharing the advert, seeking more information, and discussing sustainable Antarctic tourism—on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very unlikely, 5 = very likely). The third section involved a binary choice experiment where participants viewed one of three advert pairs (A1/A2, B1/B2, C1/C2), each featuring the same image but different text (test vs. control, see Table 3). They selected the more appealing advert and explained their choice. The final section collected socio-demographic data (gender, age, education, and country/region).

3. Results

3.1. Website Content Analysis

3.1.1. Profile

The profile information of 50 sampled polar cruise operators was collected. Sixteen (32.0%) of these companies operated polar tourism exclusively, while the rest (34, or 68.0%) of them focused on both polar and non-polar destinations. With respect to these polar destinations, the majority of the sampled companies (36, or 72.0%) covered both Arctic and Antarctic cruises; five (10.0%) focused on the Arctic expeditions only; nine (18.0%) focused on Antarctic cruises only. All the Arctic expeditions had landing activities at one or more sites. For Antarctica, six companies offered ‘cruise only’ while the rest had at least one landing site in their itineraries. The majority of the sampled companies (32, or 64.0%) owned one to three ships for polar cruises. Eighteen companies (36.0%) had more than three ships for tourism in the polar destinations.

With respect to social media and interactive features, 21 (42.0%) operators presented customers’ reviews/feedback/testimonials (or the links to such content) on their websites. Most sampled operators (45, or 90.0%) displayed at least one social media account/platform on their website. The median number of social media accounts/platforms is four (ranging from 0 to 8).

3.1.2. Sustainability and Conservation Elements on Websites

Regarding sustainability and conservation elements on the sampled websites, 27 (54.0%) sampled operators noted that they were members of the AECO, while 41 (82.0%) noted that they were members of the IAATO. A total of 31 (62.0%) operators listed at least one ‘green partner’ (i.e., education, conservation, or sustainability organisations) on their website (textual descriptions or simply a list of icons/logos). Moreover, 12 (24.0%) operators had received awards, eco-labels, or validation regarding sustainability, conservation, and/or education at least once and displayed them on their website. Also, 12 (24.0%) operators provided downloadable materials regarding sustainability, conservation, and/or education, such as detailed sustainability strategies, practices, or impact reports.

3.1.3. Descriptions Regarding Sustainability, Conservation, and Education

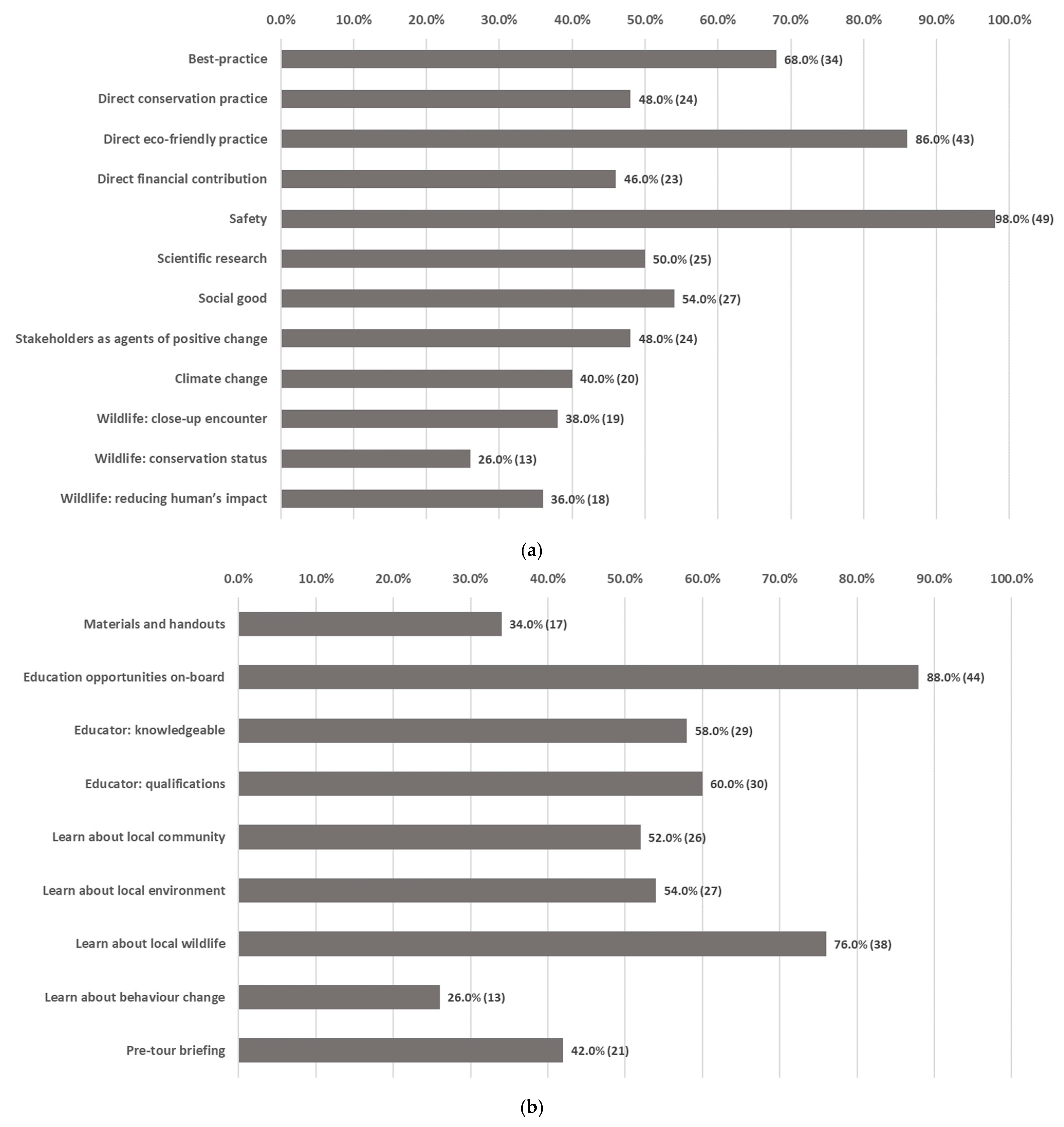

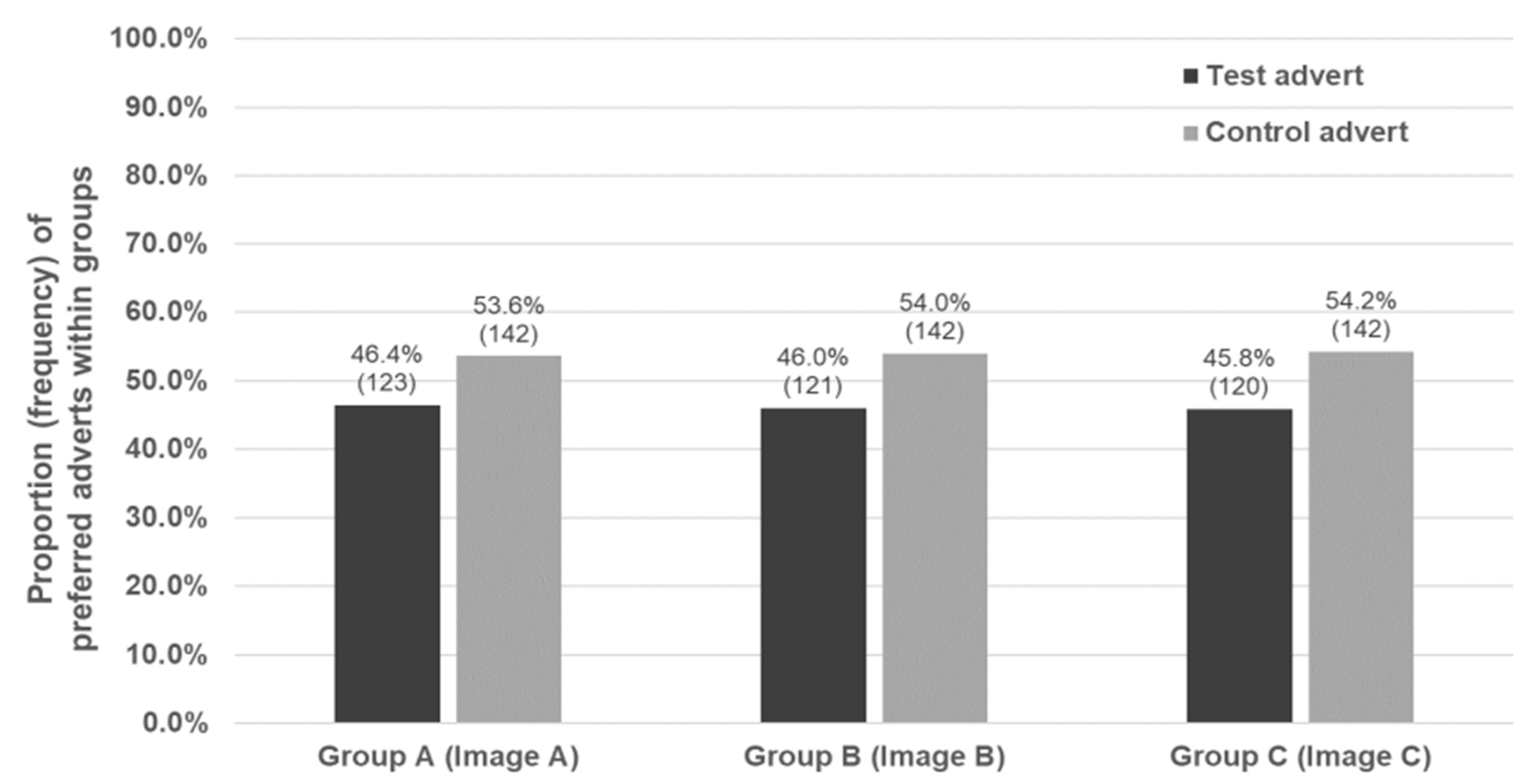

A summary of the results of the website content scanning is shown in Figure 1a,b. All the sample operators have referred to at least one code in the category Sustainability and conservation. In this category, the codes Safety, Direct eco-friendly practice and Best-practice were referred to by the majority of the sample operators (98%, 86%, and 68%, respectively; see Figure 1a for details). The coverage of the rest of the codes was generally between 30% and 50% of the sample websites. The mention of terms regarding the conservation status and/or rarity, such as ‘rarest’ and ‘endangered’ has the least coverage (26.0%). Regarding the category Education, the codes Education opportunities on-board (88%) and Learn about local wildlife (76%) were the most commonly mentioned codes across the different sample websites, while the least mentioned code was Learn about behaviour change, i.e., what the tourists can do at home as outcomes of on-board education (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

A summary of the website content scanning results. Percentages of websites (numbers of operators) that had content conforming to a certain code out of the total sample website (n = 50). Codes were grouped into two categories: sustainability and conservation (a), and education (b).

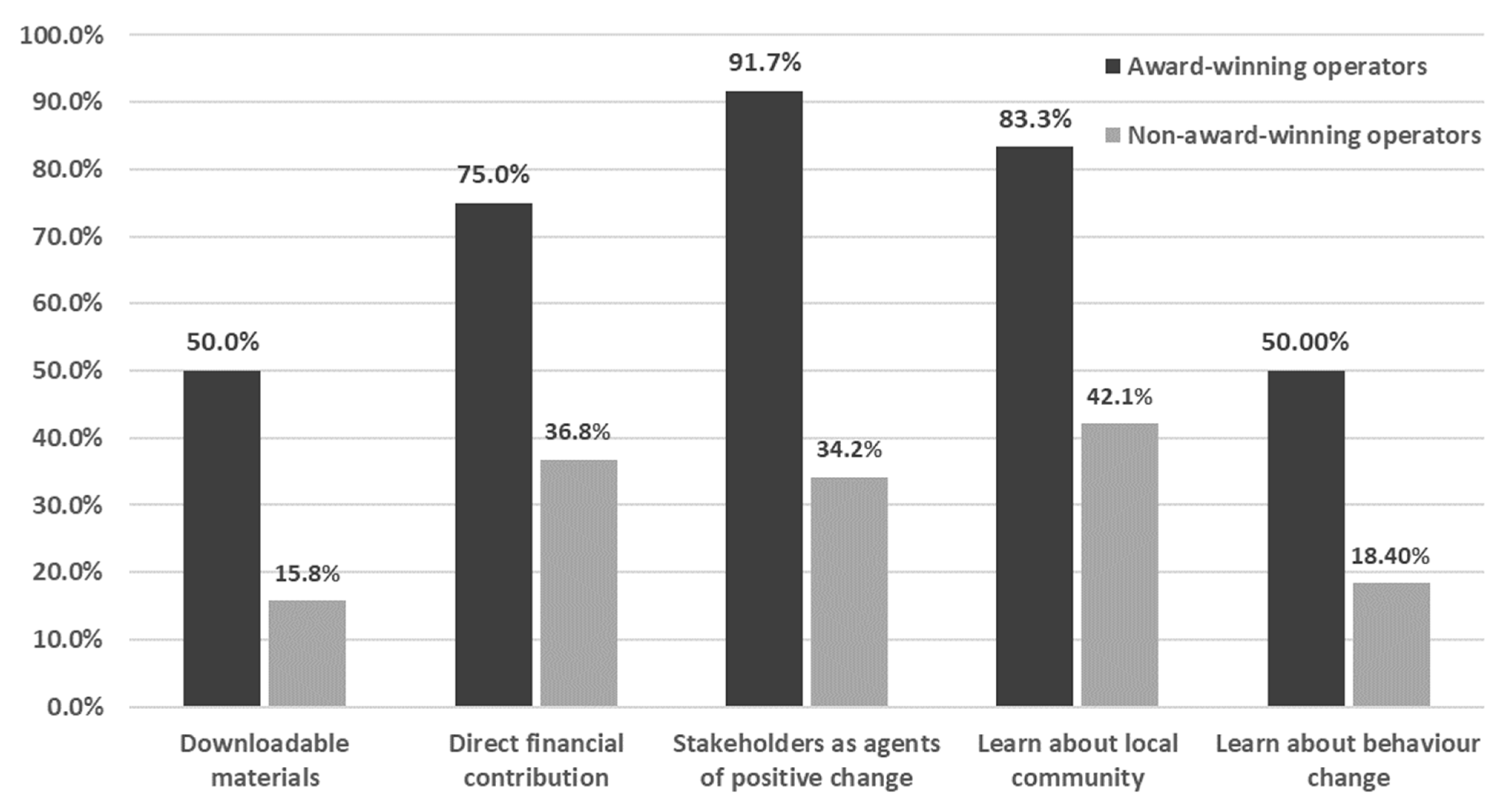

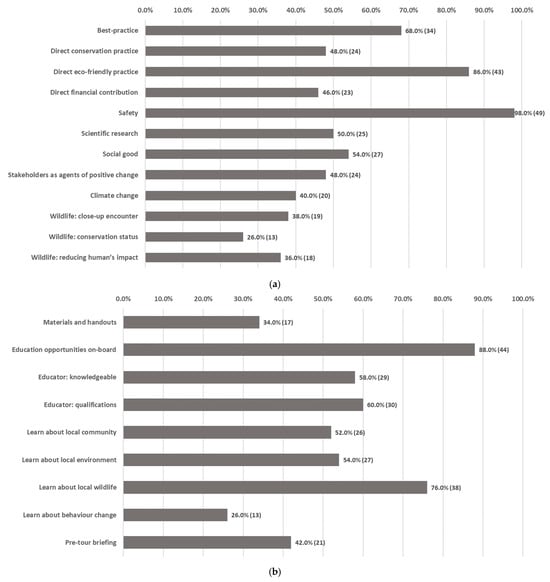

Results revealed that award-winning operators (received the awards, eco-labels, or validation regarding sustainability, conservation, and/or education at least once and displayed them on the website) and non-award-winning operators (have not received such awards or did not display them on the website) showed some significant differences on the content regarding sustainability, conservation, and education on their websites. Specifically, as presented in Figure 2, first, more award-winning operators (50.0% of them) provided downloadable materials regarding conservation/sustainability/education than non-award-winning operators (15.8% of them), by Chi-square test, X2 (1, N = 50) = 5.85, p = 0.016. Second, 75.0% of the award-winning operators claimed that they had provided direct financial contributions (regarding conservation, sustainability, and/or education). By contrast, only 36.8% of the non-award-winning operators noted this (Chi-square test, X2 (1, N = 50) = 5.35, p = 0.021). Third, 91.7% of the award-winning operators described stakeholders’ positive changes on their website, while 34.2% of the non-award-winning operators referred to this code (Chi-square test, X2 (1, N = 50) = 12.06, p < 0.001). Also, more award-winning operators (83.3%) referred to the code Learn about local community than non-award-winning operators (42.1%), by Chi-square test, X2 (1, N = 50) = 6.21, p = 0.013. Furthermore, more award-winning operators (50.0%) referred to the code Learn about behaviour change than non-award-winning operators (18.4%), by Chi-square test, X2 (1, N = 50) = 4.73, p = 0.003.

Figure 2.

A summary chart of the presence of different codes on the websites of different types of operators (characterised by whether they had won awards regarding sustainability, conservation, and/or education). Percentages represent the number of the websites which referred to a certain code out of the total sample website (50). Only significant differences are provided.

Because image frames were held constant within each choice pair, between-advert differences primarily reflect textual framing rather than photography. Randomisation and order balancing further reduce bias. This design choice explains why preference splits track message tone while willingness-to-pay and intention outcomes respond to the sustainability frame.

3.2. Consumer Reception Survey

We surveyed a national adult sample with balanced assignment across content and order groups, enabling clean comparisons of message effects. Demographic distributions were similar across groups.

Sample Profiles

A total of 811 respondents participated in the questionnaire survey, of which 790 (97.4%) of them provided valid answers and were from the targeted region (the United States) for this survey. Therefore, the sample size for the subsequent analysis was based upon these 790 responses. The profiles of the sample population are reported in Table 5. The gender ratio of the sample was generally balanced: 48.1% were female and 50.1% were male. The majority of the respondents were aged 25–44 years (25–34 years: 31.3%; 35–44 years: 27.5%). Most participants were relatively well-educated: 84.1% of them have completed a tertiary education (e.g., Graduate Diploma, Bachelor’s Degree, Master’s Degree, or Doctoral Degree). The distributions of demographic attributes of the respondents were generally similar across the experimental groups.

Table 5.

The socio-demographic profiles of the participants (n = 790).

Most of the participants (753, 95.3%) had never been on a cruise to the polar regions, while 37 respondents had experienced such cruises and reported their specific destinations. Amongst these polar destinations, Alaska was the most popular destination (14 participants reported), followed by Antarctica (8 respondents), the Canadian Arctic (4 respondents), and Greenland (4 respondents). A few participants also mentioned they had visited other polar destinations, such as Norway and Iceland (less than three respondents for each destination).

3.3. Experiment I: The Impact of Textual Content and Order of Displaying

3.3.1. Likelihood of Visiting Antarctica

Nearly a quarter of the respondents (25.8%) were likely (21.4%) or very likely (4.4%) to go on a cruise to Antarctica in the future. The rest of them did not express an intention to visit Antarctica: 40.1% of them were “Unlikely” or “Very unlikely” to go, and 34.1% were “Undecided”. The content of the adverts (test and control), the order of displaying the adverts (before or after this question), and all the demographic attributes did not have significant impacts on the intentions here (GLM, model significance p > 0.05; for all the factors, p > 0.05).

3.3.2. Agreement to Conservation and Responsible Tourism

Generally, the results of the participants’ rating on the five statements regarding conservation and responsible tourism (Q6) revealed that the majority of them expressed a relatively high environmental awareness: 89.0% of them agreed (44.9% agreed and 44.1% strongly agreed) that they would choose an operator who supports responsible wildlife encounters. Even though over half of the participants agreed (38.1%) or strongly agreed (20.9%) that they would choose an operator that brings them in the closest proximity to wildlife, the majority of them still agreed (42.4% agreed and 29.1% strongly agreed) that if they saw irresponsible operational practices, they would express concerns. A total of 58.2% of the participants were likely to pay a premium for a trip that contributes to conservation (41.5% agreed and 16.7% strongly agreed). A similar proportion of the participants reported that they would pay a premium for a trip that uses sustainable technologies to reduce waste and emissions (39.5% agreed and 16.2% strongly agreed).

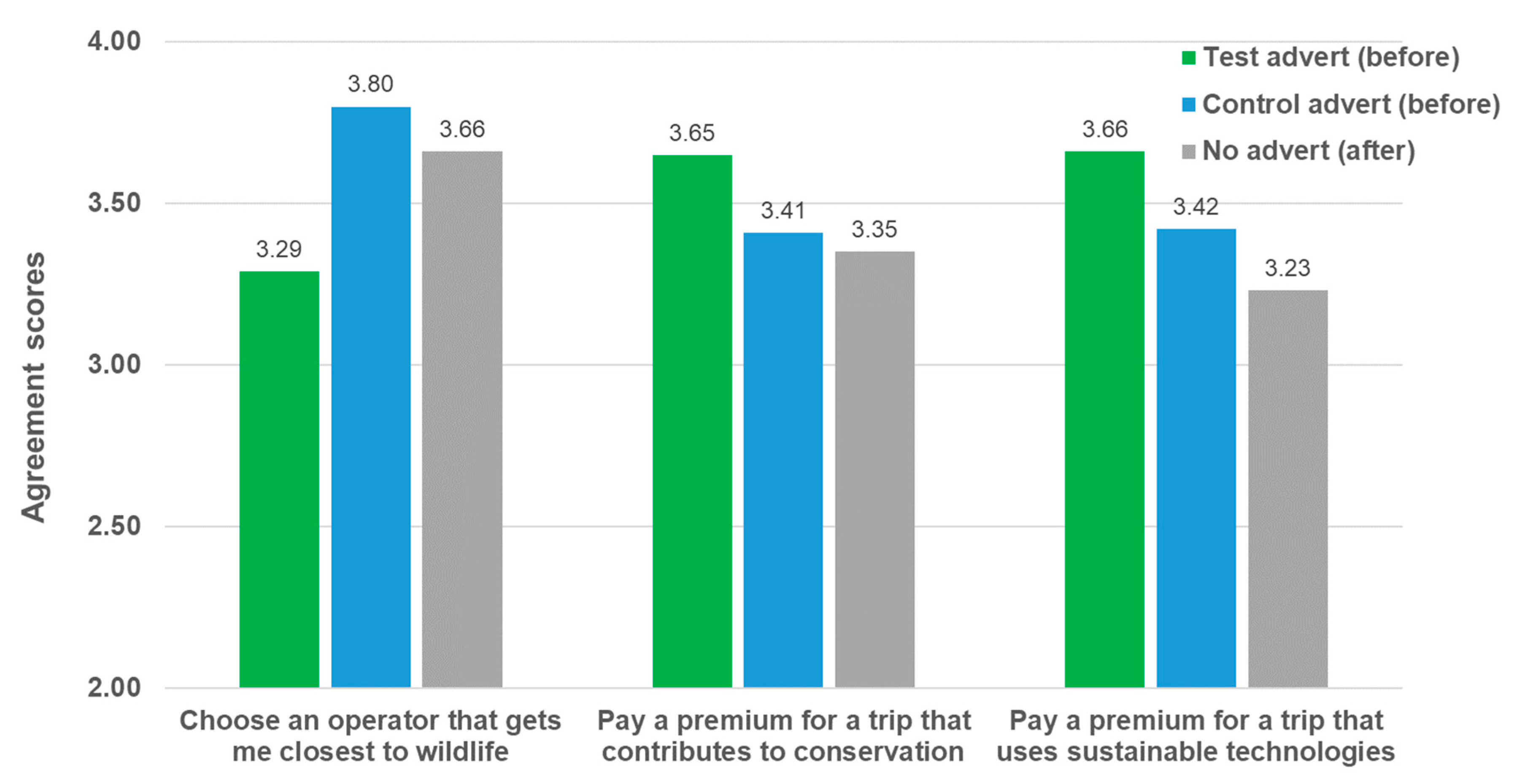

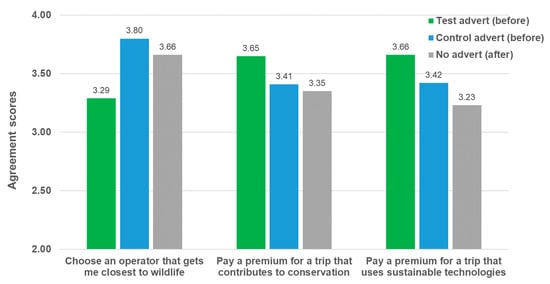

Considering the experimental groups, the text content of the advert (both test and control) significantly influenced respondents’ agreement with three out of the five statements in Q6 (Figure 3). The order of item presentation did not show a clear effect: for Q6, we combined the “test after” and “control after” groups into a single group called “no advert” since the advert was shown after Q6 in both groups, and the items displayed before Q6 were identical. Results showed that the mean agreement scores in the “no advert” group were similar to those in the control group (control before). The statistical significance of these impacts and the pairwise comparisons are detailed below.

Figure 3.

Participants’ agreement to the following statements: (i) choose an operator that gets me closest to wildlife, (ii) pay a premium for a trip that contributes to conservation, and (iii) pay a premium for a trip that uses sustainable technologies. Scores were presented based on a five-point Likert scale, i.e., one = strongly disagreed with the statement, five = strongly agreed. The no advert group was a merged group from the “test after” and the “control after”.

First, after viewing the test advert (sustainability content), participants were less likely to be interested in close-up encounters with the wildlife: there was a significant difference in the mean agreement scores (i.e., one = strongly disagreed to the statement, five = strongly agreed to the statement) between the test group (M = 3.29, SD = 1.07) and the remaining groups (control group: M = 3.80, SD = 1.03; no advert group: M = 3.66, SD = 1.05) (ANOVA, F (2, 787) = 12.4, p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons reported a significant difference between the test group and the control group (post hoc LSD test, p < 0.001), and also between the test group and the no advert group (post hoc LSD test, p < 0.001). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the mean scores between the control group and the no advert group (ANOVA post hoc LSD test, p > 0.05).

Second, the willingness of respondents to pay a premium (up to 10%) for a trip that contributes to conservation was significantly impacted by the content of the advert (ANOVA, F (2, 787) = 4.4, p = 0.012). Respondents were more likely to pay such a premium after viewing the test advert (sustainability content) compared to those in the control advert group and no advert group (Mtest = 3.65, SD = 1.07; Mcontrol = 3.41, SD = 1.20; Mno advert = 3.35, SD = 1.20; post hoc LSD test, p = 0.043 between the test and control groups; p = 0.003 between the test and no advert groups).

Similarly, the sustainability advert also significantly impacted the respondents’ intention to pay a premium for a trip that uses sustainable technologies to reduce waste and emissions (ANOVA, F (2, 787) = 8.7, p < 0.001). We identified that the respondents had a higher willingness to pay after viewing the test advert (Mtest = 3.66, SD = 1.11; post hoc LSD test, p = 0.039 between the test and control groups; p < 0.001 between the test and no advert groups), compared to those who viewed the control and no advert groups (Mcontrol = 3.42, SD = 1.19; Mno advert = 3.23, SD = 1.21; post hoc LSD test, p > 0.05 between the control and no advert groups).

3.3.3. Liked and Disliked Elements of the Two Experimental Adverts

The content analysis of the open-ended answers to Q3 (liked aspects) and Q4 (disliked aspects) was conducted based on a word frequency analysis. Results revealed that the participants focused not only on the textual content in the advert but also on the visual elements, such as the image and the design (layout) of the advert. They could indeed acknowledge that sustainability and conservation were emphasised in the test advert. Table 6 reported the results of the word frequency analysis on participants’ comments on their most liked and disliked aspects after viewing the test advert (n = 392) or the control advert (n = 398). Importantly, they mentioned a number of communal liked (and also disliked) aspects in both the test and control groups. Such communal points were also noted in Table 6 (the bolded text).

Table 6.

Results of the word frequency analysis on Q3 and Q4. The 10 most frequently appeared words in each group were presented with frequencies (the number in the bracket). Bolded words represent that they are amongst the top 10 words in both the test and control groups. Group names: test liked = most liked aspects after viewing the test advert (emphasising sustainability); test disliked = most disliked aspects after viewing the test advert; control liked = most liked aspects after viewing the control advert (emphasising adventure/unsustainability); control disliked = most disliked aspects after viewing the control advert.

3.3.4. Liked Aspects of the Test and Control Adverts

In both the test (A2) and control (A1) adverts, participants showed strong interest in the image, particularly its subject—the penguin—which was frequently cited as the most appealing element. Word frequency analysis highlighted four commonly used words related to the penguin (Penguin, Wildlife, Animal, and Encounter; see Table 6). One participant noted, “The penguin is upfront and who doesn’t love penguins” (Participant 165, test group).

Participants in the control group referenced the penguin more often than those in the test group, with additional top-ranking words such as bird, cute, and close—seven of the top ten words related to the penguin. Many control group participants associated the image with close-up wildlife encounters, with the word Close appearing 46 times. For example, one participant stated, “close-up wildlife encounters. That feels more worth it” (Participant 165, control group). In contrast, the test group mentioned close only four times. Some test group participants expressed concerns about proximity to wildlife, as one explained, “I like how it outlines the sustainable practices they implement, especially the responsible wildlife encounters. It always makes me mad to see people getting too close to wildlife because it’s the wildlife that winds up paying the price, not the people” (Participant 310, test group).

Beyond the image, participants also noted the strong environmental conservation and sustainability messages in the test advert. Many appreciated the focus on responsible wildlife encounters and educational elements promoting nature and wildlife protection, particularly in the Antarctic ecosystem. Four of the top 10 words for the test advert reflected these themes (Sustainability, Responsible, Protect, Conservation; see Table 6). One participant remarked, “what I like most is the phrase ‘Cruise sustainably. Your Choice. Their future’. This message really hits home that we need to be responsible for our actions” (Participant 57, test group). Another highlighted the appeal of sustainability and education: “the focus on responsible wildlife encounters and commitment to conservation are great. The mention of educational opportunities also draws me in. This honestly sounds like the type of trip I’d enjoy taking” (Participant 177, test group). A few participants also linked the image to the sustainability message, such as one who observed, “the use of penguin nesting imagery to depict the sustainable aspects of the ad” (Participant 16, test group).

3.3.5. Disliked Aspects of the Test and Control Adverts

Negative feedback primarily focused on the advertisements’ design and messaging. Participants criticised visual elements, including colours, text formatting, font style, and layout, describing them as unappealing or amateurish. Both test and control adverts received similar design-related complaints, with five of the top ten disliked words shared across groups, four of which related to design: colour, red, green, and font (see Table 6). Red and green, used in the headline, were particularly criticised. One participant noted, “the red and green lettering is terrible. Makes it seem like one of those political slam ads” (Participant 138, test group), suggesting the colour choices negatively affected both aesthetics and message delivery. A control group participant echoed this concern: “I don’t like the red lettering... It gives off a weird vibe that makes you not want to go on this kind of cruise” (Participant 223, control group).

Content-related criticism varied between adverts. The test advert, which focused on sustainability, was perceived by some as guilt-inducing, with the word exploit (frequency = 33) being particularly contentious. One participant stated, “ads should be positive, and the word exploit feels too harsh or negative” (Participant 667, test group). Others found the message too confrontational or lacking specificity regarding sustainable practices: “it looks more like a warning than an invitation” (Participant 668, test group).

For the control advert, negative comments centred on environmental concerns and wildlife disturbance, particularly due to the emphasis on close encounters. As a result, wildlife, close, and penguin ranked among the most frequently cited disliked words (frequencies: 32, 30, and 29). Additionally, the ship (frequency = 56) in the background was perceived as an industrial element conflicting with environmental values. One participant remarked, “I hate that they are so close to the penguin nest with the big industrial boat in the background” (Participant 66, control group), while another noted, “the industrial ship in glaring view makes it seem like sustainability is not part of the business model” (Participant 86, control group). Some participants also expressed concerns about the impact of close-up encounters on wildlife, with one stating, “getting that close to animals messes up their ecosystem” (Participant 345, control group).

3.3.6. Behavioural Intentions

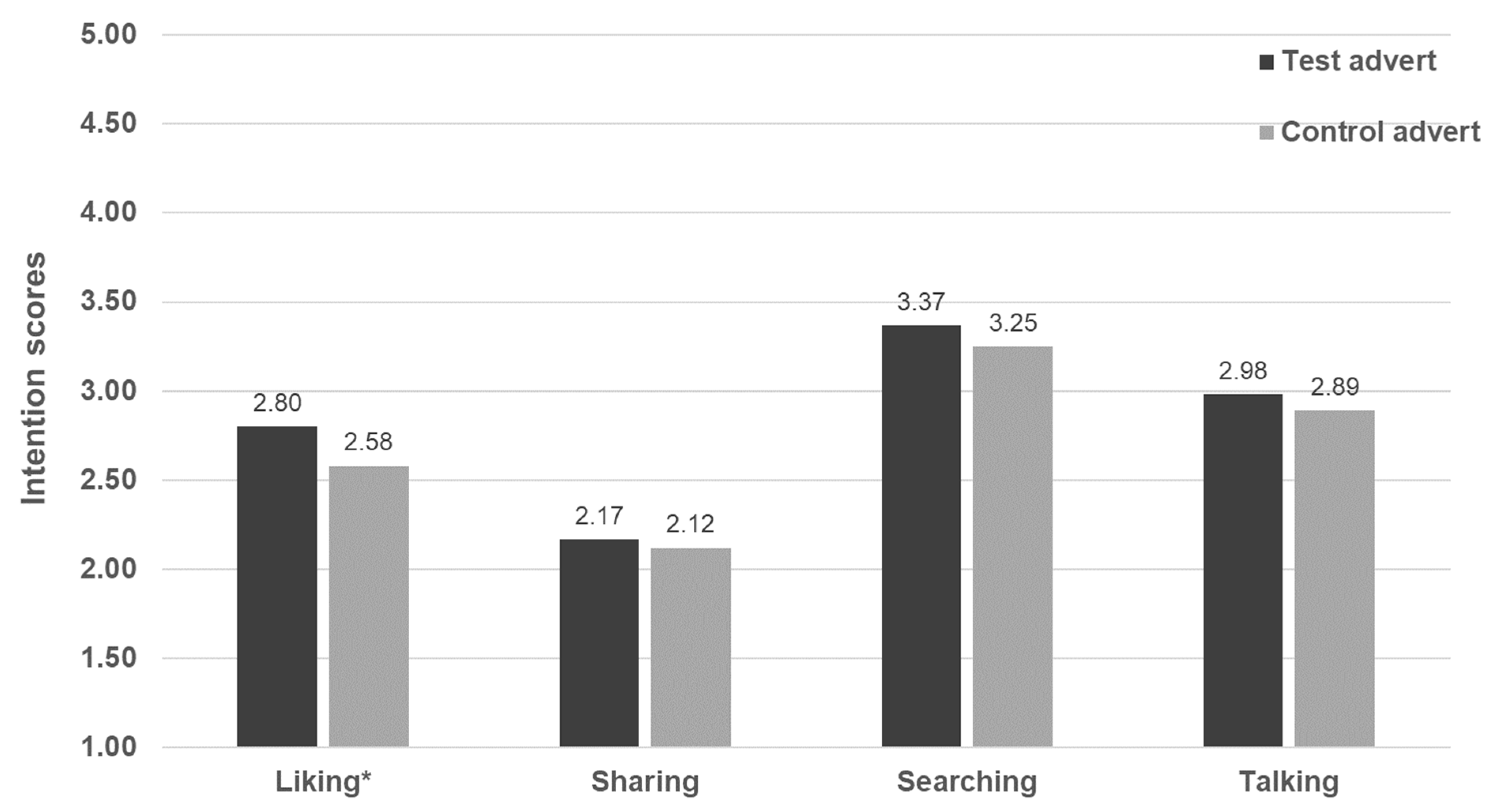

On the whole, the participants demonstrated varying levels of interest in the four behaviours: 34.6% of the participants intended to like the advert on social media (25.7% likely and 8.9% very likely; M = 2.69, SD = 1.34, based on the five-point Likert scores); 15.5% of the participants intended to share (11.7% likely and 3.9% very likely; M = 2.15, SD = 1.17); 56.5% of them would search for the sustainable Antarctic cruise tourism (42.2% likely and 14.3% very likely; M = 3.31, SD = 1.25); and 42.3% of them would talk to others about sustainable Antarctic cruise tourism (35.3% likely and 7.0% very likely; M = 2.94, SD = 1.24).

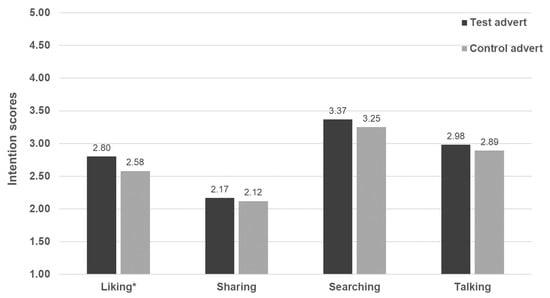

The Univariate General Linear Model (GLM) was employed to test whether there was a significant difference in the Likert scores between groups. Two categorical factors (content, i.e., test/control, and order, i.e., before/after) and the interaction (content*order) were entered into the model, while the dependent variables of the models were the mean Likert scores of the four behaviours. As given in Figure 4, the only significant model is the one that used Liking on social media as the dependent variable (GLM, F (3, 786) = 3.1, p = 0.026), suggesting the experimental group(s) had a significant impact on scores. Specifically, we identified that the only significant independent variable in this model was the content of the advert (GLM, the factor Content, F (1, 786) = 5.2, p = 0.023), whereas the impacts of order and interaction were insignificant. Thus, after viewing the test advert, the participants were more likely to “like” it on social media, compared to the control advert (Mtest = 2.80, SD = 1.34; Mcontrol = 2.58, SD = 1.33). The three insignificant GLMs (dependent variables: intention to share, search, and talk, see Figure 4) represented that the influences of both content and order on willingness to share, search, and talk were not significant.

Figure 4.

Participants’ behavioural intentions after viewing the adverts. The scores were reported based on a five-point Likert scale, i.e., one = very unlikely, five = very likely. * Significant difference in intention scores between test and control group.

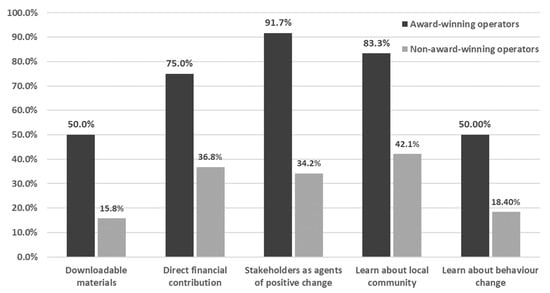

3.4. Experiment II: Cognitive Appeal of the Adverts with Different Content

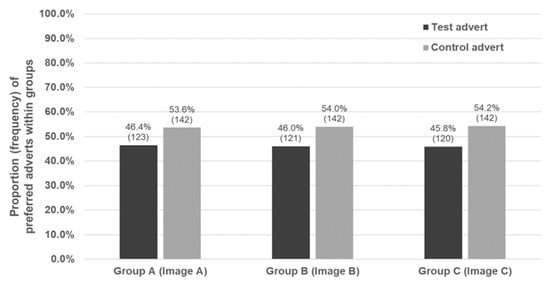

This part of the results corresponded to Part III of the questionnaire. The three experimental groups had similar sample sizes (Group A, n = 265; Group B, n = 263; Group C, n = 262). The participants ticked their preferred adverts from the binary choice set displayed and explained the reasons for their choices. Results revealed that all three control adverts in the three groups received more votes (i.e., number/frequency of the participants who ticked this advert as preferred) than the test adverts in the same group. Interestingly, the differences in the votes between the test and control adverts across the three groups were similar, i.e., Group A: 142 (control) versus 123 (test); Group B: 142 (control) versus 121 (test); Group C: 142 (control) versus 120 (test), even though the advert pairs in different groups contained different images (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The proportions and frequencies of votes for the preferred adverts in the three experimental groups. The three groups contained three different binary choice sets of adverts, respectively.

The above frequencies, as well as the content analysis on participants’ explanations, suggested that the participants’ preferences were mainly based on the text in the advert. However, the different images in the three groups did not play a notable role in the preferences of participants, because the votes across the three groups had similar frequency proportions, and very few participants referred to the images in their comments.

According to the content analysis on their explanations, the participants who preferred the three control adverts (adverts A1, B1, or C1) provided similar reasons, even though they were divided into three different groups. These reasons are summarised as follows.

- (i)

- Positive and Encouraging Tone

Many participants perceived the control adverts as more positive, uplifting, and aspirational compared to the test adverts. They appreciated the emphasis on adventure and entertainment, key aspects people seek in vacations. The control adverts were also seen as more straightforward and less confrontational in tone, making them more appealing. One participant noted, “It (Advert B1) sounds more fun and exciting. While (Advert B2) is true and more responsible, it makes me feel I shouldn’t go at all” (Participant 411, preferred B1 from the B1/B2 choice set).

In contrast, participants criticised the test adverts for their harsh, demanding, or guilt-inducing language, which some felt resembled an environmental campaign rather than a tourism advertisement. A few suggested that a combination of messaging from both the test and control adverts would likely be more effective and engaging.

- (ii)

- Highlighting Vacation Travel Features

The emphasis on entertainment, close-up wildlife encounters, and overall enjoyment in the control adverts appealed to many respondents, as these were key factors they considered when planning a polar vacation. They favoured these aspects over the conservation and sustainability focus of the test adverts, which some perceived as overly moralising. One participant remarked, “If I’m on a vacation, I’m not interested in being ‘responsible’ or ‘sustainable,’ so (Advert B1) beats (Advert B2)” (Participant 524, preferred B1 from the B1/B2 choice set).

Conversely, those who preferred the test adverts (A2, B2, or C2) provided distinct reasons for their choice. They appreciated the positive, sustainable, and educational messaging, viewing it as a more responsible option for environmentally conscious travellers. Many cited alignments with their personal values regarding environmental conservation and responsible tourism, as the test adverts resonated with their desire to travel in a way that reflects their ethical beliefs. Their specific reasons for choosing the test adverts are outlined below.

- (i)

- Emphasis on Responsibility and Sustainability

Many participants appreciated that the test adverts highlighted responsible tourism and sustainability. They felt that this advert was more aligned with ethical practices and environmental consciousness. For example, a participant said, “I would want to protect nature and the environment while exploring on a cruise. It’s important to be a good citizen of this Earth. We’ve only got one!” (Participant 359, preferred B2 from the choice set B1/B2). Nevertheless, a number of participants who voted for the test adverts still pointed out that it needed to be rephrased, for example, “I am a huge supporter of sustainability. However—if you are trying to promote sustainable Antarctica travel, I think you should rephrase it because it sounds more like ‘Stay away!’” (Participant 276, preferred B2 from the choice set B1/B2).

- (ii)

- Educational and Professional Messaging

Respondents were drawn to the test adverts’ educational content and its positive, non-exploitative approach to wildlife and nature. They preferred such an informative and professional tone that encouraged learning and awareness, such as “I’d rather have educational activities over entertainment ones, to be honest, and the rest is that I must place higher priority on sustainability and wildlife ethics than I can on any of my personal desires” (Participant 78, preferred A2 from the choice set A1/A2).

- (iii)

- Concerns for Conservation

Many comments reflected a strong concern for wildlife conservation, animal welfare, and ethical considerations. Participants favoured the test adverts because it seemed to prioritise the well-being of wildlife and the integrity of natural habitats, such as “I like it (Advert C2) more because it suggests that they do not exploit wildlife and in turn, if I were to book with them, I would not be exploiting either. I would be aiding conservation with my purchase” (Participant 646, preferred C2 from the choice set C1/C2).

- (iv)

- The Influence of Images

The images in the adverts were not a significant element that affected the participants’ preferences for the adverts, as the images in each binary choice set were the same. However, a few participants did refer to the images in their comments, and almost all such comments were from the choice set C1/C2, where the photograph contained a human becoming close to a penguin. The participants generally focused on the appropriateness and impact of such proximity on wildlife. They expressed concerns about the closeness of the human to the penguin in the image, fearing that it might disturb or negatively impact the wildlife, such as “I feel the person’s too close to the penguin in both ads.” (Participant 620, preferred C2 from the choice set C1/C2). Importantly, since the photo used in advert C2 showed a very close encounter with a penguin, a participant felt that it contradicted the advertised claim of responsible tourism and conservation. This discrepancy led the participant to doubt the authenticity of the textual message, describing the advert as “fake”.

In sum, when linking the empirical findings to the stated hypotheses, the website audit supports H1, with award-recognised operators showing deeper sustainability, conservation, and education cues than others. In the experiment, sustainability-framed copy reduced the desire for close wildlife encounters (H2a supported) and increased willingness to pay for both conservation trips (H2b supported) and sustainable on-board technologies (H2c supported). Effects on engagement intentions were mixed—only “like on social media” increased (H2d partially supported). In forced binary choices with identical imagery, adventure-framed adverts drew more immediate preferences (H3 supported). Because imagery was held constant within pairs, observed differences are attributable to message framing (copy) rather than visuals (H4 supported).

4. Discussion

The sustainability of polar cruise tourism continues to be a topic of debate, particularly concerning the balance between environmental protection and tourism growth. Researchers highlight the necessity for adaptive management strategies that address both the ecological and economic dimensions of tourism [6]. In this regard, the role of branding and marketing in sustainable tourism management is often overlooked. This study set out to examine how sustainability is communicated in polar cruise marketing and whether alternative advertising frames can steer consumer intentions toward lower-impact choices. Together, a website audit and a controlled consumer experiment provide convergent evidence that marketing—when executed with credibility and coherence—can function as a management lever in fragile destinations.

Consistent with H1, award-recognised operators embedded richer and more specific sustainability, conservation, and education cues than non-award operators. Beyond descriptive difference, this pattern aligns with e-marketing and service-quality research showing that purpose-designed, high-quality content, reinforced by credible eWOM, can elevate perceived value and intention while reducing perceived risk [65,66,67]. Mechanistically, these signals likely operate via (i) quality/competence cues (clear guidelines, science partners, and monitoring), (ii) integrity cues (transparent commitments and evidence), and (iii) community-benefit cues, which together can build trust and reduce uncertainty prior to purchase. Framed through tourism imaginaries, such digital narratives travel with visitors into place, shaping norms and practices on-site [53,61]. Thus, sustainability pages do more than inform; they prime expectations, supply scripts for “how we do things here,” and thereby extend management influence upstream of the voyage. In governance terms, branding and marketing emerge as underused instruments within adaptive management portfolios [6].

H2a–H2d were largely supported. Holding images constant, sustainability-framed copy reduced the desire for close wildlife encounters (H2a), aligning promotional messaging with best-practice distance norms; it also increased willingness to pay (WTP) for conservation-contributing trips (H2b) and for on-board sustainable technologies (H2c). These shifts mirror prior evidence that ethical/sustainability messaging and environmental education can heighten ecological awareness and translate into price premia when benefits are concrete and verifiable [50,51,68,69,70,71]. The pattern is theoretically coherent with norm-activation and value–belief–norm perspectives: articulating responsible practice as the default activates personal norms while making compliance feasible and identity-consistent. At the same time, engagement effects were selective (H2d): “likes” rose, but sharing/talking/searching did not, consistent with dual-process accounts (e.g., Elaboration Likelihood Model of persuasion; [72]) in which low-effort value alignment does not automatically generalise to higher-cost diffusion without social incentives, efficacy cues, or platform affordances. Practically, this suggests that complementing sustainability claims with community endorsement, peer cues, or participatory calls that lower the psychological cost of advocacy.

Executional coherence emerged as pivotal. Participants flagged reactance when visuals appeared to contradict conservation claims (e.g., very close human–penguin proximity), undermining credibility. This accords with advertising congruity and wildlife-tourism guidance on minimum approach distances and visual ethics: images act as norms-in-use, and if they conflict with text, they risk normalising precisely the behaviours operators seek to discourage [26]. Beyond simple “consistency,” this points to creative guardrails: a shared asset library depicting wildlife-safe distances; pre-flight congruence checks; and exclusion of imagery that could be read as rule-breaking even if technically compliant (e.g., long-lens compression).

Findings for H3 revealed a fast–slow processing tension. In forced binary choices, adventure-framed adverts captured more instant preferences, even as sustainability frames improved reflective, consequence-bearing outcomes (distance norms and WTP). Adventure language efficiently recruits approach motivation (novelty, awe, and competence) at first glance, while sustainability information appears to recalibrate judgements when people consider implications and costs. The design implication is integration—not substitution: retain the effective promise of adventure while embedding precise, verifiable sustainability benefits and explicit behavioural expectations. This is consistent with transformative service research showing that purpose cues are most effective when coupled with tangible value and an engaging narrative, and with observations that Antarctic marketing often emphasises extremity and adventure [50]. To avoid moral fatigue or perceived preachiness, sustainability copy should be concrete (named funds/technologies, specific guidelines), efficacy-focused, and framed as enabling rather than restricting the experience.

H4 is supported by design controls (constant imagery; balanced order), making message framing the parsimonious explanation for observed differences. Notably, the sporadic scepticism we observed maps to copy-image incongruence, underscoring that internal validity can be preserved in design yet lost in execution if asset choices drift from the narrative.

Taken together, the website audit and experiment underscore the dual role of digital platforms and advertising in promoting tourism and advancing conservation goals. Three practice moves follow. First, architect websites to surface guidelines, science partnerships, monitoring, and community contributions in usable, evidence-backed formats, reinforced by credible third-party signals [65,66,67]. Second, translate these cues into specific, verifiable advertising commitments that normalise responsible wildlife distances and justify price differentials through transparent conservation and technology investments [66,67,68,71]. Third, enforce copy-image coherence with wildlife-safe visual standards and blend adventure-led attention capture with sustainability-led meaning, aligning with stakeholder aspirations that polar tourism benefits conservation and communities [73,74] while maintaining educational and entertainment value [75].

Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, it relies on a cross-sectional, online panel of U.S. adults interested in polar cruising, so results may not generalise to other markets or to non-interested consumers. Second, the consumer experiment measures stated preferences and intentions rather than observed booking behaviour. Third, to isolate message effects, the adverts held imagery constant and varied copy, but all images featured penguins/Antarctica; different visuals, destinations, or media (e.g., video) might yield different effects. Fourth, the website audit covered English-language operator sites at a single time point; content changes over time and non-English materials were excluded. Finally, self-report data are subject to attention, speed, and social-desirability biases despite quality controls. Together, these factors suggest caution in generalising findings and indicate the value of longitudinal and field-based follow-ups.

Future research should (i) test behaviour in the booking path (A/B tests of creative; choice modelling with real payoffs), (ii) broaden species/visual scenarios and platforms (static vs. video; short-form vs. long-form), (iii) segment by values and travel experience to tailor frames, and (iv) track on-board compliance to close the loop from expectation-setting to behaviour. Extending the audit → stimulus-build → consumer-test pipeline to other nature-based sectors could yield a transferable, evidence-led approach to sustainability marketing that improves both visitor experience and conservation outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This project advances the discourse on sustainable polar cruise tourism by demonstrating how sustainability marketing can shape visitor expectations and support responsible operations. Integrating sustainability messaging into advertisements influences consumer attitudes and purchase decisions, encouraging support for ethical, lower-impact tourism. Our results show that well-crafted sustainability messages decrease the demand for close-up wildlife encounters and increase the willingness to pay for conservation-focused travel, reinforcing responsible practice.

Methodologically, the study makes a clear contribution by operationalising a visual audit → stimulus construction → consumer test pipeline that generates primary evidence for sustainability marketing in fragile destinations. The website audit surfaced sustainability cues already used by operators; we translated these into experimental advertisements that varied message framing while holding imagery constant and then linked audience reception to behaviourally meaningful outcomes (e.g., reduced appetite for close encounters; higher willingness to pay for conservation and sustainable technology). This visual methods-to-experiment approach is transferable to other nature-based sectors and offers a practical template for ethically aligned campaign development.

Effective marketing communication and branding are critical to cultivating environmentally conscious consumers who expect—and demand—responsible tourism products. The insights here provide actionable guidance for operators, policymakers, and researchers seeking to enhance environmental awareness and conservation outcomes. The sustainability of polar cruising depends on communication strategies that balance visitor growth with environmental protection, enabling operators to promote responsible behaviours and safeguard vulnerable ecosystems.

While polar cruises offer singular experiences, their long-term viability relies on marketing that builds awareness, mitigates impacts, and supports responsible management. Strategic advertising can steer consumer choices toward conservation and stewardship. This study provides a foundation for understanding visitor expectations, clarifying operator responsibilities, and designing effective sustainability-led marketing strategies.

Future research should examine how digital media shapes sustainable tourism behaviours and compare the effectiveness of alternative communication strategies in fostering environmental stewardship. Addressing the gap between digital sustainability claims and on-the-water operations will improve transparency, align visitor expectations with industry practices, and build trust in sustainable tourism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.F.; Methodology, W.F.; Software, L.Z.; Formal analysis, L.Z.; Investigation, W.F.; Data curation, W.F. and L.Z.; Writing—original draft, W.F.; Writing—review & editing, W.F. and L.Z.; Supervision, W.F.; Project administration, W.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB approval obtained by the Ethics Committee of Cat B Committee, University of Otago (D23/210) on 27 July 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, S.; Tan, Z.; Chen, Y.; Han, J. Research hotspots, future trends and influencing factors of tourism carbon footprint: A bibliometric analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.A.; Convey, P. The protection of Antarctic terrestrial ecosystems from inter-and intra-continental transfer of non-indigenous species by human activities: A review of current systems and practices. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasserre, F.; Têtu, P.-L. The cruise tourism industry in the Canadian Arctic: Analysis of activities and perceptions of cruise ship operators. Polar Rec. 2015, 51, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, J.; Dawson, J.; Groulx, M. Last chance tourism: A decade review of a case study on Churchill, Manitoba’s polar bear viewing industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.; Olsen, L.S.; Karlsdóttir, A. Sustainability and cruise tourism in the arctic: Stakeholder perspectives from Ísafjörður, Iceland and Qaqortoq, Greenland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1425–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, M.; Amelung, B. Climate change and its implications for cruise tourism in the polar regions. In Cruise Tourism in Polar Regions; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.; Hsu, P.-C.; Liu, F. Changes in polar amplification in response to increasing warming in CMIP6. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett. 2021, 14, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Time, tourism area ‘life-cycle,’ evolution and heritage. J. Herit. Tour. 2021, 16, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.M.; Screen, J.A.; Deser, C.; Cohen, J.; Fyfe, J.C.; García-Serrano, J.; Jung, T.; Kattsov, V.; Matei, D.; Msadek, R. The Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP) contribution to CMIP6: Investigating the causes and consequences of polar amplification. Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12, 1139–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuecker, M.F.; Bitz, C.M.; Armour, K.C.; Proistosescu, C.; Kang, S.M.; Xie, S.-P.; Kim, D.; McGregor, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, S. Polar amplification dominated by local forcing and feedbacks. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 1076–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijgelaar, E.; Thaper, C.; Peeters, P. Antarctic cruise tourism: The paradoxes of ambassadorship, “last chance tourism” and greenhouse gas emissions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Saarinen, J. Last Chance to See? Future Issues for Polar Tourism and Change. In Tourism and Change in Polar Regions; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Lemelin, H.; Dawson, J.; Stewart, E.J.; Maher, P.; Lueck, M. Last-chance tourism: The boom, doom, and gloom of visiting vanishing destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, M.; Costa, G.; Angulo-Preckler, C.; Sarda, R.; Avila, C. Contrasting views on Antarctic tourism: ‘last chance tourism’ or ‘ambassadorship’ in the last of the wild. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbens, E.H. The Arctic as the last frontier: Tourism. In Global Arctic: An Introduction to the Multifaceted Dynamics of the Arctic; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liggett, D.; Cajiao, D.; Lamers, M.; Leung, Y.-F.; Stewart, E.J. The future of sustainable polar ship-based tourism. Camb. Prism. Coast. Futures 2023, 1, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirka, H. Will Antarctica Be the Next Victim of Overtourism as Visitor Numbers Continue to Climb? 2024. Available online: https://www.thenationalnews.com/travel/2024/01/11/antarctica-overtourism/#:~:text=While%20the%20pause%20in%20tourism,environment%20are%20wary%20of%20this (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Stewart, E.J.; Draper, D.; Johnston, M.E. A review of tourism research in the polar regions. Arctic 2005, 58, 383–394. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40513105 (accessed on 11 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Stewart, E.J.; Liggett, D. Polar tourism: Status, trends, futures. In The Routledge Handbook of the Polar Regions; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A.R.; Barðadóttir, Þ.; Auffret, S.; Bombosch, A.; Cusick, A.L.; Falk, E.; Lynnes, A. Arctic expedition cruise tourism and citizen science: A vision for the future of polar tourism. J. Tour. Futures 2020, 6, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolvanen, A.; Kangas, K. Tourism, biodiversity and protected areas–review from northern Fennoscandia. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 169, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cajiao, D.; Leung, Y.-F.; Larson, L.R.; Tejedo, P.; Benayas, J. Tourists’ motivations, learning, and trip satisfaction facilitate pro-environmental outcomes of the Antarctic tourist experience. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 37, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, P.T. Expedition cruise visits to protected areas in the Canadian Arctic: Issues of sustainability and change for an emerging market. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2012, 60, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Soutullo, A.; Ríos, M. Sustainable tourism in natural protected areas as a benchmark for Antarctic tourism. Antarct. Aff. 2020, 7, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tejedo, P.; Benayas, J.; Cajiao, D.; Leung, Y.-F.; De Filippo, D.; Liggett, D. What are the real environmental impacts of Antarctic tourism? Unveiling their importance through a comprehensive meta-analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 308, 114634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAATO. International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators. 2024. Available online: https://iaato.org (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- The Antarctic Treaty; Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty: 1 December 1959. Available online: https://www.ats.aq (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- AECO. Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators. 2024. Available online: https://www.aeco.no (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Curry, C.; McCarthy, J.; Darragh, H.; Wake, R.; Todhunter, R.; Terris, J. Could tourist boots act as vectors for disease transmission in Antarctica? J. Travel Med. 2002, 9, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Saarinen, J. Tourism and Change in Polar Regions; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lück, M. Environmental impacts of polar cruises. In Cruise Tourism in Polar Regions; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.S. Tourism stakeholders attitudes toward sustainable development: A case in the Arctic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erize, F.J. The impact of tourism on the Antarctic environment. Environ. Int. 1987, 13, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wu, D.; Chiu, C.-H. Impact of customer environmental attitude-behavior gap. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 802–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P. Tourism Impacts, Planning and Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, E.J.; Liggett, D.; Dawson, J. The evolution of polar tourism scholarship: Research themes, networks and agendas. Polar Geogr. 2017, 40, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerveny, L.K.; Miller, A.; Gende, S. Sustainable cruise tourism in marine world heritage sites. Sustainability 2020, 12, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.A. Responsible cruise tourism: Issues of cruise tourism and sustainability. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2011, 18, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Samad, S.; Han, H. Travel and Tourism Marketing in the age of the conscious tourists: A study on CSR and tourist brand advocacy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, B.W.; Chown, S.L. A meta-analysis of human disturbance impacts on Antarctic wildlife. Biol. Rev. 2016, 91, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M.J.; Forcada, J.; Jackson, J.A.; Waluda, C.M.; Nichol, C.; Trathan, P.N. A long-term study of gentoo penguin (Pygoscelis papua) population trends at a major Antarctic tourist site, Goudier Island, Port Lockroy. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tin, T.; Fleming, Z.L.; Hughes, K.A.; Ainley, D.; Convey, P.; Moreno, C.; Pfeiffer, S.; Scott, J.; Snape, I. Impacts of local human activities on the Antarctic environment. Antarct. Sci. 2009, 21, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.; Carter, N.A.; Dawson, J. Community perspectives on the environmental impacts of Arctic shipping: Case studies from Russia, Norway and Canada. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1609189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.B. Beyond guidelines: A model for Antarctic tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzenbacher, D. Mechanisms for promoting and monitoring compliance with Arctic tourism guidelines. In Linking Tourism and Conservation in the Arctic; Meddelelser: Tromsø, Norway, 1998; Volume 159, pp. 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jabour, J.; Mortimer, G. Tourism in Antarctica should be curtailed. Aust. Geogr. 2005, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Splettstoesser, J. IAATO’s stewardship of the Antarctic environment: A history of tour operator’s concern for a vulnerable part of the world. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, B.; Elliot, S.; Jacobs, S. Expedition cruising in the Canadian arctic: Visitor motives and the influence of education programming on knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours. Resources 2017, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, E.; Çelik, F.; Ibrahim, B.; Gursoy, D. Past, present, and future scene of influencer marketing in hospitality and tourism management. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 322–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H. Brand Antarctica: How Global Consumer Culture Shapes Our Perceptions of the Ice Continent (Polar Studies); University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, H.E. Fictional Representations of Antarctic Tourism and Climate Change: To the Ends of the World. In Postcolonial Literatures of Climate Change; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 334–360. [Google Scholar]

- Splettstoesser, J.F.; Headland, R.K.; Todd, F. First circumnavigation of Antarctica by tourist ship. Polar Rec. 1997, 33, 244–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.B.; Graburn, N.H. Tourism Imaginaries: Anthropological Approaches; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, N.B. Tourism imaginaries: A conceptual approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuhara, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Okada, M.; Kato, M.; Kiuchi, T. Amount of narratives used on Japanese Pro-and Anti-HPV vaccination websites: A content analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2018, 19, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reamer, M.; Macdonald, C.; Wester, J.; Shriver-Rice, M. Whales for Sale: A Content Analysis of American Whale-Watching Operators’ Websites. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2023, 18, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leane, E. Antarctica in Fiction: Imaginative Narratives of the Far South; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, D.B.; Lawton, L.J. Twenty years on: The state of contemporary ecotourism research. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkler, W.; Aitken, R. Selling hope: Science marketing for sustainability. In The Sustainability Communication Reader: A Reflective Compendium; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D. The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; Volume 922. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.-H.; Liu, C.-C. The effects of empathy and persuasion of storytelling via tourism micro-movies on travel willingness. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Oates, C.; Thyne, M.; Alevizou, P.; McMorland, L.A. Comparing sustainable consumption patterns across product sectors. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyne, M.; Henry, J.; Lloyd, N. Land ahoy: How cruise passengers decide on their shore experience. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2015, 10, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzmann, D.; Shea, R. Whale Watching in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary: Understanding Passengers and Their Economic Contributions. 2020. Available online: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/27498 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Labanauskaitė, D.; Fiore, M.; Stašys, R. Use of E-marketing tools as communication management in the tourism industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, A.; Dospinescu, N.; Dospinescu, O. Beyond credibility: Understanding the mediators between electronic word-of-mouth and purchase intention. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.05359. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, N.-T. Effects of travel website quality and perceived value on travel intention with eWOM in social media and website reviews as moderators. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2024, 25, 596–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J. Using tourism free--choice learning experiences to promote environmentally sustainable behaviour: The role of post--visit ‘action resources’. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S. Water equity–Contrasting tourism water use with that of the local community. Water Resour. Ind. 2014, 7, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkler, W.; Higham, J.E. Stakeholder perspectives on sustainable whale watching: A science communication approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Moscardo, G. Exploring cross-cultural differences in attitudes towards responsible tourist behaviour: A comparison of Korean, British and Australian tourists. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 11, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]